Introduction

According to the latest cancer statistics from the

International Agency for Research on Cancer, 434,419 new cases and

155,702 deaths from renal cancer were reported in 2022 (1). Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) includes

histological subtypes such as clear cell RCC (ccRCC), papillary

RCC, and chromophobe RCC (2). Among

these, ccRCC represents the highest proportion, accounting for

70–75% of all RCCs (2). Compared

with non-ccRCC, ccRCC is associated with higher mortality and lower

survival rates, indicating the poorest prognosis among RCCs

(2,3). Furthermore, ccRCC originates from

proximal tubule epithelial cells and typically exhibits an

expansive growth pattern (4).

Histologically, it is marked by abundant clear cytoplasm resulting

from lipid and glycogen accumulation (2). The Fuhrman grade (5) and the WHO/ISUP grading system

(6) are generally used to grade the

nuclear features of ccRCC. Higher nuclear grades correlate with

poorer prognosis; therefore, these nuclear grading systems have

been used in clinical practice. However, recent studies have

indicated that the Fuhrman grade has moderate interobserver

agreement (7). Because of

subjectivity in how pathologists emphasize specific criteria and

assess nuclear size, it has been suggested that grading beyond

Grade 4 should primarily focus on nucleolar evaluation (7,8).

Dagher et al (8) suggested

that the WHO/ISUP grading system correlates more strongly with

patient survival than the Fuhrman grade.

Changes in nuclear morphology are reported to be

influenced by changes in the expression of nuclear envelope

(NE)-associated proteins, including Lamin, Emerin, SUN, and Nesprin

(9). In particular, Lamins are

classified into two types: A-type and B-type Lamin (10). Lamin A, which is on the

nucleoplasmic side, forms a dense meshwork (10). Lamin B1, which is situated between

Lamin A and the inner nuclear membrane (INM), forms a relatively

loose meshwork (10). Lamin B1

prevents nuclear bleb formation caused by Lamin A protrusions

(10). Lamin influences nuclear and

cellular morphologies. Vahabikashi et al (11) reported that Lamin A deficiency leads

to nuclear distortion and increased nuclear volume, whereas Lamin

B1 or B2 deficiency causes no evident distortion. In Lamin

B1-deficient cells, nuclear volume is smaller than in wild-type

cells, whereas in Lamin B2 deficiency, it is nearly identical to

wild-type. Furthermore, Lamin interacts with the Linker of

Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) complex and intermediate

filaments, thereby regulating cytoplasmic stiffness (11). The effects of Lamin also vary by

tumor type. Moss et al (12)

reported that in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, Lamin A/C is

reduced while Lamin B1 is retained, whereas in colon tumors and

gastric dysplasia, both Lamin A/C and B1 are decreased. Conversely,

pancreatic cancer retains the expression of both Lamin proteins

(12). Although reduced Lamin

expression is common in cancer, it is not observed in all

epithelial tumors (12). Previous

studies have also reported findings related to Emerin (13,14).

Vaughan et al (14) reported

that Lamin A, C, and B1 interact with Emerin; when Lamin A/C is

absent from the NE, Emerin relocates from the NE to the endoplasmic

reticulum. Hence, Lamin A is necessary to anchor Emerin to the NE.

Lammerding et al (13)

reported that Emerin deficiency induces abnormalities in the

nuclear shape; however, these are milder than those caused by Lamin

A deficiency, and nuclear rigidity remains comparable to that of

wild type. Furthermore, SUN and Nesprin interact with both Lamin

and Emerin as well as the cytoskeleton, thereby influencing both

the nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton (15,16).

Haque et al reported that the C-terminals of SUN1 and SUN2

interact with the KASH domains of Nesprin-1 and −2, linking the

nucleus to actin, whereas their N-terminals interact with nuclear

Lamin, Emerin, and short Nesprin-2 isoforms. These interactions

bridge the nucleoskeleton and the cytoskeleton, playing a crucial

role in maintaining nuclear and cellular integrity (15). Banerjee et al (17) reported that deficiency of either

Nesprin-1 or Nesprin-2 increases nuclear area and perimeter and

reduces roundness; when both are deficient, the localization of

Lamin A/C and Emerin is disrupted. Ketema et al (16) demonstrated that Nesprin-3, similar

to Nesprin-1 and −2, localizes to the outer nuclear membrane

through interactions with SUN1 and SUN2. Furthermore, Nesprin-3α

binds to plectin dimers, linking intermediate filaments to the

nucleus, whereas the interaction between SUN and Lamin A forms the

Nesprin-3-LINC complex that bridges the cytoskeleton and

nucleoskeleton (16). Heffler et

al (18) also reported that

Nesprin-3 deficiency increases the number of nuclear wrinkles and

indentations.

Several studies have reported the contribution of

altered expression levels of Lamin, Emerin, SUN, and Nesprin to

nuclear and cellular morphologies. Therefore, examining the

expression of these NE-associated proteins may help identify

potential indicators of nuclear grade. Regarding kidney cancer, Xin

et al reported that reduced Lamin A expression contributes

to abnormal nuclear morphology (19). Radspieler et al (20) also reported that the gene expression

levels of Lamin B1 serve as a marker of poor prognosis.

Furthermore, Fukushima et al (21) demonstrated that reduced Nesprin-1

gene expression is a poor prognostic factor and that its knockdown

enhances invasive potential. However, to our knowledge, no studies

have directly compared nuclear grade with the expression of

NE-associated proteins to elucidate the mechanisms underlying

nuclear morphological changes in ccRCC. Therefore, we conducted

this study to investigate the relationship between nuclear grade

and nine NE-associated proteins: Lamin A, Lamin B1, Lamin B2,

Emerin, SUN1, SUN2, Nesprin-1, Nesprin-2, and Nesprin-3, which have

been implicated in alterations of nuclear and cellular

morphology.

Materials and methods

Samples

This study included 199 patients who underwent

surgical resection for ccRCC at Gunma University Hospital between

January 2005 and July 2012. The Gunma University Ethical Review

Board for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects approved this

study (approval no. HS2024-068). We used formalin-fixed and

paraffin-embedded tissue blocks used for routine pathological

diagnosis. Sections were cut at 4 µm thickness for

immunohistochemical staining.

Evaluation of nuclear grade

Hematoxylin-eosin-stained diagnostic specimens,

stored in the Department of Pathology at Gunma University Hospital,

were reviewed by pathologists. The nuclear grades of four patient

groups (G1-G4) were determined according to the Fuhrman grade

(5) and WHO/ISUP grading systems

(6).

Immunohistochemical staining

Four micrometer-thick sections were deparaffinized

through three 5-min xylene treatments. For rehydration, sections

were sequentially immersed in 100, 99, 95, and 70% ethanol for 1

min each, followed by a 1-min rinse under running water. For

immunohistochemical staining, the following antibodies were used at

a concentration of 2 µg/ml: anti-Lamin A antibody (clone 133A2;

mouse monoclonal antibody; ab8980; Abcam), anti-Lamin B1 antibody

(clone 3C10G12; mouse monoclonal antibody; 66095-1-Ig; Proteintech,

Rosemont, USA), anti-Lamin B2 antibody (clone GT144; mouse

monoclonal antibody; GTX628803; GeneTex, California, USA),

anti-Emerin antibody (clone CL0201; mouse monoclonal antibody;

NBP2-52876; Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA), anti-SUN1

antibody (clone EPR6554; rabbit monoclonal antibody; ab124770;

Abcam), anti-SUN2 antibody (clone EPR6557; rabbit monoclonal

antibody; ab124916; Abcam), anti-Nesprin-1 antibody (clone

EPR14196; rabbit monoclonal antibody; ab192234; Abcam),

anti-Nesprin-2 antibody (clone EPR28137-54; rabbit monoclonal

antibody; ab186746; Abcam), and anti-Nesprin-3 antibody (clone

EPR15623; rabbit monoclonal antibody; ab314872; Abcam). First,

sections were placed in an electric pot containing Immunosaver

(Nisshin EM Co. Ltd., Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan) diluted 200-fold

with distilled water for antigen retrieval. Next, they were boiled,

maintained at 98°C for 40 min, and left in the pot for 30 min after

turning off the heat. Subsequently, they were transferred to a

container with 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution.

Following antigen retrieval, immunohistochemical staining was

performed using an automated staining system (Histostainer 36A;

Nichirei Biosciences, Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Japan). We treated the

specimens with hydrogen peroxide solution (code 715242; Nichirei

Bioscience) for 5 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity.

After the specimens were washed with PBS (code 715224; Nichirei

Bioscience), 2% goat serum (ab7481; Abcam) was added and incubated

for 15 min. Primary antibodies (clones 133A2, 3C10G12, GT144,

CL0201, EPR6554, EPR6557, EPR14196, EPR28137-54, and EPR15623) were

applied and incubated at room temperature for 60 min. After

washing, peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG polyclonal antibody

(Histofine Simple Stain MAX-PO(M); code 724132; Nichirei

Bioscience) was applied as the secondary antibody for 30 min to

specimens treated with primary antibodies, including clones 133A2,

3C10G12, GT144, and CL0201. For clones EPR6554, EPR6557, EPR14196,

EPR28137-54, and EPR15623, peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit IgG

polyclonal antibody (Histofine Simple Stain MAX-PO(R); code 724142;

Nichirei Bioscience) was used as the secondary antibody for 30 min.

For color development, the specimens were incubated with the DAB

substrate kit (code 725191; Nichirei Bioscience) twice for 10 min.

After washing, the nucleus was stained with hematoxylin (code

715081; Nichirei Bioscience) for 1 min. Subsequently, the specimens

were removed from the automatic staining machine and washed once

with distilled water. Next, sections were dehydrated in 70, 95, and

100% ethanol (two baths) for 1 min each. For clearing, xylene was

applied in three consecutive baths for 5 min, followed by mounting.

Subsequently, the sections were examined using an optical

microscope (BX51; Evident, Tokyo, Japan) to confirm staining.

Acquisition of specimen images using a

virtual slide scanner

Whole-slide images of immunohistochemically stained

specimens for Lamin A, B1, and B2 were obtained using a virtual

slide scanner (Nano Zoomer 2.0-HT Virtual Slide Scanner; C9600-13;

Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Shizuoka, Japan). The scanning conditions

were as follows: observation lens, 20×; resolution, 0.75; scan

mode, 40×; maximum capture size, 26×76 mm; pixel size, 0.23

µm/pixel; light source, halogen lamp; and image storage format,

JPEG.

Computer-assisted image analysis

For analyzing Lamin A-, B1-, and B2-stained

specimens, five representative regions per specimen were selected

at 40× magnification from whole-slide images and saved as TIFF

files. The images were then analyzed using the NE measurement

software e-Nucmen3 (ver. 1.8; E-path Co. Ltd, Fujisawa, Kanagawa,

Japan). To focus on tumor cell nuclei, nontumor regions were

excluded using the annotation function. Nuclei of nontumor cells

within the tumor region, overlapping nuclei, and nuclei not

correctly recognized by the software were also excluded. Analysis

conditions are provided in Table

SI.

Evaluation of Emerin, SUN, and Nesprin

expression

Specimens stained with each primary antibody were

examined under a microscope. To evaluate expression changes,

staining intensity in the tumor region was compared with that of

the nuclear membrane in normal proximal tubules from the same

patient. Expression levels of Emerin, SUN1, SUN2, and Nesprin-2

were classified into three categories: decreased, no change, and

increased. For Nesprin-1, the expression level was classified into

decreased, no change, and nucleoplasm. For Nesprin-3, because no

expression was detected in the NE of normal proximal tubules,

expression was classified as no change (absent) or increased

(present).

Statistical analysis

All statistical data were analyzed using JMP Pro

ver. 18. 2.0 (SAS Japan, Tokyo, Japan). For multiple comparisons

involving unequal group sample sizes (unbalanced data), one-way

ANOVA was initially performed to check variance among groups, after

which, the Tukey-Kramer HSD test was used for pair-wise

comparisons, referencing Lee and Lee (22) for its validity. Because part of the

statistical evaluation involved qualitative assessment, Fisher's

exact test was used for 2×2 group comparisons to examine the

presence or absence of distribution differences (23). Comparisons involving more than two

groups were analyzed using the Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact

conditional test (24). Association

between two continuous variables were assessed using linear

regression analysis. Association strength was classified according

to the correlation coefficient (r) as follows: 0.200–0.399,

weak; 0.400–0.699, moderate; and ≥0.700, strong. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference

(25).

Results

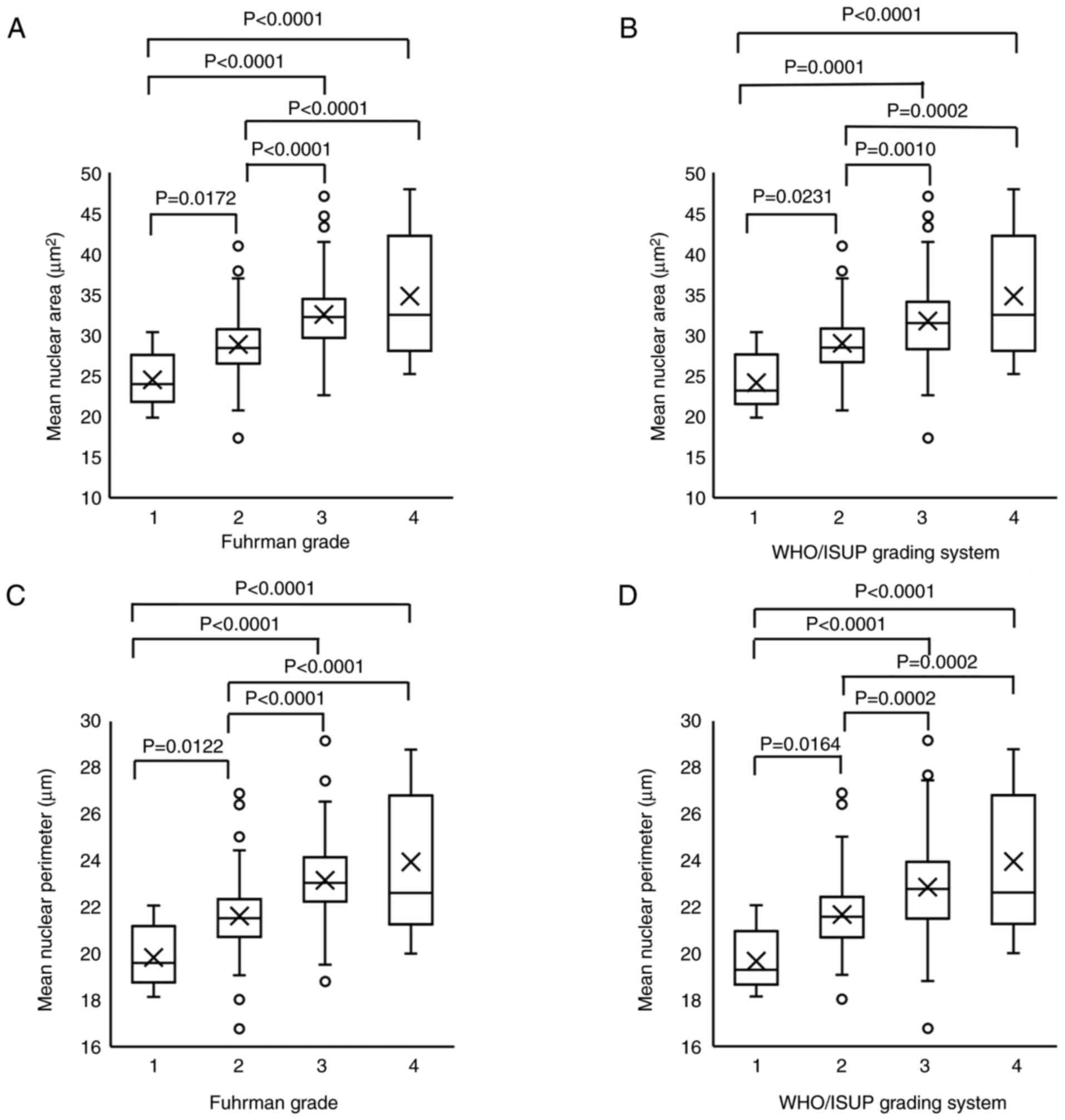

Nuclear size increased from G1 to

G3

Table I summarizes

the clinicopathological characteristics of the patients (26). First, the mean nuclear area and

perimeter were compared with Fuhrman and WHO/ISUP grades. G1-G3

showed a significant increase in mean nuclear area and perimeter

across both grading systems. However, neither grading system showed

a significant difference between G3 and G4 (Fig. 1A-D). Therefore, nuclear size may not

adequately represent G4, and other factors likely contribute to

nuclear and cellular morphology in this grade. The representative

G1 to G4 grade histological images of HE staining for both Fuhrman

and WHO/ISUP grades are shown in Fig.

S1.

| Table I.Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients. |

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Total number of

patients, n (%) | 199 (100) |

| Mean age,

years | 63.0 |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

Male | 142 (71) |

|

Female | 57 (29) |

| Fuhrman grade, n

(%) |

|

| 1 | 10 (5) |

| 2 | 117 (59) |

| 3 | 59 (30) |

| 4 | 13 (6) |

| WHO/ISUP grading

system, n (%) |

|

| 1 | 8 (4) |

| 2 | 109 (55) |

| 3 | 69 (35) |

| 4 | 13 (6) |

| pT status, n

(%) |

|

|

pT1 | 169 (85) |

|

pT2 | 10 (5) |

|

pT3 | 19 (10) |

|

pT4 | 1 (0.5) |

| pN status, n

(%) |

|

|

pN0 | 196 (85) |

|

pN1 | 3 (15) |

| pM status, n

(%) |

|

|

pM0 | 194 (97) |

|

pM1 | 5 (3) |

| Stage, n (%) |

|

| I | 165 (83) |

| II | 10 (5) |

|

III | 16 (8) |

| IV | 8 (4) |

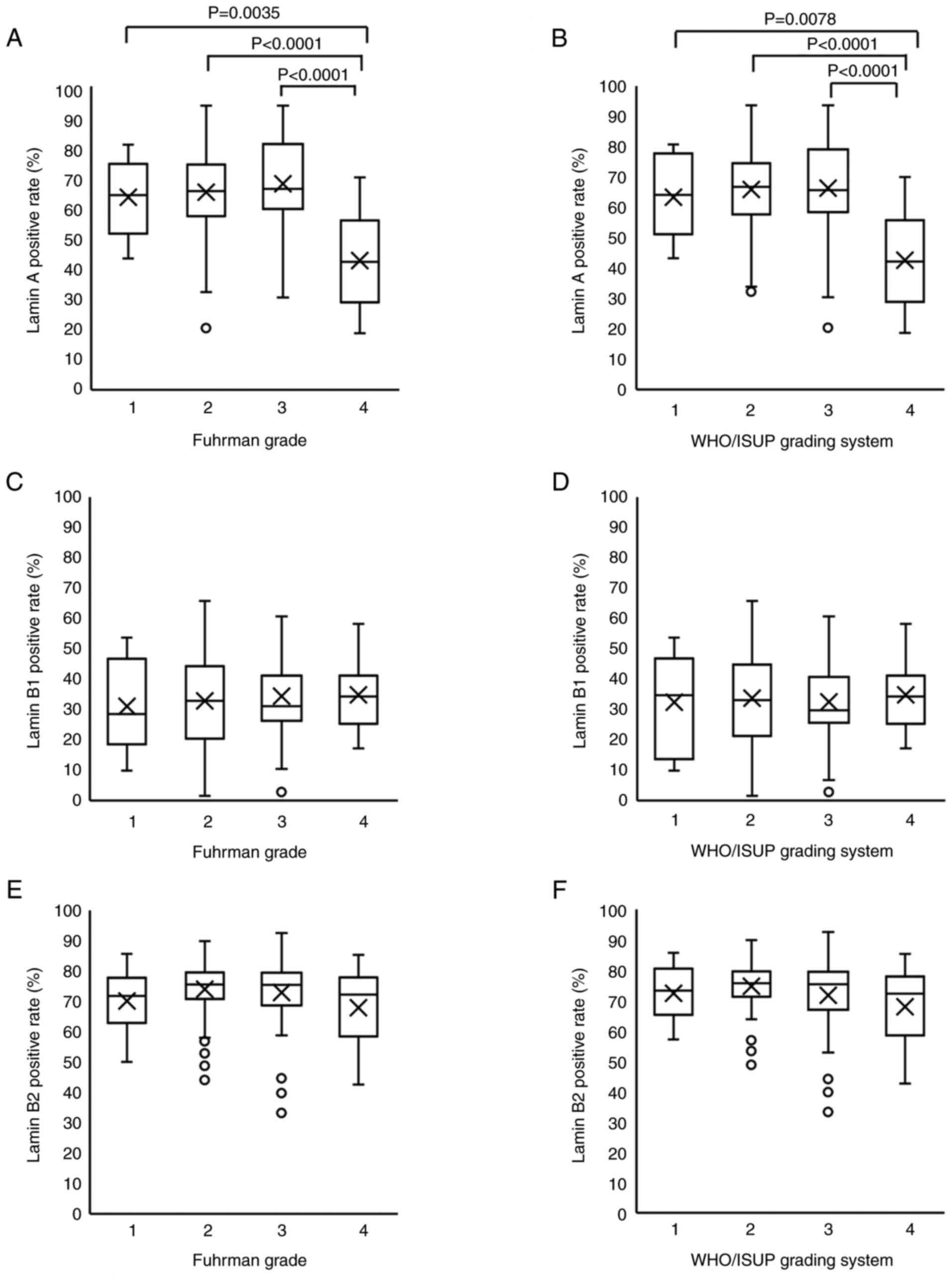

Decreased Lamin A expression

influences nuclear shape changes in G4

Next, we examined the positive rates for Lamin A,

B1, and B2 according to the two grading systems. Mean Lamin A

positive rates by grade were 63.4, 65.2, 68, and 42.6% for G1, G2,

G3, and G4 in the Fuhrman grade and 63.4, 65.9, 66.3, and 42.6% in

the WHO/ISUP grading system, respectively. Thus, the Lamin A

positive rate was significantly lower in G4 than in G1-G3 in both

grading systems (Fig. 2A and B).

Meanwhile, the mean Lamin B1 positive rates were 31.1, 32.8, 34.4,

and 34.9% for G1, G2, G3, and G4 cases in Fuhrman grade and 32.4,

33.7, 32.5, and 34.9% in the WHO/ISUP grading system, respectively.

For Lamin B2, mean positive rates by grade were 70.1, 74, 73, and

67.9% for G1, G2, G3, and G4 in the Fuhrman grade and 72.3, 74.7,

71.7, and 67.9% in the WHO/ISUP grading system, respectively.

Positive rates of Lamin B1 or B2 did not differ significantly

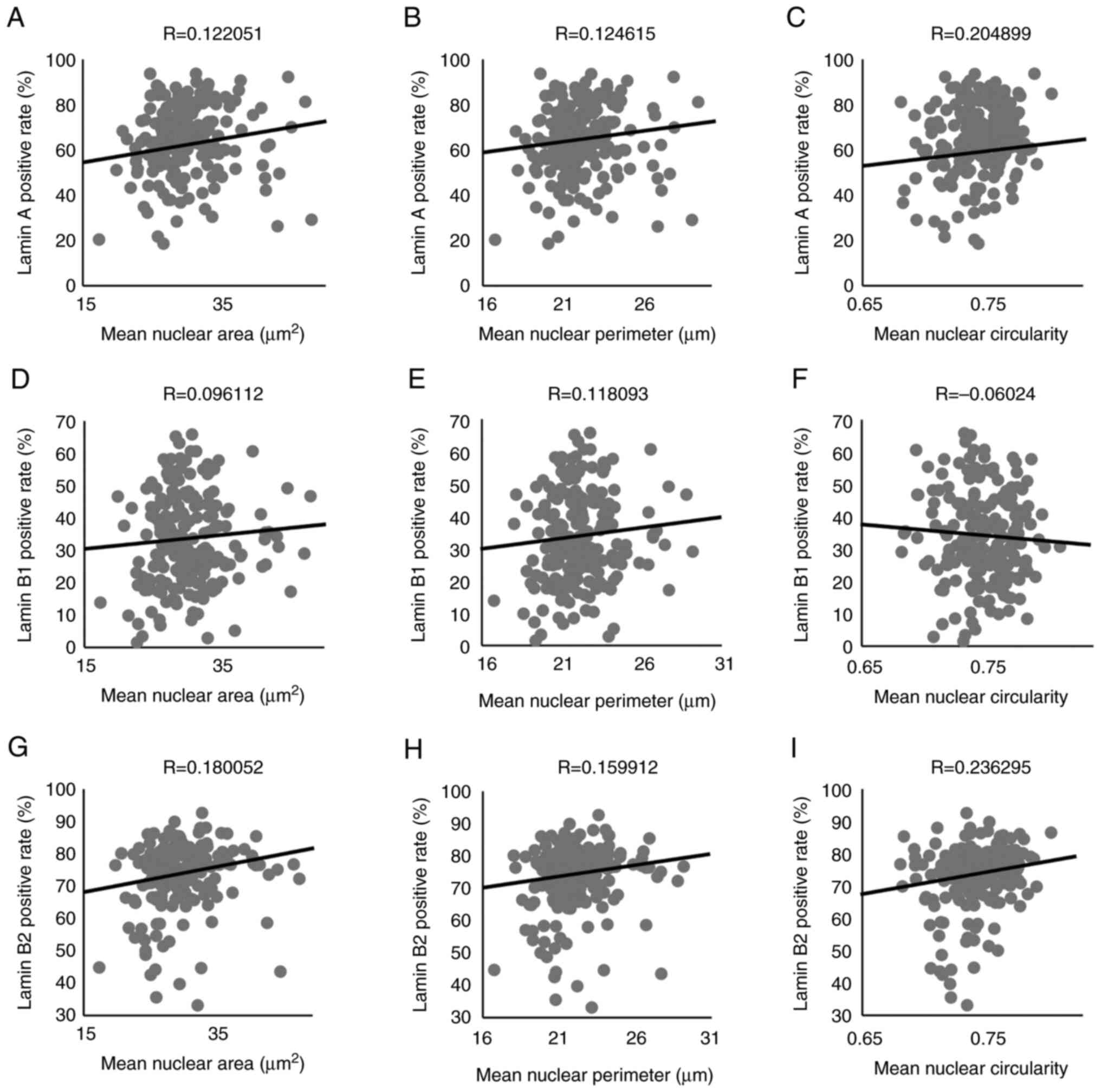

between groups in either grading systems (Fig. 2C-F). We compared the positive rates

for each Lamin with the mean nuclear area, perimeter, and

circularity. The positive rate for Lamin A showed no association

with mean nuclear area or perimeter (Fig. 3A and B) but exhibited a weak

association with mean circularity (Fig.

3C). Furthermore, the positive rate for Lamin B1 did not

associate with any of the nuclear shape indicators (Fig. 3D-F). The positive rate of Lamin B2

was not associated with the mean nuclear area or mean nuclear

perimeter (Fig. 3G and H) but

weakly associated with the mean circularity (Fig. 3I). Therefore, only Lamin A exhibited

a significant decrease in expression in G4 cases. Furthermore,

Lamin A and B2 were weakly associated with the maintenance of

nuclear shape across all grades. The representative images of Lamin

A, B1 and B2 based on the WHO/ISUP grading system was shown in

Fig. S2.

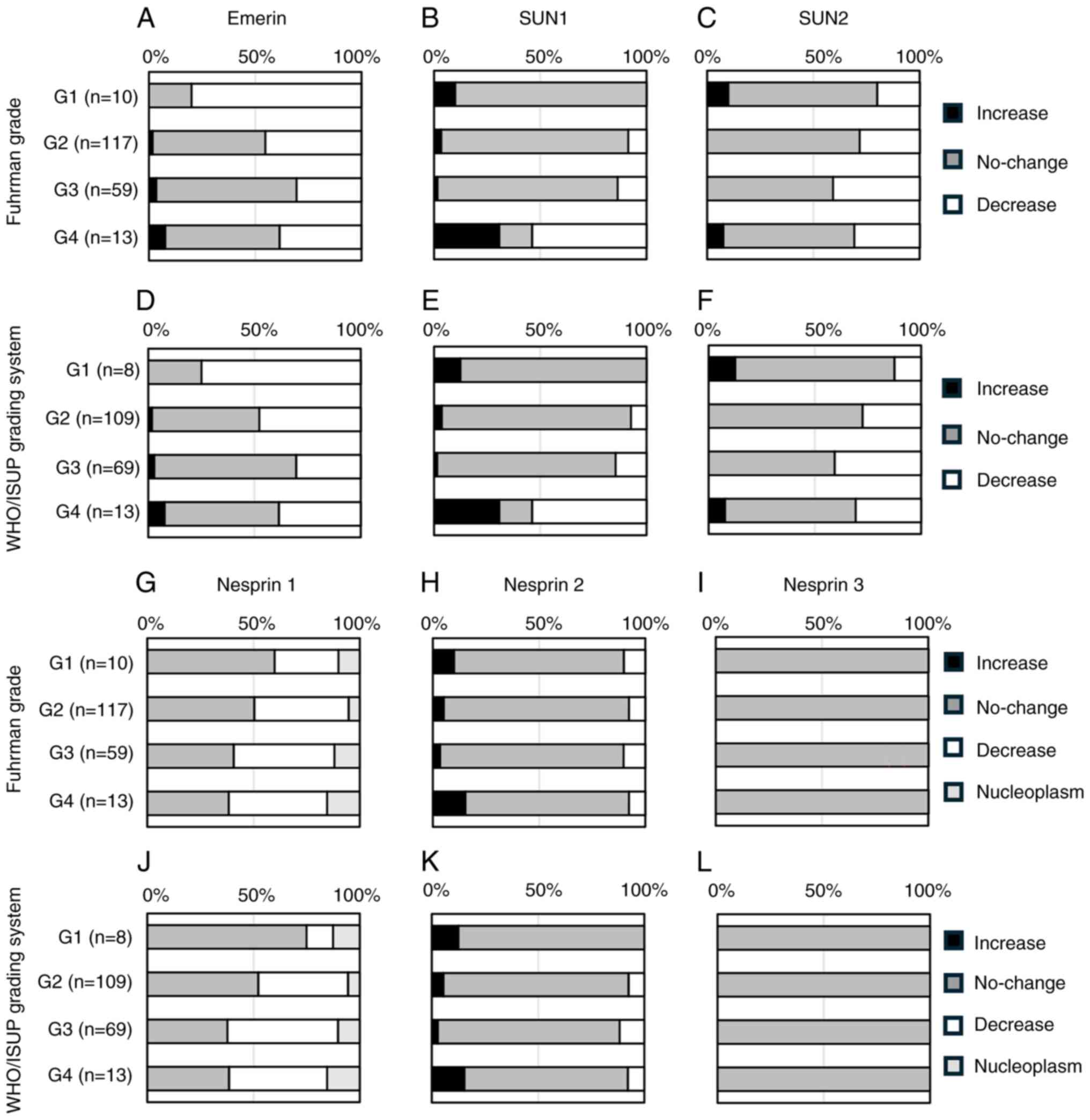

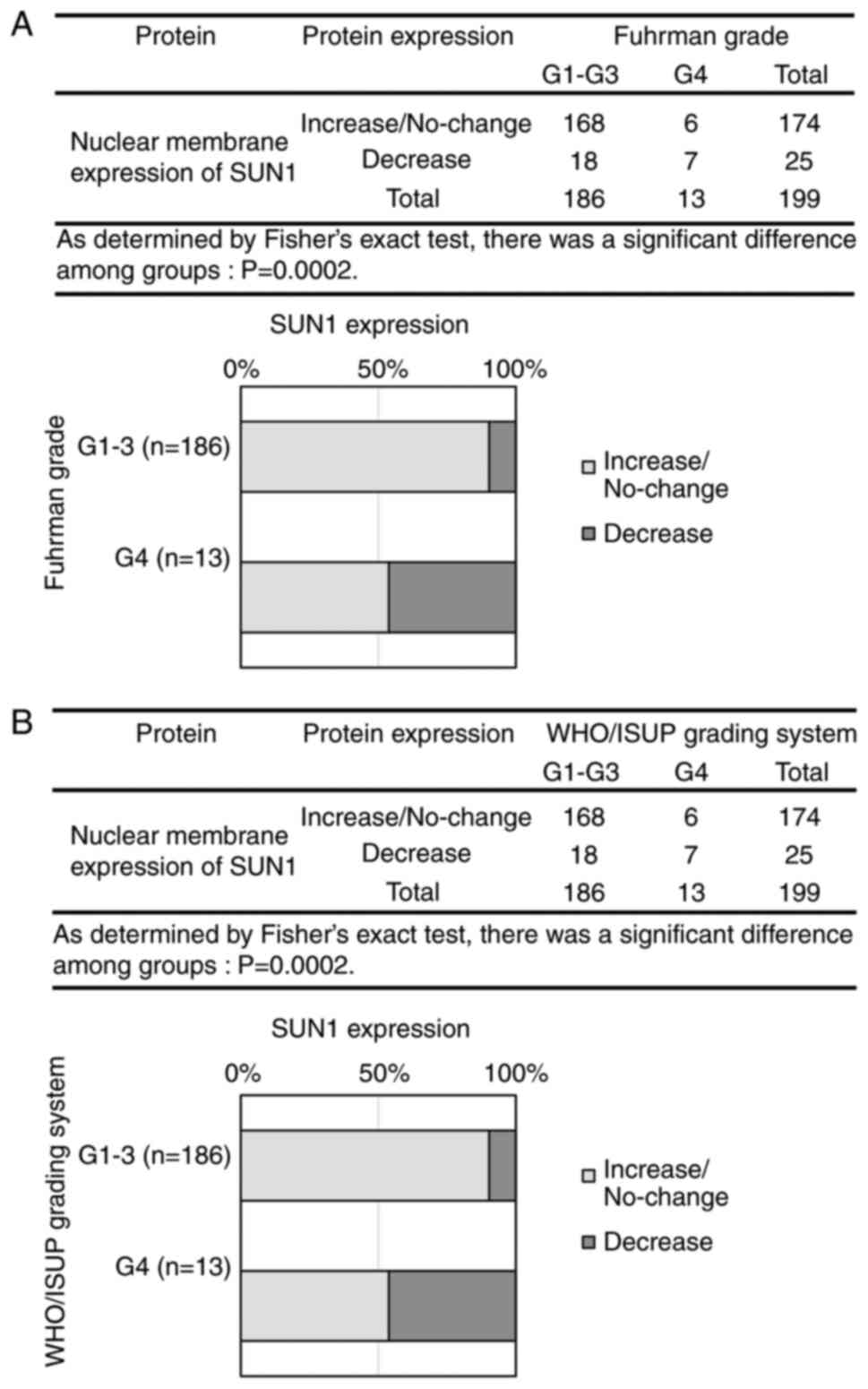

SUN1 reduction in G4 cases correlates

with nuclear grade

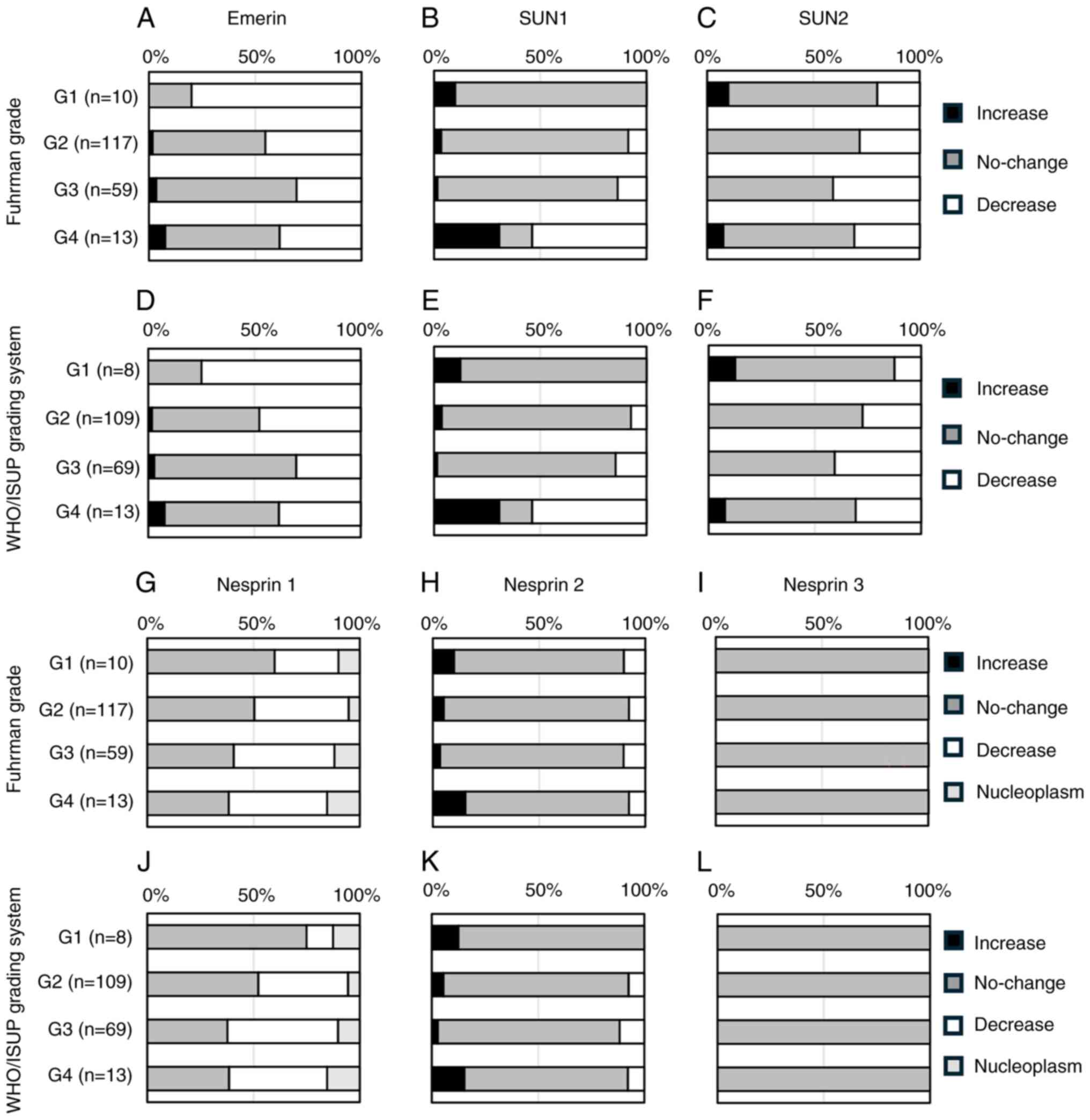

In addition to Lamin, we examined the association of

expression changes in Emerin, SUN, and Nesprin with nuclear grade

(Fig. 4A-L). In the

Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact conditional test, Emerin showed a

significant difference between groups in the Fuhrman grade

(P=0.0488) but not in the WHO/ISUP grading system (P=0.0690)

(Fig. 4A and D). For SUN1,

significant differences were observed between groups in both

nuclear grading systems (P<0.0001) (Fig. 4B and E). Similarly, SUN2 showed

significant between-group differences in the Fuhrman grade

(P=0.0289) and the WHO/ISUP grading system (P=0.0143) (Fig. 4C and F). In contrast, Nesprin-1 and

Nesprin-2 showed no significant changes between groups in either

grading system (Fig. 4G, H, J and

K). In all 199 cases, Nesprin-3 expression was negative in the

nuclear membranes of normal proximal tubules and that of tumor

cells (Fig. 4I and L). SUN1, which

demonstrated the most significant changes, showed reduced

expression was increased in G4 cases; in other grades, expression

either increased or remained unchanged. Therefore, a Fisher's exact

test was performed by dividing the cases into two groups: no

change/increased vs. decreased, and G1-G3 vs. G4. The results

revealed a significant reduction in SUN1 expression in G4 cases

(Fig. 5A and B), suggesting that

SUN1 reduction correlates with the progression of nuclear atypia to

G4. Regarding the significant differences detected in Emerin and

SUN2 expression by the Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact conditional

test, the difference among groups would be exist. The

representative image of SUN1 based on the WHO/ISUP grading system

is shown in Fig. S3.

| Figure 4.Comparison of nuclear

envelope-associated protein expression and nuclear grade. (A)

Emerin expression vs. Fuhrman grade, (B) SUN1 expression vs.

Fuhrman grade, (C) SUN2 expression vs. Fuhrman grade. (D) Emerin

expression vs. WHO/ISUP grading system, (E) SUN1 expression vs.

WHO/ISUP grading system, (F) SUN2 expression vs. WHO/ISUP grading

system. (G) Nesprin1 expression vs. Fuhrman grade, (H) Nesprin2

expression vs. Fuhrman grade, (I) Nesprin3 expression vs. Fuhrman

grade. (J) Nesprin1 expression vs. WHO/ISUP grading system, (K)

Nesprin2 expression vs. WHO/ISUP grading system, (L) Nesprin3

expression vs. WHO/ISUP grading system. WHO, World Health

Organization; ISUP, International Society of Urologic

Pathologists. |

Discussion

In the WHO/ISUP grading system, G1-G3 are determined

solely by nucleolar size, without reference to nuclear size or

shape. In contrast, G4 is based on nuclear and cellular

morphological changes, including marked nuclear atypia,

multinucleated giant cells, sarcomatoid features, and rhabdoid

changes (6). Because nuclear grade

correlates with prognosis (8),

investigating its underlying mechanisms is essential. Accordingly,

in this study, we compared the expression of NE-associated proteins

with nuclear grade. To our knowledge, no studies have compared

nuclear grade with NE-associated protein expression to elucidate

the mechanism of nuclear morphological changes in ccRCC.

Capo-chichi et al (27)

reported that many cells in cervical smear specimens negative for

Lamin A/C contained enlarged, irregularly shaped nuclei.

Furthermore, Xin et al (19)

reported that knockdown of the LMNA gene encoding Lamin A in

kidney cancer cell lines resulted in NE invaginations and

abnormalities in nuclear contours. Therefore, we first investigated

Lamin's contribution to nuclear grade, followed by an examination

of the mechanisms underlying nuclear morphological changes in

ccRCC. We found that Lamin A expression levels were reduced in G4

cases, whereas those of Lamin B1 and B2 showed no significant

changes. Lammerding et al reported that in mouse embryonic

fibroblasts, reduced Lamin A decreased nuclear stiffness, whereas

Lamin B1 or B2 had no effect (28).

Furthermore, although Lamin B1 reduction increased nuclear bleb

formation, it did not alter overall nuclear rigidity or shape

stability (28). In a study by

Pujadas Liwag et al (29)

using human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines, reduced B-type

Laminincreased nuclear volume and nuclear bleb formation. Based on

these findings, B-type Lamin contributes to nuclear bleb formation,

but its effect on overall nuclear morphology is less pronounced

than that of Lamin A. Harborth et al (30) reported that silencing Lamin B1 and

B2 in HeLa cells and rat fibroblasts induced growth arrest and

apoptosis. These findings suggest that Lamin A is involved in

maintaining nuclear morphology and Lamin B1 and Lamin B2 are

involved in other functions, including cell proliferation. This

interpretation does not appear to contradict the results of the

present study.

Reis-Sobreiro et al (31) reported that Emerin deficiency leads

to irregular nuclear shapes, reduced roundness, and impaired

deformability in prostate and breast cancer cell lines.

Furthermore, Lamin A/C downregulation contributes to nuclear shape

instability and destabilization such as Emerin mislocalization

(31). Based on this report,

considering that Emerin may influence nuclear morphology, we

investigated its effect on nuclear pleomorphism classification. In

G4 nuclei, cellular morphological changes such as sarcomatoid and

rhabdoid features are also considered indicators (6). NE-associated proteins such as SUN and

Nesprin interact to form the LINC complex (32). Lombardi et al (33) reported that LINC complex disruption

causes defects in nuclear positioning, cytoskeletal organization,

and cell/nuclear deformation. The mechanisms underlying both

nuclear and cellular morphological changes were investigated by

examining the relationship between changes in SUN and Nesprin

expression and nuclear grade. In this study, SUN1 expression

decreased in G4 cases, similar to Lamin A. Emerin and SUN2 also

showed significant intergroup differences. Although the proportion

of G1 cases with reduced Emerin expression was higher than in other

grades, the difference was statistically significant only in the

Fuhrman grade, not in the WHO/ISUP classification. Therefore, the

small number of G1 cases may have influenced the observed

significance. For SUN2, between-group differences were significant

in the Fuhrman grade and the WHO/ISUP grading system, although they

looked unclear in Fig. 4E and F.

Thus, despite the possibility of differences in Emerin and SUN2

among groups, describing a specific association between nuclear

grade and protein expression changes in ccRCC was difficult in this

study. For Nesprin-1, Nesprin-2, or Nesprin-3, the changes were not

significant in relation to nuclear grade. Matsumoto et al

(34) reported that in breast

cancer specimens, Lamin A, SUN1, SUN2, and Nesprin-2 expression was

downregulated in cancerous areas compared with that in noncancerous

ones. Accordingly, their findings for SUN2 and Nesprin-2 do not

align with our results, possibly caused by organ-specific

differences. Ueda et al (35) reported that SUN1 deficiency in HeLa

cells, with no actin reduction observed in SUN2-deficient cells led

to reduced actin, decreased cytoskeletal force, and diminished

contractile force, whereas SUN2 deficiency had no effect on actin,

indicating a specific role for SUN1 in cytoskeletal regulation

(35). Therefore, SUN1 deficiency

may contribute to reduced tumor differentiation. The observed

reduction of SUN1 expression in G4 cases in our study is consistent

with the findings of Ueda et al (35). In our study, SUN1 was reduced only

in G4 cases, similar to Lamin A; thus, Lamin A may be related to

SUN1. Östlund et al (36)

demonstrated that Lamin A is more closely associated with SUN1 than

with SUN2. Haque et al (37)

reported that although SUN1 interacts with Lamin A, it localizes to

the NE even in the absence of Lamin A, indicating that Lamin A is

not required for the NE localization of SUN1. Nishioka et al

(38) reported that SUN1 interacts

with Lamin B1 and B2, whereas SUN2 shows no interaction with B-type

Lamin. Therefore, SUN1 may be associated with Lamin A, B1, and B2.

However, the present results suggest that only Lamin A is

associated with SUN1 in ccRCC. Sharma et al (39) reported that SUN1/2 knockdown in rat

mammary carcinoma cell lines caused irregular nuclear morphology.

As Lamin expression and localization remained unchanged, the

nuclear defects of SUN1/2 were not attributable to off-target

effects on Lamin. In our study, both Lamin A and SUN1 expression

were reduced in G4 cases. These findings suggest that Lamin A and

SUN1 are interrelated or independently contribute to nuclear

morphological alterations. Considering that Nesprin-1 was expressed

in the nucleoplasm, we examined the basis for this localization

pattern. Mislow et al (40)

reported that Nesprin-1α can bind both Lamin and Emerin, acting as

a structural cross-linker that anchors these proteins to the INM.

Duong et al (41) reported

that Nesprin-1α-1 was undetectable at very low levels in all

tissues, whereas Nesprin-1α and −2 were highly expressed

exclusively in cardiac and skeletal muscles. The proportions of the

Nesprin isoforms Nesprin-2-Giant and Nesprin-1-Giant in the kidney

were 81 and 15%, respectively (41). Furthermore, in cells lacking the

KASH domain of Nesprin-2, this protein exhibited a speckled pattern

within the nucleoplasm (41).

Therefore, the nucleoplasmic staining of Nesprin-1 observed in this

study may reflect the absence of the KASH domain, considering the

very low levels of Nesprin-1α in the kidney. Moreover, Sur-Erdem

et al (42) reported that

Nesprin-1 overexpression restored abnormalities in tumor cell

nuclear structure, NE organization, centrosome positioning, and

genomic instability. Nesprin-1 interacts with Lamin and SUN

proteins, contributing to the maintenance of nuclear structure and

cytoskeletal organization (42).

However, we found no significant correlation between Nesprin-1

expression changes and nuclear grade, suggesting that Nesprin-1

slightly influences ccRCC. Furthermore, Nesprin-3 was negative in

all cases, indicating that it was not associated with nuclear

grade. Wilhelmsen et al (43) showed that Nesprin-3 binds to

intermediate filaments via plectin. Morgan et al (44) reported that silencing Nesprin-3

induces cell elongation in human aortic endothelial cells. This was

accompanied by a marked reduction in the nuclear periphery

localization of plectin and the cytoskeletal protein vimentin,

highlighting the importance of Nesprin-3 in maintaining the

cytoskeletal structure of the nuclear periphery (44). However, our study showed that in the

kidney, Nesprin-3 expression was detected only in stromal

components, including mesangial cells and fibroblasts, but was

absent in the ccRCC regions derived from the proximal tubules,

similar to normal proximal tubules. Collectively, these findings

suggest that Nesprin-3 has no role in ccRCC.

Next, we discuss the rationale for using only

nuclear and cellular morphological characteristics to classify G4

in the WHO/ISUP grading system, whereas G1-G3 are defined primarily

by the nucleolar size. In this study, the mean nuclear area and

perimeter significantly increased with higher grades from G1 to G3

in both grading systems, whereas no significant differences were

observed between G3 and G4. Therefore, factors different from those

affecting G1-G3 may influence the transition to G4. In this study,

comparison of NE-associated proteins with nuclear grade revealed

that only Lamin A and SUN1 showed significantly reduced expression

in G4. Thus, decreased Lamin A and SUN1 expression may contribute

to nuclear and cellular morphological alterations associated with

progression to G4. Diegmiller et al (45) reported that the total nuclear volume

and total nucleolar volume in nurse cells exhibit a linear

proportional relationship. Therefore, observing nucleolar size can

be considered equivalent to observing nuclear size. In other words,

our finding that nuclear size increases with grade from G1 to G3

likely reflects proportional changes between nucleolar and nuclear

sizes. Conversely, our results indicate that G4 relies on nuclear

and cellular morphology as diagnostic indicators, as alterations in

NE-associated proteins such as Lamin A and SUN1 are observed only

at this stage.

Although this study did not evaluate prognostic or

therapeutic applications, we considered the potential diagnostic

and therapeutic implications of Lamin A and SUN1 based on previous

reports. Chiarini et al (46) reported that Lamin A functions as a

tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcoma, where its introduction reduces

invasive potential and high expression correlates with improved

5-year survival rates. Therefore, in ccRCC, reintroducing Lamin A

in patients with reduced tumor cell Lamin A expression may improve

survival outcomes. Regarding SUN, existing reports are primarily

related to SUN2. In lung cancer, SUN2 suppresses cell proliferation

and migration, and its overexpression enhances chemotherapy

sensitivity (47). In contrast, low

SUN2 expression is associated with shorter survival times (47). Although no studies have examined

treatment or survival outcomes related to SUN1, Nishioka et

al (38) reported that SUN1

promotes cell migration when overexpressed. Collectively, these

findings suggest that SUN2 upregulation and SUN1 inhibition may

have therapeutic potential. However, neither has been studied in

ccRCC, indicating that this topic warrants future

investigation.

Finally, this study has several limitations. First,

the numbers of G1 and G4 cases were small, each accounting for

approximately 5 and 6% of the 199 cases, respectively. Therefore, a

larger cohort and more detailed analyses are necessary. Second,

although Lamin expression was quantitatively evaluated through

image analysis, Emerin, SUN, and Nesprin expression relied on

manual evaluation, potentially limiting analytical precision. Some

proteins exhibited nucleoplasmic or cytoplasmic staining, resulting

in varied patterns that could not be measured using the e-Nucmen3

nuclear membrane analysis software. Therefore, future research

should focus on developing advanced analytical tools capable of

handling diverse staining patterns to enable automated image-based

quantification. Third, the study analyzed only human samples,

providing limited evidence that reduced the expression of Lamin A

or SUN1 directly causes changes in nuclear morphology. Therefore,

cell or animal models should be used in future research to verify

the underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, in ccRCC, alterations in

NE-associated protein expression were observed exclusively in G4

cases. Among Lamin, Emerin, SUN, and Nesprin proteins, only Lamin A

and SUN1 showed altered expression. Although the nuclear for G1-G3

is determined based on the nucleolar size, this parameter also

indirectly reflects nuclear size in image analysis. Notably, the

influence of NE-associated proteins appears confined to G4 tumors.

These findings provide important insight into why the WHO/ISUP

grading system exclusively employs nuclear and cellular

morphological features for G4 assessment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RS collected clinicopathological data, and

contributed to sectioning, immunohistochemistry, staining

evaluation, image and statistical analyses, and manuscript

preparation. MS planned and conducted the experiments, performed

histological diagnosis of carcinoma cases, and performed image

analysis, staining evaluation, statistical analysis and manuscript

preparation. SK performed immunohistochemistry, conducted image

analysis and reviewed the literature. YN performed whole-slide

imaging and reviewed the manuscript. MK and RK performed

whole-slide image data acquisition. MN and KS collected some

clinicopathological data from electrical records, graded and staged

some cases, and reviewed the clinicopathological data which RS

initially had collected, then corrected any incorrect data and

filled in missing data. The final clinicopathological data were

then verified by MN and KS to ensure the accuracy of the data. HI

and HY performed histological diagnosis of carcinoma cases. RS and

MS confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was conducted after obtaining approval

from Gunma University Ethical Review Board for Medical Research

Involving Human Subjects (approval no. HS2024-068). Informed

consent for this study was obtained by an opt-out method according

to the ‘Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research

Involving Human Subjects’ established by Ministry of Education,

Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and Ministry of Health,

Labour and Welfare in Japan. Because the FFPE samples were used

secondarily after their initial diagnostic purpose, we published a

notification about this study on the Gunma University Hospital

website instead of obtaining individual informed consent. The

notice provided an outline of the research plan, details of the

patient information to be used, the storage period and methods for

the samples, contact information, and assurance of the right to

freely withdraw from the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shuch B, Amin A, Armstrong AJ, Eble JN,

Ficarra V, Lopez-Beltran A, Martignoni G, Rini BI and Kutikov A:

Understanding pathologic variants of renal cell carcinoma:

Distilling therapeutic opportunities from biologic complexity. Eur

Urol. 67:85–97. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sepp T, Poyhonen A, Uusküla A, Kotsar A,

Veitonmäki T, Tammela TLJ, Baburin A and Murtola TJ: Renal cancer

survival in clear cell renal cancer compared to other types of

tumor histology: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One.

20:e03290002025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Muglia VF and Prando A: Renal cell

carcinoma: Histological classification and correlation with imaging

findings. Radiol Bras. 48:166–174. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Montironi R, Santinelli A, Pomante R,

Mazzucchelli R, Colanzi P, Filho AL and Scarpelli M: Morphometric

index of adult renal cell carcinoma. Comparison with the Fuhrman

grading system. Virchows Arch. 437:82–89. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Delahunt B, Srigley JR, Judge MJ, Amin MB,

Billis A, Camparo P, Evans AJ, Fleming S, Griffiths DF,

Lopez-Beltran A, et al: Data set for the reporting of carcinoma of

renal tubular origin: recommendations from the international

collaboration on cancer reporting (ICCR). Histopathology.

74:377–390. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lang H, Lindner V, de Fromont M, Molinié

V, Letourneux H, Meyer N, Martin M and Jacqmin D: Multicenter

determination of optimal interobserver agreement using the Fuhrman

grading system for renal cell carcinoma: Assessment of 241 patients

with > 15-year follow-up. Cancer. 103:625–629. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Dagher J, Delahunt B, Rioux-Leclercq N,

Egevad L, Srigley JR, Coughlin G, Dunglinson N, Gianduzzo T, Kua B,

Malone G, et al: Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Validation of

World Health Organization/International Society of Urological

Pathology grading. Histopathology. 71:918–925. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

de las Heras JI and Schirmer EC: The

nuclear envelope and cancer: A diagnostic perspective and

historical overview. Adv Exp Med Biol. 773:5–26. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nmezi B, Xu J, Fu R, Armiger TJ,

Rodriguez-Bey G, Powell JS, Ma H, Sullivan M, Tu Y, Chen NY, et al:

Concentric organization of A- and B-type lamins predicts their

distinct roles in the spatial organization and stability of the

nuclear lamina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:4307–4315. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Vahabikashi A, Sivagurunathan S, Nicdao

FAS, Han YL, Park CY, Kittisopikul M, Wong X, Tran JR, Gundersen

GG, Reddy KL, et al: Nuclear lamin isoforms differentially

contribute to LINC complex-dependent nucleocytoskeletal coupling

and whole-cell mechanics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

119:e21218161192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Moss SF, Krivosheyev V, de Souza A, Chin

K, Gaetz HP, Chaudhary N, Worman HJ and Holt PR: Decreased and

aberrant nuclear lamin expression in gastrointestinal tract

neoplasms. Gut. 45:723–729. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lammerding J, Hsiao J, Schulze PC, Kozlov

S, Stewart CL and Lee RT: Abnormal nuclear shape and impaired

mechanotransduction in emerin-deficient cells. J Cell Biol.

170:781–791. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Vaughan A, Alvarez-Reyes M, Bridger JM,

Broers JL, Ramaekers FC, Wehnert M, Morris GE, Whitfield WGF and

Hutchison CJ: Both emerin and lamin C depend on lamin A for

localization at the nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci. 114:2577–2590.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Haque F, Mazzeo D, Patel JT, Smallwood DT,

Ellis JA, Shanahan CM and Shackleton S: Mammalian SUN protein

interaction networks at the inner nuclear membrane and their role

in laminopathy disease processes. J Biol Chem. 285:3487–3498. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ketema M, Wilhelmsen K, Kuikman I, Janssen

H, Hodzic D and Sonnenberg A: Requirements for the localization of

nesprin-3 at the nuclear envelope and its interaction with plectin.

J Cell Sci. 120:3384–3394. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Banerjee I, Zhang J, Moore-Morris T,

Pfeiffer E, Buchholz KS, Liu A, Ouyang K, Stroud MJ, Gerace L,

Evans SM, et al: Targeted ablation of nesprin 1 and nesprin 2 from

murine myocardium results in cardiomyopathy, altered nuclear

morphology and inhibition of the biomechanical gene response. PLoS

Genet. 10:e10041142014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Heffler J, Shah PP, Robison P, Phyo S,

Veliz K, Uchida K, Bogush A, Rhoades J, Jain R and Prosser BL: A

balance between intermediate filaments and microtubules maintains

nuclear architecture in the cardiomyocyte. Circ Res. 126:e10–e26.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xin H, Tang Y, Jin YH, Li HL, Tian Y, Yu

C, Zhao ZJ, Wu MS and Pan YF: Knockdown of LMNA inhibits

Akt/β-catenin-mediated cell invasion and migration in clear cell

renal cell carcinoma cells. Cell Adh Migr. 17:1–14. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Radspieler MM, Schindeldecker M, Stenzel

P, Forsch S, Tagscherer KE, Herpel E, Hohenfellner M, Hatiboglu G,

Roth W and Macher-Goeppinger S: Lamin-B1 is a senescence-associated

biomarker in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett.

18:2654–2660. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fukushima T, Kobatake K, Miura K, Takemoto

K, Yamanaka R, Tasaka R, Kohada Y, Miyamoto S, Sekino Y, Kitano H,

et al: Nesprin1 deficiency is associated with poor prognosis of

renal cell carcinoma and resistance to sunitinib treatment.

Oncology. 102:868–879. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lee S and Lee DK: What is the proper way

to apply the multiple comparison test? Korean J Anesthesiol.

71:353–360. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Rosner B: Fisher's exact test.

Fundamentals of Biostatistics. Cengage; Boston: pp. 387–394.

2019

|

|

24

|

Lydersen S, Pradhan V, Senchaudhuri P and

Laake P: Choice of test for association in small sample unordered r

× c tables. Stat Med. 26:4328–4343. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Guilford JP: Correlation. Fundamental

Statistics in Psychology and Education. McGraw-Hill Book Company;

New York: pp. 154–173. 1950

|

|

26

|

Gospodarowicz M and Mason M: Kidney. TNM

Classification of malignant tumours. O'Sullivan B, Mason M, Asamura

H, et al: Wiley Blackwell; Oxford: pp. 199–203. 2017, PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Capo-chichi CD, Aguida B, Chabi NW, Cai

QK, Offrin G, Agossou VK, Sanni A and Xu XX: Lamin A/C deficiency

is an independent risk factor for cervical cancer. Cell Oncol

(Dordr). 39:59–68. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lammerding J, Fong LG, Ji JY, Reue K,

Stewart CL, Young SG and Lee RT: Lamins A and C but not lamin B1

regulate nuclear mechanics. J Biol Chem. 281:25768–25780. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pujadas Liwag EM, Wei X, Acosta N, Carter

LM, Yang J, Almassalha LM, Jain S, Daneshkhah A, Rao SSP,

Seker-Polat F, et al: Depletion of lamins B1 and B2 promotes

chromatin mobility and induces differential gene expression by a

mesoscale-motion-dependent mechanism. Genome Biol. 25:772024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Harborth J, Elbashir SM, Bechert K, Tuschl

T and Weber K: Identification of essential genes in cultured

mammalian cells using small interfering RNAs. J Cell Sci.

114:4557–4565. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Reis-Sobreiro M, Chen JF, Novitskaya T,

You S, Morley S, Steadman K, Gill NK, Eskaros A, Rotinen M, Chu CY,

et al: Emerin deregulation links nuclear shape instability to

metastatic potential. Cancer Res. 78:6086–6097. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Stewart-Hutchinson PJ, Hale CM, Wirtz D

and Hodzic D: Structural requirements for the assembly of LINC

complexes and their function in cellular mechanical stiffness. Exp

Cell Res. 314:1892–1905. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lombardi ML, Jaalouk DE, Shanahan CM,

Burke B, Roux KJ and Lammerding J: The interaction between nesprins

and sun proteins at the nuclear envelope is critical for force

transmission between the nucleus and cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem.

286:26743–26753. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Matsumoto A, Hieda M, Yokoyama Y, Nishioka

Y, Yoshidome K, Tsujimoto M and Matsuura N: Global loss of a

nuclear lamina component, lamin A/C, and LINC complex components

SUN1, SUN2, and nesprin-2 in breast cancer. Cancer Med.

4:1547–1557. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ueda N, Maekawa M, Matsui TS, Deguchi S,

Takata T, Katahira J, Higashiyama S and Hieda M: Inner nuclear

membrane protein, SUN1, is required for cytoskeletal force

generation and focal adhesion maturation. Front Cell Dev Biol.

10:8858592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Östlund C, Folker ES, Choi JC, Gomes ER,

Gundersen GG and Worman HJ: Dynamics and molecular interactions of

linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton (LINC) complex proteins.

J Cell Sci. 122:4099–4108. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Haque F, Lloyd DJ, Smallwood DT, Dent CL,

Shanahan CM, Fry AM, Trembath RC and Shackleton S: SUN1 interacts

with nuclear lamin A and cytoplasmic nesprins to provide a physical

connection between the nuclear lamina and the cytoskeleton. Mol

Cell Biol. 26:3738–3751. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Nishioka Y, Imaizumi H, Imada J, Katahira

J, Matsuura N and Hieda M: SUN1 splice variants, SUN1_888,

SUN1_785, and predominant SUN1_916, variably function in

directional cell migration. Nucleus. 7:572–584. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sharma VP, Williams J, Leung E, Sanders J,

Eddy R, Castracane J, Oktay MH, Entenberg D and Condeelis JS:

SUN-MKL1 crosstalk regulates nuclear deformation and fast motility

of breast carcinoma cells in fibrillar ECM microenvironment. Cells.

10:15492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mislow JM, Holaska JM, Kim MS, Lee KK,

Segura-Totten M, Wilson KL and McNally EM: Nesprin-1alpha

self-associates and binds directly to emerin and lamin A in vitro.

FEBS Lett. 525:135–140. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Duong NT, Morris GE, Lam le T, Zhang Q,

Sewry CA, Shanahan CM and Holt I: Nesprins: Tissue-specific

expression of epsilon and other short isoforms. PLoS One.

9:e943802014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Sur-Erdem I, Hussain MS, Asif M, Pinarbasi

N, Aksu AC and Noegel AA: Nesprin-1 impact on tumorigenic cell

phenotypes. Mol Biol Rep. 47:921–934. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wilhelmsen K, Litjens SH, Kuikman I,

Tshimbalanga N, Janssen H, van den Bout I, Raymond K and Sonnenberg

A: Nesprin-3, a novel outer nuclear membrane protein, associates

with the cytoskeletal linker protein plectin. J Cell Biol.

171:799–810. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Morgan JT, Pfeiffer ER, Thirkill TL, Kumar

P, Peng G, Fridolfsson HN, Douglas GC, Starr DA and Barakat AI:

Nesprin-3 regulates endothelial cell morphology, perinuclear

cytoskeletal architecture, and flow-induced polarization. Mol Biol

Cell. 22:4324–4334. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Diegmiller R, Doherty CA, Stern T, Imran

Alsous J and Shvartsman SY: Size scaling in collective cell growth.

Development. 148:dev1996632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chiarini F, Paganelli F, Balestra T,

Capanni C, Fazio A, Manara MC, Landuzzi L, Petrini S, Evangelisti

C, Lollini PL, et al: Lamin A and the LINC complex act as potential

tumor suppressors in ewing sarcoma. Cell Death Dis. 13:3462022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lv XB, Liu L, Cheng C, Yu B, Xiong L, Hu

K, Tang J, Zeng L and Sang Y: SUN2 exerts tumor suppressor

functions by suppressing the warburg effect in lung cancer. Sci

Rep. 5:179402015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|