Introduction

Lysosomes, often referred to as the digestive units

of the cells, are membrane-bound organelles essential for recycling

damaged intracellular components and organelles. In addition to

their degradative functions, lysosomes play key roles in multiple

physiological and pathological processes (1), including nutrient sensing, metabolic

regulation and aging. They have emerged as critical mediators of

drug resistance, particularly in cancer treatment with tyrosine

kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (2,3). The

acidic environment within lysosomes, coupled with the cytosolic pH

gradient, facilitates the passive uptake of hydrophobic, weakly

basic drugs such as TKIs. This pH-dependent sequestration reduces

TKI efficacy by trapping within lysosomes (4–6).

Cancer cells with increased drug sequestration have been shown to

exhibit heightened resistance to therapy, suggesting that lysosomal

trapping is a major therapeutic barrier to treatment success

(3,6). However, the mechanisms by which cells

tolerate high TKI concentrations within lysosomes remain poorly

understood.

Lysosomes are as crucial intracellular

Ca2+ stores, releasing Ca2+ to regulate

signaling pathways essential for organelle homeostasis and

acidification (7). Ca2+

channels, including transient receptor potential mucolipins

(TRPMLs) and two-pore channels located on the endolysosomal

membrane, are essential for proliferation, migration and calcium

homeostasis, all of which are significant both normal physiology

and disease (8). The TRPML family,

also known as mucolipins, consists of three isoforms, TRPML1, −2

and −3, each functioning as inward-rectifying cation channels with

physiological and pathological roles (9). TRPML1, the first identified isoform,

has been linked to type IV mucolipidosis (MLIV), a disorder caused

by loss-of-function mutations (10). It is activated by

phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate, voltage changes and low

luminal pH (11). As a

non-selective cation channel, it facilitates lysosomal degradation.

Its deficiency leads to excessively acidic lysosomes due to

impaired H+ efflux (12). Fibroblasts from patients with MLIV

exhibit defective lysosomal degradation of macromolecules (13). TRPML1 regulates autophagy by

releasing Ca2+, which is necessary for mTORC1 modulation

and autophagosome-lysosome fusion (14). Finally, it promotes lysosomal

biogenesis by releasing Ca2+, which triggers

transcription factor EB (TFEB) dephosphorylation and nuclear

translocation (15).

TRPML3 also plays a key role in endocytic and

autophagic pathways (16). As a

phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate effector, it facilitates

Ca2+ release into the cytoplasm, a process essential for

membrane fusion and autophagosome formation (17). Despite their functional overlap,

TRPML1 and TRPML3 differ in pH sensitivity: The latter is fully

active at a higher pH (~6.3), whereas the former operates optimally

at a lower pH (~4-5.5) (18).

Neutralizing lysosomal pH with uropathogenic E. coli has

been shown to activate TRPML3, triggering Ca2+ release

and lysosomal exocytosis (19).

Reduced luminal Ca2+ in early endosomes has been linked

to increased acidification (20),

while Ca2+ release through TRPML3 supports H+

uptake via the vacuolar H+ pump, helping maintain

lysosomal acidity (21). These

findings suggest the hypothesis that TRPML3 enhances lysosomal TKI

sequestration, contributing to acquired drug resistance. This

hypothesis warrants further investigation.

In the present study, TRPML3 expression in non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissues during the development of drug

resistance was initially determined. Using two- and

three-dimensional (2D and 3D, respectively) cell-culture models,

TRPML3 function in the regulation of lysosomal pH, biogenesis and

drug resistance was investigated. It was found that TRPML3 enhances

lysosomal sequestration of osimertinib and compensates for TRPML1

in lysosomal biogenesis during treatment, significantly

contributing to drug resistance.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, reagents and

transfection

Human PC9 and HCC827 NSCLC cell lines were

generously provided by Dr Jin Kyung Rho (Asan Medical Center, Ulsan

University). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (HyClone;

Cytiva) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and

antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin) in a

humidified incubator with 5% CO2. All cell lines used in

the present study were authenticated by short tandem repeat

profiling (KOMA Biotech, Inc.) and were routinely screened for

microbial contamination as part of standard quality control

procedures. The TRPML3-GCaMP6 construct, generated by inserting the

full-length GCaMP6 sequence into the p3XFLAG-CMV-7.1-TRPML3 vector

(17), was kindly provided by Dr

Hyun Jin Kim (Sungkyunkwan University). The pCMV-TRPML3 expression

vector containing wild-type TRPML3 (NM_018298) was obtained from

OriGene Technologies, Inc. Reagents and their sources were as

follows: osimertinib (Selleck Chemicals), Cell Fractionation Kit

(Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-TFEB (cat. no. 4240s),

anti-Nanog (cat. no. 3580s; both from Cell Signalling Technology,

Inc.), TRPML agonist ML-SA1 (MilliporeSigma; cat. no. SML0627),

TRPML inhibitor ML-SI1 (GlpBio; cat. no. GC19764), anti-Myc (cat.

no. sc-40; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-CD44 (cat. no.

MA5-13890; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), anti-CD133 (cat. no.

ab16048), anti-lamin-B1 (cat. no. ab19898; both from Abcam),

anti-TRPML1 (cat. no. MBS9205163; MyBioSource, Inc.), anti-TRPML3

(cat. no. 13879-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and anti-GAPDH (cat.

no. bs2188R; BIOSS). For transient gene silencing, synthetic small

interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting TRPML3 and scrambled

control siRNAs were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies,

Inc. Their sequences were as follows: TRPML3 siRNA sense,

5′-GUAGAAUUUACCUCUACUCAUUCAT-3′ and antisense,

3′-AUCAUCUUAAAUGGAGAUGAGUAAGUA-5′; scrambled siRNA sense,

5′-CGUUAAUCGCGUAUAAUACGCUAT-3′ and antisense,

3′-AUACGCGUAUUAUACGCGAUUAACGAC-5′. The siRNAs and expression

vectors were introduced using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX and

Lipofectamine 3000, respectively, according to the manufacturer's

protocols (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). In brief, each mixture

of siRNA (30 nM per 35-mm dish) with RNAiMAX and expression vectors

(2.5 µg per 35-mm dish) with Lipofectamine 3000 was incubated for 5

min and 15 min, respectively, at 24°C. Each sample was then

subjected to subsequent experiment following an additional

incubation of 72 and 24 h, respectively. To generate a stable

TRPML3 knockout cell line, an sgRNA targeting TRPML3 (RefSeq

NM_018298.11) was designed and synthesized by Macrogen, Inc.

(5′-CAGCTACTCACAACTACCTCAGG-3′). It was inserted into the

pSp-U6-Cas9-2A-Puro plasmid; cells were transfected with either the

TRPML3-specific construct or the empty vector control. After

puromycin selection (2–10 µg/ml) for two weeks, the TRPML3 knockout

was confirmed using western blotting.

Osimertinib-resistant NSCLC sub-cell

lines

Resistant sub-lines of PC9 and HCC827, designated as

PC9/OR and HCC827/OR, respectively, were generated by gradually

increasing osimertinib concentrations (1×10−4,

1×10−3, 1×10−2, and 1×10−1 µM)

over five months. Surviving cells were cultured in

1×10−1 µM osimertinib for an additional month to confirm

the stability of resistance. Viability at each subculture step was

assessed using 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl

tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays.

Collection and analysis of publicly

available RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data

To measure gene expression changes in lung

adenocarcinoma (LUAD) tissues during the development of osimertinib

resistance, a publicly available RNA-seq dataset (GSE253742) from

the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was analyzed,

representing paired LUAD tumor samples collected before and after

osimertinib treatment (22). Data

were processed using Expression Differential Expression Gene

Analysis (ExDEGA v5.1.1.1) software (Ebiogen Inc.). Briefly, raw

data were subjected to quality control with FastQC, followed by

adapter trimming and low-quality read removal using Fastp (23). Processed reads were aligned to the

reference genome with STAR (24),

and quantified using Salmon (25).

Read count normalization was performed using the TMM + CPM method

in EdgeR (26). Data mining and

visualization were performed using ExDEGA and Multi Experiment

Viewer (MeV 4.9.0; http://www.tm4.org) (27).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cell lines using

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), following the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently, 1 µg of

RNA was converted into cDNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), following the

manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was conducted

using VeriQuest SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Affymetrix; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on an ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detection

System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at

95°C for 20 sec, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for

3 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec. Primers were as

follows: TRPML3 forward, 5′-TCCGTTGGGAATCATGCTTAT-3′ and

reverse, 5′-AGTGCTGACAGATTGCCATAGC-3′; GAPDH forward,

5′-ATGGAAATCCCATCACCATCTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGCCCCACTTGATTTTGG-3′.

GAPDH expression was used to normalize data and controls for

variations in mRNA concentration. Expression levels were calculated

using the 2−ΔΔCq method (28).

Generation of cancer cell line-derived

spheroid

To generate 3D spheroid cultures, cells were

resuspended in culture medium supplemented with threefold the

standard FBS concentration at a density of 6×104

cells/ml for PC9 and its subline and 4.2×104 cells/ml

for HCC827 and its subline. Cell suspensions were mixed with

VitroGel Hydrogel Matrix (Well Bioscience Inc.; http://www.thewellbio.com) at a 2:1 (v/v) ratio; the

50 µl of the mixture was added per well in U-bottom 96-well plates

(S-bio Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Ltd.). Plates were centrifuged at

1,000 × g for 5 min at 24°C, and 200 µl of regular culture medium

was added per well. Aggregates were incubated in the hydrogel

matrix at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for three days to

form multilayered spheroids. These spheroids were treated with

osimertinib or left untreated (DMSO vehicle only) for an additional

9 days, with medium refreshed every 3 days. Spheroids were imaged

using a NIKON Eclipse TS100 microscope equipped with an FL-20BW

CMOS camera (Tucsen Photonics Co., Ltd.). Images were captured with

Mosaic 2.4 software (Tucsen Photonics Co., Ltd.) and analyzed using

ImageJ software (version 1.51k; National Institutes of Health) to

measure spheroid diameters and other parameters. Viability was

measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay kit (Dojindo

Laboratories, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. In

brief, 20 µl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated

at 37°C for 1 h, after which the absorbance was measured at 450 nm

using an iMark microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed using established

methods (29). Cell lysates

prepared in RIPA buffer (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) were sonicated for 5 sec at 50% amplitude and incubated on

ice for 10 min. Debris was pelleted at 14,440 × g for 10 min at

4°C. Supernatant protein concentrations were quantified using the

BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein (20 µg per sample) were

separated using 8% SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to 0.2-µm

polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Cytiva). The membrane was

blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (GenDEPOT, LLC) in

Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 at 4°C for 2 h. Primary

antibodies against TRPML1, TRPML3, TFEB, lamin-B1, Myc, CD44,

CD133, Nanog and GAPDH were used at a 1:1,000 dilution. The

membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary

antibodies, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase

(HRP)-linked secondary IgG antibody (1:2,500; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.; cat. no. sc-516102 for anti-mouse, and cat.

no. sc-2357 for anti-rabbit) for 2 h at 4°C. Protein bands were

visualized and quantified using the AzureSpot 2.0 software (Azure

Biosystems, Inc.). Whole-cell lysate from spheroids cultured in

VitroGel Hydrogel Matrix (Well Bioscience, Inc.) were extracted

using VitroGel Organoid Recovery Solution (Well Bioscience, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, spheroids were

transferred to 1.5-ml tubes, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 1

ml of pre-warmed (37°C) VitroGel Organoid Recovery Solution. The

solution was gently pipetted to isolate the spheroids, followed by

a brief incubation at 37°C. After centrifugation at 100 × g for 5

min, pellets were collected and lysed in RIPA buffer. To measure

TFEB translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, cytosolic and

nuclear fractions were isolated using a Cell Fractionation Kit

(Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), following the manufacturer's

instructions. Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in Cytoplasm

Isolation Buffer and incubated at 4°C for 5 min. Suspensions were

centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and cytosolic supernatants

were collected. Nuclear pellets were resuspended in Membrane

Isolation Buffer, re-pelleted at 8,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and

resuspended in Cytoskeleton/Nuclear Isolation Buffer. Both

fractions were analyzed using western blotting.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded at a density of 7×105

per 60 mm culture dish. Following incubation under the designated

conditions, they were detached using 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and fixed in 70% ethanol at −20°C

for 2 h, then stained with 0.5 ml of propidium iodide/RNase

staining buffer (BD Biosciences) for 15 min. Flow cytometry was

performed on at least 20,000 cells using a FACScan analyzer (BD

CellQuestTM Pro version 5.2; BD Biosciences).

MTT assay

Cell viability was assessed using the Viability

Assay Kit (Cellrix; MediFab) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Cells were seeded at a density of 1×104 per well in

96-well plates, treated with 10 µl of assay reagent containing

water-soluble tetrazolium salt, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min.

The production of water-soluble formazan was evaluated by measuring

the absorbance at 450 nm using an iMark microplate reader (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

Imaging of intracellular

Ca2+ (Ca2+i) and green fluorescent

protein (GFP)

Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured

by incubation with Fura-2/AM (MilliporeSigma) at 37°C for 50 min,

followed by perfusion with a HEPES-buffered solution containing 140

mmol/l NaCl, 5 mmol/l KCl, 1 mmol/l MgCl2, 1 mmol/l

CaCl2, 10 mmol/l HEPES, and 10 mmol/l glucose, adjusted

to pH 7.4 and 310 mOsm. For Ca2+-free conditions, the

CaCl2 was replaced with 1 mmol/l EGTA. Osimertinib and

other compounds, including ML-SI1 and MS-SA1, were diluted in a

Ca2+-free HEPES buffer. Fluorescence excitation was

performed at 340 and 380 nm, with emission at 510 nm-captured using

an sCMOS camera (Andor Technology Ltd.). Ratio-metric data

(F340/F380) were analyzed using Meta-Fluor

Fluorescence Ratio Imaging software (Molecular Devices, LLC).

GCaMP6 fluorescence intensities were measured at an excitation

wavelength of 488 nm, with emission at 510 nm measured using an

sCMOS camera (Andor Technology Ltd.) and analyzed using Meta-Fluor

Fluorescence Ratio Imaging software (Molecular Devices, LLC).

Measurement of lysosomal pH

Lysosomal pH was measured using a LysoSensor

Yellow/Blue DND-160 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to

the manufacturer's protocol. Cells cultured in 35 mm confocal

dishes (SPL Life Sciences) were incubated with the dye for 10 min

at 37°C. After a brief wash with HEPES buffer, cells were

continuously exposed to osimertinib diluted in HEPES buffer.

Fluorescent images were captured using an sCMOS camera (Andor

Technology Ltd.) with excitation at 329 and 384 nm and emission at

440 and 540 nm, respectively. Data were analyzed using MetaMorph

software (Molecular Devices, LLC), and lysosomal pH was determined

by calculating the fluorescence intensity ratio of 384 nm (yellow,

acidic) to 329 nm (blue, less acidic), with fold changes expressed

relative to the control (scr-cells pre-osimertinib treatment).

Measurement of lysosomal area in a

single cell

The lysosomal area in individual cells was measured

using LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were plated in

35 mm confocal dishes and transfected with either siML3 or

scrambled RNA as a control. After 72 h, the cells were treated with

0.01 µM osimertinib, incubated for 24 h, and stained with

LysoTracker Red DND-99 for 30 min. Fluorescence was excited at 577

nm and emitted at 590 nm, and images were captured using a confocal

microscope (FV1000; Olympus Corporation). Image analysis was

performed using ImageJ software (version 1.52v; National Institutes

of Health).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Origin 2020 software

(OriginLab Corporation). Results are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD) based on a minimum of three independent

experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's post-hoc test for

multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

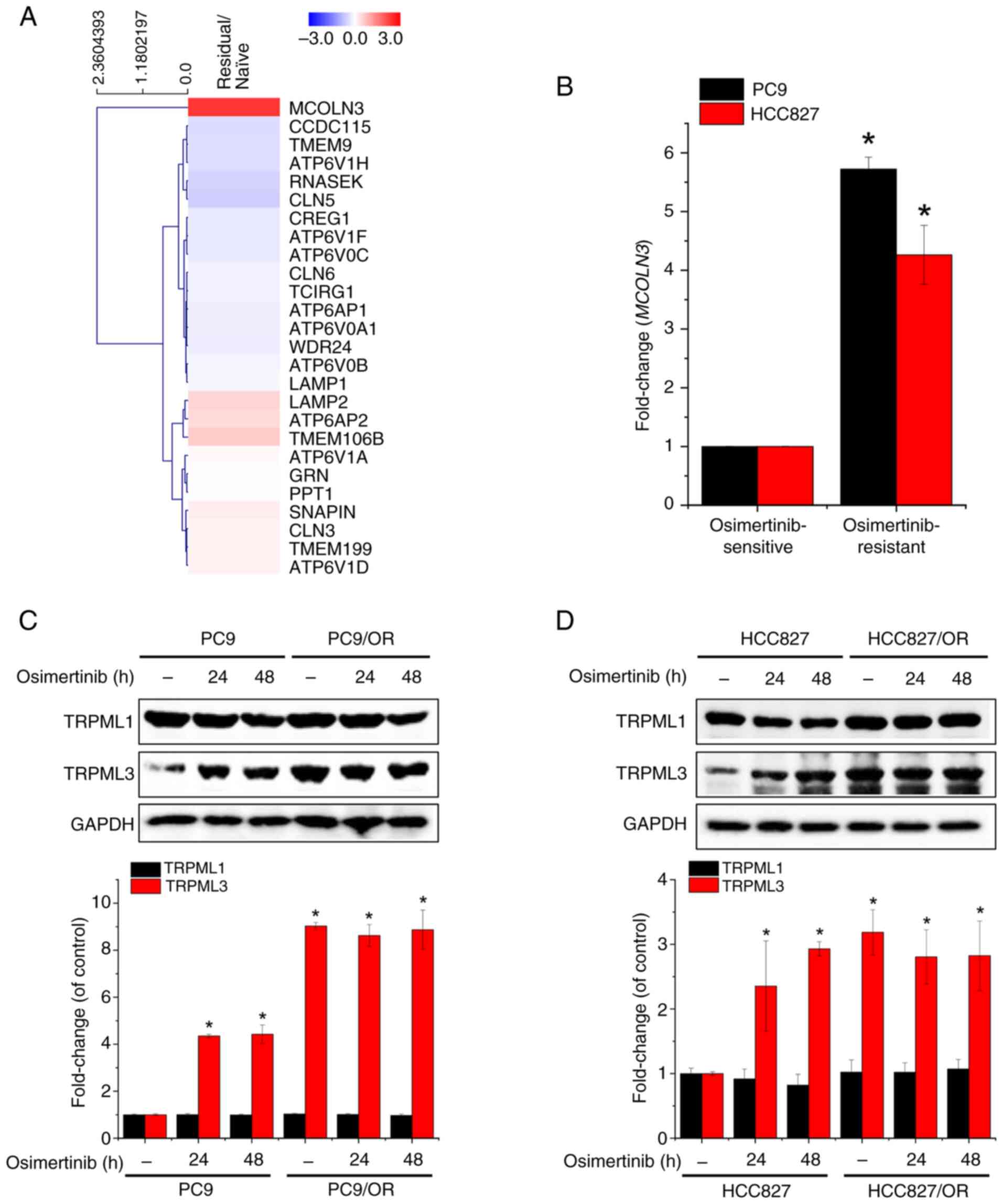

Endogenous TRPML3 expression is

upregulated in osimertinib-residual LUAD tumor tissues and

osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cell lines

To identify genes involved in osimertinib-induced

lysosomal pH dysregulation, the GEO dataset GSE253742 was analyzed,

which includes RNA-seq data from eight clinical LUAD specimens

(four naive tumors and four osimertinib-residual tumors). Of the

40,929 genes analyzed, TRPML3 was the only gene whose

expression was significantly increased (5.121±0.045; |fold

change|≥2, log2 ≤3, P<0.05) in osimertinib-residual tumors

within a subset of 26 genes related to lysosomal acidification

(GO:0007042) (Fig. 1A). Based on

these findings, the expression was next measured in NSCLC cell

lines, specifically PC9 and HCC827, and in their

osimertinib-resistant sublines. TRPML3 mRNA levels were

significantly higher in osimertinib-resistant cells than in their

parental lines (Fig. 1B).

Additionally, osimertinib exposure and resistance increased TRPML3

protein expression, whereas TRPML1 expression remained unchanged

regardless of treatment or resistance (Fig. 1C and D). These findings suggest that

TRPML3 plays a critical role in the lysosomal response associated

with osimertinib resistance in NSCLC.

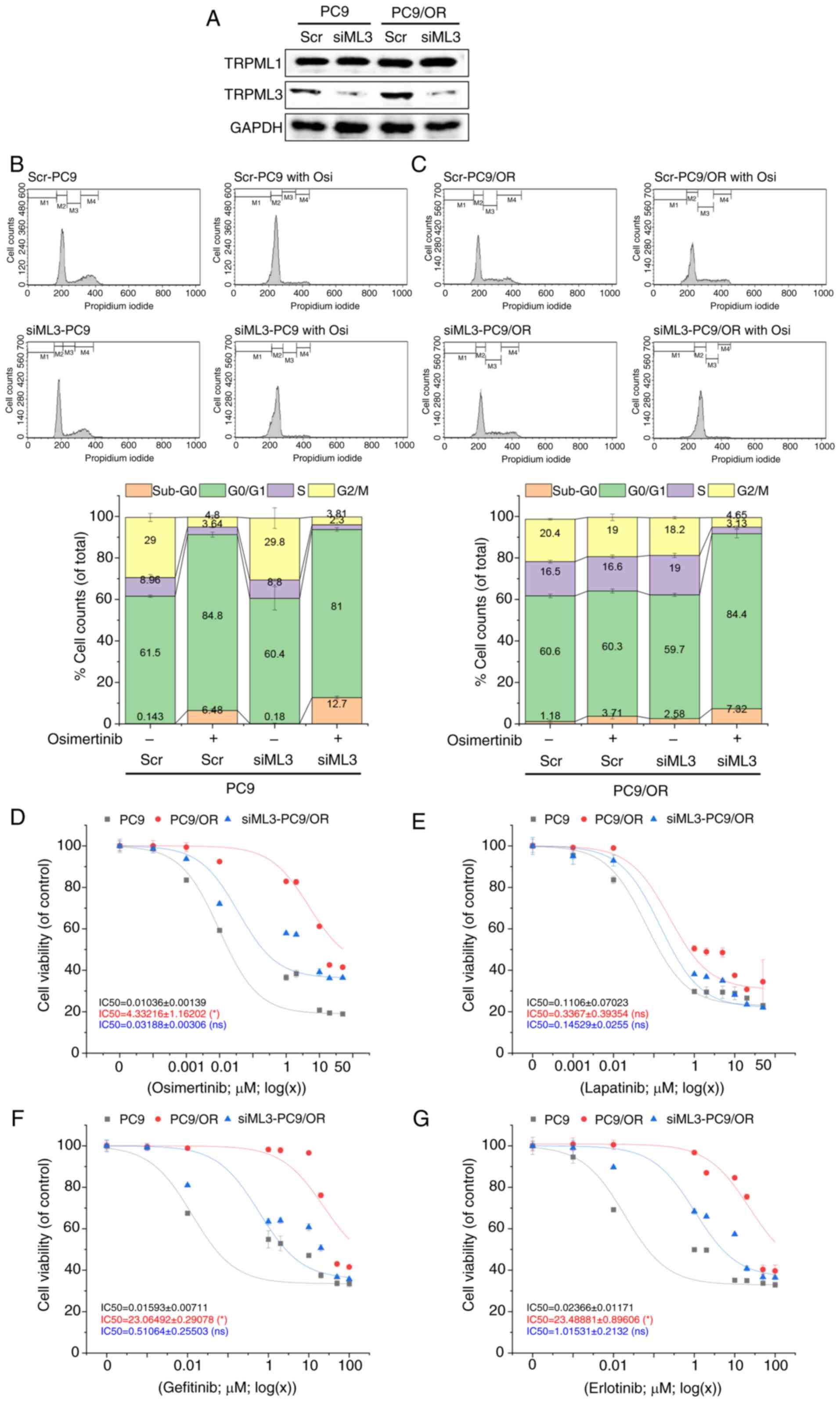

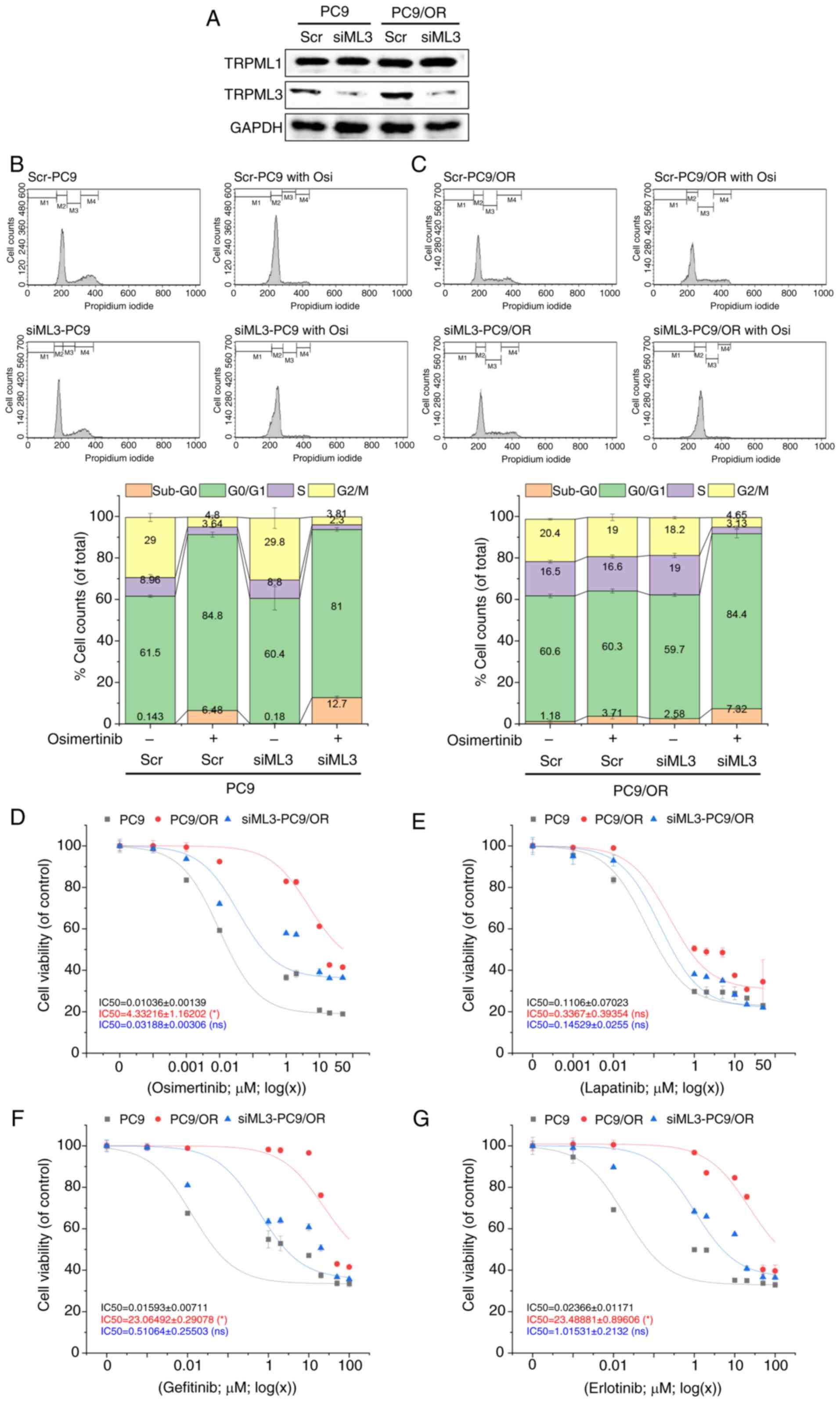

TRPML3 knockdown reduces multi-drug

tolerance in osimertinib-resistant PC9 cells

siRNA-mediated TRPML3 knockdown (siML3) was

next performed in PC9 cells and their osimertinib-resistant subline

PC9/OR. TRPML3 expression was efficiently reduced without affecting

TRPML1 expression (Fig. 2A). Next,

the effects of TRPML3 depletion on osimertinib-induced G0/G1

cell-cycle arrest was examined. Cells transfected with siML3 or

scrambled RNA (control) were incubated for 48 h with or without

0.01 µM osimertinib. In PC9 cells, TRPML3 knockdown did not

alter osimertinib-induced G0/G1 arrest but increased the sub-G0

population (Fig. 2B), suggesting

increased cell death. By contrast, TRPML3 knockdown in

PC9/OR cells restored their sensitivity to osimertinib-induced

G0/G1 arrest (Fig. 2C). All tested

TKIs, including osimertinib (Fig.

2D), lapatinib (Fig. 2E),

gefitinib (Fig. 2F) and erlotinib

(Fig. 2G), reduced PC9 viability in

a dose-dependent manner. By contrast, PC9/OR cells displayed

cross-resistance to all TKIs except for lapatinib. Finally,

TRPML3 knockdown restored the sensitivity to osimertinib and

other TKIs in these resistant cells. These findings indicate that

TRPML3 plays a critical role in mediating TKI resistance in NSCLC

cells.

| Figure 2.TRPML3 deletion restores sensitivity

to osimertinib-induced cell-cycle arrest and death in PC9/OR cells.

(A) Confirmation of TRPML3 siRNA knockdown in PC9 and PC9/OR cells,

with no effect on TRPML1 expression. GAPDH was used for

normalization. (B and C) Cell-cycle phase distributions in (B) PC9

and (C) PC9/OR cells transfected with siML3 or scrambled RNA (scr),

then treated with 0.01 µM osimertinib for 48 h. Flow cytometric

data are presented as percentages of cells per phase

(2×104 cells per sample, n=4). (D-G) Viability of PC9,

PC9/OR and siML3-PC9/OR cells treated with increasing

concentrations of (D) osimertinib, (E) lapatinib, (F) gefitinib, or

(G) erlotinib for 72 h, assessed by MTT assay. Data show

percentages relative to DMSO-treated controls (n=3). TRPML,

transient receptor potential mucolipin; si-, small interfering. |

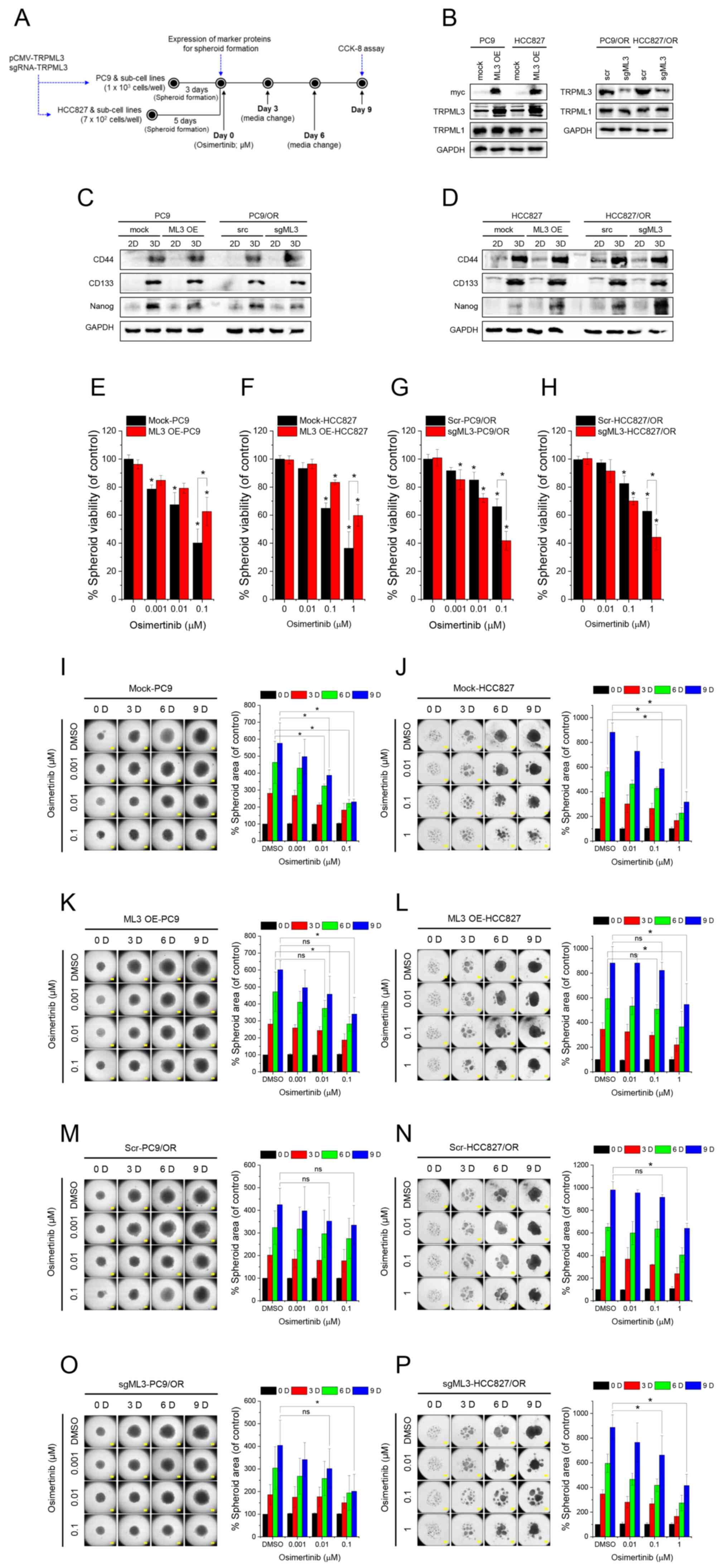

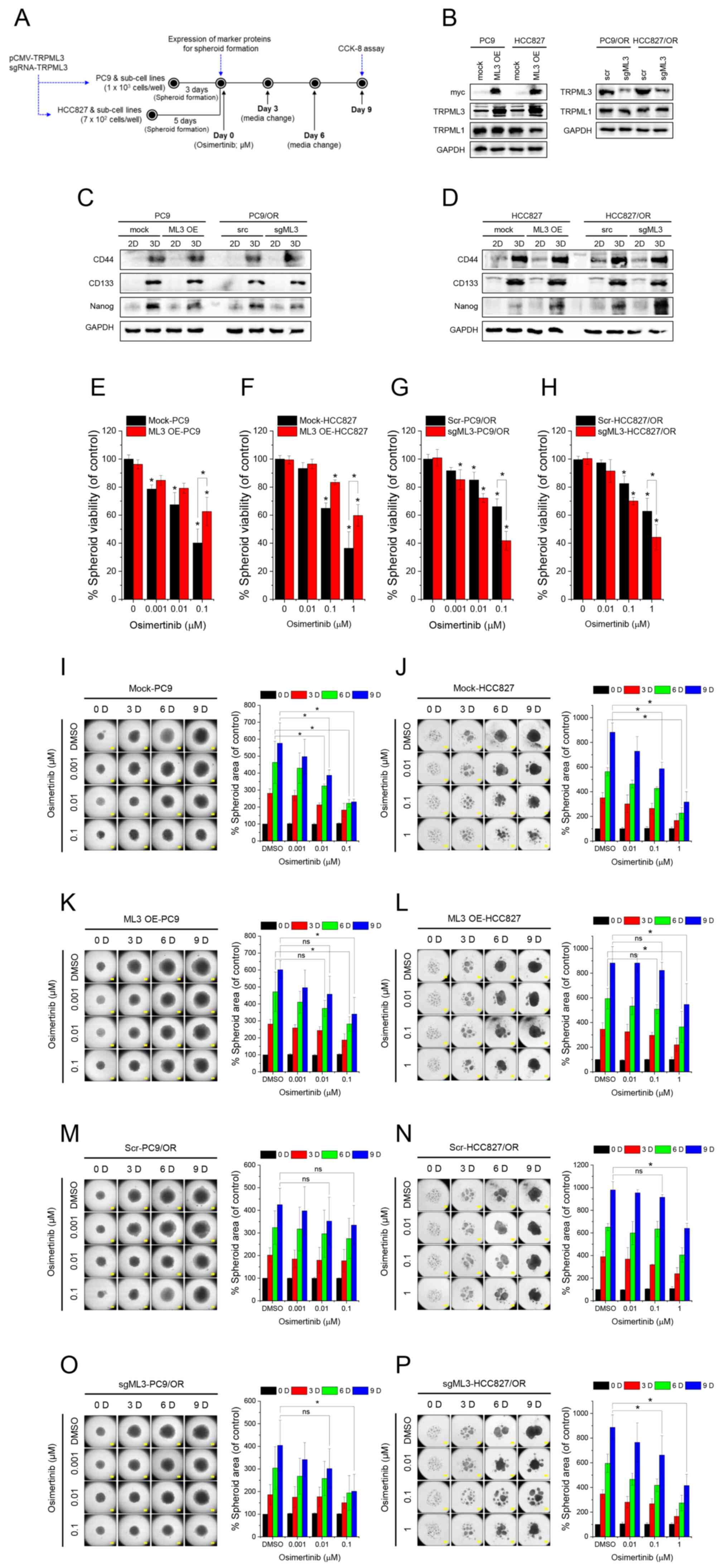

TRPML3 modulates osimertinib

sensitivity and growth in spheroids

To better mimic tumors in vivo, 3D spheroids

derived from TRPML3-overexpressing and -silenced cells

treated with osimertinib treatment for 9 days were employed. was

initiated on day 0 and maintained for 9 days. Spheroid viability

and size were assessed using CCK-8 assays and bright-field imaging,

respectively (Fig. 3A). Western

blotting confirmed changes in TRPML3 expression without affecting

TRPML1 expression (Fig. 3B).

Blotting with antibodies against the myc tag and TRPML3 verified

pCMV-TRPML3 expression in PC9 and HCC827 cells, whereas targeting

TRPML3 with sgRNA reduced endogenous TRPML3 expression in PC9/OR

and HCC827/OR cells. On day 0, increased expression of the spheroid

markers CD44, CD133 and Nanog was observed in spheroids, but not in

parental 2D cultures (Fig. 3C and

D). TRPML3 modulation did not affect spheroid formation. Next,

the effects of TRPML3 overexpression (Fig. 3E and F) and silencing (Fig. 3G and H) on osimertinib-induced

toxicity were assessed in spheroids derived from

osimertinib-sensitive (PC9 and HCC827) and -resistant (PC9/OR and

HCC827/OR) cells. Osimertinib produced a dose-dependent decrease in

spheroid viability in sensitive cell-derived spheroids (Fig. 3E and F), whereas those derived from

resistant cells exhibited greater tolerance (Fig. 3G and H). TRPML3 overexpression in

PC9 (ML3 OE-PC9) and HCC827 (ML3 OE-HCC827) spheroids attenuated

osimertinib-induced viability reductions at 0.1 µM (PC9) and 1 µM

(HCC827). Conversely, TRPML3 silencing significantly reduced

osimertinib tolerance in spheroids derived from PC9/OR and

HCC827/OR cells (Fig. 3G and H).

Consistent with these findings, intracellular TRPML3 levels

influenced osimertinib-induced reductions in spheroid size.

Spheroids were treated with osimertinib at the induced

concentrations; bright-field images were captured every 3 days

until day 9. Those derived from PC9, HCC827 and their sublines

continued to increase in size in the absence of osimertinib

(Fig. 3I-P). By contrast,

osimertinib treatment reduced spheroid size in both PC9 (Fig. 3I) and HCC827 (Fig. 3J) cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Spheroids from TRPML3-overexpressing PC9 (Fig. 3K) and HCC827 (Fig. 3L) cells exhibited increased

resistance to osimertinib, suppressing size reduction, whereas

those derived from PC9/OR (Fig. 3M)

and HCC827/OR (Fig. 3N) cells

maintained their size even at higher osimertinib concentrations

(0.01 and 0.1 µM for PC9/OR; 0.1 µM for HCC827/OR). TRPML3

silencing in PC9/OR (Fig. 3O) and

HCC827/OR (Fig. 3P) cells restored

osimertinib sensitivity, reducing spheroid size at 0.1 µM

osimertinib.

| Figure 3.TRPML3 modulates osimertinib

sensitivity and growth in spheroids. (A) Schematic representation

of the spheroid formation protocol and the subsequent osimertinib

treatment. (B) Expression levels of TRPML3 and −1 in PC9, HCC827

and their sublines (n=3). (C and D) Expression levels of spheroid

formation markers, CD44, CD133 and Nanog in spheroid lysates from

(C) PC9 and PC9/OR, (D) HCC827 and HCC827/OR, and conventional 2D

cultures (2D). (E-H) Spheroid viability assessed using Cell

Counting Kit-8 assays on day 9 of osimertinib treatment. Viability

is expressed as percentage relative to corresponding DMSO-treated

controls: (E) mock-PC9 and ML3 OE-PC9, (F) mock-HCC827 and ML3

OE-HCC827, (G) scr PC9/OR and sgML3-PC9/OR, (H) scr-HCC827/OR and

sgML3-HCC827/OR. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n=3). (I-P)

Bright-field images of spheroids derived from mock-PC9 (I; n=3),

mock-HCC827 (J; n=4), ML3 OE-PC9 (K; n=3), ML3 OE-HCC827 (L; n=4),

scr-PC9/OR (M; n=3), scr-HCC827/OR (N; n=4), sgML3-PC9/OR (O; n=3),

and sgML3-HCC827/OR (P; n=4) cells, captured at 3-day intervals

following spheroid formation. Osimertinib treatment (DMSO, 0.001,

0.01, 0.1, and 1 µM) was initiated on day 0. Columns adjacent to

each image show overall spheroid size relative to the control

DMSO-treated spheroids on day 0. Data are presented as the mean ±

SD. Scale bar, 400 µm. *P<0.05. TRPML, transient receptor

potential mucolipin; ns, not significant. |

TRPML3-mediated lysosomal

Ca2+ release drives osimertinib-induced intracellular

Ca2+ oscillations

To improve understanding of the TRPML3-mediated TKI

resistance, it was determined whether TRPML3 channel activity

contributed to osimertinib resistance by measuring

[Ca2+]i. Osimertinib treatment induced

intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in PC9 cells,

independently of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 4A). These oscillations were more

pronounced in resistant PC9/OR cells (Fig. 4B) and were inhibited by ML-SI1, a

mucolipin channel blocker (Fig.

4C). Ca2+i oscillation frequency was

significantly reduced in TRPML3-deficient cells but not in

TRPML1-deficient cells (Fig. 4D-F).

In TRPML3-deficient PC9 cells, Ca2+ spikes were

significantly reduced, whereas PC9/OR cells with TRPML3

overexpression exhibited enhanced oscillations (Fig. 4G). To determine whether these

oscillations depend on lysosomal Ca2+ release via

TRPML3, the TRPML3-GCaMP6 construct was used. GFP fluorescence

intensity closely mirrored the Fura-2 fluorescence pattern in

osimertinib-treated cells, consistent with TRPML3-mediated

lysosomal Ca2+ release (Fig.

4H and I).

![Osimertinib-induced

Ca2+i oscillations depend on lysosomal

Ca2+ release mediated by TRPML3.

[Ca2+]i measured using Fura-2/AM in cells

treated with 0.01 µM osimertinib in the absence of extracellular

Ca2+. (A and B) Osimertinib-induced

Ca2+i mobilization in (A) PC9 and (B) PC9/OR

cells. (C) Effects of ML-SI1, a TRPML channel blocker, on

osimertinib-induced Ca2+i oscillations. (D-F)

Ca2+i oscillations in PC9 cells transfected

with scrambled RNA (D; scr), TRPML1-targeting siRNA (E; siML1), or

TRPML3-targeting siRNA (F; siML3), following osimertinib treatment.

Each line represents Ca2+i mobilization in a

single cell. (G) Statistical analysis of Ca2+ spike

frequencies (*P<0.05, n=6). (H and I) Lysosomal Ca2+

release in (H) PC9 and (I) HCC827 cells expressing TRPML3-GCaMP6

and treated with 0.01 µM osimertinib in the absence of

extracellular Ca2+. ML-SA1 was used as a positive

control. Lines indicate changes in GFP intensity (F488)

in individual cells, reflecting TRPML3-mediated lysosomal

Ca2+ release. F340/380 and F488

values were normalized to the mean and are presented as

F340/380-norm and F488-norm, respectively.

TRPML, transient receptor potential mucolipin; si-, small

interfering; scr, scrambled.](/article_images/or/54/3/or-54-03-08946-g03.jpg) | Figure 4.Osimertinib-induced

Ca2+i oscillations depend on lysosomal

Ca2+ release mediated by TRPML3.

[Ca2+]i measured using Fura-2/AM in cells

treated with 0.01 µM osimertinib in the absence of extracellular

Ca2+. (A and B) Osimertinib-induced

Ca2+i mobilization in (A) PC9 and (B) PC9/OR

cells. (C) Effects of ML-SI1, a TRPML channel blocker, on

osimertinib-induced Ca2+i oscillations. (D-F)

Ca2+i oscillations in PC9 cells transfected

with scrambled RNA (D; scr), TRPML1-targeting siRNA (E; siML1), or

TRPML3-targeting siRNA (F; siML3), following osimertinib treatment.

Each line represents Ca2+i mobilization in a

single cell. (G) Statistical analysis of Ca2+ spike

frequencies (*P<0.05, n=6). (H and I) Lysosomal Ca2+

release in (H) PC9 and (I) HCC827 cells expressing TRPML3-GCaMP6

and treated with 0.01 µM osimertinib in the absence of

extracellular Ca2+. ML-SA1 was used as a positive

control. Lines indicate changes in GFP intensity (F488)

in individual cells, reflecting TRPML3-mediated lysosomal

Ca2+ release. F340/380 and F488

values were normalized to the mean and are presented as

F340/380-norm and F488-norm, respectively.

TRPML, transient receptor potential mucolipin; si-, small

interfering; scr, scrambled. |

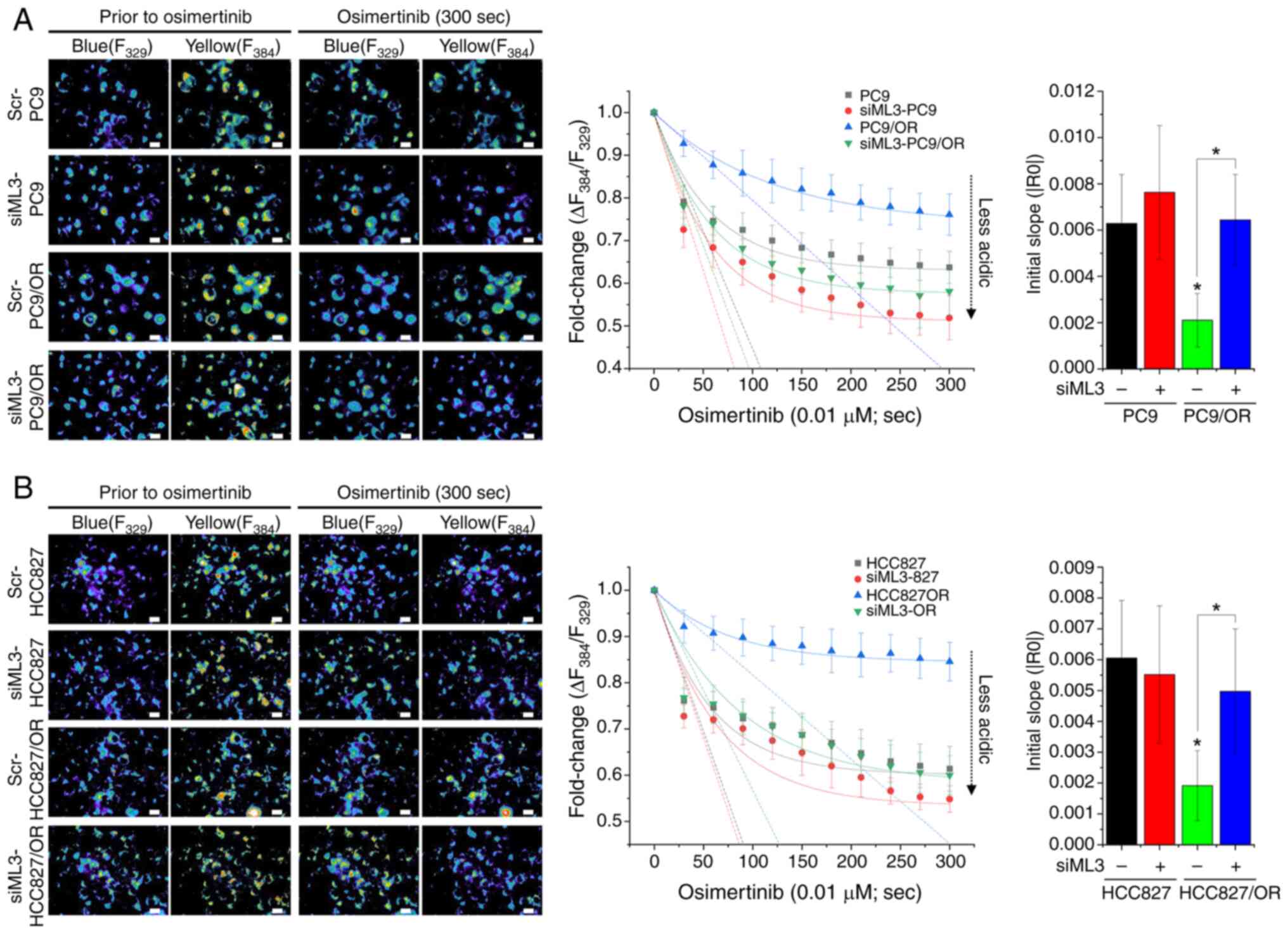

TRPML3 knockdown enhances

osimertinib-induced lysosomal pH increase

Lysosomal pH changes were next monitored using

LysoSensor Yellow/Blue DND-160. The baseline fluorescence

intensities were recorded before treatment, followed by continuous

perfusion with HEPES buffer containing osimertinib. Osimertinib

rapidly increased lysosomal pH in both PC9 (Fig. 5A) and HCC827 cells (Fig. 5B), reaching saturation at 60–65% of

baseline. By contrast, osimertinib-resistant cells (PC9/OR and

HCC827/OR) exhibited both a slower initial increase in lysosomal pH

and a lower saturation level. TRPML3 deletion in

osimertinib-resistant cells accelerated initial lysosomal pH

elevation and increased its saturation level compared with that in

scrambled control cells. These findings indicated that TRPML3 plays

a critical role in the regulation of lysosomal pH changes induced

by osimertinib in PC9 cells. Moreover, osimertinib-resistant NSCLC

cells increased sequestration of osimertinib within lysosomes, a

process that depends on TRPML3 expression. This suggests a link

between TRPML3-mediated lysosomal Ca2+ release and

regulation of lysosomal acidity.

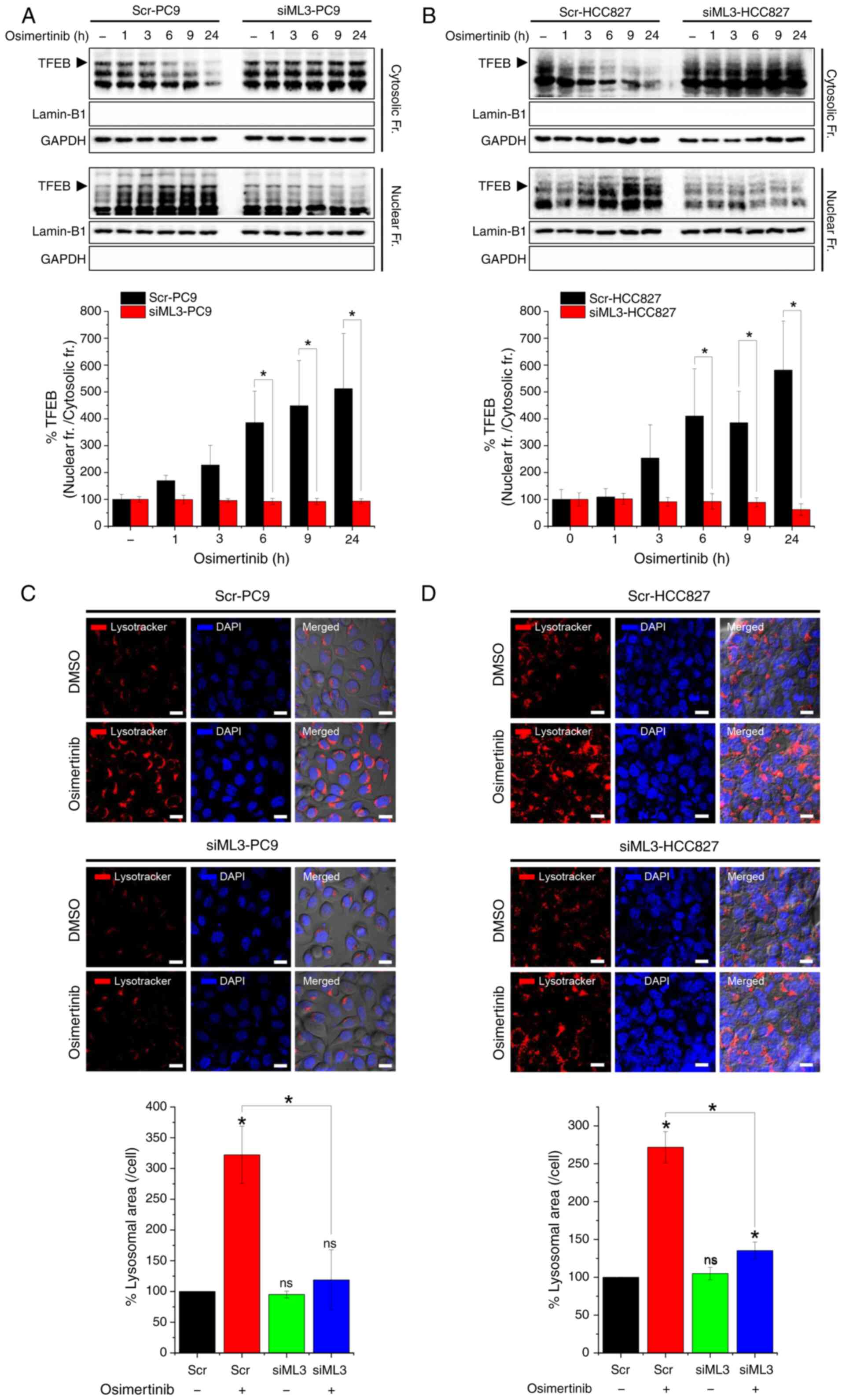

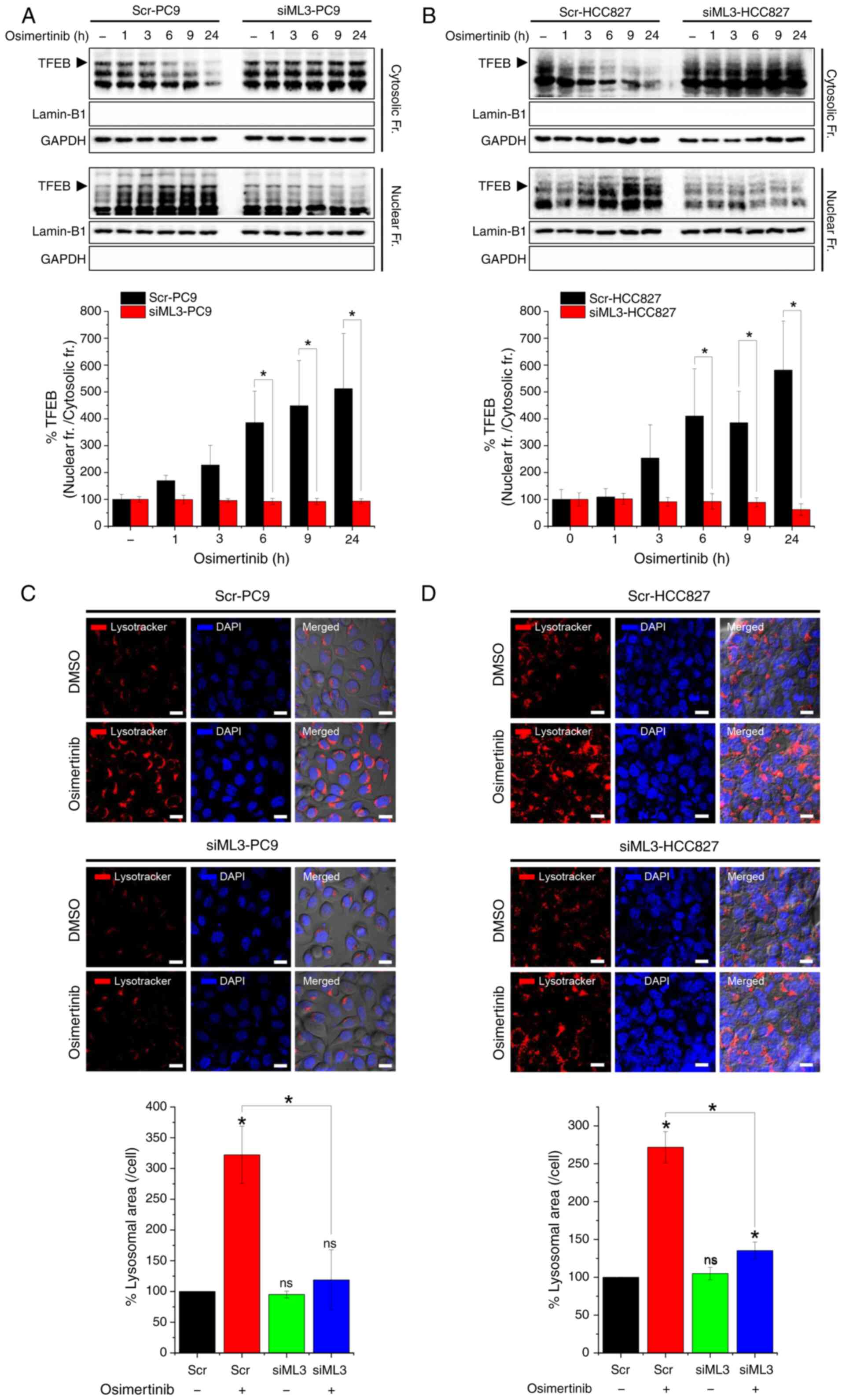

TRPML3 deletion impairs

osimertinib-induced TFEB nuclear translocation and lysosomal

biogenesis

Building on the role of TRPML3 in lysosomal acidity

regulation, it was determined whether it also plays a role in

osimertinib-induced lysosomal biogenesis, which has been primarily

associated with TPRML1. TFEB translocation from the cytosol to the

nucleus was analyzed by fractionating total cellular proteins.

Osimertinib increased the time-dependent nuclear translocation of

TFEB in both PC9 (Fig. 6A) and

HCC827 (Fig. 6B) cells. However,

TRPML3 deletion completely blocked TFEB translocation. LysoTracker

Red DND-99 staining revealed that the osimertinib-induced increase

in lysosomal area was significantly reduced in TRPML3-deficient PC9

(Fig. 6C) and HCC827 (Fig. 6D) cells. In TRPML3-deficient cells,

the lysosomal area was comparable to that in untreated control

cells (scr-PC9 and scr-HCC827). These findings indicate that TRPML3

is essential for the regulation of TFEB nuclear translocation and

lysosomal biogenesis in response to osimertinib-induced lysosomal

pH alteration.

| Figure 6.TRPML3 deficiency impairs

osimertinib-induced lysosomal biogenesis. (A and B) TFEB levels in

cytosolic and nuclear fractions of PC9 and HCC827 cells transfected

with TRPML3-targeting siRNA (siML3) or scrambled RNA (control) and

treated with 0.01 µM osimertinib for 1, 3, 6, 9, and 24 h. GAPDH

and lamin-B1 served as cytosolic and nuclear markers, respectively.

Quantitative analysis (lower panel) shows nuclear-to-cytosolic TFEB

ratios expressed as percentages relative to control (scr-PC9

without osimertinib treatment; n=3). (C and D) Lysosomes and nuclei

stained with LysoTracker Red DND-99 and DAPI after 24 h osimertinib

treatment of cells transfected with siML3 or scr. Relative

lysosomal area per cell is presented as a percentage of the control

(scr-PC9 without osimertinib treatment; n=3). Scale bar, 20 µm.

*P<0.05. TRPML, transient receptor potential mucolipin; si-,

small interfering; scr, scrambled; ns, not significant. |

Discussion

Osimertinib (AZD9291) is a first-line TKI used to

treat NSCLC with the T790M EGFR allele (30). Although initially effective, it

often fails to prevent the emergence of residual tumors that become

resistant over time (31). A known

mechanism underlying this resistance involves the lysosomal

sequestration of hydrophobic, weakly basic TKIs, such as gefitinib

and osimertinib, which reduces TKI toxicity and promotes multi-drug

resistance (32,33). However, the precise molecular

mechanisms regulating this sequestration remain poorly understood.

In the present study, lysosomal calcium channel TRPML3 (MCOLN3) was

assessed as a potential contributor to TKI resistance. RNA

expression analyses EGFR-mutant LUAD samples before and

after osimertinib treatment, revealed that TRPML3 expression

was specifically increased in osimertinib-residual tumors, unlike

TRPML1 and −2, suggesting a distinct role for TRPML3 in mediating

drug resistance. It was demonstrated that osimertinib-induced

increases in [Ca2+]i levels depend on

TRPML3-mediated lysosomal Ca2+ release, which is

critical for maintaining lysosomal acidity. Furthermore, TRPML3,

rather than TRPML1, was found to be crucial for lysosomal

biogenesis through Ca2+-dependent TFEB activation in

osimertinib-treated NSCLC cells. Experiments using NSCLC-derived

spheroids further confirmed that modulating TRPML3

expression alters osimertinib sensitivity, underscoring TRPML3 as a

potential therapeutic target to overcome drug resistance in

NSCLC.

Several studies have addressed the role of TRPML1 in

lysosomal signaling and autophagy; however, it remains less

characterized in cancer biology. The Cancer Genome Atlas data show

that TRPML3 expression is decreased in multiple cancers, including

LUAD (34). Our data provide the

first evidence, to the best of our knowledge, that increased TRPML3

expression in residual tumors following osimertinib treatment

contributes to drug resistance.

As an inward-rectifying cation channel (35), TRPML3 has been implicated in

autophagy, particularly in autophagosome biogenesis during

endocytosis and phagocytosis (17,36).

Autophagy plays a dual role in cancer, as it prevents tumor

initiation by mitigating cellular stress but supports tumor

progression by sustaining proliferation and metabolic activity

(37). Although the relationship

between TRPML3 and autophagy was not fully explored, they suggest

that TRPML3-mediated enhancement of autophagic flux in

osimertinib-resistant contributes to drug resistance. Key

limitations of the present study include the absence of in

vivo validation and the lack of direct investigation into the

interaction between TRPML3 and autophagy in the context of TKI

resistance. Given the established involvement of TRPML3 in

autophagy (17,36), future studies should determine

whether TRPML3-driven lysosomal Ca2+ signaling enhances

autophagy-mediated drug sequestration. To this end, important

future directions include monitoring autophagic flux in NSCLC cells

in response to changes in TRPML3 expression and evaluating whether

co-targeting TRPML3 and autophagy enhances the efficacy of

osimertinib in vivo. Clarifying the relationship between

TRPML3 and autophagy will deepen our understanding of resistance

mechanisms and guide the development of combination therapies.

Our study underscores the critical role of TRPML3 in

regulating the lysosomal sequestration of TKIs and promoting

lysosomal biogenesis in NSCLC cells. Previously, the authors

identified TRPML3 as a key contributor to drug resistance and

demonstrated that lysosomal Ca2+ release via TRPML3

facilitates lysosomal trafficking to the plasma membrane, enhancing

resistance. This mechanism is influenced by gefitinib-induced

lysosomal pH changes, as gefitinib is a lysosomotropic weak base

(38). Emerging evidence suggests

that lysosomal Ca2+ release mediated by TRPML3 is

essential for maintaining lysosomal acidification, as

Ca2+ efflux is coupled with H+ uptake into

the lumen (20,39–41).

Given that this acidification drives lysosomotropic agent

sequestration, TRPML3 likely enhances sequestration by preserving

the lysosomal proton gradient. Based on these studies, it was

hypothesized that TKI sequestration elevates lysosomal pH, which in

turn triggers lysosomal Ca2+ release via TRPML3 but not

TRPML1. This Ca2+ release is coupled with increased

H+ uptake, further enhancing sequestration. The present

findings support this hypothesis: osimertinib treatment rapidly

increased lysosomal pH; moreover, the rate of pH increase was

directly correlated with TRPML3 expression. Additionally,

osimertinib-induced Ca2+ mobilization depends on

TRPML3-mediated lysosomal Ca2+ release. These findings

suggest that osimertinib resistance is enhanced in NSCLC cells by

increasing the lysosomal sequestration of TKIs. By elucidating the

role of TRPML3 in these processes, the present study provides

valuable insights into drug resistance mechanisms and identifies

potential therapeutic targets.

It was observed that osimertinib-induced lysosomal

pH elevation does not favor TRPML1 activation, as TRPML1 functions

optimally in a more acidic environment. Prolonged TKI treatment

increases both lysosomal number and size (33,42).

While TRPML1 is well known for its role in lysosomal biogenesis

through Ca2+ release and TFEB dephosphorylation

(13), the mechanism by which

weak-base chemotherapeutics such as osimertinib induce lysosomal

Ca2+ release remains unclear. Given that TRPML3 is

activated at higher pH, it was hypothesized that it compensates for

TRPML1 by activating TFEB and promoting lysosomal biogenesis.

Consistent with this, it was observed that TRPML3 depletion

inhibited TFEB nuclear translocation and reduced

osimertinib-induced lysosomal biogenesis. These results provide new

insights into lysosomal regulation in cancer cells treated with

TKIs such as osimertinib. Further studies are needed to elucidate

the molecular pathways involved and evaluate the therapeutic

potential of targeting TRPML channels in cancer treatment.

In conclusion, a novel mechanism was identified, by

which TRPML3 contributes to osimertinib resistance in NSCLC by

regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function. Our results suggest a

compensatory relationship between TRPML3 and TRPML1 in response to

TKI-induced lysosomal changes. By identifying TRPML3 as a key

regulator, the present study provides new insights into the

molecular basis of drug resistance and highlights TRPML3 as a

promising therapeutic target.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Jin Kyung Rho

(Asan Medical Center, Ulsan University) and Dr Hyun Jin Kim

(Sungkyunkwan University) for providing NSCLC cell lines and

GCaMP-TRPML3 plasmid constructs, respectively.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Research

Foundation of Korea and funded by the Ministry of Education (grant

no. RS-2023-NR076426).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures of this article. The data generated in the present

study may be requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MSeoK contributed to data curation, formal analysis,

investigation, methodology, software, and wrote the initial draft.

MSeuK was responsible for conceptualization, formal analysis,

funding acquisition, investigation, project administration,

supervision, validation, and editing the manuscript. Both authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript and confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

TKI

|

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

LUAD

|

lung adenocarcinoma

|

|

TFEB

|

transcription factor EB

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

TRPMLs

|

transient receptor potential

mucolipins

|

|

MLIV

|

type IV mucolipidosis

|

|

RNA-seq

|

RNA-sequencing

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

References

|

1

|

Zhang Z, Yue P, Lu T, Wang Y, Wei Y and

Wei X: Role of lysosomes in physiological activities, diseases, and

therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 14:792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Savini M, Zhao Q and Wang MC: Lysosomes:

Signaling hubs for metabolic sensing and longevity. Trends Cell

Biol. 29:876–887. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hraběta J, Belhajová M, Šubrtová H, Merlos

Rodrigo MA, Heger Z and Eckschlager T: Drug sequestration in

lysosomes as one of the mechanisms of chemoresistance of cancer

cells and the possibilities of its inhibition. Int J Mol Sci.

21:43922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yamagishi T, Sahni S, Sharp DM, Arvind A,

Jansson PJ and Richardson DR: P-glycoprotein mediates drug

resistance via a novel mechanism involving lysosomal sequestration.

J Biol Chem. 288:31761–31771. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Seebacher N, Lane DJ, Richardson DR and

Jansson PJ: Turning the gun on cancer: Utilizing lysosomal

P-glycoprotein as a new strategy to overcome multi-drug resistance.

Free Radic Biol Med. 96:432–445. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhitomirsky B and Assaraf YG: Lysosomes as

mediators of drug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist Updat.

24:23–33. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Xu H and Ren D: Lysosomal physiology. Annu

Rev Physiol. 77:57–80. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kendall RL and Holian A: The role of

lysosomal ion channels in lysosome dysfunction. Inhal Toxicol.

33:41–54. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xu M and Dong XP: Endolysosomal TRPMLs in

cancer. Biomolecules. 11:652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bargal R, Avidan N, Ben-Asher E, Olender

Z, Zeigler M, Frumkin A, Raas-Rothschild A, Glusman G, Lancet D and

Bach G: Identification of the gene causing mucolipidosis type IV.

Nat Genet. 26:118–123. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Santoni G, Maggi F, Amantini C, Marinelli

O, Nabissi M and Morelli MB: Pathophysiological role of transient

receptor potential mucolipin channel 1 in calcium-mediated

stress-induced neurodegenerative diseases. Front Physiol.

11:2512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Soyombo AA, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, Rbaibi Y,

Bashllari E, Bisceglia J, Muallem S and Kiselyov K: TRP-ML1

regulates lysosomal pH and acidic lysosomal lipid hydrolytic

activity. J Biol Chem. 281:7294–7301. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Di Paola S, Scotto-Rosato A and Medina DL:

TRPML1: The Ca(2+)retaker of the lysosome. Cell Calcium.

69:112–121. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Qi J, Li Q, Xin T, Lu Q, Lin J, Zhang Y,

Luo H, Zhang F, Xing Y, Wang W, et al: MCOLN1/TRPML1 in the

lysosome: A promising target for autophagy modulation in diverse

diseases. Autophagy. 20:1712–1722. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Medina DL, Di Paola S, Peluso I, Armani A,

De Stefani D, Venditti R, Montefusco S, Scotto-Rosato A, Prezioso

C, Forrester A, et al: Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates

autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat Cell Biol. 17:288–299.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kim SW, Kim DH, Park KS, Kim MK, Park YM,

Muallem S, So I and Kim HJ: Palmitoylation controls trafficking of

the intracellular Ca2+ channel MCOLN3/TRPML3 to regulate

autophagy. Autophagy. 15:327–340. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kim SW, Kim MK, Hong S, Choi A, Choi JH,

Muallem S, So I, Yang D and Kim HJ: The intracellular

Ca2+ channel TRPML3 is a PI3P effector that regulates

autophagosome biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

119:e22000851192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Paroutis P, Touret N and Grinstein S: The

pH of the secretory pathway: Measurement, determinants, and

regulation. Physiology (Bethesda). 19:207–215. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Miao Y, Li G, Zhang X, Xu H and Abraham

SN: A TRP channel senses lysosome neutralization by pathogens to

trigger their expulsion. Cell. 161:1306–1319. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gerasimenko JV, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH

and Gerasimenko OV: Calcium uptake via endocytosis with rapid

release from acidifying endosomes. Curr Biol. 8:1335–1338. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Martina JA, Lelouvier B and Puertollano R:

The calcium channel mucolipin-3 is a novel regulator of trafficking

along the endosomal pathway. Traffic. 10:1143–1156. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liang J, Bi G, Sui Q, Zhao G, Zhang H,

Bian Y, Chen Z, Huang Y, Xi J, Shi Y, et al: Transcription factor

ZNF263 enhances EGFR-targeted therapeutic response and reduces

residual disease in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep. 43:1137712024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y and Gu J: fastp: An

ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics.

34:i884–i890. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow

J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M and Gingeras TR: STAR:

Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 29:15–21.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA

and Kingsford C: Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification

of transcript expression. Nat Methods. 14:417–419. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ and Smyth GK:

edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis

of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 26:139–140. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chu VT, Gottardo R, Raftery AE, Bumgarner

RE and Yeung KY: MeV+R: Using MeV as a graphical user interface for

Bioconductor applications in microarray analysis. Genome Biol.

9:R1182008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kurien BT and Scofield RH: Western

blotting: An introduction. Methods Mol Biol. 1312:17–30. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard

D, Cho BC, Gray JE, Ohe Y, Zhou C, Reungwetwattana T, Cheng Y,

Chewaskulyong B, et al: Overall survival with osimertinib in

untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 382:41–50.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ohashi K, Maruvka YE, Michor F and Pao W:

Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase

inhibitor-resistant disease. J Clin Oncol. 31:1070–1080. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Halaby R: Influence of lysosomal

sequestration on multidrug resistance in cancer cells. Cancer Drug

Resist. 2:31–42. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhitomirsky B and Assaraf YG: Lysosomal

sequestration of hydrophobic weak base chemotherapeutics triggers

lysosomal biogenesis and lysosome-dependent cancer multidrug

resistance. Oncotarget. 6:1143–1156. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wu M, Li X, Zhang T, Liu Z and Zhao Y:

Identification of a nine-gene signature and establishment of a

prognostic nomogram predicting overall survival of pancreatic

cancer. Front Oncol. 9:9962019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kim HJ, Li Q, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, So I,

Kiselyov K and Muallem S: Gain-of-function mutation in TRPML3

causes the mouse Varitint-Waddler phenotype. J Biol Chem.

282:36138–36142. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kim HJ, Soyombo AA, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, So I

and Muallem S: The Ca(2+) channel TRPML3 regulates membrane

trafficking and autophagy. Traffic. 10:1157–1167. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kim MS, Yang SH and Kim MS: TRPML3

enhances drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells by

promoting Ca2+-mediated lysosomal trafficking. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 627:152–159. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Christensen KA, Myers JT and Swanson JA:

pH-dependent regulation of lysosomal calcium in macrophages. J Cell

Sci. 115:599–607. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Morgan AJ, Platt FM, Lloyd-Evans E and

Galione A: Molecular mechanisms of endolysosomal Ca2+ signalling in

health and disease. Biochem J. 439:349–374. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Shen D, Wang X, Li X, Zhang X, Yao Z,

Dibble S, Dong XP, Yu T, Lieberman AP, Showalter HD and Xu H: Lipid

storage disorders block lysosomal trafficking by inhibiting a TRP

channel and lysosomal calcium release. Nat Commun. 3:7312012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

de Araujo MEG, Liebscher G, Hess MW and

Huber LA: Lysosomal size matters. Traffic. 21:60–75. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![Osimertinib-induced

Ca2+i oscillations depend on lysosomal

Ca2+ release mediated by TRPML3.

[Ca2+]i measured using Fura-2/AM in cells

treated with 0.01 µM osimertinib in the absence of extracellular

Ca2+. (A and B) Osimertinib-induced

Ca2+i mobilization in (A) PC9 and (B) PC9/OR

cells. (C) Effects of ML-SI1, a TRPML channel blocker, on

osimertinib-induced Ca2+i oscillations. (D-F)

Ca2+i oscillations in PC9 cells transfected

with scrambled RNA (D; scr), TRPML1-targeting siRNA (E; siML1), or

TRPML3-targeting siRNA (F; siML3), following osimertinib treatment.

Each line represents Ca2+i mobilization in a

single cell. (G) Statistical analysis of Ca2+ spike

frequencies (*P<0.05, n=6). (H and I) Lysosomal Ca2+

release in (H) PC9 and (I) HCC827 cells expressing TRPML3-GCaMP6

and treated with 0.01 µM osimertinib in the absence of

extracellular Ca2+. ML-SA1 was used as a positive

control. Lines indicate changes in GFP intensity (F488)

in individual cells, reflecting TRPML3-mediated lysosomal

Ca2+ release. F340/380 and F488

values were normalized to the mean and are presented as

F340/380-norm and F488-norm, respectively.

TRPML, transient receptor potential mucolipin; si-, small

interfering; scr, scrambled.](/article_images/or/54/3/or-54-03-08946-g03.jpg)