Introduction

According to the International Agency for Cancer

Research, the incidence of colorectal cancer has been steadily

increasing over the past two decades (1). In 2020, colorectal cancer ranked as

the third most common cancer among men and the second most common

among women, with its mortality rate ranking second among all

malignancies (2,3).

5′-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is a key chemotherapeutic

agent that has been used to treat colorectal cancer, exerting its

effects primarily through inhibiting thymidylate synthase (TS);

this inhibition subsequently disrupts RNA and DNA synthesis,

thereby suppressing tumor cell proliferation (4). Although 5-FU has demonstrated

significant efficacy against various types of solid tumor,

especially those of the gastrointestinal tract, its therapeutic

success in advanced colorectal cancer has been shown to be limited,

with response rates of 10–15% (5).

The emergence of 5-FU resistance substantially diminishes its

clinical effectiveness, posing a major challenge in the management

of colorectal cancer; therefore, strategies to enhance the

sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells to 5-FU, and to mitigate

chemotherapy resistance, remain urgent priorities for improving

patient outcomes.

Loperamide (LOP) is a United States Food and Drug

Administration-approved antidiarrheal medicine (6) with a well-established safety profile,

which has been shown to induce autophagy and reverse multidrug

resistance (MDR) in several types of cancer, including glioblastoma

and breast cancer (7,8). The safety profile of LOP, combined

with its efficacy at therapeutic dose (2–8 mg/day) makes it a

promising candidate for drug repurposing in oncology. Its potential

to overcome 5-FU resistance in colorectal cancer is supported by

its ability to modulate cellular stress pathways and enhance

chemosensitivity. These effects have been shown to be mediated

through the induction of autophagy and the downregulation of MDR1

gene expression (7–9). However, despite these promising

findings, the impact of LOP on colorectal cancer, in particular its

potential to overcome 5-FU resistance and the associated underlying

molecular mechanisms, remains poorly understood.

Autophagy is a highly regulated cellular process in

which eukaryotic cells utilize lysosomes to degrade cytoplasmic

proteins and damaged organelles, and it can be characterized into

basal physiological autophagy and stress-induced autophagy

(9). Basal autophagy serves as a

protective mechanism, maintaining cellular homeostasis and

protecting cells from stress or oxidative damage induced by

external stimuli, whereas excessive autophagy can lead to metabolic

stress, extensive degradation of essential cellular components,

and, ultimately, cell death.

In the context of colorectal cancer drug resistance,

numerous studies have suggested that autophagy serves a critical

role in enhancing resistance to various chemotherapeutic agents

(10,11). Consequently, targeting autophagy

represents a potential strategy for modulating the sensitivity of

gastrointestinal tumors to 5-FU treatment.

In the present study, the 5-FU-sensitive colorectal

cancer cell line HCT8 and its 5-FU-resistant counterpart, HCT8R,

were employed in a series of in vitro and in vivo

experiments. The current study investigated whether LOP potentiates

5-FU sensitivity in colorectal cancer cells and elucidated the

underlying molecular mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The human colorectal cancer cell line HCT8 (cat. no.

1101HUM-PUMC000104; Cell Resource Center, Institute of Basic

Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking

Union Medical College) and its 5-FU-resistant derivative, HCT8R

(cat. no. MXC149; ShangHai MEIXUAN Biological Science and

Technology Ltd.), were kindly provided by the research group of

Professor Xi (Hubei University of Medicine, Shiyan, China). Both

cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml

streptomycin. Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at

37°C containing 5% CO2 to support optimal cell growth.

To inhibit autophagic activity, the HCT8R cells were co-incubated

with an autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine (3-MA; 5 mM), 5-FU (20

µg/ml) and LOP (20 µM) for 24 h at 37°C.

RPMI-1640 medium was purchased as a powder from

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., FBS was obtained from

Zhejiang Tianhang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., the antibiotics were

sourced from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, and LOP, 5-FU and

3-MA were purchased from MedChemExpress.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) viability

assay

HCT8 and HCT8R cell metabolic activity was assessed

using the CCK-8 kit (cat. no. C0038; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly,

cells in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded at

1×103 cells/well in 96-well plates (100 µl/well). After

24 h of adhesion, the medium was replaced with fresh medium

containing 5-FU (0, 10, 20, 40 and 80 µg/ml) and LOP (0, 10, 20, 40

and 80 µM). To evaluate the combined effects of 5-FU and LOP on

cell viability, HCT8R cells were treated with 5-FU (20 µg/ml),

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 0.2% v/v) or LOP (10 and 20 µM). The

cells were then incubated for 24 h, followed by the addition of 10

µl CCK-8 reagent/well and further incubation for 2 h at 37°C.

Culture medium without cells served as the blank control.

Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek

Synergy H1; Biotek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)

proliferation assay

Exponentially growing HCT8R cells were counted and

seeded into 48-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells/well. After

24 h of adherence to the plates, the cells were treated with 5-FU

(20 µg/ml), DMSO (0.2% v/v) or LOP (20 µM) for 48 h at 37°C. To

assess cell proliferation, the cells were incubated with EdU

diluted in culture medium at a 100:1 ratio (200 µl/well) for 6 h at

37°C. Following EdU labeling, the medium was subsequently removed

and the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Biosharp Life

Sciences) for 30 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were then

incubated with 2 mg/ml glycine for 5 min to neutralize residual

paraformaldehyde, followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton

X-100 for 20 min at room temperature. The EdU reaction solution was

prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) and applied to the cells (100 µl/well)

for 30 min in the dark to ensure precise labeling at room

temperature. Subsequently, the cells were counterstained with DAPI

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 10 min to visualize the

nuclei at room temperature. Finally, fluorescent images were

acquired using an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Colony formation assay

Exponentially growing HCT8R cells were seeded into

6-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells/well. Once the cells had

formed small colonies, they were treated with 5-FU (20 µg/ml), DMSO

(0.2% v/v) or LOP (20 µM) for 48 h at 37°C. After 6–8 days, colony

formation was assessed under a microscope. When distinct colonies

were visible in the control group, the culture medium was aspirated

and the cells were washed three times with PBS. Cells were

subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room

temperature, and colonies were then stained with crystal violet for

30 min at room temperature to enhance visualization. Excess stain

was removed with multiple PBS washes and the plates were left to

air-dry prior to imaging. Crystal violet-stained colonies (>50

cells) were visualized using an inverted light microscope (IX71;

Olympus Corporation). Colony counts per group were manually

quantified in triplicate and averaged.

Wound healing assay

Exponentially growing HCT8R cells were treated with

trypsin until they formed a single-cell suspension, and

~5×105 cells/well were seeded into 6-well plates. The

cells were subsequently cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere

containing 5% CO2 for 24 h to allow them to reach 100%

confluence. A uniform scratch was introduced using a 200-µl pipette

tip and the cells were subsequently washed three times with PBS to

remove any detached cells. Fresh RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with

2% FBS was then added to each well. Initial images were captured to

confirm that the scratch that had been made was uniform, centered

and perpendicular to the plane of the plate. Following treatment

with 5-FU (20 µg/ml), DMSO (0.2% v/v) or LOP (20 µM) for 24 h at

37°C, additional images were acquired under a light microscope.

Cell migration into the scratch area was quantified using ImageJ

(version 4.1; National Institutes of Health), and the wound healing

rate was calculated as: (0 h scratch width −24 h scratch width)/0 h

scratch width ×100 to assess cell motility.

Transwell assay

For the Transwell assay experiments in HCT8 and

HCT8R cells, 600 µl RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% FBS was

added to the lower chamber, with or without 3-MA (5 mM), 5-FU (20

µg/ml) and LOP (10 and 20 µM). Subsequently, 200 µl suspension

containing 105 cells/ml in FBS-free medium was added to

the upper chamber (pore size, 8 µm; Corning, Inc.), which was

placed into a 24-well plate. The cells were cultured for 48 h to

allow for migration. After the incubation period, the insert was

carefully removed and washed once with PBS. The cells that had

migrated to the lower surface of the insert were subsequently fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and washed

three times with PBS. The interior of the insert was gently swabbed

with a soft cotton swab to remove non-adherent cells. Finally,

staining was performed using crystal violet for 20 min at room

temperature, and excess stain was removed by multiple washes with

PBS. Images were captured under a light microscope.

Observation of autophagosomes by

confocal microscopy

Exponentially growing HCT8R cells were plated in

6-well plates, and cultured for 24 h until they reached 70–80%

confluence. Transfection was subsequently performed using

Lipo8000™ reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

in combination with 2 µg pEGFP (cat. no. 165830; Addgene, Inc.) or

pEGFP-microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) plasmid

(cat. no. 24920; Addgene, Inc.) and Opti-MEM™ serum-free

medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). After 36 h of

transfection at 37°C, the cells were subsequently transferred to

confocal dishes, and allowed to continue growing for an additional

24 h. Once cells had reached ~50% confluence, they were incubated

with either 5-FU (20 µg/ml), DMSO (0.2% v/v) or LOP (20 µM) for 24

h at 37°C. Imaging was performed using an Olympus FV3000RS

super-resolution laser confocal microscope (Olympus Corporation).

All samples were analyzed under identical imaging conditions to

ensure consistency and reproducibility.

Western blot analysis

HCT8R cells were harvested into 1.5-ml Eppendorf

tubes containing RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for protein extraction at 4°C. The protein

concentration was subsequently quantified using a bicinchoninic

acid protein assay kit, and 20 µg protein samples were separated by

SDS-PAGE on 12% gels and transferred to a PVDF membrane

(MilliporeSigma). Non-specific binding was blocked using PBS

containing 5% nonfat milk for 2 h at room temperature. The membrane

was subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies

(diluted with PBS) raised against LC3 (1:1,000; cat. no.

18725-1-AP), Beclin (1:1,000; cat. no. 11306-1-AP) (both from

Proteintech Group, Inc.) and β-actin (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-47778;

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Following incubation with the

primary antibodies, the membrane was washed and incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (diluted with PBS,

1:5,000; cat. no. 31460; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and anti-mouse secondary antibodies (diluted with PBS,

1:5,000; cat. no. 31430; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the blots were

visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Images were semi-quantified using

ImageJ (version 4.1; National Institutes of Health).

Apoptosis detection

For apoptosis detection, the HCT8R cells were seeded

in 6-well plates at a density of 4×105 cells/well. Cells

were treated with 5-FU (20 µg/ml) and LOP (10 or 20 µM) for 48 h at

37°C. Both adherent and floating cells were then harvested and

washed with ice-cold PBS. Cells from different experimental groups

were then digested with trypsin (without EDTA), combined with the

culture supernatant and centrifuged at 112 × g for 4 min at 4°C to

pellet the cells. Subsequently, the pellet was gently resuspended

in pre-chilled binding buffer and adjusted to a concentration of

1–5×106 cells/ml. Aliquots of the cell suspension (100

µl) were then mixed with 5 µl FITC-Annexin V and 5 µl PI, gently

mixed, and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 8–10 min.

Subsequently, 400 µl binding buffer was added, and the mixture was

gently mixed on a vortex mixer. Finally, apoptosis was assessed

using a flow cytometer (SA3800; Sony Biotechnology Inc.) within 1

h, with an Annexin V-PI reagent kit purchased from Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

Xenograft tumor study in nude

mice

HCT8R cells (5×106 cells/100 µl PBS) were

subcutaneously injected into the lateral abdominal region of female

nude BALB/c mice (age, 4 weeks; weight, 20–24 g; n=3/group; total

n=9) that were housed under the following specific pathogen-free

conditions: Temperature, 23±1°C; humidity, 55±5%; 12-h light/dark

cycle, and with free access to standard chow and drinking water.

The mice were randomly divided into the control (vehicle: 0.9% NaCl

+ 0.1% DMSO, i.p. daily), 5-FU monotherapy (25 mg/kg i.p., three

times per week) and combination (5-FU as above + LOP 2 mg/kg/day

i.p., three times per week) groups. All procedures followed

protocols approved by the Hubei University of Medicine Animal

Research Committee (approval no. 2023-034). Treatment was initiated

at day 7 post-inoculation when tumors reached 100±10 mm3

and continued for 21 days. The humane endpoints requiring

euthanasia included ≥20% body weight loss within 48 h, tumor

diameter >1.5 cm, impaired mobility or signs of distress

(labored breathing/vocalization). Animal health and behavior were

assessed twice daily (8:00 a.m./6:00 p.m.) using validated scoring

sheets, and tumor volume (V=LxW2/2) and weight were

measured every 48 h, with the endpoint being day 28 or when tumor

volume exceeded 1,500 mm3. Welfare provisions included:

Individual ventilated cages with environmental enrichment (paper

tunnels, chew blocks), and euthanasia by cervical dislocation under

deep anesthesia (5% isoflurane for induction and 2% for

maintenance). Death was verified by the cessation of respiration,

an absent heartbeat, fixed dilated pupils and bilateral

diaphragmatic transection. All 9 mice were sacrificed, with no

unexpected deaths recorded and no mice excluded from the

analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism 9 (Dotmatics). Comparisons between two groups were made using

unpaired Student's t-test, whereas comparisons among multiple

groups were performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc

test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

LOP enhances the sensitivity of

colorectal cancer cells to 5-FU

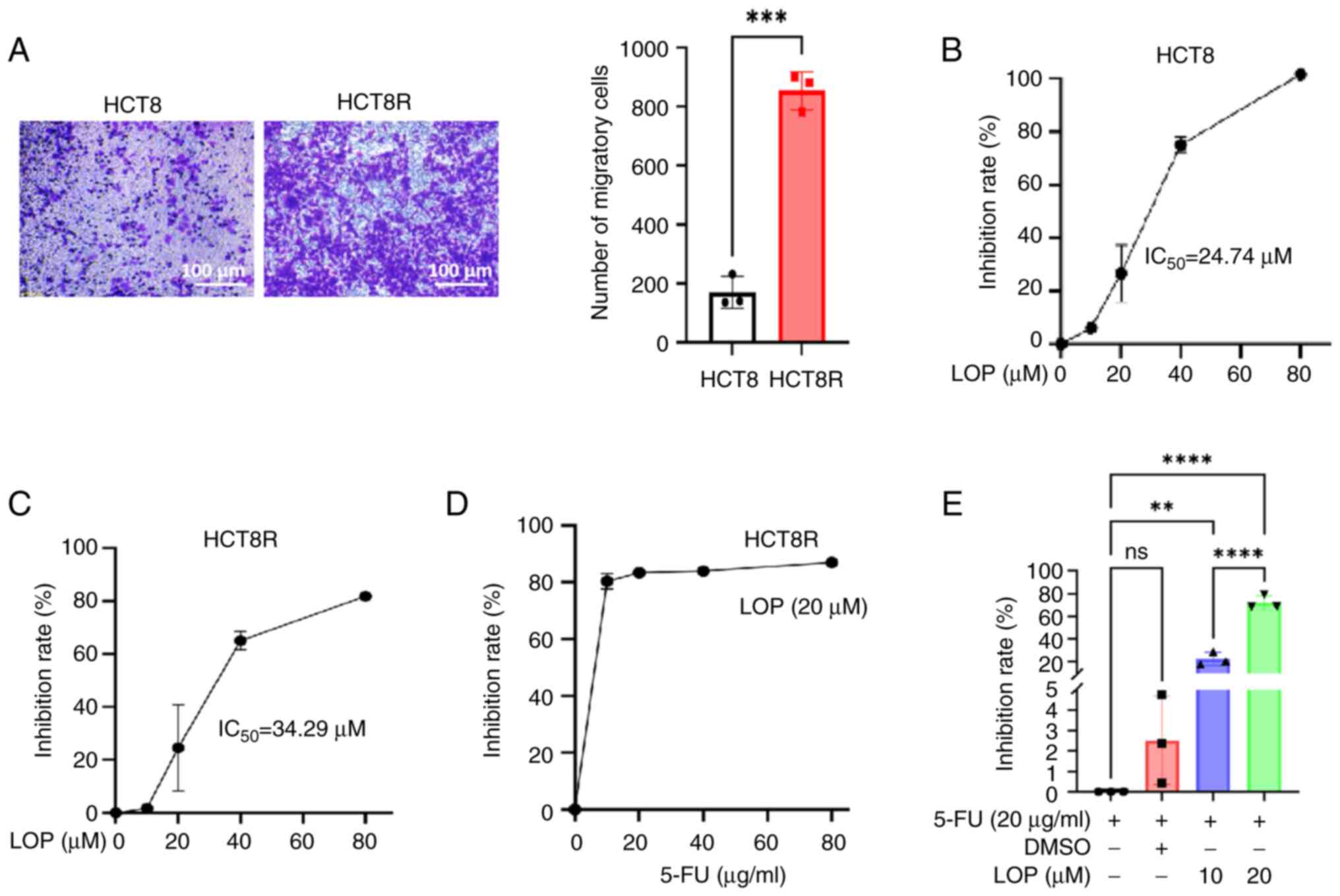

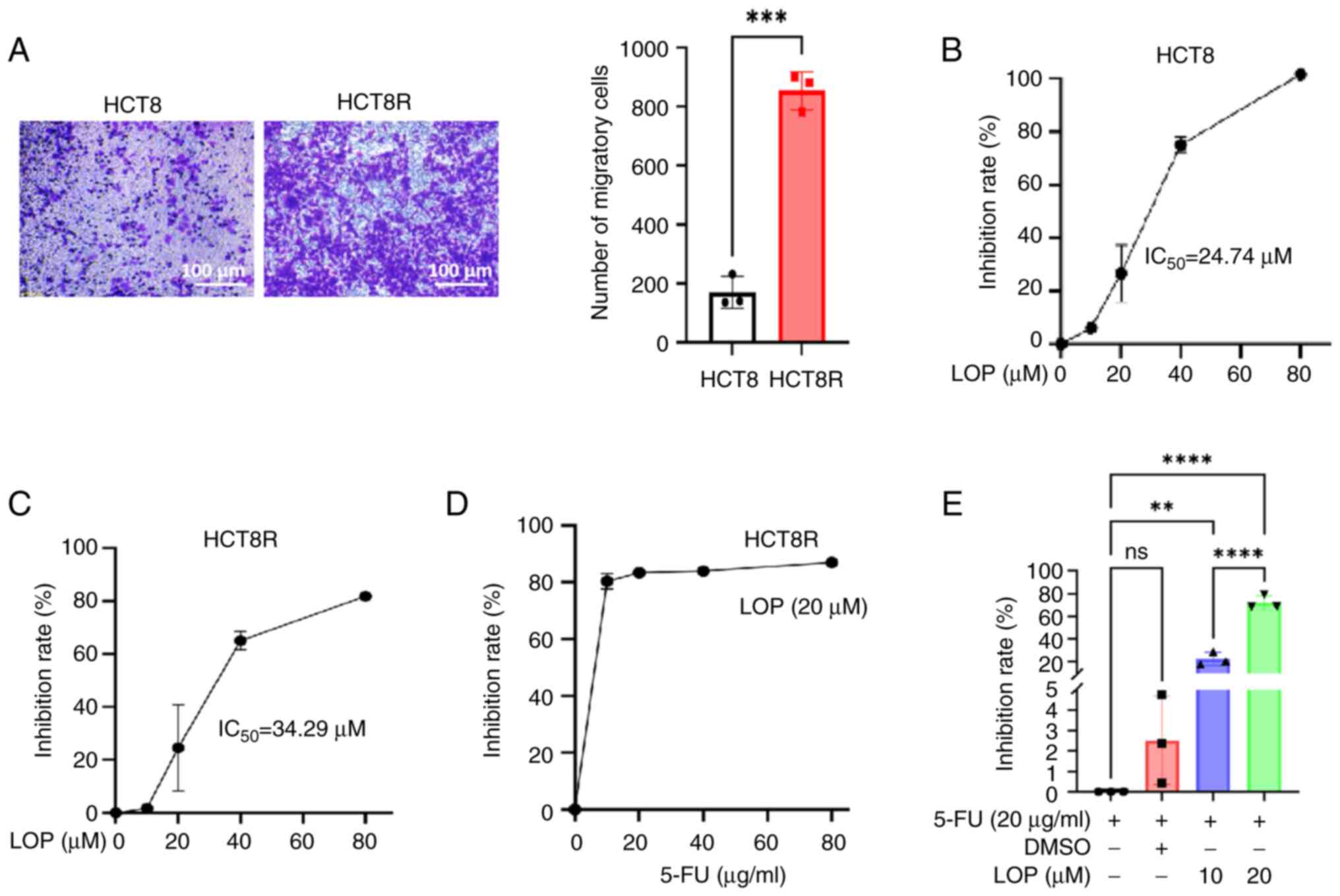

To evaluate the malignant potential of HCT8 and

HCT8R cells, Transwell assays were performed, which revealed that

the migratory capability of the drug-resistant HCT8R cells was

significantly higher compared with that of HCT8 cells (Fig. 1A). The preliminary dose-response

assessments revealed marked insensitivity of HCT8R cells to 5-FU

monotherapy, with conventional therapeutic concentrations (10–80

µg/ml) failing to induce significant inhibition of cell viability

(Fig. S1). Subsequently, the

inhibitory effects of LOP on cell viability were assessed using the

CCK-8 assay. The results demonstrated that LOP inhibited the

viability of both HCT8 and HCT8R cells, with IC50 values

of ~24.74 and 34.29 µM, respectively. These findings suggested that

LOP was able to effectively suppress the viability of both the

parental and 5-FU-resistant colorectal cancer cell lines (Fig. 1B and C).

| Figure 1.LOP enhances the sensitivity of

colorectal cancer cells to 5-FU. (A) Transwell assay was performed,

assessing the migratory capability of HCT8 and HCT8R cells. (B)

CCK-8 assay was performed, evaluating the inhibitory effect of LOP

on HCT8 cell proliferation. CCK-8 assay was performed to (C)

evaluate the inhibitory effect of LOP on HCT8R cell proliferation,

(D) examine the effects of LOP combined with various concentrations

of 5-FU on HCT8R cell proliferation, and (E) evaluate the effects

of 5-FU combined with different concentrations of LOP on HCT8R cell

proliferation. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 (n=3).

5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; DMSO, dimethyl

sulfoxide; LOP, loperamide; ns, not significant. |

To further examine the impact of LOP on the

sensitivity of HCT8R cells to 5-FU, additional CCK-8 assays were

performed. The results showed that the HCT8R cells exhibited

resistance to 5-FU, as increasing concentrations of the drug did

not significantly inhibit cell proliferation; however, treating the

cells with 20 µM LOP in addition to 5-FU led to a marked

enhancement of the inhibitory effect of 5-FU on cell proliferation

(Fig. 1D). Further analysis

revealed that treating the cells with 5-FU (20 µg/ml) alone did not

substantially alter HCT8R cell proliferation; by contrast, compared

with in the 5-FU group, the addition of LOP caused a significant

improvement in the sensitivity of these cells to 5-FU in a

concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

1E).

LOP enhances the 5-FU-induced

inhibition of HCT8R cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo

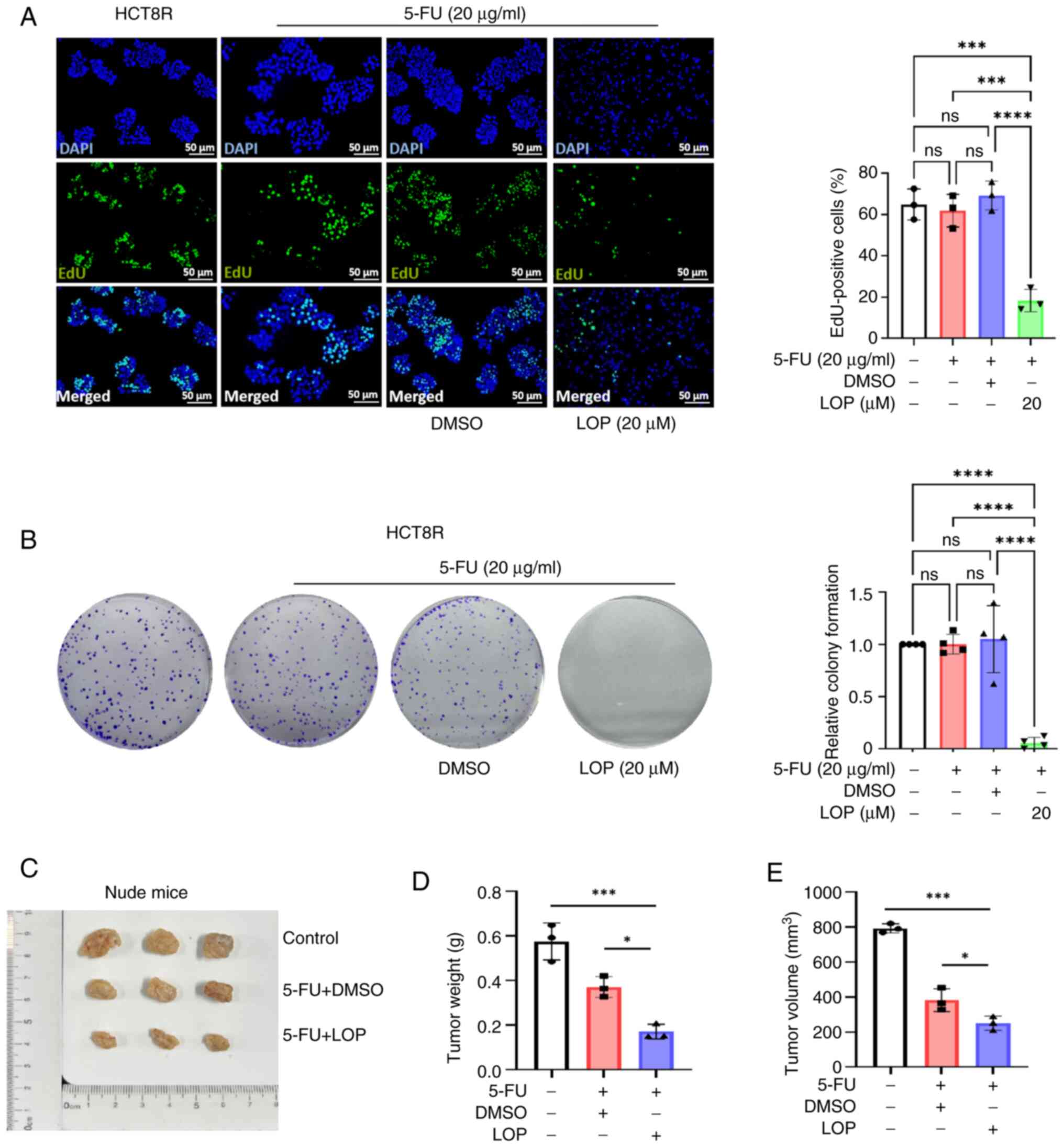

The EdU assay results demonstrated that the

proliferative activity of the HCT8R cells remained unaffected by

the addition of 5-FU or DMSO alone; however, treatment with LOP led

to a significant reduction in the number of proliferating HCT8R

cells (Fig. 2A). Colony formation

assays were subsequently performed, which further demonstrated that

treatment with LOP caused a marked decrease in the number of

colonies formed by HCT8R cells, whereas treatment with 5-FU alone

or DMSO did not lead to any significant inhibitory effects

(Fig. 2B).

To confirm the ability of LOP to enhance the

inhibitory effect of 5-FU on HCT8R cell proliferation in

vivo, a xenograft model was generated using nude mice. HCT8R

cells were implanted into nude mice, which were then randomly

divided into control, DMSO and LOP treatment groups. With the

exception of the control group, the other groups were injected

intraperitoneally with 5-FU (25 mg/kg per week, three times per

week), whereas the LOP treatment group was injected

intraperitoneally with LOP (2 mg/kg per day). The results

demonstrated that treatment with LOP led to a significant

enhancement of the inhibitory effect of 5-FU on tumor growth

(Fig. 2C), as evidenced by a marked

reduction in tumor weight and volume in the LOP treatment group

(Fig. 2D and E). Compared with in

the 5-FU group, the 5-FU and LOP co-treatment group demonstrated a

stronger tumor growth inhibitory effect. Collectively, these

findings suggested that LOP is able to effectively suppress cell

proliferation both in vitro and in vivo.

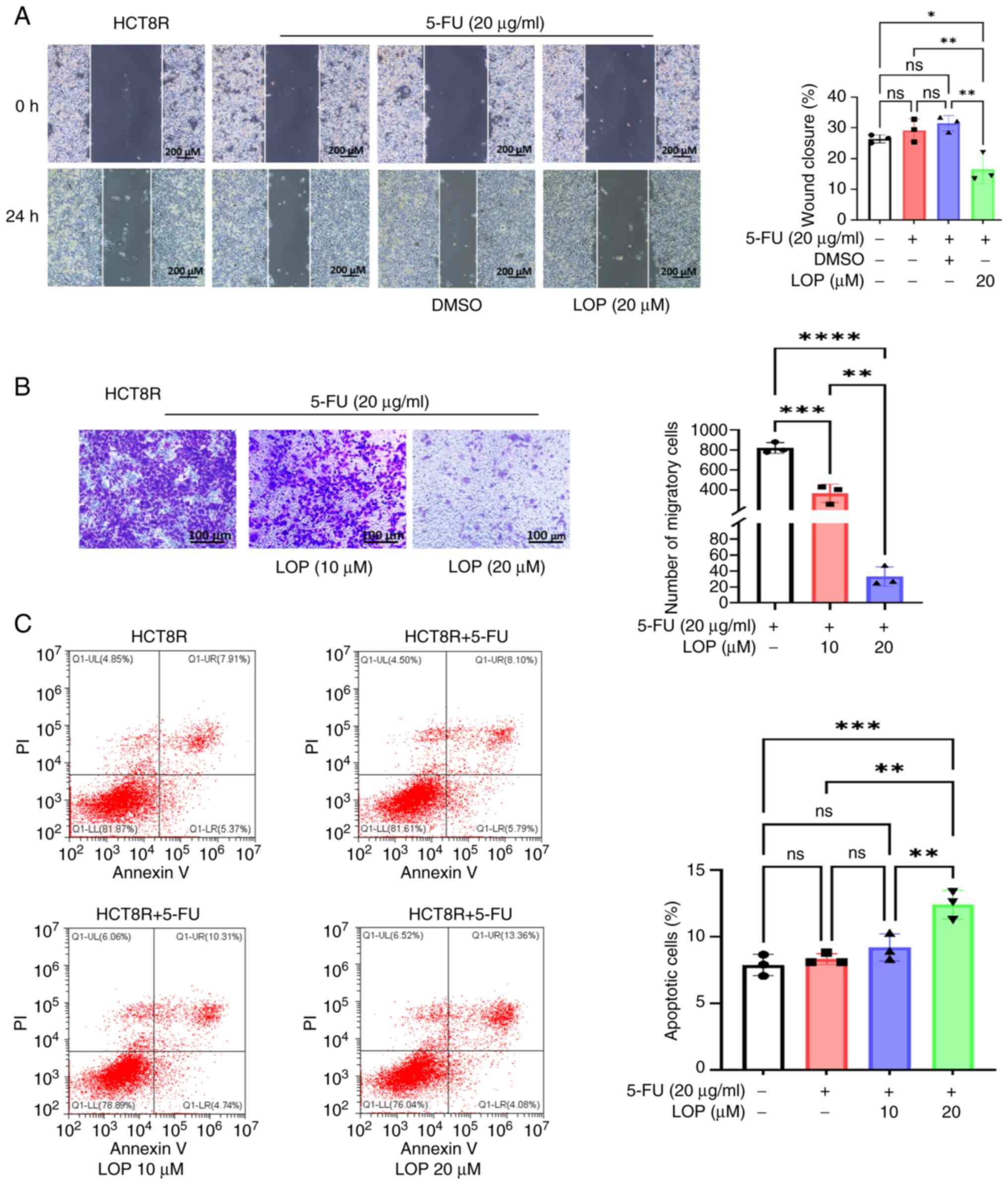

LOP augments the inhibition of HCT8R

cell migration mediated by 5-FU

Tumor cell migration is a critical factor for both

tumor invasion into normal tissues and subsequent metastasis. After

performing wound healing assays, it was observed that treatment

with 5-FU or DMSO alone did not significantly affect the migratory

capabilities of drug-resistant HCT8R cells; however, the addition

of 20 µM LOP led to a marked inhibition of cell migration compared

with in the 5-FU group (Fig. 3A).

These findings were further validated by employing Transwell

assays, which demonstrated that LOP was able to effectively

suppress HCT8R cell migration in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B).

LOP enhances 5-FU-induced apoptosis in

HCT8R cells

The balance between tumor cell proliferation and

apoptosis is a crucial determinant of drug sensitivity. The

aforementioned experiments demonstrated that LOP can effectively

inhibit the proliferation, invasion and migration of 5-FU-resistant

cells; however, its impact on apoptosis has not yet been fully

elucidated. To investigate this possibility, Annexin V-PI staining

experiments were performed for apoptosis detection. Flow cytometric

analysis revealed that treatment with 5-FU alone did not cause any

significant induction of apoptosis; by contrast, the addition of

LOP markedly increased the proportions of late apoptotic cells

compared with in the 5-FU group (Fig.

3C).

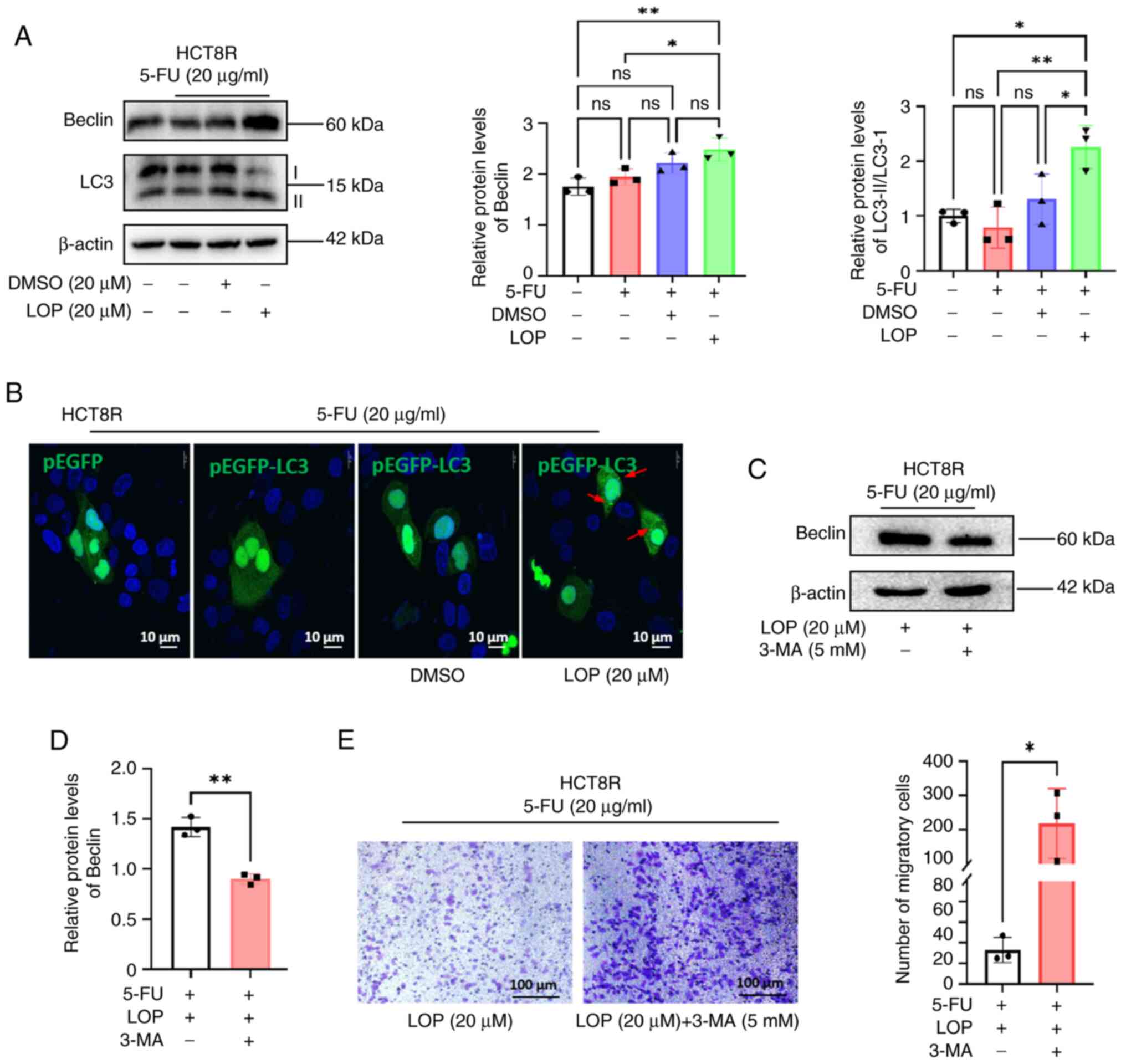

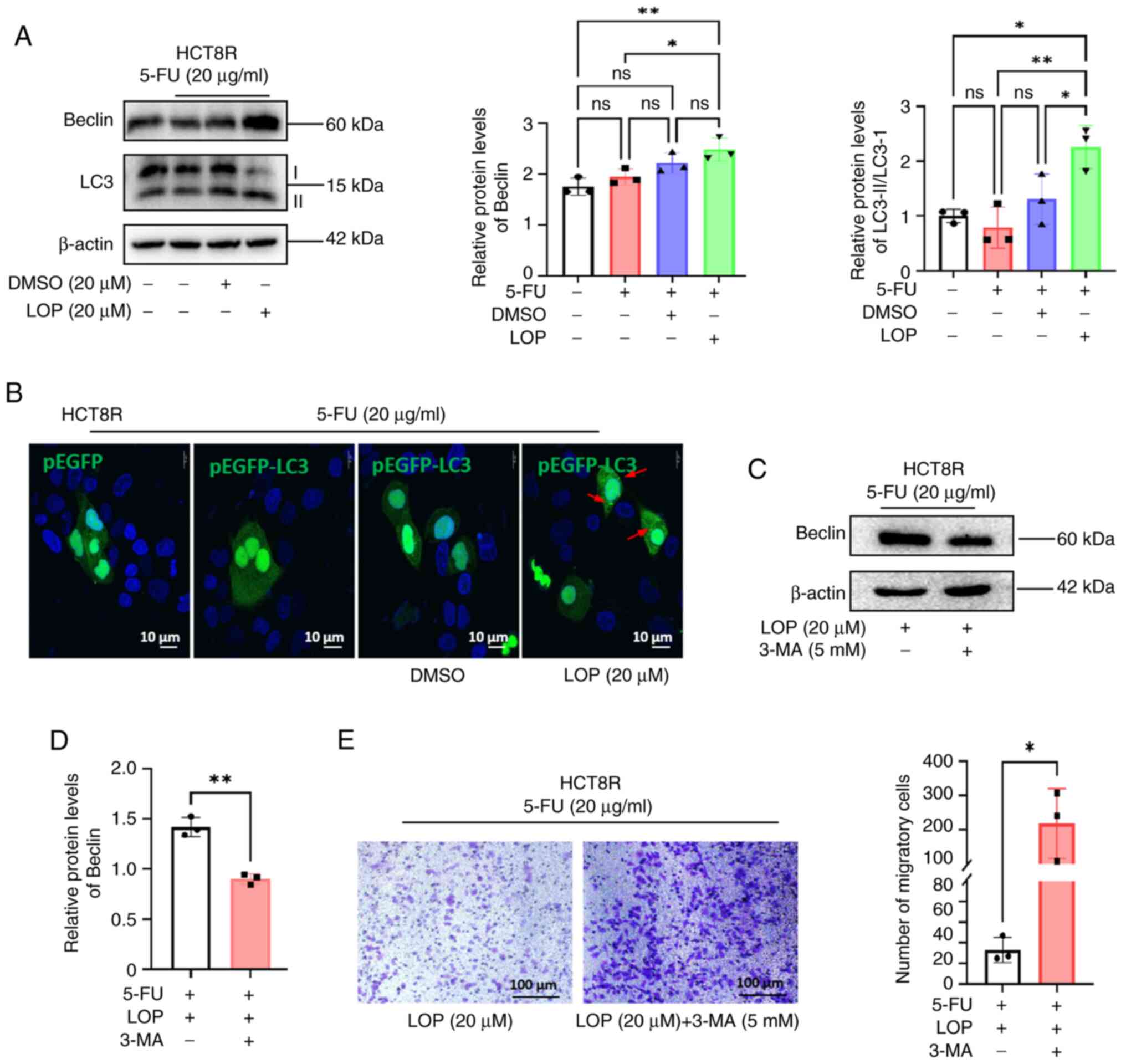

LOP reverses 5-FU resistance through

the activation of autophagy

To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the

ability of LOP to reverse 5-FU resistance, the expression levels of

the autophagy markers LC3 and Beclin were assessed using western

blot analysis. The results demonstrated that LOP treatment led to

an upregulation of Beclin expression and an increase in the

LC3-II/I ratio compared with in the 5-FU group (Fig. 4A), indicating the activation of

autophagy.

| Figure 4.LOP enhances the inhibitory effects

of 5-FU on HCT8R cells through autophagy activation. (A) Western

blot analysis of changes in LC3 and Beclin protein expression in

HCT8R cells treated with LOP and 5-FU. (B) Confocal microscopy

images, showing the generation of autophagic vesicles in HCT8R

cells transfected with the EGFP-LC3 plasmid, and treated with LOP

and 5-FU. (C) Western blot analysis of Beclin protein expression in

HCT8R cells treated with or without 3-MA. (D) Statistical analysis

of changes in Beclin expression in HCT8R cells treated with or

without 3-MA. (E) Transwell assays were performed, assessing the

migratory capability of HCT8R cells treated with LOP, 5-FU, with or

without 3-MA. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (n=3). 3-MA, 3-methyladenine;

5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; LC3,

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; LOP, loperamide;

ns, not significant. |

To further investigate this phenomenon, HCT8R cells

were transfected with EGFP or EGFP-LC3 plasmids, and autophagic

vesicles were visualized using confocal microscopy. The results

obtained showed that treatment with LOP in combination with 5-FU

resulted in dispersed, dense fluorescent spots in the cytoplasm of

resistant cells, characteristic of autophagic vesicles; by

contrast, cells treated with 5-FU or DMSO alone exhibited diffuse

fluorescence without the presence of autophagic vesicles (Fig. 4B).

To confirm that the reversal of HCT8R cell

resistance by LOP was associated with autophagy activation, the

autophagy inhibitor 3-MA was used to block autophagy. Western blot

analysis confirmed a significant downregulation of Beclin following

3-MA treatment (Fig. 4C). Moreover,

Transwell assays indicated that treatment with 3-MA led to a

reversal of the inhibition of migration caused by LOP (Fig. 4D) compared with in the group not

treated with 3-MA, highlighting the importance of autophagy as a

target of the action of LOP.

Taken together, these findings suggested that LOP

may enhance autophagy to inhibit cell proliferation, invasion and

migration, while also promoting apoptosis, thereby reversing 5-FU

resistance in HCT8 colorectal cancer cells.

Discussion

Research has highlighted several key mechanisms

contributing to tumor resistance to 5-FU. A notable factor is the

rapid degradation of 5-FU mediated by dihydropyrimidine

dehydrogenase (DPD). The liver, which is rich in DPD, performs a

crucial role in the rapid catabolism of 5-FU, leading to reduced

bioavailability and efficacy (5).

The expression of TS is another critical determinant of 5-FU

sensitivity. In 5-FU-resistant cell lines, gene amplification and

increased protein expression of TS are commonly observed (12,13).

Furthermore, polymorphisms in the TS gene promoter have been shown

to result in elevated TS expression, contributing to decreased

responsiveness to 5-FU (4).

Additionally, microsatellite instability, along with other factors,

including the MDR genes MDR3 and MDR4, the polyamine degradation

enzyme spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase, heat shock protein

co-chaperone Hsp10, chloride transporter MAT8 and Yamaguchi sarcoma

viral oncogene homolog 1, have been associated with 5-FU resistance

(5).

LOP is a widely used antidiarrheal agent that acts

as a peripheral µ-opioid receptor agonist. LOP exhibits minimal

systemic absorption (0.3% bioavailability) due to its charged state

at physiological pH, with >90% excreted unchanged in feces. A

typical dosing regimen starts with 4 mg, followed by 2 mg after

each diarrheal episode (14). Due

to its inability to cross the blood-brain barrier, LOP is

considered a safe drug for clinical use, with minimal central

nervous system side effects (15,16).

Previous studies have explored its potential beyond

gastrointestinal applications, particularly in cancer research,

where LOP has demonstrated notable anti-proliferative and

pro-apoptotic effects on bladder cancer (17), glioma (9), different types of canine cancer

(18), colon cancer (19) and NSCLC cells (20). In vitro studies have

consistently employed LOP at concentrations ranging between 20 and

100 µM to investigate its cellular mechanisms. Specifically, 20, 40

and 60 µM concentrations of LOP have been shown to effectively

inhibit the proliferation of bladder cancer cells (17). These concentrations have been

reported not only to suppress cell proliferation, but also to

promote apoptosis and induce autophagy, suggesting a multifaceted

role of LOP in cancer cell regulation (21,22).

The induction of autophagy, in particular, highlights the potential

of LOP to modulate cellular stress responses, which may be

leveraged in therapeutic strategies targeting cancer cell survival

pathways. However, the impact of LOP on 5-FU-resistant colorectal

cancer has yet to be fully investigated.

In the present study, the colorectal cancer cell

line HCT8R, which is resistant to 5-FU, was observed to exhibit

significantly enhanced invasion and migration compared with the

parental HCT8 cell line, indicating a higher level of malignancy.

It was revealed that LOP effectively inhibited the proliferation of

both HCT8 and HCT8R cells, underscoring its potential as a

therapeutic agent in colorectal cancer. Notably, treatment with LOP

was shown to markedly sensitize 5-FU-resistant HCT8R cells to

5-FU.

Using CCK-8 and EdU assays (to assess cell viability

and cell proliferation, respectively) and clonogenic assays, and an

in vivo nude mouse tumorigenic model the present study

demonstrated that a combination of 5-FU and LOP significantly

suppressed HCT8R cell proliferation, invasion and migration

compared with treatment with 5-FU alone or the control group. This

effect was found to be dose-dependent. Additionally, LOP treatment

was associated with a substantial increase in apoptosis in

5-FU-resistant cells.

The association between autophagy and drug

resistance has garnered notable attention from researchers. The

role of autophagy modulation in cancer treatment, whether via its

inhibition or activation, has been shown to yield different

outcomes, depending on the type of tumor (23–26).

Hu et al (27) demonstrated

that IL-6 promoted chemotherapy resistance in colorectal cancer by

activating autophagy through the IL-6/JAK2/Beclin 1 signaling

pathway. Additionally, Reyes-Castellanos et al (28) identified dysregulated metabolic

pathways in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), with autophagy

being a pivotal factor. This process supports tumor survival

through facilitating a continuous supply of intracellular

components via both autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms. An

elevated level of autophagy in established PDAC tumors may allow

for abnormal proliferation and growth, even under nutrient-limited

conditions.

On the other hand, enhancing cellular autophagy to

induce cell death has been shown to overcome doxorubicin resistance

(29). In the context of colorectal

cancer, numerous studies (30–32)

have suggested that autophagy contributes to resistance against

various chemotherapeutic agents. Moreover, excessive

autophagy-induced cell death has been shown to potentially be an

effective strategy to overcome MDR in tumor cells (33). Therefore, autophagy may serve as a

crucial target for modulating the sensitivity of gastrointestinal

tumors to 5-FU treatment (10,34).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

LOP may activate cellular autophagy, leading to the formation of

autophagosomes. This effect was not observed following treatment

with 5-FU alone or in combination with DMSO, underscoring the

important role of autophagy in enhancing the sensitivity of HCT8R

cells to 5-FU when LOP is present. Additionally, the inhibition of

autophagy reversed the suppressive effect of LOP on the

proliferation of resistant cells, suggesting that LOP could enhance

the sensitivity of 5-FU-resistant colorectal cancer cells through

autophagy activation. This mechanism involved the suppression of

cell proliferation, invasion and migration, as well as the

induction of apoptosis, ultimately overcoming drug resistance.

However, one limitation of the present study is that it lacked

in vivo pharmacokinetic data for LOP, and there is therefore

a need to explore additional mechanisms beyond autophagy, including

apoptosis and metabolic reprogramming. Further studies are also

needed to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms underlying

these effects, and to explore the potential of LOP in combination

therapies for colorectal cancer and other malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Xi (School of

Basic Medical Sciences, Hubei University of Medicine, Shiyan,

China.) for providing the cell lines. The authors would also like

to thank Professor Bei Li (the Biomedical Research Institute, Hubei

University of Medicine) for providing access to the flow cytometer

and chemiluminescence detection system.

Funding

The present study was supported by Joint Funds of the Hubei

Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2025AFD176), the

Free Exploration Project of Hubei University of Medicine (grant no.

FDFR201901), the Open Project of Hubei Key Laboratory of Embryonic

Stem Cell Research (grant no. ESOF2024005), the Hubei Provincial

Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2024AFD284) and the

Innovative Research Program for Graduates of Institute of Hubei

University of Medicine (grant nos. YC2023033 and YC2024007).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JY was responsible for devising the methodology,

choosing the software, performing the investigation, formal

analysis, writing the original draft of the manuscript and funding

acquisition. XA was responsible for devising the methodology,

choosing the software, performing the investigation and funding

acquisition. XQ, JK, HR and YL were responsible for devising the

methodology, choosing the software and performing the

investigation. ZL and DL were responsible for conceptualization of

the study and providing resources. JJ was responsible for

conceptualization of the study, providing resources and supervision

of the project. SL was responsible for conceptualization of the

study, funding acquisition, and writing, reviewing and editing the

manuscript. JY and XA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal studies were performed according to the

guidelines and with non-retrospective ethics approval from the

Hubei University of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee (approval no. 2023-034).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

5-FU

|

5-fluorouracil

|

|

TS

|

thymidylate synthase

|

|

LOP

|

loperamide

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

EdU

|

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

|

|

LC3

|

microtubule-associated protein 1 light

chain 3

|

|

DMSO

|

dimethyl sulfoxide

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

3-MA

|

3-methyladenine

|

|

DPD

|

dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

|

|

MDR

|

multidrug resistance

|

|

PDAC

|

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

|

References

|

1

|

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J and Pisani P:

Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 55:74–108.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J,

Lortet-Tieulent J and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:87–108. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global CANCER STATISTIcs 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rustum YM: Thymidylate synthase: A

critical target in cancer therapy? Front Biosci. 9:2467–2473. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Longley DB, Harkin DP and Johnston PG:

5-Fluorouracil: Mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat

Rev Cancer. 3:330–338. 2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Awouters F, Megens A, Verlinden M,

Schuurkes J, Niemegeers C and Janssen PAJ: Loperamide: Survey of

studies on mechanism of its antidiarrheal activity. Dig Dis Sci.

38:977–995. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhou Y, Sridhar R, Shan L, Sha W, Gu X and

Sukumar S: Loperamide, an FDA-approved antidiarrhea drug,

effectively reverses the resistance of multidrug resistant

MCF-7/MDR1 human breast cancer cells to doxorubicin-induced

cytotoxicity. Cancer Invest. 30:119–125. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zielke S, Meyer N, Mari M, Abou-El-Ardat

K, Reggiori F, van Wijk SJL, Kögel D and Fulda S: Loperamide,

pimozide, and STF-62247 trigger autophagy-dependent cell death in

glioblastoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 9:9942018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Meyer N, Henkel L, Linder B, Zielke S,

Tascher G, Trautmann S, Geisslinger G, Münch C, Fulda S, Tegeder I

and Kögel D: Autophagy activation, lipotoxicity and lysosomal

membrane permeabilization synergize to promote pimozide- and

loperamide-induced glioma cell death. Autophagy. 17:3424–3443.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tang JC, Feng YL, Liang X and Cai XJ:

Autophagy in 5-fluorouracil therapy in gastrointestinal cancer:

Trends and challenges. Chin Med J (Engl). 129:456–563. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang BR, Han JB, Jiang Y, Xu S, Yang R,

Kong YG, Tao ZZ, Hua QQ, Zou Y and Chen SM: CENPN suppresses

autophagy and increases paclitaxel resistance in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cells by inhibiting the CREB-VAMP8 signaling axis.

Autophagy. 20:329–348. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Johnston PG, Drake JC, Trepel J and

Allegra CJ: Immunological quantitation of thymidylate synthase

using the monoclonal antibody TS 106 in 5-fluorouracil-sensitive

and -resistant human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 52:4306–4312.

1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Copur S, Aiba K, Drake JC, Allegra CJ and

Chu E: Thymidylate synthase gene amplification in human colon

cancer cell lines resistant to 5-fluorouracil. Biochem Pharmacol.

49:1419–1426. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Baker DE: Loperamide: A pharmacological

review. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 7 (Suppl 3):S11–S18.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Parkar N, Spencer NJ, Wiklendt L, Olson T,

Young W, Janssen P, McNabb WC and Dalziel JE: Novel insights into

mechanisms of inhibition of colonic motility by loperamide. Front

Neurosci. 18:14249362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu PE and Juurlink DN: Clinical review:

Loperamide toxicity. Ann Emerg Med. 70:245–252. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wu J, Guo Q, Li J, Yuan H, Xiao C, Qiu J,

Wu Q and Wang D: Loperamide induces protective autophagy and

apoptosis through the ROS/JNK signaling pathway in bladder cancer.

Biochem Pharmacol. 218:1158702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Regan RC, Gogal RM Jr, Barber JP,

Tuckfield RC, Howerth EW and Lawrence JA: Cytotoxic effects of

loperamide hydrochloride on canine cancer cells. J Vet Med Sci.

76:1563–1568. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kim IY, Shim MJ, Lee DM, Lee AR, Kim MA,

Yoon MJ, Kwon MR, Lee HI, Seo MJ, Choi YW and Choi KS: Loperamide

overcomes the resistance of colon cancer cells to bortezomib by

inducing CHOP-mediated paraptosis-like cell death. Biochem

Pharmacol. 162:41–54. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tong CWS, Wu MMX, Yan VW, Cho WCS and To

KKW: Repurposing loperamide to overcome gefitinib resistance by

triggering apoptosis independent of autophagy induction in KRAS

mutant NSCLC cells. Cancer Treat Res Commun.

25:1002292020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang S, Li Z, Pan M, Ma J, Pan Z, Zhang P

and Cao W: Repurposing of antidiarrheal loperamide for treating

melanoma by inducing cell apoptosis and cell metastasis suppression

in vitro and in vivo. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 24:1015–1030. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Roncuzzi L, Perut F and Baldini N:

Repurposing of loperamide as a new drug with anticancer activity

for human osteosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 44:1063–1070. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Huang T, Song X, Yang Y, Wan X, Alvarez

AA, Sastry N, Feng H, Hu B and Cheng SY: Autophagy and hallmarks of

cancer. Crit Rev Oncog. 23:247–267. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Singh SS, Vats S, Chia AYQ, Tan TZ, Deng

S, Ong MS, Arfuso F, Yap CT, Goh BC, Sethi G, et al: Dual role of

autophagy in hallmarks of cancer. Oncogene. 37:1142–1158. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yun CW, Jeon J, Go G, Lee JH and Lee SH:

The dual role of autophagy in cancer development and a therapeutic

strategy for cancer by targeting autophagy. IJMS. 22:1792020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chang H and Zou Z: Targeting autophagy to

overcome drug resistance: Further developments. J Hematol Oncol.

13:1592020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hu F, Song D, Yan Y, Huang C, Shen C, Lan

J, Chen Y, Liu A, Wu Q, Sun L, et al: IL-6 regulates autophagy and

chemotherapy resistance by promoting BECN1 phosphorylation. Nat

Commun. 12:36512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Reyes-Castellanos G, Abdel Hadi N and

Carrier A: Autophagy contributes to metabolic reprogramming and

therapeutic resistance in pancreatic tumors. Cells. 11:4262022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen C, Lu L, Yan S, Yi H, Yao H, Wu D, He

G, Tao X and Deng X: Autophagy and doxorubicin resistance in

cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 29:1–9. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yu T, Guo F, Yu Y, Sun T, Ma D, Han J,

Qian Y, Kryczek I, Sun D, Nagarsheth N, et al: Fusobacterium

nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to colorectal cancer by

modulating autophagy. Cell. 170:548–563.e16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Feng Z, Zhang S, Han Q, Chu T, Wang H, Yu

L, Zhang W, Liu J, Liang W, Xue J, et al: Liensinine sensitizes

colorectal cancer cells to oxaliplatin by targeting HIF-1α to

inhibit autophagy. Phytomedicine. 129:1556472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen Z, Chen H, Huang L, Duan B, Dai S,

Cai W, Sun M, Jiang Z, Lu R, Jiang Y, et al: ATB°,+-targeted

nanoparticles initiate autophagy suppression to overcome

chemoresistance for enhanced colorectal cancer therapy. Int J

Pharm. 641:1230822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li YJ, Lei YH, Yao N, Wang CR, Hu N, Ye

WC, Zhang DM and Chen ZS: Autophagy and multidrug resistance in

cancer. Chin J Cancer. 36:522017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhang R, Pan T, Xiang Y, Zhang M, Feng J,

Liu S, Duan T, Chen P, Zhai B, Chen X, et al: β-Elemene reverses

the resistance of p53-deficient colorectal cancer cells to

5-fluorouracil by inducing pro-death autophagy and cyclin

D3-dependent cycle arrest. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 8:3782020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|