Introduction

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is defined as

histologically confirmed metastatic cancer in which the primary

site cannot be found even after extensive standard investigations

(1). At present, the favorable risk

subgroup for CUP includes patients with neuroendocrine carcinomas

of unknown primary, peritoneal adenocarcinomatosis of a serous

papillary subtype, isolated axillary nodal metastases in female

patients, squamous cell carcinoma involving non-supraclavicular

cervical lymph nodes (LNs), single metastatic deposit from unknown

primary, and men with blastic bone metastases and prostate-specific

antigen expression (2). Novel

favorable subsets of CUP have emerged, including colorectal, lung

and renal CUP, which underlines the importance of cancer-specific

treatments (2). Patients with CUP

who are categorized into the unfavorable subset (~80% of patients)

receive empiric chemotherapy with a platinum-taxane regimen.

However, the prognosis remains poor, with a median survival period

of 6–12 months (3,4). The poor prognosis of CUP is

attributable to its clinical heterogeneity originating from various

types of cancers, which makes a single empiric regimen inefficient

(5).

Our previous randomized controlled study (6) assessed whether site-specific therapy

based on prediction of the primary site may improve the outcomes in

untreated patients with CUP. Genome-wide gene expression profiling

of CUP was performed in the study using a microarray to predict the

primary site in each patient with CUP (6). However, substantial shortcomings have

been identified in the existing research comparing site-specific

treatment and empiric chemotherapy. These deficiencies include

patient accrual problems (oversampling treatment-resistant tumor

types and long recruitment), study design limitations

(observational and problematic trials), heterogeneity among the CUP

classifiers (epigenetic vs. transcriptomic profiling) and

incomparable therapies (7).

Treatment based on the prediction of the primary site did not lead

to any improvement of the overall survival compared with empiric

chemotherapy in our previous study (6); however, gene profiling analyses of

patients with CUP and comparison of the gene expression patterns in

these patients with those in tumors from 24 known primary sites

revealed several genes that were uniquely upregulated in CUP

(8). Of the ~22,000 genes mounted

on the microarray, 44 genes that were upregulated in CUPs were

identified in our previous study (8).

The early metastasis in the natural history of CUP

remains poorly understood. The present study identified genes that

could serve a role in the metastasis in CUP. Small interfering RNA

(siRNA) knockdown screens were used to assess the genes upregulated

in the present CUP cohort to determine their impact on the

migration of cancer cells and further characterize candidate genes

using an in vivo metastasis model.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

The A549 human lung cancer cell line (cat. no.

CCL-185) and the MDA231 breast cancer cell line (cat. no. HTB-26)

were procured from American Type Culture Collection, and cultured

in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 10% FBS

(MilliporeSigma) in accordance with the instructions provided by

the suppliers. The cells were maintained in a 5% CO2

humidified atmosphere at 37°C.

Cell viability assay

The proliferation rate of cultured cells was

analyzed using MTT (MilliporeSigma) as previously described

(9). The assay was performed in

triplicate where applicable.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA (1 µg) from cells, extracted using ISOGEN

(Nippon Gene Co., Ltd.), was converted into cDNA using a GeneAmp

RNA-PCR kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Reverse transcription

was performed at 37°C for 2 h. qPCR was performed using TB Green

Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Bio, Inc.), including TB Green as an

intercalator that emits fluorescence when bound to double-stranded

DNA. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 1 min

and 50 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Quantification

based on the cycle threshold (Ct) values (2−ΔΔCq method)

(10) was performed using an

Applied Biosystems 7900 HT Fast Real-time PCR System (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) as previously described (11). The primers used to amplify the

target genes are listed in Table

SI. GAPDH was used to normalize the expression levels in

quantitative analyses. For the siRNAs listed in Table I, the analyses were conducted once,

but in triplicate in case the migration rate was <50%. For a few

siRNAs that impaired the viability of the cells, it was not

possible to perform the analyses (see below; Table I).

| Table I.Effect of siRNA-induced knockdown of

genes on cell migration. |

Table I.

Effect of siRNA-induced knockdown of

genes on cell migration.

|

|

| A549 cells | MDA231 |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| siRNA | siRNA

(EHU-)a | Viability,

%b | Fold change of the

expression of the gene targeted by the siRNAc | Migration rate,

%d | Viability,

%b | Fold change of the

expression of the gene targeted by the siRNAc | Migration rate,

%d |

|---|

|

Controle | SIC001 | 100.0 | 1.000 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1.000 | 100.0 |

| S100A4 | 125681 | >90.0 | 0.069 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| HSPA8 | 115141 | >90.0 | 0.199 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| TIMP1 | 156431 | >90.0 | 0.069 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| LGALS1 | 034721 | >90.0 | 0.035 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| SERF2 | 096201 | >90.0 | 0.559±0.033 | 44.3±8.1 | >90.0 | 0.652 | >90.0 |

| PRKDC | 123791 | 51.0±3.1 | 0.087±0.020 | <1.0 | 75.2±2.9 | 0.107±0.018 | 1.9±1.5 |

| NEDD8 | 112521 | >90.0 | 0.008 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| APOC | 125971 | >90.0 | 0.314 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| YWHAZ | 076001 | >90.0 | 0.363 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| SUB1 | 031131 | >90.0 | 0.037 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| NOLA3 | 104671 | >90.0 | 0.044 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| SNRPD2 | 146751 | 50.0±4.6 | 0.019 | 67.2±5.4 |

|

|

|

| ATP5H | 128441 | >90.0 | 0.110 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| TCEB2 | 150621 | >90.0 | 0.034 | 71.7±6.9 |

|

|

|

| OAZ1 | 034471 | >90.0 | 0.044 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| NPIPL3 | 106191 | 79.3±4.0 | 0.953 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| SRGN | 143531 | >90.0 | 0.017 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| S100A6 | 120391 | >90.0 | 0.019 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| PFN1 | 106911 | >90.0 | 0.035 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| EIF5A | 147491 | >90.0 | 0.015 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| S100A11 | 147921 | 46.3±6.4 | 0.017 | 55.6±3.9 |

|

|

|

| NUTF2 | 159321 | 64.7±7.1 | 0.021 | 50.7±2.5 |

|

|

|

| STK17A | 018811 | >90.0 | 0.167 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| YWHAH | 004271 | >90.0 | 0.096 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| SELT | 117491 | >90.0 | 0.017 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| CST3 | 019031 | >90.0 | 0.046 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| GDI2 | 109311 | >90.0 | 0.095 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| VDAC3 | 108731 | >90.0 | 0.048 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| TYROBP | 033221 | >90.0 | 0.346 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| VIM | 151861 | >90.0 | 0.057 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| LSM7 | 057161 | >90.0 | 0.042 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| GSTP1 | 009201 | >90.0 | 0.051 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| NDUFS8 | 053841 | >90.0 | 0.047 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| POLR2J | 117061 | >90.0 | 0.853 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| RPS7 | 110521 | 25.8±2.1 | 0.013±0.005 | <1.0 | <1.0 | n.p. | n.p. |

| RPL11 | 108131 | 18.8±3.2 | 0.002±0.001 | <1.0 | <1.0 | n.p. | n.p. |

| RPLP2 | 055751 | <1.0 | n.p. | n.p. |

|

|

|

| RPL18A | 147231 | <1.0 | n.p. | n.p. |

|

|

|

| RPL36 | 056091 | <1.0 | n.p. | n.p. |

|

|

|

| RPS10 | 110371 | <1.0 | n.p. | n.p. |

|

|

|

| IMP3f | 085841 | 58.2±7.4 | 0.257 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| CALM3f | 143521 | >90.0 | 0.023 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| AP2S1f | 135191 | >90.0 | 0.009 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

|

ARL6IP4f | 087871 | >90.0 | 0.135 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

|

ATP6VOBf | 142591 | >90.0 | 0.038 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

|

SH3GLB1f | 098381 | >90.0 | 0.123±0.011 | 43.9±6.0 | >90.0 | 0.058 | >90.0 |

| CAPNS1f | 047191 | >90.0 | 0.031±0.009 | 15.9±2.3 | >90.0 | 0.022 | >90.0 |

| PGK1f | 105941 | >90.0 | 0.232 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

| PSMB4f | 025191 | >90.0 | 0.051±0.004 | 21.8±2.5 | >90.0 | 0.033±0.008 | 17.3±4.3 |

| PDCD6f | 094521 | >90.0 | 0.030 | >90.0 |

|

|

|

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from cells using RIPA

buffer (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) containing

protease inhibitor mix Complete™ (Roche Diagnostics).

The protein concentrations were determined using a BCA Protein

Assay Kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The proteins

were boiled at 100°C, loaded (20 mg per lane), separated by

SDS-PAGE (5–20%) and transferred to PVDF membranes. After 1 h of

blocking with 3% (w/v) BSA (Merck KGaA) at room temperature, the

membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C.

After being rinsed twice with TBS buffer (pH 8.0) containing 0.1%

Tween-20, the membranes were incubated with HRP-labeled secondary

antibodies against mouse IgG (100-fold dilution; cat. no. 7076;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h. An

enhanced chemiluminescence solution (GE Healthcare) was used for

color development. β-actin was used as the internal standard. The

experiment was performed in triplicate. Antibodies against protein

kinase DNA-activated catalytic subunit (PRKDC)/DNA-dependent

protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PK) (1,000-fold dilution;

cat. no. 12311; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), proteasome

subunit β type-4 (PSMB4) (200-fold dilution; cat. no. sc-390878;

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and β-actin (200-fold dilution;

cat. no. sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were used.

ImageJ software ver. 1.54 g (National Institutes of Health) was

used for densitometry.

Migration assay

The migration assay was performed using the Boyden

chamber method using polycarbonate membranes with a pore size of 8

µm (Chemotaxicell; Kurabo Bio-Medical Department; Kurabo

Industries, Ltd.) as previously described (11). The membranes were coated with

fibronectin (50 µg/ml) on the outer side at room temperature for 1

h and dried for 2 h at room temperature. The cells

(2×104 cells/well) were then seeded into the upper

chambers containing 500 µl migrating medium (DMEM containing 0.5%

FBS), and the upper chambers were placed into the lower chambers

containing 700 µl DMEM with 10% FBS. After incubation at 37°C for

24 h, the media in the upper chambers were aspirated, and the

non-migrated cells on the inner sides of the membranes were removed

using a cotton swab. The cells that had migrated to the outer side

of the membranes were fixed with 100% ethanol at room temperature

for 5 min, stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution at room

temperature for 15 min and observed under a light microscope. The

number of migrated cells in five fields per chamber was averaged.

The migration rate was verified in triplicate for each gene where

applicable (Table I).

Selection of genes for the migration

assay

The selection of genes was based on our previous

expression microarray analysis for CUP (GSE42392) (8), which was compared with microarray

datasets for several cancer types obtained from the Gene Expression

Omnibus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (12). The datasets used were GSE781

(13), GSE1456 (14), GSE2109 (15), GSE2742 (16), GSE3149 (17), GSE3167 (18), GSE4127 (19), GSE4176 (20), GSE5787 (21), GSE6791 (22) and GSE8218 (23).

Transfection of siRNA

Predesigned siRNAs (MISSION® siRNA)

targeting 50 genes and a nonspecific target (MISSION®

siRNA Universal Negative Control; Table

I) were purchased from MilliporeSigma. Cells were transfected

with each siRNA (10 nM) using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions as

previously described (24),

incubated at 37°C for 48 h, and then trypsinized and seeded

immediately for the migration assay.

Plasmid construction, virus production

and stable transfection

shRNAs targeting PRKDC or PSMB4 were constructed

using oligonucleotides encoding siRNA directed against the

respective genes (5′-CCTGAAGTCTTTACAACATATCTC-3′ and

5′-CCGCAACATCTCTCGCATTATCTC-3′ for PRKDC and PSMB4 shRNA,

respectively). The oligonucleotides were cloned into RNAi-Ready

pSIREN RetroQZsGreen (Takara Bio, Inc.), which is a

self-inactivating retroviral expression vector. This dual

expression vector encodes green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the

control of the cytomegalovirus promotor and shRNA under the control

of the U6 promoter. The viral vectors constructed were designated

as pSIREN-shPRKDC, pSIREN-shPSMB4 and a control vector

(pSIREN-RetroQZsGreen vector without oligonucleotide inserted).

Each of the pSIREN-RetroQZsGreen constructs (45 µg) was

co-transfected with a pVSV-G vector (Takara Bio, Inc.) constituting

the viral envelope (molar ratio of 3:1 for pSIREN-RetroQZsGreen

constructs:pVSV-G vector) into GP2-293 packaging cells

(2×107 cells; Takara Bio, Inc.) using the FuGENE6

transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics). After 48 h at 37°C, the

culture medium was collected, and the viral particles were

concentrated by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 3 h at 4°C. The

viral pellet was then resuspended in fresh DMEM. The viral vector

titer was calculated using a Retrovirus Titer Set (Takara Bio,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The minimal MOI

was then determined to be 4 for all the constructs by counting the

GFP-positive A549 cells infected by serial dilutions of the

virus-containing media. At 3 days after the infection with the

virus in A549 cells (1×105 cells), the cells were

trypsinized, propagated for 1 week and resuspended in DMEM

(5×106 cells/ml). Subsequently, 1 ml of the resuspended

solution was processed for cell sorting using a FACSCalibur Flow

Cytometer (BD Biosciences). This device consists of a flow

cytometer and a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) in which

GFP-positive cells excited by the 488 nm laser line emit green

fluorescence at 509 nm, which is optimally detected by the FL-1

detector, and the GFP-positive cells were captured by a catcher

tube for sorting (25). The

software used for analysis was CellQuest software Ver. 3.3 (BD

Biosciences). The subsequent experiment (LN metastasis assay) was

performed immediately after the sorted cells reached the number

required for inoculation into mice (1×107 cells for each

construct) during the culture for ~1 week.

Animal models and LN metastasis

assay

A total of 60 nude mice (BALB/c nu/nu; 5-week-old;

female; mean weight, 17.8 g; CLEA Japan, Inc.) were used for the

in vivo experiments. Experimemts were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care Committee of the Kindai University

Faculty of Medicine (approval no. KDMS-25-019; Osaka-Sayama,

Japan). The mice were housed at the Animal Laboratory, Kindai

University Faculty of Medicine (Osaka-Sayama, Japan), and

maintained in a specific pathogen-free vivarium at 18–23°C with 50%

humidity under a 12/12 h dark/light cycle. The animals had free

access to drinking water and were fed a pelleted basal diet ad

libitum.

The in vivo study consisted of two parts that

estimated two effects on the potential of the cells to metastasize

from footpad to popliteal LN: Experiment 1, the effect of

downregulation of PSMB4 and PRKDC; and experiment 2, the effect of

inhibitors of PSMB4 and PRKDC. For each of them, a single

experiment was performed and 30 mice were used. For experiment 1,

the cells (A549 cells bearing a control vector, pSIREN-shPRKDC, or

pSIREN-shPSMB4) were resuspended in Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution

(MilliporeSigma) and injected subcutaneously (1×106

cells) into the hind footpads of mice (10 mice per group) on day 0

in accordance with the method described for a previous study

(26). On the final day (day 20),

mice were euthanized using CO2 flowing from a compressed

cylinder into a chamber (under ambient conditions) containing the

mice so that 100% CO2 gradually filled the chamber

(30%/min) (27). Next, the primary

tumors and popliteal LNs were visualized by fluorescence imaging

and images were captured using a macro-imaging station consisting

of a SBIG cooled CCD camera model ST-7XME (Santa Barbara Imaging)

mounted onto a dark box. The integrated density of the fluorescence

spots was quantified using ImageJ software ver. 1.54 g (National

Institutes of Health). For experiment 2, the DNA-PK inhibitor

NU7441 (10 mg/kg; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation)

(28) and the proteasome inhibitor

bortezomib (1 mg/kg; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd.) (29), and vehicle (DMSO) were administered

intravenously alone (9–10 mice/group) 1 week after inoculation of

A549 cells bearing a control vector, and this administration was

repeated twice a week for 3 weeks (2nd to 4th weeks). The LNs were

resected (on day 35), and their maximum diameters were measured.

Fluorescence images were also captured for the primary tumors and

popliteal LNs. The animal details and protocol were otherwise as

aforementioned.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD, unless

otherwise noted. An unpaired t-test was used for comparisons

between two groups. Comparisons among multiple groups were

conducted using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls

test. These analyses were performed as a single experiment.

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot v13.0 (Grafiti

LLC). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Selection of candidate genes in

CUP

In our previous microarray study, 44 genes that were

upregulated in CUPs compared with non-CUPs as a whole were

identified (8). Of the 44 genes, 40

were selected as candidates for the next screening using the

migration assay (Table I). Three

pseudogene-like genes (LOC392501, LOC442171 and LOC646417) with

unknown functions and one gene without an available siRNA (LAPTM5)

were excluded. As additional candidates for the screening, 10 genes

that were screened out by the comparison of gene expression

profiles between CUP and individual cancer types of known primary

site were selected (8). These 10

genes were most highly expressed in CUP of all cancer types

examined, and each of the genes showed ≥1.5-fold enriched

expression in CUP compared with the second most enriched cancer

type for each gene (Table SII). A

total of 50 genes were selected (Table

I) for the migration assay.

Screening for genes associated with

the metastatic potential in CUP

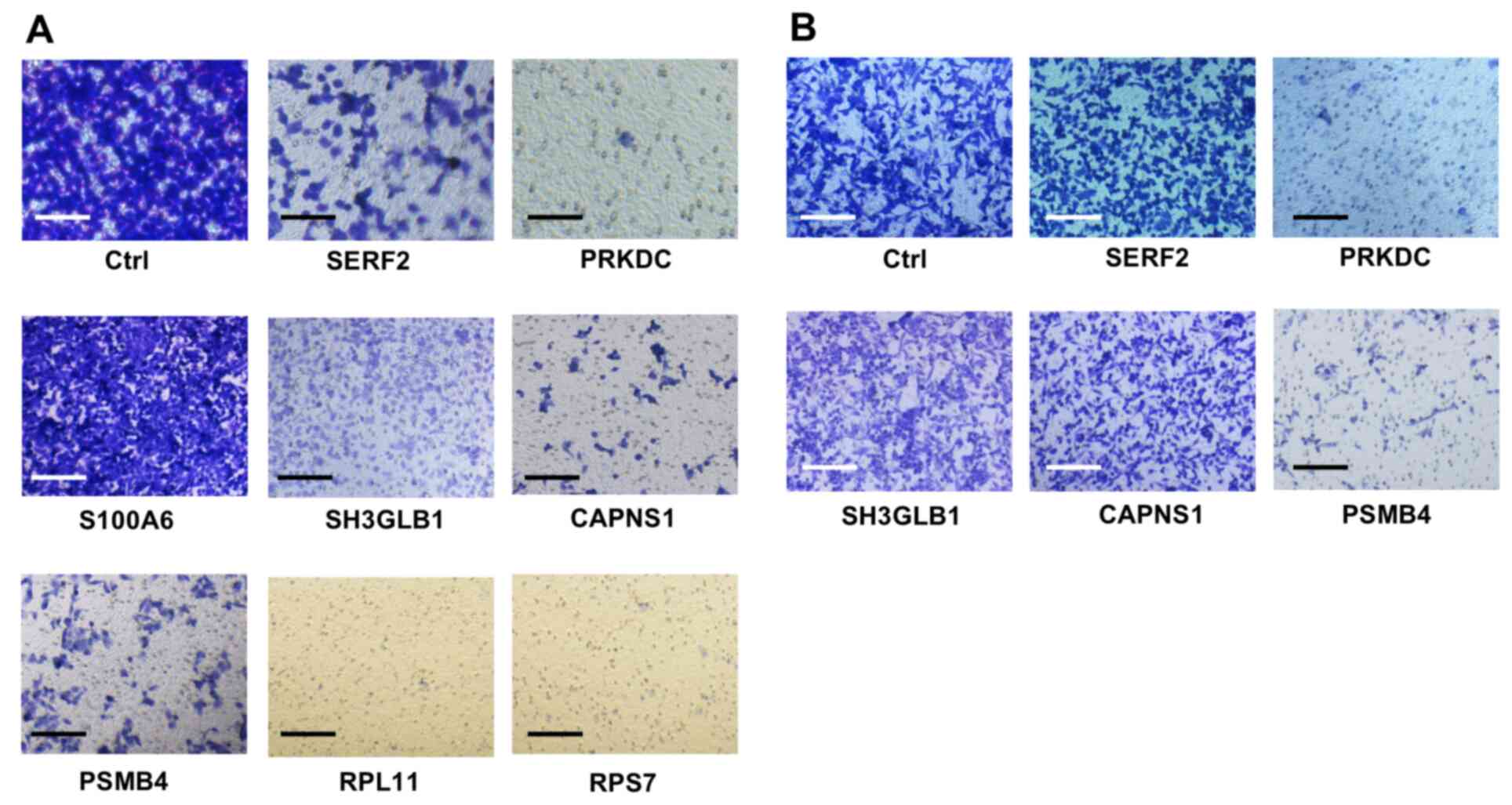

For all 50 aforementioned genes, specific siRNAs

were obtained from the same commercial source (MISSION®

siRNA; Table I). For screening,

A549 cells were transfected with siRNAs, and genes were evaluated

for suppressed migration after siRNA knockdown. Images for cell

migration assays are shown in Figs.

1 and S1. The migration assay

showed that A549 cells transfected with some siRNAs exhibited poor

migration, meaning the number of A549 cells migrating to the outer

side of the porous membrane in the Boyden chamber was decreased

compared with that of the cells transfected with control siRNA

(Fig. 1A). For each of the 50

siRNAs transfected into A549 cells, the present study aimed to

determine the cell viability, the fold-change in the expression of

the targeted gene and the cell migration rate (Table I). The results revealed that

transfection with siRNAs targeting SERF2, PRKDC, SH3GLB1, CAPNS1,

PSMB4, RPS7 and RPL11 reduced the migration of A549 cells by

>50% (Fig. 1A; Table I).

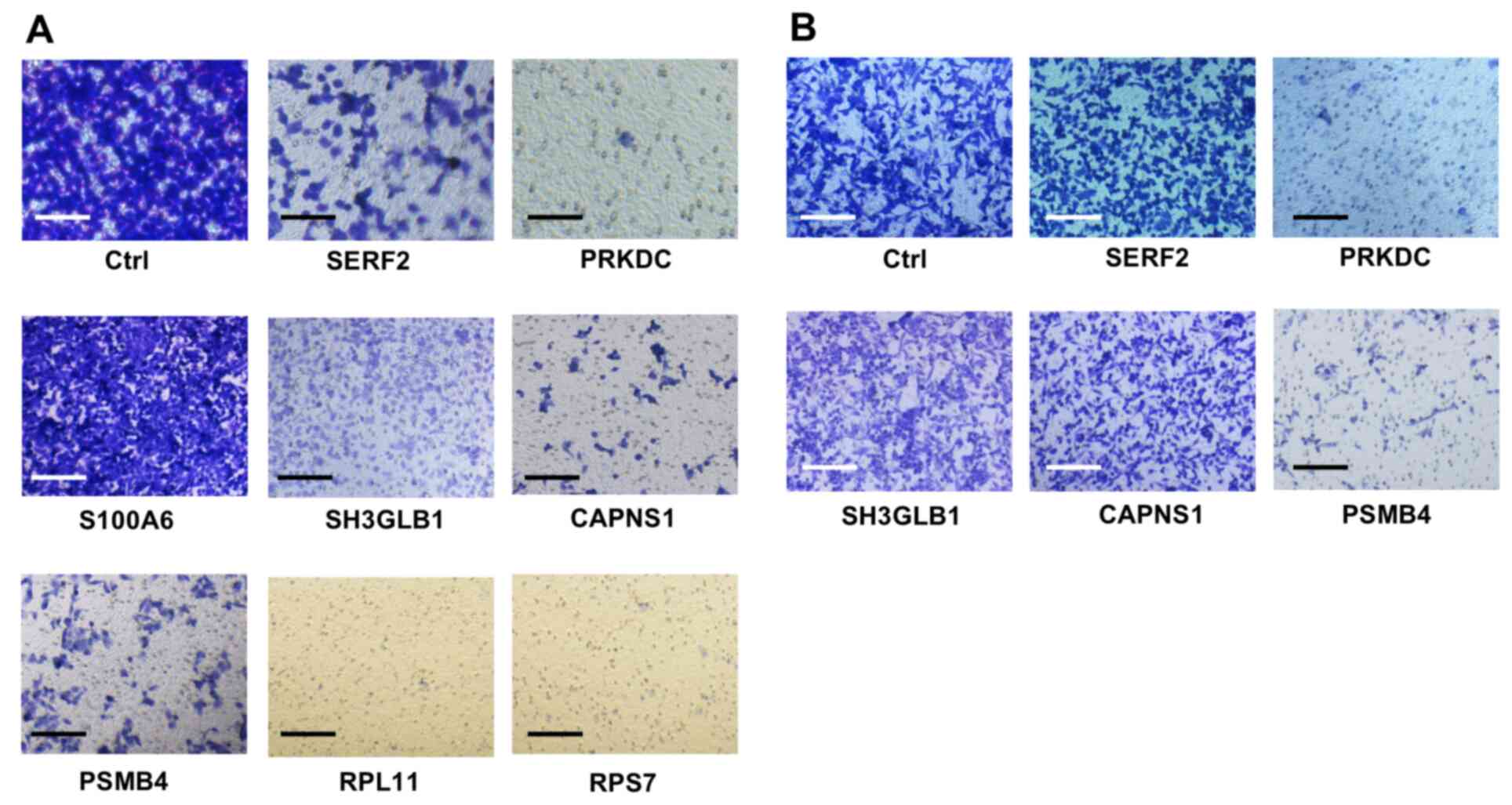

| Figure 1.Migration assays were performed using

the Boyden chamber method. After transfection of each siRNA into

the (A) A549 and (B) MDA231 cells, the cells were incubated for 48

h before the migration assay. The cells that had migrated to the

outer side of the membranes within 24 h were fixed and stained. A

representative image of a triplicate analysis of each siRNA is

shown. Scale bar, 20 µm. siRNA, small interfering RNA; Ctrl,

control siRNA; SERF2, small EDRK-rich factor 2; PRKDC,

DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit; S100A6, S100

calcium-binding protein A6; SH3GLB1, SH3-domain GRB2-like

endophilin B1; CAPNS1, calpain, small subunit 1; PSMB4, proteasome

subunit β type-4; RPL11, ribosomal protein L11; RPS7, ribosomal

protein S7. |

Our previous study identified six genes encoding

ribosomal proteins (RPLP2, RPL18A, RPL36, RPS10, RPS7 and RPL11) as

CUP-associated (−upregulated) genes (8). siRNAs against four of these ribosomal

protein genes (RPLP2, RPL18A, RPL36 and RPS10) almost completely

impaired the viability of A549 cells, and it was not possible to

perform the expression assay and migration assay using siRNAs of

these genes (Table I). The other

two siRNAs (targeting RPS7 and RPL11) abolished the viability of

MDA231 cells (Table I), indicating

that reduced expression of any single ribosomal protein molecule

could be critical for cell survival.

The present study subsequently focused on the siRNAs

against the five genes (SERF2, PRKDC, SH3GLB1, CAPNS1 and PSMB4)

based on their ability to reduce migration to less than half of

that of the control without affecting the cell viability (>50%

of the control; Table I). The

present study further analyzed their influence on the migration of

another cell line (MDA231). Only siRNAs specific for PRKDC and

PSMB4 markedly reduced the migration of the cells (Fig. 1B; Table

I). These siRNAs did not affect the viability of MDA231 cells,

resulting in a cell viability rate of 75.2% for PRKDC-specific

siRNA and >90% for PSMB4-specific siRNA. Furthermore, a marked

reduction in the expression of the respective genes was observed.

The siRNAs targeting PRKDC and PSMB4 reduced the expression levels

of the corresponding genes (0.107- and 0.033-fold changes,

respectively), which was similar to the trends observed for A549

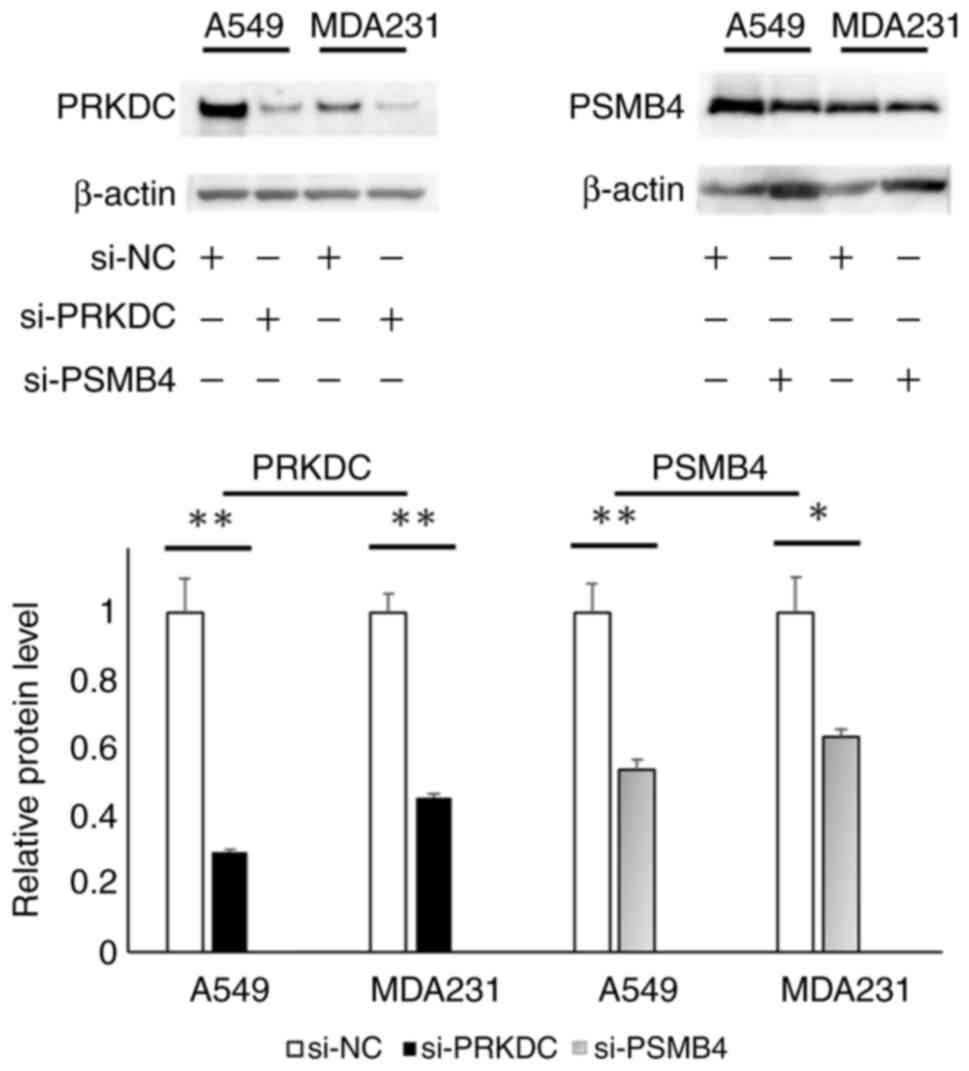

cells (Table I). Western blotting

confirmed that the expression of PRKDC and PSMB4 was reduced by the

siRNA-induced mRNA knockdown (Fig.

2).

Effect of downregulation of the

candidate genes on LN metastasis

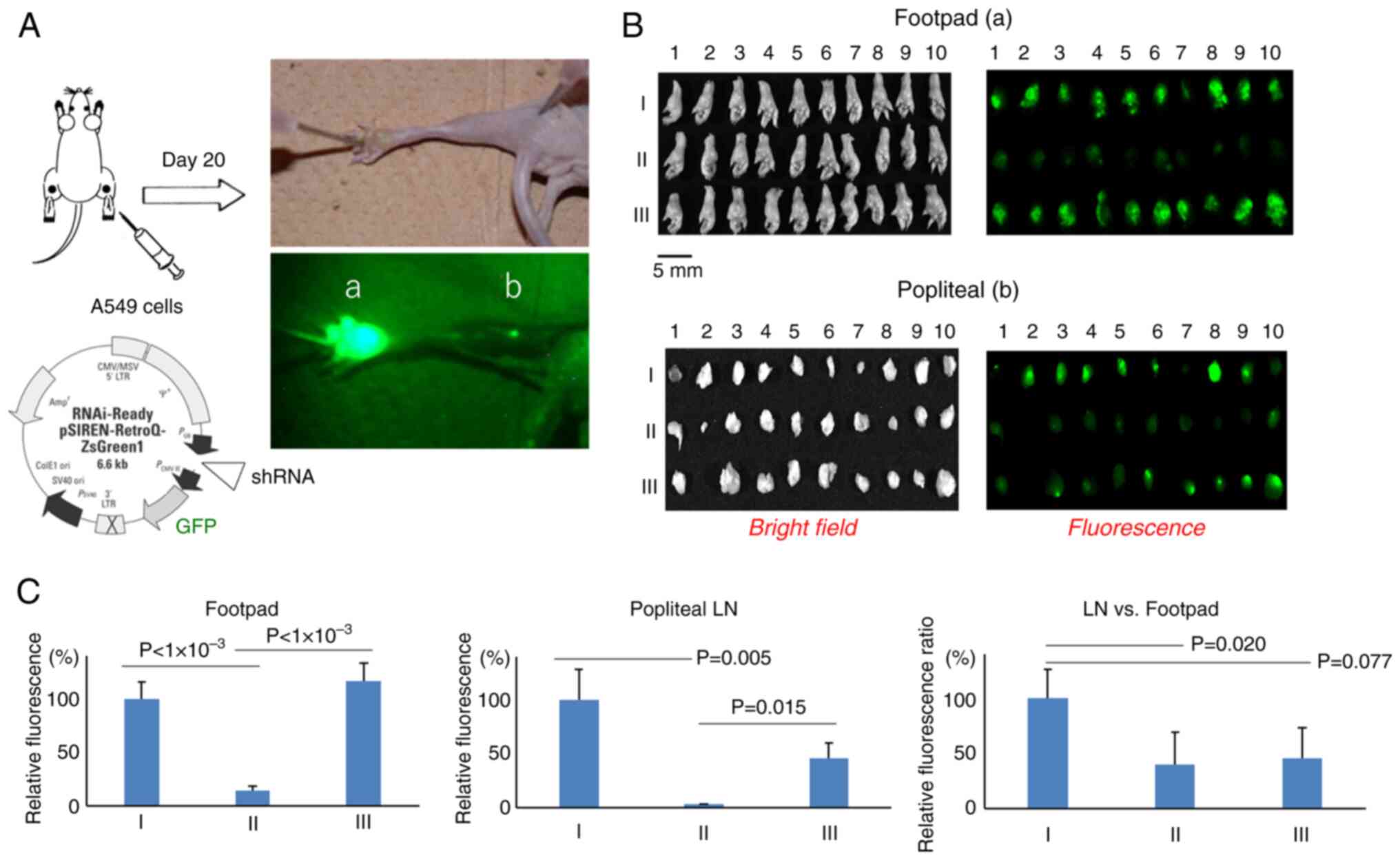

To determine whether downregulation of the two

genes, PRKDC and PSMB4, might affect the potential of the cells to

metastasize to the LNs in vivo, cell lines that stably

expressed both GFP and shRNA targeting the respective genes were

engineered. A control cell line transfected with a control vector

that expressed GFP alone was also established. The stable cell

lines for these constructs were isolated by FACS using GFP as a

reporter (Fig. S2A-C) and they

showed stable shRNA-based knockdown of PRKDC and PSMB4 during the

passage culture for ≥3 months. Western blotting confirmed that the

PRKDC and PSMB4 proteins expressed in A549 cells were reduced for

the respective constructs compared with the control vector

(Fig. S3A). The growth rate

remained unaltered in the A549 cells transfected with shRNA

targeting PSMB4 (>90% of the rate in the control cells), but the

cells transfected with shRNA targeting PRKDC exhibited an ~25%

reduction in the growth rate relative to that in the control cells

at 72 h (Fig. S3B). To evaluate

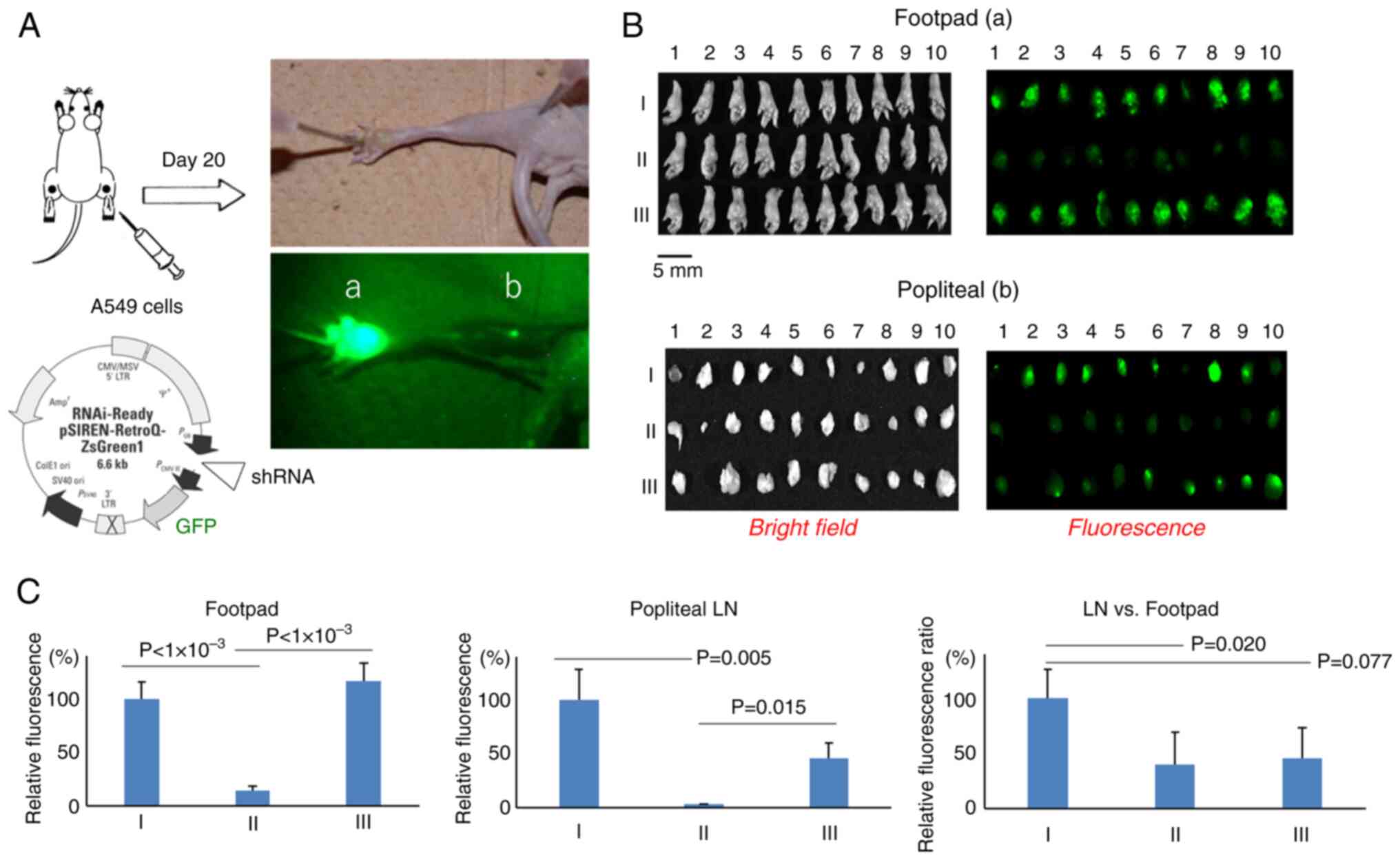

the metastasis-promoting potential of these two genes, cells

(1×106) containing the respective shRNA constructs were

subcutaneously injected into the footpads of BALB/c nude mice. On

day 20, the fluorescence intensities of GFP expressed in the

footpad and popliteal LNs were measured (Fig. 3A). The fluorescence intensities were

lower after injection of cells expressing PRKDC-shRNA than after

injection of cells transfected with a control vector (~14.8%),

whereas fluorescence intensities following injection of the cells

expressing PSMB4-shRNA were comparable to those following injection

of cells containing the control vector (Fig. 3B and C). A proportionate reduction

in fluorescence intensities was also observed in the popliteal LNs

in both the PRKDC-shRNA and PSMB4-shRNA groups, with popliteal

LN/footpad fluorescence intensity ratios of 39.4 and 45.5%,

respectively, compared with the control group (Fig. 3C). It was attempted to perform a

similar assay using MDA231-shRNA constructs; however, this cell

line failed to become engrafted into the footpads of the mice (data

not shown).

| Figure 3.Quantification of cells migrating

from the footpad to the popliteal LNs. (A) On day 20 after

inoculation of the cells into the footpad, the mice were sacrificed

and fixed, and the fluorescence in the (a) footpad and (b) LNs was

visualized and quantified. (B) Bright-field images (left) and

fluorescence images (right) of the resected footpad (top) and LNs

(bottom) are shown for: I, A549 cells harboring a control vector;

II, A549 cells expressing PRKDC shRNA; and III, A549 cells

expressing PSMB4 shRNA. Scale bar, 5 mm. (C) Relative fluorescence

levels of control vector (I), PRKDC shRNA (II) and PSMB4 shRNA

(III) in the footpad (left) and LN (middle), and the LN/footpad

fluorescence ratio (right). Data are presented as the mean ±

standard error of the mean. LN, lymph node; PRKDC, DNA-dependent

protein kinase catalytic subunit; PSMB4, proteasome subunit β

type-4; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; GFP, green fluorescent

protein. |

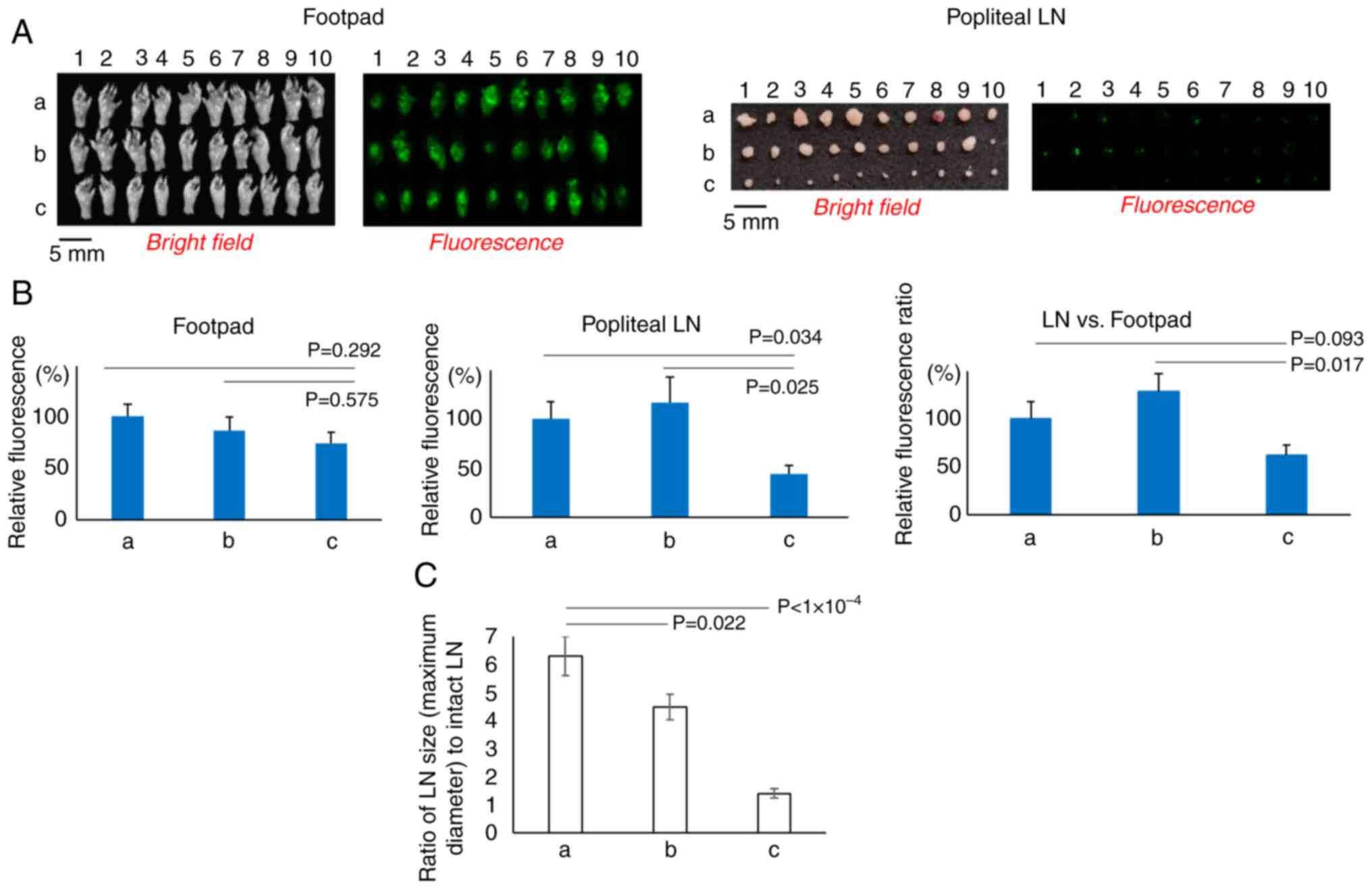

The present study subsequently examined whether

known inhibitors of PRKDC (DNA-PK) or PSMB4 (proteasome) could

alter the migration of cells. The inhibitors were injected

intravenously into the tails of mice that had been inoculated with

A549 cells harboring a control vector expressing GFP. NU7441, a

DNA-PK inhibitor, did not significantly change the fluorescence

intensity in either the footpads or popliteal LNs (Fig. 4A and B). By contrast, bortezomib, a

proteasome inhibitor, markedly retarded the migration of the cells

to the popliteal LNs, although the cell growth rate in the footpads

was comparable to that in the control animals, resulting in a lower

popliteal/footpad fluorescence intensity ratio compared with that

in the control group (P=0.093) and in the animals injected with

NU7441 (P=0.017) (Fig. 4B).

A marked difference in the size of the metastatic

LNs was observed between the groups that were and were not treated

with bortezomib (Fig. 4C). Compared

with the control group (vehicle), the bortezomib-treated group

showed significantly smaller (undeveloped) tumors at the metastatic

sites (LNs; P<10−4). The mean LN maximum diameters in

the group treated with vehicle and in the group treated with NU7447

(DNA-PK inhibitor) were 6.3- and 4.5-fold greater than the diameter

of intact LNs, whereas they were only 1.4-fold greater in the group

treated with bortezomib.

Discussion

Our previous study analyzed tumor mRNA samples from

60 patients with CUP using microarray analysis and constructed a

normalized gene expression profile specific to CUPs, which

identified a number of genes that were upregulated in the CUP

(8).

In the present study, to further narrow down the

genes closely related to the development of CUP among these

candidate genes, cell-based siRNA screening was performed in

vitro. A549 and MDA231 cells were selected for the screening

because they are among the most widely used cell lines as models

for research on the metastasis of lung cancer and breast cancer,

respectively (30,31). Furthermore, our previous study

demonstrated that the gene expression profile of CUP closely

resembled that of lung adenocarcinoma (8).

Individual knockdown of several candidate genes in

A549 or MDA231 cells using specific siRNAs resulted in restricted

migration of the cells. siRNAs against PRKDC and PSMB4 restricted

the migration in both cell lines, suggesting that these genes might

be involved in the metastatic ability of CUP. Furthermore, shRNAs

for PRKDC and PSMB4 also suppressed the migration of A549 cells

in vivo, with significance observed for shRNA for PRKDC,

whereas knockdown of PRKDC tended to slow the growth of the cells

as well. The PRKDC gene encodes DNA-PKcs, a large subunit (~469

KDa) of DNA-PK, which is an abundantly expressed kinase in higher

eukaryotes (32). As a DNA damage

repair protein, it drives several pathways that promote metastasis

and tumor growth (33,34). In melanoma cells, DNA-PKcs may

control the secretion of numerous proteins involved in metastasis,

such as matrix metalloproteinases, thereby regulating the tumor

microenvironment (35). A similar

regulation in favor of metastasis could occur in CUPs exhibiting

upregulation of DNA-PKcs (8).

PSMB4 encodes the β7 subunit of proteasome 20S. The

20S proteasome is the catalytic core of the proteasome complex with

a concentric circular structure, including two α rings and two β

rings, each ring consisting of 7 subunits, α1-7 and β1-7,

respectively (36). Proteasomes

affect tumor development by regulating tumor signaling pathways,

including NF-κB signaling. They recognize and degrade ubiquitinated

IκB, an inhibitor of NF-κB, thereby activating NF-κB signaling

(37). Proteasomes are also

required to maintain homeostasis in proliferating tumor cells by

eliminating the accumulation of misfolded proteins (38). In multiple myeloma (MM), plasma

cells secrete several immunoglobulins, which are macromolecules

that are synthesized and folded in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

(36). Therefore, proteasome

inhibitors that are widely used in the treatment of MM can block

the degradation of IκB and trigger the accumulation of misfolded

proteins, inhibiting NF-κB activity and inducing ER stress,

respectively, ultimately leading to cell death of the MM cells

(39,40). Furthermore, DNA-PKcs is an

additional target that is cleaved and inactivated by proteasome

inhibitors in MM cells (40,41).

In the present study, bortezomib, the first

proteasome inhibitor developed as a chemotherapy drug (29), markedly restricted the metastatic

ability of A549 cells in vivo. The target of this drug has

been identified as the β5 subunit of proteasome 20S (39). Subunits other than the β7 subunit

(encoded by PSMB4) include the β5 subunit, which was also

upregulated in both CUPs (GSE42392) (8) and A549 cells compared with small

airway epithelial cells (GSE4824) (42) (Table

SIII). The trend was also noted in other tumors located in the

liver or head and neck regions (Table

SIII), with each of these tumors identified as a potential

treatment target for bortezomib (36,37).

The development of immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs) has markedly changed the treatment paradigms for numerous

cancer types. Among patients with CUP, 28% exhibit one or more

predictive biomarkers for ICIs. For example, programmed

death-ligand 1 is expressed on ≥5% tumor cells in 22.5% or on

lymphocytes in 58.7% of such patients. Microsatellite

instability-high is observed in 1.8% and tumor mutational burden

(TMB) ≥17 mutations per megabase of the tumor genome is present in

11.8% of these patients (43).

Although these biomarkers have not yet been

validated in patients with CUP, those with CUP with TMB >10

mutations per megabase generally experience improved outcomes when

treated with ICIs (43), and our

previous study recently demonstrated the clinical benefits of

nivolumab in patients with CUP (44). The present study demonstrated a

putative role for the proteasome in the progression of CUP that

could be prevented by proteasome-targeted therapy. Proteasome

inhibitors combined with ICIs may be an additional therapeutic

option for CUP, for which there are limited treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Tomoko Kitayama

(Department of Genome Biology, Kindai University Faculty of

Medicine, Osaka-Sayama, Japan) and Mr. Kentaro Egawa (Center for

Animal Experiment, Kindai University Faculty of Medicine,

Osaka-Sayama, Japan) for help with the animal experiments.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (C) (grant no. 17K07204) of Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and by

the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant no.

201438137A).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YF designed the study and drafted the manuscript. YF

and MADV performed the experiments and collected data. YF, MADV,

HH, KNa and KNi analyzed and interpreted the data, and revised the

manuscript. YF and MADV confirmed the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Animal Care Committee of the Kindai University Faculty of Medicine

(approval no. KDMS-25-019; Osaka-Sayama, Japan) and carried out in

compliance with the standards for the use of laboratory

animals.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CUP

|

cancer of unknown primary

|

|

PRKDC

|

protein kinase DNA-activated catalytic

subunit

|

|

PSMB4

|

proteasome subunit β type-4

|

References

|

1

|

Pavlidis N and Pentheroudakis G: Cancer of

unknown primary site. Lancet. 379:1428–1435. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rassy E, Parent P, Lefort F, Boussios S,

Baciarello G and Pavlidis N: New rising entities in cancer of

unknown primary: Is there a real therapeutic benefit? Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 147:1028822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Greco FA and Pavlidis N: Treatment for

patients with unknown primary carcinoma and unfavorable prognostic

factors. Semin Oncol. 36:65–74. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pavlidis N, Khaled H and Gaafar R: A mini

review on cancer of unknown primary site: A clinical puzzle for the

oncologists. J Adv Res. 6:375–382. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fizazi K, Greco FA, Pavlidis N, Daugaard

G, Oien K and Pentheroudakis G; ESMO Guidelines Committee, :

Cancers of unknown primary site: ESMO clinical practice guidelines

for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 26 (Suppl

5):v133–v138. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hayashi H, Kurata T, Takiguchi Y, Arai M,

Takeda K, Akiyoshi K, Matsumoto K, Onoe T, Mukai H, Matsubara N, et

al: Randomized phase II trial comparing site-specific treatment

based on gene expression profiling with carboplatin and paclitaxel

for patients with cancer of unknown primary site. J Clin Oncol.

37:570–579. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Rassy E, Labaki C, Chebel R, Boussios S,

Smith-Gagen J, Greco FA and Pavlidis N: Systematic review of the

CUP trials characteristics and perspectives for next-generation

studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 107:1024072022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kurahashi I, Fujita Y, Arao T, Kurata T,

Koh Y, Sakai K, Matsumoto K, Tanioka M, Takeda K, Takiguchi Y, et

al: A microarray-based gene expression analysis to identify

diagnostic biomarkers for unknown primary cancer. PLoS One.

8:e632492013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Arao T, Fukumoto H, Takeda M, Tamura T,

Saijo N and Nishio K: Small in-frame deletion in the epidermal

growth factor receptor as a target for ZD6474. Cancer Res.

64:9101–9104. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tanaka K, Arao T, Maegawa M, Matsumoto K,

Kaneda H, Kudo K, Fujita Y, Yokote H, Yanagihara K, Yamada Y, et

al: SRPX2 is overexpressed in gastric cancer and promotes cellular

migration and adhesion. Int J Cancer. 124:1072–1080. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Clough E and Barrett T: The gene

expression omnibus database. Methods Mol Biol. 1418:93–110. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lenburg ME, Liou LS, Gerry NP, Frampton

GM, Cohen HT and Christman MF: Previously unidentified changes in

renal cell carcinoma gene expression identified by parametric

analysis of microarray data. BMC Cancer. 3:312003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pawitan Y, Bjöhle J, Amler L, Borg AL,

Egyhazi S, Hall P, Han X, Holmberg L, Huang F, Klaar S, et al: Gene

expression profiling spares early breast cancer patients from

adjuvant therapy: Derived and validated in two population-based

cohorts. Breast Cancer Res. 7:R953–R964. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

International Genetics Consortium, .

Expression project for oncology (expO). Gene Expression Omnibus,

GSE2109. 2005.Available from:. http://www.intgen.org/

|

|

16

|

Luesch H, Chanda SK, Raya RM, DeJesus PD,

Orth AP, Walker JR, Belmonte JCI and Schultz PG: A functional

genomics approach to the mode of action of apratoxin A. Nat Chem

Biol. 2:158–167. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bild AH, Yao G, Chang JT, Wang Q, Potti A,

Chasse D, Joshi NR, Harpole D, Lancaster JM, Berchuck A, et al:

Oncogenic pathway signatures in human cancers as a guide to

targeted therapies. Nature. 439:353–357. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dyrskjøt L, Kruhøffer M, Thykjaer T,

Marcussen N, Jensen JL, Møller K and Ørntoft TF: Gene expression in

the urinary bladder: A common carcinoma in situ gene expression

signature exists disregarding histopathological classification.

Cancer Res. 64:4040–4048. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gemma A, Li C, Sugiyama Y, Matsuda K,

Seike Y, Kosaihira S, Minegishi Y, Noro R, Nara M, Seike M, et al:

Anticancer drug clustering in lung cancer based on gene expression

profiles and sensitivity database. BMC Cancer. 6:1742006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rinaldi A, Kwee I, Taborelli M, Largo C,

Uccella S, Martin V, Poretti G, Gaidano G, Calabrese G, Martinelli

G, et al: Genomic and expression profiling identifies the B-cell

associated tyrosine kinase Syk as a possible therapeutic target in

mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 132:303–316. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bachtiary B, Boutros PC, Pintilie M, Shi

W, Bastianutto C, Li JH, Schwock J, Zhang W, Penn LZ, Jurisica I,

et al: Gene expression profiling in cervical cancer: An exploration

of intratumor heterogeneity. Clin Cancer Res. 12:5632–5640. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pyeon D, Newton MA, Lambert PF, den Boon

JA, Sengupta S, Marsit CJ, Woodworth CD, Connor JP, Haugen TH,

Smith EM, et al: Fundamental differences in cell cycle deregulation

in human papillomavirus-positive and human papillomavirus-negative

head/neck and cervical cancers. Cancer Res. 67:4605–4619. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang Y, Xia XQ, Jia Z, Sawyers A, Yao H,

Wang-Rodriquez J, Mercola D and McClelland M: In silico estimates

of tissue components in surgical samples based on expression

profiling data. Cancer Res. 70:6448–6455. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kaneda H, Arao T, Tanaka K, Tamura D,

Aomatsu K, Kudo K, Sakai K, De Velasco MA, Matsumoto K, Fujita Y,

et al: FOXQ1 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer and enhances

tumorigenicity and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 70:2053–2063. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Picot J, Guerin CL, Le Van Kim C and

Boulanger CM: Flow cytometry: Retrospective, fundamentals and

recent instrumentation. Cytotechnology. 64:109–130. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen Z, Zhuo W, Wang Y, Ao X and An J:

Down-regulation of layilin, a novel hyaluronan receptor, via RNA

interference, inhibits invasion and lymphatic metastasis of human

lung A549 cells. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 50:89–96. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kura Y, De Velasco MA, Sakai K, Uemura H,

Fujita K and Nishio K: Exploring the relationship between

ulcerative colitis, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer. Hum

Cell. 37:1706–1718. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhao Y, Thomas HD, Batey A, Cowell IG,

Richardson CJ, Griffin RJ, Calvert AH, Newell DR, Smith GCM and

Curtin NJ: Preclinical evaluation of a potent novel DNA-dependent

protein kinase inhibitor NU7441. Cancer Res. 66:5354–5362. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen D, Frezza M, Schmitt S, Kanwar J and

Dou QP: Bortezomib as the first proteasome inhibitor anticancer

drug: Current status and future perspectives. Curr Cancer Drug

Targets. 11:239–253. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lengrand J, Pastushenko I, Vanuytven S,

Song Y, Venet D, Sarate RM, Bellina M, Moers V, Boinet A, Sifrim A,

et al: Pharmacological targeting netrin-1 inhibits EMT in cancer.

Nature. 620:402–408. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Liu K, Newbury PA, Glicksberg BS, Zeng

WZD, Paithankar S, Andrechek ER and Chen B: Evaluating cell lines

as models for metastatic breast cancer through integrative analysis

of genomic data. Nat Commun. 10:21382019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Dylgjeri E and Knudsen KE: DNA-PKcs: A

targetable protumorigenic protein kinase. Cancer Res. 82:523–533.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Xiang Z, Hou G, Zheng S, Lu M, Li T, Lin

Q, Liu H, Wang X, Guan T, Wei Y, et al: ER-associated degradation

ligase HRD1 links ER stress to DNA damage repair by modulating the

activity of DNA-PKcs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 121:e24030381212024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Caron P, Pankotai T, Wiegant WW,

Tollenaere MAX, Furst A, Bonhomme C, Helfricht A, de Groot A,

Pastink A, Vertegaal ACO, et al: WWP2 ubiquitylates RNA polymerase

II for DNA-PK-dependent transcription arrest and repair at DNA

breaks. Genes Dev. 33:684–704. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kotula E, Berthault N, Agrario C, Lienafa

MC, Simon A, Dingli F, Loew D, Sibut V, Saule S and Dutreix M:

DNA-PKcs plays role in cancer metastasis through regulation of

secreted proteins involved in migration and invasion. Cell Cycle.

14:1961–1972. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhou X, Xu R, Wu Y, Zhou L and Xiang T:

The role of proteasomes in tumorigenesis. Genes Dis. 11:1010702023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Narayanan S, Cai CY, Assaraf YG, Guo HQ,

Cui Q, Wei L, Huang JJ, Ashby CR Jr and Chen ZS: Targeting the

ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to overcome anti-cancer drug

resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 48:1006632020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chhabra S: Novel proteasome inhibitors and

histone deacetylase inhibitors: Progress in myeloma therapeutics.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 10:402017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Gandolfi S, Laubach JP, Hideshima T,

Chauhan D, Anderson KC and Richardson PG: The proteasome and

proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

36:561–584. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hideshima T and Anderson KC: Biologic

impact of proteasome inhibition in multiple myeloma cells-from the

aspects of preclinical studies. Semin Hematol. 49:223–227. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wu YH, Hong CW, Wang YC, Huang WJ, Yeh YL,

Wang BJ, Wang YJ and Chiu HW: A novel histone deacetylase inhibitor

TMU-35435 enhances etoposide cytotoxicity through the proteasomal

degradation of DNA-PKcs in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer

Lett. 400:79–88. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Byers LA, Diao L, Wang J, Saintigny P,

Girard L, Peyton M, Shen L, Fan Y, Giri U, Tumula PK, et al: An

epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene signature predicts

resistance to EGFR and PI3K inhibitors and identifies Axl as a

therapeutic target for overcoming EGFR inhibitor resistance. Clin

Cancer Res. 19:279–290. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Rassy E, Boussios S and Pavlidis N:

Genomic correlates of response and resistance to immune checkpoint

inhibitors in carcinomas of unknown primary. Eur J Clin Invest.

51:e135832021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Tanizaki J, Yonemori K, Akiyoshi K, Minami

H, Ueda H, Takiguchi Y, Miura Y, Segawa Y, Takahashi S, Iwamoto Y,

et al: Open-label phase II study of the efficacy of nivolumab for

cancer of unknown primary. Ann Oncol. 33:216–226. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|