Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of

cancer-associated mortalities globally, with 2.48 million novel

cases and 1.81 million mortalities, recorded in 2022. A model

projection released by the International Agency for Research on

Cancer under the World Health Organization indicates that new cases

of lung cancer will increase by 41% by the year 2050, primarily

driven by population aging in China and India. Notably, the

nationwide low-dose computed tomography (CT) screening initiative

in China has increased the number of cases of early-stage diagnosis

by ~12% since 2023 (1–3).

Epidemiological data from 19 countries has revealed

that non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 90.3% of all

cases of lung cancer (4). Although

surgical resection remains the main curative approach for

early-stage and resectable locally advanced NSCLC, postoperative

5-year survival rates remain suboptimal: These have been reported

to be 68% for stage IB and 36% for stage IIIA disease, respectively

(5). Although traditional adjuvant

chemotherapy has been reported to modestly reduce the risk of

recurrence, its clinical benefits appear to have reached a plateau,

since only a 5% improvement in 5-year survival rates has been

recorded (6), with additional

limitations including chemotherapy-associated toxicity and the

absence of validated predictive biomarkers. Notably, 30–55% of

patients experience locoregional recurrence or distant metastasis

postoperatively (7), underscoring

the key need for effective eradication of minimal residual disease

(MRD) and the activation of systemic immune surveillance to improve

outcomes.

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)

targeting programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1)/programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) has revolutionized treatment paradigms for

advanced NSCLC (8). Key phase III

trials, including KEYNOTE-024 and CheckMate 227 (9,10),

have demonstrated notable overall survival (OS) benefits with ICI

monotherapy or combination regimens in metastatic settings. These

breakthroughs have prompted an investigation of immunotherapy in

different perioperative settings, aiming to remodel the tumor

immune microenvironment through neoadjuvant or adjuvant approaches

to achieve synergistic locoregional-systemic control.

Early exploratory studies, such as the LCMC3 and

CheckMate 159 studies (11,12), were able to establish the

feasibility of neoadjuvant immunotherapy. The landmark CheckMate

816 trial first demonstrated in a phase III setting that the use of

the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab plus chemotherapy led to a

marked improvement in both the pathological complete response (pCR)

rates and event-free survival (EFS) rates compared with

chemotherapy alone in resectable NSCLC, marking the transition of

perioperative immunotherapy from the conceptual stage to clinical

practice (13).

Subsequent trials, including the KEYNOTE-671

(14) and AEGEAN (15) trials, further advanced combination

strategies, achieving pCR rates >30% and demonstrating durable

survival benefits with postoperative adjuvant immunotherapy.

Similar progress in adjuvant immunotherapy has emerged from the

IMpower010 trial, where treatment with atezolizumab led to an

improved 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate (increased to 60%)

compared with chemotherapy in PD-L1+ (≥1%) patients with

stage II–IIIA cancer (16), whereas

the KEYNOTE-091 trial established a DFS benefit for pembrolizumab

in PD-L1-unselected cases. These findings have been incorporated

into major guidelines, including those of the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the International

Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) (17–19).

Nevertheless, several challenges persist in this

rapidly evolving field. First, the selection of biomarkers remains

contentious: The CheckMate 816 trial revealed marked pCR rate

disparities comparing between the PD-L1 ≥1% and PD-L1 <1%

subgroups (13), whereas the

KEYNOTE-091 trial revealed PD-L1-independent DFS benefits.

Secondly, safety optimization of combination strategies warrants

urgent attention, as exemplified by the 32% grade 3–4 adverse event

(AE) rate with dual immunotherapy that was observed in the

CheckMate 77T trial (20).

Furthermore, the limited efficacy of ICIs noted in epidermal growth

factor receptor (EGFR)/anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-altered

NSCLC needs to be followed up with mechanistic studies (21). Lastly, long-term follow-up data are

required to fully characterize the impact of immune-associated AEs

(irAEs) on perioperative outcomes (22).

Currently, the paradigm of perioperative management

is expanding toward integrated systemic approaches that target not

only tumor cells, but also the microenvironment of the host.

Increasing evidence has highlighted the pivotal role of systemic

inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in modulating treatment

efficacy; for example, an elevated neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio

was reported to be associated with impaired OS [hazard ratio

(HR)=1.74] and progression-free survival (PFS; HR=1.53) rates

across malignancies, reflecting pro-tumorigenic inflammation that

may undermine immunotherapeutic responses (23). In addition, metabolic syndrome,

which is characterized by chronic inflammation and insulin

resistance, has been reported to increase cancer risk via adipokine

dysregulation and oxidative stress, thereby suggesting that

metabolic interventions may potentially act synergistically with

ICIs (24).

Concurrently, novel biomarkers are refining patient

stratification. The cachexia index, which integrates skeletal

muscle mass, albumin and neutrophil-associated lymphocytes,

predicts survival rates (OS, HR=2.03) independently of tumor stage,

thereby offering a multidimensional assessment of the

nutritional-inflammation status (25). Despite these emerging tools;

however, PD-L1, as a biomarker, retains its clinical relevance in

cases of advanced NSCLC: A high expression (≥50%) of PD-L1 remains

predictive of notably increased ICI responsiveness, warranting a

further exploration of its dynamic changes in perioperative

settings (26). These insights

align with other therapeutic advances that have recently been made;

for example, meta-analyses have confirmed that adjuvant PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors reduce the recurrence-free survival (RFS) risk across

solid tumors (HR=0.72), thereby supporting their broader

application beyond PD-L1 selection (27).

Future research efforts should prioritize precision

medicine through the application of multi-omics approaches [for

example, single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics

(28)] to decipher dynamic

tumor-immune microenvironment interactions, to develop circulating

tumor DNA (ctDNA)-based MRD monitoring systems and to explore novel

therapeutic combinations [for example, immunotherapy with targeted

agents (29) or epigenetic

modulators (30)] to overcome drug

resistance. Real-world evidence will be key to the validation of

treatment paradigms in special populations. Subsequently, the

present review will systematically examine recent advances that

have been made in perioperative immunotherapy through four

dimensions, namely clinical applications, combination strategies,

biomarker development and future challenges, with the aim of

providing information for evidence-based clinical decision-making

in the future.

Literature identification strategy

The present narrative review has compiled evidence

from pivotal clinical trials published between January 1, 2007 and

August 31, 2025, using the search terms ‘perioperative

immunotherapy’, ‘neoadjuvant/adjuvant’, ‘lung cancer’ and ‘clinical

trial’. Key sources included the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Web of Science

(https://www.webofscience.com) databases,

proceedings from major oncology conferences (for example, those

organized by American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (31–33)

and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) (34) and IASLC (35,36)

and American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) (37) and the Clinical Trials website

(clinicaltrials.gov) (for ongoing

trials). Phase III randomized controlled trials (for example,

CheckMate816 and KEYNOTE-671) were prioritized, along with

practice-changing phase II studies that have informed recent

guideline updates (for example, the updates made to version 7.2025;

NCCN (18) and Neoadjuvant and

Adjuvant Treatments for Early-Stage Resectable NSCLC Consensus

Recommendations From IASLC (19).

In addition, emphasis was placed on perioperative outcomes

(regarding parameters such as the pCR and the EFS/OS rate),

biomarker correlates (PD-L1 and ctDNA) and the safety profiles of

immunotherapy combinations.

Theoretical basis and mechanism of

perioperative immunotherapy

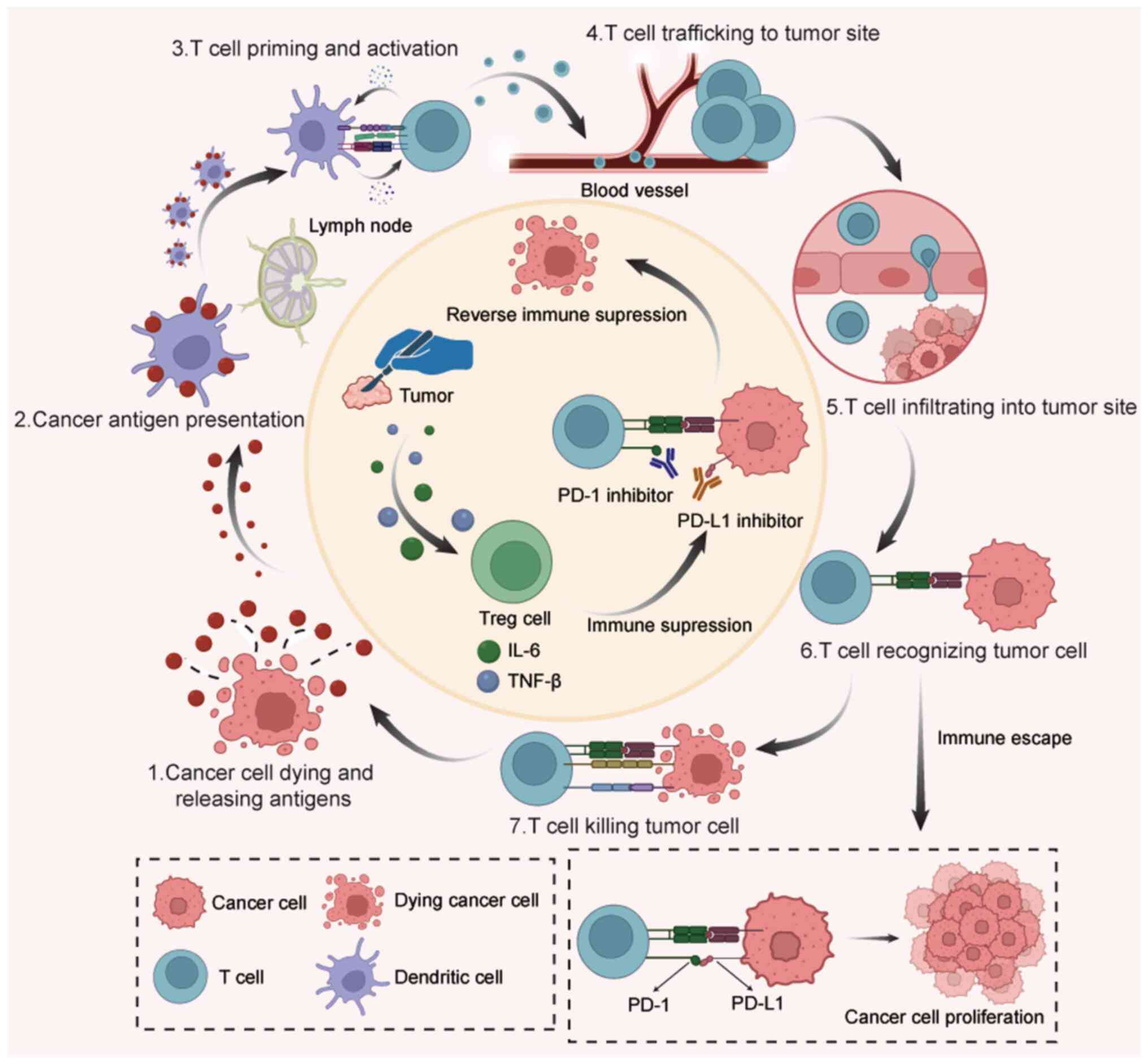

The cancer-immunity cycle, a fundamental biological

process governing immune-mediated tumor recognition and

eradication, comprises seven sequential steps, namely tumor antigen

release, antigen presentation, T-cell activation, T-cell

trafficking to tumor sites, tumor-infiltrating T-cell recognition

of cancer antigens, tumor cell killing and the establishment of

immunological memory. ICIs primarily function by counteracting

immunosuppressive signals within the tumor microenvironment (TME),

thereby reactivating antitumor immune responses (Fig. 1) (38–44).

However, the seven steps in the cancer-immunity cycle of lung

cancer tumors are notably specific and different perioperative

immunotherapy approaches work through a range of different

mechanisms (Table I) (45–50).

| Figure 1.Mechanism of tumor immune cycle. 1)

When tumor cells die, they release tumor antigens, which are then

captured by DCs in the lymph nodes. 2) Antigen presentation, where

dendritic cells process and present tumor antigens to naïve T

cells. 3) Priming and activation of naïve T cells: The naïve T

cells receive an antigenic signal (from dendritic cells) and a

co-stimulatory signal (e.g., CD28/B7), subsequently differentiating

into effector T cells. 4) After CD40L on the T-cell surface binds

to CD40 on the DC surface, this ‘reverse signaling’ potently acts

back upon the DC. This further upregulates the expression of

co-stimulatory molecules such as B7 on the dendritic cell, thereby

establishing a positive feedback loop for T cell activation. 5)

Migration of activated T cells: Effector T cells exit the lymph

node, enter the bloodstream and traffic towards the tumor site

guided by chemokine signals. 6) Under the influence of chemokines,

T cells first undergo firm adhesion to the vascular endothelium.

They then deform and transmigrate through the junctions between

endothelial cells to enter the tumor immune microenvironment. 7)

Process of T-cell recognition of tumor cells, wherein effector T

cells identify tumor-specific antigens presented on the major

histocompatibility complex molecules of the tumor cells through

their T cell receptors. 8) Cytotoxic killing of tumor cells by T

cells. Effector T cells induce cancer cell apoptosis either by

secreting cytotoxic mediators like perforin and granzymes, or by

activating the death receptor pathway such as Fas/FasL. 9) Lysis of

tumor cells that underwent apoptosis and the subsequent release of

new tumor antigens, indicating the initiation of a renewed

antitumor immunity cycle. 10) Surgery can lead to the formation of

an immunosuppressive microenvironment. The physical tissue damage

from surgical incision causes the release of Damage-Associated

Molecular Patterns (DAMPs); these signals recruit Tregs to the

surgical site and, in some cases, drive the conversion of naïve

CD4+ T cells into newly induced Tregs. This process establishes a

state of local immunosuppression that impedes the antitumor

immunity cycle. 11) Mechanism by which immunotherapy reverses

immune suppression. The co-inhibitory signaling pathway formed by

PD-1 and its primary ligand PD-L1 (B7-H1) impairs the proliferation

and cytokine production of effector T cells. PD-1 inhibitors

(anti-PD-1 antibodies) bind with high affinity to the PD-1 receptor

on T cells, whereas PD-L1 inhibitors (anti-PD-L1 antibodies) bind

to the PD-L1 ligand on tumor cells. This intervention physically

blocks the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction and subsequent downstream

signaling activation. Consequently, the co-stimulatory signals

received by T cells are fully transmitted and TCR signal

transduction is restored to normal. 12) Immunotherapy, primarily

utilizing PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, reverses the localized

immunosuppression previously caused by surgery. This enables T

cells to resume their cytotoxic function against tumor cells via

the cancer-immunity cycle, underscoring the critical importance of

perioperative immunotherapy in lung cancer. 13) Immune evasion by

tumor cells, whereby they avoid immune attack through various

immunosuppressive mechanisms (such as PD-L1 overexpression and

infiltration of regulatory T cells) or via antigen loss. 14)

Proliferative phase following tumor immune escape. Specifically,

PD-L1 on tumor cells binds to PD-1 on T cells, delivering an

inhibitory signal. This fosters an immunosuppressive

microenvironment that microenvironment that allows tumor cells to

evade T cell-mediated killing, leading to their uncontrolled

expansion uncontrolled expansion. PD-1, programmed cell death

protein-1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; DC, dendritic cell;

Treg, regulatory T cell. |

| Table I.Lung cancer-specific mechanism in the

cancer-immunity cycle and perioperative immunotherapy measure. |

Table I.

Lung cancer-specific mechanism in the

cancer-immunity cycle and perioperative immunotherapy measure.

| Method | Lung

cancer-specific mechanism | Perioperative

immunotherapy measure | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Antigen

release | In >30% of lung

adenocarcinomas, NSCLC-derived TGF-β/IL-10 suppresses antigen

release, restricting neoantigen availability | Neoadjuvant

immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy forced the release of

HMGB1/ATP by chemically destroying the structure of tumor cells and

inhibited the mitochondrial dysfunction caused by TGF-β signaling

and compensatory STK11 mutation, thus breaking through the release

barrier of lung cancer-specific antigens | (45,46) |

| Antigen

presentation | Dendritic cell

priming efficiency is reduced in >40% of NSCLC cases due to

impaired antigen presentation caused by HLA class I

downregulation | Neoadjuvant

immunotherapy triggers immuno therapy triggers IFN-γ release from

activated CD8+ T cells. This cytokine then upregulates

HLA-I expression on lung cancer cells via the JAK-STAT pathway,

thereby reversing the antigen presentation defect | (45,47) |

| T-cell

activation | Antitumor immunity

is often compromised by elevated Tregs and MDSCs in the lung tumor

microenvironment, particularly in EGFR-mutant lung cancer | During the

perioperative period, the combination of PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors

promotes T-cell activation via two parallel actions: Blocking the

CTLA-4/CD80 axis to reduce Treg-mediated suppression and reversing

the impairment of dendritic cell cross-presentation commonly

associated with EGFR mutations | (48,49) |

| T-cell

transport | T-cell transport

into lung tumors is hindered by VEGF-mediated dysfunctional

vasculature and dysregulation of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in lung

cancer | To restore

efficient T-cell transport to tumors, perioperative immunotherapy

combined with anti-VEGF therapy normalizes the aberrant lung cancer

vasculature by inhibiting VEGF signaling and concurrently

counteracts the dysregulated CXCL12/CXCR4 chemotaxis axis | (46,47) |

| T-cell

infiltration | Lung

cancer-associated fibroblasts synthesize and secrete large amounts

of type III collagen, which encircles tumor cell clusters to form a

dense, enveloping structure that acts as a physical barrier,

thereby preventing CD8+ T-cell infiltration | Perioperative

immunotherapy or operative immunotherapy combined with a TGF-β

inhibitor blocked the TGF-β/SMAD pathway, suppressing collagen

synthesis and cross-linking in cancer-associated fibroblasts,

weakening the physical barrier of the tumor and ultimately

restoring CD8+ T-cell infiltration | (48,49) |

| Tumor

identification | Lung cancer cells

activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, whose activation

inhibits the transcription factor NLRC5 (key for MHC-I), leading to

the downregulation of specific antigen presentation on the cell

surface | Perioperative

immunotherapy or operative immunotherapy combined with a CTLA-4

inhibitor blocks the CTLA-4/B7 signaling pathway in lymph nodes.

This action liberates naïve T cells from Treg-mediated suppression,

enabling their activation and clonal expansion against diverse

tumor antigens. Consequently, this broadens the TCR repertoire and

enhances the immune system's capacity to recognize a broader

spectrum of tumor antigens. | (45,49) |

| Killing of lung

cancer cells | The cytotoxic

function of T cells against lung cancer is suppressed through

Fas-L-mediated induction of T cell exhaustion and concomitant

inhibition of granzyme B. | Perioperative

immunotherapy combined with an IL-15 agonist enhances the

tumor-killing efficacy of CD8+ T cells against lung cancer by

activating the JAK3/STAT5 pathway. This activation rescues

Fas-L-mediated T cell depletion and augments granzyme B

expression. | (46,48,50) |

Clinical practice and evidence of

perioperative immunotherapy

Exploration of neoadjuvant monotherapy

immunotherapy

The exploration of ICIs in neoadjuvant therapy began

with early single-agent clinical studies, aimed at evaluating their

potential to induce pathological remission and assessing their

safety. Although neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with

chemotherapy has become the predominant strategy, research on

neoadjuvant monotherapy immunotherapy continues to provide key

insights into the biological effects of immunotherapy and patient

selection.

In the CheckMate 159 trial (12), the major pathological response (MPR)

rate of nivolumab monotherapy was reported to reach 45% and

patients with a high tumor mutational burden (TMB) exhibited

notable pathological remission. Furthermore, the 5-year RFS risk

for PD-L1+ patients was reduced by 64% (HR=0.36),

whereas the MPR rate for PD-L1− patients was 30%,

demonstrating that PD-L1− patients could also derive

certain benefit from the therapy. Furthermore, the LCMC3 study

(11) further validated the

feasibility of neoadjuvant immunotherapy monotherapy. The MPR rate

of atezolizumab monotherapy was reported to be 20%, although this

increased significantly to 33% in the PD-L1 ≥50% subgroup compared

with only 11% in the tumor proportion score (TPS) <1% group

(P=0.01). The MPR rate in the TMB ≥16 mutant/Mb subgroup was also

33%, whereas it was only 13% in the low TMB group (P=0.12),

highlighting the synergistic screening potential of dual markers.

Furthermore, compared with traditional neoadjuvant chemotherapy

studies that had an MPR rate of 19% and a treatment-related AE

(TRAE) rate of 57%, (51), the MPR

rate of neoadjuvant monotherapy immunotherapy increased to 20–45%,

with markedly reduced toxicity. The incidence of grade 3 TRAEs was

11–23%, which was notably lower than the 60% incidence of TRAEs

observed in neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Notably, the surgical delay

rate in the LCMC3 study was extremely low. Similarly, in the

NEOSTAR monotherapy group (52),

the MPR rate was 22%, while the pCR rate was 9%, both markedly

higher compared with those of patients receiving traditional

chemotherapy. However, there remained a gap in the efficacy of

monotherapy compared with the dual immunotherapy combination: For

example, the MPR rate of the nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination

increased to 38%, whereas that of the monotherapy group was only

22% and the dual immunotherapy combination also led to the

induction of higher levels of effector T cell infiltration, with a

50% increase in CD8+ T cells compared with neoadjuvant

immunotherapy monotherapy (P=0.033) (34,52–54).

In general, the pCR of the neoadjuvant monotherapy

immunotherapy was reported to be low (generally of the order of

<10-15%). Furthermore, the pCR was notably lower compared with

that of immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy; for example, the

MPR in the CheckMate 816 trial was reported to be 24%. It should be

noted that the majority of the single-agent studies had small

sample sizes and limited representativeness (Table II).

| Table II.Clinical trials of neoadjuvant ICIs

for lung cancer. |

Table II.

Clinical trials of neoadjuvant ICIs

for lung cancer.

| First author,

year | Trial (NCT

Identifier) | Phase | Stage | No. of

patients | ICI | Primary

endpoint | pCR rate, % | MPR rate, % | Survival

outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Chaft et al,

2022 | LCMC3

(NCT02927301) | II | IB-IIIB | 181 | Atezolizumab | MPR | 6.80 | 20.40 | DFS rate, 72%; OS

rate, 82% | (11) |

| Forde et al,

2021 | CheckMate 159

(NCT02259621) | II | I–IIIA | 21 | Nivolumab | Safety | 10.00 | 45.00 | RFS rate, 60%; OS

rate, 80% | (12) |

| Forde et al,

2022 | CheckMate-816

(NCT02998528) | III | IB-IIIA | 358 | Nivolumab | EFS, pCR | 24.0 vs. 2.20 | 36.9 vs. 8.90 | EFS rate, 57 vs.

43%; OS rate, 78 vs. 64%; mOS, NR vs.73.7month | (13) |

| Besse et al,

2020 | PRINCEPS

(NCT02994576) | II | IA-IIIA | 30 | Atezolizumab | The rate of

patients without major toxicities or morbidities | 0 | 14.00 | NA | (34) |

| Zhu et al,

2022 | LungMate 002

(unregistered) | II | II–III | 50 | Toripalimab | MPR | 27.80 | 55.60 | NA | (57) |

| Wislez et

al, 2022 | IONFSCO

(NCT03030131) | II | IB-IIIA | 46 | Durvalumab | The complete

surgical resection rate | 7.00 | 19.00 | DFS rate, 78.3%; OS

rate, 89.1% | (58) |

| Lei et al,

2023 | TD-FOREKNOW

(NCT04338620) | II | IIIA or IIIB | 88 | Camrelizumab | pCR | 32.60 vs. 8.90 | 65.10 vs.

15.60 | EFS rate, 76.9 vs.

67.6%; DFS rate, 78.4 vs.71.7 % | (59) |

| Liu et al,

2023 | CTONG 1804

(NCT04015778) | II | IIA or IIIB | 48 | Nivolumab | MPR | 25 | 50 | NA | (60) |

| Shao et al,

2023 | neoSCORE

(NCT04459611) | II | IB-IIIA | 60 | Sintilimab | MPR | 19.2 vs. 24.1 | 26.90 vs.

41.40 | NR | (61) |

| Zhang et al,

2024 | neoSCORE II

(NCT05429463) | III | IIA-IIIB | 250 | Sintilimab | MPR | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing | (62) |

| NA | LungMate-009

(NCT04728724) | II | III | 100 | Sintilimab | MPR | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing | (63) |

Advances in neoadjuvant immunotherapy

combined with chemotherapy

At present, a combination of ICIs and chemotherapy

has become the standard regimen for the neoadjuvant treatment of

resectable NSCLC (55). This

strategy works by enhancing tumor antigen release via

chemotherapeutic-induced immunogenic cell death (ICD) and

synergistically activating systemic antitumor immune responses with

ICIs, thereby causing marked improvements in pathological remission

rates and long-term survival.

CheckMate 816 trial

Global studies have demonstrated that the pCR rate

of nivolumab in combined chemotherapy was 24%, markedly higher

compared with the 2.2% reported for the chemotherapy control group

and the MPR rate was 34%, also much higher compared with the MPR

rate of 12% recorded for the chemotherapy control group. Of note,

the pCR rate of Chinese patients was as high as 25% (13,56).

Furthermore, in the LungMate 002 study (50), the pCR rate for the neoadjuvant

toripalimab plus chemotherapy subgroup was reported to be as high

as 27.8% and the MPR rate was as high as 55.6%. Patients with high

baseline expression of chitinase 3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1)

[according to the immunohistochemical (IHC) score] exhibited

significantly improved pCR and survival outcomes (for OS, HR=0.17

and P=0.017), demonstrating that CHI3L1 can serve as an independent

predictive marker. By contrast, the pCR rate for neoadjuvant

immunotherapy alone was only 10–15%, whereas the pCR improvement

following neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy was

notable (the combination therapy group achieved 27.8% pCR in

LungMate 002, while the pCR rate in the combination therapy group

was 24% in CheckMate 816), highlighting the enhanced efficacy of

the combined regimen.

Regarding surgical feasibility, in the CheckMate 816

study, the surgery rate for the immunotherapy combined with

chemotherapy group was reported to be 83.2% (compared with 75.4%

for the chemotherapy alone group) and more minimally invasive

surgeries were performed. Furthermore, in the LungMate 002 study,

65.8% of the 76% of the patients who were potentially resectable in

the neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy group were

converted into operable patients, achieving a total R0 resection

rate of 100% (where ‘R0 resection’ refers to a surgical outcome

where all the cancerous tissue is removed). Additionally, the

administration of neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with

chemotherapy achieved a lymph node downstaging rate of 63.9%,

suggesting that this regimen led to a marked improvement in

surgical feasibility via the reduction of tumor size and

downstaging.

In terms of safety, the incidence of grade 3–4 TRAEs

in the neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy group

in the CheckMate 816 study was reported to be 33.5%, a percentage

that was similar to the reported percentage of 36.9% in the

chemotherapy alone group, and neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined

with chemotherapy did not lead to increases in the rates of

surgical complications or delays. In the LungMate 002 study, the

incidence of grade 3–4 TRAEs in neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined

with chemotherapy was reported to be 34%. Overall, compared with

monotherapy immunotherapy, the chemotoxicity of combined

chemotherapy was reported to be slightly higher, although its

safety may have been well controlled through standardized

management and this toxicity did not markedly affect surgical

safety. By contrast, monotherapy immunotherapy may lead to a higher

risk of tumor progression due to insufficient efficacy. Subgroup

analysis revealed that the pCR rate (partial response to curative

therapy) for patients with PD-L1 levels ≥1% in the CheckMate 816

trial was 32.6%, markedly higher compared with the pCR rate of

16.7% observed in the subgroup with PD-L1 levels <1%. In

summary, the administration of immunotherapy combined with

chemotherapy causes the release of tumor antigens, thereby

enhancing immune responses and compensating for the insufficient

immune response rate in neoadjuvant monotherapy, which provides a

focus in the field of neoadjuvant immunotherapy with more potential

benefits than drawbacks (Table II)

(11–13,34,57–63).

Synergistic effect of immunotherapy

combined with radiotherapy (RT)

The combined use of RT and ICIs is based on the

principle that RT induces ICD in tumor cells, leading to the

release of damage-associated molecular patterns, which, in turn,

enhance the antigen-presenting ability of dendritic cells (DCs).

ICIs subsequently further alleviate systemic immunosuppression,

creating an ‘in situ vaccine’ effect (64).

Key studies have validated the clinical potential of

this strategy. In the SQUAT trial (65), the MPR rate of the neoadjuvant

durvalumab combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (50 Gy) was

reported to be 63%, which was notably higher compared with the MPR

rate of 36.8% reported in the CheckMate 816 trial for neoadjuvant

immunotherapy plus chemotherapy. Furthermore, the pCR rate in the

SQUAT trial was 23%, similar to the 24% pCR rate noted in the

CheckMate 816 trial, indicating that neoadjuvant immunotherapy

combined with chemotherapy led to a notable enhancement in the

extent of pathological remission (65). In terms of long-term survival,

compared with traditional RT, the objective response rate (ORR) for

the KEYNOTE-799 regimen with concurrent chemoradiation therapy

(cCRT) plus pembrolizumab was 70.5–70.6%, whereas the ORR for the

NICOLAS regimen with cCRT plus nivolumab was 73.4%. Both regimens

were noted to have higher ORRs compared with the 35–55% range

observed in traditional chemoradiotherapy (66,67).

In terms of safety, the SQUAT trial reported a 48%

rate of grade 3–4 AEs (including only 1 case of fatality that was

associated with the treatment), which was higher compared with that

of chemotherapy alone or monotherapy immunotherapy. However, the

toxicity profile was reported to be similar to that of historical

Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy data (68). Furthermore, the most notable AE

arising from neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with RT was shown

to be radiation pneumonitis. The incidence of grade 3 or higher

pneumonia in the KEYNOTE-799 and NICOLAS combination regimens was

6.9% and up to 10%, respectively. By contrast, the incidence of

grade 3 or higher radiation pneumonitis in traditional

chemoradiotherapy is typically reported to be between 7 and 20%

(69). This suggests that the

addition of RT did not exceed the safety threshold. In terms of

surgical feasibility, all patients in the SQUAT trial completed

their surgeries on schedule, with no reports of surgery delays due

to RT.

Regarding the expression of PD-L1, in the

KEYNOTE-799 study, the ORR for patients with PD-L1 TPS <1% in

cohorts A and B was reported to be 66.7 and 71.4%, respectively,

whereas for those patients with PD-L1 ≥1% in cohorts A and B, the

ORR was 75.8 and 72.5%, respectively. This demonstrates that there

is minimal difference in efficacy among patients with different

expression levels of PD-L1. Although the SQUAT trial did not

subdivide the PD-L1 groups, the overall MPR rate was still as high

as 63%, indicating its broad-spectrum efficacy. However, although

the SQUAT trial demonstrated a high MPR rate of 63% for neoadjuvant

chemoradiotherapy combined with immunotherapy, the 2-year PFS rate

was only 43% and no notable improvements were observed in terms of

patient survival. This may suggest that, although RT enhances local

immune activation, it may not effectively eliminate MRD.

Additionally, the SQUAT trial did not report distant recurrence

rates, suggesting that RT might either induce T-cell exhaustion or

upregulate PD-L1, thereby weakening the systemic effects of

durvalumab and potentially affecting the long-term prognosis of

patients.

Postoperative adjuvant

immunotherapy

The results from IMpower010 (16), a randomized, multicenter, open-label

phase 3 trial, demonstrated that postoperative adjuvant

chemotherapy followed by sequential atezolizumab treatment led to a

notable reduction in the recurrence risk in the PD-L1 ≥50% subgroup

(DFS, HR=0.48; OS, HR=0.47). Compared with the Best Supportive Care

(BSC) group, which was reported to have a 5-year DFS rate of only

67.5%, the 5-year DFS rate for the adjuvant atezolizumab treatment

group increased to 84.8% and distant metastasis was well

controlled. The distant metastasis recurrence rate in the adjuvant

atezolizumab treatment group was reported to be 6.8% compared with

12.5% in the BSC group, with particularly good control exerted over

brain metastasis recurrence. Furthermore, in another study,

KEYNOTE-091 (17), treatment

postoperatively with the adjuvant pembrolizumab demonstrated DFS

benefits in the overall population (HR=0.76), although this did not

reach significance in the PD-L1 ≥50% subgroup (HR=0.82).

In terms of safety, the incidence of grade 3–4 irAEs

in the IMpower010 study was only 11%, compared with an incidence of

25% for cisplatin-associated grade 3–4 nausea/vomiting when

traditional adjuvant therapy was administered. This suggests that

adjuvant immunotherapy is both safer and more tolerable compared

with traditional adjuvant chemotherapy. In the KEYNOTE-091 trial,

although the incidence of grade 3–4 irAEs was higher (at 34%) among

patients receiving postoperative adjuvant immunotherapy, only 4

cases were reported to be associated with myocarditis or pneumonia.

This indicated that fatal irAEs are rare and that the majority of

irAEs are manageable, rendering them easier to manage compared with

the long-term toxicities associated with chemotherapy, such as

kidney damage (70) and hearing

loss (71). Notably, in both the

IMpower010 and the KEYNOTE-091 trials, administering sequential

immunotherapy following chemotherapy did not lead to any notable

increase in cumulative toxicity, supporting the synergistic model

of chemotherapy clearing the immunosuppressive microenvironment

combined with immunomodulation (16,17).

In addition to the aforementioned postoperative adjuvant

immunotherapy, clinical trials of postoperative adjuvant

immunotherapy in combination with other regimens, such as

INTerpath-002 and SKYSCRAPER-15, have gradually revealed their

application prospects (Table III)

(16,17,31,32,35–37,72–75).

| Table III.Clinical trials of adjuvant ICIs for

lung cancer. |

Table III.

Clinical trials of adjuvant ICIs for

lung cancer.

| First author,

year | Trial (NCT

identifier) | Phase | Stage | No. of

patients | ICI | Primary

endpoint | Survival

outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Felip et al,

2021 | IMpower010

(NCT02486718) | III | IB-IIIA | 1,005 | Atezolizumab | DFS | Stage II–IIIA

(PD-L1 ≥1%) mDFS, NE vs. 35.3 months; Stage II–IIIA (all) mDFS,

42.3 vs. 35.3 months; Stage IB-IIIA (all) mDFS, NE vs. 37.2

months | (16) |

| O'Brien et

al, 2022 | KEYNOTE-091

(NCT02504372) | III | IB-IIIA | 1,177 | Pembrolizumab | DFS | Stage IB-IIIA

(PD-L1 ≥50%) mDFS, 67.0 vs. 47.6 months; Stage IB-IIIA (all) mDFS,

53.8 vs. 43.0 months | (17) |

| Spicer et

al, 2024 | INTerpath-002

(NCT06077760) | III | II, IIIA and

IIIB | 868 | V940 +

pembrolizumab | DFS | Ongoing | (72) |

| Garon et al,

2024 | CANOPY-A

(NCT03447769) | III | II–IIIB | 1,382 | Canakinumab | DFS | mDFS, 35.0 vs.

29.7months | (73) |

| Goss et al,

2024 | ADJUVANT BR.31

(NCT02273375) | III | IB-IIIA | 1,415 | Durvalumab | DFS | NA | (37) |

| Zhu et al,

2023 | DUBHE-L-304

(NCT05487391) | III | II–IIIB | 632 | QL1706 | DFS | Ongoing | (31) |

| Chaft et al,

2017 | ANVIL

(NCT02595944) | III | IBf-IIIA | 903 | Nivolumab | DFS and OS | Ongoing | (74) |

| Calvo et al,

2021 | NADIM-ADJUVANT

(NCT04564157) | III | IB-IIIA | 210 | Nivolumab | DFS | Ongoing | (32) |

| NA | SKYSCRAPER-15

(NCT06267001) | III | IIB-IIIB | 1,150 | Tiragolumab +

Atezolizumab | DFS | Ongoing | (75) |

| Peters et

al, 2021 | MERMAID-1

(NCT04385368) | III | II–III | 89 | Durvalumab | DFS | Ongoing | (35) |

| Spigel et

al, 2021 | MERMAID-2

(NCT04642469) | III | II–III | 30 | Durvalumab | DFS | Ongoing | (36) |

Adjuvant immunotherapy during the

perioperative period

The ‘sandwich model’ of perioperative immunotherapy

for lung cancer comprises a comprehensive strategy that includes

preoperative neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy,

surgical resection and postoperative adjuvant immunotherapy to

consolidate treatment. This approach aims to activate the immune

system preoperatively to shrink tumors and to reduce the stage of

cancer, to achieve radical resection during surgery and to

continuously eliminate MRD postoperatively.

In the NEOTORCH trial (a randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled phase 3 trial), the triple therapy group

achieved a pCR rate of 24.8%, whereas in the RATIONALE-315 trial

(another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3

trial), this rate increased to 56% (76,77).

By contrast, in the LCMC3 study, the pCR rate for patients

receiving only immunotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment was only 6%

(11), and in the CheckMate 816

trial (13), the pCR rate for

patients receiving combined immunotherapy and chemotherapy as

neoadjuvant treatment was only 24%. Furthermore, in the KEYNOTE-671

study (14), the MPR rate for

patients treated with the triple therapy model reached 63.8%, in

the RATIONALE-315 trial it was 56% and in the NEOTORCH trial it was

48.5%; by contrast, in the CheckMate 816 study, the MPR rate for

patients receiving combined immunotherapy and chemotherapy as

neoadjuvant treatment was only 24%, and in the NEOSTAR study, the

MPR rate for the single-agent neoadjuvant immunotherapy group was

only 22%. This clearly demonstrates that, in terms of pathological

remission, the triple therapy model is markedly more effective

compared with monotherapy neoadjuvant treatment (13,52,76,77).

Additionally, from the perspective of surgical

feasibility, the surgical resection rate for patients treated with

the triple therapy model in the KEYNOTE-671 trial was as high as

93%; in the CheckMate 77T study, it was 89%; in the RATIONALE-315

study, it was 91%; whereas in the CheckMate 816 trial, the surgical

resection rate for patients receiving combined immunotherapy and

chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment was only 83.2%. According to

the subgroup analysis of CheckMate 816 trial, similarly to the

results in the single neoadjuvant setting, the sandwich model also

demonstrated a more notable benefit for patients with PD-L1 levels

of ≥1%. The EFS HRs were determined to be 0.52 and 0.58 in the

CheckMate 77T and KEYNOTE-671 trials, respectively. However, in the

subgroup with PD-L1 levels <1%, the HRs increased to 0.73 and

0.65, suggesting limited benefits for patients with PD-L1 levels

<1%. Nevertheless, the RATIONALE-315 study demonstrated that

patients with PD-L1 levels <1% still obtained certain benefit

(EFS, HR=0.57). This benefit was primarily due to the unique

mechanism of action of tislelizumab, whereby antibody-dependent

cell-mediated phagocytosis is reduced, thereby overcoming the

limitations of low PD-L1 expression and providing treatment

opportunities for these patients.

Notably, tislelizumab has been underutilized in

perioperative immunotherapy studies for lung cancer, with potential

for enhanced research on this ICI in later stages. Furthermore,

compared with the IMpower010 study, in which a simple adjuvant

therapy was administered, the survival benefits of the sandwich

model were more pronounced. In the NEOTORCH study, the EFS HR for

patients treated with the sandwich model was 0.40; in the

KEYNOTE-671 study, it was 0.59; and in the RATIONALE-315 study, it

was 0.56. By contrast, in studies of adjuvant immunotherapy alone,

the DFS HR for all patients receiving postoperative adjuvant

immunotherapy in the IMpower010 study was 0.79 and in the

KEYNOTE-091 study, the overall DFS HR was 0.76. Although the

primary endpoints of the sandwich model study and the adjuvant

postoperative treatment study differed, the EFS parameter includes

a broader range of events, such as local recurrence, distant

metastasis, second primary cancer and treatment-associated

mortality, rendering it more stringent compared with DFS, which

only includes recurrence/mortality. However, the sandwich model was

still reported to have an improved HR, demonstrating its ability to

comprehensively control tumor progression.

It should be noted that, although the sandwich model

exhibited a notably increased efficacy compared with simple

adjuvant and neoadjuvant immunotherapy, it may face greater

challenges in terms of safety management. In the tislelizumab group

of the RATIONALE-315 trial, the incidence of irAEs was reported to

be 40%, a percentage that was markedly higher than the incidence

rate of 18% for irAEs in the chemotherapy group. Furthermore, the

incidence of grade 3 or higher neutropenia in the tislelizumab

group was as high as 61% and these patients required close

monitoring and management. Additionally, administering long-term

adjuvant immunotherapy may increase the burden on patients. For

example, in the NEOTORCH study, the sandwich model treatment

regimen included treatment with 13 cycles of toripalimab. By

contrast, the treatment may be prematurely discontinued for certain

patients due to toxicity. For example, in the CheckMate 77T study,

35% of the patients did not complete the course of postoperative

adjuvant therapy due to intolerance to treatment-associated

toxicity (14,20,76,77).

In conclusion, perioperative immunotherapy, which

involves tumor shrinkage prior to surgery and continuous

immunosuppression following surgery, markedly outperforms

preoperative or postoperative adjuvant therapy in terms of

pathological remission and survival benefits. It is suitable for

most high-risk patients who are able to tolerate toxicity,

particularly in the cases of borderline resectable patients, to

improve surgical outcomes. For patients with PD-L1 levels ≥1%, it

is recommended to prioritize dual immunotherapy or combination

chemotherapy. These two treatment regimens were reported to achieve

marked pathological remission in the NEOSTAR and RATIONALE-315

studies. Even for the PD-L1− patients, the sandwich

model maintained its superiority compared with postoperative

adjuvant therapy; for example, in the CheckMate 77T trial, the EFS

HR for patients in the PD-L1 <1 group was only 0.65 (Table IV) (12,15,20,33,76–83).

| Table IV.Clinical trials of ‘sandwich’

combination regimens for lung cancer. |

Table IV.

Clinical trials of ‘sandwich’

combination regimens for lung cancer.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| pCR rate, % | MPR rate, % |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| First author,

year | Trial (NCT

identifier) | Phase | Stage | No. of

patients | ICI | Primary

endpoint | EG | CG | EG | CG | Survival

outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Spicer et

al, 2024 | KEYNOTE-671

(NCT03425643) | III | II–IIIB | 797 | Pembrolizumab | EFS, OS | 18.1 | 4.0 | 30.2 | 11.0 | mEFS, 47.2 vs. 18.3

months; OS rate, 71.3 vs. 64.0% | (14) |

| Sorscher et

al, 2024 | CheckMate-77 T

(NCT04025879) | III | IIA-IIIB | 461 | Nivolumab | EFS | 25.3 | 4.7 | 35.4 | 12.1 | mEFS, NR vs. 18.4

months | (20) |

| Yue et al,

2025 | RATIONALE-315

(NCT04379635) | III | II–IIIA | 453 | Tislelizumab | MPR, EFS | 40.7 | 5.7 | 56.2 | 15.0 | mEFS, NE vs.

NE | (76) |

| Lu et al,

2024 | Neotorch

(NCT04158440) | III | II–III | 501 | Toripalimab | MPR, EFS | 24.8 | 1.0 | 48.5 | 8.4 | mEFS, NE vs. 15.1

months; OS rate, 81.2 vs. 74.3% | (77) |

| Provencio et

al, 2022 | NADIM

(NCT03081689) | II | IIIA | 46 | Nivolumab | PFS | 63.0 | – | 83.0 | – | PFS rate, 77.1 %;

OS rate, 81.9 % | (78) |

| Provencio et

al, 2023 | NADIMII

(NCT03838159) | II | IIIA-IIIB | 86 | Nivolumab | pCR | 36.8 | 6.9 | 52.6 | 13.8 | PFS rate, 67.2 vs.

40.9%; OS rate, 85.0 vs. 63.6% | (79) |

| Heymach et

al, 2023 | AEGEAN

(NCT03800134) | III | IIA-IIIB | 802 | Durvalumab | pCR, EFS | 17.2 | 4.3 | 33.3 | 12.3 | mEFS, NR vs. 25.9

months | (15) |

| Yue et al,

2025 | RATIONALE-315

(NCT04379635) | III | II–IIIA | 453 | Tislelizumab | MPR, EFS | 40.7 | 5.7 | 56.2 | 15.0 | mEFS, NE vs.

NE | (76) |

| NA | ORIENT-99

(NCT05116462) | III | IIB-IIIB | 800 | Sindilizumab | pCR, EFS | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing | (80) |

| NA | KN035-CN-017

(NCT06123754) | III | IIIA-IIIB (N2) | 390 | Envafolimab | MPR, EFS | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing | (81) |

| Romero Román et

al, 2021 | IMpower-030

(NCT03456063) | III | II–IIIB | 451 | Atezolizumab | EFS | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing | (82) |

| Cascone et

al, 2022 | NeoCOAST-2

(NCT05061550) | II | II–IIIB | 490 | Arm 1, oleclumab +

Durvalumab; Arm 2, monalizumab + durvalumab; Arm 3, Volrustomig;

Arm 4, Dato-DXd + durvalumab; Arm 5, AZD0171 + durvalumab | pCR, AEs, SAEs | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing | (33) |

| Yan et al,

2023 | SHR-1316-111-303

(NCT04316364) | III | II–IIIB | 537 | SHR-1316 | MPR, EFS | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing | (83) |

As discussed previously, employing the sandwich

therapy regimen leads to a notable improvement in pathological

response rates and survival outcomes, although it also presents

greater safety challenges compared with administering monotherapy

with neoadjuvant immunotherapy. First, the sandwich therapy regimen

is associated with markedly higher rates of TRAEs, particularly

irAEs, compared with monotherapy. Furthermore, its extended

treatment duration markedly increases the risks of cumulative

toxicity, leading to its discontinuation during the adjuvant

immunotherapy phase, thereby imposing heavier financial burdens on

patients. The current consensus recommends neoadjuvant

immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for all patients with

operable stage II–III lung cancer. However, whether postoperative

immunotherapy should be upgraded to sandwich therapy remains a

subject of ongoing debate (19,55,84).

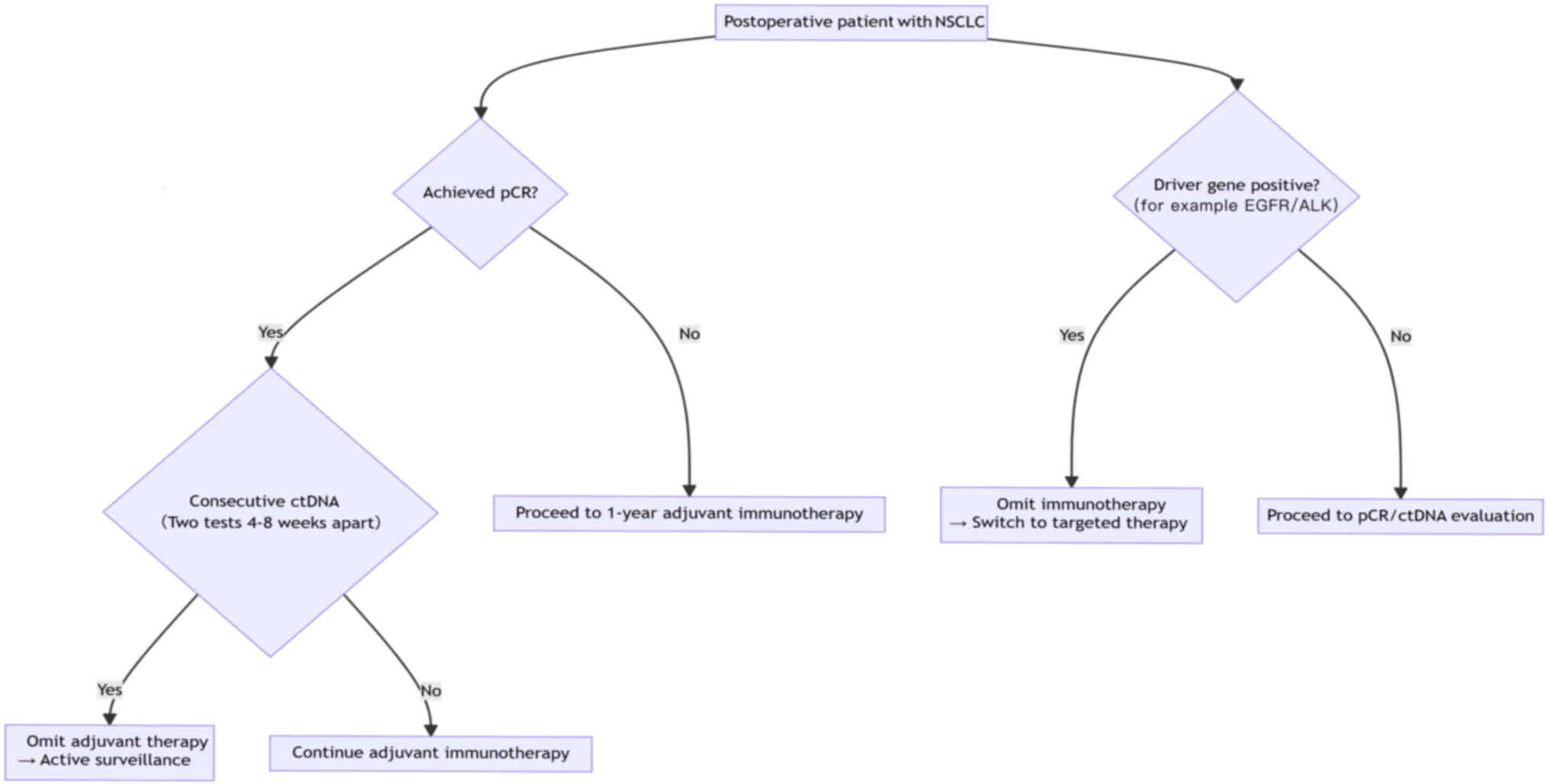

Therefore, the findings of recent studies on perioperative

immunotherapy for lung cancer have led to the development of the

clinical decision pathway for omission of adjuvant immunotherapy in

NSCLC (Fig. 2). The core criteria

for pathogenesis-guided adjuvant immunotherapy are pCR with

postoperative sustained ctDNA negativity or switching to targeted

therapy in driver gene-cases. High-risk patients (namely, those

with stage III lung cancer, non-pCR patients and those with high

expression of PD-L1) should still complete standardized 1-year

adjuvant therapy; however, it must be emphasized that, even in

terms of the pCR, patients with squamous cell carcinoma still face

a 5-year recurrence risk >30%. Therefore, maintaining full

adjuvant therapy is recommended. The current strategy faces

challenges due to limitations in pCR assessment (at present, ~8% of

micro-metastases are missed) and variations in ctDNA detection

sensitivity (currently, the false negative rate is in the range

5–10%). Thus, decision-making regarding exemption requires

multidisciplinary team consultation (84–88).

Biomarkers

Biological markers perform a key role in

perioperative immunotherapy, which is aimed at identifying

potential beneficiaries, optimizing treatment decisions and

predicting the risk of drug resistance. Currently, the most

extensively studied markers are PD-L1 expression, TMB and dynamic

monitoring of ctDNAs. However, their clinical application faces

numerous challenges. Emerging biomarkers, such as Gene Expression

Omnibus (GEO) profiles and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs),

are beginning to gain prominence.

Traditional biomarkers

In perioperative immunotherapy for lung cancer,

PD-L1, ctDNAs and TMB each have unique value as biomarkers,

although each of them has its limitations. PD-L1 expression is the

most widely used biomarker. The CheckMate 816 study demonstrated

that patients with PD-L1 levels of ≥1% had a pCR rate of 32.6%. The

KEYNOTE-671 study further confirmed that patients with high PD-L1

expression (TPS ≥50%) received more notable survival benefits.

Specifically, in patients treated with the sandwich model, those

with low PD-L1 expression (TPS <50%) had an EFS HR of 0.61,

whereas those with high PD-L1 expression had an EFS HR of only 0.41

(13,14). However, in the NEOTORCH study, no

clear association was identified between EFS benefit and PD-L1

expression. Although the EFS HR values for the subgroup with PD-L1

levels ≥50% and the sandwich model treatment subgroup with a PD-L1

level <50% were 0.31 and 0.35 respectively, neither of these

subgroups reached the level of statistical significance, suggesting

that PD-L1 expression levels may not serve as an independent

predictor of efficacy (77).

Furthermore, the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of PD-L1 limits its

predictive power, with temporal heterogeneity indicating that PD-L1

expression may vary dynamically with treatment. For example,

preoperative neoadjuvant therapy may alter the TME, leading to

changes such as TILs and the release of inflammatory factors. This

can result in the measured postoperative PD-L1 expression levels in

specimens being inconsistent with the baseline levels of patients,

thereby reducing the predictive value of PD-L1. The spatial

heterogeneity is evident in notable differences in PD-L1 expression

being reported among different regions within the same tumor or

between the primary lesion and metastatic sites. Therefore, biopsy

specimens may only reflect local expression status, rather than the

overall tumor characteristics (89).

As biomarkers, ctDNAs have performed particularly

well with respect to MRD monitoring. The CheckMate 816 subgroup

analysis revealed that patients who tested positive for ctDNA

post-surgery had an EFS event rate of 72.1% within 12 months,

compared with an EFS event rate of only 14.3% for those who tested

negative. Furthermore, the exploratory analysis of the KEYNOTE-671

study indicated a positive association between ctDNA clearance and

the pCR rate following neoadjuvant immunotherapy. In the ctDNA

clearance group where ctDNA was undetectable post-treatment, the

pCR rate reached 46.8%, whereas in the non-clearance group, where

ctDNA remained detectable post-treatment, the pCR rate was reported

to be only 7.7% (11,12). Therefore, the ‘TNMB staging’ model,

combining ctDNA and TNM staging, was proposed in the MEDAL study,

in which the results reported that the model was capable of

improving the accuracy of recurrence prediction by 28% (90).

TMB is a surrogate indicator of tumor neoantigen

load. The CheckMate 227 study demonstrated that, among patients

with high TMB (≥10 mut/Mb), those treated with nivolumab plus

ipilimumab achieved a median PFS of 7.2 months, whereas it was only

5.5 months in those with low TMB (<10 mut/Mb; HR=0.58). This

finding suggests that TMB may serve as a potential predictor of

short-term efficacy for immune-combination therapy (10). However, several perioperative

studies lack a standardized TMB testing standard (10,11).

Whole exome sequencing, which covers ~30,000 genes, does provide a

high-precision assessment of TMB, although it is costly and

complex, making it difficult to implement the method widely. By

contrast, TMB may be inferred from lower-cost targeted panel

sequencing, which covers limited genomic regions (typically 1–2

Mb), using the application of fitting algorithms. However,

different panel designs can lead to biased results; for example,

panels with smaller coverage areas may underestimate TMB values.

Furthermore, the TMB thresholds have been reported to vary across

different detection platforms; for example, the

FoundationOne®CDx platform (Foundation Medicine) detects

tissue TMB (tTMB) with a preset threshold of 10, 13 or 16 mut/Mb

for tTMB, whereas a preset threshold of 20 mut/Mb is used for blood

TMB (bTMB). Although all methods are able to distinguish between

high and low TMB levels, inconsistent thresholds have been reported

to result in varying clinical benefits. Currently, whole-exome

sequencing (WES) and large-panel sequencing are the most commonly

used methods for measuring TMB. However, a bridging study involving

patients with NSCLC found that 199 missense mutations detected by

WES corresponded to a TMB of 10 mut/Mb measured using the

FoundationOne CDx (F1 CDx) panel. Although the overall consistency

between the two methods reached 84, ~16% of patients may still be

misclassified as having low or high TMB due to platform

differences. Furthermore, in Cohort C of the BFAST trial,

atezolizumab was compared with chemotherapy as first-line therapy

for patients with unresectable, advanced-stage NSCLC characterized

NSCLC characterized by a bTMB cutoff of ≥10 mut/Mb. Interestingly,

in an exploratory analysis where bTMB was evaluated using the F1L

CDx assay with an equivalent cutoff of bTMB ≥13.60 mut/Mb,

atezolizumab significantly improved PFS compared with chemotherapy.

These examples indicate that even within the same population,

differences in threshold settings across platforms may result in

some patients being unable to be accurately matched with the most

suitable treatment regimen (91,92).

Other emerging markers

Gene expression profiling (GEP) analysis comprises

an exploration of immune-associated gene expression patterns in the

TME using high-throughput sequencing technology, including the

analysis of biological markers such as the interferon-γ (IFN-γ)

signaling pathway, T cell activation-associated genes [including

CD8A and granzyme B (GZMB)] and immunosuppressive molecules [such

as TGF-β and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1)] (93). In the LungMate 002 study, a receiver

operating characteristic curve was constructed by comparing the IHC

scores of baseline CHI3L1 with the post-treatment pathological

remission status. The area under the curve was calculated to be

0.732, indicating that the IHC score of CHI3L1 in baseline tumor

samples can predict the treatment response. Patients with high

CHI3L1 expression were reported to have an OS HR of 0.17 and a PFS

HR of 0.29, suggesting that patients with high CHI3L1 expression

had improved survival outcomes. Even in patients with

PD-L1− expression, those with high CHI3L1 expression

still derived a notable benefit from perioperative immunotherapy,

suggesting that CHI3L1 was able to effectively address the

prediction ‘blind spot’ of PD-L1. This is partly because CHI3L1 may

influence matrix remodeling by regulating immune-suppressive cells

in the TME, thereby enhancing the synergistic effect of

chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy.

Furthermore, PD-L1 only reflects the expression of

immune checkpoints on the surface of tumor cells and does not fully

capture the overall immune activity in the TME. Additionally, in

the LungMate 002 study, a high expression of human leukocyte

antigen (HLA)-DR was observed in the response group. HLA-DR, a

class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II cell

surface receptor, performs a key role in antigen presentation and

in the activation of CD4+ T cells. In this study, a

regimen of toripalimab combined with chemotherapy caused the

release of tumor antigens by administering chemotherapy, which,

when combined with PD-1 inhibitors to block immune checkpoints, led

to a synergistic enhancement of HLA-DR-mediated antigen

presentation, forming an immune positive feedback loop.

Furthermore, it was reported that CHI3L1 is positively associated

with HLA-DR expression, suggesting that CHI3L1 may indirectly

promote HLA-DR-mediated antigen presentation by regulating tumor

matrix remodeling (57). In

addition, in the NEOSTAR dual immunotherapy group, a notable

increase in GZMB upregulation was observed. This upregulation of

GZMB was reported to be associated with the expansion of effector

memory T cells (TEM) and tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM)

within tumors, suggesting that the upregulation of GZMB may enhance

T-cell function. Furthermore, patients with high GZMB expression

had a median viable tumor percentage of only ~9% compared with the

percentage of 50% observed in the single-agent immunotherapy group.

This suggested that GZMB-mediated T-cell toxicity is a key driver

of pathological remission. Additionally, in the dual immunotherapy

group, the mRNA levels of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 9 and

CXCL10 were markedly elevated. In this study, IHC analysis was also

performed, which confirmed that the protein expression levels of

CXCL9 and CXCL10 in the tumor tissues were higher compared with

those of the dual immunotherapy group, particularly in patients

with pathological remission. This may have been due to ipilimumab

blocking the inhibitory signals of regulatory T cells (Tregs),

thereby enhancing the antigen-presenting capability of the DCs and

promoting the secretion of CXCL9/10 (67).

TILs are lymphocytes that migrate from the blood

into tumor tissues, where they serve as a key component of the TME.

These cells have a dual regulatory role in immune response through

their recognition of tumor antigens, which is key to the

development, progression and treatment of tumors. TILs primarily

include CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, Tregs and

natural killer (NK) cells. In the CheckMate 159 study, it was

observed that, following immunotherapy, the number of

neoantigen-specific T cells in both tumor tissues and peripheral

blood were markedly increased. These increases were particularly

pronounced in patients who had achieved pCR, suggesting that

neoantigen-specific T cells may directly contribute to tumor

clearance. Additionally, in the NEOSTAR study, the combined

immunotherapy group exhibited a marked increase in the density of

CD8+ T cells infiltrating the tumor compared with the

monotherapy immunotherapy group. The proportions of TRM and TEM

were also increased, whereas the levels of Tregs and

myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which are

immunosuppressive cells, were decreased. Furthermore, in the LCMC3

study, it was reported that the density of Tregs and MDSCs in the

TME was negatively associated with the pathological response;

specifically, the enrichment of MDSCs was reported to be notably

associated with a low MPR rate for atezolizumab. In addition, it

was reported that immunoglobulin-like transcript 2 T cells were

also negatively associated with the MPR. The LCMC3 study also

demonstrated that the proportions of NK group 2 member D and

non-T/NK cells, including γδ T cells or congenital lymphocytes, in

baseline peripheral blood were positively associated with the MPR

(11,12) (Table

V) (32,36,75,79).

| Table V.Predictive and prognostic biomarkers

in perioperative immunotherapy for NSCLC. |

Table V.

Predictive and prognostic biomarkers

in perioperative immunotherapy for NSCLC.

| Biomarker | Detection method

positive criteria | pCR/MPR

prediction | Survival

association | Clinical

utility | Limitations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Inflammatory gene

signature | RNA-seq | pCR AUC=0.72 | OS HR=0.39 | 1. It fills the

prediction gap for patients with PD-L1 TPS <1% | 1. It requires

bioinformatics analysis and is difficult for clinical laboratories

to carry out | (32) |

|

|

|

|

| 2. Patients with

low expression of the inflammatory gene signature. Response may

require combination immunomodulators to enhance the

inflammatory | 2. There are no

large trials to confirm the clinical value of inflammatory gene

signatures |

|

| ctDNA

clearance | Tumor-informed

ctDNA clearance rate NGS ≥90% | pCR PPV= 92% | OS HR=0.33 | 1. It is emerging

MRD monitoring standards | 1.

Preoperative/postoperative paired testing is required to increase

the burden on patients | (36,75) |

|

|

|

|

| 2. It is an early

predictor of the efficacy of perioperative immunotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. High detection

costs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Patients with

undetected ctDNA may require enhanced adjuvant therapy |

|

|

| TILs density

(CD8+) | Multiplex IHC TILs

≥50 per HPF | MPR OR=4.2 | EFS HR=0.44 | 1. Patients with

high TILs density had an improved response to immunotherapy among

different pathologists | 1. There are

differences in the evaluation of TILs density | (36,75) |

|

|

|

|

| 2. Patients with

low TILs density may require combination of Immunotherapy and

chemotherapy | 2. Need for

multiple biopsies, low patient acceptance |

|

| HLA genotype | NGS (HLA-I/II

type)- | HLA-A*02:0; pCR

OR=3.1 | HLA-I

heterozygosity missing DFS HR=0.51 | 1. It can be used

as a personalized prediction for Asian patients | 1. Predictive value

is ethnically different | (36) |

|

|

|

|

| 2. It differences

may be the reason for different immune responses in different

patients | 2. HLA typing

requires special laboratory resources |

|

| TMB | WES/NGS TMB ≥10

mut/Mb | pCR AUC=0.59 | Limited data | 1. It fills the

prediction gap for patients with PD-L1 TPS <1% | 1. High detection

costs | (36) |

|

|

|

|

| 2. Patients with

high TMB may benefit from combination of immunotherapy and

chemotherapy | 2. Different

platforms have different testing standards |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Weak predictive

power |

|

|

| PD-L1 TPS | IHC PD-L1

TPS≥1% | pCR OR=2.1 (95% Cl,

1.6–2.8) | DFS HR=0.62 | 1. It is NCCN level

1 evidence | 1. Time

heterogeneity | (36,79) |

|

|

|

|

| 2. It can guide the

choice of immunotherapy monotherapy or immunotherapy combined with

chemotherapy | 2. Spatial

heterogeneity |

|

In addition to the aforementioned GEP analyses and

TILs, the NEOSTAR study also demonstrated that the abundance of

Ruminococcus and Akkermansia in the gut microbiota is

notably associated with the MPR of dual immunotherapy. This finding

suggests that specific bacterial populations may enhance antitumor

effects by modulating systemic immune responses (45), indicating that these specific

bacterial populations may have notable potential as biomarkers for

perioperative immunotherapy.

Application model of biomarkers in

perioperative immunotherapy for lung cancer

Current evidence suggests that integrated biomarker

models are able to enhance prediction accuracy (94). Therefore, our research group

developed a dynamic monitoring model for perioperative

immunotherapy in lung cancer that works through integrating

mainstream non-treatment biomarkers.

Neoadjuvant

First, ctDNA clearance rates were assessed in

patients with advanced unresectable lung cancer after one cycle of

neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Those achieving clearance continued with

the original treatment regimen, whereas those without clearance

either received an additional cycle of neoadjuvant immunotherapy or

switched to immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy (95).

Surgery

During the 4 weeks preceding surgery, changes in the

density of the TILs were continuously monitored. Patients with

increases in the number of CD8+ TILs of ≥30% were

scheduled for surgery as planned, whereas those with less marked

increases received either adjuvant RT or targeted therapy. Due to

the spatial heterogeneity in tumor biomarker expression (Table VI), intraoperative multi-region

sampling (core tumor area and peripheral zone) combined with

frozen-section pathology and IHC analysis was performed to stratify

patients for risk assessment and guide adjuvant therapy decisions.

High-risk patients (who were core MRD+ with peripheral

zone immunosuppression) were recommended adjuvant immunotherapy

combined with chemotherapy to enhance the clearance of residual

lesions in the core area. By contrast, low-risk patients (who were

core MRD− with peripheral zone immune activation) were

advised to receive adjuvant immunotherapy alone in order to reduce

chemotherapy toxicity (96).

| Table VI.Microenvironmental, biomarker and

clinical differences in tumor core zone and tumor edge zone. |

Table VI.

Microenvironmental, biomarker and

clinical differences in tumor core zone and tumor edge zone.

| Region | TME

characteristics | Differences in

biomarkers | Clinical

implications |

|---|

| Tumor core

zone | Tumors are

characterized by high cellular density, sparse vasculature and

limited oxygen supply | High PD-L1

expression is predominantly found on tumor cells, concurrent with a

low density of CD8+ TILs in the TME | Immune inhibitory

microenvironment has poor response to immunotherapy |

| Tumor edge

zone | Tumors are

characterized by low cellular density, a well-vascularized network

and ample oxygen supply. | High PD-L1

expression is predominantly found on immune cells, concurrent with

a high density of CD8+ TILs in the TME | Immune activation

microenvironment has a good response to immunotherapy |

Adjuvant

Thoracic drainage fluid ctDNA testing was performed

within 24 h postoperatively. If patients were reported to be

positive (tumor fraction ≥0.01%), early adjuvant therapy was

initiated within 72 h. Additionally, TME spatial mapping was used

to evaluate postoperative margins. If the number of CD8+

TILs were <100 cells/high-power field at the invasive margins,

high-risk areas were marked to guide postoperative RT target

design. At 4 weeks post-surgery, plasma ctDNA levels could be used

to assess the MRD status. If two consecutive tests exhibit negative

results, the adjuvant immunotherapy cycle may be shortened from the

standard 16 cycles to 8 cycles. Lastly, patients should undergo

regular soluble PD-L1 (sPD-L1) level testing every 3 months. If the

sPD-L1 level should increase by 2 times or more compared with

baseline values, the adjuvant therapy should be switched to a

combination of immunotherapy and anti-angiogenesis treatment [since

the increase in the sPD-L1 level is notably associated with

increased levels of VEGF in the TME (97)].

Progress in immunotherapy combined with

other treatments

The combined strategy of perioperative immunotherapy

should balance efficacy and safety, particularly considering the

impact of treatment on surgical feasibility, postoperative recovery

and long-term survival. The following section combines the latest

clinical studies to explore the potential and challenges of

different combined modes in perioperative therapy. Immunotherapy

with dual checkpoint inhibitors, via simultaneously blocking

multiple immune suppression pathways, including the PD-1/PD-L1 and

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) pathways,

enhances the antitumor immune response, thereby helping to overcome

drug resistance to a certain extent. This strategy has been

validated in each of the Checkmate 227, Checkmate 568 and Checkmate

817 trials for its efficacy and safety in advanced NSCLC (10,98–100)

and its application in perioperative care is currently being

actively explored.

In the NEOpredict-Lung study (101), patients who received nivolumab

plus relatlimab as neoadjuvant therapy had an MPR rate of 30% and a

pCR rate of 17%. Patients in the PD-L1 ≥50% subgroup demonstrated

both a further pathological remission and a lower proportion of

residual tumor cells. By contrast, in the CheckMate 816 study, the

MPR rate for patients receiving neoadjuvant nivolumab plus

chemotherapy was only 35.4% and the pCR rate was 25.3% (13), demonstrating that the dual

immunotherapy regimen was able to achieve similar pathological

remission levels without chemotherapy. In the EAST ENERGY trial

(89), the dual immunotherapy

regimen demonstrated even more notable advantages, with an MPR rate

of 50% and a pCR rate of 25% for patients receiving neoadjuvant

pembrolizumab plus ramucirumab. Additionally, the dual

immunotherapy regimen also demonstrated promising results in terms

of surgical feasibility. In the NEOpredict-Lung study, patients who

received nivolumab plus relatlimab as neoadjuvant therapy achieved

a 100% surgical completion rate and a 95% R0 resection rate, with

no delays due to treatment toxicity. By contrast, in the CheckMate

77T study, the surgical completion rate for patients receiving

neoadjuvant nivolumab combined with chemotherapy was only 77.7% and

certain patients required adjustments to their surgical plans due

to bone marrow suppression.

Regarding the safety of the dual immunotherapy

regimen, in the NEOpredict-Lung trial, patients receiving nivolumab

plus relatlimab neoadjuvant therapy were reported to have only a

13% incidence of TRAEs of grade 3 or higher and experienced no

chemotherapy-associated toxicities (such as neutropenia).

Additionally, irAEs were mainly associated with thyroid

dysfunction, with a 40% incidence rate in the dual immunotherapy

group and rare serious events, such as pneumonia, which occurred in

<2% of cases. By contrast, in the CheckMate 77T study, the

incidence of TRAEs of grade 3 or higher was as high as 32.5%,

accompanied by notable chemotherapy-associated toxicities,

including a 10.1% incidence of neutropenia. Although the dual

immunotherapy regimen was associated with higher levels of

pathological remission in the PD-L1 level ≥50% group, it still

provided notable benefits to patients with PD-L1 levels <1%; for

example, in the NEOpredict-Lung study, the MPR rate for patients

with PD-L1 levels <1% was 16.7%. Overall, the dual immunotherapy

regimen avoids the risks of bone marrow suppression and

gastrointestinal toxicity associated with chemotherapy, reduces the

risk of postoperative infections and delayed recovery and is

particularly suitable for elderly or poorly tolerated patients.

Furthermore, the EAST ENERGY study demonstrated that

blocking ramucirumab with VEGFR-2 antagonists led to a reshaping of

the TME, an enhancement of CD8+ T-cell infiltration and

a prolongation of the duration of the immune response. However, the

double immunization regimen still needs to be investigated in phase

III trials for the purpose of directly comparing the double

immunization regimen with the combination of chemotherapy and

immunotherapy to further clarify its advantages (10,102).

At present, although no separate studies have been

published on perioperative immunotherapy combined with targeted

therapy for lung cancer, a potential synergistic antitumor

mechanism exists between immunotherapy and targeted therapy. The

MARIPOSA-2 study (103) evaluated

the efficacy of the EGFR-mesenchymal/epithelial transition factor

(MET) bispecific antibody amivantamab in combination with

chemotherapy and lazertinib in patients with advanced EGFR-mutated

NSCLC. The results demonstrated that the median PFS in the combined

treatment group reached 8.3 months, the median intracranial PFS was

12.8 months and the ORR was 63%. This data demonstrates that

amivantamab combined with targeted therapy and chemotherapy has

notable efficacy in treating advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC,

suggesting the translational potential of immunotherapy combined

with targeted therapy in perioperative lung cancer treatment. In

particular, the enhanced intracranial activity of lazertinib may

prevent occult brain metastasis progression during surgery; in

addition, lazertinib inhibits the EGFR signaling pathway, thereby

reducing the levels of immune-suppressive cytokines such as IL-6

and VEGF, which has the effects of improving the TME and enhancing

the synergistic effect with immunotherapy. Furthermore, the

CheckMate 370 (104) and TATTON

(105) studies also explored the

potential of immunotherapy in combination with targeted therapy in

advanced NSCLC and the results obtained from these studies also

have the potential to be applied to perioperative immunotherapy in

lung cancer in the future.

Furthermore, novel immunomodulators target

non-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoints to modulate key signaling

pathways in the TME, thereby offering a novel direction for

perioperative immunotherapy. The NeoTRACK study (106) explored the use of atezolizumab in

combination with the novel T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM

domains (TIGIT) inhibitor, tiragolimab, during perioperative care.

Tiragolimab is a novel monoclonal antibody that targets the TIGIT

receptor, which functions as an inhibitory immune checkpoint

receptor primarily expressed on the surface of activated T and NK

cells. By binding to the ligand CD155, which is highly expressed on

the surface of tumor and antigen-presenting cells, TIGIT transmits

inhibitory signals, leading to T-cell exhaustion and NK cell

dysfunction. However, a synergistic inhibitory effect also exists

between TIGIT and the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Blocking TIGIT helps

relieve the dual inhibition of T cells and NK cells, thereby

enhancing the antitumor immune response. In models of PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitor resistance, TIGIT inhibition has been reported to restore

the function of exhausted T cells, thereby overcoming immune

escape. This research is currently ongoing (106) and may potentially lead to

applications in perioperative immunotherapy for lung cancer in the

future.

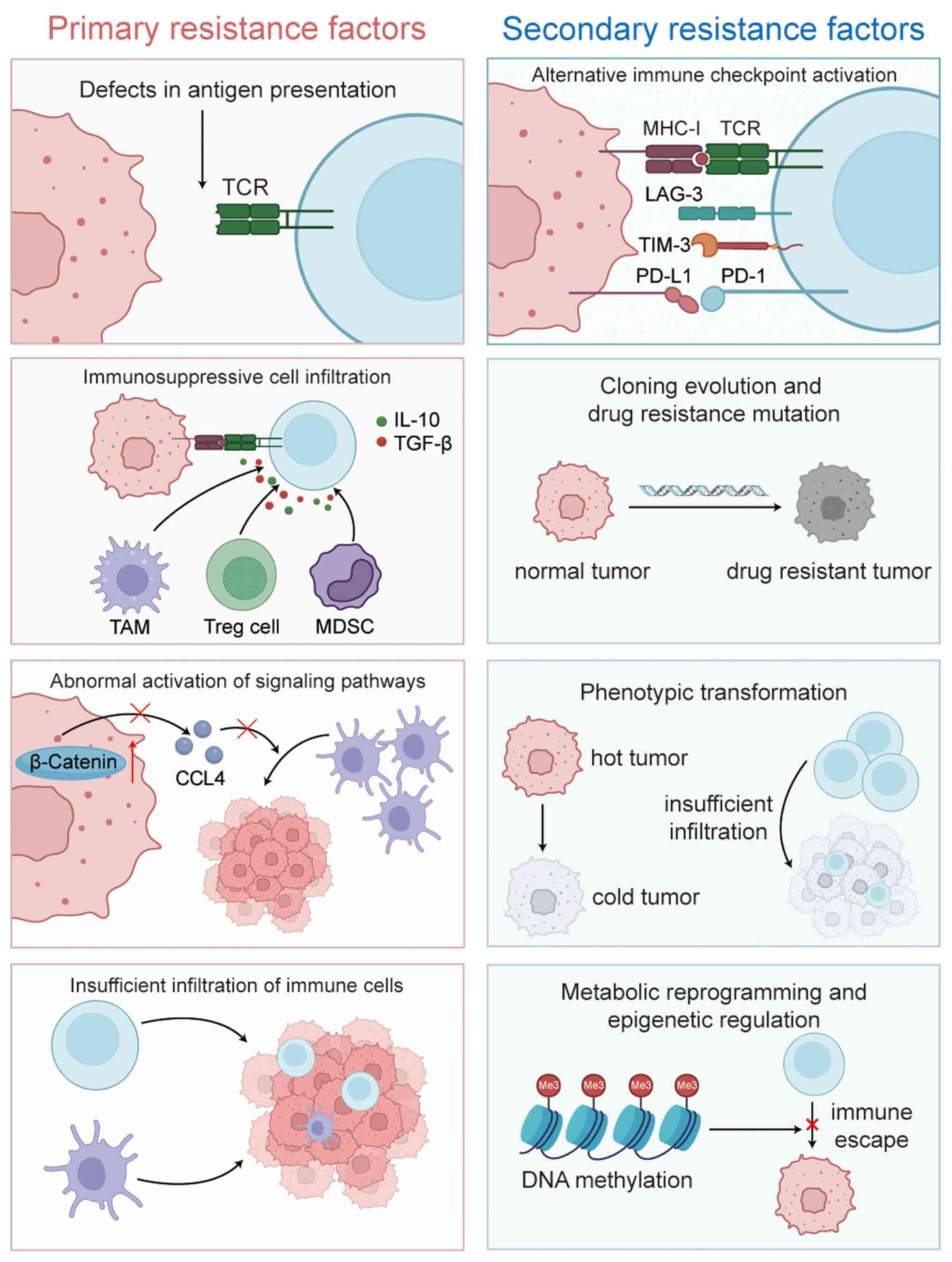

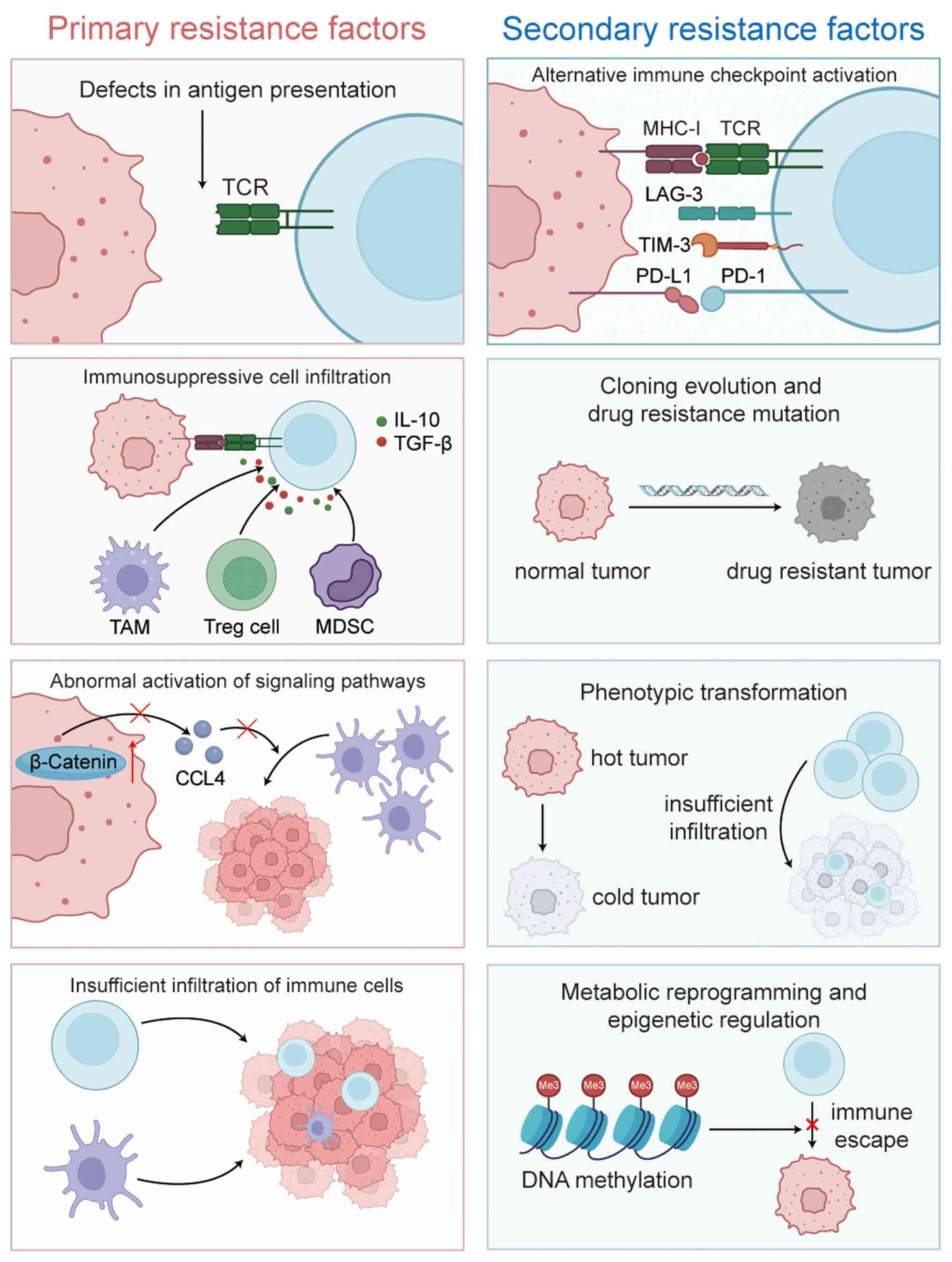

Resistance

Although perioperative immunotherapy for lung cancer

has been reported to be effective and safe in the aforementioned

clinical trials, long-term resistance to immunotherapy remains a

notable concern, particularly for patients requiring postoperative

adjuvant immunotherapy. Generally, the mechanisms of immunotherapy

resistance can be categorized into primary and secondary modes of

resistance. The core of primary drug resistance lies in the ‘cold’

nature of the TME, characterized by insufficient immune cell

infiltration. This is primarily due to disordered tumor vascular

structures and defects in the secretion of chemokines such as

CXCL9/10, which prevent CD8+ T cells from effectively

infiltrating the tumor. Additionally, mutations or epigenetic

silencing in genes associated with antigen presentation, such as

β-2 microglobulin and transporter associated with antigen