Lymphomas are malignant tumors in which lymphocytes

in the human body undergo different stages of development and

differentiation (17). Lymphomas

exhibit high levels of heterogeneity and a complex pathological

classification, with different treatment responses among different

pathological types. In addition, treatment responses may differ

between patients with the same pathological type. Numerous factors,

including cell proteomics and molecular features may impact the

prognosis of patients (18). In

clinical practice, patients with DLBCL often develop drug

resistance (19), which is a

barrier to treatment within clinical practice. Liu et al

(20) examined samples from 14

patients with untreated DLBCL using mass spectrometry and

two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis, and quantitatively

identified differentially expressed proteins between patients who

were susceptible to CHOP treatment and those who were resistant.

This approach allowed the comprehensive characterization of the

proteomic landscape associated with chemotherapy response in DLBCL;

thus, providing valuable insights into potential biomarkers and

therapeutic targets for improving treatment outcomes. Results of

the previous study demonstrated that the protein expression levels

of histone H2A.2, S100A9, Ezrin and Pleckstrin were significantly

increased. In addition, the protein expression levels of 61 kD

protein, collagen alpha 1 (VI), glutathione S-transferase pi-1 and

heat shock protein beta 1 were significantly lower in patients who

were susceptible to CHOP treatment, compared with those that were

resistant. Analyzing the protein network associated with resistance

to CHOP chemotherapy may aid in identifying patients with DLBCL

with CHOP resistance; thus, providing a novel theoretical basis for

the identification of therapeutic targets.

Tumors form dynamic, complex and heterogeneous

environments with various cells and surrounding components, known

as the TME (21). The heterogeneity

of DLBCL is associated with the types of cells in the TME (22), including matrix components,

dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes, fibroblasts and T cells

(23). Notably, the extracellular

matrix interacts with lymphoma cells (24), and high numbers of M2 macrophages,

natural killer cells and plasma cells are associated with lower

survival rates in patients with DLBCL (25). The TME plays a significant role in

the initiation, development and treatment resistance of DLBCL, and

these factors ultimately impact the prognosis of patients (19). In total, ~75% of patients with DLBCL

possess aberrations in genes associated with immune escape

(26), and the TME includes

numerous inhibitory immune detection points (27). Liu et al (28) suggested that adaptor-related protein

complex 2 subunit mu1 subunit may contribute to the resistance of

DLBCL to chemotherapy and targeted medications through controlling

the TME. Notably, results of previous studies highlighted that

multiple components in the TME may impact the occurrence and

development of DLBCL. Spatial proteomics analysis may provide

location information for cells in the tissue (29), and this method may be used to

explore the interaction between DLBCL cells and the TME (30).

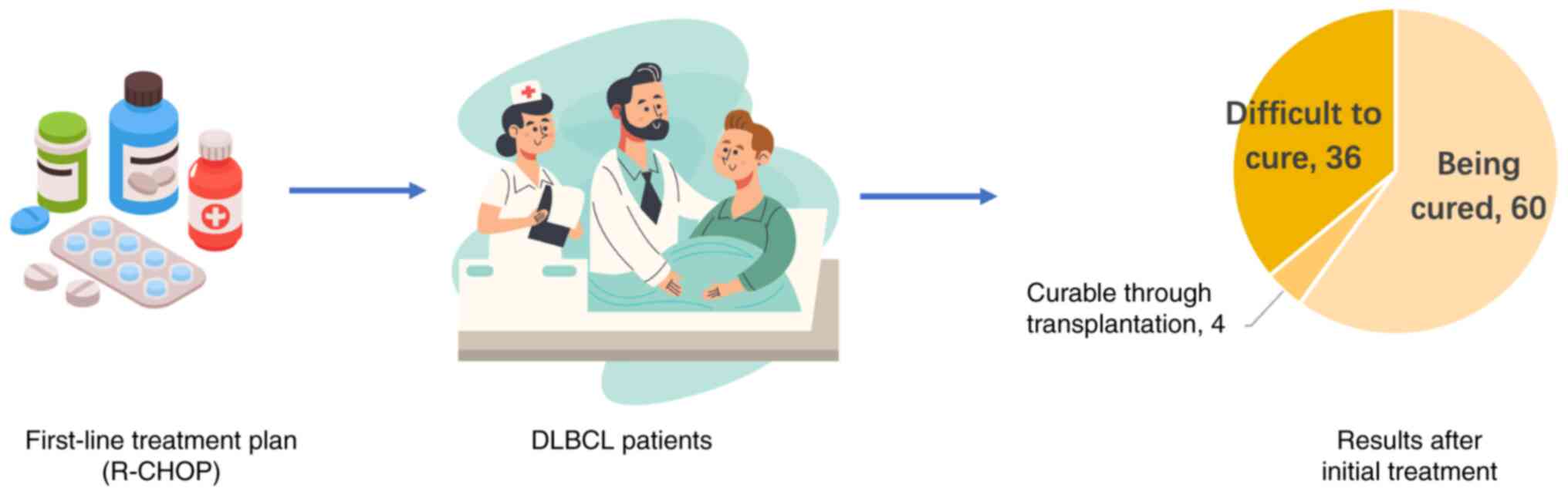

The discovery and application of anti-CD20

monoclonal antibodies in the early 20th century led to a new era of

DLBCL treatment (35). At present,

global treatment guidelines recommend first-line therapy with

R-CHOP, comprising rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin,

vincristine and prednisone (36),

leading to a cure in ~60% of patients (37). However, a small number of patients

continue to exhibit refractory disease or relapse following

complete remission (38), and

traditional salvage immunochemotherapy combined with autologous

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation only achieves a cure in

~10% of these patients (39). Thus,

the remaining 90% of patients exhibit poor treatment outcomes

(Fig. 1). Thus, improving the

prognosis of these patients is complex (40), and further proteomic analyses are

required to determine the signaling pathways associated with the

onset and progression of DLBCL (41). Novel developments in proteomics

technology have led to the discovery of multiple drug resistance

mechanisms in lymphoma (42); thus,

strategies and methods that eliminate the drug resistance of

lymphoma cells and improve the therapeutic effects are also

required (43).

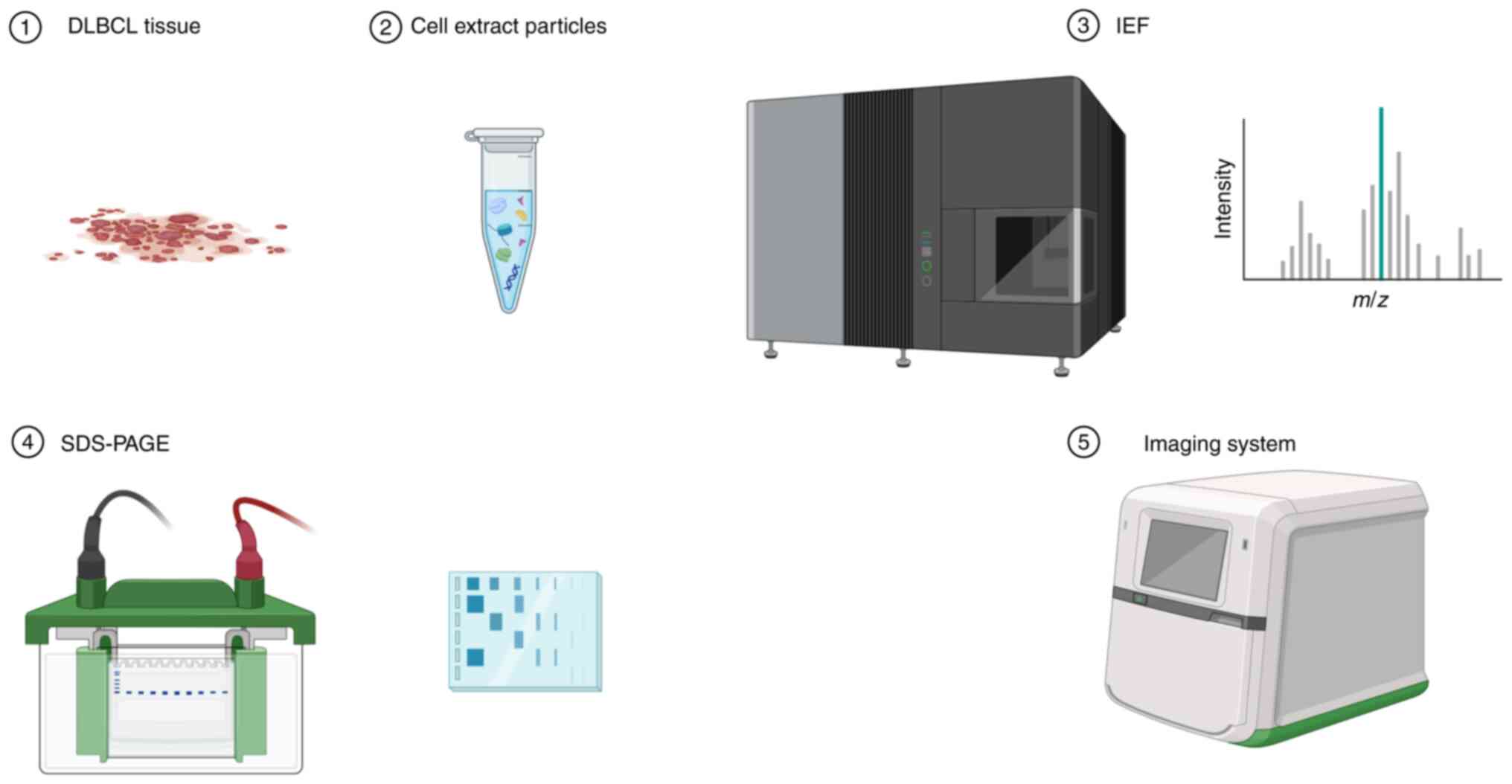

Proteomics includes the identification of

differentially expressed proteins in DLBCL tissues (44), obtaining 2D electrophoresis profiles

(45), and the use of mass

spectrometry to identify associated proteins (46) (Fig.

2). Bioinformatics analysis is also used to identify

differentially expressed proteins for further validation at the

tissue level, which may provide a theoretical basis for subsequent

experiments (47). In addition,

further investigations are required to determine the specific

mechanisms of DLBCL resistance and verify the feasibility of

differentially expressed proteins as drug-resistance-related

targets (48). Chen et al

(49) carried out mRNA/protein

analysis of clinicopathological samples, and the results

demonstrated that inhibitors of bromodomain and extraterminal (BET)

protein inhibited the progression of DLBCL. BET inhibition led to

upregulation of GTPase regulatory protein (IQGAP3), which inhibited

RAS protein activity in DLBCL cells, indicating that patients with

DLBCL with low IQGAP3 expression levels exhibited a poor prognosis.

In addition, BET inhibitors effectively controlled the progression

of DLBCL. Collectively, these results provided a theoretical basis

for targeting the BET protein (50)

as a potential treatment strategy for DLBCL.

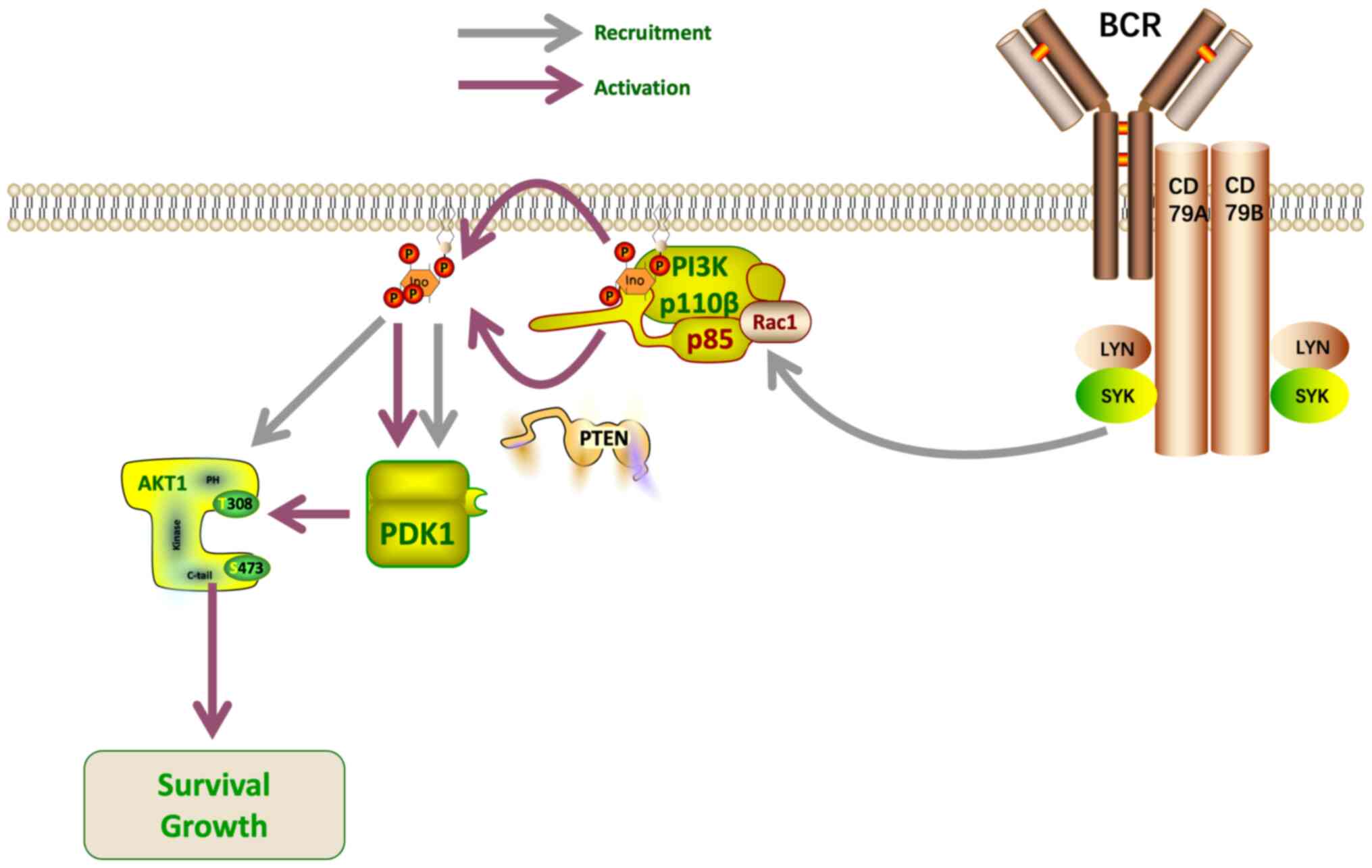

Advances in proteomics-associated technologies have

demonstrated that the emergence of DLBCL chemoresistance is closely

associated with signaling pathways (51), including the PI3K/Akt pathway. Akt

promotes cell survival and proliferation (52), as well as dysregulation of key

effectors controlling cell metabolism (53). A proteomics analysis conducted by Xu

et al (52) revealed that

removal of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway antagonist, PTEN, led to

inactivation of the PI3K/Akt pathway in GCB DLBCL. Thus, PI3K/Akt

activation may play a key role in the development of GCB DLBCL, and

these findings demonstrate the potential value of PTEN as a

therapeutic target. PTEN acts as a lipoprotein phosphatase,

dephosphorylating the 3′ position of phosphatidylinositol

triphosphate, thereby reducing Akt activation (Fig. 3). Measurement of phosphorylated Akt

levels indicated that PTEN expression was negatively correlated

with PI3K/Akt activation in both a GCB DLBCL model and primary

DLBCL samples (52). Bisserier and

Wajapeyee (54) demonstrated that

DLBCL cells resistant to Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 inhibitors

exhibited activation of insulin-like growth factor I receptor,

PI3K, and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Feng et

al (34) used proteomics

technology to demonstrate the increased expression levels of

exocrine carbonic anhydrase (CA)1, and the role of this protein as

a biomarker for the prognosis of DLBCL. Notably, CA1 expression

levels were also associated with an increased resistance to

chemotherapy via the signal transducer and activator of

transcription 3 signaling pathways and nuclear factor-κB.

Collectively, these results indicated that proteomic

techniques exhibit potential in the differential and enrichment

analyses of DLBCL-associated proteins for the subsequent discovery

of novel therapeutic targets. Specific signaling pathway inhibitors

also exhibit potential in highlighting the molecular mechanisms

underlying drug resistance; thus, leading to the development of

novel therapeutic options.

Proteomics technologies have improved the current

understanding of the molecular changes associated with DLBCL

(55,56). Storage of large amounts of

proteomics data (57) is

challenging; however, these often contain biologically significant

results (7). Data storage may be

aided through a combination of multiple omics techniques (58), and numerous biological techniques

are used to examine lymphomas (59), including genomics (60), proteomics (61), epigenetics (62) and radiomics (63).

Moreover, results of previous studies revealed a

regulatory role of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK4)

in lymphoma cell proliferation and inflammation through proteome

and phosphorylation modifications (68). A series of targeted degradation

agents of IRAK4 were used to study the effects of impaired IRAK4

function on the phosphorylation levels of downstream signaling

proteins, and the results demonstrated that IRAK4 only partially

participated in the regulation of ABC DLBCL cell proliferation and

inflammatory signals (69). The

survival of ABC DLBCL cells was not solely dependent on the

function of IRAK4; thus, highlighting a requirement for the

development of other drug targets in ABC DLBCL (70).

The integration of multi-omics technologies exhibits

potential in the treatment of DLBCL (76). Proteomics may also be used in

conjunction with other omics techniques, such as transcriptomics,

metabolomics and genomics, to further the current understanding of

the molecular landscape and mechanisms underlying DLBCL (77). This integrative approach exhibits

potential in the discovery of novel biomarkers, therapeutic targets

and personalized treatment strategies for patients with DLBCL.

In conclusion, proteomics techniques are widely

established in the study of DLBCL (78), and proteomics have been used in

investigating the pathogenesis, drug resistance and mechanisms of

lymphoma, the evaluation of prognosis, and guiding treatment plans

(79). Further developments in

proteomics-associated technologies are required for the

identification of novel drugs and drug targets for the treatment of

DLBCL (80). For example, Maurer

et al (81) found that DLBCL

patients with elevated serum free light chain (sFLC) had a

relatively poor prognosis using FREELITE analysis. Then, Witzig

et al (82) conducted a

6-year monitoring of FLC concentrations in patients with DLBCL and

found that patients with DLBCL belonged to the FLC monoclonal and

polyclonal groups; and the results revealed that elevated FLC was

an adverse factor in the poor prognosis of DLBCL patients, and the

aforementioned study provides new ideas for the treatment of DLBCL

(7). Spatial proteomics, also known

as spatiomics technology, is advancing (83). This technique is used to examine

biological components, such as RNA and proteins, and adds

‘location’ dimensional information to further the current

understanding of the microenvironment (84). Spatial proteomics has been used in

breast cancer research and treatment; Cords et al (85) used highly multiplexed imaging mass

cytometry on breast cancer samples matched to single-cell RNA

sequencing datasets to confirm their cancer-associated fibroblast

phenotypes defined at the protein level, and used spatial

proteomics to analyze their spatial distributions in tumors, which

provided a new strategy for this treatment. Notably, spatial

proteomics is being used in lymphoma research (86), and may exhibit potential in the

treatment of DLBCL. Spatial proteomics involves analysis of the

subcellular localization of proteins in a systematic and

high-throughput manner (87), where

proteins simultaneously exist in different subcellular locations

(88) and travel between them

(89). For example, spatial

proteomics may be used to demonstrate the spatial profile of

proteins in the liver of patients with obesity, and these results

are compared with healthy individuals to determine the localization

of hepatocytes. Thus, spatial proteomics may aid in the treatment

of patients with liver disease (90). In an era of rapid advances in

medical technology, the use of spatial proteomics for the analysis

and precise treatment of DLBCL can help to develop personalized

treatment plans for patients and improve the cure and survival

rates of DLBCL patients. However, due to the limitations of

research methods and research data, there is still a lot of space

for the wide application of spatial proteomics.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Jilin (grant no. YDZJ202201ZYTS117).

Not applicable.

ZG and CW authored or reviewed drafts of the

manuscript, and approved the final draft. XS, ZW, JT and JM

provided figures and helped with proofreading of draft. LB prepared

tables and approved the final draft. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Thandra KC, Barsouk A, Saginala K, Padala

SA, Barsouk A and Rawla P: Epidemiology of non-hodgkin's lymphoma.

Med Sci (Basel). 9:52021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

de Leval L and Jaffe ES: Lymphoma

classification. Cancer. 26:176–185. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Harrington F, Greenslade M, Talaulikar D

and Corboy G: Genomic characterisation of diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Pathology. 53:367–376. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Opinto G, Vegliante MC, Negri A, Skrypets

T, Loseto G, Pileri SA, Guarini A and Ciavarella S: The tumor

microenvironment of DLBCL in the computational era. Front Oncol.

10:3512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

McCarthy L, Bentley-DeSousa A, Denoncourt

A, Tseng YC, Gabriel M and Downey M: Proteins required for vacuolar

function are targets of lysine polyphosphorylation in yeast. FEBS

Lett. 594:21–30. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kanduc D: The role of proteomics in

defining autoimmunity. Expert Rev Proteomics. 18:177–184. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liang XJ, Song XY, Wu JL, Liu D, Lin BY,

Zhou HS and Wang L: Advances in multi-omics study of prognostic

biomarkers of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Biol Sci.

18:1313–1327. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Stegemann M, Denker S and Schmitt CA:

DLBCL 1L-what to expect beyond R-CHOP? Cancers (Basel).

14:14532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

McArdle AJ and Menikou S: What is

proteomics? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 106:178–181. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Punetha A and Kotiya D: Advancements in

oncoproteomics technologies: Treading toward translation into

clinical practice. Proteomes. 11:22023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Huang Z, Ma L, Huang C, Li Q and Nice EC:

Proteomic profiling of human plasma for cancer biomarker discovery.

Proteomics. 17:2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kothalawala WJ, Barták BK, Nagy ZB,

Zsigrai S, Szigeti KA, Valcz G, Takács I, Kalmár A and Molnár B: A

detailed overview about the single-cell analyses of solid tumors

focusing on colorectal cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 28:16103422022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gao HX, Li SJ, Niu J, Ma ZP, Nuerlan A,

Xue J, Wang MB, Cui WL, Abulajiang G, Sang W, et al: TCL1 as a hub

protein associated with the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma based on proteomics methods. Pathol Res

Pract. 216:1527992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bingham GC, Lee F, Naba A and Barker TH:

Spatial-omics: Novel approaches to probe cell heterogeneity and

extracellular matrix biology. Matrix Biol. 91-92:152–166. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ednersson SB, Stern M, Fagman H,

Nilsson-Ehle H, Hasselblom S, Thorsell A and Andersson PO:

Proteomic analysis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identifies

dysregulated tumor microenvironment proteins in non-GCB/ABC subtype

patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 62:2360–2373. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhuang K, Zhang Y, Mo P, Deng L, Jiang Y,

Yu L, Mei F, Huang S, Chen X, Yan Y, et al: Plasma proteomic

analysis reveals altered protein abundances in HIV-infected

patients with or without non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Med Virol.

94:3876–3889. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ysebaert L, Quillet-Mary A, Tosolini M,

Pont F, Laurent C and Fournié JJ: Lymphoma heterogeneity unraveled

by single-cell transcriptomics. Front Immunol. 12:5976512021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jiang M, Bennani NN and Feldman AL:

Lymphoma classification update: T-cell lymphomas, Hodgkin

lymphomas, and histiocytic/dendritic cell neoplasms. Expert Rev

Hematol. 10:239–249. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang J, Gu Y and Chen B: Drug-resistance

mechanism and new targeted drugs and treatments of relapse and

refractory DLBCL. Cancer Manag Res. 15:245–225. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu Y, Zeng L, Zhang S, Zeng S, Huang J,

Tang Y and Zhong M: Identification of differentially expressed

proteins in chemotherapy-sensitive and chemotherapy-resistant

diffuse large B cell lymphoma by proteomic methods. Med Oncol.

30:5282013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xie M, Huang X, Ye X and Qian W:

Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of PD-1/PD-L1

expression in the tumor microenvironment and neoplastic cells for

lymphoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 77:1059992019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Steen CB, Luca BA, Esfahani MS, Azizi A,

Sworder BJ, Nabet BY, Kurtz DM, Liu CL, Khameneh F, Advani RH, et

al: The landscape of tumor cell states and ecosystems in diffuse

large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 39:1422–37.e10. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cioroianu AI, Stinga PI, Sticlaru L,

Cioplea MD, Nichita L, Popp C and Staniceanu F: Tumor

microenvironment in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: role and

prognosis. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2019:85863542019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ceccato J, Piazza M, Pizzi M, Manni S,

Piazza F, Caputo I, Cinetto F, Pisoni L, Trojan D, Scarpa R, et al:

A bone-based 3D scaffold as an in-vitro model of

microenvironment-DLBCL lymphoma cell interaction. Front Oncol.

12:9478232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

de Groot FA, de Groen RAL, van den Berg A,

Jansen PM, Lam KH, Mutsaers PGNJ, van Noesel CJM, Chamuleau MED,

Stevens WBC, Plaça JR, et al: Biological and clinical implications

of gene-expression profiling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A

proposal for a targeted BLYM-777 consortium panel as part of a

multilayered analytical approach. Cancers (Basel). 14:18572022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Takahara T, Nakamura S, Tsuzuki T and

Satou A: The immunology of DLBCL. Cancers (Basel). 15:8352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ofori K, Bhagat G and Rai AJ: Exosomes and

extracellular vesicles as liquid biopsy biomarkers in diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma: Current state of the art and unmet clinical needs.

Brit J Clin Pharmaco. 87:284–294. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu X, Zhao X, Yang J, Wang H, Piao Y and

Wang L: High expression of AP2M1 correlates with worse prognosis by

regulating immune microenvironment and drug resistance to R-CHOP in

diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 110:198–208. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ejtehadifar M, Zahedi S, Gameiro P,

Cabeçadas J, da Silva MG, Beck HC, Carvalho AS and Matthiesen R:

Meta-analysis of MS-based proteomics studies indicates interferon

regulatory factor 4 and nucleobindin1 as potential prognostic and

drug resistance biomarkers in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cells.

12:1962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ma J, Pang X, Li J, Zhang W and Cui W: The

immune checkpoint expression in the tumor immune microenvironment

of DLBCL: Clinicopathologic features and prognosis. Front Oncol.

12:10693782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kotlov N, Bagaev A, Revuelta MV, Phillip

JM, Cacciapuoti MT, Antysheva Z, Svekolkin V, Tikhonova E,

Miheecheva N, Kuzkina N, et al: Clinical and biological subtypes of

B-cell lymphoma revealed by microenvironmental signatures. Cancer

Discov. 11:1468–1489. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bouwstra R, He Y, de Boer J, Kooistra H,

Cendrowicz E, Fehrmann RSN, Ammatuna E, Zu Eulenburg C, Nijland M,

Huls G, et al: CD47 Expression defines efficacy of rituximab with

CHOP in non-germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma patients (DLBCL), but not in GCB DLBCL. Cancer Immunol

Res. 7:1663–1671. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Xu-Monette ZY, Wei L, Fang X, Au Q, Nunns

H, Nagy M, Tzankov A, Zhu F, Visco C, Bhagat G, et al: Genetic

subtyping and phenotypic characterization of the immune

microenvironment and MYC/BCL2 double expression reveal

heterogeneity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res.

28:972–983. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Feng Y, Zhong M, Tang Y, Liu X, Liu Y,

Wang L and Zhou H: The role and underlying mechanism of exosomal

CA1 in chemotherapy resistance in diffuse large B cell lymphoma.

Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 21:452–463. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Klein C, Jamois C and Nielsen T: Anti-CD20

treatment for B-cell malignancies: Current status and future

directions. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 21:161–181. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Poletto S, Novo M, Paruzzo L, Frascione

PMM and Vitolo U: Treatment strategies for patients with diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 110:1024432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Susanibar-Adaniya S and Barta SK: 2021

Update on diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A review of current data

and potential applications on risk stratification and management.

Am J Hematol. 96:617–629. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Roider T, Seufert J, Uvarovskii A,

Frauhammer F, Bordas M, Abedpour N, Stolarczyk M, Mallm JP, Herbst

SA, Bruch PM, et al: Dissecting intratumour heterogeneity of nodal

B-cell lymphomas at the transcriptional, genetic and drug-response

levels. Nat Cell Biol. 22:896–906. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ferreri AJM, Doorduijn JK, Re A, Cabras

MG, Smith J, Ilariucci F, Luppi M, Calimeri T, Cattaneo C, Khwaja

J, et al: MATRix-RICE therapy and autologous haematopoietic

stem-cell transplantation in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with

secondary CNS involvement (MARIETTA): An international, single-arm,

phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 8:e110–e121. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yan J, Yuan W, Zhang J, Li L, Zhang L,

Zhang X and Zhang M: Identification and validation of a prognostic

prediction model in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13:8463572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Stanwood SR, Chong LC, Steidl C and

Jefferies WA: Distinct gene expression patterns of calcium channels

and related signaling pathways discovered in lymphomas. Front

Pharmacol. 13:7951762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Frontzek F, Karsten I, Schmitz N and Lenz

G: Current options and future perspectives in the treatment of

patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Ther Adv Hematol. 13:204062072211033212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li S, Young KH and Medeiros LJ: Diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma. Pathology. 50:74–87. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Gao HX, Nuerlan A, Abulajiang G, Cui WL,

Xue J, Sang W, Li SJ, Niu J, Ma ZP, Zhang W and Li XX: Quantitative

proteomics analysis of differentially expressed proteins in

activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using

quantitative proteomics. Pathol Res Pract. 215:1525282019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Robotti E, Calà E and Marengo E:

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis image analysis. Methods Mol

Biol. 2361:3–13. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Rotello RJ and Veenstra TD: Mass

spectrometry techniques: Principles and practices for quantitative

proteomics. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 22:121–133. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yang J, Li Y, Zhang Y, Fang X, Chen N,

Zhou X and Wang X: Sirt6 promotes tumorigenesis and drug resistance

of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by mediating PI3K/Akt signaling. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:1422020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang X, Duan YT, Wang Y, Zhao XD, Sun YM,

Lin DZ, Chen Y, Wang YX, Zhou ZW, Liu YX, et al: SAF-248, a novel

PI3Kδ-selective inhibitor, potently suppresses the growth of

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 43:209–219.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Chen CC, Hsu CC, Chen SL, Lin PH, Chen JP,

Pan YR, Huang CE, Chen YJ, Chen YY, Wu YY and Yang MH: RAS mediates

BET inhibitor-endued repression of lymphoma migration and

prognosticates a novel proteomics-based subgroup of DLBCL through

its negative regulator IQGAP3. Cancers (Basel). 13:50242021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wang N, Wu R, Tang D and Kang R: The BET

family in immunity and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

6:232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Sun F, Fang X and Wang X: Signal pathways

and therapeutic prospects of diffuse large B cell lymphoma.

Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 19:2047–2059. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Xu W, Berning P and Lenz G: Targeting

B-cell receptor and PI3K signaling in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Blood. 138:1110–1119. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Dunleavy K, Erdmann T and Lenz G:

Targeting the B-cell receptor pathway in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 65:41–46. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Bisserier M and Wajapeyee N: Mechanisms of

resistance to EZH2 inhibitors in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.

Blood. 131:2125–2137. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Coronado BNL, da Cunha FBS, de Toledo

Nobrega O and Martins AMA: The impact of mass spectrometry

application to screen new proteomics biomarkers in ophthalmology.

Int Ophthalmol. 41:2619–2633. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Dallavalasa S, Beeraka NM, Basavaraju CG,

Tulimilli SV, Sadhu SP, Rajesh K, Aliev G and Madhunapantula SV:

The role of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) in cancer

progression, chemoresistance, angiogenesis and metastasis-current

status. Curr Med Chem. 28:8203–8236. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kelly RT: Single-cell proteomics: Progress

and prospects. Mol Cell Proteomics. 19:1739–1748. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Hasin Y, Seldin M and Lusis A: Multi-omics

approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 18:832017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Wang L, Li LR and Young KH: New agents and

regimens for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol.

13:1752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Xiong J, Cui BW, Wang N, Dai YT, Zhang H,

Wang CF, Zhong HJ, Cheng S, Ou-Yang BS, Hu Y, et al: Genomic and

transcriptomic characterization of natural killer T cell lymphoma.

Cancer Cell. 37:403–419.e6. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

van der Meeren LE, Kluiver J, Rutgers B,

Alsagoor Y, Kluin PM, van den Berg A and Visser L: A super-SILAC

based proteomics analysis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma-NOS

patient samples to identify new proteins that discriminate GCB and

non-GCB lymphomas. PLoS One. 14:e02232602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhang P and Zhang M: Epigenetic

alterations and advancement of treatment in peripheral T-cell

lymphoma. Clin Epigenetics. 12:1692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Jiang H, Li A, Ji Z, Tian M and Zhang H:

Role of radiomics-based baseline PET/CT imaging in lymphoma:

Diagnosis, prognosis, and response assessment. Mol Imaging Biol.

24:537–549. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Fornecker LM, Muller L, Bertrand F, Paul

N, Pichot A, Herbrecht R, Chenard MP, Mauvieux L, Vallat L, Bahram

S, et al: Multi-omics dataset to decipher the complexity of drug

resistance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Sci Rep. 9:8952019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Bresnick AR, Weber DJ and Zimmer DB: S100

proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 15:96–109. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ye X, Wang L, Nie M, Wang Y, Dong S, Ren

W, Li G, Li ZM, Wu K and Pan-Hammarström Q: A single-cell atlas of

diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cell Rep. 39:1107132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Wang N, Li X, Wang R and Ding Z: Spatial

transcriptomics and proteomics technologies for deconvoluting the

tumor microenvironment. Biotechnol J. 16:e21000412021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Cumming IA, Degorce SL, Aagaard A,

Braybrooke EL, Davies NL, Diène CR, Eatherton AJ, Felstead HR,

Groombridge SD, Lenz EM, et al: Identification and optimisation of

a pyrimidopyridone series of IRAK4 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem.

63:1167292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Yoon SB, Hong H, Lim HJ, Choi JH, Choi YP,

Seo SW, Lee HW, Chae CH, Park WK, Kim HY, et al: A novel IRAK4/PIM1

inhibitor ameliorates rheumatoid arthritis and lymphoid malignancy

by blocking the TLR/MYD88-mediated NF-κB pathway. Acta Pharm Sin B.

13:1093–1109. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Zhang J, Fu L, Shen B, Liu Y, Wang W, Cai

X, Kong L, Yan Y, Meng R, Zhang Z, et al: Assessing IRAK4 functions

in ABC DLBCL by IRAK4 kinase inhibition and protein degradation.

Cell Chem Biol. 27:1500–1509.e13. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Boșoteanu M, Cristian M, Așchie M, Deacu

M, Mitroi AF, Brînzan CS and Bălțătescu GI: Proteomics and genomics

of a monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma: An

extremely rare case report and short review of literature. Medicine

(Baltimore). 101:e319512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Coradduzza D, Ghironi A, Azara E, Culeddu

N, Cruciani S, Zinellu A, Maioli M, De Miglio MR, Medici S, Fozza C

and Carru C: Role of polyamines as biomarkers in lymphoma patients:

A pilot study. Diagnostics (Basel). 12:21512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Cheson BD, Nowakowski G and Salles G:

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: New targets and novel therapies.

Blood Cancer J. 11:682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Rolland DCM, Basrur V, Jeon YK,

McNeil-Schwalm C, Fermin D, Conlon KP, Zhou Y, Ng SY, Tsou CC,

Brown NA, et al: Functional proteogenomics reveals biomarkers and

therapeutic targets in lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

114:6581–6586. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Huang L, Brunell D, Stephan C, Mancuso J,

Yu X, He B, Zinner R, Kim J, Davies P and Wong STC: Driver network

as a biomarker: systematic integration and network modeling of

multi-omics data to derive driver signaling pathways for drug

combination prediction. Bioinformatics. 35:3709–3717. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Chakraborty S, Hosen MI, Ahmed M and

Shekhar HU: Onco-multi-OMICS approach: A new frontier in cancer

research. Biomed Res Int. 2018:98362562018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Gohil SH, Iorgulescu JB, Braun DA, Keskin

DB and Livak KJ: Applying high-dimensional single-cell technologies

to the analysis of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

18:244–256. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Yang D, Wang J, Hu M, Li F, Yang F, Zhao

Y, Xu Y and Zhang X, Tang L and Zhang X: Combined multiomics

analysis reveals the mechanism of CENPF overexpression-mediated

immune dysfunction in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in vitro. Front

Genet. 13:10726892022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Landeira-Viñuela A, Diez P, Juanes-Velasco

P, Lécrevisse Q, Orfao A, De Las Rivas J and Fuentes M: Deepening

into intracellular signaling landscape through integrative spatial

proteomics and transcriptomics in a lymphoma model. Biomolecules.

11:17762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Jamil MO and Mehta A: Diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma: Prognostic markers and their impact on therapy. Expert

Rev Hematol. 9:471–477. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Maurer MJ, Micallef INM, Cerhan JR,

Katzmann JA, Link BK, Colgan JP, Habermann TM, Inwards DJ, Markovic

SN, Ansell SM, et al: Elevated serum free light chains are

associated with event-free and overall survival in two independent

cohorts of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin

Oncol. 29:1620–1626. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Witzig TE, Maurer MJ, Stenson MJ, Allmer

C, Macon W, Link B, Katzmann JA and Gupta M: Elevated serum

monoclonal and polyclonal free light chains and interferon

inducible protein-10 predicts inferior prognosis in untreated

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 89:417–422. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Grünwald BT, Devisme A, Andrieux G, Vyas

F, Aliar K, McCloskey CW, Macklin A, Jang GH, Denroche R, Romero

JM, et al: Spatially confined sub-tumor microenvironments in

pancreatic cancer. Cell. 184:5577–5592.e18. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Akhtar M, Haider A, Rashid S and Al-Nabet

ADMH: Paget's ‘seed and soil’ theory of cancer metastasis: An idea

whose time has come. Adv Anat Pathol. 26:69–74. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Cords L, Tietscher S, Anzeneder T,

Langwieder C, Rees M, de Souza N and Bodenmiller B:

Cancer-associated fibroblast classification in single-cell and

spatial proteomics data. Nat Commun. 14:42942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Franciosa G, Kverneland AH, Jensen AWP,

Donia M and Olsen JV: Proteomics to study cancer immunity and

improve treatment. Semin Immunopathol. 45:241–251. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Gatto L, Breckels LM and Lilley KS:

Assessing sub-cellular resolution in spatial proteomics

experiments. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 48:123–149. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Liu X, Salokas K, Tamene F, Jiu Y,

Weldatsadik RG, Öhman T and Varjosalo M: An AP-MS- and

BioID-compatible MAC-tag enables comprehensive mapping of protein

interactions and subcellular localizations. Nat Commun. 9:11882018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Pankow S, Martínez-Bartolomé S, Bamberger

C and Yates JR: Understanding molecular mechanisms of disease

through spatial proteomics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 48:19–25. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Guilliams M, Bonnardel J, Haest B,

Vanderborght B, Wagner C, Remmerie A, Bujko A, Martens L, Thoné T,

Browaeys R, et al: Spatial proteogenomics reveals distinct and

evolutionarily conserved hepatic macrophage niches. Cell.

185:379–396.e38. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Lee PY, Saraygord-Afshari N and Low TY:

The evolution of two-dimensional gel electrophoresis-from

proteomics to emerging alternative applications. J Chromatogr A.

1615:4607632020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Strohkamp S, Gemoll T and Habermann JK:

Possibilities and limitations of 2DE-based analyses for identifying

low-abundant tumor markers in human serum and plasma. Proteomics.

16:2519–2532. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Lin TT, Zhang T, Kitata RB, Liu T, Smith

RD, Qian WJ and Shi T: Mass spectrometry-based targeted proteomics

for analysis of protein mutations. Mass Spectrom Rev. 42:796–821.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Noor Z, Ahn SB, Baker MS, Ranganathan S

and Mohamedali A: Mass spectrometry-based protein identification in

proteomics-a review. Brief Bioinform. 22:1620–1638. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Ren AH, Diamandis EP and Kulasingam V:

Uncovering the depths of the human proteome: Antibody-based

technologies for ultrasensitive multiplexed protein detection and

quantification. Mol Cell Proteomics. 20:1001552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Syu GD, Dunn J and Zhu H: Developments and

applications of functional protein microarrays. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 19:916–927. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|