Introduction

MZL is an indolent B-cell neoplasm thought to

originate from post-germinal center marginal zone B cells, commonly

presenting in the spleen, lymph nodes and mucosa-associated

lymphoid tissues (MALT) (1).

Histologically, the neoplastic cells typically display a

monomorphic population of small-to-medium lymphocytes with slightly

irregular nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli and moderate amounts of

pale cytoplasm (2,3). The pathogenesis of MZL is closely

linked to chronic antigenic stimulation, frequently driven by

infectious agents such as Helicobacter pylori in gastric

MALT lymphoma. Additionally, recurrent molecular aberrations,

including somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes, specific

chromosomal abnormalities [e.g., t(11;18), trisomies 3 and 18, and

deletion 6q23], and mutations in genes such as Notch receptor 2

(NOTCH2), Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2), TNF alpha-induced protein 3

and TBL1X/Y related 1, are critical contributors to lymphomagenesis

and disease progression (4,5). Current frontline therapies primarily

employ anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (e.g., rituximab), often

combined with chemotherapy regimens (e.g., bendamustine or CHOP

variants), which substantially improve response rates and survival

outcomes (6). Nevertheless,

inherent and acquired chemoresistance and frequent disease relapse

persist as significant clinical challenges, limiting long-term

curability and highlighting the need for innovative therapeutic

approaches (7). Consequently,

targeting molecular pathways beyond conventional chemotherapy

represents a pivotal research direction. In this context,

dysregulated autophagy, a conserved lysosomal degradation pathway

essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, and its therapeutic

potential have emerged as significant research areas in oncology.

Aberrant expression of key autophagy-related proteins has been

documented across multiple malignancies, including lymphoma

(8), ovarian (9), lung (10), breast (11) and colorectal cancers (12), suggesting that this pathway may

represent a therapeutic target. MZL constitutes roughly 5–10% of

non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases globally, with an annual incidence

estimated at 2–3 per 100,000 population (13,14).

Although considered indolent, MZL typically follows a chronic,

relapsing clinical course, characterized by median overall survival

exceeding 10 years but frequent recurrence following conventional

immunochemotherapy. Relapsed or refractory disease remains

therapeutically challenging, emphasizing the urgent need for novel

molecular targets and more effective treatments (5,15).

Autophagy dysregulation has been implicated in

various lymphoma subtypes, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

(DLBCL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL),

where reduced Beclin-1 or microtubule-associated protein

1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) expression and increased accumulation of

p62 correlate with adverse prognosis and chemoresistance (16,17).

These findings indicate that autophagy dysfunction may be a shared

oncogenic mechanism across B-cell malignancies. Clinically, several

agents targeting autophagy and apoptosis pathways, such as

chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and the Bcl-2 inhibitor venetoclax,

have demonstrated encouraging efficacy in preclinical studies and

early-phase clinical trials (18),

further highlighting the therapeutic relevance of targeting this

pathway. Although abnormal expression of primary

autophagy-associated proteins such as Beclin-1, LC3 and p62 has

been well-characterized in lymphomas like DLBCL, MCL and FL

(19–21), their expression patterns in MZL have

not yet been extensively studied. To bridge this knowledge gap and

evaluate the therapeutic implications of autophagy modulation in

MZL, this research examined the expression levels of crucial

autophagy indicators, including Beclin-1, LC3, sequestosome

(SQSTM)1/p62 and Bcl-2, in clinical tissue samples obtained from

patients diagnosed with MZL.

Patients and methods

Study and control cohorts

The demographic and clinicopathological data of the

patients are summarized in Table I.

MZL cohort: Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks

were analyzed from 16 patients with newly diagnosed,

treatment-naïve MZL (11 males, 5 females; median age, 64.5 years;

range, 45–78 years). All specimens were collected at initial

diagnosis between January 2014 and December 2024 from Shandong

Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University

(Jinan, Shandong). Diagnoses were strictly confirmed according to

current World Health Organization lymphoma classification criteria

(1). Patients with previous

radiotherapy or chemotherapy exposure were excluded. Subtypes

included 10 nodal MZL, 4 MALT lymphomas and 2 splenic MZL. MZL

cases were retrospectively identified from the pathology archives,

and all newly diagnosed, treatment-naïve patients with adequate

FFPE tissue and complete baseline data during the study period were

included. The control cohort consisted of FFPE tissue blocks from

16 patients with RLH (12 males, 4 females; median age, 62 years;

range, 50–75 years). RLH cases were consecutively identified from

the pathology archives of the same center during the same period

based on the availability of treatment-naïve FFPE tissue blocks,

rather than being artificially matched to the MZL group. By

including all eligible MZL and RLH cases from the same institution

and time window, rather than arbitrarily selecting or artificially

matching controls, the risk of selection bias was minimized.

Baseline demographic and clinicopathological characteristics,

including age, sex distribution and involved sites, did not differ

significantly between the MZL and RLH groups.

| Table I.Demographic and clinicopathological

characteristics of the study cohort. |

Table I.

Demographic and clinicopathological

characteristics of the study cohort.

| Characteristic | MZL (n=16) | RLH (n=16) |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

Male | 11 | 12 |

|

Female | 5 | 4 |

| Median age, years

(range) | 64.5 (45–78) | 62 (50–75) |

| Pathological

diagnosis |

|

|

|

MALT | 4 | - |

|

NMZL | 10 | - |

|

SMZL | 2 | - |

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-Beclin-1 antibody (cat. no. ab207612; Abcam)

was used at a dilution of 1:100. Anti-SQSTM1/p62 antibody (cat. no.

ab109012; Abcam) was used at a dilution of 1:2,000. LC3A/LC3B

polyclonal antibody (cat. no. ab109012; Abcam) was used at a

dilution of 1:200. Anti-Bcl-2 antibody (cat. no. ab2137583; Abcam)

was used at a dilution of 1:500. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (cat. no. ab205718; Abcam) was applied

at a dilution of 1:1,000. A diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen kit

(cat. no. DA1010; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.), 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Wuhan Boster Biological

Technology, Ltd.) and 3% H2O2 (Wuhan Boster

Biological Technology, Ltd.) were also utilized.

Experimental procedures

Tissue sections were first baked, deparaffinized,

rehydrated and washed with PBS. Antigen retrieval was then

performed via high-pressure treatment using EDTA buffer, after

which slides were cooled to ambient temperature. Blocking of

endogenous peroxidase activity was achieved by treating sections

with 3% H2O2, and non-specific

antigen-antibody interactions were minimized by incubating slides

in BSA. Primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4°C, and

subsequently, slides underwent washing in PBS before incubation at

37°C for 40 min with secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP.

Following PBS washes, staining was visualized using DAB chromogen,

counterstained with hematoxylin, differentiated and blued. Finally,

slides were mounted with coverslips and neutral gum prior to

imaging.

Quantitative analysis

Pathological assessments were independently

performed by two blinded, experienced pathologists using optical

microscopy (magnification, ×400). For each specimen, five

non-overlapping, randomly selected high-power fields were used for

semiquantitative analysis. Protein expression levels were

quantified using ImageJ software (1.54p; National Institutes of

Health) to calculate the average optical density (AOD): AOD=Σ

integrated optical density/Σ positive pixel area.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using

GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (Dotmatics). Expression differences of

autophagy-related proteins between groups were assessed by applying

unpaired two-tailed Student's t-tests. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

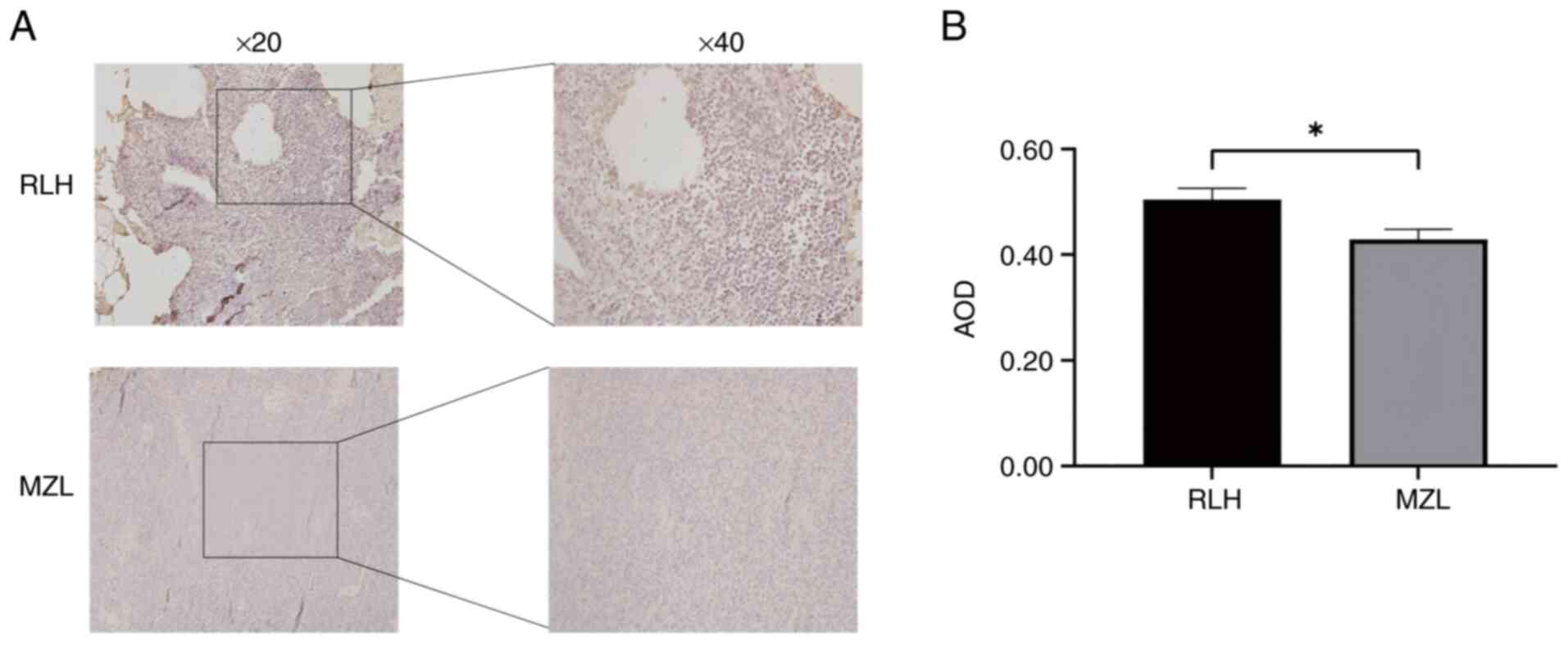

Suppressed Beclin-1 expression in MZL

tissues

Beclin-1 exhibited cytoplasmic granular

(yellowish-brown) staining in both RLH and MZL tissues by IHC

analysis. Quantitative evaluation demonstrated a significant

reduction in Beclin-1 expression in MZL tissues (AOD=0.43±0.19)

compared to RLH controls (AOD=0.50±0.21; P=0.0139) (Fig. 1).

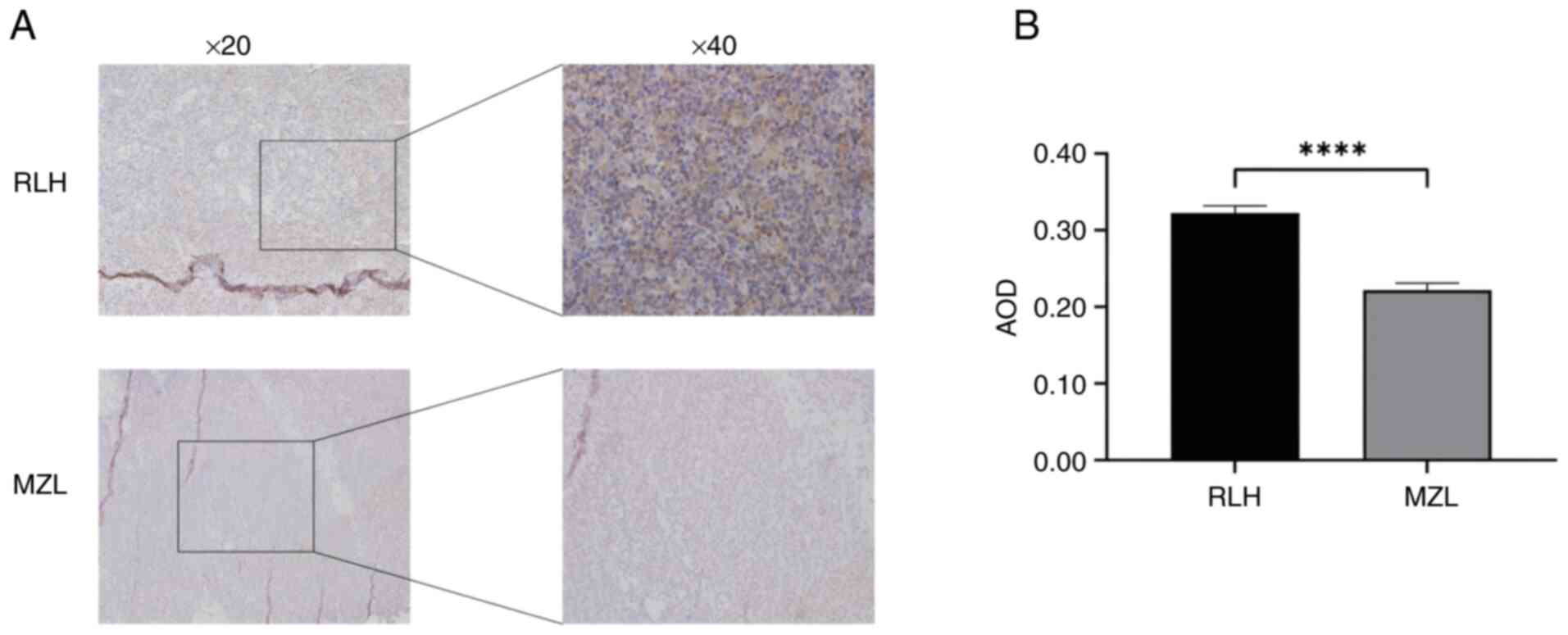

Impaired autophagic flux in MZL via

reduced LC3 expression

LC3 displayed characteristic cytoplasmic granular

staining in all specimens (Fig. 2).

Compared to RLH controls (AOD=0.32±0.09), MZL tissues showed

significantly reduced LC3 expression (AOD=0.22±0.09; P<0.0001),

indicating defective autophagosome formation.

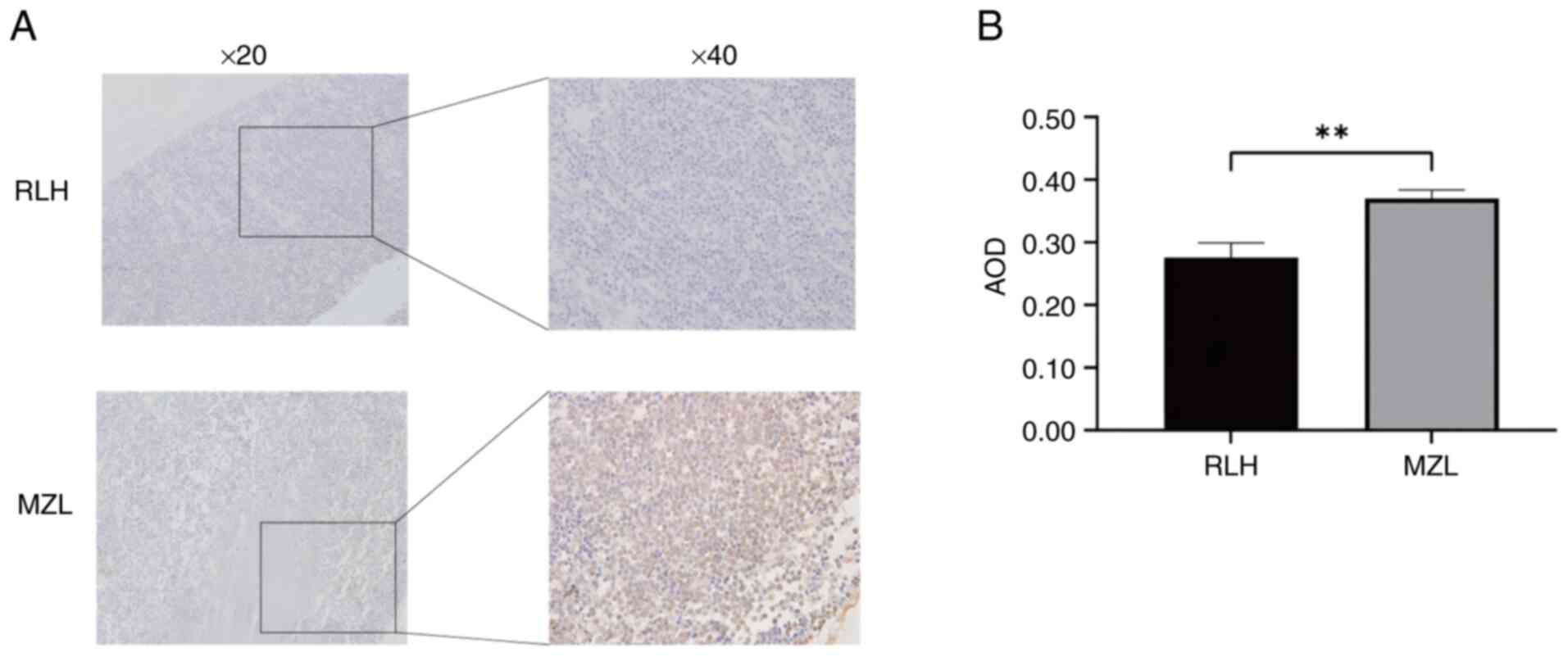

Accumulation of p62 indicates

autophagic dysfunction in MZL

Consistent with impaired autophagic flux, p62

expression was significantly elevated in MZL tissues

(AOD=0.37±0.13) compared with RLH controls (AOD=0.28±0.23;

P=0.0017) (Fig. 3). Cytoplasmic

granular accumulation (yellowish-brown staining) of this selective

autophagy receptor was confirmed by IHC, suggesting defective

substrate clearance as a potential mechanism underlying MZL

pathology.

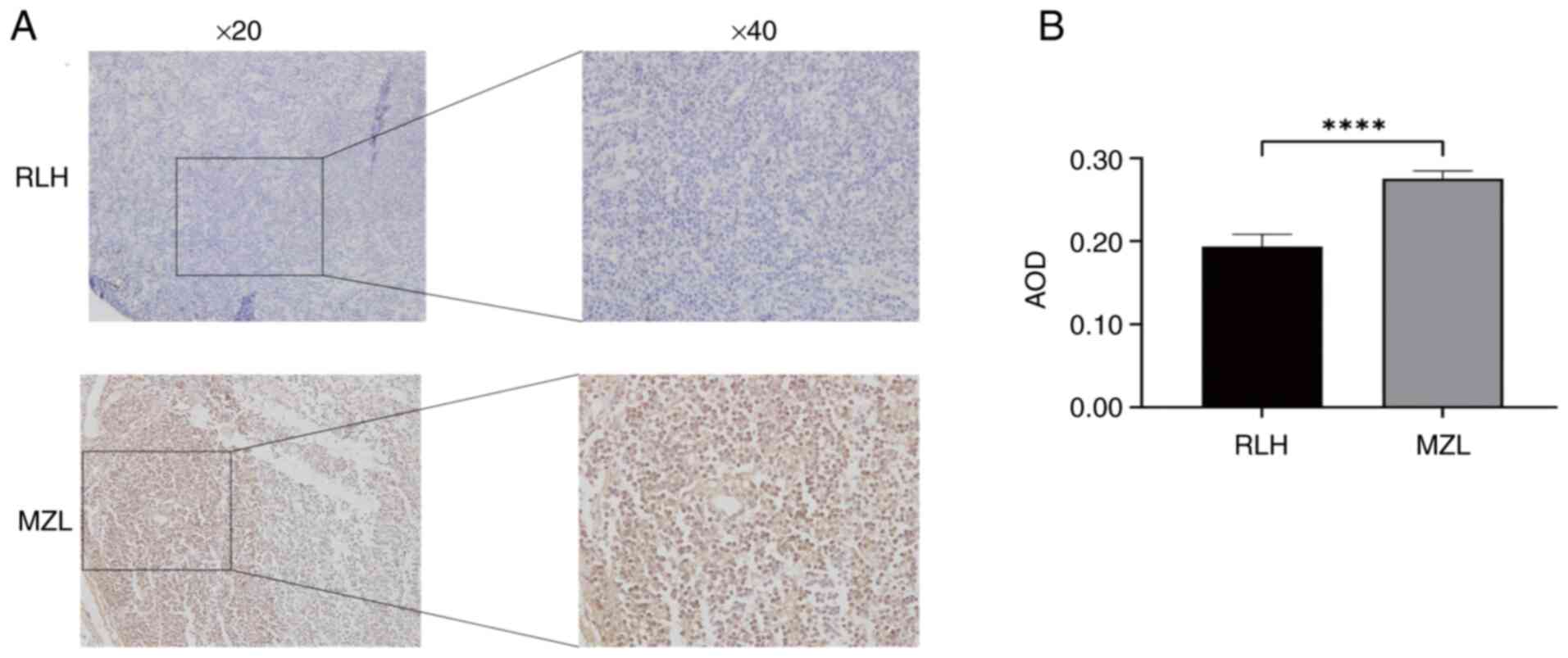

Elevated anti-apoptotic Bcl-2

expression in MZL

IHC demonstrated cytoplasmic Bcl-2 accumulation

(granular yellowish-brown staining) in all tissues. MZL tissues

displayed significantly increased expression (AOD=0.28±0.09)

compared to RLH controls (AOD=0.19±0.15; P<0.0001) (Fig. 4), indicating enhanced survival

signaling typical of lymphomagenesis. This molecular alteration

represents a potential therapeutic target.

Discussion

Autophagy is a key catabolic process that maintains

balance in cells via the lysosomal breakdown of damaged organelles

and protein aggregates, as well as redundant components in the body

(22). Autophagy is a dynamic

process that occurs in five sequential steps (22–24),

which can result in dysfunctions in various key steps. At the

initiation of autophagy, signaling pathways that involve mTOR

complex 1 (mTORC1) lead to the inhibition of unc-51 like autophagy

activating kinase 1/2 complexes that inhibit the initiation of

autophagy (25). At the vesicle

nucleation step, Bcl-2:Beclin-1 complexes inhibit autophagosome

formation via the inhibition of Beclin-1/VPS34 retromer complex

component complexes (26–28). Furthermore, in pathologic scenarios,

there is a possibility of defective autophagy, leading to a

reduction in the usual physiological roles of autophagy, which in

turn contributes to cancer development. Dysautophagy in cancer

allows cancer cells to adapt in a host that is under various

pathologic stresses, including hypoxia as well as starvation

(29,30).

Autophagy's role remains particular in the context

of tumorigenesis, having a dual role that seems contradictory in

nature (31–34). Autophagy is a tumor suppressor

mechanism that eliminates dysfunctional organelles, misfolded

proteins, as well as reactive oxygen species, thereby maintaining

genomic stability and preventing tumorigenesis. However, in already

present malignancies, dysfunctional/mutated autophagy pathways are

known to promote tumor survival during metabolic, as well as

hypoxic stresses, thereby leading to increased tumor progression as

well as resistance (35,36). These data observed in MZL cases in

the current study, showing dysfunctional Beclin-1 and reduced LC3

expression levels, as well as increased p62 accumulation, are

possibly suggestive of a transition from a protective to a

dysfunctional form of autophagy, leading to survival in the tumor

microenvironment (37).

Furthermore, certain known mutations in MZL will possibly interact

with the autophagy pathways. NOTCH2 mutations leading to

increased B-cell survival as well as B-cell activation possibly

lead to a reduction in autophagy as a result of increased mTOR, as

well as NF-κB pathways in those downstream pathways. Furthermore,

mutations in KLF2 leading to a reduction in KLF2 activity possibly

result in increased NF-κB pathways in a possibly perpetually

increased phase of activity, leading to alterations in metabolism

of cells, as well as functioning as known modifiers of the process

of autophagy (38,39). Therefore, dysfunctional autophagy

observed in MZL is possibly a result of a multitude of these

mutations affecting the pathways.

As increasing studies have focused on MZL, the

intricate relationship between autophagy and MZL pathogenesis has

slowly been revealed. Autophagy plays a role in MZL development and

progression through various pathways, such as B-cell receptor

signaling modulation, tumor microenvironment modulation, increased

drug resistance, as well as crosstalk between tumor suppressor

pathways (40,41). Goldsmith et al (42) revealed that autophagy supports

metabolic rerouting in RAS-mutant cancer cells. Poillet-Perez et

al (43) also found that

autophagy suppresses T-cell immunity functions by attenuating

stimulator of interferon response cGAMP interactor 1 pathway

activity, whereas hepatocyte-specific autophagy deficiency

moderately increased T-cell immunity against tumors. Furthermore,

in 2024, Choi et al (44)

found that myeloid-specific deficiency of autophagy reduced

tumor-associated macrophages, increasing the accumulation of

myeloid-derived suppressor cells. However, the mechanism of

disrupted autophagy in MZL pathogenesis remains to be fully

elucidated.

Beclin-1 inhibits tumor initiation under

physiological circumstances. Conversely, in a tumor

microenvironment, Beclin-1 expression is reduced. This leads to a

failure in the formation of autophagosomes, thereby increasing the

susceptibility of cells to transformation and tumorigenesis. Jiang

et al (10) confirmed that

Beclin-1 expression is significantly reduced in non-small cell lung

cancer tissues compared with normal lung tissues. Pattingre and

Levine (45) observed that Beclin-1

haplo deletion resulted in reduced autophagy in B lymphocytes. This

further increased the susceptibility of mice to spontaneous B-cell

lymphoma. It was revealed that B-cell lymphomas often display high

Bcl-2 expression. This not only prevents apoptosis but also has a

role in increasing B-cell lymphoma by functioning as a negative

regulator of Beclin-1 expression-initiated autophagy (46). Furthermore, in the present analysis,

it was discovered that Beclin-1 was downregulated, whereas Bcl-2

was upregulated in MZL patients' tissue, suggesting that there is a

problem in the formation of vesicles in MZL-related autophagy. In

addition, it may be speculated that the abnormal expression of

Beclin-1 and Bcl-2, regulated by the tumor microenvironment, leads

to phagophores in MZL, making it impossible to remove metabolic

waste in the form of autophagosomes, paving a way towards the

transformation of cancerous cells in MZL. However, the current

results indicated that this autophagy-related, Bcl-2-targeted

hypothesis needs further clarification due to insufficient data

supporting the use of Bcl-2 inhibitors in MZL. Nevertheless, some

small molecules of Bcl-2 inhibitor drugs like ABT-199 (47) and ABT-263 (48) are already in the clinical trials

phase. Furthermore, the present results demonstrate that Bcl-2

inhibitors have promising potential utility in patients MZL as a

treatment drug. Future mechanistic and preclinical studies are

warranted to determine whether modulating phagophore formation via

Bcl-2 inhibition can influence MZL progression.

Dysregulation of autophagy is often found in the

elongation process of the vesicle, in which LC3 is a crucial

component. In this process, LC3 is targeted to the autophagosomal

membrane, where it monitors autophagy activity, as well as

targeting the components of the core autophagy process to the

phagophore membrane. It has been irrefutably shown that lack of LC3

leads to a marked reduction in the efficiency of autophagosome

formation and fusion with lysosomes (49–51).

In addition, the process of bringing key components of autophagy to

the phagophore membrane is regulated by LC3 in a

p62/SQSTM1-mediated way. p62 binds to ubiquitinated target

proteins, directing them towards the autophagosomal membrane via a

specific interaction with LC3. Importantly, this is possible as p62

itself is a target of autophagy. As such, p62 accumulation is

expected in most cases of dysfunctional autophagy activity

(52,53). This results in the activation of

mTOR and NF-κB pathways that initiate tumorigenic processes. This

suggested that in autophagy-deficient animal models, p62

overexpression is observed, increasing oxidative stress in

conjunction with increased tumorigenic activity (54,55).

This is also observed in the present analysis: LC3 is

downregulated, while p62 is increased in MZL tumor tissues.

Together, these alterations support the present hypothesis that

excessive p62 accumulation, combined with LC3 repression, reflects

a block in phagophore/autophagosome formation and membrane growth,

thereby contributing to tumor-promoting autophagy dysfunction in

MZL. Future studies will involve transgenic strategies that aim to

increase LC3 expression in conjunction with p62 inhibition

strategies via small molecule drugs that inhibit p62 accumulation

to provoke a positive response in MZL by overcoming phagophore

membrane maturation.

The present findings provide compelling evidence

that MZL exhibits coordinated dysregulation of core autophagy

machinery. Significant downregulation of Beclin-1 (P<0.05) and

LC3 (P<0.0001), key regulators of autophagosome initiation and

maturation, alongside elevated expression of the autophagy receptor

p62 (P<0.001) and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 (P<0.0001), highlights

impaired autophagic flux as a potential hallmark of MZL

pathobiology. Differential expression of LC3, p62, Bcl-2 and

Beclin-1 between MZL tissues and RLH tissues could help in the

precise identification of MZL. Future studies could aim at the

development of a multiplexed IHC antibody kit that will help in the

precise identification of MZL, as there is a lack of a specific

biomarker in the field that will prompt the clinician to initiate

appropriate treatment strategies. Besides Bcl-2 inhibition, other

strategies targeting the phenomenon of autophagy in hematologic

malignancies are under investigation (56,57).

These include mTOR pathway inhibitors (everolimus, rapamycin),

which inhibit the initiation of autophagy through mTORC1 pathway

modulation, and agents that target autophagy, such as chloroquine

and hydroxychloroquine, which inhibit the fusion of the

autophagosome with the lysosome. Exploring these agents,

individually or in rational combinations, may provide further

therapeutic avenues for MZL.

The present study also has several limitations.

Firstly, the sample size is small, even if considering the subtypes

of MZL: Nodal, MALT and spleen involvement. Due to this small

sample size, certain parameters could not be studied in a subtype

analysis. Secondly, this analysis was mostly done by IHC. IHC is

appropriate to characterize protein localization in clinical

specimens, which, however, lack any molecular confirmation. It is

proposed that analysis involving western blotting analysis or

certain genetic studies in a large series of specimens could

provide new perspectives. Lastly, survival data are not available

in this analysis. This makes certain parameters, including survival

outcomes, impossible to analyze in this particular experiment.

Furthermore, since certain studies involve alterations in a

particular group of genes, as also observed in this experiment, in

a variety of lymphomas as well as certain solid cancers, this

pattern of alterations is more of a supporting factor than a

confirmatory one.

In conclusion, the present analysis identified a

distinct molecular signature of autophagic dysfunction across MZL

subtypes, characterized by significant suppression of Beclin-1

(P<0.05) and LC3-II (P<0.0001) expression, coupled with

pathological accumulation of p62 (P<0.001) and Bcl-2

(P<0.0001). Collectively, these results provide preliminary

evidence that coordinated dysregulation of key autophagy-associated

proteins, specifically reduced Beclin-1 and LC3 expression and

increased accumulation of p62 and Bcl-2, may represent a distinct

molecular hallmark of MZL pathobiology. Although these findings

offer valuable insights into the potential role of autophagy in

MZL, they should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather

than definitive. Validation through larger, independent cohorts and

complementary functional studies will be necessary to confirm these

observations and explore their therapeutic implications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from the Taishan Youth

Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no.

tsqn201812140).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JSR designed the study. AL performed the analysis

and interpretation of images. NS performed the analysis and

interpretation of data. XZ performed the analysis and

interpretation of data, and contributed to manuscript drafting and

critical revisions of the intellectual content. XZ and NS confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with

relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the

Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to

Shandong First Medical University (approval no. NSFC:NO.2022-209;

approval date, March 1st, 2024). Written informed consent for

participation in this study, including the use of their tissue

samples for scientific research, was provided by the participants'

legal guardians/next of kin.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris

NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz

AD and Jaffe ES: The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization

classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 127:2375–2390. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Juárez-Salcedo LM and Castillo JJ:

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma. Hematol

Oncol Clin North Am. 33:639–656. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, Johnson PW,

Ponzoni M, Raderer M, Ricardi U, Salar A, Stamatopoulos K,

Thieblemont C, et al: Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical

Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann

Oncol. 31:17–29. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rodríguez-Sevilla JJ and Salar A: Recent

advances in the genetic of MALT Lymphomas. Cancers (Basel).

14:1762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rossi D, Bertoni F and Zucca E:

Marginal-zone lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 386:568–581. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste

E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, Lefort S, Marit G, Macro M,

Sebban C, et al: Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5

trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to

standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe

d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 116:2040–2045. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Luo C, Wu G, Huang X, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Song

Q, Xie M, Sun Y, Huang Y, Huang Z, et al: Efficacy and safety of

new anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies versus rituximab for induction

therapy of CD20+ B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 11:32552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kyriazopoulou L, Karpathiou G,

Hatzimichael E, Peoc'h M, Papoudou-Bai A and Kanavaros P: Autophagy

and cellular senescence in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Pathol Res

Pract. 236:1539642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ying H, Qu D, Liu C, Ying T, Lv J, Jin S

and Xu H: Chemoresistance is associated with Beclin-1 and PTEN

expression in epithelial ovarian cancers. Oncol Lett. 9:1759–1763.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jiang L, Liang X, Liu M, Wang W, Ma J, Guo

Q, Han L, Yang C and Nan K: Reduced expression of liver kinase B1

and Beclin1 is associated with the poor survival of patients with

non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 32:1931–1938. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wu T, Li Y, Gong L, Lu JG, Du XL, Zhang

WD, He XL and Wang JQ: Multi-step process of human breast

carcinogenesis: A role for BRCA1, BECN1, CCND1, PTEN and UVRAG. Mol

Med Rep. 5:305–312. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang L, Zhang H, Sun M, Yin Z and Qian J:

High mobility group box 1-mediated autophagy promotes neuroblastoma

cell chemoresistance. Oncol Rep. 34:2969–2976. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cheah CY, Zucca E, Rossi D and Habermann

TM: Marginal zone lymphoma: Present status and future perspectives.

Haematologica. 107:35–43. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fiorentino V, Pizzimenti C, Pierconti F,

Lentini M, Ieni A, Caffo M, Angileri F, Tuccari G, Fadda G, Martini

M and Larocca LM: Unusual localization and clinical presentation of

primary central nervous system extranodal marginal zone B-cell

lymphoma: A case report. Oncol Lett. 26:4082023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zucca E, Rossi D and Bertoni F: Marginal

zone lymphomas. Hematol Oncol. 41 (Suppl 1):S88–S91. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ye J, Zhang J, Zhu Y, Wang L, Jiang X, Liu

B and He G: Targeting autophagy and beyond: Deconvoluting the

complexity of Beclin-1 from biological function to cancer therapy.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 13:4688–4714. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nicotra G, Mercalli F, Peracchio C,

Castino R, Follo C, Valente G and Isidoro C: Autophagy-active

beclin-1 correlates with favourable clinical outcome in non-Hodgkin

lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 23:937–950. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Avsec D, Djordjevič AT, Kandušer M,

Podgornik H, Škerget M and Mlinarič-Raščan I: Targeting autophagy

triggers apoptosis and complements the action of venetoclax in

chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Cancers (Basel). 13:45572021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Valente G, Morani F, Nicotra G, Fusco N,

Peracchio C, Titone R, Alabiso O, Arisio R, Katsaros D, Benedetto C

and Isidoro C: Expression and clinical significance of the

autophagy proteins BECLIN 1 and LC3 in ovarian cancer. Biomed Res

Int. 2014:4626582014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang S, Huang F, Wang J, You R, Huang Q

and Chen Y: SQSTM1/p62 predicts prognosis and upregulates the

transcription of CCND1 to promote proliferation in mantle cell

lymphoma. Protoplasma. 262:635–647. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

McCarthy A, Marzec J, Clear A, Petty RD,

Coutinho R, Matthews J, Wilson A, Iqbal S, Calaminici M, Gribben JG

and Jia L: Dysregulation of autophagy in human follicular lymphoma

is independent of overexpression of BCL-2. Oncotarget.

5:11653–11668. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li-Harms X, Milasta S, Lynch J, Wright C,

Joshi A, Iyengar R, Neale G, Wang X, Wang YD, Prolla TA, et al:

Mito-protective autophagy is impaired in erythroid cells of aged

mtDNA-mutator mice. Blood. 125:162–174. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Glick D, Barth S and Macleod KF:

Autophagy: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 221:3–12.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yu L, Chen Y and Tooze SA: Autophagy

pathway: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Autophagy. 14:207–215.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Alers S, Löffler AS, Wesselborg S and

Stork B: Role of AMPK-mTOR-Ulk1/2 in the regulation of autophagy:

Cross talk, shortcuts, and feedbacks. Mol Cell Biol. 32:2–11. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Levine B, Sinha S and Kroemer G: Bcl-2

family members: Dual regulators of apoptosis and autophagy.

Autophagy. 4:600–606. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Usman RM, Razzaq F, Akbar A, Farooqui AA,

Iftikhar A, Latif A, Hassan H, Zhao J, Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, et

al: Role and mechanism of autophagy-regulating factors in

tumorigenesis and drug resistance. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol.

17:193–208. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT and Tang D: The

Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death

Differ. 18:571–580. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Vitto VAM, Bianchin S, Zolondick AA,

Pellielo G, Rimessi A, Chianese D, Yang H, Carbone M, Pinton P,

Giorgi C and Patergnani S: Molecular mechanisms of autophagy in

cancer development, progression, and therapy. Biomedicines.

10:15962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Rangel M, Kong J, Bhatt V, Khayati K and

Guo JY: Autophagy and tumorigenesis. FEBS J. 289:7177–7198. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Russell RC and Guan KL: The multifaceted

role of autophagy in cancer. EMBO J. 41:e1100312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Levy JM and Thorburn A: Autophagy in

cancer: Moving from understanding mechanism to improving therapy

responses in patients. Cell Death Differ. 27:843–857. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chavez-Dominguez R, Perez-Medina M,

Lopez-Gonzalez JS, Galicia-Velasco M and Aguilar-Cazares D: The

double-edge sword of autophagy in cancer: From tumor suppression to

pro-tumor activity. Front Oncol. 10:5784182020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ahmadi-Dehlaghi F, Mohammadi P, Valipour

E, Pournaghi P, Kiani S and Mansouri K: Autophagy: A challengeable

paradox in cancer treatment. Cancer Med. 12:11542–11569. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Pizzimenti C, Fiorentino V, Ruggeri C,

Franchina M, Ercoli A, Tuccari G and Ieni A: Autophagy involvement

in non-neoplastic and neoplastic endometrial pathology: The state

of the art with a focus on carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 25:121182024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Pandey A, Goswami A, Jithin B and Shukla

S: Autophagy: The convergence point of aging and cancer. Biochem

Biophys Rep. 42:1019862025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pizzimenti C, Fiorentino V, Franchina M,

Martini M, Giuffrè G, Lentini M, Silvestris N, Di Pietro M, Fadda

G, Tuccari G and Ieni A: Autophagic-related proteins in brain

gliomas: Role, mechanisms, and targeting agents. Cancers (Basel).

15:26222023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pizzimenti C, Curcio A, Fiorentino V,

Germanò A, Martini M, Ieni A and Tuccari G: Immunoexpression of

autophagy-related proteins in a single-center series of sporadic

adult conventional clival chordomas. Oncol Lett. 29:322025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

García Ruiz O, Sánchez-Maldonado JM,

López-Nevot MÁ, García P, Macauda A, Hernández-Mohedo F, Veiga J,

Figuerola J, Videvall E and Martínez-de la Puente J: Autophagy in

Hematological Malignancies. Cancers (Basel). 14:50722022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Buchner M and Müschen M: Targeting the

B-cell receptor signaling pathway in B lymphoid malignancies. Curr

Opin Hematol. 21:341–349. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Goldsmith J, Levine B and Debnath J:

Autophagy and cancer metabolism. Methods Enzymol. 542:25–57. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Poillet-Perez L, Sharp DW, Yang Y, Laddha

SV, Ibrahim M, Bommareddy PK, Hu ZS, Vieth J, Haas M, Bosenberg MW,

et al: Autophagy promotes growth of tumors with high mutational

burden by inhibiting a T-cell immune response. Nat Cancer.

1:923–934. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Choi J, Park G, Lee SSY, Dominici E,

Becker L, Macleod KF, Kron SJ and Hwang S: Context-dependent roles

for autophagy in myeloid cells in tumor progression. bioRxiv.

16:2024.07.12.603292. 2024.

|

|

45

|

Pattingre S and Levine B: Bcl-2 inhibition

of autophagy: A new route to cancer? Cancer Res. 66:2885–2888.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Xu HD and Qin ZH: Beclin 1, Bcl-2 and

autophagy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1206:109–126. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Minson A, Tam C, Dickinson M and Seymour

JF: Targeted agents in the treatment of indolent b-cell non-hodgkin

lymphomas. Cancers (Basel). 14:12762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Warren CFA, Wong-Brown MW and Bowden NA:

BCL-2 family isoforms in apoptosis and cancer. Cell Death Dis.

10:1772019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lamark T and Johansen T: Mechanisms of

selective autophagy. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 37:143–169. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Schaaf MBE, Keulers TG, Vooijs MA and

Rouschop KMA: LC3/GABARAP family proteins: Autophagy-(un)related

functions. FASEB J. 30:3961–3978. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Galluzzi L and Green DR:

Autophagy-independent functions of the autophagy machinery. Cell.

177:1682–1699. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shaid S, Brandts CH, Serve H and Dikic I:

Ubiquitination and selective autophagy. Cell Death Differ.

20:21–30. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Amaravadi R, Kimmelman AC and White E:

Recent insights into the function of autophagy in cancer. Genes

Dev. 30:1913–1930. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Moscat J and Diaz-Meco MT: p62: A

versatile multitasker takes on cancer. Trends Biochem Sci.

37:230–236. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wei H, Wang C, Croce CM and Guan JL:

p62/SQSTM1 synergizes with autophagy for tumor growth in vivo.

Genes Dev. 28:1204–1216. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Feng Y, Chen X, Cassady K, Zou Z, Yang S,

Wang Z and Zhang X: The role of mTOR inhibitors in hematologic

disease: From bench to bedside. Front Oncol. 10:6116902020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ali ES, Mitra K, Akter S, Ramproshad S,

Mondal B, Khan IN, Islam MT, Sharifi-Rad J, Calina D and Cho WC:

Recent advances and limitations of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment

of cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 22:2842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|