Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) remains one of the most common

and lethal malignancies worldwide, with persistently high incidence

and mortality rates. According to recent global statistics,

>960,000 new GC cases are diagnosed annually and as estimated in

2024, ~660,000 mortalities occur annually, with men representing

the majority of cases (1). In

China, GC morbidity and mortality also poses a major public health

burden (2); although incidence has

declined moderately across the past decades, this trend is

geographically uneven and population growth may drive an increase

in GC mortalities by 2035 (3). The

development of GC is a complex multistep process, where immune

escape mechanisms serve a major role. Tumor cells can downregulate

antigen expression to escape immune detection, activate

immunosuppressive pathways and recruit suppressive cell populations

to favor growth and metastasis. These methods disarm innate and

adaptive immunity as well as reduce the efficiency of

immunotherapeutics, including immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)

and adoptive cell therapies (4).

The tumor microenvironment (TME) consists of

non-malignant cells and secreted factors which further sustain and

promote GC progression. During early-stage tumor development, the

TME plays a crucial role in inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis

by activating immune cells and enhancing antitumor immune

responses. However, as tumors develop, the TME transforms into an

immunosuppressive niche that further facilitates tumor growth,

metastasis and immune tolerance (5). In GC, the TME provides nutrients and

structural support to tumor cells and, through complex, multi-level

interactions, establishes an immunosuppressive network that impairs

effector immune function and shifts responses toward tolerance

(6).

Immune tolerance refers to natural mechanisms that

maintain the immune system in a state of unresponsiveness or

hyporesponsiveness, thereby preventing autoimmune disease

development and excessive inflammation (7). In cancer, the TME enhances these

mechanisms to inhibit T-cell responses against tumor cells by

increasing regulatory T-cell (Tregs) levels, secreting TGF-β and

IL-10 and upregulating programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). This

creates a tumor-specific immune-tolerant state that induces

effector T-cell exhaustion or apoptosis, markedly impairing immune

clearance (8). Beyond evading

immune surveillance, tumor cells actively acquire immune escape

capabilities through gene mutations, epigenetic alterations and

microenvironmental remodeling (9).

These interconnected processes drive GC progression and influence

immunotherapy outcomes.

Consequently, monotherapies using ICIs or chimeric

antigen receptor T-cells (CAR-T) show limited efficacy in GC, as

some patients develop primary or acquired resistance. However,

these mechanisms may identify clear targets for combination

strategies aimed at TME remodeling (10,11).

The role of the TME in immune escape has attracted

recent attention. A study conducted by He et al (12) demonstrated that stromal modulation

by the tubulin-binding anticancer drugs combretastatin A4 and

eribulin improved tumor perfusion and antitumor immunity. This was

achieved in a tumor mouse model by restoring highly proliferative,

angiogenic pericytes to a quiescent, contractile state, thereby

continuously normalizing the vascular bed and reducing hypoxia. In

addition, Wang et al (13)

explored the role of phosphodiesterase type 5A (PDE5A) in

cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in shaping an

immunosuppressive TME in GC. The findings identified PDE5A in CAFs

as a key factor influencing TME alterations, such as T cell

exclusion and reduced infiltration of CD8+ cytotoxic T

lymphocytes, which may undermine the effectiveness of GC

immunotherapy. These insights provide both mechanistic

understanding and potential therapeutic implications for improving

GC immunotherapy. Shaibu et al (14) explored how mesenchymal stem cells,

cytokines and ICIs collectively contribute to the formation of an

immunosuppressive GC TME. The study revealed that mesenchymal stem

cells secrete cytokines, including IL-6, TGF-β and IL-10, which

contribute to an immunosuppressive environment, thereby

facilitating tumor progression, immune evasion and resistance to

treatment.

While involvement of the TME in immune escape has

been investigated in the aforementioned studies, the mechanisms

underlying GC immune tolerance remain poorly understood.

Specifically, the roles of cytokines, immune checkpoints and

epigenetic regulation within the TME in driving GC immune tolerance

are not well defined. The present review aimed to address this

knowledge gap, summarizing the role of the TME in GC immune escape

(as reported in the literature) and the mechanisms underpinning GC

immune tolerance. It further explores how immune cells, cytokines

and epigenetic alterations within the TME mediate immune tolerance

and influence immunotherapy efficacy.

In addition, the present review details progress in

overcoming GC immune tolerance and describes innovative

immunotherapeutic strategies for TME remodeling. For example,

emerging ICIs, cell therapies and immunotherapies targeting the

activity of immune cells within the TME represent promising avenues

for future GC immunotherapies.

Composition of the GC TME: The cornerstone

of immune suppression

Cellular components

GC TMEs constitute a complex ecosystem of cellular

and non-cellular components that collectively govern tumor

initiation, progression and immune escape.

Tumor cells

As the central drivers of the TME, tumor cells shape

an immunosuppressive environment through multidimensional

mechanisms. These cells reprogram the TME from an initial antitumor

state to one that favors tumor progression and immune evasion

(15). For example, tumor cells

upregulate PD-L1, which binds to programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1) on T-cells, to inhibit their activation and effector

functions (16). Furthermore, the

IKAROS family zinc finger 4/non-POU domain-containing

octamer-binding-RAB11 family interacting protein 3 axis reinforces

PD-L1 recycling and surface expression, further suppressing

antitumor immune responses (17).

GC cells also frequently exhibit hypermethylation of the

β2-microglobulin promoter and loss of the transcription factor NLR

family CARD domain containing 5. These alterations inhibit the

synthesis and trafficking of major histocompatibility complex class

I (MHC-I) molecules, hindering effective antigen presentation to

CD8+ T-cells (18).

Zhang et al (19)

demonstrated that tumor cells reprogram neutrophil glucose

metabolism to induce a pro-tumor N2 phenotype and deliver exosomal

microRNA (miR)-4745-5p/miR-3911 to downregulate slit guidance

ligand 2, thereby promoting GC metastasis. This metabolic rewiring

not only sustains tumor growth but also impairs immune cell

function. Antigenic stimulation and metabolic stress drive T-cell

exhaustion, characterized by the co-expression of numerous immune

checkpoints and reduced cytokine secretion. These changes lead to

permanent immune tolerance (20,21).

Immune cells

Immune cells within the TME are key mediators of

immunosuppression and immune escape in GC. Tumor-associated

macrophages (TAMs) secrete IL-10 and TGF-β and express PD-L1 to

inhibit T-cell function. This subsequently suppresses T-cell

activity within the TME, promotes immune escape and is further

reinforced through PI3K-AKT signaling (22,23).

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), recruited through

IL-17/NF-κB/RELB proto-oncogene, NF-kB subunit signaling, adopt a

pro-tumor N2 phenotype and upregulate PD-L1, aiding tumor cells in

evading immune attack (24).

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) impair the functions of

cytotoxic T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells, facilitating tumor

immune escape (4). Tregs express

forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) and secrete IL-10 within the TME to

suppress effector T-cells, maintain tolerance and drive immune

escape (25). Although NK cells can

recruit CD8+ T-cells through the C-C motif chemokine

ligand (CCL)-3/CCL4/C-C motif chemokine receptor (CCR)-5 axis to

enhance antitumor responses, their cytotoxic activity is often

diminished by the immunosuppressive environment (26).

CAFs

As the predominant stromal cells in the GC TME, CAFs

regulate immunosuppression through a number of signaling axes,

including the TGF-β, IL-6/JAK/STAT and CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling axes.

In GC, CAFs (derived from mesenchymal cells) exhibit high

heterogeneity in their origin, phenotype and function (27), secreting key factors that impair

antitumor components of the immune system.

TGF-β promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT) through the canonical TGF-β/SMAD signaling cascade, enhancing

tumor invasion and dissemination. It also activates STAT3

signaling, a pathway involved in recruiting and polarizing M2

macrophages and Tregs (28). IL-6

sustains a cancer stem-like state through Janus kinase

(JAK)-2/STAT3 activation and impairs dendritic cell (DC) maturation

and antigen presentation, thereby blocking effector T-cell

activation (29). C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand (CXCL)-12 binds to C-X-C motif chemokine receptor

4 on immune cells to recruit Tregs and MDSCs, reinforcing the

immunosuppressive network (30).

Metabolically, CAFs provide tumor cells with substrates, including

lactate, ketone bodies and glutamine through autophagy and aerobic

glycolysis. Meanwhile, tumor-derived by-products exacerbate hypoxia

and nutrient deprivation, inducing metabolic stress in immune cells

and facilitating immune escape (31). Furthermore, increased CAF glycolysis

produces more lactate which both directly damages T-cell metabolism

and cytotoxicity, as well as acidifies the TME to facilitate MDSC

recruitment and activation (32).

Endothelial cells

Endothelial cells in the GC TME enable immune

evasion through abnormal angiogenesis and immunomodulation. GC

cells secrete exosomes and growth factors that activate endothelial

cells to initiate neovascularization (33). In hypoxic environments, tumor

endothelial cells promote an immunosuppressive environment by

upregulating von Willebrand factor and hypoxia-inducible factor

(HIF)-2α (34). Tumor-associated

endothelial cells weaken antitumor immunity by directly inhibiting

T-cell activity through expressing immune checkpoints including

PD-L1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4)

(35). Endothelial cells also

suppress the effector functions of T-cells, NK cells and DCs

through cytokine secretion (36). A

study demonstrated that endothelial-derived chemokines, including

IL-8 and CXCL1, selectively recruit immunosuppressive neutrophils

to perivascular regions, further reinforcing the local

immunosuppressive environment (37). Notably, endothelial cells and CAFs

engage in reciprocal interactions through the Notch signaling

pathway, cooperatively driving vascular abnormalities and

maintaining the immune barrier (38).

Non-cellular components

Extracellular matrix (ECM)

ECM, the primary non-cellular component of the GC

TME, contributes to establishing an immunosuppressive environment.

GC-associated ECM is heterogeneous and undergoes dynamic

remodeling, which modulates tumor cell proliferation, migration and

invasion, as well as immune cell infiltration and function

(39). Sustained stimulation by

CAFs triggers extensive fibrotic remodeling of the GC ECM whereby

the dense structure transmits mechanical stress to tumor and immune

cells, disrupting the T-cell cytoskeleton and impairing motility

(40,41).

The ECM serves an important role in

immunosuppression through a number of mechanisms. For example,

excessive ECM deposition elevates interstitial fluid pressure,

which restricts immune cell infiltration and drug penetration. In

addition, specific ECM components including serpin family E member

1 and collagen IV-α1 enhance immune tolerance and tumor progression

by upregulating TGF-β1 and matrix metalloproteinases (42,43).

The stiffness and porosity of the ECM also regulates cancer and

stromal cell behavior. Increased matrix stiffness activates

intracellular mechanotransduction pathways to enhance tumor cell

proliferation and survival, induce EMT and enhance invasion and

metastasis (44).

Soluble factors

Soluble factors including cytokines, chemokines,

growth factors and metabolites, collectively drive GC progression

and immune evasion by modulating immune cell function, promoting

tumor growth and metastasis and remodeling the stromal compartment.

Among these, IL-6 and TGF-β are key immunosuppressive cytokines.

IL-6 activates the JAK/STAT3 pathway to promote tumor cell

proliferation and survival while inhibiting CD8+ T-cell

function (45). TGF-β exacerbates

immunosuppression by inducing Treg differentiation and suppressing

effector T-cell activity (46).

The chemokine network orchestrates immune cell

recruitment. CCL2 recruits M2 TAMs, CXCL12 attracts Tregs and MDSCs

and CXCL8 (also known as IL-8) recruits neutrophils, together

establishing an immunosuppressive cellular microenvironment

(47). Growth factors, particularly

vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), not only drive

angiogenesis but also impair DC maturation and function, thereby

weakening antitumor immunity (48).

Metabolites further reinforce immunosuppression in

the GC TME. For example, lactate produced by tumor glycolysis

lowers extracellular pH, inhibiting the function of T-cells and NK

cells while promoting Treg and MDSC activity (49). Similarly, adenosine activates the

A2A receptor to suppress effector T-cell responses and facilitate

Treg differentiation (50).

Physicochemical conditions

Physicochemical properties of GC TMEs are markedly

dysregulated, contributing to immunosuppression by altering immune

cell metabolism and function. Acidification, primarily driven by

lactic acid accumulation from tumor glycolysis, directly impairs

T-cell and NK cell activity, diminishing antigen presentation and

cytokine secretion to weaken antitumor immunity. Moreover, acidic

conditions polarize TAMs toward an M2 phenotype, further

reinforcing immunosuppression (49). Hypoxia, resulting from aberrant

angiogenesis and inadequate perfusion, promotes tumor cell

survival, invasion and metastasis through HIF-1α signaling, while

also facilitating the recruitment and activation of

immunosuppressive cells (51).

Elevated interstitial fluid pressure, a key component of the TME,

impedes immune cell infiltration into the tumor core, confining

effector cells to the periphery and limiting their cytotoxic

capacity (52).

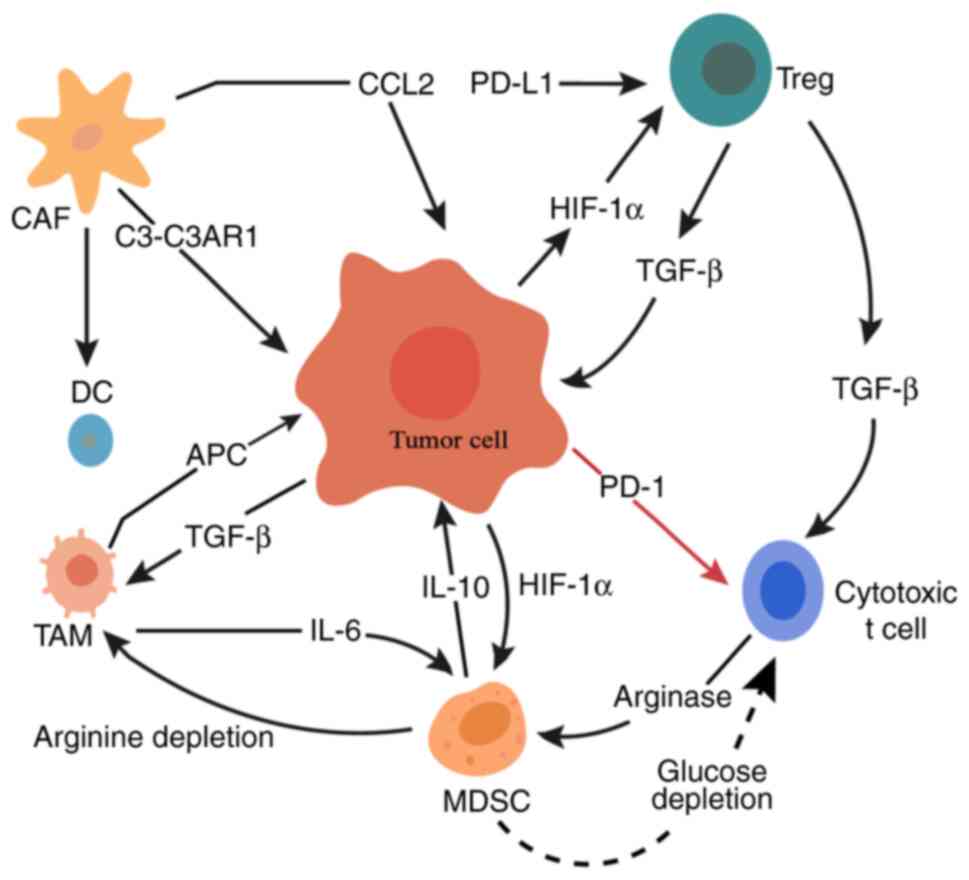

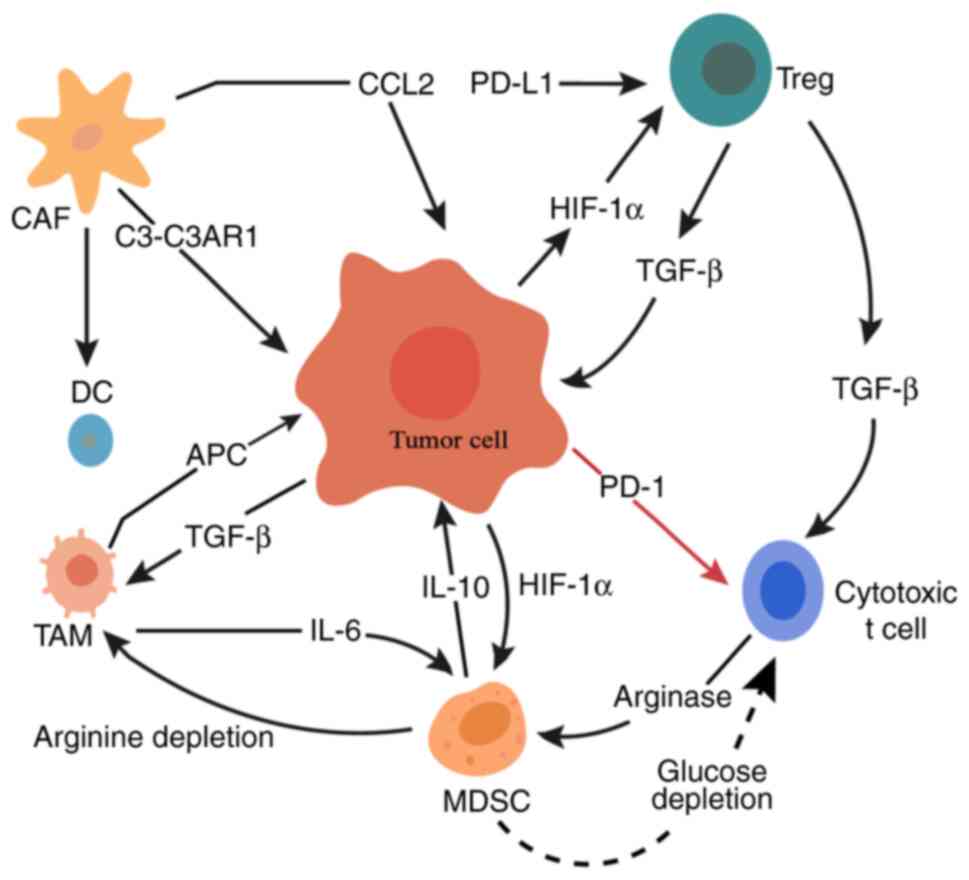

In summary, the GC TME represents a heterogeneous

‘ecosystem’ in which cellular and non-cellular components interact

to establish an immunosuppressive network (Fig. 1). Table

I summarizes the principal components of the GC TME and their

key immunosuppressive mechanisms, providing a framework for

subsequent analyses and therapeutic strategy design.

| Figure 1.Schematic diagram of immune

regulatory mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment of gastric

cancer. MDSCs suppress the activity of immune effector cells

through metabolic pathways. This leads to increased immune energy

depletion and enhanced immunosuppression within the tumor

microenvironment. The red arrow indicates inhibition, the black

arrows indicate promotion, and the dotted arrow represents indirect

metabolic signaling. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; CAF,

cancer-associated fibroblast; DC, dendritic cell; C3-C3AR1,

complement C3-complement C3a receptor 1; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine

ligand 2; APC, antigen-presenting cell; TAM, tumor-associated

macrophage; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; PD-1, programmed

cell death protein 1; Treg, regulatory T-cell; PD-L1, programmed

death-ligand 1. |

| Table I.Major cellular and non-cellular

components of the GC TME and their immunosuppressive

mechanisms. |

Table I.

Major cellular and non-cellular

components of the GC TME and their immunosuppressive

mechanisms.

| Component | Key factors and

pathways | Mechanisms of

immune suppression and impact |

|---|

| Tumor cells | PD-L1/PD-1

pathway | Inhibit T-cell

activation, impair antigen presentation and |

|

|

IKZF4/NONO-RAB11FIP3 axis | induce immune

tolerance and stress in immune cells |

|

| β2-microglobulin

hypermethylation |

|

|

| NLRC5 loss |

|

|

| Metabolic

reprogramming |

|

| Immune cells | IL-10 | Suppress T-cell

function, maintain immune tolerance and |

|

| TGF-β | promote immune

escape |

|

| PD-L1 |

|

|

| IL-17/NF-κB/RelB

signaling |

|

|

| PI3K-AKT

pathway |

|

|

| FOXP3 |

|

|

| CCL3/CCL4-CCR5

axis |

|

|

Cancer-associated | TGF-β/SMAD

signaling | Promote tumor

invasion, inhibit T-cell activation and |

| fibroblasts | IL-6/JAK2/STAT3

signaling | increase metabolic

stress, |

|

| CXCL12/CXCR4 | aiding immune

escape |

|

| Autophagy |

|

|

| Aerobic

glycolysis |

|

| Endothelial

cells | HIF-2α | Inhibit T-cell and

NK-cell activity, recruit |

|

| Von Willebrand

factor | immunosuppressive

cells and maintain immune barrier |

|

| PD-L1 and

CTLA-4 |

|

|

| IL-8 and CXCL1 |

|

|

| Notch

signaling |

|

| Extracellular

matrix | SERPINE1 | Restrict immune

cell access, enhance tumor progression |

|

| COL4A1 | and limit drug

penetration |

|

| TGF-β1 |

|

|

| MMPs |

|

|

| ECM stiffness and

porosity |

|

| Soluble

factors | IL-6 | Inhibit T-cell

function, recruit immunosuppressive cells |

|

| TGF-β | and impair immune

responses |

|

| CCL2 |

|

|

| CXCL12 |

|

|

| CXCL8 (IL-8) |

|

|

| VEGF |

|

|

| Lactate |

|

|

| Adenosine |

|

|

Physicochemical | Lactic acid | Inhibit T-cell and

NK cell activity, promote tumor survival |

| conditions | HIF-1α | and limit immune

cell infiltration |

|

| Interstitial fluid

pressure |

|

Molecular mechanisms of immune

tolerance

Impairment of antigen presentation and

recognition

GC cells employ multiple strategies to downregulate

MHC-I expression, which hampers the presentation of

tumor-associated antigens to CD8+ T-cells, facilitating

immune evasion (53). Concurrently,

persistent hypoxia in the TME increases HIF-1α levels. HIF-1α

inhibits the function of antigen-processing enzymes and impairs

peptide loading onto MHC-I molecules (54,55).

In addition, the DCs within the TME exhibit limited maturation and

activation, reduced expression of costimulatory molecules

(CD80/CD86) and impaired antigen uptake and processing. This

deprives T-cells of adequate activation molecules, namely signal II

and signal III cytokines. This dual impairment markedly reduces the

primary T-cell response, establishing an initial barrier to

antitumor immunity and promoting immune tolerance (56,57).

Activation of immune checkpoint

signaling

Immune checkpoints act as key negative regulators of

T-cell activity. In GC, PD-L1s on tumor cells bind to PD-1 on

T-cells, recruiting the Src homology-2 protein tyrosine

phosphatase, blocking the PI3K/AKT pathway, reducing T-cell

metabolism, impairing cytotoxicity and promoting cell cycle arrest

(58). CTLA-4, also upregulated in

the GC microenvironment, has a higher affinity for CD80/CD86

compared with CD28, thus inhibiting costimulatory signals and

suppressing naive T-cell activation and proliferation (59).

Furthermore, CD8+ T-cells infiltrating GC

upregulate both T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM-3).

The interaction of galectin-9 with its ligand (TIM-3) induces the

apoptosis of T-cells and also exacerbates T-cell exhaustion,

sustaining an immunosuppressive microenvironment, even in the

context of PD-1 blockade, thus driving therapeutic resistance

(60).

Immunosuppressive cytokines and

receptor networks

Inhibitory cytokines within the GC TME establish an

autocrine-paracrine suppressive network. TGF-β directly inhibits

the proliferation and cytokine secretion of effector T-cells. In

addition, TGF-β drives the differentiation of naive CD4+

T-cells into Tregs by upregulating FOXP3 (61). IL-10 activates STAT3 to polarize DCs

and macrophages toward a tolerogenic phenotype. It also reduces the

production of proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-12 and TNF-α),

thereby suppressing effector T-cell activation (62). VEGF impairs DC maturation through

VEGFR-2 and reduces antigen presentation, further downregulating

endothelial adhesion molecules, restricting the infiltration of

CD8+ T cells and NK cells into the tumor parenchyma

(63,64).

Metabolic reprogramming-mediated

immune suppression

GC cells and tumor-associated DCs upregulate

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase, which

catalyze the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine (Kyn).

Accumulated Kyn engages the aryl hydrocarbon receptor to drive

naive T-cell differentiation into Tregs, establishing an

immunosuppressive environment (65,66).

Arginase 1 (ARG1), abundant in TAMs and MDSCs, depletes arginine,

downregulates the CD3ζ chain expression and attenuates T-cell

receptor (TCR) signaling and cytotoxicity (67). Lipid droplets accumulate in TAMs and

tumor cells, generating oxidized lipids that activate the NOD-like

receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 inflammasome through endoplasmic

reticulum stress or reactive oxygen species (ROS), further

reinforcing immunosuppression (68). Furthermore, excess cholesterol and

its derivatives (such as bile acids, steroid hormones and

oxysterols) bind to fatty acid-binding proteins in Tregs and MDSCs,

regulating their lipid metabolism to enhance survival and

suppressive function (69).

Epigenetic and transcriptional

regulation

GC cells utilize DNA methyltransferases and enhancer

of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) to silence proinflammatory genes (such as

IFN-γ and TNF-α) while upregulating immunosuppressive loci

(70,71). In T-cells, epigenetic modifications

govern the balance between exhaustion and memory phenotypes

(72). In TAMs, the downregulation

of miR-155 relieves the repression of suppressor of cytokine

signaling 1, limiting M1 polarization, as restoring miR-155

reinstates M1 characteristics and enhances antitumor inflammatory

responses (73,74). In addition, the long non-coding RNA

PVT1 binds to EZH2 to prevent its degradation, sustaining the

histone H3 lysine 27 trimethyltransferase activity of EZH2 in

Tregs. This upregulates FOXP3 expression, preserving Treg-mediated

immunosuppression (75,76).

Information transfer mediated by

exosomes and microvesicles

Exosomes secreted by tumor cells carry miR-21, which

targets antigen presentation transcription factors and MHC class II

(MHC-II) molecules in DCs. This interaction impairs DC maturation

and antigen presentation capabilities, thereby suppressing the

activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells (77). Tumor-derived exosomes (TDEs) can

accumulate in distant organs and modulate the local TME, promoting

immunosuppressive stromal remodeling and establishing a

pre-metastatic niche conducive to tumor cell colonization (78). A study has shown that inhibiting the

expression of neutral sphingomyelinase 2 or Ras-related protein

Rab27a, markedly reduces exosome production and secretion, thereby

enhancing immune cell function and improving the efficacy of

antitumor therapies (79).

Infiltration and interaction of

immunosuppressive cells

CCL17 and CCL22 are chemokines highly expressed in

the GC TME, which serve key roles in shaping the tumor immune

microenvironment (80). In patients

with GC, MDSC levels are notably elevated, as these cells

overexpress ARG1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; which

produces reactive nitrogen species). This depletion of arginine in

the TME hinders the proliferation of effector T-cells and reduces

the expression of the TCR ζ-chain (81).

Macrophages undergo M2 polarization in response to

colony stimulating factor (CSF)-1/CSF-1R and IL-4/IL-13 signals.

M2-polarized TAMs secrete CCL18 and activate the ERK1/2-NF-κB

pathway to promote tumor cell invasion. Concurrently, M2 TAMs

upregulate VEGF-A, which drives aberrant angiogenesis and impedes

effector T-cell infiltration (82,83).

Overall, these molecular mechanisms of immune

tolerance involve numerous pathways, including impaired antigen

presentation, immune checkpoint activation, cytokine signaling,

metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic regulation, exosomal transfer

and immunosuppressive cell infiltration. These mechanisms act both

independently and collaboratively through cross-regulatory

networks, collectively forming the molecular basis for GC immune

escape.

Core immune cells driving immune tolerance

in the GC TME and their interactions

MDSCs

MDSCs are key immune regulators that induce immune

tolerance in the TME. Under physiological conditions, MDSCs

differentiate into macrophages, granulocytes or DCs upon

maturation. However, persistent inflammatory cues in the TME

prevent their own differentiation into mature cells and promote

their expansion. As a result, MDSCs subvert T-cell function through

increased accumulation in local tumor tissue and peripheral

circulation (84).

MDSCs suppress antitumor immune responses through a

number of mechanisms. These cells produce high levels of ROS and

excessive peroxynitrite, which oxidize and nitrate T-cell surface

receptors and co-stimulatory molecules, directly impairing T-cell

recognition and cytotoxic functions (85,86).

Additionally, MDSCs secrete immunosuppressive enzymes including

ARG1 and iNOS, further inhibiting T-cell function and weakening

antitumor immunity (87). In GC,

MDSC accumulation is markedly associated with CD8+

T-cell dysfunction, facilitating tumor progression. These cells

suppress CD8+ T-cell activity and proliferation either

through direct cell-cell interactions or through releasing

inhibitory factors (88). MDSCs

also exacerbate immunosuppression by promoting the increase of

Tregs (89). Tumor cells recruit

MDSCs into the TME through TDEs or chemokines including CXCL12 and

CXCL5. Notably, miR-107 secreted by GC cells is transferred to

MDSCs through exosomes, where it downregulates the expression of

the dicer 1, ribonuclease III gene as well as phosphatase and

tensin homolog. This promotes the increase and activation of MDSC,

intensifying immunosuppression within the TME (90). Furthermore, in the GC TME, MDSC

accumulation is associated with elevated levels of inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α and IL-22. These cytokines not only

enhance MDSC recruitment and activation but also aggravate immune

suppression by inducing the differentiation of T helper (Th)-22 and

Th17 cells (91).

In summary, MDSCs serve a key role in promoting

immune tolerance in the GC TME by inhibiting T-cell function,

facilitating Treg recruitment and interacting with cytokines

amongst other immune cells.

TAMs

TAMs are among the most abundant immune cell types

in the TME. Their functional plasticity and interactions with other

cells markedly suppress antitumor immune responses and promote

tumor progression. TAMs are highly plastic, polarizing into

pro-inflammatory M1 or immunosuppressive M2 phenotypes. The

majority of M2-polarized TAMs in GC contribute to immune tolerance

by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines (including IL-10 and

TGF-β) and promoting Treg infiltration (92). Cytokines within the TME enhance Treg

recruitment and differentiation while inhibiting effector T-cell

function (93). M2 TAMs also

increase ARG1 levels, which deplete local arginine stores and

impair T-cell function (94).

Interactions between TAMs and other immune cells

further exacerbates immune tolerance in GC. TAMs promote Treg

activation and infiltration through TGF-β secretion, thereby

suppressing CD8+ T-cell activity. Additionally, the

CCL5-CCR5 signaling axis between TAMs and NK cells contribute to a

chemotherapy-induced immunosuppressive TME (95). TAMs also regulate MDSCs, as through

shared metabolic inhibitory pathways and cytokine networks

(including IL-6 and TGF-β), TAMs and MDSCs jointly consume key

nutrients for T-cell activation and cooperatively inhibit DC

maturation, leading to impaired antigen presentation and reduced

T-cell-mediated immunity (96,97).

In addition, TAMs directly suppress NK cell function by

downregulating NK group 2 member D receptor expression and

inhibiting the release of perforin and granzyme (through IL-10

secretion or human leukocyte antigen G expression), thereby

reducing NK cell cytotoxicity against GC cells (98). Notably, IL-10 and TGF-β secreted by

TAMs induce the differentiation of naive CD4+ T-cells

into FOXP3+ Tregs and support their functional

stability. Conversely, IL-35 secreted by Tregs further promotes TAM

polarization toward the immunosuppressive M2 phenotype,

establishing a TAM-Treg positive feedback loop that reinforces

immunosuppression (99,100).

In summary, TAMs in the GC TME orchestrate a complex

immunosuppressive network through synergistic interactions with

other immune cells and cytokines, ultimately hindering the

initiation of effective antitumor immune responses.

Tregs

Tregs serve a key role in maintaining immune

homeostasis by preventing autoimmunity. Within the GC TME, Tregs

employ multiple mechanisms to suppress immune attacks and support

tumor growth. Tregs upregulate CTLA-4, which competitively binds to

CD80/CD86 on effector T-cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs)

to block co-stimulatory signals. This inhibits CD8+

T-cell activation and proliferation (101). In addition, Tregs suppress

effector T-cell function through both the release of

immunosuppressive cytokines and direct cell-cell contact (102). Treg infiltration is associated

with GC progression and a poor prognosis. Tregs sustain an

immunosuppressive TME, supporting tumor cell proliferation,

invasion and metastasis (103).

Tregs also interact closely with other immune cells in the TME, as

they secrete TGF-β and other factors to polarize TAMs toward the M2

phenotype, enhancing immunosuppression (95). Tregs block DC maturation and antigen

presentation, hampering the initiation of antitumor immunity

(104). Tregs also secrete IL-10

and TGF-β, which weaken NK cell cytotoxicity and negatively

regulate NK cell-mediated tumor cell death (105).

Notably, studies have demonstrated a bidirectional

regulatory relationship between Tregs, MDSCs and TAMs. MDSCs

secrete chemokines such as CCL5 to recruit Tregs into tumor tissue.

In turn, TGF-β released by Tregs further enhances MDSC

differentiation into a suppressive state. These interactions

establish an immunosuppressive loop that reinforces immune

tolerance in the TME (84,106). Overall, Treg function is tailored

to the TME, enabling them to establish an efficient,

self-sustaining immunosuppressive network in the GC TME. Thus,

Tregs are key drivers of tumor immune tolerance.

DCs

As key APCs, DCs serve as important regulators of

immune responses within the TME. In GC, DC function is frequently

impaired, driving immune tolerance and promoting tumor progression

and metastasis. This dysfunction is closely linked to aberrant

activation of the PI3K/AKT and EMT signaling pathways. Notably,

these pathways not only enhance the immunosuppressive properties of

DCs but also facilitate tumor invasion and metastasis.

Metabolic dysregulation in the TME profoundly

modulates DC function, as dysregulated glucose metabolism

diminishes their antigen-presenting capacity, while abnormal lipid

metabolism promotes the development of an immunosuppressive DC

phenotype (107). Furthermore,

TDEs and immunosuppressive cytokines in the GC TME suppress DC

function through paracrine mechanisms. These factors impair DC

maturation while sustaining the proliferation of other

immunosuppressive cell populations (108,109).

Within the GC TME, DCs exhibit downregulated surface

expression of co-stimulatory molecules, as well as MHC-I and MHC-II

molecules, markedly reducing antigen presentation efficiency. This

leads to insufficient infiltration of tumor-specific

CD8+ T-cells and their subsequent dysfunction (110). In addition, aberrantly activated

plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) in GC tissues promote the expansion of

FOXP3+ Tregs through the inducible co-stimulator

(ICOS)-ligand/ICOS axis. High levels of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

secreted by pDCs further contribute to Treg induction and the

maintenance of their suppressive function (104,111).

Functional defects in DCs also impair NK cell

activity, as in the GC TME, DCs fail to adequately activate NK

cells, resulting in reduced antibody-dependent cellular

cytotoxicity and diminished tumor cell clearance (112).

Intercellular interactions in the

immune suppression network

In the GC TME, immunosuppressive cells do not act in

isolation. Instead, they cooperate through intricate intercellular

interactions and molecular signaling networks to establish a highly

integrated immunosuppressive system. A key mechanism underlying

this cooperation involves chemokine-receptor interactions, which

are key in recruiting and localizing inhibitory immune cells. Tumor

and stromal cells secrete large quantities of chemokines through

chemokine receptor-mediated pathways, facilitating the recruitment

of MDSCs, TAMs and Tregs to the tumor site (113,114).

For example, CAFs produce CCL2 to attract TAMs and

activate them through the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway (115). CAFs also recruit and polarize TAMs

through the complement C3 (C3)-complement C3a receptor 1 (C3AR1)

axis, helping to establish an immunosuppressive microenvironment

(116). Importantly, TAM-derived

TGF-β and IL-6 further sustain CAF activation, creating a positive

feedback loop that amplifies immunosuppression (117).

Beyond chemokine signaling, direct cell-cell

interactions, metabolic crosstalk and cytokine networks

collectively strengthen the suppressive microenvironment. Tregs

inhibit APCs by competitively binding to B7 molecules through

CTLA-4, blocking CD28-mediated co-stimulatory signaling. Tregs also

secrete TGF-β, which disrupts the metabolic reprogramming of

effector T-cells, leading to functional exhaustion and diminished

cytotoxicity (118,119). Lysosomal associated membrane

protein 3+ DCs interact with tumor-associated stromal

cells through the nectin cell adhesion molecule 2-T-cell

immunoglobulin and ITIM domain axis, suppressing CD8+

T-cell activity and promoting Treg enrichment to promote immune

tolerance (120).

MDSCs consume arginine through their arginase

activity, impairing T cell function. TAMs further enhance MDSC

recruitment and activation by consuming lipids released by tumor

cells (121,122). Tumor cells also engage in

metabolic competition to suppress immunity. Excess glucose

consumption by tumor cells (which exhibit a high glycolytic

phenotype) deprives infiltrating T-cells of energy, inducing their

functional exhaustion (123).

Meanwhile, the metabolic microenvironment sustains Treg survival

and suppressive capacity by regulating their fatty acid metabolism,

preserving their immunosuppressive phenotype (124).

Tumor cells actively shape the immunosuppressive

network by releasing signaling molecules, including VEGF,

prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and HIF-1α. VEGF inhibits DC

differentiation and maturation through VEGFR binding, reducing

antigen presentation and leading to the formation of a ‘cold’ tumor

microenvironment (125). Elevated

PGE2 levels upregulate p50, NF-κB and inhibitory gene expression in

MDSCs, enhancing their suppressive activity. PGE2 also promotes M2

polarization of TAMs, increasing the secretion of immunosuppressive

cytokines including IL-10 and TGF-β (126). HIF-1α directly binds to the

promoter region of the PD-L1 gene, inducing its expression in tumor

cells and MDSCs. Concurrently, HIF-1α upregulates chemokines such

as CCL28 and CXCL12, facilitating the selective recruitment of

Tregs and MDSCs to hypoxic tumor regions and intensifying

immunosuppression (127,128).

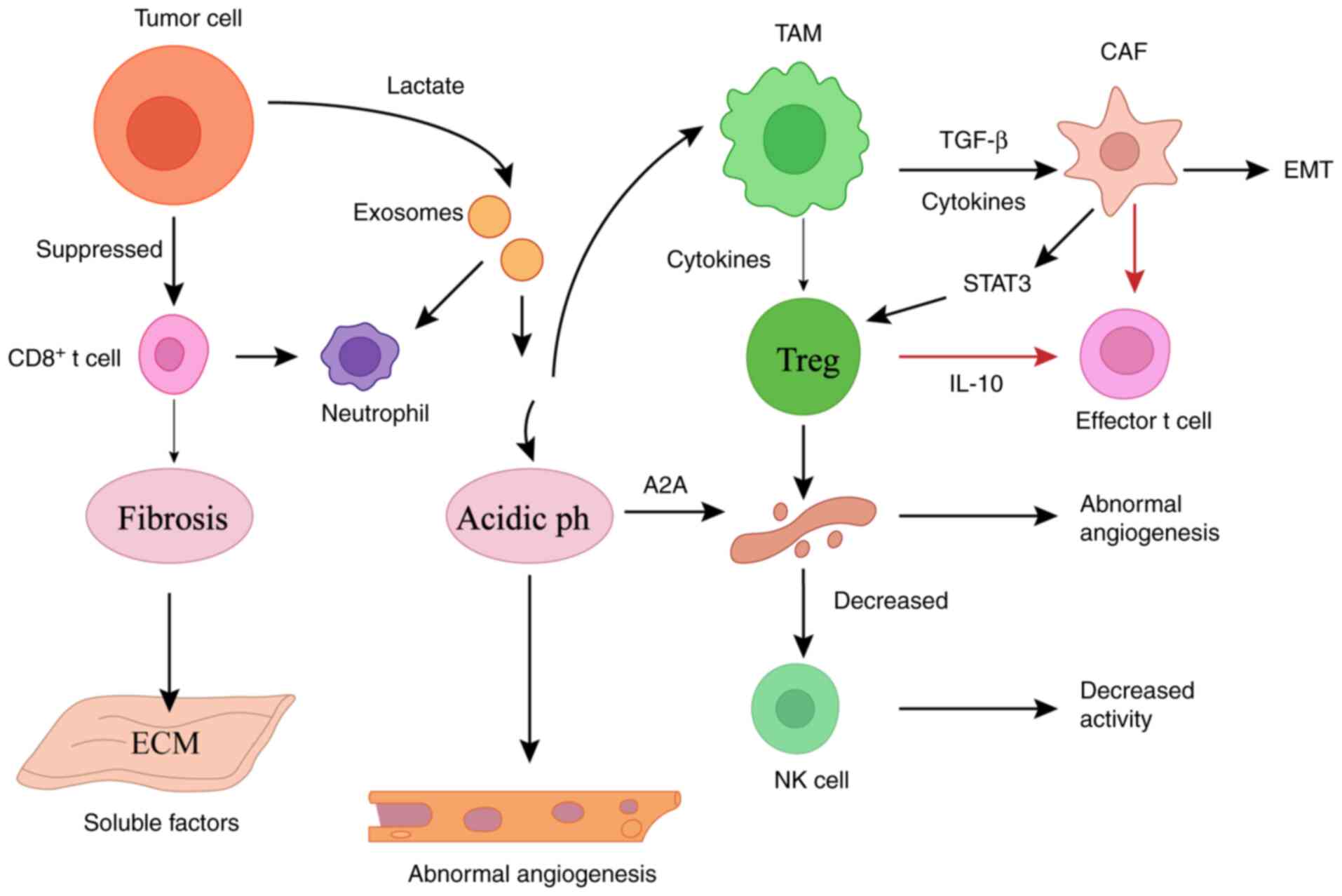

In summary, immune tolerance in the GC TME is not an

isolated trait of individual cells but rather a highly dynamic and

plastic inhibitory network established through complex interactions

among principal immune cell populations (Fig. 2).

Treatment strategies targeting immune

tolerance in the TME: Challenges and opportunities

ICIs

ICIs represent a transformative therapeutic strategy

that targets immunosuppressive mechanisms in the TME, reshaping

cancer treatment paradigms. PD-1, a co-inhibitory receptor that

binds to its ligand PD-L1, is frequently expressed on GC cells,

where it inhibits T-cell function to enable immune evasion. PD-1

inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab and camrelizumab) restore

T-cell function and alleviate the immunosuppressive state of the GC

TME (129,130).

CheckMate-649 (131) is a pivotal global phase III

clinical trial to assess the efficacy and safety of nivolumab

combined with chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients

with advanced GC, gastroesophageal junction cancer (GEJC) and

esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). The trial enrolled 1,581

treatment-naive patients with advanced or metastatic

non-HER2+ GC, GEJC or EAC, who were randomly assigned to

either the nivolumab + chemotherapy group or the chemotherapy-alone

group. Primary endpoints included overall survival (OS) and

progression-free survival (PFS), with secondary endpoints such as

health-related quality of life also assessed. The results showed

that nivolumab combined with chemotherapy notably prolonged both OS

and PFS, with more pronounced efficacy in patients with a PD-L1

combined positive score (CPS) ≥5.

KEYNOTE-062, a phase III trial, compared

pembrolizumab monotherapy, pembrolizumab + chemotherapy and

chemotherapy alone in patients with untreated advanced GC or

gastroesophageal junction (G/GEJ) cancer. In Asian patients,

pembrolizumab monotherapy resulted in a longer OS in those with a

PD-L1 CPS ≥1 (22.7 months) and CPS ≥10 (28.5 months), with

favorable tolerability (132).

Additional analyses of KEYNOTE-062 demonstrated that pembrolizumab

monotherapy was non-inferior compared with chemotherapy in patients

with untreated advanced GC/G/GEJ cancer and exhibited an improved

safety profile (133).

KEYNOTE-590 (134),

another important trial, primarily assessed pembrolizumab combined

with chemotherapy for esophagogastric junction tumors. Among

patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and a PD-L1

CPS ≥10, the median PFS and OS were 7.3 and 13.9 months,

respectively. In all patients with ESCC, these values were 6.3 and

12.6 months. These findings demonstrate that pembrolizumab combined

with chemotherapy markedly delays disease progression and improves

patient survival.

While ICIs have improved GC treatment, not all

patients derive benefit. Identifying appropriate patient

populations and developing more effective combination regimens to

broaden clinical benefit remain key challenges, largely due to

notable heterogeneity in treatment responses. PD-L1 has been used

as a biomarker to predict immunotherapy responses in clinical

trials, but its sensitivity and specificity remain unresolved.

Current research is also exploring inhibitors targeting other

immune co-inhibitory molecules, with the goal of overcoming the

limitations of single-agent therapies through multi-target

combination strategies. Furthermore, future studies should aim to

focus on overcoming tumor adaptive resistance through combination

strategies, such as pairing ICIs with TME remodeling

approaches.

Cell therapy

In recent years, CAR-T immunotherapy has emerged as

a promising advancement in cancer immunotherapy. CAR-T therapy

involves engineering T-cells to express a CAR, fusing a tumor

antigen-specific single-chain variable fragment with intracellular

activation domains, endowing T-cells with MHC-independent tumor

cell recognition and cytotoxic capacity.

CT041, a CAR-T therapy targeting Claudin18.2

(CLDN18.2), has shown promise in GC treatment. An ongoing phase I

trial (trial ID no. NCT03874897) is assessing the safety and

efficacy of CT041 in patients with CLDN18.2-positive digestive

system cancers (135). Data from

37 treated patients showed an overall response rate (ORR) of 48.6%

and a disease control rate (DCR) of 73.0%. In patients with GC, the

ORR was 57.1% while DCR was 75.0% and the 6-month OS rate was

81.2%. These results suggest CT041 is effective and well tolerated

in GC.

Beyond CLDN18.2, CAR-T research in GC has focused on

other targets such as mucin 1 (cell surface associated), HER2 and

CEA. For example, clinical trials are underway for TCR-based

therapies targeting MAGE family member A4 (MAGE-A4). While MAGE-A4

expression in GC is relatively low (9%), MAGE-A4-targeted TCR

therapy is also under investigation in other solid tumors (136). Meyer et al (137) assessed the safety and preliminary

efficacy of AFP-targeted TCR-T cells (ADP-A2AFP) in a phase I trial

(trial ID no. NCT03132792) for patients with gastric hepatoid

carcinoma. Results showed this therapy induced complete and partial

remissions in some patients, with manageable toxicity.

NK cells, either expanded in vitro or derived

from induced pluripotent stem cells, can bypass immune evasion by

recognizing tumor cells with reduced MHC-I expression. A study has

detailed that activated NK cells exhibit enhanced cytotoxicity

against GC cells (138).

Currently, numerous GC-related cell therapy studies

are in phase I/II trials, which primarily evaluate safety and early

efficacy, and have not yet advanced to phase III registration

studies. Phase I trials typically investigate safe dosages, toxic

reactions and cellular kinetics, CAR-T cells can proliferate within

the body and effectively target tumor cells in the short term;

however, their long-term persistence is limited. These cells may be

eliminated by the immune system or lose their functionality due to

immune evasion mechanisms, such as the inhibitory effects of the

TME. Phase II trials are initiated to explore combination regimens,

and early data suggests these combinations may modestly improve

efficacy but at the cost of increased adverse events. The lack of

phase III studies is mainly attributed to patient heterogeneity,

complex manufacturing processes and cost considerations.

Cell therapy for GC also faces ongoing challenges,

including tumor heterogeneity and difficulties in target selection.

GC lacks highly specific antigen targets and single-target

heterogeneity can lead to antigen escape (139). The short lifespan of CAR-T cells

also hinders the establishing of long-term immune memory.

Furthermore, CAR-T cell overload can cause high fever and organ

dysfunction, highlighting the importance of managing adverse events

(140,141). Most notably, clinical validation

systems remain incomplete and large-scale multi-center randomized

controlled phase III trials to confirm efficacy are still

lacking.

While cell therapy holds promise for GC

immunotherapy, its application is limited by the complex regulation

of the TME, tumor heterogeneity and immunosuppressive states. The

majority of current studies are still in phase I/II stages, as

while encouraging efficacy signals exist, they are insufficient to

support widespread clinical implementation. To enhance cell therapy

effectiveness, future efforts should focus on ensuring each target

elicits appropriate immune responses and establishing triggered

self-destruction mechanisms to mitigate adverse effects.

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)

Antibody-drug conjugates consist of a monoclonal

antibody targeting tumor-associated antigens, a cleavable linker

and a highly potent cytotoxic payload. They integrate the

specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the same efficacy as

small-molecule drugs at inducing cell death. Trastuzumab

deruxtecan, a novel anti-HER2 ADC, has exhibited manageable safety

profiles and robust tumor activity in patients with

HER2+ advanced GC (142). This agent comprises a humanized

anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody, an enzyme-cleavable peptide linker

and the topoisomerase I inhibitor deruxtecan, with a high

drug-to-antibody ratio of 8:1 and offers the additional advantage

of a bystander effect (143).

Notably, disitamab vedotin (RC48) demonstrated

promising efficacy in phase I/II clinical trials involving patients

with HER2+ GEJC who had received at least two prior

lines of therapy. These patients achieved a median PFS of 3.8–4.1

months and a median OS of 6.8–7.9 months. The majority of adverse

events were grade 1 or 2, confirming manageable safety (144). Ongoing studies are evaluating the

combination of RC48 with PD-1 inhibitors, with preliminary findings

indicating enhanced antitumor activity and acceptable toxicity,

suggesting that pairing ADCs with ICIs may further improve

therapeutic efficacy (145).

However, numerous barriers limit ADC effectiveness.

Dense stroma and high endocytosis rates restrict ADC penetration

and distribution within the tumor parenchyma. In addition, elevated

lysosomal enzyme activity or the use of non-cleavable linkers can

impair intracellular drug release efficiency (146). Tumor cells can also develop

resistance to ADCs by downregulating target antigens, upregulating

ATP-binding cassette transporters to promote drug efflux or

altering endocytic and lysosomal trafficking (147). In the future, combining liquid

biopsy-based biomarkers (such as circulating tumor cells and

cell-free tumor DNA) with multi-omics approaches may facilitate

real-time monitoring of treatment responses and resistance

patterns, guiding the personalized use of ADCs (148).

Overall, ADCs represent an innovative therapeutic

platform that merges targeted delivery with potent cytotoxicity,

demonstrating efficacy in overcoming immune tolerance in GC. Future

advancements in linker design, multi-targeting strategies and

combinations with immunotherapies are expected to yield more

precise, effective and safer therapies for patients.

Biologics

Biologics hold notable promise for reversing immune

tolerance in the TME, owing to their specificity and diverse

immunomodulatory effects. Bispecific antibodies (BsAbs), a distinct

class of biologics, are engineered to bind simultaneously to two

distinct antigens or two epitopes on the same antigen. The core

mechanism of BsAbs involves enhancing antitumor immune responses by

co-targeting tumor cells and immune cells, such as T-cells. For

example, CD3 BsAbs direct T-cells to the tumor microenvironment,

activate them and induce tumor cell cytotoxicity (149,150). Furthermore, BsAbs can reshape the

TME and boost antitumor responses by blocking immunosuppressive

signals (such as PD-L1 and TGF-β) or activating co-stimulatory

signals (including CD28 and 4-1BB) (151,152).

Additional TME-modulating agents, such as

anti-TGF-β antibodies and VEGFR inhibitors, can modulate

immunosuppressive factors in the TME, thereby enhancing immune

cell-mediated tumor recognition and inducing cell death. Anti-TGF-β

therapy blocks the TGF-β signaling pathway, inhibits its protumor

effects and strengthens the antitumor response of the immune system

(153). A separate study found

that anti-TGF-β therapy can reprogram TANs from a protumor

phenotype to an antitumor phenotype, suppressing tumor growth and

metastasis (154). Anti-VEGFR

inhibitors enhance immune cell antitumor responses by inhibiting

tumor angiogenesis and increasing immune cell infiltration into the

tumor (155).

Jung et al (156) developed an oncolytic adenovirus

designed to express IL-12p35, IL-12p40, granulocyte macrophage-CSF

and relaxin. This construct efficiently degrades collagen networks,

modifies matrix density and enhances CD8+ T-cell

infiltration across a number of tumor types (including GC and

pancreatic cancer), markedly improving the efficacy of PD-1

blockade therapy. Additionally, eganelisib (IPI-549), an oral

selective inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ, restores the

function of TAMs and MDSCs to enhance immune effector activity. By

inhibiting PI3K signaling in both the TME and immune cells, IPI-549

enhances the efficacy of PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors

(157).

Despite their promise, biologics face challenges in

clinical application. Accurate targeting is required to minimize

off-target toxicity, as immune responses against nanoparticle-based

carriers remain a concern and tumor cells can develop adaptive

resistance mechanisms (158,159).

In summary, biologics represent promising

therapeutic strategies for overcoming tumor immune tolerance by

precisely modulating the TME. Despite ongoing challenges, their

potential to reverse immunosuppression and enhance antitumor immune

responses remains notable. With continued technological innovation

and interdisciplinary collaboration, biologics may serve an

increasingly important role in cancer immunotherapy.

Overall, treatment strategies targeting immune

tolerance within the GC TME are moving away from single target

approaches toward multi-dimensional, coordinated regulation, with

the TME immunosuppressive network disruption at their core.

Although technical barriers persist, advances in understanding TME

heterogeneity and optimizing combination therapies are expected to

improve immunotherapy response rates and deliver meaningful

clinical benefits to patients with GC. Table II summarizes current

immunotherapeutic approaches for overcoming immune tolerance in GC,

highlighting the distinct mechanisms, clinical progress and

limitations of ICIs, cell-based therapies, antibody-drug conjugates

and biologics.

| Table II.Emerging immunotherapeutic strategies

for overcoming immune tolerance in GC. |

Table II.

Emerging immunotherapeutic strategies

for overcoming immune tolerance in GC.

| Therapy | Mechanism | Key results | Challenges and

future directions |

|---|

| Immune checkpoint

inhibitors | PD-1 inhibitors

(such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab) | Prolonged survival

in GC with PD-L1 CPS ≥5 | Heterogeneous

responses and PD-L1 biomarker controversy |

| Cell-based

therapy | CAR-T targeting

tumor antigens (such as CT041 and CLDN18.2) | 57.1% ORR, 75.0%

DCR in GC and 81.2% 6-month survival | Limited

persistence, antigen escape and severe toxicity |

| Antibody-drug

conjugates | Monoclonal

antibodies and cytotoxic drugs (such as trastuzumab and

deruxtecan) | Effective in

HER2+ advanced GC and GEJC | Limited tumor

penetration and resistance mechanisms |

| Biological

agents | Bispecific

antibodies (such as CD3 bispecific antibodies) | Enhances T-cell

activation and tumor cytotoxicity | Off-target toxicity

and adaptive resistance |

Differences between preclinical and clinical

evidence and their importance

In recent years, numerous studies have shown that

TME serves a key role in establishing and sustaining immune

tolerance in GC. To improve scientific rigor, the present review

distinguishes between preclinical and clinical evidence to avoid

conflating experimental results with clinical outcomes.

A preclinical study using animal models and in

vitro systems has shown that the TME regulates GC immune

tolerance through the activation of key signaling pathways

(160). For example, TAMs and

MDSCs jointly deplete nutrients important for T-cell activation and

alter DC maturation through shared metabolic inhibitory pathways

and cytokine networks. These mechanisms disrupt antigen

presentation, thereby diminishing T cell-mediated antitumor

responses. Additionally, the CAF-mediated C3-C3AR1 axis promotes

the recruitment and functional polarization of TAMs, establishing

an immunosuppressive microenvironment. These findings advance the

understanding of cellular mechanisms underlying TME-mediated immune

regulation.

However, preclinical outcomes do not directly

translate to clinical efficacy. Animal and cell-based models have

limitations in recapitulating the complexity of the human GC immune

microenvironment, including discrepancies in immune cell ratios,

simplified cytokine networks and the absence of a fully functional

human immune system. Thus, while preclinical studies provide

valuable clues for mechanistic investigation, their conclusions

require validation with large-scale clinical trials and real-world

data to demonstrate clinical relevance.

In clinical trials, analyses of patient tissue

samples, immunohistochemistry and transcriptomic data have further

confirmed the role of the TME in GC immune escape. For example, in

phase III trials such as CheckMate-649 and KEYNOTE-062, patients

with high PD-L1 expression and elevated immunosuppressive cell

infiltration often exhibit poor responses to immunotherapy. This

clinical evidence indicates that TME features are associated with

the efficacy of ICIs, reflecting the pathological state of tumors

and their response to treatment. However, fully validating the

precise mechanisms driving GC immune tolerance remains challenging

due to limitations in sample size, inadequate patient

stratification and short follow-up periods.

Overall, preclinical studies provide molecular and

cellular insights into TME-mediated immune tolerance in GC, while

clinical studies demonstrate the relevance and therapeutic

importance of these mechanisms in patients. By distinguishing

between these two types of evidence, the present review not only

enhances scientific integrity but also reduces the risk of

artefactual misinterpretation of experimental outcomes as clinical

conclusions. To advance TME-targeted immunotherapy for GC, future

research should aim to prioritize the translational validation of

preclinical findings.

Challenges and limitations of TME-targeted

therapeutic strategies

Although TME-targeted approaches have emerged as

promising strategies for GC immunotherapy recently, their clinical

efficacy has been limited in numerous aspects.

GC is a highly heterogeneous malignancy, with

notable variations in genomic profiles, immune cell composition and

microenvironmental features between patients and even across

different regions of the same tumor. This extensive heterogeneity

limits the effectiveness of single-agent TME-targeted therapies,

highlighting the need for personalized treatment strategies.

The TME is not just a ‘supportive environment’ for

tumor cells but a dynamic system that rapidly adapts to therapeutic

pressures. During immunotherapy, tumor cells often develop adaptive

resistance through multiple mechanisms. For example, while ICIs may

initially activate T-cells, immunosuppressive cells within the TME,

such as Tregs and TAMs, may reverse immune tolerance by modulating

immune responses. This resistance reduces the long-term efficacy of

single-target therapies.

PD-L1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

have been proposed as predictive indicators of immunotherapy

efficacy, but their utility in GC remains inconsistent. The

predictive value of these biomarkers across different GC subtypes

has not been fully validated and they lack sufficient specificity

and sensitivity. Thus, identifying novel and more reliable

biomarkers remains a major barrier to advancing TME-targeted

immunotherapy.

To address these limitations and improve the

efficacy of GC immunotherapy, future research directions may focus

on the following methods. Firstly, combining ICIs, as immune cell

reprogramming and tumor angiogenesis inhibitors may yield more

effective strategies for TME modification and overcoming immune

tolerance. For example, pairing anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies with

anti-CTLA-4 antibodies can enhance T-cell activation and rewire the

immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Beyond classical ICIs, targeted therapies directed

against other immunomodulatory factors in the TME are promising.

Targeting immunosuppressive cells (such as Tregs and TAMs) that

actively suppress antitumor immunity, can enhance immunotherapy

efficacy. Identifying such new targets may contribute to

advancements in GC immunotherapy.

The current inadequacy of biomarkers for predicting

responses to TME-targeted therapies underscores the need for more

accurate tools. Studying dynamic changes in TME immune cells,

phenotypic features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and tumor

immune metabolic states may enable the development of more precise

biomarkers for individualized treatment. The screening and

validation of these biomarkers could provide more reliable guidance

for the clinical application of immunotherapy.

Summary and outlook

GC cell growth is associated with TME-induced

immune tolerance, as tumor cells cannot be identified by the immune

system through a complex regulatory network. The present review

exhibits a systematic investigation of cellular and non-cellular

composition of the GC TME, as well as their mechanisms for

orchestrating immune tolerance.

From a compositional perspective, dynamic

interaction of cellular and non-cellular components of TME

establishes an immunosuppressive environment. At the molecular

level, the immune responses are suppressed by impaired antigen

presentation, immune checkpoint activation, imbalance of cytokine

networks, metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic regulation and

exosome-mediated information transfer. All components act

synergistically through numerous pathways. Furthermore, core immune

cells, including MDSCs, TAMs, Tregs and DCs interact dynamically to

form a stable immunosuppressive network, exacerbating the immune

tolerance state in GC.

Consequently, novel therapies targeting TME-induced

immune tolerance exhibit promise. ICIs enhance immune response and

tumor immunity. Similarly, cell therapies modify immune effector

cells to enhance anti-tumor immunity. ADCs enable precise targeting

of tumors and infusion of immune effector cells. Finally, biologics

induce immunization and regulate TME composition and function.

The immune cells and cytokines in the TME work in

conjunction to adaptively suppress the host antitumor immune

response within the tumor and eventually help in evading host

antitumor recognition. However, current research still has exhibits

gaps and limitations. Effective biomarkers to predict immunotherapy

responses remain lacking. While PD-L1 expression and

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes have been explored as potential

biomarkers for GC, their predictive value is often

subtype-dependent and has not been accurately verified. This

underscores the need for new biomarkers to optimize the clinical

application of immunotherapy. Also, the heterogeneity of immune

responses in GC is unknown. The immune tolerance mechanisms may

vary across subtypes. Some subtypes may evade immune surveillance

by suppressing T-cell activity, while others may rely on immune

cell reprogramming or exploitation of immune checkpoint pathways.

Current understanding of this heterogeneity remains limited, so

multidimensional analyses are needed to uncover disparities in

immune responses across subtypes. In addition, existing preclinical

models have notable limitations. The majority of studies on

TME-mediated immune escape use mouse xenograft models, which

provide useful insights, but capacity to shed light on GC is

limited. Therefore, more animal models are urgently required to

accurately evaluate the efficacy of a number of immunotherapeutic

strategies for GC.

Ethical and societal considerations regarding

TME-targeted therapies require complex genetic testing and

precision medication assistance, which places additional strain on

healthcare resource allocation and limits patient access.

Exorbitant costs of testing and medications prevent some patients

from accessing these treatments. Furthermore, TME-targeted

immunotherapies are generally costly and long-term data

demonstrating improvements in survival and quality of life remain

scarce.

Additionally, TME modulation strategies typically

bypass immune tolerance through widespread immune activation, which

can trigger non-specific immune-related adverse events such as

immune enteritis, pneumonia, hepatitis and endocrine dysfunction.

Although the side effects of monoclonal antibodies can be partially

managed with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants in clinical

practice, long-term risks (including disease recurrence and chronic

tissue damage) remain a concern for multi-target combination

therapies. From a health economics perspective, the

cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit ratio of immunotherapy in

comparison with traditional chemotherapy or targeted chemotherapy

will largely determine their inclusion in clinical guidelines and

health insurance coverage.

In conclusion, while notable progress has been made

in understanding the role of the TME in GC immune tolerance,

numerous challenges remain before clinical advancements can be

achieved. The complexity and dynamism of the TME hinder the

translation of experimental findings into clinical practice. Future

studies should aim to use system immunomics and multi-omics

approaches and high-throughput spatial transcriptomics to

facilitate the translation from mechanism to clinical practice.

Only through rigorous validation and careful assessment of

immunomodulatory strategies, can the goals of precise GC treatment

be achieved.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the

research, authorship and/or publication of this article. The

present review was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of

Heilongjiang Province (grant no. LH2023H059).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZG and LH conceived the present review, conducted

the literature review and wrote the manuscript. BC, YM and QN

assisted with the literature review and manuscript revision. ZW and

JY contributed to manuscript writing and interpretation. ZL

provided critical feedback and helped with manuscript revision.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Tan N, Wu H, Cao M, Yang F, Yan X, He S,

Cao M, Zhang S, Teng Y, Li Q, et al: Global, regional, and national

burden of early-onset gastric cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 21:667–678.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yu WY, Li X, Zhu J, Ding YM, Tao HQ and Du

LB: Epidemiological characteristics of gastric cancer in China and

worldwide. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 47:468–476. 2025.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lin JL, Lin JX, Lin GT, Huang CM, Zheng

CH, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lu J, Chen QY and Li P: Global incidence and

mortality trends of gastric cancer and predicted mortality of

gastric cancer by 2035. BMC Public Health. 24:17632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ma ES, Wang ZX, Zhu MQ and Zhao J: Immune

evasion mechanisms and therapeutic strategies in gastric cancer.

World J Gastrointest Oncol. 14:216–229. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liu Y, Li C, Lu Y, Liu C and Yang W: Tumor

microenvironment-mediated immune tolerance in development and

treatment of gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 13:10168172022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yasuda T and Wang YA: Gastric cancer

immunosuppressive microenvironment heterogeneity: Implications for

therapy development. Trends Cancer. 10:627–642. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Romagnani S: Immunological tolerance and

autoimmunity. Intern Emerg Med. 1:187–196. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang H, Dai Z, Wu W, Wang Z, Zhang N,

Zhang L, Zeng WJ, Liu Z and Cheng Q: Regulatory mechanisms of

immune checkpoints PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 40:1842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang J, Liu T, Huang T, Shang M and Wang

X: The mechanisms on evasion of anti-tumor immune responses in

gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 12:9438062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shi AN, Zhou YB and Wang GH:

Immunotherapy: Progress and challenges of a revolutionary treatment

for gastric cancer. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 63:563–567. 2025.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhao Y, Bai Y, Shen M and Li Y:

Therapeutic strategies for gastric cancer targeting immune cells:

Future directions. Front Immunol. 13:9927622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

He B, Wood KH, Li ZJ, Ermer JA, Li J,

Bastow ER, Sakaram S, Darcy PK, Spalding LJ, Redfern CT, et al:

Selective tubulin-binding drugs induce pericyte phenotype switching

and anti-cancer immunity. EMBO Mol Med. 17:1071–1100. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang K, Xie CJ, Ding Z, Shan T, Zhong Z,

Yuan FL, Wu JJ, Yuan ZD, Qian C, Yu L, et al: PDE5A+

cancer-associated fibroblasts enhance immune suppression in gastric

cancer. Gut. October 20–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Shaibu Z, Danbala IA, Chen Z and Zhu W:

Role of mesenchymal stem cells in modulating cytokine networks and

immune checkpoints in gastric cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta

Rev Cancer. 1880:1894332025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

He X, Guan XY and Li Y: Clinical

significance of the tumor microenvironment on immune tolerance in

gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 16:15326052025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lv Y, Zhao Y, Wang X, Chen N, Mao F, Teng

Y, Wang T, Peng L, Zhang J, Cheng P, et al: Increased intratumoral

mast cells foster immune suppression and gastric cancer progression

through TNF-α-PD-L1 pathway. J Immunother Cancer. 7:542019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Weng N, Zhou C, Zhou Y, Zhong Y, Jia Z,

Rao X, Qiu H, Zeng G, Jin X, Zhang J, et al: IKZF4/NONO-RAB11FIP3

axis promotes immune evasion in gastric cancer via facilitating

PD-L1 endosome recycling. Cancer Lett. 584:2166182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shukla A, Cloutier M, Appiya Santharam M,

Ramanathan S and Ilangumaran S: The MHC Class-I Transactivator

NLRC5: Implications to cancer immunology and potential applications

to cancer immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 22:19642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang J, Yu D, Ji C, Wang M, Fu M, Qian Y

and Zhang X, Ji R, Li C, Gu J and Zhang X: Exosomal

miR-4745-5p/3911 from N2-polarized tumor-associated neutrophils

promotes gastric cancer metastasis by regulating SLIT2. Mol Cancer.

23:1982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Nair R, Somasundaram V, Kuriakose A,

Krishn SR, Raben D, Salazar R and Nair P: Deciphering T-cell

exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment: Paving the way for

innovative solid tumor therapies. Front Immunol. 16:15482342025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chow A, Perica K, Klebanoff CA and Wolchok

JD: Clinical implications of T cell exhaustion for cancer

immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 19:775–790. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yu K, Cao Y, Zhang Z, Wang L, Gu Y, Xu T,

Zhang X, Guo X, Shen Z and Qin J: Blockade of CLEVER-1 restrains

immune evasion and enhances anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in gastric

cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 13:e0110802025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Shi T, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Song X, Wang H,

Zhou X, Liang K, Luo Y, Che K, Wang X, et al: DKK1 promotes tumor

immune evasion and impedes Anti-PD-1 treatment by inducing

immunosuppressive macrophages in gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol

Res. 10:1506–1524. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang T, Li Y, Zhai E, Zhao R, Qian Y,

Huang Z, Liu Y, Zhao Z, Xu X, Liu J, et al: Intratumoral

fusobacterium nucleatum recruits Tumor-associated neutrophils to

promote gastric cancer progression and immune evasion. Cancer Res.

85:1819–1841. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li Z, Zhang W, Bai J, Li J and Li H:

Emerging role of helicobacter pylori in the immune evasion

mechanism of gastric cancer: An insight into tumor

microenvironment-Pathogen interaction. Front Oncol. 12:8624622022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jiang L, Zhao X, Li Y, Hu Y, Sun Y, Liu S,

Zhang Z, Li Y, Feng X, Yuan J, et al: The tumor immune

microenvironment remodeling and response to HER2-targeted therapy

in HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer. IUBMB Life. 76:420–436.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sun H, Wang X, Wang X, Xu M and Sheng W:

The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumorigenesis of

gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 13:8742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Allam A, Yakou M, Pang L, Ernst M and

Huynh J: Exploiting the STAT3 nexus in cancer-associated

fibroblasts to improve cancer therapy. Front Immunol.

12:7679392021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wu X, Tao P, Zhou Q, Li J, Yu Z, Wang X,

Li J, Li C, Yan M, Zhu Z, et al: IL-6 secreted by cancer-associated

fibroblasts promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

metastasis of gastric cancer via JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway.

Oncotarget. 8:20741–20750. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hilmi M, Nicolle R, Bousquet C and

Neuzillet C: Cancer-associated fibroblasts: Accomplices in the

tumor immune evasion. Cancers (Basel). 12:29692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Avagliano A, Granato G, Ruocco MR, Romano

V, Belviso I, Carfora A, Montagnani S and Arcucci A: Metabolic

reprogramming of cancer associated fibroblasts: The slavery of

stromal fibroblasts. Biomed Res Int. 2018:60754032018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kitamura F, Semba T, Yasuda-Yoshihara N,

Yamada K, Nishimura A, Yamasaki J, Nagano O, Yasuda T, Yonemura A,

Tong Y, et al: Cancer-associated fibroblasts reuse cancer-derived

lactate to maintain a fibrotic and immunosuppressive

microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. JCI Insight. 8:e1630222023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Iha K, Sato A, Tsai HY, Sonoda H, Watabe

S, Yoshimura T, Lin MW and Ito E: Gastric cancer cell-derived

exosomal GRP78 enhances angiogenesis upon stimulation of vascular

endothelial cells. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 44:6145–6157. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang R, Liu G, Wang K, Pan Z, Pei Z and Hu

X: Hypoxia signature derived from tumor-associated endothelial

cells predict prognosis in gastric cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol.

13:15156812025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Fang J, Lu Y, Zheng J, Jiang X, Shen H,

Shang X, Lu Y and Fu P: Exploring the crosstalk between endothelial

cells, immune cells, and immune checkpoints in the tumor

microenvironment: New insights and therapeutic implications. Cell

Death Dis. 14:5862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liu Q, Yu M, Lin Z, Wu L, Xia P, Zhu M,

Huang B, Wu W, Zhang R, Li K, et al: COL1A1-positive endothelial

cells promote gastric cancer progression via the ANGPTL4-SDC4 axis

driven by endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Lett.

623:2177312025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhu Y, Xiang M, Brulois KF, Lazarus NH,