Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed

cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among females

worldwide, with an estimated 1.7 million cases and 521,900 deaths

in 2012 (1,2). One third of novel cancer diagnoses in

females are breast cancer and one in eight women will be diagnosed

with breast cancer, with a lifetime risk of mortality due to breast

cancer of 3.4% (3). Systematic

chemotherapy plays a critical role in treatment of breast cancer.

Doxorubicin (Dox) treatment is one of the established clinically

effective strategies for the treatment of breast cancer, and

primarily functions by inhibiting topoisomerases and intercalating

into the DNA double helix to interfere with DNA uncoiling, which

induces cell death (4). However,

the efficacy of Dox is limited by its drug resistance as well as

side-effects. Increasing research indicates that multidrug

resistance (MDR) contributes to the failure of chemotherapeutic

drugs as treatment (5). There are

at least two molecular pumps in tumor cell membranes, multi-drug

resistance-associated protein (MRP) and P-glycoprotein (P-gp), to

expel the antitumor drugs out of the cancer cells and attenuate the

drug effect. Some P-gp inhibitors used to reverse MDR were able to

enhance chemosensitivity in resistant cells but caused cytotoxicity

and a number of complications (6).

Therefore, finding key target molecules and novel therapeutic

strategies to overcome resistance and diminish the side-effects of

chemotherapeutic agents are the main goals of any ideal cancer

treatment protocol.

The protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a key tumor

suppressor that regulates signaling pathways with a high relevance

in human cancer (7). Consistent

with its role as a tumor suppressor, PP2A plays a critical role in

the regulation of survival, cell cycle progression, and

differentiation by negatively regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway and

dephosphorylating and inactivating ERK and MEK1 family kinases

(8). Aberrant expression,

mutations, and somatic alterations of the PP2A scaffold and

regulatory subunits are frequently found in human breast, lung,

colon and skin cancers (9).

Therefore, reactivation of PP2A activity based on its tumor

suppressor properties is considered to be an attractive therapeutic

strategy for human cancer treatment (10,11).

Cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A

(CIP2A), a human oncoprotein that stabilizes c-Myc by inhibiting

PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of Myc at serine 62 (8). CIP2A promotes the proliferation and

aggressiveness of several cancer types including head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma, colon, gastric, breast, prostate, tongue,

lung, cervical cancer and acute myeloid leukemia (8,12–15).

In 2011, Choi et al (16)

reported that CIP2A expression is associated with Dox resistance.

CIP2A has been found to involve in regulating MDR of cervical

adenocarcinoma upon chemotherapy by enhancing MDR gene encoded P-gp

expression through E2F1 (17).

Thus, effective and discerning CIP2A inhibitors would be beneficial

for adjuvant therapy to reduce the development of cancer resistance

to Dox and reactivation of PP2A activity in breast cancer.

Cucurbitacins are tetracyclic triterpene natural

products that are mainly found in the members of family

Cucurbitaceae. It has been used as a medicinal herb because it

exhibits different biological activities such as anti-diabetic,

anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities against different

cancer cell lines (18).

Cucurbitacin B (CuB) is one of the most abundant forms of

cucurbitacins which is shown to inhibit the growth of numerous

human cancer cell lines such as breast, colon, leukemia, hepatic,

pancreatic and glioblastoma, and xenografts (19–21).

The effect of CuB on Dox-resistant breast cancer cells has not been

previously evaluated. The aim of the present study was to

investigate antitumor effects and possible mechanisms of CuB on Dox

resistant human breast cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Cucurbitacin B (CuB) with a purity of up to 98% was

purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai,

China). CuB was dissolved in dimethyl sulf-oxide (DMSO;

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a stock solution of 40 mM and

stored at −20°C. Doxorubicin (Dox) was purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell culture

The human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 was obtained

from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA,

USA). Human Dox-resistant breast cancer cell line MCF-7/Adriamycin

(MCF-7/Adr) was purchased from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of

Sciences (Shanghai, China). MCF-7 cells were maintained in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone

Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT, USA) and antibiotics. MCF-7/Adr

cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum. Additionally, 2 µg/ml Adriamycin was added

into MCF-7/Adr medium. All the cells were cultured in a humidified

atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cytotoxic assay and cell viability

Cells were seeded into a 96-well plate and

pre-cultured for 24 h, then treated with CuB for 24 h. Cell

cytotoxicity was determined by MTT assay. The absorbance was

measured at 490 nm by automated micro-plated reader (BioTek

Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA), and the inhibition rate was

calculated as followed: Inhibition rate (%) = (average

A490 of the control group − average A490 of

the experimental group)/(average A490 of the control

group − average A490 of the blank group) × 100%. Cell

viability was estimated by trypan blue dye exclusion (22).

Soft-agar colony formation assay

Cells were suspended in 1 ml of RPMI-1640 containing

0.3% low-melting-point agarose (Amresco, Cleveland, OH, USA) and

10% FBS, and plated on a bottom layer containing 0.6% agarose and

10% FBS in 6-well plate in triplicate. After 2 weeks, plates were

stained with 0.2% gentian violet and the colonies were counted

under a light microscope (23).

Apoptosis determination by DAPI

staining

Approximately 2×105 cells/well of cells

in a 12-well plate was treated with CuB for 24 h. Then cells in

each treatment and control were stained by DAPI and examined and

photographed by fluorescence microscopy as described (24).

Western blot analysis

Cell pellets were lysed in RIPA buffer containing 50

mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% NP-40,

1 mM DTT, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich)

and 1% protease inhibitors cocktail (Merck). Protein extracts were

quantitated and loaded on 8–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate

poly-acrylamide gel, electrophoresed and transferred to a PVDF

membrane (Millipore, Kenilworth, NJ, USA). The membrane was

incubated with primary antibody, washed, and incubated with

horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody

(Pierce). Detection was performed by using a chemiluminescent

western detection kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA)

(25). The antibodies used were

anti-MRP1, anti-CIP2A, anti-Akt, anti-pAkt (Ser473) (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-casp-9, anti-casp-3,

anti-PARP, anti-PP2A, anti-ERK1/2, anti-pERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204),

(Cell Signaling Technology), anti-P-gp (Abcam), and anti-GAPDH

(AB10016; Sangon Biotech, Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

PP2A activity assay

PP2A immunoprecipitation phosphatase assay kit

(Upstate-Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) was used to measure

phosphate release as an index of phosphatase activity according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 100 µg protein

isolated from cells was incubated with 4 µg anti-PP2A

monoclonal antibody overnight. A total of 40 µl of protein A

agarose beads were added and the mixture was incubated at 4°C for 2

h. Subsequently, the beads were collected and washed three times

with 700 µl of ice-cold TBS and one time with 500 µl

Ser/Thr assay buffer. The beads were further incubated with 750 mM

phosphopeptide in assay buffer for 10 min at 30°C with constant

agitation. A total of 100 µl of Malachite Green Phosphate

detection solution was added and the absorbance at 650 nm was

measured on a microplate reader (26).

Transfection of siRNA

Two siRNAs targeting CIP2A were designed and

synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd., (Shanghai, China)

referred to as siRNA1 and siRNA2. The siRNA sequences were as

follows: 5′-CUGUGGUUGUGUU UGCACUTT-3′ (CIP2A siRNA1),

5′-ACCAUUGAUAUCCUUAGAATT-3′ (CIP2A siRNA2),

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ [negative control (NC) siRNA].

Using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA,

USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol, MCF-7/Adr cells were

transfected with 100 nM siRNA. In addition, 48 h after

transfection, the cells were then harvested for western blot

analysis and cell viability.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times

and the data are presented as the mean ± SD unless noted otherwise.

Differences between data groups were evaluated for significance

using Student's t-test of unpaired data or one way analysis of

variance and Bonferroni post-test. P-values <0.05 indicate

statistical significance.

Results

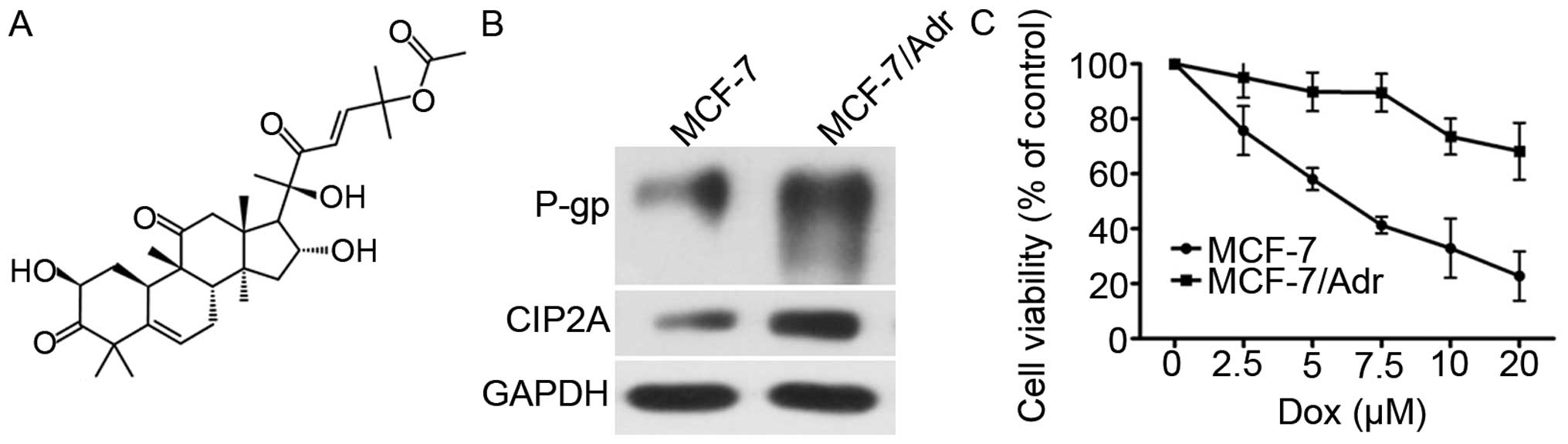

Chemical structure of CuB and

characterization of MCF-7 and MCF-7/Adr cells

The chemical structure of CuB is shown in Fig. 1A. First, the P-gp and CIP2A

expression level was compared between MCF-7/Adr and MCF-7 cells by

western blot analysis, which confirmed P-gp and CIP2A

overexpression in MCF-7/Adr cells (Fig.

1B). MCF-7 and MCF-7/Adr cells were exposed to various

concentrations of Dox (2.5–80 µM) for 24 h. The half-maximal

inhibitory concentration (IC50) of Dox against MCF-7

cells is 6.2 µM, while IC50 of Dox against

MCF-7/Adr cells is 37.78 µM. As shown in Fig. 1C, the Dox cytotoxicity was higher in

MCF-7 cells than in MCF-7/Adr cells.

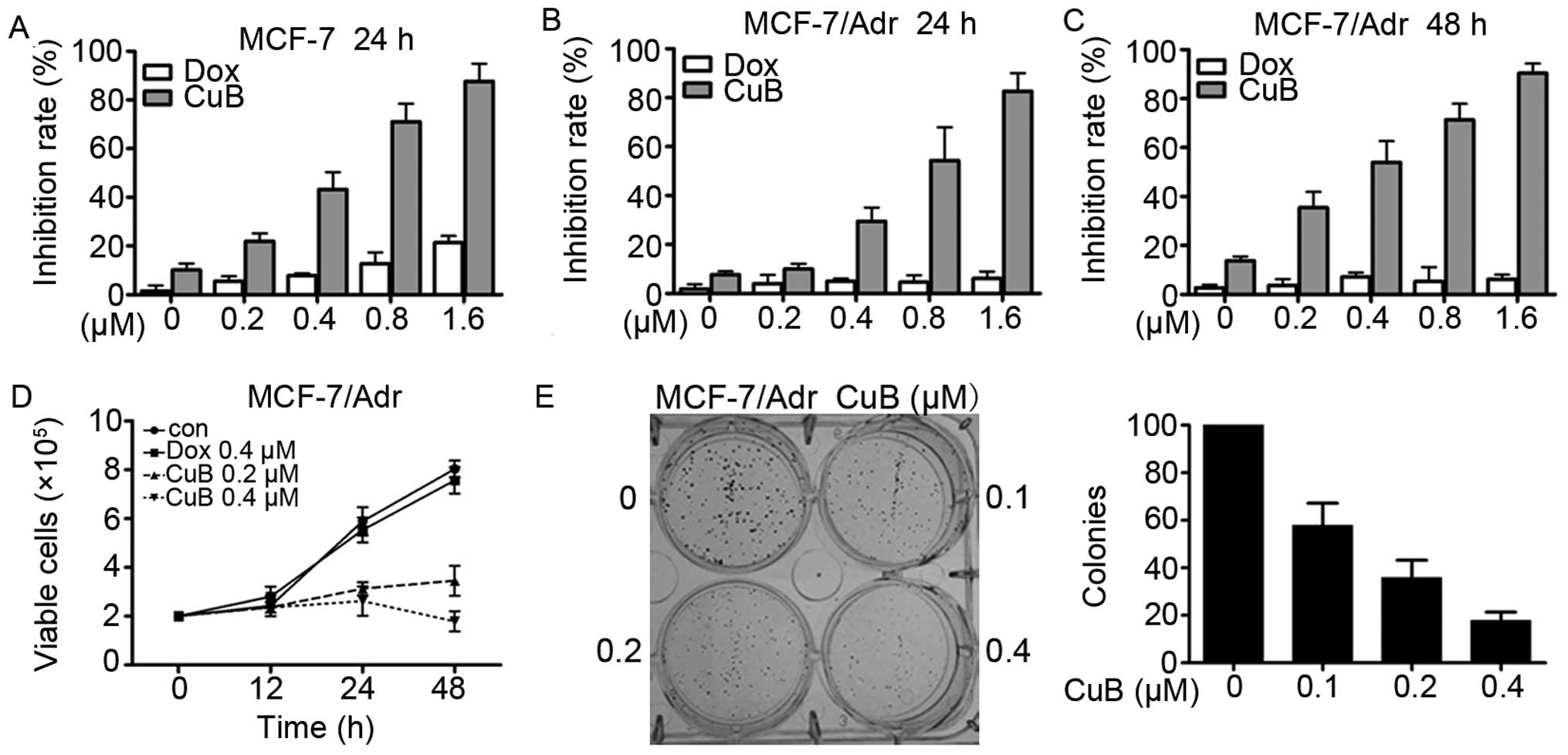

Effects of CuB on MCF-7 and MCF-7/Adr

breast cancer cells

MCF-7 and MCF-7/Adr cells were seeded in 96-well

plates for 24 and 48 h and then treated with different

concentrations of CuB and Dox (Fig.

2A–C). After 24 or 48 h, the cell viability was evaluated by

the MTT assay according to the manual. Absorbance at 490 nm was

measured on an automated micro-plate reader. We found that CuB had

moderate cytotoxicity to MCF-7 and MCF-7/Adr cells with an

IC50 of 0.45 and 0.66 µM (Table I). By trypan blue exclusion assay,

we found that CuB rapidly reduced viable MCF-7/Adr (Fig. 2D) in a dose- and time-dependent

manner. We investigated CuB's effect on cell colony formation

activity, and the results showed that CuB significantly inhibited

the clonogenic ability of MCF-7/Adr (Fig. 2E). These results suggested that CuB

inhibited the anchorage-dependent (cell proliferation) and

anchorage-independent (colony formation) growth of MCF-7/Adr

cells.

| Table IIC50s of CuB on breast

cancer cell lines. |

Table I

IC50s of CuB on breast

cancer cell lines.

| Cell lines | MCF-7 | MCF-7/Adr |

|---|

| IC50

(µM) | 0.45±0.03 | 0.66±0.05 |

CuB reverses the resistance of MCF-7/Adr

cells to Dox

MTT assay revealed a significant difference between

the growth-inhibiting effect of Dox on normal MCF-7 cells and on

Dox resistant MCF-7/Adr cells (Fig.

1C). The IC50 of MCF-7 cells was 6.2 µM, vs.

an IC50 of 37.78 µM for the MCF-7/Adr cells.

However, the Dox IC50 of MCF-7/Adr cell was 18.09

µM (0.05 µM CuB treatment) and 12.94 µM (0.1

µM CuB treatment) (Table

II). The resistance index (RI) of MCF-7/Adr parent group was

6.09, the MCF-7/Adr CuB 0.05 µM group 2.91 and the MCF-7/Adr

CuB 0.1 µM group 2.09. The RI calculation formula was used

to find the IC50 of resistant cells/IC50 of

sensitive cells. Following the treatment with CuB (0.05 and 0.1

µM), the IC50 of Dox to the MCF-7/Adr cells was

reduced from 37.78 to 18.09 and 12.94 µM by reversion fold

(RF) 2.09- and 2.92-fold. The RF calculation formula was used to

find the IC50 of Dox on MCF-7/Adr cells/IC50

of Dox (with 0.05 or 0.10 µM CuB) on MCF-7/Adr cells. Thus,

low doses of CuB (0.05 and 0.1 µM) can reverse Dox

resistance.

| Table IIReversing effect of CuB on MCF-7/Adr

cells. |

Table II

Reversing effect of CuB on MCF-7/Adr

cells.

| Groups, CuB

(µM)+Dox (µM) | Inhibition rate

(%) | IC50

(µM) | Resistance

index | Reversion fold |

|---|

| 0+5 | 9.51±0.53 | 37.78 | 6.09 | 1 |

| 0+10 | 14.84±2.94 | | | |

| 0+20 | 23.75±3.61 | | | |

| 0+30 | 52.03±5.36 | | | |

| 0+50 | 71.64±8.34 | | | |

| 0+80 | 83.35±3.89 | | | |

| 0.05+5 | 15.35±2.74 | 18.09 | 2.91 | 2.09 |

| 0.05+10 | 25.62±3.88 | | | |

| 0.05+20 | 36.48±4.92 | | | |

| 0.05+30 | 63.65±5.12 | | | |

| 0.05+50 | 86.46±3.71 | | | |

| 0.05+80 | 89.61±7.15 | | | |

| 0.1+5 | 20.17±3.58 | 12.94 | 2.09 | 2.92 |

| 0.1+10 | 35.72±5.46 | | | |

| 0.1+20 | 48.69±5.77 | | | |

| 0.1+30 | 75.47±4.83 | | | |

| 0.1+50 | 89.43±6.72 | | | |

| 0.1+80 | 98.51±6.02 | | | |

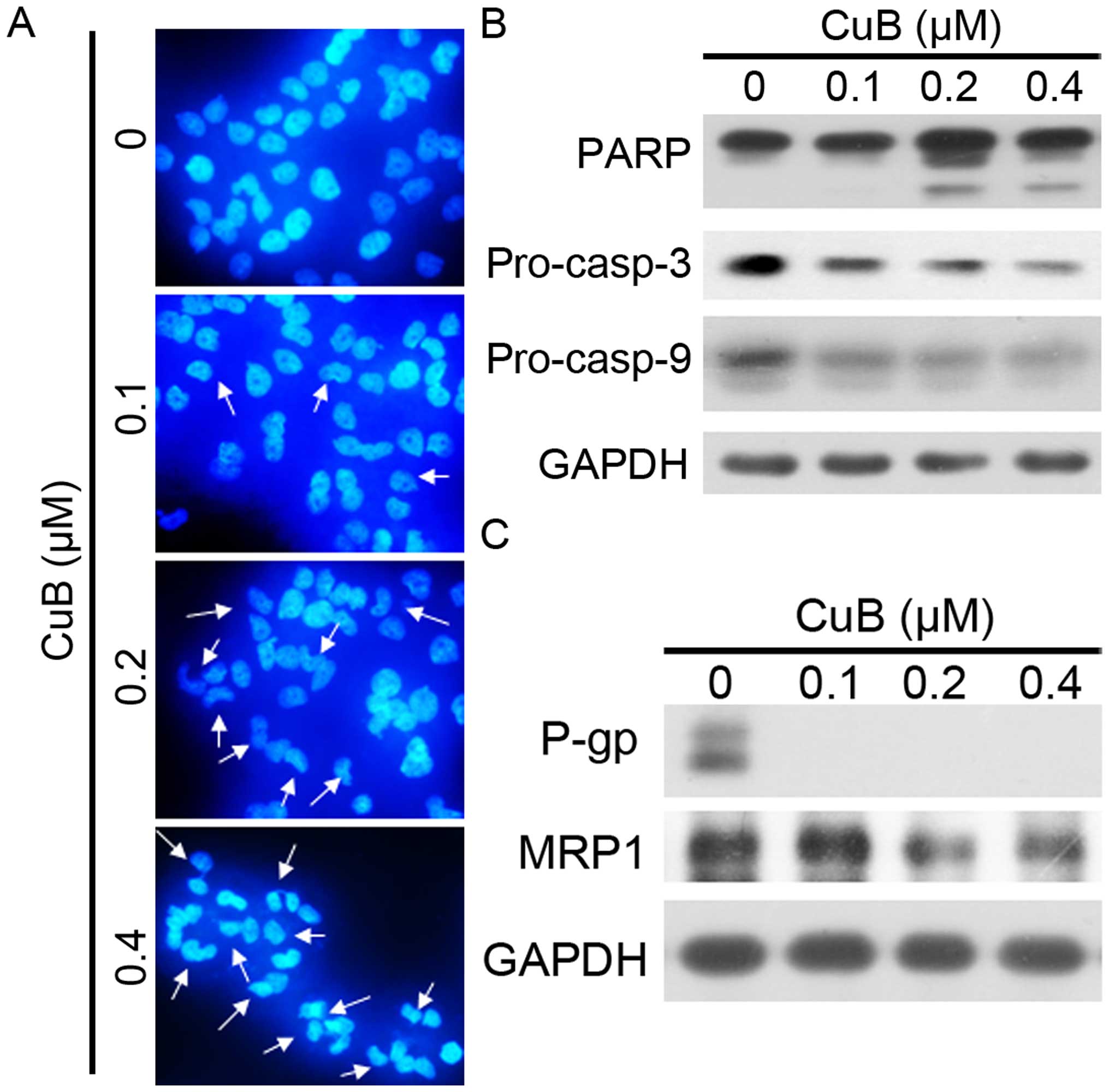

CuB induces apoptosis and influences the

expression of P-gp, MRP1 in MCF-7/Adr cells

We next tested whether or not CuB induces apoptosis

of MCF-7/Adr cells. By an optical light microscope, we found some

dead MCF-7/Adr cells floating in the medium treated with CuB. The

cell death is reminiscent of the phenomena induced by apoptosis. We

investigated the nucleus morphological changes by DAPI staining. As

shown in Fig. 3A, we observed the

nuclear condensation and fragmentation with CuB treatment which are

typical changes in cell apoptosis. Furthermore, a western blot

analysis was used to detect the activation of the caspase-9

(casp-9) initiator caspase, caspase-3 (casp-3) effector caspase and

its substrate, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (Fig. 3B). CuB was demonstrated to induce a

significant dose-dependent decrease in pro-casp-9, pro-casp-3 and

the cleavage of PARP, in MCF-7/Adr cells, indicating that CuB

induced caspase-dependent apoptosis. We detected expression levels

of MDR related factors P-gp and MRP1 by western blot analysis

(Fig. 3C). The results indicated

that P-gp, and MRP1 expression of MCF-7/Adr cells were

downregulated by treatment with increasing concentration of CuB. In

addition, the decreased expression of P-gp and MRP1 in MCF-7/Adr

cells may in part contribute to the reversal of MDR.

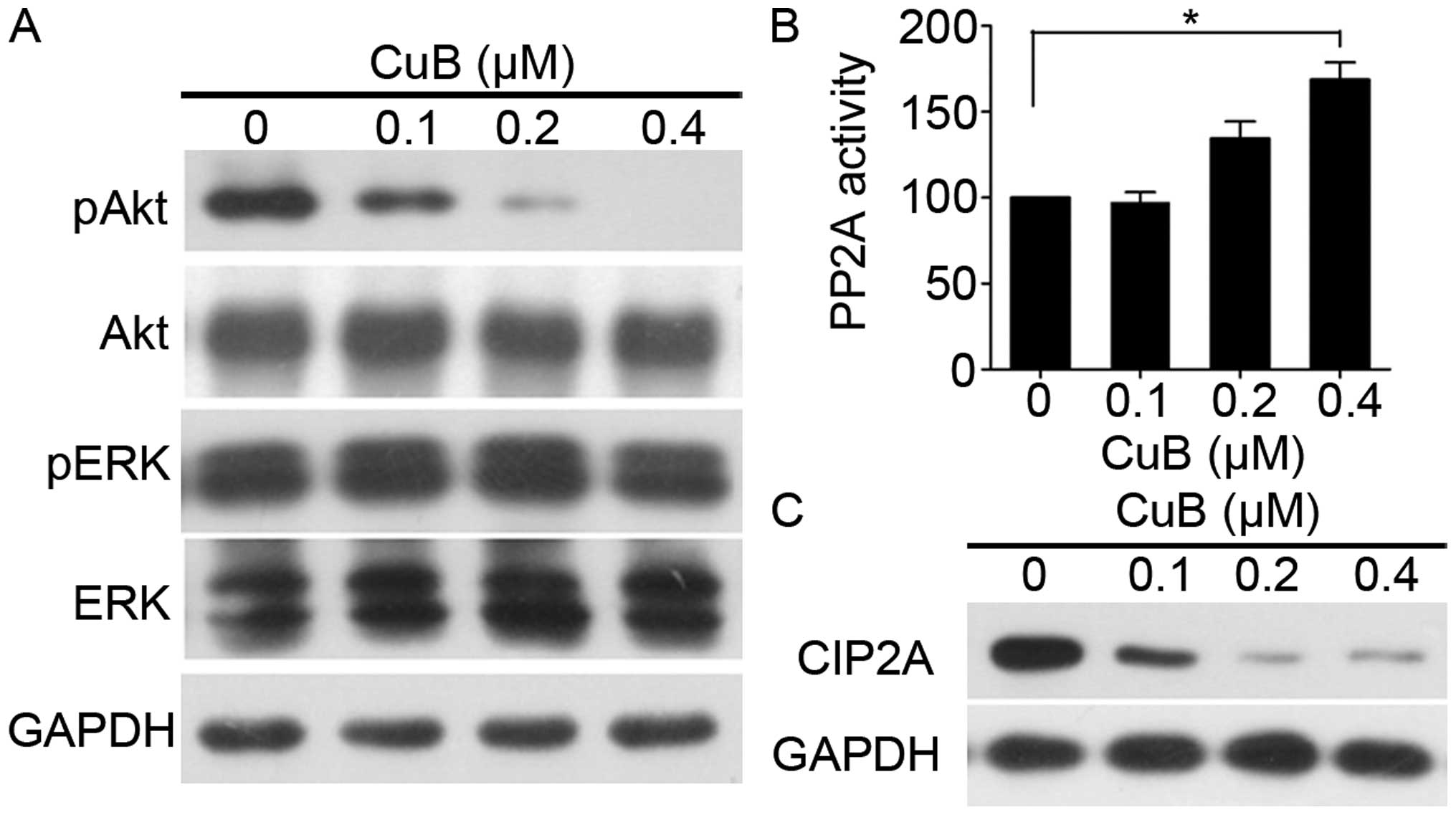

CuB targets CIP2A to reactivate protein

phosphatase 2A

Phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) is a cancer MDR locus

(27). We next investigated the

role of Akt in CuB-induced apoptosis in MCF-7/Adr cells. As shown

in Fig. 4A, CuB decreased Akt

phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner. PP2A, one of the main

serine-threonine phosphatases, plays a critical role in the

regulation of cell cycle progression, survival, and differentiation

by negatively regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway and dephosphorylating

and inactivating MEK1 and ERK family kinases (26). We tested effects of CuB on PP2A

activity, and found that CuB upregulated PP2A activity (Fig. 4B). CIP2A is an oncogenic PP2A

inhibitor protein that is highly expressed in malignant cancers

(28). Furthermore, we tested

effects of CuB on CIP2A expression and found that the protein level

of CIP2A decreased (Fig. 4C),

indicating that CuB targeted CIP2A, at least in part, to reactivate

PP2A. Taken together, these data indicate that the CIP2A/PP2A/Akt

pathway may mediate the sensitizing effect of CuB.

Silencing CIP2A enhances CuB-induced

growth inhibition and apoptosis in MCF-7/Adr

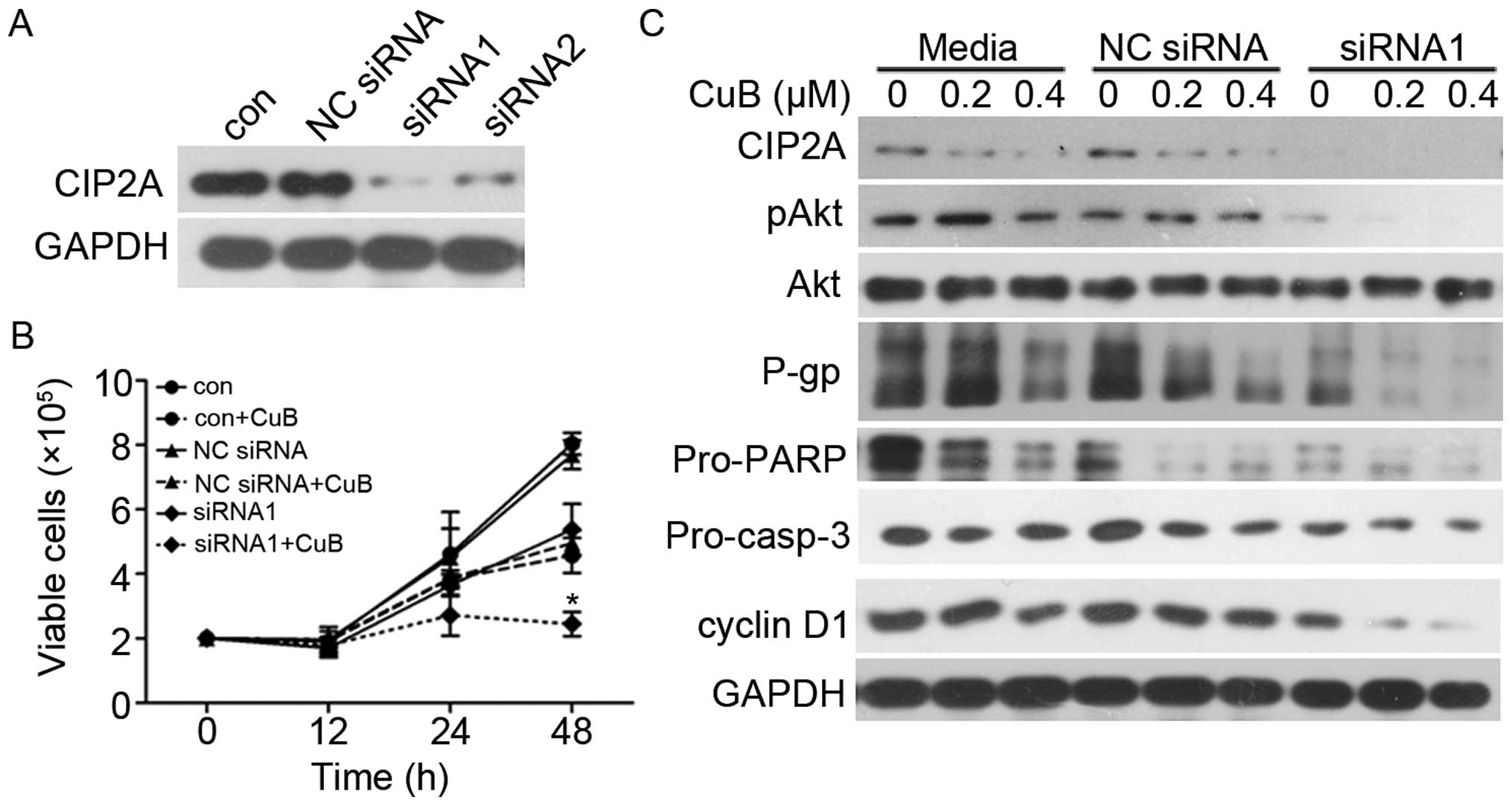

We next examined whether CIP2A knockdown would alter

cellular sensitivity to CuB. Two siRNAs targeting CIP2A were

synthesized and used. As shown in Fig.

5A, knockdown by both siRNA1 and siRNA2 markedly decreased

CIP2A protein in MCF-7/Adr cells. These data showed that CIP2A

siRNA1 and 2 were specific and efficient in reducing CIP2A

expression. To evaluate the role of CIP2A in CuB-induced

proliferation inhibition, MCF-7/Adr cells were transfected with

siRNA1 or siRNA2 targeting CIP2A, followed by CuB treatment. Cell

viability and western blot analysis were used to detect cell growth

and protein expression. CIP2A silencing enhanced CuB-induced growth

inhibition (Fig. 5B) and promoted

CuB-induced apoptotic effect (Fig.

5C). Notably, CIP2A depletion also enhanced CuB-induced MDR

inhibition. These data demonstrate that CIP2A plays a critical role

in CuB-reversed MCF-7/Adr multidrug resistance.

Discussion

Tumorigenesis and chemoresistance is tightly related

to malfunction of the cellular signaling pathways that control cell

proliferation, survival, or death. The malfunction contains

increased expression of ATP-dependent drug efflux pumps and

decreased influx, increased drug metabolism enzymes, impairment of

cell death pathways, enhancement of cell survival pathways,

alternation of drug metabolism, mutations in cell cycle pathways

and superior DNA repair (29). The

aims of the present study were to identify an effective MDR

reversing agent with fewer side-effects and to gain insight

regarding its molecular mechanism. Compounds from natural source

constitute an indispensable candidate drug library for

pharmacotherapy. CuB is a representative therapeutic agent for

anticancer activities. Recently, CuB was reported to enhance the

anticancer effects of cisplatin, gemcitabine, methotrexate,

docetaxel, and gemcitabine in laryngeal squamous, pancreatic, and

breast cancers and osteosarcoma (30). However, the relationship between CuB

and Dox-resistance in MCF-7/Adr cells has yet to be firmly

established. Inhibition of cell proliferation is an efficient

strategy in cancer therapy. In the present study, we first showed

that CuB inhibited MCF-7/Adr cell proliferation (Fig. 2B and C), cell viability (Fig. 2D) and soft-agar colony formation

(Fig. 2E).

We investigated the effect of the combination of CuB

and Dox on the MCF-7/Adr cells and identified that CuB in

combination with Dox had an improved effect compared with Dox or

CuB alone. Following the treatment with CuB (0.05 and 0.1

µM), the IC50 of Dox to the MCF-7/Adr cells was

significantly reduced from 37.78 to 18.09 and 12.94 µM by

2.09- and 2.92-fold (Table II).

The RI of of MCF-7/Adr parent group was 6.09, the MCF-7/Adr CuB

0.05 µM group 2.91 and the MCF-7/Adr CuB 0.1 µM group

2.09, respectively. Furthermore, the present study explored the

mechanisms of CuB in reversing Dox resistance.

Evading apoptosis is one of the hallmarks of drug

resistance, and targeting apoptosis has become a cancer therapeutic

strategy (31). Apoptosis is

accompanied by various morphological changes, including nuclear

condensation, apoptotic bodies, DNA fragmentation and cell surface

changes. Nuclear morphology in MCF-7/Adr cells was analyzed using

DAPI staining; we found changes in nucleus condensation, which are

typical characteristics of apoptosis (Fig. 3A). Therefore, CuB might have the

ability of induction of cell apoptosis. The mechanisms of apoptosis

involve two signaling pathways: the mitochondrial pathway

(intrinsic apoptotic pathway) and the cell death receptor pathway

(extrinsic apoptotic pathway) (32). The extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic

pathways that ultimately lead to activation of effector caspases

(casp-3, -2 and -7) have been characterized (33,34).

The decrease of pro-casp-9, pro-casp-3, as well as the proteolysis

of PARP (Fig. 3B), indicate that

casp-3 is activated. Thus, CuB may trigger apoptosis by activating

the intrinsic apoptosis pathway which results in activation of

effector casp-9. Drug resistance is largely mediated through

overexpression of MDR, MRP, drug resistance protein, and proteasome

subunits, increases in antioxidant defenses, and TOP2 activity;

these results have been widely verified (35–37).

The present study identified that the treatment of CuB was able to

reverse the MDR of the MCF-7/Adr cells via the downregulation of

P-gp and MRP1 (Fig. 3C).

PP2A is a serine/threonine phosphatase that has a

critical role in regulating various cellular processes, including

signaling transduction, protein synthesis, cell cycle

determination, metabolism, apoptosis and stress response (38). Because loss of PP2A function has

been identified in various malignant diseases such as cancer of the

colon, liver, lung and breast, it has been suggested that PP2A

functions as a tumor suppressor and enhancing PP2A activity could

be an effective approach for anticancer treatment (39). In this study, we showed that by

inhibiting CIP2A, activity of PP2A was significantly enhanced and

expression of pAkt was downregulated in MCF-7/Adr cells (Fig. 4). Several cellular inhibitors of

PP2A have been identified, including SET (26) and CIP2A. CIP2A, originally named

KIAA1524 or P90, has been cloned from patients with HCC (8). CIP2A is associated with clinical

aggressiveness in human breast cancer and promotes the malignant

growth and metastasis of breast cancer cells. Induction of CIP2A is

often associated with chemoresistance in cancer cells, and the

inhibition of CIP2A in combination with chemotherapy may enhance

the efficacy of cancer treatment (40). We knocked down CIP2A expression in

MCF-7/Adr cells and found that CIP2A depletion significantly

promoted CuB induced apoptosis and reversed MDR (Fig. 5). Our data validated the mechanism

by which CuB-reversed MDR and induced cancer cell apoptosis in

MCF-7/Adr cells, that is, reversed MDR and induction of cancer cell

apoptosis by inhibiting CIP2A to reactivate PP2A and enhance

PP2A-dependent pAkt downregulation.

In conclusion, our results suggest that further

studies investigating the detailed molecular modification of the

PP2A/CIP2A signaling pathway by CuB and exploring its possible

application in other malignant diseases are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the

National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant no. 81400157);

the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Provincial Department of

Education (grant no. Q20152106); the Faculty Development Grants

from Hubei University of Medicine (grant nos. 2014QDJZR08,

2015QDJZR16); the Foundation for Innovative Research Team of Hubei

University of Medicine (grant no. 2014CXX05); the Key Discipline

Project of Hubei University of Medicine and the National Training

Program of Innovation and Entrepreneurship for Undergraduates

(grant no. 201610929001).

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 65:5–29. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J,

Lortet-Tieulent J and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:87–108. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhu XF, Li W, Ma JY, Shao N, Zhang YJ, Liu

RM, Wu WB, Lin Y and Wang SM: Knockdown of heme oxygenase-1

promotes apoptosis and autophagy and enhances the cytotoxicity of

doxorubicin in breast cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 10:2974–2980.

2015.

|

|

4

|

Zheng Y, Lv X, Wang X, Wang B, Shao X,

Huang Y, Shi L, Chen Z, Huang J and Huang P: MiR-181b promotes

chemoresistance in breast cancer by regulating Bim expression.

Oncol Rep. 35:683–690. 2016.

|

|

5

|

Faneyte IF, Kristel PM, Maliepaard M,

Scheffer GL, Scheper RJ, Schellens JH and van de Vijver MJ:

Expression of the breast cancer resistance protein in breast

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 8:1068–1074. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jeon YJ, Kim JH, Shin JI, Jeong M, Cho J

and Lee K: Salubrinal-mediated upregulation of eIF2α

phosphorylation increases doxorubicin sensitivity in MCF-7/ADR

cells. Mol Cells. 39:129–135. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Perrotti D and Neviani P: Protein

phosphatase 2A: A target for anticancer therapy. Lancet Oncol.

14:e229–e238. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Junttila MR, Puustinen P, Niemelä M, Ahola

R, Arnold H, Böttzauw T, Alaaho R, Nielsen C, Ivaska J, Taya Y, et

al: CIP2A inhibits PP2A in human malignancies. Cell. 130:51–62.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Seshacharyulu P, Pandey P, Datta K and

Batra SK: Phosphatase: PP2A structural importance, regulation and

its aberrant expression in cancer. Cancer Lett. 335:9–18. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Schönthal AH: Role of serine/threonine

protein phosphatase 2A in cancer. Cancer Lett. 170:1–13. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lv P, Wang Y, Ma J, Wang Z, Li JL, Hong

CS, Zhuang Z and Zeng YX: Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A with

a small molecule LB100 radiosensitizes nasopharyngeal carcinoma

xenografts by inducing mitotic catastrophe and blocking DNA damage

repair. Oncotarget. 5:7512–7524. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li W, Ge Z, Liu C, Liu Z, Björkholm M, Jia

J and Xu D: CIP2A is overexpressed in gastric cancer and its

depletion leads to impaired clonogenicity, senescence, or

differentiation of tumor cells. Clin Cancer Res. 14:3722–3728.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu Z, Ma L, Wen ZS, Hu Z, Wu FQ, Li W,

Liu J and Zhou GB: Cancerous inhibitor of PP2A is targeted by

natural compound celastrol for degradation in non-small-cell lung

cancer. Carcinogenesis. 35:905–914. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ren J, Li W, Yan L, Jiao W, Tian S, Li D,

Tang Y, Gu G, Liu H and Xu Z: Expression of CIP2A in renal cell

carcinomas correlates with tumour invasion, metastasis and

patients' survival. Br J Cancer. 105:1905–1911. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu CY, Shiau CW, Kuo HY, Huang HP, Chen

MH, Tzeng CH and Chen KF: Cancerous inhibitor of protein

phosphatase 2A determines bortezomib-induced apoptosis in leukemia

cells. Haematologica. 98:729–738. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Choi YA, Park JS, Park MY, Oh KS, Lee MS,

Lim JS, Kim KI, Kim KY, Kwon J, Yoon Y, et al: Increase in CIP2A

expression is associated with doxorubicin resistance. FEBS Lett.

585:755–760. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu J, Wang M, Zhang X, Wang Q, Qi M, Hu

J, Zhou Z, Zhang C, Zhang W, Zhao W, et al: CIP2A is associated

with multidrug resistance in cervical adenocarcinoma by a

P-glycoprotein pathway. Tumour Biol. 7:2673–2682. 2015.

|

|

18

|

Lai GM, Ozols RF, Young RC and Hamilton

TC: Effect of glutathione on DNA repair in cisplatin-resistant

human ovarian cancer cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 81:535–539.

1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

El-Senduny FF, Badria FA, El-Waseef AM,

Chauhan SC and Halaweish F: Approach for chemosensitization of

cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer by cucurbitacin B. Tumour Biol.

37:685–698. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chan KT, Meng FY, Li Q, Ho CY, Lam TS, To

Y, Lee WH, Li M, Chu KH and Toh M: Cucurbitacin B induces apoptosis

and S phase cell cycle arrest in BEL-7402 human hepatocellular

carcinoma cells and is effective via oral administration. Cancer

Lett. 294:118–124. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chan KT, Li K, Liu SL, Chu KH, Toh M and

Xie WD: Cucurbitacin B inhibits STAT3 and the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway

in leukemia cell line K562. Cancer Lett. 289:46–52. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Liu Y, Cao W, Zhang B, Liu YQ, Wang ZY, Wu

YP, Yu XJ, Zhang XD, Ming PH, Zhou GB, et al: The natural compound

magnolol inhibits invasion and exhibits potential in human breast

cancer therapy. Sci Rep. 3:30982013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cao W, Liu Y, Zhang R, Zhang B, Wang T,

Zhu X, Mei L, Chen H, Zhang H, Ming P, et al: Homoharringtonine

induces apoptosis and inhibits STAT3 via IL-6/JAK1/STAT3 signal

pathway in Gefitinib-resistant lung cancer cells. Sci Rep.

5:84772015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chou CC, Yang JS, Lu HF, Ip SW, Lo C, Wu

CC, Lin JP, Tang NY, Chung JG, Chou MJ, et al: Quercetin-mediated

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis involving activation of a caspase

cascade through the mitochondrial pathway in human breast cancer

MCF-7 cells. Arch Pharm Res. 33:1181–1191. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu Y, Dong Y, Zhang B and Cheng YX: Small

compound 6-O-angeloylplenolin induces caspase-dependent apoptosis

in human multiple myeloma cells. Oncol Lett. 6:556–558.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu H, Gu Y, Wang H, Yin J, Zheng G, Zhang

Z, Lu M, Wang C and He Z: Overexpression of PP2A inhibitor SET

oncoprotein is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis

in human non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 6:14913–14925.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Radisavljevic Z: AKT as locus of cancer

multidrug resistance and fragility. J Cell Physiol. 228:671–674.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Rincón R, Cristóbal I, Zazo S, Arpí O,

Menéndez S, Manso R, Lluch A, Eroles P, Rovira A, Albanell J, et

al: PP2A inhibition determines poor outcome and doxorubicin

resistance in early breast cancer and its activation shows

promising therapeutic effects. Oncotarget. 6:4299–4314. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB

and Johnston PG: Cancer drug resistance: An evolving paradigm. Nat

Rev Cancer. 13:714–726. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Guo J, Zhao W, Hao W, Ren G, Lu J and Chen

X: Cucurbitacin B induces DNA damage, G2/M phase arrest, and

apoptosis mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) in leukemia

K562 cells. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 14:1146–1153. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Marsden VS, O'Connor L, O'Reilly LA, Silke

J, Metcalf D, Ekert PG, Huang DC, Cecconi F, Kuida K, Tomaselli KJ,

et al: Apoptosis initiated by Bcl-2-regulated caspase activation

independently of the cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9 apoptosome.

Nature. 419:634–637. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Nicholson DW: Caspase structure,

proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death.

Cell Death Differ. 6:1028–1042. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA and Lowe SW:

Apoptosis: A link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell.

108:153–164. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Alcantara LM, Kim J, Moraes CB, Franco CH,

Franzoi KD, Lee S, Freitas-Junior LH and Ayong LS:

Chemosensitization potential of P-glycoprotein inhibitors in

malaria parasites. Exp Parasitol. 134:235–243. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Luo L, Sun YJ, Yang L, Huang S and Wu YJ:

Avermectin induces P-glycoprotein expression in S2 cells via the

calcium/calmodulin/NF-κB pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 203:430–439.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ying L, Zu-An Z, Qing-Hua L, Qing-Yan K,

Lei L, Tao C and Yong-Ping W: RAD001 can reverse drug resistance of

SGC7901/DDP cells. Tumour Biol. 35:9171–9177. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cristóbal I, Rincón R, Manso R, Caramés C,

Zazo S, Madoz-Gúrpide J, Rojo F and García-Foncillas J:

Deregulation of the PP2A inhibitor SET shows promising therapeutic

implications and determines poor clinical outcome in patients with

metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 21:347–356. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Yu HC, Hung MH, Chen YL, Chu PY, Wang CY,

Chao TT, Liu CY, Shiau CW and Chen KF: Erlotinib derivative

inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting CIP2A to reactivate

protein phosphatase 2A. Cell Death Dis. 5:e13592014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Côme C, Laine A, Chanrion M, Edgren H,

Mattila E, Liu X, Jonkers J, Ivaska J, Isola J, Darbon JM, et al:

CIP2A is associated with human breast cancer aggressivity. Clin

Cancer Res. 15:5092–5100. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|