Introduction

Historically, breast cancer management followed a

standard sequence of surgery, followed by chemotherapy and

radiotherapy (1). However, the use

of chemotherapy before surgery, in a neoadjuvant setting, shows

similar survival outcomes to adjuvant therapy (2), but it offers some clinical advantages.

Initially, it was used to downstage and render operable locally

advanced breast cancers that were inoperable from the outset, or to

enable conservative surgery for certain operable, locally advanced

forms (3). Indications of

neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) have extended to include early-stage

triple-negative (TN) and HER2-positive subtypes, supported by the

positive predictive value of pathological complete response (pCR)

for survival (4,5). Studies have demonstrated that

pathological responses to NAC vary between the intrinsic molecular

subtypes (1,6,7).

Pathological response following neoadjuvant chemotherapy was also

used to guide adjuvant systemic. Patients who experience a pCR had

a good prognosis, and did not benefit from adjuvant therapy (except

endocrine therapy in endocrine receptor-positive breast cancer).

HER2-positive and triple negative cancer patients with incomplete

response would benefit from additional adjuvant systemic therapy

(8,9). Most of these studies come from

developed countries, and thus, mostly include White patients

(10,11). However, breast cancer presents

racial and ethnic disparities (12). Therefore, the results of these

studies cannot be generalized systematically to Black African

patients. Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease with molecular

and phenotypical subtypes that vary across racial and ethnic groups

(13). These subtypes influence

prognosis and treatment outcomes (14). In the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire,

breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among female patients,

with 3869 new cases in 2022 (33.5% of all new cancer cases)

according to the Globocan statistics (15). From 2008 to 2015, most cases were

diagnosed at advanced stages (nearly 65% at stages III or IV),

often requiring the use of NAC (16). To the best of our knowledge, pCR

following NAC and its impact on survival outcomes has not yet been

studied. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the

pathological response to NAC and its influence on survival in

patients with breast cancer.

Patients and methods

Patient selection and data

collection

The present study was a retrospective analytical

study of patients treated from January 2017 to December 2024. The

present study included 238 female patients aged ≥18 years.

Inclusion criteria were: Pathologically confirmed, non-metastatic

breast carcinoma who were treated with NAC followed by surgery in

three tertiary hospitals in the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire (Alassane

Ouattara National Center of Medical Oncology and Radiotherapy of

Abidjan, Treichville Hospital and University Center of Abidjan, and

Bouaké Hospital and University Center, Bouaké); available

pathological examination of the surgical specimen.

Description of the chemotherapy protocols, the

number of cycles, and the subsequent treatments such as

radiotherapy, endocrine therapy or adjuvant chemotherapy. The

present study was approved by The National Ethical Committee of

Life and Health Sciences (approval no. 00068/25/MSHPCMU/CNESVS-km)

of Republic of Côte d'Ivoire. All patients gave their written

consent to participate to the study. Pathological and

immunohistochemistry analyses were performed on a breast core

biopsy before the chemotherapy course. Computed tomography scans of

the chest, abdomen and pelvis were performed to rule out distant

metastasis. Pathological, immunohistochemistry and computed

tomography scan data were obtained from the medical records of the

patients. Tumor staging was based on the eighth edition of the

American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer

Control (UICC) system (17).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: Patients who

received radiotherapy prior to surgery; patients with a delay

>12 weeks between NAC and surgery; patients with a delay >6

weeks between cycles of chemotherapy; patients with a follow-up

time <1 year; and patients lost to follow-up after the end of

treatment for whom post-treatment data were unavailable.

The collected data included: Age; tumor stage and

grade; estrogen receptor (ER) status; progesterone receptor (PR)

status; HER2 status; molecular subtype; chemotherapy regimen;

treatment following surgery (radiotherapy, hormonal therapy,

anti-HER2 therapy or adjuvant chemotherapy); pathological response;

and overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS).

Molecular subtypes were categorized as luminal,

HER2-positive or TN based on ER, PR and HER2 status. The ER, PR and

HER2 status was assessed by immunohistochemistry. Data were

extracted from the immunohistochemistry exam reports in the patient

medical records. ER and PR were considered positive if ≥10% of

cells were stained positive. Evaluation of HER2 expression was

based on the degree of membrane staining as follows: 0, no or

incomplete, faint/barely perceptible membrane staining in ≤10% of

invasive tumor cells; 1, incomplete, faint/barely perceptible

membrane staining in >10% of invasive tumor cells; 2, incomplete

and/or weak to moderate circumferential membrane staining in

>10% of invasive tumor cells or complete, intense,

circumferential membrane staining in ≤10% of invasive tumor

cells

Score 3 corresponds to complete, intense,

circumferential membrane staining in >10% of invasive tumor

cells.

HER2 was considered upregulated (HER2-positive) if

the score was 3; scores of 0 and 1 indicated an absence of HER2

upregulation. If the score was 2, an in situ hybridization

test was required.

Tumors were classified as follows: Luminal, ER-

and/or PR-positive, HER2-negative; HER2-positive, HER2-positive

with or without ER or PR expression; and TN, ER-, PR- and

HER2-negative.

pCR was defined as an absence of residual invasive

or micro-invasive disease in both the breast (the primary tumor

site) and axillary lymph nodes (ypT0/ypTis, ypN0 based on the

8th edition of breast cancer staging of the

AJCC)(17). The pathological

response was reported according to whether pCR was achieved

[absence of complete response group (no pCR) and complete response

group (pCR)].

PFS was defined as the time from diagnosis to

recurrence (locoregional and/or distant) or death from any cause.

OS was defined as the time from diagnosis until death from any

cause.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS

Statistics version 27 (https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-27).

Baseline characteristics of patients, tumors and treatment were

presented as mean ± SD) for continuous variables, or as proportions

for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was

performed to detect associations between clinicopathological

variables (age, histological subtype, grade, molecular subtype and

stage) and pathological response. χ2 test was used for

comparison. There was a significant association between the

variable and pathological response if P-value was <0,05. Odd

ratio (OR) and 95% confident interval were reported for each

variable. Survival was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method on an

intention-to-treat basis. Univariate and multivariate analyses were

performed to assess the influence of clinicopathological variables

on PFS and OS. The log-rank test was used for the univariate

analysis. Variables that were significant (P<0.05) in the

univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis

using a Cox regression model. P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinicopathological

characteristics

A total of 195 patients met the selection criteria

and were included in the study. The mean age was 46.3±10.4 years

and 26.7% of patients were aged <40 years. Invasive carcinoma of

no special type was the predominant histology (91.3%). Most tumors

were grade 2 (67.7%) and stage III (69.8%). Immunohistochemistry

revealed that 39.5% of the tumors were positive for ER and/or PR,

8.7% were positive for both HER2 and ER and/or ER, 11.8% were

positive for HER2 only and 40.0% were TN (data not shown). The

molecular subtypes were luminal (39.5%), HER2-positive (20.5%) and

TN (40%). NAC was primarily based on sequential

anthracycline-taxane regimens (94.4%). The number of cycles ranged

from six to eight in 91.3% of patients (data not shown). Among

HER2-positive patients, 32.5% received anti-HER2 therapy

(trastuzumab) as part of the NAC regimen. In the remaining

HER2-positive patients (67.5%), trastuzumab was given in the

adjuvant setting (following surgery). Among TN patients, a platinum

agent (carboplatin) was added to the NAC regimen in 3.8% of cases.

Mastectomy was performed in 75.4% of patients and 95.9% received

postoperative radiotherapy. Endocrine therapy was administered to

all patients with hormone receptor-positive tumors, while adjuvant

capecitabine was given to patients with TN tumors without pCR (data

not shown). pCR was observed in 28.7% of patients based on

pathological examination of the surgical specimen (Table I).

| Table I.Patient and tumor

characteristics. |

Table I.

Patient and tumor

characteristics.

| Variable | Luminal (%) | HER2-positive

(%) | Triple-negative n

(%) | Total (%) |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

<40 | 16 (8.2) | 15 (7.7) | 21 (10.8) | 52 (26.7) |

|

≥40 | 61 (31.3) | 25 (12.8) | 57 (29.2) | 143 (73.3) |

| Histological

subtype |

|

|

|

|

|

NST | 64 (32.8) | 39 (20.0) | 75 (38.5) | 178 (91.3) |

|

Other | 13 (6.7) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) | 17 (8.7) |

| Grade |

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 16 (8.2) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | 22 (11.3) |

| 2 | 53 (27.2) | 29 (14.9) | 50 (25,6) | 132 (67.7) |

| 3 | 8 (4.1) | 8 (4.1) | 25 (12.8) | 41 (21.0) |

| Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

IIA | 8 (4.1) | 4 (2.1) | 4 (2.1) | 16 (8.2) |

|

IIB | 17 (8.7) | 6 (3.1) | 20 (10.3) | 43 (22.1) |

|

IIIA | 25 (12.8) | 11 (5.6) | 17 (8.7) | 53 (27.2) |

|

IIIB | 27 (13.8) | 19 (9.7) | 37 (19.0) | 83 (42.6 |

| Chemotherapy

regimen |

|

|

|

|

|

Anthracycline/taxane | 72 (36.9) | 26 (13.3) | 70 (35.9) | 168 (86.2) |

|

Anthracycline/taxane +

trastuzumab | - | 13 (6.7) | - | 13 (6.7) |

|

Anthracycline/taxane +

carboplatin | - | - | 3 | 3 (1.5) |

|

Anthracycline +

cyclophosphamide | 6 (3.1) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) | 11 (5.6) |

| Response |

|

|

|

|

|

pCR | 18 (9.2) | 17 (8.7) | 21 (10.8) | 56 (28.7) |

| No

pCR | 60 (30.8) | 22 (11.3) | 57 (29.2) | 139 (71.3) |

Association between pCR and

clinicopathological variables

Molecular subtype and tumor stage influenced the

pathological response. Patients with HER2-positive tumors were more

likely to achieve pCR than those with TN subtypes [odds ratio (OR),

2.62; 95% CI, 1.10–6.22). Patients with stage II tumors were also

more likely to achieve pCR than those with stage III tumors (OR,

3.67; 95% CI, 1.82–7.48). However, age, grade and pathological

subtype did not significantly influence the pathological response

(Table II).

| Table II.Logistic regression analysis of the

association between pathological response and clinicopathological

variables. |

Table II.

Logistic regression analysis of the

association between pathological response and clinicopathological

variables.

| Variable | No pCR, n (%) | pCR, n (%) | P-value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

| 0.231 |

|

|

|

<40 | 33 (16.9) | 19 (9.7) |

| 1.57 | 0.75–3.33 |

|

≥40 | 106 (54.4) | 37 (19.0) |

| 1 | - |

| Pathological

subtype |

|

| 0.546 |

|

|

|

NST | 125 (64.1) | 53 (27.2) |

| 1.53 | 0.38–6.17 |

|

Other | 14 (7.2) | 3 (1.5) |

| 1 | - |

| Stage |

|

| <0.001 |

|

|

| II | 32 (16.4) | 27 (13.8) |

| 3.67 | 1.82–7.48 |

|

III | 107 (54.9) | 29 (14.9) |

| 1 | - |

| Grade |

|

| 0.382 |

|

|

| 1 | 19 (9.7) | 3 (1.5) |

| 0.35 | 0.08–1.56 |

| 2 | 93 (47.7) | 39 (20.0) |

| 0.71 | 0.31–1.64 |

| 3 | 27 (13.8) | 14 (7.2) |

| 1 | - |

| Molecular

subtype |

|

| 0.048 |

|

|

|

Luminal | 60 (30.8) | 17 (8.7) |

| 0.94 | 0.41–2.11 |

|

HER2-positive | 22 (11.3) | 18 (9.2) |

| 2.62 | 1.10–6.22 |

|

Triple-negative | 57 (29.2) | 21 (10.8) |

| 1 | - |

Univariate analysis

The 5-year PFS and OS rates were 68.4% (median,

40.23 months) and 78% (median, 42.13 month), respectively, with a

median follow-up of 49.4 months. Stage and pathological response

significantly influenced the 5-year PFS and OS rates. Patients with

stage II tumors had significantly higher 5-year PFS and OS rates

than patients with stage III tumors (81.9 vs. 62.7%; and 93 vs.

71.2%, respectively). pCR was associated with significantly higher

5-year PFS and OS rates than no pCR (96.1 vs. 57.7%; and 95 vs.

71.6%, respectively; Table

III).

| Table III.Univariate analysis by the log-rank

test. |

Table III.

Univariate analysis by the log-rank

test.

| Variable | 5-year PFS (%) | P-value | 5-year OS (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

| 0.452 |

| 0.562 |

|

≤40 | 69.5 |

| 84.6 |

|

|

>40 | 67.7 |

| 75.5 |

|

| Histological

subtype |

| 0.623 |

| 0.787 |

|

NST | 70.4 |

| 77.1 |

|

|

Other | 53.3 |

| 86.7 |

|

| Grade |

| 0.771 |

| 0.396 |

| 1 | 55.1 |

| 84.8 |

|

| 2 | 69.8 |

| 78.9 |

|

| 3 | 71.5 |

| 69.9 |

|

| Molecular

subtype |

| 0.389 |

| 0.371 |

|

Luminal | 70.7 |

| 83.1 |

|

|

HER2-positive | 68.9 |

| 79.9 |

|

|

Triple-negative | 64.7 |

| 71.9 |

|

| Stage |

| 0.005 |

| 0.006 |

| II | 81.9 |

| 93 |

|

|

III | 62.7 |

| 71.2 |

|

| Response |

| <0.001 |

| 0.002 |

|

pCR | 96.1 |

| 95 |

|

| No

pCR | 57.7 |

| 71.6 |

|

Multivariate analysis

Tumor stage significantly influenced the 5-year OS

but not the 5-year PFS [hazard ratio (HR), 0.32; 95% CI, 0.11–0.93

for OS; and HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.22–1.02 for PFS. Pathological

response significantly influenced both 5-year PFS and OS (HR, 6.54;

95% CI, 2.02–21.19 for PFS; HR, 5.84; 95% CI, 1.39–24.54 for OS;

Table IV).

| Table IV.Multivariate analysis by the Cox

model. |

Table IV.

Multivariate analysis by the Cox

model.

|

| Progression-free

survival | Overall

survival |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|

| Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| II | 0.055 | 0.47 | 0.22–1.02 | 0.036 | 0.32 | 0.11–0.93 |

|

III |

| 1.00 | - |

| 1 | - |

| Response |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

pCR | 0.002 | 6.54 | 2.02–21.19 | 0.016 | 5.84 | 1.39–24.54 |

| No

pCR |

| 1 | - |

| 1 | - |

Survival rate according to

pathological response in patients with different molecular

subtypes

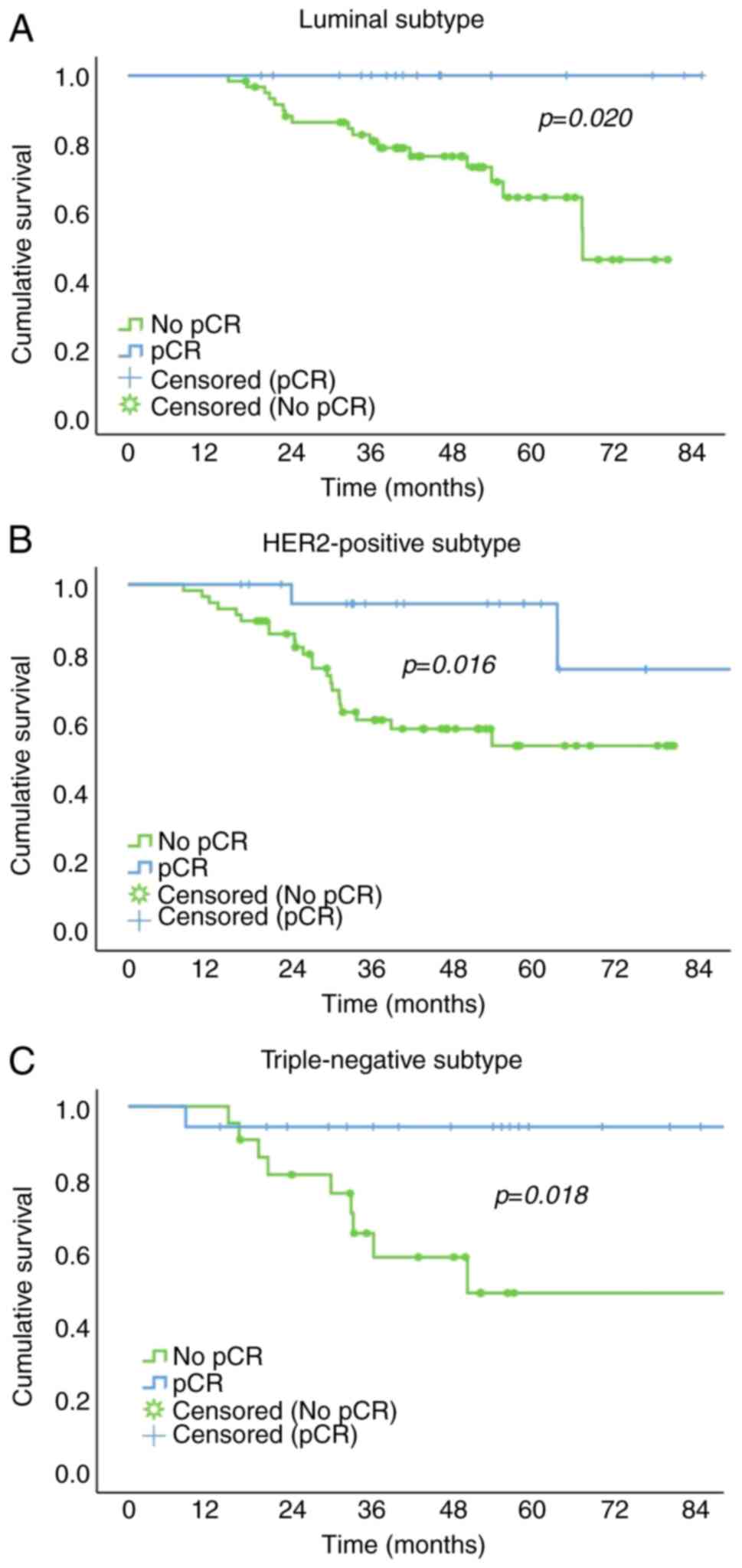

Within each molecular subtype group, the 5-year PFS

rate of the pCR group was significantly higher than that of the no

pCR group [100.0 vs. 64.2% for the luminal subtype; 94.4 vs. 49%

for the HER2-positive subtype; and 94.4 vs. 53.5% for the TN

subtype; Fig. 1).

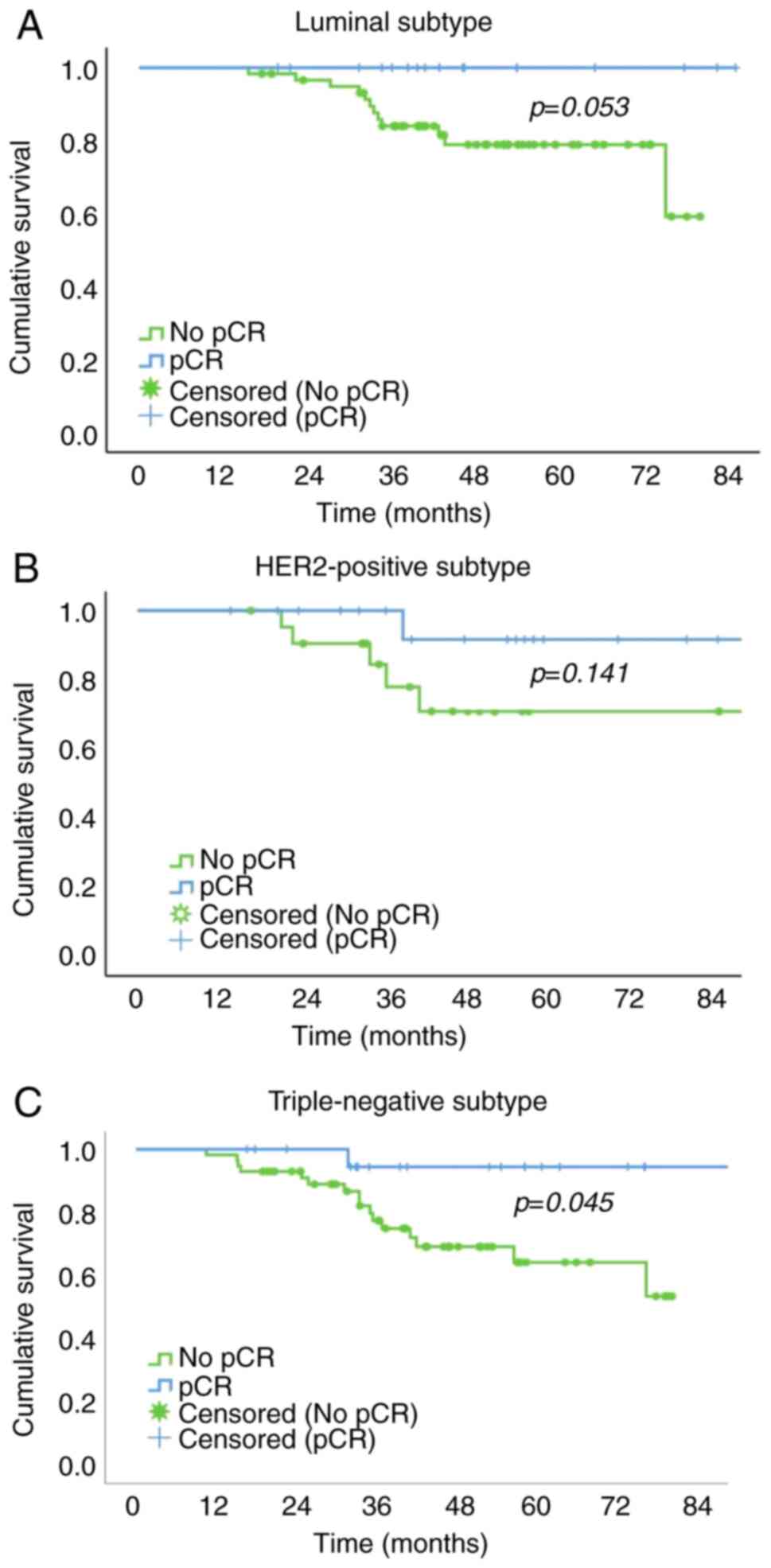

The pCR group had a significantly higher 5-year OS

rate than the no pCR group in patients with the TN subtype (64.3

vs. 94.4%;). In patients with the luminal and HER2-positive

subtypes, the 5-year OS rate of the pCR group was higher than that

of the no pCR group, but the difference was not significant (100.0

vs. 78.9% for luminal subtype; and 91.7 vs. 70.9% for HER2-positive

subtype, respectively; Fig. 2).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the

response to NAC and determine its impact on survival rates in

patients with breast cancer. Approximately one-third of patients

experienced pCR following NAC. This result is similar to that of

Farrukh et al (18), who

reported a pCR rate of 27.2%, using the same definition as the

present study (absence of residual invasive or micro-invasive

disease in both the breast and axillary lymph nodes, residual in

situ disease). Cirier et al (19) and Cortazar et al (20) obtained lower pCR rates of 16 and

13%, respectively. The definition of pCR in the aforementioned

studies (the absence of any invasive or in situ carcinoma)

may explain the low pCR rates. However, Müller et al

(21), using the same definition as

the present study, reported a higher pCR rate (47%) than the

present study. The chemotherapy regimen and drugs (anti-HER2) used

in the aforementioned study could explain the high pCR rate.

Studies have shown that the use of anti-HER2 therapy increases the

pCR in HER2-positive cancer (22–24).

In TN breast cancer, combination of platinum agents with

conventional chemotherapeutic agents (anthracyclines and taxanes)

has also been shown to be superior to sole conventional therapeutic

agents (25). Adding carboplatin to

anthracycline/taxane regimens improves pCR in early-stage TN breast

cancer (25). In the present study,

one-third of HER2-positive patients received anti-HER2 therapy as

part of their chemotherapy regimen, and a small percentage (1.5%)

of patients with TN breast cancer received carboplatin. This was

because immunohistochemistry results of most patients were not

available at the time of NAC.

In addition to the definition of pCR and the

chemotherapy regimen, other clinical and pathological factors

influence response rates. Several studies have identified tumor

biology as the strongest factor influencing the probability of

achieving pCR (6,26–29).

HER2-positive and TN breast cancers are more likely to respond to

NAC compared to hormone receptor-positive cancers (6,29). In

the present study, HER2-positive tumors were associated with a

higher probability of pCR compared to triple negative . The present

results were similar to those of Swain et al (7). TN breast cancer was an important

concern in the present study owing to its high frequency. In

contrast to occidental and east and south African series (12,30,31),

the present study reported a high rate of TN breast cancer (40%)

similar to other west African studies (32,33).

probability of pCR in TN tumors was not significantly different

from luminal subtype. This may be explained by the molecular

heterogeneity of TN breast cancer. According to Lehmann et

al (34), TN breast cancers can

be subdivided into four subtypes [basal-like 1 and 2, mesenchymal

and luminal androgen receptor (AR)], which have different clinical

and pathological characteristics. The basal-like 1 group

demonstrates the highest response rate to NAC, while the basal-like

2 group demonstrates the lowest response rate. Most studies that

have demonstrated a high rate of pCR in patients with TN breast

cancer mostly included non-Black or non-African patients (6,10,35).

The present sample was composed of Black African patients, whose

molecular characteristics differ from those of White or Asian

patients (10,36). However, a recent study by Rajagopal

et al (13) found that young

Black female patients have similar proportions of basal-like 1 and

mesenchymal subtypes to European or Asian patients, a smaller

relative proportion of luminal AR-type tumors and a larger

proportion of non-subtyped tumors. Independent of the Lehmann

classification of triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC), a distinct

subgroup lacking androgen receptor (AR) expression referred to as

quadruple-negative breast cancer (QNBC) has been identified

(37,38). This subtype is predominantly

observed in West African and African-American populations.

(36). Notably, the prognostic

impact of AR negativity appears to vary between ethnic and racial

groups (39). In West African

(particularly Nigerian), African-American, and Asian women, the

absence of AR expression has been associated with chemoresistance

and reduced overall survival (39–41).

In the present study, tumor stage influenced the

pathological response. Stage II was associated with a significantly

higher probability of pCR than stage III. The present results are

consistent with those of Goorts et al (42), who demonstrated that tumor stage was

an independent and strong predictor of pCR compared with HER2, ER

and PR status, and grade.

In the present study, pCR was the sole independent

predictive factor for improved PFS and OS. The molecular subtype

did not influence OS or PFS. However, achieving a pCR was

associated with a significantly improved 5-year PFS rate in each

molecular subtype. In the TN group, pCR was associated with

significantly improved 5-year OS. The present findings are

consistent with those of Cortazar et al (20), who found an increase in event-free

survival with pCR in each molecular subtype, although this was

weakest for hormone receptor-positive and low-grade tumors. Spring

et al (43) found that pCR

was associated with improved OS and event-free survival in the TN

and HER2-positive subtypes. von Minckwitz et al (5) demonstrated that pCR improved

disease-free survival in luminal B/HER2-negative,

HER2-positive/non-luminal and TN tumors, but not in luminal or

luminal B/HER2-positive cancer. When evaluating the long-term

results of the Alliance study (trial no. ACOZOG Z1071), Boughey

et al (26) found that

breast cancer-specific survival rates were higher in the pCR group

compared with no pCR (residual disease) for the hormone

receptor-positive and TN groups, but not for the HER2-positive

group.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was

the first to evaluate the impact of pathological response to NAC on

breast cancer survival in patients from the Republic of Côte

d'Ivoire. However, it has limitations that should be noted,

including the retrospective nature of the study, the absence of

centralized pathological exams and the absence of Ki67 testing. The

pathological exams were performed in different laboratories with

different techniques and preparation conditions. A centralized

examination would allow the specimens to be subjected to the same

preparation conditions to ensure the robustness of the results. The

retrospective nature of the present study prevented control of

specimen handling and NAC administration. The proliferation index

Ki67 data, which distinguishes between low- and high-grade cancer,

were not available. In the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire,

immunohistochemistry testing of endocrine (estrogen and

progesterone) receptors and HER2, but not Ki67, is free for

patients with breast cancer. Therefore, Ki67 testing was not

systematically performed. Consequently, the intrinsic subtype

classification did not differentiate cancers into luminal A and B,

nor into HER2-positive/hormone receptor-positive and

HER2-positive/hormone receptor-negative.

In the present study, pCR after NAC in breast cancer

was found to be a positive predictor of progression-free and OS.

While previous studies found a higher pCR rate in the TN subgroup

(6,29), the present study found that the

probability to achieve pCR was not significantly different between

TN and luminal subgroups. This indicated that TN breast cancer was

less sensitive to chemotherapy, potentially due to predominant

expression of AR in TN tumors. Future studies should investigate

the genetics and phenotype of TN cancer.

Although the TN subtype was not significantly

associated with a higher probability of pCR rate than the other

subgroups, reaching a pCR resulted in significantly improved OS.

These findings support the use of intensify NAC regimens for this

molecular subgroup to improve survival rates. Immune checkpoint

inhibitors have proven efficacy with an acceptable toxicity profile

in neoadjuvant treatment of TN tumors (44). However, these chemotherapeutic

agents are not currently available in the Republic of Côte

d'Ivoire. Access to immune checkpoint inhibitors may improve

survival rates in patients with breast cancer. Pertuzmab in

combination with chemotherapy resulted in a higher response rate in

HER2-positive breast cancer (23).

In the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, anti-HER2 therapies are available

free of charge (since 2018 for trastuzumab and 2024 for

pertuzumab). However, delays in immunohistochemistry testing due to

lack of facilities and qualified personnel hamper the use of

anti-HER2 therapy and platinum agents in HER2-positive and TN

patients, respectively. Centralization of pathology services and

personal training programs may address this problem.

In conclusion, NAC for breast cancer resulted in pCR

in approximately one-third of patients. Tumors positive for HER2

demonstrated the highest probability of pCR following neoadjuvant

chemotherapy. A pathological response following NAC was the most

relevant factor influencing PFS and OS in all patients. For each

molecular subtype, pCR was associated with a significantly higher

PFS rate. Therefore, the pathological response following NAC was

the strongest predictive factor of improved PFS, particularly in

the TN subtype.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ENS designed the study, analyzed and interpreted

data, and wrote the manuscript. DAT designed the study and wrote

the manuscript. CTS, AGT and KT analyzed and interpreted data. BD

conceived the study. AGT and DAT confirmed the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by The National

Ethical Committee of Life and Health Sciences (approval no.

00068/25/MSHPCMU/CNESVS-km; Côte d'Ivoire. All patients gave their

written consent to participate to the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the artificial intelligence

tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate

content of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Leon-Ferre RA, Hieken TJ and Boughey JC:

The landmark series: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for triple-negative

and HER2-positive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 28:2111–2119.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Early Breast Cancer Trialists'

Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), . Early Breast Cancer Trialists'

Collaborative Group (EBCTCG): Long-term outcomes for neoadjuvant

versus adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer: Meta-analysis

of individual patient data from ten randomised trials. Lancet

Oncol. 19:27–39. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

King TA and Morrow M: Surgical issues in

patients with breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Nat

Rev Clin Oncol. 12:335–343. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Provenzano E: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for

breast cancer: Moving beyond pathological complete response in the

molecular age. Acta Med Acad. 50:88–109. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU,

Costa SD, Eidtmann H, Fasching PA, Gerber B, Eiermann W, Hilfrich

J, Huober J, et al: Definition and impact of pathologic complete

response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various

intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 30:1796–1804. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Houssami N, Macaskill P, von Minckwitz G,

Marinovich ML and Mamounas E: Meta-analysis of the association of

breast cancer subtype and pathologic complete response to

neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 48:3342–3354. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Swain SM, Tang G, Lucas PC, Robidoux A,

Goerlitz D, Harris BT, Bandos H, Geyer CE Jr, Rastogi P, Mamounas

EP and Wolmark N: Pathologic complete response and outcomes by

intrinsic subtypes in NSABP B-41, a randomized neoadjuvant trial of

chemotherapy with trastuzumab, lapatinib, or the combination.

Breast Cancer Res Treat. 178:389–399. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

von Minckwitz G, Huang CS, Mano MS, Loibl

S, Mamounas EP, Untch M, Wolmark N, Rastogi P, Schneeweiss A,

Redondo A, et al: Trastuzumab emtansine for residual invasive

HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 380:617–628. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, Im YH, Lee ES,

Yokota I, Kuroi K, Im SA, Park BW, Kim SB, et al: Adjuvant

capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N

Engl J Med. 376:2147–2159. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ding YC, Steele L, Warden C, Wilczynski S,

Mortimer J, Yuan Y and Neuhausen SL: Molecular subtypes of

triple-negative breast cancer in women of different race and

ethnicity. Oncotarget. 10:198–208. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Huo D, Hu H, Rhie SK, Gamazon ER,

Cherniack AD, Liu J, Yoshimatsu TF, Pitt JJ, Hoadley KA, Troester

M, et al: Comparison of breast cancer molecular features and

survival by african and european ancestry in the cancer genome

atlas. JAMA Oncology. 3:1654–1662. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Keenan T, Moy B, Mroz EA, Ross K,

Niemierko A, Rocco JW, Isakoff S, Ellisen LW and Bardia A:

Comparison of the genomic landscape between primary breast cancer

in African American versus white women and the association of

racial differences with tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol.

33:3621–3627. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rajagopal PS, Reid S, Fan R, Venton L,

Weidner A, Roberson ML, Vadaparampil S, Wang X, Yoder S, Rosa M, et

al: Population-specific patterns in assessing molecular subtypes of

young black females with triple-negative breast cancer. NPJ Breast

Cancer. 11:282025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Martini R, Newman L and Davis M: Breast

cancer disparities in outcomes; unmasking biological determinants

associated with racial and genetic diversity. Clin Exp Metastasis.

39:7–14. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Global Cancer Observatory, . Cancer Today.

Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Available from. https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/384-cote-divoire-fact-sheetMay

2–2024

|

|

16

|

Joko-Fru WY, Miranda-Filho A,

Soerjomataram I, Egue M, Akele-Akpo MT, N'da G, Assefa M, Buziba N,

Korir A, Kamate B, et al: Breast cancer survival in sub-Saharan

Africa by age, stage at diagnosis and human development index: A

population-based registry study. Int J Cancer. 146:1208–1218. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Teichgraeber DC, Guirguis MS and Whitman

GJ: Breast cancer staging: Updates in the AJCC cancer staging

manual, 8th edition, and current challenges for radiologists, from

the AJR special series on cancer staging. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

217:278–290. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Farrukh N, Bano R, Naqvi SRQ and Latif H:

Assessment of pathological complete response in patients with

breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant systemic therapy. J Coll

Physicians Surg Pak. 32:746–750. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cirier J, Body G, Jourdan ML, Bédouet L,

Fleurier C, Pilloy J, Arbion F and Ouldamer L: Impact de la réponse

histologique complète à la chimiothérapie néo-adjuvante pour cancer

du sein selon le sous-type moléculaire. Gynécol Obstétrique

Fertilité Sénologie. 45:535–544. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch ML, Bedouet L,

Fleurier C, Pilloy J, Arbion F and Ouldamer L: Pathological

complete response and Long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer:

The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 384:164–172. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Müller C, Schmidt G, Juhasz-Böss I, Jung

L, Huwer S, Solomayer EF and Juhasz-Böss S: Influences on

pathologic complete response in breast cancer patients after

neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 304:1065–1071. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Foldi J, Mougalian S, Silber A, Lannin D,

Killelea B, Chagpar A, Horowitz N, Frederick C, Rispoli L, Burrello

T, et al: Single-arm, neoadjuvant, phase II trial of pertuzumab and

trastuzumab administered concomitantly with weekly paclitaxel

followed by 5-fluoruracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC)

for stage I–III HER2-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res

Treat. 169:333–340. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, Roman L,

Tseng LM, Liu MC, Lluch A, Staroslawska E, de la Haba-Rodriguez J,

Im SA, et al: Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and

trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early

HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): A randomised multicentre,

open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 13:25–32. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Untch M, Rezai M, Loibl S, Fasching PA,

Huober J, Tesch H, Bauerfeind I, Hilfrich J, Eidtmann H, Gerber B,

et al: Neoadjuvant treatment with trastuzumab in HER2-positive

breast cancer: results from the GeparQuattro study. J Clin Oncol.

28:2024–2031. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sharma P, Connolly RM, Roussos Torres ET

and Thompson A: Best foot forward: Neoadjuvant systemic therapy as

standard of care in triple-negative and HER2-positive breast

cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 40:1–16. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Boughey JC, Ballman KV, McCall LM,

Mittendorf EA, Symmans WF, Julian TB, Byrd D and Hunt KK: Tumor

biology and response to chemotherapy impact breast cancer-specific

survival in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with

neoadjuvant chemotherapy: Long-term follow-up from ACOSOG Z1071

(Alliance). Ann Surg. 266:667–676. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hieken TJ, Murphy BL, Boughey JC, Degnim

AC, Glazebrook KN and Hoskin TL: Influence of biologic subtype of

inflammatory breast cancer on response to neoadjuvant therapy and

cancer outcomes. Clin Breast Cancer. 18:e501–e506. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Prat A, Fan C, Fernández A, Hoadley KA,

Martinello R, Vidal M, Viladot M, Pineda E, Arance A, Muñoz M, et

al: Response and survival of breast cancer intrinsic subtypes

following multi-agent neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BMC Med.

13:3032015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rouzier R, Perou CM, Symmans WF, Ibrahim

N, Cristofanilli M, Anderson K, Hess KR, Stec J, Ayers M, Wagner P,

et al: Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to

preoperative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 11:5678–5685. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hadgu E, Seifu D, Tigneh W, Bokretsion Y,

Bekele A, Abebe M, Sollie T, Merajver SD, Karlsson C and Karlsson

MG: Breast cancer in Ethiopia: Evidence for geographic difference

in the distribution of molecular subtypes in Africa. BMC Womens

Health. 18:402018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Brandão M, Guisseve A, Bata G, Alberto M,

Ferro J, Garcia C, Zaqueu C, Lorenzoni C, Leitão D, Come J, et al:

Breast cancer subtypes: implications for the treatment and survival

of patients in Africa-a prospective cohort study from Mozambique.

ESMO Open. 5:e0008292020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Adeniji AA, Dawodu OO, Habeebu MY, Oyekan

AO, Bashir MA, Martin MG, Keshinro SO and Fagbenro GT: Distribution

of breast cancer subtypes among nigerian women and correlation to

the risk factors and clinicopathological characteristics. World J

Oncol. 11:165–172. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Seshie B, Adu-Aryee NA, Dedey F,

Calys-Tagoe B and Clegg-Lamptey JN: A retrospective analysis of

breast cancer subtype based on ER/PR and HER2 status in Ghanaian

patients at the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Ghana. BMC Clin Pathol.

15:142015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lehmann BD, Jovanović B, Chen X, Estrada

MV, Johnson KN, Shyr Y, Moses HL, Sanders ME and Pietenpol JA:

Refinement of triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes:

Implications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy selection. PLoS One.

11:e01573682016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen XS, Wu JY, Huang O, Chen CM, Wu J, Lu

JS, Shao ZM, Shen ZZ and Shen KW: Molecular subtype can predict the

response and outcome of Chinese locally advanced breast cancer

patients treated with preoperative therapy. Oncol Rep.

23:1213–1220. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jiagge E, Jibril AS, Chitale D,

Bensenhaver JM, Awuah B, Hoenerhoff M, Adjei E, Bekele M, Abebe E,

Nathanson SD, et al: Comparative analysis of breast cancer

phenotypes in African American, White American, and West versus

east African patients: Correlation between African ancestry and

triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 23:3843–3849. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Davis M, Tripathi S, Hughley R, He Q, Bae

S, Karanam B, Martini R, Newman L, Colomb W, Grizzle W and Yates C:

AR negative triple negative or ‘quadruple negative’ breast cancers

in African American women have an enriched basal and immune

signature. PLoS One. 13:e01969092018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Saini G, Bhattarai S, Gogineni K and Aneja

R: Quadruple-negative breast cancer: An uneven playing field. JCO

Glob Oncol. 6:233–237. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bhattarai S, Klimov S, Mittal K,

Krishnamurti U, Li XB, Oprea-Ilies G, Wetherilt CS, Riaz A,

Aleskandarany MA, Green AR, et al: Prognostic role of androgen

receptor in triple negative breast cancer: A Multi-institutional

study. Cancers (Basel). 11:9952019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Asano Y, Kashiwagi S, Goto W, Tanaka S,

Morisaki T, Takashima T, Noda S, Onoda N, Ohsawa M, Hirakawa K and

Ohira M: expression and clinical significance of androgen receptor

in Triple-negative breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 9:42017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Thike AA, Yong-Zheng Chong L, Cheok PY, Li

HH, Wai-Cheong Yip G, Huat Bay B, Tse GM, Iqbal J and Tan PH: Loss

of androgen receptor expression predicts early recurrence in

triple-negative and basal-like breast cancer. Mod Pathol.

27:352–360. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Goorts B, van Nijnatten TJA, de Munck L,

Moossdorff M, Heuts EM, de Boer M, Lobbes MB and Smidt ML: Clinical

tumor stage is the most important predictor of pathological

complete response rate after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast

cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 163:83–91. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Spring LM, Fell G, Arfe A, Sharma C,

Greenup R, Reynolds KL, Smith BL, Alexander B, Moy B, Isakoff SJ,

et al: Pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy

and impact on breast cancer recurrence and survival: A

comprehensive Meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 26:2838–2848. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Villacampa G, Navarro V, Matikas A,

Ribeiro JM, Schettini F, Tolosa P, Martínez-Sáez O, Sánchez-Bayona

R, Ferrero-Cafiero JM, Salvador F, et al: Neoadjuvant immune

checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy in early breast cancer: A

systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 10:1331–1341.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|