Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most prevalent

malignancy diagnosed in women worldwide, following breast,

colorectal and lung cancer (1).

Numerous risk factors have been associated with cervical cancer,

including human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, early onset of

sexual activity, multiple sexual partners, the use of oral

contraceptives and smoking. In this context, HPV vaccination has

demonstrated safety and effectiveness as a primary prevention

strategy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and cervical

cancer (2). CIN is a premalignant

stage in the development of cervical cancer and provides an

opportunity for early detection and intervention. Although

persistent infection with HPV is considered the major cause of the

disease, only a small proportion of HPV-infected women develop

cervical malignancy, which limits the utility of HPV testing due to

its low positive predictive value for high-grade lesions (3,4). Other

main screening techniques for cervical cancer include the Pap

smear, visual inspection with acetic acid and Lugol's iodine and

liquid-based cytology. Several countries, including Türkiye, United

Kingdom, Australia, Canada and The Netherlands, have implemented

cytology-based testing and HPV testing as part of their cancer

screening programs (5). There is

increasing interest in the identification of novel molecular

markers to improve the identification of individuals at high risk

of cervical cancer, with the aim of expanding the reach of

screening programs in the community, improving accessibility and

increasing their diagnostic accuracy.

In almost every type of human cell, there are

hundreds to thousands of mitochondria, each containing its own

genome, a feature that distinguishes mitochondria from other

organelles. Human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a circular,

double-stranded DNA of ~16,569 nucleotides that is involved in a

variety of cellular functions (6).

It contains a total of 37 genes encoding 13 proteins essential for

the oxidative phosphorylation system, as well as 22 transfer RNAs

and 2 ribosomal RNAs (7). Several

characteristics distinguish mtDNA from nuclear DNA (nDNA). The most

well-known of these is the maternal inheritance of mtDNA, which

differs from the Mendelian pattern of inheritance. Another feature

is that the mitochondrial genome is polyploid, meaning that each

cell has multiple copies of mtDNA depending on the cell type

(8). mtDNA is present in multiple

copies per cell, with the copy number typically ranging from 1,000

to 10,000 and varying according to the type of cell (9). Notably, mtDNA is particularly

vulnerable to damage and copy number alterations, due to exposure

to reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other metabolites generated

within mitochondria, the lack of protective histones, and

inadequate repair and protection mechanisms (10). Alterations in mtDNA copy number

(mtCN) can potentially result in impaired mitochondrial function

and increased ROS production. Variations in mtCN have been observed

in numerous pathological conditions, including neuropsychiatric

disorders, autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammation and various

types of cancer (11–13). In this context, alongside

well-characterized alterations in nDNA, mtDNA has also been

extensively studied in a range of cancer types (9).

Changes in mtCN, reflecting the balance between

mitochondrial biogenesis and degradation, have emerged as potential

indicators of cellular dysfunction and tumorigenesis. It has been

suggested that mtCN increases during the early stages of cancer to

compensate for metabolic defects in damaged mitochondria, However,

in advanced stages, cumulative damage may result in mtDNA

degradation and a subsequent reduction in mtCN (14,15).

In light of this, previous studies have elucidated the involvement

of mtCN alterations in the pathogenesis of various cancer types in

different patient cohorts. mtCN changes reported in the literature

vary according to cancer stage, the characteristics of the study

cohort and additional patient-related factors (16). This variability indicates that, when

mtDNA is considered as a biomarker in cancer, expectations of

increased or decreased copy numbers in tumor samples cannot be

generalized and may not be independent of diagnosis, stage and

patient characteristics. Therefore, it is essential to

quantitatively determine the alterations of mtDNA within the

specific population for which a predictive model is being

developed.

Considering that high-risk HPV oncoproteins E6 and

E7 may induce DNA damage by affecting ROS production by different

mechanisms (17), it can be

hypothesized that alterations in mtCN associated with mtDNA damage

in cervical cancer cells may contribute to cervical carcinogenesis.

Supporting this hypothesis, Sun et al (18) demonstrated that the mtCN in cells

from cervical smear samples from patients with cervical cancer was

significantly higher than that in corresponding samples from

cancer-free controls. Furthermore, Warowicka et al (19) reported an association between

increased mtCN, as well as mtDNA mutations, with the pathogenesis

of cervical cancer. A recent study has demonstrated a significant

association between altered mtCN and cervical cancer, even in

HPV-negative cases. Al-Awadhi et al (20) demonstrated elevated mtCN levels in

both high-risk HPV-positive and HPV-negative cervical samples,

suggesting that this increase may represent an adaptive response to

mitochondrial oxidative stress and energy deficiency.

Despite accumulating evidence that high-risk HPV

oncoproteins (E6/E7) can increase oxidative stress and perturb

mitochondrial homeostasis, the direction and magnitude of mtCN

changes appear to vary across settings. In cervical pathology,

previous studies have primarily compared cancer or high-grade

squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs) with samples from control

subjects without evaluating mtCN alterations across the full

spectrum of CIN. In addition, they have rarely included HPV status

in the same analysis. Consequently, it remains unclear whether mtCN

exhibits a stepwise pattern with increasing histological severity

and whether such a pattern is influenced by HPV positivity. To

address this gap, the present study quantified mtCN across normal,

CIN1 [low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL)], CIN2/3

(HSIL) and invasive cervical cancer tissues. In addition, the

combined contribution of mtCN, HPV status and smoking status was

evaluated in relation to the classification of high-risk

disease.

Materials and methods

Study group

A total of 100 participants who presented at the

Gynecology and Obstetrics Clinic of Ankara Etlik City Hospital

(Ankara, Türkiye) between July 2023 and September 2023 and provided

cervical samples were included in the present study. All

participants were female, and their median age was 53 years, with

an age range of 45–65 years. Prior to intervention, written

informed consent was obtained from each patient. The patients were

selected based on histopathological diagnosis, and included 32

healthy individuals and 52 patients with cervical pathology. The

latter comprised 21 cases of CIN1 (LSIL), 23 cases of CIN2/3 (HSIL)

and 8 cases of cervical cancer. The remaining 16 samples were

excluded due to insufficient DNA yield or suboptimal quality.

Personal and clinical data of the participants,

including age, medical history, histopathological features and HPV

genotype were collected from the digital medical archive. The

samples were collected from patients aged 45–65 years, with efforts

made to minimize age-related variations in mtDNA by ensuring a

comparable age distribution across groups. To standardize mtCN,

individuals with a history of chronic exposure to environmental or

occupational agents, narcotic substances or drugs, as well as those

with chronic inflammation of the internal genital organs or

adjacent tissues, were excluded from the study. Smoking status was

recorded and evaluated as a variable in the analysis. The control

group included both HPV-negative and HPV-positive cases; HPV16 and

HPV18 were classified as high-risk. The present study was approved

by the Ethics Committee of Ankara Etlik City Hospital

(AEŞH-EK1-2023-015).

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed,

paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cervical tissue sections using the

AmoyDx® FFPE DNA Kit (Amoy Diagnostics Co., Ltd.),

following the manufacturer's protocol. The FFPE tissue blocks had

been archived for ≤12 months. Serial 5-µm FFPE sections were cut

for nucleic acid extraction. Briefly, deparaffinization was

performed using the standard xylene/ethanol method and DNA was

isolated via the silica column-based procedure of the kit. The

purified DNA was eluted and stored at −20°C until further analysis.

DNA concentration and purity were evaluated using a NanoDrop

ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and samples with an optical density (OD)260/OD280

ratio between 1.8 and 2.0 were considered suitable for downstream

sequencing.

HPV status assessment

The HPV status of the cervical samples was

determined. This was performed by analysis of the extracted DNA

using the cobas® HPV Test on the cobas® 4800

testing system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche

Diagnostics for both). This qPCR-based assay detects 14 high-risk

HPV genotypes, providing individual results for HPV16 and HPV18 and

pooled detection for 12 additional types (HPV31, 33, 35, 39, 45,

51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68). The specific primer sequences used

in this commercial assay are proprietary to the manufacturer and

not disclosed. The analytical sensitivity and specificity of the

cobas® HPV Test for the detection of CIN2+ lesions have

been reported in clinical validation studies to be 90–99 and ~87%,

respectively (21). All analyses

were performed in the institutional laboratory following standard

quality control procedures.

Measurement of mtCN

The mtCN normalized to nDNA in cervical cells was

determined using quantitative PCR (qPCR). The difference in

quantification cycle (ΔCq) values of the NADH dehydrogenase subunit

1 (ND1) and hemoglobin subunit β (HBB) genes were used to evaluate

the mtCN and nDNA copy number, respectively. Amplification was

performed using QuantiNova SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Inc.)

and a commercial primer assay (RT2 qPCR Primer Assay;

Qiagen, Inc.) on the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The primer sequences are presented in

Table SI. The reference gene,

hemoglobin subunit beta (HBB), was selected as a single-copy

nuclear locus with stable representation in cervical epithelial DNA

and no known regulation by mitochondrial pathways, consistent with

previous validations (11–13).

qPCR was performed for 40 cycles using a two-step

protocol, comprising denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, followed by

combined annealing and extension at 60°C for 60 sec, in accordance

with the manufacturer's recommendations for SYBR Green chemistry.

The assay results were accepted when the following criteria were

met: i) Cq values <35 for both the mtDNA target ND1 and the

single-copy nuclear reference (HBB); ii) no amplification in

no-template controls (Cq undetermined or >40); iii) melting

curve analysis demonstrated a single, specific peak with a

consistent melting temperature across replicates (±0.5°C); and iv)

technical replicates differed by ≤0.3 Cq.

The relative mtCN differences between the study

groups and controls were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq

method and expressed as fold change (22).

Power analysis

An a priori sample size calculation was

performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7; Heinrich Heine

University Düsseldorf; http://www.gpower.hhu.de) based on a two-tailed

independent t-test with an α value of 0.05 and statistical power of

0.80. The analysis was designed to compare a high-risk group,

comprising patients with HSIL or invasive cancer, with a low-risk

group, comprising patients with LSIL or normal cervical cytology

based on mtCN fold-change (2−ΔΔCq) as the continuous

outcome measure. A conservative effect size corresponding to a

large Cohen's d of 0.80 was assumed to prevent the overestimation

of results, based on previous studies reporting significant

mitochondrial alterations, including elevated mtCN, in cervical

cell exfoliates, and major mitochondrial genomic alterations in

dysplastic and cancerous tissues (20,22,23).

Under the assumption of an equal group allocation, the required

sample size was 25 per group. A 20% attrition/mismeasurement buffer

was established; therefore, the prespecified target sample size was

increased to 30 per group (total, n=60). These assumptions were

informed by published evidence on mitochondrial abnormalities in

HPV-related cervical pathology (19,20).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version

4.1.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing; http://www.r-project.org/) via the RStudio interface

(Posit Software, PBC; http://posit.co/). Descriptive statistics are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation or median and

interquartile range, as appropriate. One-way analysis of variance

was applied to normally distributed numerical values, Associations

between categorical variables were evaluated using Fisher's exact

test.

In the model-building process, the normal and LSIL

categories were merged to form a low-risk group, while the HSIL and

invasive cancer categories were combined to form a high-risk group,

yielding a binary outcome variable. Logistic regression with a

logit function was used to predict the binomial target variable. As

only one numerical predictor was available, univariate methods were

used to identify potential outliers and extreme values prior to

model fitting. Overall, seven models were constructed and used for

prediction. The performance of all models was assessed using

sensitivity, specificity, accuracy and receiver operating curve

(ROC) analysis, and the area under the curve was determined.

Optimal thresholds were determined using the Youden index.

Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05, with an a set at

0.05 and β at 0.80 (24).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive characteristics of the full cohort of

100 patients according to disease status are presented in Table I, including age, HPV and smoking

status. The mean age of all patients was 53.45±5.74 (range, 45–65)

years. Patients positive for HPV16 or HPV18 were classified as the

high-risk oncogenic HPV group, in accordance with

established cervical cancer risk stratification. Patients positive

for other HPV genotypes detected by the assay (including non-16/18

high-risk types) as well as HPV-negative individuals were analyzed

together as a non-HPV16/18 group for comparative purposes.

No statistically significant differences were observed between the

groups with respect to age, HPV category or smoking status.

| Table I.Comparison of demographic and

clinical variables of the full cohort according to cervical disease

group. |

Table I.

Comparison of demographic and

clinical variables of the full cohort according to cervical disease

group.

| Variables | Total (n=100) | Normal (n=38) | LSIL (n=25) | HSIL (n=26) | Cancer (n=11) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 53.45±5.74 | 53.9±5.84 | 54.5±5.30 | 51.7±5.58 | 53.5±6.55 | 0.316a |

| (min-max),

years | (45–65) | (45–65) | (45–63) | (45–62) | (45–64) |

|

| HPV, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| 0.057b |

|

High-risk | 55 (55.00) | 15 (39.47) | 15 (60.00) | 16 (61.54) | 9 (81.82) |

|

|

Low-risk | 45 (45.00) | 23 (60.53) | 10 (40.00) | 10 (38.46) | 2 (18.18) |

|

| Smoking status, n

(%) |

|

|

|

|

| 0.51b |

|

Smoker | 18 (18.00) | 5 (13.16) | 7 (28.00) | 4 (15.38) | 2 (18.18) |

|

|

Non-smoker | 82 (82.00) | 33 (86.84) | 18 (72.00) | 22 (84.62) | 9 (81.82) |

|

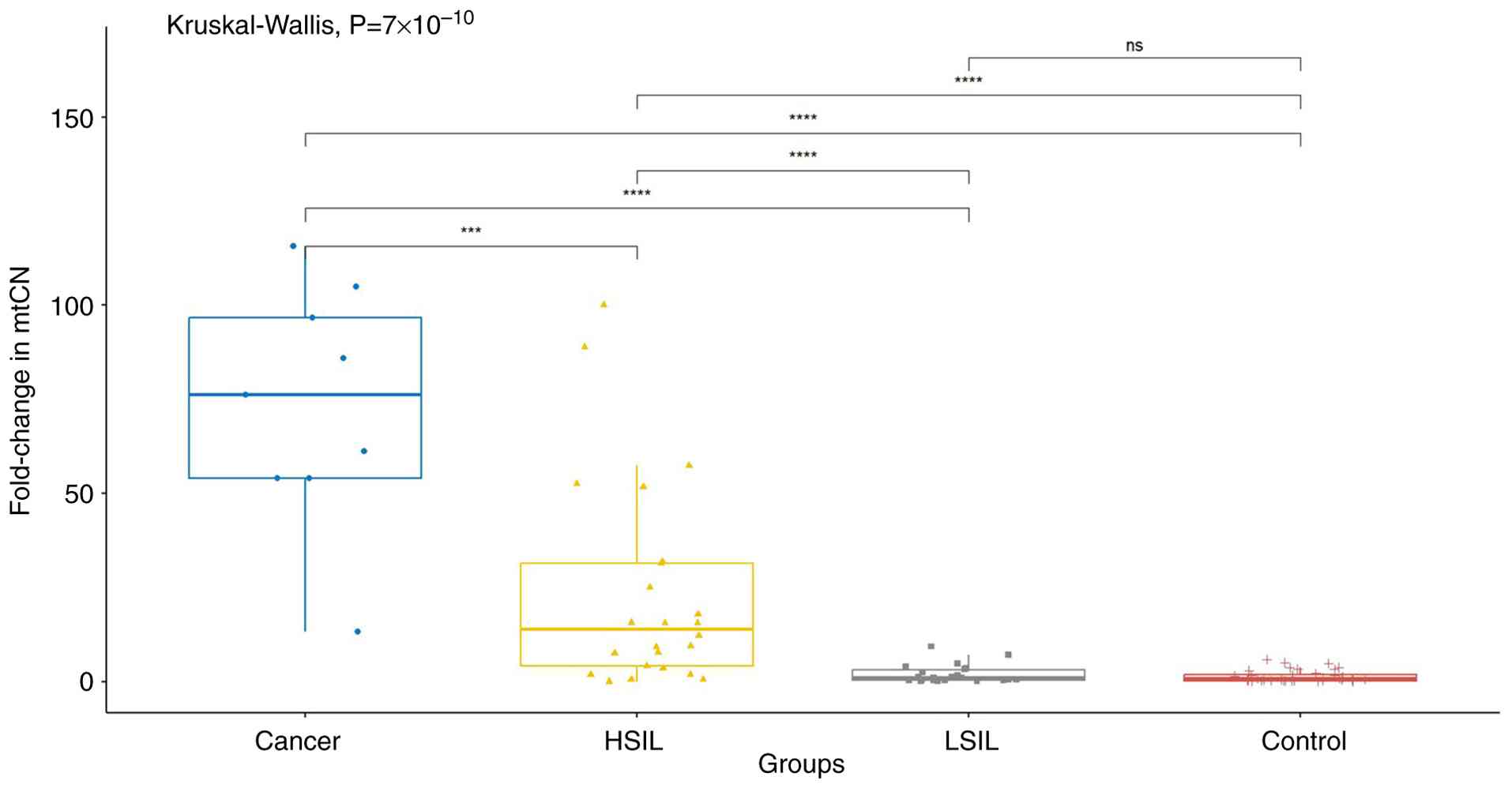

Comparison of mtCN results according

to cervical disease category, HPV status and smoking status

Subsequent mtCN analyses were performed only in

samples with adequate DNA yield and quality (n=84), after exclusion

of 16 samples; Table I summarizes

the baseline characteristics of the full enrolled cohort (n=100).

In the first analysis, the groups were compared according to

disease category. A statistically significant difference was

identified among the groups in terms of mtCN (P<0.001). Post hoc

analysis revealed significant differences between the cancer and

control groups, the cancer and HSIL groups, the control and HSIL

groups, the cancer and LSIL groups, and the HSIL and LSIL groups

(P<0.001). However, no significant difference was detected

between the control and LSIL groups. In addition, when HSIL and

cancer cases were combined into a high-risk group and LSIL and

control group patients were combined into a low-risk group, a

statistically significant difference in mtCN was observed between

these groups (P<0.001; Fig.

1).

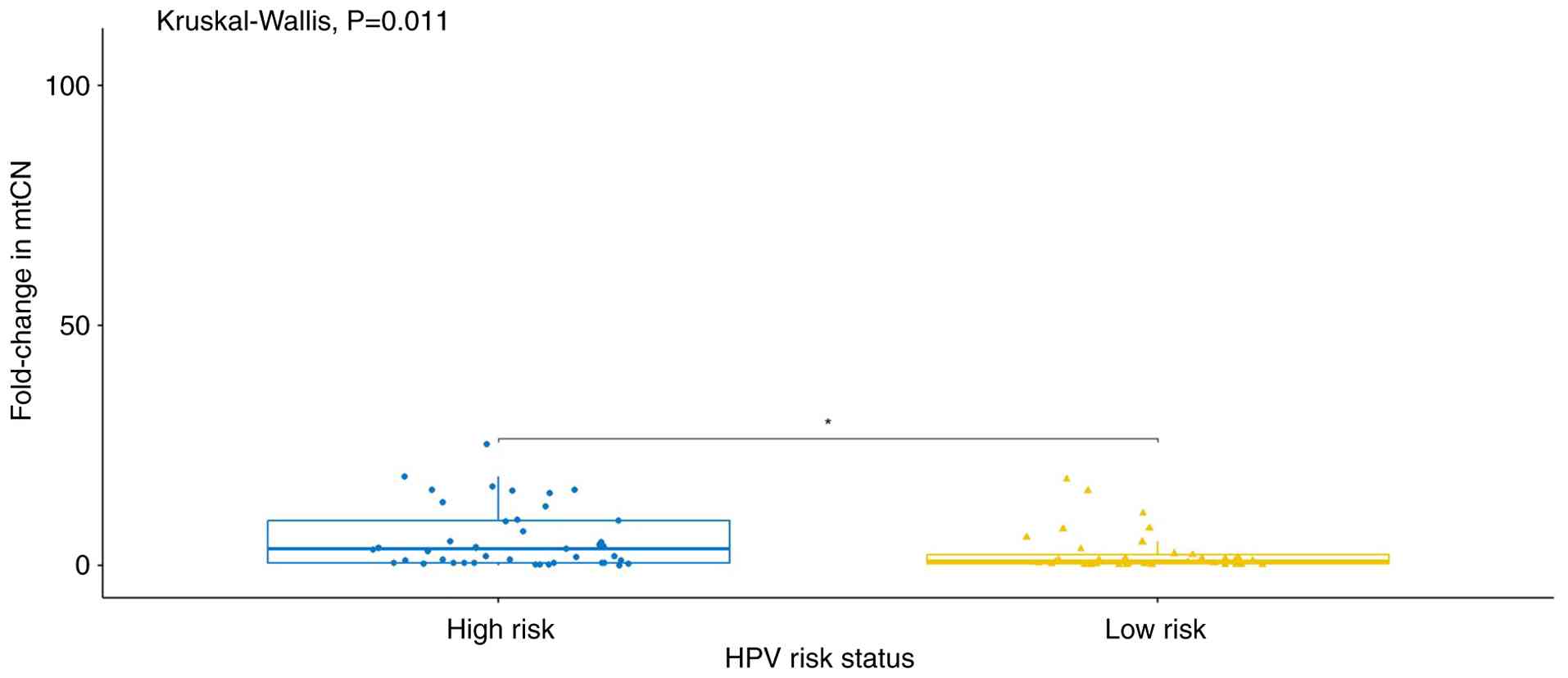

In the second analysis, the participants were

categorized according to their HPV status. Patients positive for

HPV16 and/or HPV18 were classified as the high-risk HPV group,

while patients positive for other HPV types or with no detectable

HPV infection were classified as the low-risk HPV group. A

statistically significant difference in mtDNA copy number was

observed between these groups (P<0.05; Fig. 2).

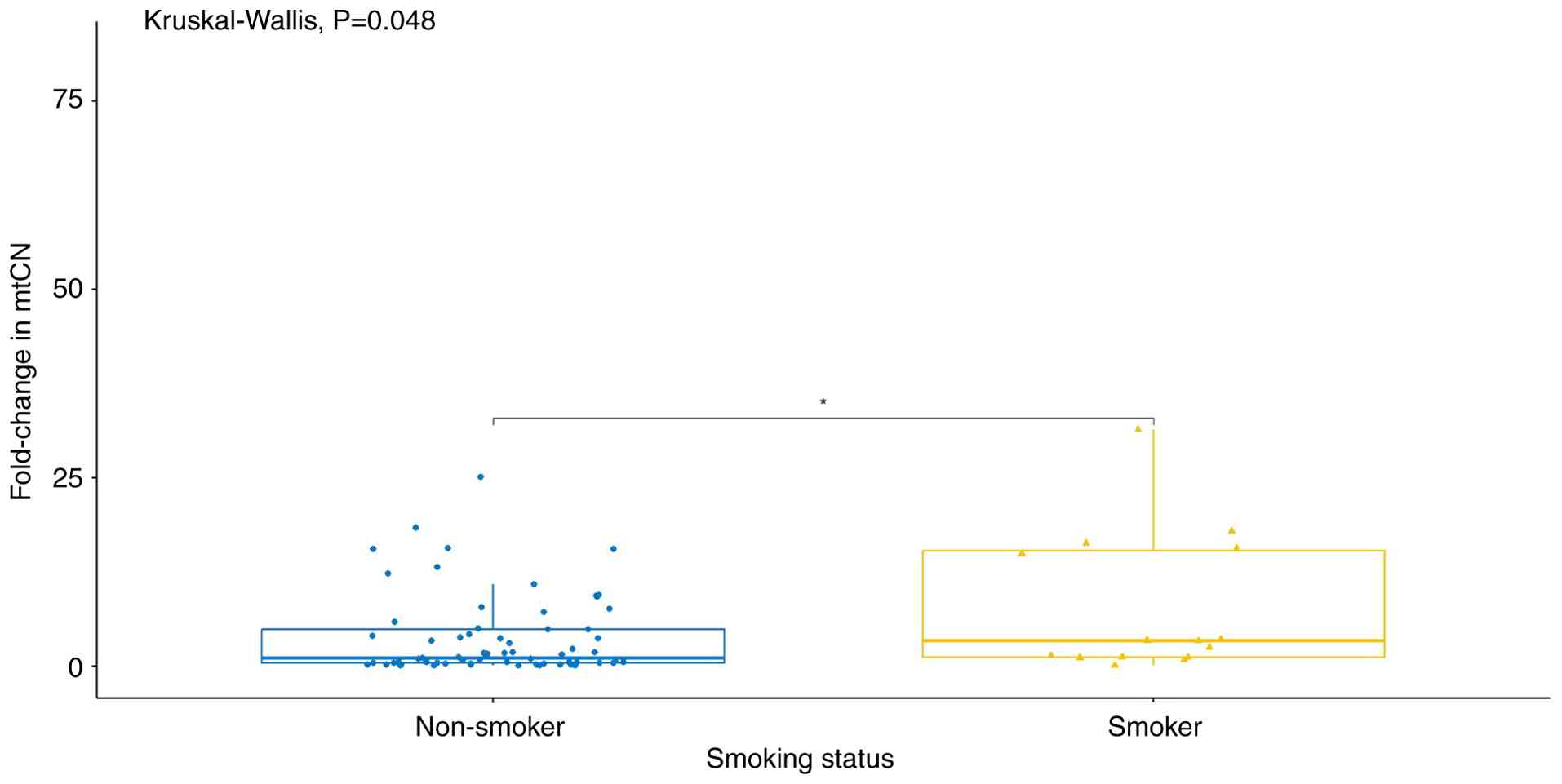

In the third analysis, the mtCN was compared

according to smoking status. A statistically significant difference

was detected between non-smokers and smokers (P<0.05; Fig. 3).

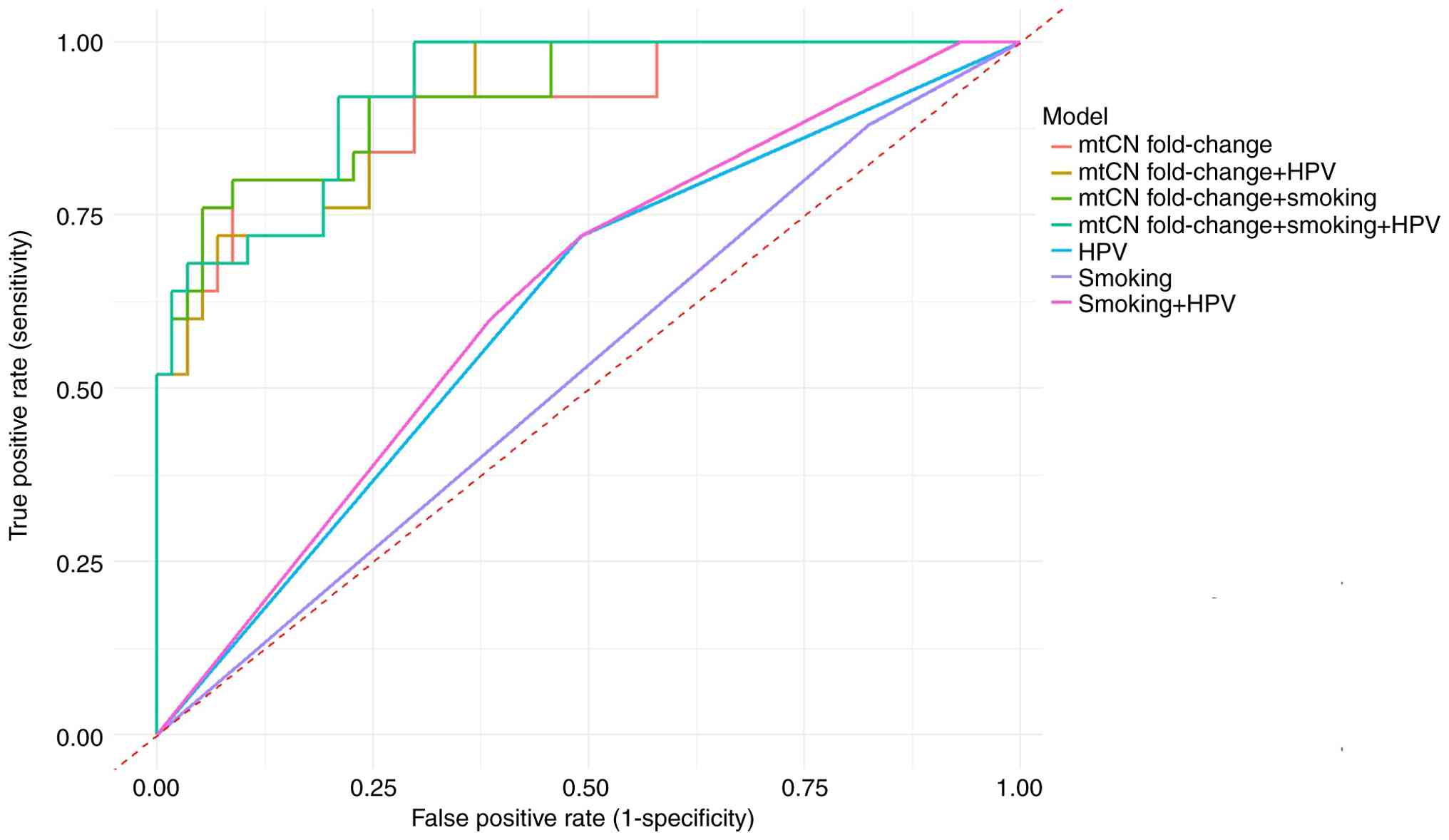

Development of a model for prediction

of high-risk and low-risk cervical lesions

A prediction model was developed to distinguish

between high-risk and low-risk cervical disease groups. Prior to

model development, outlier detection was performed using the local

outlier factor method, and extreme values were excluded from the

analysis. Logistic regression analysis was implemented for model

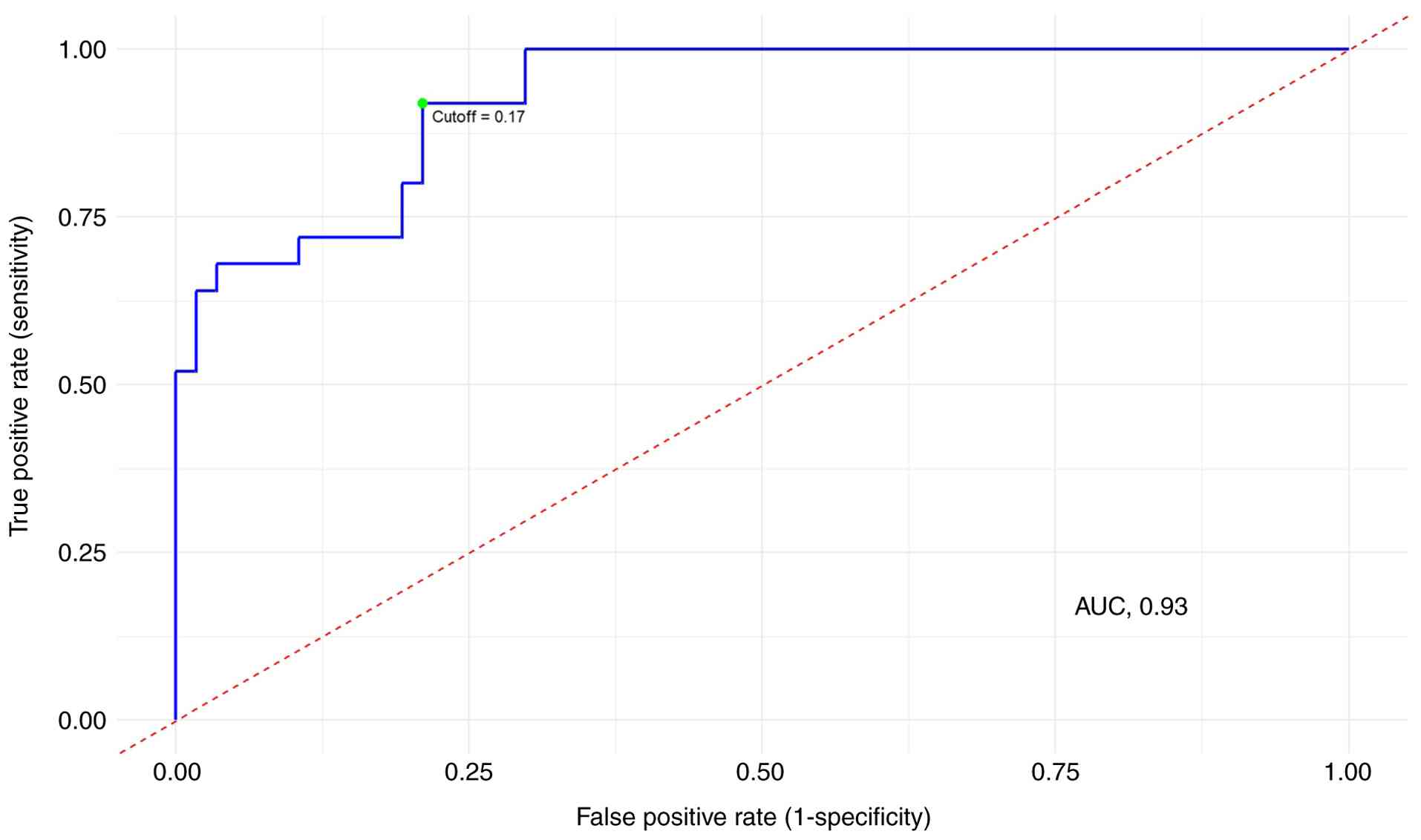

development. Among the seven tested models, the triple model

incorporating mtCN fold change, smoking status and HPV status

showed the highest discriminative performance (AUC=0.93; Figs. 4 and 5). As the study restricted the ages of the

participants to a narrow range of between 45 and 65 years, age was

excluded from the modeling process.

Among the predictors included in the model, mtCN

changes were identified as the strongest predictor of risk status.

Smoking status and HPV status were evaluated as independent

variables, demonstrated weaker associations and did not reach

statistical significance (Table

II). The triple model, including all three variables,

demonstrated a superior overall performance. Consequently, this

specific model was selected as the final predictive model. The

optimal threshold value for successful differentiation using the

triple model was determined, and a cutoff value of 0.17 was found

to be optimum (Fig. 5). At this

cutoff, the triple model exhibited a sensitivity of 79% and

specificity of 92% (Table

III).

| Table II.Triple logistic regression model

results. |

Table II.

Triple logistic regression model

results.

|

|

|

| 95 CI% |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | P-values | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper |

|---|

| Intercept | <0.001 | 1.146 | 1.038 | 1.471 |

| mtCN fold

change | 0.003 | 3.551 | 3.013 | 4.548 |

| HPV | 0.083 | 1.426 | 1.062 | 5.108 |

| Smoking | 0.203 | 1.081 | 1.002 | 2.522 |

| Table III.Performance metrics outcomes of all

models. |

Table III.

Performance metrics outcomes of all

models.

| Model

variables | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive

value |

|---|

| mtCN fold

changea | 88 | 91 | 80 | 91 |

| HPVb | 58 | 51 | 72 | 81 |

| mtCN fold change +

smokinga | 88 | 92 | 80 | 91 |

| mtCN fold change +

HPVa | 81 | 76 | 92 | 96 |

| mtCN fold change +

HPV + smokinga | 83 | 79 | 92 | 95 |

Discussion

In the present study, the relationship between mtCN

variations and the progression of CIN to cervical cancer was

investigated. The findings provide important insights and are

consistent with previous studies on mtDNA alterations in various

cancer types. They also expand upon previous studies by providing a

comprehensive understanding of the role of mtCN changes across the

CIN spectrum. Notably, statistically significant increases in mtCN

were observed with increasing disease severity, culminating in

cervical cancer.

Previous studies have reported increased mtCN in

cervical disease. In a cohort consisting exclusively of high-risk

HPV-positive women, Sun et al (18) observed that mtCN levels in

exfoliated cervical cells were higher in women with cervical cancer

compared with cancer-free controls, supporting a potential role for

mtCN alterations in cervical carcinogenesis. Similarly, based on

tissue-based analyses, Warowicka et al (19) reported that the mtCN in HSIL and

carcinoma is elevated compared with that in LSIL (19). In the cohort of the present study,

mtCN increased in a stepwise manner with increasing histological

severity, which was consistent with these previous

observations.

Al-Awadhi et al (20) reported elevated mtCN in cervical

abnormalities irrespective of HPV status, suggesting an adaptive

response to mitochondrial stress. The present study extends the

results provided in the literature in the following three aspects:

i) mtCN was evaluated across the full CIN spectrum in tissue, that

is, in normal, CIN1, CIN2/3 and cancerous tissues, rather than by

the comparison of only extreme disease categories; ii) HPV status

was explicitly incorporated, demonstrating that HPV positivity

amplifies the stepwise increase in mtCN; and iii) these findings

were integrated into a joint predictive framework combining mtCN

with HPV status and smoking, with defined operating characteristics

(threshold, 0.17; sensitivity, 79%; specificity, 92%), thereby

positioning mtCN within a clinically oriented risk-stratification

context (Fig. 5).

High-risk HPV oncoproteins establish a persistent

pro-oxidant state that perturbs mitochondrial homeostasis.

E6/E7-driven oxidative stress increases ROS production and DNA

damage in infected epithelia; since mtDNA is in close proximity to

the respiratory chain, lacks protective histones and has limited

repair capacity, it is particularly susceptible to damage. Such

mitochondrial damage can activate mitochondrial biogenesis

pathways, including the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

g coactivator-1a (PGC-1α)/nuclear respiratory factor 1

(NRF-1)/mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) axis, leading

to an increase in mtCN as a compensatory response to maintain

bioenergetic function. These mechanisms, described in previous

reviews of HPV-related oxidative-stress and mitochondrial biology,

provide a biologic rationale for the stepwise increase in mtCN

observed with increasing cervical disease severity and for the

higher mtCN detected in HPV-positive samples in the present cohort

(18,25,26).

Previous studies have reported both increased and

decreased mtCN across different tumor types (27). Elevated mtCN has been observed in

breast, bladder, esophageal, head and neck squamous, kidney and

liver cancers, with lung carcinoma as a notable exception, when

compared with non-tumorous tissues (28). By contrast, reduced mtCN has been

reported in kidney clear cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma

and myeloproliferative tumors (29). The association between mtCN

variations and the risk of cancer progression has also been

documented. A meta-analysis by Hu et al (30) demonstrated a significant association

between increased mtCN and the risk of lymphoma, melanoma and

breast cancer, whereas an inverse relationship was observed for

hepatic carcinoma. These divergent results suggest that mtCN may

increase as a compensatory response to mitochondrial damage via

increased mitochondrial biogenesis, whereas decreased mtCN may

occur when mitochondrial damage becomes excessive and damaged cells

are eliminated by mitophagy and increased cellular turnover. Which

of these occurs depends on tissue context, tumor metabolic demands

and disease stage. In cervical pathology, syntheses of recent

evidence indicate a tendency toward mtCN elevation in high-grade

lesions and cervical cancer, particularly in HPV-positive settings,

consistent with compensatory mitochondrial biogenesis under chronic

ROS-induced stress. The findings of the present study align with

this context-dependence and position cervical disease on the

‘increased mtCN’ side of this bidirectional framework (20,26).

Given the high prevalence of smoking in Türkiye, a

comparison between cervical tissue samples from smokers and

non-smokers was performed in the current study. Consistent with

findings from large epidemiologic cohorts, smoking has been

associated with a reduction in leukocyte mtCN (31,32),

generally interpreted as systemic depletion associated with

oxidative stress. However, in the present tissue-based analysis,

upregulated mtCN was observed in the cervical samples of smokers.

This apparent discrepancy supports a tissue-blood dissociation,

whereby localized oxidative stress and increased bioenergetic

demands in pre-neoplastic or tumor tissue may promote compensatory

mitochondrial biogenesis via the PGC-1α/NRF-1/TFAM axis (33). This interpretation is consistent

with previous literature on cervical cancer, which has reported the

elevation of mtCN in high-grade cervical lesions or cervical cancer

(20,26). It is important to note that this

stratified, within-tissue observation, when combined with the

CIN-graded analysis and the integrated predictive model combining

mtCN, HPV status and smoking, constitutes a novel contribution of

the present study. Together, these findings refine the

interpretation of mtCN as a biomarker for risk stratification in

HPV-related cervical disease.

The potential of mtCN as a biomarker for cancer

prognosis is well-documented. Distinct mtCN levels have been shown

to differentiate control populations from patients with solid

tumors and other diseases (9,23).

Despite this, the routine clinical assessment of mtCN is not

possible due to the lack of a standardized method (34). Although the qPCR technique remains

the gold standard for mtCN quantification, variations in its

application among different laboratories contribute to inconsistent

results. In particular, differences in reference genes, which often

vary based on the sample type and disease context, complicate

standardization (28,34). An additional technical limitation is

that the nuclear genome can replicate a significant portion of the

mtDNA genome, creating nuclear mtDNA segments that may interfere

with mtCN measurement (35,36). This genetic overlap necessitates the

careful selection of mtDNA target regions to avoid the

co-amplification of these pseudogenes and ensure accurate mtCN

quantification (36,37). In the present study, mtCN was

demonstrated to be a significant biomarker for the progression of

CIN to cervical cancer. The observed mtCN alterations in cervical

tissues, notably the increased mtCN in HPV-positive cases and among

smokers, further highlight its potential utility in clinical

practice. However, the lack of standardized methods for mtCN

assessment underscores the requirement for the development of

consistent and reproducible techniques for clinical implementation.

The present study contributes to the growing body of evidence

supporting the importance of mtCN as a biomarker and emphasizes

that standardized protocols are necessary to enhance its utility in

cancer prognosis and screening.

The interaction between mtCN and HPV positivity was

evaluated using the Wald test within logistic regression models,

which is similar to the analytical approach previously described by

Sun et al (18). Logistic

regression models have also been employed in other studies

investigating mtCN in various cancer types, for example, in a study

on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in which mtCN modeling in

leukocytes was performed (38). In

the present study, ROC curve analysis was used to compare all

possible model combinations. Among these, the triple model

incorporating mtCN fold-change, smoking status and HPV status

demonstrated the strongest classification performance. Notably,

mtCN fold-change alone was the strongest contributor to the model.

The ROC curve analysis for the triple model indicates a

discrimination threshold of 0.17, corresponding to a sensitivity

and specificity of 79 and 92%, respectively.

Several limitations of the present study must be

acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small, which

may limit the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, larger

studies are required to validate these results and provide more

robust evidence. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study

with single-time-point sampling precludes the determination of

whether mtCN alterations are a cause or a consequence of CIN

progression. Prospective longitudinal cohort studies with serial

cervical tissue sampling are required to clarify the temporal and

causal relationship between mtCN dynamics and cervical disease

development. Furthermore, although qPCR is considered the gold

standard for mtCN quantification, the lack of standardized

protocols across laboratories may introduce variability and limit

comparability. The development of standardized methods for mtCN

assessment will be essential to ensure consistency and

reproducibility in clinical settings. In addition, the cancer group

included only 8 patients; consequently, the power analysis was

conducted by combining the HSIL and cancer groups into a single

high-risk category and comparing this with a low-risk category

combining the LSIL and normal groups. While this approach ensured

sufficient statistical power to detect overall differences in mtCN,

it may obscure variations specific to invasive cancer. Therefore,

the results should be interpreted with caution, as this grouping

limits the ability to draw distinct conclusions with regard to the

cancer subgroup alone. Finally, the study did not account for all

potential confounding factors, such as environmental exposures and

genetic susceptibility, that may influence mtCN levels. Future

studies should consider these variables to provide a more

comprehensive understanding of the factors affecting mtCN in

cervical cancer.

In conclusion, the present study provides compelling

evidence that alterations in mtCN are significantly associated with

the progression of CIN to cervical cancer. The findings highlight

the potential of mtCN as a biomarker for cervical cancer risk

assessment, particularly in HPV-positive cases. However, larger

longitudinal studies with standardized protocols are essential to

validate these results and facilitate their clinical translation.

Overall, the insights gained from the study contribute to the

growing body of evidence supporting the importance of mtCN in

cancer biology and underscore that it is necessary to continue to

investigate its role in tumorigenesis and its potential use as a

diagnostic tool.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Miss Merve Ulak

(Genetic Diseases Evaluation Center, Ankara Etlik City Hospital)

for their assistance with sample processing and laboratory

workflows; Miss Esra Cesur (Genetic Diseases Evaluation Center,

Ankara Etlik City Hospital), Miss Seyda Gurevin (Genetic Diseases

Evaluation Center, Ankara Etlik City Hospital) and Miss Merve

Karademir (Genetic Diseases Evaluation Center, Ankara Etlik City

Hospital) for their support in DNA extraction and qPCR

procedures.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

IO and HBE contributed to conceptualization, formal

analysis, investigation and drafting the original manuscript. MTA

performed statistical analysis, data curation (systematic data

retrieval, clinical record verification, database management),

designed scientific figures and assisted with graphical data

presentation. OO contributed to clinical methodology, patient

recruitment, clinical evaluation and tissue acquisition. FSD

contributed to formal analysis and methodology. ECD contributed to

analysis and interpretation of data and manuscript review and

editing. AYT contributed to patient recruitment, clinical

evaluation and tissue acquisition. HLK contributed to

conceptualization, and manuscript review and editing. IO and HBE

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Ankara Etlik City Hospital (approval No: AEŞH-EK1-2023-015; date,

22.03.2023). All participants provided written informed consent

prior to inclusion in the study. The study was conducted in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

İzzet Özgürlük, ORCID: 0000-0002-9553-9265; Haktan

Bağış Erdem, ORCID: 0000-0002-4391-1387; Mustafa Tarik Alay, ORCID:

0000-0002-1563-2292; Okan Oktar, ORCID: 0000-0002-9696-7886;

Firdevs Şahin-Duran, ORCID: 0000-0001-9244-9590; Ezgi Çevik-Demir,

ORCID: 0000-0003-2612-3861; Aysu Yeşim Tezcan, ORCID:

0000-0002-4763-6546; Hüseyin Levent Keskin, ORCID:

0000-0002-2268-3821.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CIN

|

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

|

|

LSIL

|

low-grade squamous intraepithelial

lesion

|

|

HSIL

|

high-grade squamous intraepithelial

lesion

|

|

mtDNA

|

mitochondrial DNA

|

|

mtCN

|

mitochondrial DNA copy number

|

|

nDNA

|

nuclear DNA

|

|

HPV

|

human papillomavirus

|

|

FFPE

|

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

|

|

qPCR

|

quantitative polymerase chain

reaction

|

|

ΔCq

|

difference in quantification cycle

|

|

ND1

|

NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1

|

|

HBB

|

hemoglobin subunit β

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth

A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J and Sparén P: HPV vaccination and

the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 383:1340–1348.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Coquillard G, Palao B and Patterson BK:

Quantification of intracellular HPV E6/E7 mRNA expression increases

the specificity and positive predictive value of cervical cancer

screening compared to HPV DNA. Gynecol Oncol. 120:89–93. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Woodman CB, Collins SI and Young LS: The

natural history of cervical HPV infection: unresolved issues. Nat

Rev Cancer. 7:11–22. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Maver P and Poljak M: Primary HPV-based

cervical cancer screening in Europe: implementation status,

challenges, and future plans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 26:579–583.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Papa S and Skulachev V: Reactive oxygen

species, mitochondria, apoptosis and aging. Mol Cell Biochem.

197:305–319. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gustafsson CM, Falkenberg M and Larsson

NG: Maintenance and expression of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. Annu

Rev Biochem. 85:133–160. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Johns DR: Seminars in medicine of the Beth

Israel Hospital, Boston. Mitochondrial DNA and disease.

Mitochondrial DNA and disease. N Engl J Med. 333:638–644. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wallace DC: Mitochondria and cancer. Nat

Rev Cancer. 12:685–698. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yakes FM and Van Houten B: Mitochondrial

DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA

damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 94:514–519. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Erdem HB, Ceylan AC, Sahin I, Sever-Erdem

Z, Citli S and Tatar A: Mitochondrial DNA copy number alterations

in familial mediterranean fever patients. Bratisl Lek Listy.

119:425–428. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Öğütlü H, Esin İS, Erdem HB, Tatar A and

Dursun OB: Mitochondrial DNA copy number is associated with

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Danub.

32:168–175. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Öğütlü H, Esin IS, Erdem HB, Tatar A and

Dursun OB: Mitochondrial DNA copy number may be associated with

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder severity in treatment: A

one-year follow-up study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 25:37–42.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lee HC and Wei YH: Mitochondrial

biogenesis and mitochondrial DNA maintenance of mammalian cells

under oxidative stress. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 37:822–834. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shokolenko I, Venediktova N, Bochkareva A,

Wilson GL and Alexeyev MF: Oxidative stress induces degradation of

mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:2539–2548. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Abd Radzak SM, Mohd Khair SZN, Ahmad F,

Patar A, Idris Z and Yusoff AA: Insights regarding mitochondrial

DNA copy number alterations in human cancer. Int J Mol Med.

50:1042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cruz-Gregorio A, Manzo-Merino J,

Gonzaléz-García MC, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Medina-Campos ON, Valverde

M, Rojas E, Rodríguez-Sastre MA, García-Cuellar CM and Lizano M:

Human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 early-expressed proteins

differentially modulate the cellular redox state and DNA damage.

Int J Biol Sci. 14:21–35. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sun W, Qin X, Zhou J, Xu M, Lyu Z, Li X,

Zhang K, Dai M, Li N and Hang D: Mitochondrial DNA copy number in

cervical exfoliated cells and risk of cervical cancer among

HPV-positive women. BMC Women's Health. 20:1392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Warowicka A, Kwasniewska A and

Gozdzicka-Jozefiak A: Alterations in mtDNA: A qualitative and

quantitative study associated with cervical cancer development.

Gynecol Oncol. 129:193–198. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Al-Awadhi R, Alroomy M, Al-Waheeb S and

Alwehaidah MS: Altered mitochondrial DNA copy number in cervical

exfoliated cells among high-risk HPV-positive and HPV-negative

women. Exp Ther Med. 26:5212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fleider LA, de Los Ángeles Tinnirello M,

Gómez Cherey F, García MG, Cardinal LH, García Kamermann F and

Tatti SA: High sensitivity and specificity rates of

cobas® HPV test as a primary screening test for cervical

intraepithelial lesions in a real-world setting. PLoS One.

18:e02797282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mambo E, Chatterjee A, Xing M, Tallini G,

Haugen BR, Yeung SCJ, Sukumar S and Sidransky D: Tumor-specific

changes in mtDNA content in human cancer. Int J Cancer.

116:920–924. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Schwertman NC, Owens MA and Adnan R: A

simple more general boxplot method for identifying outliers.

Computational statistics & data analysis. 47:165–174. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Letafati A, Taghiabadi Z, Zafarian N,

Tajdini R, Mondeali M, Aboofazeli A, Chichiarelli S, Saso L and

Jazayeri SM: Emerging paradigms: unmasking the role of oxidative

stress in HPV-induced carcinogenesis. Infect Agent Cancer.

19:302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pereira IOA, Silva NNT, Lima AA and da

Silva GN: Qualitative and quantitative changes in mitochondrial DNA

associated with cervical cancer: A comprehensive review. Environ

Mol Mutagen. 65:143–152. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lin CS, Wang LS, Tsai CM and Wei YH: Low

copy number and low oxidative damage of mitochondrial DNA are

associated with tumor progression in lung cancer tissues after

neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg.

7:954–958. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Moraes CT: What regulates mitochondrial

DNA copy number in animal cells? Trends Genet. 17:199–205. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tang Y, Schon EA, Wilichowski E,

Vazquez-Memije ME, Davidson E and King MP: Rearrangements of human

mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA): New insights into the regulation of

mtDNA copy number and gene expression. Mol Biol Cell. 11:1471–1485.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hu L, Yao X and Shen Y: Altered

mitochondrial DNA copy number contributes to human cancer risk:

Evidence from an updated meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 6:358592016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Çakir M: Evaluation of smoking and

associated factors in Turkey. Iran J Public Health. 52:766–772.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wu S, Li X, Meng S, Fung T, Chan AT, Liang

G, Giovannucci E, De Vivo I, Lee JH and Nan H: Fruit and vegetable

consumption, cigarette smoke, and leukocyte mitochondrial DNA copy

number. Am J Clin Nutr. 109:424–432. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Abu Shelbayeh O, Arroum T, Morris S and

Busch KB: PGC-1α is a master regulator of mitochondrial lifecycle

and ROS stress response. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:10752023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Longchamps RJ, Castellani CA, Yang SY,

Newcomb CE, Sumpter JA, Lane J, Grove ML, Guallar E, Pankratz N,

Taylor KD, et al: Evaluation of mitochondrial DNA copy number

estimation techniques. PLoS One. 15:e02281662020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hazkani-Covo E, Zeller RM and Martin W:

Molecular poltergeists: Mitochondrial DNA Copies (numts) in

sequenced nuclear genomes. PLoS Genet. 6:e10008342010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li B, Kalinowski P, Kim B, Pauls AD and

Poburko D: Emerging methods for and novel insights gained by

absolute quantification of mitochondrial DNA copy number and its

clinical applications. Pharmacol Ther. 232:1079952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Filograna R, Mennuni M, Alsina D and

Larsson NG: Mitochondrial DNA copy number in human disease: The

more the better? FEBS Lett. 595:976–1002. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang L, Lv H, Ji P, Zhu X, Yuan H, Jin G,

Dai J, Hu Z, Su Y and Ma H: Mitochondrial DNA copy number is

associated with risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in

Chinese population. Cancer Med. 7:2776–2782. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|