Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) is among the most prevalent and

lethal malignancies worldwide, ranking as the leading cause of

cancer-related mortality (1).

Early-stage LC is often asymptomatic and difficult to detect,

resulting in delayed diagnosis. For patients diagnosed at advanced

stages, the five-year survival rate remains dismally low at ~6%

(2). Globally, ~1.6 million new LC

cases are reported annually (3). In

men, LC constitutes the primary cause of both cancer incidence and

mortality, whereas among women, its incidence ranks second only to

breast and colorectal cancers (4).

LC poses a significant public health burden, with major risk

factors including exogenous environmental exposures such as tobacco

exposure, occupational and environmental carcinogens, and air

pollution, as well as endogenous biological factors such as genetic

predisposition, chronic lung disease, and hormonal and metabolic

factors (5,6). Despite substantial advancements in

diagnostic and therapeutic modalities in recent years, the overall

prognosis of LC remains poor, particularly for patients with

advanced disease (7,8).

Chemoprevention, defined as the use of natural or

synthetic agents to prevent, inhibit, delay, or reverse

carcinogenesis, has attracted considerable attention as a strategy

to combat LC (9). Although various

candidate chemo-preventive agents such as vitamin E, isotretinoin

and aspirin have been evaluated, none have demonstrated definitive

clinical efficacy (10). Natural

bioactive compounds, characterized by diverse pharmacological

activities and relatively low toxicity, have emerged as promising

candidates in cancer prevention and treatment, thereby becoming a

central focus of chemoprevention research (11). Ursolic acid (UA; PubChem Compound

ID: 64945) is a pentacyclic triterpenoid compound

(C30H48O3) widely distributed in

various plants, including calendula, lavender, oregano, Melaleuca,

sage, apple, rosemary and pear. It has garnered significant

scientific interest due to its diverse biological activities

(12,13). Previous studies have revealed that

UA possesses multifaceted biological activities, including

anti-inflammatory (14),

antioxidant (15), and anti-obesity

effects (16). Additionally, UA

exhibits therapeutic potential in a variety of conditions,

including diabetes (17), liver

diseases (18), cardiovascular

diseases (19), gastrointestinal

disorders (20) and

neurodegenerative diseases (21).

Of particular note is its remarkable anticancer potential (22). UA has been demonstrated to inhibit

tumor cell proliferation, induce apoptosis, and suppress tumor

invasion and metastasis across multiple cancer types, including

breast (23), pancreatic (24), prostate (25), colorectal (26), cervical (27) and renal cancers (28).

In LC chemoprevention, UA exerts its effects through

multiple molecular mechanisms. Although extensive preclinical

evidence supports the potential role of UA in LC prevention, the

precise molecular pathways remain to be fully elucidated. Moreover,

challenges related to the bioavailability, safety, and clinical

efficacy of UA must be addressed to facilitate its translational

application. The present review aims to comprehensively summarize

the chemo-preventive effects and molecular mechanisms of UA in LC,

thereby providing new insights and a theoretical framework for its

future application in LC prevention and therapy.

UA and its derivatives

UA is a pentacyclic triterpenoid compound that

naturally occurs either as triterpene saponins or in its free acid

form (29,30). It is also referred to as urson,

malol, prunol, or 3β-3-hydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid (31). UA has the molecular formula

C30H48O3, a molecular weight of

456.68 g/mol, and a melting point ranging from 283–285°C (12,32).

Its chemical structure comprises five rings-four six-membered and

one five-membered-along with multiple hydroxyl and carboxyl

functional groups. This distinctive molecular framework confers a

broad spectrum of biological activities, including

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial and anticancer

effects (33–35). Numerous studies have demonstrated

that UA exerts potent anticancer effects across various

malignancies (36,37). Its mechanisms of action extend

beyond conventional pathways such as apoptosis induction and

proliferation inhibition, encompassing unique molecular targets and

biological processes. Importantly, UA selectively targets cancer

stem cells (CSCs), impairing their self-renewal capacity, which is

critical for tumor initiation and recurrence (38). Moreover, UA exhibits

context-dependent modulation of autophagy, a process highly

relevant to cancer therapy. At low concentrations, UA activates the

AMP-activated protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway,

inducing protective autophagy that facilitates the clearance of

damaged cellular components and enhances chemoresistance.

Conversely, at high concentrations, UA inhibits autophagy by

blocking autophagosome-lysosome fusion, thereby promoting

autophagic cell death and augmenting its anticancer efficacy.

Beyond autophagy regulation, UA exerts precise anticancer effects

by modulating glycolytic metabolism (39), inducing structural modifications

(40), and remodeling the tumor

microenvironment (41). These

multifaceted actions underscore UA as a promising candidate for

cancer therapy.

To improve the pharmacological activity and

therapeutic potential of UA, various derivatives have been

synthesized through chemical modifications targeting its hydroxyl,

carboxyl and cyclic backbone moieties. Most reported UA derivatives

fall into two principal categories: modifications at C-3/C-28,

C-11, C-17 and C-28 positions, and structural alterations involving

C-2/C-3 and the A-ring (13,42).

Representative examples include UA-piperazine-dithio-carbamate

ruthenium (II) polypyridyl complexes, which induce antitumor

activity via necrosis (43);

corosolic acid (CA), a natural UA derivative that inhibits cancer

cell proliferation through β-catenin downregulation (44); UA232, which promotes apoptosis by

inducing cell cycle arrest and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress

(45); and compound 17, a

UA-derived small molecule that triggers cancer cell death through

macropinocytosis (46).

Collectively, these findings suggest that UA derivatives exert

anticancer effects through multi-target and multi-pathway

mechanisms, enhancing the pharmacological potency and drug-like

properties of UA. This not only reinforces its therapeutic efficacy

but also offers novel insights for the development of innovative

anticancer agents.

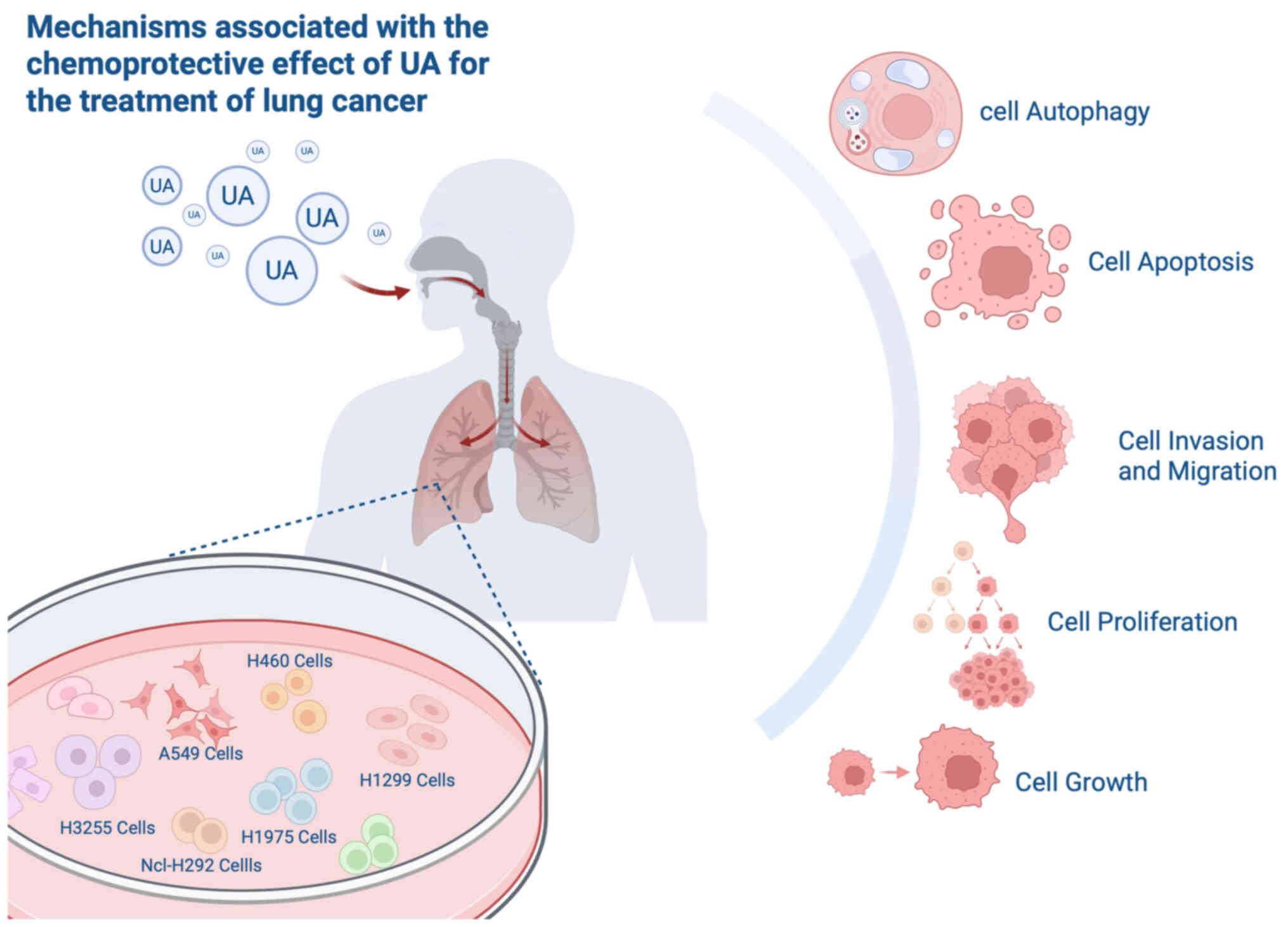

Chemo-preventive effects of UA on LC

Induction of autophagy and apoptosis

in LC cells

Apoptosis plays a pivotal role in tumor development,

progression and metastasis, yet cancer cells often evade apoptotic

mechanisms to sustain survival (47). Induction of apoptosis facilitates

the elimination of potentially harmful or precancerous cells,

whereas inhibition of apoptotic pathways contributes to

uncontrolled cell proliferation and malignant transformation

(48). UA primarily induces

apoptosis in LC cells through mitochondria-dependent (MD) pathways,

ER stress pathways, and modulation of associated signaling cascades

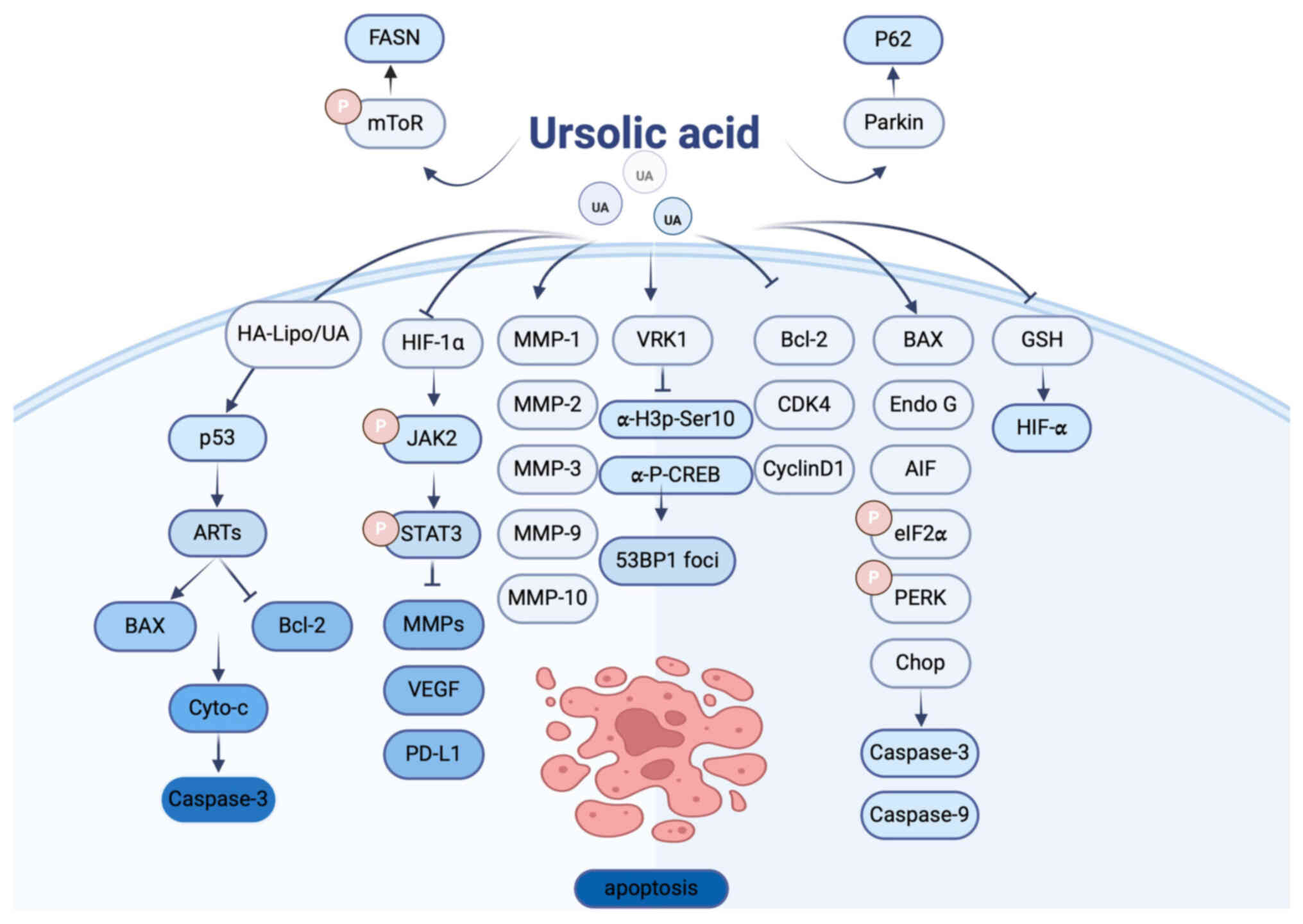

(Fig. 1).

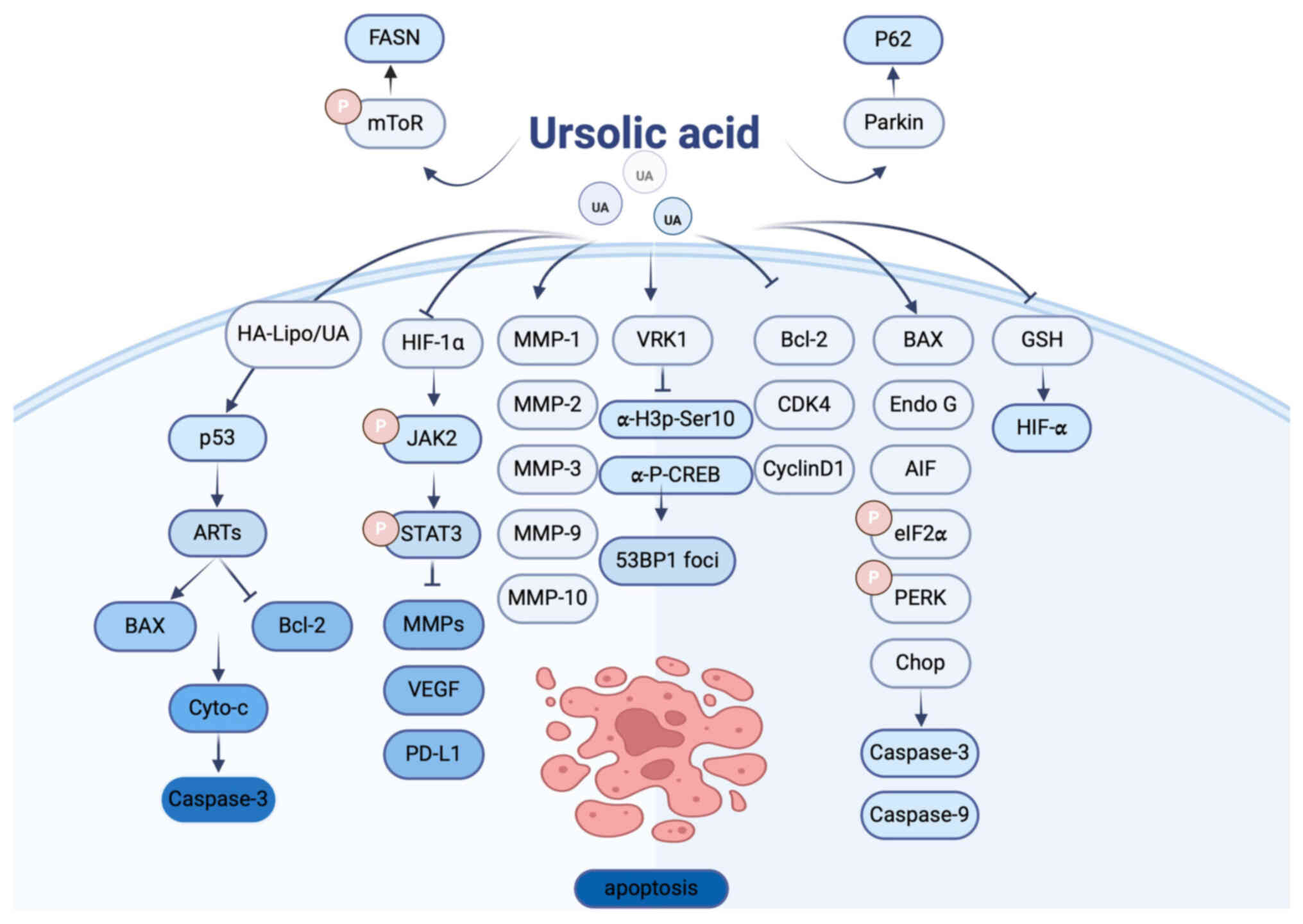

| Figure 1.Molecular targets regulated by UA and

their effects on cellular autophagy and apoptosis. UA, ursolic

acid; HA-Lipo/UA, hyaluronic acid-liposome UA; GSH, glutathione;

MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; ARTS, apoptosis-related protein in

the TGF-β signaling pathway; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; PD-L1,

programmed death-ligand 1; VRK1, vaccinia-related kinase 1; Chop,

C/EBP-homologous protein. Figure created using Adobe Illustrator

2024 (v28.0), Adobe Inc. |

Multiple studies have demonstrated that UA inhibits

the proliferation of non-small cell LC (NSCLC) cells in a dose- and

time-dependent manner while promoting apoptosis. UA activates

caspase-3 and caspase-9, downregulates the anti-apoptotic protein

Bcl-2, and upregulates the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, collectively

inducing apoptotic cell death in LC cells (49). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a

family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases, mediate extracellular

matrix (ECM) remodeling, which is implicated in various

pathological processes (50).

Notably, upregulation of MMP gene expression has been associated

with apoptosis induction in NSCLC cells. Lai et al (51) reported that treatment of H460 cells

with UA for 24 h led to increased expression of MMP-1, −2, −3, −9,

and −10, concomitant with activation of caspase-3, nuclear

morphological changes, and DNA fragmentation, thereby promoting

apoptosis. Additionally, Gou et al (45) demonstrated that the UA derivative

UA232 induces apoptosis in A549 and H460 cells by causing G0/G1

phase cell cycle arrest and upregulating C/EBP-homologous protein,

which triggers apoptosis via the ER stress pathway. Consistently,

UA has been shown to exert anticancer effects in both A549 and H460

cells by inducing G0/G1 arrest and apoptosis, thereby suppressing

tumor growth and progression (52).

Mitochondria are essential organelles involved in

regulating cellular functions such as autophagy and apoptosis under

stress conditions (53). Chen et

al (54) observed that UA

increases the expression of apoptosis-inducing factor and

endonuclease G in NCI-H292 cells, promoting their release via the

MD pathway and triggering apoptosis. To address UA's limited

solubility and lack of tumor specificity, Ma et al (55) developed a hyaluronic acid-liposome

UA delivery system (HA-Lipo/UA). Their results showed that

HA-Lipo/UA upregulated apoptosis-related protein in the TGF-β

signaling pathway and p53 expression in A549 cells, activated

caspase-3, and enhanced mitochondrial apoptosis, suggesting a

promising strategy for targeted LC therapy.

Mitophagy, a selective autophagic process that

degrades damaged mitochondria via lysosomal pathways, is another

mechanism by which UA exerts anticancer effects. Castrejon-Jiménez

et al (56) reported that UA

induces mitophagy in A549 cells through a Parkin-independent

mechanism, leading to p62 overexpression and subsequent apoptosis.

Furthermore, Song et al (57) demonstrated that UA significantly

enhances radiosensitivity in NSCLC cells, especially in

radiation-resistant cells overexpressing hypoxia-inducible factor 1

alpha (HIF-1α). By reducing the glutathione ratio and

downregulating HIF-1α in H1299/M-HIF-1α cells, UA increases

radiosensitivity and promotes radiation-induced cell death.

DNA damage repair (DDR) is critical for maintaining

genomic stability (58). A strong

correlation exists between DNA damage and the initiation of cell

death pathways (59). When DNA

repair mechanisms are compromised, apoptosis acts as a safeguard to

eliminate damaged cells (60).

Vaccinia-related kinase 1 (VRK1), a mitotic kinase frequently

overexpressed in lung adenocarcinoma, belongs to the nuclear

serine-threonine chromatin kinase family (61). UA has been shown to bind the

catalytic domain of VRK1, inhibiting its kinase activity. This

interference impairs VRK1-mediated 53BP1 foci formation, thereby

disrupting DDR and contributing to the therapeutic efficacy of UA

against LC (62).

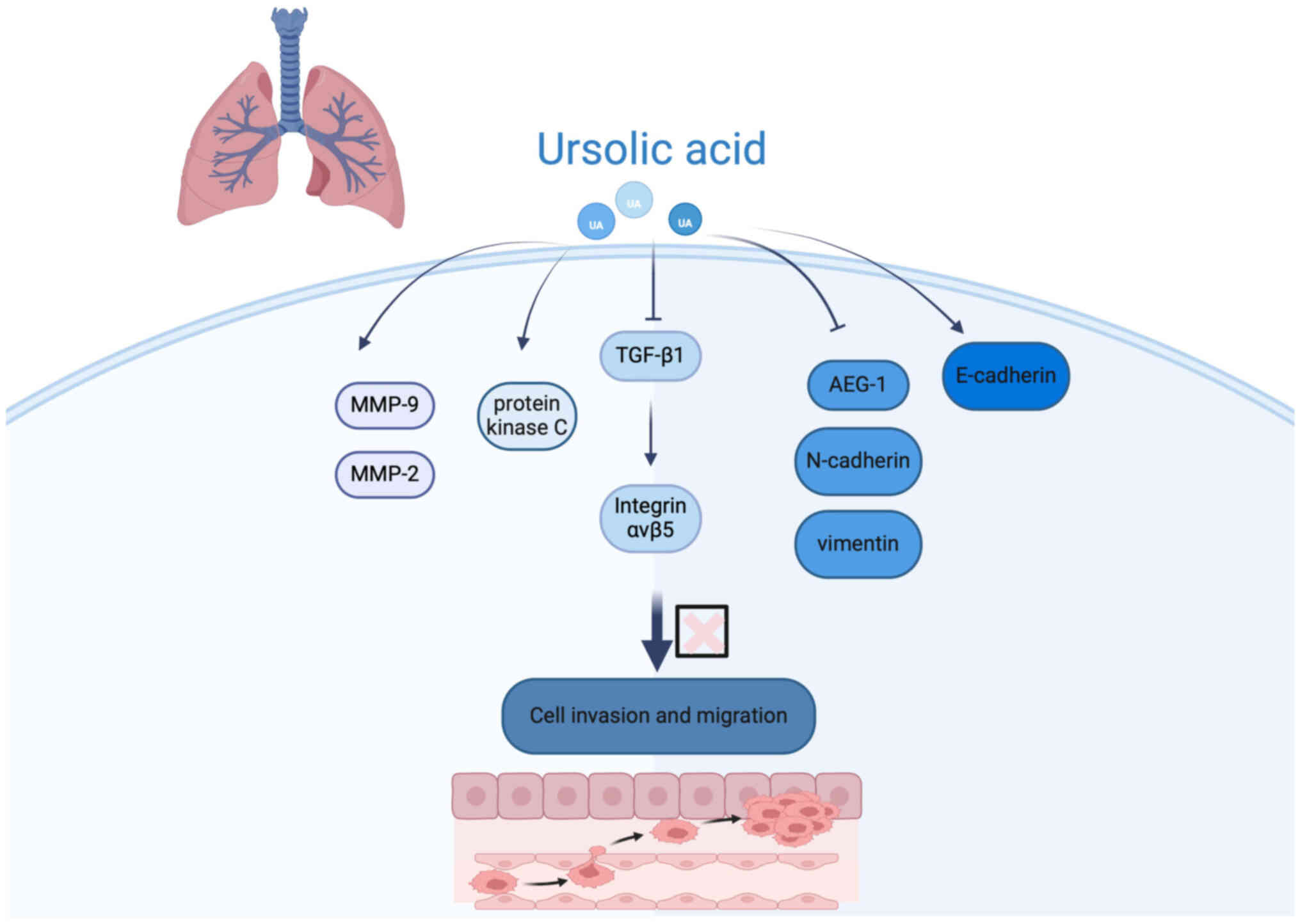

Inhibition of LC cell invasion and

migration

Tumor metastasis is a major contributor to the high

morbidity and mortality associated with cancer (63). Dysregulation of cancer cell

migration critically influences the ability of tumor cells to

detach from the primary site and invade surrounding tissues,

thereby facilitating metastasis (63).

Proteases play a vital role in cancer progression

not only by mediating ECM remodeling but also by regulating the

bioavailability of growth factors, pro-angiogenic factors, and

cytokines, which collectively promote tumor development through

both direct and indirect mechanisms (64). However, the clinical application of

UA is limited by its poor water solubility and insufficient

tumor-targeting capability (65).

To address these challenges, Xu et al (66) developed a novel multifunctional

nanoparticle formulation [HA-modified UA and astragaloside IV

(AS-IV)-loaded polydopamine nanoparticles (NPs;

UA/(AS-IV)@PDA-HA)]. This delivery system significantly enhanced

the cytotoxicity of UA and improved its anti-metastatic efficacy in

NSCLC cells. Furthermore, UA has been shown to inhibit LC cell

invasion in a concentration-dependent manner, with notable

suppression of cell migration observed at concentrations between 4

and 16 µmol/l (67).

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a

fundamental cellular program involved in embryonic development,

tissue repair and stem cell plasticity, but it also contributes

pathologically to fibrosis and cancer metastasis by enhancing

cellular motility and invasiveness (68). Experimental studies demonstrated

that UA reduces EMT induction in H1975 LC cells triggered by

transforming growth factor-β1, thereby inhibiting metastatic

potential (69). Additionally,

investigations in human NSCLC A549 cells revealed that UA

suppresses EMT by inhibiting the nuclear factor

Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B Cells (NF-κB) signaling

pathway, downregulating astrocyte-elevated gene-1 (AEG-1), and

modulating key EMT markers-upregulating epithelial marker

E-cadherin while downregulating mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and

vimentin. This mechanism effectively curtails tumor cell migration

and invasion, underscoring the promise of UA as an anti-metastatic

agent in LC treatment (Fig. 2)

(70).

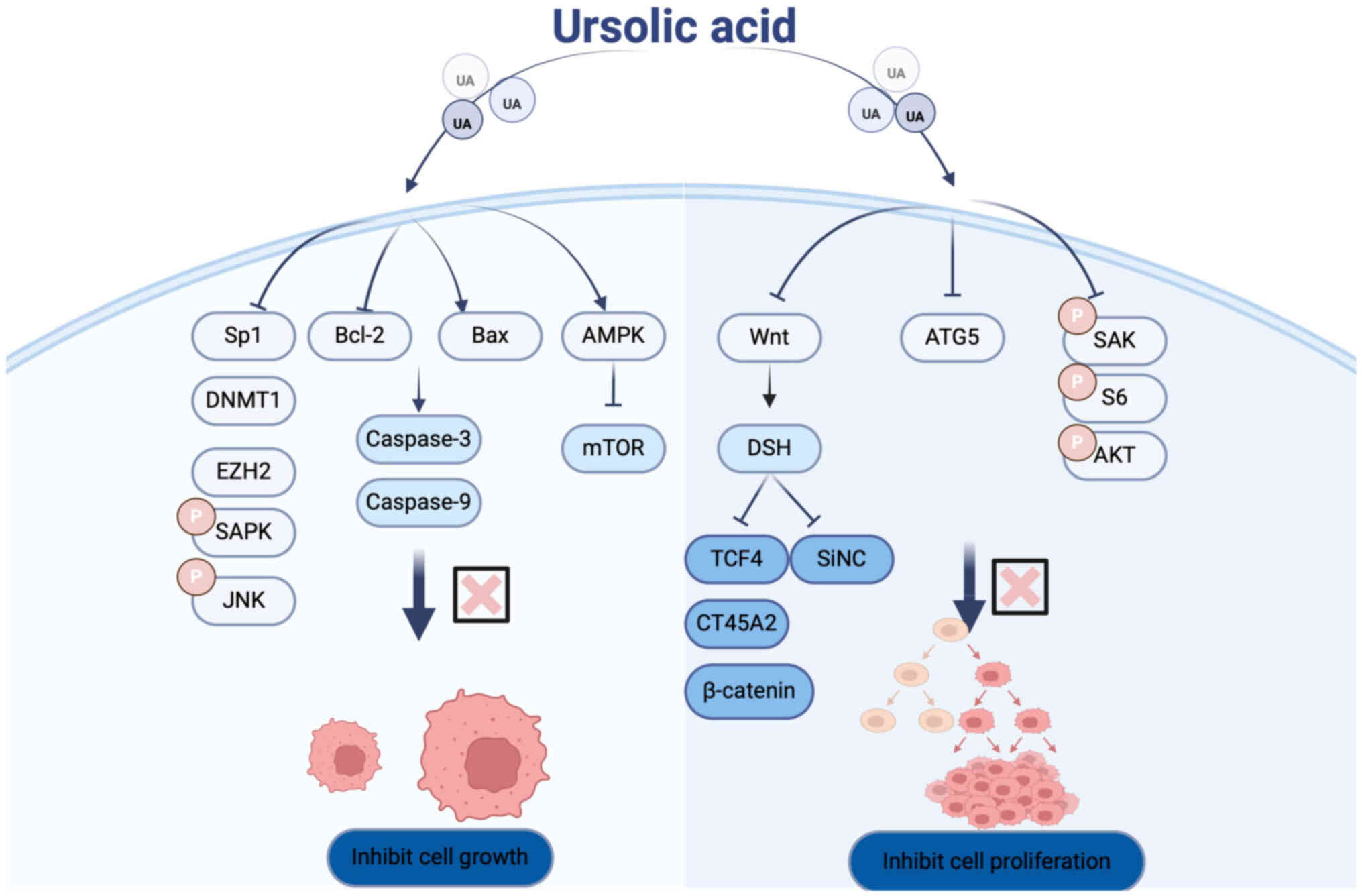

Inhibition of LC cell proliferation

and growth

Cell proliferation is fundamental to the normal

development and homeostasis of multicellular organisms.

Dysregulated cell proliferation is a hallmark of tumorigenesis and

can also contribute to congenital malformations (71).

Cancer/Testis Antigen Family 45 Member A2 (CT45A2)

is implicated as an oncogene in NSCLC and is associated with

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) T790 mutations. The

antitumor effects of UA in NSCLC predominantly depend on CT45A2

expression in H1975 cells. UA inhibits CT45A2 transcription by

targeting the β-catenin/transcription factor 4 (TCF4) signaling

pathway. Specifically, UA negatively regulates the

β-catenin/TCF4/CT45A2 axis, thereby suppressing the proliferation

of H1975 cells (72).

Autophagy-related gene 5 (ATG5) plays a pivotal role in autophagy

by participating in the formation of autophagic complexes and

autophagosomes, thus amplifying the autophagic response and

offering potential therapeutic avenues (73,74).

Mutations in ATG5 have been linked to various pathologies. Notably,

inhibition of ATG5 via chloroquine (CQ) or siRNA enhances UA's

anti-proliferative effects by suppressing autophagy, suggesting

that autophagy may serve as a protective mechanism in cancer cells

under UA treatment (75).

Cell proliferation involves the biosynthesis of

macromolecules such as proteins, lipids and nucleic acids, as well

as an increase in cell size and mass. Aberrant regulation of cell

proliferation and division contribute to tumor development. Wu

et al (76) demonstrated

that UA suppresses NSCLC cell proliferation by inducing

phosphorylation of stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal

kinase and subsequently downregulating Sp1 expression. Furthermore,

Way et al (49) reported

that UA inhibits LC cell proliferation through modulation of key

signaling proteins, including mTOR and AMPK. Their findings

indicate that UA activates AMPK in a dose- and time-dependent

manner, which in turn suppresses mTOR activity-a central regulator

of protein synthesis and cellular proliferation (Fig. 3).

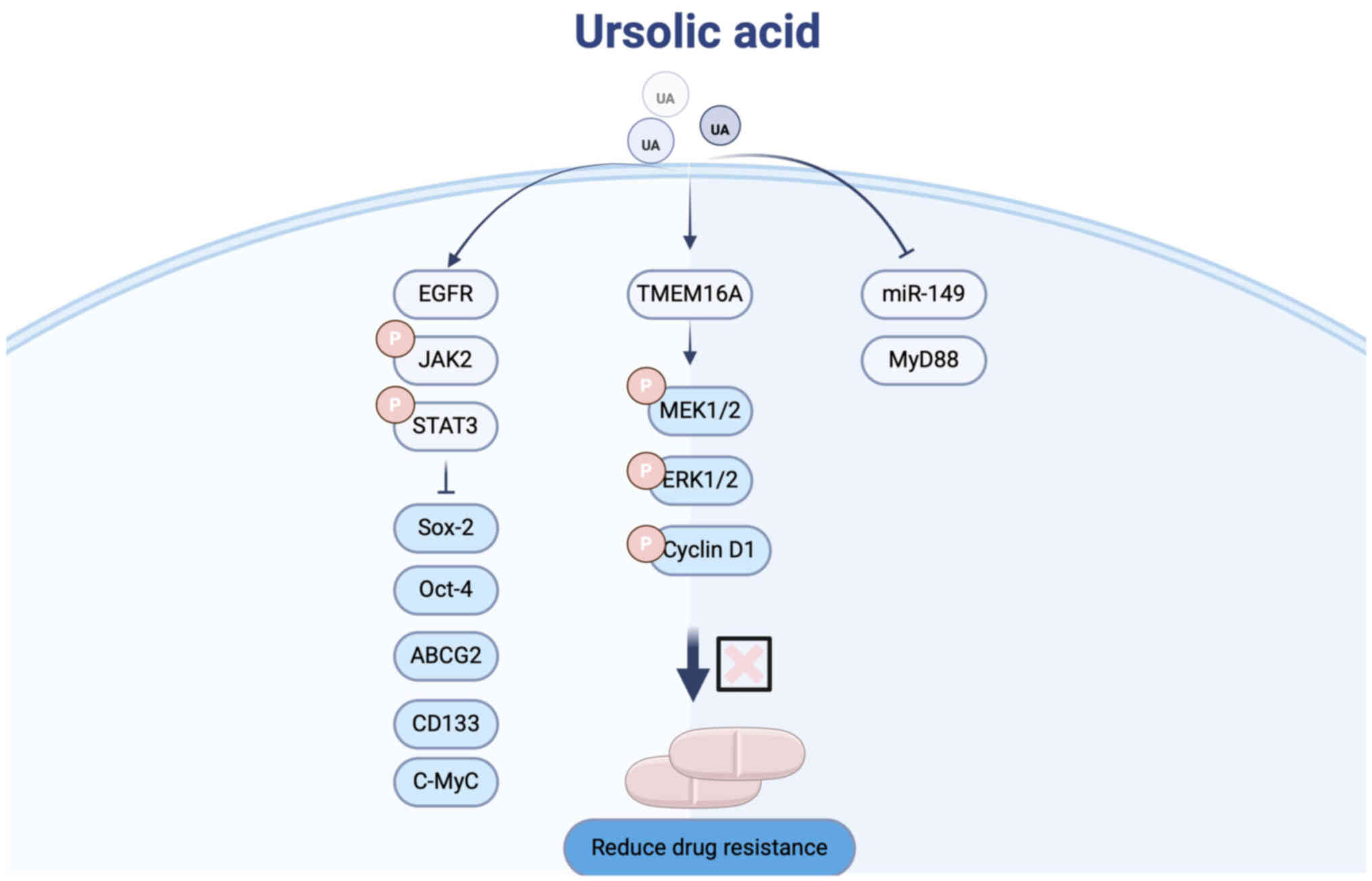

Combination with other anticancer

drugs

Chemotherapy remains a cornerstone in the treatment

of LC (77,78). However, the emergence of drug

resistance constitutes a significant barrier to successful

chemotherapy outcomes (79).

Cisplatin resistance, in particular, is a major cause of

therapeutic failure in patients with LC (80). Recently, UA has attracted increasing

attention for its potential to overcome cisplatin resistance in LC

(Fig. 4).

Fan et al (81) utilized the A549 human LC cell line

as a model for cisplatin-resistant cells and demonstrated that UA

treatment inhibited the activation of the Janus kinase 2/signal

transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Jak2/Stat3) signaling

pathway. This inhibition led to downregulation of

pluripotency-associated transcription factors and suppression of

CSC enrichment, thereby attenuating chemoresistance.

To improve UA delivery and targeting, Li et

al (82) developed a

hydrogel-based drug delivery system co-loaded with UA and

cisplatin. This platform enhances the targeting of UA to LC cells

by facilitating its binding to the LC-specific membrane protein

TMEM16A, effectively inhibiting lung adenocarcinoma progression.

The hydrogel system thus provides a promising strategy to

potentiate UA's therapeutic efficacy in resistant LC.

Furthermore, Chen et al (83) identified the miRNA-149-5p/MyD88

signaling axis as a critical mediator of chemoresistance in NSCLC

cells. Their study revealed that UA suppresses this signaling

pathway, thereby reducing cancer stemness, overcoming chemotherapy

resistance, and ultimately enhancing treatment efficacy in LC.

Novel drug carriers

Currently, most anticancer drugs have the drawback

of poor targeting, which can cause irreversible damage to the body

during treatment. New drug delivery systems aimed at ensuring drug

safety and efficient therapy may become key to enhancing the

efficacy of anticancer drugs (84).

Research indicates that nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems

(Nano-DDS) could potentially resolve the challenges associated with

drug administration in cancer therapy (85).

In an experiment by Wu et al (79), a biomimetic red blood cell membrane

(RBCM) nano-carrier, UA-loaded NPs coated with RBCM, was developed.

This novel biomimetic drug delivery platform enhanced the tumor

targeting, stability and biocompatibility of the UA NPs. It

addressed the clinical limitations of UA and improved its

bioavailability. This innovative biomimetic delivery system

significantly improved the anticancer efficacy in advanced NSCLC

model, offering a promising strategy for enhancing UA-based

treatments. In addition, Xu et al (66) developed a HA-modified

UA/AS-IV-loaded polydopamine (PDA) nanomedicine

(UA/(AS-IV)@PDA-HA). This nanomedicine effectively

enhanced the water solubility and targeting ability of UA. It

allows UA to specifically bind to the overexpressed cluster of

differentiation 44 on the surface of NSCLC cells. Moreover, the

modified nanomedicine significantly improved the cytotoxicity

mediated by UA and enhanced its ability to inhibit NSCLC cell

proliferation and metastasis. These findings suggest that UA has

great potential as an effective targeted anticancer drug for LC

therapy. Novel drug delivery systems have greatly enhanced the

ability of UA to target LC, enabling precise control that reduces

systemic toxicity and improves anticancer efficacy. However, the

integration and interaction between targeted therapies and UA in

addiction-related oncogenes of NSCLC remain unclear and require

further investigation.

Pharmacokinetics of UA

According to the Biopharmaceutics Classification

System (BCS), UA is classified as a Class IV drug, characterized by

low solubility and low permeability. Although UA demonstrates

unique advantages in the treatment of cancers such as LC, its

pharmacological efficacy is limited. Due to its lipophilic nature,

UA exhibits poor oral bioavailability and has difficulty

penetrating biological membranes, thereby reducing its therapeutic

effectiveness against tumors (86).

To overcome these challenges, Antonio et al (87) developed chitosan (CS)-modified

polylactic acid NPs encapsulating UA. Their study showed that this

nanoparticle system reduced the average particle size and promoted

the amorphous transformation of UA, enabling sustained release.

This significantly reduced cytotoxicity in tumor cells and enhanced

UA's oral absorption, clearance rate and metabolic efficiency in

rat models. Furthermore, Yang et al (88) demonstrated that amorphous UA NPs

prepared using the supercritical antisolvent technique effectively

improved UA's supersaturation, solubility and absorption. In

another study, Yu et al (89) formulated a supramolecular

co-amorphous system combining UA and piperine. Through differential

scanning calorimetry and scanning electron microscopy, it was

confirmed that the co-amorphous system significantly enhanced UA's

oral bioavailability and solubility in physiological media compared

to its crystalline form.

Regarding drug absorption, high-performance liquid

chromatography-mass spectrometry was used to analyze the tissue

distribution of UA in rats 1 h after oral administration. The study

revealed that UA concentrations were highest in the lungs, followed

by the spleen, liver, brain, heart and kidneys, in descending order

(90). Additionally, Wang et

al (91) found that a novel

CS-coated UA liposome achieved significantly higher accumulation at

tumor sites in mice compared with conventional UA liposomes and

free UA. These findings offer new insights and strategies for

enhancing UA's therapeutic efficacy against LC.

In terms of drug metabolism and excretion, research

on UA remains relatively limited. Available studies indicate that

UA is primarily metabolized in the human body by the hepatic

cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme system, along with phase II

conjugation reactions. In Caco-2 cells, CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 play key

roles in UA metabolism, and the PXR-RXRα pathway has been shown to

significantly upregulate CYP2C9 expression, thereby promoting UA

biotransformation (92).

In summary, although UA shows promising

pharmacokinetic behavior, further studies are needed to fully

elucidate its absorption, metabolism and elimination profiles,

which will be essential for advancing its clinical application.

Conclusion and outlook

LC, a malignant tumor originating from lung tissue,

is one of the most common cancers worldwide and a leading cause of

cancer-related mortality (93,94).

UA plays a significant role in the treatment of LC, with mechanisms

that include inhibiting cell proliferation, invasion and migration,

and reducing drug resistance. These effects involve signaling

pathways such as β-catenin, β-catenin/TCF4/CT45A2, NF-κB,

Jak2/Stat3, and the regulation of related genes such as ATG5,

CT45A2, MMP and AEG-1, as well as the expression of proteins such

as Bcl-2, Bax, upregulation of E-cadherin, downregulation of

N-cadherin, vimentin, mTOR and sp1, alongside the involvement of

proteases and kinases such as caspase-3, caspase-9, urokinase,

cathepsin B, AMPK and VRK1 (Table

I).

| Table I.Mechanism of action of ursolic acid

in lung cancer. |

Table I.

Mechanism of action of ursolic acid

in lung cancer.

| First author/s,

year | Disease | Real modules

(Animal/Cell/Patient) | Possible

mechanisms | Targets | Doses | Treatment

period | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kang et al,

2021 | Lung cancer | Cell: A549,

H460 | Inducing apoptosis,

inhibiting | MMP2↓, MMP3↓, | 10 µM, | 24 h | (52) |

|

|

|

| cell proliferation,

and concen- | MMP9↓, PD-L1↓, | 20 µM |

|

|

|

|

|

| trating on blocking

the cell cycle. | CDK4↓, CCND1↓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CCNE1↓,

CDKN1A↑, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CDKN1B↑,

VEGF↓, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| pSTAT3↓ |

|

|

|

| Way et al,

2014 |

| Cell: A549,

H460 | Induces apoptosis

and inhibits | Caspase-3↑,

Caspase-9↑, | 30 µM | 24; 48 h | (49) |

|

|

|

| cell

proliferation. | Bax↑, Bcl-2↓,

p-mTOR↓, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FASN↓ |

|

|

|

| Lai et al,

2007 |

| Cell: H460 | Induces apoptosis

of tumor cells. | MMP-1↑,

MMP-2↑, | 10 µM | 24 h | (51) |

|

|

|

|

| MMP-3↑,

MMP-9↑, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MMP-10↑,

Caspase-3↑ |

|

|

|

| Gou et al,

2020 |

| Cell: H460,

A549 | Induces apoptosis

by activating | CHOP↑, Cyclin

D1↓, | 0-50 µM | 24, 48, | (45) |

|

|

|

| the endoplasmic

reticulum stress | CDK4↓p-PERK↑, |

| 72 h |

|

|

|

|

| pathway, arresting

the cell cycle. | p-eIF2α↑,

eIF2α↑ |

|

|

|

| Chen et al,

2019 |

| Cell: NCI-H292 | Induces apoptosis

through | AIF↑, Endo G↑, | 3, 6, 9, 12 | Respectively | (54) |

|

|

|

|

mitochondrial-dependent | BCL-Xs↑ | and 15 µM | 24, 48 h |

|

|

|

|

| pathway. |

|

|

|

|

| Ma et al,

2023 |

| Cell: A549 | Induces

mitochondrial apoptosis, | ARTS↑, p53↑, | 20 µg/ml | 24 h | (55) |

|

|

|

| create HA-Lipo/UA

delivery | ascapase-3↑, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| system. | Cyto-C↑, Bcl-2↓,

Bax↑ |

|

|

|

| Castrejon- |

| Cell: A549 | Induces apoptosis,

induces | P62↑, Parkin↑ | 10 µg/ml | 24, 48 h | (56) |

| Jimenez et

al, 2019 |

|

| mitochondrial

phagocytosis. |

|

|

|

|

| Song et al,

2017 |

| Cell: H1299 | Induces cell death,

enhances cell radiosensitivity. | GSH↓, HIF-1α↓ | 50, 80 µg/ml | 24 h | (57) |

| Kim et al,

2015 |

| Cell: A549 | Induces apoptosis

and impedes | 53BP1 foci↓, | 50 µM | 12 h | (62) |

|

|

|

| DNA damage repair

capability. | α-p-CREB↓, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| α-H3 p-Ser10↓ |

|

|

|

| Lamouille et

al, |

| Cell: HNBE, | Reduces cell

invasion, reduce | MMP-9↑,

MMP-2↑, | 2, 4, 8, | 48 h | (68) |

| 2014 |

| A549, H3255 | cell migration,

reduces cell | protein kinase

C↓ | 16 µMol/l |

|

|

|

|

| and Calu-6 | activity. |

|

|

|

|

| Liu et al,

2013 |

| Cell: H1975 | Inhibits cell

invasion and | EMT↓, MMP-2↓, | 0, 1, 5, 10, | 24 h | (70) |

|

|

|

| migration. | MMP-9↓,

Integrin | 15, 20, 25, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| αvβ5↓ | 50, 100 ng/l |

|

|

| Jesudason et

al, |

| Cell: A549 and | Inhibits cell

metastasis and EMT | AEG-1↓,

E-cadherin↑, | 5, 10, 20, 30, | 24 h | (71) |

| 2000 |

| H1975 |

| N-cadherin↓,

vimentin↓ | 40 µM |

|

|

| Higgins et

al, |

| Cell: PC9,

H1299, | Inhibits cell

proliferation. | Sp1↓, DNMT1↓,

EZH2↓, | 30 µM | 48 h | (77) |

| 2009 |

| A549, H1650, H358

and H1975 |

| SAPK/JNK↓ |

|

|

|

| Way et al,

2014 |

| Cell: A549,

H460 | Inhibits cell

proliferation. | AMPK↑, mTOR↓, | 30 µM | 24, 48 h | (49) |

|

|

|

|

| Caspase-3↓,

Caspase-9↓, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bcl-2↓, Bax↑ |

|

|

|

| Changotra et

al, |

| Cell: H1975 | Inhibits cell

proliferation. | CT45A2↓,

transcription | 25 µM | 24, 48, 72 h | (73) |

| 2022 |

|

|

|

factor/β-catenin↓, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| TCF4↓, siNC↓ |

|

|

|

| Wu et al, 2015 |

| Cell: H460,

H1975, | Inhibits cell

proliferation and | ATG5↓, p-SAK↓, | 10 µM, | 24, 48, 72 h | (76) |

|

|

| A549, H1299, H520,

H82 and H446 | autophagy-related

genes. | p-S6↓, p-AKT↓ | 15 µM |

|

|

| Li et al, 2024 |

| Cell: A549 | Reduces cell

resistance and | Oct-4↓,

Sox-2↓, | 10, 20, 30, | 48 h | (82) |

|

|

|

| inhibits the

enrichment of tumor stem cells. | c-Myc↓, Jak2↑,

Stat3↑ | 40 µM |

|

|

| Chen et al,

2020 |

| Cell: LA795 | Inhibits neural

pathways, induces | TMEM16A↓, | 5, 10, 15, 20, | 24, 48, 72 h | (83) |

|

|

|

| DNA damage and cell

membrane | p-MEK1/2↓, | 30, 50 µM |

|

|

|

|

|

| damage, and design

hydrogel | p-ERK1/2↓, Cyclin

D1↓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| drug delivery

systems to enhance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| targeting

ability. |

|

|

|

|

| Perez- |

| Cell: NSCLC,

A549 | Reduces chemical

resistance, | miR-149↓,

MyD88↓ | 5, 10, 20 µM | 24, 48, 72 h | (84) |

| Herrero et

al, |

|

| inhibits miRNA,

weakens |

|

|

|

|

| 2015 |

|

| stemness of

cells. |

|

|

|

|

Due to the limited water solubility, poor targeting

ability, and drug resistance of UA (95), the development of novel DDS,

including Nano-DDS and hydrogel-based delivery systems, has greatly

addressed these issues. These innovations significantly enhance the

delivery efficiency, targeting ability and bioavailability of UA,

improving the effectiveness of monotherapy and boosting the

antitumor effect through synergistic strategies. Furthermore, Ram

Kumar Pandian et al (96)

found that polyhydroxybutyrate NPs could deliver UA, enhancing its

stability and bioactivity, thus improving the treatment of tumors.

In another study by Sharma et al (97), HA-UA conjugates were used to prepare

PTX-loaded HA-UA NPs, which significantly inhibited tumor cell

proliferation in experimental models, offering new ideas and

methods for combined chemotherapy delivery. If these two delivery

systems are applied to the treatment of LC, they might yield

unforeseen effects and become a new direction for future research.

In addition, smoking as an important factor affecting LC is

detrimental to the whole process of carcinogenesis. It has been

identified that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarettes can

affect the metabolism of drugs by key drug-metabolizing enzymes of

cytochrome P450 and isoforms of the glucuronosyltransferase family,

shortening the duration of drug action by accelerating the

metabolism of related drugs and thus affecting therapeutic efficacy

(98). In addition, Zevin et

al (99) found that smoking

significantly upregulated CYP2E1 activity, increasing the rate of

metabolizing drugs while activating carcinogens and increasing the

risk of disease. Whether smoking affects the metabolism and

utilization of natural active ingredients, such as UA, has not been

confirmed by relevant experiments, and the authors will further

explore this issue in future studies.

Although UA shows remarkable therapeutic potential

in LC treatment, there are still some limitations: First, low

bioavailability: Its poor water solubility results in low

absorption and bioavailability in the body. Second, lack of

clinical trial data: Most studies on UA in LC remain at the

laboratory stage, lacking large-scale clinical trials to support

its safety and efficacy. In particular, clinical evidence for UA

combination chemotherapy in non-small cell carcinoma remains low

and a distant dream. Third, Dose and administration challenges: In

clinical application, determining the appropriate dose is crucial.

A very low dose may result in ineffective treatment, while a very

high dose could cause toxicity. Further experimental research is

needed to optimize dosing and administration methods. Fourth, drug

interactions: UA may interact with other drugs, influencing their

metabolism and therapeutic effects. Identifying interactions with

other drugs is one of the future research directions. Fifth, side

effects and toxicity: While UA is considered a relatively safe

natural compound, high doses or prolonged use may still produce

toxicity and side effects, which need further investigation. Sixth,

individual differences: Patients may have different responses to UA

based on factors such as genetic background, tumor type, stage and

overall health. Hence, it is essential to avoid generalizing

treatment approaches.

In conclusion, while UA has made significant

progress in non-clinical research, some issues and limitations

remain. In the future, the authors will focus research on the

cultivation of real animal cells, to deepen the analysis of their

multi-target regulatory networks and develop efficient delivery

systems, to promote the clinical translation of UA and its

derivatives, and ultimately to realize the leap from cellular

evidence to human disease intervention (Fig. 5).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Youth Program of the

Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant no.

ZR2023QH079).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZL wrote the manuscript and drew the pictures. QC

and ZC collected and organized literature. TP and JB proofread the

manuscript. FM are fully responsible for the study designing,

research fields, drafting, and finalizing the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Frydrychowicz M, Kuszel Ł, Dworacki G and

Budna-Tukan J: MicroRNA in lung cancer-a novel potential way for

early diagnosis and therapy. J Appl Genet. 64:459–477. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Juang YR, Ang L and Seow WJ: Predictive

performance of risk prediction models for lung cancer incidence in

Western and Asian countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Sci Rep. 15:42592025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang M and Ma C: LSR promotes cell

proliferation and invasion in lung cancer. Comput Math Methods Med.

2021:66519072021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:7–33.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pallis AG and Syrigos KN: Lung cancer in

never smokers: Disease characteristics and risk factors. Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 88:494–503. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jones GS and Baldwin DR: Recent advances

in the management of lung cancer. Clin Med (Lond). 18 (Suppl

2):S41–S46. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lim RB: End-of-life care in patients with

advanced lung cancer. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 10:455–467. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Koh YC, Ho CT and Pan MH: Recent advances

in cancer chemoprevention with phytochemicals. J Food Drug Anal.

28:14–37. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bade BC and Dela Cruz CS: Lung cancer

2020: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med.

41:1–24. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Similie D, Minda D, Bora L, Kroškins V,

Lugiņina J, Turks M, Dehelean CA and Danciu C: An update on

pentacyclic triterpenoids ursolic and oleanolic acids and related

derivatives as anticancer candidates. Antioxidants (Basel).

13:9522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pironi AM, de Araújo PR, Fernandes MA,

Salgado HRN and Chorilli M: Characteristics, biological properties

and analytical methods of ursolic acid: A review. Crit Rev Anal

Chem. 48:86–93. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mlala S, Oyedeji AO, Gondwe M and Oyedeji

OO: Ursolic acid and its derivatives as bioactive agents.

Molecules. 24:27512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kashyap D, Sharma A, Tuli HS, Punia S and

Sharma AK: Ursolic acid and oleanolic acid: Pentacyclic terpenoids

with promising Anti-inflammatory activities. Recent Pat Inflamm

Allergy Drug Discov. 10:21–33. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liobikas J, Majiene D, Trumbeckaite S,

Kursvietiene L, Masteikova R, Kopustinskiene DM, Savickas A and

Bernatoniene J: Uncoupling and antioxidant effects of ursolic acid

in isolated rat heart mitochondria. J Nat Prod. 74:1640–1644. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jayaprakasam B, Olson LK, Schutzki RE, Tai

MH and Nair MG: Amelioration of obesity and glucose intolerance in

high-fat-fed C57BL/6 mice by anthocyanins and ursolic acid in

Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas). J Agric Food Chem. 54:243–248. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yu SG, Zhang CJ, Xu XE, Sun JH, Zhang L

and Yu PF: Ursolic acid derivative ameliorates

Streptozotocin-induced diabestic bone deleterious effects in mice.

Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 8:3681–3690. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sundaresan A, Radhiga T and Pugalendi KV:

Effect of ursolic acid and Rosiglitazone combination on hepatic

lipid accumulation in high fat diet-fed C57BL/6J mice. Eur J

Pharmacol. 741:297–303. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Erdmann J, Kujaciński M and Wiciński M:

Beneficial effects of ursolic acid and its derivatives-focus on

potential biochemical mechanisms in cardiovascular conditions.

Nutrients. 13:39002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Shi Y, Leng Y, Liu D, Liu X, Ren Y, Zhang

J and Chen F: Research advances in protective effects of ursolic

acid and oleanolic acid against gastrointestinal diseases. Am J

Chin Med. 49:413–435. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen C, Ai Q, Shi A, Wang N, Wang L and

Wei Y: Oleanolic acid and ursolic acid: Therapeutic potential in

neurodegenerative diseases, neuropsychiatric diseases and other

brain disorders. Nutr Neurosci. 26:414–428. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sandhu SS, Rouz SK, Kumar S, Swamy N,

Deshmukh L, Hussain A, Haque S and Tuli HS: Ursolic acid: A

pentacyclic triterpenoid that exhibits anticancer therapeutic

potential by modulating multiple oncogenic targets. Biotechnol

Genet Eng Rev. 39:729–759. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Iqbal J, Abbasi BA, Ahmad R, Mahmood T,

Kanwal S, Ali B, Khalil AT, Shah SA, Alam MM and Badshahet H:

Ursolic acid a promising candidate in the therapeutics of breast

cancer: Current status and future implications. Biomed

Pharmacother. 108:752–756. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lin JH, Xu JJ, Liu XF, Liu WH, Wang YF, Li

ZS, Wang LW and Wang W: Ursolic acid promotes apoptosis, autophagy,

and chemosensitivity in gemcitabine-resistant human pancreatic

cancer cells. Phytother Res. 34:2053–2066. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Meng Y, Lin ZM, Ge N, Zhang DL, Huang J

and Kong F: Ursolic acid induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells

via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Am J Chin Med. 43:1471–1486. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang H, Zhang X, Ma X and Wang X: Ursolic

acid in colorectal cancer: Mechanisms, current status, challenges,

and future research directions. Pharmacol Rep. 77:72–86. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Guo JL, Han T, Bao L, Li XM, Ma JQ and

Tang LP: Ursolic acid promotes the apoptosis of cervical cancer

cells by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Obstet Gynaecol

Res. 45:877–881. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cai C, Zhi Y, Xie C, Geng S, Sun F, Ji Z,

Zhang P, Wang H and Tang J: Ursolic acid-downregulated long

noncoding RNA ASMTL-AS1 inhibits renal cell carcinoma growth via

binding to HuR and reducing vascular endothelial growth factor

expression. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 37:e233892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Namdeo P, Gidwani B, Tiwari S, Jain V,

Joshi V, Shukla SS, Pandey RK and Vyas A: Therapeutic potential and

novel formulations of ursolic acid and its derivatives: An updated

review. J Sci Food Agric. 103:4275–4292. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ma X, Bai Y, Liu K, Han Y, Zhang J, Liu Y,

Hou X, Hao E, Hou Y and Bai G: Ursolic acid inhibits the

cholesterol biosynthesis and alleviates high fat Diet-induced

hypercholesterolemia via irreversible inhibition of HMGCS1 in vivo.

Phytomedicine. 103:1542332022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fernández-Hernández A, Martinez A, Rivas

F, García-Mesa JA and Parra A: Effect of the solvent and the sample

preparation on the determination of triterpene compounds in

two-phase olive-mill-waste samples. J Agric Food Chem.

63:4269–4275. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu J: Pharmacology of oleanolic acid and

ursolic acid. J Ethnopharmacol. 49:57–68. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ikeda Y, Murakami A and Ohigashi H:

Ursolic acid: An anti- and pro-inflammatory triterpenoid. Mol Nutr

Food Res. 52:26–42. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang X, Xiong W, Wang X, Qin L, Zhong M,

Liu Y, Xiong Y, Yi X, Wang X and Zhang H: Ursolic acid attenuates

cholestasis through NRF2-mediated regulation of UGT2B7 and

BSEP/MRP2. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 397:2257–2267.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Luan M, Wang H, Wang J, Zhang X, Zhao F,

Liu Z and Meng Q: Advances in Anti-inflammatory activity, mechanism

and therapeutic application of ursolic acid. Mini Rev Med Chem.

22:422–436. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Shanmugam MK, Dai X, Kumar AP, Tan BK,

Sethi G and Bishayee A: Ursolic acid in cancer prevention and

treatment: Molecular targets, pharmacokinetics and clinical

studies. Biochem Pharmacol. 85:1579–1587. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Khwaza V, Oyedeji OO and Aderibigbe BA:

Ursolic Acid-based derivatives as potential anti-cancer agents: An

update. Int J Mol Sci. 21:59202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kang DY, Sp N, Jang KJ, Jo ES, Bae SW and

Yang YM: Antitumor effects of natural bioactive ursolic acid in

embryonic cancer stem cells. J Oncol. 2022:67372482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wang S, Chang X, Zhang J, Li J, Wang N,

Yang B, Pan B, Zheng Y, Wang X, Ou H and Wang Z: Ursolic acid

inhibits breast cancer metastasis by suppressing glycolytic

metabolism via activating SP1/Caveolin-1 signaling. Front Oncol.

11:7455842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Panda SS, Thangaraju M and Lokeshwar BL:

Ursolic acid analogs as potential therapeutics for cancer.

Molecules. 27:89812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang N, Liu S, Shi S, Chen Y, Xu F, Wei X

and Xu Y: Solubilization and delivery of Ursolic-acid for

modulating tumor microenvironment and regulatory T cell activities

in cancer immunotherapy. J Control Release. 320:168–178. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen H, Gao Y, Wang A, Zhou X, Zheng Y and

Zhou J: Evolution in medicinal chemistry of ursolic acid

derivatives as anticancer agents. Eur J Med Chem. 92:648–655. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Jiang H, Wei JH, Lin CY, Liang GB, He RJ,

Huang RZ, Ma XL, Huang GB and Zhang Y: Ursolic

acid-piperazine-dithiocarbamate ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes

induced necroptosis in MGC-803 cells. Metallomics. 14:mfac0722022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Kim JH, Kim YH, Song GY, Kim DE, Jeong YJ,

Liu KH, Chung YH and Oh S: Ursolic acid and its natural derivative

corosolic acid suppress the proliferation of APC-mutated colon

cancer cells through promotion of beta-catenin degradation. Food

Chem Toxicol. 67:87–95. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Gou W, Luo N, Wei H, Wu H, Yu X, Duan Y,

Bi C, Ning H, Hou W and Li Y: Ursolic acid derivative UA232 evokes

apoptosis of lung cancer cells induced by endoplasmic reticulum

stress. Pharm Biol. 58:707–715. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sun L, Li B, Su X, Chen G, Li Y, Yu L, Li

L and Wei W: An ursolic acid derived small molecule triggers cancer

cell death through hyperstimulation of macropinocytosis. J Med

Chem. 60:6638–6648. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liu X, Qi M, Li X, Wang J and Wang M:

Curcumin: A natural organic component that plays a Multi-faceted

role in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 16:472023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Nedopekina DA, Gubaidullin RR, Odinokov

VN, Maximchik PV, Zhivotovsky B, Bel'skii YP, Khazanov VA,

Manuylova AV, Gogvadze V and Spivak AY: Mitochondria-targeted

betulinic and ursolic acid derivatives: Synthesis and anticancer

activity. Medchemcomm. 8:1934–1945. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Way TD, Tsai SJ, Wang CM, Ho CT and Chou

CH: Chemical constituents of Rhododendron formosanum show

pronounced growth inhibitory effect on non-small-cell lung

carcinoma cells. J Agric Food Chem. 62:875–884. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Abdel-Hamid NM and Abass SA: Matrix

metalloproteinase contribution in management of cancer

proliferation, metastasis and drug targeting. Mol Biol Rep.

48:6525–6538. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lai MY, Leung HW, Yang WH, Chen WH and Lee

HZ: Up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase family gene

involvement in ursolic acid-induced human lung non-small carcinoma

cell apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 27:145–153. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kang DY, Sp N, Lee JM and Jang KJ:

Antitumor effects of ursolic acid through mediating the inhibition

of STAT3/PD-L1 signaling in Non-small cell lung cancer cells.

Biomedicines. 9:2972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Nunnari J and Suomalainen A: Mitochondria:

In sickness and in health. Cell. 148:1145–1159. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chen CJ, Shih YL, Yeh MY, Liao NC, Chung

HY, Liu KL, Lee MH, Chou PY, Hou HY, Chou JS and Chung JG: Ursolic

acid induces apoptotic cell death through AIF and endo G release

through a Mitochondria-dependent pathway in NCI-H292 human lung

cancer cells in vitro. In Vivo. 33:383–391. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ma T, Zhou J, Li J and Chen Q: Hyaluronic

Acid-modified liposomes for ursolic Acid-targeted delivery treat

lung cancer based on p53/ARTS-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis.

Iran J Pharm Res. 22:e1317582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Castrejón-Jiménez NS, Leyva-Paredes K,

Baltierra-Uribe SL, Castillo-Cruz J, Campillo-Navarro M,

Hernández-Pérez AD, Luna-Angulo AB, Chacón-Salinas R, Coral-Vázquez

RM, Estrada-García I, et al: Ursolic and oleanolic acids induce

mitophagy in A549 human lung cancer cells. Molecules. 24:34441019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Song B, Zhang Q, Yu M, Qi X, Wang G, Xiao

L, Yi Q and Jin W: Ursolic acid sensitizes radioresistant NSCLC

cells expressing HIF-1α through reducing endogenous GSH and

inhibiting HIF-1α. Oncol Lett. 13:754–762. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Smith G, Alholm Z, Coleman RL and Monk BJ:

DNA damage repair Inhibitors-combination therapies. Cancer J.

27:501–505. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Wang JY: DNA damage and apoptosis. Cell

Death Differ. 8:1047–1048. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Kaina B: DNA damage-triggered apoptosis:

Critical role of DNA repair, double-strand breaks, cell

proliferation and signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 66:1547–1554. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Campillo-Marcos I, García-González R,

Navarro-Carrasco E and Lazo PA: The human VRK1 chromatin kinase in

cancer biology. Cancer Lett. 503:117–128. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Kim SH, Ryu HG, Lee J, Shin J, Harikishore

A, Jung HY, Kim YS, Lyu HN, Oh E, Baek NI, et al: Ursolic acid

exerts anti-cancer activity by suppressing Vaccinia-related kinase

1-mediated damage repair in lung cancer cells. Sci Rep.

5:145702015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Han T, Kang D, Ji D, Wang X, Zhan W, Fu M,

Xin HB and Wang JB: How does cancer cell metabolism affect tumor

migration and invasion? Cell Adh Migr. 7:395–403. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Affara NI, Andreu P and Coussens LM:

Delineating protease functions during cancer development. Methods

Mol Biol. 539:1–32. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Liu J: Oleanolic acid and ursolic acid:

Research perspectives. J Ethnopharmacol. 100:92–94. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Xu F, Li M, Que Z, Su M, Yao W, Zhang Y,

Luo B, Li Y, Zhang Z and Tian J: Combined chemo-immuno-photothermal

therapy based on ursolic acid/astragaloside IV-loaded hyaluronic

acid-modified polydopamine nanomedicine inhibiting the growth and

metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Mater Chem B.

11:3453–3472. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Huang CY, Lin CY, Tsai CW and Yin MC:

Inhibition of cell proliferation, invasion and migration by ursolic

acid in human lung cancer cell lines. Toxicol In Vitro.

25:1274–1280. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Lamouille S, Xu J and Derynck R: Molecular

mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 15:178–196. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ruan JS, Zhou H, Yang L, Wang L, Jiang ZS,

Sun H and Wang SM: Ursolic acid attenuates TGF-β1-induced

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in NSCLC by targeting integrin

αVβ5/MMPs signaling. Oncol Res. 27:593–600. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Liu K, Guo L, Miao L, Bao W, Yang J, Li X,

Xi T and Zhao W: Ursolic acid inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal

transition by suppressing the expression of astrocyte-elevated

gene-1 in human nonsmall cell lung cancer A549 cells. Anticancer

Drugs. 24:494–503. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jesudason EC, Connell MG, Fernig DG, Lloyd

DA and Losty PD: Cell proliferation and apoptosis in experimental

lung hypoplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 35:129–133. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Yang K, Chen Y, Zhou J, Ma L, Shan Y,

Cheng X, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Ji X, Chen L, et al: Ursolic acid

promotes apoptosis and mediates transcriptional suppression of

CT45A2 gene expression in non-small-cell lung carcinoma harbouring

EGFR T790M mutations. Br J Pharmacol. 176:4609–4624. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Changotra H, Kaur S, Yadav SS, Gupta GL,

Parkash J and Duseja A: ATG5: A central autophagy regulator

implicated in various human diseases. Cell Biochem Funct.

40:650–667. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Baeva ME and Camara-Lemarroy C: The role

of autophagy protein Atg5 in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat

Disord. 79:1050292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wang M, Yu H, Wu R, Chen ZY, Hu Q, Zhang

YF, Gao SH and Zhou GB: Autophagy inhibition enhances the

inhibitory effects of ursolic acid on lung cancer cells. Int J Mol

Med. 46:1816–1826. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wu J, Zhao S, Tang Q, Zheng F, Chen Y,

Yang L, Yang X, Li L, Wu W and Hann SS: Activation of SAPK/JNK

mediated the inhibition and reciprocal interaction of DNA

methyltransferase 1 and EZH2 by ursolic acid in human lung cancer

cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 34:992015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Higgins MJ and Ettinger DS: Chemotherapy

for lung cancer: The state of the art in 2009. Expert Rev

Anticancer Ther. 9:1365–1378. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Souhami RL: Defining the role of

chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 6:317–318.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Wu T, Yan D, Hou W, Jiang H, Wu M, Wang Y,

Chen G, Tang C, Wang Y and Xu H: Biomimetic red blood cell

membrane-Mediated nanodrugs loading ursolic acid for targeting

NSCLC therapy. Cancers (Basel). 14:45202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Shen M, Xu Z, Xu W, Jiang K, Zhang F, Ding

Q, Xu Z and Chen Y: Inhibition of ATM reverses EMT and decreases

metastatic potential of cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cells

through JAK/STAT3/PD-L1 pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:1492019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Fan L, Wang X, Cheng C, Wang S, Li X, Cui

J, Zhang B and Shi L: Inhibitory effect and mechanism of ursolic

acid on Cisplatin-induced resistance and stemness in human lung

cancer A549 cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2023:13073232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Li S, Guo X, Liu H, Chen Y, Wan H, Kang X,

Qin J and Guo S: Ursolic acid, an inhibitor of TMEM16A, co-loaded

with cisplatin in hydrogel drug delivery system for multi-targeted

therapy of lung cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 277:1345872024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Chen Q, Luo J, Wu C, Lu H, Cai S, Bao C,

Liu D and Kong J: The miRNA-149-5p/MyD88 axis is responsible for

ursolic Acid-mediated attenuation of the stemness and

chemoresistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Environ

Toxicol. 35:561–569. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Pérez-Herrero E and Fernández-Medarde A:

Advanced targeted therapies in cancer: Drug nanocarriers, the

future of chemotherapy. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 93:52–79. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Fu S, Li G, Zang W, Zhou X, Shi K and Zhai

Y: Pure drug Nano-assemblies: A facile carrier-free nanoplatform

for efficient cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 12:92–106. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Jinhua W: Ursolic acid: Pharmacokinetics

process in vitro and in vivo, a mini review. Arch Pharm (Weinheim).

352:e18002222019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Antonio E, Dos Reis Antunes Junior O,

Marcano RGDJV, Diedrich C, da Silva Santos J, Machado CS, Khalil NM

and Mainardes RM: Chitosan modified poly (lactic acid)

nanoparticles increased the ursolic acid oral bioavailability. Int

J Biol Macromol. 172:133–142. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Yang L, Sun Z, Zu Y, Zhao C, Sun X, Zhang

Z and Zhang L: Physicochemical properties and oral bioavailability

of ursolic acid nanoparticles using supercritical anti-solvent

(SAS) process. Food Chem. 132:319–325. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Yu D, Kan Z, Shan F, Zang J and Zhou J:

Triple strategies to improve oral bioavailability by fabricating

coamorphous forms of ursolic acid with piperine: Enhancing

Water-solubility, permeability, and inhibiting cytochrome P450

isozymes. Mol Pharm. 17:4443–4462. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Chen Q, Luo S, Zhang Y and Chen Z:

Development of a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method for

the determination of ursolic acid in rat plasma and tissue:

Application to the pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution study.

Anal Bioanal Chem. 399:2877–2884. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Wang M, Zhao T, Liu Y, Wang Q, Xing S, Li

L, Wang L, Liu L and Gao D: Ursolic acid liposomes with chitosan

modification: Promising antitumor drug delivery and efficacy. Mater

Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 71:1231–1240. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Lei P, Li Z, Hua Q, Song P, Gao L, Zhou L

and Cai Q: Ursolic acid alleviates neuroinflammation after

intracerebral hemorrhage by mediating microglial pyroptosis via the

NF-κB/NLRP3/GSDMD pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 24:147712023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Sun K, Wu H, Zhu Q, Gu K, Wei H, Wang S,

Li L, Wu C, Chen R, Pang Y, et al: Global landscape and trends in

lifetime risks of haematologic malignancies in 185 countries:

Population-based estimates from GLOBOCAN 2022. EClinicalMedicine.

83:1031932025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Wu BY and Parks LM: Chemical studies on

ursolic acid. J Am Pharm Assoc Am Pharm Assoc. 42:603–606. 1953.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Ram Kumar Pandian S, Kunjiappan S, Pavadai

P, Sundarapandian V, Chandramohan V and Sundar K: Delivery of

ursolic acid by polyhydroxybutyrate nanoparticles for cancer

therapy: In silico and in vitro studies. Drug Res (Stuttg).

72:72–81. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Sharma R, Yadav V, Jha S, Dighe S and Jain

S: Unveiling the potential of ursolic acid modified hyaluronate

nanoparticles for combination drug therapy in triple negative

breast cancer. Carbohydr Polym. 338:1221962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

O'Malley M, King AN, Conte M, Ellingrod VL

and Ramnath N: Effects of cigarette smoking on metabolism and

effectiveness of systemic therapy for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol.

9:917–926. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Zevin S and Benowitz NL: Drug interactions

with tobacco smoking. An update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 36:425–438.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|