Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the leading cause

of liver cancer, accounting for an overwhelming 90% of all cases

(1). This stark reality highlights

the urgent need for proactive prevention, early detection, and

treatment measures to combat this formidable disease. The treatment

options for patients with HCC depend on their clinical stage

(2). Due to the difficulties in

early detection and the rapid progression of the disease, numerous

patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, and chemotherapeutic

agents are the primary form of systemic therapy for these patients

(1).

Sorafenib and regorafenib are oral multi-kinase

inhibitor that targets several tyrosine kinases, including

serine-threonine kinases Raf-1 and B-Raf, which are involved in the

MAPK/ERK pathway (3,4). They are also found to inhibit the

platelet-derived growth factor receptor and the vascular

endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR-2/3) (5). Sorafenib and regorafenib have been

approved by the Food and Drug Administration as the first-line and

second-line treatments, respectively, to help control tumor

angiogenesis and progression in patients with advanced HCC

(6,7). While sorafenib and regorafenib are the

main systemic therapies for advanced HCC, their effectiveness and

application are frequently hindered by severe adverse reactions and

the common development of drug resistance (8). Grasping the intricate mechanisms

behind this resistance is essential for devising effective

strategies to overcome it.

Prolonged use of antitumor drugs can frequently lead

to the development of acquired resistance, ultimately undermining

the effectiveness of these vital treatments. Multiple critical

pathways have been identified that lead to acquired resistance to

sorafenib in HCC (9). Importantly,

inhibiting T-cell attack in the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays

a significant role in promoting drug resistance (10). Programmed death-ligand-1 (PD-L1) is

an immune checkpoint protein found on numerous cancer cells that

suppresses anticancer immunity by interacting with PD-1 on T cells

(11). Overexpression of PD-L1 is

found to increase the drug resistance in cisplatin-resistant small

cell lung cancer cells, enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer, and

sorafenib-resistant HCC (12–14).

Accordingly, PD-1-PD-L1 blockade has been shown to foster

CD8+ T-cell infiltration and therapeutic efficacy of

sorafenib and regorafenib in tumor-bearing mouse models (15,16).

Despite the critical role of PD-L1 in promoting resistance to

sorafenib and regorafenib in HCC, the mechanisms underlying PD-L1

upregulation in HCC cells following these drug treatments remain

incompletely understood (17).

IL-33 is a member of the IL-1 cytokine family and is

widely expressed in various cell types, primarily localized in the

nucleus to regulate gene transcription (18). Importantly, IL-33 is able to be

released as an alarmin to activate innate and adaptive immune

responses by binding its specific receptor ST2L in response to cell

stress, pathogen infection, tissue injury and necrotic cell death

(19–21). When IL-33 binds to ST2L, this

signaling triggers the MyD88-dependent pathways and subsequently

induces the activation of activator protein-1 and NF-κB

transcription factors, leading to inflammatory gene expression

(22,23). This IL-33/ST2L signaling has been

observed in accelerating multiple types of cancer progression,

including HCC (24,25). In HCC, IL-33/ST2L signaling has been

shown to enhance the stemness of HCC cells and alter the immune

responses within the TME, leading to accelerated HCC progression

(25–27). Notably, our current findings

indicate that lung cancer cells treated with cisplatin can release

IL-33, creating a positive feedback loop through IL-33/ST2L that

limits the efficacy of cisplatin therapy (28). However, it is unclear whether

IL-33/ST2L signaling participates in the development of acquired

resistance to sorafenib or regorafenib in HCC.

In the present study, it was found that sorafenib

and regorafenib treatments induced cell senescence in HCC and

promoted the secretion of IL-33 through an IL-33/ST2L positive

feedback loop. The secreted IL-33 enhanced PD-L1 expression in HCC

cells by activating NF-κB pathways in response to these treatments.

Blockage of the IL-33 signaling pathway using anti-IL-33 or

anti-ST2L antibodies alongside sorafenib resulted in significant

tumor growth reduction in HCC-bearing mice, decreased tumor PD-L1

expression, and increased CD8+ T cell infiltration.

However, the increased efficacy was not observed in

immunocompromised mice, indicating the crucial role of T cells in

the reduced efficacy of sorafenib due to IL-33. The current

findings highlight how IL-33 may undermine the effectiveness of

sorafenib and regorafenib, suggesting that targeting the IL-33/ST2L

axis could enhance therapeutic outcomes in HCC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

Human hepatoma cell lines Huh-7 cells were obtained

from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center.

ML-15a is a mouse hepatoma cell line that was developed

from ML-1 cells after being adapted through five generations in

BALB/c mice. It originates from the parental ML-1 hepatoma cell

line, which was established using liver cells from BALB/c mice that

were transformed with the hepatitis B virus X (HBx) gene (29). It was noted that ML-1 is not

registered in the Cellosaurus database and therefore does not have

an assigned CVCL number. Huh7 and ML-15a cells were

maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified

incubator.

Cell death assay

Huh-7 cells (5×103 cells/well) were

seeded in 96-well plates and treated with sorafenib (cat. no.

SC-220125; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or regorafenib (cat. no.

SC-477163; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at the indicated

concentrations for 24 to 96 h. Cell death was assessed using the

FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit with propidium iodide (cat.

no. 640914; BioLegend, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Stained cells were analyzed by a CytoFLEX flow

cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.), and the acquired data were

processed with CytExpert software (version 2.3; Beckman Coulter,

Inc.).

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested and lysed with Cell Lysis

Buffer (cat. no. 9803; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.)

supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. A total of

30 µg of protein lysates, quantified using the Bradford assay, was

separated on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinyl difluoride

membranes. Membranes were then blocked with 5% skimmed milk in TBST

(TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature and

incubated with specific primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The

antibodies used were as follows: anti-IL-33 (1:1,000; cat. no.

LG3314; Leadgene Biomedical), anti-p16 (1:2,000; cat. no. ab81278;

Abcam), anti-p21 (1:1,000; cat. no. 2947S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), anti-PD-L1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 13684S; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-β-actin (1:5,000; cat. no.

ab8226-20; Abcam). The membranes were then washed and incubated

with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse (1:5,000; cat.

no. GTX213111-01; GeneTex, Inc.) or anti-rabbit (1:5,000; cat. no.

GTX213110-01; GeneTex, Inc.) antibodies for 1 h at room

temperature. Protein expression was visualized by enhanced

chemiluminescence treatment using Western Lightning Plus-ECL

(PerkinElmer, Inc.) and Amersham™ Imager 600 (GE Healthcare).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the

Quick-RNA™ MiniPrep kit (cat. no. R1055; Zymo Research), and then 1

µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using M-MLV

Reverse Transcriptase (cat. no. LDG0006RF; Leadgene Biomedical)

with random primers under the following conditions: 25°C for 10 min

(primer annealing), 42°C for 60 min (cDNA synthesis), and 70°C for

10 min (enzyme inactivation). qPCR was performed with the FastStart

Universal SYBR Green Master (Rox) (cat. no. 04913850001; Roche

Diagnostics) in the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). PCR amplification was

performed with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed

by 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec and

combined annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. Gene expression

levels were normalized to ACTB, and relative expression was

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (30). The following primer sequences were

used: IL33 (orward, 5′-CAAAGAAGTTTGCCCCATGT-3′ and reverse,

5′-AAGGCAAAGCACTCCACAGT-3′; CD274 forward,

5′-AAACAATTAGACCTGGCTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCTTACCACTCAGGACTTG-3′;

and ACTB forward, 5′-AAGGAGAAGCTGTGCTACGTCGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGACAGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACA-3′.

Cell proliferation analysis

Huh-7 cells (2×105 cells/well) were

seeded in 6-well plates and treated with sorafenib (1 and 10 µM) or

regorafenib (10 and 20 µM) at the indicated concentrations for 5 to

7 days. At the end of treatment, cells were trypsinized, collected,

and stained with 0.4% Trypan Blue solution (cat. no. T8154;

MilliporeSigma) to assess cell viability. Viable (unstained) and

non-viable (stained) cells were counted using a hemocytometer under

a light microscope. Cell proliferation was determined by

quantifying the number of viable cells at each time point.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase

(SA-β-gal) staining

SA-β-gal activity was detected using the Senescence

β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (cat. no. 9860; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Briefly, Huh-7 cells were treated with sorafenib (10 µM) or

regorafenib (20 µM) for 4 days. After treatment, cells were washed

with PBS and fixed with 1X Fixative Solution for 10-15 min at room

temperature. Following two washes with PBS, cells were incubated

with β-galactosidase staining solution (pH 6.0) at 37°C in a sealed

container without CO2 for 1 to 2 days. SA-β-gal-positive

cells were observed and imaged using an Olympus BX61 light

microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Flow cytometry

To detect surface expression of PD-L1 on Huh-7

cells, the cells were harvested and washed with PBS. The prepared

cells were incubated with APC-conjugated anti-human PD-L1 antibody

(1:200; cat. no. 393609; BioLegend, Inc.) in staining buffer (2%

FBS and 0.1% sodium azide in PBS). The staining was performed for

30 min on ice in the dark, followed by flow cytometric analysis.

For immunophenotyping of tumor-infiltrating immune cells isolated

from HCC-bearing mice, single-cell suspensions were incubated with

fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies in staining buffer

for 30 min on ice in the dark. The following antibodies were used:

FITC anti-mouse CD8a antibody (cat. no. 553031; BD Biosciences), PE

anti-mouse CD4 antibody (cat. no. 553049; BD Biosciences) and PE

anti-mouse CD152 (CTLA-4) antibody (cat. no. 106305; BioLegend,

Inc.). The mean fluorescence intensity and the proportion of cells

within a specific gate were detected using a CytoFLEX (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.) and analyzed using CytExpert software (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.).

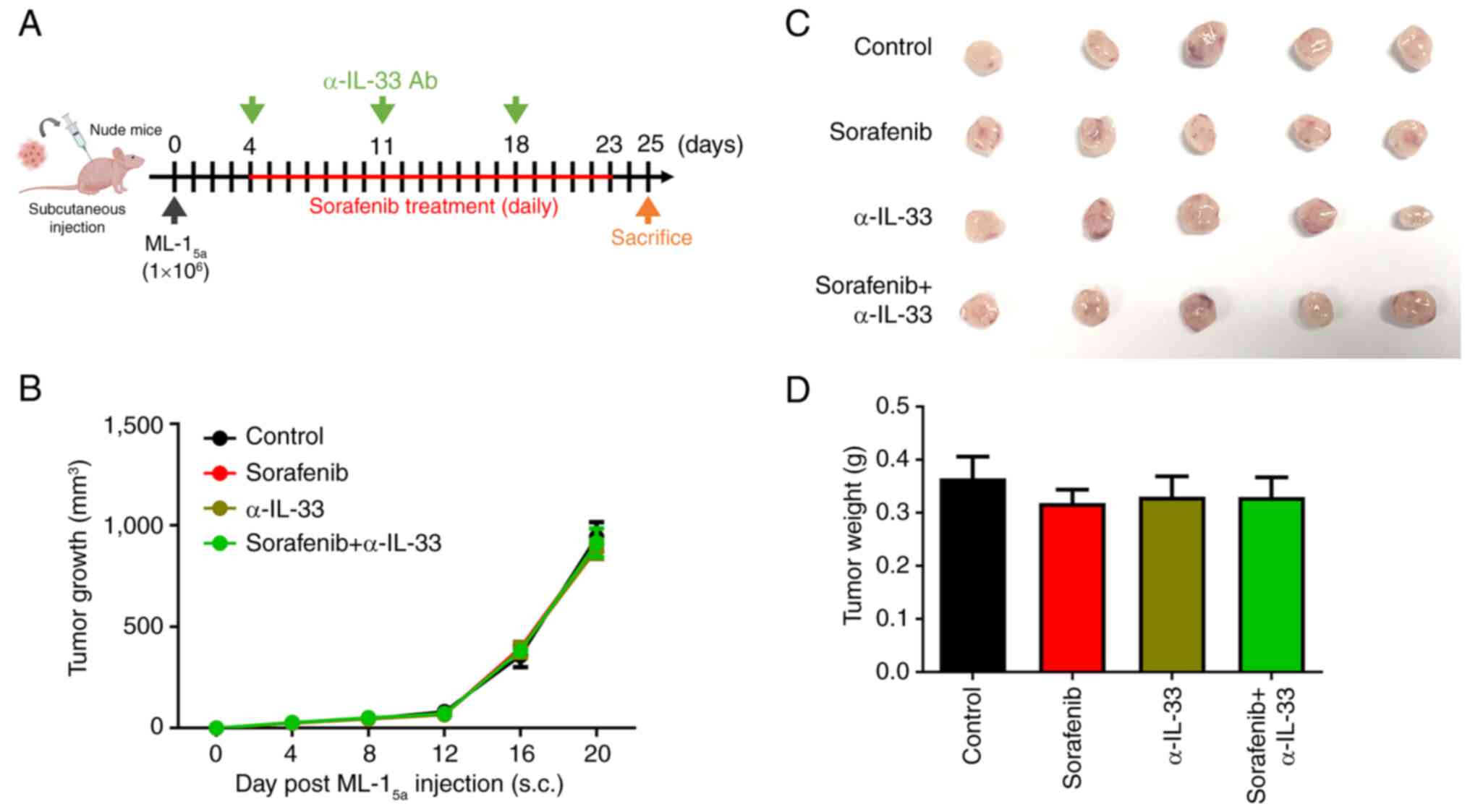

HCC-bearing subcutaneous mouse

model

A total of 36 male BALB/c mice and 20 male nude mice

(8 weeks-old; weighing 25 g) were used. Mice were housed under

standard conditions with a temperature of 22±2°C, relative humidity

of 50±5%, a 12/12-h light/dark cycle, and ad libitum access

to food and water. All animal experiments were conducted in

accordance with National Cheng Kung University institutional

guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals (approval no.

107130; Tainan, Taiwan). To establish the subcutaneous tumor model,

1×106 ML-15a cells were injected into the

flank of BALB/c or nude mice. Mice harboring HCC allografts were

treated with IgG (10 µg/g), sorafenib (10 µg/g), α-IL-33 (10 µg/g;

cat. no. LG3314; Leadgene Biomedical), and/or α-ST2L (10 µg/g; cat.

no. LGT2105; Leadgene Biomedical) via intraperitoneal (i.p.)

injection. Mice received daily i.p. injections of sorafenib from

day 7 to day 27. For both monotherapy and combination therapy

groups, α-IL-33 or α-ST2L antibodies were administered

intraperitoneally on days 7, 14 and 21 post-inoculation. Tumor

volume was measured every four days starting on day 5

post-inoculation using a digital caliper and calculated using the

formula: V=(length2 × width)/2. For HCC-bearing nude

mice, mice received daily i.p. injections of sorafenib (10 µg/g)

from day 4 to day 23, and/or α-IL-33 (10 µg/g) on days 4, 11, and

18. On day 25 or 29 after subcutaneous injection, the HCC-bearing

mice were sacrificed, and their solid tumors were removed to

determine the tumor weight and infiltrated phenotypes of immune

cells by flow cytometry. In the present study, mice were euthanized

by carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation, with CO2

introduced into the chamber at a displacement rate of 30% of the

chamber volume per min, in accordance with institutional animal

care guidelines. Death was confirmed by the absence of respiration

and heartbeat, followed by cervical dislocation as a secondary

method. All animal experiments were performed between 2020 and

2021.

Immunohistochemistry assay

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections

(4-µm thick) of mouse HCC tumors were deparaffinized with xylene

and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol solutions.

Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the sections in 10 mM

citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95-100°C for 10 min. Endogenous

peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15

min at room temperature. After washing, the sections were blocked

with blocking reagent for 1 h at room temperature and then

incubated with primary antibodies against IL-33 (1:200; cat. no.

LG3314; Leadgene Biomedical) and PD-L1 (1:200; cat. no. 13684S;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) at 4°C overnight. The

immunoreactions were revealed using the secondary antibody of

OneStep Polymer HRP anti-mouse/rat/rabbit Detection System (cat.

no. GTX83398; GeneTex, Inc.) and using DAB as chromogen. Nuclei

were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin (cat. no. HMM125;

ScyTek Laboratories Inc.), and slides were subsequently dehydrated

and mounted for microscopic analysis.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) assay of IL-6 concentration

Huh7 cells were treated with sorafenib (10 µM) or

regorafenib (20 µM) for 72 h, and the culture supernatants were

collected. Human IL-6 levels were quantified using a human IL-6

DuoSet ELISA kit (cat. no. DY206; R&D Systems, Inc.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions. Optical density (OD) was

measured at 450 nm using a SpectraMax iD5 Multi-Mode Microplate

Reader (Molecular Devices). The IL-6 concentrations were calculated

from a standard curve (Fig.

S2).

Correlation analysis of IL33 and CD274

expression in patients with liver hepatocellular carcinoma

(LIHC)

The correlation between IL33 and CD274

expression in LIHC was analyzed using the TIMER2.0 web server

(http://timer.cistrome.org/) (31), which integrates RNA-seq data from

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). Spearman's correlation

analysis was performed to assess the association between

IL33 and CD274 mRNA expression levels in the

TCGA-LIHC cohort (Fig. S3).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviations

(SD). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post hoc test with GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software

Inc.; Dotmatics). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Sorafenib and regorafenib trigger an

IL-33/ST2L positive feedback loop in senescent HCC cells

Our current findings showed that cisplatin-treated

lung cancer cells can release IL-33 to cause an IL-33/ST2L positive

feedback loop to limit cisplatin therapeutic efficacy (28). IL-33/ST2L signaling has been

implicated in promoting the progression of HCC (26,32).

However, whether HCC cells can release IL-33 in response to stress

induced by sorafenib and regorafenib remains unclear. To

investigate this, Huh-7 cells were treated with various doses of

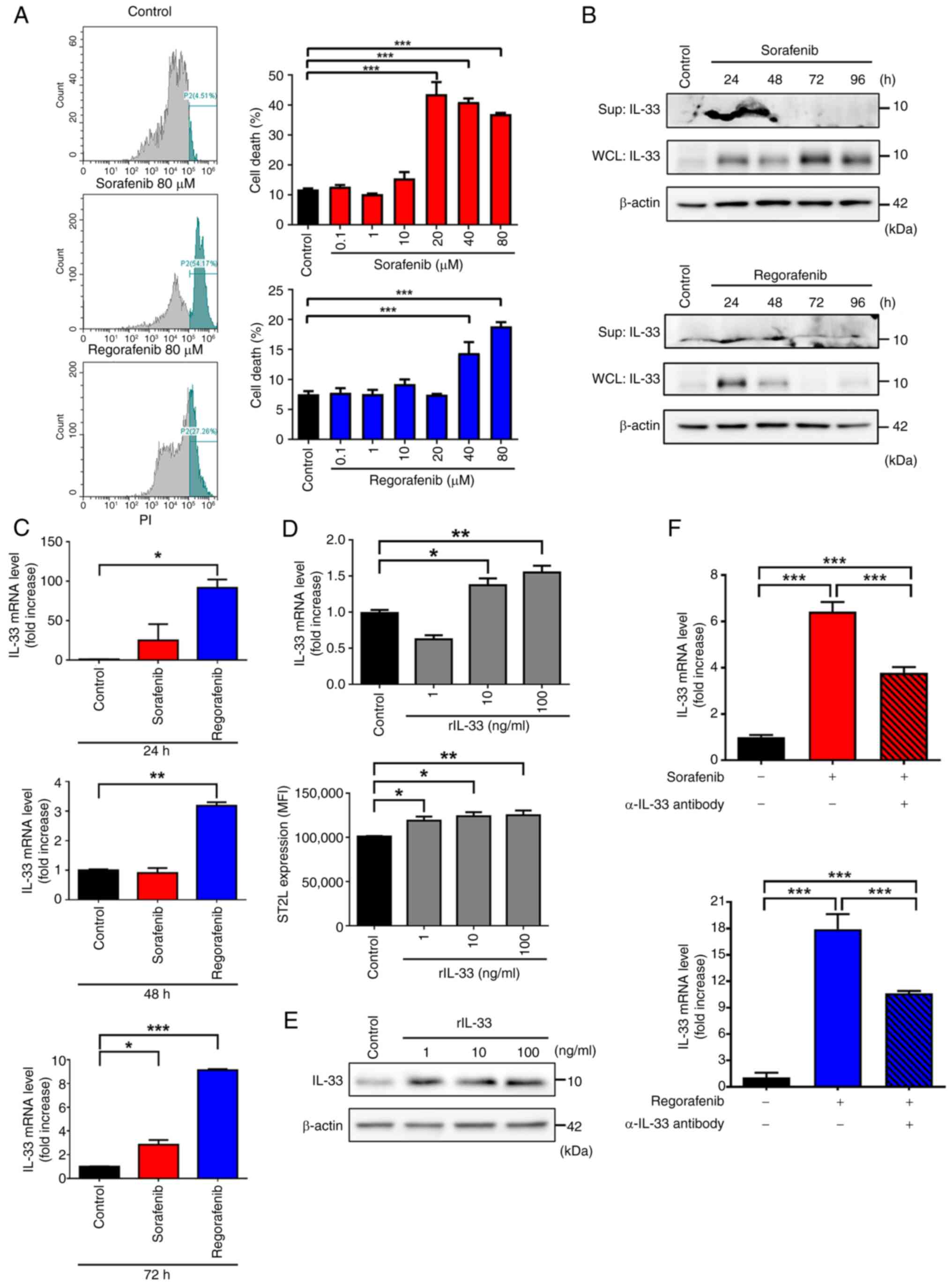

sorafenib and regorafenib. Significant cytotoxicity was observed at

concentrations exceeding 20 µM for sorafenib and 40 µM for

regorafenib (Fig. 1A). To avoid the

passive release of IL-33 due to cell death, Huh-7 cells were

treated with 10 µM sorafenib and 20 µM regorafenib in the following

experiments. As shown in Fig. 1B,

both sorafenib and regorafenib induced the release of IL-33 in

Huh-7 cells at 24 and 48 h post-treatment. Interestingly, a notable

increase in the cytosolic protein level of IL-33 and the mRNA level

of IL-33 was observed in both sorafenib and regorafenib-treated

Huh-7 cells (Fig. 1B and C). Since

an IL-33 positive feedback loop has been previously identified in

macrophages and lung cancer cells (28,33),

it was next tested whether this loop occurs in sorafenib and

regorafenib-treated Huh-7 cells. To examine this, the mRNA levels

of IL33 and ST2L were first measured in recombinant

IL-33 (rIL-33)-treated Huh-7 cells. Similar to previous findings,

rIL-33 treatment upregulated the mRNA levels of IL33 and

protein levels of surface ST2L in Huh-7 cells (Fig. 1D). Additionally, increased protein

levels of IL-33 were also observed following rIL-33 treatment

(Fig. 1E). Furthermore, blocking

IL-33 signaling with a neutralizing anti-IL-33 (α-IL-33) antibody

abolished the upregulation of IL-33 induced by sorafenib and

regorafenib in Huh-7 cells (Fig.

1F), indicating that sorafenib and regorafenib trigger an

IL-33/ST2L positive feedback loop in HCC cells. Notably, a recent

study pointed out that IL-33 was highly induced in senescent

hepatic stellate cells within the TME of HCC (27). Given that sorafenib and regorafenib

treatment can lead to cellular senescence in HCC cells (34), it was hypothesized that IL-33 is

induced in senescent HCC cells triggered by these treatments. To

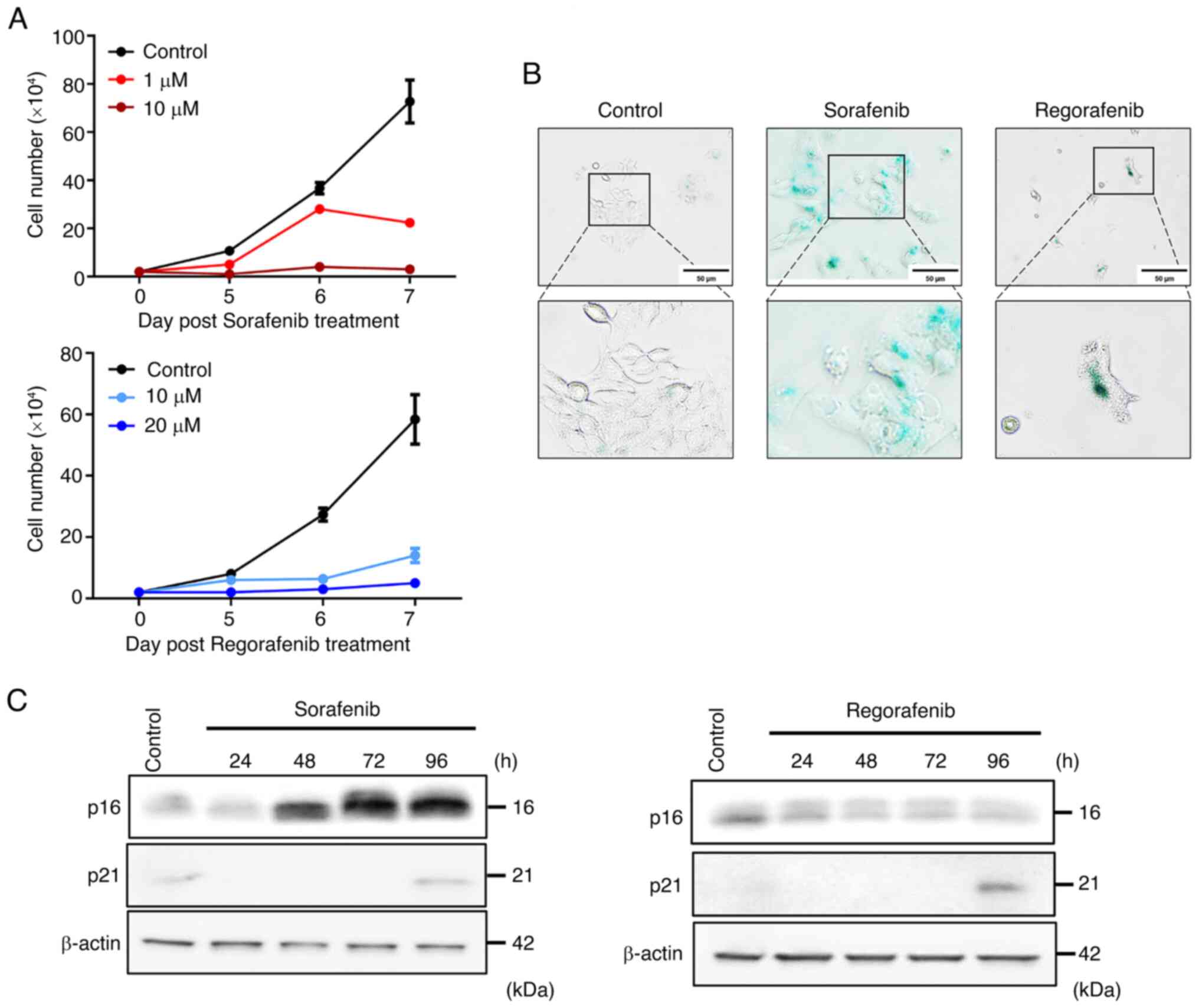

examine whether sorafenib and regorafenib can cause cell growth

inhibition, a characteristic of cellular senescence, Huh-7 cells

were treated with various concentrations of sorafenib and

regorafenib for 24 to 96 h. Significant cell growth arrest was

observed in Huh-7 cells treated with 10 µM sorafenib and 20 µM

regorafenib (Fig. 2A).

Additionally, a significant increase in SA-β-galactosidase

expression was observed in sorafenib and regorafenib-treated Huh-7

cells (Fig. 2B). It has been

reported that cellular senescence is mainly regulated by

p16INK4/CDKN2 and p21WAF1/Cip1 pathways

(35). The present results revealed

that sorafenib induced upregulation of p16, while regorafenib

increased p21 expression post-treatment compared with the control

group (Fig. 2C). These findings

collectively indicate that sorafenib and regorafenib trigger an

IL-33/ST2L positive feedback loop in senescent HCC cells.

Sorafenib and regorafenib treatments

lead to PD-L1 upregulation via IL-33 signaling in HCC cells

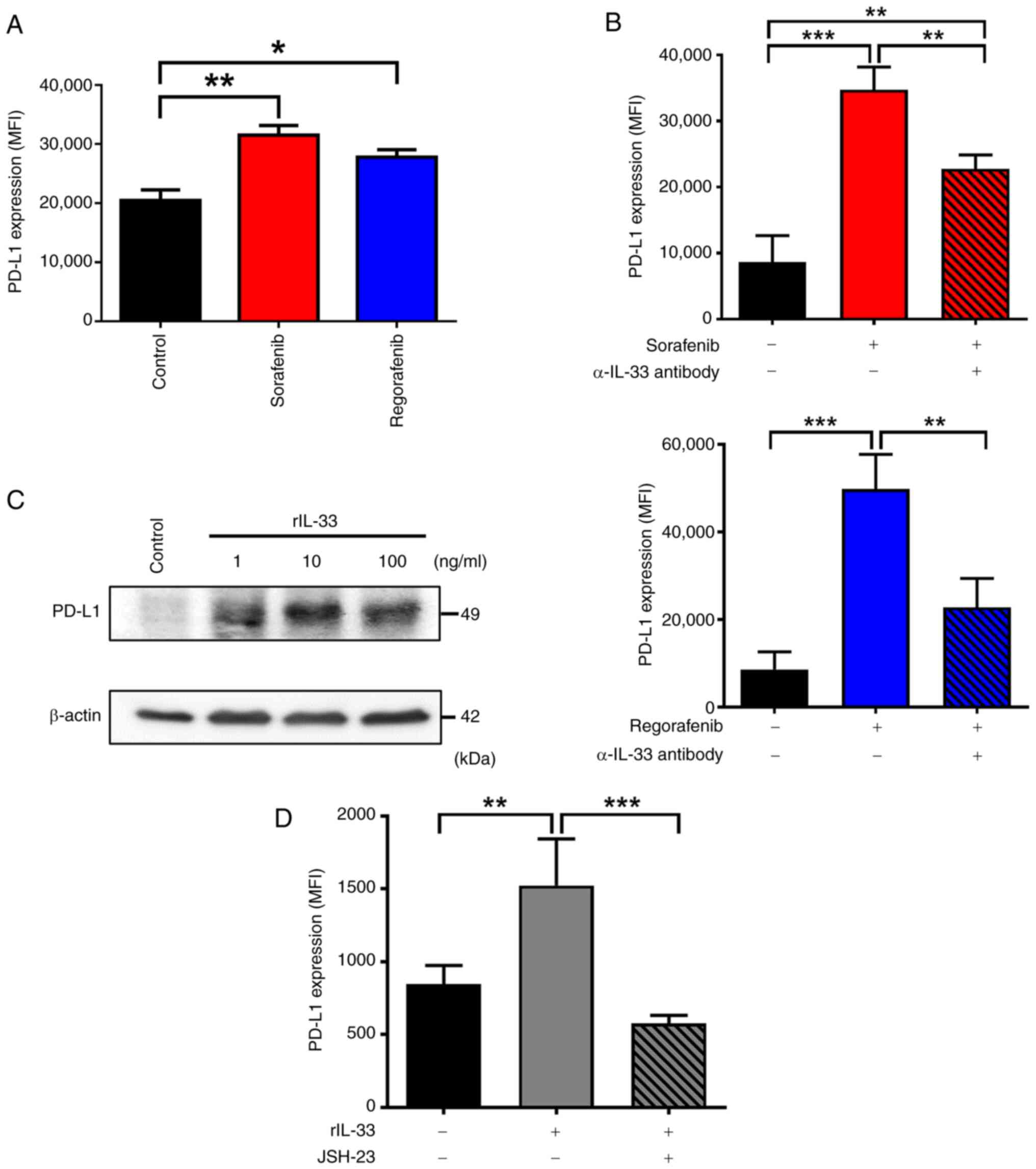

It has been reported that IL-33/ST2L signaling can

induce PD-L1 expression, leading to immune escape in oral squamous

cell carcinoma (36). Notably,

elevated PD-L1 expression in patients with HCC correlates with poor

survival and resistance to sorafenib (14). It was investigated whether sorafenib

and regorafenib treatments increase PD-L1 expression via IL-33

release. As shown in Fig. 3A, both

sorafenib and regorafenib enhanced PD-L1 expression on the plasma

membrane of Huh-7 cells. Blocking IL-33 signaling with a

neutralizing α-IL-33 antibody abolished the upregulation of PD-L1

induced by sorafenib and regorafenib in Huh-7 cells (Fig. 3B), suggesting that IL-33 released

from these drug-treated cells induces PD-L1 expression. To further

examine whether IL-33 induces PD-L1 upregulation in HCC cells,

Huh-7 cells were treated with rIL-33 protein. The immunoblot

results revealed that protein levels of PD-L1 increased following

stimulation with rIL-33 (Fig. 3C).

Additionally, elevated PD-L1 on the surface of rIL-33-treated Huh-7

cells was also detected (Fig. 3D),

confirming that IL-33 is capable of inducing PD-L1 expression in

HCC cells. The regulation of PD-L1 expression mainly involves the

participation of transcriptional regulators, including NF-κB

(37). Given that our current

findings revealed that NF-κB mediates IL-33-dependent actions in

the TME (28), it was examined

whether IL-33 induced PD-L1 expression via NF-κB in HCC cells. The

current data showed that rIL-33-induced upregulation of PD-L1 was

significantly abolished in the presence of NF-κB inhibitor

(Fig. 3D). These data collectively

indicated that sorafenib and regorafenib treatments lead to PD-L1

upregulation via IL-33 signaling in HCC cells.

Blockage of IL-33 or ST2L enhances the

antitumor immune responses and therapeutic efficacy of sorafenib in

HCC-bearing mice

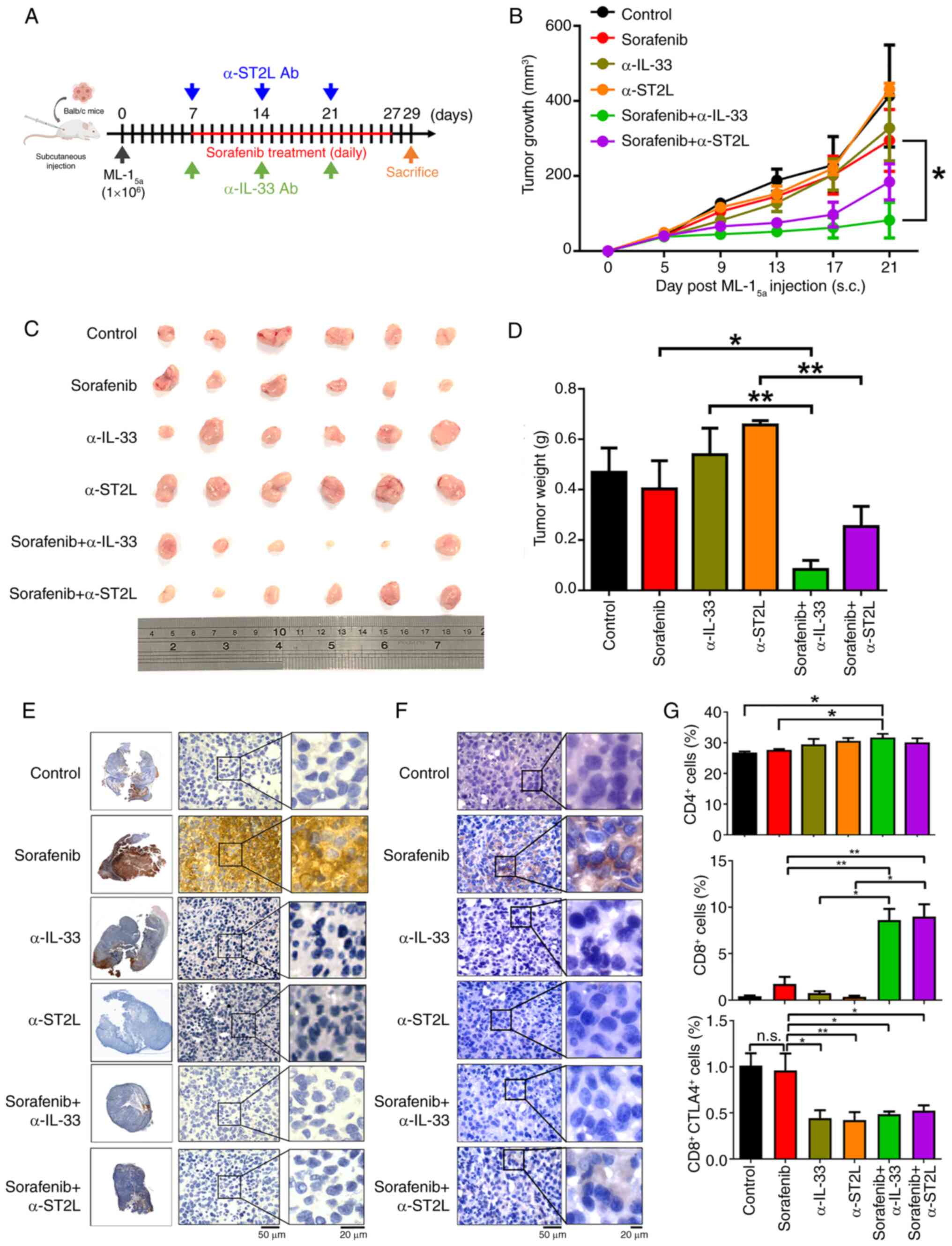

Next, it was examined whether blocking IL-33/ST2L

signaling could enhance the therapeutic efficacy of sorafenib in

HCC-bearing mice. To test this hypothesis, low-dose sorafenib

treatment (10 mg/kg) (38) was

combined with α-IL-33 or α-ST2L neutralizing antibodies (10 mg/kg)

in a subcutaneous HCC mouse model by inoculating a mouse HCC cell

line ML-15a in BALB/c mice (39) (Fig.

4A). To assess whether these combination treatments could cause

significant toxicity in mice, body weights and serum levels of

glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), glutamic pyruvic

transaminase (GPT), albumin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and

creatinine were monitored. The results revealed no significant

changes in these parameters in mice undergoing the combined

treatment compared with control mice (Fig. S1A and B), indicating that no

significant toxicity was induced by these treatments. In Fig. 4C, the maximum tumor observed

measured 9 mm in length and 13 mm in width, corresponding to a

calculated tumor volume of 526.5 mm3 and a maximum

diameter of 13 mm. It was found that single treatments with

sorafenib, α-IL-33, or α-ST2L neutralizing antibodies in

HCC-bearing mice showed no significant differences in tumor size,

growth rate, and weight compared with control groups. Notably,

combined treatment with sorafenib and either α-IL-33 or α-ST2L

neutralizing antibodies resulted in a remarkable reduction in tumor

size, growth rate and weight (Fig.

4B-D). These data indicated that blocking IL-33/ST2L can

enhance the antitumor efficacy of sorafenib in HCC. Additionally,

consistent with in vitro findings, sorafenib treatment

induced elevated expression of IL-33 as well as PD-L1 in HCC

tumors, which was inhibited by combined treatments with α-IL-33 or

α-ST2L neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 4E

and F). Given that IL-33/ST2L signaling-induced PD-L1

expression can lead to immune escape (36), the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

were analyzed 21 days after HCC inoculation. A slight increase was

observed in tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells in HCC

tumors treated with a combination of sorafenib and α-IL-33

neutralizing antibodies compared with other treatment groups. It is

worth noting that a significant increase in tumor-infiltrating

CD8+ T cells was observed in HCC tumors treated with

sorafenib combined with either α-IL-33 or α-ST2L neutralizing

antibodies compared with other treatment groups. Furthermore, a

reduction in CTLA4 expression on tumor-infiltrating CD8+

T cells was observed in HCC tumors following treatment with α-IL-33

or α-ST2L neutralizing antibodies (Fig.

4G). These findings suggested that combining sorafenib

treatment with α-IL-33 or α-ST2L neutralizing antibodies enhances

the activation and infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the

TME of HCC tumors, leading to increased therapeutic efficacy of

sorafenib.

α-IL-33 neutralizing antibodies

enhancing the antitumor activity of sorafenib depend on T

cells

Since it was observed that combining sorafenib with

an α-IL-33 antibody increased tumor-infiltrated T cells, it was

examined whether the α-IL-33 neutralizing antibody enhances the

antitumor activity of sorafenib through T cells. To test this

hypothesis, an HCC model in nude mice was established by

subcutaneously implanting ML-15a cells and then treating

them with either sorafenib alone or in combination with the α-IL-33

neutralizing antibody (Fig. 5A).

The results showed that the combined treatment did not

significantly reduce tumor size, growth rate, or tumor weights in

the HCC-bearing nude mice compared with the sorafenib-only group

(Fig. 5B-D). In Fig. 5C, the largest tumor had a length of

1.3 cm and a width of 1.3 cm, corresponding to a calculated volume

of 1,098.5 mm3. These data suggested that the α-IL-33

neutralizing antibody enhances the antitumor activity of sorafenib

by regulating T cell-mediated immunity.

Discussion

When cells experience stress or damage, IL-33 is

rapidly released into the cytoplasm, where it serves as an alarmin

by binding to ST2L. This IL-33/ST2L interaction has been shown to

promote cancer progression, while its role in regulating tumor cell

resistance to therapy is just beginning to be investigated. IL-33

has been found to facilitate resistance to Fluorouracil (5-FU) in

murine melanoma cells by triggering polyploidy and inducing immune

exhaustion (40). Our previous

study consistently revealed that IL-33, which is released from lung

cancer cells treated with cisplatin, enhances M2 macrophage

function, thereby limiting the efficacy of the treatment (28). Additionally, a current study

demonstrated that the IL-33/ST2L axis can activate the

non-homologous end joining pathway, contributing to DNA damage

resistance in lung cancer response to cisplatin or doxorubicin

(41). In line with these findings,

it was demonstrated that IL-33 plays a significant role in

enhancing resistance to the anticancer drugs sorafenib and

regorafenib in HCC. Taken together, these results suggest that

targeting the IL-33/ST2L pathway could be beneficial in improving

the effectiveness of these treatments. While IL-33 can be released

from non-necrotic HCC cells in response to sorafenib and

regorafenib, little is known about how it is mobilized and released

into the extracellular space. Recently, several mechanisms based on

non-classical secretion appear to be involved in IL-33 secretion.

It has been found that IL-33 can be cosecreted with exosomes

through the neutral sphingomyelinase-2-dependent multivesicular

endosome pathway in primary human airway basal cells (42). Additionally, current studies

demonstrated that IL-33 release from allergen-stimulated lung

epithelial cells and senescent hepatic stellate cells depends on

gasdermin D pores, whose generation is independent of or dependent

on caspase-1 and caspase-11, respectively (27,43).

Understanding whether IL-33 release from sorafenib- and

regorafenib-treated HCC cells occurs via gasdermin D pores or

exosomal pathways will be important in future studies.

Numerous chemotherapeutic drugs can induce

senescence in cancer cells and TME, stimulating immunosurveillance

to eliminate tumor cells. However, they can also lead to chronic

inflammation and drug resistance, primarily through a set of

factors known as senescence-associated secretory phenotypes

(SASPs), including pro-inflammatory IL-1 family cytokines (44). In fact, as one of the IL-1 family

cytokines, IL-33 has currently been observed in SASPs. For example,

IL-33 is released from senescent hepatic stellate cells as the

SASPs to promote obesity-associated HCC (27). In radiation-induced skin injury,

IL-33 secreted by senescent skin cells inhibits macrophage

phagocytosis ability to clear these cells (45). Furthermore, IL-33-induced cellular

senescence results in kidney cell damage through the secretion of

IL-33-containing SASPs (46). Based

on these studies, the present findings suggested that treatments

with sorafenib and regorafenib induce cellular senescence in HCC

cells and release IL-33 as part of an SASP, which ultimately limits

the effectiveness of these drugs. To further investigate the

interaction between IL-33 and other SASP factors, the secretion of

IL-6, a prominent SASP cytokine, was measured in sorafenib- and

regorafenib-treated Huh7 cells. However, it was found that IL-6

levels were below the detection threshold in all groups, indicating

that IL-6 might not play a significant role as a SASP factor

interacting with IL-33 in our model (Fig. S2). Nevertheless, the potential for

IL-33 to cross-talk with other components of the SASPs cannot be

ruled out.

Overexpression of PD-L1 is observed in

sorafenib-resistant HCC cells and tissues, which is linked to the

facilitation of sorafenib resistance (47). Research using sorafenib-resistant

HCC cell lines has demonstrated that c-Met upregulates PD-L1

through the MAPK/NF-κB p65 signaling cascade, thereby contributing

to sorafenib resistance (48). The

elevated levels of PD-L1 can activate the STAT3/DNA

methyltransferase 1 pathway to trigger sorafenib resistance or

promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in these resistant

HCC cell lines (49,50). However, upregulation of PD-L1 is

also observed in non-resistant HCC cells upon sorafenib exposure.

For example, the induction of PD-L1 and EMT in sorafenib-treated

non-resistant HCC cells is reported, while combined inhibition of

EMT and PD-L1 enhances the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib

(51). In the present study, it was

observed that IL-33 mediates the upregulation of PD-L1 in

non-resistant HCC cells when exposed to sorafenib and regorafenib.

These observations collectively suggest an early induction of PD-L1

expression in HCC cells following these drug treatments.

Additionally, our mechanistic study identified a positive feedback

loop involving the IL-33/ST2L/NF-κB axis, which contributes to the

induction of PD-L1 in HCC cells. Our findings are consistent with

earlier observations that IL-33 promotes PD-L1 expression in murine

acute myeloid leukemia and oral squamous cell carcinoma (36,52).

Importantly, the analysis of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas data

on Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma revealed a significant positive

correlation between IL33 and CD274 mRNA expression

(Spearman's rho=0.349, P=4.78×10−12) (Fig. S3). This finding supports the

observations of the present study that IL-33 may play a role in

inducing PD-L1 upregulation in human HCC. Notably, tumor stromal

cells, in addition to tumor cells, have also been shown to produce

IL-33. Research has revealed that both IL-33 and its receptor ST2

are highly expressed in the microvascular vessels of the TME in

colorectal cancer to regulate tumor angiogenesis and progression

(53). Cancer-associated

fibroblast-derived IL-33 can promote breast cancer cell metastasis

by modifying the immune microenvironment at the metastatic niche

toward type 2 inflammation (54).

Thus, the current findings do not exclude the possibility of IL-33

produced by tumor-stromal cells due to sorafenib and

regorafenib.

The present findings revealed that blocking the

IL-33 signaling pathway with anti-IL-33 or anti-ST2L antibodies

alongside sorafenib significantly reduced tumor growth in mice with

HCC. Notably, this enhanced effect was abolished in athymic nude

mice. This suggests that IL-33 promotes the acquired resistance to

sorafenib in HCC-bearing mice mainly by regulating immune responses

rather than directly affecting HCC cell growth. In fact,

accumulated evidence has revealed that the IL-33/ST2 signaling

pathway is a potent regulator of the TME. It recruits various

immune cell populations that can either promote tumor malignancy or

induce tumor regression. This occurs by activating suppressor

immune cells, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAM),

regulatory T cells (Tregs), and CD4+ Th2 cells, to

inhibit antitumor immunity. Consequently, this pathway plays a

significant role in tumor growth and metastasis (55). Notably, current research indicates

that sorafenib treatment results in the polarization of TAM into M2

macrophages and promotes Treg differentiation, consequently

suppressing the immune response and diminishing the efficacy of

sorafenib to HCC (56,57). It will be important in future

studies to understand whether IL-33 activates TAM and Tregs to

trigger immunosuppressive responses and hence reduce the efficacy

of sorafenib and regorafenib to HCC.

HCC is a primary liver cancer that is increasingly

common. For patients with advanced HCC, targeted therapies such as

sorafenib and regorafenib are recommended. While these treatments

can improve survival rates for patients with HCC, the development

of acquired resistance often leads to a poor response to these

therapies. In the present study, it was revealed that treatments

with sorafenib and regorafenib initiate a positive feedback loop

involving IL-33 and ST2L in senescent HCC cells. The IL-33 that is

secreted enhances the expression of PD-L1 in HCC cells by

activating NF-κB pathways in response to these treatments. When the

IL-33 signaling pathway was blocked using anti-IL-33 or anti-ST2L

antibodies in combination with sorafenib, a significant reduction

in tumor growth was observed in mice with HCC. This was accompanied

by decreased PD-L1 expression in tumors and increased infiltration

of CD8+ T cells. Importantly, the enhanced efficacy of

sorafenib against HCC by inhibiting IL-33 was dependent on T cells.

The present findings suggested that IL-33 may diminish the

effectiveness of sorafenib and regorafenib, indicating that

targeting the IL-33/ST2L axis could improve therapeutic outcomes

for HCC. Future studies should extend these findings by evaluating

the efficacy and toxicity of IL-33/ST2L inhibitors in higher-order

animal models and by investigating their use in combination with

other HCC therapies, such as immunotherapy. These approaches will

be essential to determine the translational potential of targeting

the IL-33/ST2L axis in HCC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Ministry of Science and

Technology of Taiwan (grant nos. MOST 109-2622-B-006-002-CC1 and

MOST 110-2622-B-006- 006-CC1), the National Science and Technology

Council of Taiwan (grant no. NSTC 112-2320-B-006-047) and Chia-Yi

Christian Hospital (grant no. CYC111005).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YXL and HL confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. YXL, HL, CCC and CPC were responsible for study conception

and design, and methodology development. YXL, WCL and BCZ performed

the experiments and collected the data. WCL, BCZ, CCC and CPC

carried out data analysis and interpretation. YXL, HL, WCL, CCC and

CPC wrote and/or revised the manuscript. YCW and SWW provided

administrative, technical, or material support and critical

revisions. CCC and CPC conducted project administration and overall

supervision. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures followed institutional guidelines and

were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of

National Cheng Kung University (approval no. 107130; Tainan,

Taiwan).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Yang C, Zhang H, Zhang L, Zhu AX, Bernards

R, Qin W and Wang C: Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

20:203–222. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega

J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, Kelley RK, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V,

Salem R, et al: BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and

treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 76:681–693.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, Wilkie D,

McNabola A, Rong H, Chen C, Zhang X, Vincent P, McHugh M, et al:

BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and

targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases

involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res.

64:7099–7109. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Schroeder B, Li Z, Cranmer LD, Jones RL

and Pollack SM: Targeting gastrointestinal stromal tumors: The role

of regorafenib. Onco Targets Ther. 9:3009–3016. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mody K and Abou-Alfa GK: Systemic therapy

for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in an evolving landscape.

Curr Treat Options Oncol. 20:32019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S,

Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, et al: Efficacy and safety of

sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 10:25–34. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liu S, Du Y, Ma H, Liang Q, Zhu X and Tian

J: Preclinical comparison of regorafenib and sorafenib efficacy for

hepatocellular carcinoma using multimodality molecular imaging.

Cancer Lett. 453:74–83. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Huang A, Yang XR, Chung WY, Dennison AR

and Zhou J: Targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 5:1462020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ladd AD, Duarte S, Sahin I and Zarrinpar

A: Mechanisms of drug resistance in HCC. Hepatology. 79:926–940.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhang W, Hong X, Xiao Y, Wang H and Zeng

X: Sorafenib resistance and therapeutic strategies in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1880:1893102025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Goodman A, Patel SP and Kurzrock R:

PD-1-PD-L1 immune-checkpoint blockade in B-cell lymphomas. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 14:203–220. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yan F, Pang J, Peng Y, Molina JR, Yang P

and Liu S: Elevated cellular PD1/PD-L1 expression confers acquired

resistance to cisplatin in small cell lung cancer cells. PLoS One.

11:e01629252016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bishop JL, Sio A, Angeles A, Roberts ME,

Azad AA, Chi KN and Zoubeidi A: PD-L1 is highly expressed in

enzalutamide resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 6:234–242.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li D, Sun FF, Wang D, Wang T, Peng JJ,

Feng JQ, Li H, Wang C, Zhou DJ, Luo H, et al: Programmed death

ligand-1 (PD-L1) regulated by NRF-2/MicroRNA-1 regulatory axis

enhances drug resistance and promotes tumorigenic properties in

sorafenib-resistant hepatoma cells. Oncol Res. 28:467–481. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kikuchi H, Matsui A, Morita S, Amoozgar Z,

Inoue K, Ruan Z, Staiculescu D, Wong JSL, Huang P, Yau T, et al:

Increased CD8+ T-cell infiltration and efficacy for multikinase

inhibitors after PD-1 blockade in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl

Cancer Inst. 114:1301–1305. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shigeta K, Matsui A, Kikuchi H, Klein S,

Mamessier E, Chen IX, Aoki S, Kitahara S, Inoue K, Shigeta A, et

al: Regorafenib combined with PD1 blockade increases CD8 T-cell

infiltration by inducing CXCL10 expression in hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 8:e0014352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li Q, Han J, Yang Y and Chen Y: PD-1/PD-L1

checkpoint inhibitors in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 13:10709612022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cayrol C and Girard JP: Interleukin-33

(IL-33): A nuclear cytokine from the IL-1 family. Immunol Rev.

281:154–168. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shlomovitz I, Erlich Z, Speir M, Zargarian

S, Baram N, Engler M, Edry-Botzer L, Munitz A, Croker BA and Gerlic

M: Necroptosis directly induces the release of full-length

biologically active IL-33 in vitro and in an inflammatory disease

model. FEBS J. 286:507–522. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cayrol C and Girard JP: IL-33: An alarmin

cytokine with crucial roles in innate immunity, inflammation and

allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 31:31–37. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cayrol C: IL-33, an alarmin of the IL-1

family involved in allergic and non allergic inflammation: Focus on

the mechanisms of regulation of its activity. Cells. 11:1072021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Weber A, Wasiliew P and Kracht M:

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Sci Signal. 3:cm12010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Griesenauer B and Paczesny S: The

ST2/IL-33 axis in immune cells during inflammatory diseases. Front

Immunol. 8:4752017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Pisani LF, Teani I, Vecchi M and

Pastorelli L: Interleukin-33: Friend or foe in gastrointestinal

tract cancers? Cells. 12:14812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhao R, Yu Z, Li M and Zhou Y:

Interleukin-33/ST2 signaling promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cell

stemness expansion through activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase

pathway. Am J Med Sci. 358:279–288. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang W, Wu J, Ji M and Wu C: Exogenous

interleukin-33 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth by

remodelling the tumour microenvironment. J Transl Med. 18:4772020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yamagishi R, Kamachi F, Nakamura M,

Yamazaki S, Kamiya T, Takasugi M, Cheng Y, Nonaka Y, Yukawa-Muto Y,

Thuy LTT, et al: Gasdermin D-mediated release of IL-33 from

senescent hepatic stellate cells promotes obesity-associated

hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Immunol. 7:eabl72092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang YE, Hu MH, Zeng YC, Tseng YL, Chen

YY, Su WC, Chang CP and Wang YC: IL-33/NF-κB/ST2L/Rab37

positive-feedback loop promotes M2 macrophage to limit

chemotherapeutic efficacy in lung cancer. Cell Death Dis.

15:3562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen SH, Hu CP, Lee CK and Chang C: Immune

reactions against hepatitis B viral antigens lead to the rejection

of hepatocellular carcinoma in BALB/c mice. Cancer Res.

53:4648–4651. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q,

Li B and Liu XS: TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells. Nucleic Acids Res 48 (W1). W509–W514. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Pan X, Liu J, Li M, Liang Y, Liu Z, Lao M

and Fang M: The association of serum IL-33/ST2 expression with

hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 23:7042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Akimoto M, Hayashi JI, Nakae S, Saito H

and Takenaga K: Interleukin-33 enhances programmed oncosis of

ST2L-positive low-metastatic cells in the tumour microenvironment

of lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 7:e20572016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang C, Wang H, Lieftink C, du Chatinier

A, Gao D, Jin G, Jin H, Beijersbergen RL, Qin W and Bernards R:

CDK12 inhibition mediates DNA damage and is synergistic with

sorafenib treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 69:727–736.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Roger L, Tomas F and Gire V: Mechanisms

and regulation of cellular senescence. Int J Mol Sci. 22:131732021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhao M, He Y, Zhu N, Song Y, Hu Q, Wang Z,

Ni Y and Ding L: IL-33/ST2 signaling promotes constitutive and

inductive PD-L1 expression and immune escape in oral squamous cell

carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 128:833–843. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lin X, Kang K, Chen P, Zeng Z, Li G, Xiong

W, Yi M and Xiang B: Regulatory mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 in

cancers. Mol Cancer. 23:1082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Jian C, Fu J, Cheng X, Shen LJ, Ji YX,

Wang X, Pan S, Tian H, Tian S, Liao R, et al: Low-dose sorafenib

acts as a mitochondrial uncoupler and ameliorates nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis. Cell Metab. 31:12062020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shiau DJ, Kuo WT, Davuluri GVN, Shieh CC,

Tsai PJ, Chen CC, Lin YS, Wu YZ, Hsiao YP and Chang CP:

Hepatocellular carcinoma-derived high mobility group box 1 triggers

M2 macrophage polarization via a TLR2/NOX2/autophagy axis. Sci Rep.

10:135822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kudo-Saito C, Miyamoto T, Imazeki H, Shoji

H, Aoki K and Boku N: IL33 is a key driver of treatment resistance

of cancer. Cancer Res. 80:1981–1990. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Luo H, Liu L, Liu X, Xie Y, Huang X, Yang

M, Shao C and Li D: Interleukin-33 (IL-33) promotes DNA

damage-resistance in lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 16:2742025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Katz-Kiriakos E, Steinberg DF, Kluender

CE, Osorio OA, Newsom-Stewart C, Baronia A, Byers DE, Holtzman MJ,

Katafiasz D, Bailey KL, et al: Epithelial IL-33 appropriates

exosome trafficking for secretion in chronic airway disease. JCI

Insight. 6:e1361662021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chen W, Chen S, Yan C, Zhang Y, Zhang R,

Chen M, Zhong S, Fan W, Zhu S, Zhang D, et al: Allergen

protease-activated stress granule assembly and gasdermin D

fragmentation control interleukin-33 secretion. Nat Immunol.

23:1021–1030. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Dong Z, Luo Y, Yuan Z, Tian Y, Jin T and

Xu F: Cellular senescence and SASP in tumor progression and

therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer. 23:1812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Liu G, Chen Y, Dai S, Wu G, Wang F, Chen

W, Wu L, Luo P and Shi C: Targeting the NLRP3 in macrophages

contributes to senescence cell clearance in radiation-induced skin

injury. J Transl Med. 23:1962025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen L, Gao C, Yin X, Mo L, Cheng X, Chen

H, Jiang C, Wu B, Zhao Y, Li H, et al: Partial reduction of

interleukin-33 signaling improves senescence and renal injury in

diabetic nephropathy. MedComm (2020). 5:e7422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang J, Zhao X, Ma X, Yuan Z and Hu M:

KCNQ1OT1 contributes to sorafenib resistance and programmed

death-ligand-1-mediated immune escape via sponging miR-506 in

hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Med. 46:1794–1804.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Xu R, Liu X, Li A, Song L, Liang J, Gao J

and Tang X: c-Met up-regulates the expression of PD-L1 through

MAPK/NF-κBp65 pathway. J Mol Med (Berl). 100:585–598. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Liu J, Liu Y, Meng L, Liu K and Ji B:

Targeting the PD-L1/DNMT1 axis in acquired resistance to sorafenib

in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 38:899–907. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Xu GL, Ni CF, Liang HS, Xu YH, Wang WS,

Shen J, Li MM and Zhu XL: Upregulation of PD-L1 expression promotes

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in sorafenib-resistant

hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 8:390–398.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Shrestha R, Prithviraj P, Bridle KR,

Crawford DHG and Jayachandran A: Combined inhibition of

TGF-β1-induced EMT and PD-L1 silencing re-sensitizes hepatocellular

carcinoma to sorafenib treatment. J Clin Med. 10:18892021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Qin L, Dominguez D, Chen S, Fan J, Long A,

Zhang M, Fang D, Zhang Y, Kuzel TM and Zhang B: Exogenous IL-33

overcomes T cell tolerance in murine acute myeloid leukemia.

Oncotarget. 7:61069–61080. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Cui G, Qi H, Gundersen MD, Yang H,

Christiansen I, Sørbye SW, Goll R and Florholmen J: Dynamics of the

IL-33/ST2 network in the progression of human colorectal adenoma to

sporadic colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 64:181–190.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Shani O, Vorobyov T, Monteran L, Lavie D,

Cohen N, Raz Y, Tsarfaty G, Avivi C, Barshack I and Erez N:

Fibroblast-derived IL33 Facilitates breast cancer metastasis by

modifying the immune microenvironment and driving type 2 immunity.

Cancer Res. 80:5317–5329. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yeoh WJ, Vu VP and Krebs P: IL-33 biology

in cancer: An update and future perspectives. Cytokine.

157:1559612022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yang Q, Cui M, Wang J, Zhao Y, Yin W, Liao

Z, Liang Y, Jiang Z, Li Y, Guo J, et al: Circulating mitochondrial

DNA promotes M2 polarization of tumor associated macrophages and

HCC resistance to sorafenib. Cell Death Dis. 16:1532025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Shen Y, Wang H, Ma Z, Hao M, Wang S, Li J,

Fang Y, Yu L, Huang Y, Wang C, et al: Sorafenib promotes treg cell

differentiation to compromise its efficacy via VEGFR/AKT/Foxo1

signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Mol Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 19:1014542025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|