Introduction

Lymphoma, a malignant hematological tumor that

originates from the lymph nodes or other lymphoid tissues, is

mainly divided into Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)

subgroups. Collectively, B-cell lymphoma is the most important

subgroup of NHL, which causes significant clinical challenges

because of heterogeneity and frequent recurrence (1). The programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1) receptor and its ligand, PD-L1, play a pivotal role in the

tumor immune escape mechanism. Immune checkpoint therapy targeting

PD-1 and PD-L1 has received regulatory approval for the treatment

of specific malignancies, including hematological malignancies

(2). PD-1 blockade has demonstrated

notable efficacy in recovering T-cell activation in various

malignancies, including melanoma, gastric carcinoma, lung cancer

and Hodgkin lymphoma (3–9). This immunotherapeutic approach

capitalizes on the body's own immune system to combat cancer cells;

however, most patients with B-cell lymphoma have no response to

PD-1 blockade therapy. The reasons for the poor clinical efficacy

of PD-1 blockade in B-cell lymphoma remain indistinct; therefore,

drug screening that improves the response to PD-1 blocking

therapies is a challenge for B-cell lymphoma.

Histone acetylation is regulated by the homeostasis

of histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs).

HDAC expression is frequently dysregulated in numerous types of

cancer, including B-cell lymphoma (10–12).

HDACs are categorized into four classes based on their structure,

mechanism and cellular localization (13): Class I (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, HDAC8),

Class IIa (HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC7, HDAC9), Class IIb (HDAC6, HDAC10)

and Class IV (HDAC11). Altered HDAC activity is associated with

neurodegenerative disorders, genetic diseases and cancer (14–16).

In cancer, HDAC overexpression is correlated with poor outcomes,

and can contribute to the development and progression of

hematological malignancies, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia,

acute myeloid leukemia and chronic myeloid leukemia (13). A total of four HDAC inhibitors

(HDACis), belinostat, vorinostat, panobinostat and romidepsin, have

been applied in hematological cancers (17,18).

Previous studies have illustrated that HDACis can heighten tumor

immunogenicity (19,20). In recent years, the pursuit of novel

HDACis has been unwavering, leading to significant progress. Wu

et al (21) examined

chidamide, an innovative HDACi, to ascertain its therapeutic

efficacy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), offering a

scientific basis for targeting HDACs in such patients.

Bioinformatics analyses coupled with experimental data have

revealed notably elevated expression levels of several HDACs

(HDAC1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 and 9) in DLBCL lymph node samples

relative to whole blood cell controls. Furthermore, the mutation

frequency of HDACs in DLBCL tissues has been shown to be amplified.

Targeting HDACs with selective inhibitors, such as chidamide,

presents a prospective therapeutic strategy for patients with DLBCL

(21). HDACi drugs are a novel

class of antitumor drugs that regulate gene expression and cellular

function by inhibiting the activity of HDACis (22). Although no HDACi drugs are currently

available specifically for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma in the

clinic, available research has suggested that this class of drugs

shows promising efficacy and potential in the treatment of other

types of tumors. In 2006, the first HDACi was approved by the Food

and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell

lymphoma, namely SAHA (vorinostat) (23). After SAHA, three other HDACis were

approved by the FDA (24). Studying

HDACi drugs for B-cell lymphoma treatment is significant as it

allows initial exploration of their mechanism, assessing their

therapeutic potential and safety. Understanding their impact on

tumor cell processes, such as proliferation, differentiation and

apoptosis, provides a scientific basis for new therapeutic

strategies.

Based on the current research, the following

hypothesis was proposed: The synergistic effects of HDACis with

PD-1 blockade therapies may improve efficacy in B-cell lymphoma.

Romidepsin is an oral selective HDACi that primarily inhibits HDAC1

and HDAC2 activity. It is widely used to treat specific types of

lymphoma and other blood cancers, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (25). BMS-1 is a monoclonal antibody that

targets the PD-1 receptor, blocking its interaction with PD-L1 and

PD-L2; this disruption renews the T cell-mediated immune response,

particularly against tumor cells expressing PD-L1 (26). However, their role in B-cell

lymphoma cells is not yet fully understood. Therefore, the present

study investigated the combined therapeutic potential of romidepsin

and BMS-1 in B-cell lymphoma and its preliminary mechanism of

action through in vivo experiments, aiming to improve the

treatment of this type of lymphoma, and to provide a theoretical

basis and a new therapeutic strategy for future clinical

application.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Mouse B-cell lymphoma cell lines are often

considered a valid model to study human lymphomas because they have

similar biological properties. As there are currently no HDACi

drugs specifically approved for the treatment of B-cell lymphomas,

the present study aimed to use this relatively simple and

controlled model for initial testing to explore new drug

candidates. The mouse B-cell lymphoma A20 cell line (cat. no.

TIB-208) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection,

and was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 11875093) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no.

10099141C) and penicillin/streptomycin (Biosharp Life Sciences;

cat. no. BL505A) in a humidified incubator containing 5%

CO2 at 37°C.

MTT assay

To analyze the effects of individual inhibitors and

their combination on the proliferation of A20 cells, the MTT assay

was employed. Briefly, A20 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at

a suitable density of 5×103 cells/well, along with

appropriate controls. Different concentrations of romidepsin (0, 1,

2, 5, 10 and 20 µM) or BMS-1 (0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 and 15 nM)

(purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.)

were added for treatment, with at least three replicates for each

concentration. After incubation at 37°C for 48 h, 50 µl/well MTT (1

mg/ml; Sigma Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added. Following a 3-h

incubation, DMSO (150 µl/well; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

was added and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a

solution mixture. Dose-response curves were plotted based on the

results. IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad

Prism.

Isograft mouse model

A total of 32 Balb/c mice (female; age, 4 weeks;

weight, 20 g), which are widely used in animal experiments in

immunology and physiology, were purchased from Charles River

Bio-company, and were adaptively maintained in the indicated

environment (pathogen-free, 12-h light/dark cycle, 22°C). Mouse

B-cell lymphoma A20 isografts were established by the intradermal

injection of logarithmic growth phase A20 cells (1×107

cells/ml, 200 µl, 2×106/per mice) into the right flank.

A total of 1 week after the injection, by which time the mice were

tumor-bound, the mice were randomly divided into four groups

(n=8/group), and were administered saline (control), BMS-1 (500

µg/ml; 100 µl/each), romidepsin (1 mg/kg body weight), or a

combination of both drugs daily for 19 days. Tumor size was

measured using a micrometer caliper. Tumor volume (V,

mm3) was calculated every 2 days using the following

formula: V=(a × b2)/2, where a refers to the longest

diameter and b to the shortest diameter. When the volume of the

tumor reached 1,500 mm3, the mice were euthanized by

cervical dislocation. Once it was confirmed that the mice showed no

signs of life (that is, there was no chest movement, and the

eyelids were pale with no visual response), tumors were collected

to measure the volume. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. In

addition, the body weight of each mouse was measured to evaluate

the toxicity of the treatment on the mice. Before sacrifice,

peripheral blood from each mouse was collected to obtain serum and

to detect IFN-γ levels using an ELISA kit (cat. no. MM-0182M1;

http://www.mmbio.cn/goods.php?id=989), according to

the manufacturer's instructions. In addition, the collected tumor

tissues were fixed with formalin and embedded in paraffin. All

animal studies were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou

Medical College (approval no. 2021-246; Hangzhou, China), and were

conducted according to the AAALAC and the IACUC guidelines.

Immunofluorescence analysis of mouse

tissue

Mouse tissues (5 µm) were deparaffinized by xylene

(Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 100234192) and

rehydrated. Slices were placed in anhydrous ethanol (Sinopharm

Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 100092680) for 5 min (repeated

3 times). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3%

hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was

carried out for all sections by incubating them in a steamer with

0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 30 min. Secondly,

CD3-FITC + CD4-PE antibodies and CD3-FITC + CD8-PE antibodies (all

obtained from Abcam; CD3 antibody, cat. no. ab33429; 1:100; CD4

antibody, cat. no. ab288724; 1:100; and CD8 antibody, cat. no.

ab316778; 1:200) were diluted with BSA (cat. no. A8020; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) to a concentration of

1:100, and were used to incubate the sections at 4°C overnight.

Finally, 10 µg/ml DAPI (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was

applied for 5 min and the sections were visualized under a

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). The number of

positive cells was examined using ImageJ software (National

Institutes of Health).

TUNEL assay for cell apoptosis

After deparaffinization, tumor tissue sections were

subjected to TUNEL staining assay for apoptotic cell detection.

Briefly, after gently washing with phosphate-buffered saline, the

sections were incubated in 70% ethanol for 30 min at 4°C. The

subsequent analysis was performed using a commercially available

TUNEL assay kit (cat. no. ab206386; Abcam), according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The data were further visualized under a

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation) and were analyzed

using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. All

statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0

(GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics) and SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Inc.)

software packages. Statistical significance was determined using

two-way ANOVA or one-way ANOVA for multiple groups, and Tukey's

Honestly Significant Difference was used for the post-hoc test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Combined use of romidepsin and BMS-1

produces a synergistic effect in inhibiting lymphoma growth

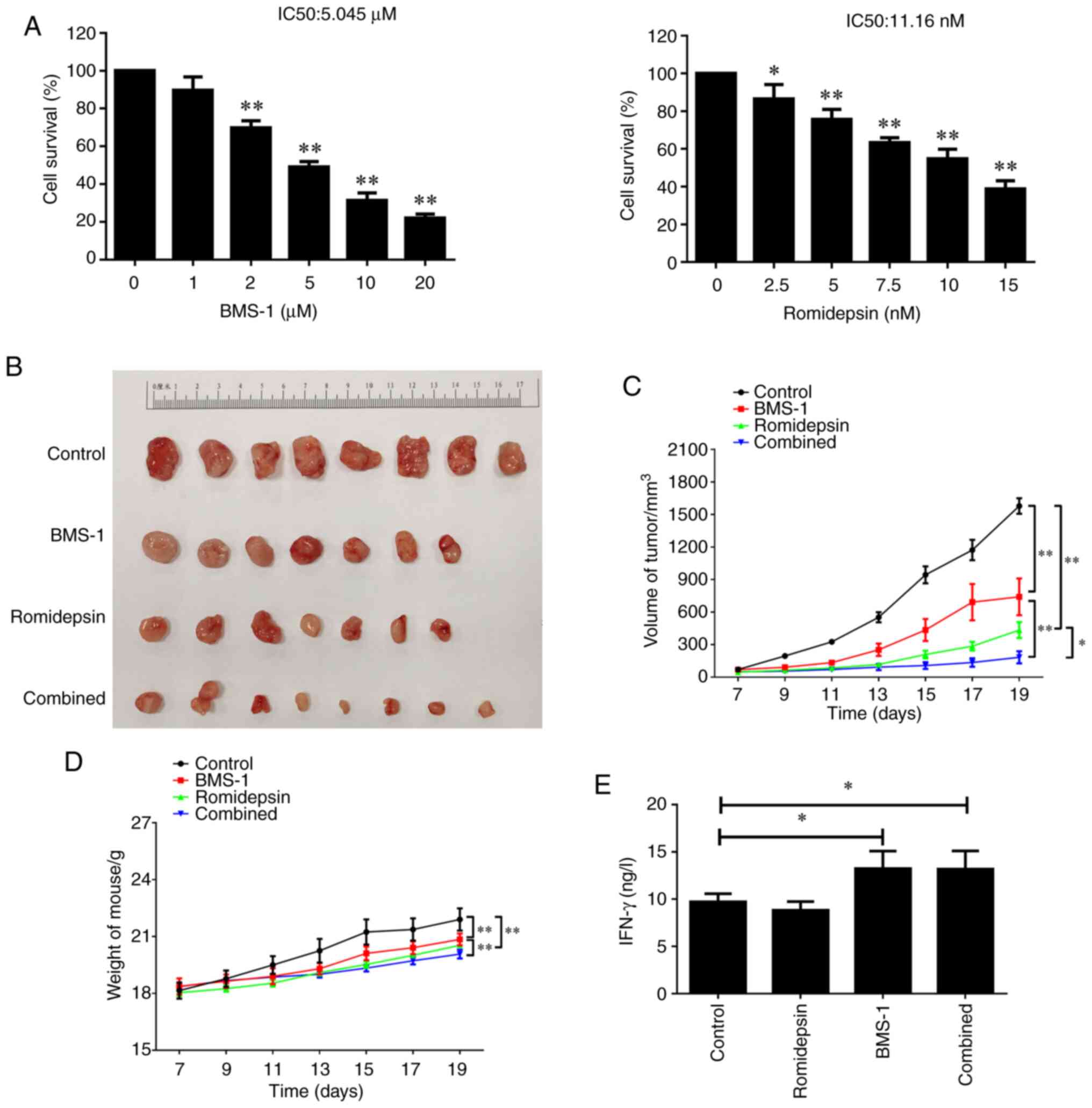

To investigate the effects of a HDACi (romidepsin)

and PD-1 blockade (BMS-1) on lymphoma, the mouse B-cell lymphoma

A20 isografts were established. First, the MTT assay confirmed that

both single-drug treatments impacted the proliferative capacity of

A20 cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. The IC50

values for BMS-1 and romidepsin were 5.045 µM and 11.16 nM,

respectively (Fig. 1A). In the

preliminary experiment, the inhibitory effect of the two inhibitors

on tumor growth was time- and dose-dependent (Fig. S1). As revealed in Fig. 1B and C, both romidepsin and BMS-1,

when administered individually, could exert a certain impact on

tumor growth and tumor volume compared with the control group.

Furthermore, the combination of romidepsin and PD-1 blockade more

significantly reduced tumor growth and tumor volume than that in

the groups treated with romidepsin and PD-1 blockade alone, with

more than a 5-fold decrease in their tumor volume after 19 days

compared with in the control group. In addition, the body weights

of the combination group were lighter than those in the other

groups as time progressed (Fig.

1D). Furthermore, the tissues treated with BMS-1 or in

combination with romidepsin significantly elevated the levels of

IFN-γ, a T-cell biomarker (27),

while romidepsin alone had no significant effect on serum IFN-γ

levels detected by ELISA at the end of the experiment (Fig. 1E). The results suggested that

romidepsin and BMS-1 treatment synergistically inhibited the growth

of A20 isograft lymphomas, which might be associated with the

action of romidepsin on the activation of T-cell infiltration.

Combination treatment of romidepsin

and BMS-1 increases apoptosis in A20-derived lymphoma

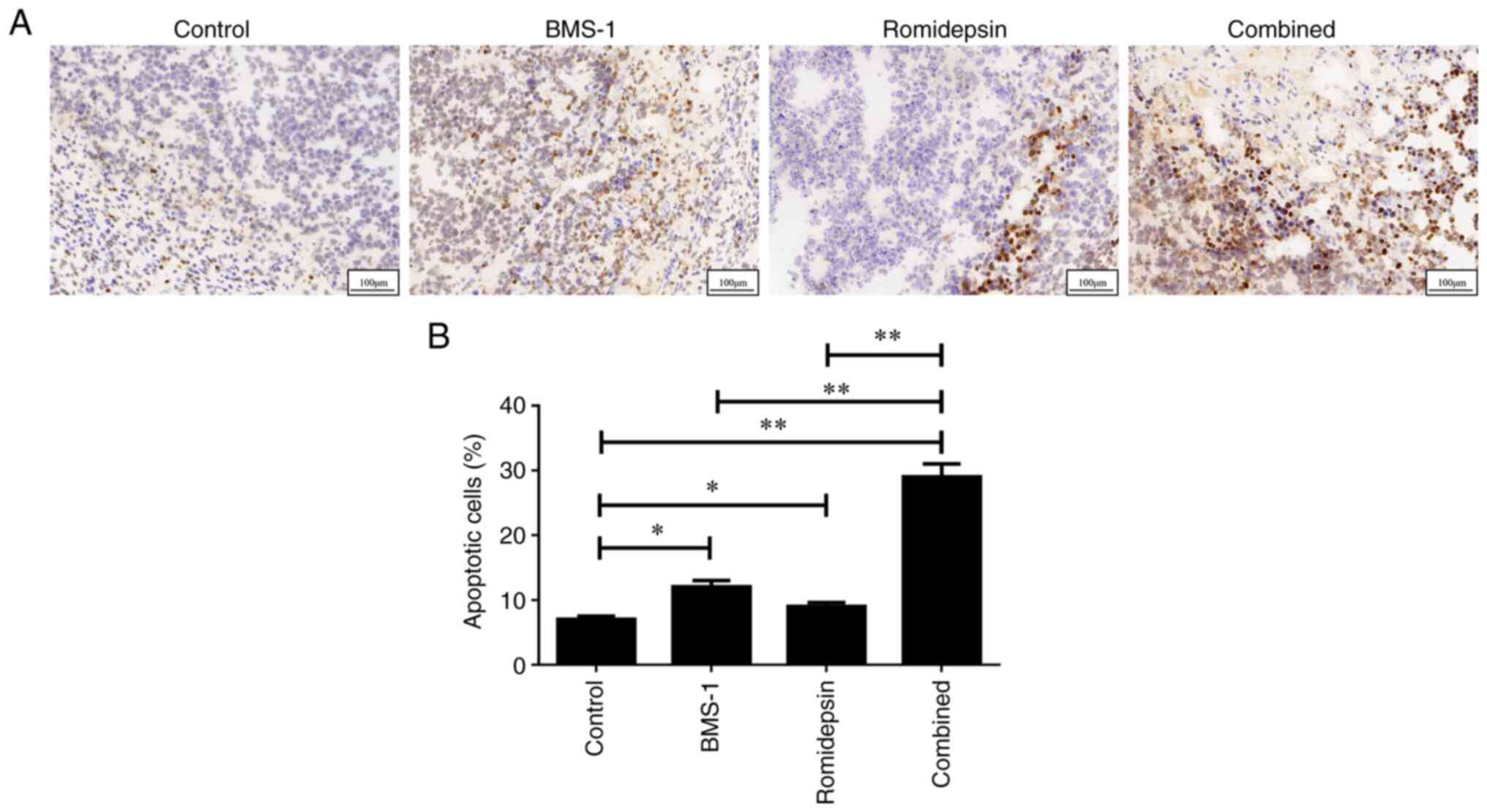

To determine whether apoptosis was required for the

efficacy of the combination treatment, the TUNEL assay was

performed to detect apoptosis in A20 lymphoma mouse tissues. As

shown in Fig. 2A and B, the groups

treated with romidepsin and BMS-1 independently exhibited a

significantly higher induction of apoptosis compared with the

control group. Furthermore, the combination of romidepsin and BMS-1

resulted in a significantly greater enhancement of tumor apoptosis

than when either romidepsin or BMS-1 was used alone. These data

indicated that romidepsin and BMS-1 synergistically triggered

apoptosis in murine B-cell lymphoma.

Combination treatment of romidepsin

and BMS-1 activates the CD4+ and CD8+

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in A20-derived lymphoma

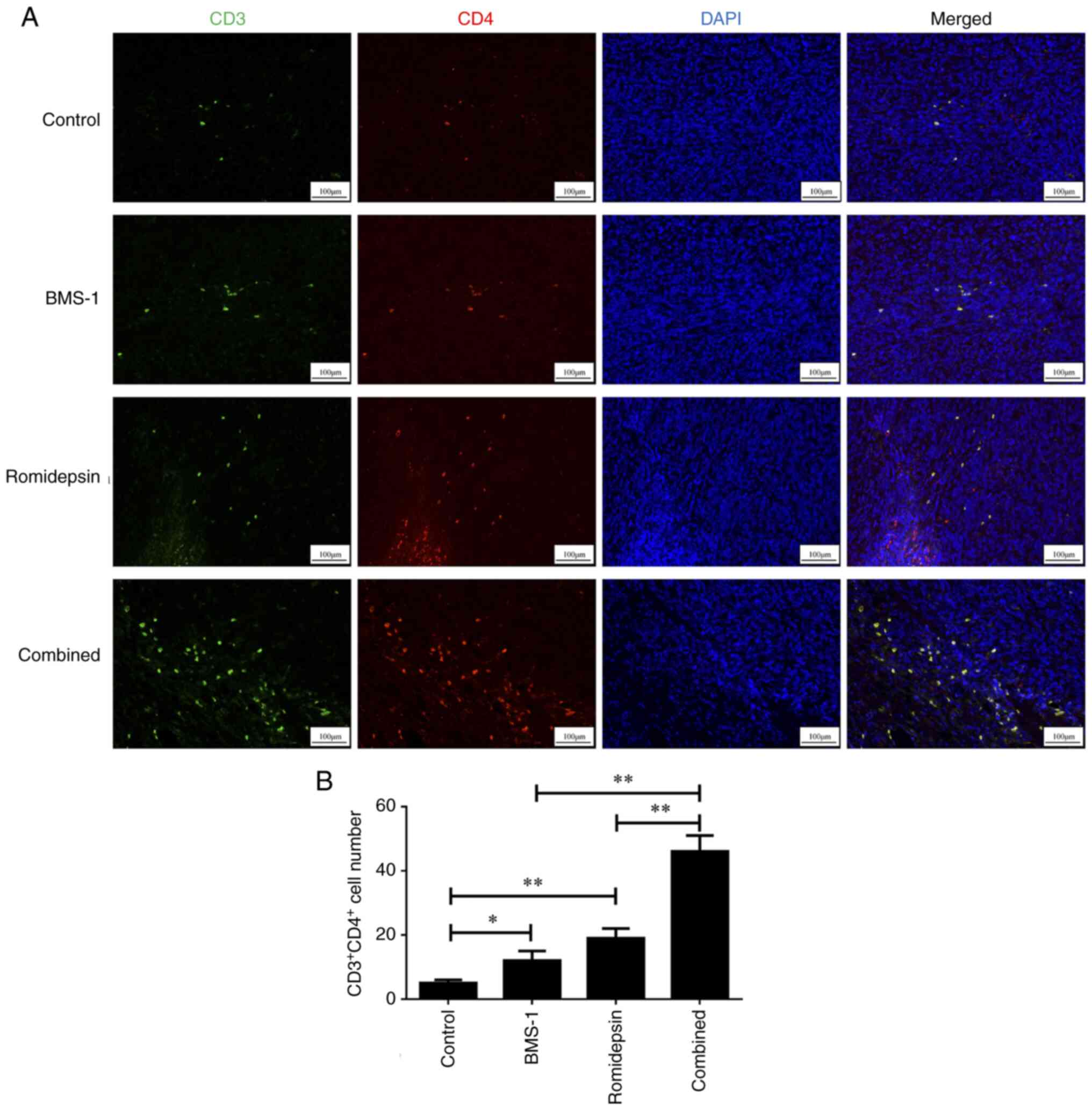

To determine whether CD4+ and

CD8+ TILs were involved in the efficacy of combination

treatment, an immunofluorescence assay was performed to assess the

A20 lymphoma mouse tissues. As demonstrated in Fig. 3A and B, the groups treated only with

romidepsin or BMS-1 showed a significant increase in

CD4+ TILs compared with those in the control group. In

addition, the combination of romidepsin and BMS-1 led to a

significantly greater activation of CD4+ TILs compared

with the groups treated with romidepsin or BMS-1 alone.

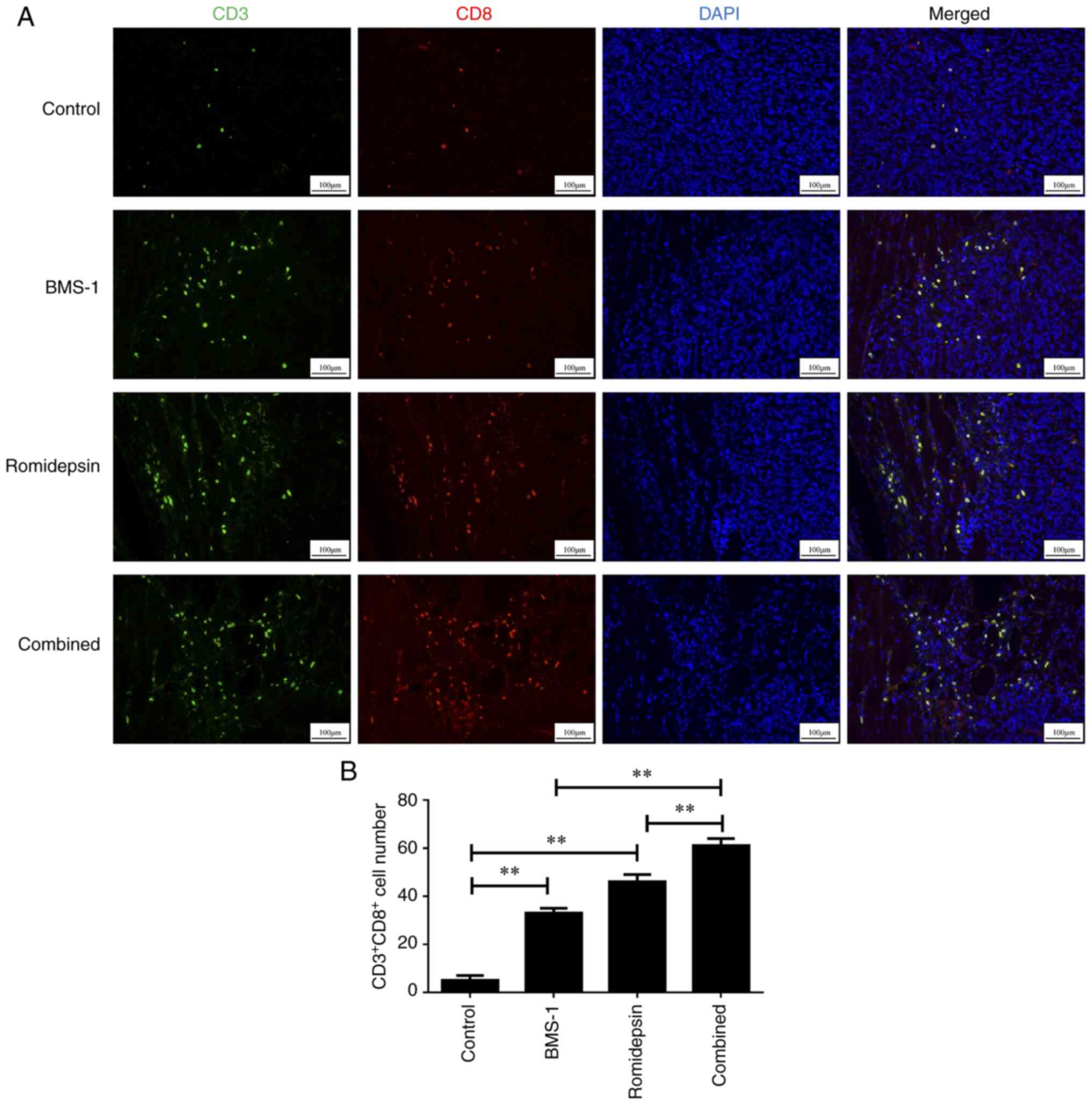

Additionally, as revealed in Fig. 4A

and B, the groups treated with romidepsin and BMS-1 alone

exhibited increased activation of CD8+ TILs compared

with that in the control group. Furthermore, the combination of

romidepsin and BMS-1 more significantly activated CD8+

TILs than that in the groups treated with romidepsin and BMS-1

alone. These data suggested that romidepsin and BMS-1 combination

accelerated CD4+ and CD8+ TILs

activation.

Discussion

Patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma

frequently have a poor prognosis (28); therefore, it is essential to explore

combination therapeutic strategies for B-cell lymphoma. One

mechanism facilitating PD-1 blockade resistance may be reduction of

MHC class I and II expression in cancer (29). MHC molecules present peptides to

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; thus, MHC is

indispensable for the identification of cancer cells by

antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Furthermore, HDACis can upregulate the expression of chemokines

that attract T cells to the tumor microenvironment (TME). By

enhancing the migration of T cells into the TME, HDACis can

synergistically enhance the efficacy of PD-1 blockade, ensuring a

sufficient number of activated T cells are available to interact

with the tumor following inhibition of the PD-1 pathway (30,31).

In the present study, using an intradermal mouse tumor model, it

was found that HDACi and PD1-blockade treatment synergistically

activated CD4+ and CD8+ TILs.

Studies have demonstrated that a portion of HDAC

family members are abnormally expressed in tumors, such as

pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer and ovarian cancer

(32–35). It has been reported that several

HDACis exert potential roles in anticancer immunity (36). For instance, the antitumor effects

of vorinostat are associated with the immune system (37,38).

Inhibitors have also shown promising anticancer outcomes when used

in combination with traditional chemotherapy drugs in tumors

(39,40); however, their role in B-cell

lymphoma cells is not yet fully understood.

The present study examined the therapeutic efficacy

of a combination of a HDACi (romidepsin) and PD-L1 inhibitor

(BMS-1) in the treatment of an A20-induced B-cell lymphoma model.

The findings revealed that both romidepsin and BMS-1 independently

inhibited tumor growth in a dose- and time-dependent manner, and

induced the apoptosis of tumor cells. Furthermore, when used in

combination, there was a significant reduction in tumor growth and

increase in apoptosis, suggesting a synergistic effect. On the one

hand, romidepsin works by inhibiting HDACs, which leads to

hyperacetylation of histones and modulation of gene expression;

this results in cell cycle arrest and the induction of tumor cell

apoptosis (41). However,

romidepsin not only affects gene expression and survival of tumor

cells, but also regulates the immune system. Its ability to enhance

the immune response in the TME may be related to increased

expression of tumor-associated antigens and the modulation of

immune checkpoint molecules. This dual action makes romidepsin a

promising agent in anticancer therapy and immunotherapy (2). On the other hand, BMS-1 functions as a

PD-L1 inhibitor, blocking its interaction with the PD-1 receptor on

T cells. This interference relieves the immune suppression imposed

on T cells by tumor cells expressing PD-L1, thereby enhancing the

immune response against the tumor (26). This is consistent with the present

findings, which demonstrated that the individual administration of

romidepsin and BMS-1 could stimulate CD4+ and

CD8+ TILs in an intradermal mouse tumor model, but that

combining these treatments was more effective.

While the present study shows promising synergy

between romidepsin and BMS-1 in B-cell lymphoma treatment,

providing insights into their combined use in the clinic, several

limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the present study noted

an increase in IFN-γ levels only upon romidepsin administration;

however, the combination of romidepsin and BMS-1 did not

substantially enhance IFN-γ production, which may be due to the

regulation of IFN-γ production by multiple cytokines and signaling

pathways, as well as the existence of complex feedback mechanisms

in the immune system. This will be the direction of our future

research. Secondly, the research focused solely on A20 lymphoma

cells, leaving other B-cell lymphoma subtypes unexplored; varying

responses across subtypes could impact treatment generalizability.

Finally, the longer-term effects and analyses of tumors observed at

various time points after treatment and at different doses of this

combination have not been explored, requiring extensive clinical

trials to confirm chronic outcomes and safety. In conclusion, the

present study highlighted the synergistic effects of a HDACi and

PD-1 blockade on anticancer response, and recommended this

combination therapeutic strategy for the treatment of B-cell

lymphoma.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82174018), the Zhejiang Medical and

Health Science and Technology Project (grant nos. 2022KY470 and

2021KY009) and the Zhejiang TCM Science and Technology Project

(grant no. 2022ZB005).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HJ and YG designed the study. TW and XY performed

experiments and analyzed the data. TW wrote the draft of the

manuscript. TW, XY, HJ and YG confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal studies were performed in compliance with

the regulations and guidelines of Zhejiang Hospital animal care and

conducted according to the AAALAC and the IACUC guidelines. The

present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou

Medical College (approval no. 2021-246; Hangzhou, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Al-Hamadani M, Habermann TM, Cerhan JR,

Macon WR, Maurer MJ and Go RS: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtype

distribution, geodemographic patterns, and survival in the US: A

longitudinal analysis of the National Cancer Data Base from 1998 to

2011. Am J Hematol. 90:790–795. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I,

Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, Schuster SJ, Millenson MM, Cattry

D, Freeman GJ, et al: PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or

refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 372:311–319. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fourcade J, Sun Z, Benallaoua M, Guillaume

P, Luescher IF, Sander C, Kirkwood JM, Kuchroo V and Zarour HM:

Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor

antigen-specific CD8+ T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J

Exp Med. 207:2175–2186. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Shaw G, Cavalcante L, Giles FJ and Taylor

A: Elraglusib (9-ING-41), a selective small-molecule inhibitor of

glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta, reduces expression of immune

checkpoint molecules PD-1, TIGIT and LAG-3 and enhances CD8(+) T

cell cytolytic killing of melanoma cells. J Hematol Oncol.

15:1342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xu C, Xie X, Kang N and Jiang H:

Neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor and apatinib combined with S-1 plus

oxaliplatin for locally advanced gastric cancer patients: A

multicentered, prospective, cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

149:4091–4099. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu J, Wei L, Hu N, Wang D, Ni J, Zhang S,

Liu H, Lv T, Yin J, Ye M and Song Y: FBW7-mediated ubiquitination

and destruction of PD-1 protein primes sensitivity to anti-PD-1

immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer.

10:e0051162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nagai Y, Sata M, Ohta H, Onuki T, Saito T,

Uchiyama A, Kurosaki A, Yoshizumi N, Takigami A, Nakazawa S, et al:

Herpes zoster in patients with lung cancer treated with PD-1/PD-L1

antibodies. Immunotherapy. 14:1211–1217. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jimenez O, Mangiaterra T, Colli S, Garcia

Lombardi M, Preciado MV, De Matteo E and Chabay P: PD-1 and LAG-3

expression in EBV-associated pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma has

influence on survival. Front Oncol. 12:9572082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rossi C and Casasnovas RO: PD-1 inhibitors

in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Cancer. 164:114–116. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zain J and O'Connor OA: Targeting histone

deacetyalses in the treatment of B- and T-cell malignancies. Invest

New Drugs. 28 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1):S58–S78. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Shin DY, Kim A, Kang HJ, Park S, Kim DW

and Lee SS: Histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin induces

efficient tumor cell lysis via selective down-regulation of LMP1

and c-myc expression in EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Cancer Lett. 364:89–97. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yu H, Mi L, Zhang W, Ye Y, Li M, Hu D, Cao

J, Wang D, Wang X, Ding N, et al: Ibrutinib combined with low-dose

histone deacetylases inhibitor chidamide synergistically enhances

the anti-tumor effect in B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol.

40:894–905. 2022. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang P, Wang Z and Liu J: Role of HDACs in

normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Mol Cancer. 19:52020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chuang DM, Leng Y, Marinova Z, Kim HJ and

Chiu CT: Multiple roles of HDAC inhibition in neurodegenerative

conditions. Trends Neurosci. 32:591–601. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Consalvi S, Saccone V, Giordani L, Minetti

G, Mozzetta C and Puri PL: Histone deacetylase inhibitors in the

treatment of muscular dystrophies: Epigenetic drugs for genetic

diseases. Mol Med. 17:457–465. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yang FF, Hu T, Liu JQ, Yu XQ and Ma LY:

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) as the promising immunotherapeutic

targets for hematologic cancer treatment. Eur J Med Chem. 245((Pt

2)): 1149202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Marks PA: The clinical development of

histone deacetylase inhibitors as targeted anticancer drugs. Expert

Opin Investig Drugs. 19:1049–1066. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang L, Wu Z, Xia Y, Lu X, Li J, Fan L,

Qiao C, Qiu H, Gu D, Xu W, et al: Single-cell profiling-guided

combination therapy of c-Fos and histone deacetylase inhibitors in

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Transl Med. 12:e7982022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Llopiz D, Ruiz M, Villanueva L, Iglesias

T, Silva L, Egea J, Lasarte JJ, Pivette P, Trochon-Joseph V,

Vasseur B, et al: Enhanced anti-tumor efficacy of checkpoint

inhibitors in combination with the histone deacetylase inhibitor

Belinostat in a murine hepatocellular carcinoma model. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 68:379–393. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Burke B, Eden C, Perez C, Belshoff A, Hart

S, Plaza-Rojas L, Delos Reyes M, Prajapati K, Voelkel-Johnson C,

Henry E, et al: Inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC) enhances

checkpoint blockade efficacy by rendering bladder cancer cells

visible for T cell-mediated destruction. Front Oncol. 10:6992020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wu C, Song Q, Gao S and Wu S: Targeting

HDACs for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma therapy. Sci Rep.

14:2892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

McClure JJ, Li X and Chou CJ: Advances and

challenges of HDAC inhibitors in cancer therapeutics. Adv Cancer

Res. 138:183–211. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mann BS, Johnson JR, Cohen MH, Justice R

and Pazdur R: FDA approval summary: Vorinostat for treatment of

advanced primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncologist.

12:1247–1252. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Squarzoni A, Scuteri A and Cavaletti G:

HDACi: The columbus' egg in improving cancer treatment and reducing

neurotoxicity? Cancers (Basel). 14:52512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bachy E, Camus V, Thieblemont C, Sibon D,

Casasnovas RO, Ysebaert L, Damaj G, Guidez S, Pica GM, Kim WS, et

al: Romidepsin Plus CHOP Versus CHOP in patients with previously

untreated peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma: Results of the Ro-CHOP phase

III study (Conducted by LYSA). J Clin Oncol. 40:242–251. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tsuruta A, Shiiba Y, Matsunaga N, Fujimoto

M, Yoshida Y, Koyanagi S and Ohdo S: Diurnal Expression of PD-1 on

tumor-associated macrophages underlies the dosing time-dependent

antitumor effects of the PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitor BMS-1 in B16/BL6

Melanoma-Bearing Mice. Mol Cancer Res. 20:972–982. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Boulch M, Cazaux M, Cuffel A, Guerin MV,

Garcia Z, Alonso R, Lemaître F, Beer A, Corre B, Menger L, et al:

Tumor-intrinsic sensitivity to the pro-apoptotic effects of IFN-γ

is a major determinant of CD4(+) CAR T-cell antitumor activity. Nat

Cancer. 4:968–983. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Moleti ML, Testi AM and Foa R: Treatment

of relapsed/refractory paediatric aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin

lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 189:826–843. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ren D, Hua Y, Yu B, Ye X, He Z, Li C, Wang

J, Mo Y, Wei X, Chen Y, et al: Predictive biomarkers and mechanisms

underlying resistance to PD1/PD-L1 blockade cancer immunotherapy.

Mol Cancer. 19:192020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Beg AA and Gray JE: HDAC inhibitors with

PD-1 blockade: A promising strategy for treatment of multiple

cancer types? Epigenomics. 8:1015–1017. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Que Y, Zhang XL, Liu ZX, Zhao JJ, Pan QZ,

Wen XZ, Xiao W, Xu BS, Hong DC, Guo TH, et al: Frequent

amplification of HDAC genes and efficacy of HDAC inhibitor

chidamide and PD-1 blockade combination in soft tissue sarcoma. J

Immunother Cancer. 9:e0016962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Knoche SM, Brumfield GL, Goetz BT, Sliker

BH, Larson AC, Olson MT, Poelaert BJ, Bavari A, Yan Y, Black JD and

Solheim JC: The histone deacetylase inhibitor M344 as a

multifaceted therapy for pancreatic cancer. PLoS One.

17:e02735182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Rahbari R, Rahimi K, Rasmi Y,

Khadem-Ansari MH and Abdi M: miR-589-5p inhibits cell proliferation

by targeting histone deacetylase 3 in triple negative breast

cancer. Arch Med Res. 53:483–491. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

You Q, Wang J, Yu Y, Li F, Meng L, Chen M,

Yang Q, Xu Z, Sun J, Zhuo W and Chen Z: The histone deacetylase

SIRT6 promotes glycolysis through the HIF-1α/HK2 signaling axis and

induces erlotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer.

Apoptosis. 27:883–898. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Pramanik SD, Kumar Halder A, Mukherjee U,

Kumar D, Dey YN and R M: Potential of histone deacetylase

inhibitors in the control and regulation of prostate, breast and

ovarian cancer. Front Chem. 10:9482172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hull EE, Montgomery MR and Leyva KJ: HDAC

inhibitors as epigenetic regulators of the immune system: Impacts

on cancer therapy and inflammatory diseases. Biomed Res Int.

2016:87972062016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

West AC, Mattarollo SR, Shortt J, Cluse

LA, Christiansen AJ, Smyth MJ and Johnstone RW: An intact immune

system is required for the anticancer activities of histone

deacetylase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 73:7265–7276. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Surolia I and Bates SE: Entinostat finds a

path: A new study elucidates effects of the histone deacetylase

inhibitor on the immune system. Cancer. 124:4597–4600. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lu F, Hou L, Wang S, Yu Y, Zhang Y, Sun L,

Wang C, Ma Z and Yang F: Lysosome activable polymeric vorinostat

encapsulating PD-L1KD for a combination of HDACi and immunotherapy.

Drug Deliv. 28:963–972. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wu J, Nie J, Luan Y and Ding Y: Hybrid

histone deacetylase inhibitor: An effective strategy for cancer

therapy. Curr Med Chem. 30:2267–2311. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

El Omari N, Lee LH, Bakrim S, Makeen HA,

Alhazmi HA, Mohan S, Khalid A, Ming LC and Bouyahya A: Molecular

mechanistic pathways underlying the anticancer therapeutic

efficiency of romidepsin. Biomed Pharmacother. 164:1147742023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|