Introduction

Thyroid cancer is the most common malignant

endocrine tumor, with an increasing incidence, especially among

women (1). Differentiated thyroid

cancer (DTC), which includes papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and

follicular subtypes, accounts for 95% of all cases (2). The standard treatment for

intermediate- and high-risk DTC is total thyroidectomy, followed by

postoperative monitoring of serum thyroglobulin (Tg) and Tg

antibody (Tg/Ab) levels to detect residual or recurrent disease

(3,4). Oral administration of radioactive

iodine (131I) is used when the Tg and Tg/Ab levels

exceed standard levels. Conventional radioisotope therapy using

131I increases serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

levels by thyroid hormone withdrawal (THW), promoting

131I accumulation in the remaining DTC tissues (5). However, because THW-induced

hypothyroidism increases the risk of complications, and the number

of patients waiting for treatment is increasing, recombinant human

TSH (rhTSH), which does not require THW treatment and

hospitalization, is recommended (3). However, serum Tg levels are often

disturbed by Tg/Ab interference, and this is observed in

one-quarter of all patients with DTC (6–8).

Therefore, researchers are exploring metabolic and genetic

alterations as complementary biomarkers to Tg to improve the

assessment of disease status. However, no reliable standard test

has been developed (8–10). Additionally, morphology and

functionality can be observed using radiological imaging

techniques, such as positron emission tomography/computed

tomography. However, the levels or presence of Tg and Tg/Ab cannot

be visualized using imaging modalities (11). The lack of association between serum

Tg levels and antitumor efficacy in Tg/Ab-positive patients makes

it difficult to continue 131I therapy (12) and novel therapeutic biomarkers are

needed to address this challenge. Mass spectrometry has been used

to explore the possibility of using serum metabolomic analysis to

quantify metabolites in biological samples (13). Blood metabolites in patients with

DTC are likely to include various diagnostic biomarkers, such as

altered levels of amino acids (leucine, valine, lysine and

tyrosine), lactate, citrate and lipids, including

lysophosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelins, according to previous

metabolomic studies (14–17). If Tg/Ab is detected as positive

during 131I therapy in combination with rhTSH, the

identification of a novel metabolite that can complement Tg will

allow treatment optimization. Therefore, the present study aimed to

elucidate the molecular mechanisms of metabolomic alterations in

patients with DTC treated with 131I and to identify

Tg/Ab-independent biomarker candidates using a TPC-1 thyroid cancer

cell model. Although the clinical sample size was limited, the

present study was designed as a proof-of-concept to provide

preliminary evidence supported by experimental validation.

Materials and methods

Analysis of patients with thyroid

cancer

The present study was approved by the Committee of

Medical Ethics of the Hirosaki University Graduate School of Health

Sciences (approval no. 2021–050; Hirosaki, Japan). To protect the

rights and privacy of the participants, written informed consent

was obtained after providing a detailed verbal explanation, and all

collected data were anonymized and handled in accordance with

ethical guidelines. The present study included 3 patients (2 female

patients and 1 male patient; median age, 58 years; age range, 45–81

years) with DTC who received 131I internal therapy with

rhTSH (Thyrogen®; Sanofi S.A.) between April 2022 and

December 2024 at Aomori Rosai Hospital (Hachinohe, Japan) (Table I). The inclusion criteria were as

follows: Age ≥18 years; histologically confirmed differentiated

thyroid carcinoma; completion of total thyroidectomy; planned

adjuvant 131I therapy with rhTSH stimulation; and

provision of informed consent. The exclusion criteria were:

Presence of medullary or anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; uncontrolled

severe comorbidities (such as renal failure or severe cardiac

disease); prior radioiodine therapy within 12 months; and inability

to comply with the study procedures. During treatment, clinical

information and blood samples were collected. Routine blood tests,

including complete blood counts (red blood cells, white blood cells

and platelets) and thyroid-related parameters [TSH, free

triiodothyronine (FT3), free thyroxine (FT4), Tg and Tg/Ab], were

performed at the clinical laboratory of Aomori Rosai Hospital at

three timepoints: Before 131I administration (baseline),

on the day of 131I administration (day 0) and 30 days

after treatment (day 30), consistent with the measurements shown in

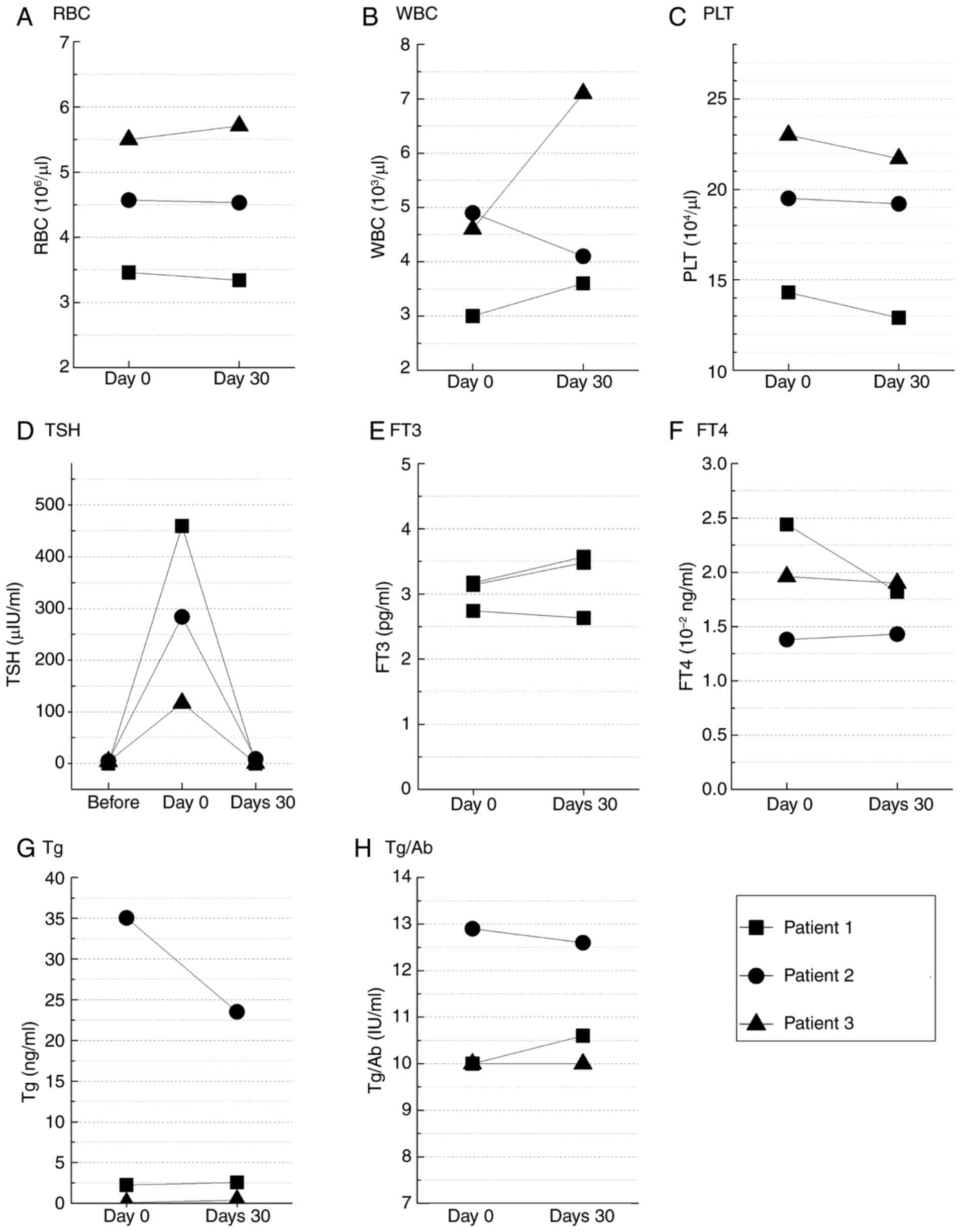

Fig. 1.

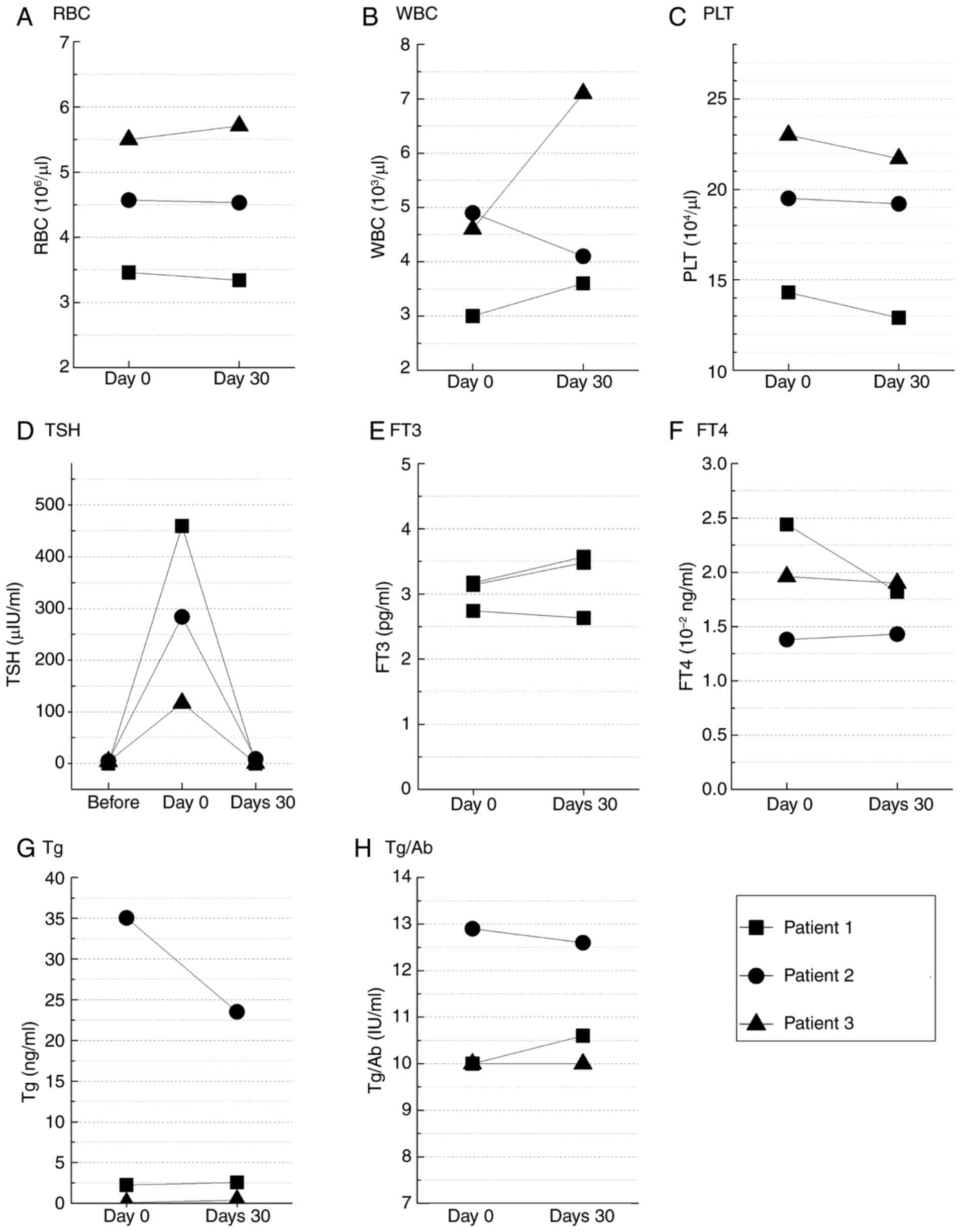

| Figure 1.Blood biomarkers measured before

131I administration (baseline), on the day of

131I administration (day 0) and 30 days after treatment

(day 30) in 3 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer after

thyroidectomy. (A) RBC, (B) WBC, (C) PLT, (D) TSH, (E) FT3, (F)

FT4, (G) Tg and (H) Tg/Ab. Statistical analysis was performed using

the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired comparisons involving two

timepoints. For TSH, comparisons across three timepoints were

performed using the Friedman test. No significant differences were

observed in any of the biomarkers. Normal reference ranges: RBC,

4.0–5.5×106/µl; WBC, 4.0–9.0×103/µl; PLT,

15–35×104/µl; TSH, 0.4–4.0 µIU/ml; FT3, 2.3–4.1 pg/ml;

FT4, 0.9–1.7×10−2 ng/ml; Tg, <30 ng/ml; Tg/Ab, <40

IU/ml. FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; PLT,

platelets; RBC, red blood cells; Tg, thyroglobulin; Tg/Ab,

thyroglobulin antibody; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; WBC,

white blood cells. |

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of the study

population. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of the study

population.

| Patient no. | Sex | Age, years | TNM

classification | Thyroid hormone

replacement after thyroidectomy | External

radiotherapy | 131I

administration |

|---|

| 1 | F | 81 |

T4aN0M0 | Liothyronine | 50 Gy/25 fr | 1.11 GBq |

| 2 | F | 58 |

rT0N0Mx |

| 40 Gy/20 fr + |

|

| 3 | M | 45 |

pT1aN1aM0 |

| 20 Gy/10 fr |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (boost) |

|

Serum metabolomic analysis

Peripheral blood was collected from patients with

DTC using serum separation tubes (BD Biosciences) at two time

points: Before the administration of 131I (day 0) and 30

days after administration (day 30), both under Thyrogen

stimulation. To minimize the influence of recent dietary intake,

patients were instructed to fast for ≥6 h prior to blood

collection. The collected sample tubes were stored in a deep

freezer (−80°C) until analysis. Serum metabolomic analysis was

performed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and

flow injection analysis-mass spectrometry (FIA-MS), and the

AbsoluteIDQ P180 kit (Biocrates, Inc.) was used to quantify

metabolites. The analysis was performed using the method described

in our previous study (18). The

target metabolites were phenyl isothiocyanate-derivatized and

analyzed based on internal standards for quantitation. LC-MS and

FIA-MS were performed in positive ion mode using electrospray

ionization using a high-performance liquid chromatography system

(ExionLC™ AD; SCIEX) combined with a QTRAP 6500+ triple

quadruple ion trap hybrid mass spectrometer system (SCIEX) operated

with Analyst® 1.6.3 software (SCIEX). LC-MS was used to

measure amino acids and biogenic amines, and the multiple reaction

monitoring (MRM) conditions are shown in Table SI. The MS measurement conditions

were as follows: Curtain gas, 45 psi; collision gas, 6 psi; ion

spray voltage, 5,500 V; temperature, 500°C; ion source gas 1, 40

psi; and ion source gas 2, 50 psi. LC separation was performed on a

Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (3×100 mm; 3.5 µm; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) at 40°C. The mobile phases consisted of solvent

A (water with 0.2% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with

0.2% formic acid). The flow rate was set at 0.5 ml/min. The

gradient program was as follows: 0–0.5 min, 0% B; 0.5–5.5 min,

linear increase to 95% B; 5.5–6.5 min, held at 95% B; 6.5–7 min,

returned to 0% B and equilibrated for the next injection for 1.5

min. FIA-MS measurements included carnitines and acylcarnitines,

hydroxy- and dicarboxyacylcarnitines, sphingomyelins and

hydroxysphingomyelins, diacyl phosphatidylcholine, acyl-alkyl

phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholine, and sugar as targets.

The MRM conditions for measuring these metabolites are shown in

Table SII. The MS settings were

the same as those for LC-MS, except that the temperature was 175°C.

The FIA-MS flow program was as follows: 0–1.6 min, 0.03 ml/min;

1.6–2.4 min, linear increase to 0.2 ml/min; 2.4–2.8 min, held at

0.2 ml/min; and 2.8–3.0 min, returned to 0.03 ml/min. The injection

volume was 20 µl. As with LC-MS, FIA-MS quantification was

performed using isotopically labeled internal standards provided in

the AbsoluteIDQ P180 kit to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

All metabolites were identified and quantified using isotopically

labeled internal standards and multiple reaction monitoring as

optimized and provided by Biocrates, Inc. Table II shows the measurable metabolites

and their abbreviations. Amino acids and biogenic amines were

quantified using LC-MS, whereas acylcarnitines,

phosphatidylcholines, lysophosphatidylcholines, sphingomyelins and

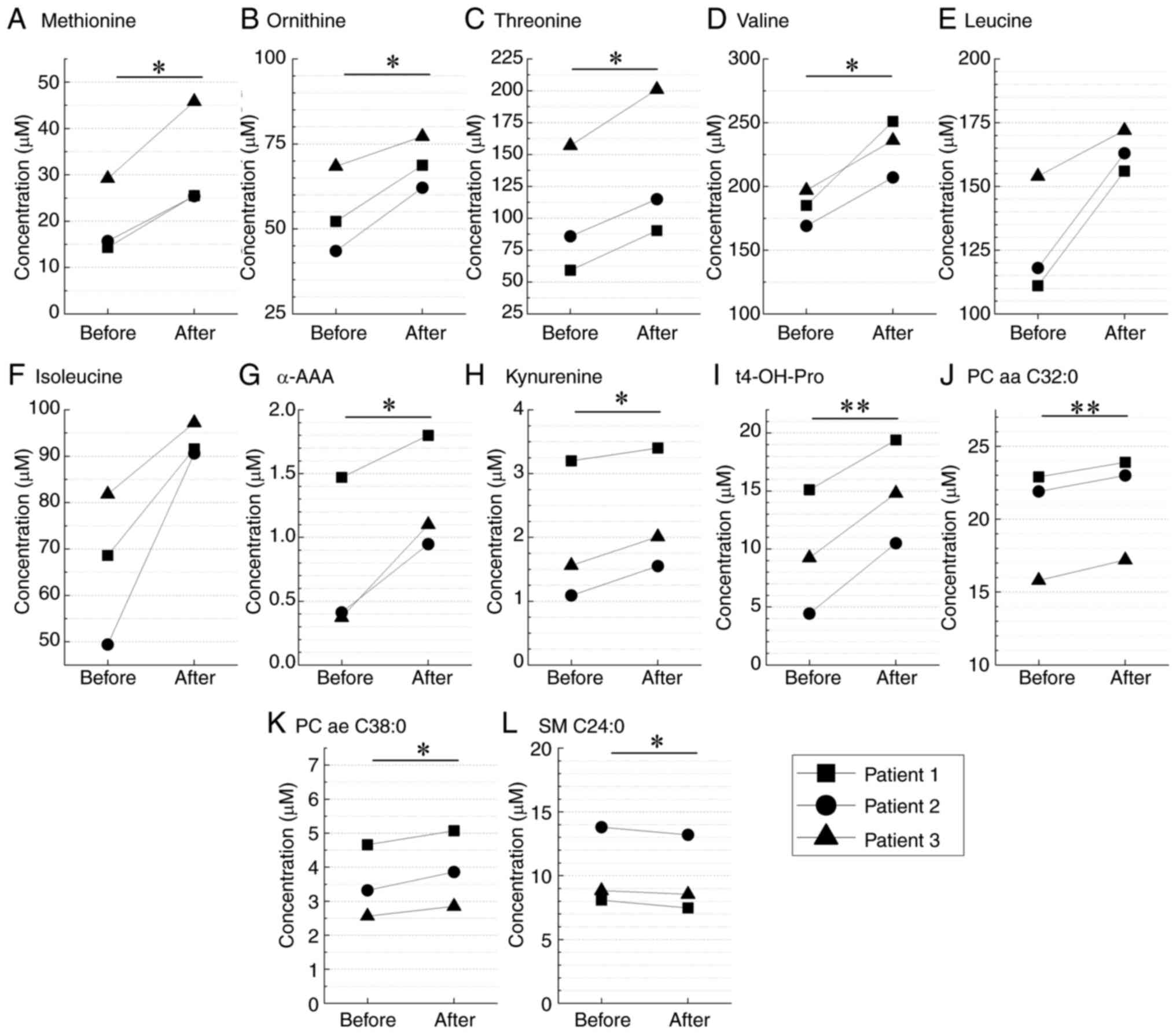

hexose were analyzed by FIA-MS. Among these, Fig. 2 highlights representative

metabolites from each category that showed statistically

significant or consistent changes before and after 131I

administration. The metabolomics datasets of LC-MS and FIA-MS

generated in the present study have been deposited in MetaboBank

(https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/metabobank/index-e.html)

under the accession numbers MTBKS257 and MTBKS258, respectively.

For pathway enrichment analysis, metabolites that showed

significant changes before and after 131I administration

were analyzed using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/) with pathway annotation

based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/).

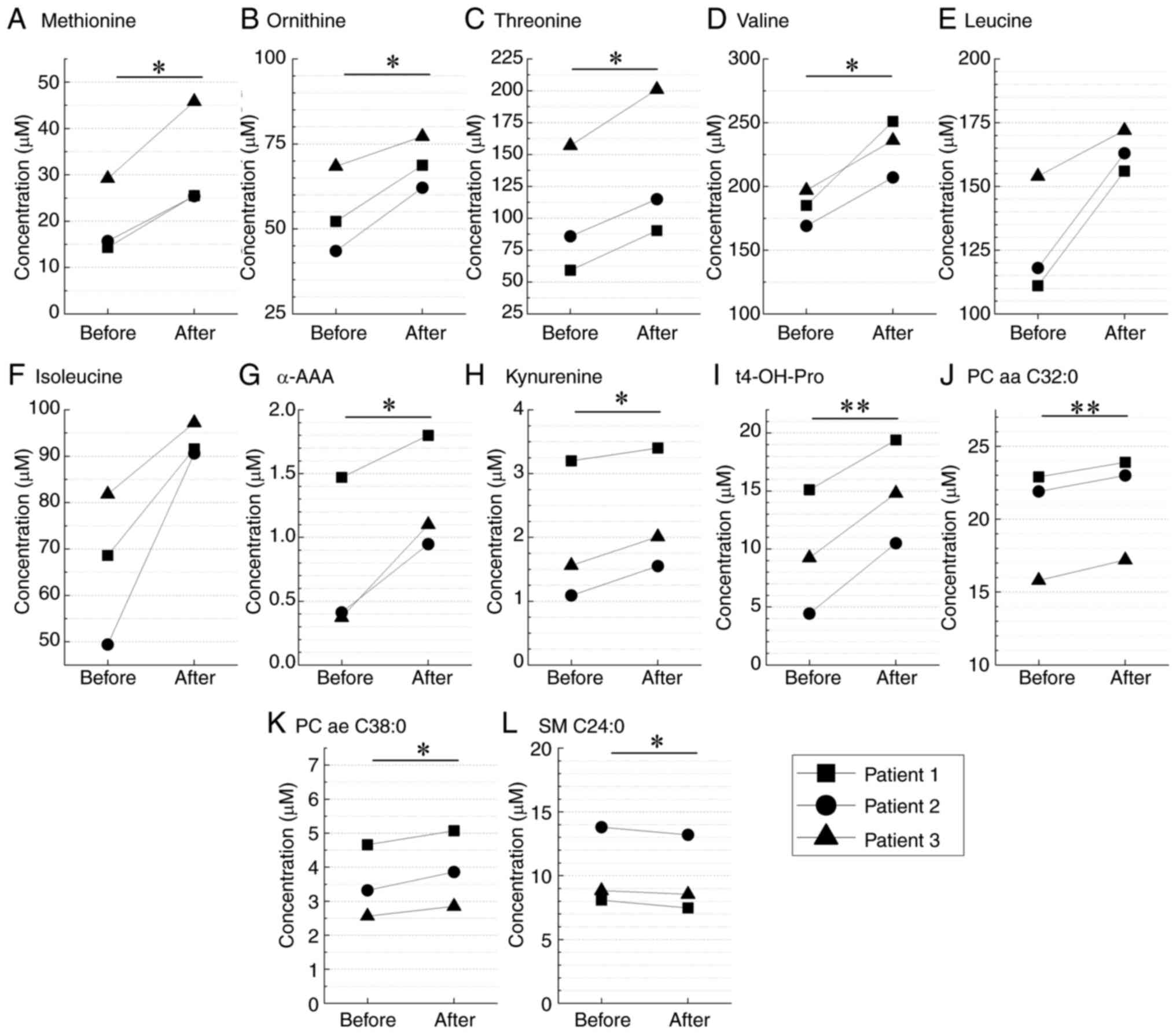

| Figure 2.Quantification of serum metabolites

using mass spectrometry. Analysis of the serum samples collected

from patients with differentiated thyroid cancer before (day 0) and

after 131I administration (day 30). The levels of 12

metabolites, namely (A) methionine, (B) ornitine, (C) threonine,

(D) valine, (E) leucine, (F) isoleucine, (G) α-AAA, (H) kynurenine,

(I) t4-OH-Pro, (J) PC aa C32:0, (K) PC ae C38:0 and (L) SM C24:0,

are shown. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

α-AAA, α-aminoadipic acid; PC aa C32:0, phosphatidylcholine type aa

C32:0; PC ae C38:0, phosphatidylcholine type ae C38:0; SM C24:0,

sphingomyelin type C24:0; t4-OH-Pro, trans-4-hydroxyprolin. |

| Table II.List of target metabolites measured

with the AbsoluteIDQ P180 kit. |

Table II.

List of target metabolites measured

with the AbsoluteIDQ P180 kit.

| Metabolite

class | Number of analysis

targets | Abbreviations of

analysis objects |

|---|

| Amino acids and

biogenic amines | 42 | Ala, Arg, Asn, Asp,

Cit, Gln, Glu, Gly, His, Ile, Leu, Lys, Met, Orn, Phe, Pro, Ser,

Thr, Trp, Tyr, Val, Ac-Orn, ADMA, α-AAA, c4-OH-Pro, carnosine,

creatinine, DOPA, dopamine, histamine, kynurenine, Met-SO,

nitro-Tyr, PEA, putrescine, SDMA, serotonin, spermidine, spermine,

t4-OH-Pro, taurine, total DMA |

| Carnitines and

acylcarnitines | 26 | C0, C2, C3, C3:1,

C4, C4:1, C5, C5:1, C6 (C4:1-DC), C6:1, C8, C9, C10, C10:1, C10:2,

C12, C12:1, C14, C14:1, C14:2, C16, C16:1, C16:2, C18, C18:1,

C18:2 |

| Hydroxy- and

dicarboxyacylcarnitines | 14 | C3-DC (C4-OH),

C3-OH, C5-DC (C6-OH), C5-M-DC, C5-OH (C3-DC-M), C5:1-DC, C7-DC,

C12-DC, C14:1-OH, C14:2-OH, C16-OH, C16:1-OH, C16:2-OH,

C18:1-OH |

| Sphingomyeline and

hydroxysphingomyelins | 15 | SM (OH) C14:1, SM

(OH) C16:1, SM (OH) C22:1, SM (OH) C22:2, SM (OH) C24:1, SM C16:0,

SM C16:1, SM C18:0, SM C18:1, SM C20:2, SM C22:3, SM C24:0, SM

C24:1, SM C26:0, SM C26:1 |

| Diacyl

phosphatidylcholine | 38 | PC aa C24:0, PC aa

C26:0, PC aa C28:1, PC aa C30:0, PC aa C30:2, PC aa C32:0, PC aa

C32:1, PC aa C32:2, PC aa C32:3, PC aa C34:1, PC aa C34:2, PC aa

C34:3, PC aa C34:4, PC aa C36:0, PC aa C36:1, PC aa C36:2, PC aa

C36:3, PC aa C36:4, PC aa C36:5, PC aa C36:6, PC aa C38:0, PC aa

C38:1, PC aa C38:3, PC aa C38:4, PC aa C38:5, PC aa C38:6, PC aa

C40:1, PC aa C40:2, PC aa C40:3, PC aa C40:4, PC aa C40:5, PC aa

C40:6, PC aa C42:0, PC aa C42:1, PC aa C42:2, PC aa C42:4, PC aa

C42:5, PC aa C42:6 |

| Acyl-alkyl

phosphatidylcholine | 38 | PC ae C30:0, PC ae

C30:1, PC ae C30:2, PC ae C32:1, PC ae C32:2, PC ae C34:0, PC ae

C34:1, PC ae C34:2, PC ae C34:3, PC ae C36:0, PC ae C36:1, PC ae

C36:2, PC ae C36:3, PC ae C36:4, PC ae C36:5, PC ae C38:0, PC ae

C38:1, PC ae C38:2, PC ae C38:3, PC ae C38:4, PC ae C38:5, PC ae

C38:6, PC ae C40:1, PC ae C40:2, PC ae C40:3, PC ae C40:4, PC ae

C40:5, PC ae C40:6, PC ae C42:0, PC ae C42:1, PC ae C42:2, PC ae

C42:3, PC ae C42:4, PC ae C42:5, PC ae C44:3, PC ae C44:4, PC ae

C44:5, PC ae C44:6 |

|

Lysophosphatidylcholine | 14 | lysoPC a C14:0,

lysoPC a C16:0, lysoPC a C16:1, lysoPC a C17:0, lysoPC a C18:0,

lysoPC a C18:1, lysoPC a C18:2, lysoPC a C20:3, lysoPC a C20:4,

lysoPC a C24:0, lysoPC a C26:0, lysoPC a C26:1, lysoPC a C28:0,

lysoPC a C28:1 |

| Sugar | 1 | H1 |

| Total | 188 | - |

Cell culture for thyroid cancer cell

model

The TPC-1 human thyroid papillary carcinoma cell

line was obtained from Merck KGaA. The cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) containing 10% heat-inactivated

fetal bovine serum (Biowest), 2 mM L-glutamine (MilliporeSigma) and

1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C with

5% CO2.

Exposure to ionizing radiation (IR)

for the basic experiment

TPC-1 cells were irradiated using an X-ray generator

(MBR-1520R-3; Hitachi Power Solutions Co., Ltd.) at 1 Gy/min (150

kVp; 20 mA) with 0.5-mm aluminum and 0.3-mm copper filters. The

radiation dose was monitored using a thimble ionization chamber.

Handling of ¹3¹I in vitro requires specialized

radiation safety measures and licensing, which can impede

exploratory studies. Therefore, X-rays were chosen as a practical

and controllable radiation source to model general cellular

responses to IR independently of sodium/iodide symporter

(NIS)-mediated uptake. Based on clonogenic survival assays, an 8 Gy

dose was selected for irradiation to ensure ~1% survival of TPC-1

cells. This dose was chosen to induce measurable biological effects

relevant to therapeutic radiation exposure while maintaining

sufficient cell viability for downstream analyses. Although

clinical radioiodine therapy doses vary depending on remnant size

and uptake, the 8 Gy dose provides a reproducible and biologically

meaningful model to study cellular radiation responses. Clinical

absorbed doses to thyroid remnants and metastases are typically

much higher (commonly cited targets, ~300 Gy for remnants and ~80

Gy for metastases) (19,20). Cell viability was assessed using a

trypan blue exclusion assay. Briefly, 20 µl cell suspension was

mixed with 20 µl trypan blue solution (0.4%; 2-fold dilution;

Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) at room temperature. The cells were gently

mixed and incubated for <3 min to allow dye penetration into

nonviable cells. The viable (unstained) and nonviable

(blue-stained) cells were then counted using a Bürker-Türk

hemocytometer (Erma, Inc.) under a light microscope (IX71; Olympus

Corporation) without fixation.

Clonogenic potency assay for TPC-1

cells

Colony-forming cells were counted using a clonogenic

potency assay. The cells were plated at a density of 500–8,000

cells/dish in a 35-mm diameter culture dish, irradiated with 0 to 8

Gy of IR and incubated for 6–9 days in a humidified atmosphere at

37°C with 5% CO2. The irradiation was delivered at a

dose rate of 1 Gy/min, and the exposure time was adjusted according

to the prescribed dose. Subsequently, the dishes were fixed with

−20°C cold methanol for 15 min and stained with Giemsa solution

(Muto Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 30 min.

Colonies containing >50 cells were manually counted under an

inverted microscope (IX71; Olympus Corporation). The cell survival

rate was calculated relative to the nonirradiated controls and

plating efficiency, as described previously (21).

Cell cycle distribution analysis

The cell cycle distribution was analyzed using flow

cytometry. The harvested cells were treated with precooled (−20°C)

70% ethanol for 10 min on ice and stored at −20°C until measured.

RNase I was added to the sample tube at 37°C for 20 min (5 µg/ml;

Merck KGaA) to remove internal RNAs. The cells were then stained

with PI (40 µg/ml; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) in the

dark at room temperature for 2 min. Cell cycle distribution

analysis was performed using Cell Lab Quanta™ Sc MPL

(Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and analyzed with Kaluza software (version

2.1; Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Amino acid uptake assay

Amino acid uptake into cells was analyzed using a

boronophenylalanine (BPA) uptake assay kit (cat. no. 342-09893;

Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.). BPA is an amino acid analog. The cells

exposed to IR were plated in a 96-well microplate and incubated for

12 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Reagents were added

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The fluorescence of

the samples (Ex350/Em455) was first measured

using a microplate reader (TriStar LB 941; Berthold Technologies

GmbH & Co. KG). After this, the incubated cells were harvested

and analyzed by flow cytometry (Aria SORP; BD Biosciences) using

FACS Diva™ software (ver.6.0; BD Biosciences) to assess

BPA uptake at the single-cell level. This assay utilizes a

cell-permeable fluorescent probe that binds to intracellular amino

acid analogs. Upon uptake of BPA via amino acid transporters such

as solute carrier family 7 member 5 [L-type amino acid transporter

type 1 (LAT1)], the probe emits fluorescence (λex, 360

nm; λem, 460 nm), allowing quantification of transporter

activity in viable individual cells.

CD98 cell surface antigen

expression

The expression levels of the CD98 cell surface

antigen were analyzed using double staining with PI and CD98-FITC.

The harvested cells were suspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution

at 4°C. CD98-FITC (5 µl per 1×106 cells in 100 µl

staining volume; cat. no. 315603; BioLegend, Inc.) was added to the

sample tubes and these were incubated for 20 min on ice (~0°C) in

the dark. After washing with Hanks' balanced salt solution, the

samples were stained with PI (40 µg/ml; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical

Corporation) for 3 min at room temperature. Cellular fluorescence

was measured using Cell Lab Quanta™ Sc MPL (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.) and analyzed with Kaluza software (version 2.1;

Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Total RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the

RNeasy® Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc.). The concentration

and quality were confirmed using the NanoDrop system (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). cDNAs were synthesized to analyze mRNA

expression using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primer sequences

for LAT1, solute carrier family 7 member 8 [L-type amino

acid transporter type 2 (LAT2)] and solute carrier family 3

member 2 (CD98hc) were designed based on the gene sequences

obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information

database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/). The mRNA

expression levels were evaluated using RT-qPCR with the Power

SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and SmartCycler® II (Takara Bio, Inc.). The

thermocycling conditions were: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The relative

expression of each target mRNA was determined using the

2−ΔΔCq method (22). The

accession numbers were as follows: LAT1, NM_003486.7;

LAT2, NM_001267036.1; CD98hc, NM_001012662.3; and

β-2-microglobulin (B2M), NM_004048.4. The oligonucleotide

primer sets used for RT-qPCR were designed using Primer3 software

(version 4.1.0) (23) and supplied

by Eurofins Genomics (Table III).

B2M was selected as the housekeeping gene for normalization

based on the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative

Real-Time PCR Experiments guidelines (24).

| Table III.Sequences of human LAT1, LAT2,

CD98hc and B2M primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table III.

Sequences of human LAT1, LAT2,

CD98hc and B2M primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Name | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

|

LAT1-Forward |

TACTTCACCACCCTGTCCAC |

|

LAT1-Reverse |

TGGAGGATGTGAACAGGGAC |

|

LAT2-Forward |

ATTGAGCTGCTAACCCTGGT |

|

LAT2-Reverse |

AGGAGAGAGTAGCCAGGGAA |

|

CD98hc-Forward |

TCTTGATTGCGGGGACTAAC |

|

CD98hc-Reverse |

GCCTTGCCTGAGACAAACTC |

|

B2M-Forward |

TTTCATCCATCCGACATTGA |

|

B2M-Reverse |

CCTCCATGATGCTGCTTACA |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software

(version 4.4.0; http://www.r-project.org/). Cell cycle analysis was

conducted using Kaluza software (version 2.1; Beckman Coulter,

Inc.) to identify sub-G1, G0/G1, S

and G2/M phases. The clonogenic survival fraction (F)

was fitted to the equation F(D)=exp

(−αD-βD2), where D is the dose in Gy and α

and β are fitting coefficients, using the

Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. For small sample sizes (n=3), the

Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for paired comparisons involving

two timepoints (such as metabolomic data before vs. after

131I administration). For TSH levels measured at three

timepoints (before rhTSH, day 0 and day 30), the Friedman test was

applied to account for repeated measures across multiple

timepoints. This test was chosen as a non-parametric alternative to

repeated-measures ANOVA suitable for small sample sizes and

non-normal distributions. For comparisons between two independent

groups with normal distribution and equal variance, an unpaired

Student's t-test was used. For data with unequal variance, Welch's

t-test was applied. For comparisons among multiple groups with

normal distribution and equal variance, one-way ANOVA was used,

followed by the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test for pairwise

comparisons. For comparisons of mRNA expression levels among

multiple radiation dose groups, one-way ANOVA followed by the

Tukey-Kramer post hoc test was used. Data are presented as the mean

± SD. The number of independent experiments ranged between 3 to 10.

P<0.05 or false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics during

131I therapy

Of the 3 patients with DTC included in the present

study, 2 were female and 1 was male. The patients were diagnosed

with PTC (Table I). Additionally,

the patients had no previous medical history of other thyroid

diseases. Thyrogen was administered twice, 2 days and 1 day before

131I administration, and its accumulation in the

residual tumor was observed using scintillation scanning during

treatment. Antitumor effects were observed in all patients 6 months

after the initial prescription of Thyrogen, as evaluated based on

the medical records of the patients (data not shown). No

significant hemocytopenia was observed in terms of the numbers of

red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets within 30 days

after 131I therapy (Fig.

1A-C). Serum TSH levels increased in all patients, reaching a

maximum of 105–455 µIU/ml, from before Thyrogen administration to

just prior to 131I administration. By day 30 after

administration, TSH levels had returned to the same range as before

131I administration (Fig.

1D). FT3 and FT4 before and after treatment remained at 2.6–3.6

pg/ml and 1.4–2.4×10−2 ng/ml, respectively, which were

confirmed to be normal values (Fig. 1E

and F). Conversely, the levels of Tg/Ab and Tg in the serum

showed individual variations between patients (patient 1: Tg/Ab,

10–10.6 IU/ml; Tg, 2.24 ng/ml; patient 2: Tg/Ab, 12.6–12.9 IU/ml;

Tg, 23.5–35.1 ng/ml; patient 3: Tg/Ab, 10 IU/ml; Tg, 0.07–0.39

ng/ml; Fig. 1G and H).

Patient metabolomic analysis

Metabolomic analysis was performed using patient

serum to explore serum metabolites specifically altered by

131I radiotherapy following Thyrogen stimulation for

DTC. Of the 188 types of target metabolomic analysis data obtained

from mass spectrometry, 168 were highly reliable. Among them, the

levels of nine metabolites that changed before and after

131I administration were increased, and the levels of

one metabolite were decreased (Fig.

2). Furthermore, enrichment analysis based on the KEGG database

using MeatboAnalyst6.0 identified valine, leucine and isoleucine

biosynthesis as a significant metabolic pathway (FDR, 0.0392; data

not shown). Valine, leucine and isoleucine are essential amino

acids referred to as branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and are

involved in the nitrogen supply to cancer (25). In all cases, BCAA levels tended to

increase after 131I administration compared with before

administration (Fig. 2). However,

statistical significance was observed only for valine, whereas the

increases in leucine and isoleucine were not significant. Given the

small sample size (n=3), statistical comparisons were performed

using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The consistent upward trend

across patients supports the robustness of this exploratory

observation.

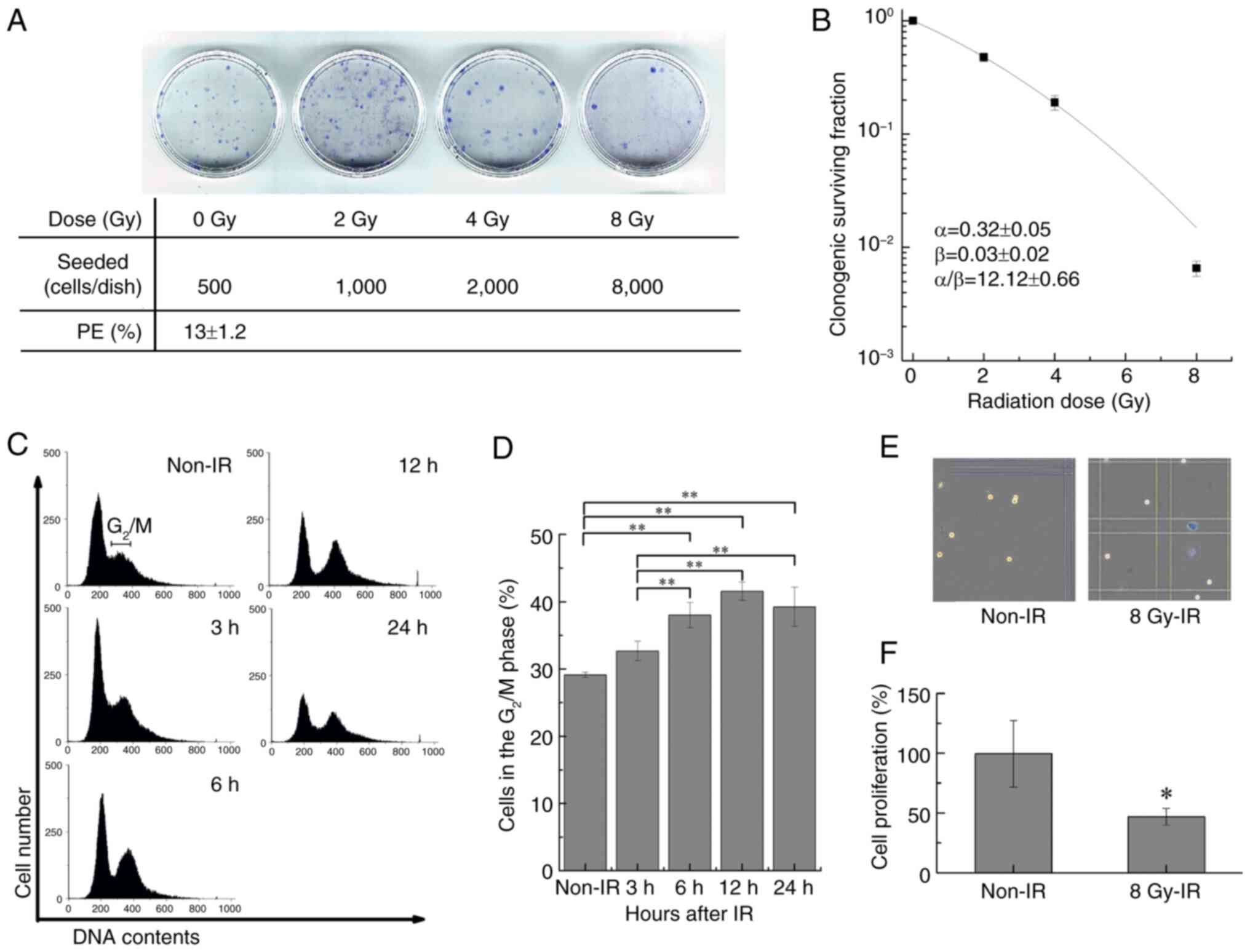

Radiosensitivity of TPC-1 cells

The TPC-1 cell line was used to examine whether the

serum metabolic changes observed in patients with DTC could be

recapitulated at the cellular level. Clonogenic potency and the

cell cycle were analyzed to confirm the radiosensitivity of TPC-1

cells. The plating efficiency for TPC-1 cell colony formation was

13±1.2% (Fig. 3A), the parameters

in the linear-quadratic model were α=0.32±0.05 Gy−1,

β=0.03±0.02 Gy−2 and α/β=12.12±0.66, and the survival

rate was <1% at 8 Gy (Fig. 3B).

The cell cycle phase distribution analysis of cells exposed to 8 Gy

IR showed a time-dependent increase in cells in the G2/M

phase for 12 h. A significant increase was observed at 6–24 h

compared with the non-irradiated control (Fig. 3C and D). The number of viable cells

after 12 h of exposure decreased to ~50% compared with that of the

non-irradiated group (Fig. 3E).

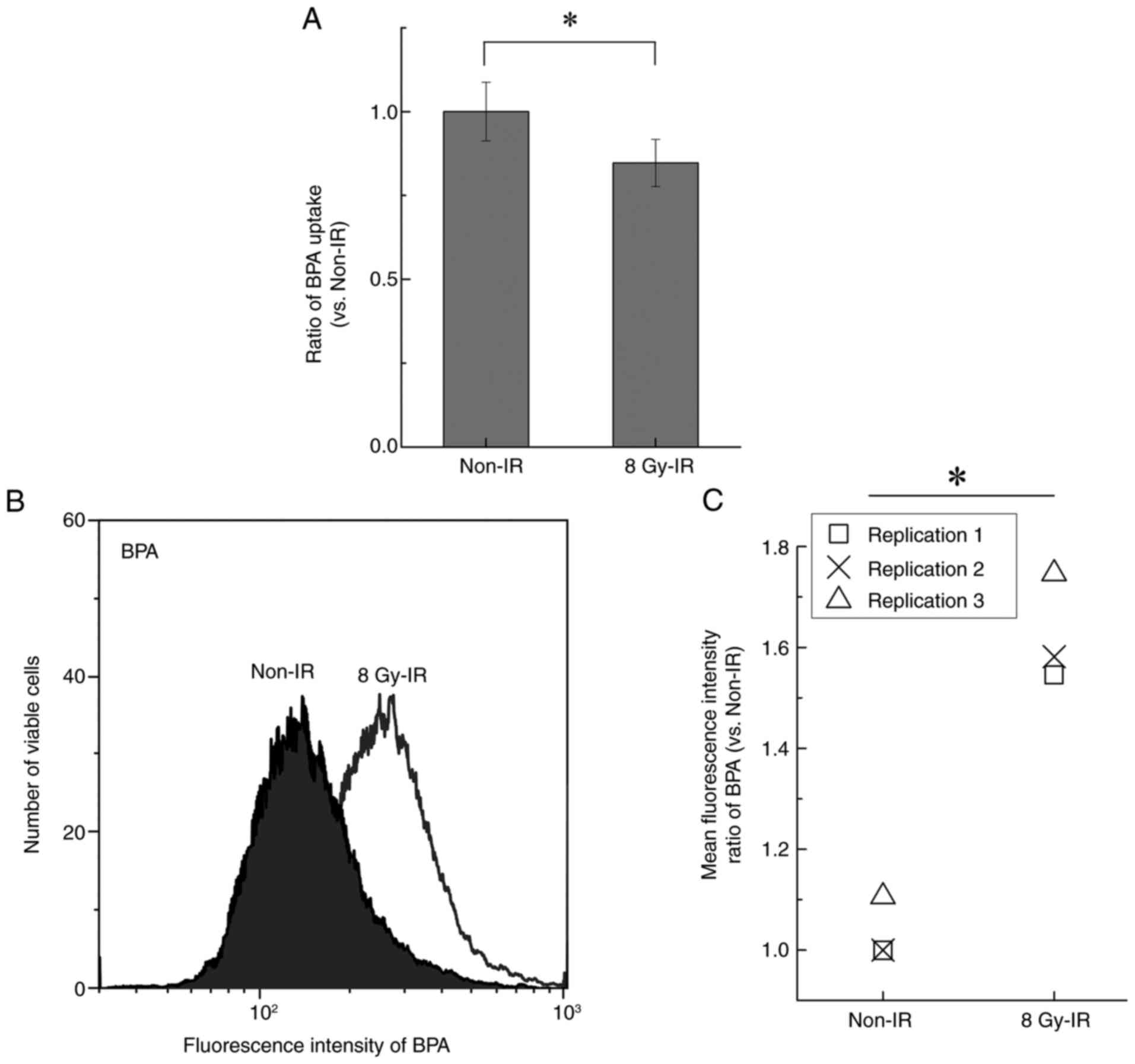

Quantitation of BCAA uptake under IR

exposure

Similar to BCAAs, BPA is taken up by cells via LAT1

(26,27). Changes in BPA uptake were evaluated

to determine the BCAA uptake ability of irradiated TPC-1 cells.

After 12 h of exposure to 8 Gy IR, intracellular BPA levels

significantly decreased to ~80% of those in the non-irradiated

control group, corresponding to an ~20% reduction (Fig. 4A). Conversely, single-cell analysis

by flow cytometry revealed that the levels of intracellular BPA

following exposure to IR were significantly upregulated ~1.58 times

compared with the non-irradiated control (Fig. 4B and C).

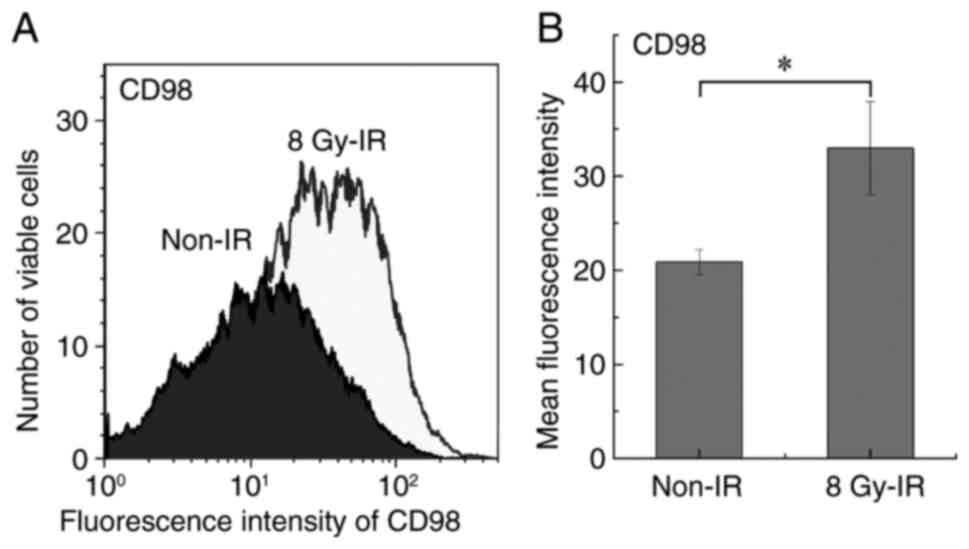

CD98 expression

LAT1 forms a complex with CD98hc on the cell

membrane and triggers amino acid uptake (28). The flow cytometry analysis of TPC-1

cells exposed to 8 Gy IR revealed significant upregulation of the

CD98 cell surface antigen compared with the non-irradiated control

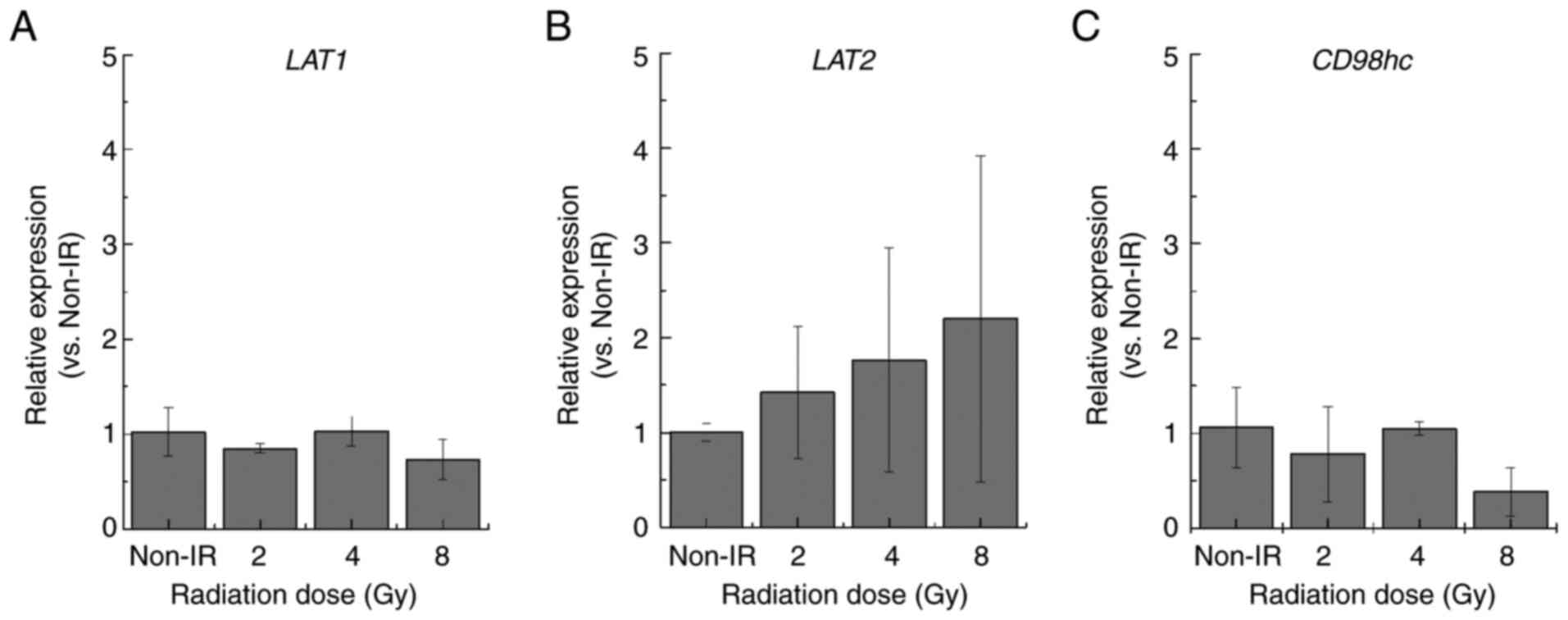

(Fig. 5). However, RT-qPCR analysis

revealed that the expression levels of the related mRNAs LAT1,

LAT2 and CD98hc were similar to those in the

non-irradiated control group (Fig.

6).

Discussion

In the present study, serum metabolomic analysis

focusing on patients with DTC and single-cell analysis using TPC-1

cells were conducted to identify Tg/Ab-independent biomarkers that

indicate the effect of thyroid cancer ablation using

131I administration under Thyrogen therapy. On day 30

post-treatment, only 1 case showed a response based on Tg levels;

however, an increase in BCAA levels, particularly valine, was

observed independently of Tg/Ab fluctuations. In the DTC cell

model, exposure to 8 Gy IR altered BPA uptake, a leucine analog

used to evaluate BCAA transport, by viable cells. While a decrease

in overall BPA uptake was observed in the total cell population,

the surviving viable cells exhibited relatively increased uptake

compared with non-irradiated controls. This apparent discrepancy

reflects the fact that IR induced substantial cell death, thereby

reducing the absolute uptake at the population level, whereas the

residual viable cells responded to radiation-induced stress with

enhanced amino acid transporter activity. Several studies have

reported a similar phenomenon. Bo et al (29) reported that LAT1-mediated amino acid

uptake in pancreatic and lung cancer cells was enhanced under

conditions of both a high dose rate (such as increased radiation

flux or greater dose delivery per unit time) and a high accumulated

dose, suggesting that transporter activity is influenced by both

the dose rate and the cumulative radiation dose. Additionally,

their cells exhibited increased radiosensitivity due to the

inhibition of LAT1 expression. The present study demonstrated BPA

uptake in TPC-1 cells was predominantly downregulated following

exposure to 8 Gy IR, although a relative increase was observed in

the surviving viable cell fraction. LAT1 overexpression has been

reported to increase BCAA uptake in hepatocellular carcinoma

(30,31). While LAT1 functions as a transporter

only when complexed with CD98hc on the cell membrane (32), forming a functional heterodimer

essential for plasma membrane localization and activity (28), quantitative assessment of this

heterodimer via western blotting using whole-cell lysates remains

challenging, as membrane-bound and intracellular protein fractions

cannot be distinguished, and therefore, do not accurately reflect

surface expression (33,34). By contrast, flow cytometry allows

for the direct evaluation of membrane-localized LAT1, which is

closely associated with CD98hc-mediated transport activity

(35,36). Therefore, flow cytometry was used to

evaluate functional upregulation of LAT1/CD98hc at the cell

surface. Nevertheless, further studies incorporating membrane

protein isolation and direct analysis of CD98hc expression are

warranted to fully validate the mechanistic role of this

transporter system in response to irradiation.

Yoshida et al (37) and Matsuya et al (38) reported that the BPA uptake in tumor

cells was highest in the G2/M phase compared with other

cell cycle phases. These findings and those of the present study

indicate that the cellular uptake and serum concentration of BCAAs

are involved in LAT1 expression and cell cycle distribution.

Conversely, elevated blood BCAA levels have been reported in

patients with obesity, insulin resistance and cardiovascular

disease (39,40). However, the 3 DTC cases in the

present study did not have these conditions. High LAT1 expression

has been reported in PTC (41).

Based on these findings, the upregulation of serum valine (one of

the BCAAs) after 131I treatment with Thyrogen, as shown

in the patient analysis in the present study, may reflect the fact

that valine was not taken up by the tumor. Although leucine and

isoleucine also showed an increasing trend, these changes were not

statistically significant. These BCAA changes may reflect reduced

tumor burden, although direct histopathological confirmation is

lacking. In the present in vitro experiments, an X-ray dose

of 8 Gy was selected based on the clonogenic survival curve of

TPC-1 cells, which showed ~1% survival at this dose. This dose was

sufficient to elicit measurable biological responses, including

changes in amino acid uptake, and is commonly used in mechanistic

in vitro studies of DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and

radiosensitization (21,42,43).

Typically, 30–80 Gy are absorbed by the residual thyroid tissue in

patients receiving 131I (1.11 GBq) under Thyrogen

stimulation depending on remnant size, iodine uptake and kinetics,

as calculated using the International Commission on Radiological

Protection Publication 106 (44).

However, administration of such high doses is not feasible in cell

culture due to excessive cytotoxicity (45). Therefore, the use of 8 Gy in the

present study represents a biologically relevant and experimentally

practical model for evaluating the cellular response to therapeutic

radioiodine exposure.

Although 131I is clinically relevant, its

uptake relies on the functional NIS, which is minimally expressed

in certain thyroid cancer cells, including some differentiated

thyroid carcinoma cell lines (3,4).

Consequently, 131I-based radiation delivery in such

in vitro models would be highly variable and non-uniform,

reflecting differences in remnant tissue uptake and iodine kinetics

observed clinically (5,19,20).

By contrast, X-rays provide consistent and uniform exposure in cell

culture, making them a practical alternative to assess general

radiation-induced stress responses (21,42).

While X-rays do not replicate the β-particle emissions or

NIS-mediated intracellular effects of 131I, the present

approach offers a feasible and relevant model to evaluate

LAT1/CD98hc-mediated responses to cytotoxic stress. Future studies

using NIS-overexpressing cells or direct 131I labeling

will be necessary to clarify 131I-specific mechanisms.

However, the biological effects of 131I, primarily

through β-particle emissions and active uptake via NIS, are not

fully recapitulated by X-ray irradiation (3,5,19,20).

The use of TPC-1 cells, which express minimal NIS, limits direct

131I uptake, rendering 131I exposure

inconsistent and technically challenging for in vitro

assays. X-ray irradiation, by contrast, provides a uniform,

controllable and reproducible source of IR that induces cytotoxic

stress independently of NIS-mediated uptake (21,42).

Additionally, the handling of 131I in cell culture

requires specialized radiation safety measures, licensing and

infrastructure, which could delay exploratory mechanistic studies.

Therefore, X-rays were selected as a practical alternative to model

general IR-induced stress and to investigate the regulation of

amino acid transporter activity, particularly LAT1/CD98hc, under

controlled conditions. This is a limitation of the present study,

and future studies using NIS-overexpressing cells or direct

131I labeling are needed to elucidate

131I-specific mechanisms.

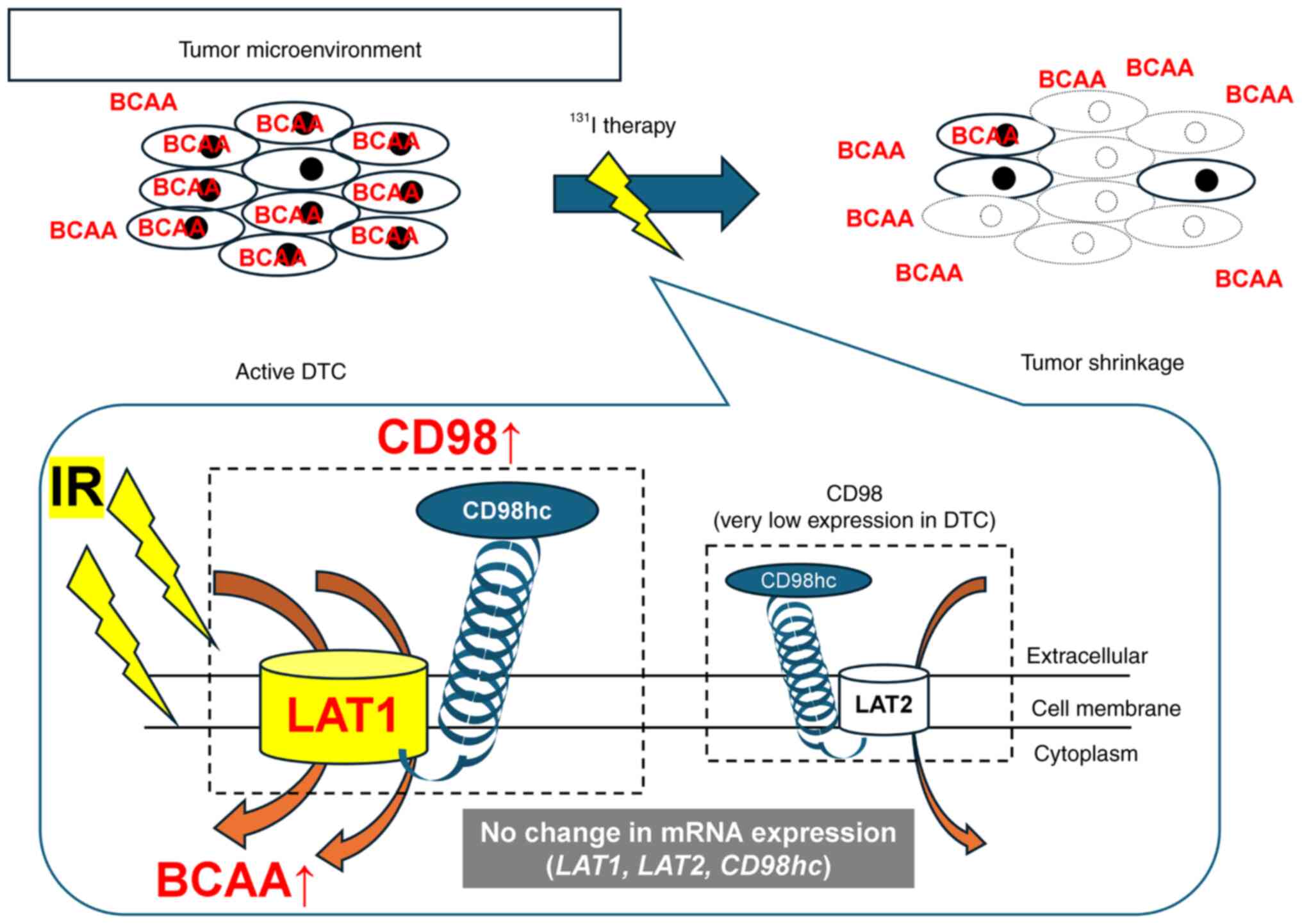

Exposure of TPC-1 cells to IR induced the expression

of the CD98 surface antigen, which may assist in increasing BCAA

uptake. BCAAs are essential amino acids mostly supplied through the

diet and taken up into tumors by the LAT1-CD98hc complex expressed

on the cell membrane (23,27,46).

Le Bricon et al (47)

performed a qualitative analysis using immunohistochemical methods

and reported no association between LAT1-positive cancer and BPA

uptake. In the present study, the expression levels of the CD98

surface antigen and related mRNAs were quantitatively examined,

which is a novel finding. Furthermore, the mRNA expression levels

of LAT1, LAT2 and CD98hc did not change under

exposure to IR based on RT-qPCR. Although LAT1 and

LAT2 mRNA levels were unchanged, membrane or total protein

expression was not assessed due to methodological limitations.

Future studies involving membrane protein isolation are needed to

clarify whether surface expression of LAT1/LAT2 is altered by

irradiation. These findings indicate that the increase in BCAA

uptake following IR is a temporary response driven by LAT1 protein

already present in the cells, rather than by newly transcribed

LAT1 mRNA. However, further studies are needed to elucidate

its molecular mechanism. Furthermore, the interpretation of the

increase in serum BCAA levels remains speculative, as

histopathological confirmation of the tumor response was not

performed in the present study, which analyzed patient samples

collected with clinical follow up after obtaining informed consent

and ethics approval. The observed changes in BCAA levels may

reflect either the release of metabolites from damaged tumor cells

or systemic metabolic shifts associated with reduced tumor burden.

Although elevated serum BCAA levels may reflect reduced tumor

uptake due to LAT1 downregulation, this interpretation should be

made with caution, since BCAA levels are also influenced by dietary

intake, gastrointestinal absorption, hepatic metabolism and

systemic inflammation, including cytokine activity (such as TNF-α),

which affects amino acid utilization and appetite (39,40).

Furthermore, while LAT1 was upregulated in PTC in previous studies

(48,49), its overall contribution to systemic

BCAA regulation remains unclear. In the present cases, there was no

clinical evidence of recurrence; thus, BCAA changes may reflect

systemic metabolic adaptations rather than direct tumor shrinkage.

The present in vitro data suggested that LAT1/CD98-mediated

BCAA uptake represents a mechanism of stress adaptation in

surviving cells; however, validation with tissue-level evidence is

warranted. This limitation should be addressed in a future

prospective cohort study.

Previous studies have demonstrated that LAT1

expression was upregulated in aggressive variants of DTC and was

associated with increased tumor cell proliferation and

dedifferentiation, particularly in BRAF-mutant PTC (48,49).

This upregulation facilitates increased uptake of essential amino

acids, such as BCAAs, supporting tumor metabolism and growth

(25,34,35).

In this context, the elevated serum BCAA levels observed after

131I treatment may reflect reduced tumor burden and

decreased LAT1-mediated amino acid uptake, rather than a mere

passive bystander effect. Although the present findings did not

establish causality, the consistent increase in serum BCAA

concentrations following radioiodine therapy in all patients

suggests potential utility as a surrogate biomarker for treatment

efficacy. Furthermore, preclinical studies have demonstrated that

LAT1 inhibition suppresses tumor growth in thyroid carcinoma

(48,49) and hepatocellular carcinoma (30), and has also been implicated in

several other cancer types (25,35).

Furthermore, LAT1 blockade has been shown to sensitize cancer cells

to radiation (29). As summarized

in Fig. 7, BCAAs are transported

into tumor cells via the LAT1/CD98 complex, IR exposure can

transiently increase BCAA uptake in surviving cells, and reduced

tumor uptake after 131I therapy may elevate serum BCAA

levels. This integrative mechanism highlights the link between LAT1

activity, amino acid metabolism and treatment response. These

observations raise the possibility that LAT1 inhibition could

potentiate the therapeutic efficacy of 131I in DTC,

especially in tumors with high LAT1 expression (Fig. 7). Further studies are needed to

evaluate the translational potential of combining LAT1 inhibitors

with radioiodine therapy.

The present study has several limitations. First,

the number of patients was small (n=3), which inevitably reduced

the statistical power of the clinical findings. Nevertheless, in

the absence of prior data on fluctuations in serum BCAA levels in

Tg/Ab-positive DTC, this work was designed as a proof-of-concept

study. The observed clinical trends were supported by mechanistic

experiments using the TPC-1 cell line, which reinforced the

biological relevance of BCAA metabolism as a potential surrogate

marker of the efficacy of radioiodine therapy. Second, dietary

intake of BCAAs was not assessed, which could affect the

interpretation of serum metabolite levels. Although all patients

fasted for ≥6 h before serum sampling to minimize acute

postprandial effects, the influence of habitual dietary intake

cannot be completely excluded. To address this, standardized

dietary questionnaires or controlled dietary interventions should

be incorporated in future studies to clarify the extent to which

serum BCAA levels reflect tumor-related metabolic changes rather

than nutritional variability. Future studies are also needed to

determine whether elevated serum BCAA levels following radioiodine

therapy reflect direct release from dying tumor cells, systemic

metabolic adaptations due to reduced tumor burden or altered

transporter activity in surviving cells. Analysis of associations

with tumor histopathology, imaging-based assessments of tumor

volume and LAT1/CD98hc expression in clinical specimens will be

critical to establish mechanistic links. Additionally, prospective

cohort studies with larger sample sizes and standardized dietary

assessments are warranted to validate BCAAs as a reliable biomarker

for therapeutic efficacy in DTC. Despite unchanged mRNA levels of

LAT1, LAT2 and CD98hc following IR, flow cytometry

demonstrated increased CD98hc surface expression, suggesting

post-transcriptional regulation, such as membrane translocation.

Notably, the present study assessed mRNA levels at a limited number

of time points, which were selected based on feasibility and

previous reports (42,43). It is possible that transient

fluctuations in gene expression at other time points were missed.

Furthermore, radiation-induced gene expression is known to be both

dose- and time-dependent (42,43).

Further studies are needed to clarify the temporal dynamics of

LAT1/CD98hc regulation by evaluating a broader range of radiation

doses and time points, and to investigate the mechanistic basis of

membrane translocation and its functional consequences in amino

acid transport activity.

In patients who are Tg/Ab-positive, monitoring of

serum Tg levels can be unreliable due to antibody interference

(6–8). The present results suggested that BCAA

levels may serve as a complementary biomarker to Tg, providing

additional information independent of Tg/Ab status. However,

further validation in larger cohorts is necessary to determine

whether BCAA monitoring could eventually replace or supplement Tg

measurements in clinical practice.

In conclusion, the present findings suggested that

an increased extracellular concentration of BCAAs following

131I therapy may reflect a decrease in residual DTC

tissue, and thus, may serve as a clinically useful surrogate marker

of therapeutic efficacy, particularly in patients for whom

traditional Tg-based monitoring is unreliable.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Miyu Miyazaki

(Scientific Research Facility Center of Hirosaki University

Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki, Aomori, Japan) for help with

the mass spectrometry, and Mrs. Suzuna Doi (Department of Radiation

Science, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Health Sciences,

Hirosaki, Aomori, Japan) for her assistance with fluorescence

measurements using a microplate reader.

Funding

The present study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grants-in-Aid

for Scientific Research (B) (project no. 21H02861/23K21419) and

Takeda Science Foundation 2023.

Availability of data and materials

The metabolomics data generated in the present study

may be found in the MetaboBank database under accession numbers

MTBKS257 and MTBKS258 or at the following URLs: https://ddbj.nig.ac.jp/public/metabobank/study/MTBKS257/

and https://ddbj.nig.ac.jp/public/metabobank/study/MTBKS258/.

All other data generated in the present study are included in the

figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

AK, YM, AW and SM designed the study, drafted the

manuscript and actively participated in its revision. AK, YT, RS,

YM and SM examined and analyzed the experimental data. YT, YM, AW

and SM oversaw the study, and provided final approval of the

version submitted and published. YM and SM confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Committee of

Medical Ethics of the Hirosaki University Graduate School of Health

Sciences (approval no. 2021-050; Hirosaki, Japan). Written informed

consent was obtained from all participants after providing a

detailed verbal explanation, and all collected data were anonymized

and handled in accordance with ethical guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Nabhan F, Dedhia PH and Ringel MD: Thyroid

cancer, recent advances in diagnosis and therapy. Int J Cancer.

149:984–992. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty

GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM,

Schlumberger M, et al: 2015 American thyroid association management

guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and

differentiated thyroid cancer: The American thyroid association

guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid

cancer. Thyroid. 26:1–133. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Japan Associations of Endocrine Surgery

Task Force on the Guidelines for Thyroid Tumors (2024), . Clinical

practice guidelines on the management of thyroid tumors 2024. Japan

Assoc Endocr Surg. 41 (Suppl 2):S23–S42. 2024.

|

|

5

|

Hänscheid H, Lassmann M, Luster M, Thomas

SR, Pacini F, Ceccarelli C, Ladenson PW, Wahl RL, Schlumberger M,

Ricard M, et al: Iodine biokinetics and dosimetry in radioiodine

therapy of thyroid cancer: Procedures and results of a prospective

international controlled study of ablation after rhTSH or hormone

withdrawal. J Nucl Med. 47:648–654. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Stanojevic M, Savin S, Cvejic D, Djukic A,

Jeremic M and Zivancević Simonovic S: Comparison of the influence

of thyroglobulin antibodies on serum thyroglobulin values from two

different immunoassays in post surgical differentiated thyroid

carcinoma patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 23:341–346. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Spencer CA, Takeuchi M, Kazarosyan M, Wang

CC, Guttler RB, Singer PA, Fatemi S, LoPresti JS and Nicoloff JT:

Serum thyroglobulin autoantibodies: Prevalence, influence on serum

thyroglobulin measurement, and prognostic significance in patients

with differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

83:1121–1127. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Petrovic I, LoPresti J, Fatemi S,

Gianoukakis A, Burman K, Gomez-Lima CJ, Nguyen CT and Spencer CA:

Influence of thyroglobulin autoantibodies on thyroglobulin levels

measured by different methodologies: IMA, LC-MS/MS, and RIA. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 109:3254–3263. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cararo Lopes E, Sawant A, Moore D, Ke H,

Shi F, Laddha S, Chen Y, Sharma A, Naumann J, Guo JY, et al:

Integrated metabolic and genetic analysis reveals distinct features

of human differentiated thyroid cancer. Clin Transl Med.

13:e12982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Deja S, Dawiskiba T, Balcerzak W,

Orczyk-Pawiłowicz M, Głód M, Pawełka D and Młynarz P: Follicular

adenomas exhibit a unique metabolic profile. ¹H NMR studies of

thyroid lesions. PLoS One. 8:e846372013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Abraham T and Schöder H: Thyroid

cancer-indications and opportunities for positron emission

tomography/computed tomography imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 41:121–138.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Guo L, Zhang Y, Li H, Li S and Guo X:

Clinical analysis of influencing factors on therapeutic effect of

radioactive iodine therapy in thyroglobulin antibodies positive

patients with papillary thyroid cancer. J Nucl Med. 63 (Suppl

2):S30062022.

|

|

13

|

Clish CB: Metabolomics: An emerging but

powerful tool for precision medicine. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case

Stud. 1:a0005882015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yu S, Liu C, Hou Y, Li J, Guo Z, Chen X,

Zhang L, Peng S, Hong S, Xu L, et al: Integrative metabolomic

characterization identifies plasma metabolomic signature in the

diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer. Oncogene. 41:2422–2430.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jiang N, Zhang Z, Chen X, Zhang G, Wang Y,

Pan L, Yan C, Yang G, Zhao L, Han J and Xue T: Plasma lipidomics

profiling reveals biomarkers for papillary thyroid cancer

diagnosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6822692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lu J, Hu S, Miccoli P, Zeng Q, Liu S, Ran

L and Hu C: Non-invasive diagnosis of papillary thyroid

microcarcinoma: A NMR-based metabolomics approach. Oncotarget.

7:81768–81777. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Razavi SA, Mahmanzar M, Nobakht M Gh BF,

Zamani Z, Nasiri S and Hedayati M: Plasma metabolites analysis of

patients with papillary thyroid cancer: A preliminary untargeted

1H NMR-based metabolomics. J Pharm Biomed Anal.

241:1159462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Monzen S, Tatara Y, Mariya Y, Chiba M,

Wojcik A and Lundholm L: HER2-positive breast cancer that resists

therapeutic drugs and ionizing radiation releases

sphingomyelin-based molecules to circulating blood serum. Mol Clin

Oncol. 13:702020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Maxon HR, Thomas SR, Hertzberg VS,

Kereiakes JG, Chen IW, Sperling MI and Saenger EL: Relation between

effective radiation dose and outcome of radioiodine therapy for

thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 309:937–941. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Schlesinger T, Flower MA and McCready VR:

Radiation dose assessments in radioiodine (131I) therapy. 1. The

necessity for in vivo quantitation and dosimetry in the treatment

of carcinoma of the thyroid. Radiother Oncol. 14:35–41. 1989.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Franken NAP, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman

J and van Bree C: Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc.

1:2315–2319. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T,

Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M and Rozen SG: Primer3-new capabilities

and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e1152012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans

J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL,

et al: The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of

quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 55:611–622.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kanai Y: Amino acid transporter LAT1

(SLC7A5) as a molecular target for cancer diagnosis and

therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 230:1079642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wittig A, Sauerwein WA and Coderre JA:

Mechanisms of transport of p-borono-phenylalanine through the cell

membrane in vitro. Radiat Res. 153:173–180. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wongthai P, Hagiwara K, Miyoshi Y,

Wiriyasermkul P, Wei L, Ohgaki R, Kato I, Hamase K, Nagamori S and

Kanai Y: Boronophenylalanine, a boron delivery agent for boron

neutron capture therapy, is transported by ATB0,+, LAT1 and LAT2.

Cancer Sci. 106:279–286. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yan R, Zhao X, Lei J and Zhou Q: Structure

of the human LAT1-4F2hc heteromeric amino acid transporter complex.

Nature. 568:127–130. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bo T, Kobayashi S, Inanami O, Fujii J,

Nakajima O, Ito T and Yasui H: LAT1 inhibitor JPH203 sensitizes

cancer cells to radiation by enhancing radiation-induced cellular

senescence. Transl Oncol. 14:1012122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Namikawa M, Kakizaki S, Kaira K, Tojima H,

Yamazaki Y, Horiguchi N, Sato K, Oriuchi N, Tominaga H, Sunose Y,

et al: Expression of amino acid transporters (LAT1, ASCT2 and xCT)

as clinical significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res.

45:1014–1022. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ericksen RE, Lim SL, McDonnell E, Shuen

WH, Vadiveloo M, White PJ, Ding Z, Kwok R, Lee P, Radda GK, et al:

Loss of BCAA catabolism during carcinogenesis enhances mTORC1

activity and promotes tumor development and progression. Cell

Metab. 29:1151–1165.e6. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kanai Y, Segawa H, Miyamoto K, Uchino H,

Takeda E and Endou H: Expression cloning and characterization of a

transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy

chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98). J Biol Chem. 273:23629–23632. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fotiadis D, Kanai Y and Palacín M: The

SLC3 and SLC7 families of amino acid transporters. Mol Aspects Med.

34:139–158. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Napolitano L, Scalise M, Galluccio M,

Pochini L, Albanese LM and Indiveri C: LAT1 is the transport

competent unit of the LAT1/CD98 heterodimeric amino acid

transporter. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 67:25–33. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Häfliger P and Charles RP: The L-type

amino acid transporter LAT1-an emerging target in cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 20:24282019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang J, Xu Y, Li D, Fu L, Zhang X, Bao Y

and Zheng L: Review of the correlation of LAT1 with diseases:

mechanism and treatment. Front Chem. 8:5648092020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yoshida F, Matsumura A, Shibata Y,

Yamamoto T, Nakauchi H, Okumura M and Nose T: Cell cycle dependence

of boron uptake from two boron compounds used for clinical neutron

capture therapy. Cancer Lett. 187:135–141. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Matsuya Y, Sato T, Kusumoto T, Yachi Y,

Seino R, Miwa M, Ishikawa M, Matsuyama S and Fukunaga H: Cell-cycle

dependence on the biological effects of boron neutron capture

therapy and its modification by polyvinyl alcohol. Sci Rep.

14:166962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shah SH, Crosslin DR, Haynes CS, Nelson S,

Turer CB, Stevens RD, Muehlbauer MJ, Wenner BR, Bain JR, Laferrère

B, et al: Branched-chain amino acid levels are associated with

improvement in insulin resistance with weight loss. Diabetologia.

55:321–330. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

McGarrah RW and White PJ: Branched-chain

amino acids in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 20:77–89.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wittig A, Sheu-Grabellus SY, Collette L,

Moss R, Brualla L and Sauerwein W: BPA uptake does not correlate

with LAT1 and Ki67 expressions in tumor samples (results of EORTC

trial 11001). Appl Radiat Isot. 69:1807–1812. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhao H, Zhuang Y, Li R, Liu Y, Mei Z, He

Z, Zhou F and Zhou Y: Effects of different doses of X-ray

irradiation on cell apoptosis, cell cycle, DNA damage repair and

glycolysis in HeLa cells. Oncol Lett. 17:42–54. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Keam S, MacKinnon KM, D'Alonzo RA, Gill S,

Ebert MA, Nowak AK and Cook AM: Effects of photon radiation on DNA

damage, cell proliferation, cell survival, and apoptosis of murine

and human mesothelioma cell lines. Adv Radiat Oncol. 7:1010132022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

ICRP, . Radiation dose to patients from

radiopharmaceuticals. Addendum 3 to ICRP Publication 53. ICRP

Publication 106. Approved by the Commission in October 2007. Ann

ICRP. 38:1–197. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Du J, Ren W, Liu W, Zhou Y, Li Y, Lai Q,

Liu X, Chen T, Liu W, Chen Z, et al: Experimental study of

iodine-131 labeling of a novel tumor-targeting peptide, TFMP-Y4, in

the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with internal

irradiation. BMC Cancer. 25:2452025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Yan R, Li Y, Müller J, Zhang Y, Singer S,

Xia L, Zhong X, Gertsch J, Altmann KH and Zhou Q: Mechanism of

substrate transport and inhibition of the human LAT1-4F2hc amino

acid transporter. Cell Discov. 7:162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Le Bricon T, Cynober L, Field CJ and

Baracos VE: Supplemental nutrition with ornithine

alpha-ketoglutarate in rats with cancer-associated cachexia:

Surgical treatment of the tumor improves efficacy of nutritional

support. J Nutr. 125:2999–3010. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Häfliger P, Graff J, Rubin M, Stooss A,

Dettmer MS, Altmann KH, Gertsch J and Charles RP: The LAT1

inhibitor JPH203 reduces growth of thyroid carcinoma in a fully

immunocompetent mouse model. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 37:2342018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Enomoto K, Sato F, Tamagawa S, Gunduz M,

Onoda N, Uchino S, Muragaki Y and Hotomi M: A novel therapeutic

approach for anaplastic thyroid cancer through inhibition of LAT1.

Sci Rep. 9:146162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|