Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks as the sixth

most prevalent cancer globally and the fourth leading cause of

cancer-related mortality. There were an estimated 905,000 new cases

and 830,000 associated deaths worldwide in 2020 (1). The primary curative treatment options

for HCC include liver transplantation (LT) and liver resection

(LR). Currently, LR is the most commonly employed treatment, aimed

at tumor eradication and extending overall survival (OS) time in

patients with compensated liver function (2). However, HCC resectability is

contingent on several factors, including liver function, cirrhosis

status with portal hypertension, tumor size and number, tumor

location, clinical staging and the overall health of the patient.

LR is generally more effective in patients with HCC who have

Child-Pugh A liver function, with or without cirrhosis and portal

hypertension (3). However, the

recurrence rate (RR) of HCC after LR can approach 50% within the

first few years, likely due to the presence of occult HCC foci in

the residual liver, circulating cancer cells returning to the liver

to form novel tumors or de novo HCC development due to the

underlying liver disease in the remnant liver (4).

By contrast, the HCC RR following LT has been

recorded as ~17% (range, 15–19%) (5), with a >30% reduction in absolute RR

post-LT compared with that observed in LR (4). LT not only removes the tumor but also

addresses the underlying chronic liver disease and associated

complications, such as portal hypertension (6). However, LT has its limitations,

including organ donor shortages, extended waiting times, the need

for lifelong immunosuppressive therapy and the associated risk of

infections. Therefore, the debate continues regarding which

treatment, LR or LT, should be the preferred initial option for

HCC.

The core requirements of Milan criteria are as

follows: A single tumor with a diameter ≤5 cm, or up to 3 tumors

each ≤3 cm in diameter, with no vascular invasion or extrahepatic

metastasis, represent the first internationally recognized

guidelines for LT in liver cancer (7). Patients with HCC meeting these

criteria who undergo LT achieve a 4-year OS rate of up to 85% and a

disease-free survival (DFS) rate of 92%. The efficacy of LT within

the Milan criteria has been validated by multiple transplant

centers globally. Previous studies have indicated that 20–25% of

patients with liver cancer are eligible for both LT and LR, making

the decision for first-line treatment more complex (8–11). Due

to the numerous factors that complicate direct comparisons between

these two surgical approaches, their respective advantages and

prognostic differences remain contentious. Therefore, the present

study utilized a meta-analysis to compare the prognosis of patients

with HCC undergoing LT and LR within the Milan criteria,

specifically focusing on differences in OS and DFS rates, to

provide additional evidence-based guidance for clinical

decision-making in the future.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted across multiple

databases, including PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Embase (http://www.embase.com/), Cochrane (http://www.cochranelibrary.com/), Web of Science

(Medline) (https://www.webofscience.com/), OVID (https://www.ovid.com/), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/), China National Knowledge

Infrastructure (http://www.cnki.net/), Value-Added

Information Provider (https://qikan.cqvip.com/), Wanfang (https://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/index.html) and China

Biology Medicine (http://www.sinomed.ac.cn/zh/), to identify studies

evaluating the prognosis of LT and LR in patients with HCC meeting

the Milan criteria. The search, which spanned from the inception of

each database to June 2024, utilized a combination of index terms

and text words. Key search terms included ‘liver cancer’,

‘hepatocellular carcinoma’, ‘HCC’, ‘liver transplantation’, ‘LT’,

‘liver resection’ and ‘LR’ (the terms HCC, LT and LR were also

searched for separately as the abbreviations), among others

(Data S1). Furthermore, references

cited in relevant studies were also reviewed to ensure

comprehensive retrieval.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Studies

comparing the efficacy and prognosis of LT and LR for HCC; ii)

patients with HCC meeting the Milan criteria, with pathological

confirmation; iii) interventions involving LR or LT; iv) studies

providing relevant outcome data, including 1-, 3-, 5- and 10-year

OS, DFS and RR; and v) full-text articles available in either

Chinese or English. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Animal studies; ii) meta-analyses, systematic reviews, reviews,

case reports, degree thesis, editorials and conference abstracts;

iii) studies lacking primary research indicators or duplicated from

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program database data

(https://seer.cancer.gov/); iv) studies with

<10 cases in either the LT or LR groups; and v) studies where

full text could not be accessed.

Data extraction and quality

assessment

Data extraction was performed independently by two

reviewers using a standardized table, with discrepancies resolved

by a third reviewer. Extracted data included: i) Study details

[author, publication date, country, sample size for LT and LR

groups, transplant center name, treatment intent, sex, liver

function classification (12),

vascular invasion and follow-up period]; and ii) outcome measures

(OS and DFS rates, and RR, at 1-, 3-, 5- and 10-years

post-treatment). The quality of retrospective cohort studies was

assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (13), evaluating study subject selection,

group comparability and outcome measurement. The total score of the

scale was 9 points, with a score of ≥7 points indicating

high-quality studies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review

Manager software (version 5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration). Odds

ratios (OR) were calculated for binary variables, with 95%

confidence interval (CI) provided for each estimate. Heterogeneity

among studies was assessed using the χ2 test, with

I2 quantifying the degree of heterogeneity. High

heterogeneity was defined by P<0.05 and I2>50%,

while low heterogeneity was indicated by P≥0.05 and

I2≤50%. A random effects model was used for all

comparisons, in line with previous evidence suggesting its greater

reliability compared with the fixed effects model (14). Sensitivity analysis was conducted to

explore sources of heterogeneity and publication bias was evaluated

using a funnel plot. The χ2 test was also used to

analyze differences in cirrhosis severity, sex and microvascular

invasion (MVI), with P<0.05 considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of the included

studies and quality assessment

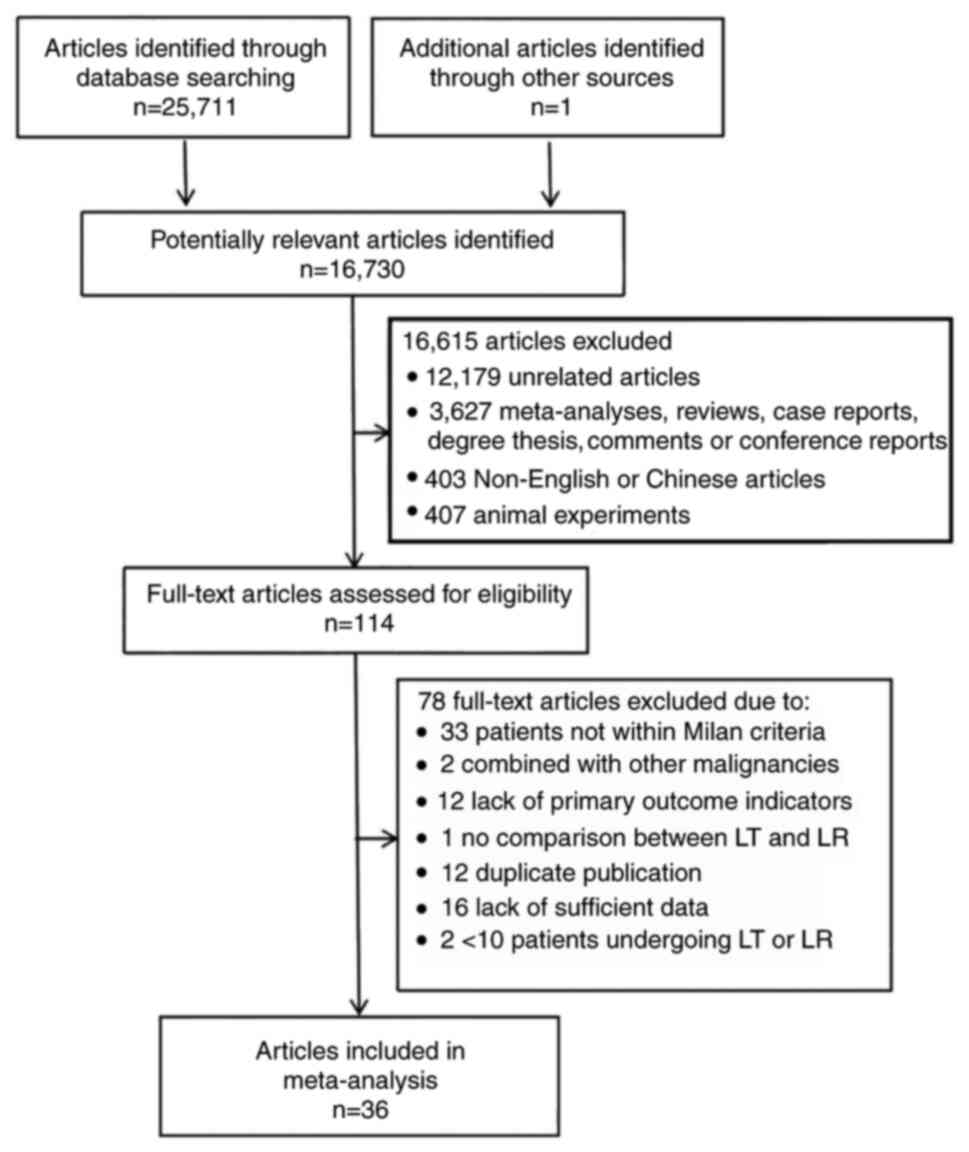

As illustrated in Fig.

1, a total of 25,712 articles were retrieved. After applying

the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 36 articles were selected,

comprising 30 English-language studies (15–43)

and 6 Chinese-language studies (44–49),

all of which were retrospective cohort studies. The included

studies involved a total of 6,839 patients, with 3,894 in the LR

group and 2,945 in the LT group. The basic characteristics of these

studies are summarized in Tables I

and II, while the quality

assessment results are presented in Table III. All studies were of high

quality, scoring ≥7 according to the NOS. Table IV provides a detailed description

of the basic characteristics of the patients with HCC. For patients

with liver cancer undergoing LR or LT, sex, liver function and

tumor vascular invasion status are closely related to the

prognosis. As the hormone levels influence tumor progression, and

microvascular invasion reflects the tumor's aggressiveness and is

directly linked to the risk of recurrence, liver function reserve

determines treatment tolerance and recovery capacity. There were no

statistically significant differences between the LR and LT groups

in terms of sex distribution (P=0.697). However, a significant

difference was observed in the severity of cirrhosis and MVI

distribution between the two groups, (P<0.001 and P=0.006,

respectively) (Table V). In

addition, among the 36 included articles, 5 did not provide a

detailed description of the dropout rate (18,25,32,36,49), 4

had dropout rates (15,16,33,44)

and the remaining 27 did not have dropout rates.

| Table I.Characteristics of the included

studies. |

Table I.

Characteristics of the included

studies.

|

|

|

| OS (LR/LT), % | DFS (LR/LT), % | Number of

recurrences |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | LR, n | LT, n | 1-year | 3-year | 5-year | 10-year | 1-year | 3-year | 5-year | 10-year | LR | LT | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Margarit et

al, 2005 | 37 | 36 | 92.0/78.0 | NA | 70.0/65.0 | 50.0/60.0 | 84.0/77.0 | NA | 39.0/64.0 | 18.0/56.0 | 22 | 4 | (19) |

| Jiang et al,

2014 | 33 | 34 | 84.8/94.1 | 64.0/91.2 | 51.2/76.5 | NA | NA | 35.6/72.0 | 19.8/41.0 | NA | 22 | 6 | (15) |

| Foltys et

al, 2014 | 30 | 31 | NA | NA | 57.9/42.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (20) |

| Bigourdan et

al, 2003 | 20 | 17 | NA | 67.0/87.0 | 36.0/71.0 | NA | NA | 52.0/87.0 | 40.0/80.0 | NA | NA | NA | (21) |

| Sogawa et

al, 2013 | 56 | 52 | 85.1/75.0 | 65.4/59.4 | 51.6/51.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 34 | 12 | (22) |

| Moon et al,

2007 | 100 | 17 | 92.9/94.1 | 79.0/94.1 | 66.5/94.1 | NA | 78.1/100 | 65.4/75.0 | 54.5/75.0 | NA | 36 | 1 | (23) |

| Bellavance et

al, 2008 | 245 | 134 | 93.0/91.0 | 71.0/79.0 | 46.0/66.0 | NA | 88.0/96.0 | 62.0/89.0 | 40.0/82.0 | NA | 122 | 19 | (24) |

| Squires et

al, 2014 | 45 | 131 | NA | NA | 43.8/65.7 | NA | NA | NA | 22.7/85.3 | NA | NA | NA | (25) |

| Michelakos et

al, 2019 | 95 | 89 | NA | 76.0/82.0 | 62.0/77.0 | 41.0/53.0 | NA | 48.0/96.0 | 44.0/94.0 | 31.0/94.0 | NA | NA | (18) |

| Meyerovich et

al, 2019 | 30 | 54 | 92.1/81.2 | 78.1/56.4 | 55.2/47.0 | NA | 73.4/89.4 | 53.6/62.4 | 27.8/56.2 | NA | 4 | 15 | (26) |

| Krenzien et

al, 2018a | 30 | 123 | NA | NA | 36.0/77.0 | NA | NA | NA | 29.0/76.0 | NA | NA | NA | (27) |

| Krenzien et

al, 2018b | 29 | 91 | NA | NA | 61.0/73.0 | NA | NA | NA | 40.0/70.0 | NA | NA | NA | (27) |

| Park et al,

2017 | 199 | 137 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 73.9/92 | 54.6/87.1 | NA | NA | 79 | 19 | (14) |

| Li et al,

2017 | 61 | 31 | 93.4/100 | 63.1/91.1 | 51.2/85.4 | NA | 68.9/100 | 48.4/87.4 | 38.6/80.1 | NA | NA | NA | (16) |

| Huang et al,

2016 | 254 | 49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 82.0/86.0 | 61.0/80.0 | 45.0/80.0 | 31.0/68.0 | 140 | 8 | (28) |

| Li et al,

2014 | 243 | 39 | 96.3/100 | 83.9/85.2 | 76.2/81.0 | NA | 79.8/89.7 | 59.7/83.5 | 50.9/79.3 | NA | NA | NA | (29) |

| Dai et al,

2014 | 25 | 13 | 100/100 | 93.3/91.7 | 93.3/91.7 | NA | 92.0/92.3 | 71.7/92.3 | 64.5/92.3 | NA | NA | NA | (30) |

| Poon et al,

2007 | 204 | 43 | NA | NA | 68.0/81.0 | NA | NA | NA | 44.0/84.0 | NA | NA | NA | (31) |

| Baccarani et

al, 2008 | 38 | 48 | 82.0/85.0 | 61.0/79.0 | 26.0/74.0 | NA | 79.0/82.0 | 41.0/74.0 | 11.0/74.0 | NA | 13 | 1 | (32) |

| Sung et al,

2017 | 89 | 67 | NA | NA | 63.0/78.0 | 43.0/75.0 | NA | NA | 57.0/88.0 | 37.0/86.0 | 50 | 8 | (33) |

| Hsueh et al,

2016 | 184 | 65 | 94.9/96.9 | 82.2/86.7 | 71.4/76.4 | NA | 81.2/92.2 | 58.4/80.9 | 46.6/70.5 | NA | NA | NA | (17) |

| Lee et al,

2010 | 82 | 48 | 87.7/85.1 | 74.9/78.1 | 58.4/78.1 | NA | 74.3/91.5 | 59.3/89.1 | 57.4/89.1 | NA | NA | NA | (34) |

| Shabahang et

al, 2002 | 44 | 65 | NA | 57.0/66.0 | NA | NA | NA | 36.0/66.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | (35) |

| Chapman et

al, 2015 | 248 | 496 | NA | NA | 52.8/74.3 | 21.7/53.7 | NA | NA | 30.1/71.8 | 11.7/53.4 | NA | NA | (36) |

| Koniaris et

al, 2011 | 33 | 205 | 94.0/87.0 | NA | 59.0/63.0 | NA | 94.0/84.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (37) |

| Sotiropoulos et

al, 2009 | 26 | 26 | NA | NA | 26.0/56.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (38) |

| Shah et al,

2007 | 121 | 140 | 89.0/90.0 | 70.0/75.0 | 56.0/64.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 53 | 17 | (39) |

| Fan et al,

2011 | 287 | 50 | 93.4/92.0 | 82.1/86.0 | 72.8/81.0 | NA | 77.4/92.0 | 59.5/83.0 | 54.7/83.0 | NA | 135 | 5 | (40) |

| Del Gaudio et

al, 2008 | 80 | 147 | 90.0/90.0 | NA | 66.0/73.0 | NA | 72.0/85.0 | NA | 41.0/71.0 | NA | 7 | 1 | (41) |

| Adam et al,

2012 | 97 | 101 | NA | 67.0/79.0 | 52.0/75.0 | 36.0/65.0 | NA | 33.0/76.0 | 20.0/72.0 | 12.0/64.0 | 60 | 10 | (42) |

| Llovet et

al, 1999 | 77 | 87 | NA | 85.0/82.0 | 62.0/69.0 | 51.0/69.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (43) |

| Xia et al,

2021 | 285 | 90 | 96.3/95.4 | 87.1/79.4 | 76.9/77.4 | 54.7/71.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 136 | 13 | (44) |

| Yu et al,

2014 | 227 | 36 | 96.9/100 | 83.8/87.5 | 76.1/83.1 | NA | 80.6/91.7 | 59.8/85.3 | 50.8/81.0 | NA | 100 | 6 | (45) |

| Huang et al,

2014 | 55 | 33 | 87.3/90.9 | 69.3/87.7 | 57.3/70.1 | NA | 71.0/96.7 | 52.6/85.3 | 40.6/64.6 | NA | 29 | 6 | (46) |

| Xu et al,

2013 | 31 | 22 | 87.0/86.0 | 71.0/68.0 | NA | NA | 84.0/77.0 | 74.0/59.0 | NA | NA | 7 | 5 | (47) |

| Xia et al,

2012 | 89 | 32 | 86.0/87.0 | 63.0/70.0 | 44.0/62.0 | NA | 68.0/80.0 | 44.0/65.0 | 26.0/52.0 | NA | NA | NA | (48) |

| Zhu et al,

2011 | 65 | 66 | 92.3/93.9 | 67.7/87.9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 4 | (49) |

| Table II.Characteristics of the included

studies. |

Table II.

Characteristics of the included

studies.

| First author,

year | Region | Transplant

centers | ITT | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Margarit et

al, 2005 | Spain | Single | No | (19) |

| Jiang et al,

2014 | China | Single | No | (15) |

| Foltys et

al, 2014 | USA | Single | Yes | (20) |

| Bigourdan et

al, 2003 | France | Single | No | (21) |

| Sogawa et

al, 2013 | USA | Single | Yes | (22) |

| Moon et al,

2007 | Korea | Single | No | (23) |

| Bellavance et

al, 2008 | USA | Multiple | Yes | (24) |

| Squires et

al, 2014 | USA | Single | No | (25) |

| Michelakos et

al, 2019 | USA | Single | Yes | (18) |

| Meyerovich et

al, 2019 | Israel | Single | Yes | (26) |

| Krenzien et

al, 2018a | Germany | Single | No | (27) |

| Krenzien et

al, 2018b | Germany | Single | No | (27) |

| Park et al,

2017 | Korea | Single | No | (14) |

| Li et al,

2017 | China | Single | No | (16) |

| Huang et al,

2016 | China | Multiple | No | (28) |

| Li et al,

2014 | China | Single | No | (29) |

| Dai et al,

2014 | China | Single | No | (30) |

| Poon et al,

2007 | China | Single | No | (31) |

| Baccarani et

al, 2008 | Italy | Single | Yes | (32) |

| Sung et al,

2017 | Korea | Single | No | (33) |

| Hsueh et al,

2016 | China | Multiple | No | (17) |

| Lee et al,

2010 | Korea | Single | No | (34) |

| Shabahang et

al, 2002 | USA | Single | No | (35) |

| Chapman et

al, 2015 | USA | Multiple | No | (36) |

| Koniaris et

al, 2011 | USA | Multiple | Yes | (37) |

| Sotiropoulos et

al, 2009 | Germany | Single | No | (38) |

| Shah et al,

2007 | Canada | Single | Yes | (39) |

| Fan et al,

2011 | China | Single | No | (40) |

| Del Gaudio et

al, 2008 | Italy | Single | Yes | (41) |

| Adam et al,

2012 | France | Single | Yes | (42) |

| Llovet et

al, 1999 | Spain | Single | Yes | (43) |

| Xia et al,

2021 | China | Single | No | (44) |

| Yu et al,

2014 | China | Single | No | (45) |

| Huang et al,

2014 | China | Single | No | (46) |

| Xu et al,

2013 | China | Single | No | (47) |

| Xia et al,

2012 | China | Single | No | (48) |

| Zhu et al,

2011 | China | Multiple | No | (49) |

| Table III.Quality assessment results

(Newcastle-Ottawa Scale). |

Table III.

Quality assessment results

(Newcastle-Ottawa Scale).

|

| Selection | Comparability |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

| Outcome |

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Representation of

the exposed cohort | Selection of the

non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of

exposure | Demonstration that

outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Study controls to

select the most key factor | Study controls for

any additional factor |

|

|

|

|---|

| Assessment of

outcome | Whether follow-up

was long enough for outcomes to occur | Integrity of

follow-up | Score | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Margarit et

al, 2005 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | / | 8 | (19) |

| Jiang et al,

2014 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9 | (15) |

| Foltys et

al, 2014 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | 8 | (20) |

| Bigourdan et

al, 2003 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | 8 | (21) |

| Sogawa et

al, 2013 | * | * | * | * | / | / | * | * | * | 7 | (22) |

| Moon et al,

2007 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9 | (23) |

| Bellavance et

al, 2008 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | / | 7 | (24) |

| Squires et

al, 2014 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | / | 7 | (25) |

| Michelakos et

al, 2019 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | / | 7 | (18) |

| Meyerovich et

al, 2019 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | / | 7 | (26) |

| Krenzien et

al, 2018 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | 8 | (27) |

| Park et al,

2017 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | / | * | 7 | (14) |

| Li et al,

2017 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | * | 8 | (16) |

| Baccarani et

al, 2008 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | / | 7 | (32) |

| Huang et al,

2016 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | * | 8 | (28) |

| Li et al,

2014 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | 8 | (29) |

| Dai et al,

2014 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9 | (30) |

| Poon et al,

2007 | * | * | * | * | / | / | * | * | * | 7 | (31) |

| Sung et al,

2017 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | 8 | (33) |

| Hsueh et al,

2016 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | / | 7 | (17) |

| Lee et al,

2010 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | / | 8 | (34) |

| Shabahang et

al, 2002 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | / | * | 7 | (35) |

| Chapman et

al, 2015 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | / | 7 | (36) |

| Koniaris et

al, 2011 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | / | 8 | (37) |

| Sotiropoulos et

al, 2009 | * | * | * | * | / | / | * | * | * | 7 | (38) |

| Shah et al,

2007 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | / | 7 | (39) |

| Fan et al,

2011 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | 8 | (40) |

| Adam et al,

2012 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | * | 8 | (42) |

| Del Gaudio et

al, 2008 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | / | 7 | (41) |

| Llovet et

al, 1999 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | * | 8 | (43) |

| Xia et al,

2021 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | * | 8 | (44) |

| Yu et al,

2014 | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | 8 | (45) |

| Huang et al,

2014 | * | * | * | * | / | * | * | * | / | 7 | (46) |

| Xu et al,

2013 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | / | * | 8 | (47) |

| Xia et al,

2012 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9 | (48) |

| Zhu et al,

2011 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | / | / | 7 | (49) |

| Table IV.Basic characteristics of patients

with hepatocellular carcinoma. |

Table IV.

Basic characteristics of patients

with hepatocellular carcinoma.

|

| Sex | Child-Pugh

score |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

| LR | LT | LR | LT | MVI | Follow-up,

monthsa |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Male | Female | Male | Female | A | B | C | A | B | C | LR | LT | LR | LT | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Adam et al,

2012 | 84 | 13 | 85 | 16 | 80 | 10 | 1 | 19 | 45 | 37 | NA | NA | 36 | 83 | (42) |

| Baccarani et

al, 2008 | 28 | 10 | 42 | 6 | 28 | 10 | 0 | 19 | 20 | 8 | 29 | 8 | 36±25 | 28±26 | (32) |

| Bellavance et

al, 2008 | 203 | 42 | 110 | 24 | 233 | 12 | 0 | 75 | 59 | 0 | 60 | 11 | 27.60 | 39.60 | (24) |

| Bigourdan et

al, 2003 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 55 | 55 | (21) |

| Chapman et

al, 2015 | 170 | 78 | 372 | 124 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (36) |

| Dai et al,

2014 | 22 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | NA | NA | (30) |

| Del Gaudio et

al, 2008 | 63 | 17 | 126 | 21 | 66 | 14 | 0 | 66 | 53 | 88 | NA | NA | NA | NA | (41) |

| Fan et al,

2011 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (40) |

| Foltys et

al, 2014 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 30 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 22.30 | 47.50 | (20) |

| Hsueh et al,

2016 | 139 | 45 | 49 | 16 | 179 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 24 | 21 | 45 | 13 | NA | NA | (17) |

| Huang et al,

2016 | 227 | 29 | 43 | 8 | 241 | 15 | 0 | 23 | 15 | 13 | NA | NA | 62.40 | 30 | (28) |

| Jiang et al,

2014 | 28 | 5 | 29 | 5 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 10 | 31.40±15.50 | 43.50±22.10 | (15) |

| Koniaris et

al, 2011 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (37) |

| Krenzien et

al, 2018b | 18 | 12 | 101 | 22 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 | 89 | NA | NA | (27) |

| Krenzien et

al, 2018c | 21 | 8 | 72 | 19 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 11 | NA | NA | (27) |

| Lee et al,

2010 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 66.50 | 49.10 | (34) |

| Li et al,

2017 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 61 | 31 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (16) |

| Li et al,

2014 | 211 | 32 | 35 | 4 | 243 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 12 | 40.26±19.72 | 40.26±19.72 | (29) |

| Llovet et

al, 1999 | 48 | 29 | 65 | 22 | 74 | 3 | 0 | 37 | 38 | 12 | 11 | 22 | 32 | 26 | (43) |

| Margarit et

al, 2005 | 29 | 8 | 22 | 14 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 50 | 44 | (19) |

| Meyerovich et

al, 2019 | 21 | 9 | 37 | 17 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 4 | 27.70 | 23.30 | (26) |

| Michelakos et

al, 2019 | 74 | 21 | 76 | 13 | 95 | 0 | 0 | 89 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | (18) |

| Moon et al,

2007 | 78 | 22 | 16 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 22 | 77 | (23) |

| Park et al,

2017 | 150 | 49 | 107 | 30 | 194 | 5 | 0 | 32 | 60 | 45 | 47 | 21 | 28.70 | 37.80 | (14) |

| Poon et al,

2007 | 165 | 39 | 35 | 8 | 195 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 15 | 20 | 61 | 6 | 49 | 53 | (31) |

| Shabahang et

al, 2002 | 26 | 18 | 45 | 20 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (35) |

| Shah et al,

2007 | 56 | 65 | 76 | 64 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 25 | 22 | NA | 35 | (39) |

| Sogawa et

al, 2013 | 41 | 15 | 60 | 15 | 55 | 1 | 0 | 28 | 47 | 0 | 34 | 22 | 58.30 | 74.30 | (22) |

| Sotiropoulos et

al, 2009 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (38) |

| Squires et

al, 2014 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 39 | 6 | 0 | 37 | 75 | 19 | 14 | 33 | 45 | 40.20 | (25) |

| Sung et al,

2017 | 71 | 18 | 54 | 13 | 87 | 2 | 0 | 18 | 35 | 14 | 9 | 12 | NA | NA | (33) |

| Huang et al,

2014 | 51 | 4 | 28 | 5 | 49 | 6 | 0 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 7 | NA | NA | (46) |

| Xia et al,

2021 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (44) |

| Xia et al,

2012 | 80 | 9 | 26 | 6 | 89 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 8 | 37 | 37 | (48) |

| Xu et al,

2013 | 22 | 9 | 19 | 3 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0 | NA | NA | 35 | 35 | (47) |

| Yu et al,

2014 | 197 | 30 | 32 | 4 | 227 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 11 | 41.84±19.37 | 41.84±19.37 | (45) |

| Zhu et al,

2011 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | (49) |

| Table V.Comparisons of sex and Child-Pugh

scores calculated using the χ2 test. |

Table V.

Comparisons of sex and Child-Pugh

scores calculated using the χ2 test.

|

Characteristics | LR, n | LT, n | P-value |

|---|

| Sex

(male/female) | 2,323/639 | 1,774/501 | 0.697 |

| MVI (yes/no) | 531/1,378 | 328/1,063 | 0.006 |

| Child-Pugh

score |

|

|

|

| A | 2,507 | 752 | <0.001 |

| B | 128 | 507 |

|

| C | 1 | 285 |

|

Results of meta-analysis

OS rate analysis

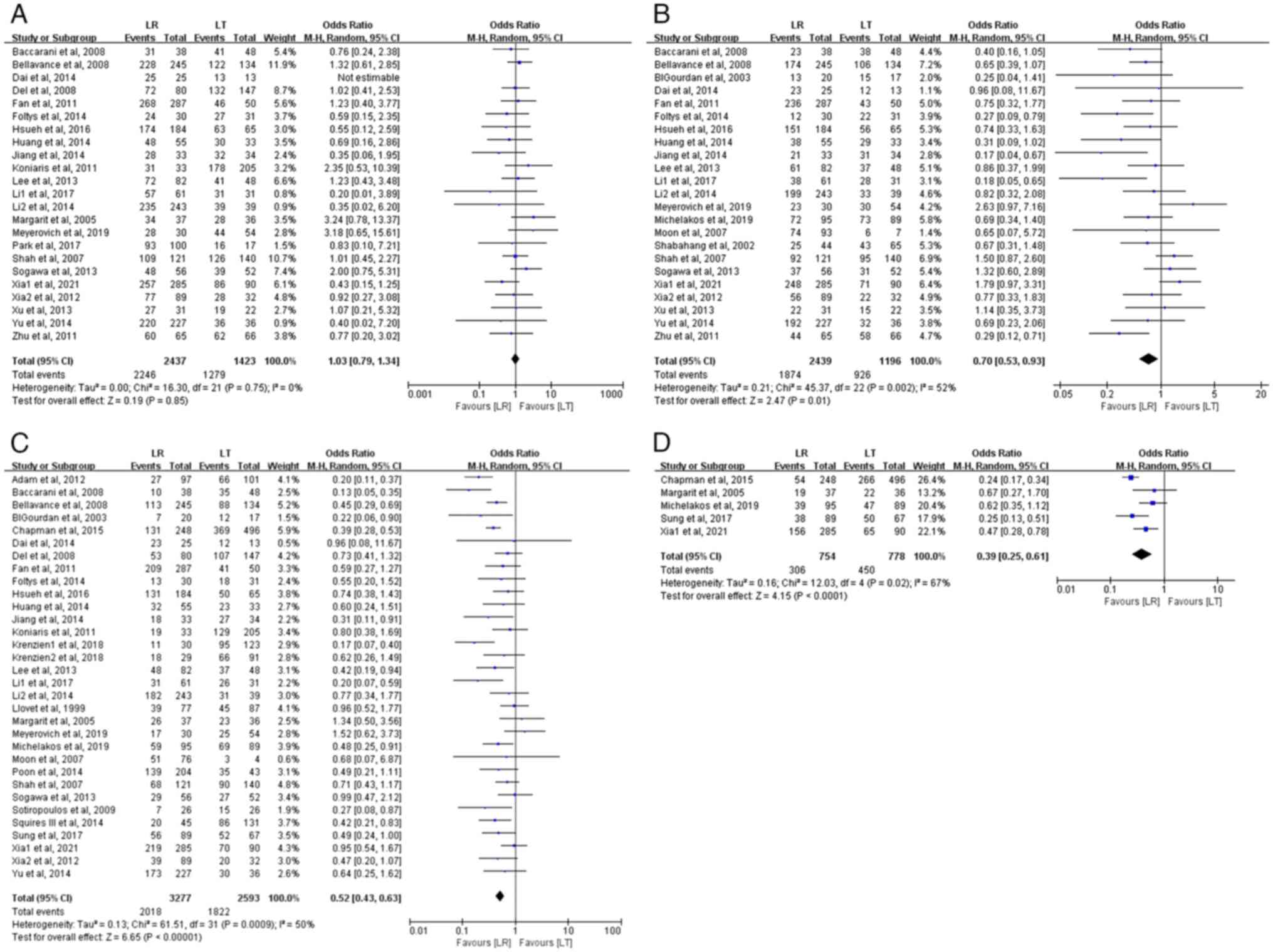

i) 1-year OS rate. In total, 23 studies assessed the

1-year OS rate, comprising 3,860 patients with HCC (2,437 in the LR

group and 1,423 in the LT group). The meta-analysis revealed no

significant difference in the 1-year OS rates between the LR and LT

groups, which were 92.2 and 89.9%, respectively (OR, 1.03; 95% CI,

0.79–1.34; P=0.85). No heterogeneity was observed among the studies

(P=0.75; I2=0%) (Fig.

2A).

ii) 3-year OS rate. In total, 23 studies evaluated

the 3-year OS rate, involving 3,635 patients with HCC (2,439 in the

LR group and 1,196 in the LT group). The meta-analysis demonstrated

a statistically significant difference in the 3-year OS rates

between the LR and LT groups, with patients with LT demonstrating a

slightly higher 3-year OS rate (77.4 vs. 76.8%) (OR, 0.70; 95% CI,

0.53–0.93; P=0.01). There was moderate heterogeneity among the

studies (P=0.002; I2=52%) (Fig. 2B).

iii) 5-year OS rate. In total, 32 studies assessed

the 5-year OS rate, involving 5,870 patients with HCC (3,277 in the

LR group and 2,593 in the LT group). The meta-analysis revealed a

significant difference in the 5-year OS rate between the two

groups, with the LT group having a higher 5-year OS rate (70.3 vs.

61.6%) (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.43–0.63; P<0.00001). There was

moderate heterogeneity among the studies (P=0.0009;

I2=50%) (Fig. 2C).

iv) 10-year OS rate. In total, 5 studies evaluated

the 10-year OS rate, involving 1,532 patients with HCC (754 in the

LR group and 778 in the LT group). The meta-analysis indicated a

significantly higher 10-year OS rate for the LT group compared with

that in the LR group (57.8 vs. 40.6%) (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.25–0.61;

P<0.0001). There was significant heterogeneity among the studies

(P=0.02; I2=67%) (Fig.

2D).

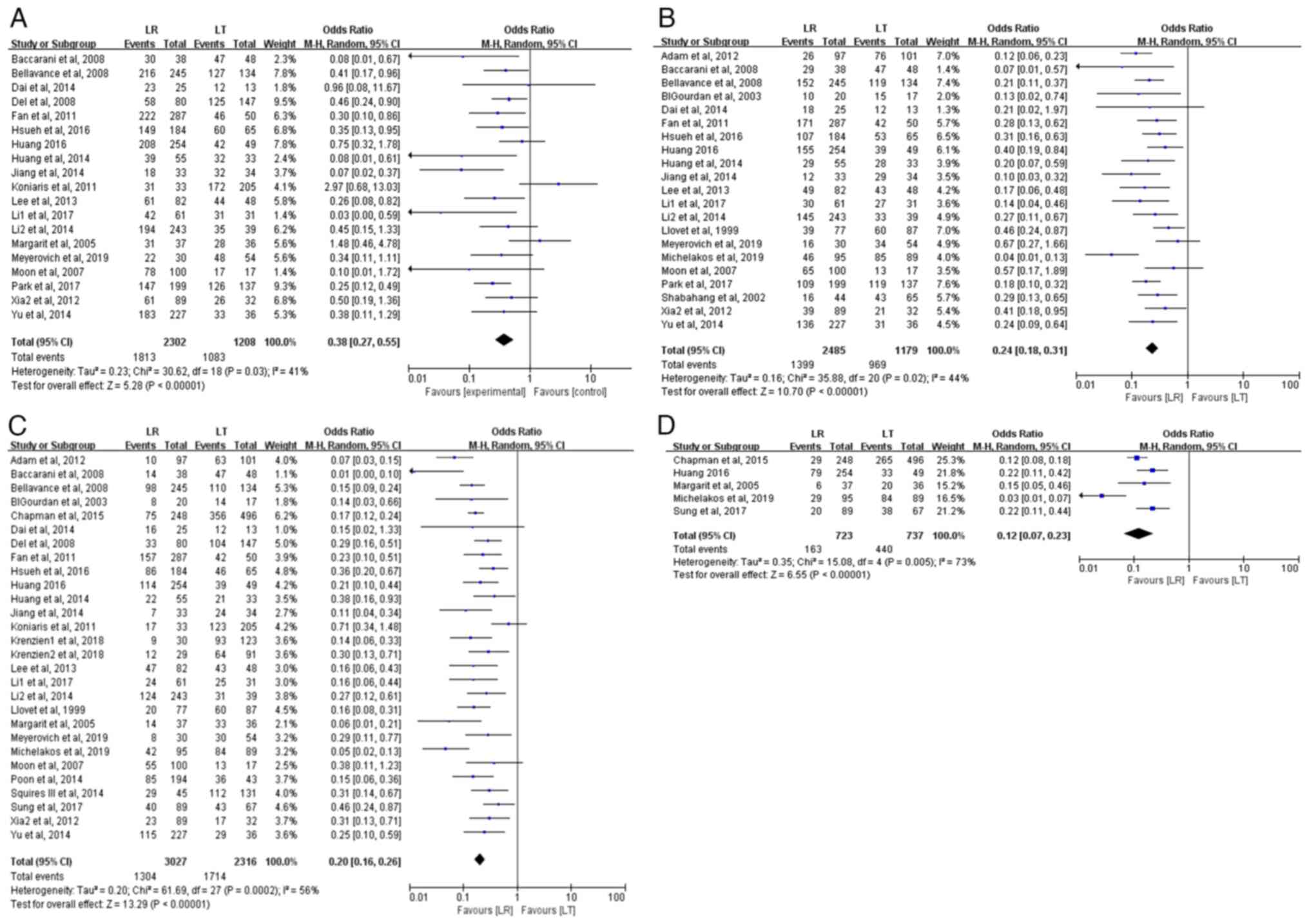

DFS rate analysis

i) 1-year DFS rate. In total, 19 studies evaluated

the 1-year DFS rate, including 3,510 patients with HCC (2,302 in

the LR group and 1,208 in the LT group). The meta-analysis revealed

that the 1-year DFS rate was significantly higher in the LT group

compared with the LR group (89.7 vs. 78.8%) for patients with HCC

meeting the Milan criteria (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.27–0.55;

P<0.00001). Statistical heterogeneity was present among the

studies (P=0.03; I2=41%) (Fig. 3A).

ii) 3-year DFS rate. In total, 21 studies assessed

the 3-year DFS rate, involving 3,664 patients with HCC (2,485 in

the LR group and 1,179 in the LT group). The meta-analysis

indicated a statistically significant difference in the 3-year DFS

rates between the LR and LT groups (OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.18–0.31;

P<0.00001), with the LT group exhibiting a significantly higher

3-year DFS rate (82.2 vs. 56.3%). Statistical heterogeneity was

present (P=0.02; I2=44%) (Fig. 3B).

iii) 5-year DFS rate. In total, 28 studies assessed

the 5-year DFS rate, comprising 5,343 patients with HCC (3,027 in

the LR group and 2,316 in the LT group). The meta-analysis

indicated a significant difference in the 5-year DFS rates between

the LR and LT groups (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.16–0.26; P<0.00001),

with the LT group demonstrating a considerably higher 5-year DFS

rate (74.0 vs. 43.1%). There was statistical heterogeneity among

the studies (P=0.0002; I2=56%) (Fig. 3C).

iv) 10-year DFS rate. In total, 5 studies evaluated

the 10-year DFS rate, including 1,460 patients with HCC (723 in the

LR group and 737 in the LT group). The meta-analysis demonstrated

that the 10-year DFS rate was significantly higher in the LT group

compared with that in the LR group (59.7 vs. 22.5%) (OR, 0.12; 95%

CI, 0.07–0.23; P<0.00001). There was high heterogeneity among

the studies (P=0.005; I2=73%) (Fig. 3D).

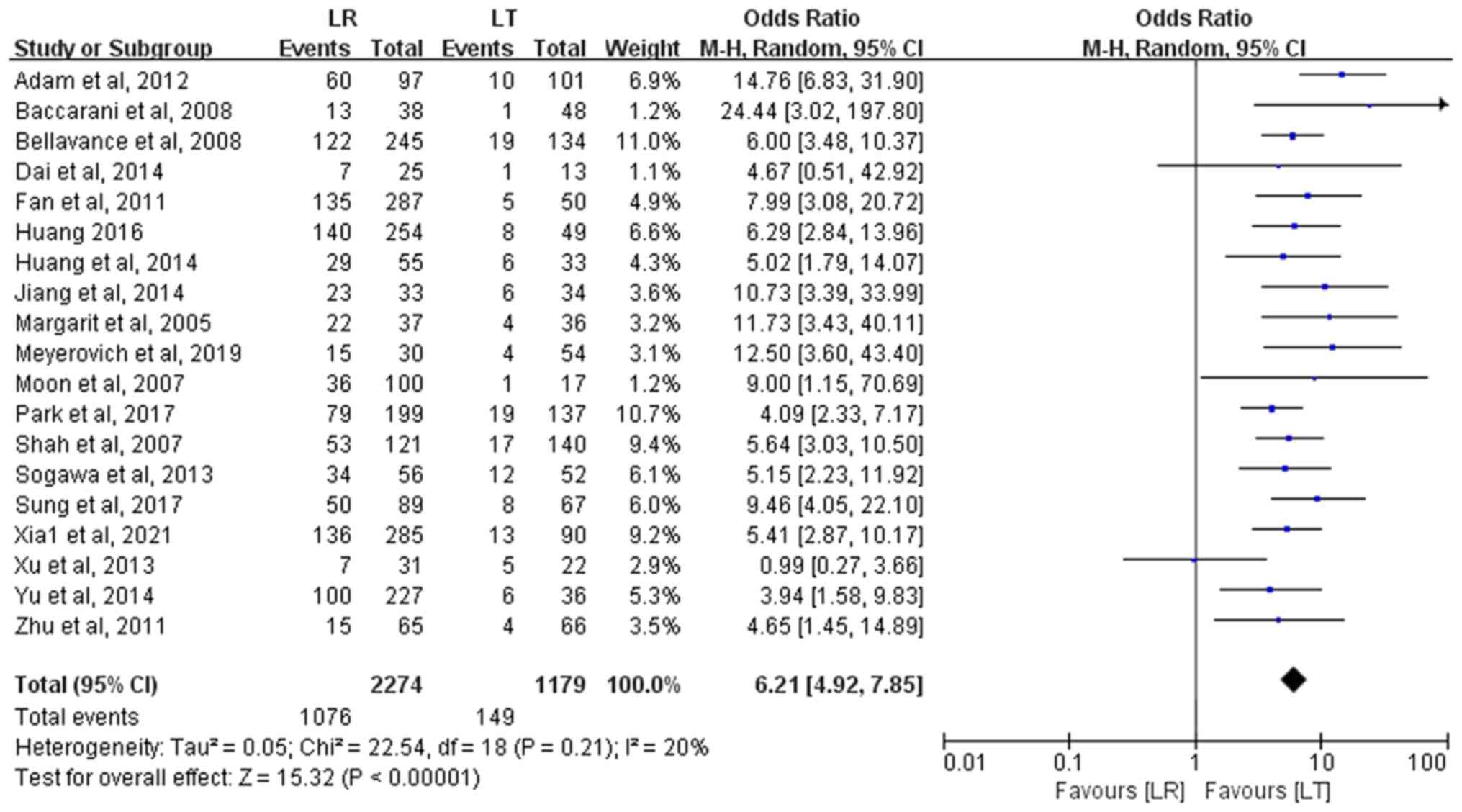

RR analysis

A total of 19 studies with 3,453 patients with HCC

(2,274 in the LR group and 1,179 in the LT group) assessed RR. The

meta-analysis revealed that the RR after LT was significantly lower

compared with that after LR (12.6 vs. 47.3%), with a statistically

significant difference (OR, 6.21; 95% CI, 4.92–7.85; P<0.00001).

No heterogeneity was observed among the studies (P=0.21;

I2=20%) (Fig. 4).

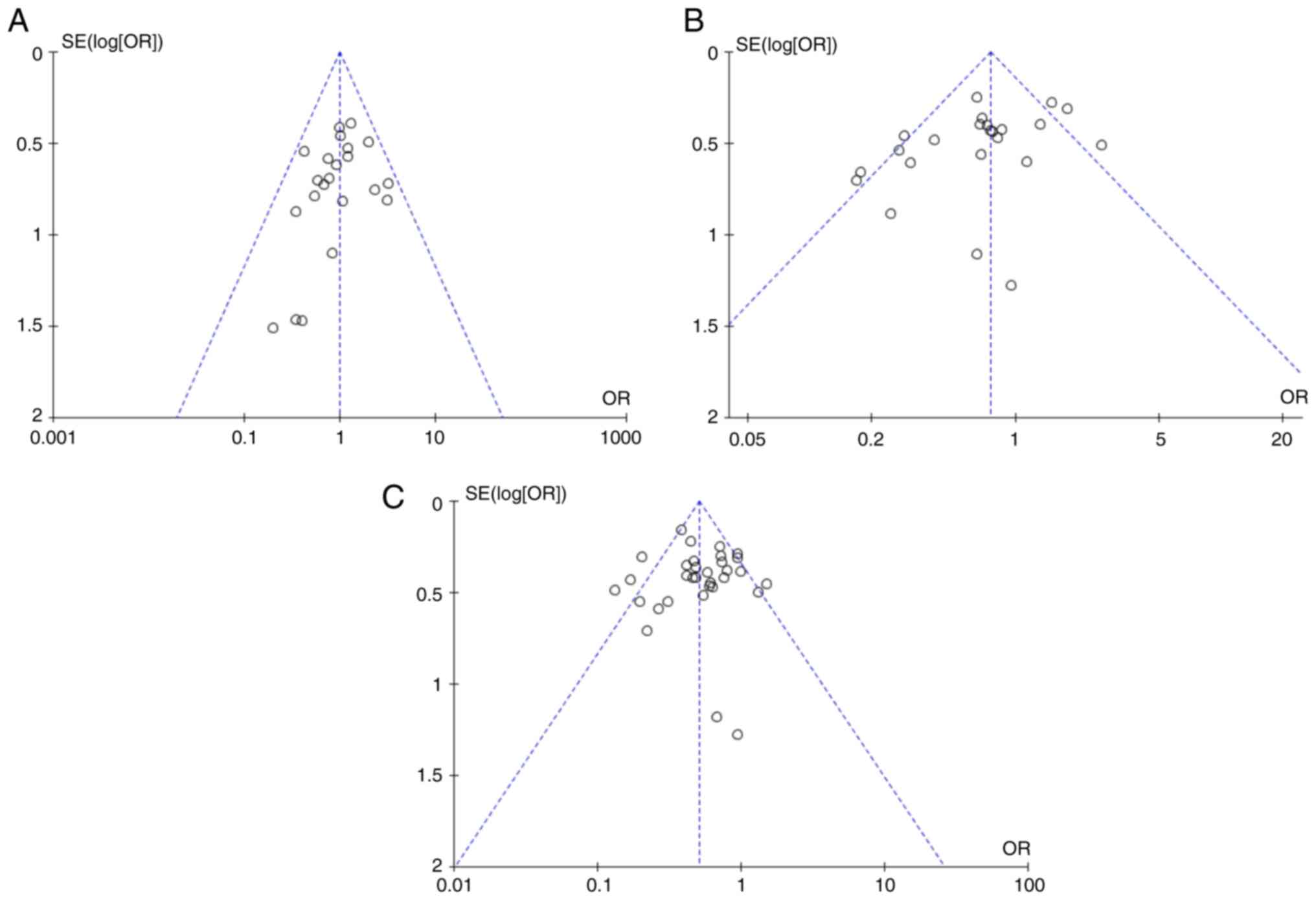

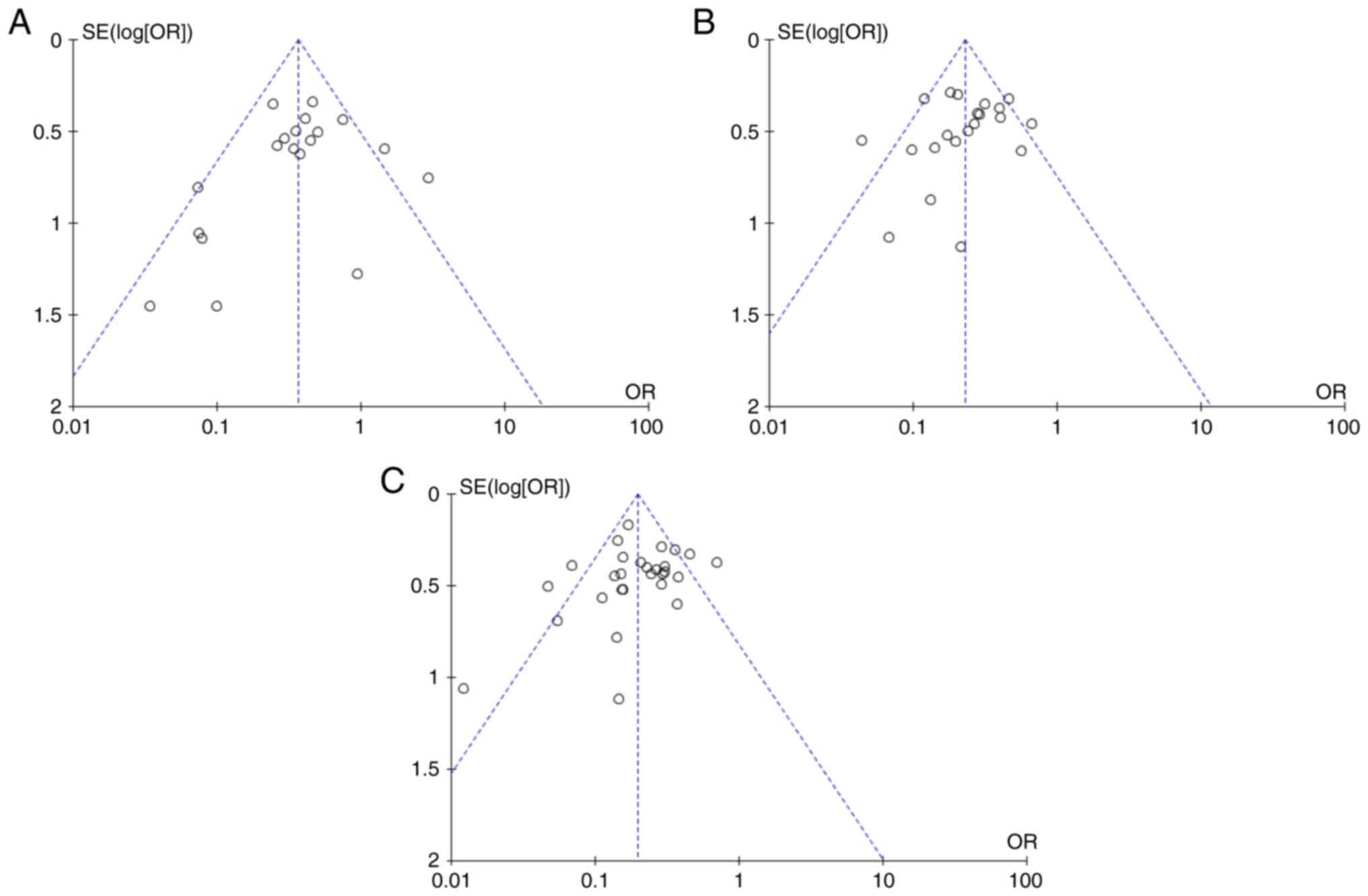

Sensitivity analysis and publication

bias

A sensitivity analysis was conducted by sequentially

excluding each study with high heterogeneity for outcome

indicators. The results revealed that the combined effect of the

outcome indicators did not change notably compared with the

previous analysis. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots

and all plots displayed varying degrees of asymmetry, indicating

potential publication bias (Figs. 5

and 6). These results reflected the

limitation of the present analysis due to the lack of published RCT

studies.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis compared the prognosis of

patients with HCC within the Milan criteria who received either LT

or LR. The results demonstrated no significant difference in the

1-year OS rate between the LR and LT groups. However, the LT group

demonstrated significantly higher 3-, 5- and 10-year OS rates

compared with the LR group. Similarly, the DFS rates were

consistently higher in the LT group at 1-, 3-, 5- and 10-year

intervals. The present study updates the literature on the

prognosis of patients with HCC within the Milan criteria undergoing

LT and LR, offering more precise information and clinical outcomes

for patients with early-stage HCC.

Varying degrees of heterogeneity were observed among

the studies included in the present meta-analysis. The studies by

Meyerovich et al (26) and

Xia et al (44) were notable

contributors to the high heterogeneity observed in the 3- and

5-year OS rates. A previous study by Meyerovich et al

(26), conducted in Israel,

reported a median waiting time of 304 days for LT, with a 24%

dropout rate, which suggested that LR provided a higher 5-year OS

rate compared with LT. This result contrasts with the present study

findings, possibly due to the lower organ donation rates in Israel,

which result in longer waiting times for LT. Shorter waiting times

might reduce dropout rates and improve post-transplant survival.

Similarly, Xia et al (44)

reported that the 3-year OS rate in the LT group was lower compared

with that in the LR group, although the difference was not

statistically significant. The heterogeneity in the 10-year OS rate

was primarily influenced by the study by Chapman et al

(36), which identified the type of

surgery as an independent risk factor for prognosis in multivariate

analysis. The present study, which retrospectively analyzed data

from five transplant centers, noted marked variation in surgical

approaches and its large sample size further contributed to the

observed heterogeneity in the 10-year OS rate.

The present analysis indicated that the 1-, 3-, 5-

and 10-year DFS rates were all significantly higher in the LT group

compared with those in the LR group for patients with HCC meeting

the Milan criteria. This finding is consistent with the report by

Michelakos et al (18),

which indicated that patients with LT had smaller maximum tumor

diameters and included more patients with T0 stage. By contrast,

Koniaris et al (37)

reported a higher 1-year DFS rate in the LR group compared with

that in the LT group, although the difference was not statistically

significant. This discrepancy may be attributed to the technical

challenges and complications arising from immunosuppressive therapy

in transplantation surgery. The recurrence of HCC within the first

year after LT may be influenced by several factors. First, despite

meeting the Milan criteria, certain tumors may exhibit high

invasiveness or micrometastasis that current diagnostic methods

(such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) cannot

detect prior to surgery (50).

Second, the use of immunosuppressants in LT recipients may impair

the immune system, creating an environment conducive to tumor

recurrence and growth. Furthermore, delayed postoperative follow-up

or failure to detect and treat recurrent tumors early could

increase the RR. A recently proposed deep learning model has

exhibited notable accuracy in the prediction of postoperative

recurrence compared with the Milan criteria and could potentially

identify high-risk subgroups, thereby improving recurrence

management after LT (51).

The present study included patients with HCC with

Child-Pugh B/C liver cirrhosis, revealing significant differences

in cirrhosis severity between the two groups. Most patients in the

LR group had Child-Pugh A liver function, whereas the LT group

predominantly consisted of patients with Child-Pugh B/C liver

function, a factor that may have contributed to the observed

heterogeneity. Cirrhosis severity serves a key role in the

prognosis of patients with HCC. For those with mild or

non-cirrhotic liver disease (Child-Pugh A), both LR and LT yield

favorable therapeutic outcomes. However, LT is typically

recommended for patients with moderate to severe cirrhosis.

The present study findings indicated that LT

resulted in significantly higher 1-, 3-, 5- and 10-year DFS rates

compared with LR for patients with HCC meeting the Milan criteria.

This may be attributed to the fact that LT addresses both the tumor

and the underlying liver disease (52). By contrast, residual liver tissue

following LR may harbor micrometastases, increasing the risk of

tumor recurrence or liver decompensation. While no significant

difference was found in the 1-year OS rate between LR and LT for

patients within the Milan criteria in the present study, LT

demonstrated improved 3-, 5- and 10-year OS outcomes. The minimal

difference in 1-year OS rate could be attributed to complications

such as acute graft rejection (53), infections due to immunosuppressants

and renal failure (54), rather

than the cancer itself. Long-term survival outcomes (3-, 5- and

10-year) were predominantly influenced by tumor recurrence. The

present analysis demonstrated that LT reduced RR by 29.2% compared

with LR, further supporting its long-term survival benefits. The

risk of death within 5 years post-LT in elderly patients was not

higher compared with that in younger patients and the OS rate in

elderly patients with LT was higher compared with those who

underwent LR. Thus, while elderly patients >70 may experience

decline in organ function, poor surgical tolerance, slower recovery

and coexisting chronic conditions, age alone should not exclude

patients from liver transplant consideration (55–57).

Due to factors such as organ shortage, liver donor

waiting times, hospitalization durations and associated costs,

certain studies have recommended LR as the initial treatment for

patients with HCC eligible for either LR or LT, with LT being

considered as a salvage method for tumor recurrence (58,59).

Several studies reported that the median hospitalization time for

patients with HCC undergoing LT was 9–14 days longer compared with

that for those patients who underwent LR (28,31).

Michelakos et al (18)

highlighted that the average cost of LT was markedly higher

compared with that of LR, considering the expenses associated with

preoperative bridging therapy and postoperative recurrence

management (18). Shah et al

(39) suggested that LT offers

improved survival outcomes compared with LR only if the waiting

time for a liver transplant is <4 months, as patients with HCC

may lose the opportunity for transplantation due to tumor

progression during the waiting period. However, certain studies

have noted that the prognosis of salvage LT after recurrence

post-resection is worse compared with that of primary LT, and the

risks associated with sequential LT following resection should be

carefully considered (60,61).

The present meta-analysis provided a comprehensive

evaluation of the prognostic outcomes of LT and LR for patients

with HCC within the Milan criteria, offering the latest reliable

data and insights key for guiding the selection of LT candidates in

liver cancer treatment. Nonetheless, several limitations should be

acknowledged. First, due to ethical considerations, all included

studies were retrospective, with no randomized controlled trials

available, preventing assessment of blinding and potentially

introducing selection bias. Second, most studies did not adequately

report loss-to-follow-up rates, limiting the ability to evaluate

attrition bias. Third, funnel plots indicated the presence of

publication bias, as studies with statistically significant

positive results were more likely to be published, which may have

influenced the present study findings. Lastly, relatively few

studies that had smaller sample sizes compared the 10-year OS and

DFS rates. These limitations present opportunities for future

research. To address these issues, strategies such as mandatory

clinical trial registration on public platforms before study

initiation, ensuring transparency, establishing cross-regional or

cross-institutional research networks to increase sample size and

improve generalizability, and utilizing propensity score matching

to correct for confounding factors could enhance the robustness and

applicability of future studies.

LT is the preferred treatment option for patients

with HCC within the Milan criteria. However, in clinical practice,

it faces multiple challenges across various dimensions.

Technically, the LT procedure is complex and demanding, which

requires a highly skilled and experienced surgical team to ensure

optimal patient outcomes. Economically, LT is associated with

notable costs, including high surgical expenses and the long-term

financial burden of immunosuppressive therapy. The severe shortage

of donor organs is a major limiting factor for the widespread

adoption of LT, and the lack of a global, comprehensive and

equitable organ allocation system further complicates the process

of securing suitable donors for patients. For example, in

Singapore, patients with liver cancer have to meet the University

of California San Francisco criteria (includes i) a single tumor

≤6.5 cm; ii) ≤3 lesions and maximum lesion diameter ≤4.5 cm,

cumulative diameter ≤8 cm; and iii) no intrahepatic vascular

infiltration or extrahepatic metastasis) to be eligible for the

deceased donor liver transplant waiting list, which makes donor

acquisition even more challenging (57). As a result, living donor LT has

emerged as a key strategy to address the shortage of deceased donor

organs (62).

Despite the benefits of LT, the 1-year OS rates

post-transplant are typically ~90%, with ~10% mortality rates

following both LT and LR. The high 1-year mortality rate after LR

can be predicted preoperatively by factors such as multinodularity,

Child-Pugh class and MVI (63).

Therefore, a comprehensive and accurate preoperative assessment of

patients with HCC is essential to guide the selection of the most

appropriate treatment. In certain cases, LT or LR may not be the

only viable options for treatment. Alternative approaches, such as

transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) combined with radiofrequency

ablation (RFA), may also offer curative outcomes. While the 3-year

and 5-year DFS rates are higher in the LR group compared with those

in the TACE + RFA group, no significant differences in the 1-, 3-

and 5-year OS rates have been observed (64). Therefore, TACE + RFA is also

considered a safe and effective treatment for early-stage HCC.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

LT provides significantly improved long-term OS and DFS rates, as

well as a lower RR, compared with LR for patients with HCC meeting

the Milan criteria. Therefore, LT is recommended as the preferred

initial treatment for these patients, provided that a suitable

liver donor is available. However, each case should be evaluated

through multidisciplinary consultations to optimize patient

outcomes while ensuring efficient use of limited donor resources.

Although this conclusion is based on a comprehensive analysis of

existing studies, clinical decisions must also consider specific

patient circumstances. A notable limitation of the Milan criteria

is its focus solely on tumor size and number, without incorporating

liver function and cirrhosis in a more holistic evaluation. In

cases of organ shortage, the degree of liver cirrhosis and liver

reserve function should guide the decision between LT and LR. This

approach would prioritize LR for patients with HCC with preserved

liver function. The development of a more refined, comprehensive

evaluation criteria for LT remains an area for future research.

Furthermore, with the rapid advancements in cancer-targeted

immunotherapy, the outcomes of LT and LR should be reassessed. It

remains to be determined whether the combination of surgical

resection and targeted immunotherapy can provide notably improved

or similar results to LT, how immunotherapy should be managed

post-LT and how HCC recurrence can be addressed after LT under

immunosuppressive therapy, all of which warrant further

investigation.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported in part by the International

Cooperation Fund of the Science and Technology Bureau of Jilin

Province (grant no. 20220402075GH), the Jilin Province Health

Research Talent Project (grant no. 2022SCZ06) and the NSFC Regional

Innovation and Development Fund (grant no. U20A20360).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JW and YW conducted database searching and data

analysis. JW wrote the manuscript. ZP conducted data analysis and

revised the manuscript. YY conducted database searching, and data

identification and analysis. WL participated in research design and

wrote the manuscript. JW and YW confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

DFS

|

disease-free survival

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

LR

|

liver resection

|

|

LT

|

liver transplantation

|

|

MVI

|

microvascular invasion

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

RR

|

recurrence rate

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Taefi A, Abrishami A, Nasseri-Moghaddam S,

Eghtesad B and Sherman M: Surgical resection versus liver

transplant for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 6:CD0069352013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Vibert E, Schwartz M and Olthoff KM:

Advances in resection and transplantation for hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Hepatol. 72:262–276. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Aufhauser DD Jr, Sadot E, Murken DR,

Eddinger K, Hoteit M, Abt PL, Goldberg DS, DeMatteo RP and Levine

MH: Incidence of occult intrahepatic metastasis in hepatocellular

carcinoma treated with transplantation corresponds to early

recurrence rates after partial hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 267:922–928.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bzeizi KI, Abdullah M, Vidyasagar K,

Alqahthani SA and Broering D: Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence

and mortality rate post liver transplantation: Meta-analysis and

systematic review of real-world evidence. Cancers (Basel).

14:51142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Klupp J, Kohler S, Pascher A and Neuhaus

P: Liver transplantation as ultimate tool to treat portal

hypertension. Dig Dis. 23:65–71. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola

S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A and

Gennari L: Liver transplantation for the treatment of small

hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med.

334:693–699. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Russo A and

Mazzaferro V: First-line treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma:

Resection or transplantation? Transplant Proc. 39:2271–2273. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

European Association for the Study of the

Liver, . EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 69:182–236. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sala M, Fuster J, Llovet JM, Navasa M,

Solé M, Varela M, Pons F, Rimola A, García-Valdecasas JC, Brú C, et

al: High pathological risk of recurrence after surgical resection

for hepatocellular carcinoma: An indication for salvage liver

transplantation. Liver Transpl. 10:1294–1300. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cherqui D, Laurent A, Mocellin N, Tayar C,

Luciani A, Van Nhieu JT, Decaens T, Hurtova M, Memeo R, Mallat A

and Duvoux C: Liver resection for transplantable hepatocellular

carcinoma: Long-term survival and role of secondary liver

transplantation. Ann Surg. 250:738–746. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL,

Pietroni MC and Williams R: Transection of the oesophagus for

bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 60:646–649. 1973.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R, Sowden AJ,

Sakarovitch C, Song F, Petticrew M and Altman DG; International

Stroke Trial Collaborative Group; European Carotid Surgery Trial

Collaborative Group, : Evaluating non-randomised intervention

studies. Health Technol Assess. 7:3–10. 1–173. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Park MS, Lee KW, Kim H, Choi YR, Hong G,

Yi NJ and Suh KS: Primary living-donor liver transplantation is not

the optimal treatment choice in patients with early hepatocellular

carcinoma with poor tumor biology. Transplant Proc. 49:1103–1108.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jiang L, Liao A, Wen T, Yan L, Li B and

Yang J: Living donor liver transplantation or resection for

Child-Pugh A hepatocellular carcinoma patients with multiple

nodules meeting the Milan criteria. Transpl Int. 27:562–569. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li C, Liu JY, Peng W, Wen TF, Yan LN, Yang

JY, Li B, Wang WT and Xu MQ: Liver resection versus transplantation

for multiple hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score analysis.

Oncotarget. 8:81492–81500. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hsueh KC, Lee TY, Kor CT, Chen TM, Chang

TM, Yang SF and Hsieh CB: The role of liver transplantation or

resection for patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour

Biol. 37:4193–4201. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Michelakos T, Xourafas D, Qadan M,

Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Cai L, Patel MS, Adler JT, Fontan F, Basit U,

Vagefi PA, et al: Hepatocellular carcinoma in transplantable

Child-Pugh A cirrhotics: Should cost affect resection vs

transplantation? J Gastrointest Surg. 23:1135–1142. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Margarit C, Escartín A, Castells L, Vargas

V, Allende E and Bilbao I: Resection for hepatocellular carcinoma

is a good option in Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A patients with

cirrhosis who are eligible for liver transplantation. Liver

Transpl. 11:1242–1251. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Foltys D, Zimmermann T, Kaths M, Strempel

M, Heise M, Hoppe-Lotichius M, Weiler N, Scheuermann U, Ruckes C,

Hansen T, et al: Hepatocellular carcinoma in Child's A cirrhosis: A

retrospective analysis of matched pairs following liver

transplantation vs liver resection according to the

intention-to-treat principle. Clin Transplant. 28:37–46. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bigourdan JM, Jaeck D, Meyer N, Meyer C,

Oussoultzoglou E, Bachellier P, Weber JC, Audet M, Doffoël M and

Wolf P: Small hepatocellular carcinoma in Child A cirrhotic

patients: Hepatic resection versus transplantation. Liver Transpl.

9:513–520. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sogawa H, Shrager B, Jibara G, Tabrizian

P, Roayaie S and Schwartz M: Resection or transplant-listing for

solitary hepatitis C-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: An

intention-to-treat analysis. HPB (Oxford). 15:134–141. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Moon DB, Lee SG and Hwang S: Liver

transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Single nodule with

Child-Pugh class A sized less than 3 cm. Dig Dis. 25:320–328. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bellavance EC, Lumpkins KM, Mentha G,

Marques HP, Capussotti L, Pulitano C, Majno P, Mira P,

Rubbia-Brandt L, Ferrero A, et al: Surgical management of

early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: Resection or transplantation?

J Gastrointest Surg. 12:1699–1708. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Squires MH III, Hanish SI, Fisher SB,

Garrett C, Kooby DA, Sarmiento JM, Cardona K, Adams AB, Russell MC,

Magliocca JF, et al: Transplant versus resection for the management

of hepatocellular carcinoma meeting Milan Criteria in the MELD

exception era at a single institution in a UNOS region with short

wait times. J Surg Oncol. 109:533–541. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Meyerovich G, Goykhman Y, Nakache R,

Nachmany I, Lahat G, Shibolet O, Menachem Y, Katchman H, Wolf I,

Geva R, et al: Resection vs transplant listing for hepatocellular

carcinoma: An intention-to-treat analysis. Transplant Proc.

51:1867–1873. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Krenzien F, Schmelzle M, Struecker B,

Raschzok N, Benzing C, Jara M, Bahra M, Öllinger R, Sauer IM,

Pascher A, et al: Liver transplantation and liver resection for

cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Comparison of

long-term survivals. J Gastrointest Surg. 22:840–848. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Huang ZY, Liang BY, Xiong M, Dong KS,

Zhang ZY, Zhang EL, Li CH and Chen XP: Severity of cirrhosis should

determine the operative modality for patients with early

hepatocellular carcinoma and compensated liver function. Surgery.

159:621–631. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li C, Zhu WJ, Wen TF, Dai Y, Yan LN, Li B,

Yang JY, Wang WT and Xu MQ: Child-Pugh A hepatitis B-related

cirrhotic patients with a single hepatocellular carcinoma up to 5

cm: Liver transplantation vs resection. J Gastrointest Surg.

18:1469–1476. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Dai Y, Li C, Wen TF and Yan LN: Comparison

of liver resection and transplantation for Child-pugh A cirrhotic

patient with very early hepatocellular carcinoma and portal

hypertension. Pak J Med Sci. 30:996–1000. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Poon RTP, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL and Wong

J: Difference in tumor invasiveness in cirrhotic patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma fulfilling the Milan criteria treated by

resection and transplantation: Impact on long-term survival. Ann

Surg. 245:51–58. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Baccarani U, Isola M, Adani GL, Benzoni E,

Avellini C, Lorenzin D, Bresadola F, Uzzau A, Risaliti A, Beltrami

AP, et al: Superiority of transplantation versus resection for the

treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Transpl Int.

21:247–254. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sung PS, Yanf H, Na GH, Hwang S, Kang D,

Jang JW, Bae SH, Choi JY, Kim DG, Yoon SK and You YK: Long-term

outcome of liver resection versus transplantation for

hepatocellular carcinoma in a region where living donation is a

main source. Ann Transplant. 22:276–284. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lee KK, Kim DG, Moon IS, Lee MD and Park

JH: Liver transplantation versus liver resection for the treatment

of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 101:47–53. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Shabahang M, Franceschi D, Yamashiki N,

Reddy R, Pappas PA, Aviles K, Flores S, Chaparro A, Levi JU,

Sleeman D, et al: Comparison of hepatic resection and hepatic

transplantation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma among

cirrhotic patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 9:881–886. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chapman WC, Klintmalm G, Hemming A,

Vachharajani N, Majella Doyle MB, DeMatteo R, Zaydfudim V, Chung H,

Cavaness K, Goldstein R, et al: Surgical treatment of

hepatocellular carcinoma in North America: Can hepatic resection

still be justified? J Am Coll Surg. 220:628–637. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Koniaris LG, Levi DM, Pedroso FE,

Franceschi D, Tzakis AG, Santamaria-Barria JA, Tang J, Anderson M,

Misra S, Solomon NL, et al: Is surgical resection superior to

transplantation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma? Ann

Surg. 254:527–538. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Sotiropoulos GC, Drühe N, Sgourakis G,

Molmenti EP, Beckebaum S, Baba HA, Antoch G, Hilgard P, Radtke A,

Saner FH, et al: Liver transplantation, liver resection, and

transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma in

cirrhosis: Which is the best oncological approach? Dig Dis Sci.

54:2264–2273. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shah SA, Cleary SP, Tan JC, Wei AC,

Gallinger S, Grant DR and Greig PD: An analysis of resection vs

transplantation for early hepatocellular carcinoma: Defining the

optimal therapy at a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol.

14:2608–2614. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Fan ST, Poon RT, Yeung C, Lam CM, Lo CM,

Yuen WK, Ng KK, Liu CL and Chan SC: Outcome after partial

hepatectomy for hepatocellular cancer within the Milan criteria. Br

J Surg. 98:1292–1300. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Del Gaudio M, Ercolani G, Ravaioli M,

Cescon M, Lauro A, Vivarelli M, Zanello M, Cucchetti A, Vetrone G,

Tuci F, et al: Liver transplantation for recurrent hepatocellular

carcinoma on cirrhosis after liver resection: University of Bologna

experience. Am J Transplant. 8:1177–1185. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Adam R, Bhangui P, Vibert E, Azoulay D,

Pelletier G, Duclos-Vallée JC, Samuel D, Guettier C and Castaing D:

Resection or transplantation for early hepatocellular carcinoma in

a cirrhotic liver: Does size define the best oncological strategy?

Ann Surg. 256:883–891. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Llovet JM, Fuster J and Bruix J:

Intention-to-treat analysis of surgical treatment for early

hepatocellular carcinoma: Resection versus transplantation.

Hepatology. 30:1434–1440. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xia YX, Zhang F, Li XC, Kong LB, Zhang H,

Li DH, Cheng F, Pu LY, Zhang CY, Qian XF, et al: Surgical treatment

of primary liver cancer: A report of 10 966 cases. Zhonghua Wai Ke

Za Zhi. 59:6–17. 2021.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yu Y, Li C and Wen T: Child-Pugh A Class

cirrhotic patients with a single hepatocellular carcinoma up to 5

cm in diameter: Liver transplantation versus resection. Chin J

Bases Clin General Surg. 21:406–409. 2014.(In Chinese).

|

|

46

|

Huang JH and Zhou J: Factors for

predicting outcomes of liver transplantation and liver resection

for hepatocellular carcinoma meeting Milan criteria. J South Med

Univ. 34:406–409. 2014.

|

|

47

|

Xu XS, Qu K, Zhou L, Song YZ, Zhang YL and

Liu C: Selection of surgical procedure in the treatment of early

hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin J Hepat Surg (Electronic Edition).

2:80–85. 2013.

|

|

48

|

Xia Y, Jiang Y, Cai Q, Pan F, Zhang X and

Lü L: Comparison of efficacies of hepatectomy and liver

transplantion for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma fulfilling

the Milan criteria. Chin J Dig Surg. 11:526–529. 2012.(In

Chinese).

|

|

49

|

Zhu X, He X, Chen M, Yuan Y and Cui S: A

multi-center comparative study of the effectiveness of three

radical therapies on hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin J Hepatobiliary

Surg. 17:372–375. 2011.(In Chinese).

|

|

50

|

Singal AG, Llovet JM, Yarchoan M, Mehta N,

Heimbach JK, Dawson LA, Jou JH, Kulik LM, Agopian VG, Marrero JA,

et al: AASLD practice guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and

treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 78:1922–1965.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ko SH, Cao J, Yang YK, Xi ZF, Han HW, Sha

M and Xia Q: Development of a deep learning model for predicting

recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation.

Front Med (Lausanne). 11:13730052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Clavien PA, Lesurtel M, Bossuyt PM, Gores

GJ, Langer B and Perrier A; OLT for HCC Consensus Group, :

Recommendations for liver transplantation for hepatocellular

carcinoma: An international consensus conference report. Lancet

Oncol. 13:e11–e22. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Matinlauri IH, Nurminen MM, HÖckerstedt KA

and Isoniemi HM: Changes in liver graft rejections over time.

Transplant Proc. 38:2663–2666. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Tinti F, Umbro I, Giannelli V, Merli M,

Ginanni Corradini S, Rossi M, Nofroni I, Poli L, Berloco PB and

Mitterhofer AP: Acute renal failure in liver transplant recipients:

Role of pretransplantation renal function and 1-year follow-up.

Transplant Proc. 43:1136–1138. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

European Association for the Study of the

Liver, . Electronic address: simpleeasloffice@easloffice.eu.

EASL clinical practice guidelines: Liver transplantation. J

Hepatol. 64:433–485. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Mousa OY, Nguyen JH, Ma Y, Rawal B, Musto

KR, Dougherty MK, Shalev JA and Harnois DM: Evolving role of liver

transplantation in elderly recipients. Liver Transpl. 25:1363–1374.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Chow PKH, Choo SP, Ng DCE, Lo RH, Wang ML,

Toh HC, Tai DW, Goh BK, Wong JS, Tay KH, et al: National cancer

centre singapore consensus guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Liver Cancer. 5:97–106. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Chan DL, Alzahrani NA, Morris DL and Chua

TC: Systematic review of efficacy and outcomes of salvage liver

transplantation after primary hepatic resection for hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 29:31–41. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

De Carlis L, Di Sandro S, Giacomoni A,

Mangoni I, Lauterio A, Mihaylov P, Cusumano C and Rampoldi A: Liver

transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver

resection: Why deny this chance of cure? J Clin Gastroenterol.

47:352–358. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zheng Z, Liang W, Milgrom DP, Zheng Z,

Schroder PM, Kong NS, Yang C, Guo Z and He X: Liver transplantation

versus liver resection in the treatment of hepatocellular

carcinoma: A meta-analysis of observational studies.

Transplantation. 97:227–234. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Adam R, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Eshkenazy

R, Pascal G, Hashizume K, Samuel D and Bismuth H: Liver resection

as a bridge to transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma on

cirrhosis: A reasonable strategy? Ann Surg. 238:508–519. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Goldaracena N and Barbas AS: Living donor

liver transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 24:131–137.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Sheriff S, Madhavan S, Lei GY, Chan YH,

Junnarkar SP, Huey CW, Low JK and Shelat VG: Predictors of

mortality within the first year post-hepatectomy for hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 34:142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Gui CH, Baey S, D'cruz RT and Shelat VG:

Trans-arterial chemoembolization + radiofrequency ablation versus

surgical resection in hepatocellular carcinoma-A meta-analysis. Eur

J Surg Oncol. 46:763–771. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|