Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has become a worldwide

public health problem with a high incidence and mortality (1). By 2030, an extra 2.2 million new cases

of CRC and 1.1 million cancer-related deaths are expected,

representing a 60% increased burden of CRC.

The early symptoms of CRC are not obvious. Notably,

>85% of patients with CRC are diagnosed at an advanced stage.

However, when the optimal treatment window is missed, the survival

time and quality of life for patients with advanced CRC are

significantly reduced, resulting in a 5-year survival rate of

<40% (2). By contrast, the

5-year survival rate of patients with CRC with early-stage disease

after treatment is as high as 95%.

The prognosis of patients with CRC largely depends

on the stage of the disease at first diagnosis. In most cases, CRC

cases are sporadic and transform from adenomas (3), and the transition from adenoma to CRC

typically spans several years. Detecting and removing adenomas at

an early stage can effectively impede their progression to CRC,

thus reducing the incidence of the disease (4,5).

Moreover, accurate, evidence-based screening could significantly

decrease the morbidity and mortality of CRC. Furthermore, early

screening can improve the clinical outcomes of patients, avoid

treatment delays, and reduce CRC mortality (6).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

strongly advocates for CRC screening for precise diagnosis

(7). Among the available methods,

colonoscopy stands out as the primary screening approach due to its

widespread use and high accuracy. In addition, the USPSTF

recommends that colonoscopy be performed promptly, as colonoscopy

can significantly reduce the incidence and mortality of CRC

(8). However, it is imperative to

acknowledge that colonoscopy does have certain limitations. One

such limitation is the reliance on the skill level of the

endoscopic physicians for diagnostic accuracy, which can vary among

practitioners. Ensuring that each patient undergoes an examination

by a highly skilled endoscopist can be challenging.

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the ability

of machines to imitate human cognitive functions and perform tasks

at or above the human level using a clever combination of computer

science, algorithms, machine learning (ML), and data science. In

recent years, advances in AI have permeated medicine, rapidly

changing the way cancer research is conducted. Research has shown

that AI-aided colonoscopy can enhance screening accuracy,

efficiency, and quality (9). The

availability of high-dimensional datasets, continuous advances in

high-performance computing power, and innovative deep-learning

architectures have all led to a rapidly emerging role for AI in CRC

screening.

The combination of AI technology and colonoscopy

holds great promise for controlling the morbidity and mortality of

CRC. Therefore, the aim of the present review was to examine the

advantages and limitations of colonoscopy while focusing on the

application of AI-aided colonoscopy, providing a theoretical

foundation for developing precise CRC screening.

Premalignant lesions of CRC and screening

modalities

Colorectal polyps are protrusions occurring in the

colorectal lumen, which can be divided into neoplastic and

non-neoplastic polyps (Table I).

Pathologically, neoplastic polyps can be classified as adenomatous

and serrated polyps, and non-neoplastic polyps include

inflammatory-associated polyps, hamartomatous polyps and

hyperplastic polyps (10,11). Adenomatous polyps include three

histological types: Tubular, tubulovillous, and villous (11). Conversely, serrated class lesions

are a heterogeneous group of lesions that can be further classified

into three categories: Hyperplastic polyps (HPs), sessile serrated

lesions (SSPs), and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) (Table I). The carcinogenesis process of CRC

involves four pathways: Adenoma-carcinoma, serrated neoplastic,

inflammatory, and de novo (12,13).

The first two pathways account for the vast majority of cases and

arise from colorectal polyps. The conventional adenoma-carcinoma

pathway leads to 70% of sporadic CRC cases (14), whereas the serrated neoplastic

pathway accounts for 15–30% of CRC cases.

| Table I.Colorectal polyps. |

Table I.

Colorectal polyps.

| Neoplastic

polyps | Adenomatous

polyps | Tubular

adenoma |

|

|

| Tubulovillous

adenoma |

|

|

| Villous

adenoma |

|

| Serrated class

lesions | Hyperplastic

polyp |

|

|

| Sessile serrated

lesions |

|

|

| Traditional

serrated adenomas |

| Non-neoplastic

polyps |

Inflammatory-associated polyps | Inflammatory

polyps |

|

|

| Lymphoid

polyps |

|

|

| Schistosoma

polyps |

|

| Hamartomatous

polyp | Juvenile

polyps |

|

|

| Peutz-Jeghers

polyps |

|

|

| Cowden

syndrome-associated polyps |

|

|

| Canada-Cronkhite

syndrome-associated polyps |

|

| Hyperplastic

polyps | N/A |

High-sensitivity Guaiac fecal occult blood test,

fecal immunochemical test, multi-target fecal DNA, computed

tomography colonography (CTC), colonoscopy, and other methods are

currently the CRC screening methods recommended by the USPSTF

(7,8,15). The

diagnostic accuracy and effectiveness of visual screening (CTC,

flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy) are far higher than those

of stool-based screening due to their ability to directly observe

lesions (6,16–25).

Compared to stool-based CRC screening, a colonoscopy may have lower

in-patient compliance and frequency, yet it remains significantly

more accurate in detecting colorectal lesions (26). This procedure allows for direct

detection, biopsy, and removal of polyps during visual assessment

of the entire colon. Colonoscopy has several benefits, including

high sensitivity and specificity, and enables direct biopsy or

excision of suspected polyps. As a result, the USPSTF has indicated

that colonoscopy has the highest validity and popularity among CRC

screening methods (8).

Colonoscopy in CRC screening

Colonoscopy is the most reliable form of CRC

screening. According to a large, prospective observational study

that included nearly 89,000 nurses and other health professionals,

the CRC mortality rate was lower in people who self-reported at

least one screening colonoscopy than in those who had never

undergone a colonoscopy (27).

Furthermore, the USPSTF included four studies (n=4,821) evaluating

the accuracy of colonoscopy in 2021, demonstrating that for

adenomas ≥10 mm, colonoscopy had a sensitivity of 89–95% and a

specificity of 89%. Additionally, for adenomas ≥6 mm, colonoscopy

had a sensitivity of 75–93% and a specificity of 94% (8). These results further support the high

accuracy and specificity of colonoscopy.

Although colonoscopy is considered the ‘gold

standard’ screening test, it does have its limitations (28). The challenge of endoscopic

procedures lies in the real-time interpretation of endoscopic

imagery, which is complex and sensitive to human error.

Consequently, subtle, and early premalignant lesions in the colon

and rectum can easily be missed by endoscopists. A systematic

review (29) showed that the rate

of missed adenomas on colonoscopy was 26%, and this was 9% for

advanced adenomas and up to 27% for serrated polyps. A prospective

study of individuals who underwent screening colonoscopy within a

National Colorectal Cancer Screening Program associated an

increased adenoma detection rate (ADR) with a reduced risk of

post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer death.

Notably, ADRs are negatively associated with CRC incidence, with

each 1% increase in ADR associated with a 3–6% reduction in the

risk of colorectal cancer (30). By

contrast, a higher rate of missed adenoma detection inevitably

increases the risk of colorectal cancer.

It is important to acknowledge that colonoscopy does

not always detect colorectal cancer, and some patients may develop

CRC even after receiving a negative examination result. When this

occurs before the next recommended screening or surveillance

examination, it is called interval cancer. However, the term

‘interval cancer’ is considered too restrictive to encompass all

aspects necessary for colonoscopy quality assurance purposes. To

address this, Rabeneck and Paszat introduced the term

‘post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer’ (PCCRC) in 2010 (31), defined as colorectal cancer not

detected by screening or surveillance examinations and occurring

before the recommended next examination date (32).

Colonoscopy, despite being a valuable screening

tool, is not infallible and can potentially miss early or advanced

non-characteristic lesions, leading to the risk of PCCRC (32). Studies have indicated a prevalence

of PCCRC ranging from 3.7 to 8.6% following colonoscopy screening

(33,34). However, failure to detect colorectal

neoplasia remains the most relevant cause of PCCRC (35). It can be observed from research that

an improvement in the ADR during screening colonoscopy, achieved

through a comprehensive quality assurance program, translates into

reduced risks of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer. Specifically,

an ADR of a suboptimal endoscopist has been associated with a

substantial increase in the risk of post-colonoscopy colorectal

cancer incidence, whereas an ADR increase was effective in

reversing this detrimental effect (36). Undoubtedly, high-quality colonoscopy

will improve the diagnostic accuracy of adenoma and CRC lesions,

which is crucial for re-sectioning precancerous lesions and

preventing CRC (37).

AI has the potential to identify colorectal polyps

or CRC lesions that have gone undetected due to perceptual errors.

A multicenter and multi-county randomized crossover trial showed

that AI resulted in an ~50% reduction in the miss rate of

colorectal neoplasia. This finding highlights the potential of AI

in mitigating perceptual errors associated with small and subtle

lesions during standard colonoscopy (38). Consequently, combining colonoscopy

and AI may be a potential future development direction.

Artificial intelligence applications in

colonoscopy screening

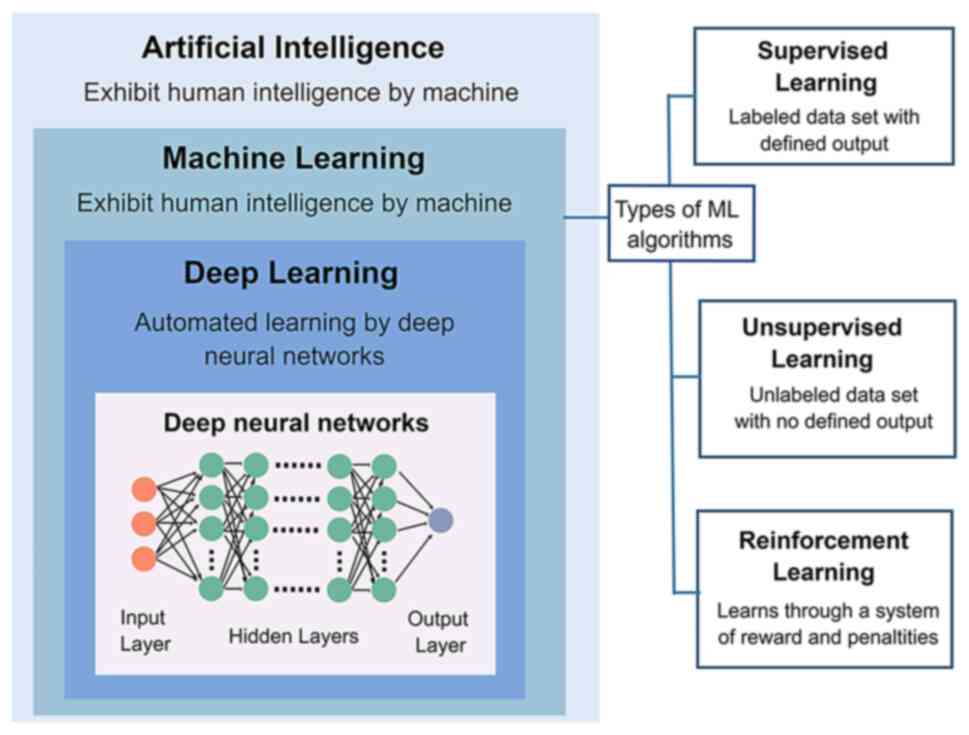

AI is a generic term broadly referring to utilizing

computers to model intelligent behavior with minimal human

intervention (39). ML is a

subfield of AI that is capable of analyzing data through algorithms

to take particular actions in response to specific inputs and

improve (‘learn’) themselves as more data becomes available, i.e.,

‘train’ (40). Supervised,

unsupervised, and reinforcement learning are three machine-learning

algorithm categories. Deep learning (DL) is an essential subfield

of ML that ‘learns’ from large data sets of raw images, leading to

higher accuracy and faster processing speeds when performing image

recognition, as this process does not require ‘instructions’ to

find specific image features (Fig.

1). Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a classical branch of

DL, are frequently employed in medical image analysis (41). Thus far, these methods have

gradually penetrated the medical field with substantial success

(42).

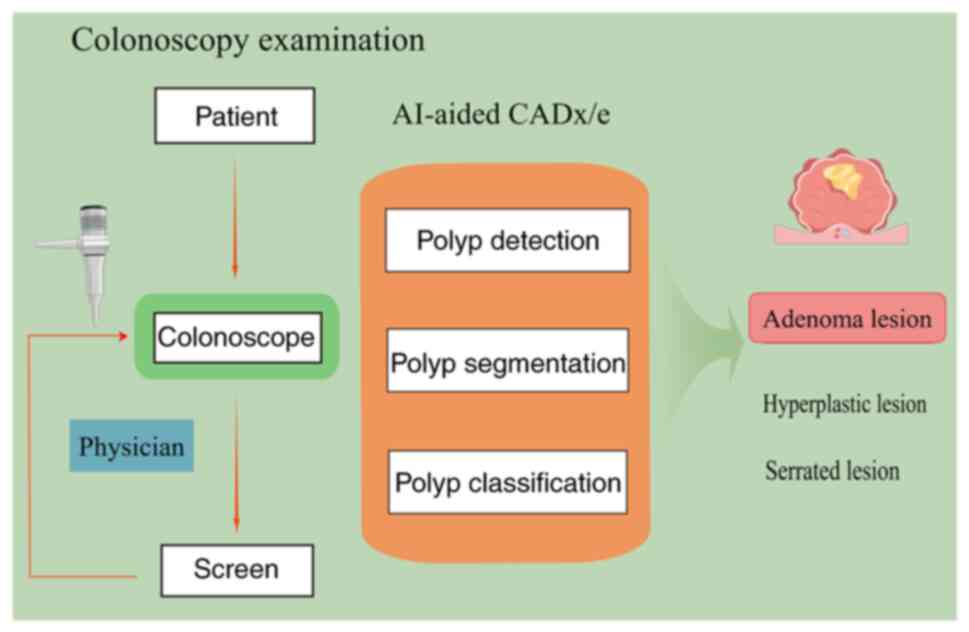

Numerous studies combining clinical and DL have

emerged in oncology screening in recent years. These studies have

utilized detection images and videos of colonoscopies or

pathological images of tumor tissues as input data to train models

with the help of ML (43). The aim

was to assist in the diagnosis and efficacy determination of

clinical tumors with the assistance of models to achieve efficient

precision medicine (Fig. 2)

(44). The combination of

colonoscopy and AI has also been realized using computer

algorithms.

Colonoscopy has established itself as the preferred

diagnostic modality for CRC due to its promising clinical results

and wide range. Unfortunately, due to challenges such as

inter-observer variability in lesion detection, time-consuming

biopsy protocols, and biopsy sampling errors (45), a substantial fluctuation in the ADR

remains present (7–53%) (46), and

the adenoma miss rate may be as high as 26% (29). Numerous studies have indicated that

endoscopists may achieve improved discrimination between

premalignant lesions and hyperplastic polyps through a combination

of AI and colonoscopy. The integration of both has contributed to

an elevated ADR (9) and markedly

reduced CRC morbidity and mortality (47–50).

Therefore, this review focuses on AI-aided colonoscopy, the most

promising and efficient CRC screening method in clinical

settings.

Computer-aided detection (CADe)

model

The concept of a CADe model was established in 2003

(51). This system supports the

diagnosis of CRC and detection of premalignant polyps by processing

endoscopic images or video frame sequences obtained during

colonoscopy (52–58) (Table

II). Karkanis et al (52) designed a CADe model based on color

and texture analysis of the intestinal mucosal surface. This model

had excellent sensitivity up to 99.3±0.3%, and specificity up to

93.6±0.8% in detecting abnormal colon regions associated with

adenomas. However, the CADe model identifies polyps based on static

colonoscopy images rather than real-time analysis of each image

frame in the colonoscopy video, limiting its clinical practicality.

To address this, AI models for automatically detecting polyps using

a series of different imaging feature quantities (such as edge

detection, texture analysis, and energy mapping) have been under

investigation (52). Nevertheless,

none of these methods have achieved a reliable detection rate of

≥90%, and real-time diagnosis has been hindered by computational

power limitations (59). It was not

until the advent of neural networks (NNs) that significant

improvements in this situation began to unfold.

| Table II.Summary of studies on colonoscopy

combined with CADe. |

Table II.

Summary of studies on colonoscopy

combined with CADe.

| Authors, year | Study design | CADe model | Image type | Conclusion | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Karkanis et

al, 2003 | Retrospective

study | CADe model for

color and texture analysis of mucosal surfaces based on CWC

features | Static images | Sensitivity,

99.3±0.3% | (52) |

| Misawa et

al, 2018 | Retrospective

study | CNN-based CADe

model | Colonoscopy

video | Sensitivity,

90.0% | (53) |

| Urban et al,

2018 | Retrospective

study | CNN-based CADe

model | Colonoscopy

video | Sensitivity,

93.0% | (58) |

| Yamada et

al, 2019 | Retrospective

study | DNN-based CADe

model | Colonoscopy

video | Sensitivity,

97.3% | (54) |

| Wang et al,

2019 | Unblinded

prospective randomized controlled trial | DL-based CADe

model | Colonoscopy

video | ADR in CADe group

vs. standard colonoscopy group: 29.1 vs. 20.3f | (55) |

| Wang et al,

2020 | Double-blind

prospective randomized | DL-based CADe

model | Colonoscopy

video | ADR in CADe group

vs. control group: 34.1 vs. 28% | (56) |

|

| controlled

trial | ENDOANGEL

system | Colonoscopy | ADR in

ENDOANGEL | (57) |

| Gong et al,

2020 | Single-blind

prospective randomized controlled trial | based on DNN and

perceptual hash algorithm | video | group vs. standard

colonoscopy group: 16.34 vs. 7.74% |

|

NN algorithms have emerged and been proven to detect

and localize polyps automatically (60), thus improving the accuracy and

sensitivity of the CADe model for diagnosing polyps and CRC

lesions. In 2018, Misawa et al (53) developed a convolutional 3D NN

algorithm based on the CADe model, reporting that the model had a

sensitivity of 90.0% and a specificity of 63.3% for screening

polyps. In 2019, Yamada et al (54) developed a CADe model based on deep

neural networks (DNNs) and validated it using 705 static images

containing cancerous lesions and 4,135 static images of normal

tissues from 752 patients with CRC. The results were highly

promising, with the CADe model exhibiting exceptional diagnostic

accuracy for CRC, with a sensitivity of 97.3% and a specificity of

99.0%.

Previous prospective studies focusing on the

real-time performance of CADe models have been limited. However, in

2019, Wang et al conducted the first prospective unblinded

randomized controlled trial to investigate the impact of DL-based

CADe models on the accuracy of colorectal screening for polyps and

adenomas (55). A statistically

significant increase in the ADR was observed with the aid of CADe

compared to colorectal screening alone (29.1 vs. 20.3%;

P<0.001). Furthermore, colonoscopy detected more diminutive

adenomas using the CADe model than using colonoscopy alone (185 vs.

102; P<0.001). However, the study was unable to control the

subjective bias of the operating physicians since they were not

blinded to the CADe system. This could have influenced their

vigilance or reliance on the CADe system, potentially

overestimating or underestimating its effectiveness. To address

this issue, Wang et al conducted a double-blind, randomized

controlled trial (56) in 2020,

using a ‘dummy system’ that completely mimicked the false alarm of

the AI system without suggesting true polyps. The operating

physicians were double-blinded, allowing for a more rigorous

assessment of the effectiveness of the CADe system in improving the

detection rate of colonic adenomas and polyps. This study

demonstrated a significant increase of 23.4% in the ADR, from 27.6

to 34.1%, and a considerable increase in polyp detection rate (PDR)

in the CADe group compared to the control group. The study also

confirmed that a high-performance, real-time CADe model could

effectively enhance the detection rate of adenomas and colorectal

polyps, which may contribute to a lower prevalence of CRC. In

addition, the present study revealed a marked improvement in the

number of hyperplastic polyps detected in the CADe group compared

with the control group (114 vs. 52; P<0.001). This finding may

contribute to clinically reducing unnecessary polyp removal, thus

avoiding additional treatment risks such as perforation and massive

bleeding (61).

Negligence by endoscopists is responsible for a

significant percentage (71–86%) of interstitial colorectal cancers

(7,62). One of the main contributing factors

to this negligence is the challenge faced by physicians in

maintaining a standardized withdrawal time during long procedures

under high work pressure. In order to address this issue, Gong

et al (57) developed a CADe

system based on DNNs and perceptual hashing algorithms. By

performing real-time monitoring of the withdrawal speed, recording

of the withdrawal time, and alerting when the colonoscope slips,

the system provided normative feedback to the endoscopist. However,

in contrast to other AI-assisted systems, this system does not

improve the ADR by automatically examining polyps; instead, its

primary objective is to enhance technical elements of the procedure

to achieve improvement. The results revealed that the CADe group

had a prolonged mean negative withdrawal time (6.38 vs. 4.76 min)

and an ~100% enhancement in the ADR (16.34 vs. 7.74%) compared to

the colonoscopy-only group. These findings surpass previous reports

and indicate the practicality of improving the PDR and ADR by

standardizing endoscopist practices through the implementation of

the CADe system.

An AI-aided polyp detection system has shown a

significant increase in the detection rate of lesions, and the

ability of AI to detect lesions is not significantly affected by

factors such as size, location, and shape (63). Real-time AI-aided colonoscopy has

the potential to improved ADR even for experienced endoscopists

(64). Therefore, high-quality

clinical data are urgently required to demonstrate the

effectiveness and accuracy of AI-assisted endoscopy.

Recently, a review highlighted the approval of the

first AI-guided polyp detection system by the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration (65). The GI

Genius™ (Medtronic, Ltd.) system is a CADe system that integrates

existing endoscopy systems and improves adenoma detection during

colonoscopy. However, while the system shows promise in improving

adenoma detection, it is essential to assess its actual impact on

colorectal cancer prevention through large-scale population-based

studies. A study called COLO-DETECT will be the first multi-center

randomized controlled trial evaluting the GI Genius™ in real-world

colonoscopy practice and will be unique in evaluating its clinical

and cost effectiveness (66). The

results will significantly impact the future adoption of this novel

technology.

Computer-aided diagnosis (CADx)

model

Recently, the European Society of Gastrointestinal

Endoscopy (ESGE) published an official position statement aiming to

define simple, safe, and easy-to-measure competence standards for

endoscopists and AI systems performing optical diagnosis of

diminutive colorectal polyps (67).

In this regard, CADx has shown great potential in improving the

accuracy of colorectal polyp characterization (61,68–74)

(Table III). CADx systems may

improve the accuracy of colorectal polyp optical diagnosis, leading

to a reduction in the unnecessary removal of hyperplastic polyps.

Moreover, CADx could help implement cost-saving strategies in

colonoscopy by reducing the burden of polypectomy and pathology. In

other words, its application facilitates the implementation of

resect-and-discard (when polyps are resected and discarded without

histological evaluation) and ‘leave-in-situ’ (when non-neoplastic

lesions located in the rectum and sigmoid are left in situ

without resection, as they have no malignant potential) strategies

(75,76). Furthermore, the study conducted by

Hassan et al confirmed that a real-time CADx system has the

potential to reduce all polypectomies and related costs by 44.4% in

the study population (77),

highlighting the significant cost-saving benefits of this

technology.

| Table III.Summary of studies on colonoscopy

combined with CADx. |

Table III.

Summary of studies on colonoscopy

combined with CADx.

| Authors, year | Study design | Research

objectives | Imaging

modality | CADx model | CADx model

performance | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Tischendorf et

al, 2010 | Prospective pilot

study | Differentiation of

neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps | Magnifying NBI | SVM-based CADx | CADx: Sensitivity,

90%; Specificity, 70%; Accuracy, 85.3% | (71) |

| Gross et al,

2011 | Prospective

study | Differentiation

between neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps (≤10

mm) | Magnifying NBI | SVM-based CADx | -CADx group:

Sensitivity, 93.4%; Specificity, 91.8%; Accuracy; 92.7% -Expert

panel: Sensitivity, 93.8%; Specificity, 85.7%; Accuracy, 91.9%

-Non-expert group: Sensitivity, 86%; Specificity, 87.8%; Accuracy,

86.8% | (72) |

| Aihara et

al, 2013 | Prospective

study | Differentiation of

neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps | AFI | CADx based on AFE

numerical olor analysis | Sensitivity, 83.3%;

Specificity, 70.1%; PPV, 78.4%; NPV, 82.6% | (70) |

| Mori et al,

2018 | Prospective

study | Differentiation of

small (≤5 mm) neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps | Magnifying NBI | SVM-based CADx | Sensitivity, 92.7%;

Specificity, 89.8%; PPV, 93.7%; NPV, 88.3% | (73) |

| Chen et al,

2018 | Prospective

study | Differentiation of

small (≤5 mm) neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps | Magnifying NBI | DL-based CADx | Sensitivity, 96.3%;

Specificity, 78.1%; Accuracy, 90.1%; PPV, 89.6%; NPV, 91.5% | (61) |

| Min et al,

2019 | Prospective

study | Differentiation of

adenomatous and non-adenomatous polyps | LCI | GMM-based CADx | Sensitivity, 83.3%;

Specificity, 70.1%; Accuracy, 78.4%; PPV, 82.6%; NPV, 71.2% | (69) |

| Byrne et al,

2019 | Retrospective

study | Differentiation of

small (≤5 mm) neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps | Magnifying NBI | DCNN-based

CADx | Sensitivity, 98%;

Specificity, 83%; Accuracy, 94%; PPV, 90%; NPV, 97% | (68) |

In contrast to CADe, in which only observation under

normal white light is possible, CADx is available not only with

white-light endoscopy (77,78) but also in combination with a variety

of other optical imaging techniques, including magnifying

narrow-band imaging (NBI) (68),

linked-color imaging (LCI) (69),

blue-light imaging (BLI) (79), and

autofluorescence imaging (AFI) (70). Among these, studies on CADx and NBI

are the most extensive. As an advanced endoscopic imaging method,

NBI provides excellent visualization, can evaluate mucosal surfaces

and microvascular structures, and is an excellent tool that can

differentiate between neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions

(80). In 2010, Tischendorf et

al (71) developed a CADx model

that applied NBI and was capable of aiding the classification of

colorectal polyps based on three vascular structural features: Mean

vessel length, vessel circumference, and mean brightness as

observed using NBI. However, the diagnostic accuracy of this model

(85.3%) was markedly lower than that of endoscopic experts and

barely meets the clinical needs of experts. In 2011, Gross et

al (72) developed a CADx model

to assist in classifying colorectal polyps through the analytical

categorization of nine vessel characteristics (e.g., circumference

and brightness). With this model, the sensitivity, specificity, and

accuracy were 95, 90.3 and 93.1%, respectively. In addition, the

diagnostic performance of this model was comparable to that of an

endoscopic expert panel (93.4, 91.8 and 92.7% for sensitivity,

specificity, and accuracy, respectively) and significantly better

than that of a non-expert panel (86, 87.8 and 86.8% for

sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, respectively). However,

these models lacked real-time diagnostic capabilities, highlighting

the importance of incorporating real-time diagnosis into CADx

technology for its practical application in clinical settings.

By constructing the CADx algorithm using real-time

decision outputs from a support vector machine (SVM), the CADx

algorithm has made significant progress in achieving real-time

diagnosis capabilities (81–83).

In 2018, Mori et al (73)

provided further evidence supporting the use of an SVM-based CADx

model for real-time assisted diagnosis in the NBI mode of

diminutive colorectal polyps. Low- and high-grade adenomas are

classified as neoplastic polyps; hyperplastic polyps, inflammatory

polyps, juvenile polyps, and benign lymphoid polyps are considered

non-neoplastic polyps (11).

Therefore, with a sensitivity of 92.7% and specificity of 89.8%,

this CADx model has sufficient potential to help endoscopists

differentiate between neoplastic and non-neoplastic polyps during

colonoscopy and to achieve the level of performance required for a

‘leave-in-situ’ strategy for patients with non-neoplastic

polyps.

A CADx model has the capability to assist the

endoscopist in differentiating between neoplastic and

non-neoplastic polyps, allowing for the implementation of a

‘leave-in-situ’ strategy for non-neoplastic polyps. Additionally,

it provides support in accurately grading neoplastic polyps for a

‘resect-and-discard’ approach. Min et al (68) designed a CADx model for predicting

the pathological outcome (adenomatous vs. non-adenomatous) of

colorectal polyps based on the results of image color assessments

performed using LCI. Subsequently, it assisted the endoscopist in

the selective resection of neoplastic colorectal polyps. The model

exhibited a sensitivity of 83.3%, specificity of 70.1%, and

accuracy of 78.4% in efficiently differentiating adenomatous from

non-adenomatous polyps. These results are comparable to the

accuracy achieved by endoscopic specialists (78.4 vs. 79.6%).

As a result of their technical shortcomings,

traditional ML methods (such as SVMs) perform poorly when

converting endoscopic images and video features into numerical

data, leading to severe limitations in the development of CADx.

However, the advent of DL has simplified the numerical conversion

process of these features and substantially reduced their

developmental hindrance. In 2018, Chen et al (61) developed a CADx model based on a DL

algorithm that accurately classified small colorectal polyps

(tumors or hyperplastic lesions). A total of 284 magnified NBI

image samples of small colorectal polyps obtained from 193 patients

were used to assess the diagnostic accuracy of this CADx model. The

results showed that the model had a disease sensitivity of 96.3%,

specificity of 78.1%, and accuracy of 90.1%. In addition, the

algorithm enabled the discrimination between tumor and hyperplastic

lesions in a shorter time than the time required by endoscopists

and trainee endoscopists (0.45±0.07 vs. 1.54±1.30 vs. 1.77±1.37

sec), demonstrating its feasibility in clinical practice.

The CADx companion diagnostic results offer

standardized and objective assessments independent of the expertise

and experience of the endoscopist, reducing variations between

beginners and experts. By utilizing CADx, the endoscopist can more

easily make a qualitative diagnosis of the lesion and assess

disease activity while maintaining a higher level of accuracy.

However, the available data for most commercially available AI

tools for lesion characterization remain inconclusive rather than

definitive. The performance of CADx systems should be further

evaluated in prospective randomized controlled trials conducted

among both expert endoscopists and trainees to establish reliable

data and evidence (84).

Future prospects

AI has garnered significant interest in healthcare,

and its potential applications extend to various areas, including

endoscopy. AI-aided colonoscopy has demonstrated promising accuracy

in laboratory settings, and the performance of AI-aided diagnostic

systems has been validated in prospective randomized controlled

trials conducted in diverse healthcare settings, involving

endoscopists with varying levels of experience (75,85).

While the success of AI has been evident in small-sample trials,

the challenge lies in its widespread implementation in clinical

practice. Several issues need addressing before AI can be

effectively integrated into daily practice.

Although several computer-aided colorectal polyp

detection and diagnosis systems have been proposed for clinical

applications, numerous remain susceptible to interference problems

such as low image clarity, unevenness, and low accuracy in the

analysis of dynamic images. These drawbacks affect the robustness

and practicality of these systems (86). In this regard, an intraprocedural AI

alert system for colonoscopy examination has been proposed using

feature extraction and classification alongside a CNN model

(87). This system can identify

blurred images, instances of inadequate bowel cleansing, and

instances of insufficient air insufflation during colonoscopy.

Nevertheless, further clinical trials are required to verify

whether this system can improve the detection rate of colorectal

adenomas. Considering that the data of the study only comes from a

single medical center (87), a

large-scale prospective multicenter clinical trial is required to

validate the efficacy of the proposed system in increasing the

colon polyp detection rate.

In addition to the aforementioned challenges, the

development, integration, and widespread implementation of AI

models in clinical practice require significant investments in

terms of time, resources, and expertise (88,89).

Future studies should carefully consider the potential effects of

these factors. For instance, constructing AI models requires

entering numerous training and validation samples. Nevertheless,

high-quality labeled samples are difficult to obtain in clinical

settings, as these samples often contain numerous labeling errors,

referred to as labeling noise or ‘noisy labels’ (90), which markedly decreases the accuracy

of the model. In addition, AI training involves powerful computer

configurations and long training times, and post-maintenance can be

cumbersome. Clinicians, who are mostly non-specialists, can only

assist in diagnosis based on predefined functions during clinical

work. Therefore, it becomes difficult for doctors to update the

database and algorithm when encountering new cases in clinics.

These factors have greatly hindered the popularity and optimization

of AI systems. Fortunately, these restrictions are gradually being

overcome as a result of advances in computing power, increases in

the number of digitally-stored medical images, and improvements in

deep network (DPN) architecture. Future research should consider

establishing an open data-sharing platform across multiple

institutions to overcome these barriers. Appropriate data sharing

would not only reduce competition among agencies but also alleviate

the difficulties and costs associated with data access while

enhancing data quality (91).

The current laws and regulations for newly developed

AI tools by regulatory agencies are inadequate at this stage.

Nonetheless, the situation is changing rapidly. In January 2021,

the U.S. FDA released the first AI/ML-Based Software as a Medical

Device (SaMD) Action Plan of the agency, which details several

guidelines for AI implementation (92). However, refining the original

legislation may not be sufficient to regulate AI in healthcare. It

is crucial for lawmakers to engage in a collaborative process with

computer scientists, clinicians, patients, professional

associations, and health technology companies to establish a robust

regulatory and legal framework for AI-based tools. This

collaborative effort aims to ensure that AI tools meet acceptable

standards of quality and safety.

From a clinical perspective, establishing trust in

the clinical system is of utmost importance in AI-assisted

decision-making (93). One crucial

aspect in this regard is the stability of AI models. For clinical

application, the AI model must withstand multiple fluctuations in

the input data, such as operator-operator and laboratory-laboratory

differences in data quality, resolution, intensity, and disease

characteristics. However, most AI models have not demonstrated

sufficient stability in the face of such fluctuations, which makes

rigorous quality control necessary. Both the passage of time and

changes in the patient population may lead to deviations in AI

model performance; therefore, AI models applied in clinical

settings must undergo regular quality monitoring and maintenance to

maintain a stable clinical performance (88). The development of standards and

guidelines for testing AI models could systematically assess the

performance of AI-based tools and obtain precise and uniform

measurements. This is the key component in future attempts to

overcome distrust in the clinical system.

The combination of AI and colonoscopy holds

practical and feasible potential, offering promising prospects for

the future (94). Genetic testing

and immune typing, coupled with AI technologies such as DL, have

shown promise in CRC research, providing insights into tumor

pathogenesis at the molecular level and offering theoretical

support for CRC diagnosis and treatment. Numerous studies have

supported that using AI to detect genetic mutations in CRC is a

reliable method to offer a new treatment option for targeted

therapy (94,95). Mutations in KRAS and BRAF genes are

the main predictive biomarkers for the response to anti-EGFR

monoclonal antibody-targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal

cancer (96). Some scholars have

used the DL method based on a residual NN and ML-based CT texture

analysis to achieve the noninvasive prediction of the KRAS mutation

status in CRC (97,98), while others have used a random

forest classifier (RFC) model to predict the V600E mutation in the

BRAF (97). This integration of AI

with genetic testing and immune typing has the potential to enhance

the accuracy and effectiveness of colonoscopy screening and

diagnosis. However, relevant literature was reviewed and it was

determined that there is no research currently on their use in

colonoscopy.

To summarize, the combination of AI and colonoscopy

is practical and feasible, and the future is bright; however,

further exploration and innovation are still expected.

Conclusion

CRC is one of the most common tumors worldwide,

accounting for 10% of all tumors. It is estimated that 608,000

people succumb to CRC annually (~8% of all cancer-related deaths).

In addition, CRC incidence and mortality rates among adults under

50 years of age have been consistently increasing at an annual rate

of 1.5% (2014–2018) and 1.2% (2005–2019), in recent years.

Moreover, the global CRC disease burden is continuously increasing,

with a trend toward younger incidence (1,99).

Although colonoscopy is valuable in decreasing the

mortality or morbidity of CRC, its diagnostic accuracy still falls

short of clinical needs, particularly for premalignant lesions or

early-stage CRC. The introduction of AI in colonoscopy may

potentially improve these deficiencies. For instance, various

studies have shown that AI-based high-level auxiliary diagnostic

systems can significantly improve the readability of medical images

and help clinicians make accurate diagnostic and therapeutic

decisions. In addition, CNNs can aid in the interpretation of

histopathological tissue images, reducing inter-observer

variability among doctors. Furthermore, CADe systems can

significantly improve polyp and ADRs during early colonoscopy

screenings, enhancing the differential diagnosis of non-neoplastic

vs. neoplastic polyps and adenomatous vs. non-adenomatous polyps,

thereby decreasing the possibility of mutating into CRC.

Additionally, AI has the potential to contribute to cost-saving

strategies by minimizing the need for unnecessary polypectomies and

pathology examinations. Overall, the key findings of this review

are that AI-aided colonoscopy could facilitate the efficiency and

accuracy of CRC screening and diagnosis and ameliorate patient

clinical outcomes and prognosis.

Preliminary data on AI-assisted systems are

promising; however, the lack of high-quality clinical studies

prevents reliable conclusions. It is essential to conduct

higher-quality research using modern trial designs to improve the

understanding of this field. Special attention should be given to

utilizing larger datasets and prospectively validating AI systems

in clinical settings. Moreover, these systems must provide quality

assurance within a robust ethical and legal framework before

clinicians and patients fully embrace them.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82074214 and 81973598) and the Key

project of Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of

Zhejiang province (grant no. 2022ZZ014).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

SZ and GC conceived and designed the review. MD and

JY collected and reviewed the literature as well as drafted the

manuscript. SZ, MD and JY edited and revised the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

USPSTF

|

U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce

|

|

AI

|

artificial intelligence

|

|

ADR

|

adenoma detection rate

|

|

ML

|

machine learning

|

|

DL

|

deep learning

|

|

CADe

|

computer-aided detection

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Trepanier M, Minnella EM, Paradis T,

Awasthi R, Kaneva P, Schwartzman K, Carli F, Fried GM, Feldman LS

and Lee L: Improved Disease-free survival after prehabilitation for

colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 270:493–501. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Brenner H, Kloor M and Pox CP: Colorectal

cancer. Lancet. 383:1490–1502. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Click B, Pinsky PF, Hickey T, Doroudi M

and Schoen RE: Association of colonoscopy adenoma findings with

Long-term colorectal cancer incidence. JAMA. 319:2021–2031. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Shinya H and Wolff WI: Morphology,

anatomic distribution and cancer potential of colonic polyps. Ann

Surg. 190:679–683. 1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ladabaum U, Dominitz JA, Kahi C and Schoen

RE: Strategies for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology.

158:418–432. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

US Preventive Services Task Force, .

Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM,

Donahue KE, Doubeni CA, Krist AH, et al: Screening for colorectal

cancer: US Preventive services task force recommendation statement.

JAMA. 325:1965–1977. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI

and Blasi PR: Screening for colorectal cancer: Updated evidence

report and systematic review for the US preventive services task

force. JAMA. 325:1978–1998. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Barua I, Vinsard DG, Jodal HC, Loberg M,

Kalager M, Holme O, Holme Ø, Misawa M, Bretthauer M and Mori Y:

Artificial intelligence for polyp detection during colonoscopy: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 53:277–284. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gao P, Zhou K, Su W, Yu J and Zhou P:

Endoscopic management of colorectal polyps. Gastroenterol Rep

(Oxf). 11:goad0272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Meseeha M and Attia M: Colon Polyps.

StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure:

Maximos Attia declares no relevant financial relationships with

ineligible companies. 2023.

|

|

12

|

Kamaradova K: Non-conventional types of

dysplastic changes in gastrointestinal tract mucosa-review of

morphological features of individual subtypes. Cesk Patol.

58:38–51. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Keum N and Giovannucci E: Global burden of

colorectal cancer: Emerging trends, risk factors and prevention

strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:713–732. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Crockett SD and Nagtegaal ID: Terminology,

molecular features, epidemiology, and management of serrated

colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 157:949–66.e4. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Haghighat S, Sussman DA and Deshpande A:

US preventive services task force recommendation statement on

screening for colorectal cancer. JAMA. 326:13282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Carethers JM: Fecal DNA testing for

colorectal cancer screening. Annu Rev Med. 71:59–69. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, Ederer F,

Geisser MS, Mongin SJ, Snover DC and Schuman LM: The effect of

fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer.

N Engl J Med. 343:1603–1607. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Faivre J, Dancourt V, Lejeune C, Tazi MA,

Lamour J, Gerard D, Dassonville F and Bonithon-Kopp C: Reduction in

colorectal cancer mortality by fecal occult blood screening in a

French controlled study. Gastroenterology. 126:1674–1680. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kronborg O, Jorgensen OD, Fenger C and

Rasmussen M: Randomized study of biennial screening with a faecal

occult blood test: Results after nine screening rounds. Scand J

Gastroenterol. 39:846–851. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Scholefield JH, Moss SM, Mangham CM,

Whynes DK and Hardcastle JD: Nottingham trial of faecal occult

blood testing for colorectal cancer: A 20-year follow-up. Gut.

61:1036–1040. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, Lederle

FA, Bond JH, Mandel JS and Church TR: Long-term mortality after

screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 369:1106–1114. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chiu HM, Chen SL, Yen AM, Chiu SY, Fann

JC, Lee YC, Pan SL, Wu MS, Liao CS, Chen HH, et al: Effectiveness

of fecal immunochemical testing in reducing colorectal cancer

mortality from the One Million Taiwanese Screening Program. Cancer.

121:3221–3229. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zorzi M, Fedeli U, Schievano E, Bovo E,

Guzzinati S, Baracco S, Fedato C, Saugo M and Dei Tos AP: Impact on

colorectal cancer mortality of screening programmes based on the

faecal immunochemical test. Gut. 64:784–790. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Redwood DG, Dinh TA, Kisiel JB, Borah BJ,

Moriarty JP, Provost EM, Sacco FD, Tiesinga JJ and Ahlquist DA:

Cost-Effectiveness of multitarget stool DNA testing vs colonoscopy

or fecal immunochemical testing for colorectal cancer screening in

alaska native people. Mayo Clin Proc. 96:1203–1217. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Atkin W, Wooldrage K, Parkin DM,

Kralj-Hans I, MacRae E, Shah U, Duffy S and Cross AJ: Long term

effects of once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening after 17

years of follow-up: The UK Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening

randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 389:1299–1311. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, Flowers

CR, Guerra CE, LaMonte SJ, Etzioni R, McKenna MT, Oeffinger KC and

Shih YT: Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018

guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J

Clin. 68:250–281. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T,

Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al:

Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower

endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 369:1095–1105. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Calderwood AH and Jacobson BC: Colonoscopy

quality: Metrics and implementation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am.

42:599–618. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhao S, Wang S, Pan P, Xia T, Chang X,

Yang X, Guo L, Meng Q, Yang F, Qian W, et al: Magnitude, risk

factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem

colonoscopy: A Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Gastroenterology. 156:1661–1674.e11. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kaminski MF, Wieszczy P, Rupinski M,

Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Kraszewska E, Kobiela J, Franczyk R,

Rupinska M, Kocot B, et al: Increased rate of adenoma detection

associates with reduced risk of colorectal cancer and death.

Gastroenterology. 153:98–105. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Rabeneck L and Paszat LF: Circumstances in

which colonoscopy misses cancer. Frontline Gastroenterol. 1:52–58.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Rutter MD, Beintaris I, Valori R, Chiu HM,

Corley DA, Cuatrecasas M, Dekker E, Forsberg A, Gore-Booth J, Haug

U, et al: World endoscopy organization consensus statements on

Post-Colonoscopy and Post-Imaging colorectal cancer.

Gastroenterology. 155:909–25.e3. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT, Mumford

JE, Afshin A, Estep K, Veerman JL, Delwiche K, Iannarone ML, Moyer

ML, et al: Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon

cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke

events: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. BMJ. 354:i38572016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Morris EJ, Rutter MD, Finan PJ, Thomas JD

and Valori R: Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer (PCCRC) rates vary

considerably depending on the method used to calculate them: A

retrospective observational population-based study of PCCRC in the

English National Health Service. Gut. 64:1248–1256. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Anderson R, Burr NE and Valori R: Causes

of Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancers based on world endoscopy

organization system of analysis. Gastroenterology.

158:1287–1299.e2. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hassan C, Piovani D, Spadaccini M, Parigi

T, Khalaf K, Facciorusso A, Fugazza A, Rösch T, Bretthauer M, Mori

Y, et al: Variability in adenoma detection rate in control groups

of randomized colonoscopy trials: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 97:212–225.e7. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Burr N and Valori R: National

post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer data challenge services to

improve quality of colonoscopy. Endosc Int Open. 7:E728–E729. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wallace MB, Sharma P, Bhandari P, East J,

Antonelli G, Lorenzetti R, Vieth M, Speranza I, Spadaccini M, Desai

M, et al: Impact of artificial intelligence on miss rate of

colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 163:295–304.e5. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hamet P and Tremblay J: Artificial

intelligence in medicine. Metabolism. 69S:S36–S40. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Bishop C: Pattern Recognition and Machine

Learning (Information Science and Statistics). Springer; April

6–2011, ISBN-10: 03873107382011. 2011.

|

|

41

|

LeCun Y, Bengio Y and Hinton G: Deep

learning. Nature. 521:436–444. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Esteva A, Robicquet A, Ramsundar B,

Kuleshov V, DePristo M, Chou K, Cui C, Corrado G, Thrun S and Dean

J: A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat Med. 25:24–29. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Krenzer A, Makowski K, Hekalo A, Fitting

D, Troya J, Zoller WG, Hann A and Puppe F: Fast machine learning

annotation in the medical domain: A semi-automated video annotation

tool for gastroenterologists. Biomed Eng Online. 21:332022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bera K, Schalper KA, Rimm DL, Velcheti V

and Madabhushi A: Artificial intelligence in digital pathology-new

tools for diagnosis and precision oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

16:703–715. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK,

Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger

JE, et al: Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and

death. N Engl J Med. 370:1298–1306. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Greenspan M, Rajan KB, Baig A, Beck T,

Mobarhan S and Melson J: Advanced adenoma detection rate is

independent of nonadvanced adenoma detection rate. Am J

Gastroenterol. 108:1286–1292. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Singh H, Turner D, Xue L, Targownik LE and

Bernstein CN: Risk of developing colorectal cancer following a

negative colonoscopy examination: Evidence for a 10-year interval

between colonoscopies. JAMA. 295:2366–2373. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM,

Rickert A and Hoffmeister M: Protection from colorectal cancer

after colonoscopy: A population-based, case-control study. Ann

Intern Med. 154:22–30. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF,

Saskin R, Urbach DR and Rabeneck L: Association of colonoscopy and

death from colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 150:1–8. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kahi CJ, Imperiale TF, Juliar BE and Rex

DK: Effect of screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence

and mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 7:770–775; quiz 11.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Maroulis DE, Iakovidis DK, Karkanis SA and

Karras DA: CoLD: A versatile detection system for colorectal

lesions in endoscopy video-frames. Comput Methods Programs Biomed.

70:151–166. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Karkanis SA, Iakovidis DK, Maroulis DE,

Karras DA and Tzivras M: Computer-aided tumor detection in

endoscopic video using color wavelet features. IEEE Trans Inf

Technol Biomed. 7:141–152. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Misawa M, Kudo SE, Mori Y, Cho T, Kataoka

S, Yamauchi A, Ogawa Y, Maeda Y, Takeda K, Ichimasa K, et al:

Artificial Intelligence-Assisted polyp detection for colonoscopy:

Initial experience. Gastroenterology. 154:2027–2029.e3. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Yamada M, Saito Y, Imaoka H, Saiko M,

Yamada S, Kondo H, Takamaru H, Sakamoto T, Sese J, Kuchiba A, et

al: Development of a real-time endoscopic image diagnosis support

system using deep learning technology in colonoscopy. Sci Rep.

9:144652019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang P, Berzin TM, Glissen Brown JR,

Bharadwaj S, Becq A, Xiao X, Liu P, Li L, Song Y, Zhang D, et al:

Real-time automatic detection system increases colonoscopic polyp

and adenoma detection rates: A prospective randomised controlled

study. Gut. 68:1813–1819. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang P, Liu X, Berzin TM, Glissen Brown

JR, Liu P, Zhou C, Lei L, Li L, Guo Z, Lei S, et al: Effect of a

deep-learning computer-aided detection system on adenoma detection

during colonoscopy (CADe-DB trial): A double-blind randomised

study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5:343–351. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Gong D, Wu L, Zhang J, Mu G, Shen L, Liu

J, Wang Z, Zhou W, An P, Huang X, et al: Detection of colorectal

adenomas with a real-time computer-aided system (ENDOANGEL): A

randomised controlled study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

5:352–361. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Urban G, Tripathi P, Alkayali T, Mittal M,

Jalali F, Karnes W and Baldi P: Deep learning localizes and

identifies polyps in real time with 96% accuracy in screening

colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 155:1069–1078.e8. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kamitani Y, Nonaka K and Isomoto H:

Current status and future perspectives of artificial intelligence

in colonoscopy. J Clin Med. 11:29232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Gonzalez-Bueno Puyal J, Brandao P, Ahmad

OF, Bhatia KK, Toth D, Kader R, Lovat L, Mountney P and Stoyanov D:

Polyp detection on video colonoscopy using a hybrid 2D/3D CNN. Med

Image Anal. 82:1026252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Chen PJ, Lin MC, Lai MJ, Lin JC, Lu HH and

Tseng VS: Accurate classification of diminutive colorectal polyps

using computer-aided analysis. Gastroenterology. 154:568–575. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Ng K, May FP and Schrag D: US preventive

services task force recommendations for colorectal cancer

screening: Forty-five is the new fifty. JAMA. 325:1943–1945. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Huang D, Shen J, Hong J, Zhang Y, Dai S,

Du N, Zhang M and Guo D: Effect of artificial intelligence-aided

colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: A meta-analysis of

randomized clinical trials. Int J Colorectal Dis. 37:495–506. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Koh FH, Ladlad J, Centre SKHE, Teo EK, Lin

CL and Foo FJ: Real-time artificial intelligence (AI)-aided

endoscopy improves adenoma detection rates even in experienced

endoscopists: A cohort study in Singapore. Surg Endosc. 37:165–171.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Spadaccini M, Marco A, Franchellucci G,

Sharma P, Hassan C and Repici A: Discovering the first US

FDA-approved computer-aided polyp detection system. Future Oncol.

18:1405–1412. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Seager A, Sharp L, Hampton JS, Neilson LJ,

Lee TJW, Brand A, Evans R, Vale L, Whelpton J and Rees CJ: Trial

protocol for COLO-DETECT: A randomized controlled trial of lesion

detection comparing colonoscopy assisted by the GI Genius

artificial intelligence endoscopy module with standard colonoscopy.

Colorectal Dis. 24:1227–1237. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Houwen B, Hassan C, Coupe VMH, Greuter

MJE, Hazewinkel Y, Vleugels JLA, Antonelli G, Bustamante-Balén M,

Coron E, Cortas GA, et al: Definition of competence standards for

optical diagnosis of diminutive colorectal polyps: European Society

of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy.

54:88–99. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Byrne MF, Chapados N, Soudan F, Oertel C,

Linares Perez M, Kelly R, Iqbal N, Chandelier F and Rex DK:

Real-time differentiation of adenomatous and hyperplastic

diminutive colorectal polyps during analysis of unaltered videos of

standard colonoscopy using a deep learning model. Gut. 68:94–100.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Min M, Su S, He W, Bi Y, Ma Z and Liu Y:

Computer-aided diagnosis of colorectal polyps using linked color

imaging colonoscopy to predict histology. Sci Rep. 9:28812019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Aihara H, Saito S, Inomata H, Ide D, Tamai

N, Ohya TR, Kato T, Amitani S and Tajiri H: Computer-aided

diagnosis of neoplastic colorectal lesions using ‘real-time’

numerical color analysis during autofluorescence endoscopy. Eur J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 25:488–494. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Tischendorf JJ, Gross S, Winograd R,

Hecker H, Auer R, Behrens A, Trautwein C, Aach T and Stehle T:

Computer-aided classification of colorectal polyps based on

vascular patterns: A pilot study. Endoscopy. 42:203–207. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Gross S, Trautwein C, Behrens A, Winograd

R, Palm S, Lutz HH, Schirin-Sokhan R, Hecker H, Aach T and

Tischendorf JJ: Computer-based classification of small colorectal

polyps by using narrow-band imaging with optical magnification.

Gastrointest Endosc. 74:1354–1359. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Mori Y, Kudo SE, Misawa M, Saito Y,

Ikematsu H, Hotta K, Ohtsuka K, Urushibara F, Kataoka S, Ogawa Y,

et al: Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification

of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: A prospective study. Ann

Intern Med. 169:357–366. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Vinsard DG, Mori Y, Misawa M, Kudo SE,

Rastogi A, Bagci U, Rex DK and Wallace MB: Quality assurance of

computer-aided detection and diagnosis in colonoscopy. Gastrointest

Endosc. 90:55–63. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Spadaccini M, Massimi D, Mori Y, Alfarone

L, Fugazza A, Maselli R, Sharma P, Facciorusso A, Hassan C and

Repici A: Artificial intelligence-aided endoscopy and colorectal

cancer screening. Diagnostics (Basel). 13:11022023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Hassan C, Pickhardt PJ and Rex DK: A

resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of

colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

8:865–869.e1-e3. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Hassan C, Balsamo G, Lorenzetti R, Zullo A

and Antonelli G: Artificial intelligence allows leaving-in-situ

colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 20:2505–2513.e4.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Sánchez-Montes C, Sánchez FJ, Bernal J,

Córdova H, López-Cerón M, Cuatrecasas M, Rodríguez de Miguel C,

García-Rodríguez A, Garcés-Durán R, Pellisé M, et al:

Computer-aided prediction of polyp histology on white light

colonoscopy using surface pattern analysis. Endoscopy. 51:261–265.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Yoshida N, Inoue K, Tomita Y, Kobayashi R,

Hashimoto H, Sugino S, Hirose R, Dohi O, Yasuda H, Morinaga Y, et

al: An analysis about the function of a new artificial

intelligence, CAD EYE with the lesion recognition and diagnosis for

colorectal polyps in clinical practice. Int J Colorectal Dis.

36:2237–2245. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Barbeiro S, Libanio D, Castro R,

Dinis-Ribeiro M and Pimentel-Nunes P: Narrow-band imaging: Clinical

application in gastrointestinal endoscopy. GE Port J Gastroenterol.

26:40–53. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Tamaki T, Yoshimuta J, Kawakami M,

Raytchev B, Kaneda K, Yoshida S, Takemura Y, Onji K, Miyaki R and

Tanaka S: Computer-aided colorectal tumor classification in NBI

endoscopy using local features. Med Image Anal. 17:78–100. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Wimmer G, Tamaki T, Tischendorf JJ, Hafner

M, Yoshida S, Tanaka S and Uhl A: Directional wavelet based

features for colonic polyp classification. Med Image Anal.

31:16–36. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Hafner M, Tamaki T, Tanaka S, Uhl A,

Wimmer G and Yoshida S: Local fractal dimension based approaches

for colonic polyp classification. Med Image Anal. 26:92–107. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Mori Y, Neumann H, Misawa M, Kudo SE and

Bretthauer M: Artificial intelligence in colonoscopy-Now on the

market. What's next? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 36:7–11. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Nazarian S, Glover B, Ashrafian H, Darzi A

and Teare J: Diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence and

computer-aided diagnosis for the detection and characterization of

colorectal polyps: Systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Med

Internet Res. 23:e273702021. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Hassan C, Badalamenti M, Maselli R,

Correale L, Iannone A, Radaelli F, Rondonotti E, Ferrara E,

Spadaccini M, Alkandari A, et al: Computer-aided detection-assisted

colonoscopy: Classification and relevance of false positives.

Gastrointest Endosc. 92:900–904.e4. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Hsu CM, Hsu CC, Hsu ZM, Chen TH and Kuo T:

Intraprocedure artificial intelligence alert system for colonoscopy

examination. Sensors (Basel). 23:12112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Elemento O, Leslie C, Lundin J and

Tourassi G: Artificial intelligence in cancer research, diagnosis

and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 21:747–752. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wei JW, Suriawinata AA, Vaickus LJ, Ren B,

Liu X, Lisovsky M, Tomita N, Abdollahi B, Kim AS, Snover DC, et al:

Evaluation of a deep neural network for automated classification of

colorectal polyps on histopathologic slides. JAMA Netw Open.

3:e2033982020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Karimi D, Dou H, Warfield SK and Gholipour

A: Deep learning with noisy labels: Exploring techniques and

remedies in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 65:1017592020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Huang P, Feng Z, Shu X, Wu A, Wang Z, Hu

T, Cao Y, Tu Y and Li Z: A bibliometric and visual analysis of

publications on artificial intelligence in colorectal cancer

(2002–2022). Front Oncol. 13:10775392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Clark P, Kim J and Aphinyanaphongs Y:

Marketing and US food and drug administration clearance of

artificial intelligence and machine learning enabled software in

and as medical devices: A systematic review. JAMA Netw Open.

6:e23217922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Bhinder B, Gilvary C, Madhukar NS and

Elemento O: Artificial intelligence in cancer research and

precision medicine. Cancer Discov. 11:900–915. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Yin Z, Yao C, Zhang L and Qi S:

Application of artificial intelligence in diagnosis and treatment

of colorectal cancer: A novel Prospect. Front Med (Lausanne).

10:11280842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Sorokin M, Zolotovskaia M, Nikitin D,

Suntsova M, Poddubskaya E, Glusker A, Garazha A, Moisseev A, Li X,

Sekacheva M, et al: Personalized targeted therapy prescription in

colorectal cancer using algorithmic analysis of RNA sequencing

data. BMC Cancer. 22:11132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Sanchez-Ibarra HE, Jiang X,

Gallegos-Gonzalez EY, Cavazos-Gonzalez AC, Chen Y, Morcos F and

Barrera-Saldaña HA: KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutation prevalence,

clinicopathological association, and their application in a

predictive model in Mexican patients with metastatic colorectal

cancer: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 15:e02354902020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

He K, Liu X, Li M, Li X, Yang H and Zhang

H: Noninvasive KRAS mutation estimation in colorectal cancer using

a deep learning method based on CT imaging. BMC Med Imaging.

20:592020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Taguchi N, Oda S, Yokota Y, Yamamura S,

Imuta M, Tsuchigame T, Nagayama Y, Kidoh M, Nakaura T, Shiraishi S,

et al: CT texture analysis for the prediction of KRAS mutation

status in colorectal cancer via a machine learning approach. Eur J

Radiol. 118:38–43. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Spaander MCW, Zauber AG, Syngal S, Blaser

MJ, Sung JJ, You YN and Kuipers EJ: Young-onset colorectal cancer.

Nat Rev Dis Primers. 9:212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|