Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a life-threatening

hematological malignancy driven by intricate and multifactorial

pathogenic mechanisms that underlie its clinical heterogeneity and

therapeutic challenges. The Philadelphia chromosome (Ph), arising

from a reciprocal translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11.2), is detected in

up to 95% of adult CML cases (1).

This chromosomal aberration generates an abnormal BCR-ABL1

fusion transcript, with molecular detection of this transcript

serving as a key component for genetic confirmation of CML

diagnosis (2,3). Recent advancements in molecular

biology have highlighted the emerging role of atypical fusion genes

in CML pathogenesis and progression (4,5). In

Ph-positive leukemia, the canonical BCR-ABL1 fusion gene

functions as a pivotal oncogenic driver. Variable chromosomal

breakpoints within BCR and ABL1 genes result in

distinct BCR-ABL1 transcript variants and corresponding

protein isoforms (6). The

e13a2 and e14a2 subtypes represent the most prevalent

BCR-ABL1 isoforms in patients with CML, both containing

intact sequences encoding the Src homology 3 domain(SH3), SH2 and

kinase domains of ABL1. Beyond these common variants, rare

fusion genotypes including e13a3, e14a3 and e1a3 have

been documented (7,8). The e13a3 and e14a3

subtypes, characterized by the absence of ABL1 exon 2,

collectively account for <1% of CML cases (9). These atypical fusion proteins exhibit

structural and functional alterations secondary to ABL1

truncation, potentially influencing leukemia biological behavior,

therapeutic responsiveness and clinical outcomes. Recent study has

revealed that these atypical variants may regulate cellular

signaling pathways and gene expression, influencing the progression

of leukemia (3,4). Simvastatin overcomes drug resistance

in chronic myeloid leukemia cells to imatinib by inhibiting the

PI3K/AKT survival signaling pathway and downregulating its

controlled anti-apoptotic proteins (10). Simultaneously, in combination with

imatinib, it interferes with Wnt/β-catenin signaling and increases

suppressive histone modification to decrease expression of the

oncogene. Through these multi-pathway effects, it ultimately

induces mitochondrial pathway apoptosis, thereby effectively

overcoming imatinib resistance (10). Furthermore, emerging targeted

therapies for these atypical variants are under investigation,

aiming to improve patient outcomes and overcome the limitations of

current treatment strategies (11).

Multicenter studies, including the European Treatment Outcome Study

(EUTOS) collaborative network, are advancing understanding of

atypical BCR-ABL1 fusion genes in CML (4,12).

These studies have developed protocols for monitoring these

variants using advanced techniques, such as reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR, as standard methods are not

applicable because its ‘standardized’ or ‘universal’ detection

tools (primers and probes) are designed for ‘typical’ or ‘common’

fusion variants. When atypical variants are encountered, these

tools cannot bind and recognize them effectively, leading to

detection failure (false-negative results). Efforts by EUTOS are

focused on refining treatment strategies and establishing

guidelines for managing these rare variants (13).

Guidelines from organizations, including the

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, emphasize the necessity of

detecting specific recurrent genetic abnormalities in bone marrow

nucleated cells or peripheral blood leukocytes for optimal risk

stratification and treatment planning (14). Recommended methodologies include

cytogenetic analysis (karyotyping), interphase fluorescence in

situ hybridization (FISH) and RT-PCR for fusion gene detection.

Previous investigations have implemented RT-qPCR for JAK2,

Calreticulin and myeloproliferative leukemia proto-oncogene gene

analysis (15), supplemented with

specialized primer sets targeting BCR exon (e)1, 12 and 3 to

identify BCR-ABL1 breakpoints, demonstrating comprehensive

coverage of previously reported uncommon breakpoints (11,16).

Bone marrow smear examination combined with FISH and karyotyping

provides preliminary evidence of BCR-ABL1 fusion (17). Next-generation sequencing (NGS)

enables genomic analysis through fragmentation of genomic DNA or

transcriptomic RNA, library preparation and high-throughput

sequencing via fluorescence signal detection during

polymerase/ligase-mediated nucleotide incorporation (18). For non-IS standardized transcripts,

quantitative calibration and reporting methods, such as relative

ABL1 copy number analysis and laboratory-built reference

curves, are recommended for improved quantification (19). Droplet digital (dd)PCR), with its

defined detection limit and quantification limit, is a key tool for

monitoring residual disease levels in these variants, with

variant-specific primer design and stringent quality control

procedures essential to ensure accuracy. Whole-genome sequencing

(WGS) using exon capture techniques facilitates detection of

BCR-ABL1 fusions through comprehensive genomic interrogation

(20). Additional methodologies,

such as nested PCR coupled with agarose gel electrophoresis, have

utility in detecting these transcripts, offering enhanced

sensitivity and specificity compared with conventional techniques

while enabling amplification of extended DNA fragments (21). Recent guidelines from European

LeukemiaNet 2023 and EUTOS suggest regular monitoring of measurable

residual disease using advanced techniques and more frequent

follow-up for patients with atypical transcripts to improve patient

management (6,22). Ongoing multicenter collaborations,

such as the EUTOS study, are key in providing robust data on the

clinical outcomes of these variants. These studies aim to validate

the prognostic value of atypical BCR-ABL1 fusion genes and refine

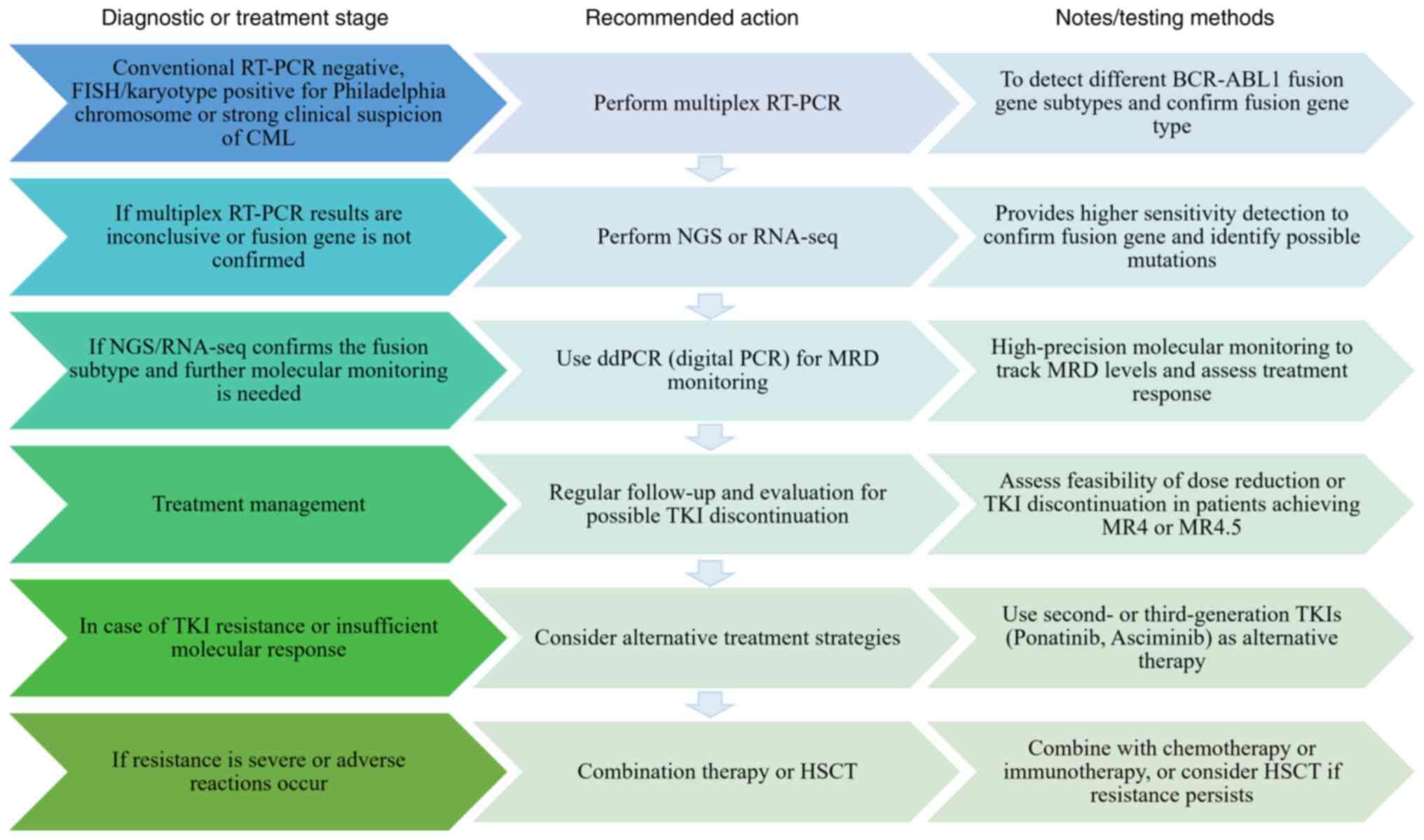

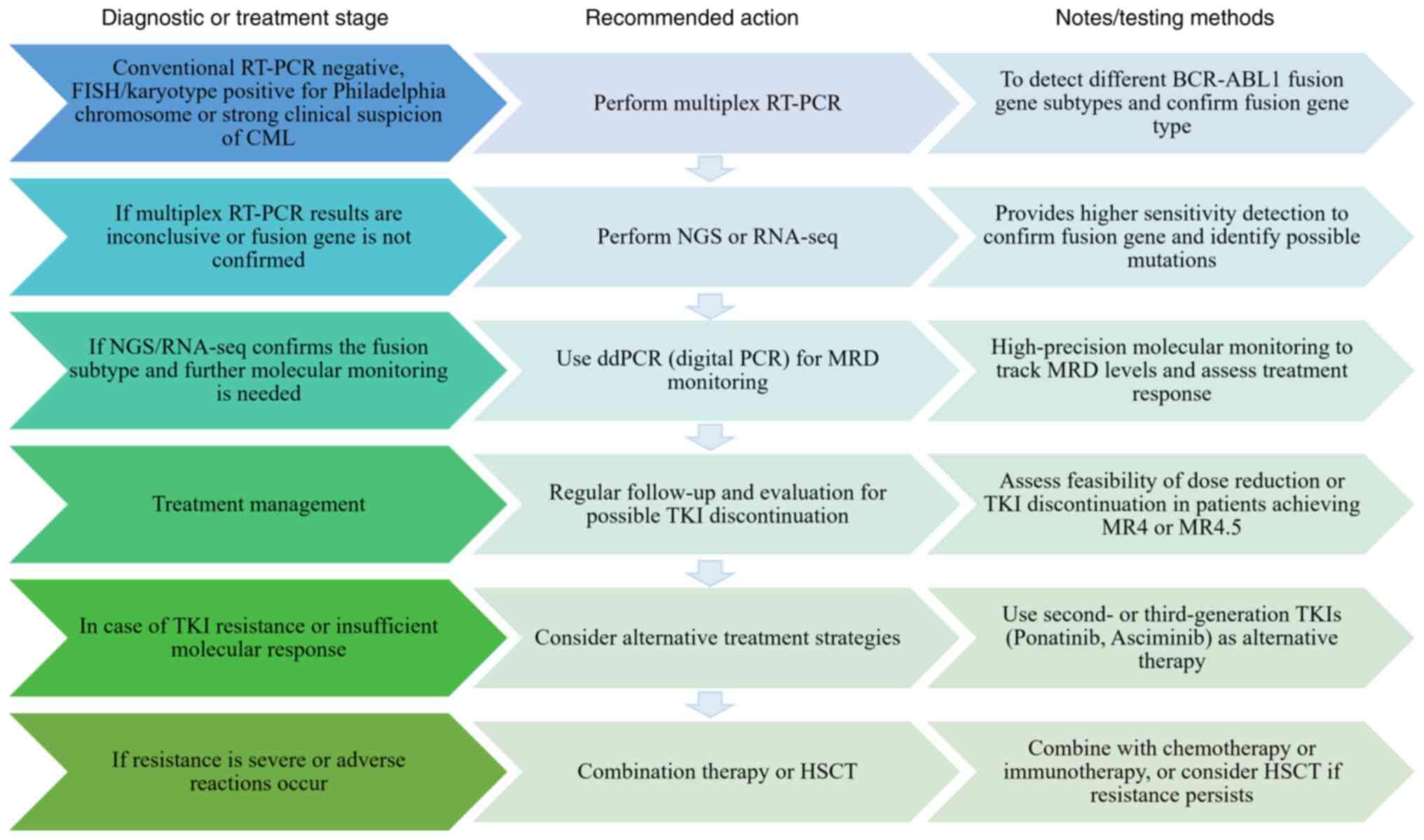

treatment strategies for these rare subtypes. Atypical

BCR-ABL1 testing should involve multiplex RT-PCR and NGS,

followed by ddPCR for minimal residual disease monitoring,

providing a structured approach to managing cases with atypical

BCR-ABL1 fusion genes (Fig.

1), with follow-up frequency and therapeutic adjustments based

on patient response.

| Figure 1.Clinical roadmap for atypical

BCR-ABL1 testing. BCR, breakpoint cluster region; ABL1,

abelson leukemia1; RT-q, reverse transcription-quantitative; NGS,

next-generation sequencing; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; TKI,

tyrosine kinase inhibitor; seq, sequencing; dd, digital droplet;

MRD, minimal residual disease; MR, molecular response; HSCT,

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. |

Current research on atypical fusion genes in

leukemia remains exploratory, with knowledge gaps persisting. The

low incidence of these genetic variants in leukemia populations has

resulted in limited case reports (23,24),

posing diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for clinicians

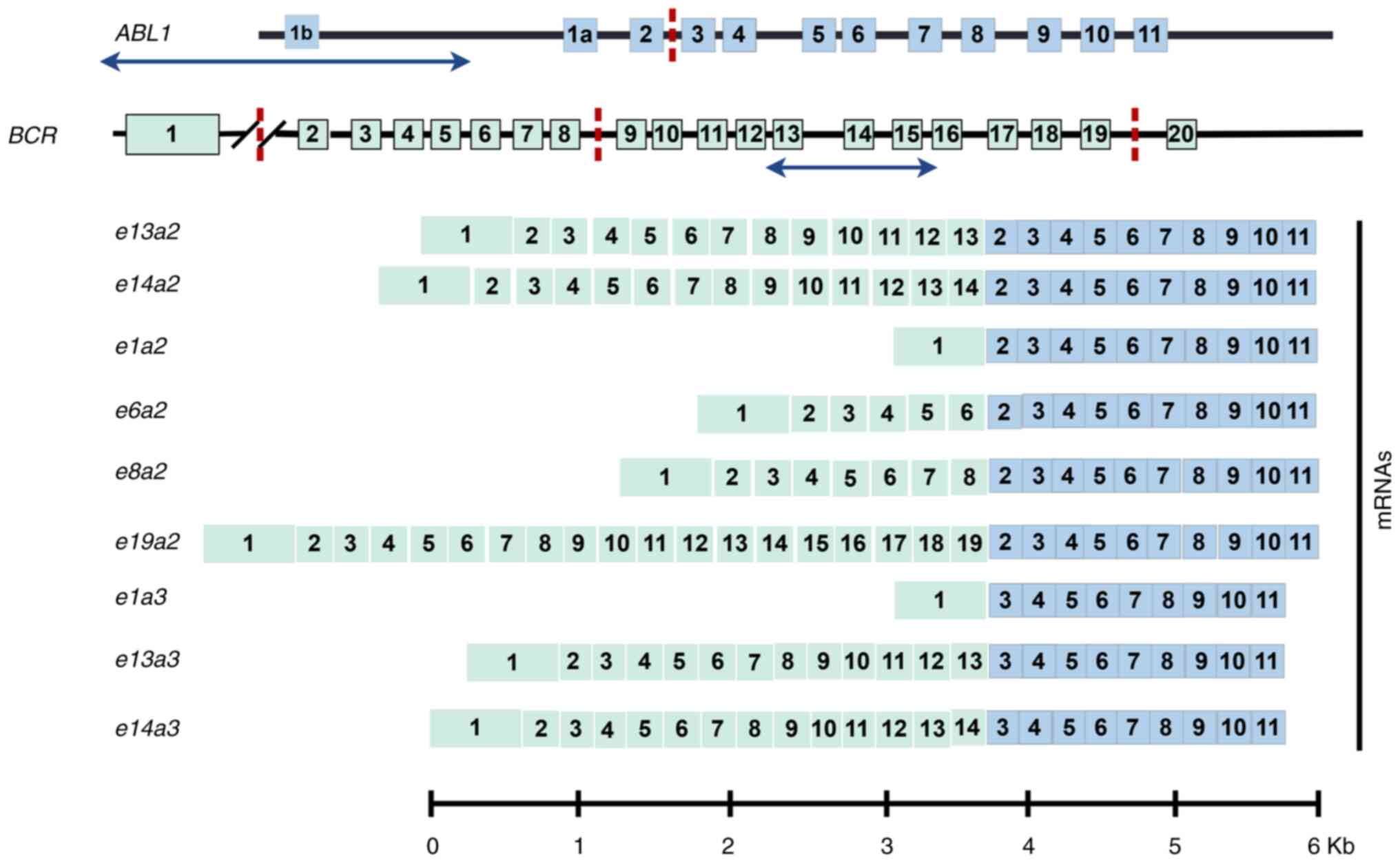

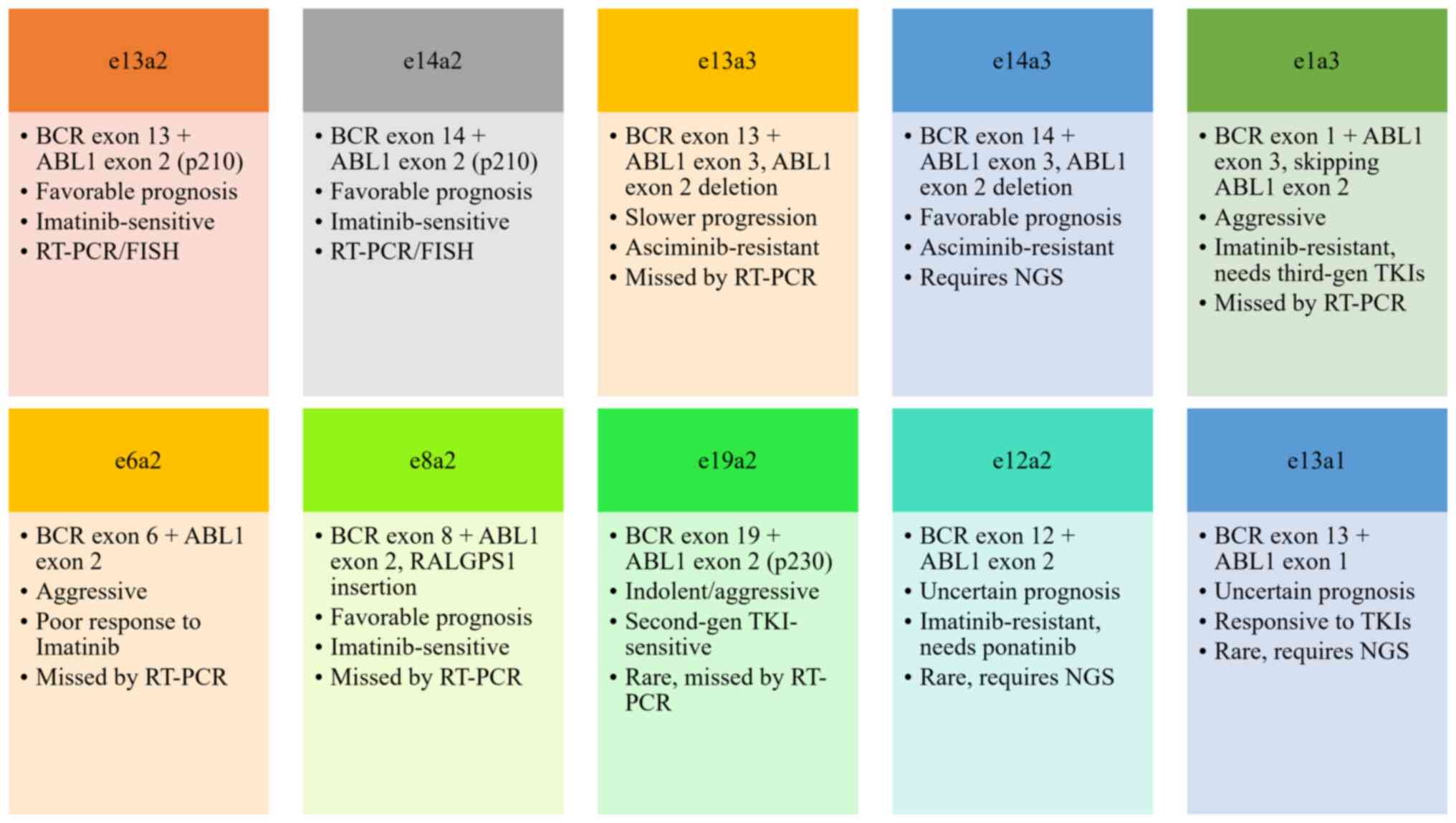

managing patients with atypical fusion-positive CML. The present

study aimed to review the structural characteristics therapeutic

management, and prognostic implications of the e13a3, e14a3,

e1a3, e1a2, e6a2, e8a2, e19a2, e12a2 and e13a1 BCR-ABL1

fusion transcripts to delineate their clinical significance

(Figs. 2 and 3).

Materials and methods

The literature search was conducted using

PubMed(pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Embase

(embase.com/landing?status=grey) and Web of

Science(webofscience.com/wos/) from January 2000 to July 2025 using

the following search strategy: ((BCR-ABL[Title/Abstract] OR

BCR::ABL1[Title/Abstract]) AND (atypical[Title/Abstract] OR

rare[Title/Abstract] OR e13a3 OR e14a3 OR e1a3 OR e1a2 OR e6a2 OR

e8a2 OR e19a2 OR e12a2 OR e18a2 OR e13a1) AND (CML[Title/Abstract]

OR ‘chronic myeloid leukemia’[MeSH Terms] OR Ph +

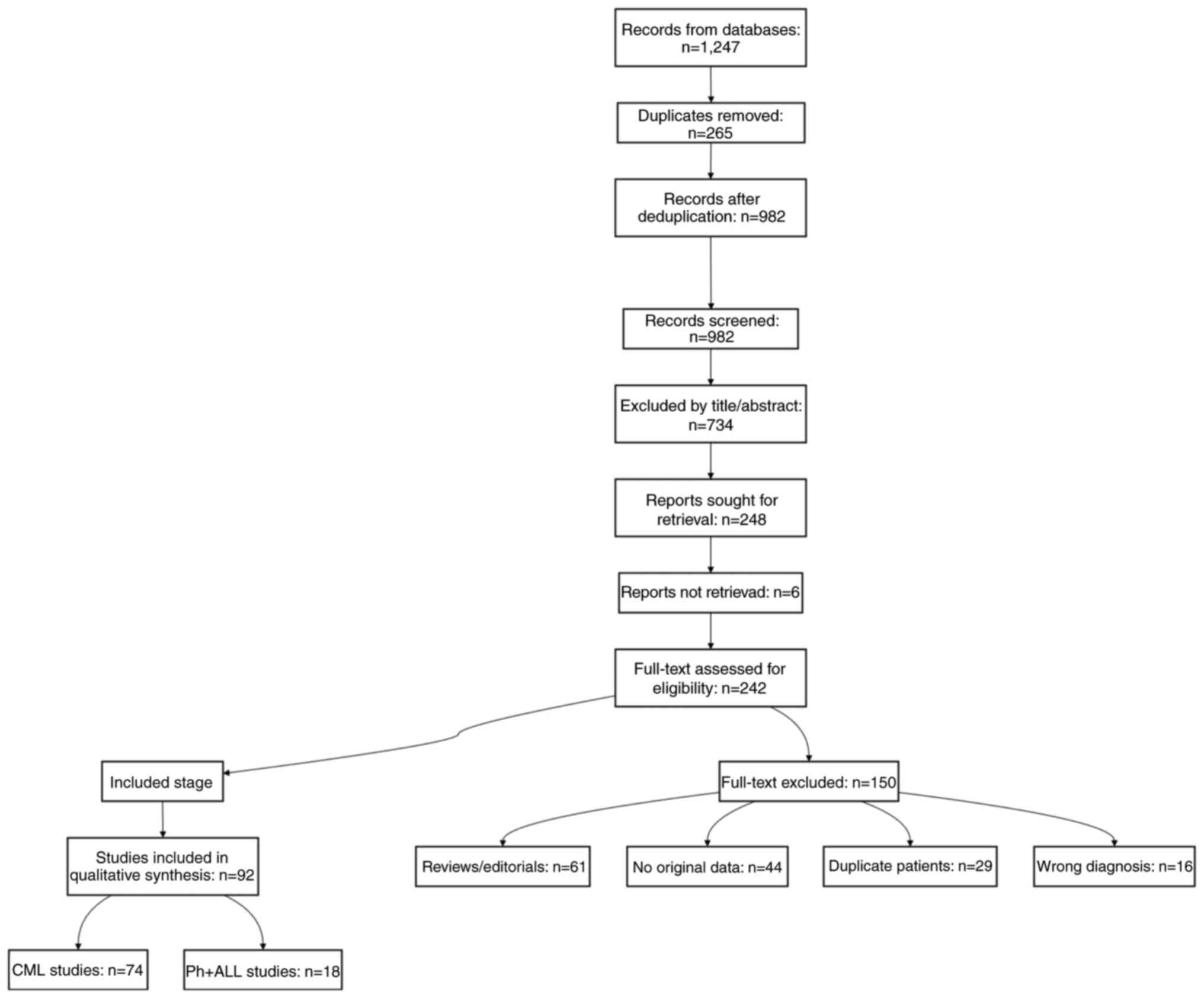

ALL[Title/Abstract]). A two-step ‘include-then-exclude’ process was

performed: All case reports, series or retrospective studies in

which atypical BCR-ABL1 transcripts were confirmed at the RNA or

DNA level, the diagnosis met World Health Organization(WHO)

criteria for CML or acute lymphoblastic leukemia(Ph+

ALL) and both treatment details and evaluable follow-up outcomes

were provided were eligible (25,26);

conversely, reviews, editorials, animal studies lacking primary

data and duplicate publications with overlapping cases were

excluded, retaining only the most complete dataset for each

patient. A total of two reviewers independently screened

titles/abstracts, extracted data. Discrepancies resolved by a third

reviewer. Because study designs varied widely, the present review

conducted a descriptive synthesis. The PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 4) documents the systematic selection

process. For each transcript subtype, the strength of evidence was

graded hierarchically: Grade A (robust), ≥10 clinically annotated

cases with a median follow-up ≥1 year; grade B (moderate), 3–9

cases or follow-up <1 year and grade C (limited), 1–2 cases or

in vitro data only (Table

I).

| Table I.Evidence levels. |

Table I.

Evidence levels.

| Subtype | Total cases

(CML/Ph+ ALL) | Evidence type | Median follow-up,

months (range) | Outcome

definition | Evidence grade | (Refs.) |

|---|

| e13a3 | 38 (34/4) | Case series | 24.0

(6.0–120.0) | CCyR, MMR, OS | B | (17,27,30,34,37,40,41,43,44) |

| e14a3 | 25 (22/3) | Case reports | 18.0

(3.0–96.0) | CCyR, MMR | B | (11,21,53–57) |

| e1a3 | 12 (9/3) | Case reports | 15.0

(3.0–60.0) | CNS relapse,

OS | C | (60,64,69,72) |

| e1a2 | 41 (41/0) | Retrospective

cohort | 69.5

(12.0–120.0) | OS, blast

crisis | A | (81,91,92,95–97) |

| e6a2 | 18 (15/3) | Case reports | 12.0

(1.0–48.0) | ASCT outcomes | C | (63,65,66,100,102–104,140) |

| e8a2 | 5 (4/1) | Case reports | 6.0 (3.0–36.0) | CHR, CMR | C | (107,109,110,116,141) |

| e19a2 | 22 (20/2) | Case series | 30.0

(6.0–108.0) | MMR, TFR | B | (118,119,121,122,125,129,142–145) |

| e12a2 | 3 (3/0) | Case reports | 72.0

(60.0–84.0) | MR4 sustained | C | (130,146) |

e13a3 variant

Structural characteristics

The e13a3 (b2a3) BCR-ABL1 transcript is

generated through direct linkage of e13 of the BCR gene to

e3 (a3) of the ABL1 gene, resulting in deletion of

ABL1 e2 (a2). This fusion produces a truncated

protein that retains constitutively activated TK activity (27). The lack of the Src homology 3 (SH3)

domain in this variant is linked to its unique structural

properties, contributing to the formation of an SH3-deficient

isoform. SH3 deficiency can impact downstream signaling, enhancing

kinase activity and potentially promoting leukemogenesis (28). SH3-deficient variants such as

e13a3 are associated with altered protein interactions and

subcellular localization, potentially affecting cell signaling

pathways and contributing to disease progression. In murine models,

e13a3, as an SH3-deficient variant, shows slower disease

progression compared with canonical isoforms, though it retains

leukemogenic potential, capable of inducing CML (29). This slower progression may be

influenced by changes in cell adhesion, which alter the interaction

between leukemic cells and the microenvironment, affecting disease

dynamics. The SH3 domain normally serves as a negative regulator of

ABL1 TK activity, and its deletion in the e13a3 variant

enhances kinase activity (7). The

e13a3 fusion breakpoint resides within the major breakpoint

cluster region, resulting in the production of a 210 kDa (p210)

fusion protein. Notably, the absence of the SH3 domain in the

truncated ABL1 moiety induces structural alterations in the

chimeric protein. This aberrant protein retains constitutively

activated TK activity, which drives leukemic cell proliferation and

inhibits differentiation (27).

Compared with canonical fusion subtypes such as e14a2 or

e13a2, this variant exhibits a unique genomic architecture

(30). The e13a3 transcript

is predominantly observed in patients with chronic phase CML, with

rare case reports in Ph chromosome-positive ALL (31–33).

Notably, a Chinese study initially failed to detect the

e13a3 fusion using RT-qPCR, underscoring the risk of missing

rare fusion subtypes when employing primer sets targeting

conventional breakpoints, even in cases with confirmed

t(9;22) translocation (17).

Conversely, another study (34)

documented a CML case with a normal karyotype and negative RT-PCR

findings, where subsequent FISH analysis revealed BCR-ABL1

fusion. This highlights the importance of multimodal diagnostic

approaches, particularly when conventional methods yield equivocal

results.

Therapeutic management

Imatinib, a first-generation TKI is widely utilized

in e13a3 variant CML. Most Ph-positive CML patients

receiving 400 mg/day imatinib achieve complete cytogenetic

remission (CCyR) within 6–12 months and maintain durable responses

(35,36). McCarron et al (37) reported a 66-year-old male patient

with Ph-positive CML who attained progressively deepening

cytogenetic responses and declining BCR-ABL1/ABL1 ratios

following sustained 400 mg/day imatinib therapy. In Ph-negative CML

cohorts (representing 5–10% of cases, characterized by

CR-ABL1 rearrangements undetectable by conventional

cytogenetics) (38,39), studies (34,40)

have evaluated second-generation TKIs including nilotinib. These

agents demonstrate efficacy in achieving CCyR and major molecular

response (MMR) in Ph-positive populations (17,27),

which is consistent with the report by Zhou et al (41). Dasatinib, another second-generation

TKI, has also been employed in this context. Mechanistic and in

vitro studies indicate that the e13a3 variant may

exhibit resistance to asciminib, with clinical evidence remaining

limited (7). Resistance observed in

e13a3 variant CML is largely based on laboratory-based

research (7,42), and there is insufficient clinical

data to support these findings.

Combination strategies integrating TKIs with

chemotherapy have been explored. One notable example is the use of

the ponatinib-fludarabine + Low-dose Cytarabine (Ara-C) +

Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor(G-CSF) + idarubicin regimen

followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT), which

resulted in molecular negativity and full donor chimerism at 19

months post-transplant in one case (43). Massimino et al (44) implemented a tailored approach in an

89-year-old male patient with mild renal impairment, including

initial hydroxyurea (2,000 mg/day) for leukocytosis management,

transitioning to dasatinib 100 mg/day, which achieved a deep

molecular response (MR), characterized by a further reduction in

transcript levels to undetectable. This strategy has also been used

in other studies (17,30).

Prognostic outcomes

Most studies suggest that e13a3-positive

patients exhibit a lower risk of progression to accelerated phase

or blast crisis, with superior long-term event-free survival

compared with rare variants such as e1a2 or e19a2

(12,45). Most patients attain deep, sustained

responses following TKI monotherapy or combination regimens. A

patient achieved complete hematological remission (CHR) at 2 months

and MMR with RT-PCR negativity by 8 months, maintaining remission

for 2 years (44). Another case

demonstrated FISH-confirmed CCyR (0% BCR-ABL1 fusion) at 6

months, sustained beyond 24 months (34). While certain TKI-treated cases

exhibit persistent low-level e13a3 transcripts despite CCyR

(37), combination therapies have

shown favorable results. In addition to treatment efficacy, it is

key to evaluate how the treatment regimen affects quality of life.

Long-term use of TKIs can lead to side effects such as chronic

fatigue, nausea and musculoskeletal pain, which may limit the

ability to perform daily tasks and participate in social activities

(46,47). Balancing treatment effectiveness

with the impact on physical and emotional wellbeing is essential

for optimal clinical decision-making. Resistance to treatment can

develop due to ABL kinase mutations such as T315I or activation of

compensatory signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT and SRC, which

allow the leukemic cells to survive despite the presence of TKIs

(48). These mechanisms of

resistance contribute to treatment failure and disease progression.

In these cases, next-generation TKIs such as ponatinib and

asciminib, which target resistant mutations, can be effective,

although they may be associated with more severe side effects

(49–51). Combining TKIs with other therapeutic

modalities, including chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation,

may be necessary for patients with resistant disease to achieve

long-term disease control (52).

Evidence on e13a3 variant outcomes is summarized in Table II. Further multi-center studies are

needed to validate these prognostic outcomes in CML.

| Table II.Summary of existing reports on cases

associated with the e13a3 variant. |

Table II.

Summary of existing reports on cases

associated with the e13a3 variant.

| Type | Country | Age, years | Sex | Method | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up

duration | Diagnosis

stage | Mutations | Adjustment |

Transplantation | Adverse

reactions | Cause of death | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CML Ph(−) | Japan | 37 | F | FISH, RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day | CHR, MMR | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Fatigue | None | (40) |

| CML Ph(−) | China | 24 | F | FISH, RT-PCR, gene

sequencing | TKI: Imatinib 400

mg/day | CCyR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Nausea | None | (34) |

| CML Ph(+) | China | 39 | M | RT-PCR, Sanger

sequencing | TKI: Nilotinib, 300

mg/day | MMR | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Fatigue | None | (41) |

| CML Ph(+) | UK | 30 | M | RT-PCR | TKI: Ponatinib, 45

mg/day. Non-TKI: FLAG-IDA, allo-ASCT | MMR | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | Allo-ASCT | Gastrointestinal

disturbances | None | (43) |

| CML Ph(+) | Japan | 49 | M | RT-PCR, FISH | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Interferon, hydroxyurea | MMR | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Nausea | None | (30) |

| CML Ph(+) | Korea | 57 | M | RT-PCR, Sanger

sequencing, multiplex RT-PCR | TKI: Nilotinib, 300

mg/day. Non-TKI: Interferon, Hydroxyurea | CCyR, MMR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Fatigue | None | (27) |

| CML Ph(+) | China | 32 | M | RT-qPCR, FISH,

karyotype analysis | TKI: 300 mg/day

nilotinib. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | CCyR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Gastrointestinal

disturbances | None | (17) |

| CML Ph(+) | Italy | 89 | M | G-banding,

multiplex RT-PCR, Sanger sequencing | TKI: Dasatinib, 50

mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | CCyR, but e13a3

BCR-ABL1 transcript remains | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Nausea | None | (44) |

| CML Ph(+) | Ireland | 66 | M | Genetic analysis,

qPCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day | BCR-ABL1

transcripts are decreased | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Nausea | None | (37) |

e14a3 variant

Structural characteristics

In this fusion transcript, the ABL1

breakpoint resides within intron 2, generating a chimeric mRNA

linking BCR e14 to ABL1 e3. This rearrangement

induces structural and functional alterations in the fusion

protein, dysregulating intracellular signaling pathways to promote

leukemic cell proliferation, survival and immune evasion. A

previous study employed customized RT-PCR coupled with Sanger

sequencing to confirm this fusion mRNA (53), concurrently identifying

non-synonymous mutations in TP53, FMS-like tyrosine kinase

3, KIT Proto-Oncogene, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase(KIT) and

paired box 5, underscoring the molecular heterogeneity. Another

case report documented methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation

in a patient with CML harboring this BCR-ABL1 fusion,

providing insights for future investigations (54). A study identified a BCR-ABL1

fusion in a rare CML case, where the breakpoints occurred at

BCR intron 14 and ABL1 intron 2, using NGS (53). This unique fusion led to a

compromised SH3 domain, which was associated with altered drug

response and distinct clinical manifestations (53). These findings emphasize the critical

role of SH3 domain loss in modulating therapeutic outcomes and the

molecular heterogeneity underlying CML.

Therapeutic management

TKI monotherapy with imatinib or nilotinib has been

used in e14a3-positive cases. A Chinese study (11) reported a 67-year-old Ph-positive

female with coexisting e13a3 and e14a3 variants, the

first documented instance of dual rare BCR-ABL1 fusions in

China, who achieved therapeutic response with imatinib. Vaniawala

et al (55) reported

e14a3 BCR-ABL1 fusion in a 30-year-old male managed solely

with imatinib. Nilotinib was similarly employed to treat a

52-year-old male by Massimino et al (56), with both cases achieving a treatment

response.

Personalized combination regimens have also been

explored. In a study by Lyu et al (53), hydroxyurea was initially

administered for rapid leukocytosis control prior to TKI

initiation, with subsequent imatinib dose reduction (from 400 to

300 mg/day) due to intolerance, emphasizing individualized dosing.

A previous study (57) reported

sequential intolerance to imatinib and dasatinib, ultimately

transitioning to hydroxyurea monotherapy.

Prognostic outcomes

Most patients with e14a3 variant CML exhibit

favorable prognoses, achieving sustained hematological, cytogenetic

and molecular remissions. In a Chinese cohort (11), imatinib monotherapy induced rapid

MR, with CCyR attainment within 3 months and notable

BCR-ABL1-e14a3 transcript reduction. Nilotinib-treated cases

similarly demonstrated favorable outcomes (56). Combination regimens have shown

variable efficacy: One study reported TKI monotherapy achieving CHR

at 2 months, MMR at 3 months and sustained transcript negativity

for 9 years without kinase domain mutations (21). Adjuvant agents such as interferon,

hydroxyurea, and aspirin were incorporated, though immunomodulatory

effects of interferon yielded inconsistent results compared with

prior reports (57,58). Conversely, a patient requiring

hydroxyurea-nilotinib combination therapy achieved hematological

and molecular remission after dose adjustment (54). Key e14a3 variant case reports

and outcomes are summarized in Table

III.

| Table III.Summary of existing reports on cases

associated with the e14a3 variant. |

Table III.

Summary of existing reports on cases

associated with the e14a3 variant.

| Type | Country | Age, years | Sex | Method | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up

duration | Diagnosis

stage | Mutations | Adjustment |

Transplantation | Adverse

reactions | Cause of death | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CML Ph(+) | China | 24 | M | RT-PCR, Sanger

sequencing, NGS | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non- TKI: Hydroxyurea | Imatinib is

tolerated after lowering the dosage | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | Dose was decreased

to 300 mg/day | No

transplantation | Fatigue | None | (53) |

| CML Ph(+) | USA | 81 | M | FISH, Cytogenetic

analysis, RT-qPCR, DNA Sequencing | TKI: Dasatinib, 50

mg/day; imatinib, 400 mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | PCyR | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Fatigue,

gastrointestinal disturbances | None | (57) |

| CML Ph(+) | USA | 54 | F | RT-qPCR, FISH | TKI: Nilotinib, 300

mg/day Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | CHR, MMR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Nausea,

fatigue | None | (54) |

| CML Ph(+) | China | 67 | F | RT-qPCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day | CCyR | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Fatigue | None | (11) |

| CML Ph(+) | China | 41 | F | FISH, nested PCR,

qPCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; dasatinib, 50 mg/day; nilotinib, 300 mg/day. Non-TKI:

Hydroxyurea, interferon | MMR | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Gastrointestinal

disturbances | None | (21) |

| CML Ph(+) | Italy | 52 | M | Cytogenetic

analysis, multiplex, RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; dasatinib, 50 mg/day; nilotinib 300 mg/day | CHR, CCyR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Nausea,

fatigue | None | (56) |

| CML Ph(+) | India | 30 | M | Cytogenetic

analysis, FISH, RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Allo-ASCT | CHR | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | Allo-ASCT | None | None | (55) |

e1a3 variant

Structural characteristics

The e1a3 transcript arises from direct fusion

of e1 of the BCR gene to e3 (a3) of the

ABL1 gene, skipping ABL1 e2 (a2). This structural

alteration results in a truncated fusion protein lacking

approximately two-thirds of the sequence encoding the SH3 domain

within the ABL1 moiety (8).

Distinct from common variants, its unique fusion junction may

perturb subcellular localization, substrate specificity and

signaling pathways, thereby disrupting cellular homeostasis. This

transcript is relatively rare, with a single case (4.8%) identified

among patients with CML in a Syrian study (59). Additionally, its occurrence has been

documented in Ph+ ALL and AML (31). Some researchers have posited that a

subset of e1a3 BCR-ABL1-positive ALL cases may represent

undiagnosed CML in lymphoid blast crisis, requiring exclusion

through comprehensive clinical history review (60). A previous study (61) identified multiple atypical

BCR-ABL1 transcripts in CML, challenging prior assumptions

of singular fusion dominance. Conventional RT-PCR frequently fails

to detect these transcripts, often yielding false-negative results

(62), while RNA sequencing

(RNA-seq) uncovers their presence, highlighting the necessity for

advanced molecular diagnostics in clinical practice. The

e1a3 and e6a2 BCR-ABL1 transcripts are characterized

by unique fusion breakpoints within the ABL1 gene (63,64).

These isoforms are less common and associated with more aggressive

disease progression, including early blast crisis and resistance to

standard TKIs (65,66). These isoforms demonstrate TKI

resistance and often require multimodal therapy, including the use

of third-generation TKIs or stem cell transplantation (67,68).

Therapeutic strategies

Unlike e13a3 and e14a3 variants, dasatinib serves as

the primary TKI for e1a3-positive CML. The majority of reported

cases demonstrate an indolent clinical course (62,69). A

previous study (64) reported a

patient achieving CCyR following immediate dasatinib initiation

(140 mg/day). An 80-year-old Ph-positive male treated with 400

mg/day imatinib attained rapid CCyR and hematological normalization

but subsequently developed lymphoblastic crisis at 5 months,

suggesting a risk of ALL transformation (8). Combination therapies, including

dasatinib with nilotinib or ponatinib, have shown variable efficacy

(68,70); the T315I mutation frequently serves

as the primary resistance mechanism, necessitating the switch to

third-generation TKIs (71).

Innovative approaches, such as third-generation TKIs

combined with ASCT, have been employed in a previous study

(72). A 56-year-old female patient

maintained disease-free status post-ASCT with continued

olverembatinib therapy, underscoring the potential of

next-generation TKIs and ASCT in managing this rare subtype

(72).

Prognostic outcomes

Prognoses for e1a3 variant CML patients

exhibit marked heterogeneity. A Japanese male (64) achieved CCyR by 6 months with

dasatinib, despite presenting with extramedullary leukemia lacking

leukocytosis, which is rare in CML. A previous case (72) demonstrated sustained remission

post-ASCT and olverembatinib maintenance, yet developed isolated

central nervous system (CNS) infiltration without

hematological/cytogenetic relapse, implicating the CNS as a

potential sanctuary site. Due to the blood-brain barrier and

relatively immune-privileged status, conventional systemically

administered chemotherapeutic and targeted therapeutic agents often

fail to achieve effective concentrations within the CNS. This

allows cancer cells to evade treatment, survive, and cause a

relapse in this sanctuary site, while the rest of the body may

still be in a state of remission. A patient harboring the

e1a3 fusion, typically associated with aggressive disease,

maintained stable, untreated CML, challenging the association

between BCR-ABL1 variants and clinical severity (64). Key e1a3 variant case reports

and outcomes are summarized in Table

IV.

| Table IV.Cases associated with the e1a3

variant. |

Table IV.

Cases associated with the e1a3

variant.

| Type | Country | Age, years | Gender | Method | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up

duration | Diagnosis

stage | Mutations | Adjustment |

Transplantation | Adverse

reactions | Cause of death | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CML Ph(+) | Japan | 49 | M | FISH, RT-PCR,

Sanger Sequencing | TKI: Dasatinib, 50

mg/day | CCyR | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Fatigue, mild

nausea | None | (64) |

| CML Ph(+) | Spain | 80 | M | FISH, RT-PCR,

Cytomolecular assays | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day | Lymphoblastic

crisis | 6 months | Blast crisis | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Severe fatigue,

gastrointestinal disturbances | Lymphoblastic

transformation | (60) |

| CML Ph(+) | Spain | 75 | F | RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day | In good

condition | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No TKI | No treatment | No

transplantation | None | (69) |

| CML Ph(+) | China | 56 | F | FISH, RT-PCR,

FC | TKI: Flumatinib, 50

mg/day; orebatinib, 50 mg/day. Non-TKI: Chemotherapy,

allo-ASCT | Disease-free | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | Yes, Allo-ASCT | None | None | (71) |

e1a2 variant

Structural characteristics

The e1a2 variant arises from fusion between

e1 of the BCR gene and e2 of the ABL1 gene,

generating a chimeric protein with distinct structural and

functional properties. By contrast with the canonical p210 isoform,

the p190 variant lacks central e13 and 14 of the BCR gene.

Despite this truncation, the p190 fusion protein retains notably

enhanced TK activity, which remains sufficient to drive

leukemogenesis (73,74). The e1a2 transcript is rare in

CML, accounting for ~1.8% of cases in a cohort of 2,322 patients

treated with TKIs, including 1,326 male and 996 female patients,

with a median age of 48 years (range 18–88) (14,75),

In the aforementioned study, 41 patients (1.8%) exhibited the

e1a2 fusion, confirmed by RT-PCR. This variant is associated

with a distinct phenotype marked by monocytosis, absence of

basophilia and blast crisis presentation at initial diagnosis in

61% of cases, significantly higher than in patients with canonical

transcripts (76). In a study by

Gong et al (52), 16 of 41

patients with the e1a2 transcript presented with blast

crisis at initial diagnosis, two had accelerated phase and 23 were

in chronic phase (76) The

frequency of monocytosis at initial diagnosis was confirmed in 10

patients with available blood counts, showing a median of 11.5%

(range, 5–36%), with seven patients exhibiting monocytosis >10%

(76). In Ph-positive adult ALL,

the e1a2 variant accounts for 61.2% of cases, as reported in

a national cohort of 67 patients with Ph+ ALL, and is

typically associated with elevated leukocyte count and lymphoid

lineage differentiation (77).

RT-PCR for BCR-ABL1 detection, and Sanger sequencing are

employed to confirm atypical fusion transcripts.

Therapeutic strategies

Imatinib remains the primary therapeutic agent for

e1a2-positive leukemia. A standard initial dose of 400

mg/day is administered in patients with ALL and CML, with dose

escalation or TKI switching considered for suboptimal responders.

However, it is important to consider the impact of side effects on

daily life (78). Common adverse

reactions such as fatigue, gastrointestinal disturbance and skin

rashes can significantly disrupt daily activities and affect the

overall quality of life (79).

These side effects should be weighed when selecting the most

appropriate treatment regimen, and supportive care may be necessary

to improve patient comfort during therapy (80). A previous study (81) documented a patient with Ph-negative

CML achieving molecular remission (undetectable e1a2

BCR-ABL1 by RT-PCR) after 2 months of imatinib monotherapy,

alongside rare cyclical leukocyte fluctuations and spontaneous

normalization without intervention. However, resistance to TKIs is

a major challenge, particularly in patients with mutations in the

ABL kinase domain, such as the T315I mutation, which notably

impairs the binding of TKIs to the BCR-ABL1 fusion protein

(82,83). These mutations lead to decreased

efficacy of first- and second-generation TKIs. Additionally,

compensatory signaling pathways, including the PI3K/AKT and SRC

kinase pathways, may be activated, allowing leukemic cells to

bypass the inhibition of BCR-ABL1, contributing to treatment

resistance (84). To overcome these

mechanisms of resistance, third-generation TKIs such as ponatinib

and asciminib, which are designed to target BCR-ABL1 with

T315I mutations and other resistant forms, show promising results

(50,51,85).

However, these agents also cause more severe side effects,

including cardiovascular complications, which should be managed.

Combining TKIs with other therapeutic strategies, such as

chemotherapy or immunotherapy, may provide an alternative approach

to overcome resistance, but this requires consideration of the

risk-to-benefit ratio for each patient (86–89).

Combination approaches are frequently employed,

often incorporating consolidation chemotherapy post-remission

(68,90). Japanese protocols (91) combine hydroxyurea with TKIs. For

relapsed/refractory cases, TKI substitution or chemotherapy

intensification may be pursued. A previous study (92) reported initial imatinib-induced

symptom resolution and 2.5-log BCR-ABL1 reduction, followed

by leukemic transformation at 6 months necessitating high-dose

chemotherapy and nilotinib. Transcript isoform switching may be a

potential molecular mechanism underlying disease recurrence

(93).

Prognostic outcomes

Prognostic heterogeneity characterizes e1a2

variant CML. While some patients achieve durable remission with

imatinib-based regimens (81,92,94,95),

clonal dynamics complicate outcomes. Multivariable analyses have

confirmed that e1a2 BCR-ABL1 serves as an independent

adverse prognostic factor, with a median OS of 69.5 months. Given

its clinical behavior resembling Ph-positive ALL, certain

researchers advocate classifying e1a2 as a distinct

high-risk subtype of CML (76). One

case (96) harbored dual

e13a3 and e1a2 clones, developing imatinib resistance

linked to e1a2 persistence despite achieving CHR, ultimately

progressing to blast crisis and death. Notably, resistance occurred

without ABL1 kinase domain mutations, suggesting alternative

mechanisms. A separate study (97)

described extramedullary blast crisis at TKI initiation, mirroring

e1a3 cases, yet subsequent multimodal therapy (TKIs, ASCT)

achieved sustained complete molecular remission (CMR) for >48

months. These findings underscore the necessity for comprehensive

molecular monitoring and adaptive therapeutic strategies. Key

e1a2 variant case reports and outcomes are summarized in

Table V.

| Table V.Cases associated with the e1a2

variant. |

Table V.

Cases associated with the e1a2

variant.

| Type | Country | Age | Gender | Method | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up

duration | Diagnosis

stage | Mutations | Adjustment |

Transplantation | Adverse

reactions | Cause of death | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CML Ph(+) | USA | 23 | F | G-banding, FISH,

PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; dasatinib, 50 mg/day. Non-TKI: Chemotherapy, ASCT | MMR | 12 months | Blast crisis | None | No adjustment | Yes, Allo-ASCT | Fatigue,

nausea | None | (97) |

| CML Ph(−) | Serbia | 32 | M | FISH, RT-PCR,

Southern blotting | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day | CHR, MMR | 18 months | Blast crisis | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild nausea,

fatigue | None | (81) |

| CML Ph(+) | Japan | 77 | M | RT-PCR | Non-TKI:

Hydroxyurea | Death | 6 months | Blast crisis | None | No treatment | No

transplantation | Severe fatigue, GI

disturbances | DIC and respiratory

failure | (91) |

| CML Ph(+) | UK | 53 | M | Sanger sequencing,

cytogenetic analysis | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; nilotinib, 300 mg/day Non-TKI: FLAG-Ida, ASCT | MMR | 18 months | Blast crisis | None | No adjustment | Allo-ASCT | Mild fatigue | None | (92) |

| CML Ph(+) | Ireland | 61 | F | RT-PCR, | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | CHR, CCyR | 24 months | Blast crisis | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (95) |

| CML Ph(+) | Spain | 79 | F | Cytogenetic

analysis, FISH, RT-PCR, Southern blotting | TKI: Imatinib 400

mg/day | Death | 12 months | Blast crisis | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Severe fatigue, GI

disturbances | Death | (96) |

e6a2 variant

Structural characteristics

e6a2 variant results from fusion between e6

of the BCR gene and e2 of the ABL1 gene. This

rearrangement alters the fusion protein structure, conferring

distinct TK activity and protein interaction profiles compared with

common variants, thereby dysregulating multiple intracellular

signaling pathways to drive leukemogenesis (98). This transcript accounts for

0.02–2.30% of all BCR-ABL1-positive CML cases. Although most

patients present in chronic phase, up to 40% of cases are diagnosed

in accelerated phase or blast crisis, with this variant frequently

demonstrating an aggressive clinical course (9,65).

This transcript was also detected in a case of ABL (99). Notably, conventional RT-qPCR may

fail to detect the e6a2 BCR-ABL1 transcript, necessitating

specialized RT-PCR strategies for rare fusion detection (66). Zagaria et al (100) employed ddPCR for e6a2

transcript quantification, leveraging its high sensitivity,

absolute quantification without standard curves and multiplexing

capabilities. Concurrent additional sex combs-like 1(ASXL1)

mutations, identified via NGS in e6a2-positive cases, may

synergize with the fusion to promote acute transformation (65). Domains retained or missing in each

subtype fusion protein are presented in Table VI.

| Table VI.Comparison of BCR-ABL1 fusion

protein domains. |

Table VI.

Comparison of BCR-ABL1 fusion

protein domains.

| Fusion protein | Retained

domains | Missing

domains | Biological

implications |

|---|

| e6a2 | BCR coiled-coil,

DBL/PH, TK | SH3 | Loss of SH3 domain

may contribute to dysregulated signaling, associated with

resistance to TKI therapy |

| e13a3 | BCR coiled-coil,

DBL/PH, TK | SH3 | Loss of SH3

enhances kinase activity, promoting unregulated cell proliferation

and leukemia development |

| e14a3 | BCR coiled-coil,

DBL/PH, TK | SH3 | Alterations in SH3

may affect cellular signaling, potentially influencing TKI

response |

| e1a3 | BCR coiled-coil,

TK | DBL/PH, SH3 | Missing SH3 and

DBL/PH domains disrupt signaling pathways, leading to aggressive

disease progression. |

Therapeutic strategies

TKIs including imatinib (101), nilotinib (63) and dasatinib (102) are used for e6a2 variant

management, with imatinib remaining the cornerstone. However,

certain scholars advocate upfront use of second-generation TKIs or

ASCT to circumvent suboptimal responses to imatinib (103). In one CML case (102), initial hydroxyurea therapy for

thrombocytosis was discontinued due to neutropenia, followed by

successful imatinib 400 mg/day administration. In vitro

sensitivity assay measuring Crk-like protein and phosphorylated-Src

family kinase (Tyr416) inhibition confirmed imatinib

responsiveness, guiding therapeutic decisions (103).

Combination regimens integrating chemotherapy and

TKIs are employed in refractory cases. Crampe et al

(65) reported a patient achieving

hematological and morphological remission (BCR-ABL1/ABL1:

0.06%) with imatinib dose escalation (from 400 to 600 mg/day),

though subsequent sepsis necessitated allogeneic ASCT. Furthermore,

targeted therapies may confer prognostic benefits in patients

harboring co-occurring ASXL1 mutations.

Prognostic outcomes

Prognoses for e6a2 variant CML exhibit

marked variability, with frequent fatal outcomes. While some

achieve sustained remission post-TKI monotherapy (63,102)

or ASCT (65), others experience

rapid progression. Prognostic indices indicate that despite a

subset of patients exhibiting low-risk Sokal scores (63), OS rates remain inferior to those

observed in patients with common transcript subtypes. A patient

with Ph-positive CML maintained CCyR for 6 months on dasatinib

despite notable eosinophilic hyperplasia with atypical precursors

(a morphology potentially linked to the e6a2 transcript)

(100). Conversely, Beel et

al (66) documented rapid blast

crisis within 3 months of TKI initiation, culminating in fatal

multidrug-resistant bacteremia post-ASCT. Rohon et al

(103) advocated early ASCT or

clinical trial enrollment for e6a2-positive cases following

short-term TKI or dual Src/ABL inhibitor therapy.

Aggressive presentations include iliac sarcoma at

diagnosis (104) and novel

BCR-ABL1 kinase domain mutations (K245E, L284S)

emerging during imatinib therapy, culminating in blast crisis CML

and death (105). These findings

underscore the need for personalized strategies addressing

variant-specific biology. Key e6a2 variant case reports and

outcomes are summarized in Table

VII.

| Table VII.Cases associated with the e6a2

variant. |

Table VII.

Cases associated with the e6a2

variant.

| Type | Country | Age, years | Gender | Method | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up

duration | Diagnosis

stage | Mutations | Adjustment |

Transplantation | Adverse

reactions | Cause of death | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CML Ph(+) | Italy | 49 | M | Cytogenetic

testing, FISH, RT-PCR, ddPCR | TKI: Dasatinib, 100

mg/day | CCR | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (100) |

| CML Ph(+) | Ireland | 48 | F | Sanger sequencing,

RT-qPCR, NGS | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Induction therapy, allo-ASCT | CHR, MMR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | Dose reduction | Allo-ASCT | Mild nausea,

fatigue | None | (65) |

| CML Ph(+) | Belgium | 57 | M | TaqMan RQ-PCR,

FISH, RT-qPCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Leukapheresis and chemotherapy, Allo-ASCT | Death | 6 months | Accelerated

phase | None | No adjustment | Allo-ASCT | Severe nausea, GI

distress | Sepsis | (66) |

| CML Ph(+) | Czech Republic | 51 | M | RT-PCR,

sequencing | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea, G-CSF, allo-ASCT | MMR | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | Allo-ASCT | Mild fatigue | None | (103) |

| CML Ph(+) | Italy | 43 | M | FISH, RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | CCyR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild nausea | None | (102) |

| CML Ph(+) | Italy | 46 | F | RT-PCR, Sanger

sequencing | TKI: Nilotinib 300

mg/day | CHR, CCyR | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild nausea,

fatigue | None | (63) |

| CML Ph(+) | Portugal | 18 | F | RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Radiotherapy, chemotherapy | Death | 3 months | Acute lymphoblastic

leukemia | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Severe nausea,

fatigue | Leukemic

transformation | (104) |

| CML Ph(+) | Germany | 48 | M | FISH, multiple

RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; dasatinib 50 mg/day | Death | 8 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Severe fatigue, GI

distress | Sepsis | (140) |

e8a2 variant

Structural characteristics

The e8a2 variant is rare in CML cases. It is

characterized by fusion between e8 of the BCR gene and exon

a2 of ABL1, with insertion of a 127-bp sequence from e8 of

Ral GEF with PH domain and SH3 binding motif 1 (106). Studies demonstrate that the

generation of this transcript requires at least three chromosomal

breaks (106,107): The first occurs within ABL1

intron 1b, causing inversion and insertion of this region

downstream of BCR e8; the second occurs at BCR intron

8, facilitating fusion of BCR e8 with ABL1 a2; the

third may involve additional chromosomes, forming a four-way

translocation (107). While the

BCR-ABL1 e8a2 transcript is predominantly observed in CML,

its occurrence in ALL remains rare (106,108). A Uruguayan study (109) documented a rare four-way

translocation t(1;17;9;22)(p35;q24;q44;q11) in a 51-year-old

female patient with e8a2-positive CML, highlighting the

complexity of chromosomal rearrangements in leukemogenesis.

Researchers (110) have identified

somatic mutations in tumor protein p53 binding protein 2 and

cadherin-10 via whole-exome sequencing, absent in typical CML or

healthy controls, suggesting potential BCR-ABL1-driven

mutagenesis. Burmeister et al (107) proposed a mechanistic model for

cryptic exon activation, generating transcripts containing 55-bp

ABL1 intron 1b sequences. While the 55-bp insertion has been

suggested as a potential prerequisite for sustaining kinase

activity (111), documented cases

demonstrate that insertion-free e8a2 retains

oncoprotein-coding capacity, suggesting molecular heterogeneity

(112,113). The e8a2 and e19a2

variants are rare and associated with complex chromosomal

rearrangements. These variants can be considered distinct from

typical BCR-ABL transcripts. due to their distinct

structural features, including the involvement of additional

chromosomal breaks that contribute to unique functional properties

of the fusion proteins. These isoforms are less commonly associated

with early TKI resistance but are often found in patients with

advanced disease or when conventional diagnostic techniques

fail.

Therapeutic strategies

TKI regimens (imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib)

constitute the primary therapeutic approach for

e8a2-positive CML, often supplemented by individualized

protocols. Dasatinib is prioritized as frontline therapy (110), with adjunctive measures such as

thromboprophylaxis and allopurinol administration tailored to

patient-specific factors, including age, comorbidity and disease

phase. Close clinical monitoring ensures timely regimen

optimization.

Prognostic outcomes

Most patients with e8a2 variant CML show a tendency

towards favorable outcomes under TKI therapy (114); while initial studies associated

the e8a2 transcript with thrombocytosis and suggested a poorer

prognosis, more recent findings indicate that prognosis may vary,

and the evidence remains inconclusive (107,115). Imatinib-treated cases typically

demonstrate robust responses, while interferon-intolerant patients

achieve CHR and CMR (BCR-ABL1 <0.001%) within 6 weeks, sustained

beyond 6 months (110). Tchirkov

et al (116) validated

real-time RT-PCR for precise molecular monitoring, enabling

therapeutic efficacy assessment and relapse prediction. Key e8a2

variant case reports and outcomes are summarized in Table VIII.

| Table VIII.Cases associated with the e8a2

variant. |

Table VIII.

Cases associated with the e8a2

variant.

| Type | Country | Age | Gender | Method | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up

duration | Diagnosis

stage | Mutations | Adjustment |

Transplantation | Adverse

reactions | Cause of death | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CML Ph(+) | Uruguay | 51 | F | GTG-banding, FISH,

RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | CCyR, MMR, CHR | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue,

nausea | None | (109) |

| CML Ph(+) | Korea | 46 | M | FISH, RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day | CHR | 10 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild nausea | None | (141) |

| CML Ph(+) | France | 43 | M | RT-PCR, cytogenetic

testing, FISH | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day | MMR, CCyR | 15 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue, GI

upset | None | (116) |

| CML Ph(+) | China | 49 | M | FISH, RT-PCR,

Sanger sequencing, RQ-PCR | TKI: Dasatinib, 50

mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea, interferon | MMR, CHR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild nausea | None | (110) |

| CML Ph(+) | Germany | 74 | M | RT-PCR, multiple

PCR, RT-qPCR | TKI: Nilotinib, 300

mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | BCR-ABL1 levels are

significantly decreased | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (108) |

e19a2 variant

Structural characteristics

The e19a2 (µ-BCR-ABL1) transcript arises from

aberrant fusion of BCR intron 19 to ABL1 exon a2, encoding a

230-kDa fusion protein (117). Its

formation involves submicroscopic insertion events, resulting in

FISH-negative/RT-PCR-positive detection. While p230 retains BCR

oligomerization domains and ABL1 TK activity, structural divergence

from p210 may compromise kinase-dependent signaling efficiency.

Sequencing of cDNA microproducts (118) has identified mutations in ABL1

e4-9, while WGS uncovered a 122-kb ABL1 insertion into the BCR

locus (117).

Therapeutic strategies

Management of e19a2-positive leukemia

involves sequential or combinatorial TKI regimens. Patients

frequently achieve MMR through sequential use of nilotinib,

dasatinib or ponatinib. Imatinib, though initially employed, is

often substituted due to resistance, thrombocytopenia, fluid

retention or drug interactions (119,120). Dose escalation may partially

restore hematological/cytogenetic responses in resistant cases. For

imatinib-resistant patients harboring the E355G mutation,

second-generation TKIs such as nilotinib induce major cytogenetic

responses, offering alternative therapeutic avenues (121). Allogeneic ASCT is utilized in

select cases (122), primarily

because it remains the only potentially curative treatment for CML.

It becomes a critical salvage treatment option when patients

develop resistance to or intolerable severe side effects from

multiple TKIs, or when the disease progresses from the chronic

phase to the prognostically unfavorable accelerated or blast

phase.

Prognostic outcomes

The prognosis of patients with e19a2 variant

CML is influenced by genetic architecture, therapeutic regimen and

individual comorbidities. Evidence indicates a trend towards

favorable outcomes, but individual responses differ (119,122). While studies have linked the

e19a2 transcript to an indolent phenotype (115,123), accumulating cases demonstrate

clinical courses indistinguishable from classic CML (117), with potential heightened

aggressiveness (124).

Second-generation TKIs such as nilotinib and dasatinib demonstrate

robust efficacy, exemplified by a 72-year-old patient with

chronic-phase CML who achieved CCyR at 6 months and MMR at 12

months with dasatinib combined with hydroxyurea and interferon

adjuncts, underscoring its utility as frontline therapy (120). Disease progression may occur in

certain cases, manifesting as leukocytosis or marrow dysplasia.

Notably, a patient managed with nilotinib required dose

interruptions due to grade 2 hepatotoxicity yet maintained

sustained CCyR and deep MR during long-term follow-up, aligning

with findings by Crampe et al (121) and Ernst et al (122), which confirmed nilotinib durable

efficacy following treatment interruptions (125). Hydroxyurea monotherapy has also

stabilized leukocyte counts without complications in select cases

(126–128).

Resistance mechanisms pose challenges. An Italian

study (118) reported a

dasatinib-resistant T315I mutation, typically associated with TKI

refractoriness, where dose escalation partially restored

hematological and cytogenetic responses, suggesting salvage

potential in mutation-positive patients. Clonal evolution,

including double Ph chromosomes and tetraploidy detected via FISH

and cytogenetics in an imatinib-treated patient (129), culminated in fatal blast crisis

within 2 years, emphasizing the need for personalized strategies in

e19a2 BCR-ABL1-positive CML. e19a2 variant case

reports and outcomes are summarized in Table IX.

| Table IX.Cases associated with the

e19a2 variant. |

Table IX.

Cases associated with the

e19a2 variant.

| Type | Country | Age, years | Gender | Method | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up

duration | Diagnosis

stage | Mutations | Adjustment |

Transplantation | Adverse

reactions | Cause of death | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CML Ph(+) | Italy | 78 | F | FISH, RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg; day; nilotinib, 300 mg/day; dasatinib. 50 mg/day. Non-TKI:

Interferon, cytarabine | Drug

resistance | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (118) |

| CML Ph(+) | Japan | 85 | F | FISH, RT-PCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | Death | 12 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild nausea | Death | (129) |

| CML Ph(+) | Germany | 89 | F | FISH, RT-PCR,

direct sequencing | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; dasatinib, 50 mg/day; nilotinib. 300 mg/day. Non-TKI:

Hydroxyurea | No complications

observed, but WBC count remained high | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (142) |

| CML Ph(+) | Tunisia | 34 | F | RT-PCR, FISH | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day nilotinib, 300 mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | Initial MCyR, but

TKI resistance develops later | 15 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild nausea | None | (143) |

| CML Ph(+) | Japan | 72 | F | RT-qPCR, FISH | TKI: Nilotinib 300

mg/day | CCyR, MMR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (129) |

| CML Ph(+) | Ireland | 26 | M | RT-PCR, Direct

sequencing | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day Non-TKI: Interferon, hydroxyurea therapy | e19a2 BCR-ABL1

remains | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (144) |

| CML Ph(+) | Japan | 77 | F | RT-qPCR, | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; nilotinib, 300 mg/day | MMR | 20 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (125) |

| CML Ph(+) | Ireland | 53 | F | Bone marrow

morphology, cytogenetics, molecular analysis | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; nilotinib, 300 mg/day Non-TKI: G-CSF | MMR | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (121) |

| CML Ph(+) | Germany | 33 | M | Multiple PCR,

Sanger sequencing | TKI: Ponatin, 45

mg/day; baxitinib, 5 mg/day. Non-TKI: Interferon | MMR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild nausea | None | (122) |

| CML Ph(+) | France | 72 | F | FISH, PCR,

sequencing | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day; dasatinib 50 mg/day | MMR | 24 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (119) |

| CML Ph(-) | UK | 43 | F | G-banded chromosome

analysis, RT-qPCR | TKI: Imatinib, 400

mg/day dasatinib 50 mg/day. Non-TKI: Hydroxyurea | MMR | 18 months | Chronic phase | None | No adjustment | No

transplantation | Mild fatigue | None | (145) |

e12a2 variant

The e12a2 variant, a rare subtype, arises

from fusion between e12 of the BCR gene and exon a2 of

ABL1. Investigators employed primer sets (BCR-10 and ABL1-4)

in RT-PCR assays to detect uncommon e12a2 BCR-ABL1 fusion

transcripts, identifying an 18-bp insertion derived from

ABL1 intron 1b at the junctional site (130). Notably, this isoform may co-occur

with common transcripts, suggesting clonal heterogeneity or

molecular evolution during disease progression (130).

Therapeutic approaches involve sequential TKIs

(imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib, ponatinib) (130). A 59-year-old male patient with CML

who developed resistance to imatinib (130) achieved CCyR and MR3 within 6

months of nilotinib escalation (800 mg/day). Due to cardiovascular

adverse events, therapy was subsequently transitioned to ponatinib

(15 mg/day), maintaining a MR4 for 6 years. However, management

complexity arises from frequent requirement for multiple drugs,

dose-limiting toxicity and treatment-associated burdens,

necessitating rigorous monitoring. The paucity of reported e12a2

BCR-ABL1 cases underscores the need for expanded cohort studies

to elucidate its impact on disease progression and prognosis.

e18a2 variant

The e18a2 transcript is a rare

BCR-ABL1 fusion variant arising from t(9;22)(q34;q11)

chromosomal translocation, which juxtaposes e18 of the BCR

gene with exon 2 (a2) of ABL1, encoding a 225 kDa

fusion protein (p225) (131,132). The breakpoint within the µ-BCR

region retains nearly complete BCR sequences, including

calcium-binding and GTPase-Activating Protein domains specific for

the Rac GTPase and coiled-coil oligomerization motifs, while

preserving the intact TK domain of ABL1 (133). The e18a2 transcript is rare

in CML, with an estimated incidence <1%. A recent study

documented a 49-year-old patient with CML initially misclassified

as e19a2-positive; relapse evaluation failed due to negative

conventional RT-qPCR targeting common isoforms, highlighting

diagnostic challenges (134).

Coexistence of e18a2 with e19a2 transcripts further

complicates detection (135).

Current therapeutic evidence for e18a2

remains sparse (4,134), though insights may be extrapolated

from other rare variants. In a 16-year-old female patient with CML

harboring e18a2 (136),

initial RQ-PCR failed to detect the transcript, yielding

false-negative results. Treatment commenced with hydroxyurea and

imatinib 600 mg/day, later decreased to 400 mg/day due to

thrombocytopenia. CHR was achieved by day 56, followed by major

cytogenetic response by day 106. Customized RQ-PCR monitoring

revealed a decline in tumor burden to 1×10−3 by month

15. Imatinib was safely re-escalated to 600 mg/day without relapse,

demonstrating favorable tolerability. The prognostic value of

e18a2 remains contentious due to limited sample sizes and

undefined molecular kinetics.

e13a1 variant

The e13a1 transcript is characterized by the

replacement of the terminal 38 bp of BCR e13 with a 37-bp

sequence derived from ABL1 intron 1–2/e1, resulting in

bidirectional disruption of exon junction architecture. Notably, a

G>A point mutation within the inserted sequence substitutes

glutamine with lysine at position 27 (137), potentially altering local charge

distribution and impacting drug-binding efficiency, though direct

experimental evidence remains lacking. A previous study documented

a 69-year-old patient with CML initially yielding negative results

with TaqMan RT-q and multiplex PCR assays; subsequent Sanger

sequencing of single-step PCR products confirmed the e13a1

transcript. The patient achieved sustained MR (BCR-ABL1/ABL1

levels ranging from MR4.5 to MMR) following imatinib therapy,

underscoring therapeutic efficacy while necessitating long-term

surveillance.

Other variants

Certain BCR-ABL1 transcripts reported in the

literature are rare (4,61), with their clinical significance

poorly defined. For example, e1a4 and e1a5 variants

have been described exclusively in Ph+ ALL (61), although large-scale epidemiological

data validating their prevalence or clinical relevance are lacking.

The e8a4 variant was detected in a patient with Sézary

syndrome (138); to the best of

our knowledge, however, there have been no subsequent studies

investigating this variant, and its direct association with

BCR-ABL1-driven oncogenesis requires further exploration.

The existence of these rare transcripts suggests certain variants

may emerge selectively within specific disease subtypes or

individuals. Nevertheless, due to limitations in detection

technologies and the paucity of reported cases, numerous potential

variants may remain undetected or systematically

uncharacterized.

Discussion

The growing recognition of atypical BCR-ABL1

fusion transcripts in CML underscores the need for nuanced

diagnostic and therapeutic strategies (4,26).

While canonical isoforms dominate clinical practice, atypical

variants such as e13a3, e14a3, e1a3, e1a2, e6a2 and

e8a2 exhibit distinct molecular architectures that notably

influence disease biology, therapeutic responsiveness and clinical

outcomes (139).

Advances in understanding atypical fusions have

revealed distinct structural configurations that alter fusion

protein function, dysregulating intracellular signaling,

proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. Therapeutic

strategies combining TKIs, chemotherapy and ASCT demonstrate

variable efficacy across subtypes. While certain patients achieve

durable remission, others experience refractory disease or rapid

progression, highlighting pronounced inter-variant prognostic

heterogeneity. For example, e13a3 and e8a2 variants

are frequently associated with indolent disease course and

favorable responses to TKIs, as evidenced by sustained cytogenetic

and molecular remissions in multiple case series (7,44,110,116). Conversely, patients with

e1a2 and e6a2 isoforms experience more rapid disease

progression, including accelerated phase or blast crisis. In

refractory cases, 5-year OS rates are 40–70%. Notably, patients

with e1a2-positive CML often present with lymphoid blast

crisis-like features, including monocytosis and absence of

basophilia, mirroring Ph-positive ALL. Similarly, e6a2 cases

show elevated rates of clonal evolution and resistance mutations,

necessitating early escalation to second-generation TKIs or ASCT.

These findings emphasize that atypical transcripts are not

uniformly benign and require vigilant monitoring. TKI

responsiveness varies significantly across atypical variants. While

imatinib remains effective for e13a3 and e8a2, e1a2

and e6a2 subtypes often require early transition to second-

or third-generation TKIs due to intrinsic resistance. Dose

adjustments or combination regimens may salvage responses in

resistant cases, as demonstrated in patients with e6a2

achieving molecular remission post-ASCT. However, therapeutic

decisions must balance efficacy against toxicity, particularly in

elderly or comorbid populations. For example, dose reduction

mitigates hepatotoxicity while maintaining remission in

e14a3 cases.

Conventional diagnostic methods, such as standard

RT-PCR or FISH, may fail to detect rare fusion isoforms due to

primer mismatches or cryptic chromosomal rearrangements. For

example, e1a3 and e6a2 transcripts are frequently

missed by routine assays, leading to delayed diagnosis and

inappropriate therapeutic choices. Complementary techniques,

including multiplex RT-PCR, nested PCR and RNA-seq, are essential

for identifying atypical breakpoints and coexisting mutations that

may drive disease progression. ddPCR further enhances sensitivity

for minimal residual disease monitoring, particularly for

low-abundance transcripts such as e6a2.

Data on atypical transcripts derive predominantly

from case reports and small cohorts, limiting statistical power and

generalizability. To address these challenges, multicenter

collaborative studies are required to expand case accrual and

establish robust genomic databases. Mechanistic investigations

should delineate molecular pathways and crosstalk between atypical

fusions and ancillary signaling networks, informing precision

therapeutics. Diagnostic innovation should prioritize

high-sensitivity/specificity assays for rare fusion detection,

enabling early intervention. Therapeutic development requires

variant-tailored approaches integrating genomic profiling, disease

stage and patient comorbidities, alongside intensified research

into resistance mechanisms and salvage strategies. Longitudinal

studies assessing long-term outcomes and survivorship are key to

optimize holistic care, refine prognostic stratification and

ultimately improve survival for patients with atypical

BCR-ABL1-positive leukemia.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Taishan Youth Scholar

Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no. tsqn201812140).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

XZ wrote the manuscript and constructed figures and

tables. AL, DK and PZ revised the manuscript. YS and NS designed

the methodology. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Foroni L, Wilson G, Gerrard G, Mason J,

Grimwade D, White HE, de Castro DG, Austin S, Awan A, Burt E, et

al: Guidelines for the measurement of BCR-ABL1 transcripts in

chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 153:179–1790. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Stella S, Gottardi EM, Favout V, Barragan

Gonzalez E, Errichiello S, Vitale SR, Fava C, Luciano L, Stagno F,

Grimaldi F, et al: The Q-LAMP method represents a valid and rapid

alternative for the detection of the BCR-ABL1 rearrangement in

Philadelphia-positive leukemias. Int J Mol Sci. 20:61062019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jajosky AN and Lichtman MA: Uncommon

phenotypes of BCR::ABL1-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia.

Haematologica. 110:1912–1920. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Breccia M: Atypical CML: Diagnosis and

treatment. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2023:476–482.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yan Z, Shi L, Li W, Liu W, Galderisi C,

Spittle C, Spittle C and Li J: A novel Next-generation sequencing

assay for the identification of BCR::ABL1 Transcript type and

accurate and sensitive detection of TKI-resistant mutations. J Appl

Lab Med. 9:886–900. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cross NCP, Ernst T, Branford S, Cayuela

JM, Deininger M, Fabarius A, Kim DDH, Machova Polakova K, Radich

JP, Hehlmann R, et al: European LeukemiaNet laboratory

recommendations for the diagnosis and management of chronic myeloid

leukemia. Leukemia. 37:2150–2167. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Leske IB and Hantschel O: The e13a3 (b2a3)

and e14a3 (b3a3) BCR::ABL1 isoforms are resistant to asciminib.

Leukemia. 38:2041–2045. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen Z: The e1a3 BCR-ABL1 fusion

transcript in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic

leukaemia: A case report. Hematology. 28:21860402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Baccarani M, Castagnetti F, Gugliotta G,

Rosti G, Soverini S, Albeer A and Pfirrmann M; International

BCR-ABL Study Group, : The proportion of different BCR-ABL1

transcript types in chronic myeloid leukemia. An international

overview. Leukemia. 33:1173–1183. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ding L, Chen Q, Chen K, Jiang Y, Li G,

Chen Q, Bai D, Gao D, Deng M, Zhang H and Xu B: Simvastatin

potentiates the cell-killing activity of imatinib in

imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia cells mainly through

PI3K/AKT pathway attenuation and Myc downregulation. Eur J

Pharmacol. 913:1746332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li Y, Zhang Y, Meng X, Chen S, Wang T,

Zhang L and Ma X: Chronic myeloid leukemia with two rare fusion

gene transcripts of atypical BCR::ABL: A case report and literature

review. Medicine (Baltimore). 103:e367282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Schäfer V, White HE, Gerrard G, Möbius S,

Saussele S, Franke GN, Mahon FX, Talmaci R, Colomer D, Soverini S,

et al: Assessment of individual molecular response in chronic

myeloid leukemia patients with atypical BCR-ABL1 fusion

transcripts: Recommendations by the EUTOS cooperative network. J

Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 147:3081–3089. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hoffmann VS, Baccarani M, Hasford J,

Castagnetti F, Di Raimondo F, Casado LF, Turkina A, Zackova D,

Ossenkoppele G, Zaritskey A, et al: Treatment and outcome of 2904

CML patients from the EUTOS population-based registry. Leukemia.

31:593–60. 20171 View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hughes T, Deininger M, Hochhaus A,

Branford S, Radich J, Kaeda J, Baccarani M, Cortes J, Cross NC,

Druker BJ, et al: Monitoring CML patients responding to treatment

with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Review and recommendations for

harmonizing current methodology for detecting BCR-ABL transcripts

and kinase domain mutations and for expressing results. Blood.

108:28–37. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lin X, Huang H and Chen P: Retrospective

analysis of the clinical features of 172 patients with

BCR-ABL1-negative chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. Mol

Cytogenet. 13:82020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tang Z, Wang W, Toruner GA, Hu S, Fang H,

Xu J, You MJ, Medeiros LJ, Khoury JD and Tang G: Optical genome

mapping for detection of BCR::ABL1-another tool in our toolbox.

Genes (Basel). 15:13572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu B, Zhang W and Ma H: Complete

cytogenetic response to Nilotinib in a chronic myeloid leukemia

case with a rare e13a3(b2a3) BCR-ABL fusion transcript: A case

report. Mol Med Rep. 13:2635–2638. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Avila M and Meric-Bernstam F:

Next-generation sequencing for the general cancer patient. Clin Adv

Hematol Oncol. 17:447–454. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sorokin M, Rabushko E, Rozenberg JM,

Mohammad T, Seryakov A, Sekacheva M and Buzdin A: Clinically

relevant fusion oncogenes: Detection and practical implications.

Ther Adv Med Oncol. 14:175883592211441082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lee H, Seo J, Shin S, Lee ST and Choi JR:

Development and validation of sensitive BCR::ABL1 fusion gene

quantitation using next-generation sequencing. Cancer Cell Int.

23:1062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang X, Sun H, Su Y and Yi H: Long-term

molecular remission after treatment with imatinib in a chronic

myeloid leukemia patient with extreme thrombocytosis harboring rare

e14a3 (b3a3) BCR::ABL1 transcript: A case report. Curr Oncol.

29:8171–8179. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Blachly JS, Walter RB and Hourigan CS: The

present and future of measurable residual disease testing in acute

myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 107:2810–2822. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Denk D, Bradtke J, König M and Strehl S:

PAX5 fusion genes in t(7;9)(q11.2;p13) leukemia: A case report and

review of the literature. Mol Cytogenet. 7:132014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kosik P, Skorvaga M and Belyaev I:

Incidence of preleukemic fusion genes in healthy subjects.

Neoplasma. 63:659–672. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Elgehama A, Chen W, Pang J, Mi S, Li J,

Guo W, Wang X, Gao J, Yu B, Shen Y and Xu Q: Blockade of the

interaction between Bcr-Abl and PTB1B by small molecule SBF-1 to

overcome Imatinib-resistance of chronic myeloid leukemia cells.

Cancer Lett. 372:82–88. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Szuber N, Orazi A and Tefferi A: Chronic

neutrophilic leukemia and atypical chronic myeloid leukemia: 2024

update on diagnosis, genetics, risk stratification, and management.

Am J Hematol. 99:1360–1387. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ha J, Cheong JW, Shin S, Lee ST and Choi

JR: Chronic myeloid leukemia with rare variant b2a3 (e13a3)