Introduction

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are shed from primary

tumors and circulate in the peripheral blood. CTCs are considered

the origin of metastases, and analyzing CTCs holds the potential

for early metastasis detection and monitoring of therapeutic

effects in malignant tumors (1,2). Among

the available CTC detection devices, CellSearch (Veridex, LLC) is a

semi-automatic system that utilizes antibodies against epithelial

cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), and is the only Food and Drug

Administration (FDA)-approved device for clinical CTC detection

(3). CellSearch consistently yields

reproducible results and demonstrates its clinical relevance in

epithelial cancers (4,5). However, epithelial tumor cells undergo

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to enhance their migration

and invasiveness, resulting in the downregulation of epithelial

markers such as EpCAM (6).

Consequently, EpCAM-dependent systems, including CellSearch, may be

limited in that they cannot capture CTCs undergoing EMT (EMT-CTCs),

which is a pivotal subtype implicated in metastasis (7,8). To

address this limitation, a novel polymeric microfluidic device

‘CTC-chip’ (9) was developed based

on the conventional CTC-chip designed by Nagrath et al

(10). The CTC-chip can capture

diverse types of CTCs expressing targeted tumor cell antigens by

easily attaching various antibodies to numerous microposts on the

chip surface (11–13), and its clinical utility was

previously reported by our group (14,15).

In a previous study by our group, CTCs were undetectable in 40% of

patients with lung cancer and metastases, indicating the need to

develop an EpCAM-independent capture system using other antibodies

(15). Recently, Satelli et

al (16) identified

cell-surface vimentin (CSV) as an EMT-CTC marker. The CSV

monoclonal antibody clone 84-1 primarily associates with tumor

cells and demonstrates clinical utility (17–19).

In the present study, CSV expression was validated in lung and

colon cancer cell lines, and the capture efficiency of this

polymeric CTC-chip coated with an anti-CSV antibody was assessed as

a novel marker for mesenchymal CTCs, with the aim of establishing

an EMT-CTC capture system.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The human lung cancer cell lines PC9 (Riken

BioResource Research Center) and H441 [American Type Culture

Collection (ATCC)], and the human colorectal cancer cell line DLD1

(ATCC) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Wako Pure Chemical

Industries) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The human lung cancer cell line A549

(ATCC) was cultured in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Wako Pure

Chemical Industries) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% non-essential

amino acids (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). All cells were

cultured in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at

37°C.

Flow cytometry

Adhered cells were harvested using 1 mM EDTA (Wako

Pure Chemical Industries) in PBS at 37°C to maintain cell surface

protein integrity, as it was found that CSV is degraded by trypsin

treatment (20). Subsequently,

cells were blocked with Protein Block (Dako) for 15 min and then

sequentially incubated with primary antibodies, including an

anti-EpCAM antibody (clone: HEA125; cat. no. sc-59906; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), an anti-CSV antibody (clone: 84-1; cat. no.

H00007431-M08; Abnova), an anti-E-cadherin antibody (clone: 36;

cat. no. 610182; BD Biosciences), or an anti-Vimentin antibody

(clone: RV202; cat. no. 562337; BD Biosciences), each diluted to

1:100, for 60 min at room temperature. Following primary antibody

incubation, the cells were incubated with a goat anti-mouse IgG

antibody conjugated with FITC (cat. no. 349031; BD Biosciences),

diluted to 1:20, for 30 min at room temperature. Flow cytometry was

performed using an EC800 cell analyzer (Sony Biotechnology) and

FlowJo software version 10 (Becton-Dickinson and Co.) was used for

data analysis. The mean fluorescence intensity was determined by

comparison with the negative control.

Preparation of CTC-chip

The polymeric CTC-chip system was utilized following

a two-step coating process with antibodies to capture CTCs, as

previously described (11).

Initially, the chip (cat. no. G4B442; Cytona, Inc.) was incubated

overnight at 4°C with a goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (cat. no.

1031-01; SouthernBiotech) in PBS at a concentration of 200 µg/ml.

Subsequently, the chip was incubated for 60 min at room temperature

with either an anti-EpCAM antibody (20 µg/ml; clone HEA125) or an

anti-CSV antibody (10 and 100 µg/ml; clone 84-1) to capture the

tumor cells. The chip coated with the respective antibody was

denoted as the ‘EpCAM-chip’ and ‘CSV-chip’, respectively. After

incubation, the chip surface was washed with PBS and kept moist.

The chip is typically used following a 60-min antibody

reaction.

Sample preparation and evaluation of

cell-capture efficacy

Cells were labeled with the CellTrace™

carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) Cell Proliferation Kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and suspended in 1 ml PBS

containing 5% bovine serum albumin (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) or blood

sampled from a healthy volunteer (100 cells/ml). The cell

suspension sample (1 ml) was applied to the CTC-chip and sent to

the chip using a syringe pump at a constant flow rate of 1.0 ml/h.

Images and videos of the cells on the chip were captured using a

fluorescence microscope CKX41 (Olympus Corp.) and a digital video

camera (Sony Biotechnology, Inc.), respectively. The actual number

of cells (N-total) that were sent into the chip was determined by

counting the number of cells that passed through the chip inlet and

the number of captured cells (N-captured) was determined by

counting the CFSE-labelled cells remaining on the chip. Cell

capture efficiency was calculated as N-captured/N-total. The

healthy volunteer (author MK) donated blood and provided formal

written informed consent for its use in this study for experimental

purposes. Data collection from healthy subjects was included in the

Ethics Committee approval (approval no. H26-15).

Statistical analysis

The average and standard error of the capture

efficiency were calculated from 3 independent experimental repeats.

All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 27.0; IBM

Corp.).

Results

Classification of cell lines based on

E-cadherin and vimentin expression

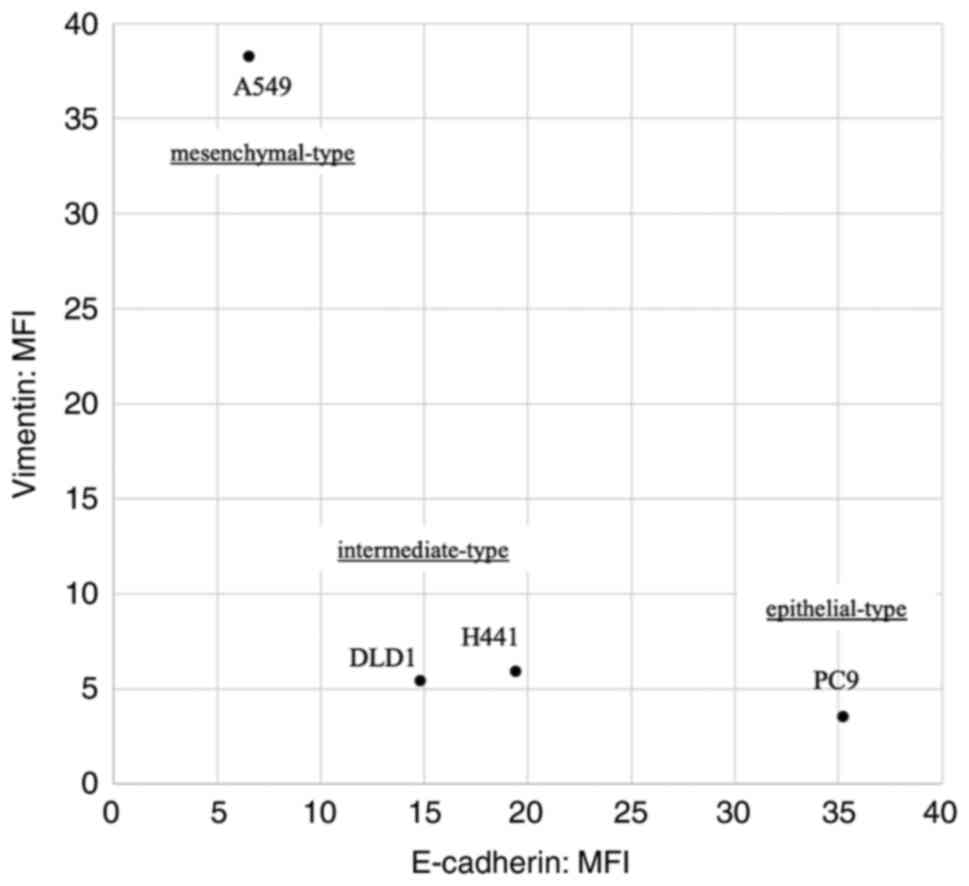

The classification of the cell lines based on flow

cytometric analysis of E-cadherin and vimentin expression is

summarized in Fig. 1. According to

these results, the cell lines were classified into three types:

Epithelial (PC9; high E-cadherin expression and low vimentin

expression), mesenchymal (A549; low E-cadherin expression and high

vimentin expression) and intermediate (H441 and DLD1).

EpCAM expression and capture

efficiency

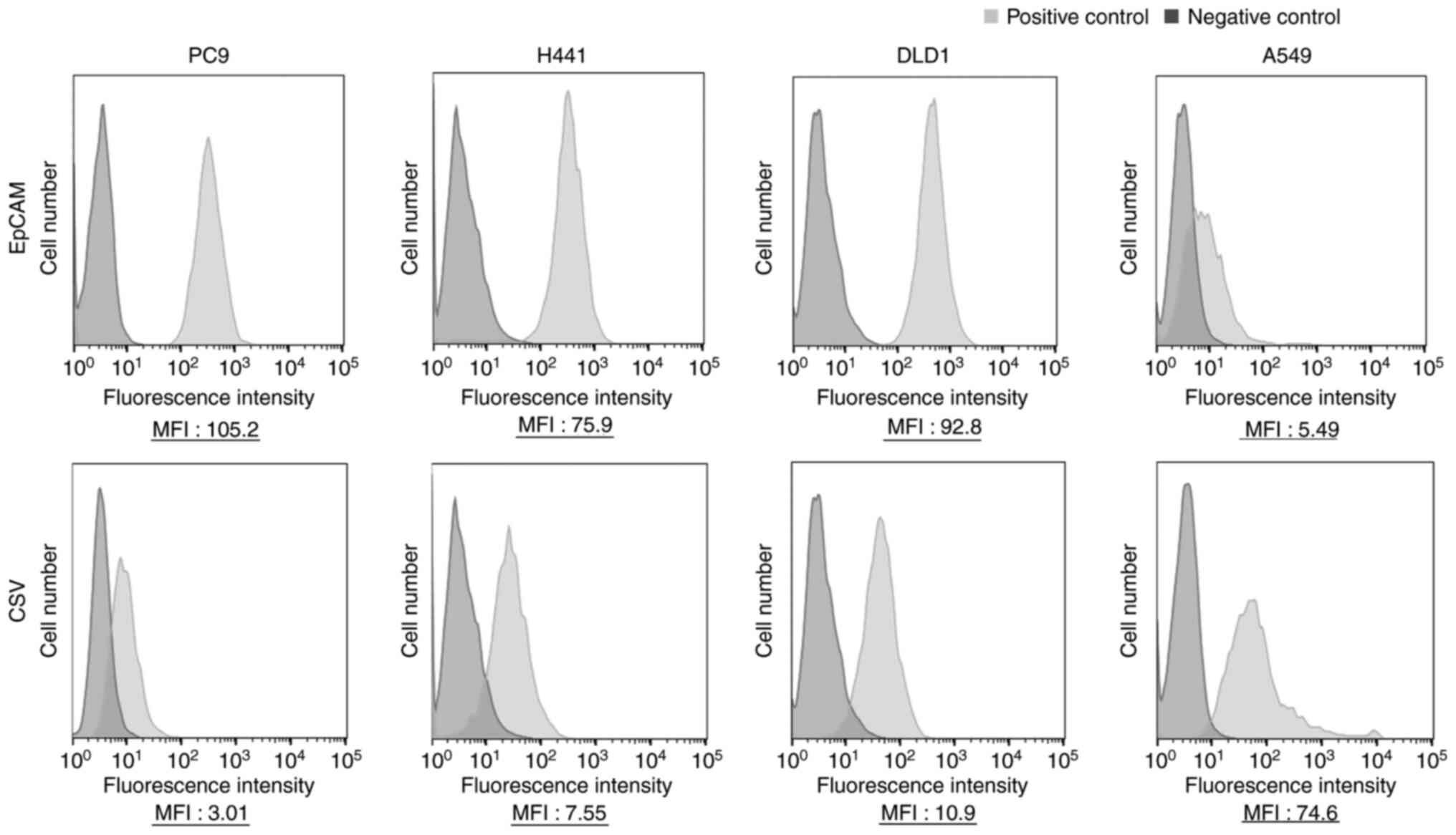

EpCAM was strongly expressed in the epithelial and

intermediate types but weakly expressed in the mesenchymal type

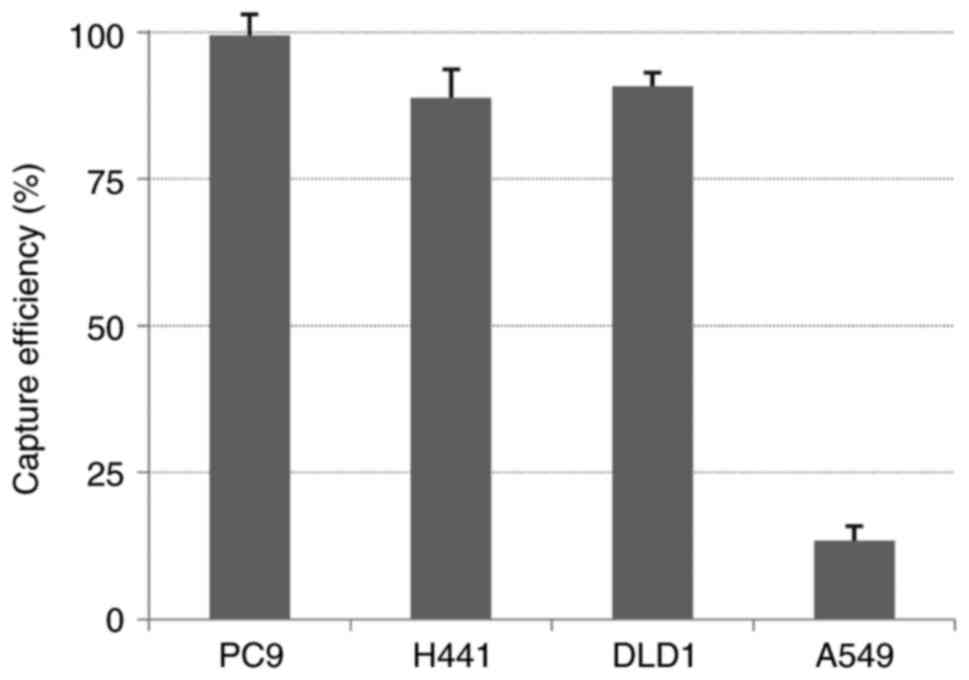

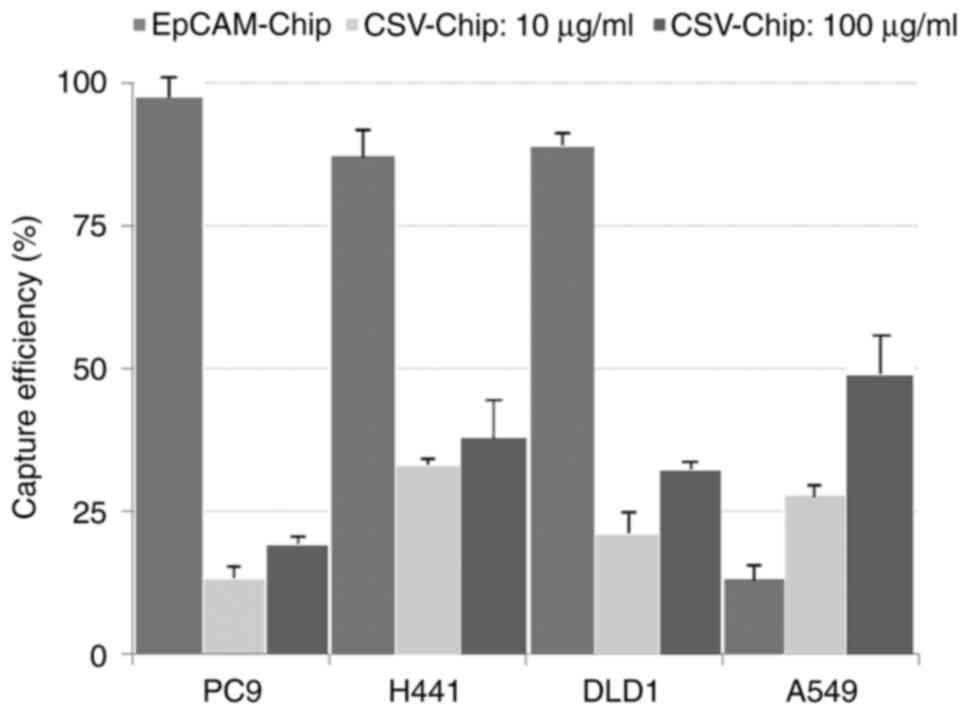

(Fig. 2). The capture efficiency of

the EpCAM-chip was in accordance with the expression intensity of

EpCAM. High capture rates were observed in the epithelial and

intermediate types (average capture efficiencies: PC9, 99.4%; H441,

88.8%; and DLD1, 90.8%), and a low capture rate was observed in the

mesenchymal type (average capture efficiency: A549, 13.4%)

(Fig. 3).

CSV expression and capture

efficiency

The expression of CSV was inversely in accordance

with that of EpCAM and increased in the following order:

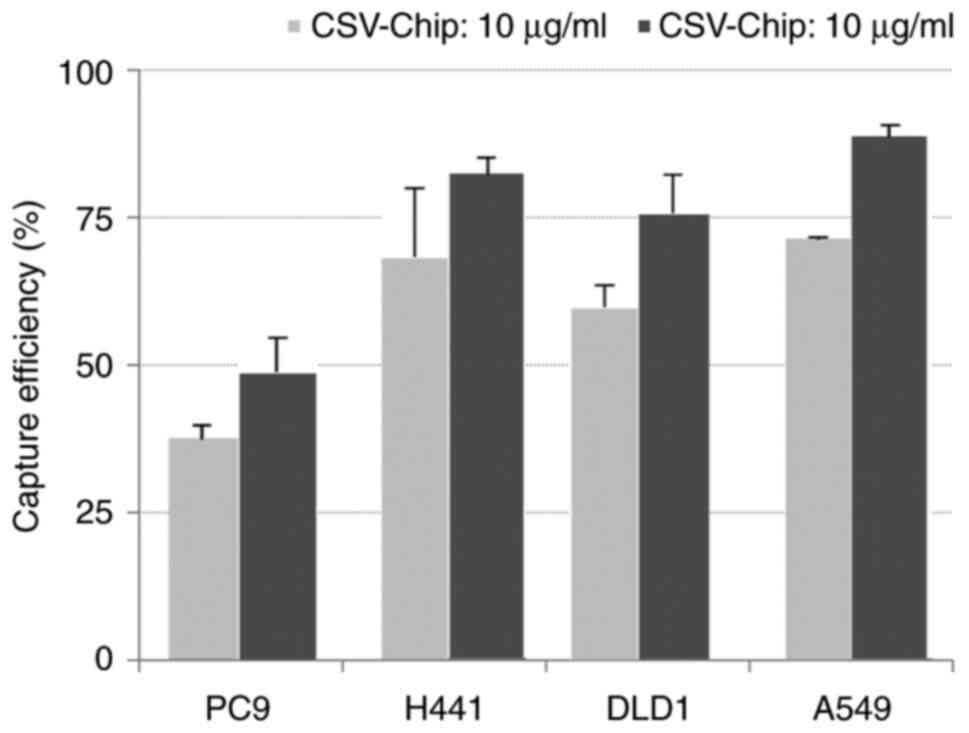

Mesenchymal, intermediate and epithelial (Fig. 3). The results obtained by examining

the capture efficiency of the CSV-chip when tumor cells were spiked

in PBS or blood at two concentrations (anti-CSV antibody: 10 and

100 µg/ml) are provided in Figs. 4

and 5. When spiked in PBS, the

average capture efficiencies of PC9, H441, DLD1 and A549 were 37.1,

68.2, 60.4 and 72.4%, at a concentration of 10 µg/ml, and 48.7,

82.1, 75.5 and 88.4%, at a concentration of 100 µg/ml, respectively

(Fig. 4). When spiked in blood, the

average capture efficiencies were 13.7, 33.0, 21.2 and 27.7% at a

concentration of 10 µg/ml, and 19.5, 38.2, 33.0 and 46.8% at a

concentration of 100 µg/ml (Fig.

5), respectively. The capture efficiency of the CSV-chip was

also in accordance with the expression intensity of CSV.

Discussion

The present study focused on CSV, a novel marker for

EMT-CTCs, as an alternative to traditional EpCAM-based capture

methods. The findings demonstrated that the CSV-chip effectively

captured mesenchymal-type cells, which are often overlooked by

EpCAM-dependent systems. This advancement represents a significant

improvement in cancer diagnostics and monitoring, offering a more

comprehensive tool for detecting metastatic cancer and studying

EMT-CTCs, which are pivotal subtypes involved in invasive growth

and metastatic spread.

Histological evaluation remains a cornerstone of

oncology diagnostics, providing essential insight into prognosis

and treatment planning for various cancer types. Traditionally,

this method relies on invasive tissue biopsies, which pose several

challenges, including patient discomfort, potential complications

and the risk of sampling errors due to tumor heterogeneity. By

contrast, liquid biopsies offer a less invasive alternative by

enabling real-time monitoring, comprehensive profiling and early

detection of relapse (21,22). Although CTCs are promising

biomarkers for liquid biopsies, their clinical utility has been

limited by low detection rates. The CellSearch system, which is the

only FDA-approved device for clinical CTC detection, relies on an

EpCAM-based capture method (3) that

can overlook tumor cells that have undergone EMT. This limitation

underscores the need for alternative detection methods and further

refinements (7,8).

EMT is a critical process in tumor invasion and

metastasis (6), which highlights

the necessity for EpCAM-independent capture systems. Vimentin, a

key marker of EMT, has been associated with tumor metastasis

(23–25). Traditionally, the expression of

vimentin in blood cells has previously restricted its use in CTC

capture (26). However, recent

research has identified a subset of aggressive CTCs that express

vimentin on their surface (CSV) and exhibit an EMT phenotype. This

finding suggests a higher likelihood of tumor recurrence and a

poorer prognosis for patients with CSV-positive CTCs (19). The development and validation of

monoclonal antibody clone 84-1, specific to CSV, represents a

significant advancement in targeting and capturing these cells

(17–19).

In the present study, by conjugating anti-CSV

antibodies to a universal CTC-chip designed to accommodate various

antibodies, a system for capturing EMT-CTCs was developed. This

system allowed for a more nuanced understanding of the role of

CSV-positive CTCs in cancer progression and metastasis. The

comprehensive classification of lung and colon cancer cell lines

based on EMT markers revealed that EpCAM was strongly expressed in

epithelial-type cells but was significantly reduced in

mesenchymal-type cells. Conversely, CSV expression was more

prevalent in cells with mesenchymal traits, highlighting its

potential as a specific marker for mesenchymal tumors.

Despite these encouraging results, the CSV-chip

demonstrated only moderate capture efficiency when cells were

spiked into blood samples, likely due to the inhibitory effects of

blood components on antigen-antibody interactions (12). This suggests that, while the

CSV-chip shows considerable promise, optimizing its conditions and

making additional refinements are essential for enhancing its

clinical performance. The present study identified a CSV

concentration of 100 µg/ml as optimal based on blood-based

concentration studies; however, further research is required to

validate this concentration for clinical applications. In addition,

pretreatment processes such as hemolysis, CD45 depletion or

peripheral blood mononuclear cell fractionation should be further

explored to enhance the capture efficiency and ensure more accurate

detection.

Recent studies have highlighted the increased counts

of CTCs and the higher proportions of CSV-positive CTCs in patients

with lymph nodes or distant metastases (27). Notably, patients with CSV-positive

CTCs experienced significantly shorter disease-free survival

compared to those with EpCAM-targeted CTCs, whose prognosis

remained unaffected (18,28,29).

These findings underscore the critical role of CSV-positive CTCs in

patient prognosis and support ongoing investigations into antibody

therapeutics targeting CSV to disrupt tumor-forming cells (30,31).

Our previous reports examining the prognostic significance of

EpCAM-CTCs have demonstrated the clinical impact of CTC counts

(15), and the study of CSV-CTCs

provides an opportunity to gain deeper insights into the

complexities of CTCs and their role in cancer progression.

Despite these promising results, one limitation of

the present study was the absence of clinical sample data. To

address this limitation, work is in progress to condition and

collect additional clinical samples for analysis to validate the

efficacy and clinical relevance of the CSV-chip in real-world

settings. This validation is essential for the broader application

and acceptance of the CSV-chip in clinical practice. The ongoing

investigation into CSV-CTCs is expected to refine our understanding

of CTCs in clinical contexts and potentially enhance the prognostic

and therapeutic strategies in cancer care.

In conclusion, the development of the CSV-chip

represents a significant advancement in CTC detection technology.

By enabling the capture of a broader range of CTCs, including those

undergoing EMT, the CSV-chip enhances our ability to monitor and

understand metastasis more effectively. Future research should

focus on validating these findings in patient samples and

integrating this technology with downstream molecular analyses.

This approach will provide deeper insights into the biology of

metastasis and guide personalized cancer treatment strategies,

ultimately contributing to more effective management of metastatic

cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MK, KY and FT conceived and designed the study. TK,

TM, RO, HM, MT and KK assisted with the study setup and provided

critical insights. MK, TK and MM performed cell experiments. TO

provided the CTC-chip and technical support. MK drafted the

manuscript. FT was involved in the project management and

supervised the study. MK and FT confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the

Institutional Review Board of the University of Occupational and

Environmental Health, Japan (Approval No: 10-127). The healthy

volunteer (author MK) donated blood and provided formal written

informed consent for its use in this study for experimental

purposes. Data collection from healthy subjects was included in the

Ethics Committee approval (approval no. H26-15).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

EpCAM

|

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

|

|

CTCs

|

circulating tumor cells

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

|

CSV

|

cell surface vimentin

|

References

|

1

|

Lozar T, Gersak K, Cemazar M, Kuhar CG and

Jesenko T: The biology and clinical potential of circulating tumor

cells. Radiol Oncol. 53:131–147. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Deng Z, Wu S, Wang Y and Shi D:

Circulating tumor cell isolation for cancer diagnosis and

prognosis. EBioMedicine. 83:1042372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet

M, Connelly MC, Rao C, Tibbe AG, Uhr JW and Terstappen LW: Tumor

cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but

not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases.

Clin Cancer Res. 10:6897–6904. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cohen SJ, Punt CJ, Iannotti N, Saidman BH,

Sabbath KD, Gabrail NY, Picus J, Morse M, Mitchell E, Miller MC, et

al: Relationship of circulating tumor cells to tumor response,

progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with

metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 26:3213–3221. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tanaka F, Yoneda K, Kondo N, Hashimoto M,

Takuwa T, Matsumoto S, Okumura Y, Rahman S, Tsubota N, Tsujimura T,

et al: Circulating tumor cell as a diagnostic marker in primary

lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 15:6980–6986. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Brabletz S, Schuhwerk H, Brabletz T and

Stemmler MP: Dynamic EMT: A multi-tool for tumor progression. EMBO

J. 40:e1086472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lu G, Lu Z, Li C, Huang X and Luo Q:

Prognostic and therapeutic significance of circulating tumor cell

phenotype detection based on epithelial-mesenchymal transition

markers in early and midstage colorectal cancer first-line

chemotherapy. Comput Math Methods Med. 2021:22945622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gao Y, Fan WH, Song Z, Lou H and Kang X:

Comparison of circulating tumor cell (CTC) detection rates with

epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and cell surface vimentin

(CSV) antibodies in different solid tumors: A retrospective study.

PeerJ. 9:e107772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ohnaga T, Shimada Y, Moriyama M, Kishi H,

Obata T, Takata K, Okumura T, Nagata T, Muraguchi A and Tsukada K:

Polymeric microfluidic devices exhibiting sufficient capture of

cancer cell line for isolation of circulating tumor cells. Biomed

Microdevices. 15:611–616. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell

DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky

A, et al: Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer

patients by microchip technology. Nature. 450:1235–1239. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chikaishi Y, Yoneda K, Ohnaga T and Tanaka

F: EpCAM-independent capture of circulating tumor cells with a

‘universal CTC-chip’. Oncol Rep. 37:77–82. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kuwata T, Yoneda K, Mori M, Kanayama M,

Kuroda K, Kaneko MK, Kato Y and Tanaka F: Detection of circulating

tumor cells (CTCs) in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) with the

‘universal’ CTC-chip and an anti-podoplanin antibody NZ-1.2. Cells.

9:8882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kanayama M, Oyama R, Mori M, Taira A,

Shinohara S, Kuwata T, Takenaka M, Yoneda K, Kuroda K, Ohnaga T, et

al: Novel circulating tumor cell-detection chip combining

conventional podoplanin and EGFR antibodies for all histological

malignant pleural mesothelioma. Oncol Lett. 22:5222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yoneda K, Kuwata T, Chikaishi Y, Mori M,

Kanayama M, Takenaka M, Oka S, Hirai A, Imanishi N, Kuroda K, et

al: Detection of circulating tumor cells with a novel microfluidic

system in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Sci. 110:726–733.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kanayama M, Kuwata T, Mori M, Nemoto Y,

Nishizawa N, Oyama R, Matsumiya H, Taira A, Shinohara S, Takenaka

M, et al: Prognostic impact of circulating tumor cells detected

with the microfluidic ‘universal CTC-chip’ for primary lung cancer.

Cancer Sci. 113:1028–1037. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Satelli A, Mitra A, Brownlee Z, Xia X,

Bellister S, Overman MJ, Kopetz S, Ellis LM, Meng QH and Li S:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transitioned circulating tumor cells capture

for detecting tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 21:899–906. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Satelli A, Batth I, Brownlee Z, Mitra A,

Zhou S, Noh H, Rojas CR, Li H, Meng QH and Li S: EMT circulating

tumor cells detected by cell-surface vimentin are associated with

prostate cancer progression. Oncotarget. 8:49329–49337. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wei T, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Yang J, Chen Q,

Wang J, Li X, Chen J, Ma T, Li G, et al: Vimentin-positive

circulating tumor cells as a biomarker for diagnosis and treatment

monitoring in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett.

452:237–243. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li H, Zhu YZ, Xu L, Han T, Luan J, Li X,

Liu Y, Wang Z, Liu Q, Kong X, et al: Exploring new frontiers: Cell

surface vimentin as an emerging marker for circulating tumor cells

and a promising therapeutic target in advanced gastric cancer. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:1292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Riegger J and Brenner RE: Increase of cell

surface vimentin is associated with vimentin network disruption and

subsequent stress-induced premature senescence in human

chondrocytes. Elife. 12:e914532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Markou A, Tzanikou E and Lianidou E: The

potential of liquid biopsy in the management of cancer patients.

Semin Cancer Biol. 84:69–79. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Alix-Panabières C, Marchetti D and Lang

JE: Liquid biopsy: From concept to clinical application. Sci Rep.

13:216852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Strouhalova K, Přechová M, Gandalovičová

A, Brábek J, Gregor M and Rosel D: Vimentin intermediate filaments

as potential target for cancer treatment. Cancers (Basel).

12:1842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Usman S, Waseem NH, Nguyen TKN, Mohsin S,

Jamal A, Teh MT and Waseem A: Vimentin is at the heart of

epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) mediated metastasis.

Cancers (Basel). 13:49852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Paulin D, Lilienbaum A, Kardjian S,

Agbulut O and Li Z: Vimentin: Regulation and pathogenesis.

Biochimie. 197:96–112. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ramos I, Stamatakis K, Oeste CL and

Pérez-Sala D: Vimentin as a multifaceted player and potential

therapeutic target in viral infections. Int J Mol Sci. 21:46752020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Xie X, Wang L, Wang X, Fan WH, Qin Y, Lin

X, Xie Z, Liu M, Ouyang M, Li S and Zhou C: Evaluation of cell

surface vimentin positive circulating tumor cells as a diagnostic

biomarker for lung cancer. Front Oncol. 11:6726872021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yu J, Yang M, Peng T, Liu Y and Cao Y:

Evaluation of cell surface vimentin positive circulating tumor

cells as a prognostic biomarker for stage III/IV colorectal cancer.

Sci Rep. 13:187912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Batth IS, Dao L, Satelli A, Mitra A, Yi S,

Noh H, Li H, Brownlee Z, Zhou S, Bond J, et al: Cell surface

vimentin-positive circulating tumor cell-based relapse prediction

in a long-term longitudinal study of postremission neuroblastoma

patients. Int J Cancer. 147:3550–3559. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Noh H, Zhao Q, Yan J, Kong LY,

Gabrusiewicz K, Hong S, Xia X, Heimberger AB and Li S: Cell surface

vimentin-targeted monoclonal antibody 86C increases sensitivity to

temozolomide in glioma stem cells. Cancer Lett. 433:176–185. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Batth IS and Li S: Discovery of

cell-surface vimentin (CSV) as a sarcoma target and development of

CSV-targeted IL12 immune therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1257:169–178.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|