Introduction

Esophageal cancer is one of the most common solid

tumors and the seventh leading cause of cancer-related death

worldwide (1). Despite advancements

in treatment approaches, the prognosis for patients with advanced

esophageal cancer remains poor (2).

The most common histologic subtypes of esophageal cancer are

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal

adenocarcinoma. In Asia, ESCC accounts for a particularly high

proportion of cases.

Regarding ESCC, differentiation grades are

classified into three categories: Well-differentiated, moderately

differentiated, and poorly differentiated, according to the Union

for International Cancer Control (UICC) Staging Manual, 8th

edition. Well-differentiated tumors are characterized by prominent

keratinization, including pearl formation, along with a minor

component of non-keratinizing basal-like cells. Moderately

differentiated tumors exhibit a range of histological features,

from parakeratotic changes to poorly keratinizing lesions. Poorly

differentiated tumors mainly consist of basal-like cells forming

both large and small nests, often accompanied by central necrosis.

Furthermore, these nests can form sheets or pavement-like

arrangements of tumor cells and may occasionally include small

numbers of parakeratotic or keratinizing cells (3). Poorly differentiated ESCC typically

has a greater propensity for early lymphatic metastasis and skip

metastasis to distant lymph node stations, leading to a poorer

prognosis (4,5).

Meanwhile, microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) have gained

attention for their oncogenic or tumor-suppressive functions. These

endogenous, small, non-coding, single-stranded RNAs, measuring

20–25 nucleotides, regulate target gene expression at the

post-transcriptional level by binding to complementary sequences

(6,7). Therefore, it was hypothesized that

specific miRNAs and their target mRNAs play crucial roles in

ESCC.

In the present study, it was aimed to identify

miRNAs associated with tumor characteristics in ESCC by comparing

miRNA expression between poorly differentiated (por) and well- to

moderately differentiated (non-por) ESCC using a comprehensive

miRNA array-based approach with clinical tissue samples and GEO

datasets from the National Library of Medicine. It was also aimed

to identify mRNA targeted by specific miRNAs to better understand

the mechanisms of tumor progression and potential therapeutic

targets in ESCC.

Materials and methods

Microarray and bioinformatics

To identify potential biomarkers, microarray

analyses of ESCC tissue samples were first performed using 3D-Gene

miRNA oligo chips (Toray Industries, Inc.), each containing 2,565

genes. miRNA expression in tumor tissues was collected from

patients with ESCC who underwent curative resection at our

institution, comparing miRNA expression between non-por and por

ESCC within the same specimens. RNAs were labeled using the 3D-Gene

miRNA labeling kit (Toray Industries, Inc.). Fluorescent signals

were scanned with a 3D-Gene scanner 3000 (Toray Industries, Inc.)

and analyzed using the 3D-Gene Extraction software (Toray

Industries, Inc.). Next, our analysis was supplemented with a GEO

dataset (GSE43732) (8), a publicly

accessible repository that includes miRNA expression profiles from

primary lesions of 119 patients with ESCC. miRNA expression was

compared between patients with por and non-por ESCC and

additionally performed overall survival (OS) analysis according to

tumor differentiation status.

Patients and samples

The study population comprised a retrospective

cohort of patients with consecutive ESCC who underwent

esophagectomy at the Department of Digestive Surgery, University of

Yamanashi (Chuo, Japan) between February 2008 and January 2023. To

eliminate any confounding effects of chemotherapy or radiotherapy,

169 patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=144) or

neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (n=25) were excluded. An additional

11 cases were excluded due to non-curative resection. Furthermore,

30 cases unsuitable for RNA extraction were removed because the

tissue samples were too shallow for adequate RNA retrieval. As a

result, a final cohort of 61 patients with ESCC were eligible for

the present study (Fig. S1).

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients (including sex and

age distribution) are listed in Table

I.

| Table I.Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients. |

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients.

|

| Expression level of

miR-100-5p | Expression level of

miR-203a-3p |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | Low (n=13) | High (n=48) | P-value | Low (n=36) | High (n=25) | P-value |

|---|

| Age

(years)a | 72 (43–83) | 78 (60–83) | 0.12 | 74 (43–83) | 74 (57–83) | 0.65 |

| Sexb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 12 (92.3) | 36 (75.0) | 0.26 | 29 (80.5) | 19 (76.0) | 0.75 |

|

Female | 1 (7.7) | 12 (25.0) |

| 7 (19.5) | 6 (24.0) |

|

| Tumor

differentiationb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Well | 0 (0) | 18 (37.5) | <0.001 | 14 (38.9) | 4 (16.0) | 0.01 |

|

Moderately | 2 (15.4) | 21 (43.8) |

| 8 (22.2) | 15 (60.0) |

|

|

Poorly | 11 (84.6) | 9 (18.7) |

| 14 (38.9) | 6 (24.0) |

|

| Pathological T

stageb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T1 | 0 (0) | 17 (35.4) | 0.012 | 5 (13.9) | 12 (48.0) | 0.008 |

| T2, T3,

T4 | 13 (100) | 31 (64.6) |

| 31 (86.1) | 13 (52.0) |

|

| Pathological N

stageb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N0 | 3 (23.1) | 23 (48.0) | 0.13 | 11 (30.6) | 15 (60.0) | 0.03 |

| N1, N2,

N3 | 10 (76.9) | 25 (52.0) |

| 25 (69.4) | 10 (40.0) |

|

| Lymphatic

invasionb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ly0 | 4 (30.8) | 23 (47.9) | 0.35 | 13 (36.1) | 14 (56.0) | 0.19 |

| ly1,

ly2, ly3 | 9 (69.2) | 25 (52.1) |

| 23 (63.9) | 11 (44.0) |

|

| Vascular

invasionb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| v0 | 3 (23.1) | 14 (29.2) | 1.00 | 8 (22.2) | 9 (36.0) | 0.26 |

| v1, ν2,

ν3 | 10 (76.9) | 34 (70.8) |

| 28 (77.8) | 16 (64.0) |

|

Tumor specimens and resected lymph nodes obtained at

the time of surgery were immediately fixed in 10% neutral-buffered

formalin at room temperature for 24 h and embedded in paraffin

after fixation (FFPE). The clinical and pathological tumor stages

of esophageal cancer were classified according to the UICC TNM

staging, 8th Edition (3).

Patients were followed up with physical

examinations, blood tests, and computed tomography every 4 months

for at least 1 year, and every 6 months thereafter. The present

study was approved (approval no. 2723) by the Ethics Committee of

Yamanashi University (Chuo, Japan) and conducted in accordance with

the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its

amendments.

Histopathological evaluation and

immunohistochemical (IHC) staining analyses

Serial sections were obtained from FFPE tissue

blocks for IHC staining and RNA extraction. FFPE sections (5 µm)

were used for IHC. After deparaffinization with xylene, dehydration

using a graded ethanol series, and antigen retrieval at 120°C for

15 min endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited

(Peroxidase-Blocking Solution; cat. no. S2023; Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.), and non-specific binding was blocked (Protein

Block Serum-Free; cat. no. X0909; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc).

The sections were then incubated with a polyclonal FKBP5

antibody (1:50; cat. no. 14155-1; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at room

temperature for 1.5 h. Subsequently, slides were treated with an

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (EnVision+ HRP; cat. no.

K4003; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) at room temperature for 60

min. DAB working solution was used to stain positive cells. The

results were observed and recorded using optical microscopy

(BZ-X810; Keyence Corporation).

Each slide was scored according to the H-score,

which is calculated by multiplying two parameters: the proportion

of positive cells (1–100%) and the intensity of staining (1=weak;

2=moderate; 3=strong; range, 0–300).

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were obtained from the harvested

KYSE70 cells, and protein concentrations were determined using the

bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Cell lysate proteins (20 µg/lane) were separated

by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(SDS-PAGE) and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride

membranes. After blocking with StartingBlock Blocking Buffer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h, the

membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following

antibodies: E-cadherin (1:1,000; cat. no. 20874-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), Vimentin (1:2,000; cat. no. 10366-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), phosphorylated (p-)PI3K (1:1,000; cat. no. 17366;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), PI3K (1:1,000; cat. no. 11889;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), p-AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. 4060;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. 4691; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), GAPDH (1:50,000; cat. no. 60004-1-lg;

Proteintech Group, Inc.). Then, the membranes were incubated with

goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish

peroxidase (1:10,000; cat. nos. ab6721 and ab6789; Abcam) buffer

for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes then were probed with

the indicated antibodies, and proteins were detected by a western

blot HRP Substrate (Takara Bio, Inc.). Densitometric analysis of

the protein bands was performed using FIJI (ImageJ; version 1.54q,

National Institutes of Health).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

FFPE tissue samples were cut into 10-µm-thick

sections, and total RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy FFPE kit

(Qiagen GmbH) and NucleoSpin miRNA (Takara Bio, Inc.), following

the manufacturer's protocols. A NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to measure the total RNA

concentration.

Reverse transcription was performed using the

High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total RNA and miRNA levels were

quantified by RT-qPCR following standard procedures.

RT-qPCR conditions were as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for

15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec. Total RNA levels were normalized to the

endogenous control gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

(GAPDH), while miRNA levels were normalized to RNU6B.

The following primers were used for the TaqMan assay

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.): human hsa-miR-100-5p (cat. no.

78224_mir; 5′-AACCCGUAGAUCCGAACUUGUG-3′), hsa-miR-203a-3p (cat. no.

478316_mir; 5′-GUGAAAUGUUUAGGACCACUAG-3′), FKBP5 (cat. no.

Hs01561006_m1), GAPDH (cat. no. Hs02786624_g1) and RNU6B (cat. no.

001093; 5′-CGCAAGGATGACACGCAAATTCGTGAAGCGTTCCATATTTTT-3′). ΔCq

values for all RNAs were calculated relative to the control genes

GAPDH and RNU6B. Relative mRNA and miRNA expression levels were

evaluated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (9).

Cell culture

The poorly differentiated ESCC cell lines [KYSE70

(JCRB0190), KYSE110 (JCRB1064), and TE5 (RCB1949)] and the well- to

moderately differentiated ESCC cell lines [TE4 (RCB2097), TE8

(RCB2098), and TE11 (RCB2100)] were used in the present study.

KYSE70 and KYSE110 were obtained from the Japanese Collection of

Research Bioresources (JCRB) Cell Bank, while TE series cell lines

were obtained from the RIKEN BRC Cell Bank in 2024. All cell lines

were confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination, as

previously described (10–12).

KYSE70, TE4, TE8 and TE11 were cultured in Roswell

Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The other ESCC

cell lines were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium (FUJIFILM Wako Pure

Chemical Corporation) supplemented with 2% FBS and

penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA). All cells were

maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% carbon

dioxide.

Transfection of KYSE70 with miRNA

mimics

The miRNA mimics for miR-100-5p (mirVana miRNA

mimic; cat. no. MC10188; 5′-AACCCGUAGAUCCGAACUUGUG-3′), miR-203a-3p

(mirVana miRNA mimic; cat. no. MC10152;

5′-GUGAAAUGUUUAGGACCACUAG-3′, and the miRNA mimic negative control

(mirVana miRNA Mimic Negative Control #1; cat. no. 4464058) were

purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Transfections were

performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The final concentration for miR-100-5p and

miR-203a-3p mimics, as well as the negative control, was 10

nM. For double transfection, both mimics were used at 10 nM each.

Total RNA and protein were collected 48 h post-transfection.

Transfection efficiency was assessed by quantifying miRNAs

expression levels using RT-qPCR.

Transfection of KYSE70 with siRNA

The siRNA for FKBP5 (Silencer Select siRNA;

cat. no. s5215) (sense sequence: GAGAAAGGCUUGUAUAGGAtt) and the

siRNA negative control (Silencer Select Negative Control #1; cat.

no. 4390843) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. The

transfection protocol and concentration were the same as those used

for the mimics. Knockdown efficiency of FKBP5 was confirmed

by western blotting.

Migration and invasion assays

The cell migration and invasion assays for KYSE70

cells were conducted using Transwell chambers. For invasion assays,

the chambers were pre-coated with Matrigel (Corning, Inc.), while

migration assays were performed without it. Cells

(1×105) suspended in serum-free medium were placed in

the upper chamber, while 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber.

After a 24-h incubation, cells were stained using the Differential

Quik III Stain Kit (Polysciences, Inc.). Following washing and

drying, images were captured and examined under the microscope.

Functional rescue experiments

To determine whether the effects of the

double-transfection of miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p mimics on cell

migration and invasion were mediated through FKBP5

suppression, functional rescue experiments were performed by

co-transfecting the double-transfection condition with FKBP5

siRNA. KYSE70 cells were transfected with the double-transfection

of miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p mimics (10 nM each), with or without

FKBP5 siRNA (10 nM). After 48 h, migration and invasion

assays were conducted as aforementioned. The number of migrated and

invaded cells in the double-transfection + FKBP5 siRNA group

was compared with that in the double-transfection group to assess

whether additional FKBP5 knockdown further modified the

miRNA-induced phenotype.

Cytotoxicity assay

To assess cell proliferation, KYSE70 cells

(1×104/well) were passaged in 96-well plates in

RPMI-1640 culture medium containing penicillin-streptomycin,

supplemented with 10% FBS. Cell proliferation was measured by the

OD values using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; (Dojindo Laboratories,

Inc.). A total of 100 µl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well,

and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a CO2

incubator. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm on a microplate

reader (Spectra Max ABS Plus, Molecular Devices, LLC).

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis was assessed in KYSE70 cells following

FKBP5 knockdown. The siRNA transfection procedure and

concentrations were identical to those aformentioned. A total of 48

h after transfection, apoptotic activity was evaluated by both flow

cytometry and western blotting.

For flow cytometric analysis, cells were collected,

washed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in binding buffer.

Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.)

were added according to the manufacturer's instructions, and

samples were analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD FACSCelesta; BD

Biosciences) with BD FACSDiva software (v8.0.1.1; BD Biosciences).

The proportions of viable, early apoptotic, and late apoptotic

cells were quantified.

For western blotting, protein expression of

apoptosis-related markers was examined using antibodies against

Caspase-3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 14220; Cell Signalling Technology,

Inc.) and Bcl-2 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab692; Abcam).

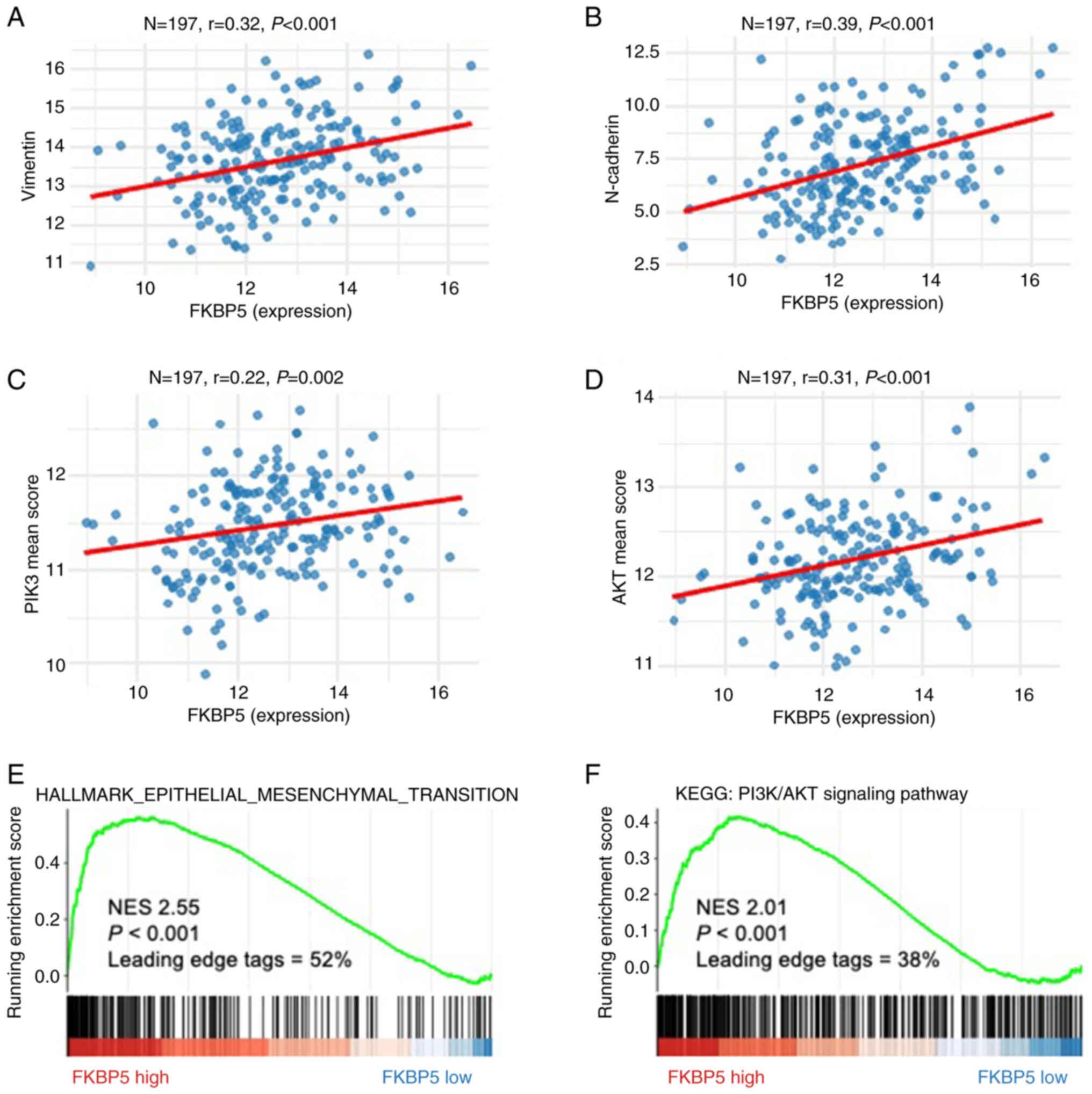

Bioinformatics analyses

RNA-seq transcriptome data of ESCC was obtained from

The Cancer Genome Atlas database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Potential miRNA

target genes were predicted using TargetScan Human 8.0 (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/). To

investigate the biological functions of FKBP5, Pearson's

correlation coefficients were first calculated between FKBP5

expression and all other genes across ESCC samples. Genes with

|Pearson r|>0.3 and P<0.001 were considered significantly

correlated with FKBP5 and subjected to enrichment analysis.

Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process and Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment were performed using

the R package clusterProfiler (version 4.8; http://bioconductor.org/packages/clusterProfiler),

with multiple-testing correction by Benjamini-Hochberg and

significance thresholds of adjusted P<0.05 and q-value

<0.05.

To assess pathway-level associations, single-sample

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was applied using the GSVA

package (version 1.42; http://bioconductor.org/packages/GSVA). Each tumor

received a score for the following two gene sets from MSigDB:

HALLMARK_EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION,

KEGG_PI3K_AKT_SIGNALING_PATHWAY (hsa04151).

Finally, pre-ranked GSEA was conducted with cluster

Profiler: GSEA by ranking all genes in descending order of

Pearson's correlation with FKBP5. Only the EMT (Hallmark)

and PI3K-Akt (KEGG) gene sets were evaluated for enrichment, using

an FDR cutoff of 0.25. All analyses were performed in R (version

4.4.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics). Unless

otherwise stated, quantitative values were expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was assessed

using the Mann-Whitney U test, Fisher's exact test, and one-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each time point, followed by

Tukey's post hoc test. OS was calculated from the date of surgery

to either death or the last follow-up. Relapse-free survival (RFS)

was measured from the date of surgery to recurrence, death, or the

last follow-up. Survival curves were generated using the

Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Identification of miRNA

candidates

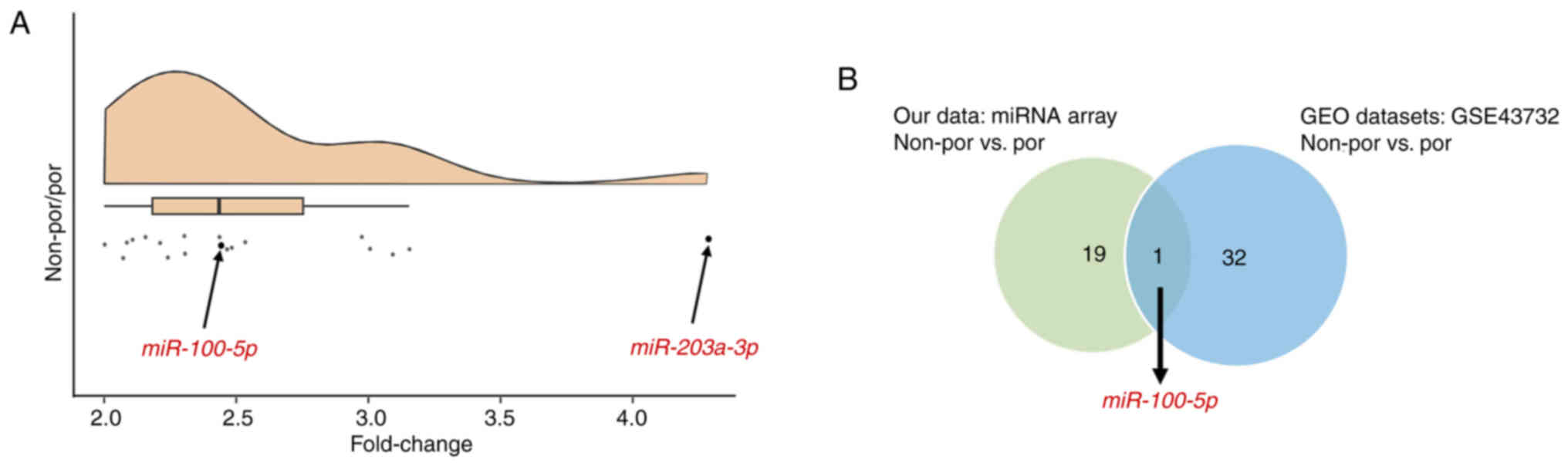

First, miRNA candidates were identified using a

miRNA array-based approach in combination with the GEO datasets.

The expression levels of each miRNA were compared between por and

non-por ESCC. miR-203a-3p was selected, which exhibited a four-fold

difference in expression during microarray analysis, ensuring that

the signal intensity of each miRNA was adequate (Fig. 1A). Additionally, miR-100-5p was

selected, which exhibited a two-fold difference in expression

during microarray analysis, supported by the GEO datasets (Fig. 1A and B).

Furthermore, analysis of a publicly available GEO

dataset revealed a consistent trend toward poorer prognosis in

patients with por ESCC (Fig. S2).

Although this difference was not statistically significant, por

ESCC is generally considered more aggressive, and this trend may

have biological relevance. Consequently, miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p

were chosen for further analyses in the present study.

Clinical significance of miR-100-5p

and 203a-3p in patients with ESCC

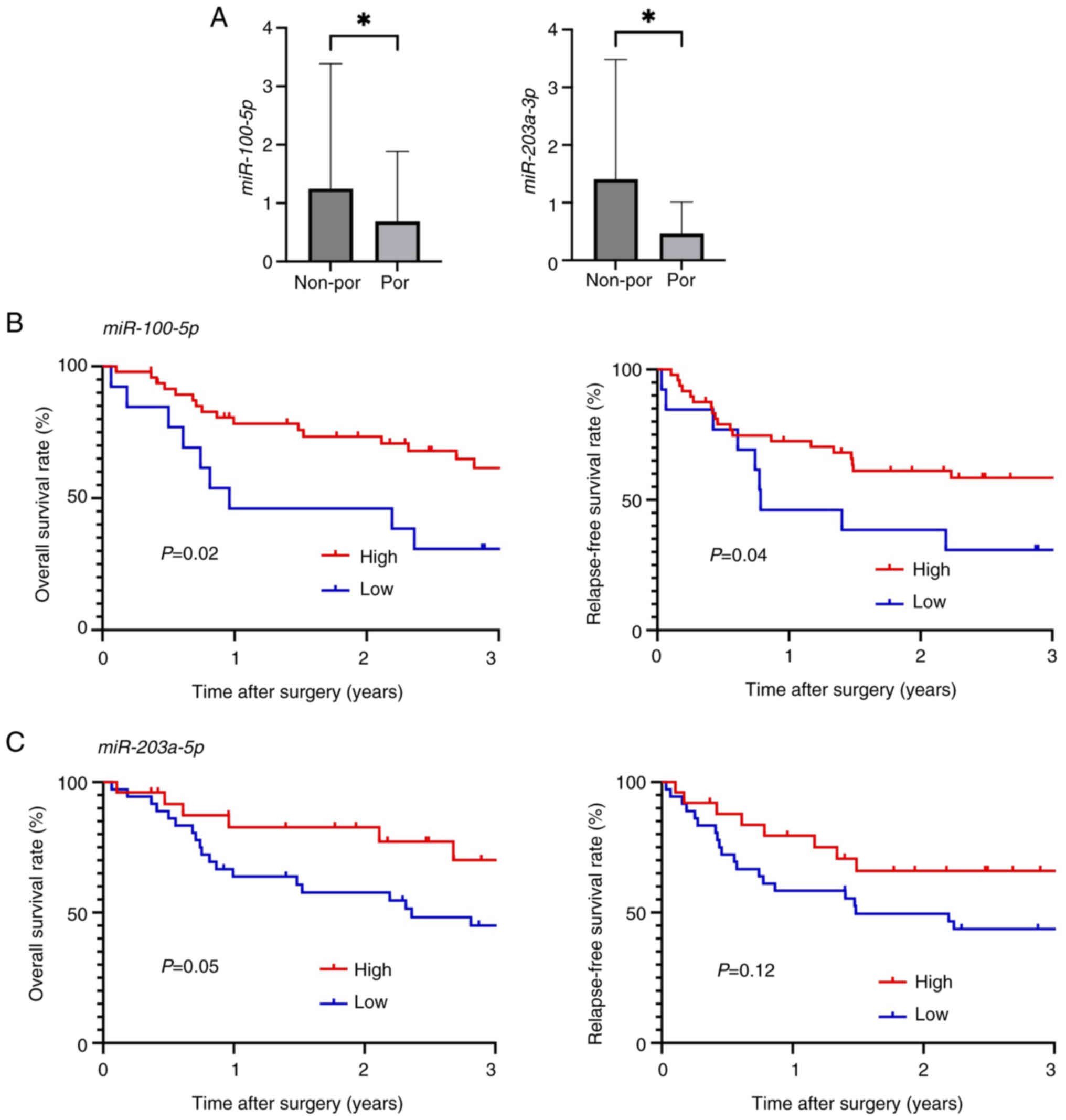

Next, the clinical significance of miR-100-5p and

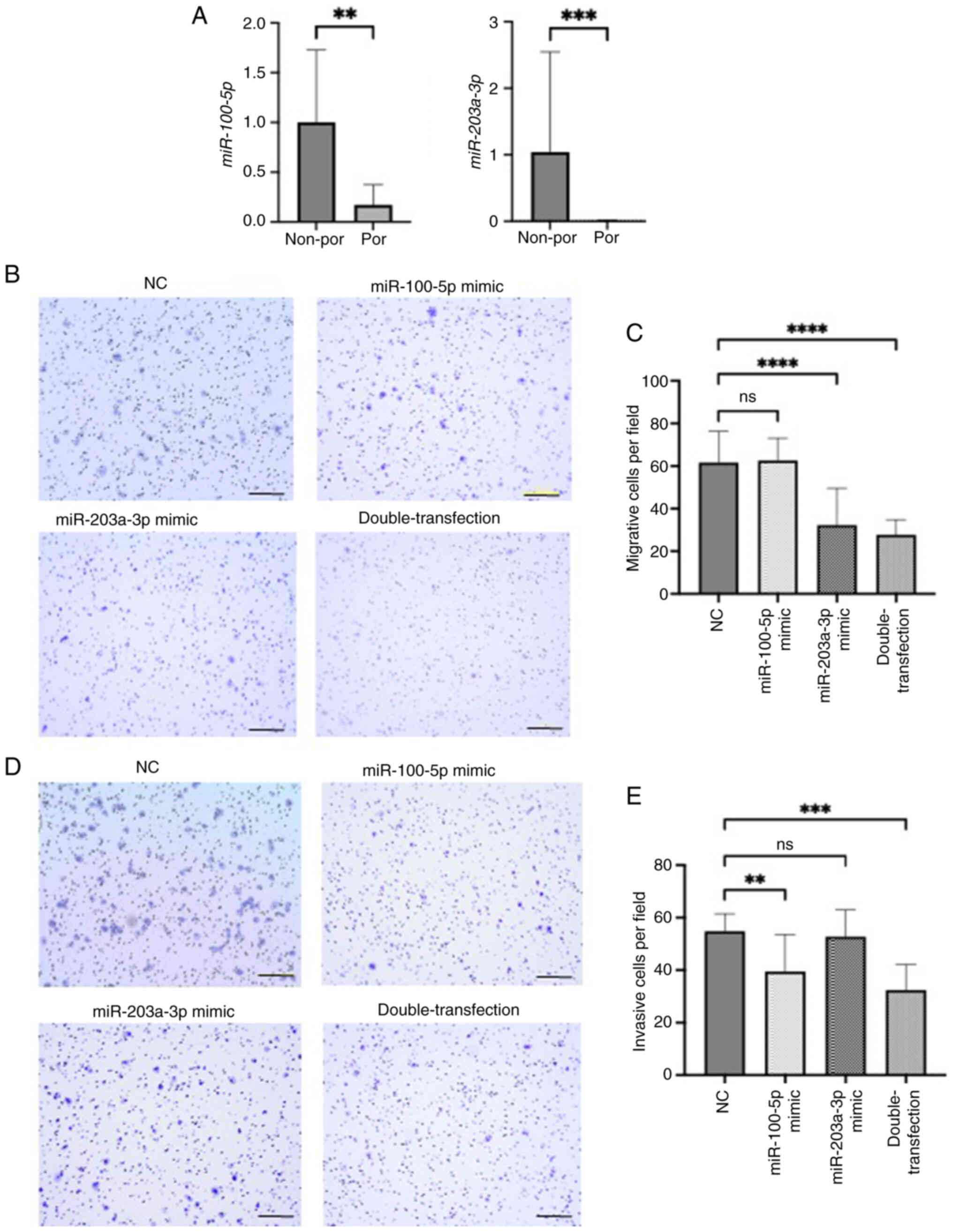

miR-203a-3p was examined in patients with ESCC. The expression

levels of miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p were significantly lower in

patients with por ESCC than in patients with non-por ESCC (P=0.02

and P=0.04, respectively) (Fig.

2A). Based on these results, a receiver operating

characteristic curve was constructed according to histological

differentiation and divided the expression levels of miR-100-5p and

miR-203a-3p into high-expression and low-expression groups for

further analysis.

In the low miR-100-5p group, tumor

differentiation was poorer, and the depth of invasion was greater

compared with the high miR-100-5p group (P<0.001 and P=0.012,

respectively). Similarly, in the low miR-203a-3p group, tumor

differentiation was poorer, the depth of invasion was greater, and

lymph node metastasis occurred more frequently compared with the

high miR-203a-3p group (P=0.01, P=0.008, and P=0.03, respectively)

(Table I).

As demonstrated in Fig.

2B, OS and RFS rates were significantly worse in the low

miR-100-5p group compared with the high miR-100-5p group (P=0.02

and P=0.04, respectively). Additionally, the OS rate was

significantly worse in the low miR-203a-3p group than in the high

miR-203a-3p group, while the RFS rate was not statistically

significant (P=0.05 and P=0.12, respectively; Fig. 2C).

Expression and function of miR-100-5p

and miR-203a-3p in ESCC cell lines

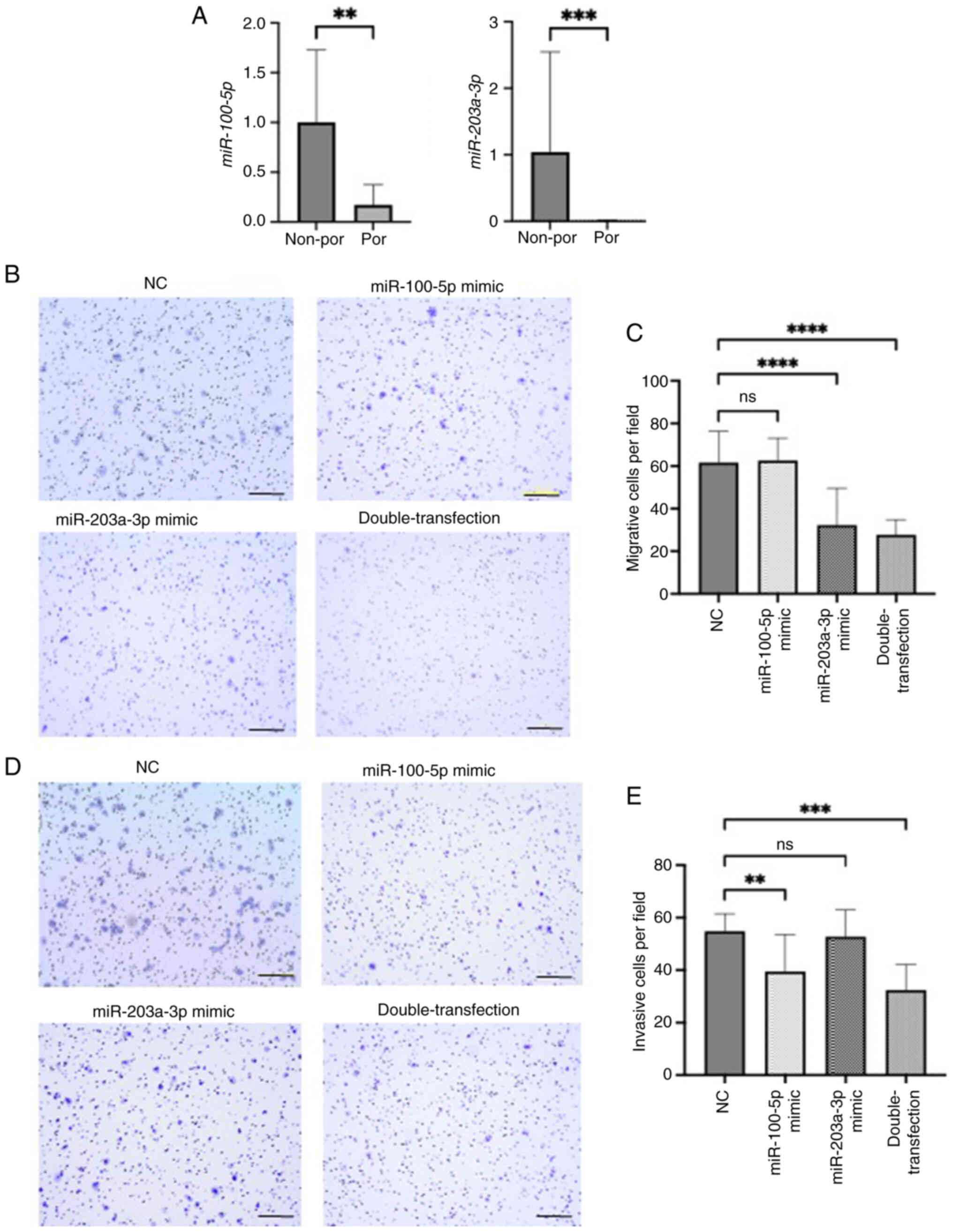

Furthermore, the function of miR-100-5p and

miR-203a-3p was examined in ESCC cell lines. First, their

expression levels were measured in ESCC cell lines and it was found

that miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p were significantly lower in poorly

differentiated ESCC cell lines compared with well- and moderately

differentiated cell lines (Fig.

3A). This expression pattern was consistent with our clinical

findings that patients with high expression of these miRNAs had

higher degree of differentiation and more favorable prognosis.

| Figure 3.(A) Relationship between tumor

differentiation and miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p levels in non-por

and por cell lines. Representative images and quantitative

measurement of (B and C) migration and (D and E) invasion assays

induced by miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p mimics in KYSE70 cells. For

double-transfection experiments, both miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p

mimics were co-transfected at 10 nM each. Scale bar, 200 µm. All

the quantitative measurements were performed in triplicate, and

data for relative quantity are presented as the mean ± SD.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 compared with NC.

miR, microRNA; por cell lines, poorly differentiated cell lines

(KYSE70, KYSE110, TE5) non-por cell lines, well- to moderately

differentiated cell lines (TE4, TE8, TE11). NC, negative

control. |

To investigate the functional roles of these miRNAs

in ESCC progression, cell migration and invasion assays were

conducted using miRNA mimics in KYSE70 cells. Transfection

efficiency for each mimic is shown in Fig. S3A. Cell migration was significantly

inhibited by the miR-203a-3p mimic alone and by the combination of

miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p mimics compared with the negative

control mimic (Fig. 3B and C). This

result indicates that miR-203a-3p plays a suppressive role in the

migratory ability of ESCC cells. Similarly, cell invasion was

significantly suppressed by the miR-100-5p mimic and by the double

transfection, indicating that miR-100-5p mainly contributes to the

inhibition of invasive potential (Fig.

3D and E). These results suggested that both miRNAs

cooperatively suppress ESCC progression through inhibition of

migration and invasion.

Potential target of miR-100-5p and

miR-203a-3p

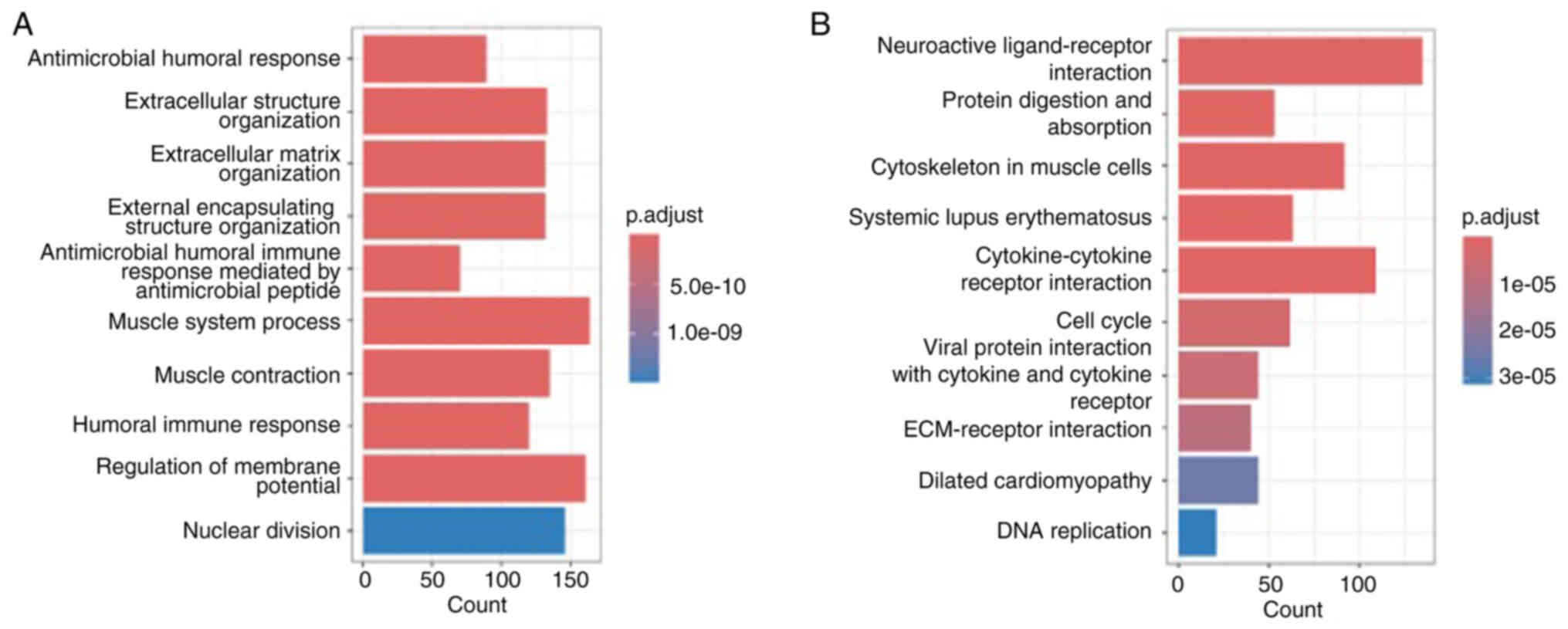

FKBP5 was identified as a putative downstream

target of both miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p using TargetScan Human

8.0 (Fig. S4). To clarify the

functional relevance of FKBP5 in ESCC, comprehensive

bioinformatics analyses were first performed. GO and KEGG

enrichment of FKBP5-associated genes revealed significant

overrepresentation of pathways involved in cell cycle control,

nuclear division and extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 4A and B). Moreover, Pearson

correlation (Fig. 5A-D) and

pre-ranked GSEA (Fig. 5E and F)

demonstrated robust positive associations between FKBP5

expression and both epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and

PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in ESCC.

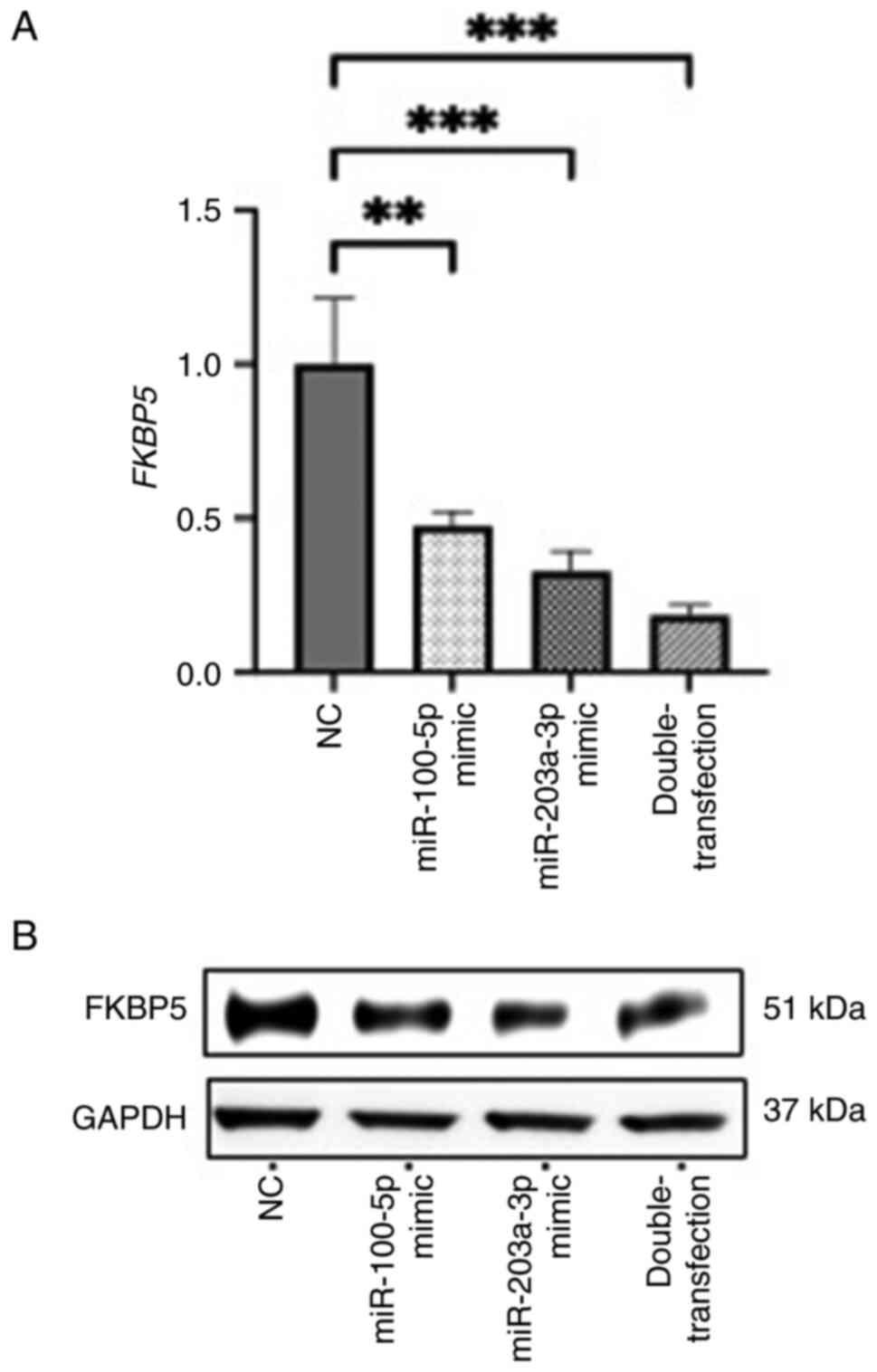

Experimentally, transfection of miR-100-5p and

miR-203a-3p mimics significantly decreased both FKBP5

transcript and protein levels, with the combined transfection of

both miRNAs producing the most pronounced reduction (Fig. 6A and B). These results suggested

that FKBP5 is a downstream target of both miRNAs and that

the two miRNAs may act cooperatively to suppress its expression. To

further confirm the functional involvement of FKBP5 in the

miRNA-mediated suppression of ESCC cell motility, rescue

experiments were performed using the double-transfection of

miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p mimics with or without FKBP5

siRNA. Adding FKBP5 siRNA to the double-transfection did not

produce additional reductions in migration or invasion compared

with the double-transfection alone, indicating that the effects of

the mimics are largely mediated by FKBP5 suppression

(Fig. S5). In clinical ESCC

samples, the expression levels of miR-100-5p/miR-203a-3p and

FKBP5 protein exhibited a negative correlation trend;

however, this association did not reach statistical significance

(Fig. S6).

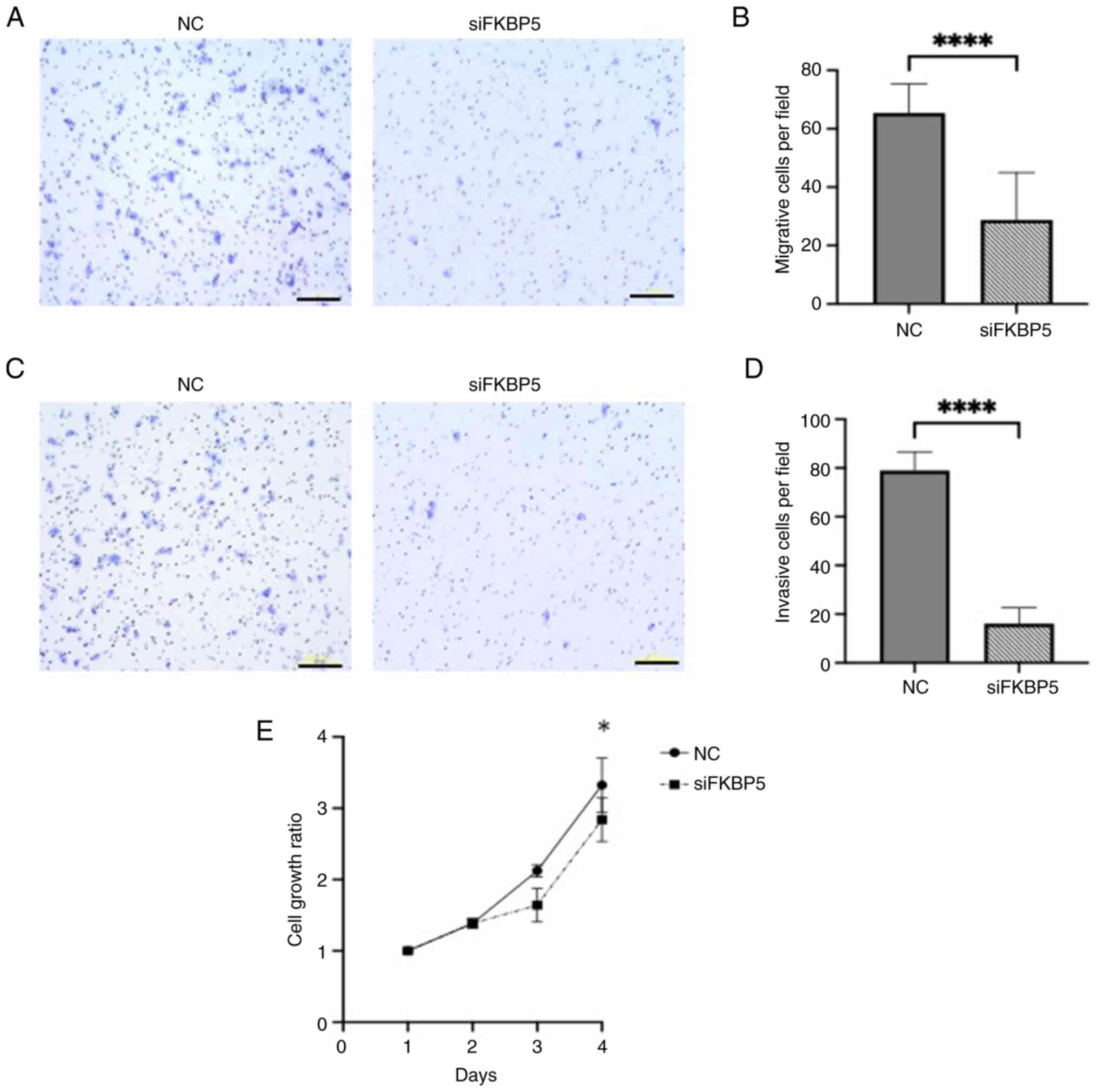

Functional assays further demonstrated that

FKBP5 knockdown, whose efficiency was confirmed by western

blotting (Fig. S3B), significantly

impaired ESCC cell migration, invasion, and increased cytotoxicity

compared with negative controls (Fig.

7A-E), suggesting that FKBP5 promotes malignant

phenotypes in ESCC cells. Additionally, apoptosis assays were

performed. Annexin V/PI flow cytometry showed no significant

differences between FKBP5 siRNA and controls (Fig. S7A). Western blotting revealed

slight changes in Caspase-3/Cleaved Caspase-3 and a marked

reduction in Bcl-2 (Fig. S7B).

These results suggested that FKBP5 knockdown alone did not

provide definitive evidence for apoptosis involvement.

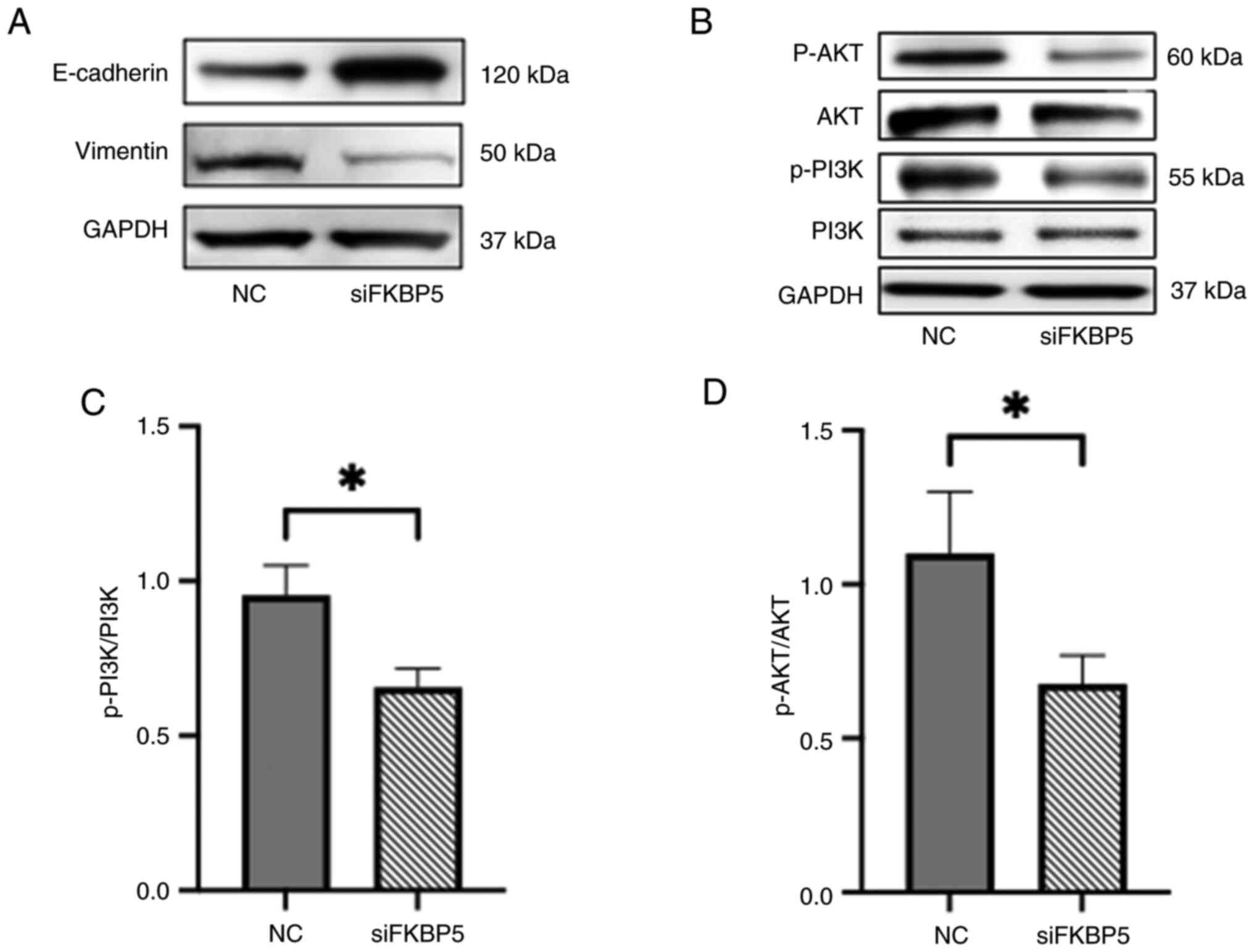

Furthermore, the effect of FKBP5 on EMT and

PI3K/AKT pathway activity was investigated by performing western

blotting for key EMT markers and phosphorylated signaling proteins.

FKBP5 knockdown led to upregulation of the epithelial marker

E-cadherin and downregulation of the mesenchymal marker vimentin

(Fig. 8A). In addition, knockdown

of FKBP5 reduced the levels of p-PI3K and p-AKT, indicating

suppression of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway (Fig. 8B-D). These findings indicated that

FKBP5 facilitates EMT and activates the PI3K/AKT pathway in

ESCC cells, and that its suppression may help reverse the

mesenchymal phenotype and inhibit oncogenic signaling associated

with invasion and metastasis.

Prognostic impact of FKBP5 expression

in patients with ESCC

Finally, the prognostic significance of FKBP5

expression was evaluated in patients with ESCC using IHC.

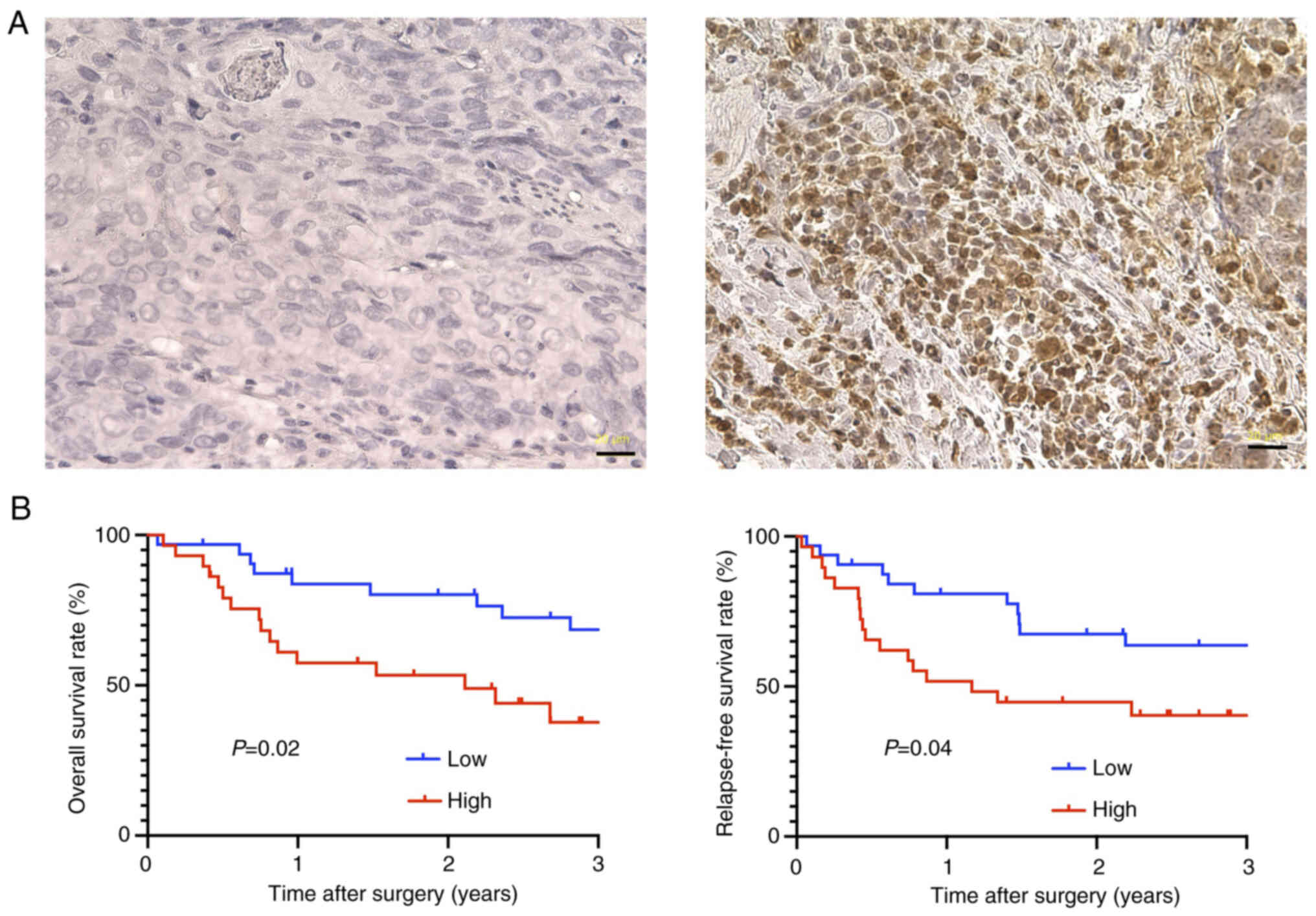

Representative IHC images are shown in Fig. 9A. Based on the median H-score,

patients were categorized into high- and low-FKBP5

expression groups. Survival analysis revealed that patients in the

high FKBP5 expression group exhibited significantly poorer

OS and RFS compared with those in the low expression group

(Fig. 9B). These findings suggested

that elevated FKBP5 expression is associated with adverse

clinical outcomes in ESCC and may serve as a potential prognostic

biomarker.

Discussion

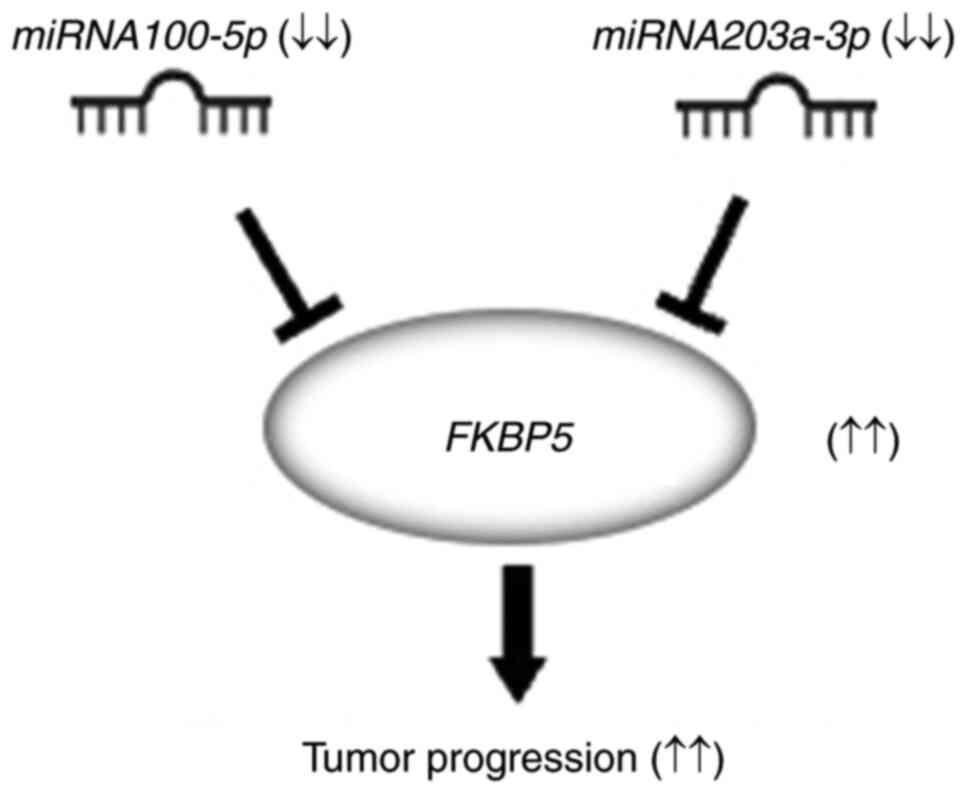

In the present study, it was aimed to elucidate the

role of miRNAs in tumor characteristics within ESCC, specifically

focusing on variations in tumor differentiation. Our findings

strongly suggest that patients with elevated levels of miR-100-5p

and miR-203a-3p have a favorable prognosis. Furthermore, it was

established that these miRNAs inhibit cellular migration and

invasion in ESCC by targeting FKBP5, a promising candidate

for therapeutic intervention in ESCC (Fig. 10).

First, tumor differentiation in ESCC was

investigated. Por ESCC exhibits distinct characteristics compared

with non-por ESCC. Patients with por ESCC have higher rates of

lymph node metastasis and recurrence. Furthermore, the pattern of

lymph node metastasis in por ESCC has been reported to differ

significantly from that in non-por ESCC (5).

Therefore, it was hypothesized that highly malignant

por ESCC could provide insights into identifying molecules that

play a crucial role in the tumor characteristics of ESCC. Through

screening using a comprehensive miRNA array-based approach and

public databases, two miRNAs were identified as potential

candidates.

There are already studies on each of the candidate

miRNAs. Regarding miR-100-5p, it suppresses CXCR7 expression, which

is implicated in initiation, adhesion, angiogenesis and metastasis

(13), and inhibits the activation

of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby suppressing

lymphangiogenesis (14). Similarly,

miR-203a-3p suppresses the activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway, which is associated with tumor initiation and therapy

resistance in ESCC (15).

From a clinical perspective, high expression levels

of these miRNAs are linked to an improved prognosis in ESCC

(16,17). The novelty of the present study lies

in identifying that both miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p are associated

with tumor differentiation in ESCC using clinical data and cell

lines. Furthermore, the combination of miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p

synergistically suppressed the malignant behavior of ESCC. In the

present study, miR-100-5p alone did not sufficiently suppress cell

migration, while miR-203a-3p alone was ineffective in suppressing

cell invasion, possibly due to differences in transfection

efficiency or concentration. Our intention was to demonstrate that

simultaneous transfection of both miRNAs more effectively

suppresses both migration and invasion.

FKBP5 was identified as a potential target of

the combined action of miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p. FKBP5 has

previously been reported as an intracellular protein that promotes

cancer progression and chemoresistance by activating the NF-κB

signaling pathway (18–21). In the present study, western blot

analysis and public database data clearly demonstrated that

FKBP5 also activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby

contributing to enhanced malignancy in ESCC (22). Moreover, siRNA-mediated FKBP5

knockdown significantly affected migration, invasion, cytotoxicity,

and several signaling proteins, whereas no appreciable changes were

detected in apoptosis assays using flow cytometry or western

blotting. These findings suggested that the oncogenic function of

FKBP5 in ESCC may be more strongly associated with cell

motility and survival signaling rather than direct regulation of

apoptosis.

FKBP5 is known to play an oncogenic role in

various malignancies, including thyroid carcinoma, renal clear cell

carcinoma and melanoma (23–25).

In gastrointestinal cancers, similar oncogenic functions have been

reported in esophageal adenocarcinoma, gastric cancer and

colorectal cancer, where elevated FKBP5 expression is

associated with poor prognosis (26–28).

Collectively, these findings suggested that FKBP5

contributes to poor prognosis by promoting EMT and activation of

the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which is consistent with our

results. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to

demonstrate that FKBP5 promotes tumor aggressiveness through

regulation by miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p in ESCC.

Based on the results of the present study,

FKBP5 has the potential to become an important therapeutic

target for ESCC in the future. Therefore, suppressing FKBP5

through the administration of both miR-100-5p and miR-203a-3p may

represent an effective treatment option for patients with ESCC.

Further basic and clinical studies are necessary to evaluate the

efficacy of this treatment strategy in suppressing FKBP5 for

ESCC.

The present study has several limitations. It was

conducted at a single institution with a limited number of

patients. In the GEO dataset used, miR-203a-3p was not listed,

which precluded combined analyses of expression arrays and public

databases. While these miRNAs appeared to be associated with tumor

differentiation, it remains unclear whether they and FKBP5

are directly involved in the differentiation process. Furthermore,

dual-luciferase reporter assays were not performed due to the lack

of necessary equipment for gene transfection in our institution. As

a result, the direct interaction between these miRNAs and

FKBP5 was not validated. However, Chen et al

(29) reported such an interaction.

In our functional rescue experiment, adding siFKBP5 to

miRNAs mimic-treated cells did not alter the suppression of

migration and invasion, consistent with the authors' hypothesis

that FKBP5 mediates these effects. Additionally, although a

negative correlation between miR-100-5p/miR-203a-3p and

FKBP5 expression was observed, the association did not reach

statistical significance (Fig.

S6). However, it is considered that a larger cohort study may

confirm a statistically significant negative correlation. Moreover,

cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay, which measures

metabolic activity as an indirect indicator of viable cell number;

therefore, it may not directly reflect cell proliferation rates.

Additional assays based on DNA synthesis or proliferation markers

would provide a more definitive evaluation of proliferation.

Nevertheless, our primary aim was to identify miRNAs associated

with tumor characteristics and potential therapeutic targets in

ESCC, and this objective was achieved. In conclusion, miR-100-5p

and miR-203a-3p inhibited tumor progression by targeting

FKBP5 in ESCC, highlighting FKBP5 as a promising

therapeutic target in ESCC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE43732 or

at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE43732.

Authors' contributions

HT, SM and DI conceived and designed the study. HT

and SM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. HT, SM, YH and

RS performed the experiments and acquired the data. HT, SM, YH, RS,

KT, WI, KeS, SF, YK and HA interpreted the data. SM and DI

supervised the study. HT, SM, YH, TO, KaS, TN and DI drafted the

manuscript. RS, KT, WI, KeS, SF, YK, HA and HK critically revised

the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be

accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the ethics

committee of the University of Yamanashi (approval no. 2723; Chuo,

Japan) for patient experiments. The study adhered to the ethical

standards outlined in The Declaration of Helsinki and its

subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was provided by all

participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

por

|

poorly differentiated carcinoma

|

|

non-por

|

well- to moderately differentiated

carcinoma

|

|

ESCC

|

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

|

|

miRNA or miR

|

microRNA

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S,

Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N and Chen W: Cancer statistics in China

and United States, 2022: Profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin

Med J (Engl.). 135:584–590. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Brierley JD, Brierley J, Gospodarowicz MK

and Wittekind C: Ebscohost: TNM classification of malignant

tumours. Wiley Blackwell/John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Chichester,

West Sussex: 2017

|

|

4

|

Li J, Wang L, Wang X, Zhao Y, Liu D, Chen

C, Zhang HP and Pan J: Preliminary study of the internal margin of

the gross tumor volume in thoracic esophageal cancer. Cancer

Radiother. 16:595–600. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhang J, Liu Y, Che F, Luo Y, Huang W,

Heng X and Li B: Pattern of lymph node metastasis in thoracic

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with poor differentiation. Mol

Clin Oncol. 8:760–766. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ha M and Kim VN: Regulation of microRNA

biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 15:509–524. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang HC and Tang KF: Clinical value of

integrated-signature miRNAs in esophageal cancer. Cancer Med.

6:1893–1903. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen Z, Li J, Tian L, Zhou C, Gao Y, Zhou

F, Shi S, Feng X, Sun N, Yao R, et al: MiRNA expression profile

reveals a prognostic signature for esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 350:34–42. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shimada Y, Imamura M, Wagata T, Yamaguchi

N and Tobe T: Characterization of 21 newly established esophageal

cancer cell lines. Cancer. 69:277–284. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tanaka H, Shibagaki I, Shimada Y, Wagata

T, Imamura M and Ishizaki K: Characterization of p53 gene mutations

in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines: Increased

frequency and different spectrum of mutations from primary tumors.

Int J Cancer. 65:372–376. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tanaka H, Shimada Y, Imamura M, Shibagaki

I and Ishizaki K: Multiple types of aberrations in the p16 (INK4a)

and the p15(INK4b) genes in 30 esophageal squamous-cell-carcinoma

cell lines. Int J Cancer. 70:437–442. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou SM, Zhang F, Chen XB, Jun CM, Jing X,

Wei DX, Xia Y, Zhou YB, Xiao XQ, Jia RQ, et al: miR-100 suppresses

the proliferation and tumor growth of esophageal squamous cancer

cells via targeting CXCR7. Oncol Rep. 35:3453–3459. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen C, Yang C, Tian X, Liang Y, Wang S,

Wang X, Shou Y, Li H, Xiao Q, Shu J, et al: Downregulation of

miR-100-5p in cancer-associated fibroblast-derived exosomes

facilitates lymphangiogenesis in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. Cancer Med. 12:14468–14483. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang L, Zhang Z, Yu X, Li Q, Wang Q, Chang

A, Huang X, Han X, Song Y, Hu J, et al: SOX9/miR-203a axis drives

PI3K/AKT signaling to promote esophageal cancer progression. Cancer

Lett. 468:14–26. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhou S, Yang B, Zhao Y, Xu S, Zhang H and

Li Z: Prognostic value of microRNA-100 in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. J Surg Res. 192:515–520. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cheng Q, Chen L and Ni L: Association of

miR-203 expression with prognostic value in patients with

esophageal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest

Surg. 36:22857802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li L, Lou Z and Wang L: The role of FKBP5

in cancer aetiology and chemoresistance. Br J Cancer. 104:19–23.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hähle A, Merz S, Meyners C and Hausch F:

The many faces of FKBP51. Biomolecules. 9:352019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Febbo PG, Lowenberg M, Thorner AR, Brown

M, Loda M and Golub TR: Androgen mediated regulation and functional

implications of fkbp51 expression in prostate cancer. J Urol.

173:1772–1777. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang T, Ma C, Zhang Z, Zhang H and Hu H:

NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation and cancer. MedComm (2020).

2:618–653. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li B, Tsao SW, Li YY, Wang X, Ling MT,

Wong YC, He QY and Cheung AL: Id-1 promotes tumorigenicity and

metastasis of human esophageal cancer cells through activation of

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Int J Cancer. 125:2576–2585. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gao Z, Yu F, Jia H, Ye Z and Yao S:

FK506-binding protein 5 promotes the progression of papillary

thyroid carcinoma. J Int Med Res. 49:30006052110083252021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mao S, Zhang D, Chen L, Tan J, Chu Y,

Huang S, Zhou W, Qin H, Xia Q, Zhao Y, et al: FKBP51 promotes

invasion and migration by increasing the autophagic degradation of

TIMP3 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis.

12:8992021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Romano S, Xiao Y, Nakaya M, D'Angelillo A,

Chang M, Jin J, Hausch F, Masullo M, Feng X, Romano MF and Sun SC:

FKBP51 employs both scaffold and isomerase functions to promote

NF-kappaB activation in melanoma. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:6983–6993.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Smith E, Palethorpe HM, Ruszkiewicz AR,

Edwards S, Leach DA, Underwood TJ, Need EF and Drew PA: Androgen

receptor and androgen-responsive gene FKBP5 are independent

prognostic indicators for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci.

61:433–443. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liu T, Wang C and Xia Z: Overexpressed

FKBP5 mediates colorectal cancer progression and sensitivity to

FK506 treatment via the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. FEBS J.

291:3128–3146. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang RG, Zhang D, Zhao CH, Wang QL, Qu H

and He QS: FKBP10 functioned as a cancer-promoting factor mediates

cell proliferation, invasion, and migration via regulating PI3K

signaling pathway in stomach adenocarcinoma. Kaohsiung J Med Sci.

36:311–317. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen G, Li X, Zhou X, Li Y, Yu H, Peng X,

Bai X, Zhang C, Feng Z, Mei Y, et al: Extracellular vesicles

secreted from mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate renal ischemia

reperfusion injury by delivering miR-100-5p targeting FKBP5/AKT

axis. Sci Rep. 14:67202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|