Introduction

In 2022, gastric cancer (GC) was reported to be the

fifth most common cancer worldwide, with ~968,000 new cases

diagnosed globally (1). Although

various treatment modalities have been developed for GC and other

cancer types, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy,

immunotherapy and targeted therapy, therapeutic outcomes remain

suboptimal, particularly in the advanced stages (2). Surgery is the primary treatment option

for early-stage GC; however, its efficacy diminishes in locally

advanced or metastatic disease (3).

Chemotherapy is widely used in advanced settings; however, it is

often associated with severe systemic toxicities that limit

long-term application (4).

Radiotherapy is primarily used for palliative symptom control or as

an adjuvant treatment; however, it has limited effectiveness in

improving overall survival (OS) in metastatic GC (5,6).

Immunotherapy has shown promising efficacy in certain subgroups,

such as in patients with high microsatellite instability or

Epstein-Barr virus-positive GC; however, response rates remain low

in unselected populations (7,8).

Traditional Chinese medicine, including herbal formulations and

acupuncture, has been integrated into supportive cancer care to

alleviate treatment-related side effects and to improve quality of

life, although robust evidence from large-scale randomized

controlled trials supporting its direct antitumor efficacy is still

lacking (9–13). Biomarker-driven targeted therapies

are effective in patients with specific molecular alterations;

however, they offer no benefit to most patients with GC lacking

these targets (14). Consequently,

despite the diversity of available treatments, the annual number of

GC-related deaths remains as high as 660,000 globally (15), indicating the urgent need to develop

more effective and better-tolerated therapeutic strategies for

GC.

Claudin 18.2 (CLDN18.2) is highly and specifically

expressed in GC (16,17), making it a primary target for

precision therapy (18). Beyond its

role as a surface biomarker, CLDN18.2 contributes to gastric

oncogenesis through multifaceted mechanisms (19). In normal gastric mucosa, CLDN18.2 is

exclusively localized to the tight junctions of polarized

epithelial cells; however, in gastric cancer, neoplastic cells

frequently lose their polarity, leading to the mislocalization of

CLDN18.2, characterized by its diffuse presence over the entire

cell membrane rather than being confined to the apical junction

complex (17). Its aberrant

expression and mislocalization in GC disrupt tight junction

integrity and epithelial polarity, thereby enhancing tumor cell

invasion and metastasis (20,21).

Furthermore, CLDN18.2 is implicated in pro-tumorigenic signaling,

potentially through interactions with integrins to activate

FAK/SRC, PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways, which promote cell

proliferation, survival and migration (22). This protein also influences the

tumor immune microenvironment (23,24);

high CLDN18.2 expression is associated with altered immune cell

infiltration (such as increased CD68+ macrophage levels)

and may contribute to an immunosuppressive context, potentially

affecting responses to immunotherapy (25,26).

These biological roles provide a strong rationale for targeting

CLDN18.2, as its inhibition may not only deliver cytotoxic agents

directly to tumor cells but also counteract its functional

oncogenic drivers.

Based on existing data, the relationship between

CLDN18.2 expression and OS in patients with GC or gastroesophageal

junction cancer is complex and remains controversial. It has been

indicated that a CLDN18.2-negative status may be associated with a

longer OS (27,28), whereas other studies have reported

that CLDN18.2 positivity is linked to improved OS (26,29).

However, several studies have found no notable association between

CLDN18.2 expression and OS or histopathological subtypes (30–32). A

2021 meta-analysis of six studies concluded that there was no

significant difference in OS between CLDN18.2-positive and

CLDN18.2-negative groups (33).

Therefore, CLDN18.2 is generally not recommended as an independent

prognostic biomarker for OS in patients with GC (20). Instead, CLDN18.2 has a more

consistent, evidence-based role as a predictive biomarker,

indicating the potential benefits of targeted therapy.

In recent years, studies on targeted therapies

against CLDN18.2, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs),

bispecific antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and

radionuclide-drug conjugates (RDCs) (34–36),

have advanced rapidly. Among these, zolbetuximab, a CLDN18.2 mAb,

has demonstrated limited efficacy in clinical trials (37–39).

However, ADCs and RDCs developed based on CLDN18.2 mAb, such as

CLDN18.2–307-ADC (40) and

[177Lu]Lu-TST001, have shown marked antitumor effects

and controllable safety profiles (41).

Both ADCs and RDCs achieve precise treatment through

specifically targeting tumor cells (42,43).

ADCs deliver cytotoxic drugs directly to tumor cells using mAbs to

recognize tumor cell-surface antigens with high specificity,

thereby minimizing toxicity to normal tissues (44). By contrast, RDCs utilize

tumor-targeting molecules labeled with radioactive isotopes to

provide precise radiation therapy, and demonstrate strong cytotoxic

effects against local refractory lesions or metastatic sites

(45). However, both classes of

drugs face inherent challenges; ADCs may experience reduced

efficacy owing to the development of resistance, whereas RDCs may

cause radiation-related side effects (46).

Existing data have indicated that ADCs and RDCs

demonstrate superior antitumor efficacy compared with CLDN18.2

mAbs, with controllable safety profiles (47). However, studies comparing the

antitumor efficacy and safety of ADCs and RDCs, as well as those

exploring their combination are lacking. To the best of our

knowledge, the current study is the first to systematically compare

the antitumor efficacy and safety of ADCs, RDCs and their

sequential combination regimens. The findings of the present study

may provide preclinical evidence to guide future clinical

applications of ADCs and RDCs. Specifically, identifying the

treatment modality or combination sequence that exhibits superior

efficacy and safety will be invaluable for designing clinical

trials and selecting therapeutic strategies for patients with

CLDN18.2-positive tumors. This comparative strategy may also serve

as a paradigm for evaluating novel targeted conjugates beyond

CLDN18.2. Therefore, the present study aimed to utilize ADC

(SYSA1801) and RDC ([177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb) agents

derived from the same CLDN18.2 mAb (SYSA1801mAb) and to compare

their efficacy and safety in the treatment of CLDN18.2-positive GC.

In addition, the potential of their combined treatment strategies

was evaluated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human GC cell line NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 was purchased

from Chengdu Besidi Biotechnology Co., Ltd. This cell line was

generated by the vendor through lentiviral transduction to stably

express CLDN18.2, and its expression was confirmed by them. in

addition, the cell line was authenticated by short tandem repeat

(STR) profiling (Genetic Testing Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The STR

profile matched the reference profile for NUGC-4 (DSMZ database,

http://www.dsmz.de) at all eight core loci and

amelogenin. The NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 cells were cultured in Roswell Park

Memorial Institute 1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 0.5%

puromycin. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2

incubator.

Animal models

Female BALB/c-nu mice (n=48; age, 6–8 weeks; weight,

18–22 g) were purchased from SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and housed

under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. The housing

environment was maintained at a temperature of 22±2°C, 50±10%

humidity, under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle. Mice had ad

libitum access to a standard SPF rodent diet and water. For the

subcutaneous xenograft model, 1×107 NUGC-4-CLDN18.2

cells in 100 µl PBS were injected into the right dorsal flank of

each mouse (48,49). Tumor-bearing mice were then

allocated to the following studies: 30 mice for the therapeutic

efficacy experiment (6 groups; n=5), 15 mice for biodistribution

studies (n=3 mice per time point across five time points) and 3

mice for positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT)

imaging. The experiment was initiated when tumor volumes reached

~300 mm3. Humane endpoint criteria were strictly

followed, and mice were euthanized immediately if the tumor volume

exceeded 2,000 mm3 or if there was a 20% decrease in

body weight relative to the baseline (day 0). All animal

experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of

Mianyang Central Hospital (ethical approval no. S20240210;

Mianyang, China).

Source of SYSA1801mAb

SYSA1801mAb is a fully human mAb targeting CLDN18.2,

which was developed by and sourced from CSPC Pharmaceutical

Holdings Group Ltd. Detailed information regarding antibody

production, plasmid structure and amino acid sequences remains

confidential. SYSA1801mAb was used to generate both diagnostic and

therapeutic radioconjugates. For PET imaging, the antibody was

conjugated to DFO and labeled with 89Zr to form

[89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb. For biodistribution studies

and therapeutic purposes, the antibody was conjugated to DOTA and

labeled with 177Lu to form the therapeutic

radioconjugate [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb (referred to

as RDC).

Flow cytometry of cell lines

First, 5×104 cells/well were pre-seeded

in a 96-well U-bottom cell culture plate, and were centrifuged at

200 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The pellets were then resuspended and

washed twice with ice cold fluorescence-activated cell sorting

(FACS) buffer (95% PBS and 5% FBS). Subsequently, the cells were

incubated in 50 µl anti-human CLDN18.2 mAb (SYSA1801mAb) for 60 min

at 4°C. The concentration of the antibody added to the first well

was 15 µg/ml, followed by twelve serial two-fold dilutions. Then,

the cells were incubated in the dark for 30 min at 4°C with a

R-phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-human IgG secondary antibody

(1:1,000; cat. no. 12499882; eBioscience; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). After incubation, the cells were washed twice with FACS

buffer, as aforementioned. The cells were resuspended in 200 µl

FACS buffer for analysis in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.). Data for 3,000 cells were collected and analyzed

using the BD FlowJo software (version v2.1.0; BD Biosciences).

Synthesis of SYSA1801mAb-DFO

SYSA1801mAb stock solution was added to an

ultrafiltration tube [molecular weight cut-off (MWCO), 30 kDa;

MilliporeSigma] and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to

remove the solvent from the stock solution. A suitable volume of

buffer A solution (Na2CO3-NaHCO3,

pH 9.5, 0.15 M) was added, and the mixture was immediately

centrifuged (14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C). This procedure was

repeated three times. The purified antibody was then transferred to

a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube, 10 times the molar mass ratio of

p-NCS-Bz-DFO [20 nmol/µl, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)]

was added, gently blown on and mixed well. The mixture was then

incubated at a constant temperature of 37°C on a shaker for 1 h at

70 rpm. Subsequently, the antibody was transferred to an

ultrafiltration tube. Following the addition of buffer C solution

(NaOAc-Ac, pH 5.5, 0.5 M), it was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10

min at 4°C, a process that was repeated three times to remove the

solvent.

Synthesis of SYSA1801mAb-DOTA

SYSA1801mAb was added to an ultrafiltration tube

(MWCO, 30 kDa; Chelex 100 sodium form), and the solvent in the

stock solution was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10

min at 4°C. A suitable volume of buffer A solution

(Na2CO3-NaHCO3, pH 9.5, 0.15 M)

was added, and the mixture was immediately centrifuged (14,000 × g

for 10 min at 4°C). This procedure was repeated three times. The

purified antibody was then transferred to a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube

and 10 times the molar mass ratio of p-NCS-Bz-DOTA (20 nmol/µl,

dissolved in DMSO) was added. The mixture was incubated at a

constant temperature of 37°C on a shaker for 1 h at 70 rpm.

Subsequently, the antibody was transferred to an ultrafiltration

tube. Following the addition of buffer C solution (NaOAc-Ac, pH

5.5, 0.5 M), it was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, a

procedure that was repeated three times to remove the solvent.

Synthesis of

[89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb

High-purity yttrium foil (purity >99.99%,

specification: 11×16×0.65 mm; Suzhou Changyou Gas Co., Ltd.) was

procured as the target material and then irradiated with a

cyclotron to induce nuclear reactions. After irradiation, the

target material was subjected to acid dissolution and purification

to obtain 89Zr with acceptable radioactivity and

chemical purity in the form of [89Zr]Zr-oxalate.

[89Zr]Zr-oxalate was added to the centrifuge tube, and

the pH was adjusted to ~7.0 with solution B (0.5 M

Na2CO3) and left at room temperature for 3

min. SYSA1801mAb-DFO was then added to the solution at a 1:2

labeling ratio, and 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazin-1-yl]

ethanesulfonic acid solution was added to the centrifuge tube

according to solution B and total volume of 89Zr. The

mixture was reacted in a metal bath at 37°C for 90 min, shaking the

solution by hand every 10 min. At the end of the reaction, the

labeling rate of the samples was determined using thin-layer

chromatography (TLC) (50).

Synthesis of

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb

To synthesize [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb,

SYSA1801mAb-DOTA and 177LuCl3 (sourced from

the Institute of Nuclear Physics and Chemistry, China Academy of

Engineering Physics, Mianyang, China) were combined at a 1:2 ratio

and incubated the mixture for 1 h at 42°C in a metal bath. After

the reaction, the labeling rate of the samples was determined using

TLC. Microfiber cellophane (cat. no. SG10001; iTLC-SG-Glass

microfiber chromatography paper impregnated with silica gel;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was cut into long strips of paper (10

cm long and 1.5 cm wide), and a marked line was drawn 1.5 cm from

the bottom as a scale for spiking. Subsequently, 2 µl of the

radioactive sample was pipetted to the marked line of the

microfiber glassine strip, which was placed into a sodium citrate

unfolding system after spotting (sodium citrate-citric acid, 0.5 M,

pH 5.5). The reaction mixture was analyzed by high-performance

liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II

system (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) to determine the radiochemical

purity. The separation was performed on an Agilent XDB-C18

reversed-phase analytical column (4.6×250 mm, 5 µm; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) maintained at 25°C. A sample volume of 30 µl

was injected. The mobile phase consisted of water with 0.1%

trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA. The

purification method was as follows: The column was initially

conditioned and washed with 0.1% TFA in water, then eluted with a

linear gradient of 13 to 33% acetonitrile (with 0.1% TFA) in water

over 20 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Radio-HPLC detection was

performed using a γ-radiation detector for 177Lu, and

ultraviolet-HPLC detection was carried out at 254 nm

absorption.

In vitro stability

To determine in vitro stability, 10 µl

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb was added separately to 15 µl

saline, and to 15 µl 1640 medium containing 10% FBS. The mixture

was left at room temperature, and the labeling rate was determined

by TLC at 4, 24, 48, 96 and 168 h for the two groups.

Binding assays

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb was prepared

as aforementioned and the radiochemical purity of

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb was >99%. For the

subsequent experiment, NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 cells (1×105

cells/well) were placed into a 100-µl centrifuge tube. The total

binding of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb was determined by

adding it to cell suspensions at concentrations of 0.025–10.000 nM.

Non-specific binding was determined by adding 50X half maximal

effective concentration (EC50) cold SYSA1801mAb to

NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 cell mixtures at one concentration. The cells were

incubated with 5 µCi [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb for 1 h

at room temperature and washed three times with FACS buffer (95%

PBS and 5% FBS). Bound and unbound radioactive fractions were

collected and measured using a gamma counter (GC-1500; ANHUI USTC

Zonkia Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd.). Saturation binding

capacity (Bmax) and EC50 values were

calculated using PRISM v9.0 (Dotmatics).

PET/CT imaging

Tumor-bearing mice were sedated with isoflurane

(2.0–2.5% in 2 l/min air) for intravenous injection of 4 MBq (104

µg) [89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb for PET/CT imaging. During

the uptake periods (4, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 192 h post-injection),

the mice were housed individually in a temperature-controlled room

with free access to food and water, minimizing stress-related

metabolic changes. Before PET/CT, the mice were re-anesthetized,

placed on a heated imaging bed (37±0.5°C), and monitored to

maintain stable body temperature and respiration (respiratory rate:

60–80 breaths/min). Imaging was performed using Super Nova

micro-PET/CT [PINGSENG Healthcare (Kunshan) Inc]. Spherical volumes

of interest were delineated to encompass the tumor, major organs

(the liver, spleen, kidney and heart), and background region (the

thigh skeletal muscles). Decay-corrected injected activity,

measured via pre- and post-injection weighing, and mouse body

weight, recorded before the imaging, were used to calculate the

percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). This

methodology was used to evaluate the target specificity of

[89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb.

Biodistribution

Each tumor-bearing mouse was injected with 0.8 MBq

(10 µg) [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb via the tail vein. As

aforementioned, the mice were euthanized at selected time points

(4, 24, 48, 96 and 144 h post-injection), with three mice per time

point. Subsequently, major tissues and organs, including the heart,

liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, skeletal muscle (thigh muscle),

femur (bone), whole blood, stomach, pancreas and intestines, were

collected. All of the samples were blotted dry with a filter paper

and weighed using an electronic balance.

The radioactivity of each sample was measured using

an automated gamma counter (GC-1500; ANHUI USTC Zonkia Scientific

Instruments Co., Ltd.) with a counting time of 10 sec. Background

radioactivity was subtracted to correct the raw counts. The total

injected radioactivity was determined by measuring the

radioactivity of the injection syringe before and after

administration (to account for residual radioactivity in the

syringe). Tissue uptake was expressed as the %ID/g, calculated

using the following formula: %ID/g=(corrected tissue radioactivity

count/total injected radioactivity count) × (1/tissue wet weight)

×100. Mouse biodistribution data (%ID/g) at multiple time points

were converted to human organ %ID using the %kg/g scaling approach.

For each organ, the scaled human %ID(t) was fitted with a

bi-exponential model; the area under the fitted curve was

integrated to infinity to derive the cumulated activity, which was

then normalized by the administered activity (A0) to

yield the time-integrated activity coefficient: τ=(1/A0)

∫0^∞ A_org(t) dt, reported in MBq·h/MBq.

ADC drug details

SYSA1801 (also known as EO3021; sourced from CSPC

Pharmaceutical Holdings Group Ltd.) is an ADC drug that targets

CLDN18.2. It consists of an mAb (SYSA1801mAb) that targets CLDN18.2

and monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE), conjugated via a cleavable

linker with a drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) of 2. Detailed synthesis

information is confidential. SYSA1801 is currently undergoing phase

I clinical trials for the treatment of advanced solid tumors,

demonstrating promising antitumor efficacy and manageable safety

(NCT05009966).

Therapeutic dosing rationale and

schedule

Dose selection

In BALB/c nude tumor-bearing mouse models, prior

studies established 11.1 MBq as an appropriate dose for

177Lu-labeled full-length mAb for therapeutic use

(51,52). At this dose, the RDC demonstrated

favorable tolerability, manageable toxicity and effective tumor

growth suppression. Therefore, 11.1 MBq was selected as the single

administration dose of RDC in the present study.

Antibody mass equivalence

To isolate payload effects, an identical mAb

(SYSA1801mAb; 50 nmol/kg) was administered to RDC, ADC and mAb

groups. This enabled a direct comparison of 177Lu with

cytotoxic drug efficacy under equivalent target engagement. For RDC

preparation, a 1:2 antibody-to-177Lu mass ratio was

utilized, where 11.1 MBq RDC contained 150 µg antibody. To maintain

antibody dose equivalence, both the ADC and mAb groups contained

150 µg per administration. The dosing for each group was as

follows: [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb (11.1 MBq, 50

nmol/kg SYSA1801mAb), SYSA1801 (50 nmol/kg) and SYSA1801mAb (50

nmol/kg).

Grouping and intervention of

tumor-bearing mice

Tumor-bearing mice were randomized into six groups

(n=5/group), with interventions administered on days 0 and 14 as

follows: The RDC group, 11.1 MBq (50 nmol/kg)

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb on days 0 and 14; the ADC

group, 50 nmol/kg SYSA1801 on days 0 and 14; the ADC→RDC group, 50

nmol/kg SYSA1801 on day 0 and 11.1 MBq (50 nmol/kg)

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb on day 14; the RDC→ADC group,

11.1 MBq (50 nmol/kg) [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb on day

0 and 50 nmol/kg SYSA1801 on day 14; the mAb group, 50 nmol/kg

SYSA1801mAb on days 0 and 14; the normal saline (NS) group, NS on

days 0 and 14. Tumor-bearing mice were administered injections

though the tail vein, with a dose volume of 200 µl/mouse. A

schematic diagram of grouping and intervention for the

tumor-bearing mice is shown in Fig.

1A.

Monitoring and subsequent testing

Tumor size and body weight of the mice were

monitored starting from day 0 (first injection day). Tumor size was

measured using a digital caliper, with the volume calculated as

(length × width2)/2 (length, longest diameter of the

tumor; width, shortest diameter perpendicular to the length), and

body weight was measured using an electronic balance. Both

parameters were assessed on Tuesday and Friday after the first

injection. The tumor growth inhibition rate (TGI%) was calculated

as follows: TGI%=[1-(ΔT/ΔC)] ×100, where ΔT is the change in mean

tumor volume of the treatment group from baseline, and ΔC is the

change in mean tumor volume of the control group from baseline.

The study endpoints were set as follows: i) Tumor

volume reaching 2,000 mm3 (triggering euthanasia); or

ii) a 20% decrease in body weight relative to the baseline weight

on day 0. Mice that did not meet these criteria were considered

survivors for the purpose of the study. At these endpoints, the

mice were anesthetized via inhalation of 5% isoflurane, and 500–800

µl blood was collected from the orbital venous plexus. Mice that

reached predefined humane endpoints underwent blood collection from

the orbital venous plexus and subsequent immediate euthanasia.

Animals were first anesthetized via inhalation of 5%

isoflurane in an induction chamber. Upon loss of consciousness, the

mice were transferred to a euthanasia chamber and exposed to 100%

CO2 at a flow rate displacing 40% of the chamber

volume/min until respiratory arrest occurred. Death was

subsequently confirmed by cervical dislocation. A portion of the

blood sample was immediately used for routine hematological tests

using an automated hematology analyzer (Mira BF; Shanghai RuiYu

Biotech Co., Ltd.), and the remaining blood samples were

centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to separate the serum,

which was used for subsequent hepatorenal function tests using an

automated biochemistry analyzer (BS-360S; Shenzhen Mindray

Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, major organs (the

heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) were harvested, fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 24 h at room temperature, embedded in

paraffin, and sectioned into 5-µm slices. The slices were stained

with hematoxylin for 8 min and eosin for 3 min at room temperature,

and observed under a light microscope (CX-31; Olympus Corporation)

to evaluate histopathological changes (such as inflammatory cell

infiltration, tissue necrosis and cellular degeneration), and to

assess drug-induced hematological and organ toxicity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS

Statistics for Windows (version 22.0; IBM Corp). For comparisons

involving >2 groups, one-way analysis of variance was conducted,

followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons where

appropriate. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. Survival analysis was performed using

Kaplan-Meier curves and differences between groups were assessed

using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. For the pre-specified

pairwise comparisons among the four key treatment groups (RDC, ADC,

ADC→RDC, RDC→ADC), a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was

applied. A total of six comparisons were conducted, resulting in a

corrected significance threshold of α=0.0083. Statistical

significance for these pairwise comparisons was declared only when

P<0.0083.

Results

Cell transfection and animal

models

Flow cytometry confirmed a stable high expression of

CLDN18.2 in the NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 cells (Fig. 1B). Finally, a subcutaneous positive

GC xenograft model was established using NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 cells for

subsequent animal experiments. When the NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 ×enografts

had grown to a volume of 732.75±197.96 mm3, the

therapeutic experiment was initiated.

Binding and stability

The integrity and radiochemical purity of

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb were determined to be >99%

by HPLC using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II HPLC system (Fig. 1C). Subsequent incubation in NS and

1640 medium (containing 10% FBS) for up to 7 days showed no

degradation of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb, as confirmed

by radiolabeled TLC (Fig. 1E).

Radioligand-binding assays were conducted using NUGC-4-CLDN18.2

cells. The Bmax of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb

to NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 cells (1×05 cells) was 1,149±48.16

nmol, and the equilibrium dissociation constant was 24.36±3.5

nmol/l (Fig. 1D).

PET/CT imaging of

[89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb

PET/CT imaging revealed that 4 h post-injection,

[89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb accumulated in the tumor, with

a clear tumor outline visible at 24 h post-injection (Fig. 2A). Over time, radioactive uptake in

the tumor gradually increased. The maximum uptake of

[89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb at the tumor site was observed

at 48 h, with an uptake of ~4.94±1.06%ID/g (n=3) (Fig. 2B). Region of interest was further

defined and radioactive uptake in the tumor, heart (blood), liver,

spleen, muscle and kidneys was assessed. Radioactive uptake in

non-target organs, such as the heart (blood), liver and kidneys,

gradually decreased over time.

![(A) Positron emission

tomography-computed tomography images showing tumor-specific

accumulation of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb in

tumor-bearing mice over time, in contrast to that in other

non-target tissues. (B) Quantitative region of interest analysis of

the tumor, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and muscle in

tumor-bearing mice at 4, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 192 h after injection

of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb. (C) Biodistribution results

at 4, 24, 48, 96 and 144 h after injection of

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb. (D) Tumor-to-blood, (E)

tumor-to-liver and (F) tumor-to-kidney ratios at 4, 24, 48, 96 and

144 h after injection of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences across

the different time points for each ratio were determined by one-way

analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple

comparisons. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. %DI/g,

percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue; mAb, monoclonal

antibody.](/article_images/or/55/1/or-55-01-09009-g01.jpg) | Figure 2.(A) Positron emission

tomography-computed tomography images showing tumor-specific

accumulation of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb in

tumor-bearing mice over time, in contrast to that in other

non-target tissues. (B) Quantitative region of interest analysis of

the tumor, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and muscle in

tumor-bearing mice at 4, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 192 h after injection

of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb. (C) Biodistribution results

at 4, 24, 48, 96 and 144 h after injection of

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb. (D) Tumor-to-blood, (E)

tumor-to-liver and (F) tumor-to-kidney ratios at 4, 24, 48, 96 and

144 h after injection of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences across

the different time points for each ratio were determined by one-way

analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple

comparisons. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. %DI/g,

percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue; mAb, monoclonal

antibody. |

Biodistribution of

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb

Biodistribution results indicated that

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb effectively targeted tumors

in the NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 model. Over time, tumor uptake increased,

reaching a peak at 48 h (16.44±3.13%ID/g) (Fig. 2C). Liver uptake peaked at 24 h

(12.06±2.63%ID/g) and kidney uptake peaked at 4 h (4.96±1.66%ID/g).

As time progressed, uptake in the liver and kidneys gradually

decreased. Following blood circulation,

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb was rapidly cleared from the

bloodstream. The concentration of radioactivity in the blood

decreased by over 80% during the period from 4 and 48 h

post-injection. Between 4 and 96 h post-injection, the

tumor-to-blood ratio gradually increased, reaching a maximum ratio

of 31.62±17.13 (Fig. 2D).

Tumor-to-liver and tumor-to-kidney ratios exhibited fluctuating

trends, with the highest values observed at 48 h (Fig. 2E and F). Dosimetry results are

presented in Table I.

| Table I.Estimates of time-integrated activity

coefficients for human organs from mouse biodistribution data. |

Table I.

Estimates of time-integrated activity

coefficients for human organs from mouse biodistribution data.

| Source organ | Kinetics value,

MBq-h/MBq |

|---|

| Adrenal glands | 0 |

| Brain | 0 |

| Esophagus | 0 |

| Eyes | 0 |

| Gallbladder

contents | 0 |

| Left colon | 0 |

| Small

intestine | 0.777 |

| Stomach

contents | 0.268 |

| Right colon | 0 |

| Rectum | 0 |

| Heart contents | 1.07×10¹ |

| Heart wall | 0.566 |

| Kidneys | 0.246 |

| Liver | 1.02×10¹ |

| Lungs | 1.32 |

| Pancreas | 0.059 |

| Prostate | 0 |

| Salivary

glands | 0 |

| Red bone

marrow | 0 |

| Cortical bone | 1.70×10¹ |

| Trabecular

bone | 0 |

| Spleen | 0.31 |

| Testes | 0 |

| Thymus | 0 |

| Thyroid | 0 |

| Urinary bladder

contents | 0 |

| Total body | 0 |

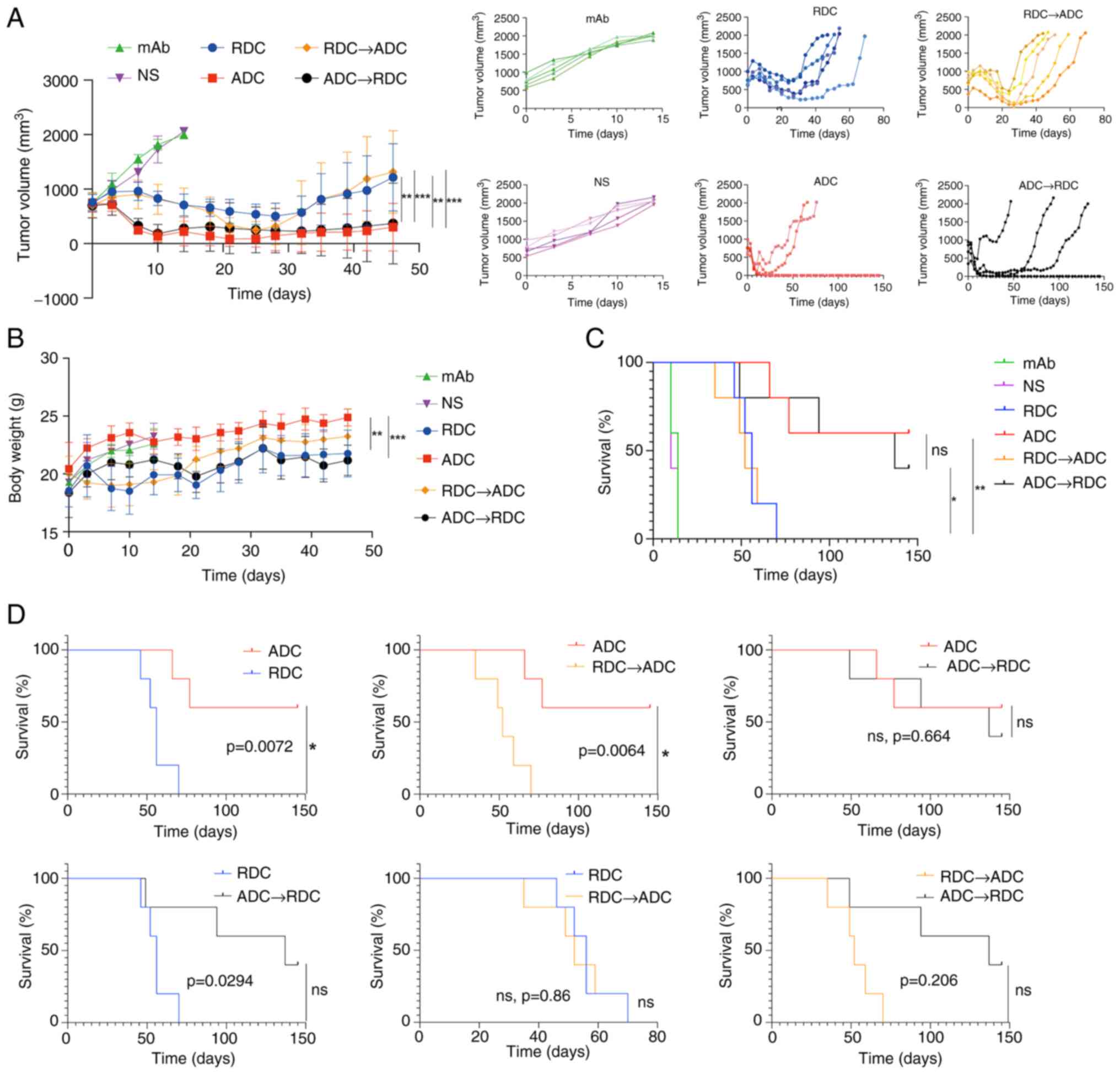

Effect of treatment

In the NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 model, the NS and mAb groups

reached humane endpoints by day 14 post-treatment. The average

tumor volume in the mAb group was 1,906.58±71.11 mm3

(TGI%=4.57%), while in the NS group, it was 1,997.88±71.11

mm3, with no significant difference between the two

groups (Figs. 3A and S1). A total of 14 days after the first

administration, in the RDC monotherapy group, the average tumor

volume was 686.86±153.12 mm3 (TGI%=105.32%), in the ADC

group, it was 222.49±236.45 mm3 (TGI%=139.80%), in the

RDC→ADC group, it was 713.65±271.28 mm3 (TGI%=100.60%),

and in the ADC→RDC group, it was 278.79±381.72 mm3

(TGI%=137.93%). Significant differences in tumor volume were

observed between some treatment groups, and the detailed pairwise

comparisons are presented in Table

SI. On day 46 post-treatment, the average tumor volume in the

RDC group was 871.63±503.97 mm3, in the ADC group, it

was 303.05±439.34 mm3, in the RDC→ADC group, it was

941.74±803.32 mm3, and in the ADC→RDC group, it was

248.31±474.01 mm3. Significant differences in tumor

volume were observed between the following pairs: RDC and ADC, RDC

and ADC→RDC, ADC and RDC→ADC, and RDC→ADC and ADC→RDC. On day 14

post-treatment, the mice in the NS and mAb groups showed a gradual

increase in body weight, whereas the mice in the other treatment

groups experienced an initial weight decrease followed by a slow

increase (Fig. 3B). Significant

differences in weight were observed between some of the groups.

Specifically, the ADC→RDC group showed a statistically significant

difference compared with the ADC group, and the RDC group also

differed significantly from the ADC group.

On day 46 post-treatment, the body weight of the

mice in the RDC, ADC, ADC→RDC and RDC→ADC groups showed fluctuating

increments, with no significant difference in body weight among the

treatment groups (Table SII). On

day 145 post-treatment, complete remission (CR) rate in the ADC

group was 60%, with the OS rate also at 60%. In the ADC→RDC group,

the CR rate was 40% and the OS rate was 40%, whereas the OS rate in

the other groups was 0%. Statistically significant differences in

OS rates were observed between the ADC and RDC groups, as well as

between the ADC and RDC→ADC groups (Fig. 3C and D).

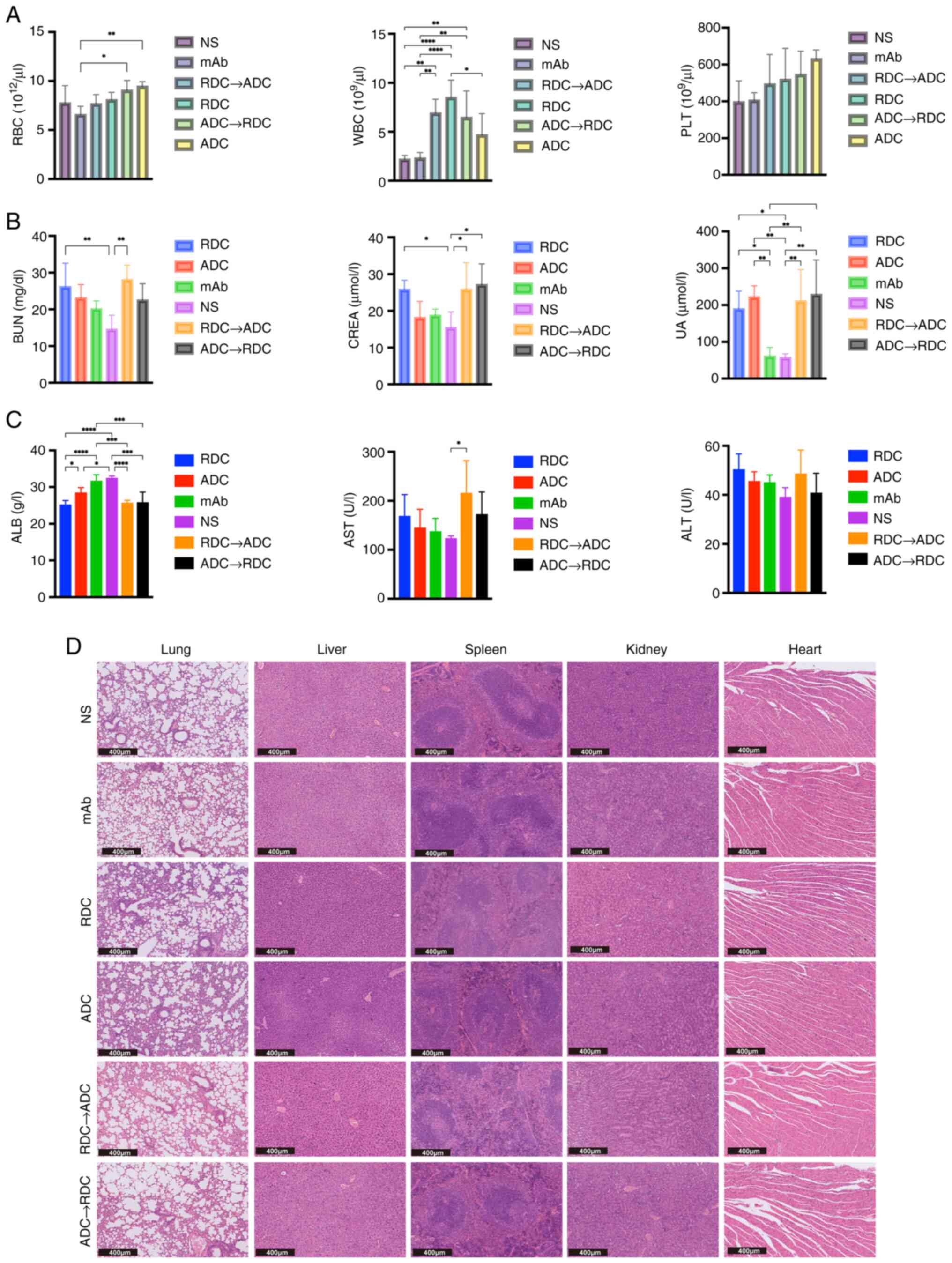

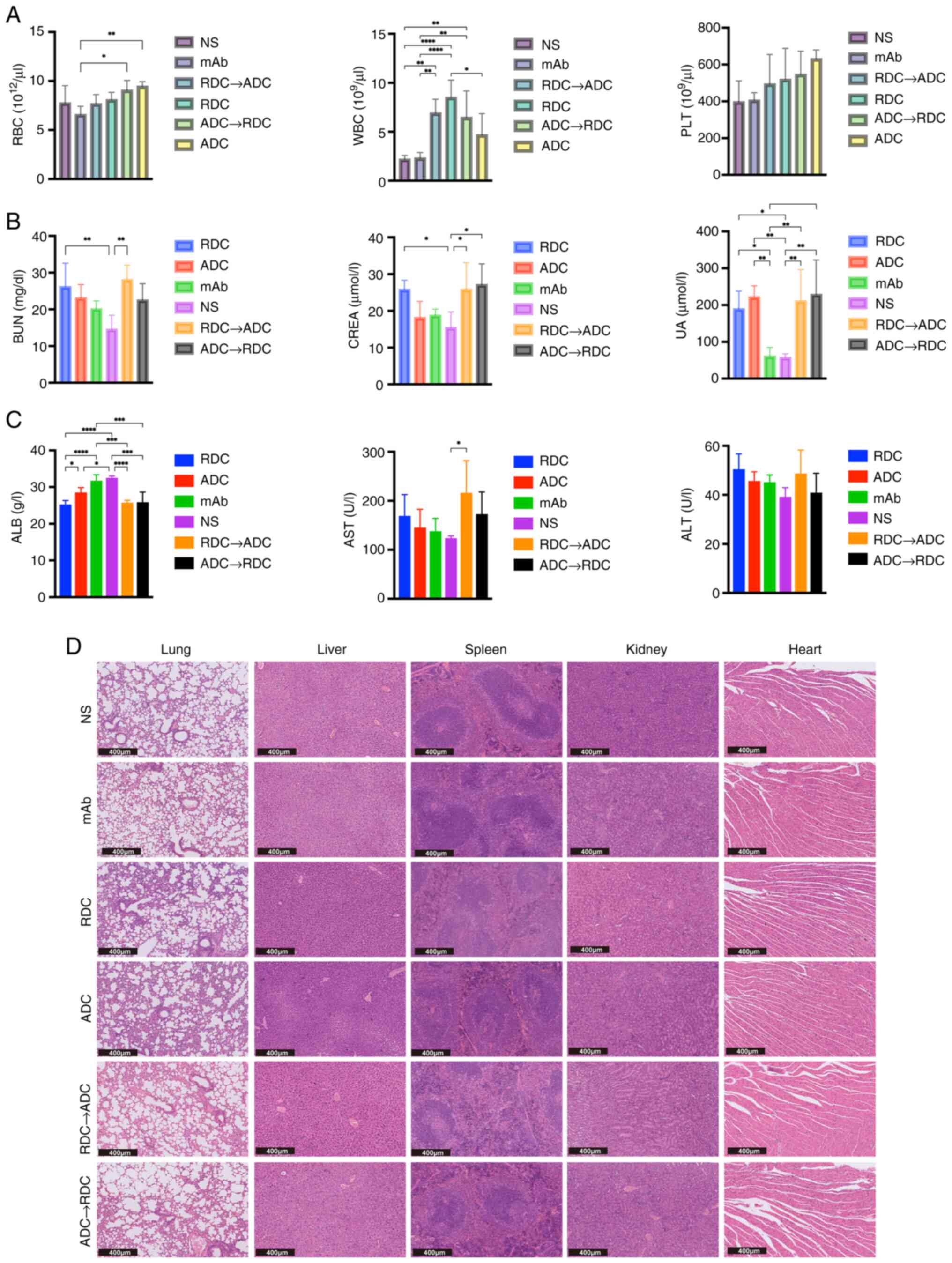

Toxicity of treatment

To comprehensively evaluate the potential adverse

effects of these treatments, hematological, biochemical and

histopathological analyses were conducted. Hematological analysis

revealed elevated white blood cell counts in all treatment groups

relative to the NS control group (Fig.

4A), with detailed results of pairwise comparisons between the

groups provided in Table SIII.

This elevation might suggest an inflammatory response or stress

induced by treatment, which warrants further exploration of the

impact on the immune system. Red blood cell counts showed minimal

differences across groups, with a significant difference observed

only between the ADC and mAb groups, and between the mAb and

ADC→RDC sequential therapy groups. No significant differences were

found in platelet counts among the groups. Levels of hepatocellular

injury markers, alanine and aspartate aminotransferases exhibited

only minor fluctuations across the treatment groups, with no

significant differences observed (Fig.

4C). However, a significant decrease in albumin levels was

noted in all the treatment groups, except the mAb group, compared

with those in the NS group (P<0.05), suggesting a potential

impairment of hepatic synthetic function, which is a known side

effect of certain chemotherapeutic and targeted agents (51). More pronounced toxicological

profiles were observed in the kidneys. Compared with those in the

NS group, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr) and uric acid

levels were elevated to varying degrees in the treatment groups,

with relatively greater changes in the combination treatment and

RDC groups (Fig. 4C; Table SIII). This consistent pattern

suggests a potential impairment of the glomerular filtration rate

and renal function.

| Figure 4.(A) WBC, RBC and PLT counts of each

treatment group at the end of treatment (n=5 mice/group). (B) BUN,

CREA and UA levels in each treatment group at the end of treatment.

(C) ALB, AST and ALT levels in each treatment group at the end of

treatment. (D) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of

tissues collected from euthanized mice from each treatment group.

Statistical differences across the groups were determined by

one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test for

multiple comparisons. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; ALB, albumin; ALT

alanine amino transferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN,

blood urea nitrogen; CREA, creatinine; mAb, monoclonal antibody;

NS, normal saline; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; RDC,

radionuclide-drug conjugate; UA, uric acid; WBC, white blood

cell. |

Histopathological examination provided evidence for

the biochemical findings (Fig. 4D).

Although the architecture of the heart, lungs and liver remained

intact across all the groups, notable changes were observed in the

kidneys and spleen. Specifically, the mice treated with RDC and

combination therapy exhibited partial damage and deformation of

glomeruli and renal tubules, consistent with renal function

deterioration, as indicated by elevated BUN and Cr levels.

Disruption of the splenic follicular structure was also observed in

these groups. These changes were markedly milder in the ADC and mAb

monotherapy groups compared with those in the RDC and combination

therapy groups. Cardiac, pulmonary and hepatic tissues remained

largely intact across all the groups, with no signs of notable

drug-induced injury.

Overall, the toxicity profile indicated that RDC and

the combination therapy were associated with controllable but

notable nephrotoxicity and potential effects on hepatic synthetic

function. The absence of marked histopathological damage in the

heart and lungs suggests favorable cardiotoxicity and pulmonary

toxicity safety profiles.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first preclinical experiment comparing the efficacy and safety

of ADCs, RDCs and their sequential combinations targeting the same

receptor. The current study systematically evaluated the

therapeutic efficacy of CLDN18.2-targeted ADC, RDC and various

sequential combination therapies in a preclinical GC mouse model.

The results showed that the ADC group was significantly associated

with improved key efficacy endpoints, such as OS and CR rates,

compared with those in both the RDC and RDC→ADC groups, alongside a

more favorable safety profile. Although the survival benefit of the

ADC→RDC combination treatment did not significantly differ from

that of ADC monotherapy, the combination therapy group exhibited

higher blood toxicity, and liver and kidney damage. These findings

suggest that ADC monotherapy may have superior efficacy and safety

in the current preclinical model. From a mechanistic perspective,

the therapeutic advantage of ADCs primarily arises from their

ability to precisely deliver cytotoxic drugs via antibody-targeted

delivery (53). Additionally, the

cleavable linker of ADCs can generate a ‘bystander effect’, which

helps eliminate nearby antigen-negative cells (54). In the present study, a 60% CR rate

was maintained for 5 months following ADC monotherapy, which is

closely associated with high stability of the CLDN18.2 antigen

during the treatment period. However, existing clinical studies

have indicated that prolonged use of ADCs may lead to acquired

resistance through mechanisms such as abnormal antigen

internalization or lysosomal escape (55,56).

The absence of such acquired resistance in the current study may be

linked to the relatively low dosing frequency (only two

administrations) and short observation period in the current study.

Future studies should assess the long-term effects of treatment on

drug resistance.

In the combination therapy strategy, the tumor CR

rate in the ADC→RDC group was higher than that in the RDC→ADC

group, with a 40% difference. Although the sample size (n=5/group)

in the current study was limited, resulting in a low statistical

power, and this difference did not reach statistical significance

after correction for multiple comparisons, the magnitude of the

observed trend and effect size still suggests that the sequence of

administration may be a potential factor influencing antitumor

efficacy. This finding provides a valuable preliminary hypothesis

for future large-scale studies. Furthermore, based on previous

literature, it may be hypothesized that administering ADC first

could create a favorable condition for subsequent RDC therapy

through several potential mechanisms: i) Rapidly reducing tumor

burden by downregulating hypoxia-inducible factor 1α expression,

which alleviates the tumor hypoxic microenvironment (57), thereby enhancing the sensitivity of

the tumor to radiotherapy (58);

ii) ADC-induced G2/M phase cell cycle arrest, which

makes tumor cells more sensitive during radiotherapy (59); and iii) conversely, if RDC therapy

is used first, it may induce radiation-induced fibrosis, which

increases the hydraulic pressure of the tumor stroma, hindering the

intratumoral penetration of ADC drugs (60). These potential mechanisms may

explain the efficacy trend observed in the current study.

Previous studies have shown that ADC and RDC

monotherapies demonstrate relatively good efficacy in

CLDN18.2-targeted therapy (61,62).

For example, [177Lu]Lu-TST001 has exhibited marked

efficacy and low short-term toxicity in preclinical GC models

(41), although no long-term

toxicity has been observed. In the current study, a 5-month

long-term observation revealed that although RDC treatment

effectively inhibited tumor growth, it was associated with

relatively high hematological and visceral toxicity. This suggests

that CLDN18.2-RDC therapy requires further optimization to reduce

side effects. Moreover, in a previous study, CLDN18.2–307-ADC

induced sustained tumor regression in cell-derived xenograft and

patient-derived xenograft models with manageable toxicity (40). These findings are consistent with

the results of this study, where a 60% CR rate was observed in the

ADC treatment group, and the tumors remained stable after

regression without recurrence. However, the prolonged use of ADC

may result in resistance issues, including target antigen

downregulation, antigen loss or mutations, leading to a gradual

reduction in therapeutic efficacy (63). Therefore, the potential efficacy of

the ADC→RDC combination therapy in resistant patients is of

particular importance. By initially using ADC to reduce tumor

burden and improve the microenvironment, subsequent RDC treatment

may eliminate residual tumor cells more effectively, thereby

lowering recurrence risk (64).

This treatment strategy is especially suitable for ADC-resistant

patients for whom RDC may serve as an effective adjunct

therapy.

The National Medical Products Administration has

approved CLDN18.2 mAb (zolbetuximab) in combination with

fluoropyrimidine and platinum-based chemotherapy as a first-line

treatment for locally advanced unresectable or metastatic

CLDN18.2-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

(HER2)-negative gastric or gastroesophageal junction

adenocarcinoma. However, in the present study, the mAb-CLDN18.2

monotherapy group did not show any significant antitumor efficacy.

This outcome may be attributed to the relatively low doses

administered. The conventional clinical dose is 800

mg/m2 (65,66), whereas the dose used in the current

study was only 50 nmol/kg. At such a low dose, the antibody may not

achieve sufficient target engagement or elicit a robust immune

response to produce antitumor effects as monotherapy. Future

studies should consider using higher doses in order to observe more

pronounced therapeutic outcomes.

The present study has several design limitations

that warrant further discussion. First, owing to experimental

constraints, the pharmacokinetic characteristics and maximum

tolerated doses of different treatment regimens were not

systematically compared, which may affect the generalizability of

the conclusions regarding efficacy and safety. To control for core

variables, a uniform dose of 150 µg (50 nmol/kg) mAb was used as a

baseline. This decision was based on the following considerations:

First, the fixed DAR (DAR=2) of ADCs is structurally consistent

with the radionuclide-to-antibody labeling ratio (value=2) of RDCs.

Second, prior studies have shown that 1.1 MBq

177Lu-labeled full antibodies (150 µg) effectively

suppress tumor growth with good tolerability (51,52).

Although there are differences in the mechanisms of action between

ADCs and RDCs (67,68), an equal antibody dosage ensures

comparability in target occupancy, thereby providing a basis for a

fair evaluation of the antitumor activity of different carrier

systems. Although the absence of pharmacokinetic parameters limits

the depth of mechanistic interpretation, the cross-modal drug

comparison paradigm and sequential strategy established in the

present study remain valuable and may provide insights for future

studies.

Second, the present study used only a single

conventional tumor model and did not account for the potential

effect of different GC subtypes or resistance models on treatment

outcomes. Tumor heterogeneity suggests that a single model may not

fully capture the diversity in clinical treatments. Therefore,

future studies should incorporate multi-model validation,

particularly the use of resistance models, to enhance the

generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, although the

results obtained from a single model may not be broadly applicable,

the favorable outcomes observed with both ADC and ADC→RDC

sequential combination therapies in the current study offer

valuable insights and guidance for subsequent validation in

resistance models and the development of treatment strategies for

advanced clinical patients.

Third, all efficacy and toxicity observations were

derived from the NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 ×enograft model, which differs

fundamentally from human GC in several key aspects: i) Tumor

microenvironment: The murine model lacks the complex human tumor

microenvironment that regulates drug response and toxicity profiles

in patients. ii) Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic disparities:

Interspecies differences in drug metabolism, distribution and

elimination may notably alter treatment outcomes. iii) CLDN18.2

expression heterogeneity: Human GC demonstrates variable CLDN18.2

expression patterns (such as focal vs. diffuse and high vs. low)

and potentially treatment-modifying co-mutations (including in HER2

and TP53), whereas the NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 model represents only a

single CLDN18.2-overexpressing cell line, thereby limiting the

generalizability of the findings across different patient

subgroups.

Fourth, the study included multiple groups, but the

sample size was limited (n=5/group), which resulted in a low

statistical power. After correction for multiple comparisons, some

intergroup differences in the survival analysis did not reach

statistical significance, and thus, these specific findings were

only presented as trends. Future studies will require a larger

sample size to validate these findings.

Finally, the current study did not explore the

potential acquired resistance mechanisms to ADC therapy, which is

directly relevant to the development of subsequent treatment

strategies for patients with resistance in clinical settings. These

limitations underscore the need for cautious interpretation of the

results and emphasize the requirement for future clinical studies

to establish the comparative efficacy and safety of ADC and RDC

strategies in patients with CLDN18.2-positive GC.

In conclusion, the present preclinical findings

suggest that ADC monotherapy may demonstrate superior efficacy and

safety profiles when compared with RDC monotherapy. Sequential

combination therapy starting with ADC appears to be more favorable

than that which starts with RDC. Although ADC→RDC sequential

therapy did not significantly outperform ADC monotherapy in this

model, it may serve as an effective subsequent treatment

strategy.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by the Key

Laboratory of Nuclear Technology (grant nos. 2021HYX001 and 2022

HYX015), the Mianyang Science and Technology Bureau (Minyang

Science and Technology Program; grant no. 2023ZYDF073) and the

Mianyang Municipal Finance Bureau (grant no.

miancaijian2022-186).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XD, XY and YY conceived and designed the study. HD,

XH, BL, LR, JW, MT, DW, YZhu, JL and XY performed the experiments.

HD, XH, BL YZha, TD, and XY analyzed the data. HD was a major

contributor in writing the manuscript. XD and XY assume overall

responsibility for the manuscript. XD and HD confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. XD, HD, YZha and TD were

responsible for supervision and funding acquisition. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethical

Review Board of Mianyang Central Hospital (approval no.

S20240210).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CLDN18.2

|

claudin 18.2

|

|

ADC

|

antibody-drug conjugate

|

|

RDC

|

radionuclide-drug conjugate

|

|

ALB

|

albumin

|

|

ALT

|

alanine aminotransferase

|

|

AST

|

aspartate aminotransferase

|

|

BUN

|

blood urea nitrogen

|

|

CREA

|

creatinine

|

|

UA

|

uric acid

|

|

WBC

|

white blood cells

|

|

RBC

|

red blood cells

|

|

PLT

|

platelets

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

CR

|

complete remission

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal AL: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sexton RE, Al Hallak MN, Diab M and Azmi

AS: Gastric cancer: A comprehensive review of current and future

treatment strategies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 39:1179–1203. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van

Grieken NC and Lordick F: Gastric cancer. Lancet. 396:635–648.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ling Q, Huang ST, Yu TH, Liu HL, Zhao LY,

Chen XL, Liu K, Chen XZ, Yang K, Hu JK, et al: Optimal timing of

surgery for gastric cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol.

21:3772023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Merchant SJ, Kong W, Mahmud A, Booth CM

and Hanna TP: Palliative radiotherapy for esophageal and gastric

cancer: Population-based patterns of utilization and outcomes in

Ontario, Canada. J Palliat Care. 38:157–166. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Haggstrom L, Chan WY, Nagrial A, Chantrill

LA, Sim HW, Yip D and Chin V: Chemotherapy and radiotherapy for

advanced pancreatic cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

12:CD0110442024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yan SY and Fan JG: Application of immune

checkpoint inhibitors and microsatellite instability in gastric

cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 30:2734–2739. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Nie Y, Schalper KA and Chiang A:

Mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance in small cell lung cancer.

Cancer Drug Resist. 7:552024.

|

|

9

|

Xu W, Li B, Xu M, Yang T and Hao X:

Traditional Chinese medicine for precancerous lesions of gastric

cancer: A review. Biomed Pharmacother. 146:1125422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu Y, Huang T, Wang L, Wang Y, Liu Y, Bai

J, Wen X, Li Y, Long K and Zhang H: Traditional Chinese Medicine in

the treatment of chronic atrophic gastritis, precancerous lesions

and gastric cancer. J Ethnopharmacol. 337:1188122025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Dai Z, Tan C, Wang J, Wang Q, Wang Y, He

Y, Peng Y, Gao M, Zhang Y, Liu L, et al: Traditional Chinese

medicine for gastric cancer: An evidence mapping. Phytother Res.

38:2707–2723. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gao S, Xu T, Wang W, Li J, Shan Y, Wang Y

and Tan H: Polysaccharides from Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bge, the

extraction, purification, structure characterization, biological

activities and application of a traditional herbal medicine. Int J

Biol Macromol. 311:1434972025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Gao S, Wang Y, Shan Y, Wang W, Li J and

Tan H: Rhizoma Coptidis polysaccharides: Extraction, separation,

purification, structural characteristics and bioactivities. Int J

Biol Macromol. 320:1456772025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wang G, Huang Y, Zhou L, Yang H, Lin H,

Zhou S, Tan Z and Qian J: Immunotherapy and targeted therapy as

first-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol. 198:1041972024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhang X, Yang L, Liu S, Cao LL, Wang N, Li

HC and Ji JF: Interpretation on the report of global cancer

statistics 2022. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 46:710–721. 2024.(In

Chinese).

|

|

16

|

Inamoto R, Takahashi N and Yamada Y:

Claudin18.2 in advanced gastric cancer. Cancers (Basel).

15:57422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sahin U, Koslowski M, Dhaene K, Usener D,

Brandenburg G, Seitz G, Huber C and Türeci O: Claudin-18 splice

variant 2 is a pan-cancer target suitable for therapeutic antibody

development. Clin Cancer Res. 14:7624–7634. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Baek JH, Park DJ, Kim GY, Cheon J, Kang

BW, Cha HJ and Kim JG: Clinical implications of claudin18.2

expression in patients with gastric cancer. Anticancer Res.

39:6973–6979. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bunga OD and Danilova NV: Claudin-18.2 and

gastric cancer: From physiology to carcinogenesis. Arkh Patol.

86:92–99. 2024.(In Russian). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mathias-Machado MC, de Jesus VHF, Jácome

A, Donadio MD, Aruquipa MPS, Fogacci J, Cunha RG, da Silva LM and

Peixoto RD: Claudin 18.2 as a new biomarker in gastric cancer-what

should we know? Cancers (Basel). 16:6792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Nakayama I, Qi C, Chen Y, Nakamura Y, Shen

L and Shitara K: Claudin 18.2 as a novel therapeutic target. Nat

Rev Clin Oncol. 21:354–369. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tojjari A, Idrissi YA and Saeed A:

Emerging targets in gastric and pancreatic cancer: Focus on claudin

18.2. Cancer Lett. 611:2173622024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Seckin Y, Arici S, Harputluoglu M, Yonem

O, Yilmaz A, Ozer H, Karincaoglu M and Demirel U: Expression of

claudin-4 and beta-catenin in gastric premalignant lesions. Acta

Gastroenterol Belg. 72:407–412. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Konno H, Lin T, Wu R, Dai X, Li S, Wang G,

Chen M, Li W, Wang L, Sun BC, et al: ZL-1211 exhibits robust

antitumor activity by enhancing ADCC and activating NK

Cell-mediated inflammation in CLDN18.2-High and -Low expressing

gastric cancer models. Cancer Res Commun. 2:937–950. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kubota Y, Kawazoe A, Mishima S, Nakamura

Y, Kotani D, Kuboki Y, Bando H, Kojima T, Doi T, Yoshino T, et al:

Comprehensive clinical and molecular characterization of claudin

18.2 expression in advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction

cancer. ESMO Open. 8:1007622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Castillo DR, Guo M, John Kim K II, Zhong

H, Brar G, Wu S, Mannan R, Cecilia Lau S, Xing Y and Peter Wu S:

Association of Claudin18.2 expression, PD-L1, and prognostic

implications in gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancers. J

Clin Oncol. 43:e160942025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wang C, Wang Y, Chen J, Wang Y, Pang C,

Liang C, Yuan L and Ma Y: CLDN18.2 expression and its impact on

prognosis and the immune microenvironment in gastric cancer. BMC

Gastroenterol. 23:2832023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Rha SY, Kwon WS, Lee CK, Jung M, Shin S

and Kim H, Park S, Yoo JH and Kim H: Co-expressing pattern of

multiple biomakers and dynamic change of Claudin18.2 expression

after systemic chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer. J Clin

Oncol. 43:40372025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lordick F, Van Cutsem E, Shitara K, Xu RH,

Ajani JA, Shah MA, Oh M, Ganguli A, Chang L, Rhoten S, et al:

Health-related quality of life in patients with CLDN18.2-positive,

locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric or

gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: Results from the

SPOTLIGHT and GLOW clinical trials. ESMO Open. 9:1036632024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kim HD, Choi E, Shin J, Lee IS, Ko CS, Ryu

MH and Park YS: Clinicopathologic features and prognostic value of

claudin 18.2 overexpression in patients with resectable gastric

cancer. Sci Rep. 13:200472023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pellino A, Brignola S, Riello E, Niero M,

Murgioni S, Guido M, Nappo F, Businello G, Sbaraglia M, Bergamo F,

et al: Association of CLDN18 protein expression with

clinicopathological features and prognosis in advanced gastric and

gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas. J Pers Med. 11:10952021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Waters R, Sewastjanow-Silva M, Yamashita

K, Abdelhakeem A, Iwata KK, Moran D, Elsouda D, Guerrero A, Pizzi

M, Vicentini ER, et al: Retrospective study of claudin 18 isoform 2

prevalence and prognostic association in gastric and

gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. JCO Precis Oncol.

8:e23005432024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ungureanu BS, Lungulescu CV, Pirici D,

Turcu-Stiolica A, Gheonea DI, Sacerdotianu VM, Liliac IM, Moraru E,

Bende F and Saftoiu A: Clinicopathologic relevance of claudin 18.2

expression in gastric cancer: A Meta-analysis. Front Oncol.

11:6438722021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Gao J, Wang Z, Jiang W, Zhang Y, Meng Z,

Niu Y, Sheng Z, Chen C, Liu X, Chen X, et al: CLDN18.2 and 4-1BB

bispecific antibody givastomig exerts antitumor activity through

CLDN18.2-expressing tumor-directed T-cell activation. J Immunother

Cancer. 11:e0067042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Optimism Surrounds Claudin 18.2 ADC.

Cancer Discov. 14:122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li D, Ding L, Chen Y, Wang Z, Zeng Z, Ma

X, Huang H, Li H, Qian X, Yang Z and Zhu H: Exploration of

radionuclide labeling of a novel scFv-Fc fusion protein targeting

CLDN18.2 for tumor diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Med Chem.

266:1161342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sahin U, Türeci Ö, Manikhas G, Lordick F,

Rusyn A, Vynnychenko I, Dudov A, Bazin I, Bondarenko I, Melichar B,

et al: FAST: A randomised phase II study of zolbetuximab (IMAB362)

plus EOX versus EOX alone for first-line treatment of advanced

CLDN18.2-positive gastric and gastro-oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

Ann Oncol. 32:609–619. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Shitara K, Kawazoe A, Hirakawa A,

Nakanishi Y, Furuki S, Fukuda M, Ueno Y, Raizer J and Arozullah A:

Phase 1 trial of zolbetuximab in Japanese patients with CLDN18.2+

gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci.

114:1606–1615. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Klempner SJ, Lee KW, Shitara K, Metges JP,

Lonardi S, Ilson DH, Fazio N, Kim TY, Bai LY, Moran D, et al:

ILUSTRO: Phase II multicohort trial of zolbetuximab in patients

with advanced or metastatic claudin 18.2-Positive gastric or

gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res.

29:3882–3891. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

O'Brien NA, McDermott MSJ, Zhang J, Gong

KW, Lu M, Hoffstrom B, Luo T, Ayala R, Chau K, Liang M, et al:

Development of a novel CLDN18.2-directed monoclonal antibody and

antibody-drug conjugate for treatment of CLDN18.2-positive cancers.

Mol Cancer Ther. 22:1365–1375. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zeng Z, Li L, Tao J, Liu J, Li H, Qian X,

Yang Z and Zhu H: [177Lu]Lu-labeled anti-claudin-18.2

antibody demonstrated radioimmunotherapy potential in gastric

cancer mouse xenograft models. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging.

51:1221–1232. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Dumontet C, Reichert JM, Senter PD,

Lambert JM and Beck A: Antibody-drug conjugates come of age in

oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 22:641–661. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Lu X, Zhu Y, Deng X, Kong F, Xi C, Luo Q

and Zhu X: Development of a supermolecular Radionuclide-drug

conjugate system for integrated radiotheranostics for Non-small

cell lung cancer. J Med Chem. 67:11152–11167. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chau CH, Steeg PS and Figg WD:

Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer. Lancet. 394:793–804. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zhou L, Lu Y, Liu W, Wang S, Wang L, Zheng

P, Zi G, Liu H, Liu W and Wei S: Drug conjugates for the treatment

of lung cancer: From drug discovery to clinical practice. Exp

Hematol Oncol. 13:262024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Khongorzul P, Ling CJ, Khan FU, Ihsan AU

and Zhang J: Antibody-drug conjugates: A comprehensive review. Mol

Cancer Res. 18:3–19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhou KI, Strickler JH and Chen H:

Targeting Claudin-18.2 for cancer therapy: Updates from 2024 ASCO

annual meeting. J Hematol Oncol. 17:732024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Yeh CL, Pai MH, Li CC, Tsai YL and Yeh SL:

Effect of arginine on angiogenesis induced by human colon cancer:

In vitro and in vivo studies. J Nutr Biochem. 21:538–543. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kinjo K, Kizaki M, Muto A, Fukuchi Y,

Umezawa A, Yamato K, Nishihara T, Hata J, Ito M, Ueyama Y, et al:

Arsenic trioxide (As2O3)-induced apoptosis and differentiation in

retinoic acid-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia model in

hGM-CSF-producing transgenic SCID mice. Leukemia. 14:431–438. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Yao Y, Ren Y, Hou X, Zhu J, Ma X, Liu S,

Liu T, Zhang Q, Ma X, Yang Z, et al: Construction and preclinical

evaluation of a zirconium-89 labelled monoclonal antibody targeting

PD-L2 in lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 168:1156022023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Du H, Hao X, Lin B, Tang M, Wang D, Yang

X, Wang J, Qin L, Yang Y and Du X: 177Lu-labeled anticlaudin 6

monoclonal antibody for targeted therapy in esophageal cancer. J

Nucl Med. 66:377–384. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zheng L, Li C, Yang X, Liu J, Wang G, Zhou

Z, Zhu X, Gong J and Yang J: GD2-targeted theranostics of

neuroblastoma with [64Cu]Cu/[177Lu]Lu-hu3F8.

Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 52:1764–1777. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Drago JZ, Modi S and Chandarlapaty S:

Unlocking the potential of antibody-drug conjugates for cancer

therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 18:327–344. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Baah S, Laws M and Rahman KM:

Antibody-Drug Conjugates-A tutorial review. Molecules. 26:29432021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Chen YF, Xu YY, Shao ZM and Yu KD:

Resistance to antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: mechanisms

and solutions. Cancer Commun (Lond). 43:297–337. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Díaz-Rodríguez E, Gandullo-Sánchez L,

Ocaña A and Pandiella A: Novel ADCs and strategies to overcome

resistance to Anti-HER2 ADCs. Cancers (Basel). 14:1542021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Jain RK: Normalizing tumor

microenvironment to treat cancer: bench to bedside to biomarkers. J

Clin Oncol. 31:2205–2218. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Beckers C, Pruschy M and Vetrugno I: Tumor

hypoxia and radiotherapy: A major driver of resistance even for

novel radiotherapy modalities. Semin Cancer Biol. 98:19–30. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Pawlik TM and Keyomarsi K: Role of cell

cycle in mediating sensitivity to radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys. 59:928–942. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Straub JM, New J, Hamilton CD, Lominska C,

Shnayder Y and Thomas SM: Radiation-induced fibrosis: Mechanisms

and implications for therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

141:1985–1994. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Yamamoto K, Nakayama I and Shitara K: A

new molecular targeted agent for gastric Cancer-The Anti-Claudin

18.2 antibody, zolbetuximab. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 51:1111–1118.

2024.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Liu Y, Wang X, Zhang N, He S, Zhang J, Xu

X and Song S: Utility of 131I-HLX58-Der for the precision

treatment: Evaluation of a preclinical

radio-antibody-drug-conjugate approach in mouse models. Int J

Nanomedicine. 20:723–739. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chang HL, Schwettmann B, McArthur HL and

Chan IS: Antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: Overcoming

resistance and boosting immune response. J Clin Invest.

133:e1721562023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Jiao J, Qian Y, Lv Y, Wei W, Long Y, Guo

X, Buerliesi A, Ye J, Han H, Li J, et al: Overcoming limitations

and advancing the therapeutic potential of antibody-oligonucleotide

conjugates (AOCs): Current status and future perspectives.

Pharmacol Res. 209:1074692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Shah MA, Shitara K, Ajani JA, Bang YJ,

Enzinger P, Ilson D, Lordick F, Van Cutsem E, Gallego Plazas J,

Huang J, et al: Zolbetuximab plus CAPOX in CLDN18.2-positive

gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: The

randomized, phase 3 GLOW trial. Nat Med. 29:2133–2141. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Shitara K, Shah MA, Lordick F, Van Cutsem

E, Ilson DH, Klempner SJ, Kang YK, Lonardi S, Hung YP, Yamaguchi K,

et al: Zolbetuximab in gastric or gastroesophageal junction

adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 391:1159–1162. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Hammood M, Craig AW and Leyton JV: Impact

of endocytosis mechanisms for the receptors targeted by the

currently approved Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)-A necessity for

future ADC research and development. Pharmaceuticals (Basel).

14:6742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zhang S, Wang X, Gao X, Chen X, Li L, Li

G, Liu C, Miao Y, Wang R and Hu K: Radiopharmaceuticals and their

applications in medicine. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:12025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![(A) Flow chart of the experimental

design. Created with BioRender.com. (B) Flow cytometry was used to

detect CLDN18.2 expression in NUGC-4-CLDN18.2 cells. Blue line:

Anti-SYSA1801mAb (PE); red line: isotype control (PE). (C)

Radiochemical purity of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb

determined by HPLC was >99%. Upper panel: Radio-HPLC

(177Lu γ-radiation detection); lower panel:

Ultraviolet-HPLC (254 nm absorption detection). (D) Specific

binding of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb in NUGC-4-CLDN18.2

cells. Left panel: Saturation binding curve plotted on a

logarithmic concentration scale for calculation of the equilibrium

dissociation constant (Kd). Right panel: Saturation binding curve

plotted on a linear concentration scale for determination of the

maximum binding capacity (Bmax). (E) Stability of

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb detected by thin-layer

chromatography in normal saline and 1640 (10% FBS). ADC,

antibody-drug conjugate; CLDN18.2, claudin 18.2; EC50,

half maximal effective concentration; FBS, fetal bovine serum;

HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; mAb, monoclonal

antibody; RDC, radionuclide-drug conjugate.](/article_images/or/55/1/or-55-01-09009-g00.jpg)

![(A) Positron emission

tomography-computed tomography images showing tumor-specific

accumulation of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb in

tumor-bearing mice over time, in contrast to that in other

non-target tissues. (B) Quantitative region of interest analysis of

the tumor, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and muscle in

tumor-bearing mice at 4, 24, 48, 96, 144 and 192 h after injection

of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-SYSA1801mAb. (C) Biodistribution results

at 4, 24, 48, 96 and 144 h after injection of

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb. (D) Tumor-to-blood, (E)

tumor-to-liver and (F) tumor-to-kidney ratios at 4, 24, 48, 96 and

144 h after injection of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-SYSA1801mAb.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences across

the different time points for each ratio were determined by one-way

analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple

comparisons. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. %DI/g,

percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue; mAb, monoclonal

antibody.](/article_images/or/55/1/or-55-01-09009-g01.jpg)