Introduction

Thyroid cancer, the most common endocrine malignancy

worldwide, has increased 3-fold in the past 3 decades (1,2).

Well-differentiated thyroid cancer (WDTC), including papillary and

follicular thyroid cancer, represents >90% of all thyroid

cancers (3), and patients with WDTC

have a 10-year survival of 80–95%. Many studies have profiled WDTC

genes and rearrangements of RET/PTC and PAX8/PPARγ

(4), and frequent (70%) point

mutations of BRAF and RAS genes, which alter the

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway (5–7) were

documented in WDTC. Several genes, such as MUC1, PD-L1,

DPP4, and mutations of the BRAFV600E and

TERT promoter, have been reported as prognostic markers

(8–11).

For WDTC, 10-year survival is reduced to 14–40% when

distant metastasis (DM) occurs (12–14).

For patients with metastases, radioactive iodine (131I)

has been the mainstay of treatment, selectively combined with

surgical intervention, external beam radiation and chemotherapy

(15). Metastatic lesions are

sometimes resistant to 131I, so treatment options are

limited and survival is poor (10-year survival, 10%) (14,16).

Recurrence also greatly contributes to the morbidity of WDTC

(17,18), and recurrence at 30 years is 35%,

most being local with 32% being DM (17). Thus, we must identify potential

targets to improve therapeutic strategies to prevent metastasis and

recurrence.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of endogenous small

(18–22 nucleotide) non-coding RNAs. Gene expression regulation by

miRNAs is of interest because many miRNAs in WDTC, such as miR-221,

miR-222 and miR-146 (19–21), have been reported to have critical

roles in the regulation of apoptosis, proliferation, the cell cycle

and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by negatively regulating

mRNAs post-transcriptionally. Other studies on mRNA and miRNA

expression indicate a miRNA-mRNA regulatory network that may

provide clues for genetic deregulation in WDTC (22,23).

Although many studies have focused on the tumorigenesis of WDTC,

few studies have identified the mechanism of metastasis and

recurrence in WDTC. This is due to the fact that tissues must be

taken from metastatic sites, yet metastasis-prone sites of WDTC,

such as the brain and bones, are challenging to sample properly.

Second, the incidence of metastasis and recurrence is relatively

low, and as such, WDTC patients have better outcomes than other

malignancies.

In the present study, we collected tissue samples

from four separate stages of WDTC: Normal, cancerous, metastatic

and recurrent stages and we performed mRNA and miRNA microarray

analysis. By integrating our study with gene expression data from

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (21), we revealed novel prognostic markers

and key genes related to the progression of WDTC and possible

pathways involved in WDTC recurrence.

Materials and methods

Pipeline and workflow

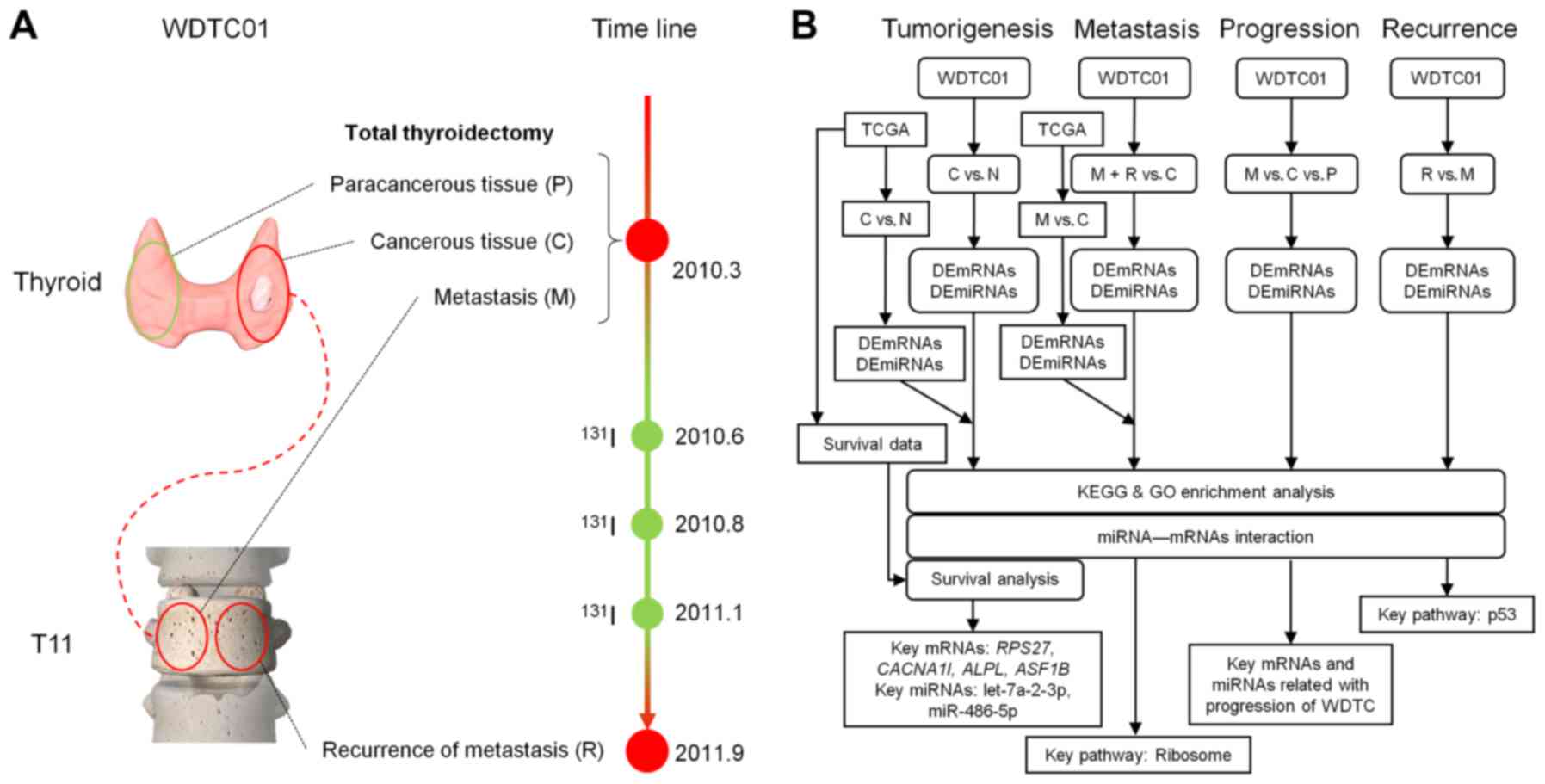

We observed changes in the expression of mRNA and

miRNA in normal, cancerous, metastatic and recurrent stages of

WDTC. To study tumorigenesis and metastasis, we overlapped our

results with differentially expressed mRNAs (DEmRNAs) and miRNAs

(DEmiRNAs) from TCGA sequencing data, which contained more than 500

cancerous samples of papillary thyroid cancer, 59 normal samples, 8

lymph node metastatic (LNM) samples and corresponding clinical

data. We performed survival analysis to identify prognostic

influence, enrichment analysis to reveal relevant pathways and

ontology of gene sets and miRNA target prediction to depict

possible miRNA-mRNA interactions in WDTC (Fig. 1).

Patient and sample preparation

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board and Ethics Committee of The Shanghai Tenth People's

Hospital, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

(SHSY-IEC-KY-4.0/17-13/01). In March 2010, case WDTC01 was a

40-year-old male patient, diagnosed with follicular thyroid cancer

and distant bone metastasis (BM) in the 11th thoracic vertebrae.

Total thyroidectomy was performed at Zhongshan Hospital, Shanghai,

China. Paracancerous and cancerous tissues were collected during

surgery. To relieve neurological symptoms of the lower extremity

caused by BM, the metastatic lesion was debulked, collected and

internally fixed. After three 131I radiation ablations,

local recurrence was observed at the 11th thoracic vertebrae on

September 2011 and the recurred lesion was collected during surgery

(Fig. 1). All samples were

immediately stored at −80°C until use. Total RNA was harvested

using TRIzol (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham,

MA, USA) and an miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany)

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Genome-wide transcriptional profiling

with Agilent microarray and microRNA microarray expression

profiling

RNA was immediately shipped on dry ice to KangChen

Bio-Tech (Shanghai, China) for mRNA and miRNA microarray assay. For

analysis via the Agilent Whole Human Genome Oligo Microarray

platform, total RNA from each sample was amplified and transcribed

into fluorescent cRNA using the manufacturer's instructions

(Agilent's Quick Amp Labeling protocol, version 5.7; Agilent

Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Labeled cRNAs were hybridized

onto the Whole Human Genome Oligo Microarray (4×44 K; Agilent

Technologies). After washing the slides, arrays were scanned using

the Agilent Scanner G2505C. Agilent Feature Extraction software

(version 11.0.1.1) was used to analyze the acquired array images.

Quantile normalization and subsequent data processing were

performed using the GeneSpring GX v11.5.1 software package (Agilent

Technologies).

For the miRNA microarray, samples were labeled using

the miRCURY Hy3/Hy5 Power labeling kit and hybridized with a

miRCURY LNA Array (v.16.0) (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark). Following

washing, the slides were scanned using the Axon GenePix 4000B

microarray scanner. Scanned images were then imported into GenePix

Pro 6.0 software (Axon Instruments; Molecular Devices, LLC,

Sunnyvale, CA, USA) for grid alignment and data extraction.

Replicated miRNAs were averaged and miRNAs in which intensities

were ≥50 in all samples were chosen for calculating a normalization

factor.

Targeting prediction and enrichment

analysis

The online prediction tool MiRWalk 2.0 (24) was used to predict interactions

between miRNAs and mRNAs. In addition, miRanda (25) and TargetScan (26) were selected to generate an

intersecting gene list. When an mRNA was predicted by all three

databases, it was considered a target for the miRNA. Biological

pathways defined by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG) (27) and Gene Ontology (GO)

(28) were analyzed using the

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

(DAVID) (29). DAVID provides a set

of functional annotations for many genes. In the present study,

KEGG pathway and GO terms were selected with a threshold of

P<0.05.

Statistical analysis

For WDTC01, mRNAs and miRNAs with fold-changes (FC)

>1.5 times were defined as differentially expressed and

considered for analysis. RNA sequencing data with 505 samples of

papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), 59 normal control and eight LNM,

with the −3 miRNA sequencing data of 502 samples of PTC, 59 normal

control and eight LNM from TCGA thyroid carcinoma (THCA), and

survival data were downloaded from the TCGA analytical tool UCSC

Xena (http://xena.ucsc.edu). However,

recurrent sites were not available. The unit for the mRNA

sequencing data was log2 (RSEM+1) and the unit for the miRNA

sequencing data was log2 (RPM+1). To screen differentially

expressed mRNAs and miRNAs with a median expression >0, we used

the linear model of the limma package (30) of R-3.4.1. Benjamin and Hochberg's

(31) correction was applied to

ensure a false discovery rate (FDR). For comparisons between cancer

and normal samples, DEmRNAs and DEmiRNAs were identified when FC

>1.5, P<0.05 and FDR <0.05. For comparisons between 8 LNM

and cancer samples, criteria were FC >1.5 and P<0.05.

To depict expression differences, a scatter plot was

used to describe averages and standard deviations of expression. To

address overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS)

for patients, we retrieved follow-up states for patients in the

clinical data matrix from TCGA and merged this with the expression

matrix and performed Kaplan-Meier analysis for each mRNA and miRNA

with survival of R. OS and RFS were considered significant when

log-rank test was P<0.05.

Results

Upregulated ASF1B and ALPL and

downregulated RPS27, CACNA1I, let-7a-2-3p and miR-486-5p are

related to the prognosis of WDTC

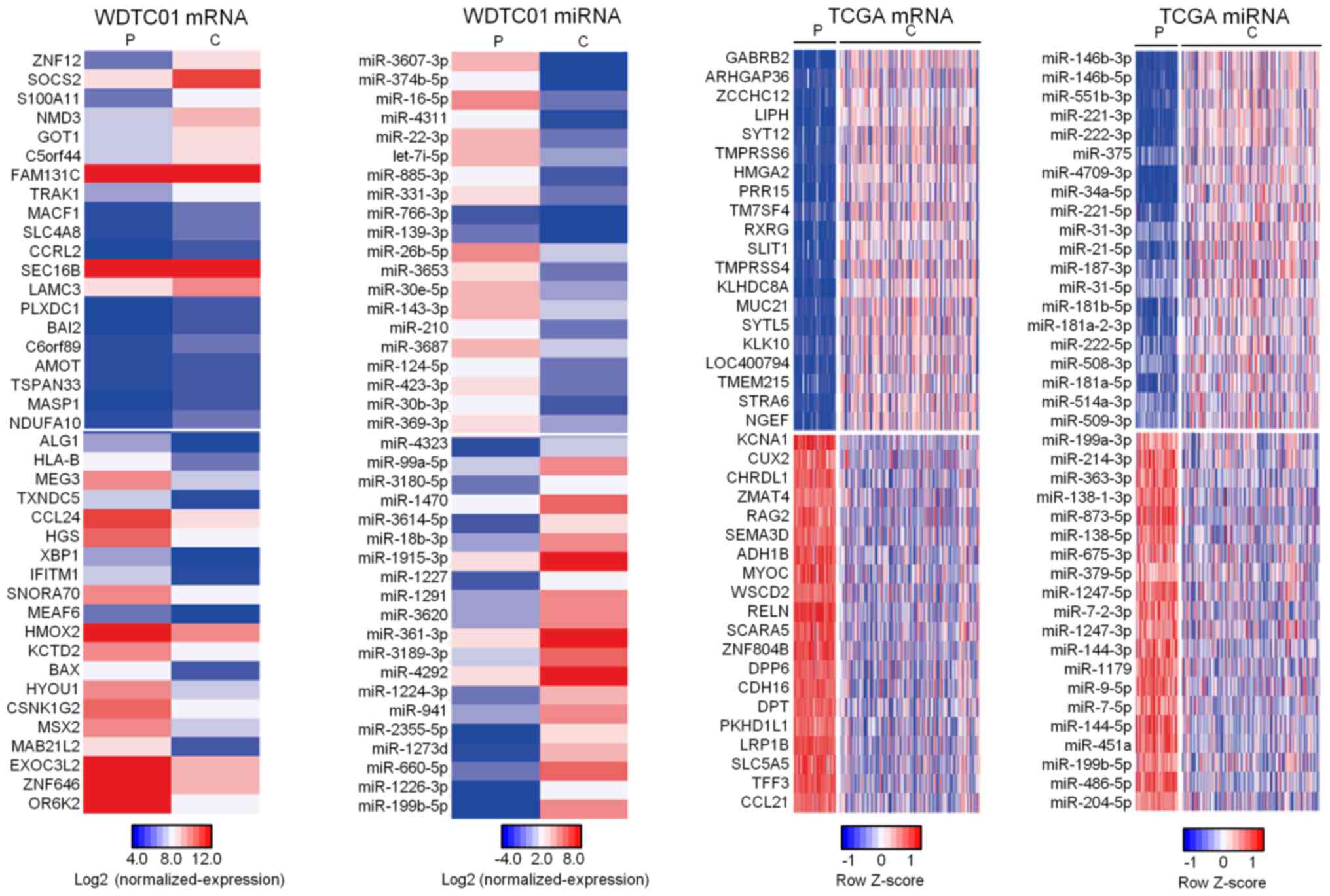

We observed 444 upregulation and 740 downregulated

DEmRNAs and 114 upregulation and 105 downregulated DEmiRNAs in

cancerous tissue for WDTC01 (Fig.

2). To validate commonly expressed DEmRNAs and miRNAs in WDTC,

DEmRNAs and miRNAs were compared with TCGA data. We identified 49

upregulated and 53 downregulated DEmRNAs, along with 2 upregulated

and 10 downregulated DEmiRNAs, which were commonly deregulated

(Fig. 3A). We selected overlapping

molecules to perform survival analysis and construct a miRNA-mRNA

network using online miRNA-target predicting tools. We found 10

overlapping mRNAs that interacted with 21 commonly deregulated

mRNAs (Fig. 3B).

Among commonly expressed DEmRNAs and miRNAs, high

expression of alkaline phosphatase, liver/bone/kidney

(ALPL), low expression of ribosomal protein S27

(RPS27) and calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 I

(CACNA1I) were associated with overall survival of WCDT.

High expression of anti-silencing function 1B histone chaperone

(ASF1B) and low expression of let-7a-2-3p and miR-486-3p

were associated with RFS for WDTC (Fig.

3C).

Expression patterns are related to

metastatic variations of WDTC

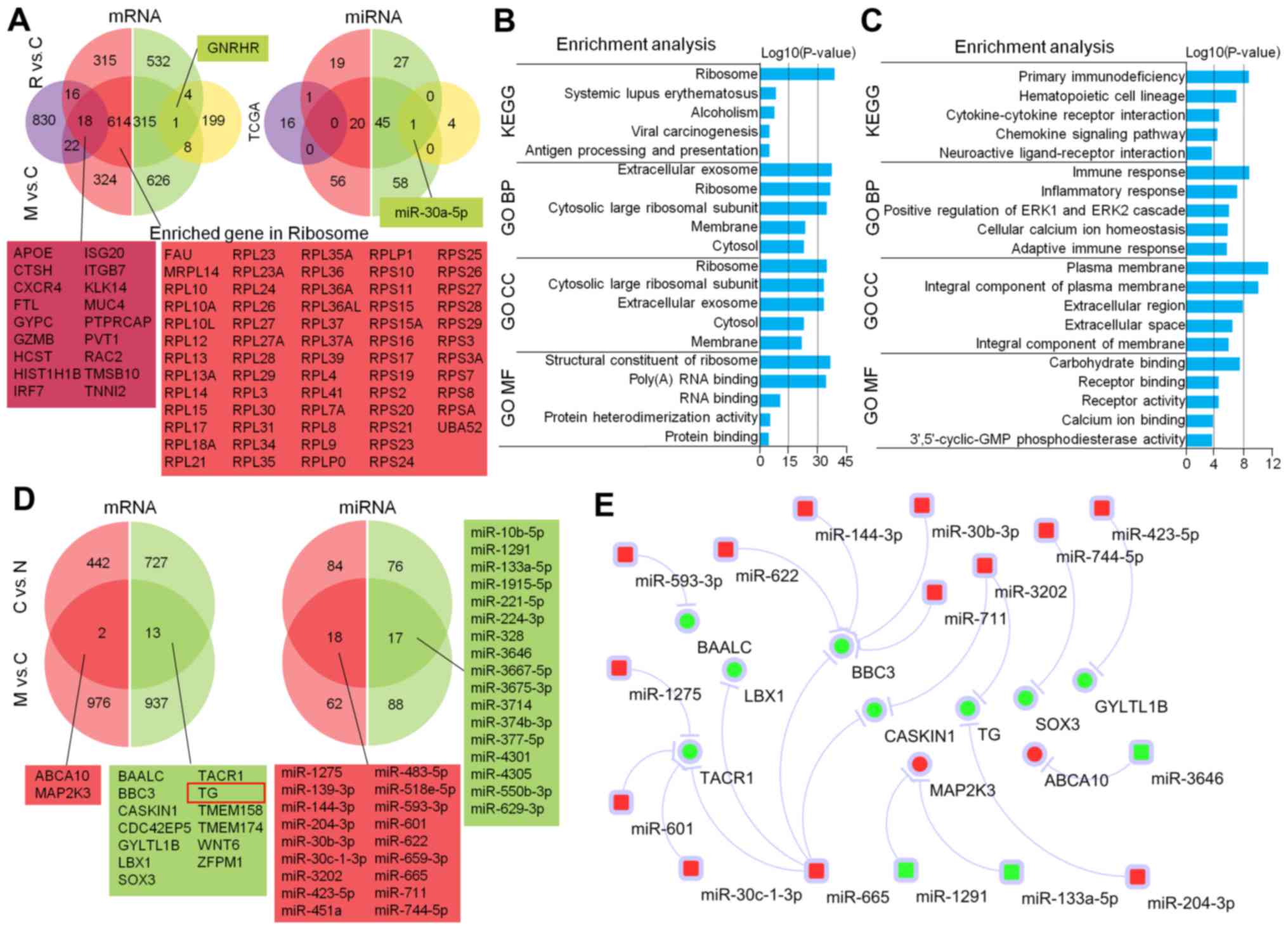

We identified 632 upregulation and 316 downregulated

DEmRNAs and 20 upregulation and 46 downregulated DEmiRNAs in DM and

recurrent lesions of WDTC01. To identify evolutionary signatures

related to metastasis of WDTC, we investigated common expression

patterns shared with BM from WDTC01 and LNM from TCGA. DEmRNAs and

miRNAs from both metastatic sources were different. We found 18

upregulated DEmRNAs, such as apolipoprotein E (ApoE),

cathepsin H (CTSH), C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4

(CXCR4) and mucin 4 (MUC4) and one downregulated

DEmRNA, gonadotropin releasing hormone receptor (GNRHR) in

BM and LNM. For miRNAs, downregulation of miR-30a-5p occurred in BM

and LNM (Fig. 4A).

Hyper-activation of the ribosome

pathway contributes to DM of WDTC as indicated by enrichment

analysis

To analyze features of BM and LNM of WDTC, we

performed enrichment analysis with DEmRNAs that did not overlap

between the two metastatic sources. Ribosomes, first listed in KEGG

analysis and cell component (CC) in the GO analysis, were

involved.

Significant biological process (BP) and molecular

function (MF) terms were related to the translational process. Our

analysis focused on the ribosome pathway in which 63 enriched genes

were upregulated (Fig. 4B). For

LNM, KEGG terms were related to immune-related pathways. BP terms

were related to the ERK1/ERK2 signaling pathway and cellular

calcium ion homeostasis. CC terms were related to extracellular

activity and MF terms were associated with regulation of ion and

protein binding (Fig. 4C).

Comparison among different stages of

WDTC reveals that upregulation and downregulated DEmRNAs and

DEmiRNAs are associated with tumor progression

To investigate DEmRNAs and miRNAs associated with

tumor progression, we analyzed three stages of WDTC01 (normal,

cancerous and metastatic tissues) before 131I treatment.

Upregulated DEmRNAs included ATP-binding cassette subfamily A

member 10 (ABCA10) and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase

Kinase 3 (MAP2K3) and 13 downregulated DEmRNAs, such as BCL2

binding component 3 (BBC3) and thyroglobulin (TG), as

well as 18 upregulation and 17 downregulated DEmiRNAs that were

constantly deregulated with tumor progression (Fig. 4D).

Potential interactions among DEmRNAs and miRNAs

using the aforementioned algorithm suggested that downregulation of

miR-1291, miR-133a-5p and miR-3646 may increase the expression of

MAP2K3 and ABCA10. Downregulation of the

pro-apoptotic gene BBC3 may be caused by increases in 5

different progression-related miRNAs. The lineage upregulation of

miR-204-3p and miR-3202 may interfere with the expression of

TG, an important marker for thyroid cancer cell stemness

(Fig. 4E).

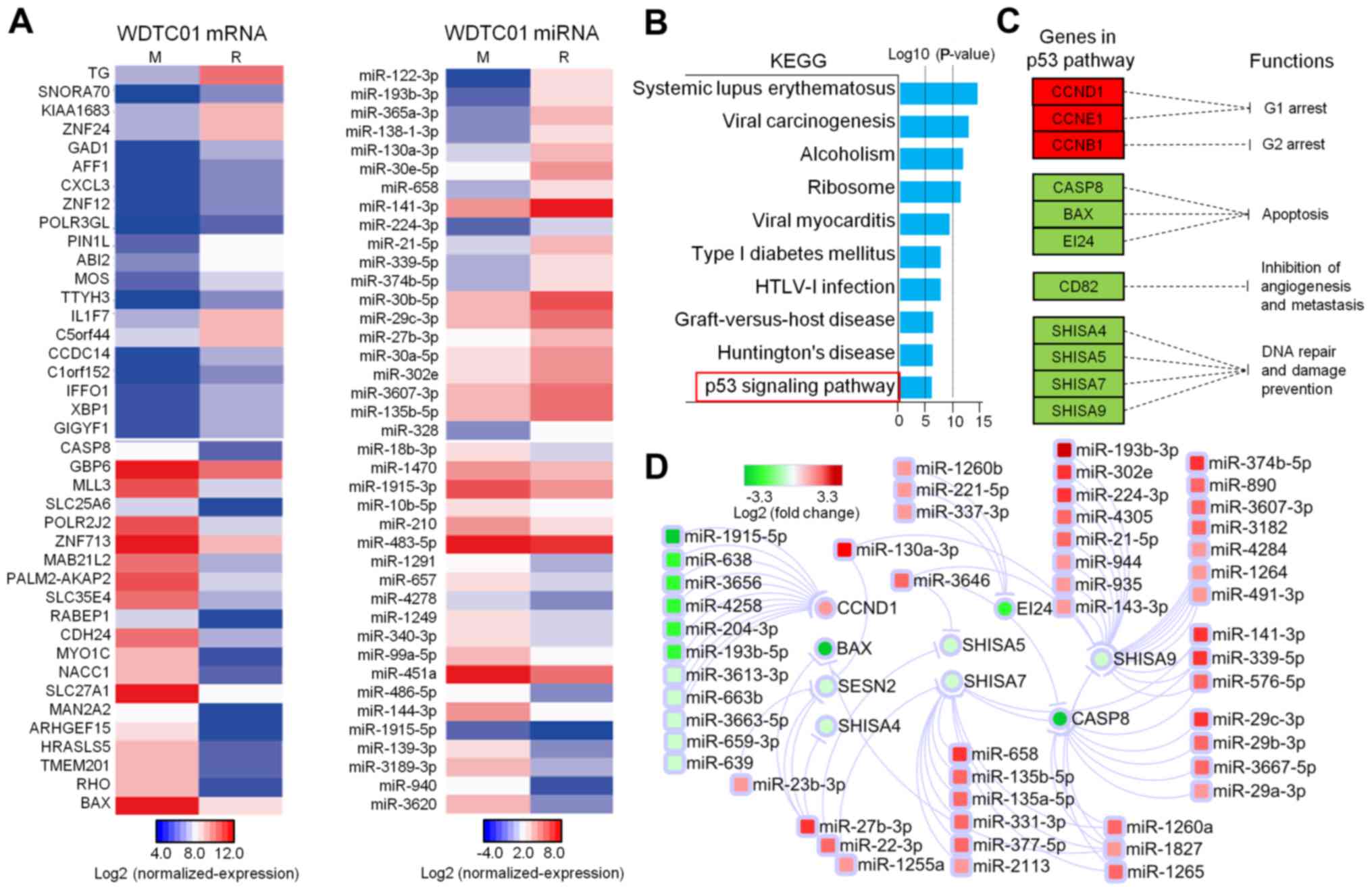

Regained TG expression and impaired

p53 downstream in recurrent lesions

To understand the underlying molecular mechanisms

for recurrence following three 131I treatments, we

compared recurrence and metastasis and revealed that there were 740

upregulation and 754 downregulated mRNAs and 88 upregulation and 60

downregulated miRNAs. TG was the most upregulated gene

(10-fold) in recurrent lesions. Pro-apoptotic genes BAX

(FC=23.6) and caspase-8 (FC=9.2) were among the top 20

downregulated genes (Fig. 5A).

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was applied to

1,494 DEmRNAs and the p53 signaling pathway was of interest

(Fig. 5B). Downregulation of BCL2

associated X, apoptosis regulator (BAX) and caspase-8

(CASP8) and upregulation of cyclin B1 (CCB1), D1

(CCD1) and E1 (CCE1) indicated attenuated downstream

effects of the p53 pathway, such as cell cycle arrest and apoptosis

(Fig. 5C). MiRNA-mRNA interaction

analysis revealed potential DEmiRNAs in recurrent lesions, which

regulated these mRNAs downstream of the p53 pathway. Among

apoptotic-inducing genes, BAX and CASP8 were targeted

by several miRNAs, and miR-1827 interacted with BAX and

CASP8; EI24 was targeted by miR-211-5p, a well-known

oncogene in WDTC (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

Despite increasing WDTC globally, few studies have

investigated metastatic sites of WDTC from a genomic perspective.

RNA-Seq analysis of metastatic sites, including two LNM and one

pleural metastasis from a single patient, revealed intratumor

heterogeneity and clonal evolution (32). Another miRNA study analyzed miRNA

transcriptomes of PTC with four LNM and noted that downregulation

of miRNAs was a common feature in PTC tumorigenesis (33). However, there has been no study to

investigate the underlying mechanisms of recurrent WDTC using

recurrent lesions and genomic profiling due to the difficulty of

collecting tissue. We used one paired bone metastatic and one

paired recurrent metastatic lesion and performed mRNA and miRNA

microarray analysis. Integrated with TCGA data, we found common

prognostic factors as key expression changes related to metastasis

and distinct features of LMN and BM. We also suggested a pattern

for recurrence from a genomic perspective, and we provided evidence

for future prevention and therapy for metastasis and relapse of

WDTC.

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition is a

well-established model explaining thyroid cancer development

(34). TG is thought to be a

differentiation marker for WDTC (35), and lower TG expression was

revealed to be correlated with thyroid cancer cell stemness

(34). For WDTC01, TG

expression gradually decreased in normal tissue to metastatic stage

tissue (Fig. 4D). This may be

explained by the fact that tumor cells with lower TG

expression migrating from the primary tumor are prone to BM, which

is supported by the fact that poorly differentiated thyroid cancer

has more DM (36). Additionally,

significant repression of TG was absent in 8 LNM from TCGA,

indicating that TG suppression is specifically related to BM

and not LNM. Next, the microenvironment of the vertebrae may induce

an adaptive response to suppress expression of TG. According

to the miRNA-mRNA analysis, TG may be suppressed by aberrant

upregulation of miR-3202 and miR-204-3p (Fig. 4D). Along with TG, the

pro-apoptotic BBC3 gene was gradually downregulated during

lineage dedifferentiation. The putative miRNA-mRNA network revealed

that continuously increasing expression of miR-622, miR-144-3p,

miR-30b-3p, miR-711 and miR-665 may be the trigger of dysregulation

of BBC3.

High expression of ALPL and low expression of

miR-486-5p were related to a prognosis of WDTC, and these markers

were associated with cancer cell stemness. High expression of

ALPL, as a pluripotent stem cell marker (37), has been revealed to be associated

with poor OS for glioblastoma and prostate cancers (38,39).

For lung and prostate cancer, downregulation of miR-486-5p was

reported to be associated with poor survival (40–42).

Cellular function data revealed that loss of miR-486-5p

dedifferentiated cancer cells via epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(42).

To find the common molecules related to BM and LNM

in WDTC, we overlapped expression changes in both and among the 19

overlapped DEmRNAs, and CXCR4 was key to the

CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway, a critical and well-studied pathway in

BM (43). CXCR4 was reported

to be significantly upregulated and related to BRAF mutations and

neoplastic infiltration, resulting in more aggressive WDTC

(44). Another two molecules

involved in WDTC progression were also related to cancer cell

stemness. As reported in ovarian carcinoma (45), MUC4 can induce

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and it can enhance the invasion

of tumors in pancreatic and breast cancers (46,47).

miR-30a-5p, the only overlapped miRNA in metastatic lesions, is

reported to be associated with cancer metastasis. The loss of

miR-30a-5p can lead to invasion and migration of breast cancer

(48) and colorectal cancer cells

(49) and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (50).

In addition, BM and LNM had distinct features with

respect to enrichment analysis. Notably, all KEGG and GO terms of

BM for WDTC01 were associated with ribosomal activity, and all

genes enriched in this pathway were upregulated, indicating that

efficient ribosome translational machineries contribute to BM in

WDCT01. Although individual ribosomal proteins, such as

RPL17 and RPS27L, were reported to be tumor

suppressors, ribosome biogenesis and translation were directly

associated with increased cell growth and proliferation (51). In contrast, no sign of overturned

ribosomal activity was observed in the 8 LNM, perhaps due to the

different microenvironment between BM and LNM.

The most common reason for WDTC recurrence was due

to poor uptake of 131I in the poorly differentiated

variant of WDTC. For WDTC01, gradually decreased expression of TG

indicated a more dedifferentiated type of WDTC, so inefficient

uptake was considered to contribute to cancer relapse (52). However, following 131I

treatments, expression differed greatly from former metastatic

lesions, indicating heterogeneity of the recurrent lesion.

Well-differentiated neoplasms arise from residual cancer stem cells

(CSCs) following surgical debulking. TG expression was again

recovered to its pre-metastatic state because CSCs give rise to

differentiated progeny (53).

According to enrichment analysis, several critical genes of the p53

pathway were altered, and apoptotic resistance and a promoted cell

cycle should increase proliferation of the recurrent lesion.

In summary, we offered an integrated analysis of

mRNAs and miRNAs involved in the metastasis, progression and

recurrence of WDTC and identified numerous mRNA and miRNA related

to stemness, which contributed to the malignancy and recurrence of

WDTC. The ribosome pathway was hyper-activated in BM, and the p53

pathway was correlated with relapse in our case. This information

may provide useful regulatory targets and pathways for future

development of predictive tools and therapies of WDTC.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study subject for his participation. We

appreciate the experimental support of the Central Laboratory for

Medical Research, Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital.

Funding

The present study was supported partly by grants

from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81472202,

81772932, 81201535, 81302065, 81301993, 81472501, 81372175,

81472209 and 81702243), The Fundamental Research Funds For the

Central Universities (22120170212 and 22120170117), The Shanghai

Natural Science Foundation (12ZR1436000 and 16ZR1428900) and the

Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning

(201440398 and 201540228). The funder has no role in the study

design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or

preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are

available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

YJZ, YSM, QX, DF and XFW designed the study. YJZ,

YSM, QX, FY, ZWL, CYJ, DF and XFW performed the experiments. YJZ,

YSM, DF and XFW performed the statistical analyses and interpreted

the data. QX, FY, ZWL, CYJ, GXL, XQY and XFW are involved in the

patient recruitment. FY, ZWL, CYJ, XXJ, LZ, YCS, WTX, GXL, XQY, PZ,

DF and XFW contributed to the study materials and consumables. YJZ,

YSM, DF and XFW wrote the manuscript. YJZ, YSM and QX contributed

equally to this work. All authors read and approved the manuscript

and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in

ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are

appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board and Ethics Committee of The Shanghai Tenth People's

Hospital, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

(SHSY-IEC-KY-4.0/17-13/01).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kilfoy BA, Zheng T, Holford TR, Han X,

Ward MH, Sjodin A, Zhang Y, Bai Y, Zhu C, Guo GL, et al:

International patterns and trends in thyroid cancer incidence,

1973–2002. Cancer Causes Control. 20:525–531. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chen AY, Jemal A and Ward EM: Increasing

incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer in the United States,

1988–2005. Cancer. 115:3801–3807. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sherman SI: Thyroid carcinoma. Lancet.

361:501–511. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Xing M, Haugen BR and Schlumberger M:

Progress in molecular-based management of differentiated thyroid

cancer. Lancet. 381:1058–1069. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kimura ET, Nikiforova MN, Zhu Z, Knauf JA,

Nikiforov YE and Fagin JA: High prevalence of BRAF mutations in

thyroid cancer: Genetic evidence for constitutive activation of the

RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF signaling pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Cancer Res. 63:1454–1457. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cohen Y, Xing M, Mambo E, Guo Z, Wu G,

Trink B, Beller U, Westra WH, Ladenson PW and Sidransky D: BRAF

mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst.

95:625–627. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ciampi R, Knauf JA, Kerler R, Gandhi M,

Zhu Z, Nikiforova MN, Rabes HM, Fagin JA and Nikiforov YE:

Oncogenic AKAP9-BRAF fusion is a novel mechanism of MAPK pathway

activation in thyroid cancer. J Clin Invest. 115:94–101. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wreesmann VB, Sieczka EM, Socci ND, Hezel

M, Belbin TJ, Childs G, Patel SG, Patel KN, Tallini G, Prystowsky

M, et al: Genome-wide profiling of papillary thyroid cancer

identifies MUC1 as an independent prognostic marker. Cancer Res.

64:3780–3789. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Moon S, Song YS, Kim YA, Lim JA, Cho SW,

Moon JH, Hahn S, Park DJ and Park YJ: Effects of coexistent

BRAFV600E and TERT promoter mutations on poor clinical

outcomes in papillary thyroid cancer: A meta-analysis. Thyroid.

27:651–660. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lee JJ, Wang TY, Liu CL, Chien MN, Chen

MJ, Hsu YC, Leung CH and Cheng SP: Dipeptidyl peptidase IV as a

prognostic marker and therapeutic target in papillary thyroid

carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 102:2930–2940. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chowdhury S, Veyhl J, Jessa F, Polyakova

O, Alenzi A, MacMillan C, Ralhan R and Walfish PG: Programmed

death-ligand 1 overexpression is a prognostic marker for aggressive

papillary thyroid cancer and its variants. Oncotarget.

7:32318–32328. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Samaan NA, Schultz PN, Hickey RC, Goepfert

H, Haynie TP, Johnston DA and Ordonez NG: The results of various

modalities of treatment of well differentiated thyroid carcinomas:

A retrospective review of 1599 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

75:714–720. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Schlumberger MJ: Papillary and follicular

thyroid carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 338:297–306. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, Leboulleux

S, Hartl D, Travagli JP, Caillou B, Ricard M, Lumbroso JD, De

Vathaire F, et al: Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant

metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma:

Benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 91:2892–2899. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Haugen BR: 2015 American Thyroid

Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid

nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: What is new and what has

changed? Cancer. 123:372–381. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

O'Neill CJ, Oucharek J, Learoyd D and

Sidhu SB: Standard and emerging therapies for metastatic

differentiated thyroid cancer. Oncologist. 15:146–156. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Mazzaferri EL and Kloos RT: Clinical

review 128: Current approaches to primary therapy for papillary and

follicular thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 86:1447–1463.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mazzaferri EL and Jhiang SM:

Differentiated thyroid cancer long-term impact of initial therapy.

Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 106(151–168): discussion 168–170.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Visone R, Russo L, Pallante P, De Martino

I, Ferraro A, Leone V, Borbone E, Petrocca F, Alder H, Croce CM and

Fusco A: MicroRNAs (miR)-221 and miR-222, both overexpressed in

human thyroid papillary carcinomas, regulate p27Kip1 protein levels

and cell cycle. Endocr Relat Cancer. 14:791–798. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mancikova V, Castelblanco E, Pineiro-Yanez

E, Perales-Paton J, de Cubas AA, Inglada-Perez L, Matias-Guiu X,

Capel I, Bella M, Lerma E, et al: MicroRNA deep-sequencing reveals

master regulators of follicular and papillary thyroid tumors. Mod

Pathol. 28:748–757. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network:

Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Cell. 159:676–690. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhao M, Wang KJ, Tan Z, Zheng CM, Liang Z

and Zhao JQ: Identification of potential therapeutic targets for

papillary thyroid carcinoma by bioinformatics analysis. Oncol Lett.

11:51–58. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Geraldo MV and Kimura ET: Integrated

analysis of thyroid cancer public datasets reveals role of

post-transcriptional regulation on tumor progression by targeting

of immune system mediators. PLoS One. 10:e01417262015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dweep H and Gretz N: miRWalk2.0: A

comprehensive atlas of microRNA-target interactions. Nat Methods.

12:6972015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS and

Sander C: The microRNA.org resource: Targets and expression.

Nucleic Acids Res. 36:D149–D153. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW and Bartel DP:

Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs.

Elife. 4:e050052015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi

M and Tanabe M: KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein

annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:D457–D462. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein

D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT,

et al: Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene

ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 25:25–29. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

da Huang W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using david

bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 4:44–57. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: Limma powers differential expression analyses

for rna-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Benjamini Y and Hochberg Y: Controlling

the false discovery rate-a practical and powerful approach to

multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B-Methodol. 57:289–300.

1995.

|

|

32

|

Le Pennec S, Konopka T, Gacquer D,

Fimereli D, Tarabichi M, Tomas G, Savagner F, Decaussin-Petrucci M,

Tresallet C, Andry G, et al: Intratumor heterogeneity and clonal

evolution in an aggressive papillary thyroid cancer and matched

metastases. Endocr Relat Cancer. 22:205–216. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Saiselet M, Gacquer D, Spinette A, Craciun

L, Decaussin-Petrucci M, Andry G, Detours V and Maenhaut C: New

global analysis of the microRNA transcriptome of primary tumors and

lymph node metastases of papillary thyroid cancer. BMC Genomics.

16:8282015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lin RY: Thyroid cancer stem cells. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 7:609–616. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Takano T, Miyauchi A, Yokozawa T,

Matsuzuka F, Maeda I, Kuma K and Amino N: Preoperative diagnosis of

thyroid papillary and anaplastic carcinomas by real-time

quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction of

oncofetal fibronectin messenger RNA. Cancer Res. 59:4542–4545.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Are C and Shaha AR: Anaplastic thyroid

carcinoma: Biology, pathogenesis, prognostic factors, and treatment

approaches. Ann Surg Oncol. 13:453–464. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hou Z, Meyer S, Propson NE, Nie J, Jiang

P, Stewart R and Thomson JA: Characterization and target

identification of a DNA aptamer that labels pluripotent stem cells.

Cell Res. 25:390–393. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Rao SR, Snaith AE, Marino D, Cheng X, Lwin

ST, Orriss IR, Hamdy FC and Edwards CM: Tumour-derived alkaline

phosphatase regulates tumour growth, epithelial plasticity and

disease-free survival in metastatic prostate cancer. Br J Cancer.

116:227–236. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Iwadate Y, Suganami A, Tamura Y, Matsutani

T, Hirono S, Shinozaki N, Hiwasa T, Takiguchi M and Saeki N: The

pluripotent stem-cell marker alkaline phosphatase is highly

expressed in refractory glioblastoma with DNA hypomethylation.

Neurosurgery. 80:248–256. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Vosa U, Vooder T, Kolde R, Vilo J,

Metspalu A and Annilo T: Meta-analysis of microRNA expression in

lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 132:2884–2893. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tan X, Qin W, Zhang L, Hang J, Li B, Zhang

C, Wan J, Zhou F, Shao K, Sun Y, et al: A 5-microRNA signature for

lung squamous cell carcinoma diagnosis and hsa-miR-31 for

prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 17:6802–6811. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang X, Zhang T, Yang K, Zhang M and Wang

K: miR-486-5p suppresses prostate cancer metastasis by targeting

Snail and regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Onco

Targets Ther. 9:6909–6914. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Burton A: Regulation of RANKL might reduce

bone metastases. Lancet Oncol. 7:3672006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Torregrossa L, Giannini R, Borrelli N,

Sensi E, Melillo RM, Leocata P, Materazzi G, Miccoli P, Santoro M

and Basolo F: Cxcr4 expression correlates with the degree of tumor

infiltration and braf status in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Mod

Pathol. 25:46–55. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ponnusamy MP, Lakshmanan I, Jain M, Das S,

Chakraborty S, Dey P and Batra SK: Muc4 mucin-induced epithelial to

mesenchymal transition: A novel mechanism for metastasis of human

ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 29:5741–5754. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Singh AP, Moniaux N, Chauhan SC, Meza JL

and Batra SK: Inhibition of muc4 expression suppresses pancreatic

tumor cell growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 64:622–630. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Rowson-Hodel AR, Wald JH, Hatakeyama J,

O'Neal WK, Stonebraker JR, VanderVorst K, Saldana MJ, Borowsky AD,

Sweeney C and Carraway KL III: Membrane mucin muc4 promotes blood

cell association with tumor cells and mediates efficient metastasis

in a mouse model of breast cancer. Oncogene. 37:197–207. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Li W, Liu C, Zhao C, Zhai L and Lv S:

Downregulation of β3 integrin by miR-30a-5p modulates cell adhesion

and invasion by interrupting Erk/Ets-1 network in triple-negative

breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 48:1155–1164. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wei W, Yang Y, Cai J, Cui K, Li RX, Wang

H, Shang X and Wei D: miR-30a-5p suppresses tumor metastasis of

human colorectal cancer by targeting ITGB3. Cell Physiol Biochem.

39:1165–1176. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chung YH, Li SC, Kao YH, Luo HL, Cheng YT,

Lin PR, Tai MH and Chiang PH: miR-30a-5p inhibits

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and upregulates expression of

tight junction protein claudin-5 in human upper tract urothelial

carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 18:E18262017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ruggero D and Pandolfi PP: Does the

ribosome translate cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 3:179–192. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ma ZF and Skeaff SA: Thyroglobulin as a

biomarker of iodine deficiency: A review. Thyroid. 24:1195–1209.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Vermeulen L, Sprick MR, Kemper K, Stassi G

and Medema JP: Cancer stem cells-old concepts, new insights. Cell

Death Differ. 15:947–958. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|