Introduction

Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), responsible

for >80% of all lung cancer cases, is the deadliest form of

malignancy worldwide (1). Despite

advancements in therapeutic strategies such as surgical resection,

chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and combination

therapies, each focusing primarily on symptom alleviation, the

5-year overall survival rate of NSCLC remains <20% (2). This is further complicated by the

widespread occurrence of chemoresistance and the increased

metastatic potential of the disease, which undermine the efficacy

of conventional treatments (3).

This challenge is, at least in part, attributable to the

self-renewal properties of cancer stem cells (4), which are resistant to chemotherapy,

rendering traditional treatments less effective. As such, there is

an urgent need for innovative therapeutic approaches targeting

NSCLC cancer stem cells. Research has intensified efforts to

understand self-renewal and tumor growth mechanisms, aiming to

identify novel therapeutic targets or develop innovative curative

interventions for various cancer types, including NSCLC (4–6).

Studies have identified a small subset of tumor cells that, derived

from bulk tumors, possess self-renewal and tumor-initiating

abilities (7–9). These cells are typically enriched

using cell surface markers (CD133, CD44, Sox2 and Oct4) or sphere

formation assays in suspension culture (4,5,8,10,11).

Notably, the sphere culture assay has proven effective in enriching

sphere-forming cells (SFCs) from NSCLC cell lines, and SFCs exhibit

stronger self-renewal potential (12,13).

There is a critical need to develop effective therapeutic

strategies, particularly novel targeted drugs aimed at directly

addressing cancer cell self-renewal and tumor growth in NSCLC.

Genistein, an isoflavone found abundantly in

soybeans and related products, has exhibited anticancer properties

across various malignancies such as retinoblastoma, laryngeal

cancer and colorectal cancer (14–16).

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octylgenistein (DFOG), a new genistein

analog synthesized independently by the Department of Pharmacy,

Hunan Normal University (Changsha, China), has been shown to induce

apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells, and to inhibit their

self-renewal and carcinogenesis (17,18).

Despite these promising findings, the exact mechanism through which

DFOG suppresses self-renewal and tumor growth in NSCLC cells

remains to be fully elucidated.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are evolutionarily

conserved, endogenous small noncoding RNAs, typically 19–23

nucleotides in length (19).

Despite lacking protein-coding potential, they regulate a wide

array of genes post-transcriptionally through complementary binding

to mRNAs (20). These molecules are

critical in processes such as apoptosis, differentiation,

proliferation and metabolism, making them central to cancer

development and stemness in cancer cells (21). One such miRNA, miR-152, has been

identified as a tumor suppressor and is linked to malignant

phenotypes of various types of cancer such as colon cancer, breast

cancer, prostate cancer and ovarian cancer (22–25). A

recent study has demonstrated that miR-152-3p is involved in the

self-renewal and tumor growth of non-small cell lung cancer

(26). Additionally, miR-152-3p is

associated with tumor invasion, metastasis, drug resistance and

proliferation (27,28). However, whether DFOG can inhibit the

self-renewal and tumor growth of NSCLC by regulating miR-152-3p

remains to be determined.

Persistent activation of STAT3 impacts gene

regulation, thereby influencing self-renewal, migration and

invasion in cancer cells (29,30).

The miR-152/STAT3 axis is associated with poor prognosis in

epithelial ovarian cancer (31). A

previous study using JSI-124, a specific STAT3 inhibitor, suggested

that suppressing STAT3 activation can diminish stem cell-like

properties in hepatocellular carcinoma cells (32). However, it remains unclear whether

miR-152-3p-mediated STAT3 inactivation can effectively reduce the

self-renewal and tumor growth of SFCs derived from NSCLC.

Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the hypothesis that

reinstating miR-152-3p expression to suppress STAT3 can

synergistically enhance the inhibitory effects of DFOG on

self-renewal and tumor growth in SFCs derived from NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Cells and sphere cultures

The NCI-H460 and NCI-A549 human NSCLC cell lines

were obtained from Shanghai Zhong Qiao Xin Zhou Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd., and Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.,

respectively, while the BEP2D human bronchial epithelial cell line

was sourced from Otwo Biotech. All cell lines were authenticated

through short tandem repeat profiling and mycoplasma testing. The

cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml). All cells were

maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The STAT3

inhibitor S3I 201 (97%; cat. no. ab146606; Abcam) was stored at

room temperature, and the cells were treated with S3I 201 (10 µM)

at 37°C for 24 h before subsequent experiments.

To study sphere formation, H460 and A549 cells were

cultured in stem-cell culture medium at a density of 5,000 cells

per well in ultra-low attachment 6-well plates until spheres

containing >20 cells formed (12,13).

Stem-cell culture medium (DMEM/F12; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), supplemented with 2% B27, 1%

penicillin/streptomycin, basic fibroblast growth factor (20 ng/ml),

epidermal growth factor (20 ng/ml) and insulin (4 µg/ml), was used.

The inhibitory effects of DFOG on sphere formation were assessed by

incubating SFCs derived from H460 and A549 cells with varying

concentrations of DFOG (1, 5 and 10 µM) at 37°C for 72 h.

Subsequently, the cells were reseeded at a density of 1,000 cells

per well in ultra-low attachment 24-well plates and cultured until

spheres reformed in the absence of DFOG. Subsequently, the number

and status of spheres were evaluated manually under a light

microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). The sphere formation rate was

calculated using the following formula: Number of spheres/number of

cells seeded ×100%. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cell viability assessment

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.). Single-cell

suspensions were seeded at 1,000 cells per well in 96-well plates

for 24 h and treated with varying concentrations of DFOG (1, 5 and

10 µM) at 37°C. After 72 h, the cells were incubated with 10 µl

CCK-8 solution per well for 2 h, and the optical density

(OD450) was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

The Superscript IV RT kit and SYBR Green fluorophore

were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. The RT reaction

conditions were incubation at 37°C for 5 min, 50°C for 15 min and

75°C for 5 min. Total RNA was extracted from H460 cells, A549 cells

or SFCs (1×105 cells) using TRIzol® reagent

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. For RNA extraction from tissue samples, grinding using a

tissue homogenizer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was first

performed. cDNA synthesis was conducted according to the supplier's

instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

2−ΔΔCq method (33) was

used for qPCR, with U6 as the internal control for miR-152 and

GAPDH as the internal control for STAT3. To identify candidate

miRNAs affected by DFOG treatment, H460 cells, A549 cells or SFCs

were treated with DFOG (5 µM) at 37°C for 24 h, followed by total

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis. PCR amplification was performed

using specific primers (Table I),

with the following thermocycling conditions: 95°C for 10 min,

followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 70°C

for 30 sec. For miRNA quantification, 2 µg total miRNA was

transcribed and amplified using the All-in-One™ miRNA qRT-PCR

Detection Kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and the TaqMan MicroRNA Assay (GeneCopoeia, Inc.), with U6 (Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd.) as the reference gene. Data analysis was

conducted using the 2−ΔΔCq method. All experiments were

conducted in triplicate independently.

| Table I.Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene name | Primer sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| U6 | F:

CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

|

| R:

AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

| STAT3 | F:

GGGAGAGAGTTACAGGTTGGACAT |

|

| R:

AGACGCCATTACAAGTGCCA |

| GAPDH | F:

CGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTAT |

|

| R:

ATCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGAC |

| miR-671-5p | F:

AGGAAGCCCTGGAGGGGC |

|

| R:

CAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTAT |

| miR-148a-3p | F:

TCAGTGCACTACAGAACTTTGT |

|

| R:

AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTAT |

| miR-340-5p | F:

TTATAAAGCAATGAGACTGATT |

|

| R:

AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT |

| miR-342-3p | F:

TCTCACACAGAAATCGCACCC |

|

| R:

AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTAT |

| miR-34a-5p | F:

TGGCAGTGTCTTAGCTGGTTGT |

|

| R:

AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT |

| miR-152-3p | F:

TCAGTGCATGACAGAACTTGG |

|

| R:

TGCAGGGTCCGAGGTAT |

Clonogenic assay

For the colony formation assay, a bottom agar layer

was prepared by mixing 1.2% agarose (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) with DMEM in equal proportions, and 500 µl of

this mixture was added to each well of a 24-well plate. The top

agar layer was prepared by mixing H460 cells, A549 cells or SFCs

(1,000 cells) with 0.7% agarose and 500 µl of 20% FBS-supplemented

DMEM. After 12 h of cell seeding, different concentrations of DFOG

(1, 5 and 10 µM) were added according to the needs of each group.

The drug was continuously administered at 37°C until the end of the

experiment. Images of colony formation were captured under a light

microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH) and colonies were counted

manually. More than 20 cells were defined as a colony. The cells

were incubated for 14 days at 37°C, and colonies were counted to

calculate the colony formation rate per 1,000 cells based on

triplicate experiments.

Immunoblot assay

The RIPA protein extraction kit was purchased from

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. BCA was used to quantitatively

determine the protein concentration. Each lane was loaded with 20

µg of protein. The gel concentration used was 10%. After

electrophoresis, protein was transferred to a PVDF membrane.

Blocking was performed using 5% skimmed milk at 37°C for 1 h.

Membranes were incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C for 6 h,

and membranes were incubated with the horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated IgG secondary antibody (1:1,000 dilution;

cat. no. RGAR011; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at room temperature for

1 h. Antibodies against α-tubulin (1:1,000 dilution; cat. no. 2125;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), STAT3 (1:1,000 dilution; cat. no.

12640; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), phosphorylated-STAT3

(p-STAT3; 1:2,000 dilution; cat. no. 9145; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), CD133 (1:1,000 dilution; cat. no. 64326; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), CD44 (1:1,000 dilution; cat. no.

37259; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), Oct4 (1:1,000 dilution;

cat. no. 2890; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and Sox2 (1:1,000

dilution; cat. no. 3579; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) were used

as previously described (12).

Finally, the chemiluminescent substrate (ECL) was purchased from

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, and ImageJ 1.37 (National

Institutes of Health) was used for gray-scale analysis.

miRNA transfection

MicrON™ miR-152-3p mimic

(5′-UCAGUGCAUGACAGAACUUGG-3′) and micrOFF™ miR-152-3p inhibitor

(5′-CCAAGUUCUGUCAUGCACUGA-3′), miR-152-3p mimic negative control

(5′-UUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3′) and miR-152-3p inhibitor negative

control (5′-GGAACUUAGCCACUGUGAAUU-3′), were purchased from

Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd., and transfected into SFCs using

transfection reagent iboFECT™ CP (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) at a

concentration of 50 nM, according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The small RNA complexes were incubated with cells for

2 h before the medium was replaced, then the culture was continued

at 37°C for 48 h, and cells were used for subsequent

experiments.

Luciferase reporter assay

The binding sites of miR-152-3p and STAT3 were

predicted using RNAhybrid (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid).

For the luciferase reporter assays, SFCs were co-transfected with

miR-152-3p or miR-control and the pGL3 luciferase vector (Guangzhou

RiboBio Co., Ltd.) containing the firefly luciferase reporter,

along with the wild-type (WT) or mutant (MUT) 3′-untranslated

region (UTR) sequence of STAT3. After 48 h, luciferase activity was

measured using a luciferase assay kit (Promega Corporation), and

normalized to Renilla luciferase activity in triplicate

experiments.

Plasmid transfection

Transfection was performed using 10 µg nucleic acid

with a concentration of 1 µg/µl at 37°C for 48 h, and subsequent

experiments were performed 48 h after transfection. For STAT3

overexpression, cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-Control or

pcDNA3.1-STAT3 plasmids obtained from Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in Opti-MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

In vivo therapeutic effects in nude

mice

A total of 18 female pathogen-free nude BALB/c mice

(aged 4–5 weeks; weight, 18–22 g) were sourced from GemPharmatech

Co., Ltd., and housed in a specific pathogen-free facility [SYXK

(Xiang) 2020-0012] under a standard 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, at

20–26°C, with an atmospheric pressure of 20–50 Pa and a relative

humidity of 40–70%, and ad libitum access to regular mouse

chow and water. The site of cell injection was the armpit of the

upper limb. When the tumor grew to ~100 cm3, the mouse

was treated with drug treatment for 21 days. The time interval

between the injection of cells and the end of the experiment was 6

weeks, and tumor volume was detected every 2 days until the end of

the experiment. The ethical approval (approval no. D2023045) was

granted by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University

(Changsha, China).

To evaluate the effects of DFOG in the xenograft

mouse model, 1×106 SFCs were suspended in PBS and mixed

with 100% Matrigel at a 1:1 ratio (BD Biosciences). A 100 µl

mixture was subcutaneously injected into each mouse. When the

xenograft volume reached ~100 mm3, mice in the control

group received 200 µl of 2% DMSO every 2 days, while those in the

experimental groups were orally administered DFOG (10 and 50 mg/kg)

for 3 weeks every 2 days. Each group consisted of 6 mice. Tumor

volume was calculated using the following formula: V

(mm3)=(L × W2)/2, where L is the longest

diameter and W is the shortest diameter of the xenograft, measured

using a Vernier caliper. At the end of the experiment,

xenograft-bearing mice were euthanized using CO2

asphyxiation (CO2 replacement rate of 30%), and the

xenografts were collected, weighed, and snap-frozen in liquid

nitrogen, and tumor tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for

subsequent H&E staining and immunohistochemistry. Tumor tissues

for qPCR analysis were preserved in RNAlater.

For H&E staining, tumor tissues were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h, and the slice thickness was 4 µm.

Hematoxylin staining was performed for 5 min, followed by eosin

staining for 1 min, and these were performed at 25°C. Staining was

observed under a light microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Immunohistochemical staining

Tumor tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at

4°C for 24 h. Tissue sections (thickness, 4 µm) from

paraffin-embedded and fixed samples were subjected to

deparaffinization in citrate buffer. Sections were heated in an

oven at 90°C for 20 min, followed by a series of ethanol washes

(anhydrous ethanol, 95, 85 and 75% ethanol). Subsequently, the

slices underwent three consecutive washes with PBS. After blocking

endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H2O2

and nonspecific binding with 5% goat serum (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 15 min at 25°C, the sections were incubated

overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody against p-STAT3 (1:200

dilution; cat. no. 9145; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). As a

negative control, PBS was used in place of the primary antibody.

The sections were then incubated with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (1:500 dilution;

cat. no. RGAR011; Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 20 min at 25°C.

Staining was developed using the 3,3′diaminobenzidine substrate

(Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.). The results

were observed and images were captured under a light microscope

(Leica Microsystems GmbH). The signal intensity was evaluated as

previously described (34), and

semi-quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ 1.37.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using

GraphPad Prism Software 9 (Dotmatics). Data are presented as the

mean ± SD. Comparisons between groups were performed using one-way

analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test or an unpaired

Student's t-test. For in vitro analyses, experiments were

performed in triplicate. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

DFOG small-scale miRNAs efficacy

screen, and analysis of self-renewal-related stemness of

H460-derived SFCs

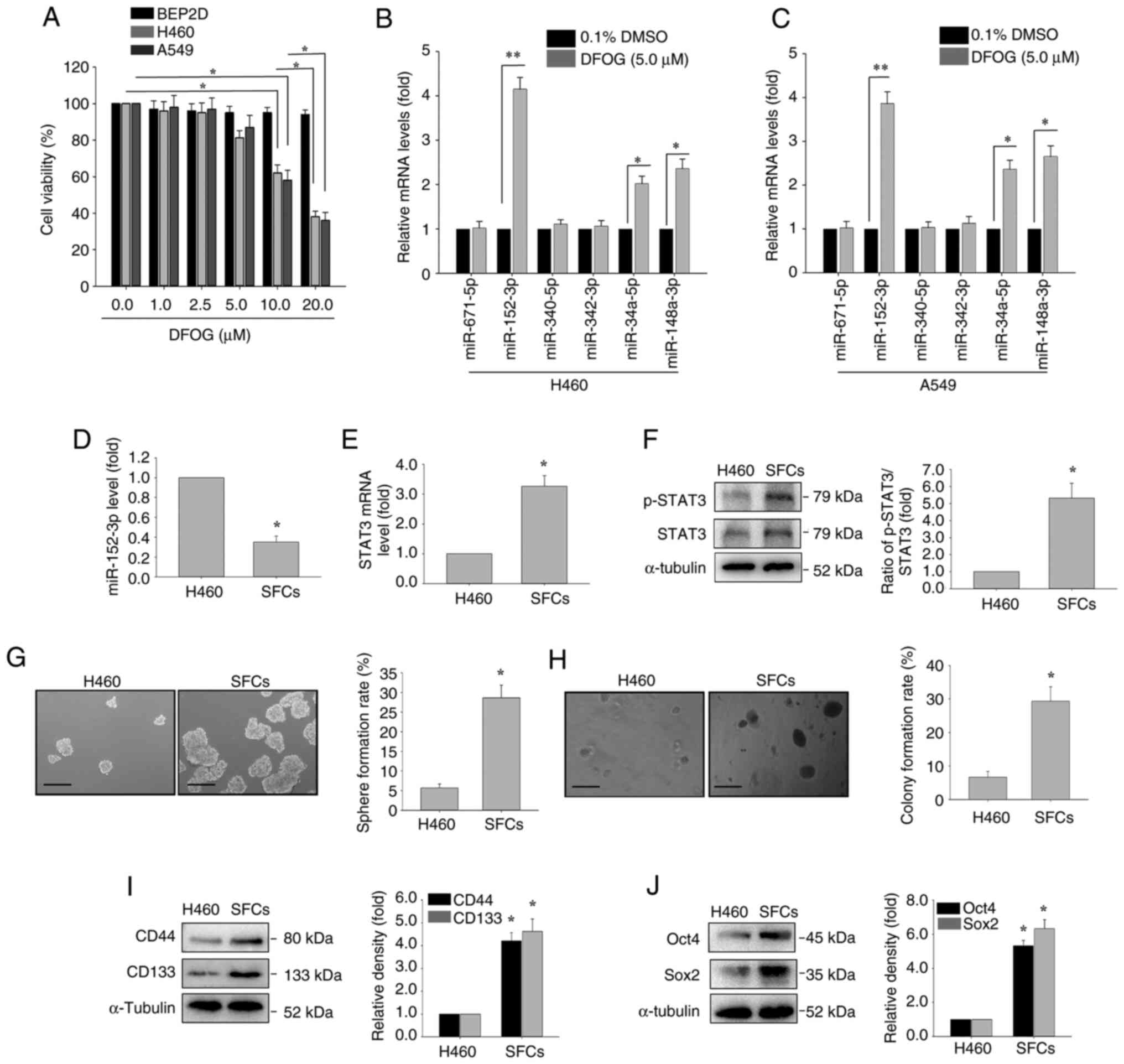

The effect of DFOG on cell viability was assessed in

BEP2D, H460 and A549 cell lines using the CCK-8 assay, following

treatment at various concentrations. A reduction in cell viability

was observed in H460 and A549 cells compared with the control group

(0 µM), yielding an IC50 of ~10 µM (Fig. 1A). Noncytotoxic concentrations of

DFOG (1, 5 and 10 µM) were selected for subsequent experiments.

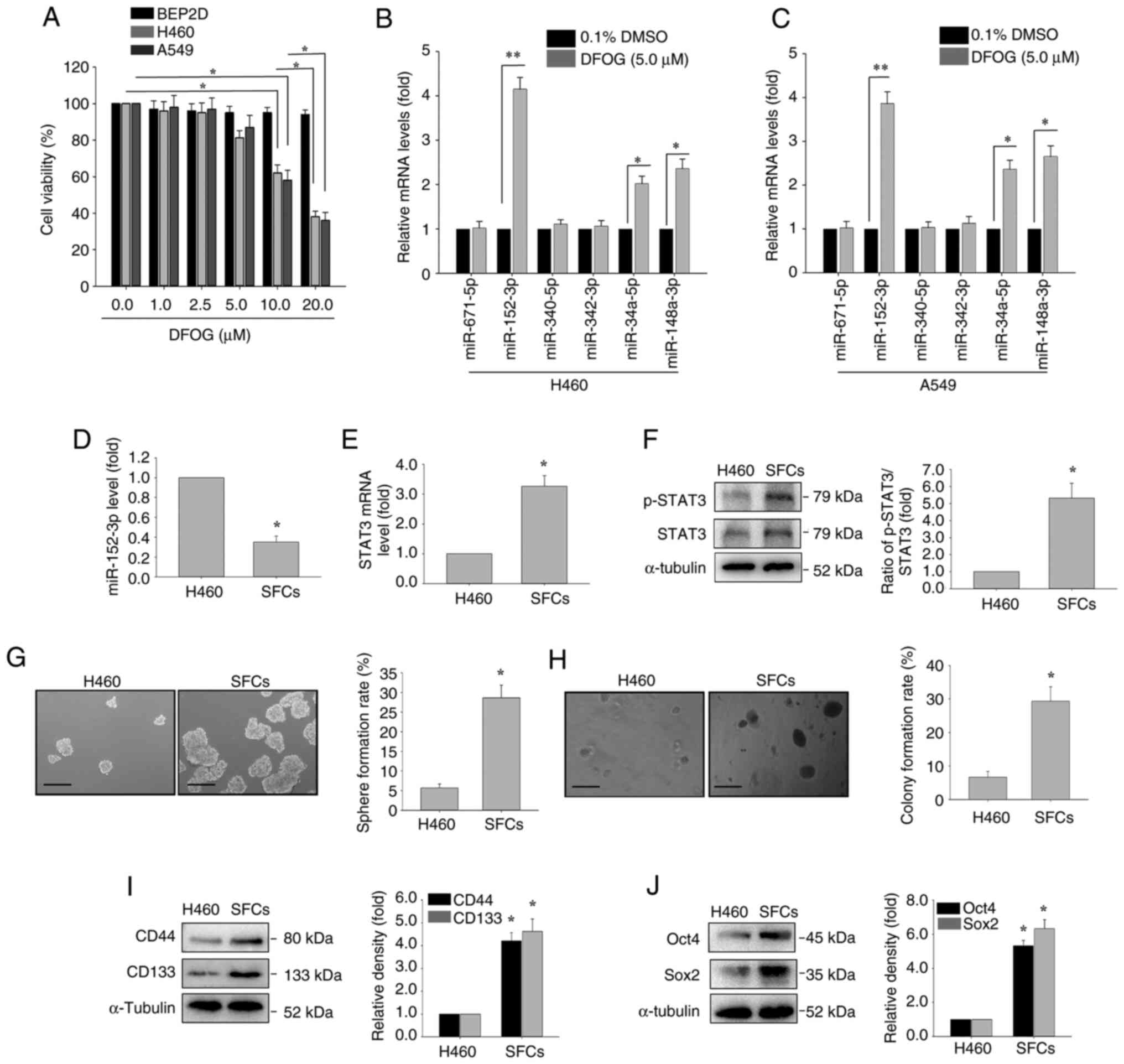

| Figure 1.mRNA expression analysis by RT-qPCR,

and assessment of self-renewal and tumor growth in H460-derived

SFCs. (A) BEP2D, H460 and A549 cells were treated with DFOG (0–20

µM) for 48 h, and cell viability was assessed using a Cell Counting

Kit-8 assay. H460 and A549 cells were treated with DFOG (5 µM) for

24 h. RT-qPCR was used to evaluate the effects of DFOG (5 µM) on

tumor-suppressive miRNAs, including miR-671-5p, miR-148a-3p,

miR-340-5p, miR-342-3p, miR-34a-5p and miR-152-3p in (B) H460 and

(C) A549 cells. (D) Comparison of miR-152-3p expression between

H460 cells and H460-derived SFCs. (E) STAT3 mRNA levels and (F)

p-STAT3 protein levels. Rates of (G) sphere formation and (H)

colony formation (scale bar, 100 µm). Western blot analysis of (I)

CD44 and CD133 expression, as well as (J) Oct4 and Sox2 expression.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 (n=3). DFOG,

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octylygenistein; miR/miRNA, microRNA;

p-, phosphorylated; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR; SFC, sphere-forming cell. |

Natural phytochemicals have been reported to

modulate miRNA-mediated suppression of stemness characteristics in

hepatocellular carcinoma cells (34). Therefore, it was detected whether

tumor suppressor miRNAs in NSCLC cells, including miR-671-5p

(31), miR-148a-3p (35), miR-340-5p (36), miR-342-3p (37), miR-34a-5p (38) and miR-152-3p (39), are regulated by DFOG (5 µM). DFOG

treatment (5 µM) led to significant upregulation of miR-152-3p in

both H460 and A549 cell lines, with the most notable increase among

the tested miRNAs (Fig. 1B and

C).

To examine the role of miR-152-3p and STAT3

expression in self-renewal and tumor growth in NSCLC, miR-152-3p

expression was compared between H460 cells and H460-derived SFCs.

The results revealed lower miR-152-3p levels in SFCs compared with

H460 cells (Fig. 1D). Additionally,

SFCs exhibited elevated STAT3 mRNA expression and p-STAT3 levels

(Fig. 1E and F).

The sphere formation and colony formation were

significantly increased in H460-derived SFCs compared with H460

cells (Fig. 1G and H). Furthermore,

the expression levels of stem cell-associated markers, including

CD133, CD44, Oct4 and Sox2, were elevated in H460-derived SFCs

compared with H460 cells (Fig. 1I and

J).

DFOG inhibits self-renewal-related

stemness possibly by upregulating miR-152-3p and inhibiting p-STAT3

in H460-derived SFCs

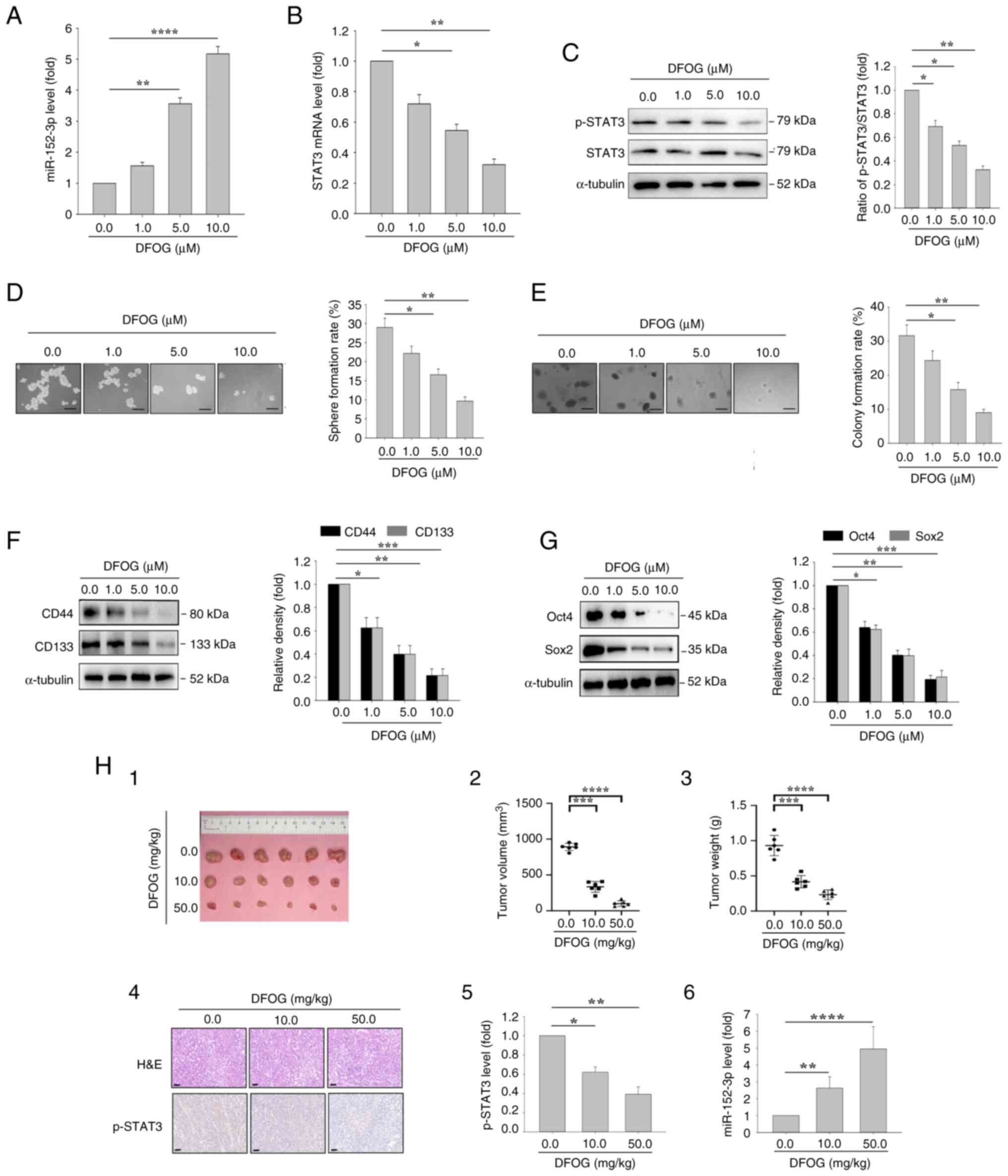

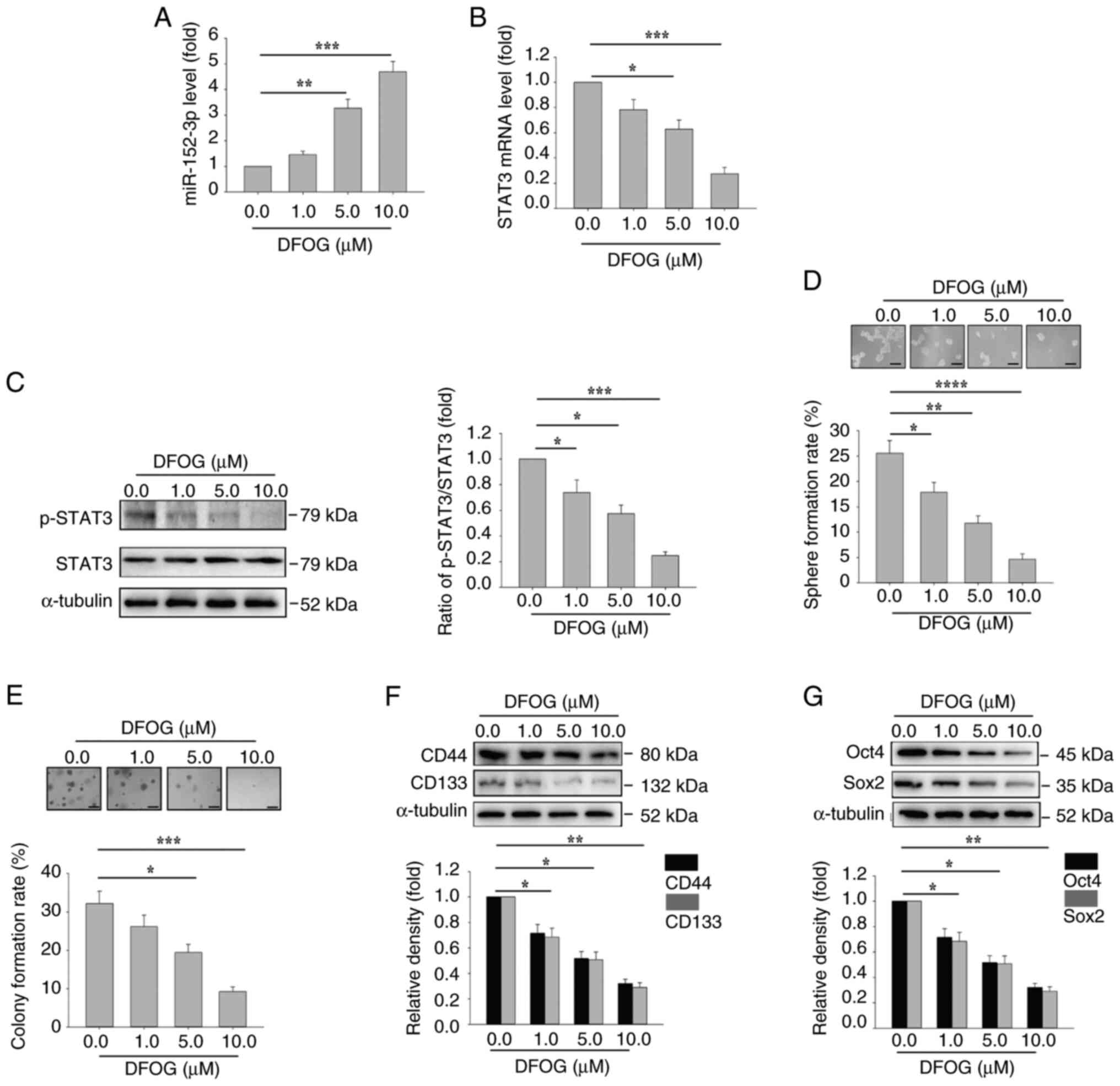

DFOG treatment at noncytotoxic concentrations (1, 5

and 10 µM) induced a dose-dependent increase in miR-152-3p

expression in H460-derived SFCs (Fig.

2A). miR-152-3p has been recognized for its role in suppressing

carcinogenesis by inhibiting carcinogenic transcription factors and

signaling pathways in colon cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer

and ovarian cancer (22–25). Subsequently, the effects of DFOG on

STAT3 mRNA expression and p-STAT3 protein levels were assessed

using RT-qPCR and western blotting. DFOG treatment resulted in a

decrease in STAT3 mRNA expression (Fig.

2B) and a significant reduction in p-STAT3 protein levels

(Fig. 2C).

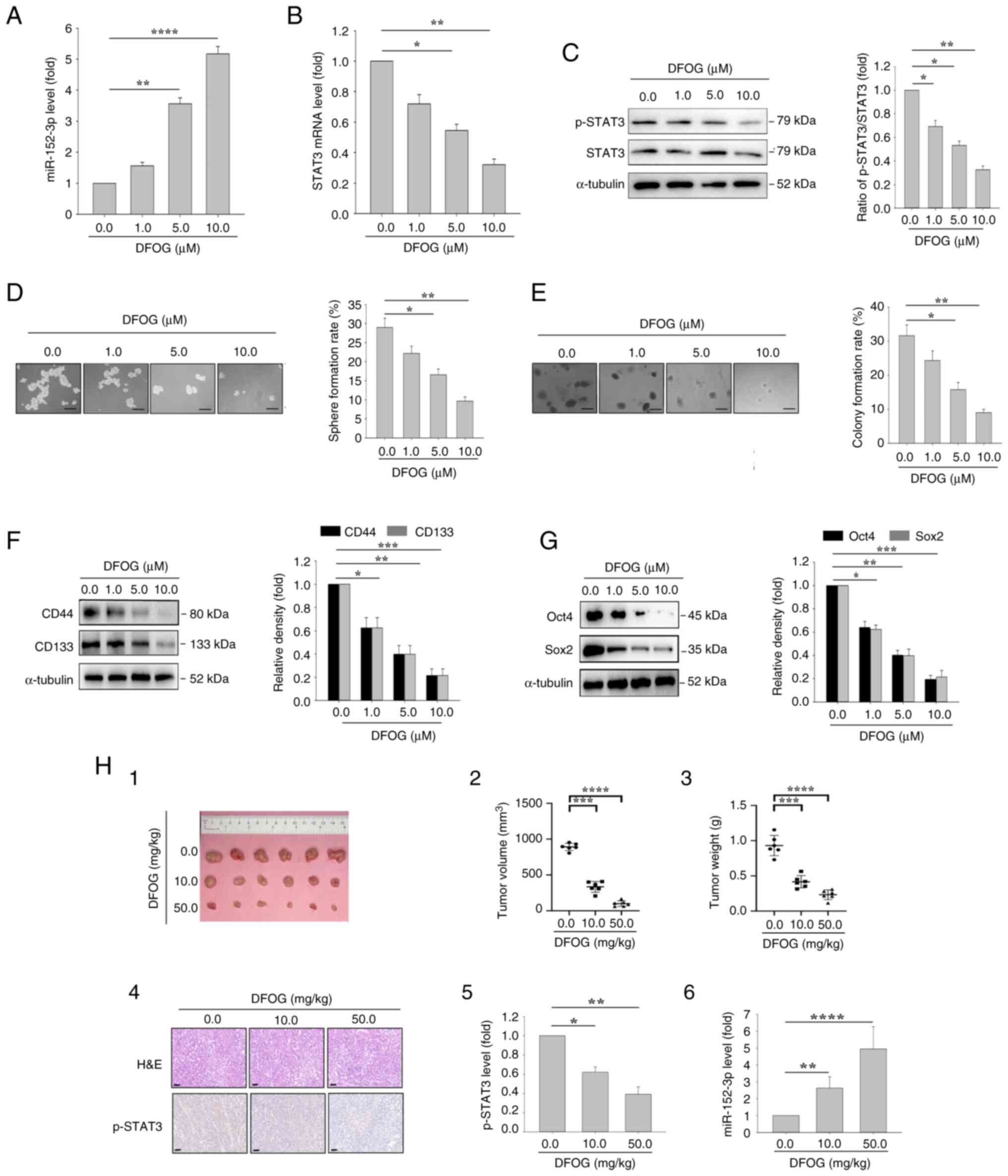

| Figure 2.DFOG induces miR-152-3p expression,

and inhibits self-renewal and tumor growth in H460-derived SFCs. At

the indicated concentrations, DFOG (A) upregulated miR-152-3p

expression, and (B) decreased STAT3 mRNA expression and (C) p-STAT3

protein levels in H460-derived SFCs. (D) Sphere formation and (E)

colony formation were reduced (scale bar, 100 µm). Western blot

analysis showed downregulation of (F) CD44 and CD133 expression, as

well as (G) Oct4 and Sox2 expression. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01,***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 (n=3). (H) (1) Images of tumor tissue; (2) volume quantification; (3) weight quantification; (4) H&E staining and immunohistochemical

staining using an anti-p-STAT3 antibody (scale bar, 50 µm).

(5) Quantification of p-STAT3

protein levels and (6) miR-152-3p

levels in xenograft tumors of nude mice bearing H460-derived SFCs

treated with DFOG at the indicated doses. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. DFOG,

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octylygenistein; miR, microRNA; p-,

phosphorylated; SFC, sphere-forming cell. |

To evaluate the effect of DFOG on self-renewal and

tumor growth in NSCLC, sphere formation and colony formation assays

were performed. DFOG treatment led to reduced sphere (Fig. 2D) and colony (Fig. 2E) formation rates in H460-derived

SFCs. Additionally, the protein levels of the stem cell markers

CD133 and CD44 were significantly decreased (Fig. 2F). Consistent with these results,

DFOG treatment substantially decreased the protein levels of Oct4

and Sox2 (Fig. 2G) in H460-derived

SFCs.

For in vivo assessment, DFOG was orally

administered to mice with H460-derived SFC xenograft tumors, with

DMSO administered in the control group. The volumes of xenografts

are shown in Table II and the

maximum diameter is shown in Table

III. As shown in Fig. 2H-1, −2

and −3, DFOG significantly suppressed the growth of xenograft

tumors. Mechanistically, DFOG exerted a dual effect by reducing the

p-STAT3 levels (Fig. 2H-4 and −5)

and enhancing miR-152-3p expression (Fig. 2H-6). These results suggested that

DFOG inhibited the self-renewal and tumor growth of H460-derived

SFCs both in vitro and in vivo, likely through

modulation of miR-152-3p and its target, STAT3.

| Table II.Maximum volume of the xenograft

(mm3) in each mouse across all experimental groups. |

Table II.

Maximum volume of the xenograft

(mm3) in each mouse across all experimental groups.

| DFOG (0 mg/kg) | DFOG (10

mg/kg) | DFOG (50

mg/kg) |

|---|

| 953.06 | 408.32 | 166.08 |

| 884.01 | 367.26 | 105.36 |

| 877.36 | 316.19 | 115.17 |

| 896.21 | 402.42 | 62.97 |

| 806.09 | 309.19 | 88.68 |

| 931.01 | 207.37 | 60.69 |

| Table III.Maximum diameter measured of the

xenograft (mm) in each mouse across all experimental groups. |

Table III.

Maximum diameter measured of the

xenograft (mm) in each mouse across all experimental groups.

| DFOG (0 mg/kg) | DFOG (10

mg/kg) | DFOG (50

mg/kg) |

|---|

| 14.56 | 11.23 | 6.32 |

| 13.09 | 10.21 | 5.21 |

| 13.32 | 9.68 | 5.69 |

| 12.25 | 8.99 | 4.62 |

| 14.32 | 8.32 | 5.17 |

| 14.87 | 7.96 | 4.16 |

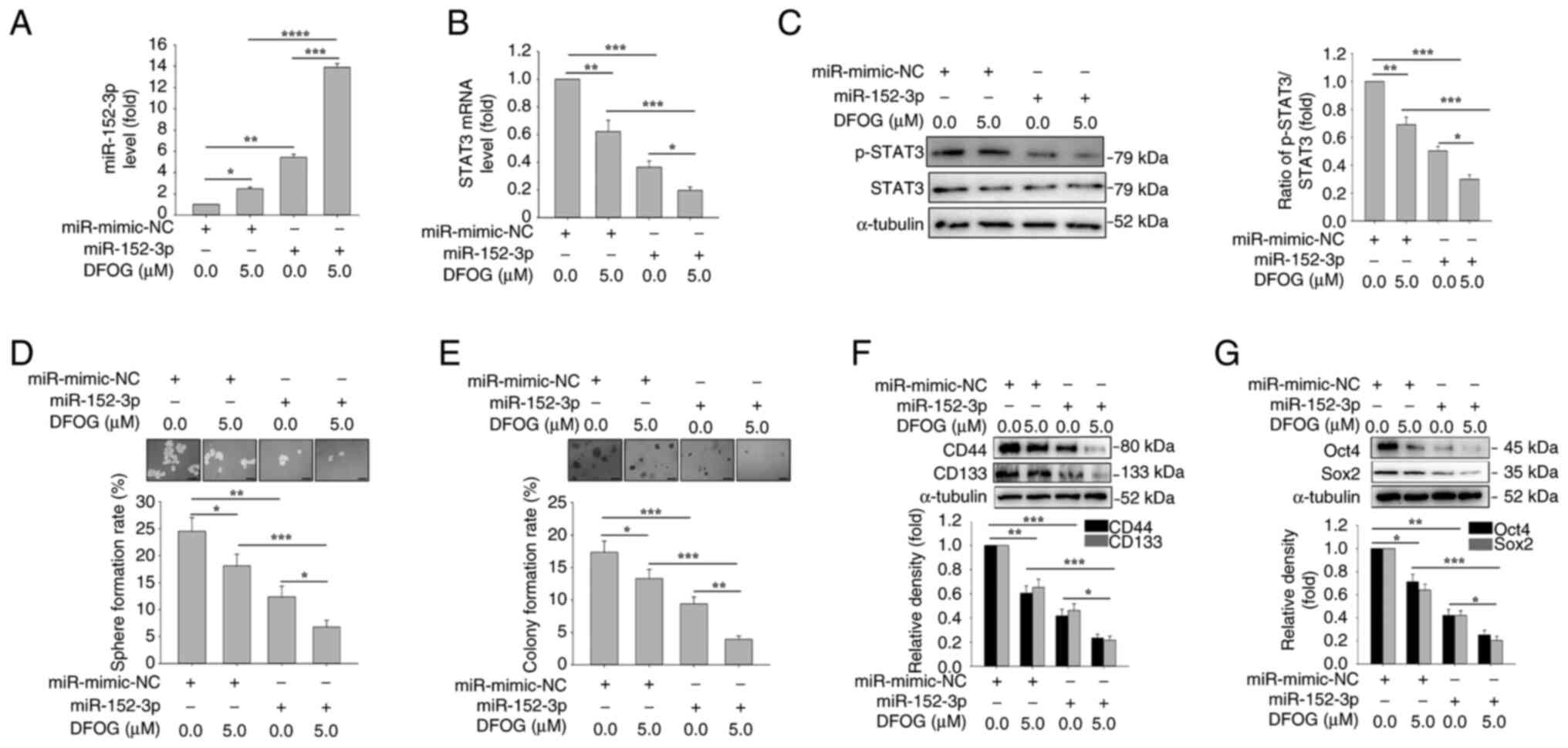

miR-152-3p mimic increases

DFOG-induced suppression of p-STAT3 and self-renewal

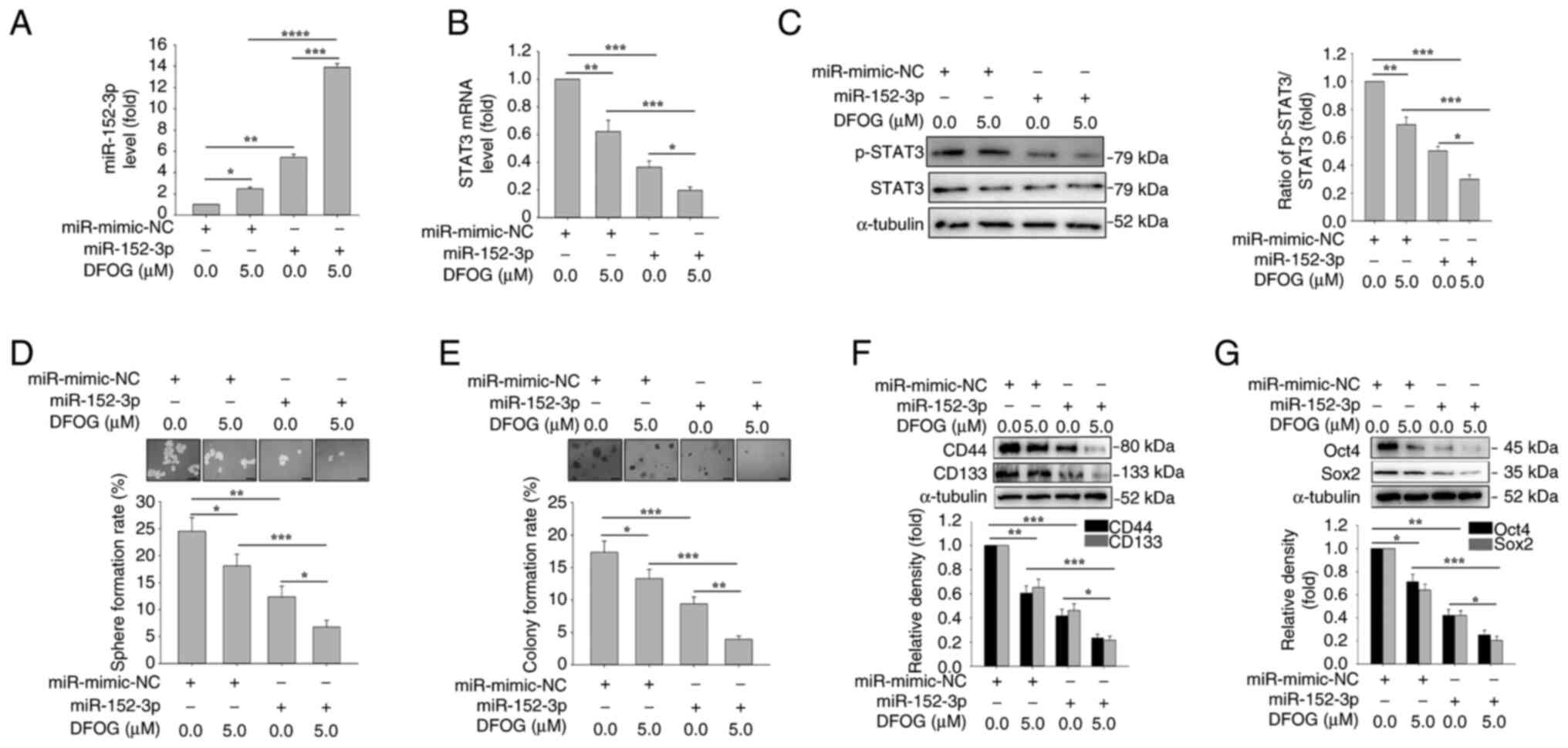

To further elucidate the role of miR-152-3p

regulation in DFOG-mediated suppression of self-renewal,

H460-derived SFCs were transfected with a miR-152-3p mimic. As

shown in Fig. 3A, the miR-152-3p

mimic, in combination with DFOG (5 µM), elevated miR-152-3p

expression. Furthermore, both DFOG (5 µM) and the miR-152-3p mimic

synergistically reduced STAT3 mRNA levels and p-STAT3 protein

levels (Fig. 3B and C). Notably,

miR-152-3p overexpression enhanced the inhibitory effects of DFOG

on self-renewal, leading to a reduction in sphere (Fig. 3D) and colony (Fig. 3E) formation rates compared with the

control group (0 µM). The combined action of miR-152-3p and DFOG

resulted in decreased expression of the stemness markers CD133 and

CD44 (Fig. 3F), as well as the

pluripotent factors Oct4 and Sox2 (Fig.

3G). These results suggested that DFOG elevated miR-152-3p

expression, which in turn suppressed STAT3 transcription and

activity, thereby inhibiting self-renewal in H460-derived SFCs.

| Figure 3.miR-152-3p mimic enhances

DFOG-induced downregulation of p-STAT3 levels and inhibits

self-renewal in H460-derived SFCs. Expression levels of (A)

miR-152-3p and (B) STAT3 mRNA, and (C) p-STAT3 protein levels. (D)

Spheres and (E) colonies formed were quantified (scale bar, 100

µm). Western blot analysis of (F) CD44 and CD133, as well as (G)

Oct4 and Sox2 expression in H460-derived SFCs transfected with

miR-152-3p mimic and/or treated with DFOG (5 µM). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 (n=3). DFOG,

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octylygenistein; miR, microRNA; NC,

negative control; p-, phosphorylated; SFC, sphere-forming cell. |

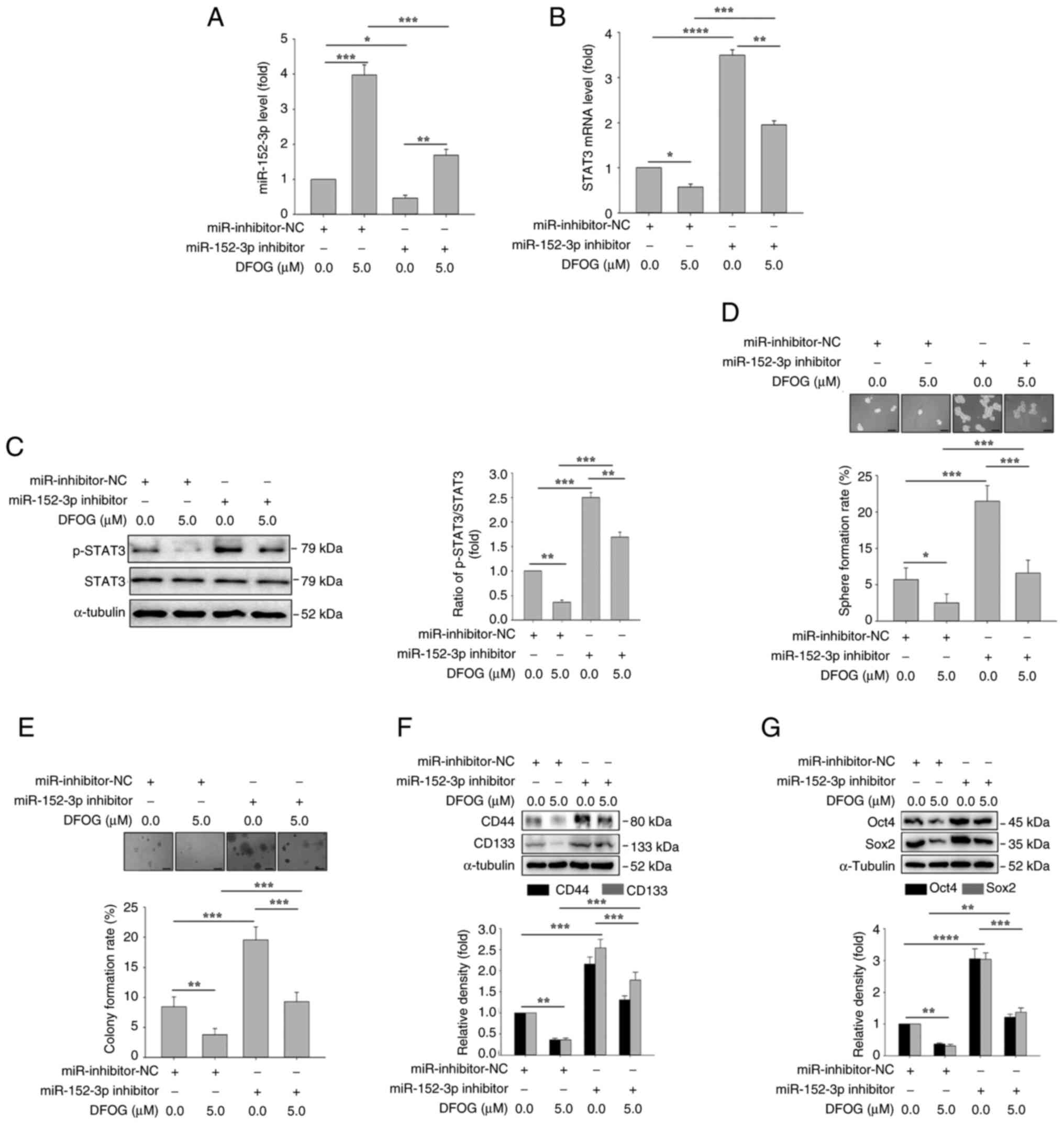

miR-152-3p inhibitor antagonizes

DFOG-induced suppression of p-STAT3 expression and

self-renewal

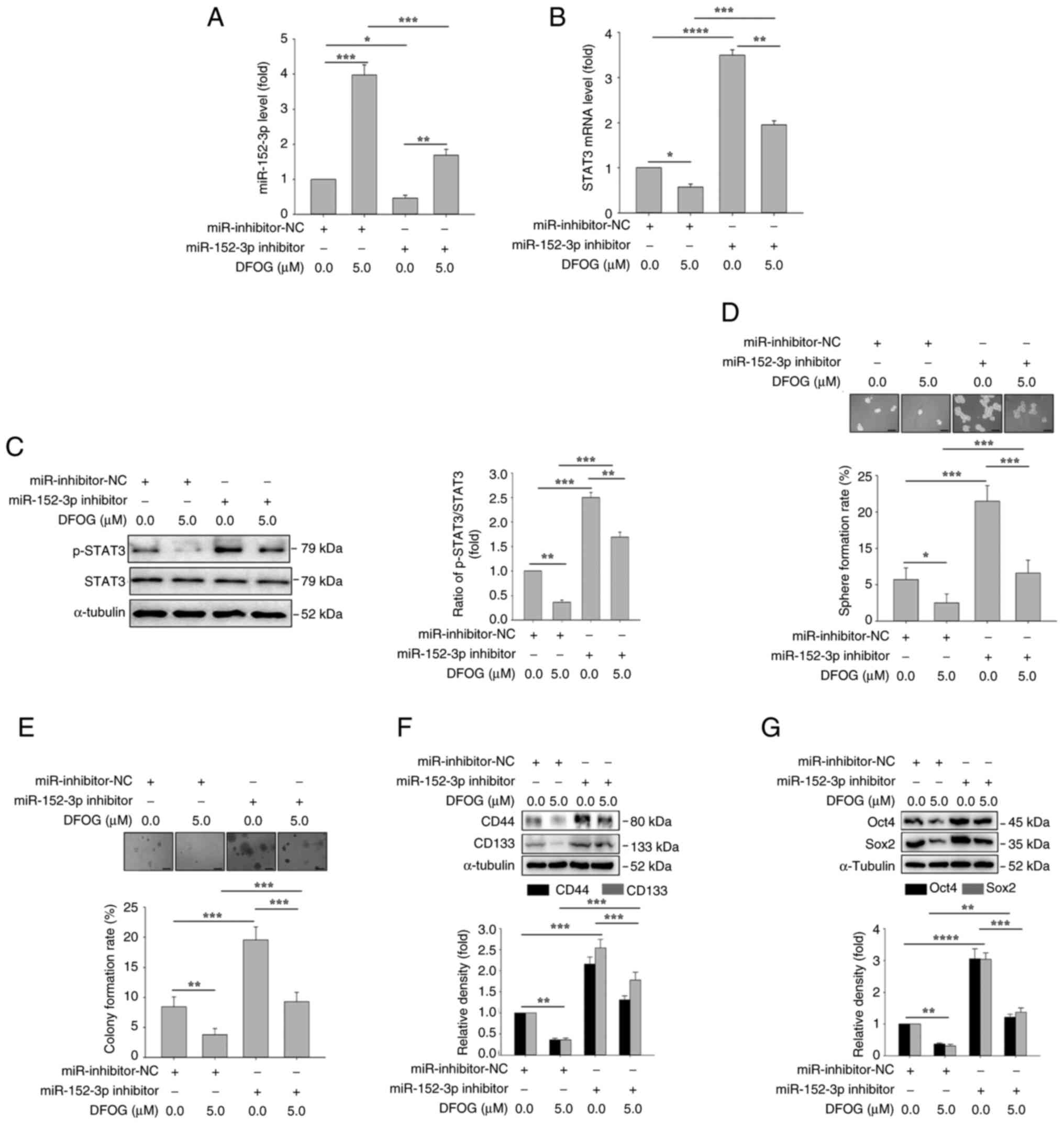

To further validate the role of miR-152-3p

regulation in DFOG-induced suppression of self-renewal,

H460-derived SFCs were transfected with miR-152-3p inhibitor or

miR-inhibitor-NC, followed by treatment with or without DFOG (5

µM). As shown in Fig. 4A,

miR-152-3p inhibitor transfection effectively reversed the

DFOG-induced increase in miR-152-3p expression. Additionally,

miR-152-3p inhibitor counteracted the reduction in STAT3 mRNA

expression and p-STAT3 protein levels induced by DFOG (Fig. 4B and C). Notably, miR-152-3p

inhibitor mitigated the inhibitory effects of DFOG on self-renewal,

as evidenced by an increase in sphere (Fig. 4D) and colony formation rates

(Fig. 4E). miR-152-3p inhibitor

transfection also increased the expression of the

stemness-associated markers CD133 and CD44 (Fig. 4F), and the pluripotent factors Oct4

and Sox2 (Fig. 4G), reversing the

suppressive effect of DFOG. These results suggested that inhibiting

the expression of miR-152-3p could counteract the inhibition of

p-STAT3 activity and self-renewal induced by DFOG treatment in

H460-derived SFCs.

| Figure 4.miR-152-3p inhibitor antagonizes

DFOG-induced suppression of p-STAT3 levels and self-renewal in

H460-derived SFCs. Expression levels of (A) miR-152-3p and (B)

STAT3 mRNA, and (C) p-STAT3 protein levels. (D) Spheres and (E)

colonies formed were quantified (scale bar, 100 µm). Western blot

analysis of (F) CD44 and CD133, as well as (G) Oct4 and Sox2

expression in H460-derived SFCs transfected with miR-152-3p

inhibitor and/or treated with DFOG (5 µM). *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 (n=3). DFOG,

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octylygenistein; miR, microRNA; NC,

negative control; p-, phosphorylated; SFC, sphere-forming cell. |

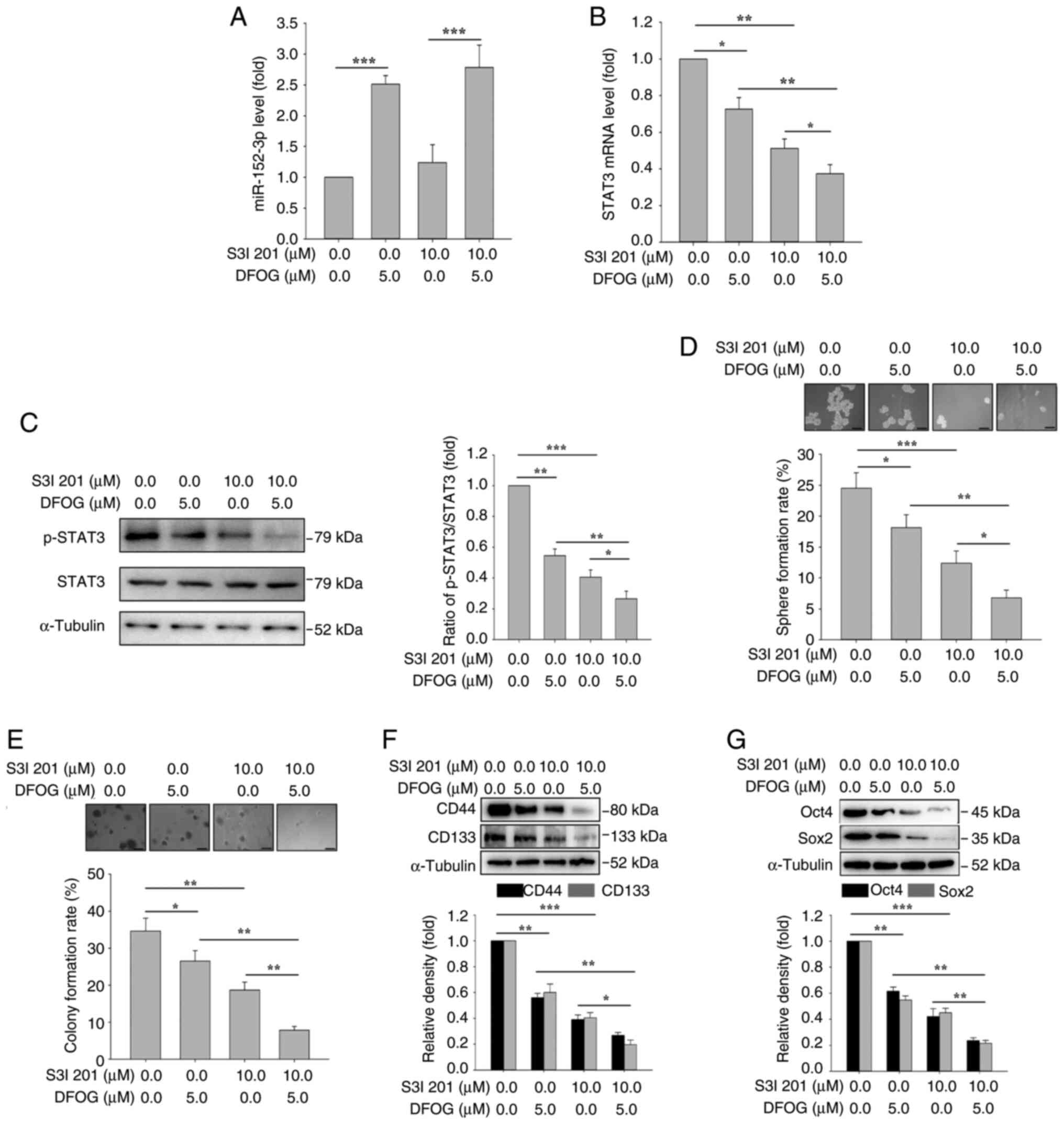

STAT3 inhibitor increases DFOG-induced

self-renewal

To investigate whether the DFOG-induced suppression

of self-renewal was linked to the regulation of STAT3 mRNA

expression and activity, H460-derived SFCs were treated with S3I

201, a specific STAT3 inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 5A, S3I 201 (10 µM) treatment did not

affect the DFOG-induced elevation of miR-152-3p expression.

However, as illustrated in Fig. 5B and

C, S3I 201 (10 µM), in combination with DFOG (5 µM),

effectively decreased STAT3 mRNA expression and p-STAT3 protein

levels. Inhibition of STAT3 activity enhanced the suppressive

effects of DFOG on self-renewal compared with S3I 201 (10 µM) or

DFOG (5 µM) treatment alone, leading to a significant reduction in

sphere (Fig. 5D) and colony

(Fig. 5E) formation rates.

Furthermore, the combination of S3I 201 and DFOG resulted in

decreased protein levels of the stemness markers CD133 and CD44

(Fig. 5F), as well as the

pluripotent factors Oct4 and Sox2 (Fig.

5G). These results highlighted that modulation of STAT3 mRNA

expression and activity by DFOG contributed to the suppression of

self-renewal in H460-derived SFCs.

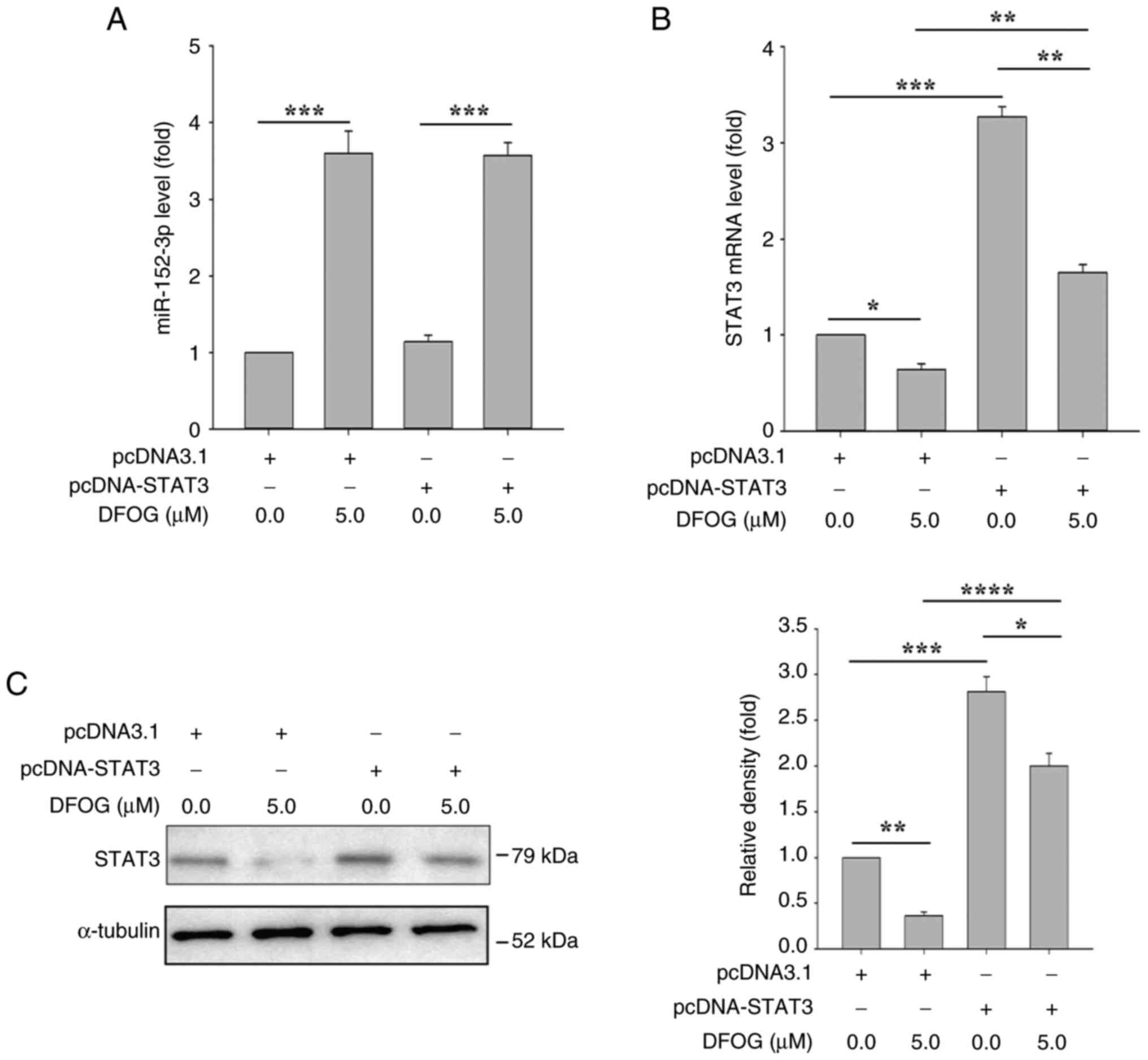

STAT3 overexpression does not

significantly affect miR-152-3p expression

To verify the upstream and downstream relationship

between miR-152-3p and STAT3, H460-derived SFCs were transfected

with STAT3 cDNA and pcDNA3.1, followed by treatment with or without

DFOG (5 µM). As shown in Fig. 6A,

transfection with STAT3 cDNA did not affect the miR-152-3p

expression induced by DFOG. However, STAT3 cDNA transfection

significantly counteracted the reduction in STAT3 mRNA and protein

levels caused by DFOG (Fig. 6B and

C).

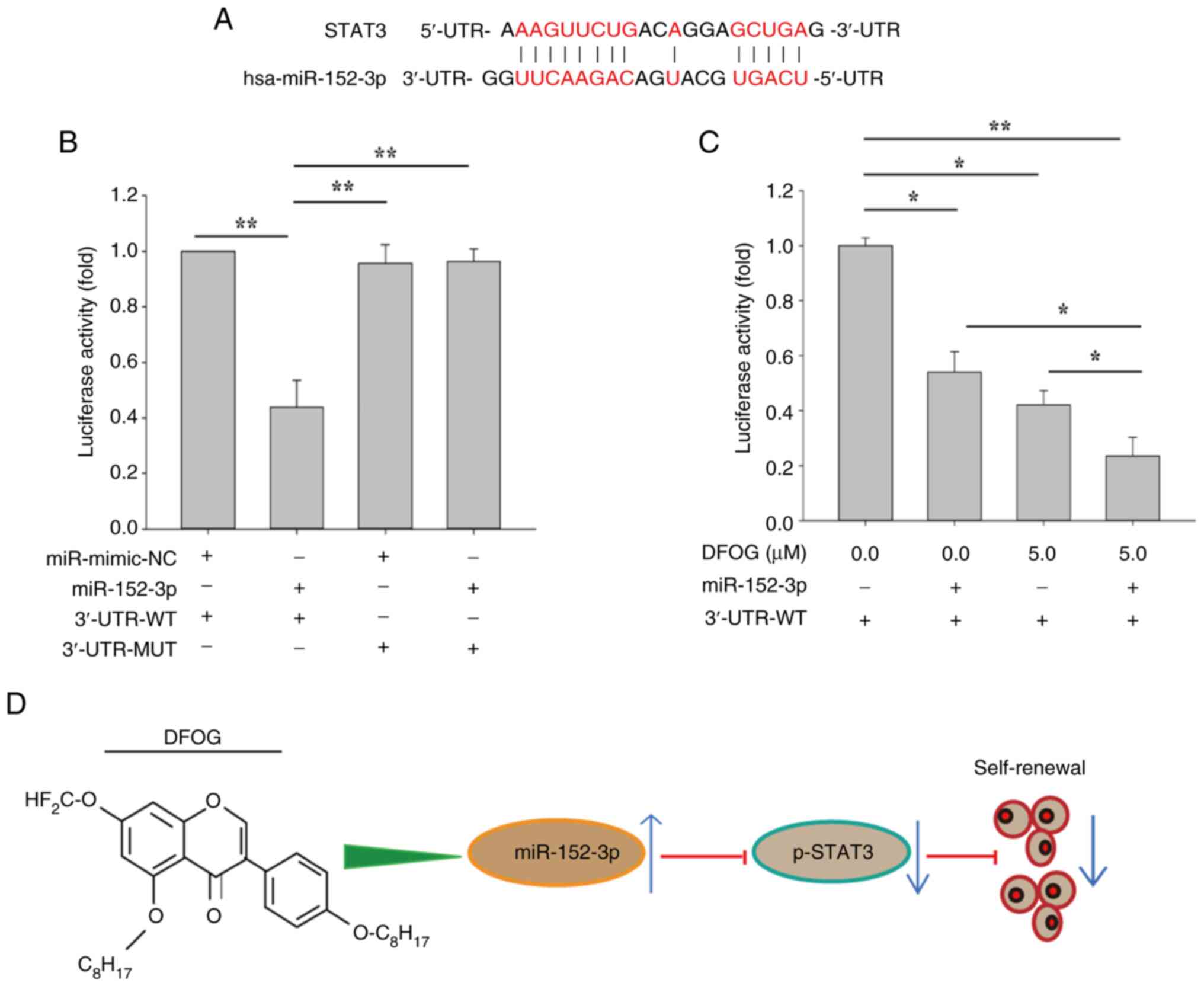

miR-152-3p mimic suppresses the

transcriptional activity of STAT3

To determine whether miR-152-3p directly targets

STAT3, a luciferase reporter assay was conducted in H460-derived

SFCs to identify the specific binding site of the miR-152-3p seed

sequence on the 3′-UTR of STAT3 mRNA. RNAhybrid predicted binding

sites for miR-152-3p and STAT3 (Fig.

7A). As shown in Fig. 7B,

luciferase activity was reduced in cells co-transfected with the

miR-152-3p mimic and STAT3-3′-UTR-WT, while no change in luciferase

activity was observed following co-transfection with

STAT3-3′-UTR-MUT. Additionally, the luciferase activity was further

decreased in NSCLC cells co-transfected with miR-152-3p mimic and

STAT3-3′-UTR-WT after DFOG (5 µM) treatment, compared with cells

treated with miR-152-3p mimic or DFOG alone (Fig. 7C). These results demonstrated that

DFOG inhibited self-renewal by upregulating miR-152-3p, which

directly suppressed STAT3 expression by disrupting its

transcriptional activity (Fig.

7D).

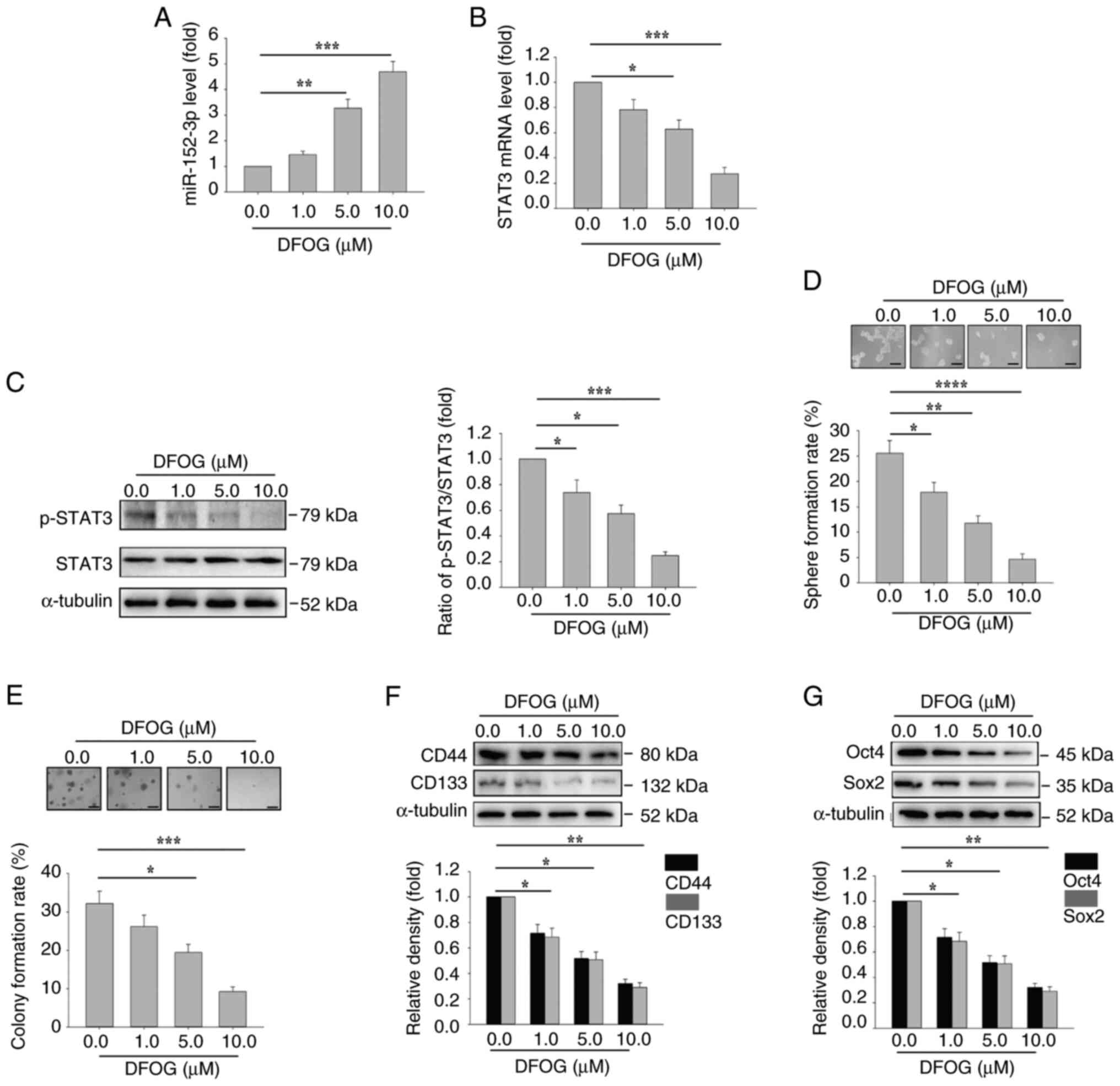

DFOG halts self-renewal in

A549-derived SFCs

The inhibitory effect of DFOG on self-renewal was

also assessed in A549-derived SFCs. Consistently, DFOG

dose-dependently increased miR-152-3p expression, and downregulated

STAT3 mRNA expression and p-STAT3 protein levels in A549 cells

(Fig. 8A-C). Additionally, sphere

formation (Fig. 8D) and colony

formation (Fig. 8E) rates, as well

as the expression of the stem cell markers CD44 and CD133 (Fig. 8F), and the pluripotent factors Oct4

and Sox2 (Fig. 8G), were all

suppressed. These results indicated that DFOG-induced inhibition of

self-renewal in A549-derived SFCs was mediated through the

upregulation of miR-152-3p, and the suppression of STAT3 mRNA and

activity.

| Figure 8.DFOG induces miR-152-3p expression,

and inhibits STAT3 activation and self-renewal in A549-derived

SFCs. At the indicated concentrations, DFOG (A) upregulated

miR-152-3p expression, and decreased (B) STAT3 mRNA expression and

(C) p-STAT3 protein levels in A549-derived SFCs. (D) Spheres and

(E) colonies formed were quantified (scale bar, 100 µm). Western

blot analysis of (F) CD44 and CD133, as well as (G) Oct4 and Sox2

expression in A549-derived SFCs. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 (n=3). DFOG,

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octylygenistein; miR, microRNA; p-,

phosphorylated; SFC, sphere-forming cell. |

Discussion

The present study provided evidence that DFOG

inhibited self-renewal and tumor growth in NSCLC cells by

upregulating miR-152-3p, thereby suppressing the expression and

activity of STAT3. These findings have substantial implications for

the potential use of DFOG as a therapeutic strategy for human

NSCLC, particularly targeting cancer cells with

self-renewal-related stemness properties.

Dysregulated miRNA expression contributes to the

progression of breast cancer, liver cancer and lung cancer

(31,35–37,40,41).

Reduced miR-152-3p expression has been linked to multiple aspects

of malignancy, including progression, proliferation, invasion and

metastasis, in colon cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer and

ovarian cancer (22–25). However, further investigation is

required, particularly in lung cancer. Our results demonstrated

that DFOG upregulated miR-152-3p, miR-34a-5p and miR-148a-3p, with

miR-152-3p exhibiting the most pronounced increase. To the best of

our knowledge, the present study was the first to report that DFOG

enhanced self-renewal and tumor growth traits in NSCLC cells by

elevating miR-152-3p expression, thus revealing a novel mechanism

through which DFOG exerts its inhibitory effects on self-renewal

and tumor growth. Furthermore, the molecular mechanisms underlying

DFOG-induced suppression of tumor cells involve multiple signaling

pathways, including the inactivation of FoxM1 and NF-κB (17,18).

One study indicated that the expression of miR-152 and STAT3 was

associated with poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer

(31). STAT3, an oncogenic

transcription factor mediating signaling from the cell surface to

the nucleus, is frequently upregulated in various malignancies,

including NSCLC (29,30). Notably, targeting STAT3 has been

shown to reduce tumor stem cell properties (30,41,42).

In the present study, a luciferase reporter assay identified STAT3

as a direct target of miR-152-3p. This finding was further

corroborated by the reduced transcription of STAT3 following

combined treatment with DFOG and a miR-152-3p mimic in H460-derived

SFCs. The present results demonstrated that DFOG-induced

upregulation of miR-152-3p inhibited self-renewal and tumor growth

by downregulating STAT3 expression at the mRNA level and impairing

its activity, as evidenced by decreased p-STAT3 protein levels in

H460-derived SFCs. Overexpression of STAT3 reversed this effect,

highlighting the interconnection among DFOG, miR-152-3p and STAT3.

Collectively, these findings suggested that the inhibitory effects

of DFOG on self-renewal and tumor growth were mediated through

miR-152-3p upregulation and STAT3 downregulation, underscoring its

potential as a preventive and therapeutic agent for NSCLC,

particularly in targeting self-renewing tumor cells.

In conclusion, the present study elucidated the

mechanism by which DFOG targeted STAT3 through miR-152-3p

upregulation, effectively suppressing self-renewal and tumor growth

in NSCLC. Therefore, DFOG may be a promising candidate for novel

preventive and therapeutic interventions for NSCLC in humans.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Science and Technology

Innovation Leading Academics of National High-level Personnel of

Special Support Program from Ministry of Science and Technology,

P.R. China (grant no. GKFZ-2018-29), Department of Science and

Technology of Guizhou Province [grant no. QKHJC-ZK(2022)-YB-666],

and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant no.

2021JJ30462).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QY, XL and XC conducted the experiments, contributed

to data collection and drafted the manuscript. JX and JZ performed

the data analysis and contributed to the study design. XL, XC and

JX provided resources. JZ and QY confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal studies were approved (approval no.

D2023045) by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University

(Changsha, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

DFOG

|

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octylygenistein

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung carcinoma

|

|

p-STAT3

|

phosphorylated-STAT3

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:7–33. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chansky K, Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG,

Rusch VW, Vallières E, Groome P, Kennedy C, Krasnik M, Peake M,

Shemanski L, et al: The IASLC lung cancer staging project: External

validation of the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the eighth

edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol.

12:1109–1121. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang C, Wu Y, Shao J, Liu D and Li W:

Clinicopathological variables influencing overall survival,

recurrence and post-recurrence survival in resected stage I

non-small-cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 20:1502020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang X, Chen Y, Wang X, Tian H, Wang Y,

Jin J, Shan Z, Liu Y, Cai Z, Tong X, et al: Stem cell factor SOX2

confers ferroptosis resistance in lung cancer via upregulation of

SLC7A11. Cancer Res. 81:5217–5229. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Clara JA, Monge C, Yang Y and Takebe N:

Targeting signalling pathways and the immune microenvironment of

cancer stem cells-a clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

17:204–232. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Schaal CM, Bora-Singhal N, Kumar DM and

Chellappan SP: Regulation of Sox2 and stemness by nicotine and

electronic-cigarettes in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer.

17:1492018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sunayama J, Matsuda K, Sato A, Tachibana

K, Suzuki K, Narita Y, Shibui S, Sakurada K, Kayama T, Tomiyama A

and Kitanaka C: Crosstalk between the PI3K/mTOR and MEK/ERK

pathways involved in the maintenance of self-renewal and

tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Stem Cells.

28:1930–1939. 2010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nimmakayala RK, Leon F, Rachagani S, Rauth

S, Nallasamy P, Marimuthu S, Shailendra GK, Chhonker YS, Chugh S,

Chirravuri R, et al: Metabolic programming of distinct cancer stem

cells promotes metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Oncogene. 40:215–231. 202 View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sharif T, Martell E, Dai C, Singh SK and

Gujar S: Regulation of the proline regulatory axis and autophagy

modulates stemness in TP73/p73 deficient cancer stem-like cells.

Autophagy. 15:934–936. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kaufhold S, Garbán H and Bonavida B: Yin

Yang 1 is associated with cancer stem cell transcription factors

(SOX2, OCT4, BMI1) and clinical implication. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

35:842016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Walcher L, Kistenmacher AK, Suo H, Kitte

R, Dluczek S, Strauß A, Blaudszun AR, Yevsa T, Fricke S and

Kossatz-Boehlert U: Cancer stem cells-Origins and biomarkers:

Perspectives for targeted personalized therapies. Front Immunol.

11:12802020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Fu Z, Cao X, Yang Y, Song Z, Zhang J and

Wang Z: Upregulation of FoxM1 by MnSOD overexpression contributes

to cancer Stem-like cell characteristics in the lung cancer H460

cell line. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 17:15330338187896352018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu F, Cao X, Liu Z, Guo H, Ren K, Quan M,

Zhou Y, Xiang H and Cao J: Casticin suppresses self-renewal and

invasion of lung cancer stem-like cells from A549 cells through

down-regulation of pAkt. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai).

46:15–21. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wei D, Yang L, Lv B and Chen L: Genistein

suppresses retinoblastoma cell viability and growth and induces

apoptosis by upregulating miR-145 and inhibiting its target ABCE1.

Mol Vis. 23:385–394. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ma CH, Zhang YX, Tang LH, Yang XJ, Cui WM,

Han CC and Ji WY: MicroRNA-1469, a p53-responsive microRNA promotes

Genistein induced apoptosis by targeting Mcl1 in human laryngeal

cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 106:665–671. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhang L, Zhang J, Gong Y and Lv L:

Systematic and experimental investigations of the anti-colorectal

cancer mediated by genistein. Biofactors. 46:974–982. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ning Y, Xu M, Cao X, Chen X and Luo X:

Inactivation of AKT, ERK and NF-κB by genistein derivative,

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octylygenistein, reduces ovarian

carcinoma oncogenicity. Oncol Rep. 38:949–958. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xiang HL, Liu F, Quan MF, Cao JG and Lv Y:

7-difluoromethoxyl-5,4′-di-n-octyl genistein inhibits growth of

gastric cancer cells through down-regulating forkhead box M1. World

J Gastroenterol. 18:4618–4626. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ren W, Hou J, Yang C, Wang H, Wu S, Wu Y,

Zhao X and Lu C: Extracellular vesicles secreted by hypoxia

pre-challenged mesenchymal stem cells promote non-small cell lung

cancer cell growth and mobility as well as macrophage M2

polarization via miR-21-5p delivery. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

38:622019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li P, Xing W, Xu J, Yuan D, Liang G, Liu B

and Ma H: microRNA-301b-3p downregulation underlies a novel

inhibitory role of long non-coding RNA MBNL1-AS1 in non-small cell

lung cancer. Stem Cell Res Ther. 10:1442019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xie C, Zhu J, Jiang Y, Chen J, Wang X,

Geng S, Wu J, Zhong C, Li X and Meng Z: Sulforaphane inhibits the

acquisition of tobacco Smoke-induced lung cancer stem cell-like

properties via the IL-6/ΔNp63α/Notch axis. Theranostics.

9:4827–4840. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lai SW, Chen MY, Bamodu OA, Hsieh MS,

Huang TY, Yeh CT, Lee WH and Cherng YG: Exosomal lncRNA PVT1/VEGFA

axis promotes colon cancer metastasis and stemness by

downregulation of tumor suppressor miR-152-3p. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2021:99598072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jiang CF, Xie YX, Qian YC, Wang M, Liu LZ,

Shu YQ, Bai XM and Jiang BH: TBX15/miR-152/KIF2C pathway regulates

breast cancer doxorubicin resistance via promoting PKM2

ubiquitination. Cancer Cell Int. 21:5422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Moya L, Meijer J, Schubert S, Matin F and

Batra J: Assessment of miR-98-5p, miR-152-3p, miR-326 and miR-4289

expression as biomarker for prostate cancer diagnosis. Int J Mol

Sci. 20:11542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lyu M, Li X, Shen Y, Lu J, Zhang L, Zhong

S and Wang J: CircATRNL1 and circZNF608 inhibit ovarian cancer by

sequestering miR-152-5p and encoding protein. Front Genet.

13:7840892022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yuan Q, Wang R, Li X, Sun F, Lin J, Fu Z

and Zhang J: DNMT1/miR-152-3p/SOS1 signaling axis promotes

self-renewal and tumor growth of cancer stem-like cells derived

from non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 16:552024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhao L, Wu X, Zhang Z, Fang L, Yang B and

Li Y: ELF1 suppresses autophagy to reduce cisplatin resistance via

the miR-152-3p/NCAM1/ERK axis in lung cancer cells. Cancer Sci.

114:2650–2663. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Huang J, Lou J, Liu X and Xie Y: LncRNA

PCGsEM1 contributes to the proliferation, migration and invasion of

Non-small cell lung cancer cells via acting as a sponge for

miR-152-3p. Curr Pharm Des. 27:4663–4670. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Huang R, Wang S, Wang N, Zheng Y, Zhou J,

Yang B, Wang X, Zhang J, Guo L, Wang S, et al: CCL5 derived from

tumor-associated macrophages promotes prostate cancer stem cells

and metastasis via activating β-catenin/STAT3 signaling. Cell Death

Dis. 11:2342020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ouyang S, Li H, Lou L, Huang Q, Zhang Z,

Mo J, Li M, Lu J, Zhu K, Chu Y, et al: Inhibition of

STAT3-ferroptosis negative regulatory axis suppresses tumor growth

and alleviates chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Redox Biol.

52:1023172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Cao Y, Shi H, Ren F, Jia Y and Zhang R:

Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 promotes metastasis and poor prognosis in

epithelial ovarian cancer. Exp Cell Res. 359:185–194. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Al-Harbi B and Aboussekhra A: Cucurbitacin

I (JSI-124)-dependent inhibition of STAT3 permanently suppresses

the pro-carcinogenic effects of active breast cancer-associated

fibroblasts. Mol Carcinog. 60:242–251. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li X, Wang L, Cao X, Zhou L, Xu C, Cui Y,

Qiu Y and Cao J: Casticin inhibits stemness of hepatocellular

carcinoma cells via disrupting the reciprocal negative regulation

between DNMT1 and miR-148a-3p. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol.

396:1149982020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen MJ, Cheng YM, Chen CC, Chen YC and

Shen CJ: MiR-148a and miR-152 reduce tamoxifen resistance in ER+

breast cancer via downregulating ALCAM. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

483:840–846. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

He WW, Ma HT, Guo X, Wu WM, Gao EJ and

Zhao YH: lncRNA SNHG3 accelerates the proliferation and invasion of

non-small cell lung cancer by downregulating miR-340-5p. J Biol

Regul Homeost Agents. 34:2017–2027. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen Z, Ying J, Shang W, Ding D, Guo M and

Wang H: miR-342-3p regulates the proliferation and apoptosis of

NSCLC cells by targeting BCL-2. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

20:153303382110411932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li YY, Tao YW, Gao S, Li P, Zheng JM,

Zhang SE, Liang J and Zhang Y: Cancer-associated fibroblasts

contribute to oral cancer cells proliferation and metastasis via

Exosome-mediated paracrine miR-34a-5p. EBioMedicine. 36:209–220.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li LW, Xiao HQ, Ma R, Yang M, Li W and Lou

G: miR-152 is involved in the proliferation and metastasis of

ovarian cancer through repression of ERBB3. Int J Mol Med.

41:1529–1535. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chang DL, Wei W, Yu ZP and Qin CK:

miR-152-5p inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of liver

cancer cells by up-regulating FOXO expression. Pharmazie.

72:338–343. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Reichenbach N, Delekate A, Plescher M,

Schmitt F, Krauss S, Blank N, Halle A and Petzold GC: Inhibition of

Stat3-mediated astrogliosis ameliorates pathology in an Alzheimer's

disease model. EMBO Mol Med. 11:e96652019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Liu YX, Xu BW, Niu XD, Chen YJ, Fu XQ,

Wang XQ, Yin CL, Chou JY, Li JK, Wu JY, et al: Inhibition of

Src/STAT3 signaling-mediated angiogenesis is involved in the

anti-melanoma effects of dioscin. Pharmacol Res. 175:1059832022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|