Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most common extracranial

solid tumor in children, accounting for 8–10% of all pediatric

cancers and 15% of cancer-related deaths worldwide (1,2).

According to the Global Burden of Disease 2021 report, the

incidence rate increased from 0.25 cases per 100,000 individuals in

1990 to 0.28 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2021, representing an

overall increase of 12% (3). NB,

which originates from neural crest cells of the sympathetic nervous

system, is a biologically and clinically heterogeneous tumor.

High-risk NB (HR-NB), which constitutes ~50% of new diagnoses,

typically presents with metastases (e.g. bone marrow [BM], bone and

lymph node metastases), MYCN proto-oncogene bHLH transcription

factor (MYCN) amplification or unfavorable histological features.

These factors are strongly associated with a poor prognosis, with a

5-year overall survival (OS) rate of <50% (4,5).

Despite intensive therapy, relapsed or refractory (R/R) disease

remains the primary cause of treatment failure, and ~60% of HR

patients experience disease recurrence. The survival rate following

relapse is <20%, highlighting the urgent need for novel and more

effective therapeutic strategies (6).

Immunotherapy, particularly targeting

disialoganglioside GD2, which is highly expressed on NB cells, has

emerged as a promising option for R/R NB. Dinutuximab beta, a

monoclonal GD2-targeting antibody, was approved in China in August

2021 for treating patients with HR-NB who were ≥12 months old,

including R/R patients (7). The

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend the use

of anti-GD2 immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy to

enhance tumor remission and survival in patients with R/R NB

(8). An increasing number of

studies have also provided empirical medical evidence for the

treatment strategy of chemoimmunotherapy. The BEACON-Immuno phase

II trial showed that dinutuximab beta plus temozolomide/topotecan

improved overall response rate (ORR) by 17% and 1-year

progression-free survival (PFS) rate from 27 to 57% compared with

chemotherapy alone (9). Two other

studies have also provided supportive evidence for the efficacy of

chemoimmunotherapy in R/R NB. A phase II Children's Oncology Group

study demonstrated that dinutuximab combined with irinotecan,

temozolomide and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

(GM-CSF) was tolerable and resulted in clinically meaningful

responses in heavily pretreated patients (10), while a recent meta-analysis reported

that GD2-targeting monoclonal antibody therapy combined with

chemotherapy significantly improved tumor remission rates,

event-free survival and OS in this population (11). A retrospective study of dinutuximab

beta combined with chemotherapy in R/R NB showed 64% of ORR, with

32% achieving complete response (CR). Notably, 31% of responders

achieved a CR or partial response (PR) after 6 to 8 cycles, with

some benefiting from up to 10 cycles of treatment, suggesting that

extended immunotherapy may improve outcomes (12).

Further studies are needed to optimize the duration

of immunotherapy and enhance its efficacy in this

difficult-to-treat population. The present retrospective study

assessed the efficacy and safety of extended treatment cycles of

dinutuximab beta and chemotherapy in patients with R/R NB who had

undergone >5 cycles of dinutuximab beta immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

The present study was a single-center, retrospective

study that included patients with R/R NB who were treated in the

Department of Pediatric Oncology, Shandong Cancer Hospital and

Institute, Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Academy

of Medical Sciences (Jinan, China), between January 2022 and

October 2024. Eligible patients were classified as HR according to

the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) Staging System

(13), and were ≥12 months old at

the initiation of dinutuximab beta treatment. Patients with R/R NB

who received >5 cycles of dinutuximab beta were included in the

study. Refractory NB was defined as either the patient that failed

to achieve a PR or CR after induction chemotherapy or one in which

the residual lesion was confirmed as active disease following

induction and consolidation therapy [as assessed by

18F-NOTATATE positron emission tomography/computed

tomography (PET/CT), iodine-123 or iodine-131

meta-iodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy, or biopsy]. Relapsed NB was

defined as the patient that achieved a CR after previous intensive

multimodal treatment for 4 weeks, followed by the emergence of new

active lesions. Patients with concurrent malignancies other than NB

or those who had not ended dinutuximab beta immunotherapy were

excluded. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Academy of Medical

Sciences (approval no. SDTHEC202503192).

Treatment regimen

The treatment regimen included dinutuximab beta

combined with chemotherapy, GM-CSF and isotretinoin. Dinutuximab

beta was administered through central venous access as a continuous

long-term infusion at a dose of 10 mg/m2/day from days 1

to 10 of each 35-day cycle. GM-CSF was administered at a dose of

250 µg/m2/day from days 6 to 12. GM-CSF was discontinued

if the absolute neutrophil count was >20×109/l.

Isotretinoin was orally administered at a dose of 160

mg/m2/day, in two divided doses from days 15 to 28.

Chemotherapy was also administered, and the regimens were mainly

temozolomide-based, including 1.5 mg/m2 vincristine on

day 1, 50 mg/m2 irinotecan on days 1 to 5, 100

mg/m2 temozolomide on days 1 to 5

(vincristine-irinotecan-temozolomide [VIT] regimen), or

platinum-based chemotherapy. The latter included the DE regimen,

consisting of cisplatin at 20 mg/m2 and etoposide at 100

mg/m2, both administered on days 1 to 4, the OPET

regimen, consisting of vincristine at 1.5 mg/m2 on day

1, cisplatin at 25 mg/m2, etoposide at 100

mg/m2 and temozolomide at 100 mg/m2, each

administered on days 1 to 3, and the OPEC regimen, consisting of

vincristine at 1.5 mg/m2 on day 1, cisplatin at 25

mg/m2, etoposide at 100 mg/m2 and

cyclophosphamide at 400 mg/m2, each administered on days

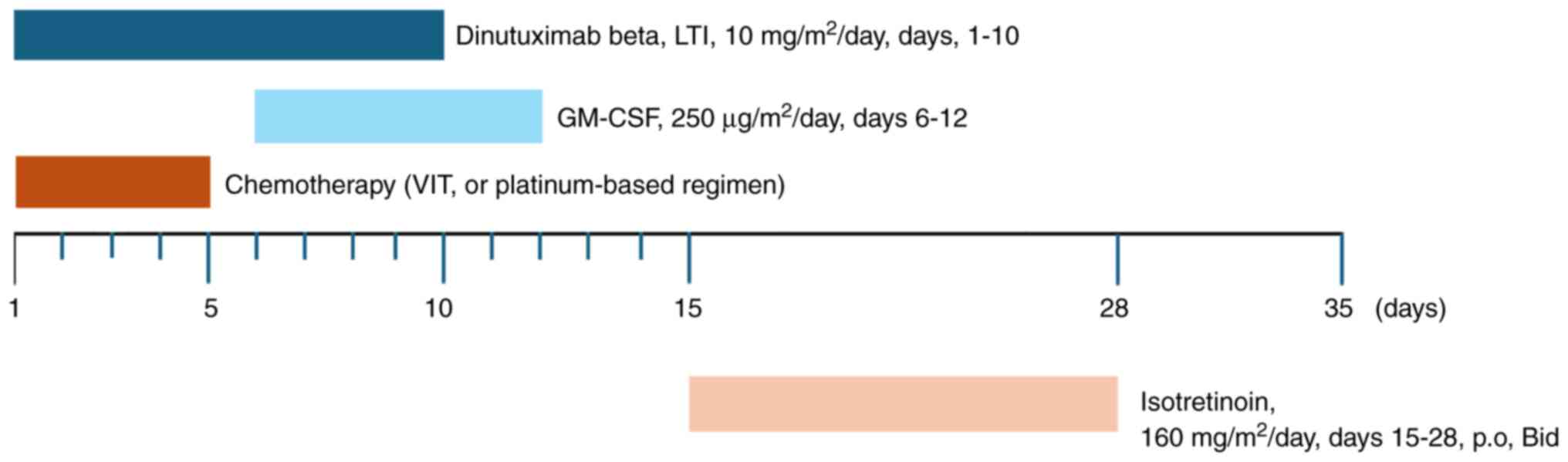

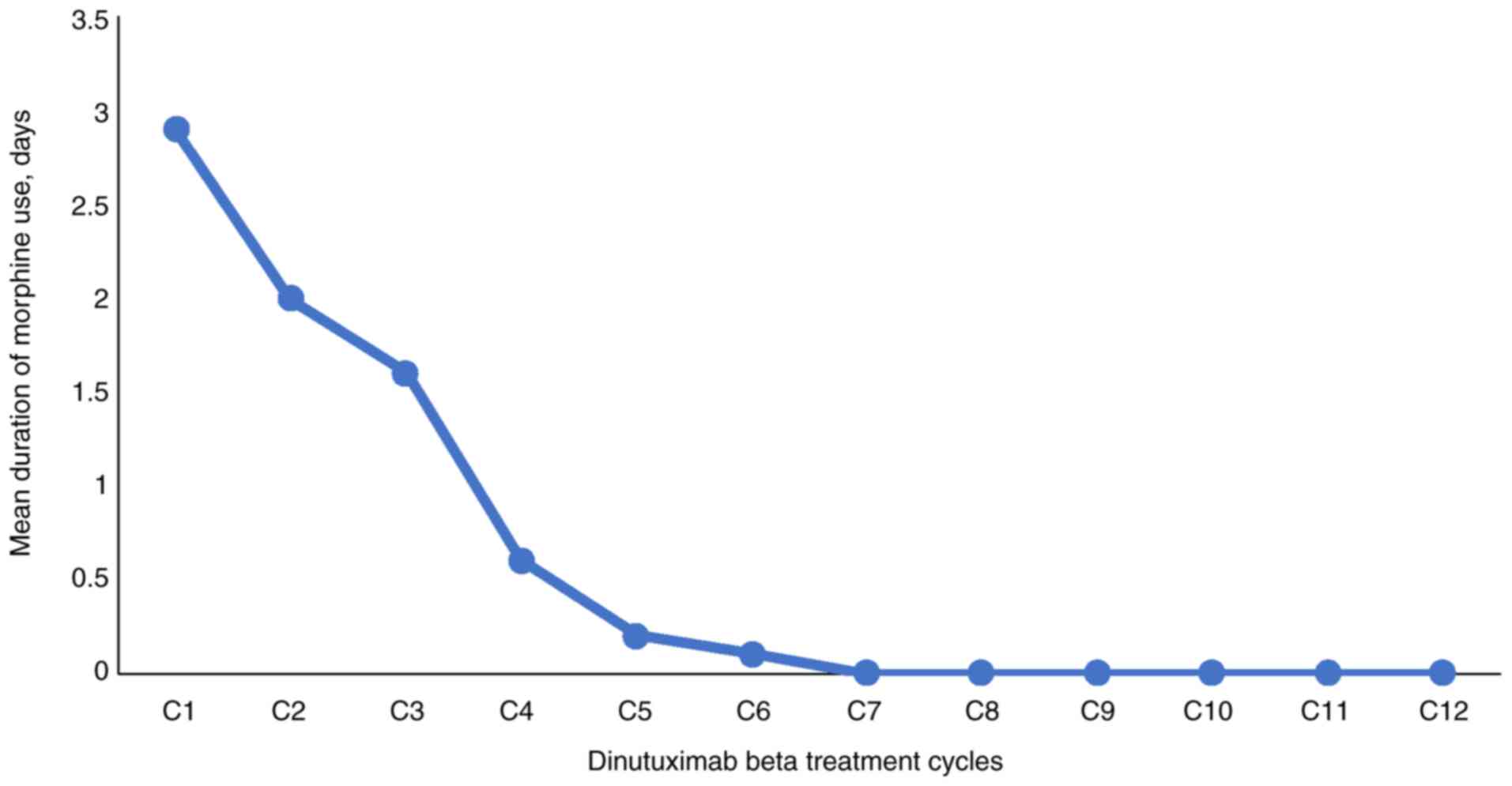

1 to 3. The treatment regimen is illustrated in Fig. 1.

| Figure 1.Treatment regimens and dosing

schedules of chemoimmunotherapy used in relapsed or refractory

neuroblastoma. The VIT regimen consisted of 1.5 mg/m2

vincristine on day 1, 50 mg/m2 irinotecan on days 1–5

and 100 mg/m2 temozolomide on days 1–5. The

platinum-based regimens included DE (20 mg/m2 cisplatin

on days 1–4 and 100 mg/m2 etoposide on days 1–4), OPET

(1.5 mg/m2 vincristine on day 1, 25 mg/m2

cisplatin on days 1–3, 100 mg/m2 etoposide on days 1–3

and 100 mg/m2 temozolomide on days 1–3) or OPEC (1.5

mg/m2 vincristine on day 1, 25 mg/m2

cisplatin on days 1–3, 100 mg/m2 etoposide on days 1–3

and 400 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide on days 1–3). LTI,

long-term infusion; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor; p.o., oral; Bid, twice a day. |

Regarding dinutuximab beta immunotherapy, if a CR

was achieved after 5 cycles, an additional 2 to 4 cycles could be

administered based on the clinical evaluation and patients

conditions, to maintain CR and eradicate minimal residual disease.

If a CR was not achieved, in consideration of the absence of other

treatment measures with greater advantages, it was recommended to

extend the immunotherapy cycles of dinutuximab beta and evaluate

once every 2 or 3 cycles until the best response was achieved, or

until disease progression or intolerable toxicity.

Assessment and outcomes

The overall tumor response was assessed using the

revised International Neuroblastoma Response Criteria (14). BM involvement was detected by the

presence of tumor cells in the BM by immunocytology and

immunohistochemistry. Bone and soft tissues were evaluated using

18F-NOTATATE-PET/CT imaging. Owing to the unavailability

of 68Ga, the 18F-NOTATATE-PET/CT imaging

technique is adopted for tumor assessment in Shandong Cancer

Hospital and Institute. The imaging mechanism is comparable with

that of 68Ga-DOTATATE-PET/CT (15,16),

as both involve the imaging of octreotide derivatives.

The primary outcome was the best ORR (most favorable

response achieved by a patient at any time during the treatment

period, calculated as the proportion of patients with best

response) during the immunotherapy period. The secondary outcomes

were ORR [proportion of patients achieving a tumor response (CR or

PR)], disease-control-rate (DCR), PFS, OS and safety. The best

response was defined as the most favorable tumor response observed

from the initiation of immunotherapy to the end of therapy. PFS

time was defined as the time from the initiation of dinutuximab

beta to disease progression or death from any cause, or until the

last contact with the patient. OS time was defined as the time from

the initiation of dinutuximab beta to death from any cause, or

until the last contact with the patient.

Patients were monitored for adverse events (AEs)

following the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

Version 5.0 (17), Grade ≥3

treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) were reported.

Statistical analysis

Patients with residual disease prior to

immunotherapy were included in the ORR and DCR analyses, assuming a

binomial distribution with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). PFS and

OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with comparisons

via log-rank test. The 2-year PFS and OS rates were reported with

95% CIs. Stratified analysis assessed PFS and OS based on

pre-immunotherapy disease status (CR vs. non-CR). Cox proportional

hazards regression analysis was performed to assess the prognostic

impact of clinical outcomes. Median follow-up was estimated using

the inverse Kaplan-Meier method. All analyses were conducted using

SPSS v22.0 (IBM Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 30 patients were included, with a median

age at diagnosis of 3.9 years (range, 0.6–9.7 years), and a median

age at the initiation of dinutuximab beta treatment of 5.1 years

(range, 2.0–11.1 years). Among them, 24 patients (80%) had

refractory NB and 6 patients (20%) had relapsed NB. Furthermore, 3

patients (10%) had MYCN amplification, 13 patients (43.3%) had 11q

deletion and 3 patients (10%) had 1p deletion. All patients were

diagnosed as stage 4 according to the International Neuroblastoma

Staging System, and stage M according to the INRG Staging System. A

total of 28 patients (93.3%) were observed with a primary tumor in

the abdomen. The baseline characteristics are presented in Table I.

| Table I.Patient (n=30) and disease

characteristics. |

Table I.

Patient (n=30) and disease

characteristics.

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

| Median

age at diagnosis (range) | 3.9 (0.6–9.7) |

| Median

age at the initiation of dinutuximab beta treatment (range) | 5.1 (2.0–11.1) |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

Female | 13 (43.3) |

| Male | 17 (56.7) |

| Disease type, n

(%) |

|

|

Relapsed | 6 (20.0) |

|

Refractory | 24 (80.0) |

| MYCN status, n

(%) |

|

|

Amplified | 3 (10.0) |

|

Non-amplified | 27 (90.0) |

|

Unknown | 0 (0.0) |

| 11q deletion, n

(%) |

|

|

Yes | 13 (43.3) |

| No | 11 (36.7) |

|

Unknown | 6 (20.0) |

| 1p deletion, n

(%) |

|

|

Yes | 3 (10.0) |

| No | 21 (70.0) |

| Unknown | 6 (20.0) |

| INSS stage at

diagnosis, n (%) |

|

| Stage

4 | 30 (100.0) |

| INRG stage at

diagnosis, n (%) |

|

| Stage

M | 30 (100.0) |

| Primary tumor

localization, n (%) |

|

|

Abdomen | 28 (93.3) |

|

Chest | 1 (3.3) |

|

Neck | 0 (0.0) |

|

Other | 1 (3.3) |

Prior to dinutuximab beta treatment, 10 patients

(33.3%) had no residual disease and achieved a CR, 2 patients

(6.7%) achieved a PR, 14 patients (46.7%) achieved a minor response

and 4 patients (13.3%) experienced progressive disease (PD). Among

the 20 patients with residual disease, 12 (60%) had bone metastases

solely, 4 (20%) had both bone and soft tissue metastases, 2 (10%)

had bone and BM metastases, 1 patient (5%) had BM metastasis

solely, and 1 patient (5%) had bone, soft tissue and BM metastases

together. Additionally, 23 of the total patients (76.7%) had

undergone stem cell transplantation, and 28 patients (93.3%) had

undergone radiation therapy. All patients had received chemotherapy

in their previous treatment, and the median number of cycles of

previous chemotherapy was 10. All patients received dinutuximab

beta immunotherapy, which was combined with chemotherapy; 26

patients (86.7%) received a temozolomide-based chemotherapy

regimen, whereas 13 patients (43.3%) received a platinum-based

chemotherapy regimen (12 patients received both regimens). All

patients received immunotherapy, with the median number of cycles

of dinutuximab beta treatment being 7 cycles, ranging from 6 to 12

cycles. The median follow-up time was 18 months (range, 9–35

months). The details related to clinical treatment are presented in

Table II.

| Table II.Clinical characteristics and disease

status of all patients (n=30) prior to immunotherapy. |

Table II.

Clinical characteristics and disease

status of all patients (n=30) prior to immunotherapy.

|

Characteristics | Value |

|---|

| Status prior to the

initiation of dinutuximab beta, n (%) |

|

| CR | 10 (33.3) |

| PR | 2 (6.7) |

| MR | 14 (46.7) |

| PD | 4 (13.3) |

| Metastases site

prior to dinutuximab beta treatment, n (%) |

|

| Bone

marrow only | 1 (3.3) |

| Bone

only | 12 (40.0) |

| Bone

and bone marrow | 2 (6.6) |

| Bone

and soft tissue | 4 (13.3) |

| Bone

and soft tissue and bone marrow | 1 (3.3) |

| Stem cell

transplantation, n (%) |

|

| Single

transplantation | 22 (73.3) |

| Tandem

transplantation | 1 (3.3) |

| No

transplantation | 7 (23.3) |

| Radiotherapy, n

(%) |

|

|

Yes | 28 (93.3) |

| No | 2 (6.7) |

| Cycles of previous

chemotherapy, n (%) |

|

|

8-9 | 10 (33.3) |

|

10-12 | 12 (40.0) |

|

13-24 | 8 (26.7) |

|

Median | 10 |

| Cycles of

dinutuximab beta treatment, n (%) |

|

| 6 | 10 (33.3) |

| 7 | 9 (30.0) |

| 8 | 5 (16.7) |

| 9 | 3 (10.0) |

| 10 | 2 (6.7) |

| 12 | 1 (3.3) |

| Median | 7 |

| Chemotherapy

regimena in

combination with dinutuximab beta, n (%) |

|

|

Temozolomide-based

chemotherapy | 26 (86.7) |

|

Platinum-based

chemotherapy | 13 (43.3) |

Efficacy

Tumor response

The response rates were evaluated in the 20 patients

with residual disease prior to immunotherapy. During the

immunotherapy period, the best ORR was observed to be 65% (95% CI,

40.8–84.6%), including 6 instances of a CR and 7 of a PR. The best

DCR was observed to be 100.0%, including 6 instances of a CR, 7 of

a PR and 7 of SD. At cycle 3 of dinutuximab beta immunotherapy, the

ORR was 25% (95% CI, 8.6–49.1%), DCR was 95% (95% CI, 75.1–99.9%)

and the CR rate was 15% (95% CI, 3.2–37.9%), while at cycle 5 or 6,

the ORR was 40% (95% CI, 19.1–63.9%), the DCR was 100.0% and the CR

rate was 20% (95% CI, 5.7–43.7%). At the end of dinutuximab beta

immunotherapy, the ORR was 55% (95% CI, 31.5–76.9%), the DCR was

90% (95% CI, 68.3–98.8%) and the CR rate was 30% (95% CI,

11.9–54.3%). It showed that ORR improved by 15% from 40% at the end

of cycle 5 or 6 to 55% at the end of the extended cycles of

dinutuximab beta immunotherapy; moreover, the CR rate improved by

10% from 20% at the end of cycle 5 or 6 to 30% at the end of

extended immunotherapy. The detailed data are presented in Table III.

| Table III.Responses at cycles 3 and 5/6, and at

the end of dinutuximab beta immunotherapy in 20 patients with

residual active disease. |

Table III.

Responses at cycles 3 and 5/6, and at

the end of dinutuximab beta immunotherapy in 20 patients with

residual active disease.

| Category | After cycle 3 | After cycle

5/6 | After the end of

immunotherapy | Best response |

|---|

| CR, n (%) | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 6 (30) | 6 (30) |

| PR, n (%) | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | 5 (25) | 7 (35) |

| MR, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| SD, n (%) | 14 (70) | 12 (60) | 7 (35) | 7 (35) |

| PD, n (%) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) |

| ORR, % | 25 | 40 | 55 | 65 |

| DCR, % | 95 | 100 | 90 | 100 |

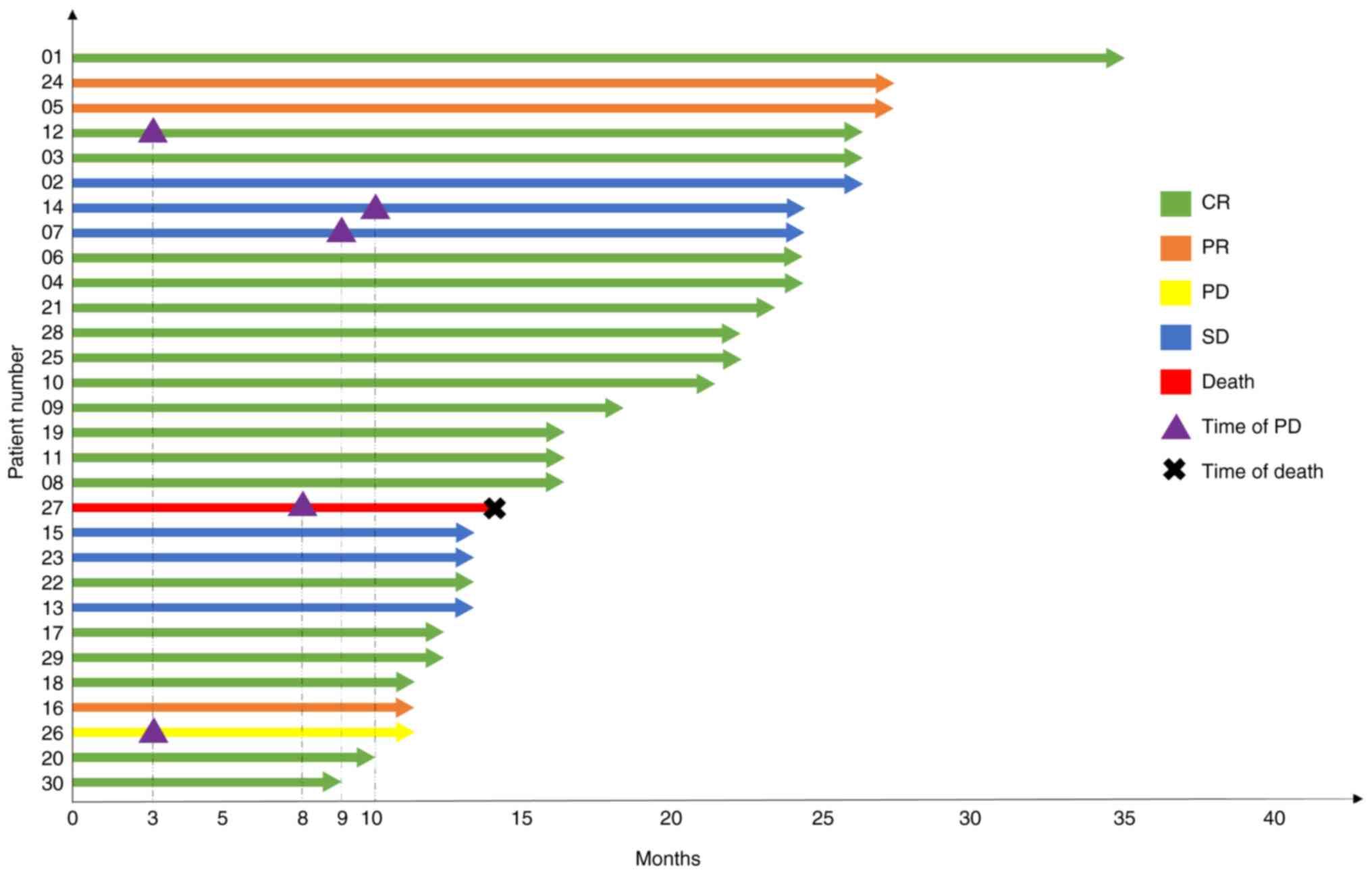

Notably, 13 patients showed the best tumor response,

5 patients achieved the best response after >5 cycles of

dinutuximab beta treatment, including 2 patients with SD at the end

of cycle 5 who improved to CR after cycles beyond the standard 5,

and 3 patients who converted from SD to PR, implying 38.5% (5/13

patients) showed improvement from cycles beyond the standard 5 of

immunotherapy. Additionally, among the 10 patients without residual

disease prior to immunotherapy, the CR maintenance rate was 90%

(95% CI, 55.5–99.7%) after cycles beyond the standard 5, with 9

patients achieving a CR and 1 experiencing PD. The disease status

of individual patients is illustrated in Fig. 2, and the detailed individual

response is presented in Table

SI.

Tumor response in a subgroup of

patients

At the end of extended dinutuximab beta

immunotherapy, among the 6 patients with relapsed NB, the ORR was

33.3% (2/6 patients) and the DCR was 66% (4/6 patients). Among

these 6 patients, 1 achieved a CR, 1 achieved a PR, 2 reported SD

and 2 experienced PD. Among the 24 patients with refractory NB, the

ORR was 75% (18/24 patients) and the DCR was 95.8% (23/24

patients), including 14 patients who achieved a CR, 4 who achieved

a PR, 5 who reported SD and 1 who had developed PD. Numerically,

patients with refractory disease achieved a better tumor response

compared with those with relapsed disease.

Among the 12 patients with only bone metastasis

prior to the initiation of dinutuximab beta therapy, the ORR was

58.3% (7/12 patients) and DCR was 91.7% (11/12 patients). At the

end of dinutuximab beta treatment, 4 patients achieved a CR, 3

achieved a PR, 4 noted SD and 1 experienced PD. For 1 patient with

isolated BM metastasis, a SD state remained throughout the

treatment period. Notably, it was found that a CR was achieved at

the last follow-up examination after treatment cessation. It was

speculated that this was due to a delayed effect associated with

dinutuximab beta immunotherapy.

Additionally, 2 patients had concurrent active

lesions in both bone and BM. Of them, 1 patient who initially

experienced SD achieved a CR subsequently, whereas the other

patient experienced PD. Among the 4 patients with concurrent active

soft-tissue and bone metastases, 2 achieved a CR, 1 achieved a PR

and 1 experienced SD, with an ORR of 75% (3/4 patients) and a DCR

of 100.0% (4/4 patients).

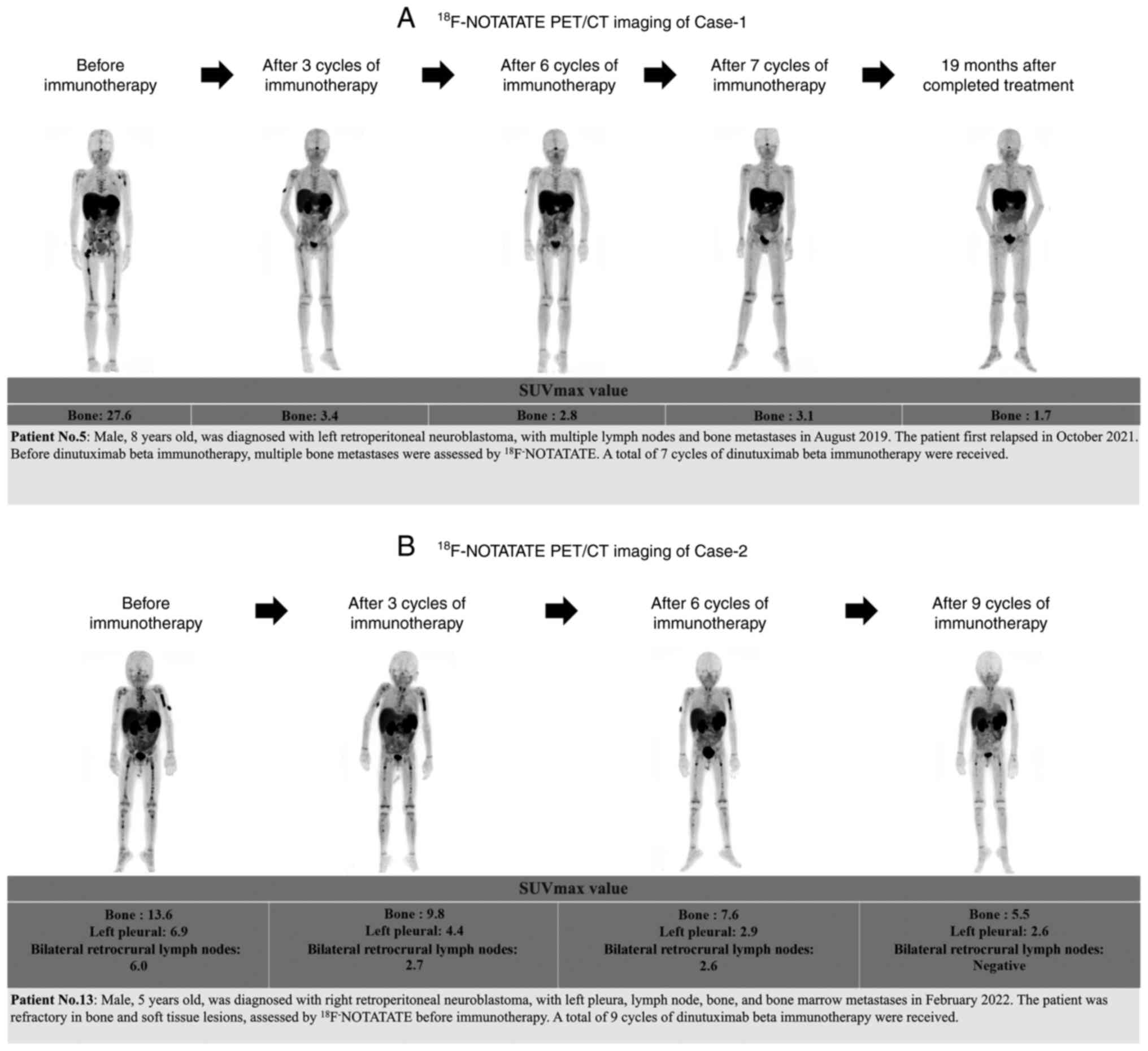

The tumor status at the center was assessed using

18F-NOTATATE-PET/CT imaging prior to dinutuximab beta

therapy, after 3 cycles, after 5/6 cycles and at the end of the

extended treatment cycles. A gradual decrease in tumor activity was

observed with the extension of dinutuximab beta treatment cycles.

Two typical cases and corresponding imaging data, which include

bone or pleura/lymph node metastasis, are presented for reference

in Fig. 3.

Furthermore, among the 23 patients who received a

stem cell transplantation, 13 patients achieved a CR, 4 achieved a

PR, 5 exhibited SD and 1 patient developed PD. The ORR and DCR were

73.9% (17/23 patients) and 95.7% (22/23 patients), respectively.

Among the 7 patients who did not receive a stem cell

transplantation, 2 patients achieved a CR, 1 achieved a PR, 2

exhibited SD and 2 developed PD. The ORR was 42.9% (3/7 patients)

and the DCR was 71.4% (5/7 patients). It appears that patients who

received a stem cell transplantation exhibited a more favorable

tumor response compared with those non-transplanted patients.

Of the 4 patients with PD who received

chemoimmunotherapy, 2 patients achieved a CR, 1 achieved a PR and 1

exhibited SD, with an ORR of 75% (3/4 patients) and a DCR of 100.0%

(4/4 patients), suggesting the beneficial effects of

chemoimmunotherapy for patients with PD. Furthermore, 2 patients

developed PD after receiving 3 cycles of dinutuximab beta

immunotherapy and they continued with co-therapy with a

chemotherapy regimen. One of these patients was assessed as

exhibiting SD after 6 cycles of dinutuximab beta treatment and

subsequently achieved a PR after receiving 10 cycles. However, the

other patient still had active disease after 6 cycles of

dinutuximab beta. Continuing with chemoimmunotherapy may be a

beneficial treatment option for patients with PD.

Survival analysis

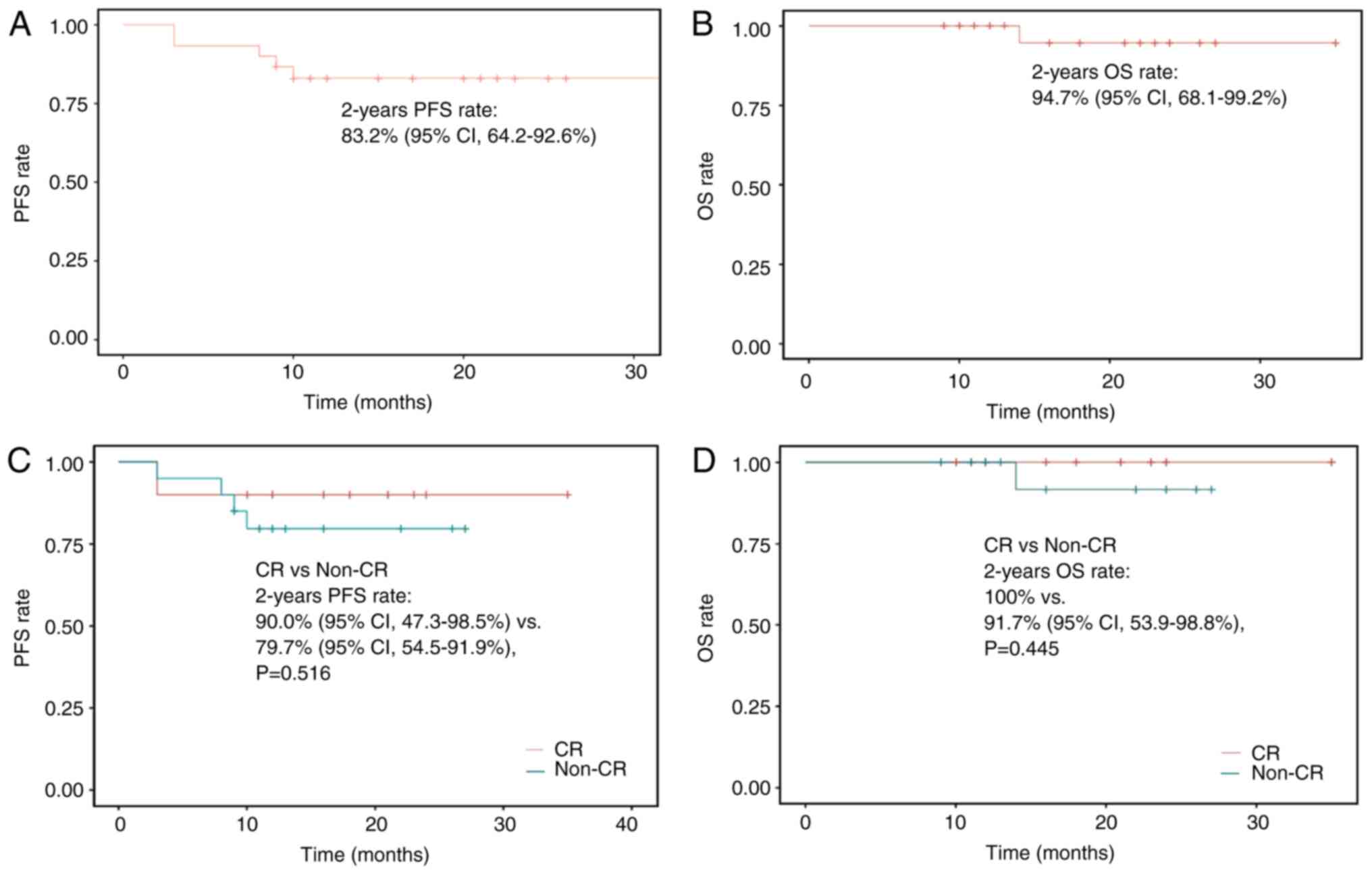

The 2-year PFS rate was 83.2% (95% CI, 64.2–92.6%)

and the 2-year OS rate was 94.7% (95% CI, 68.1–99.2%) for the

overall population (Fig. 4A and B).

Although not statistically significant, the 2-year PFS rate

[(90.0%; 95% CI, 47.3–98.5%) vs. (79.7%; 95% CI, 54.5–91.9%);

P=0.516] and the 2-year OS rate [(100.0%) vs. 91.7% (95% CI,

53.9–98.8%); P=0.445] were numerically higher in patients who

achieved a CR compared with those values in patients who did not

achieve a CR prior to dinutuximab beta immunotherapy (Fig. 4C and D).

The prognostic impact of clinical variables on PFS

was further assessed. The model included tumor status prior to

antibody therapy (CR vs. non-CR), disease type (refractory vs.

relapsed) and history of autologous stem cell transplantation. MYCN

amplification was excluded due to the absence of progression events

in this subgroup. The analysis identified disease type as a

significant predictor, with refractory NB associated with a reduced

risk of progression (hazard ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.02–0.92;

P=0.04). Other variables did not reach statistical significance,

likely due to the limited sample size and number of events.

Detailed results are presented in Fig.

S1.

Safety

During the standard 5 cycles of treatment, the most

common grade ≥3 TRAEs were infections (n=26; 86.7%), neutropenia

(n=25; 83.3%), leukopenia (n=17; 56.7%) and pain (n=16; 53.3%).

These TRAEs persisted into the extended immunotherapy phase, with

higher incidence rates compared with the standard cycles

[infections, n=27 (90%); neutropenia, n=26 (86.7%); leukopenia,

n=19 (63.3%) and pain, n=16 (53.3%)]. Nonetheless, these events

were clinically manageable and did not result in treatment

discontinuation. Moreover, no long-term toxicities were observed

during the follow-up period. Detailed TRAEs are presented in

Table IV.

| Table IV.Evaluation of treatment-related

adverse events (n=30). |

Table IV.

Evaluation of treatment-related

adverse events (n=30).

|

| Period during the

standard 5 cycles | Period during the

extended immunotherapy cycles |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Adverse events | Grade 3, n (%) | Grade 4–5, n

(%) | Total, n (%) | Grade 3, n (%) | Grade 4–5, n

(%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|

| Anemia | 15 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (50.0) | 15 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (50.0) |

| Leukopenia | 16 (53.3) | 1 (3.3) | 17 (56.7) | 16 (53.3) | 3 (10.0) | 19 (63.3) |

| Neutropenia | 24 (80.0) | 1 (3.3) | 25 (83.3) | 24 (80.0) | 2 (6.7) | 26 (86.7) |

|

Thrombocytopenia | 10 (33.3) | 3 (10.0) | 13 (43.3) | 10 (33.3) | 6 (20.0) | 16 (53.3) |

| Elevated serum

transaminase levels | 6 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (20.0) | 7 (23.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (23.3) |

| Infection | 26 (86.7) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (86.7) | 27 (90.0) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (90.0) |

| Pain | 16 (53.3) | / | 16 (53.3) | 16 (53.3) | / | 16 (53.3) |

| Fever | 9 (30.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (30.0) | 9 (30.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (30.0) |

| Capillary leak

syndrome | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) |

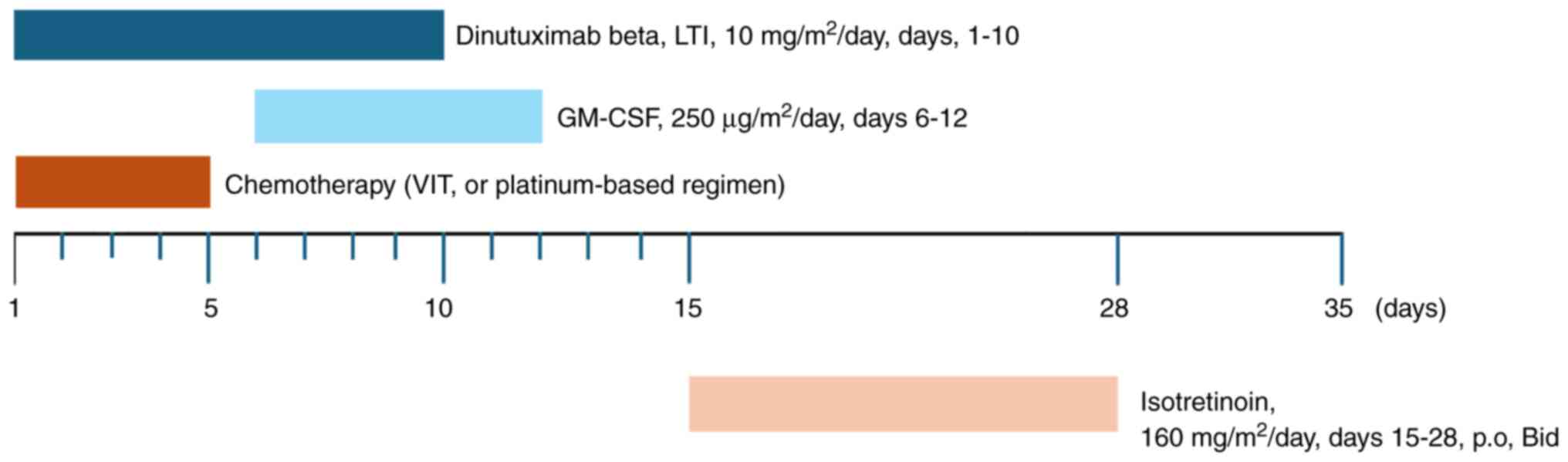

Notably, the use of morphine decreased from cycle 3,

showing reduced immune-related pain (Fig. 5). Furthermore, no immune-related

deaths were observed.

Discussion

The present study findings suggest that cycles

beyond the standard 5 cycles of dinutuximab beta treatment combined

with chemotherapy improve tumor responses and survival in patients

with R/R NB. A subset of patients achieved optimal responses after

undergoing extended dinutuximab beta treatment cycles, contributing

to favorable outcomes.

Anti-GD2 immunotherapy has shown promise for HR-NB.

Dinutuximab beta, dosed at 10 mg/m2/day for a fixed 5

cycles is recommended according to the Summary of Product

Characteristics (7,18). Given the poor prognosis of R/R cases

and limited effective options, extending therapy beyond 5 cycles

may be a viable strategy. In a retrospective study from Poland and

Germany, 31% of patients showed best responses after >5 cycles,

with treatment extended up to 10 cycles (12). A Turkish study similarly reported

treatment up to 14 cycles with positive outcomes (19). Consistent with these findings, the

present study showed that 38.5% of patients benefited from extended

treatment, with up to 12 cycles administered. Late responses were

observed post-cycle 5, suggesting that residual disease may still

respond to prolonged therapy. The low toxicity profile of

dinutuximab beta supports the feasibility of extended use.

The combination of anti-GD2 antibodies with

chemotherapy has enhanced efficacy in relapsed/progressive HR-NB,

as demonstrated in randomized trials BEACON-Immuno and ANBL1221

(9,20). Preclinical studies also reported up

to 17-fold increased cytotoxicity when dinutuximab beta was

combined with chemotherapy, attributed mainly to enhanced

antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (21). The current study employed both

platinum-based and temozolomide-based regimens. Despite no

stratified analysis by regimen, dinutuximab beta showed consistent

activity across all combinations. Supporting this, the SACHA-France

study (clinical trial no. NCT04477681) reported comparable ORRs of

40–42% across different chemotherapy backbones, namely topotecan +

cyclophosphamide, temozolomide + topotecan, and temozolomide +

irinotecan when combined with dinutuximab beta, suggesting that the

choice of chemotherapy may not significantly influence efficacy

(22). These findings further

support the notion that the choice of chemotherapeutic drugs may

not significantly impact the overall efficacy of dinutuximab

beta-based chemoimmunotherapy.

Dinutuximab beta was generally well tolerated in the

present study, with a similar profile of grade ≥3 TRAEs as observed

in the SIOPEN trials (23,24). The TRAE profile of

chemoimmunotherapy in the present study, which was consistent with

previous findings, indicates that the majority of TRAEs are

hematological toxicities (12,25),

and that they are considered to be predominantly induced by

chemotherapy. Pain is one of the most common AEs associated with

anti-GD2 antibodies (26) and was

well managed in the present study. Additionally, no severe

neurological disturbances were observed. In the present study, a

higher incidence of AEs was observed during the extended

immunotherapy cycles compared with that in the standard 5-cycle

treatment period. Notable increases were seen with regard to

leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, transaminase elevations

and infections. Despite the increased frequency, these events were

clinically manageable with standard supportive measures, and no

long-term or irreversible toxicities were documented. These

findings support the feasibility and tolerability of extended

chemoimmunotherapy in patients with HR-NB when administered under

appropriate clinical oversight.

Although a multivariate analysis was performed to

explore potential prognostic factors for PFS, its interpretability

is constrained by the limited number of progression events and the

modest cohort size. As such, the analysis should be viewed as

exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. To

maintain scientific transparency, the findings have been provided

as supplementary material. Ongoing follow-up and event accumulation

will be critical to support more robust multivariable modeling and

to validate potential prognostic indicators in this population.

Several limitations of the present study should be

acknowledged. The study was a retrospective, single-center and

non-randomized study, which introduces the potential for selection

bias that may limit the generalizability of the findings to a

broader population. The single-center nature of the study also

restricts the diversity of the sample, potentially limiting the

applicability of the results to other healthcare settings. The

absence of a well-defined control group, such as patients receiving

only the standard 5-cycle regimen, restricts the ability of the

study to definitively assess the incremental benefit of extended

treatment. As such, the observations should be interpreted with

caution.

In conclusion, cycles beyond the standard 5 cycles

of dinutuximab beta treatment in combination with chemotherapy

demonstrated feasibility, tolerability and potential clinical

benefit in patients with R/R NB. A subset of patients achieved

meaningful responses following extended treatment, supporting the

rationale for prolonged anti-GD2-based chemoimmunotherapy. However,

the retrospective, single-center design and absence of a control

arm limit the strength of causal inferences regarding treatment

efficacy. To substantiate these findings and determine optimal

treatment duration, future prospective, multi-center randomized

trials are essential.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Collaborative Academic

Innovation Project of Shandong Cancer Hospital (grant no.

FC005).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ZG was responsible for organizing, validating, and

maintaining data to ensure its accuracy, consistency, and usability

for analysis, statistical analysis, writing the original draft, and

reviewing and editing the manuscript. SK performed study

conceptualization, assisted with the methodology, and reviewed and

edited the manuscript. CB performed the statistical analysis and

helped to write the original draft. YL and XY performed data

curation, validation, statistical analysis, and manuscript review

and editing. KS and YS performed investigation, literature

research, study conception, and manuscript review and editing. FC

performed study supervision, study conception, and manuscript

review and editing. JW was responsible for conceptualization,

methodology, supervision, writing the original draft, and reviewing

and editing. JW and ZG confirm the authenticity of all raw data.

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Academy of Medical

Sciences (Jinan, China; approval no. SDTHEC202503192). The

requirement for informed consent was exempted due to the

retrospective nature of the data acquisition.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kholodenko IV, Kalinovsky DV, Doronin II,

Deyev SM and Kholodenko RV: Neuroblastoma origin and therapeutic

targets for immunotherapy. J Immunol Res. 2018:3942682018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Park JR, Eggert A and Caron H:

Neuroblastoma: Biology, prognosis, and treatment. Hematol Oncol

Clin North Am. 24:65–86. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Nong J, Su C, Li C, Wang C, Li W, Li Y,

Chen P, Li Y, Li Z, She X, et al: Global, regional, and national

epidemiology of childhood neuroblastoma (1990–2021): A statistical

analysis of incidence, mortality, and DALYs. EClinicalMedicine.

79:1029642025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Smith V and Foster J: High-risk

neuroblastoma treatment review. Children (Basel).

5:1142018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Su Y, Qin H, Chen C, Wang S, Zhang S,

Zhang D, Jin M, Peng Y, He L, Wang X, et al: Treatment and outcomes

of 1041 pediatric patients with neuroblastoma who received

multidisciplinary care in China. Pediatr Investig. 4:157–167. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

London WB, Castel V, Monclair T, Ambros

PF, Pearson AD, Cohn SL, Berthold F, Nakagawara A, Ladenstein RL,

Iehara T and Matthay KK: Clinical and biologic features predictive

of survival after relapse of neuroblastoma: A report from the

international neuroblastoma risk group project. J Clin Oncol.

29:3286–3292. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

National Medical Products Administration,

. Information on the pending collection of drug approval documents

released on August 16, 2021. https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/zwfw/sdxx/sdxxyp/yppjfb/20210816154622110.htmlMay

5–2025

|

|

8

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, . Neuroblastoma. Version

2.2024. https://www.nccn.org/login?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/neuroblastoma.pdfMay

5–2025

|

|

9

|

Gray J, Moreno L, Weston R, Barone G,

Rubio A, Makin G, Vaidya S and Wheatley W: BEACON-Immuno: Results

of the dinutuximab beta (dB) randomization of the

BEACON-Neuroblastoma phase 2 trial-A european innovative therapies

for children with cancer (ITCC-International Society of Paediatric

Oncology Europe Neuroblastoma Group (SIOPEN) trial. J Clin Oncol.

40:10002. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Mody R, Yu AL, Naranjo A, Zhang FF, London

WB, Shulkin BL, Parisi MT, Servaes SE, Diccianni MB, Hank JA, et

al: Irinotecan, temozolomide, and dinutuximab with GM-CSF in

children with refractory or relapsed neuroblastoma: A report from

the Children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 38:2160–2169. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Olgun N, Arayici ME, Kızmazoglu D and

Cecen RE: Assessment of Chemo-immunotherapy regimens in patients

with refractory or relapsed neuroblastoma: A systematic review with

Meta-analysis of critical oncological outcomes. J Clin Med.

14:9342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wieczorek A, Zaniewska-Tekieli A, Ehlert

K, Pawinska-Wasikowska K, Balwierz W and Lode H: Dinutuximab beta

combined with chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory

neuroblastoma. Front Oncol. 13:10827712023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Monclair T, Brodeur GM, Ambros PF, Brisse

HJ, Cecchetto G, Holmes K, Kaneko M, London WB, Matthay KK,

Nuchtern JG, et al: The international neuroblastoma risk group

(INRG) staging system: An INRG task force report. J Clin Oncol.

27:298–303. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Park JR, Bagatell R, Cohn SL, Pearson AD,

Villablanca JG, Berthold F, Burchill S, Boubaker A, McHugh K,

Nuchtern JG, et al: Revisions to the international neuroblastoma

response criteria: A consensus statement from the national cancer

institute clinical trials planning meeting. J Clin Oncol.

35:2580–2587. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pauwels E, Cleeren F, Tshibangu T, Koole

M, Serdons K, Dekervel J, Van Cutsem E, Verslype C, Van Laere K,

Bormans G and Deroose CM: [18F]AlF-NOTA-octreotide PET imaging:

biodistribution, dosimetry and first comparison with

[68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE in neuroendocrine tumour patients. Eur J Nucl Med

Mol Imaging. 47:3033–3046. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hou J, Long T, He Z, Zhou M, Yang N, Chen

D, Zeng S and Hu S: Evaluation of 18F-AlF-NOTA-octreotide for

imaging neuroendocrine neoplasms: Comparison with 68Ga-DOTATATE

PET/CT. EJNMMI Res. 11:552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE)

Version 5.0. https://dctd.cancer.gov/research/ctep-trials/for-sites/adverse-events/ctcae-v5-5×7.pdfOctober

15–2025

|

|

18

|

European Medicines Agency, . Qarziba

epar-product information. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/qarziba-epar-product-information_en.pdfOctober

15–2025

|

|

19

|

Olgun N, Cecen E, Ince D, Kizmazoglu D,

Baysal B, Onal A, Ozdogan O, Guleryuz H, Cetingoz R, Demiral A, et

al: Dinutuximab beta plus conventional chemotherapy for

relapsed/refractory high-risk neuroblastoma: A single-center

experience. Front Oncol. 12:10414432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mody R, Naranjo A, Van Ryn C, Yu AL,

London WB, Shulkin BL, Parisi MT, Servaes SE, Diccianni MB, Sondel

PM, et al: Irinotecan-temozolomide with temsirolimus or dinutuximab

in children with refractory or relapsed neuroblastoma (COG

ANBL1221): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol.

18:946–957. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Troschke-Meurer S, Zumpe M, Meißner L,

Siebert N, Grabarczyk P, Forkel H, Maletzki C, Bekeschus S and Lode

HN: Chemotherapeutics used for High-risk neuroblastoma therapy

improve the efficacy of Anti-GD2 antibody dinutuximab beta in

preclinical spheroid models. Cancers (Basel). 15:9042023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Raiser P, Schleiermacher G, Gambart M,

Dumont B, Defachelles AS, Thebaud E, Tandonnet J, Pasqualini C,

Proust S, Entz-Werle N, et al: Chemo-immunotherapy with dinutuximab

beta in patients with relapsed/progressive high-risk neuroblastoma:

Does chemotherapy backbone matter? Eur J Cancer. 202:1140012024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ladenstein R, Pötschger U, Valteau-Couanet

D, Luksch R, Castel V, Yaniv I, Laureys G, Brock P, Michon JM,

Owens C, et al: Interleukin 2 with anti-GD2 antibody ch14.18/CHO

(dinutuximab beta) in patients with high-risk neuroblastoma

(HR-NBL1/SIOPEN): A multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 19:1617–1629. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ladenstein RL, Poetschger U,

Valteau-Couanet D, Gray J, Luksch R, Balwierz W, Castel V and Lode

HN: Randomization of dose-reduced subcutaneous interleukin-2

(scIL2) in maintenance immunotherapy (IT) with anti-GD2

antibody dinutuximab beta (DB) long-term infusion (LTI) in

front-line high-risk neuroblastoma patients: Early results from the

HR-NBL1/SIOPEN trial. J Clin Oncol. 37:10013. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Lode HN, Ladenstein R, Troschke-Meurer S,

Struppe L, Siebert N, Zumpe M, Ehlert K, Huber S, Glogova E,

Hundsdoerfer P, et al: Effect and tolerance of N5 and N6

chemotherapy cycles in combination with dinutuximab beta in

relapsed High-risk neuroblastoma patients who failed at least one

second-line therapy. Cancers (Basel). 15:33642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Barone G, Barry A, Bautista F, Brichard B,

Defachelles AS, Herd F, Manzitti C, Reinhardt D, Rubio PM,

Wieczorek A and van Noesel MM: Managing adverse events associated

with dinutuximab beta treatment in patients with High-risk

neuroblastoma: Practical guidance. Pediatr Drugs. 23:537–548. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|