Introduction

Globally, colorectal cancer (CRC) accounted for

>1.9 million newly diagnosed cases of cancer in 2020, leading to

almost 935,000 fatalities. This accounted for one-tenth of all

cancer cases and deaths (1). While

chemotherapy is the standard treatment for metastatic CRC, the

median overall survival is 20 months (2), and the 5-year survival rate is 12%

(3). These statistics reveal the

need to unravel the molecular basis of treatment resistance and

develop targeted therapies that induce novel forms of programmed

cell death (PCD). Although oncogene activation, a hallmark of tumor

growth, provides cancer cells with benefits, including resistance

to apoptosis and promotion of invasion and metastasis, it also

induces replication stress (RS) (4). Cells have evolved multiple mechanisms

to manage RS, preventing excess activation that could lead to

genomic instability and DNA damage. One such mechanism is

specialized translesion synthesis (TLS), which allows DNA

replication to proceed past damaged sites, thereby avoiding

replication fork failure (5).

In cancer cells, the TLS core factor REV1 (REV1 DNA

directed polymerase (REV1) promotes chemotherapy resistance and

confers a growth advantage by dynamically recruiting Polζ (B-family

DNA polymerase ζ) in an ‘on the fly’ or ‘gap-filling’ process. The

on the fly process is initiated at platinum-induced DNA damage

sites. In this mechanism, the high-fidelity DNA Polδ is

functionally replaced by the error-prone TLS polymerase REV1. REV1

inserts a cytosine opposite a lesion or abasic sites, allowing Polζ

to continue DNA synthesis before switching back to Polδ. This

mechanism enables cancer cells to bypass the DNA damage and

tolerate the toxicity of platinum-based therapy (6–9). The

gap-filling process involves temporary single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)

gaps resulting from the intermittent synthesis of the lagging

strand during DNA replication. In cancer cells, active oncogenes

and RS create numerous ssDNA gaps that often require REV1-Polζ for

repair, given the fast growth rate of these cells (10,11).

Therefore, targeting the REV1-Polζ complex may counteract the

development of resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy. Secondly,

inhibiting TLS without requiring additional chemotherapy drugs may

facilitate the accumulation of ssDNA gaps. These gaps impede the

ability of cancer cells to replicate and proliferate (12), ultimately leading to cell death.

REV1 mRNA levels are upregulated 10.3-fold in CRC

when DNA mismatch repair is inactivated or p53 is lost (13). The transgenic expression of REV1 in

mice accelerates the development of intestinal adenoma, with the

rate of development being directly proportional to the levels of

REV1 expression (14). A pan-cancer

genomic analysis demonstrated an association between low expression

of REV1 and a more favorable prognosis for CRC (15). Furthermore, high REV1 expression is

associated with a poor prognosis in various types of tumor,

including CRC (15). Therefore,

small molecule drugs that specifically target REV1 hold promise for

CRC treatment.

Research by Wojtaszek et al led to the

discovery of JH-RE-06, a novel compound targeting REV1 (16). Combining JH-RE-06 with cisplatin

arrests tumor growth and significantly prolongs survival in mouse

models (16–18), while decreasing cisplatin-induced

mutations and enhancing tumor cell sensitivity. Although these

findings suggest clinical potential, whether REV1 inhibitors exert

unique mechanisms in CRC compared with other cancers remains

unexplored. Unlike the senescence-inducing effects of REV1

inhibitors reported in melanoma and ovarian cancer cells (17), JH-RE-06 uniquely triggers

NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in CRC, which results in increased

levels of the labile iron pool (LIP), inducing ferroptosis.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a cysteine prodrug, effectively rescues

this ferroptotic process. While JH-RE-06 does not increase the

sensitivity of CRC cells to oxaliplatin (OXA), it effectively

suppresses clonal proliferation of OXA-resistant (OXR) cell lines

in vitro and inhibits the growth of OXR xenograft tumors

in vivo. As high REV1 expression in CRC tissues is

significantly associated with poor patient prognosis (15), the selective inhibition of REV1 by

JH-RE-06 to induce ferroptosis offers a potential therapeutic

strategy to overcome apoptosis resistance.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human CRC cell lines HCT116, SW620 (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), and oxaliplatin-resistant HCT116

(OXR-HCT116) (Xiamen Immocell Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) cells were

maintained under standard physiological conditions (37°C, 5%

CO2) using basal DMEM (cat. no. G4511) enriched with 10%

FBS (cat. no. G8002) and antibiotic-antimycotic solution (1% v/v;

cat. no. G4003; all Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.).

Expression analysis of REV1 in

CRC

The paired-end RNA sequencing files from The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA, portal.gdc.cancer.gov, accession no.

phs000178.v11.p8) for 649 colorectal tumors [colon adenocarcinoma

(COAD) n=456, READ n=193; COAD: colon adenocarcinoma; READ: rectal

adenocarcinoma) were subjected to quality control. Reads were

aligned using STAR (v2.7.10b (19)). Gene expression differences between

paired and unpaired datasets were analyzed using R (version 4.2.1,

R Foundation for Statistical Computing, r-project.org/). Data

visualization was performed with ggplot2 (version 3.4.4,

ggplot2.tidyverse.org/), and receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curves were generated using pROC (version 1.18.4, http://cran.r-project.org/package=pROC).

Prognostic analysis of gene expression in CRC (GSE17536 and

GSE17537) was conducted with PrognoScan (https://dna00.bio.kyutech.ac.jp/PrognoScan/). CRC

tissue microarrays (93 tissue cores, 37 paired adjacent

non-cancerous and cancer tissue samples, 19 metastatic samples)

were obtained from Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd (cat. no.

T21-1063). Antigen retrieval was performed with 3%

H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature.

Following blocking with 5% normal donkey serum (cat. no. G1217-5ML,

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 30

min, tissue sections were probed with REV1-specific primary

antibody (cat. no. AB5088; Abcam, 1:250) at 4°C overnight.

Following thorough PBS washing, they were treated with

HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (cat. no. a0181, Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology; 1:250; room temperature, 45 min)

followed by DAB staining (5 min, room temperature). Counterstaining

with 0.5% Mayer's hematoxylin was then performed (room temperature,

5 min), after which the sections were dehydrated through graded

ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted with resin. Stained

sections were observed via light microscope (Nikon Eclipse E100).

REV1 positive rates were analyzed using ImageJ 1.49v (National

Institutes of Health, NIH).

Inhibitors

The following inhibitors were used at 37°C under 5%

CO2 JH-RE-06 (cat. no. HY-12621; 0.5–5.0 µM, 24 or 72 h

treatment; deferoxamine (DFO; cat. no. HY-B1625; 100 or 200 µM, 24

h; Z-VAD-FMK (cat. no. HY-16658B): 5 or 10 µM, 24 h; necrostatin-1

(cat. no. HY-15760): 5 or 10 µM, 24 h; chloroquine (cat. no.

HY-17589A): 10 or 20 µM, 24 h; N-acetylcysteine (cat. no. HY-B0215;

all MedChemExpress): 15 or 20 mM, 24 h; L-penicillamine (cat. no.

196312; 100 mM, 24 h treatment; and 2-mercaptoethanol (cat. no.

M3148; both Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA): 2 mM, 24 h treatment.

RNA interference

Transfection was performed when 2×105

HCT116 cells in the six-well plate reached 60% confluency. For

liposomal transfection complex formation, 15 µl Lipofectamine™ 3000

(cat. no. L3000001, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was mixed with

250 µl Opti-MEM™ reduced serum medium (cat. no. 31985070, Gibco)

and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. A total of 15 µl small

interfering (si) RNA [ATG7 (Autophagy-related gene 7) RNA I (cat.

no. 6604, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., sequences not

available), NCOA4-targeting and scramble siRNA (sequences provided

in Table I; Tsingke Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.)] at a final concentration of 50 nM was separately

diluted in 250 µl Opti-MEM reduced serum medium. Each siRNA diluent

was mixed with the Lipofectamine™ 3000-Opti-MEM™ mixture, and the

transfection complexes were incubated at room temperature for 20

min. The cells were cultured at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 48

h. followed by western blot analysis to determine the knockdown

efficiency of ATG7 and NCOA4.

| Table I.RNA interference sequences. |

Table I.

RNA interference sequences.

| Target Gene | Primer Name | Sense Sequence

(5′→3′) | Antisense Sequence

(5′→3′) |

|---|

| NCOA4 | NCOA4-01 |

GACCUUAUUUAUCAGCUUA |

UAAGCUGAUAAAUAAGGUC |

|

| NCOA4-02 |

GGAGAACAGUCAGACUUCU |

AGAAGUCUGACUGUUCUCC |

|

| NCOA4-03 |

CCAGGAAGUAUUACUUAAU |

AUUAAGUAAUACUUCCUGG |

| Negative

control | Scramble |

CUAGAUACUAGACUGAUAA |

UUAUCAUCUAGUUAUCUAG |

Tandem mass tags (TMT) proteomic

sequencing

A total of 5×105 HCT116 cells underwent

treatment with DMSO or 3 µM JH-RE-06 for 24 h prior to washing with

PBS and cell harvesting at room temperature. Following

centrifugation at 15,000 g, 4°C for 30 h, the soluble protein

fraction was isolated, and underwent BCA protein quantification

assay. Following concentration normalization (BCA assay: 2 µl

diluted sample/BSA standard in 96-well plate, 200 µl 50:1 Buffer

A/B at 37°C for 30 min, absorbance 562 nm to calculate

concentration; adjusted to uniform level with PBS), samples

underwent tryptic digestion (37°C, overnight), followed by

lyophilization and storage at −80°C. TMTpro reagents (cat. no.

a52047, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were used for peptide

labeling, followed by reverse-phase chromatographic separation.

Agilent 1100 HPLC with Zorbax Extend-C18 column was used: mobile

phases A (2:98 ACN-H2O, pH 10) and B (90:10

ACN-H2O, pH 10), 300 µl/min, 210 nm detection. Eluates

(8–54 min) collected cyclically into tubes, lyophilized, frozen for

MS. The samples were loaded onto an Acclaim PepMap RSLC column (75

µm ×50 cm, RP-C18, Thermo Fisher) for separation at a flow rate of

300 nl/min. Data were analyzed using Proteome discoverer 2.4.1.15

(Thermo Fisher Scientific). Pathway analysis of differentially

expressed proteins was performed using the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes) database (integrated with KEGG annotation

results). The hypergeometric distribution test was applied to

calculate the significance of differential protein enrichment in

each pathway entry, which was represented by the P-value.

Western blotting

A total of 5×105 HCT116 or SW620 cellular

proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer (cat. no. p0013b,

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Protein concentration was

determined using the BCA assay. A total of 30 µg of protein per

lane was resolved via 12% SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto PVDF

membranes (200 mA, 90 min). Following blocking with 5% skimmed milk

at room temperature for 1 h, membranes were probed with primary

antibodies (4°C, overnight) and corresponding secondary antibodies

(1:1,000 dilution, cat. no. zb-2301 for anti-rabbit; cat. no.

zb-2305 for anti-mouse, Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at room temperature

for 90 min, followed visualization using an ECL kit (cat. no.

s6009l, Ue landy). Densitometric analysis was performed using

ImageJ 1.49v (National Institutes of Health). The primary

antibodies were as follows: Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4; cat.

no. 52455), NCOA4 (Nuclear receptor coactivator 4, cat. no. 66849),

FTH1 (Ferritin heavy chain 1, cat. no. 3998), γH2AX (Phosphorylated

histone H2AX, cat. no. 2577), SOD2 (Superoxide dismutase 2, cat.

no. 13141), H2AX (cat. no. 2595), and ATG7 (cat. no. 2631; all

1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). FTL1 (ferritin light

chain 1, cat. no. 84731-7-RR), GCLC (Glutamate-cysteine ligase

catalytic subunit, cat. no. 12601-1-AP; both Proteintech Group,

Inc.), LC3I/II (Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3

I/II, cat. no. 14600-1-AP), p62 (Sequestosome 1, cat. no.

66184-1-Ig), Tubulin (cat. no. 11224-1-AP), and GAPDH (all 1:2,000,

cat. no. 60004-1-Ig, Proteintech Group, Inc.).

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

5×105 HCT116 or SW620 cells treated with

JH-RE-06 (1.5 and 3.0 µM for HCT116 cells, and 1.0 and 1.5 µM for

SW620 cells), or 9 µl DMSO at 37°C for 24 h, then collected and

fixed overnight at 4°C in a fixation solution (cat. no. G1102;

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). This was followed by 2 h

fixation at room temperature using 1% osmium tetroxide in PBS.

Following washing by PBS, samples underwent gradient dehydration

using ethanol and acetone. Samples were embedded in 812 embedding

agent (cat. no. GP2001, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and

acetone. Embedding was performed overnight at 37°C, followed by

polymerization at 60°C for 48 h. Ultrathin sections (60 nm) were

dual-stained: uranyl acetate (5% aqueous solution) at 37°C for 15

min, followed by lead citrate (0.5% aqueous solution) at room

temperature for 15 min, then air-dried and imaged using a Hitachi

HT7700 TE microscope. Mitochondrial numbers were counted, and

autophagic vacuoles with engulfed mitochondria were analyzed using

ImageJ 1.49v (National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence assay

HCT116 cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at

room temperature. Subsequently, 0.5% Triton X-100 was applied for

20 min for permeabilization at room temperature. Finally,

non-specific binding sites were blocked with 10% goat serum (cat.

no. C0265, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 30 min at room

temperature. Following blocking, cells were incubated with γH2AX

primary antibody (cat. no. 2577, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:500)

at 4°C for 16 h, then exposed to fluorescent secondary antibody

(Alexa-Fluor 488; cat. no. ab150077, Abcam; 1:1,000) for 1 h at

room temperature in the dark and finally stained with DAPI using a

1 µg/ml aqueous solution at room temperature for 5 min for nuclear

visualization. Samples were mounted with antifade medium (cat. no.

P0128S, Beyotime) and imaged by confocal microscopy, and image

analysis was performed using NIS-elements viewer 5.21 (Nikon

Instruments, Inc.).

Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 assay

HCT116 or SW620 cells in the logarithmic growth

phase were trypsinized, resuspended in complete DMEM

(5×103 cells/100 µl) and seeded into 96-well plates (100

µl/well). Following 24 h culture at 37°C, the medium was replaced

with medium containing JH-RE-06 (0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 3.0, 5.0 µM),

and cells were cultured at 37°C for 24 or 72 h. CCK-8 reagent (cat.

no. C6005, Us Everbright Inc.) was added (1 h, 37°C in the dark),

and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Clone formation assay

Following 50 µM OXA or 3.0 µM JH-RE-06 treatment (24

h, 37°C), OXR-HCT116 cells were resuspended in DMEM following

trypsin digestion to prepare a cell suspension; subsequent cell

counting was performed, and the cells were then diluted to the same

density using DMEM. After being plated (1,000, 2,000 and 5,000

cells/well) in 6-well plates and maintained at 37°C for 14 days,

the cultured cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution for

20 min at room temperature, with subsequent PBS washing. Cells were

stained with 0.2% crystal violet for 5 min at room temperature.

Under a light microscope, positive clones (defined as cell

aggregates containing >50 cells) were identified and counted

manually. Then the cloning rate was determined by dividing the

clone count by the initial number of seeded cells.

Ferroptosis assay

5×105 HCT116 cells were treated with 3.0

µM JH-RE-06, and 5×105 SW620 cells were treated with 1.5

µM JH-RE-06 at 37°C for 6, 12 and 24 h, respectively. A assay kits

were used to measure Fe2+ content (Cell Ferrous Iron

Colorimetric Assay kit; cat. no. E-BC-K881-M, Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), malondialdehyde (MDA) levels (MDA

Detection kit; cat. no. KGT003) and glutathione (GSH) content (GSH

Detection kit; cat. no. KGT006, both Jiangsu Kaiji Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Following

3.0 µM JH-RE-06 treatment (24 h, 37°C), 5×105 HCT116

cells were washed with PBS and incubated with FerroOrange

fluorescent probe (cat. no. F374, Dojindo Laboratories Inc.; 1

µmol/l working concentration) at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were washed

again with PBS and imaged using laser confocal microscopy and image

analysis was performed using NIS-Elements Viewer 5.21.

Animal experiment

24 Male BALB/c nude mice (age: 4–5 weeks; initial

weight: 18–22 g; Ningxia Medical University Laboratory Animal

Center) were housed at 25°C, relative humidity at 50%, a 12 h

light/12 h dark cycle, and ad libitum access to sterile standard

rodent chow and filtered water. All methods received approval from

the Laboratory Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee at Ningxia

Medical University Laboratory Animal Center (approval no.

IACUC-NYLAC-2022-022). Each mouse was injected with

5×106 OXR-HCT116 cells into the axilla. After 12 days of

post-injection culture, the mice were randomized into three groups

(n=8 per group based on power analysis) as follows: i) Oxaliplatin

(5 mg/kg, i.p.), ii) JH-RE-06 (1.6 mg/kg, intratumoral) and iii)

DMSO (100 µl, intratumoral), all of which were administered every

48 h to monitor therapeutic effects and recovery. The maximum

volume of the tumor was <2,000 mm3 (volume=π/6×

length × width × height). The maximum tumor volume and diameter

were 1,450 mm3 and 15 mm, respectively. Following 20

consecutive administrations, animals were euthanized with

isoflurane, perfused with PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature (15 min) and organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and

kidney) and tumor samples were collected and measured. Anesthesia

for all surgical and tumor measurement procedures consisted of

isoflurane (5% for induction, 2% for maintenance). Confirmation of

death was established by the absence of a pedal/toe pinch reflex

and the cessation of breathing for ≥1 min.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tumor specimens were prepared by

fixing tissues with 4% paraformaldehyde (4°C, 12 h), embedding in

paraffin, and sectioning into 5 µm-thick slices. Sections were

deparaffinized (xylene/ethanol) and subjected to EDTA-mediated

antigen retrieval (0.01 M EDTA, pH 9.0; 95°C, 5 min). Endogenous

peroxidase was quenched with 3% H2O2 (room

temperature, 10 min). Non-specific binding was blocked with 10%

goat serum (cat. no. C0265, Beyotime; room temperature, 30 min).

Sections were probed with anti-PCNA (cat. no. GB11010-50, Wuhan

Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; 1:500) and Ki-67 (cat. no.

GB111499-100, Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; 1:200)

antibodies (4°C, overnight). Following PBS-T (0.05% Tween-20)

washes, they were treated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG

(cat. no. G1213-100UL, Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.;

1:200; room temperature, 45 min), followed by DAB chromogen

staining (5 min). Then counterstaining with 0.5% Mayer's

hematoxylin (room temperature, 5 min) and mounting. Stained

sections were observed via light microscope (50 µm scale bar; Nikon

Eclipse E100). PCNA/Ki-67 positive rates were analyzed using ImageJ

1.49v (National Institutes of Health).

H&E staining

Mouse organ wax blocks were sequentially

deparaffinized in graded xylene (analytical grade) and dehydrated

in a series of ethanol (70%→80%→95%→100%, v/v). Hematoxylin

staining (working concentration: 0.5%, w/v; cat. no. Y269827,

Beyotime) was performed at room temperature for 5 min, followed by

tap water washing. Differentiation and eosin counterstaining

(working concentration: 0.5%, w/v; cat. no. C0109, Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) were conducted at room temperature for

3 min. After re-dehydration in the above ethanol gradient and

clearing in xylene (analytical grade, room temperature), sections

were mounted with neutral gum and examined under a light microscope

(Nikon Eclipse E100).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

detection

5×105 HCT116 cells were treated with 3.0

µM JH-RE-06 for at 37°C for 24 h. Then, the cells were loaded with

10 µM DCFH-DA (dissolved in serum-free DMEM medium) and incubated

at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Subsequently, cells were washed 3

times with pre-warmed (37°C) PBS. ROS-derived green fluorescence

(488/525 nm) was imaged using a inverted fluorescence microscope.

Image acquisition and fluorescence intensity quantification were

conducted using NIS-Elements Viewer 5.21. ROS levels were

calculated as the mean fluorescence intensity of cells in the

captured fields.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were repeated in triplicate. All

data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.1

(Dotmatics, Inc.), employing one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's post

hoc test. Paired comparisons were performed by Wilcoxon signed-rank

test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

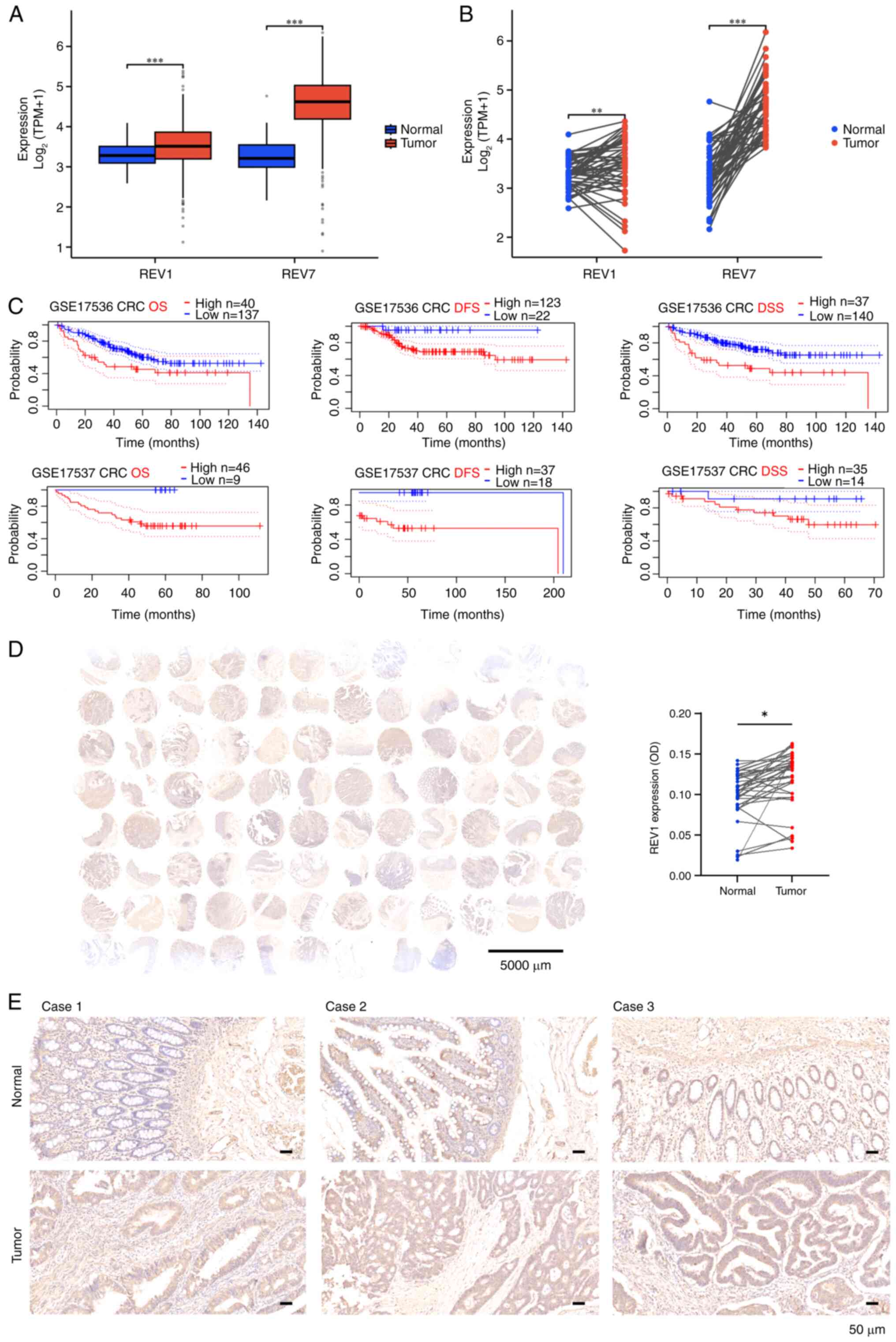

REV1 is upregulated in CRC tissue and

associated with a poor prognosis

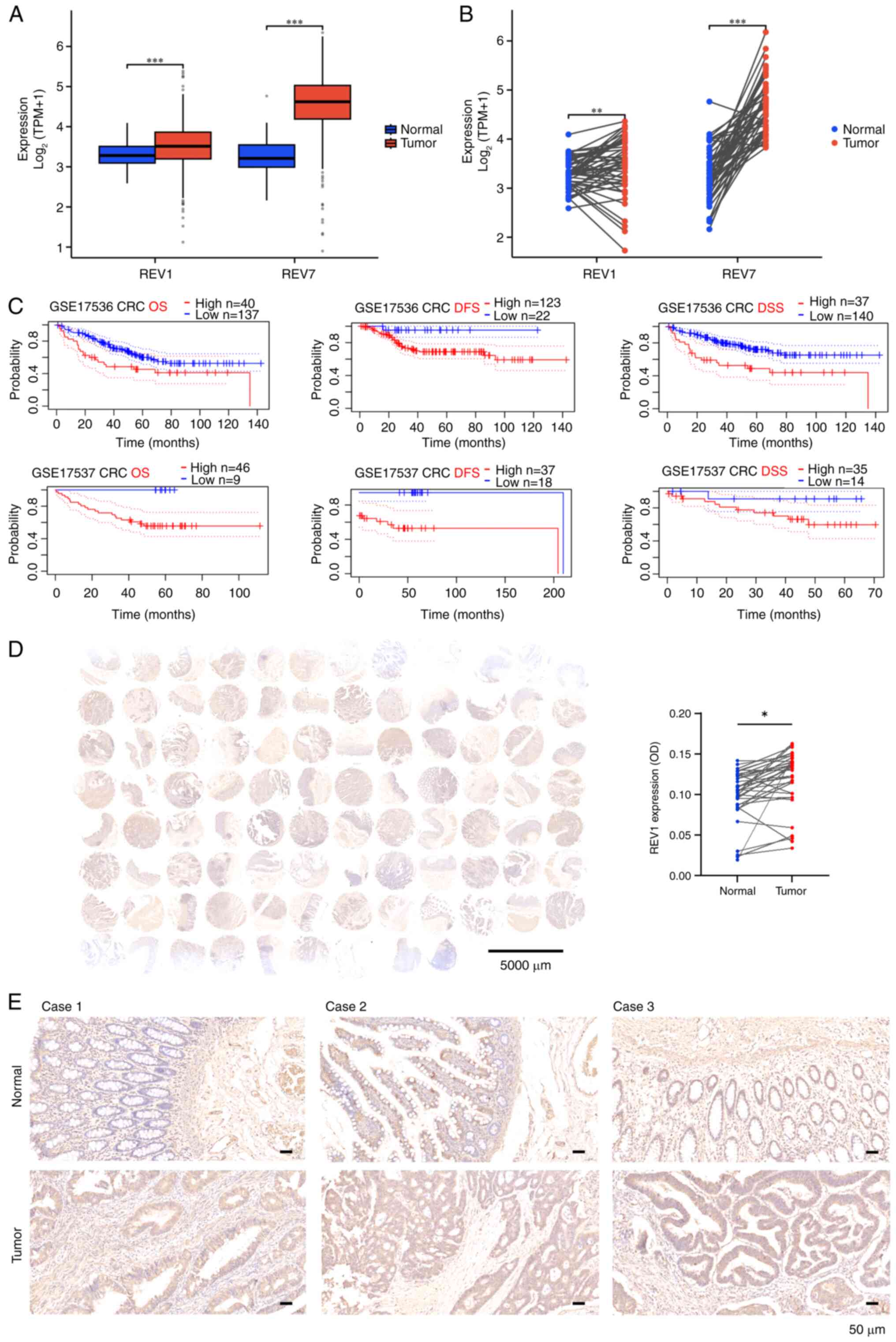

To delineate the role of REV1 in colorectal

carcinogenesis, the present study assessed transcriptomic profiles

from 644 TCGA colorectal adenocarcinoma samples (COAD/READ).

Ggplot2-based analysis demonstrated significantly elevated

expression of both REV1 and REV7 in tumor vs. adjacent normal

tissue, consistent across unpaired (Fig. 1A) and paired sample analyses

(Fig. 1B). The baseline

characteristics of the patients are provided in Table SI. Expression levels were not

significantly associated with clinicopathological parameters,

including sex, age, TNM stage, or perineural invasion. Conversely,

the presence of colon polyps was associated with REV1. Significant

differences were found in lymphatic invasion with respect to REV1

expression (Table SI). The

PrognoScan database was used to assess the association between REV1

expression and CRC prognosis (20).

Analysis of datasets GSE17536 and GSE17537 showed a significant

association between high REV1 expression and poor prognosis

(Fig. 1C). To detect the expression

of REV1, quantitative IHC analysis was performed on 35 paired

specimens using tissue microarrays (Baseline information for CRC

tissue chips is provided in Table

SII). Consistent with TCGA findings, there was a significant

increase in REV1 protein levels in CRC tumors compared with the

paired normal tissues (Fig. 1D and

E). Overall, these findings established high REV1 expression as

a negative prognostic marker in CRC.

| Figure 1.REV1 expression is upregulated in CRC

tissues and associated with poor prognosis. (A) Analysis of 644

unpaired samples from TCGA database revealed elevated expression of

the REV1 and its binding partner REV7 in clinical CRC samples. (B)

Analysis of 50 paired samples from TCGA database showed that REV1

and REV7 were significantly more highly expressed in cancer

compared with adjacent non-cancerous tissue. (C) Prognostic

analysis of REV1 in CRC was performed using PrognoScan database

datasets (accession no. GSE17536/37). (D) REV1 expression levels

were analyzed in 35 paired CRC tissue samples using a tissue

microarray, which revealed significantly elevated REV1 expression

in CRC vs. adjacent normal tissue. (E) Representative

immunohistochemical REV1 staining in CRC tissue. Scale bar, 50 µm.

***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05. REV1, REV1 DNA directed

polymerase; CRC, colorectal cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

TPM, transcripts per kilobase of exon model per million mapped

reads; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; DSS,

disease-specific survival; OD, optical density. |

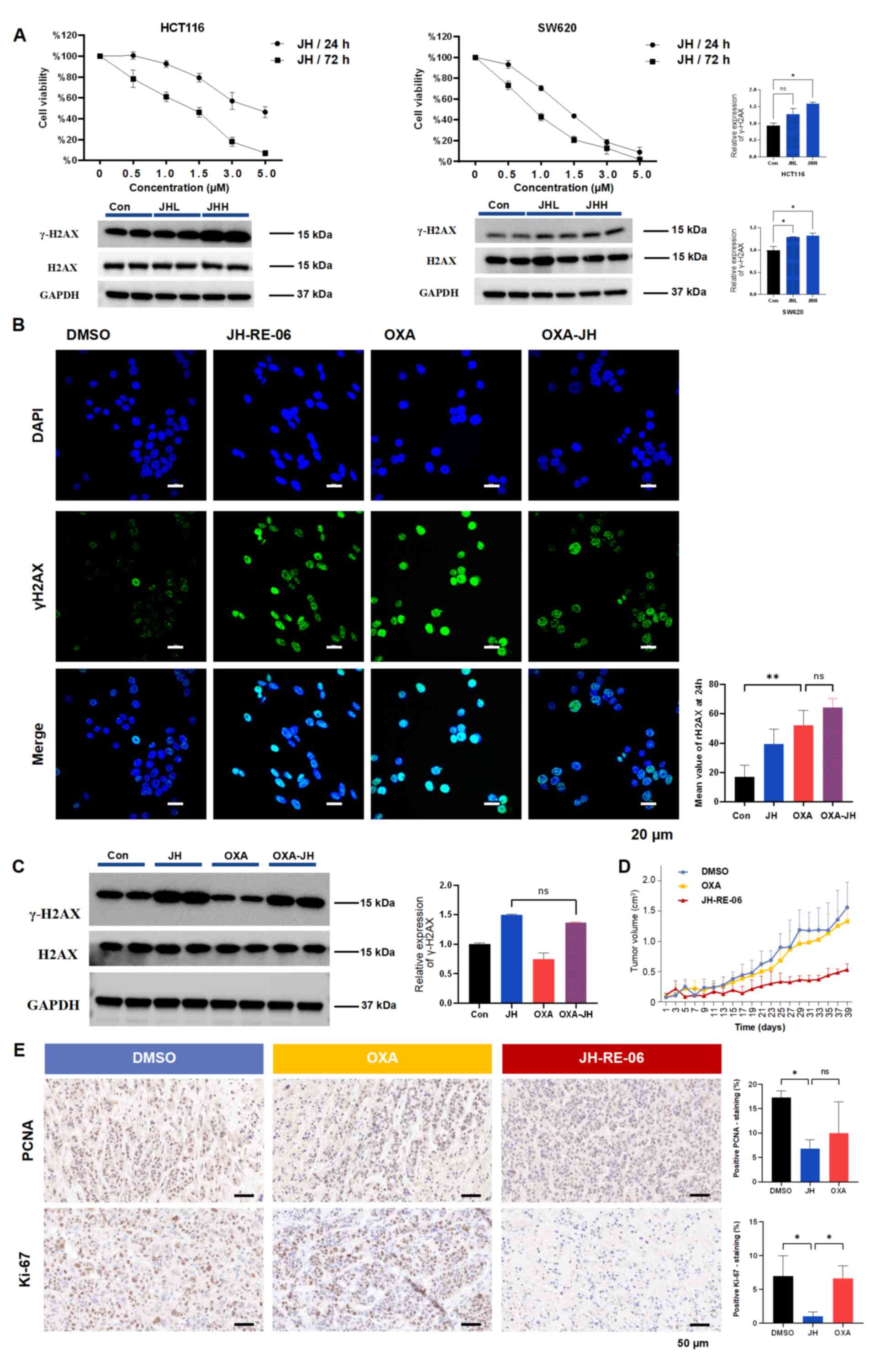

REV1 inhibitor JH-RE-06 suppresses CRC

tumorigenesis both in vitro and in vivo

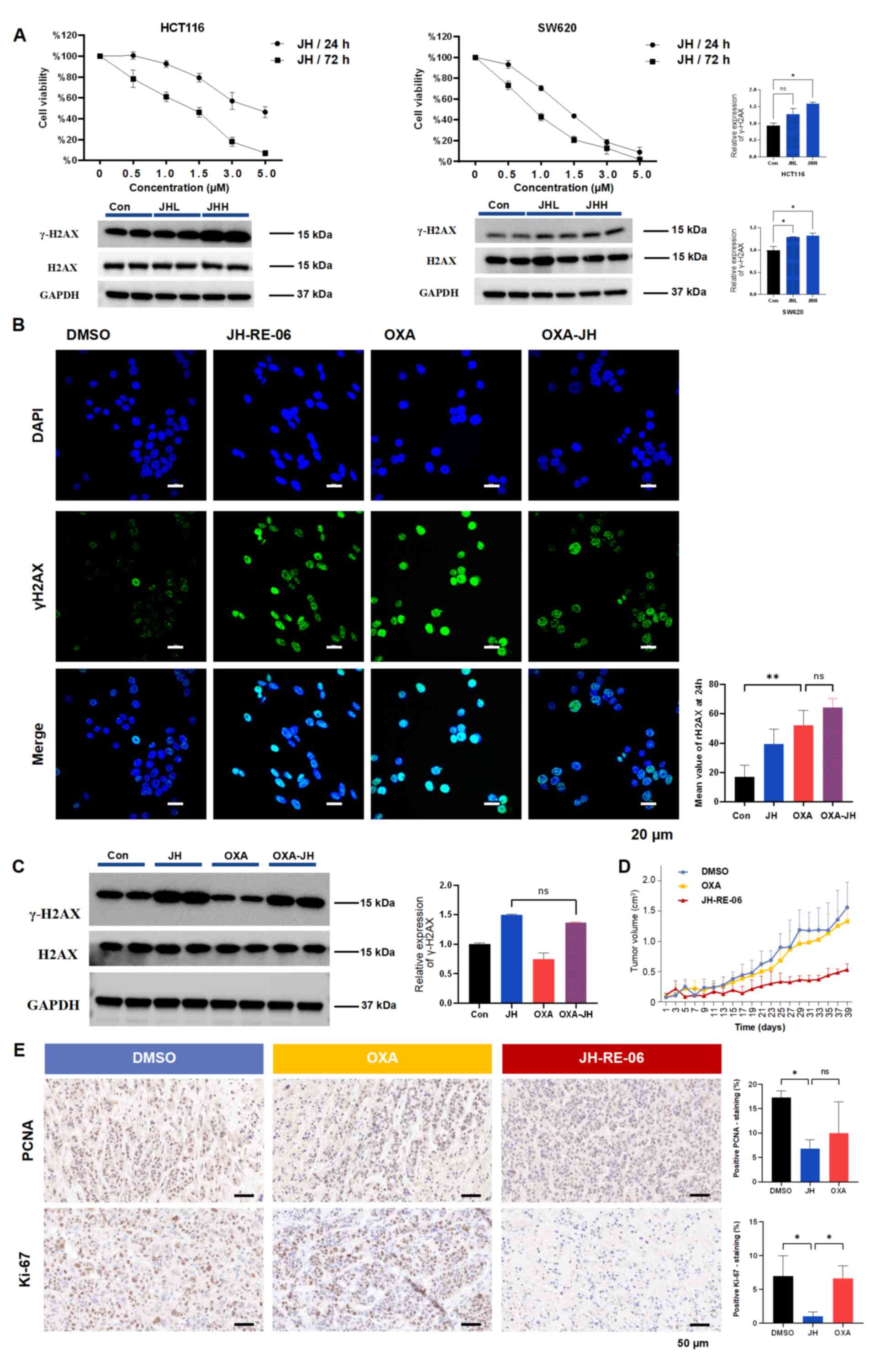

To exploit REV1 as a drug target, the present study

evaluated JH-RE-06, a compound that impairs REV1 function by

inducing inactive dimer formation (16). CCK-8 assay revealed that JH-RE-06

decreased the proliferation of CRC cells in a dose- and

time-dependent manner and induced DNA damage, as indicated by

increased γH2AX levels (Fig.

2A). While JH-RE-06 is hypothesized to enhance tumor cell

sensitivity to platinum-based drugs (21), western blot and immunofluorescence

analysis show that JH-RE-06 did not modify the effect of OXA in

HCT116 cells (Fig. 2B and C). To

assess its efficacy in resistant models, OXR-HCT116 cells were used

(Fig. S1A). Crystal violet

staining demonstrated that JH-RE-06 effectively inhibited the

clonogenic capacity of OXR-HCT116 cells (Fig. S1B). Therapeutic efficacy of

JH-RE-06 was assessed in vivo using a xenograft mouse model

developed with OXR-HCT116 cells (Fig.

S1C). The JH-RE-06 group displayed a substantial reduction in

tumor volume, indicating its effectiveness against OXR malignancies

(Figs. 2D and S1D). Safety of JH-RE-06 was assessed by

hematoxylin and eosin staining of the hearts, livers, spleens, lung

and kidney of treated mice. No notable pathological damage was

observed in these major organs (Fig.

S1E). Immunohistochemistry for proliferation markers Ki67 and

PCNA revealed that JH-RE-06 significantly suppressed tumor growth

and blood vessel formation (Fig.

2E). In summary, the REV1 inhibitor JH-RE-06 induced DNA damage

in CRC cells and inhibited tumor growth both in vitro and

in vivo.

| Figure 2.JH, a REV1 DNA directed polymerase

inhibitor, suppresses CRC tumorigenesis both in vitro and

in vivo. (A) Cell viability assessed by Cell Counting Kit-8

revealed differential sensitivity to JH, with sustained effects

observed at 72 h vs. 24 h in CRC models. WB analysis was used to

detect γH2AX levels in cells treated with JH for 24 h. For HCT116

cells, JHL represents 1.5 and JHH represents 3.0 µM JH. For SW620

cells, JHL represents 1.0 and JHH represents 1.5 µM JH.

Concentrations were selected based on treatments that resulted in

~50% cell viability after 24 or 72 h. GAPDH was used as the

internal control. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of γH2AX in

HCT116 cells treated with 3.0 µM JH and/or 5.0 µM OXA for 12 and 24

h. Scale bar, 20 µm. (C) WB analysis of γH2AX levels after

treatment with JH and/or OXA, with GAPDH as the loading control.

Quantitative analysis revealed no significant differences between

the JH and OXA-JH treatment groups. (D) Tumor growth curves for

OXA-resistant HCT116 cell xenografts in mice. (E) Representative

immunohistochemical images of PCNA and Ki-67 staining in tumor

sections. Scale bar, 50 µm. **P<0.01, *P<0.05. CRC,

colorectal cancer; JHH, JH-RE-06 high; JHL, JH-RE-06 low; WB,

western blot; H2AX, histone H2AX; OXA, oxaliplatin; PCNA,

proliferating cell nuclear antigen; Con, control; ns, not

significant. |

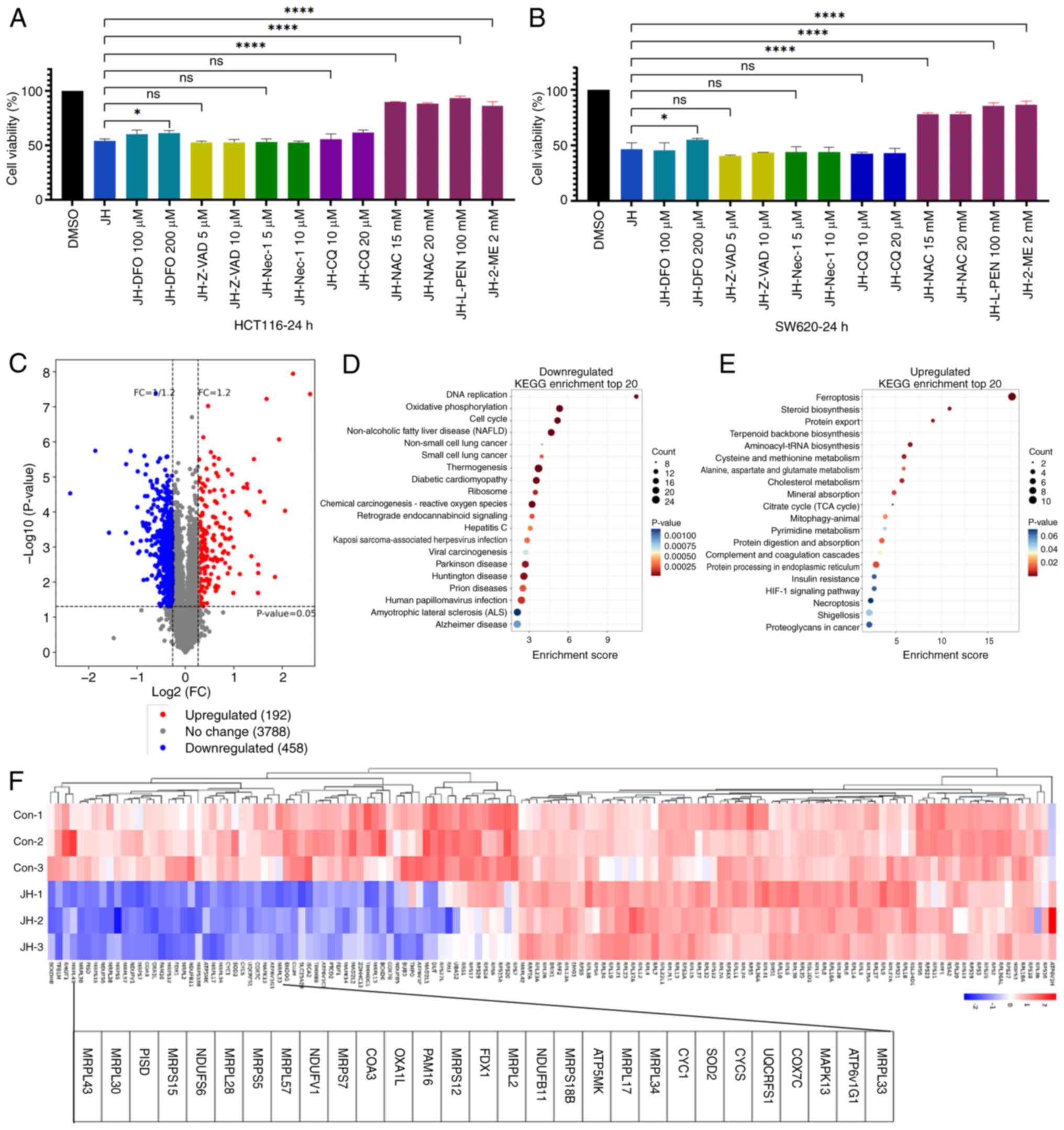

Cell death induced by REV1 inhibition

is associated with oxidative stress and ferroptosis

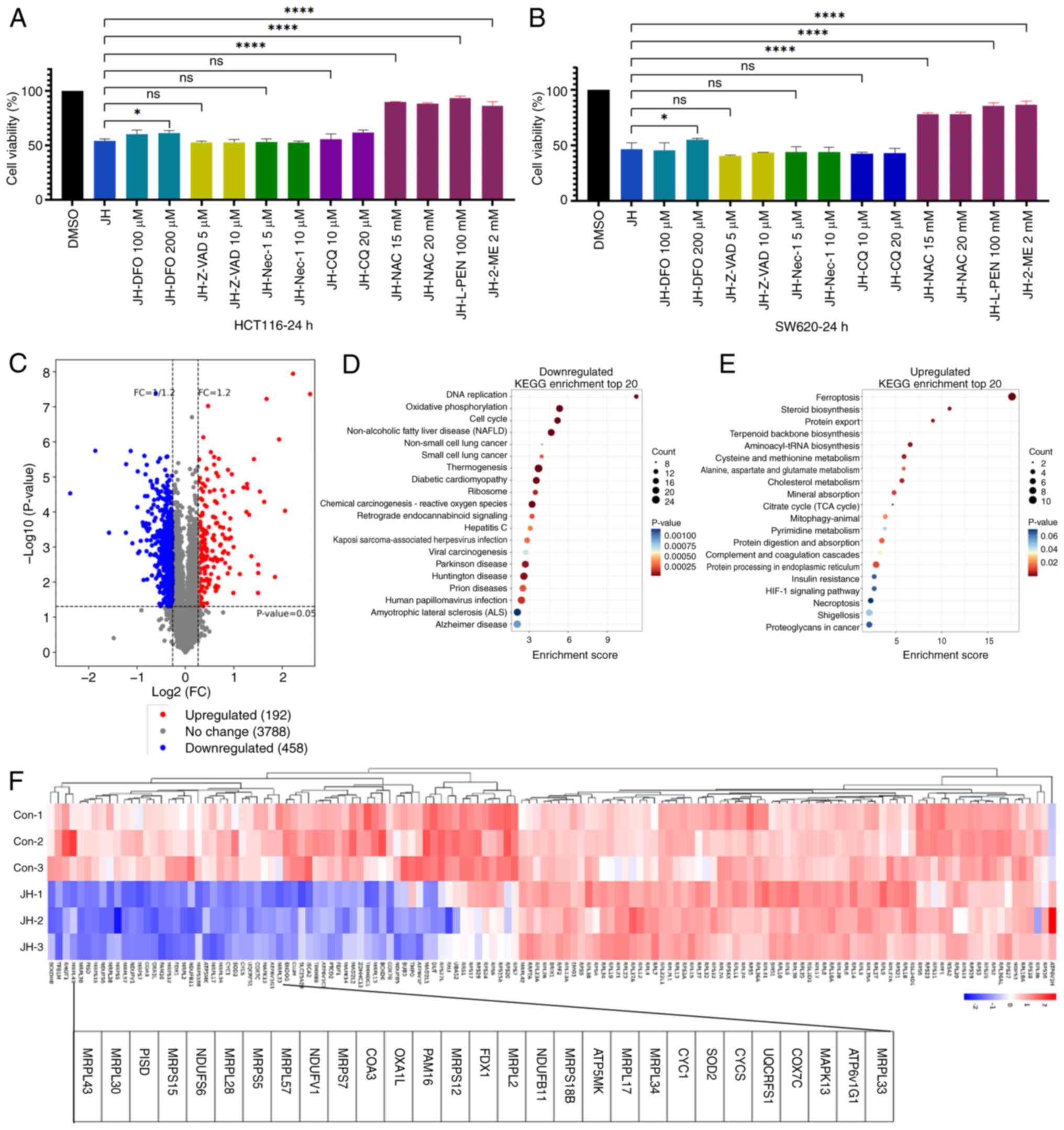

To investigate the mechanism by which JH-RE-06

causes cell death, CRC cells were pre-treated with inhibitors that

target different PCD pathways, such as apoptosis (Z-VAD-FMK),

necroptosis (necrostatin-1), autophagy (chloroquine), ferroptosis

[deferoxamine, DFO), and antioxidants (L-penicillamine,

2-mercaptoethanol, and N-acetylcysteine). CCK-8 assay showed that

DFO partially alleviated JH-RE-06-induced cell death, while

antioxidants almost completely reversed this in both HCT116 and

SW620 cells (Fig. 3A and B). To

investigate global proteomic changes, TMT proteomics was performed

on HCT116 cells treated with DMSO or 3 µM JH-RE-06 for 24 h.

Proteomic analysis revealed 650 significantly altered proteins

following JH-RE-06 treatment (Fig.

3C). Downregulated proteins were predominantly enriched in ‘DNA

replication’, ‘oxidative phosphorylation’, and ‘cell cycle’

(Fig. 3D). Notably, a subset of

these downregulated proteins was also associated with mitochondrial

function, including mitochondrial ribosomal protein small and large

subunits and members of the NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit

family (Fig. 3F). Upregulated

proteins were significantly associated with ‘ferroptosis’ and

oxidative stress pathways, including ‘steroid biosynthesis’,

‘cysteine and methionine metabolism’, and ‘citrate cycle (TCA

cycle)’ (Fig. 3E). These findings

suggested that REV1 inhibition modulated oxidative stress,

mitochondrial function and ferroptosis.

| Figure 3.Cell death induced by REV1 DNA

directed polymerase inhibition is associated with oxidative stress

and ferroptosis. Viability of (A) HCT116 cells treated with 3 µM JH

and (B) SW620 cells treated with 1.5 µM JH in the presence or

absence of inhibitors. (C) Differentially expressed proteins

enriched by proteomics. Compared with the DMSO group, JH

upregulated 192 proteins and downregulated 458 proteins. (D)

Downregulated pathways. The top 20 enriched KEGG pathways are

illustrated. (E) Upregulated pathways. (F) Hierarchical clustering

of differentially expressed mitochondrial-associated genes.

****P<0.0001, *P<0.05. JH, JH-RE-06; KEGG, Kyoto encyclopedia

of genes and genomes; DFO, deferoxamine; Z-VAD, z-vad-fmk; Nec,

necrostatin-1; CQ, chloroquine; NAC, n-acetylcysteine; L-PEN,

l-penicillamine; ME, 2-mercaptoethanol; ns, not significant; Con,

control; FC, fold change; MRPL, mitochondrial ribosomal protein

large subunit; MRPS, mitochondrial ribosomal protein small subunit;

NDUF, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit. |

JH-RE-06 triggers ferroptosis in CRC

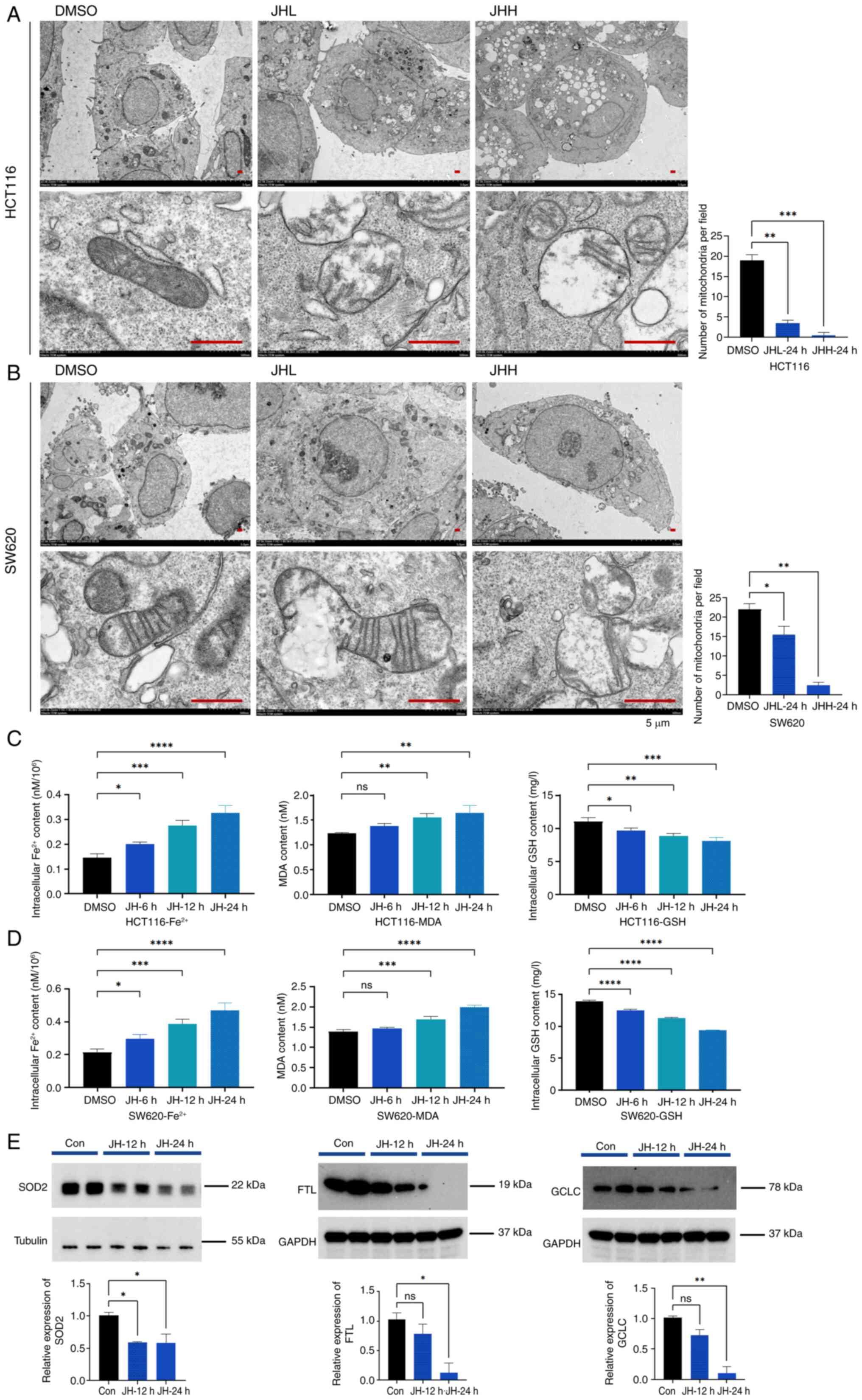

cells

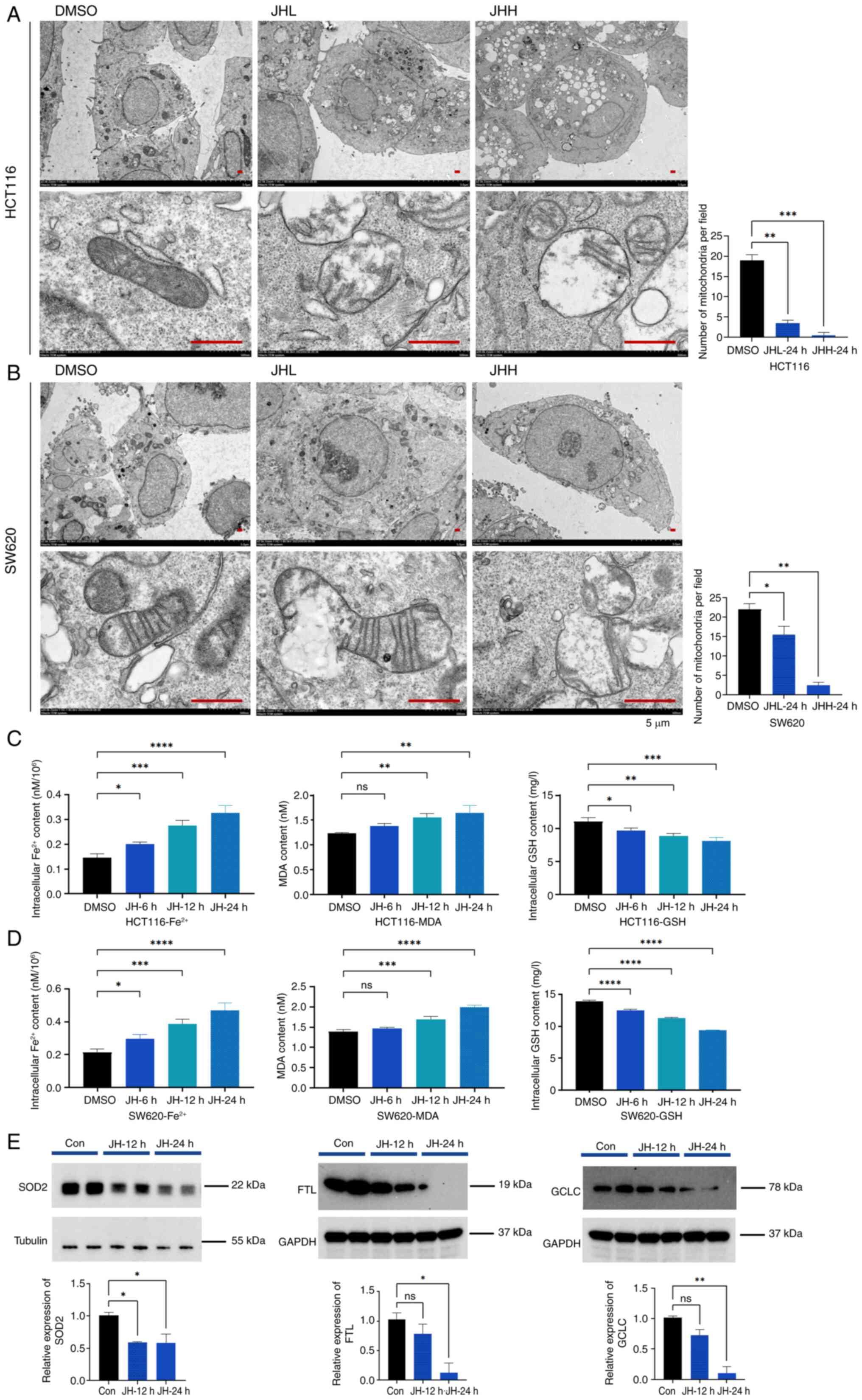

Ferroptosis is characterized by iron-catalyzed lipid

peroxidation and is controlled by mitochondrial activity and LIP

concentrations. Therefore, the present study investigated the

subcellular changes in JH-RE-06-treated CRC cells. TEM revealed a

significant reduction in mitochondrial abundance in both HCT116 and

SW620 cells after 24 h JH-RE-06 treatment (Fig. 4A and B). Autophagic vacuoles

containing engulfed mitochondria were observed (Fig. 4A and B). Intracellular free

Fe2+ levels increased following 6 h treatment, peaking

at 24 h in both HCT116 and SW620 cells (Fig. 4C and D). Concurrently, levels of the

lipid oxidation marker MDA and ROS increased, while GSH levels

decreased over time (Figs. 4C and D

and S2A). These results

collectively indicated that JH-RE-06 induced a time-dependent

increase in Fe2+ and MDA levels, alongside a decrease in

GSH levels. Furthermore, western blot analysis confirmed that the

protein expression levels of mitochondrial (SOD2) and

ferritin-(FTL) and glutathione-related proteins (GCLC) decreased

following treatment with 3.0 µM JH-RE-06. This decrease was

consistent with proteomics findings (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these results

suggest that JH-RE-06 triggered ferroptosis in CRC cells.

| Figure 4.JH triggers ferroptosis in colorectal

cancer cells. Transmission electron microscopy of (A) HCT116 and

(B) SW620 cells treated with JHL and JHH for 24 h show

intracellular vacuolar changes, with mitochondria-like structures

undergoing digestion inside the vacuoles. Scale bar, 5 µm. Changes

in intracellular Fe2+ concentration, MDA and GSH levels

(normalized to total protein) in (C) HCT116 cells treated with 3.0

µM JH and (D) SW620 cells treated with 1.5 µM JH at 6, 12 and 24 h

post-treatment. (E) Relative protein expression levels of SOD2, FTL

and GCLC following 12 and 24 h JH treatment in HCT116 cells; 24 h

exposure to JH resulted in significant downregulation of

antioxidant proteins SOD2, FTL and GCLC. ****P<0.0001,

***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05. JHH, JH-RE-06 high; JHL,

JH-RE-06 low; MDA, malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione; SOD2,

superoxide dismutase 2; FTL, ferritin light chain; GCLC,

glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; ns, not significant;

Con, control. |

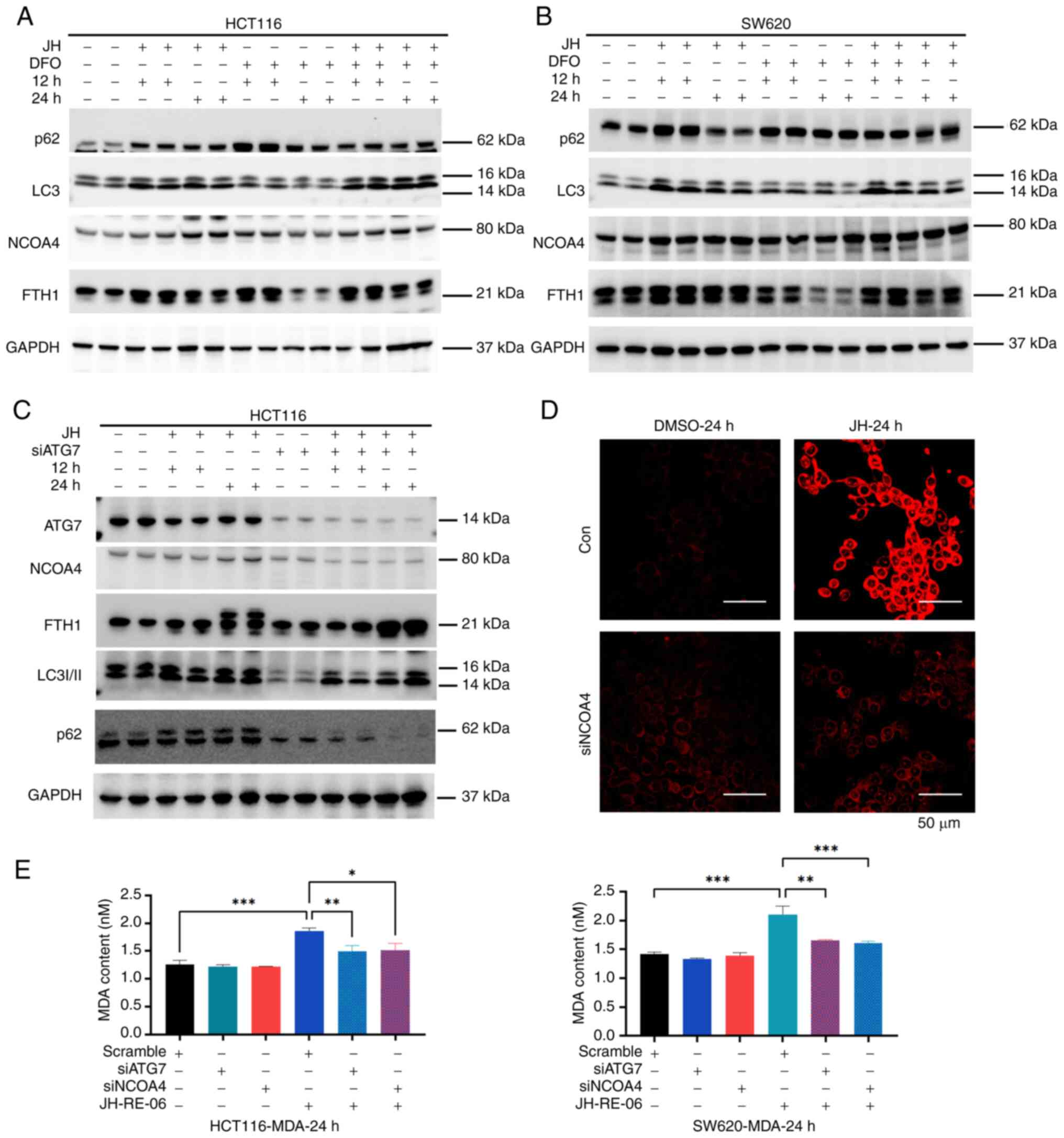

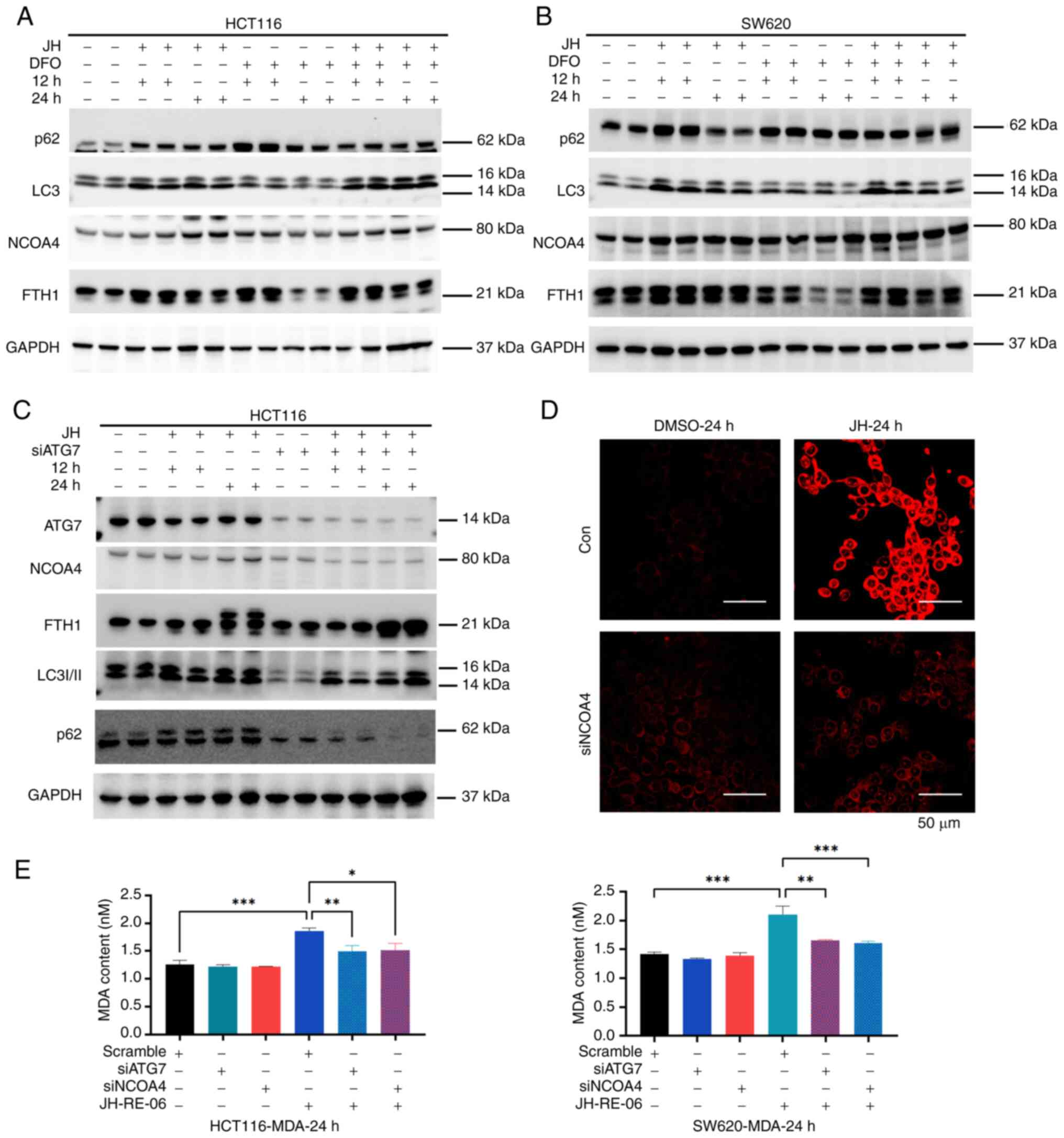

JH-RE-06 triggers ferroptosis via

NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in CRC cells

Ferroptosis represents an iron-catalyzed, lipid

peroxidation-mediated programmed cell death pathway (22). NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy plays a

critical role in ferroptosis by regulating cellular iron

homeostasis (23). Ferritinophagy,

the autophagic degradation of ferritin, increases the LIP, which

promotes ferroptosis (24). CRC

cells are both iron-rich and iron-dependent (25), making the regulation of iron

homeostasis a key factor in CRC progression and therapeutic

resistance (26). Proteomics

sequencing revealed elevated NCOA4 expression and a decrease in its

regulatory proteins, suggesting that NCOA4 is key for modulating

cellular iron levels following JH-RE-06 treatment. Therefore, it

was hypothesized that JH-RE-06 increased the LIP in an

NCOA4-dependent manner, thereby inducing ferroptosis via

ferritinophagy. To validate this hypothesis, the present study

assessed changes in the expression of ferritinophagy-associated

proteins following JH-RE-06 treatment in CRC cells using western

blotting. JH-RE-06 increased the expression of NCOA4, p62 and LC3

at both 12 and 24 h (Figs. 5A and B

and S2B and C). FTH1 expression

increased at 12 but decreased by 24 h. To verify the reliability of

the experimental system, DFO was used to chelate Fe2+

and protein levels of LC3II, NCOA4, and p62 were increased

(Figs. 5A and B). Next, the role of

LIP in mediating the effects of JH-RE-06 was explored by

pre-treating cells with DFO to chelate Fe2+, followed by

JH-RE-06 treatment. In the combination group, NCOA4 expression was

sustained for longer period with the DFO group, and FTH1 levels

were also elevated. To investigate the role of ferritinophagy, ATG7

or NCOA4, key proteins involved in ferritinophagy and

Fe2+ recycling, were silenced before treating the cells

with JH-RE-06 (Fig. S2D). In these

cells, the expression of NCOA4, LC3II, and p62 in response to

JH-RE-06 was partially mitigated (Figs.

5C and S2D), and FTH1, a

substrate for ferritinophagy degradation, accumulated due to

impaired autophagy (Fig. 4C and

S2E). LIP was assessed using the

FerroOrange test. In wild-type HCT116 cells, JH-RE-06 treatment

induced a significant increase in LIP at 24 h, indicating iron

overload. However, in siNCOA4 cells, the JH-RE-06-induced increase

in LIP was not observed at 24 h due to the inhibition of ferritin

degradation. This suggested that the iron overload induced by

JH-RE-06 is dependent on functional NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy

(Fig. 5D). Silencing ATG7 or NCOA4

before JH-RE-06 treatment resulted in decreased MDA levels

(Fig. 5E). Based on these findings,

it was hypothesized that JH-RE-06 induces ferroptosis through

NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy, disrupting iron homeostasis and

promoting lipid peroxidation.

| Figure 5.JH triggers ferroptosis via

NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in colorectal cancer cells. (A)

HCT116 cells were treated with 3.0 µM JH and (B) SW620 cells with

1.5 µM JH and/or 50 µM DFO for 12 and 24 h before WB analysis for

p62, LC3, NCOA4 and FTH1, normalized to GAPDH. (C) WB analysis of

HCT116 cells with or without ATG7 knockout, treated with 3.0 µM JH.

(D) HCT116 cells were transfected with scramble or siNCOA4 for 48

h, then treated with 3.0 µM JH for 24 h. Cells were incubated with

FerroOrange probe and imaged using laser confocal microscopy. Scale

bar, 50 µm. (E) Lipid peroxidation levels were measured in ATG7 and

NCOA4 knockdown cells, as well as wild-type HCT116 and SW620 cells,

treated with JH. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05. JH,

JH-RE-06; NCOA4, nuclear receptor coactivator 4; WB, western blot;

LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; FTH, ferritin

heavy chain; ATG, autophagy-related gene; si, small interfering;

DFO, deferoxamine. |

Discussion

REV1 is implicated in cancer development by enabling

cells to bypass DNA damage, thereby accumulating genetic mutations

and increasing cancer risk (14).

Most CRCs originate from polyps, which progress through abnormal

crypts into neoplastic precursor lesions over 10–15 years (27). The present study highlighted the

clinical value of REV1 in CRC. Bioinformatics analysis and

immunohistochemical staining of tissue microarrays revealed that

high tumoral REV1 expression served as a negative prognostic

indicator. Furthermore, bioinformatics analysis identified a

significant association between high REV1 expression and the

presence of colon polyps, indicating its potential role in early

colorectal tumorigenesis. These findings collectively suggested

that REV1 is a promising therapeutic target for both early

intervention and advanced CRC treatment.

Studies have focused on enhancing cancer cell

sensitivity to platinum-based agents by genetically inhibiting REV1

(6,7). Early studies proposed that REV1

ablation may potentiate OXA efficacy by exacerbating DNA damage and

apoptosis (21,28). However, OXA primarily exerts

cytotoxic effects via ribosome biogenesis stress, independent of

DNA damage mechanisms (29).

Similarly, the present study revealed that pretreatment with the

REV1 inhibitor JH-RE-06 enhanced cellular resistance to OXA or

oncogene-induced (cyclin E overexpression) RS can render cancer

cells hypersensitive to TLS inhibition (11,30).

Clinically, while OXA treatment often leads to drug resistance in

CRC, it generates a therapeutic vulnerability that may be exploited

(31). To validate this hypothesis,

the present study established OXR CRC models. Both clonogenic

assays and xenograft experiments revealed that JH-RE-06 selectively

inhibited OXR cell proliferation while exhibiting minimal toxicity,

positioning it as a promising second-line therapeutic candidate for

refractory CRC.

While previous research has explored the effects of

JH-RE-06 in lung and BRCA1/2-deficient cancer (10,18),

the specific PCD mechanisms remain unclear. The present study

established JH-RE-06 as a DNA-damaging agent that inhibited CRC

cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Pharmacological

rescue experiments revealed that JH-RE-06-induced cell death was

mitigated by cysteine regenerators (L-penicillamine,

2-mercaptoethanol and N-acetylcysteine) and the iron chelator DFO,

suggesting that the cell death mechanism was consistent with

ferroptosis rather than conventional PCD pathways such as

apoptosis, necrosis or autophagy. Ferroptosis is a metabolically

regulated cell death process driven by iron-dependent lipid

peroxidation and compromised redox balance (32). In the present study, proteomics

analysis confirmed that JH-RE-06 promoted cell signaling pathways

associated with ‘DNA replication’, ‘ferroptosis’, and ‘oxidative

phosphorylation’.

JH-RE-06 treatment in CRC cells resulted in

decreased mitochondrial abundance and intracellular GSH levels, and

significant elevations in intracellular Fe2+ and MDA

concentrations, which represent key features of ferroptosis.

Consistent with these findings, REV1 deficiency-induced RS causes

metabolic stress, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction in mouse

embryonic fibroblasts (33).

Studies in REV1−/− mice (a replication stress model)

(21) have demonstrated

sex-dependent metabolic disturbances, underscoring the dual role of

REV1 in DNA stability and metabolic control (34).

The association between REV1 inhibition and

ferroptosis remains incompletely understood. However, emerging

evidence indicates NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy as a key

mechanism, involving iron liberation through ferritin degradation

and RS via minichromosome maintenance protein complex 2–7, helicase

interference (35). JH-RE-06

treatment in wild-type CRC cells significantly upregulated both

autophagy markers (LC3I/II and p62) and ferritinophagy-associated

proteins. This was characterized by increased NCOA4 expression,

decreased FTH1 levels and consequent elevation of LIP. The

experimental system was validated by using DFO to chelate

Fe2+, which demonstrated target protein changes aligned

with prior reports (36,37). By contrast, ATG7 knockout CRC cells

exhibited increased FTH1 levels and no increase in LIP following

JH-RE-06 treatment. Moreover, JH-RE-06-treated autophagy-deficient

CRC cells showed decreased MDA levels, indicating that the

ferroptosis induced by JH-RE-06 may depend on NCOA4-mediated

ferritinophagy. Recent research has highlighted the role of NCOA4

in regulating both DNA replication origins and iron

autophagy-mediated LIP, with potential Fe-S cluster degradation

(38). REV1 protects replication

forks by suppressing their remodeling (11), while NCOA4 regulates DNA replication

origins, preventing RS (39).

However, the precise regulatory association between REV1 inhibition

and NCOA4 remains to be fully elucidated.

Recent studies have indicated the potential of REV1

inhibitors as regulators of cell metabolism for cancer therapy

(40,41). In epithelial ovarian cancer,

fumarate-mediated modulation of TLS may enhance the efficacy of

genotoxic chemotherapy (40). In

pulmonary malignancy, REV1 promotes radioresistance by modulating

amino acid metabolism, specifically via cystathionine γ-lyase

ubiquitination and subsequent disruption of Gly/Ser/Thr metabolic

flux (41). These findings suggest

that the development of more selective REV1 inhibitors may offer

novel therapeutic opportunities, especially when conventional

apoptosis mechanisms are compromised.

The present findings established REV1 as both a

prognostic marker and therapeutic candidate in CRC, with elevated

expression associated with poorer survival. The specific inhibitor

JH-RE-06 induced DNA damage and suppressed tumor cell

proliferation, while also triggering oxidative stress in CRC cells.

JH-RE-06 regulated intracellular iron overload via NCOA4-mediated

ferritinophagy, thereby activating ferroptosis. This led to an

increase in the LIP, contributing to oxidative stress and

initiating ferroptosis, which was reversed by DFO and free radical

scavengers such as NAC. JH-RE-06 effectively inhibited the

proliferation of CRC cells, highlighting its clinical potential as

a therapeutic option for CRC, including both treatment-naive and

chemotherapy-resistant forms.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Ningxia Hui Autonomous

Region Science and Technology Support Program (grant no.

2021BEG03084) and the Ningxia Education Department's Scientific

Research Program (grant no. NYG2024117).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Open Archive for Miscellaneous Data, China National Center

for Bioinformation under accession number OMIX007702 or at the

following URL: ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/release/OMIX007702.

Authors' contributions

JC conceived and designed the study, performed

experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. XY, WZ and JX

performed experiments. FX conceived the study, revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content, and assisted in the

interpretation of key experimental results. XY revised the

manuscript and participated in data analysis. JC and XY confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. YH participated in key

experimental operations (optimization of ROS detection protocols,

paraffin sectioning techniques, as applicable) and verification of

experimental protocols. All authors have read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures adhered to institutional guidelines

and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Ningxia Medical

University Laboratory Animal Center (approval no.

IACUC-NYLAC-2022-022), in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines and

national regulations for humane treatment of animals. The human

tissue microarrays were commercially sourced from fully

de-identified samples previously collected under ethical oversight.

In accordance with international research standards (Declaration of

Helsinki) and institutional policies for the secondary use of

archival specimens, no additional ethical review or consent

procedures were required.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liu Z, Xu Y, Xu G, Baklaushev VP,

Chekhonin VP, Peltzer K, Ma W, Wang X, Wang G and Zhang C: Nomogram

for predicting overall survival in colorectal cancer with distant

metastasis. BMC Gastroenterol. 21:1032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Veenstra CM and Krauss JC: Emerging

systemic therapies for colorectal cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg.

31:179–191. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Berti M, Cortez D and Lopes M: The

plasticity of DNA replication forks in response to clinically

relevant genotoxic stress. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:633–651. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yang W and Gao Y: Translesion and repair

DNA polymerases: Diverse structure and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem.

87:239–261. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hicks JK, Chute CL, Paulsen MT, Ragland

RL, Howlett NG, Gueranger Q, Glover TW and Canman CE: Differential

roles for DNA polymerases eta, zeta, and REV1 in lesion bypass of

intrastrand versus interstrand DNA cross-links. Mol Cell Biol.

30:1217–1230. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sharma S, Hicks JK, Chute CL, Brennan JR,

Ahn JY, Glover TW and Canman CE: REV1 and polymerase ζ facilitate

homologous recombination repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:682–691.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Baranovskiy AG, Lada AG, Siebler HM, Zhang

Y, Pavlov YI and Tahirov TH: DNA polymerase delta and zeta switch

by sharing accessory subunits of DNA polymerase delta. J Biol Chem.

287:17281–17287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mellor C, Nassar J, Šviković S and Sale

JE: PRIMPOL ensures robust handoff between on-the-fly and

post-replicative DNA lesion bypass. Nucleic Acids Res. 52:243–258.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Taglialatela A, Leuzzi G, Sannino V,

Cuella-Martin R, Huang JW, Wu-Baer F, Baer R, Costanzo V and Ciccia

A: REV1-Polzeta maintains the viability of homologous

recombination-deficient cancer cells through mutagenic repair of

PRIMPOL-dependent ssDNA gaps. Mol Cell. 81:4008–4025. e72021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Nayak S, Calvo JA, Cong K, Peng M,

Berthiaume E, Jackson J, Zaino AM, Vindigni A, Hadden MK and Cantor

SB: Inhibition of the translesion synthesis polymerase REV1

exploits replication gaps as a cancer vulnerability. Sci Adv.

6:eaaz78082020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nayak S, Calvo JA and Cantor SB: Targeting

translesion synthesis (TLS) to expose replication gaps, a unique

cancer vulnerability. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 25:27–36. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lin X and Howell SB: DNA mismatch repair

and p53 function are major determinants of the rate of development

of cisplatin resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 5:1239–1247. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sasatani M, Xi Y, Kajimura J, Kawamura T,

Piao J, Masuda Y, Honda H, Kubo K, Mikamoto T, Watanabe H, et al:

Overexpression of Rev1 promotes the development of

carcinogen-induced intestinal adenomas via accumulation of point

mutation and suppression of apoptosis proportionally to the Rev1

expression level. Carcinogenesis. 38:570–578. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhu N, Zhao Y, Mi M, Lu Y, Tan Y, Fang X,

Weng S and Yuan Y: REV1: A novel biomarker and potential

therapeutic target for various cancers. Front Genet. 13:9979702022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wojtaszek JL, Chatterjee N, Najeeb J,

Ramos A, Lee M, Bian K, Xue JY, Fenton BA, Park H, Li D, et al: A

small molecule targeting mutagenic translesion synthesis improves

chemotherapy. Cell. 178:152–159.e11. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chatterjee N, Whitman MA, Harris CA, Min

SM, Jonas O, Lien EC, Luengo A, Vander Heiden MG, Hong J, Zhou P,

et al: REV1 inhibitor JH-RE-06 enhances tumor cell response to

chemotherapy by triggering senescence hallmarks. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 117:28918–28921. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chen Y, Jie X, Xing B, Wu Z, Yang X, Rao

X, Xu Y, Zhou D, Dong X, Zhang T, et al: REV1 promotes lung

tumorigenesis by activating the Rad18/SERTAD2 axis. Cell Death Dis.

13:1102022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow

J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M and Gingeras TR: STAR:

Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 29:15–21.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mizuno H, Kitada K, Nakai K and Sarai A:

PrognoScan: A new database for meta-analysis of the prognostic

value of genes. BMC Med Genomics. 2:182009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sharma S, Shah NA, Joiner AM, Roberts KH

and Canman CE: DNA polymerase ζ is a major determinant of

resistance to platinum-based chemotherapeutic agents. Mol

Pharmacol. 81:778–787. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J

and Jiang X: Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell

Res. 26:1021–1032. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh

HJ III, Kang R and Tang D: Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by

degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 12:1425–1428. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Radulescu S, Brookes MJ, Salgueiro P,

Ridgway RA, McGhee E, Anderson K, Ford SJ, Stones DH, Iqbal TH,

Tselepis C and Sansom OJ: Luminal iron levels govern intestinal

tumorigenesis after Apc loss in vivo. Cell Rep. 2:270–282. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hu Q, Wei W, Wu D, Huang F, Li M, Li W,

Yin J, Peng Y, Lu Y, Zhao Q and Liu L: Blockade of GCH1/BH4 axis

activates ferritinophagy to mitigate the resistance of colorectal

cancer to erastin-induced ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol.

10:8103272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM

and Wallace MB: Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 394:1467–1480. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xie K, Doles J, Hemann MT and Walker GC:

Error-prone translesion synthesis mediates acquired

chemoresistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:20792–20797. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bruno PM, Liu Y, Park GY, Murai J, Koch

CE, Eisen TJ, Pritchard JR, Pommier Y, Lippard SJ and Hemann MT: A

subset of platinum-containing chemotherapeutic agents kills cells

by inducing ribosome biogenesis stress. Nat Med. 23:461–471. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sekimoto T, Oda T, Kurashima K, Hanaoka F

and Yamashita T: Both high-fidelity replicative and low-fidelity

Y-family polymerases are involved in DNA rereplication. Mol Cell

Biol. 35:699–715. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang G, Wang JJ, Zhi-Min Z, Xu XN, Shi F

and Fu XL: Targeting critical pathways in ferroptosis and enhancing

antitumor therapy of Platinum drugs for colorectal cancer. Sci

Prog. 106:3685042211471732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fakouri NB, Durhuus JA, Regnell CE,

Angleys M, Desler C, Hasan-Olive MM, Martín-Pardillos A,

Tsaalbi-Shtylik A, Thomsen K, Lauritzen M, et al: Rev1 contributes

to proper mitochondrial function via the PARP-NAD+-SIRT1-PGC1alpha

axis. Sci Rep. 7:124802017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Anugula S, Li Z, Li Y, Hendriksen A,

Christensen PB, Wang L, Monk JM, de Wind N, Bohr VA, Desler C, et

al: Rev1 deficiency induces a metabolic shift in MEFs that can be

manipulated by the NAD(+) precursor nicotinamide riboside. Heliyon.

9:e173922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Federico G, Carrillo F, Dapporto F,

Chiariello M, Santoro M, Bellelli R and Carlomagno F: NCOA4 links

iron bioavailability to DNA metabolism. Cell Rep. 40:1112072022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wu H, Liu Q, Shan X, Gao W and Chen Q: ATM

orchestrates ferritinophagy and ferroptosis by phosphorylating

NCOA4. Autophagy. 19:2062–2077. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang MJ, Song ML, Zhang Y, Yang XM, Lin

HS, Chen WC, Zhong XD, He CY, Li T, Liu Y, et al: SNS alleviates

depression-like behaviors in CUMS mice by regluating dendritic

spines via NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy. J Ethnopharmacol.

312:1163602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kuno S and Iwai K: Oxygen modulates iron

homeostasis by switching iron sensing of NCOA4. J Biol Chem.

299:1047012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bellelli R, Castellone MD, Guida T,

Limongello R, Dathan NA, Merolla F, Cirafici AM, Affuso A, Masai H,

Costanzo V, et al: NCOA4 transcriptional coactivator inhibits

activation of DNA replication origins. Mol Cell. 55:123–137. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li J, Zheng C, Mai Q, Huang X, Pan W, Lu

J, Chen Z, Zhang S, Zhang C, Huang H, et al: Tyrosine catabolism

enhances genotoxic chemotherapy by suppressing translesion DNA

synthesis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cell Metab.

35:2044–2059.e8. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen Y, Feng X, Wu Z, Yang Y, Rao X, Meng

R, Zhang S, Dong X, Xu S, Wu G and Jie X: USP9X-mediated REV1

deubiquitination promotes lung cancer radioresistance via the

action of REV1 as a Rad18 molecular scaffold for cystathionine

γ-lyase. J Biomed Sci. 31:552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|