Introduction

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) is a rare,

clinicopathologically distinct soft-tissue sarcoma and a subtype of

chondrosarcoma, and it represents a malignant mesenchymal neoplasm

of uncertain differentiation and exceptional rarity, accounting for

<3% of all soft-tissue sarcomas, with an annual incidence of ~1

per million individuals. EMC is characterized histologically by

bland-appearing spindle to stellate cells arranged in cords,

reticular or lace-like patterns within abundant myxoid stroma and

typically, a lack of overt hyaline cartilage differentiation

(1). EMC most commonly arises in

the deep soft tissues of the proximal limbs in middle-aged to older

adults, predominantly affecting middle-aged adults (median age, 50

years) and showing a male-to-female ratio of ~2:1, with a

predilection for the thigh and popliteal fossa, and less frequent

involvement of the trunk (2).

Despite its deceptively bland cytology, EMC has been associated

with substantial risks of local recurrence and distant metastasis,

most often to the lungs and soft tissues. Recurrent chromosomal

rearrangements involving the nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A

member 3 (NR4A3) gene on chromosome 9q22 have emerged as

highly characteristic and diagnostically informative hallmarks. The

classic translocation is t(9;22)(q22;q12), which fuses Ewing

sarcoma breakpoint region 1 (EWSR1) with nuclear receptor

subfamily 4 group A member 3 (NR4A3). Other variant partners

include TATA-box binding protein associated factor 15

(TAF15), rearranged through t(9;17)(q22;q11), and less

commonly, transcription factor 12 (TCF12), involved in

t(9;15)(q22;q21) (3,4). By contrast, primary intracranial EMC

is exceedingly rare and has been reported to arise from the

meninges or, less commonly, the brain parenchyma; its clinical and

radiological features frequently overlap with meningioma, glioma

and other sarcomas, complicating the formation of an accurate

diagnosis (5). In the absence of

large series and standardized treatment protocols, evaluation

relies on integrated assessment combining imaging, histopathology

and, where available, molecular genetics. The present study reports

a case of adolescent intracranial EMC with high-grade features and

outlines the diagnostic pitfalls and management considerations

pertinent to this uncommon entity.

Case report

In April 2025, a 17-year-old male patient presented

to the Department of Neurosurgery at Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital

(Yantai, China) with a 1-week history of a progressive headache

that had acutely worsened over the preceding 24 h, accompanied by

nausea and emesis. A neurological examination showed impaired

orientation, calculation and memory. The pupils measured 3 mm

bilaterally, limb strength was Medical Research Council grade 5-

and no pathological reflexes were elicited (6). Non-contrast head computed tomography

(CT) scans taken in an external hospital revealed a right frontal

space-occupying lesion, with intracranial neoplasm and stroke

considered in the initial differential.

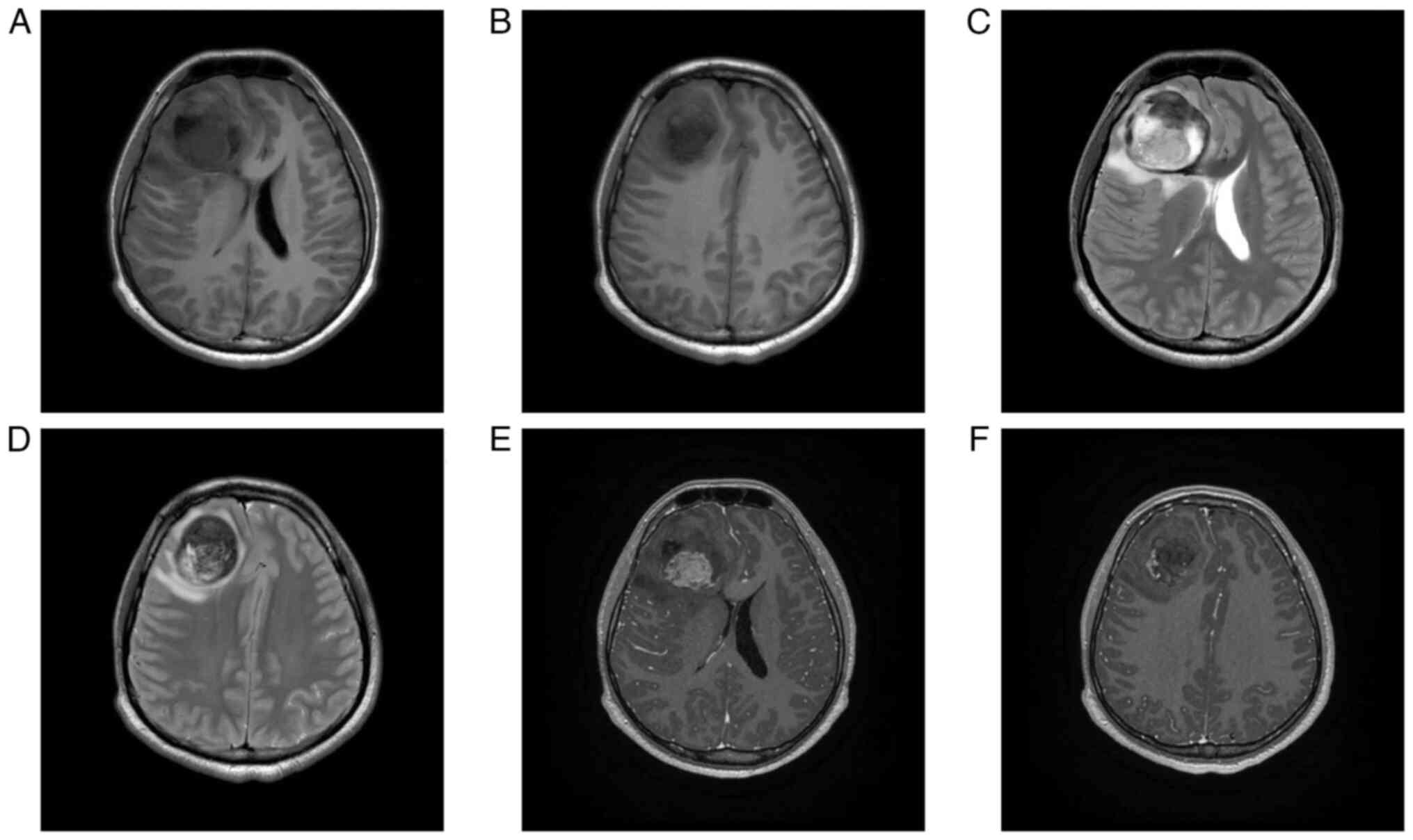

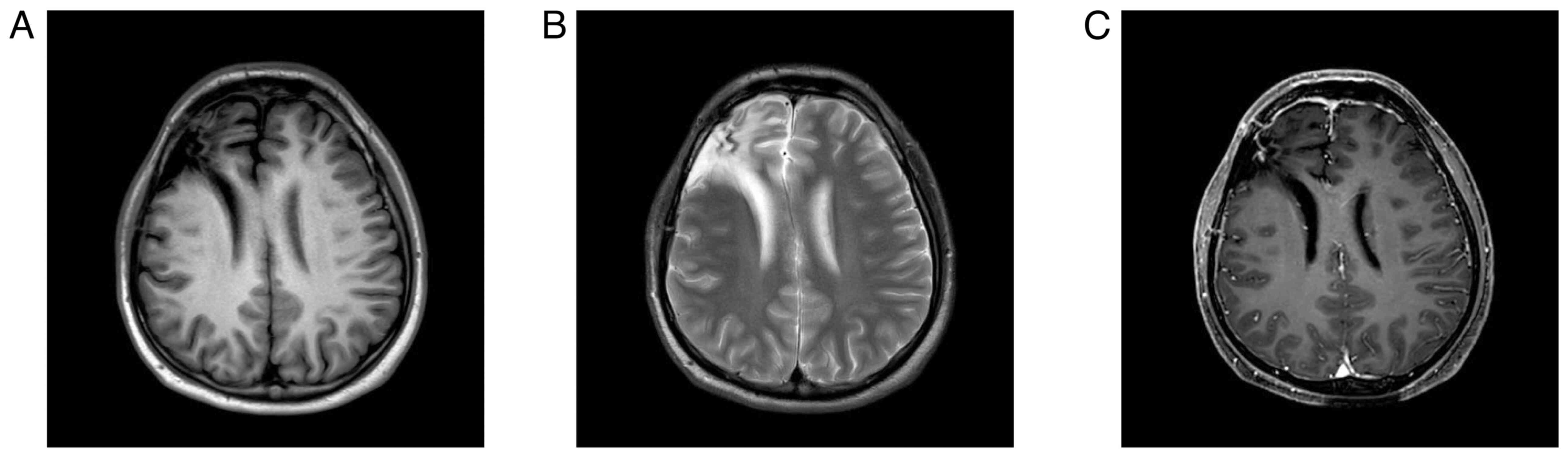

On hospital day 2, contrast-enhanced 3T magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a 7.2×5.2-cm right frontal

mass with intralesional hemorrhage and mass effect displacing the

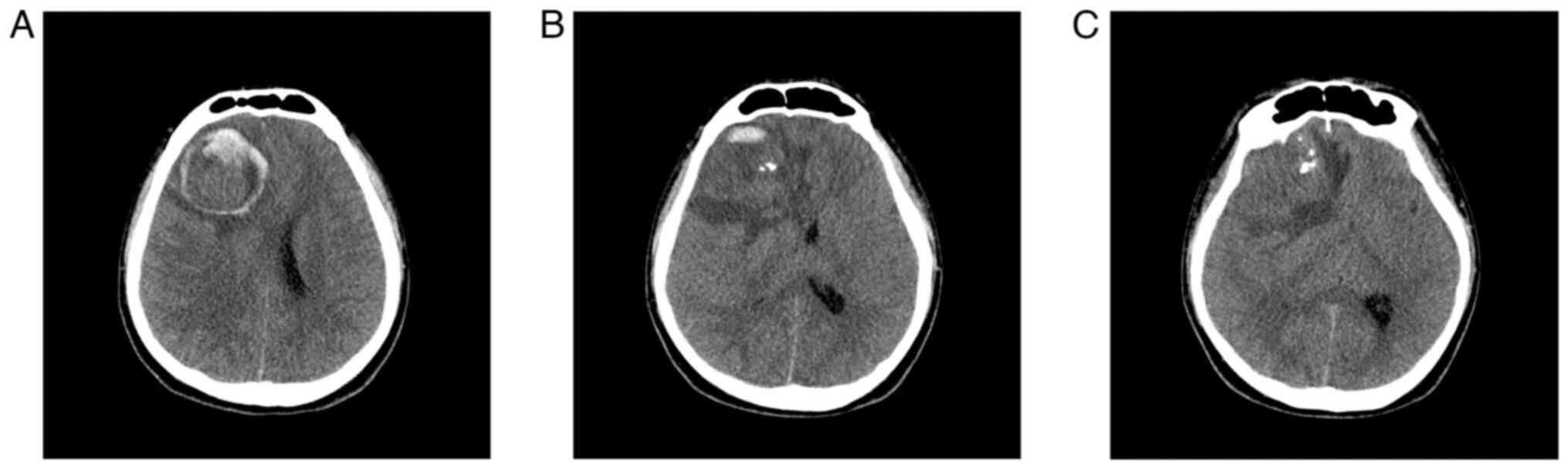

anterior and middle cerebral arteries (Fig. 1). CT angiography additionally

suggested anterior skull-base involvement with adjacent dural

contact (Fig. 2). A working

diagnosis of a tumor-related stroke was considered;

oligodendroglioma and meningioma were included in the

differential.

On hospital day 5, after exclusion of surgical

contraindications, the patient underwent a craniotomy for tumor

resection. Intraoperatively, a solid, firm, hypervascular mass

without a discrete capsule was identified with invasion of the

anterior skull-base dura. Fluorescein sodium aided delineation of

the tumor-brain interface, and a gross total resection was

achieved. The cut surface was soft and gelatinous. Dural defects

were repaired with artificial dura. Postoperatively, the patient

was transferred to the intensive care unit for ventilatory

support.

At 24 h post-surgery, the patient was somnolent with

a Glasgow Coma Scale score of E3V5M6 and proximal limb strength of

5- (6,7). Follow-up CT demonstrated a hematoma

with progressive fluid accumulation within the resection cavity

when compared with immediate postoperative imaging. By

postoperative day 3, after discontinuation of therapeutic

hypothermia, the patient's temperature peaked at 37.5°C and the

clinical status stabilized, permitting transfer to the general

ward.

On postoperative day 5, a high-grade fever and

incisional discharge prompted a lumbar puncture, which showed

elevated opening pressure and marked cerebrospinal-fluid

pleocytosis. Culture of the fluid grew methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus, confirming postoperative bacterial

meningitis. The patient received intravenous meropenem (1 g every 8

h) and vancomycin (1 g every 12 h); defervescence and wound

resolution were achieved after 6 days.

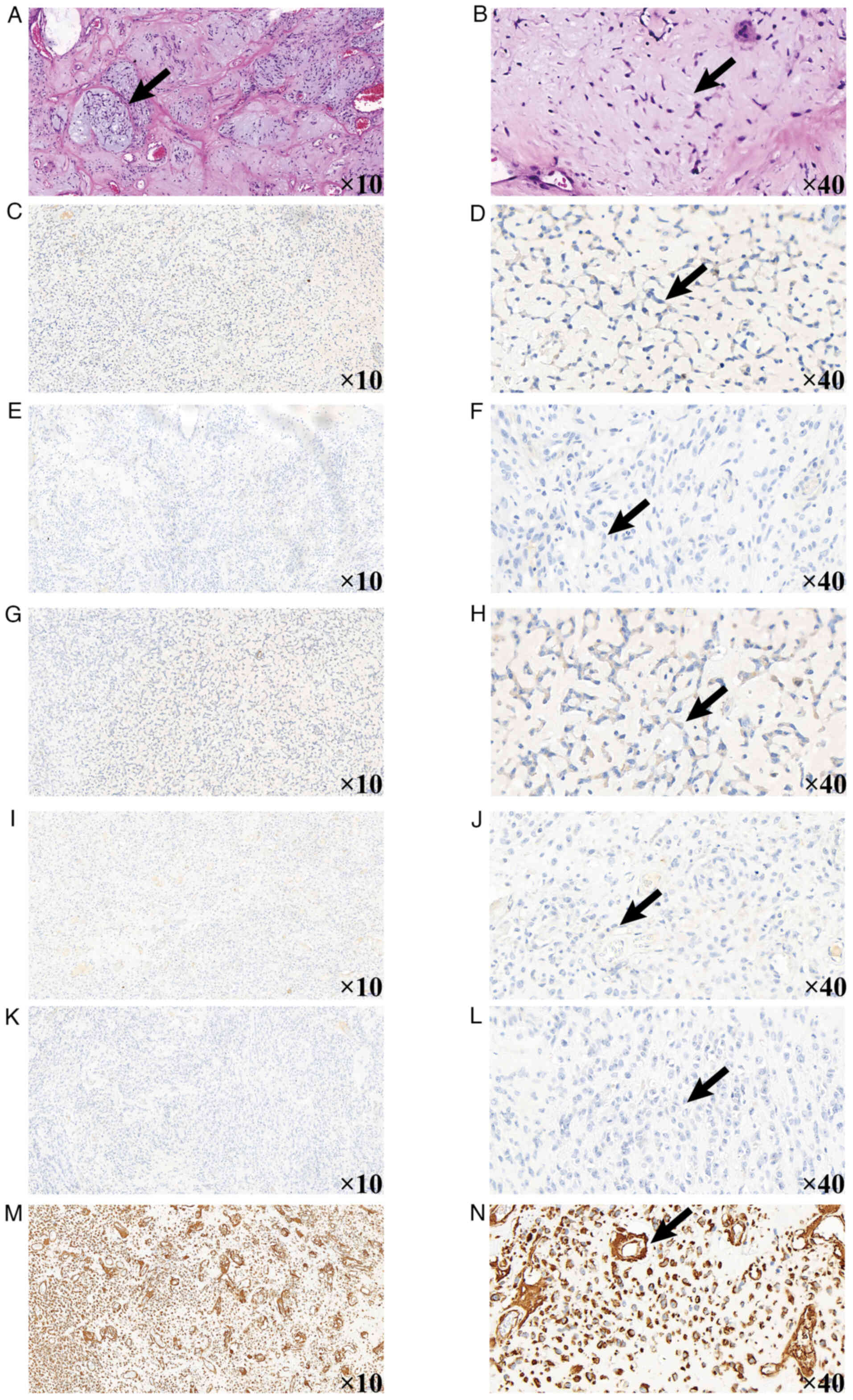

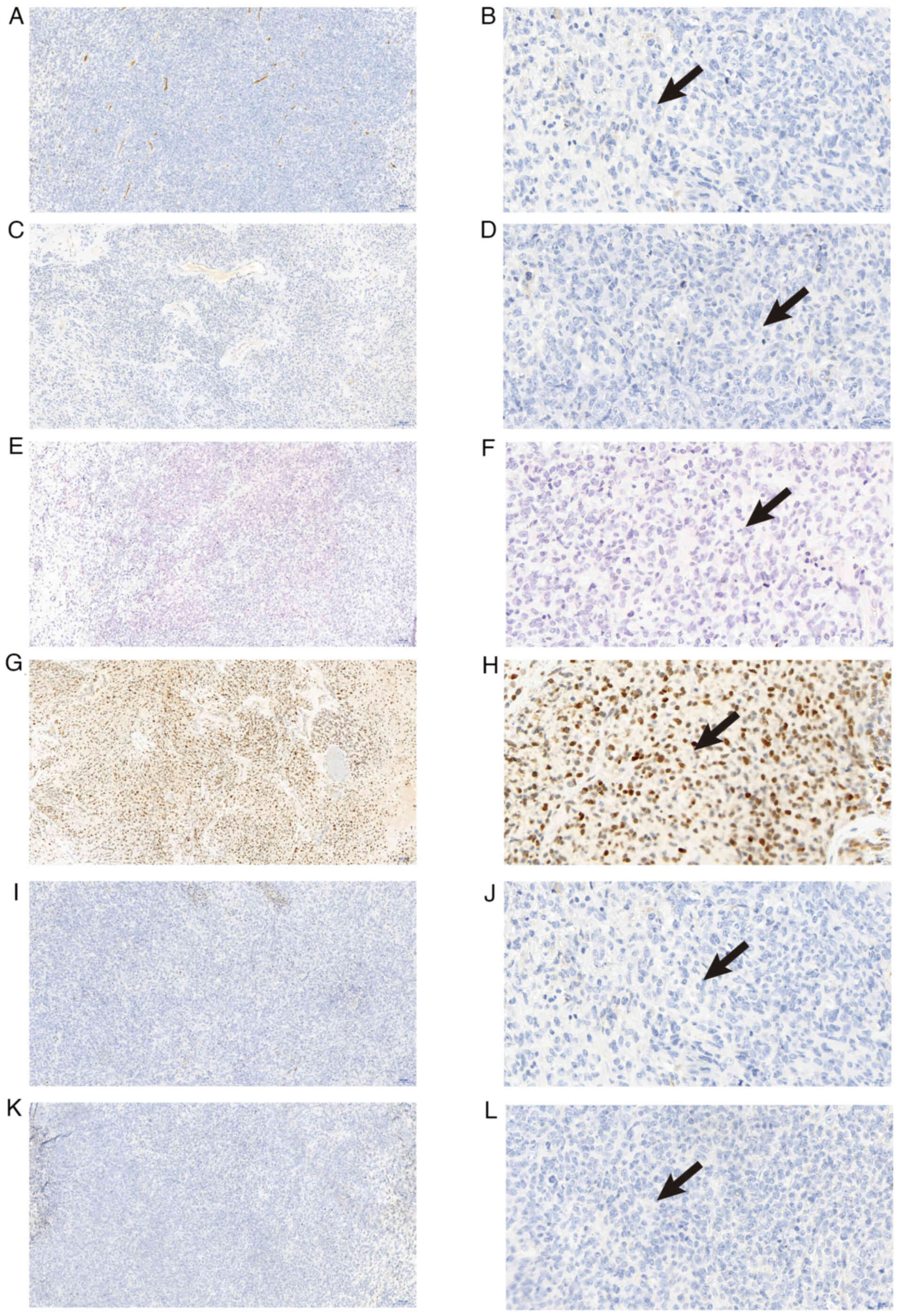

On postoperative day 16, histopathological analysis

established a diagnosis of EMC. Tissue samples were fixed in 4%

Paraformaldehyde Fix Solution (cat. no. P0099-500 ml; Beyotime

Biotechnology) at room temperature for 24 h, followed by routine

dehydration and embedding in paraffin. Sections were cut at a

thickness of 3 µm and mounted on slides. To minimize non-specific

background, sections were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in

PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The Roche BenchMark automated

staining platform was used according to the manufacturer's

instructions, with the following ready-to-use primary antibodies,

incubated at room temperature for 32 min: p53 (cat. no. 61209507;

Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), vimentin (cat.

no. ZM-0260; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.),

Ki-67 (Gene Tech Co., Ltd.; cat. no. GT209407), CK(Pan) (GeneTech

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. GM351507), INI1 (Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. ZA-0696), S100 (Beijing Zhongshan

Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. ZA-0225), Desmin

(GeneTech Co., Ltd.; cat. no. GT225207), EMA (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 24 h-0095), GFAP (cat. no. ZM-0118;

Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), synaptophysin

(cat. no. ZM-0246; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.), CD34 (GeneTech Co., Ltd.; cat. no. GM716507), IDH1 (Beijing

Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. ZM-0447), SOX10

(cat. no. ZA-0624; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.), STAT6 (cat. no. ZA-0647; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), NKX2.2 (cat. no. ZA-0655; Beijing

Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and SMA (cat. no.

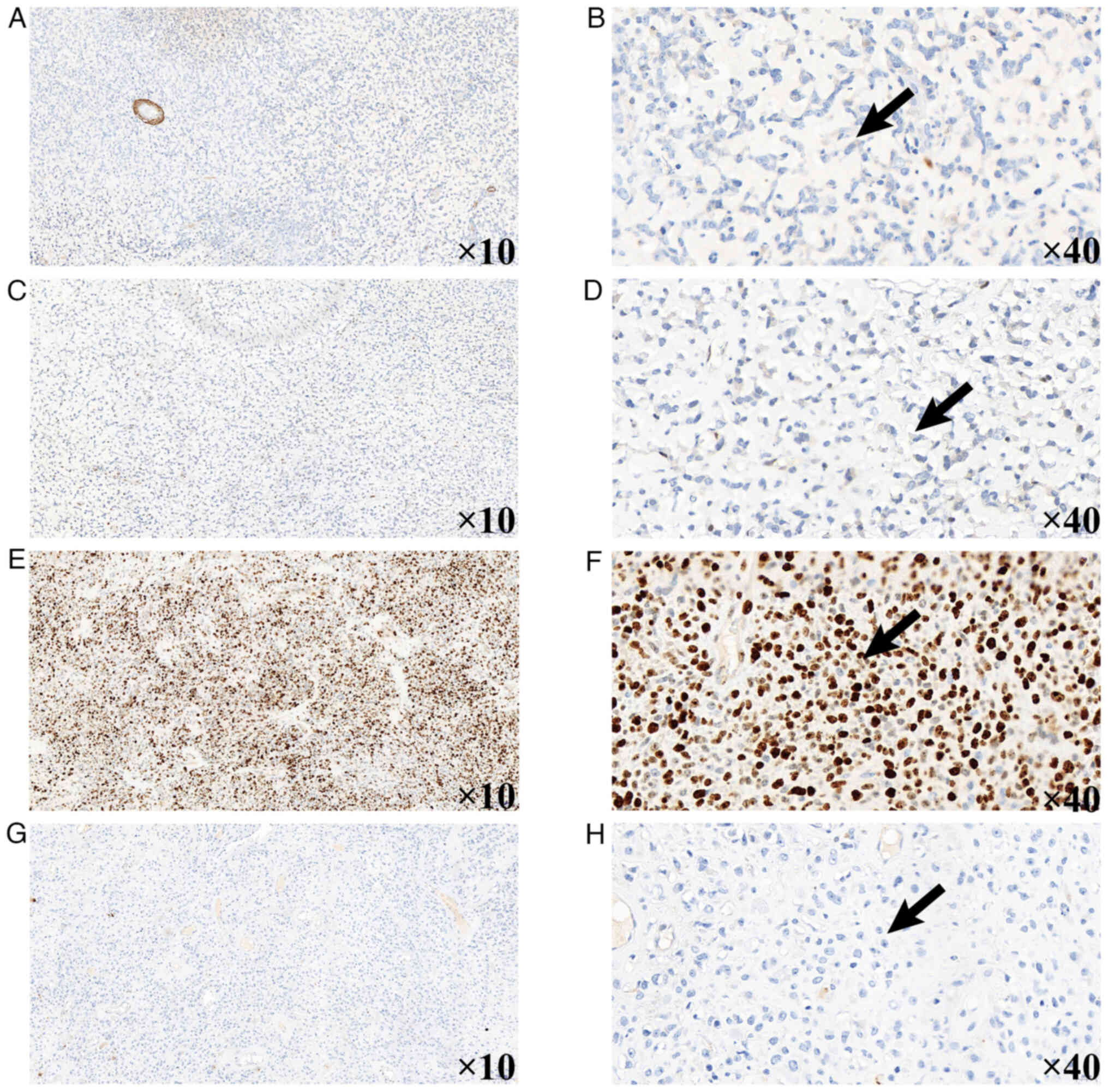

Kit-0006/MAB-0890; Abcam). Immunohistochemical analysis showed the

following results: S-100(−), integrase interactor 1 (INI1)(−),

cytokeratin (CK)(−), smooth muscle actin (SMA)(−), desmin(−),

CD34(−), STAT6(−), homeobox protein Nkx-2.2 (NKX2.2)(−),

transcription factor SOX-10 (SOX10)(−), synaptophysin(−),

epithelial membrane antigen (EMA)(−), glial fibrillary acidic

protein (GFAP)(−), diffuse vimentin(+), p53(+, 60%), isocitrate

dehydrogenase 1 (IDH-1)(−) and a Ki-67 labeling index of 80%

(Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig.

5). NR4A3 fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was

recommended to confirm the molecular subtype, but was declined due

to financial constraints and concerns about invasive testing.

After discontinuation of intensive antimicrobial

therapy, the patient remained afebrile. Following a 23-day

hospitalization period, the patient was discharged with baseline

neurological function restored. Discharge medications included 30

mg oral idebenone three times daily and 0.2 g oral citicoline

sodium three times daily; neurosurgical follow-up was scheduled for

surveillance.

Approximately 1 month postoperatively, the patient

was readmitted for adjuvant radiotherapy (RT). Baseline

hematological parameters were within reference ranges: Red blood

cells, 4.71×10¹2/l (normal range,

4.0–5.5×10¹2/l); hemoglobin, 142 g/l (normal range,

130–175 g/l); platelets, 285×109/l (normal range,

125–350×109/l); and leukocytes, 8.36×109/l

(normal range, 4.0–10.0×109/l).

Simulation CT (3-mm slice thickness) was acquired

with the patient in a supine position and immobilized in a

thermoplastic mask. The tumor bed and contrast-enhancing region

were contoured as the gross tumor volume with a 3-mm margin to

generate the planning gross tumor volume (59.40 Gy in 33

fractions). Preoperative edema and enhancing dura defined the

clinical target volume; a further 3-mm margin produced the planning

target volume (PTV) (66 Gy in 33 fractions). Treatment-planning

verification confirmed ≥95% isodose coverage of the PTV with

organ-at-risk doses within institutional constraints.

Hematological indices were monitored throughout RT

and showed a mild downward trend consistent with non-actionable

myelosuppression (week 7: hemoglobin, 140 g/l; platelets,

238×109/l; and leukocytes, 4.83×109/l). No

laboratory threshold for intervention was reached.

During the course of radiotherapy, adjunctive

osmotherapy with intravenous 20% mannitol (125 ml every 8 h) was

administered to manage perilesional edema. The patient's Eastern

Cooperative Oncology Group performance status remained at 1

(8), and no radiation-induced

dermatitis or neurological toxicity was observed.

Post-RT MRI demonstrated substantial resolution of

the postoperative hematoma and associated fluid collections

(Fig. 6). Given the high-risk

pathological features (INI1 loss and Ki-67 at 80%) and the limited

responsiveness of EMC to conventional chemotherapy reported in the

literature, a multidisciplinary team concluded that adjuvant

chemotherapy would provide no clear clinical benefit; systemic

therapy was therefore not pursued, and the patient was discharged.

The patient's long-term prognosis remains uncertain, and imaging

surveillance is planned at 3- to 6-month intervals for 2 years and

annually thereafter.

Discussion

EMC is a rare soft-tissue sarcoma, accounting for

2.5–3% of all soft-tissue sarcomas. EMC is classified by the World

Health Organization as a ‘mesenchymal tumor of uncertain

differentiation’ (9).

Pathologically, EMC exhibits a multinodular architecture with a

mucin-rich matrix and chondroid cells showing malignant cytological

features (10). Although initially

regarded as a low-grade neoplasm, subsequent studies have shown a

notable propensity for local recurrence and distant metastasis

(11,12), particularly to the lungs (13). Intracranial EMC is hypothesized to

arise from embryonic remnants within cranial bones or from

pluripotent mesenchymal cells in the dura mater (14). EMC most often affects middle-aged

men and typically presents as a slowly enlarging, painless,

deep-seated mass in the proximal limbs (9). By contrast, intracranial lesions

usually have an insidious onset with non-specific symptoms,

frequently delaying the diagnosis.

The present study reports a rare case of

intracranial EMC in a 17-year-old male patient; to the best of our

knowledge, only 16 comparable cases have been reported worldwide

(Table I). The present case adds to

the spectrum of primary intracranial EMC, a review of which is

summarized in Table I (5,14–28).

The current patient presented with an acute headache, in contrast

to the classically indolent course of EMC. Imaging disclosed a

large right frontal mass (7.2×5.2 cm) with intralesional hemorrhage

and invasion of the anterior cranial-fossa dura. Notably, the

supratentorial location challenges the conventional expectation

that intracranial EMCs predominantly arise in the posterior cranial

fossa; fewer than 5 supratentorial cases have been documented

(17,28). Postoperative histopathology

confirmed EMC with loss of INI1 expression and a high Ki-67

labeling index (80%), indicating an aggressive phenotype. The

distinctiveness of this case lies in its adolescent onset (typical

onset, 50–60 years), right frontal location and high proliferative

activity with INI1 loss. The postoperative course was further

complicated by bacterial meningitis, adding to the management

complexity.

| Table I.Reported cases of primary

intracranial extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. |

Table I.

Reported cases of primary

intracranial extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma.

| First author/s,

year | Sex | Age, years | Clinical

symptoms | Size, cm | Locations of

tumor | Treatment | Recurrence | Metastasis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Scott et al,

1976 | M | 39 | Headache, nausea

and vomiting | NA | 4th ventricle | PR | N | N | (15) |

| Smith and Davidson,

1981 | M | 12 | Headache, nausea,

vomiting and difficulty ambulating | 3.5×1.0×0.5 | Left

cerebellum | GTR | N | N | (16) |

| Salcman et

al, 1992 | F | 28 | Headache, slow

speech and right limb weakness | 7.0×5.0×4.0 | Left parafalcine

region | GTR | Y | N | (17) |

| Sato et al,

1993 | F | 43 | Blurred vision and

gait disturbance | NA | Pineal region | PR, RT (60 Gy),

chemotherapy | Y | Y | (18) |

| Chaskis et

al, 2002 | F | 17 | Headache and status

epilepticus | NA | Right

frontal-parietal lobe | GTR | Y | N | (14) |

| González-Lois et

al, 2002 | M | 69 | Headache, dizziness

and behavior change | NA | Right frontal

lobe | GTR | N | N | (19) |

| Im et al,

2003 | M | 43 | Headache, nausea

and vomit | 2.0 | Left parietal

lobe | GTR, RT (59.4

Gy) | N | N | (20) |

| Cummings et

al, 2004 | M | 63 | Hearing loss and

gait disturbance | 2.4×1.8×2.4 | Right jugular

foramen, right Cerebellopontine Angle (CPA) | GTR | NA | NA | (21) |

| Sorimachi et

al, 2008 | F | 37 | Headache, nausea,

vomit and upward gaze palsy | NA | Pineal region | GTR, RT (59.4

Gy) | N | N | (22) |

| O'Brien et

al, 2008 | F | 26 | Headache, nausea

and seizure | 2.5 | Left CPA | STR proton

therapy | N | N | (23) |

| Arpino et

al, 2011 | F | 54 | Headache and left

ophthalmoplegia | NA | Sellar and

parasellar area | GTR | NA | NA | (24) |

| Dulou et al,

2012 | F | 70 | Behavior change and

difficulty in walking | NA | Left frontal

lobe | GTR, preoperative

RT (60 Gy) | Y | N | (25) |

| Park et al,

2012 | F | 21 | Headache, right

limb weakness, bilateral hearing loss and bilateral vision

loss | 3.2×6.3×4.9 | Left lateral

ventricle | GTR, RT (60.8

Gy) | NA | NA | (26) |

| Qin et al,

2017 | F | 41 | Headache and

vomiting | 3.0×3.0×3.0 | Left

cerebellum | GTR, two stage RT

(56 Gy/50 Gy), chemo | N | N | (27) |

| Akakin et

al, 2018 | F | 75 | Right limb

weakness | NA | Left parafalcine

region | GTR | Y | N | (28) |

| Zhu et al,

2022 | M | 52 | Headache, dizzy and

nausea | 3.4×3.0 | Left cavernous

sinus | GTR, RT (45

Gy) | N | N | (5) |

| Present case | M | 17 | Headache, nausea

and vomiting | 7.2×5.2 | Right frontal

lobe | GTR, RT (59.4

Gy) | N | N |

|

The present case underscores the pronounced clinical

and pathological heterogeneity of EMC. An accurate diagnosis

requires an integrated, multimodal assessment.

Immunohistochemically, the tumor showed diffuse vimentin

positivity, consistent with mesenchymal differentiation, and was

negative for S-100, aligning with the frequently low rate of S-100

expression reported in intracranial EMCs (28,29)

(Table II). The

immunohistochemical profile of the present case aligns with

reported intracranial EMCs, with a detailed comparison provided in

Table II (5,16–20,22,23,25–28).

| Table II.Immunohistochemical features of

intracranial myxoid chondrosarcomas in reported cases. |

Table II.

Immunohistochemical features of

intracranial myxoid chondrosarcomas in reported cases.

| First author,

year | GFAP | Cytokeratin | EMA | S-100 | Vimentin | NSE | Synaptophysin | Chromogranin A | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Smith and Davidson,

1981 | (−) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (16) |

| Salcman et

al, 1992 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (++) |

|

|

| (17) |

| Sato et al,

1993 | (−) |

|

| (++) | (++) |

|

|

| (18) |

| González-Lois et

al, 2002 | (+) | (−) | (−) | (+), focal | (+) | (−) |

|

| (19) |

| Im et al,

2003 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+), weak | (+) |

|

|

| (20) |

| Sorimachi et

al, 2008 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (22) |

| O'Brien et

al, 2008 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (23) |

| Park et al,

2012 | (−) | (+), focal

strong | (+) | (+) |

|

|

|

| (26) |

| Dulou et al,

2012 | (+) | (+), strong | (+), weak |

|

|

|

|

| (25) |

| Qin et al,

2017 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) |

|

|

|

| (27) |

| Akakin et

al, 2018 | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | ND | (−) | (−) | (28) |

| Zhu et al,

2022 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | ND | ND | ND | (5) |

| Present case | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | ND | (−) | ND |

|

Histopathological evaluation of hematoxylin and

eosin (H&E)-stained sections revealed a hypercellular neoplasm

with a multinodular architecture within an abundant myxoid stroma.

Tumor cells were predominantly eosinophilic, ranging from

epithelioid to plump spindle forms, arranged in cords, nests and

reticular patterns. There was marked nuclear atypia, elevated

mitotic activity and foci of hemorrhagic change. A panel of

negative immunomarkers supported systematic exclusion of mimics:

GFAP and SOX10 negativity argued against gliomas and schwannomas

(30); CK and EMA negativity argued

against epithelial tumors and meningiomas (31); synaptophysin, desmin and SMA

negativity argued against neuroendocrine and myogenic neoplasms

(32); and the absence of CD34 and

STAT6 expression did not support a pericytic/solitary fibrous tumor

lineage (33). Furthermore, while

CD99 is a valuable marker in the differential diagnosis of small

round cell tumors, particularly for excluding Ewing sarcoma, it was

not performed in the present retrospective case as the

comprehensive diagnostic workup was already achieved through the

extensive immunohistochemical panel and characteristic

morphological features. However, based on its established role in

differential diagnosis, its inclusion is recommended in a routine

panel. The hemorrhagic transformation may reflect aberrant vascular

proliferation, concordant with the high Ki-67 index (up to 80%) and

strong p53 immunoreactivity (>60%), collectively suggesting

activated angiogenesis-related pathways.

Loss of INI1 expression is infrequently observed in

conventional intracranial EMCs (reported in <10% of cases) but

has been described in high-grade morphological variants with

pronounced atypia and brisk mitotic activity (34). The combination of characteristic

H&E features, multinodular myxoid stroma with corded growth and

the specific immunoprofile is strongly supportive of EMC. Diffuse

vimentin positivity with absent synaptophysin/EMA expression

effectively excludes malignant rhabdoid tumors, while CK negativity

argues against chordoma. In addition, negative NKX2.2 and IDH-1

staining disfavors Ewing's sarcoma and IDH-mutant gliomas,

respectively (35).

The immunoprofile in the present case, namely strong

vimentin positivity, S-100 negativity, synaptophysin negativity and

the absence of lineage-defining markers, closely mirrors reported

intracranial EMCs, including those associated with the TAF15-NR4A3

fusion subtype; in the absence of molecular confirmation, however,

this remains inferential. This fusion subtype accounts for ~20% of

EMCs and has been linked to aggressive clinical behavior and

resistance to pazopanib (36).

Molecular confirmation remains rare in the literature, with

definitive subtyping reported in only 1 of 16 documented

intracranial cases (5). Thus, while

the diagnosis is well supported by histomorphology and

immunohistochemistry, definitive classification would require

genetic confirmation, which was not performed in the present case

(5).

A definitive diagnosis typically requires molecular

detection of NR4A3 rearrangements, most commonly confirmation of

the EWSR1-NR4A3 fusion (37). The

patient's refusal to undergo NR4A3 testing imposed two critical

limitations: First, the TAF15-NR4A3 subtype, which confers relative

resistance to pazopanib, could not be distinguished from the

EWSR1-NR4A3 subtype, precluding accurate molecular subtyping; and

second, prognostication may be less reliable, as patients with

TAF15 fusions have significantly lower 5-year survival rates than

those with EWSR1 fusions.

Given the high-risk pathological features,

management raised three major challenges. First, postoperative

bacterial meningitis, reflected by a cerebrospinal-fluid white-cell

count of 836×106/l, may necessitate delaying RT, thereby

increasing the risk of recurrence. Second, invasion of the

skull-base dura complicates margin assessment and favors the

judicious use of neuronavigation. Third, in this high-risk context,

systemic therapies such as temozolomide or pazopanib merit

consideration; temozolomide penetrates the blood-brain barrier

effectively, whereas pazopanib may be more suitable for patients

lacking the TAF15 fusion. At the 3-month postoperative follow-up,

no recurrence was detected in the present case. Nonetheless,

vigilant long-term surveillance is warranted, as distant metastases

often emerge years after surgery. Proton-beam therapy may offer

dosimetric advantages over conventional RT, but the optimal

strategy requires further evaluation (37).

Imaging findings are pivotal for differential

diagnosis and require synthesis across modalities. CT typically

shows a well-circumscribed hypodense mass, with calcification in

~12.5% of cases (5).

Contrast-enhanced CT often demonstrates mild or absent enhancement

(2). MRI provides greater

diagnostic resolution: Lesions are commonly iso- to hypointense on

T1-weighted sequences, with hemorrhagic foci appearing hyperintense

(38). On T2-weighted imaging, they

are frequently markedly hyperintense with hypointense fibrous

septa, often producing a multiloculated cystic appearance (2,39).

Post-contrast enhancement is typically septal, ring-like or

lobulated; ~10% of cases show minimal or no enhancement (38). The MRI characteristics in the

present case align closely with these descriptors (Table III). The imaging findings in the

present case are consistent with the spectrum of MRI features

summarized in Table III (5,14–28).

| Table III.MRI features of primary intracranial

extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma case. |

Table III.

MRI features of primary intracranial

extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma case.

| First author,

year | T1WI | T2WI | Enhanced MRI | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Scott et al,

1976 | NA | NA | NA | (15) |

| Smith and Davidson,

1981 | NA | NA | NA | (16) |

| Salcman et

al, 1992 | Well-defined,

hyperintensity | Homogeneous

hyperintensity | NA | (17) |

| Sato et al,

1993 | NA | NA | NA | (18) |

| Chaskis et

al, 2002 | Hypointensity | NA | Heterogeneous

enhancement | (14) |

| González-Lois et

al, 2002 | NA | NA | Significantly

homogeneous enhancement | (19) |

| Im et al,

2003 | Unclear-defined,

hypointensity | Hyperintensity | Homogeneously well

enhanced | (20) |

| Cummings et

al, 2004 | NA | NA | Heterogeneous

enhancement | (21) |

| Sorimachi et

al, 2008 | Mixed signal

intensity, hyperintensity (hemorrhage) | NA | Heterogeneous

enhancement | (22) |

| O'Brien et

al, 2008 | Hypointensity | Hyperintensity | NA | (23) |

| Arpino et

al, 2011 | Hypointensity | Hyperintensity | Heterogeneously

peripheral enhancement | (24) |

| Dulou et al,

2012 | NA | Hyperintensity,

peritumor edema | Heterogeneously

ring-like enhancement | (25) |

| Park et al,

2012 | Homogeneous

iso-intensity | Heterogeneous

hyperintensity, Peritumor edema | Heterogeneously

lobulated enhancement | (26) |

| Qin et al,

2017 | NA | NA | NA | (27) |

| Akakin et

al, 2018 | NA | Heterogeneous

hyperintensity | Heterogeneously

rim-like enhancement, DWI showed intratumor calcification | (28) |

| Zhu et al,

2022 | Homogeneous

hypointensity | Heterogeneous

hyperintensity | Heterogeneously

well enhanced | (5) |

| Present case | Hypointensity | Hyperintensity | Heterogeneously

well enhanced |

|

Key differential diagnoses of EMC include chondroid

meningioma, which often exhibits calcification and a characteristic

dural-tail sign (1), ependymoma,

which commonly arises in the fourth ventricle and may disseminate

along cerebrospinal-fluid pathways (38), cavernous hemangioma, which shows a

‘popcorn-like’ mixed T2 signal with a surrounding hemosiderin rim,

and metastatic tumors, which are frequently multiple and typically

associated with substantial vasogenic edema (5).

For clinical practice, heightened vigilance is

warranted when encountering intracranial mucin-rich tumors with

hemorrhage and skull-base invasion in adolescents. A routine

immunohistochemical panel should include vimentin, S-100, CD99 and

INI1, with strong consideration of NR4A3 assessment. Molecular

confirmation is recommended using FISH or RNA sequencing.

Therapeutically, meticulous control of surgical

boundaries at the skull base and timely initiation of RT, at a

recommended dose of 50–54 Gy, are crucial. Systemic options may

include temozolomide or pazopanib. For patients with a relevant

family history, genetic screening should be considered.

The present study has several limitations, including

the absence of NR4A3 fusion testing, a short postoperative

follow-up of only 3 months and the lack of mechanistic validation.

Given that EMC can metastasize years after surgery, long-term

standardized follow-up is essential. Future work should prioritize

establishing a dedicated registry for adolescent EMCs and

investigating age-specific mechanisms, including functional

interrogation of the LSM14A-NR4A3 fusion, the consequences of INI1

loss and strategies for combination immunotherapy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HW designed and conducted the study, collected the

case report data, and analyzed and interpreted the data. HZ

acquired the pathological data. FW contributed to the analysis and

revision of the discussion section and prepared the pathological

images. HW wrote the manuscript, and all authors analyzed the

results and revised the manuscript. HZ made significant

contributions to the conception and design of the study. HW, HZ,

and FW confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital (Yantai, China; approval no.

2025-561).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of any potentially identifiable images

or data included in this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

EMC

|

extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcoma

|

|

MRI

|

magnetic resonance imaging

|

|

RT

|

radiotherapy

|

References

|

1

|

Stacchiotti S, Baldi GG, Morosi C, Gronchi

A and Maestro R: Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: State of the

art and current research on biology and clinical management.

Cancers (Basel). 12:27032020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang L, Wang R, Xu R, Qin G and Yang L:

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: A comparative study of imaging

and pathology. Biomed Res Int. 2018:96842682018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Noguchi H, Mitsuhashi T, Seki K, Tochigi

N, Tsuji M, Shimoda T and Hasegawa T: Fluorescence in situ

hybridization analysis of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas

using EWSR1 and NR4A3 probes. Hum Pathol. 41:336–342. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wei S, Pei J, von Mehren M, Abraham JA,

Patchefsky AS and Cooper HS: SMARCA2-NR4A3 is a novel fusion gene

of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma identified by RNA

next-generation sequencing. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 60:709–712.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhu ZY, Wang YB, Li HY and Wu XM: Primary

intracranial extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: A case report and

review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 10:4301–4313. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nodal S, Khalafallah AM, Sanghera BS,

Garcia Barreto M, Errante EL, Levi AD, Ray WZ and Burks SS: A

meta-analysis and systematic review: Association of timing and

muscle strength after nerve transfer in upper trunk palsy.

Neurosurg Rev. 48:5032025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mehta R and Chinthapalli K: Glasgow coma

scale explained. BMJ. 365:l12962019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kandoussi AE, Hung YP, Tung EL, Bauer F,

Vicentini JRT, Lozano-Calderon S and Chang CY: Clinical, imaging

and pathological features of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma.

Skeletal Radiol. 54:959–966. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Okamoto S, Hisaoka M, Ishida T, Imamura T,

Kanda H, Shimajiri S and Hashimoto H: Extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcoma: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and

molecular analysis of 18 cases. Hum Pathol. 32:1116–1124. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Giner F, López-Guerrero JA, Machado I,

Rubio-Martínez LA, Espino M, Navarro S, Agra-Pujol C, Ferrández A

and Llombart-Bosch A: Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: p53 and

Ki-67 offer prognostic value for clinical outcome-an

immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 31 cases. Virchows

Arch. 482:407–417. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ulucaköy C, Atalay İB, Yapar A, Kaptan AY,

Bingöl İ, Doğan M and Ekşioğlu MF: Surgical outcomes of

extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Turk J Med Sci. 52:1183–1189.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fice MP, Lee L, Kottamasu P, Almajnooni A,

Cohn MR, Gusho CA, Gitelis S and Blank AT: Extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcoma: A case series and review of the literature. Rare

Tumors. 14:203636132210797542022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chaskis C, Michotte A, Goossens A, Stadnik

T, Koerts G and D'Haens J: Primary intracerebral myxoid

chondrosarcoma. Case illustration. J Neurosurg. 97:2282002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Scott RM, Dickersin R, Wolpert SM and

Twitchell T: Myxochondrosarcoma of the fourth ventricle. Case

report. J Neurosurg. 44:386–389. 1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Smith TW and Davidson RI: Primary

meningeal myxochondrosarcoma presenting as a cerebellar mass: Case

report. Neurosurgery. 8:577–581. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Salcman M, Scholtz H, Kristt D and

Numaguchi Y: Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma of the falx.

Neurosurgery. 31:344–348. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sato K, Kubota T, Yoshida K and Murata H:

Intracranial extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma with special

reference to lamellar inclusions in the rough endoplasmic

reticulum. Acta Neuropathol. 86:525–528. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

González-Lois C, Cuevas C, Abdullah O and

Ricoy JR: Intracranial extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: Case

report and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien).

144:735–740. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Im SH, Kim DG, Park IA and Chi JG: Primary

intracranial myxoid chondrosarcoma: Report of a case and review of

the literature. J Korean Med Sci. 18:301–307. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cummings TJ, Bridge JA and Fukushima T:

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma of the jugular foramen. Clin

Neuropathol. 23:232–237. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sorimachi T, Sasaki O, Nakazato S, Koike T

and Shibuya H: Myxoid chondrosarcoma in the pineal region. J

Neurosurg. 109:904–907. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

O'Brien J, Thornton J, Cawley D, Farrell

M, Keohane K, Kaar G, McEvoy L and O'Brien DF: Extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcoma of the cerebellopontine angle presenting during

pregnancy. Br J Neurosurg. 22:429–432. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Arpino L, Capuano C, Gravina M and Franco

A: Parasellar myxoid chondrosarcoma: A rare variant of cranial

chondrosarcoma. J Neurosurg Sci. 55:387–389. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Dulou R, Chargari C, Dagain A, Teriitehau

C, Goasguen O, Jeanjean O and Védrine L: Primary intracranial

extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Neurol Neurochir Pol.

46:76–81. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Park JH, Kim MJ, Kim CJ and Kim JH:

Intracranial extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: Case report and

literature review. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 52:246–249. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Qin Y, Zhang HB, Ke CS, Huang J, Wu B, Wan

C, Yang CS and Yang KY: Primary extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma

in cerebellum: A case report with literature review. Medicine

(Baltimore). 96:e86842017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Akakın A, Urgun K, Ekşi M, Yılmaz B,

Yapıcıer Ö, Mestanoğlu M, Toktaş ZO, Demir MK and Kılıç T: Falcine

myxoid chondrosarcoma: A rare aggressive case. Asian J Neurosurg.

13:68–71. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kallen ME and Hornick JL: The 2020 WHO

classification: What's new in soft tissue tumor pathology? Am J

Surg Pathol. 45:e1–e23. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tekavec K, Švara T, Knific T, Gombač M and

Cantile C: Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of

canine nerve sheath tumors and proposal for an updated

classification. Vet Sci. 9:2042022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sarathy D, Snyder MH, Ampie L, Berry D and

Syed HR: Dural convexity chondroma mimicking meningioma in a young

female. Cureus. 13:e207152021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bellizzi AM: An algorithmic

immunohistochemical approach to define tumor type and assign site

of origin. Adv Anat Pathol. 27:114–163. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Almaghrabi A, Almaghrabi N and Al-Maghrabi

H: Glomangioma of the kidney: A rare case of glomus tumor and

review of the literature. Case Rep Pathol.

2017:74236422017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Velz J, Agaimy A, Frontzek K, Neidert MC,

Bozinov O, Wagner U, Fritz C, Coras R, Hofer S, Bode-Lesniewska B

and Rushing E: Molecular and clinicopathologic heterogeneity of

intracranial tumors mimicking extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma.

J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 77:727–735. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu Z, Bian J, Yang Y, Wei D and Qi S:

Ewing sarcoma of the pancreas: A pediatric case report and

narrative literature review. Front Oncol. 14:13685642024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dulken BW, Kingsley L, Zdravkovic S,

Cespedes O, Qian X, Suster DI and Charville GW: CHRNA6 RNA in situ

hybridization is a useful tool for the diagnosis of extraskeletal

myxoid chondrosarcoma. Mod Pathol. 37:1004642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ngo C, Verret B, Vibert J, Cotteret S,

Levy A, Pechoux CL, Haddag-Miliani L, Honore C, Faron M, Quinquis

F, et al: A novel fusion variant LSM14A::NR4A3 in extraskeletal

myxoid chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 62:52–56. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wilbur HC, Robinson DR, Wu YM, Kumar-Sinha

C, Chinnaiyan AM and Chugh R: Identification of novel PGR-NR4A3

fusion in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma and resultant patient

benefit from tamoxifen therapy. JCO Precis Oncol. 6:e22000392022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hong YG, Yoo J, Kim SH and Chang JH:

Intracranial extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma in fourth

ventricle. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 9:75–80. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|