Introduction

Lung cancer has one of the highest morbidity and

mortality rates worldwide. The majority of lung cancers are

diagnosed at late stages, with locally advanced disease and distant

metastases, and its long-term survival remains desperately poor.

Radiotherapy is one of the most important therapies in these

patients while recurrence and metastasis, signs of malignancy and

the main cause of death in cancer patients (1), and the risk of tumor radio-resistance

limit the effect of radiotherapy. Many studies have also found that

radiotherapy plays a role in stimulating tumor cell growth and

promoting invasiveness of tumor cells in addition to a number of

common adverse reactions. Thus, looking for the effective

combination therapy to enhance the antitumor effect is still

urgent.

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs), obtained by

the methods of enzymatic hydrolysis or chemical degradation from

unfractionated heparin (UFH), relative molecular weight 3–9 kDa,

was approved by the FDA in 1998 for anticoagulant therapy and has

been administrated as effective anticoagulants in the prevention

and treatment of thrombosis safely for many years (2), along with having potential anticancer

effects and improving survival in cancer patients (3,4).

Furthermore, recent studies have showed that LMWHs can directly

induce the inhibition of the invasion and metastasis of the cancer

cells, change the cell cycle, increase the sensitivity of

chemotherapy and reduce the extent of radiation-induced liver

injury (5–8). Whether it has synergistic antitumor

effects to radiotherapy has rarely been reported. On the basis of

present studies, we used two doses of nadroparin, a kind of LMWH,

combined with X-ray irradiation to treat A549 cells in order to

assess the relevant interactions between nadroparin and

radiotherapy in this study.

Materials and methods

Main instruments and reagents

A549 cell line used in this study was kindly

supplied by the Shanghai Institute of Life Science, Chinese Academy

of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium

(Biowest, Nuaillé, France) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS). Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere

containing 5% CO2. Nadroparin (Fraxiparina®;

GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK) was obtained as standard drug

formulations. The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories,

Kumamoto, Japan) was used to detect cell proliferation and

activity. Levels of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) in the

culture supernatants was measured using a standard Quantikine

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit from R&D Systems,

Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC) detection kit was purchased from Becton-Dickinson (San Jose,

CA, USA) to detect cell apoptosis. Matrigel and Transwell chambers

were purchased from Becton-Dickinson as well. Rabbit monoclonal

antibodies against survivin, goat anti-rabbit horseradish

peroxidase labelled secondary antibody, anti-GAPDH mouse monoclonal

antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

(Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The linear accelerator was Precise 5839

(Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden).

Experimental method and grouping

This study contained six groups with different kinds

of treatments: control group; irradiation group (X-ray, treated

with 10 Gy X-ray irradiation); LMWH50 group

(L50, treated with 50 IU/ml of nadroparin);

LMWH100 group (L100, treated with 100 IU/ml

of nadroparin); LMWH50+X-ray irradiation group and

LMWH100+X-ray irradiation group (X+L50,

X+L100, treated with two doses of nadroparin and 10 Gy

X-ray irradiation). Cells were seeded and incubated for 24 h, then

changed to 10% FBS-1640 with or without nadroparin overnight.

Twenty-four hours later, X-ray irradiation was administered

according to the experimental design. A variety of detection was

performed in the next 24 and 48 h after radiation.

Cell viability assay

Cells (5×103 cells/well) were incubated

in the 96-well plates and treatments were conducted as mentioned

above. The CCK-8 solution (10 µl/well) was added at the

indicated time, then incubated for further 1 h at 37°C. The

absorbance of cells in each well was measured at 450 nm. The cell

viability was expressed as percentage of the absorbance present in

the treated group compared to the control group:

(ODtreated/ODcontrol) × 100%.

Assessment of cell apoptosis

In brief, 2×05 cells/well were applied to

six-well plates and treated exactly as described above. The cells

were harvested and centrifuged at 24 and 48 h after radiation and

then washed twice with PBS. The cells were resuspended in 500

µl of binding buffer containing 5 µl FITC conjugated

Annexin V and 5 µl propidium iodide (PI), and incubated in

the dark at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were then analysed

in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson) to differentiate

apoptotic cells (Annexin V-positive and PI-negative, lower right

quadrant) from necrotic cells (Annexin V/PI-positive, upper right

quadrant). Fifteen thousand events were recorded for each treatment

group.

Measurement of TGF-β1 release

The cell culture supernatants were collected at 24

and 48 h after radiation. The culture supernatants were separated

by centrifugation and stored at −80°C. The concentration of TGF-β1

was measured simultaneously using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems,

Inc.).

Determination of migration and

invasion

About 2×105 cells/well were seeded to

six-well plates and treated exactly as described above. The cells

were harvested and centrifuged at 24 h after radiation and

maintained in serum-free RPMI-1640 for 12 h. Cell invasion and

migration were determined with or without Matrigel-coated Transwell

chambers. Cells (1×104) were removed for migration and

2×104 cells for invasion of these treated cells were

placed into the upper compartment with 100 µl serum-free

RPMI-1640, and the lower compartment was filled with RPMI-1640

containing 15% FBS. The chamber was then cultivated in 5%

CO2 at 37°C for 24 h to detect the cell migration and

invasion. The Matrigel and cells in the upper chamber were removed,

and the attached cells in the lower section were stained with 0.1%

crystal violet. These cells were counted in five high-power

microscope fields of vision and photo graphed.

Protein extraction and western

blotting

Cells (2×105) were seeded in six-well

plates and treated as described above. At the end of the treatment

period (24 and 48 h after radiation), cells were washed three times

in ice-cold PBS and lysed for at least 30 min on ice in the cold

lysis buffer with 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF).

Protein concentrations were measured using the Coomassie Blue Fast

staining solution (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Proteins (50

µg) in each group was separated on 10–12% SDS-PAGE and

transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA,

USA) at 80 V for 90 min. Membranes were blocked by TBS/T containing

5% skim milk for 3 h, and incubated with the CD147, matrix

metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and survivin antibody (1:500–1:1,000

dilution) overnight at 4°C, while the GAPDH and β-actin antibody

(1:10,000 dilution) was used as an endogenous reference for

quantification. Then the membranes were incubated with the

secondary antibodies (1:4,000 dilution) at room temperature for 1 h

after three washes in TBS/T. After several washes with TBS/T, the

blots were detected using Immobilon™ Western Chemiluminescent HRP

substrate (Millipore Corp.) and quantified using Tanon-4500 Gel

Imaging System with GIS ID Analysis Software v4.1.5 (Tanon Science

& Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS

software version 20.0. Data were expressed as means ± standard

error (SE). Student's t-test was used to test the differences

between groups. Differences resulting in p<0.05 were considered

to be statistically significant. All data are reported from three

independent experiments.

Results

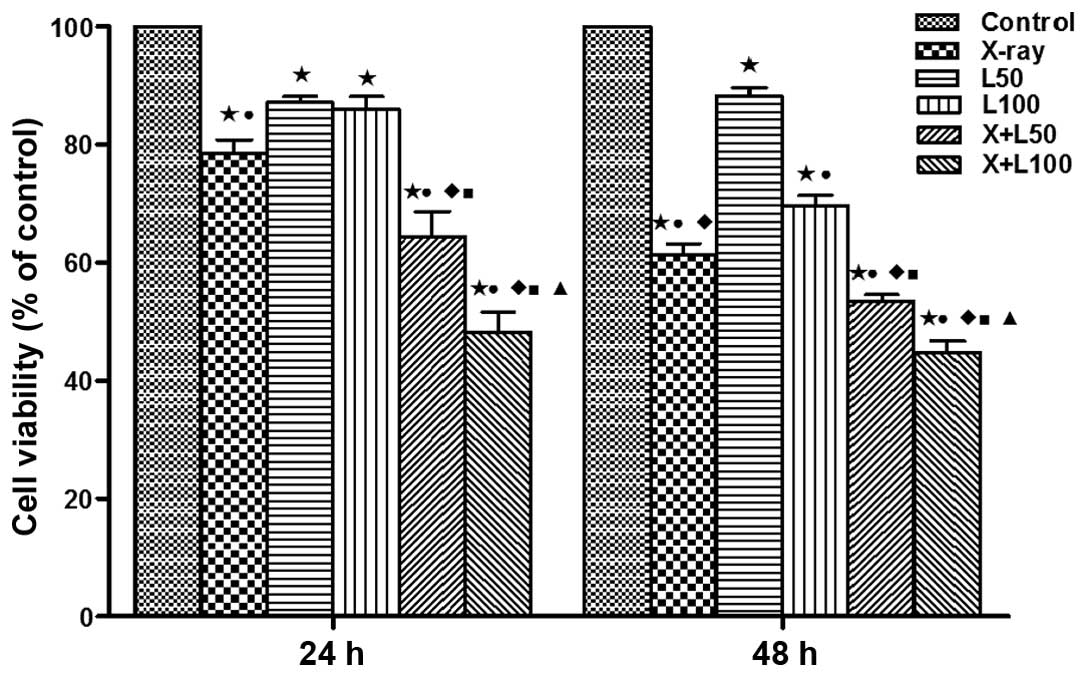

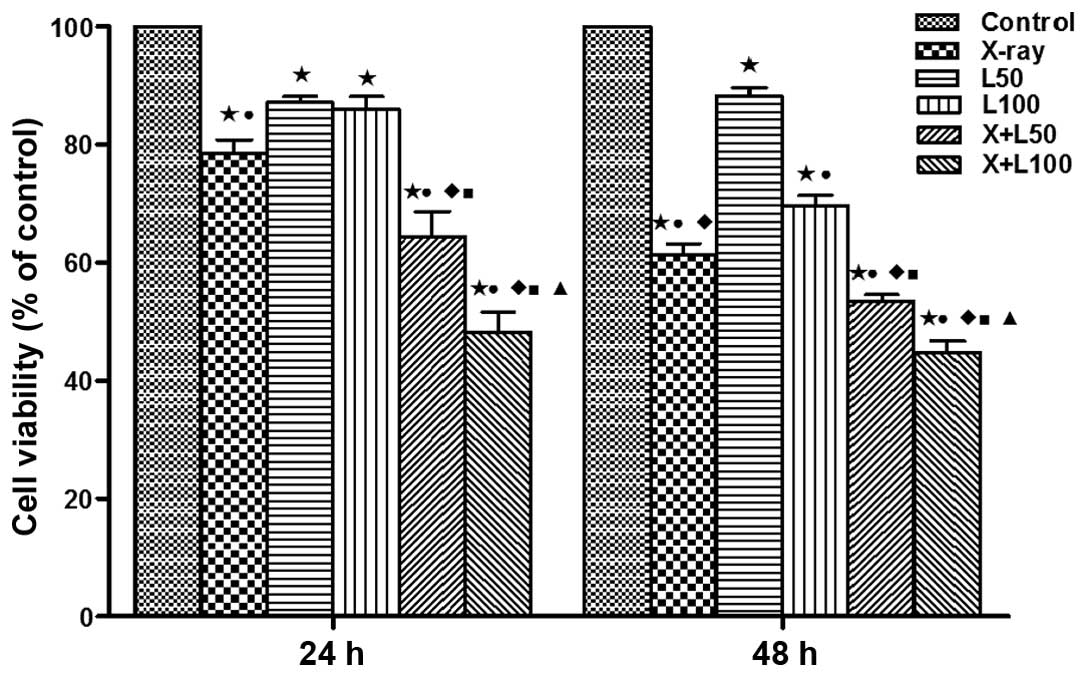

Effects on cell viability

This study examined the cell viability of A549 cells

treated with two doses of nadroparin and X-ray radiation at

different time-points (24 and 48 h) using the CCK-8 assay. As shown

in Fig. 1, the cell viability was

inhibited to different extent compared to the control group after

treatments. With the prolongation of treat ment time, no

significant change was observed in the inhibition of cell viability

treated with low dose of nadroparin alone (L50 group),

while the cell viability was inhibited in a dose- and

time-dependent manner after the other treatments (irradiation

alone, high dose of nadroparin alone (L100 group) and

different dose of nadroparin combined with X-ray irradiation).

Furthermore, the cell viability was significantly inhibited in the

high dose of nadroparin combined with X-ray irradiation group

compared to the other groups (p<0.05).

| Figure 1Effect of nadroparin and X-ray

irradiation on A549 cell viability. Cell Counting Kit-8 was used to

detect the cell viability of A549 cells after different treatments

at different time-points, respectively. Significant differences

were observed in the treated groups compared to the control group

(*p<0.05, t=9.492, 12.889, 6.753, 8.153 and 14.704 at 24 h,

t=20.413, 7.990, 17.770, 44.692 and 29.615 at 48 h). A difference

from X-ray irradiation group (■p<0.05, t=2.883 and

7.256 at 24 h, t=3.639 and 6.214 at 48 h); a difference from

L50 (●p<0.05, t=3.483, 5.083 and 10.643 at

24 h, t=11.152, 19.150 and 18.200 at 48 h, p<0.05); a difference

from L100 (♦p<0.05, t=4486 and 9.473 at 24

h, t=3.264, 8.095 and 9.826 at 48 h); a difference from

X+L50 (▲p<0.05, t=2.886 at 24 h, t=4050 at

48 h). |

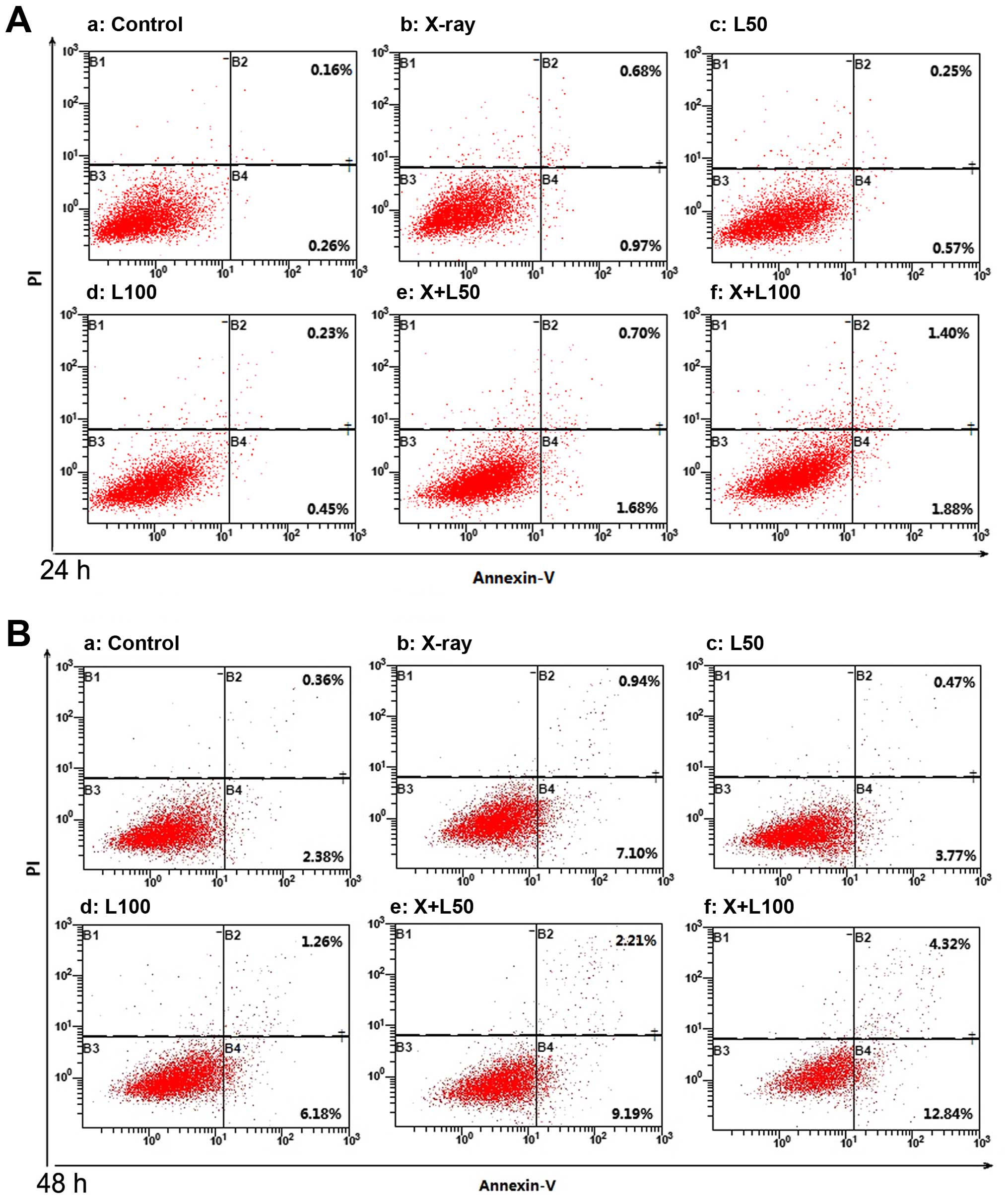

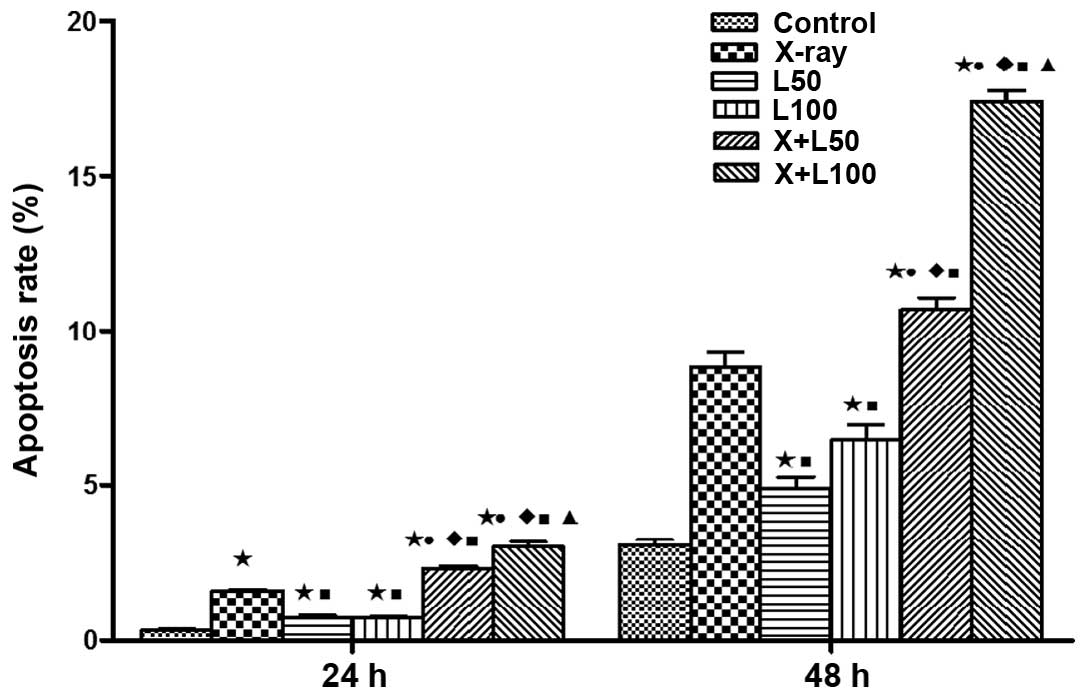

Cell apoptosis

LWMHs induced apoptosis of tumor cells in

vitro and in vivo (9,10). Our

study examined whether nadroparin had synergetic contribution to

tumor cell apoptosis when combined with X-ray irradiation. As shown

in Figs. 2 and 3, each treatment remarkably induced A549

cell apoptosis dose- and time-dependently compared to the control

group (p<0.05). The promotion of apoptosis induced by X-ray

irradiation alone was more significant than by different dose of

nadroparin alone (p<0.05). Furthermore, the apoptosis rate

reached 17.41±0.63% in X+L100 group 48 h after

treatment, and was the highest among the experimental groups

(p<0.05), which revealed that the higher the dose of nadroparin

combined with X-ray irradiation, the more effective the result

was.

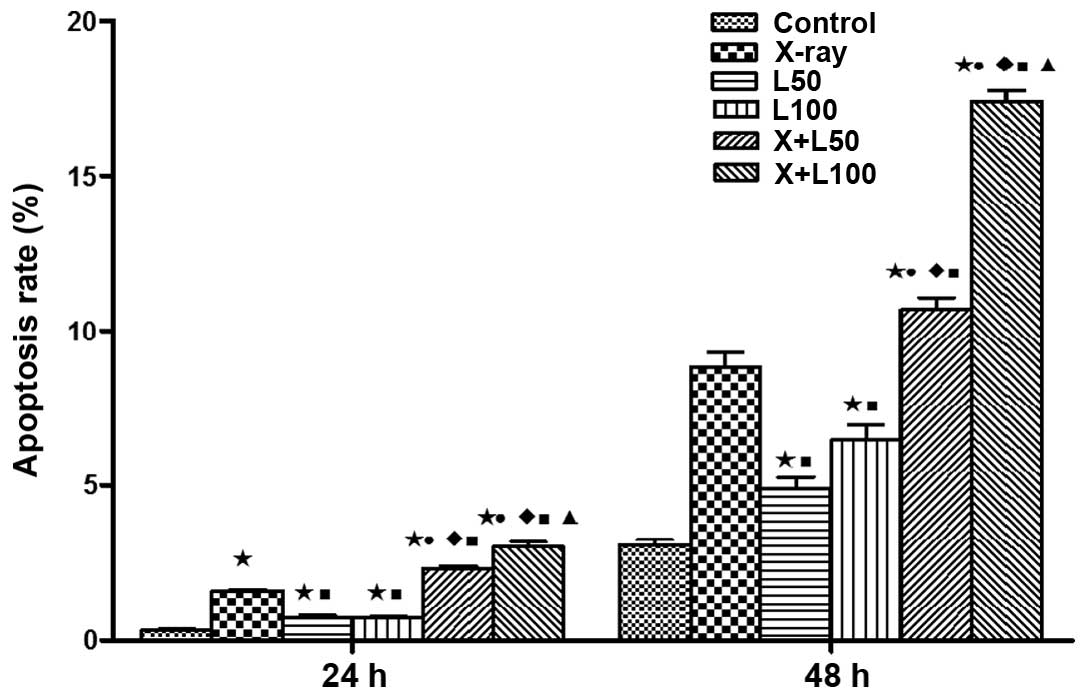

| Figure 3Apoptotic fraction of A549 cells in

different experimental groups. Significant differences of A549 cell

apoptosis in the treated groups were observed compared to the

control group (*p<0.05, t=17.307, 3.635, 4.964, 18.636 and

15.353 at 24 h, t=11.251, 4.517, 6.443, 18.380 and 35.032 at 48 h).

The promotion of apoptosis induced by X-ray irradiation alone was

more significant than by different dose of nadroparin alone but

less effect was observed when combined (■p<0.05,

t=9683, 15.043, 7.899 and 8.523 at 24 h, t=6.606, 3.432, 3.096 and

14.371 at 48 h). A difference from L50

(●p<0.05, t=13.338 and 12.525 at 24 h, t=11.279 and

24.579 at 48 h, p<0.05); a difference from L100

(♦p<0.05, t=16.415 and 13.501 at 24 h, t=6.842 and

17.866 at 48 h); a difference from X+L50

(▲p<0.05, t=3.846 at 24 h, t=13.020 at 48 h). |

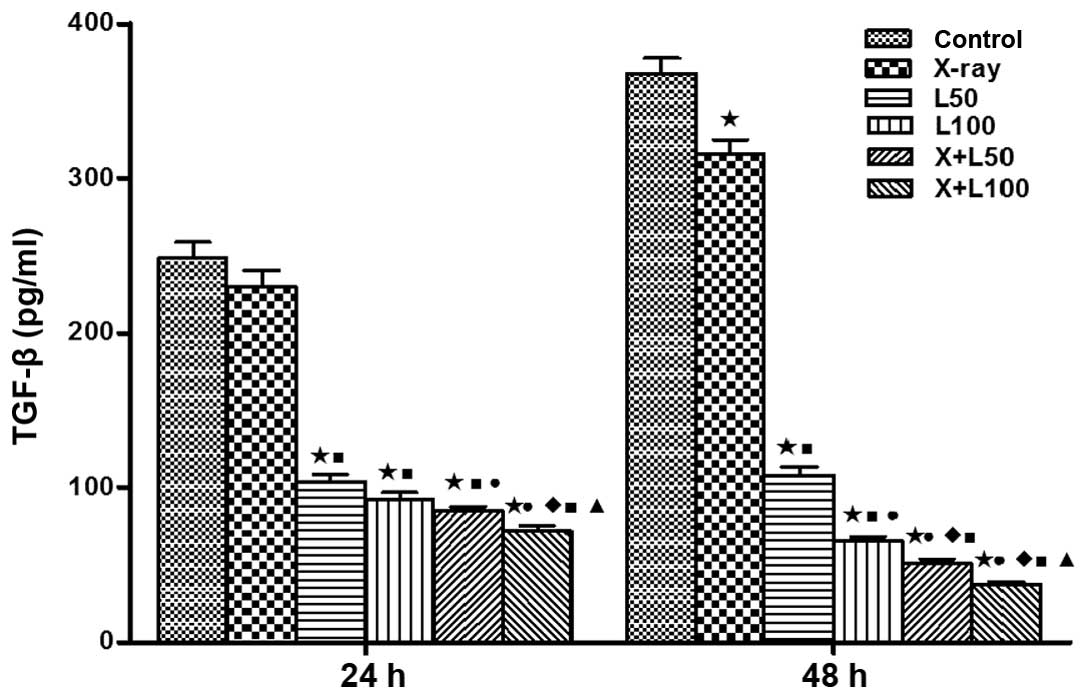

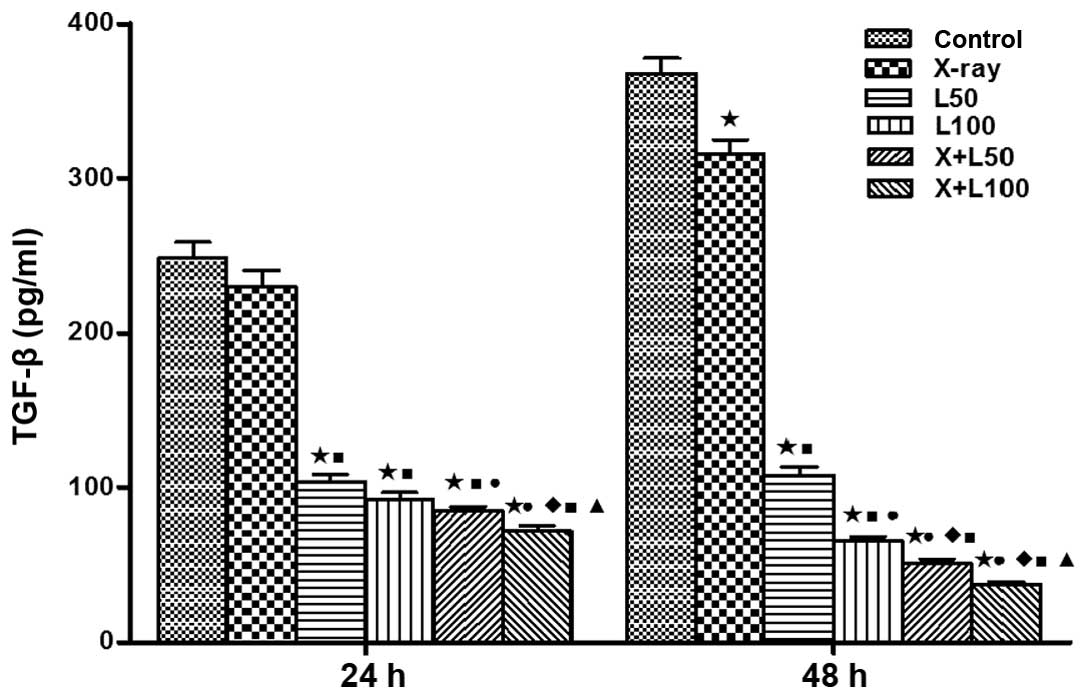

Release of TGF-β1

The concentrations of TGF-β1 in the cell

supernatants at the time-points (24 and 48 h) after irradiation

were compared among each group in Fig.

4. We found that the TGF-β1 levels were increased with the

prolonging of time in the control group, X-ray irradiation group

and the L50 group, and the increase of the control group

was the most obvious. On the contrary, with the prolonging of time,

the TGF-β1 levels were significantly decreased in the

L100 group and two combined treatment groups. The

concentrations of TGF-β1 in X+L100 group were 71.88±5.87

and 37.35±2.92 pg/ml, respectively, at 24 and 48 h after treatment,

which was the lowest among the experimental groups (p<0.05).

| Figure 4Concentration of transforming growth

factor-β1 (TGF-β1) in cell culture supernatants. Enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay kit was used to measure TGF-β1 levels in cell

culture supernatants. The levels were of statistically significant

differences among the groups. A difference from the control group

(*p<0.05, t=13.294, 14.419, 16.238 and 17.173 at 24 h, t=3.817,

22.470, 28.463, 29.598 and 31.885 at 48 h); a difference from X-ray

irradiation group (■p<0.05, t=11.173, 12.253, 13.802

and 14.759 at 24 h, t=20.145, 27.037, 28.312 and 31.065 at 48 h); a

difference from L50 (●p<0.05, t=3.384 and

5.356 at 24 h, t=6.987,9.147 and 12.513 at 48 h); a difference from

L100 (p<0.05, t=3.392 at 24 h, t=3.370 and 8.318 at

48 h); a difference from X+L50 (p<0.05, t=3.014 at 24

h, t=3.703 at 48 h). |

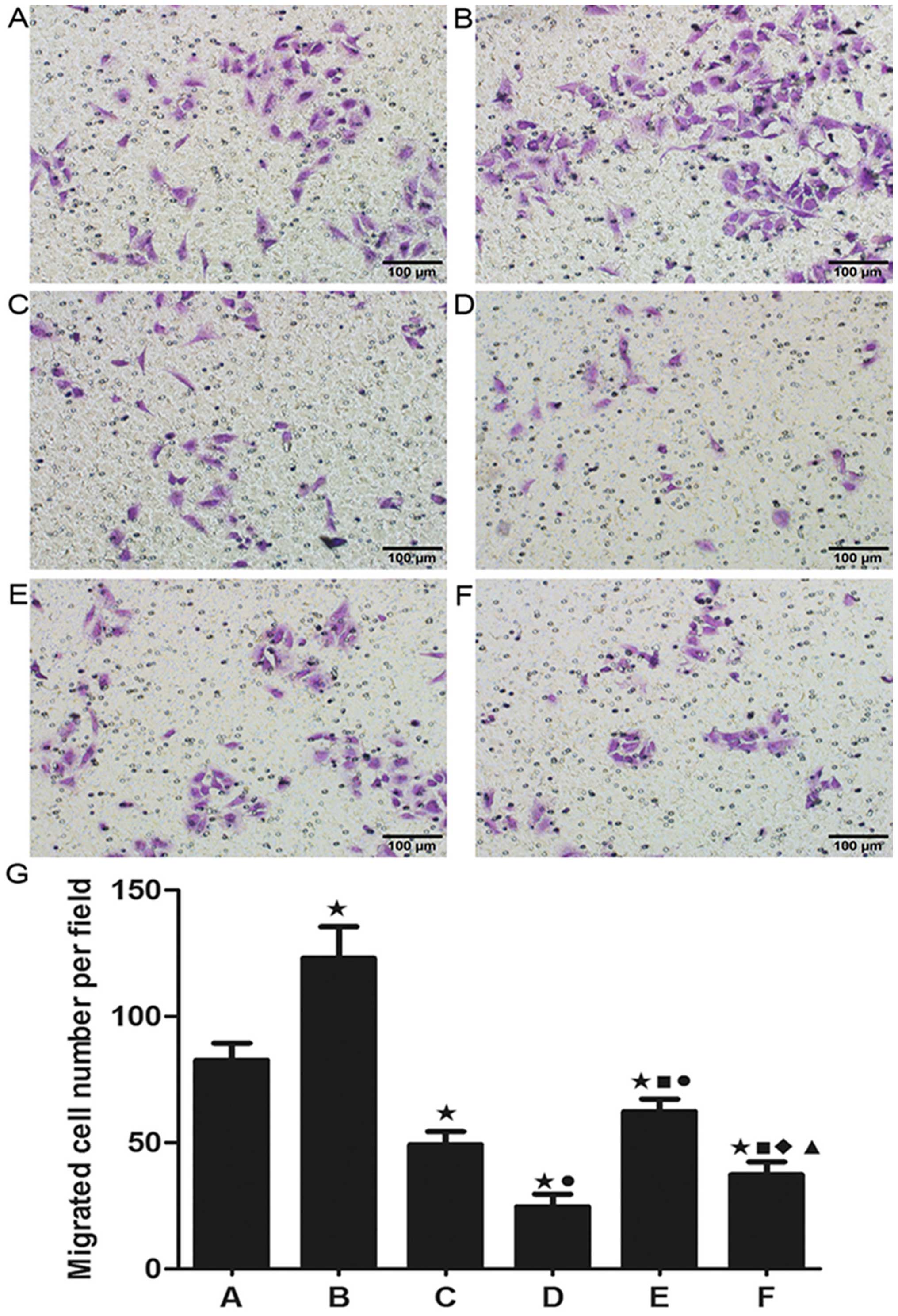

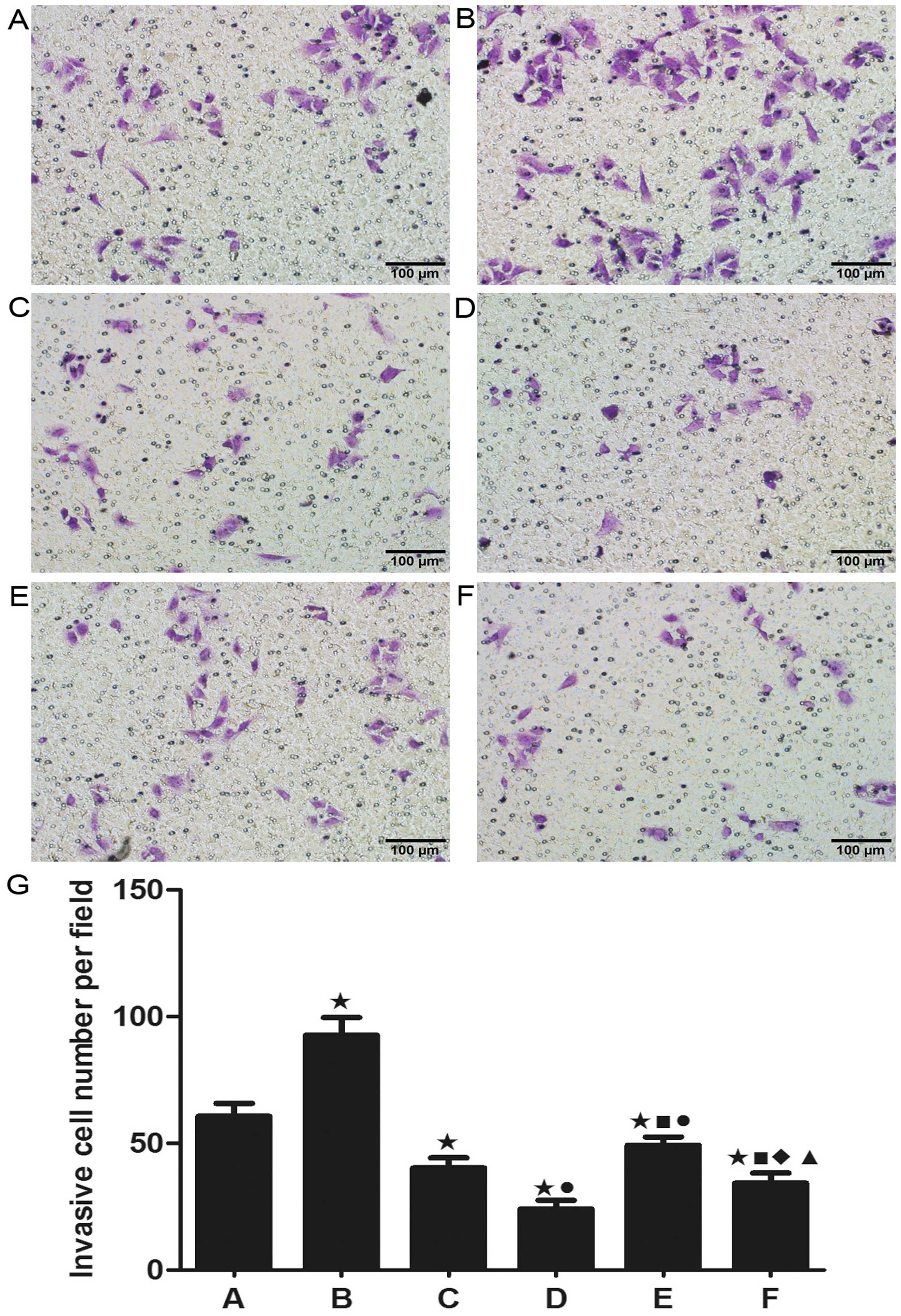

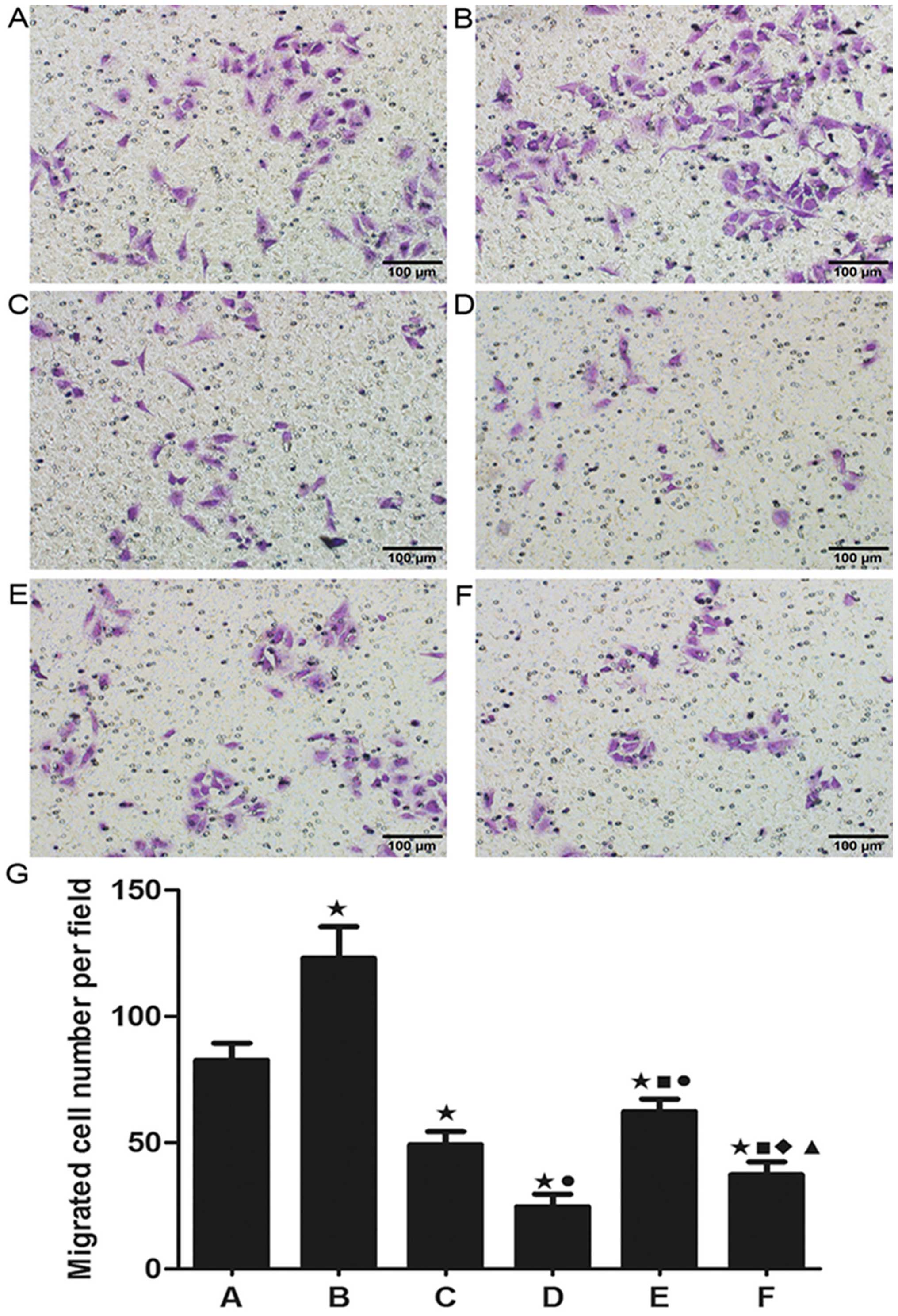

Cell migration and invasion

Cell migration and invasion are critical for the

spreading of cancer and the formation of metastasis in vivo.

As shown in Fig. 5, X-ray

irradiation alone resulted in a significant increase in A549 cell

migration while less migration was observed in the nadroparin alone

groups in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, nadroparin

inhibited the increase in A549 cell migration induced by X-ray

irradiation in the combined treatment groups. Additionally, as

shown in Fig. 6, similar results

were seen in A549 cell invasion. Our result showed that X-ray

irradiation promoted the ability of invasion and migration in A549

cells while nadroparin inhibited this side effect

dose-dependently.

| Figure 5Detection of cell migration. (A)

Control group, (B) X-ray irradiation group, (C) L50

group, (D) L100 group, (E) X+L50 group, (F)

X+L100 group. Original amplification, ×200; scale bar,

100 µm. (G) The migrated cell number per field in each

experimental group. Twenty-four hours after treatment, the ability

of cell migration was increased in the X-ray irradiation group

while nadroparin alone or the combined treatments decreased the

cell migration compared to the control group (*p<0.05, t=4.899,

6.773, 11.867, 4.819 and 9.211). Nadroparin inhibited the promotion

of A549 cell migration induced by X-ray irradiation in a

dose-dependent manner. A difference from X-ray irradiation group

(■p<0.05, t=7803 and 10.959); a difference from

L50 (●p<0.05, t=5.944 and 3.163); a

difference from L100 (♦p<0.05,t=3.052); a

difference from X+L50 (▲p<0.05,

t=6.083). |

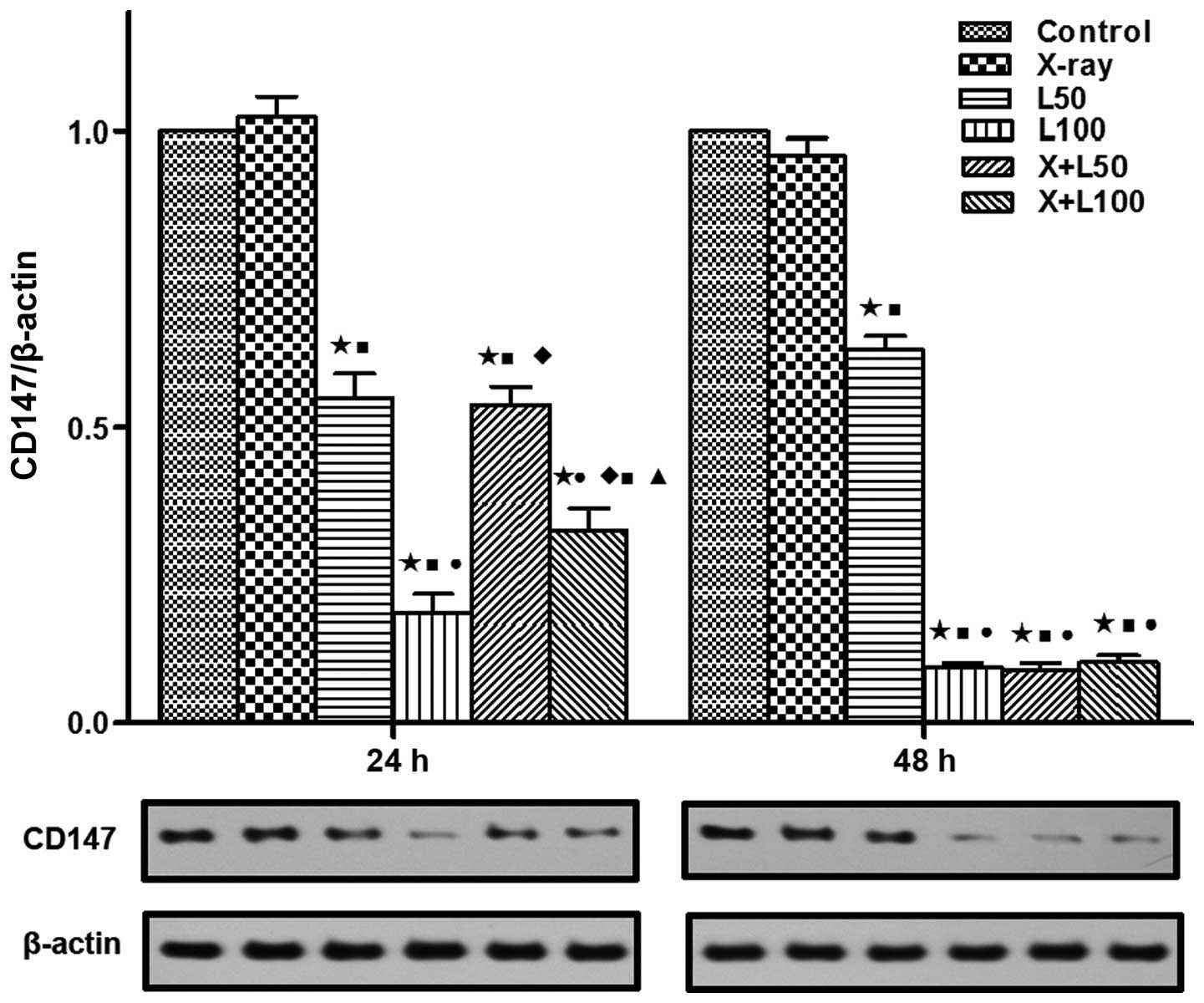

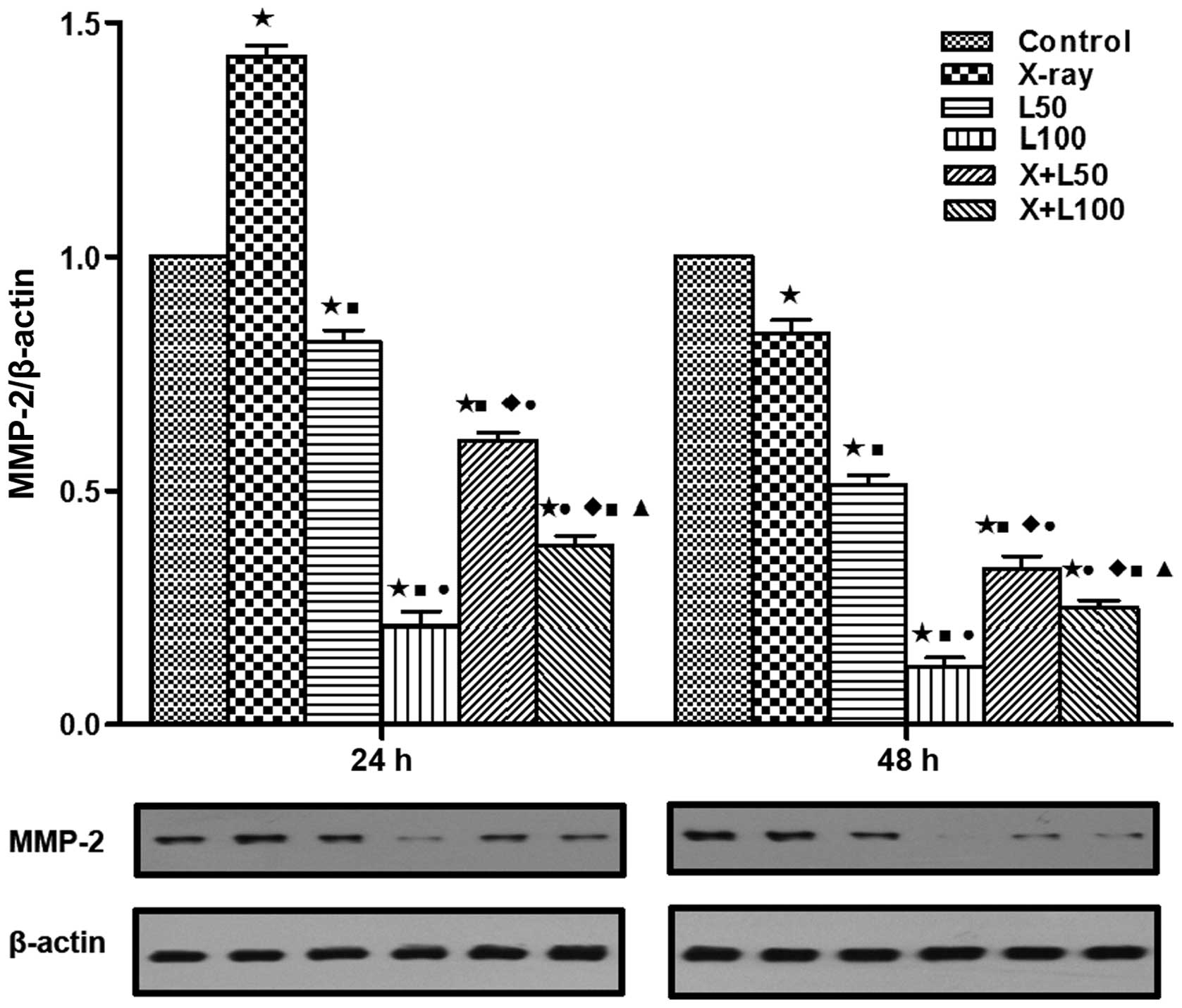

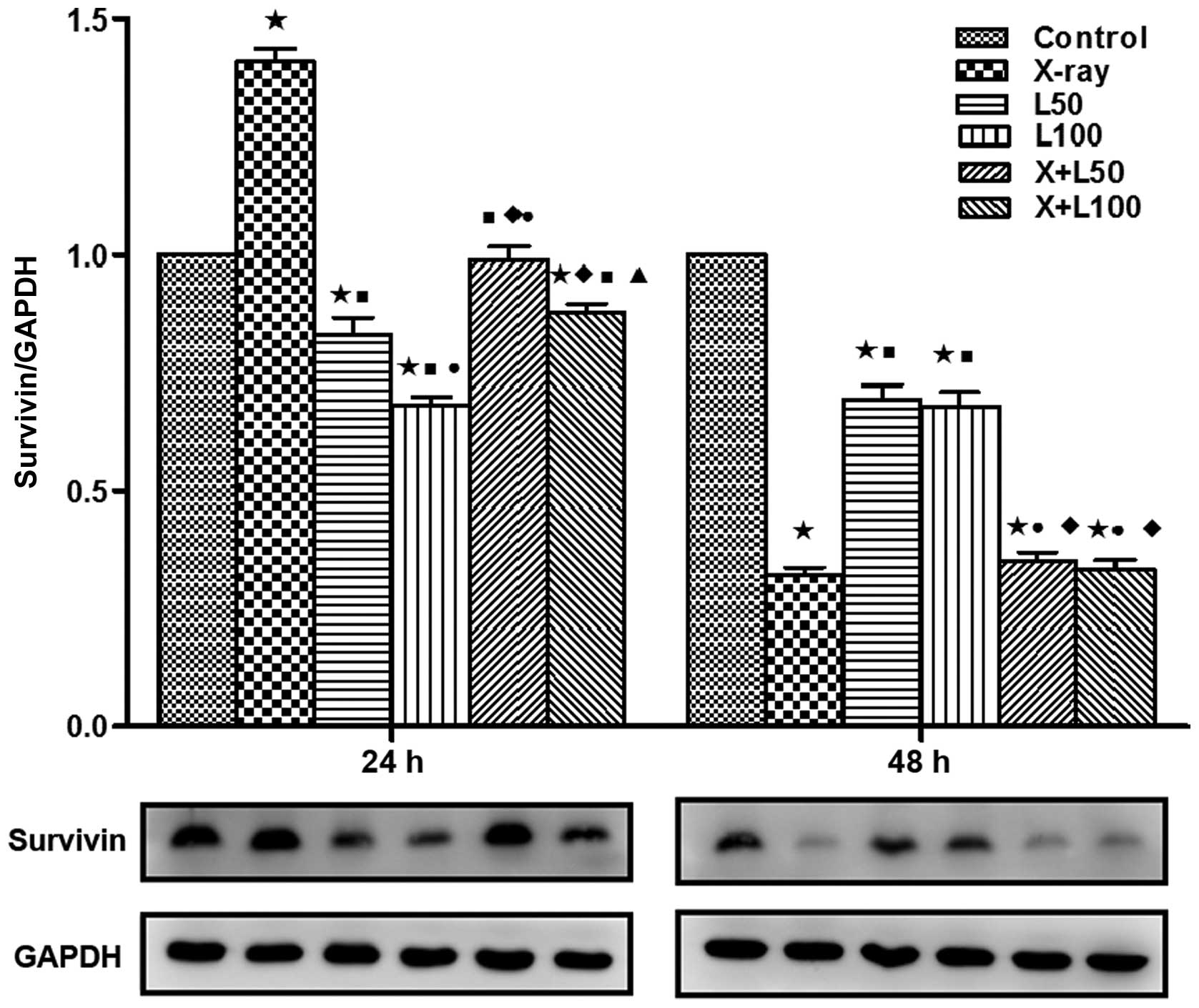

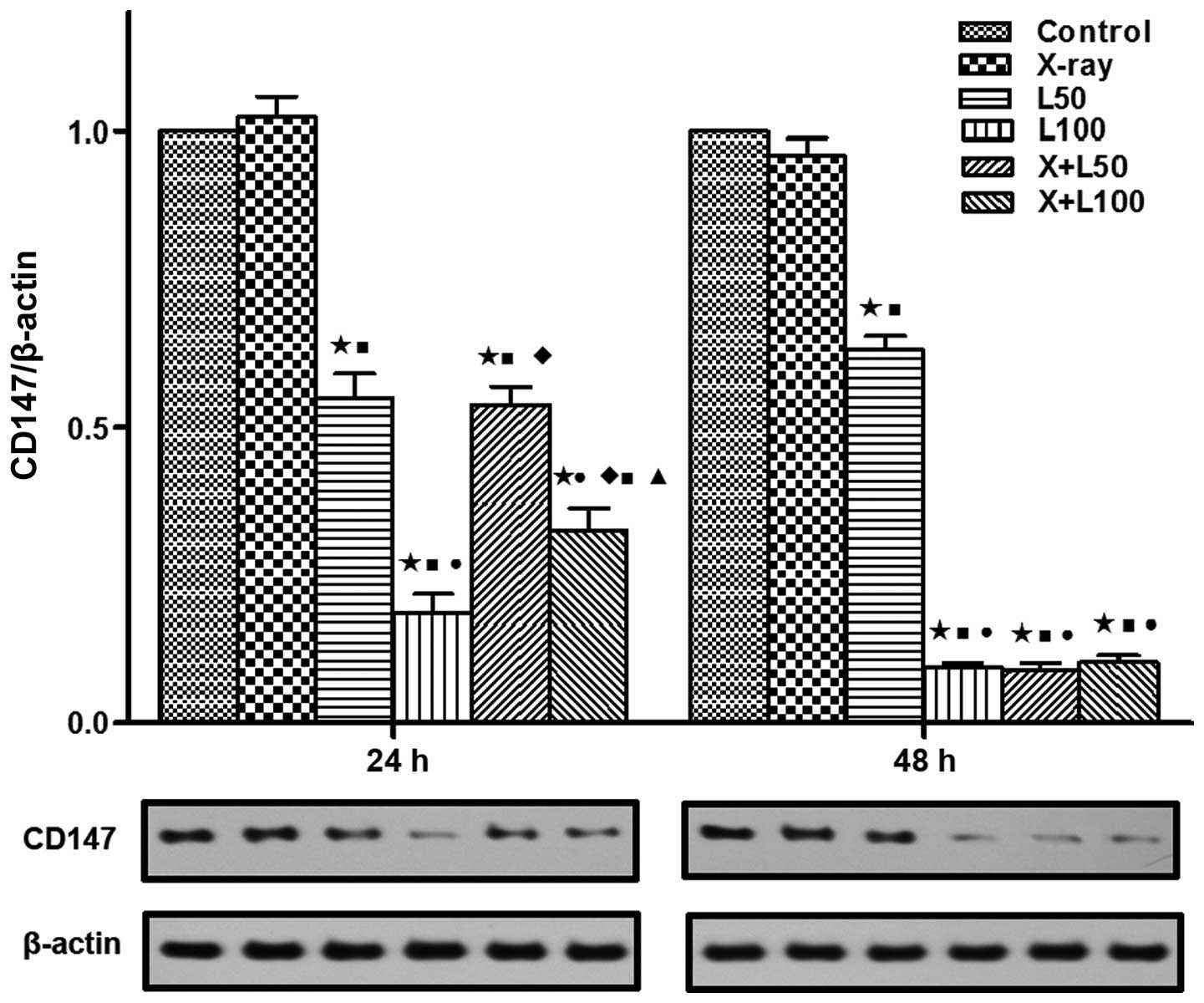

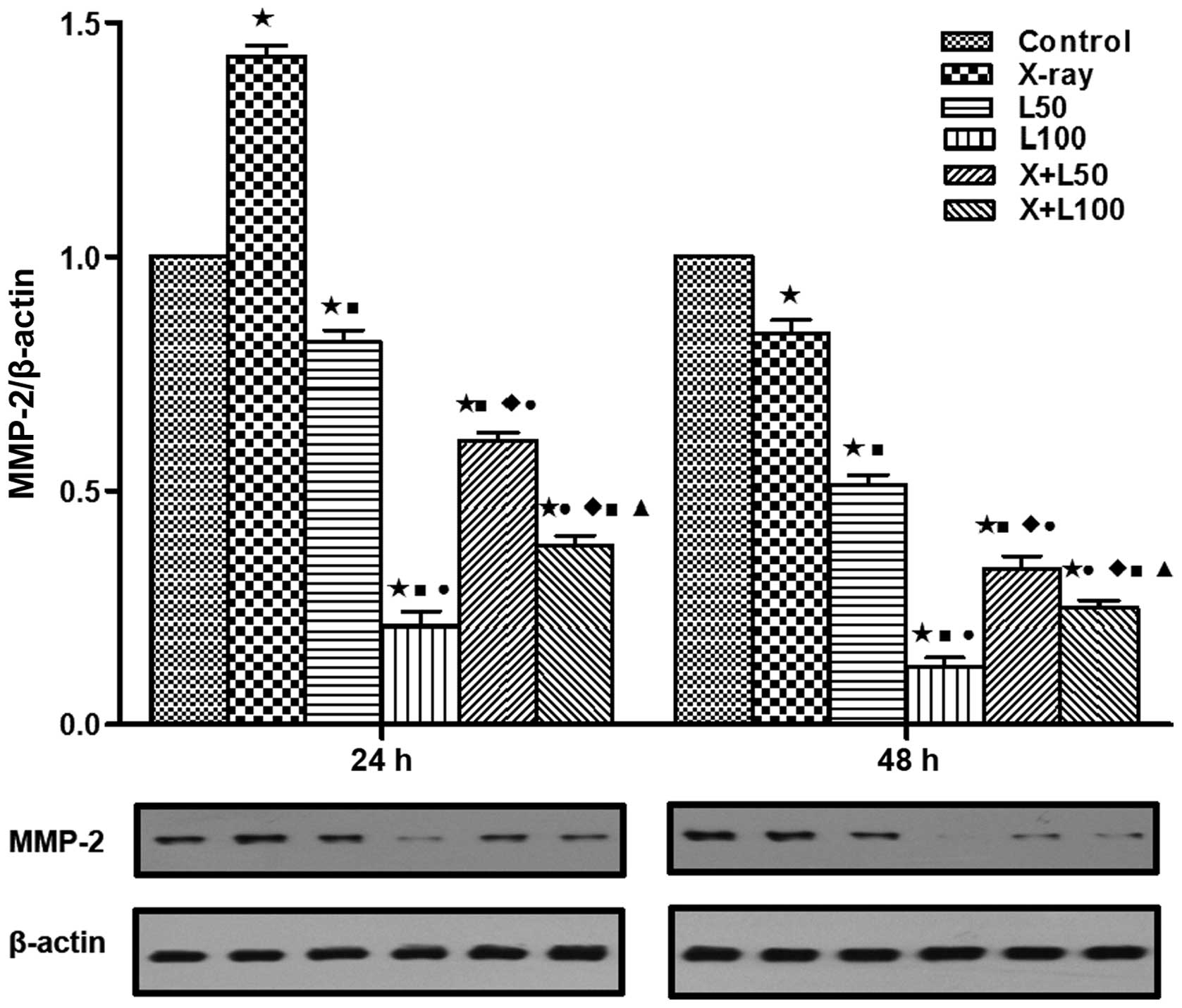

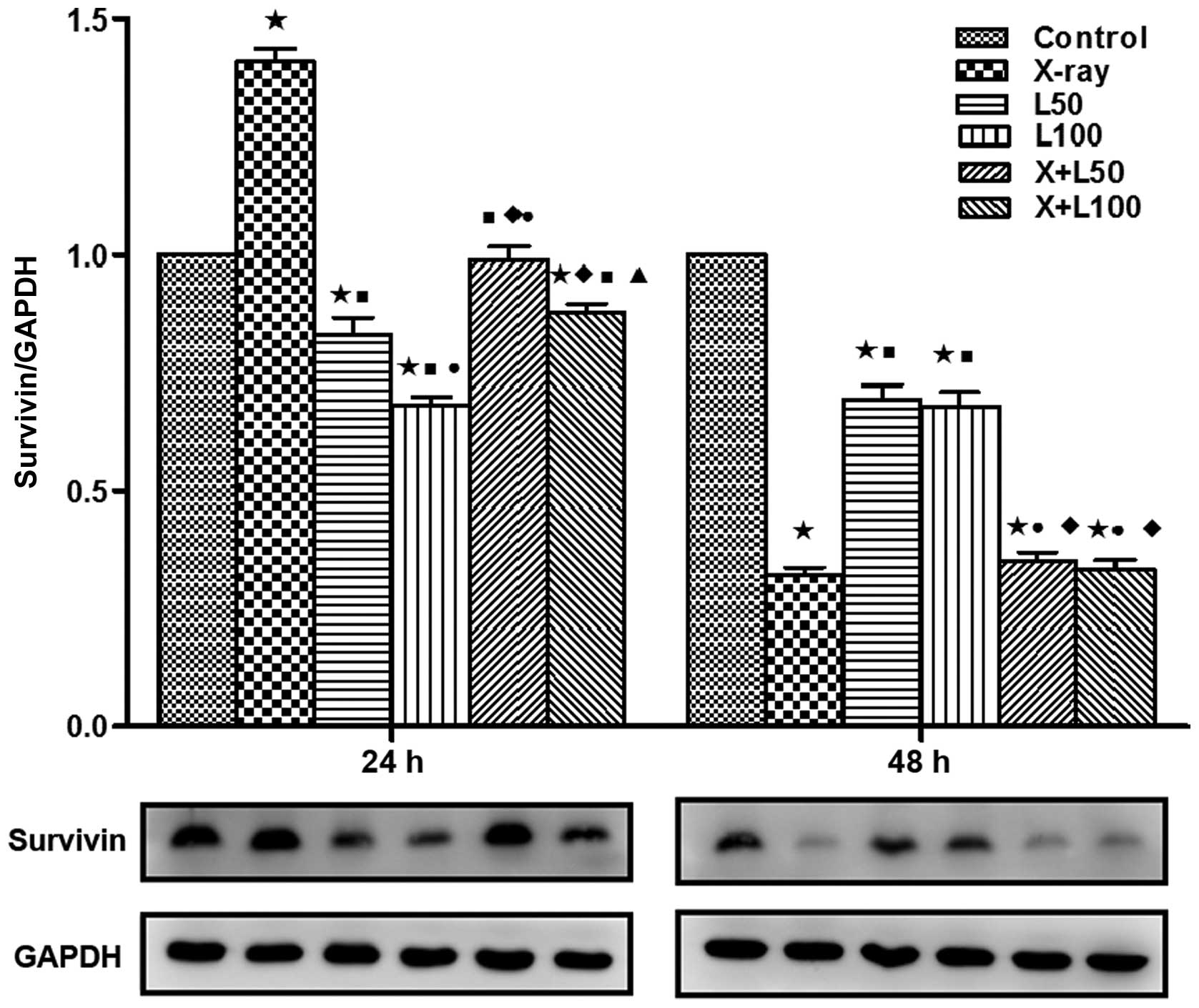

Expression levels of CD147, MMP-2 and

survivin

We examined the protein expression levels of

survivin, CD147 and MMP-2 using western blotting in our study to

investigate the related molecular mechanism of the antitumor effect

associated with nadroparin combined with X-ray radiation on A549

cells. As shown in Fig. 7, the

expression levels of CD147 in A549 cells were inhibited by

nadroparin in a dose-and time-dependent manner while no significant

change of CD147 expression was observed in the X-ray irradiation

group. Furthermore, the expression levels of CD147 were the lowest

in the combined treatment groups and L100 group at the

time of 48 h after treatment (p<0.05). As shown in Fig. 8, at the time of 24 h after

treatment, the expression levels of MMP-2 were upregulated in the

X-ray irradiation group while down-regulated in the groups treated

with nadroparin alone (p<0.05). Interestingly, we observed that

the upregulated effects induced by radiation were inhibited by

nadroparin in the combined treatment groups (p<0.05). Similar

tendency of survivin expressions was observed at the time of 24 h

after treatment, which is shown in Fig.

9. On the other hand, at the time of 48 h after treatment, the

expression levels of MMP-2 were inhibited in the treated groups

compared to the control group and the expression levels of survivin

were downregulated in the treated groups compared to the control

group while the down regulation effect induced by X-ray irradiation

alone or the combined treatment was more significant than

nadroparin alone (p<0.05).

| Figure 7Expression of CD147. Western blotting

demonstrated that CD147 protein expression was significantly

different among each group at 24 and 48 h after treatment in the

lower part of the picture while the upper part shows the relative

expression in each treatment group compared to the control group. A

difference from the control group (*p<0.05, t=11.303, 24.867,

15.121 and 17.772 at 24 h, t=15.858, 114.959, 80.418 and 81.934 at

48 h); a difference from X-ray irradiation group

(■p<0.05, t=8.918, 17.447, 10.419 and 13.493 at 24 h,

t=98.968, 39.360, 28.454 and 28.151 at 48 h); a difference from

L50 (●p<0.05, t=7088 and 4.083 at 24 h,

t=21.811, 20.886 and 20.507 at 48 h); a difference from

L100 (♦p<0.05, t=7902 and 2.811 at 24 h);

a difference from X+L50 (▲p<0.05, t=4374

at 24 h). |

| Figure 8Expression of matrix

metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2). MMP-2 protein expression was

significantly different among each group at 24 and 48 h after

treatment by western blotting assay in the lower part of the

picture. The upper part shows the relative expression in each

treatment group compared to the control group. A difference from

the control group (*p<0.05, t=17.347, 7.186, 26.075, 21.443 and

30.536 at 24 h, t=5.932, 20.911, 47.308, 25.276 and 45.072 at 48

h); a difference from X-ray irradiation group

(■p<0.05, t=17.277, 31.163, 26.693 and 32.715 at 24

h, t=9.128, 21.711, 13.307 and 18.514 at 48 h); a difference from

L50 (●p<0.05, t=15.407, 6.763 and 13.405

at 24 h, t=12.979, 5.006 and 9.173 at 48 h); a difference from

L100 (♦p<0.05, t=11.207 and 4.796 at 24 h,

t=6.553 and 4.956 at 48 h); a difference from X+L50

(▲p<0.05, t=8.160 at 24 h, t=2.801 at 48 h). |

| Figure 9Expression of survivin. Similar to

CD147 and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), survivin protein

expression was also significantly different among each group at 24

and 48 h after treatment by western blotting. A difference from the

control group (*p<0.05, t=14.589, 4.740, 17.331 and 6.550 at 24

h, t=39.077, 10.495, 10.076, 35.048 and 31.658 at 48 h); a

difference from X-ray irradiation group (■p<0.05,

t=12.797, 21.690, 10.421 and 15.791 at 24 h, t=1 1.130 and 9.924 at

48 h); a difference from L50 (●p<0.05,

t=3.789 and 3.448 at 24 h, t=10.006 and 10.131 at 48 h); a

difference from L100 (♦p<0.05, t=8.997 and

7.581 at 24 h, t=8.903 and 9.084 at 48 h); a difference from

X+L50 (▲p<0.05, t=3.231 at 24 h). |

Discussion

Radiotherapy plays an important role in the

treatment of advanced lung cancer. However, the therapeutic

efficacy is compromised due to the resistance to X-rays, tumor

recurrence and metastasis. In addition, radiation has been shown to

stimulate the tumor cell growth and promote invasiveness of

different types of tumor cells in vitro by the upregulation

of secreted proteases, such as MMPs and plasminogen activators

(11–14). Other researchers have made similar

findings in vivo. For instance, Camphausen et al

(15) have reported that radiation

therapy to a primary tumor accelerates metastatic growth in the

Lewis lung cancer mouse model. So it is particularly important to

find the effective combination therapy in order to get the best

therapeutic efficacy in tumor treatment. LMWH has been reported

effective for the treatment of metastasis to some extent, the

mechanisms are proposed as anti-coagulation, inhibition of

heparanase, selectins, adhesion, angiogenesis mediated by the tumor

cells, and the effects on cell cycle and apoptosis (6,16,17).

Furthermore, clinical studies have suggested that LMWHs improve

life expectancy of lung cancer patients (18–20).

So, based on the above, we undertook this experiment to find out

the therapeutic effect of nadroparin combined with radiation, and

if so, whether there was a dose and time-response relationship for

nadroparin also could be analyzed.

Results of our study showed that nadroparin and

X-ray irradiation have synergistic antitumor effect in

vitro. Nadroparin or X-ray irradiation alone could slightly

inhibit the cell viability and enhance the cell apoptosis of A549

cells. The therapeutic effect of X-ray irradiation alone was more

significant than that of nadroparin alone. Furthermore, the

antitumor effect was greatly improved in a dose- and time-dependent

manner when these two treatments were combined.

TGF-β, a kind of multifunctional polypeptide, is

closely related to the development of tumors. Three subunits

defined as TGF-β1, T GF - β2 and TGF-β3 have been cloned in mammals

and the study of TGF-β1 is the most profound and active. Many

studies have shown that TGF-β can enhance growth in a progressive

tumor and the possible mechanisms for these growth enhancing

effects were quite complex, including the enhanced angiogenesis

(21,22), increased peritumoral stroma

formation and induced immunosuppression. In our study, with the

prolonging of time, TGF-β1 levels in the cell supernatants were

increased in the control group while X-ray irradiation or low dose

of nadroparin alone could slightly inhibit the increase of TGF-β1

level. Moreover, TGF-β1 levels were decreased when A549 cells were

treated with high dose of nadroparin and the extent of this

decrease was enhanced when combined with X-ray irradiation. This

result suggested that the antitumor effect of nadroparin combined

with X-ray irradiation may partially relate to the inhibition of

TGF-β1 secreted by A549 cells.

CD147, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily,

is overexpressed in a number of epithelial cell-derived carcinomas

and is associated with tumor development and metastasis by

activating the fibroblasts producing MMPs (23,24).

Wu et al (25) found that

CD147 induced resistance to ionizing radiation in hepatocellular

carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. In our study,

we found that nadroparin alone could inhibit the expression of

CD147 and MMP-2 in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The

expression levels of CD147 and MMP-2 were significantly lower in

the combined treatment groups than the control group or X-ray

irradiation group at the time of 24 and 48 h after treatment.

Survivin, the smallest member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein

(IAP) family, encoded by a single gene located on the human 17q25

chromosome with a molecular mass of 16.5 kDa, was first isolated by

Ambrosini et al (26) at

Yale University. The biological functions of survivin are also

quite complex, including inhibiting tumor cell apoptosis (27,28),

promoting cell proliferation, participating in the regulation of

cell cycle (29–31) and promoting blood vessel formation

(32), which plays an important

role in the development of cancer. Recently, increasing number of

reports have shown that survivin is an independent prognostic

factor for tumor therapy (33,34).

It has also showed that survivin overexpression has been correlated

with elevated resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy in recent

studies (35, 36). Investigations have reported that

ionizing radiation at doses of 1 to 8 Gy is known to significantly

elevate survivin levels in malignant cells (37–39).

Therefore, blocking tumor cell survivin function or inhibiting its

expression may inhibit cell apoptosis and proliferation and enhance

its sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In our study, we

found that nadroparin alone could inhibit the expression of

survivin, which was dose-dependent, but not time-dependent. The

expression of survivin was significantly upregulated by X-ray

irradiation at the time of 24 h after treatment and this effect was

inhibited by nadroparin in a dose-dependent manner. Based on the

results above, we can conclude that the expression of CD147, MMP-2

and survivin was effectively and enduringly inhibited by nadroparin

combined with X-ray irradiation in the whole process of the

treatment. This result suggested that the antitumor effect of

nadroparin combined with X-ray irradiation may partially relate to

the inhibited expressions of CD147, MMP-2 and survivin in A549

cells.

Taken together, addition of nadroparin to

combination radiotherapy resulted in a powerful synergistic

antitumor effect in lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. The mechanism

may be associated with the induction of cell apoptosis, reduction

of TGF-β1 level, inhibition of cell invasion and migration and

downregulated expression of CD147, MMP-2 and survivin. Importantly,

these results revealed that nadroparin could inhibit the promotion

of cell migration and invasion induced by radiotherapy in a

dose-dependent manner. In brief, nadroparin combined with

radiotherapy exerted a synergistic antitumor function, which may

provide a novel strategy for cancer treatment. However, further

investigations are required due to the complexity of structure and

function of different LMWHs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Personnel Training

Plan of Jinshan Hospital (2015–7).

References

|

1

|

Padera TP, Kadambi A, di Tomaso E,

Carreira CM, Brown EB, Boucher Y, Choi NC, Mathisen D, Wain J, Mark

EJ, et al: Lymphatic metastasis in the absence of functional

intratumor lymphatics. Science. 296:1883–1886. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mitrovska S and Jovanova S: Low-molecular

weight heparin enoxaparin in the treatment of acute coronary

syndromes without ST segment elevation. Bratisl Lek Listy.

110:45–48. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mousa SA and Petersen LJ: Anti-cancer

properties of low-molecular-weight heparin: Preclinical evidence.

Thromb Haemost. 102:258–267. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Icli F, Akbulut H, Utkan G, Yalcin B,

Dincol D, Isikdogan A, Demirkazik A, Onur H, Cay F and Büyükcelik

A: Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) increases the efficacy of

cisplatinum plus gemcitabine combination in advanced pancreatic

cancer. J Surg Oncol. 95:507–512. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Yu CJ, Ye SJ, Feng ZH, Ou WJ, Zhou XK, Li

LD, Mao YQ, Zhu W and Wei YQ: Effect of Fraxiparine, a type of low

molecular weight heparin, on the invasion and metastasis of lung

adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Oncol Lett. 1:755–760. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Carmazzi Y, Iorio M, Armani C, Cianchetti

S, Raggi F, Neri T, Cordazzo C, Petrini S, Vanacore R, Bogazzi F,

et al: The mechanisms of nadroparin-mediated inhibition of

proliferation of two human lung cancer cell lines. Cell Prolif.

45:545–556. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Niu Q, Wang W, Li Y, Ruden DM, Wang F, Li

Y, Wang F, Song J and Zheng K: Low molecular weight heparin ablates

lung cancer cisplatin-resistance by inducing proteasome-mediated

ABCG2 protein degradation. PLoS One. 7:e410352012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Seidensticker M, Seidensticker R, Damm R,

Mohnike K, Pech M, Sangro B, Hass P, Wust P, Kropf S, Gademann G,

et al: Prospective randomized trial of enoxaparin, pentoxifylline

and ursodeoxycholic acid for prevention of radiation-induced liver

toxicity. PLoS One. 9:e1127312014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bae SM, Kim JH, Chung SW, Byun Y, Kim SY,

Lee BH, Kim IS and Park RW: An apoptosis-homing peptide-conjugated

low molecular weight heparin-taurocholate conjugate with antitumor

properties. Biomaterials. 34:2077–2086. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Erduran E, Tekelioğlu Y, Gedik Y and

Yildiran A: Apoptotic effects of heparin on lymphoblasts,

neutrophils, and mononuclear cells: Results of a preliminary in

vitro study. Am J Hematol. 61:90–93. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jadhav U and Mohanam S: Response of

neuroblastoma cells to ionizing radiation: Modulation of in vitro

invasiveness and angiogenesis of human microvascular endothelial

cells. Int J Oncol. 29:1525–1531. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kaliski A, Maggiorella L, Cengel KA, Mathe

D, Rouffiac V, Opolon P, Lassau N, Bourhis J and Deutsch E:

Angiogenesis and tumor growth inhibition by a matrix

metalloproteinase inhibitor targeting radiation-induced invasion.

Mol Cancer Ther. 4:1717–1728. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Park CM, Park MJ, Kwak HJ, Lee HC, Kim MS,

Lee SH, Park IC, Rhee CH and Hong SI: Ionizing radiation enhances

matrix metalloproteinase-2 secretion and invasion of glioma cells

through Src/epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated p38/Akt and

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways. Cancer Res.

66:8511–8519. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhai GG, Malhotra R, Delaney M, Latham D,

Nestler U, Zhang M, Mukherjee N, Song Q, Robe P and Chakravarti A:

Radiation enhances the invasive potential of primary glioblastoma

cells via activation of the Rho signaling pathway. J Neurooncol.

76:227–237. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Camphausen K, Moses MA, Beecken WD, Khan

MK, Folkman J and O'Reilly MS: Radiation therapy to a primary tumor

accelerates metastatic growth in mice. Cancer Res. 61:2207–2211.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Norrby K: Low-molecular-weight heparins

and angiogenesis. APMIS. 114:79–102. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Debergh I, Van Damme N, Pattyn P, Peeters

M and Ceelen WP: The low-molecular-weight heparin, nadroparin,

inhibits tumour angiogenesis in a rodent dorsal skinfold chamber

model. Br J Cancer. 102:837–843. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kakkar AK, Levine MN, Kadziola Z, Lemoine

NR, Low V, Patel HK, Rustin G, Thomas M, Quigley M and Williamson

RC: Low molecular weight heparin, therapy with dalteparin, and

survival in advanced cancer: The fragmin advanced malignancy

outcome study (FAMOUS). J Clin Oncol. 22:1944–1948. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Altinbas M, Coskun HS, Er O, Ozkan M, Eser

B, Unal A, Cetin M and Soyuer S: A randomized clinical trial of

combination chemotherapy with and without low-molecular-weight

heparin in small cell lung cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2:1266–1271.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Klerk CP, Smorenburg SM, Otten HM, Lensing

AW, Prins MH, Piovella F, Prandoni P, Bos MM, Richel DJ, van

Tienhoven G, et al: The effect of low molecular weight heparin on

survival in patients with advanced malignancy. J Clin Oncol.

23:2130–2135. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tuxhorn JA, McAlhany SJ, Yang F, Dang TD

and Rowley DR: Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta

activity decreases angiogenesis in a human prostate cancer-reactive

stroma xenograft model. Cancer Res. 62:6021–6025. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li C, Guo B, Bernabeu C and Kumar S:

Angiogenesis in breast cancer: The role of transforming growth

factor beta and CD105. Microsc Res Tech. 52:437–449. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kanekura T and Chen X: CD147/basigin

promotes progression of malignant melanoma and other cancers. J

Dermatol Sci. 57:149–154. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Weidle UH, Scheuer W, Eggle D, Klostermann

S and Stockinger H: Cancer-related issues of CD147. Cancer Genomics

Proteomics. 7:157–169. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wu J, Li Y, Dang YZ, Gao HX, Jiang JL and

Chen ZN: HAb18G/CD147 promotes radioresistance in hepatocellular

carcinoma cells: A potential role for integrin β1 signaling. Mol

Cancer Ther. 14:553–563. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Ambrosini G, Adida C and Altieri DC: A

novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and

lymphoma. Nat Med. 3:917–921. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tamm I, Wang Y, Sausville E, Scudiero DA,

Vigna N, Oltersdorf T and Reed JC: IAP-family protein survivin

inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax,

caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 58:5315–5320.

1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Suzuki A, Ito T, Kawano H, Hayashida M,

Hayasaki Y, Tsutomi Y, Akahane K, Nakano T, Miura M and Shiraki K:

Survivin initiates procaspase 3/p21 complex formation as a result

of interaction with Cdk4 to resist Fas-mediated cell death.

Oncogene. 19:1346–1353. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li F, Ambrosini G, Chu EY, Plescia J,

Tognin S, Marchisio PC and Altieri DC: Control of apoptosis and

mitotic spindle checkpoint by survivin. Nature. 396:580–584. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Skoufias DA, Mollinari C, Lacroix FB and

Margolis RL: Human survivin is a kinetochore-associated passenger

protein. J Cell Biol. 151:1575–1582. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Suzuki A, Hayashida M, Ito T, Kawano H,

Nakano T, Miura M, Akahane K and Shiraki K: Survivin initiates cell

cycle entry by the competitive interaction with Cdk4/p16(INK4a) and

Cdk2/cyclin E complex activation. Oncogene. 19:3225–3234. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Nassar A, Lawson D, Cotsonis G and Cohen

C: Survivin and caspase-3 expression in breast cancer: Correlation

with prognostic parameters, proliferation, angiogenesis, and

outcome. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 16:113–120. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Monzó M, Rosell R, Felip E, Astudillo J,

Sánchez JJ, Maestre J, Martín C, Font A, Barnadas A and Abad A: A

novel anti-apoptosis gene: Re-expression of survivin messenger RNA

as a prognosis marker in non-small-cell lung cancers. J Clin Oncol.

17:2100–2104. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kren L, Brazdil J, Hermanova M, Goncharuk

VN, Kallakury BV, Kaur P and Ross JS: Prognostic significance of

anti-apoptosis proteins survivin and bcl-2 in non-small cell lung

carcinomas: A clinicopathologic study of 102 cases. Appl

Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 12:44–49. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yoshida H, Sumi T, Hyun Y, Nakagawa E,

Hattori K, Yasui T, Morimura M, Honda K, Nakatani T and Ishiko O:

Expression of survivin and matrix metalloproteinases in

adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix.

Oncol Rep. 10:45–49. 2003.

|

|

36

|

Ikeguchi M, Liu J and Kaibara N:

Expression of survivin mRNA and protein in gastric cancer cell line

(MKN-45) during cisplatin treatment. Apoptosis. 7:23–29. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jin XD, Gong L, Guo CL, Hao JF, Wei W, Dai

ZY and Li Q: Survivin expressions in human hepatoma HepG2 cells

exposed to ionizing radiation of different LET. Radiat Environ

Biophys. 47:399–404. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Rödel F, Reichert S, Sprenger T, Gaipl US,

Mirsch J, Liersch T, Fulda S and Rödel C: The role of survivin for

radiation oncology: Moving beyond apoptosis inhibition. Curr Med

Chem. 18:191–199. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Rödel C, Haas J, Groth A, Grabenbauer GG,

Sauer R and Rödel F: Spontaneous and radiation-induced apoptosis in

colorectal carcinoma cells with different intrinsic

radiosensitivities: Survivin as a radioresistance factor. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 55:1341–1347. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|