Esophageal cancer (EC), one of the major

malignancies of the digestive system, poses a pronounced global

health burden. According to the most recent global cancer

statistics, EC ranked as the 11th most commonly diagnosed cancer

and the 7th leading cause of cancer-related mortalities worldwide

in 2022 (1). Epidemiological data

indicate that ~511,000 new cases and 445,000 mortalities occurred

globally in that year, underscoring the substantial clinical and

public health challenges associated with this disease (1). Historically, EC is classified into two

main subtypes: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and

esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). ESCC is primarily associated with

lifestyle risk factors such as tobacco smoking and alcohol

consumption, while EAC is more commonly associated with

gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity (2). ESCC accounts for >90% of EC cases

worldwide (3). These subtypes

exhibit distinct molecular profiles: ESCC is characterized by

frequent increased expression of CCND1, SOX2 and/or TP63, whereas

EAC more often involves amplification of ERBB2, VEGFA and members

of the GATA gene family (GATA4/6) (4). Although the overall incidence of EC

has shown a downward trend, the prognosis remains poor (5). This is mainly due to the asymptomatic

nature of early-stage disease, the lack of specific diagnostic

biomarkers and the limitations of current detection methods. As a

result, the majority of patients are diagnosed at an advanced

stage, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of <20%

(6). The advent of immune

checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has ushered in a new era in EC

therapy, particularly monoclonal antibodies targeting programmed

cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1). These agents

have demonstrated promising efficacy across multiple malignancies,

including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell

carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and several types

of gastroesophageal cancer (7).

Clinical studies have shown that PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors markedly improve OS in advanced EC, with particularly

notable benefits in the ESCC subtype (8,9).

Currently approved or investigational anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents

include nivolumab, pembrolizumab, JS001, SHR-1210, durvalumab and

SHR-1316 (10). However, the

response rate to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade remains limited. Emerging

evidence indicates that immunosuppressive signaling within the

tumor microenvironment (TME) carries out a key role in limiting

efficacy, primarily by persistently impairing T cell function

through aberrant activation of inhibitory pathways (11). In fact, immunosuppression represents

the primary source of resistance to immunotherapy (12). To comprehensively decipher the

molecular landscape of tumors, researchers have extensively

integrated multi-dimensional data, including genomics,

transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, to deeply explore the

intricate interactions between tumor and immune cells within the

TME, thereby providing direction for personalized cancer

immunotherapy. In this context, combination therapies are widely

regarded as a key strategy to overcome resistance to immunotherapy.

Among them, unleashing the therapeutic potential of ICIs in

combination with targeted therapy, cytokines, metabolic

immunotherapies, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and multifunctional

nanoparticles has gained recognition (13). However, although a study has shown

that anti-PD-L1 inhibitors combined with radiotherapy can elicit

systemic antitumor immunity by remodeling the immune

microenvironment in mouse models of ESCC, the role of the spleen

and tumor-draining lymph nodes in radioimmunotherapy remains to be

elucidated. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, these studies

have not thoroughly analyzed the relationship between PD-1

expression and CD8+ T-cell function (14).

It is noteworthy that the complex composition of

different types of cancer and TMEs collectively shapes the

multidimensional mechanisms of immune regulation. Therefore,

determining the optimal combinations between immunotherapies and

TME-modulating agents remains a major challenge. The present review

aims to systematically dissect the complex immunosuppressive

network mechanisms in ESCC based on an in-depth analysis of its TME

and further discuss the translational potential of combination

immunotherapy in this setting.

Driven by breakthroughs in immunological theory, T

lymphocytes, as central effector cells, have been widely used in

tumor immunotherapy (15). PD-1 was

first discovered in 1992 and is functionally recognized as a key

molecule regulating both adaptive and innate immune responses

(16).

The PD-1 gene, PDCD1, is located on human chromosome

2q37 and encodes a 288 amino acid type I transmembrane glycoprotein

belonging to the CD28 immunoglobulin superfamily (16,17).

PD-1 is highly expressed on the surface of activated T cells and is

also dynamically distributed across various antigen presenting

cells (APCs), including B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs)

and monocytes. Its primary biological function is to negatively

regulate T cell effector activity, carrying out a key role in

maintaining immune homeostasis, preventing autoimmunity and

modulating anti-tumor immune responses (18,19).

PD-1 exerts its signaling through interaction with two specific

ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. PD-L1 is widely expressed on APCs,

activated lymphocytes and a variety of tumor cells, whereas PD-L2

expression is more restricted and is primarily observed on

activated DCs and macrophages (20). Notably, aberrant overexpression of

PD-L1 in the TME represents a major mechanism of immune evasion.

Its expression is directly regulated by abnormal activation of the

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) signaling

pathway and is positively associated with tumor node-metastasis

staging, lymphatic metastasis and poor prognosis (19). At the molecular level, PD-L1 binds

to PD-1 on T cells, effectively suppressing the proliferation of

PD-1+ immune cells, thereby dampening anti-tumor immunity and

facilitating tumor progression (21,22).

In normal tissues, PD-L1 displays tissue-specific

expression patterns, primarily localized on the surface of

CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs). By

inhibiting the phosphorylation cascade of the mTOR/AKT signaling

pathway, PD-L1 promotes Treg development, maintains their

homeostasis and supports their immunosuppressive functions

(23). During the malignant

transformation of esophageal tissues, PD-L1 expression undergoes

considerable reprogramming. From precancerous lesions such as

Barrett's esophagus and low-/high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia

to invasive gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, the PD-L1

positivity rate increases progressively (24). Among them, IFN-γ can directly induce

PD-L1 expression in esophageal epithelial cells via activation of

the JAK/STAT signaling axis, thereby establishing a molecular

barrier to immune surveillance (25,26).

Clinical data show that ~40% of patients with EC exhibit PD-L1

overexpression, and its expression level is positively associated

with disease progression. In cohorts treated with ICIs, the

objective response rate (ORR) in EC ranges from 9.9 to 33.3%,

further confirming the clinical value of PD-L1 as a therapeutic

target (27). Importantly, PD-L1

expression is negatively associated with both progression-free

survival (PFS) and OS in patients with EC, supporting its potential

as an independent prognostic biomarker (28). These findings define the dual role

of PD-L1 in EC: It acts both as a key driver of immune evasion and

as a predictive biomarker for immune therapy response. This dual

function provides a molecular basis for the development of

stratified treatment strategies.

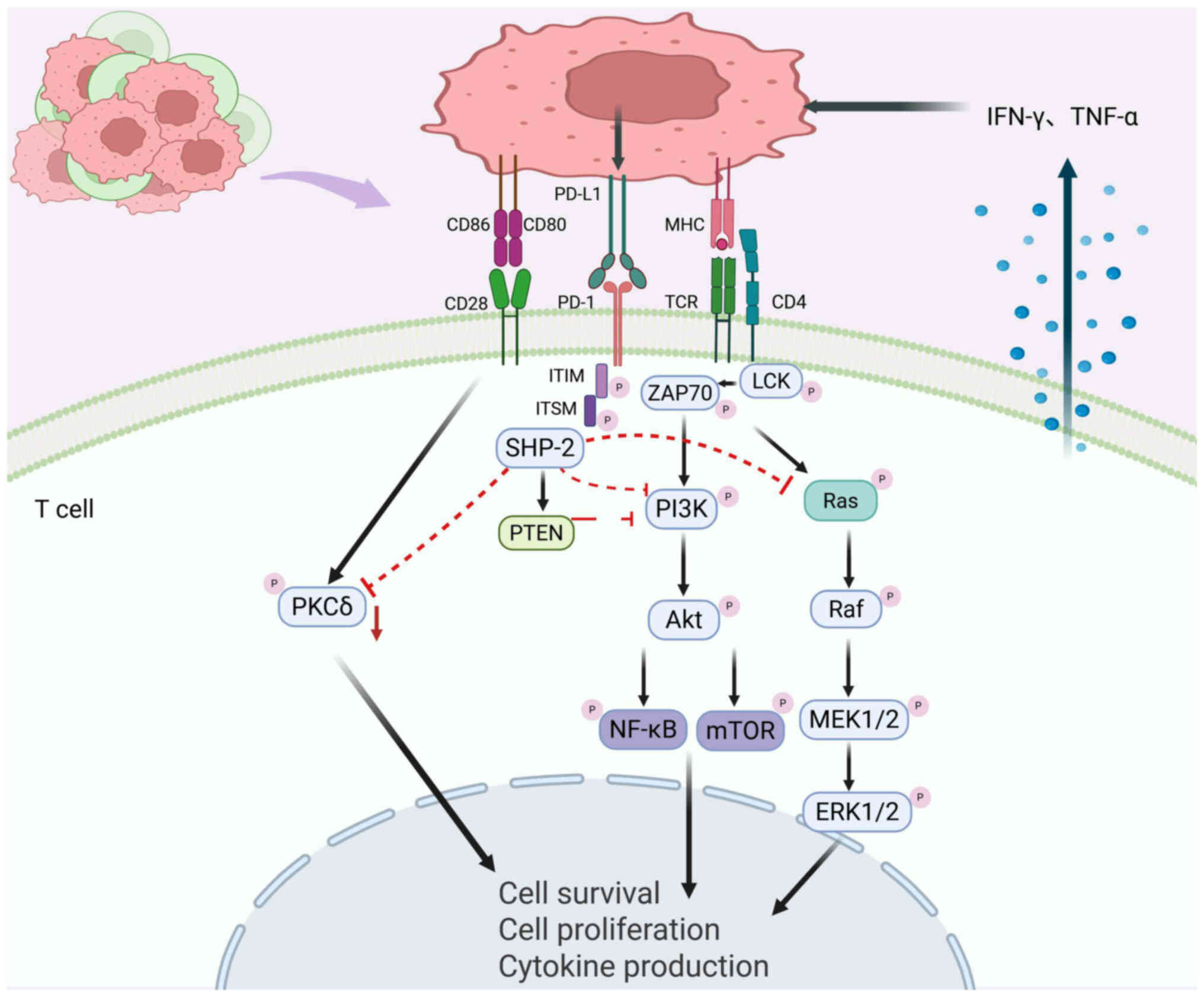

Evidence has confirmed that the PD-1/PD-L1 axis

mediates immunosuppressive effects by directly interfering with T

cell receptor (TCR) signaling. In the TME, PD-1 binding on

activated T cells to its PD-L1 ligand triggers phosphorylation of

tyrosine residues within the immunoreceptor tyrosine switch motif

(ITSM). This conformational change recruits SH2 domain tyrosine

phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 to ITSM. These phosphatases inhibit

the phosphorylation cascade of spleen tyrosine kinase and

phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), ultimately inhibiting PI3K/Akt

signaling. This results in downregulation of the anti-apoptotic

protein Bcl-xL, initiation of apoptosis in T lymphocytes and

suppression of T cell proliferation, survival and effector

function, thus establishing a key molecular basis for tumor immune

escape (21,29).

The immunosuppressive function of PD-1 is mediated

through multiple regulatory pathways: i) Inhibition of the

RAS-ERK1/2 signaling cascade blocks T cell cycle progression; ii)

downregulation of protein kinase C δ activity reduces the secretion

of cytokines such as IL-2, weakening the immune response; iii)

activation of PTEN inhibits TCR-induced PI3K/AKT signaling

(17). Additionally, inflammatory

cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α

(TNF-α) in the TME can markedly upregulate PD-L1 expression on

immune and stromal cells, creating a positive feedback loop that

reinforces immune suppression and enhances tumor immune evasion

(30) (Fig. 1). Unlike cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), which primarily

regulates early T cell activation in lymph nodes, PD-1 primarily

functions at later stages in peripheral tissues, where it inhibits

effector T cell activity through multifaceted mechanisms. This

spatial and temporal distinction suggests that the PD-1/PD-L1 axis

carries out a central role in the effector phase of tumor immune

escape (31).

T cell exhaustion serves as a key driver of immune

evasion in ESCC. Although PD-1 blockade can partially reverse the

dysfunctional state of exhausted T cells, this therapeutic effect

is generally transient and limited within the complex

immunosuppressive TME of ESCC (32). This persistent exhausted state is

reinforced by multiple mechanisms within the TME. For instance,

fibroblast-derived growth factor (FGF)-2 exacerbates T cell

exhaustion by upregulating Sprouty RTK signaling antagonist 1

(33). Concurrently, non-coding

RNAs carry out pivotal regulatory roles: The long non-coding RNA

FOXP4-AS1 stabilizes PD-L1 via the deubiquitinase

ubiquitin-specific protease (USP) 10, thereby suppressing

CD8+ T cell viability, promoting their exhaustion and

consequently driving immune evasion (34). Meanwhile, the circular RNA circNF1

upregulates PD-L1 expression through dual mechanisms, activating

the IL-6-induced JAK-STAT3 pathway and inhibiting USP7-mediated

deubiquitination of annexin A1, thereby enhancing PD-L1-mediated

immunosuppression (35). Beyond

direct regulation of T cells, their interactions with myeloid cells

are key. In patients with ESCC with stable disease,

PD-1+ CD8+ T cells frequently interact with

macrophages; targeting the iron-sulfur cluster assembly enzyme in

macrophages can repolarize them, enhance CD8+ T cell

cytotoxicity and synergize with anti-PD-1 therapy (36). Furthermore, melanoma-associated

antigen C3 amplifies IFN-γ signaling and upregulates PD-L1 by

binding to IFN-γ receptor 1 and enhancing its interaction with

STAT1, while also promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition,

ultimately leading to immune evasion (37).

Finally, the CD47-SIRPα axis, a key regulator of

innate immune surveillance, promotes immune evasion by delivering a

‘don't eat me’ signal that inhibits macrophage phagocytosis of

tumor cells. Elevated SIRPα expression is associated with poor

prognosis in patients with ESCC, potentially due to impaired

phagocytic function and subsequent suppression of antitumor

immunity (38–40). The PD-1/PD-L1 axis represents a core

mechanism of tumor immune evasion. Although PD-1 blockade can

partially reverse T cell exhaustion, its efficacy is often

constrained and prone to resistance within the multi-mechanistic,

multidimensional immunosuppressive microenvironment of ESCC.

Therefore, in-depth dissection of this regulatory network and the

subsequent development of rational combination targeting strategies

are key directions for overcoming immunotherapy resistance in

ESCC.

Beyond its well-known role in inhibiting anti-tumor

immunity by binding PD-1 to immune cells, tumor-intrinsic PD-L1

signaling also shapes tumor immunogenicity. Surface PD-L1 may

engage PD-1 on tumor cells themselves, promoting proliferation

through enhanced phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6. Cytosolic

PD-L1 regulates mRNA stability of DNA damage response (DDR) genes

and activates key pathways such as MAPK/ERK and STAT3 through

protein interactions. Nuclear PD-L1 may modulate transcription of

immunogenicity-related genes or influence chromosomal stability

through mechanisms such as sister chromatid cohesion (29).

Deficiencies in DDR are commonly observed in ESCC,

and DDR alterations may influence mutational processes and immune

cell infiltration (41). Increased

expression of DDR genes contributes to ESCC progression and

suppresses the tumor immune microenvironment, while targeting DDR

pathways has demonstrated potent efficacy in inducing immune

activation and improving patient outcomes (42). Moreover, a study investigating the

impact of DDR on the TME have confirmed that wild-type p53

overexpression suppresses DNA damage pathways and reduces PD-L1

expression in prostate cancer (43). Additionally, it has been suggested

that oxidative stress may induce DNA damage signaling that

upregulates PD-L1 expression. Both activation of DNA damage

signaling and DDR deficiencies carry out important roles in

promoting PD-L1 expression (44).

Notably, DNA damage can stimulate PD-L1 mRNA expression, leading to

increased PD-L1 levels on the cell surface. For example, DNA

double-strand breaks (DSBs) activate the STAT1/3-IRF1 signaling

axis, leading to PD-L1 upregulation (45). In addition, DSBs induced by

chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy may activate DDR. While excessive

DNA damage leads to tumor cell death, it also promotes the release

of damage-associated molecular patterns, which in turn elicit

anti-tumor immune responses. These observations highlight the

strong potential of targeting DDR pathways in cancer immunotherapy.

Combining DDR-targeted agents with ICIs represents a promising

therapeutic strategy. For example, colorectal cancer with mismatch

repair deficiency exhibit high sensitivity to anti-PD-1 checkpoint

blockade therapy (46). A subset of

patients with ESCC harbor DDR gene mutations. These patients with

DDR gene alterations show considerable associations with

immunological biomarkers, suggesting the potential feasibility of

combining DDR-targeting agents with immunotherapy for DDR-deficient

patients in future therapeutic strategies (47).

TME acts as a key mediator of the dynamic interplay

between tumor cells and host immune defense. Accumulating evidence

suggests that resistance to ICIs stems primarily from the intricate

crosstalk within the tumor-TME network (48). The following sections of the present

review aim to systematically explore the multifaceted regulatory

mechanisms of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in ESCC TMEs, with particular

attention to T and natural killer (NK) cell exhaustion,

immunosuppression, angiogenesis, tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS)

and tumor-driving mutations. This exploration holds promise for

identifying potential strategies to improve therapeutic outcomes in

EC.

The exhausted state in NK cells is characterized by

the loss of cytotoxic capacity and cytokine production (49). In patients with ESCC, PD-1

expression is markedly elevated on the surface of NK cells, and

this expression is negatively associated with patient prognosis

(50). Subsets of

PD-1+NK cells exhibit stronger functional activity than

PD-1−counterparts, suggesting that this subpopulation

may represent NK cells with the highest effector potential. This

observation helps explain why, despite PD-1 being expressed on only

a small proportion of NK cells, its interaction with PD-L1 on tumor

cells can still effectively suppress NK cell responses (51). Similar to regulatory mechanisms in T

cells, the PD-1/PD-L1 axis impairs NK cell activation thresholds,

proliferation capacity and cytokine secretion, ultimately leading

to an exhausted NK phenotype and weakened anti-tumor immune

surveillance (52).

Mechanistically, this inhibition is mediated primarily by blocking

the PI3K/AKT phosphorylation cascade (50).

In addition, T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM

domains (TIGIT) is often co-expressed with PD-1 on

tumor-infiltrating T and NK cells, forming a synergistic inhibitory

network. A study has confirmed that high TIGIT expression

associates with an exhausted state in tumor-infiltrating NK cells

(53). Experimental evidence

indicates that TIGIT promotes lymphocyte exhaustion through two

mechanisms: i) Inhibition of AKT pathway activation and ii)

inhibition of forkhead box protein O1 phosphorylation (54). Notably, blocking TIGIT can

effectively reverse exhaustion of NK cells within the TME and

restore their effector function (55). In a study based on peripheral

samples from surgically resected patients with ESCC, PD-1

expression revealed a notable positive association with TIGIT

levels (53). Correspondingly, an

ESCC clinical trial demonstrated that the combination of the

TIGIT-targeting antibody vibostolimab with pembrolizumab exhibited

encouraging clinical activity without requiring biomarker

prescreening; particularly, PD-L1 high-expressing patients, defined

by a combined positive score ≥10, achieved higher ORR (53). Both TIGIT and T cell immunoglobulin

and mucin domain-3 (Tim-3) are associated with poor survival

outcomes in ESCC (56). Similarly,

Tim-3, which is upregulated on NK cells across various types of

cancer, is a hallmark of lymphocyte exhaustion. In vitro

inhibition of Tim-3 not only enhances NK cell cytotoxicity but also

improves tumor cell killing efficiency (57). Research has confirmed that

functionally impaired Tim-3+ NK cells in EC associates

with poor patient prognosis, and the formation of this cellular

subset is mechanistically driven by TNF-α through NF-κB signaling

pathway-mediated TIM-3 expression (58). Multiple TIM-3-targeting

immunotherapeutic agents are currently undergoing phase 1/2

clinical trials, including Cobolimab, Sabatolimab, BGB-A425,

BC3402, TQB2618, NB002, AZD7789, LB1410 and INCAGN02390 (59). PD-1+NK cells in the TME

frequently exhibit a PD-1+/Tim-3+

double-positive depleted phenotype, suggesting potential

synergistic suppression (60).

Although substantial fundamental mechanistic

research supports TIM-3 as a key target for improving NK cell

function and enhancing cancer immunotherapy efficacy, with its

individual blockade or combination with PD-1 inhibitors considered

to hold considerable potential (59,61,62).

The field still contains debatable complexities worthy of deeper

investigation. This controversy is highlighted by an in

vitro study by Astaneh et al (49), which reached contrasting

conclusions. In early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia,

researchers found that pre-treatment of NK cells with anti-PD-1 and

anti-Tim-3 blocking antibodies failed to effectively restore or

enhance NK cell functional characteristics, while also not

promoting the production of key pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α

and IFN-γ. In summary, these studies reveal the complex

interactions among PD-1, TIM-3 and TIGIT in driving NK cell

dysfunction in ESCC. These findings not only elucidate the

multidimensional regulatory mechanisms of NK cell exhaustion but

also provide a theoretical foundation for developing PD-1 inhibitor

combination therapies with TIM-3 or TIGIT blockade, demonstrating

notable translational potential. However, the efficacy of

TIM-3/PD-1 co-targeting strategies should not be simplistically

generalized, as their effectiveness highly depends on specific

tumor types and disease stages. Future research should validate

this strategy in ESCC and other cancer types across different

disease stages, while further clarifying the intrinsic mechanisms

of treatment resistance.

In the ESCC microenvironment, PD-1 expression on NK

cells is dynamically regulated by various cytokines. Experimental

data show that IL-12 and IL-15 markedly upregulate PD-1 expression

in patient-derived NK cells in a time-dependent manner (50). Notably, TGF-β, a key inhibitory

cytokine for NK cells, promotes NK cell exhaustion by upregulating

the expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 on their surface

(63,64). Mechanistically, abnormal

accumulation of TGF-β in the TME results from the coordinated

secretion by multiple cell types: In addition to tumor

cell-autonomous secretion (65),

immunosuppressive subpopulations such as cancer-associated

fibroblasts (CAFs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs),

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and Tregs collectively form a

cascading TGF-β secretion network, shaping a hostile

microenvironment that promotes NK cell dysfunction (63,66). A

mechanistic study by Thangaraj et al (67) demonstrated that in tumor models with

high TGF-β expression, effective blockade of the TGF-β signaling

pathway is a prerequisite for restoring NK cell anti-tumor

activity. It is noteworthy that elevated TGF-β in the TME

contributes to cancer immune evasion. The PD-1 and TGF-β pathways

function independently yet interactively, collectively facilitating

immune escape by tumor cells. Co-blockade of TGF-β and PD-L1 has

been validated to enhance the efficacy of PD-L1 monoclonal

antibodies and overcome therapeutic resistance (68). Furthermore, bispecific

anti-PD-(L)1/TGF-β inhibitors can reinvigorate the effector

functions of CD8+ T and NK cells, hinder Treg expansion and

increase M1 macrophage density. Additionally, anti-PD-(L)1/TGF-β

inhibitor therapy can be safely administered in combination with

vaccination, radiotherapy and chemotherapy (69). Research by Lucarini et al

(70) demonstrated that low-dose

mitoxantrone combined with anti-TGF-β and PD-1 blockade therapy

enhances anti-tumor immunity by remodeling the tumor immune

landscape and overcoming the immunosuppressive microenvironment in

aggressive neuroblastoma.

These findings validate the central role of the

TGF-β-PD-1 regulatory axis in NK cell exhaustion and offer an

experimental basis for targeting the TME to restore immune

competence. They also offer theoretical guidance for exploring the

therapeutic potential of dual TGF-β and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in ESCC

immunotherapy.

Impaired metabolic functioning of NK cells is a

major factor contributing to their reduced activity, and the TME

carries out a key role in this process. The extensive consumption

of nutrients (such as glucose and glutamine) and the continuous

release of TGF-β in the TME inhibit NK cell glycolysis and

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), leading to

decreased functional activity (61,71).

Additionally, a study has confirmed that tumor cells in the TME can

secrete TGF-β, which further induces the upregulation of

fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase expression in NK cells, thereby

inhibiting glycolysis and ultimately impairing NK cell cytotoxicity

and vitality (72). Beyond the

reduced glucose concentration, other characteristic factors of the

TME also suppress NK cell function, such as hypoxia and acidic pH

(61). Research has shown that in

hypoxic prostate tumors, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α)

mediates the overexpression of miR-224, which suppresses NCR1

signaling, markedly reducing NK cell cytotoxicity (73). Moreover, elevated expression levels

of HIF-1α in patients with ESCC are associated with poor prognosis

(74). Based on this association,

HIF-1α could serve as a potential biomarker for predicting the

prognosis of ESCC (75).

Additionally, PD-L1 is not only expressed on tumor

cells in the TME but also on T cells and NK cells. HIF-1α, as a

response element of the PD-L1 promoter, can promote and sustain

PD-L1 expression, further enhancing its function through a positive

feedback mechanism (76). Research

by Ding et al (77)

demonstrated that in gliomas, hypoxia-induced overexpression of

HIF-1α promotes PD-L1 expression, confirming the positive

association between the two. In their study, the combination of

anti-PD-L1 antibody and HIF-1α inhibitors in a mouse glioma model

considerably increased the infiltration of immune cells (CD4+ T,

CD8+ T and CD11c+ DC) into the tumor while reducing PD-L1

expression, suggesting that this combination strategy could

effectively reverse the immunosuppressive microenvironment in

tumors. Furthermore, Shurin et al (78) suggested that HIF-1α inhibition has a

synergistic anti-tumor effect with anti-PD-1 therapy. In a mouse

melanoma model, inhibiting HIF-1α transcriptional activity led to

increased infiltration of NK cells and CTLs mediated by CCL2 and

CCL5, markedly enhancing the anti-tumor effect of PD-1 blockade

antibodies.

T cell exhaustion is a dynamic process characterized

by a gradual transition from stem-like self-renewal to terminal

exhaustion. Persistent expression of PD-1 inhibitory receptor on T

cells is a hallmark of exhaustion (79). As previously mentioned, one of the

key signaling pathways targeted by PD-1 is the TCR signaling

pathway. In exhausted T cells, the function of the TCR signaling

pathway is impaired (80).

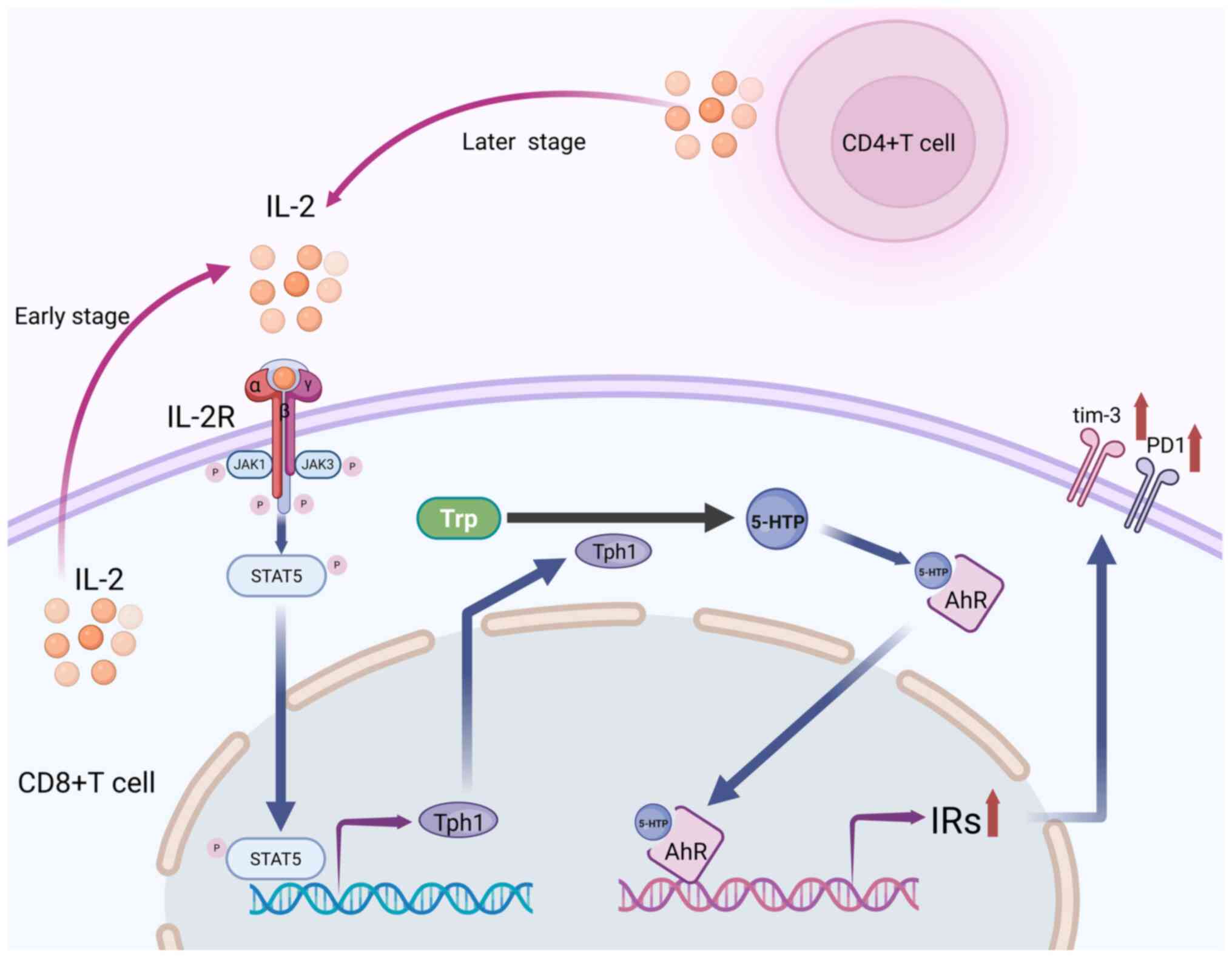

In ESCC TMEs, IL-2 levels are notably increased when

compared with normal tissues (81).

IL-2 promotes CD8+ T cell proliferation and its decline is one of

the key markers of T cell exhaustion. However, despite the decline

in IL-2 levels, IL-2 receptor β (IL-2Rβ) associated with PD-1

expression is upregulated in exhausted CD8+ T cells (79). In the early stages of tumor growth,

IL-2 induces CD8+ T cell differentiation through autocrine

signaling. In the mid to late stages of tumor growth, CD4+ T cells

continuously secrete IL-2, which further acts on CD8+ T cells. The

mechanism is that IL-2 continuously activates STAT5 in CD8+ T

cells, inducing the expression of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1),

which catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan

(5-HTP). The 5-HTP then activates AHR nuclear translocation,

leading to coordinated upregulation of inhibitory receptors such as

PD-1 and TIM-3, while inhibiting cytokine and effector molecule

production, ultimately leading to T cell exhaustion (82,83)

(Fig. 2). A study by Hashimoto

et al (84) showed that

PD-1+TCF-1+ CD8+ T cells (precursors of exhausted CD8+ T cells) are

not fate-locked to the exhausted path and their differentiation can

be regulated by IL-2 signaling. The researchers suggested that

PD-1+IL-2 combination therapy could markedly alter the

differentiation program of PD-1+TCF-1+ stem-like CD8+ T cells.

To address the clinical toxicity associated with

IL-2 therapy, antibody-cytokine fusion proteins such as PD1-IL2v

have been developed. These conjugates enhance the cytotoxic and

proliferative functions of stem-like precursor exhausted CD8+ T

cells (85). Accordingly, the

antibody-cytokine fusion protein eciskafusp alfa (PD1-IL2v) has

been engineered, wherein the PD-1 antibody delivers an IL-2R

agonist to PD-1-expressing T cells via a fused monomeric IL-2

variant (IL-2v), providing cis-binding that reportedly generates

superior effector populations (86). However, integrating both mechanisms

into a single molecule presents considerable challenges due to

competing requirements for PD-1 engagement and IL-2 receptor

signaling. Researchers including Mure et al (87) have developed a novel bispecific

antibody-cytokine fusion protein, ANV600, which delivers IL-2Rβγ

agonists specifically to PD-1+ cells while preserving the binding

site for PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. This approach provides a new

strategy with enhanced antitumor activity and reduced toxicity. By

targeting PD-1, ANV600 selectively expands tumor antigen-specific

CD8+ T cells, particularly progenitor exhausted (Tpex) and

cytotoxic exhausted subsets, while sparing Treg and NK cells.

Furthermore, ANV600 produces additive effects when combined with

either pembrolizumab or nivolumab.

In summary, T cell exhaustion represents a key

immunosuppressive phenomenon in the TME, particularly prominent

during the pathogenesis and progression of ESCC. PD1-IL2v molecules

such as ANV600 and AWT020, which modulate T cell status by

targeting PD-1, provide novel insights and strategic approaches for

ameliorating T cell exhaustion in ESCC, enhancing anti-tumor immune

responses and improving survival outcomes.

Exhausted T cells exhibit notable heterogeneity in

phenotype and function, mainly classified into two major subsets:

Tpex cells and terminally exhausted T cells. Tpex cells have a

stem-like exhaustion phenotype characterized by markers such as

PD-1, CD127, chemokine receptor CXCR5 and high levels of TCF-1

(encoded by Tcf7). Tpex cells rely primarily on mitochondrial fatty

acid oxidation and OXPHOS for metabolism. However, prolonged

antigen stimulation leads to changes in mitochondrial structure,

which in turn impairs both glycolysis and OXPHOS function (91). Furthermore, a reduction in mitophagy

or impaired OXPHOS can lead to the accumulation of reactive oxygen

species in mitochondria and increased accumulation of damaged

mitochondria, which causes the loss of mitochondrial membrane

potential and depolarization, ultimately leading to mitochondrial

dysfunction, increased hypoxic stress, induced epigenetic

reprogramming and irreversible terminal T cell exhaustion (92,93).

The PD-1/PD-L1 axis carries out a particularly key role in T cell

exhaustion, particularly in regulating mitochondrial function. The

PD-1 signaling pathway inhibits phosphorylation of dynamin-related

protein 1 by modulating extracellular protein kinases 1/2 and mTOR

pathways, blocking mTOR-mediated mitochondrial fission, thereby

reducing mitochondrial numbers and weakening their function. This

process ultimately suppresses T cell activation, proliferation and

infiltration (94). Current

research indicates that immune-related pathways and mitochondrial

function are associated with immunotherapy sensitivity in ESCC

(95). To overcome the

immunosuppressive TME, characterized by hypoxia and lipid raft

formation, which considerably suppress T cell infiltration and

function, Chen et al (96)

developed a stable nano-formulation named Abstatin. This

formulation combines partially denatured albumin with fluvastatin,

effectively mitigating mitochondrial respiratory suppression and

disrupting lipid raft stability in non-small cell lung cancer

cellular and animal models. Notably, Abstatin notably enhanced the

efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy with minimal toxicity, demonstrating

promising clinical safety prospects. This approach, which

integrates cellular metabolic regulation with immune sensitization,

broadens the potential applications of immunotherapy and offers

novel insights for ESCC treatment. Similarly, in manganese-based

STING-activating cancer immunotherapy, efficacy is limited by T

cell exhaustion, with mitochondrial dysfunction being a key

contributing factor. A study shows that spermidine can enhance

mitochondrial function in T cells, thereby providing a viable

strategy to reverse T cell exhaustion in manganese-based

immunotherapy (97). Additionally,

supplementation with nicotinamide riboside has been shown to

improve T cell mitochondrial function, consequently enhancing their

responsiveness to PD-1 inhibitors (98). Recent evidence further emphasizes

mitochondria as key hubs for enhancing anti-tumor immune responses

in ‘immune desert’ tumors (99).

For instance, targeted induction of mitochondrial DNA release can

activate the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes

(STING) pathway, thereby sensitizing tumors to ICI therapy

(100). This opens new

perspectives for enhancing tumor immunogenicity in ESCC.

In addition, various amino acids regulate the

PD-1/PD-L1 signaling axis through different mechanisms. For

example, glutamine is abundant in EC cells and other tumor cells,

glutamine deficiency lowers intracellular glutathione levels in

tumor cells, thereby upregulating PD-L1 expression to suppress T

cells. Additionally, glutamine depletion irreversibly inhibits T

cell proliferation and cytokine secretion, creating a dual

inhibitory effect (101,102). In tryptophan metabolism, IDO+ DCs

activate Tregs, upregulate PD-L1 on DCs and enhance immune

suppression. Multiple amino acid deficiencies inhibit mTOR/Akt

signaling, activate the FOXO-PD-1 pathway in Tregs and form a

PD-1-PTEN-PI3K/Akt negative feedback loop, further reinforcing the

immune suppression state (101).

Serum metabolomic analyses indicate that elevated serum

L-tryptophan levels are associated with reduced risk of ESCC

(103). Dysregulated tryptophan

metabolism conversely promotes progression and metastasis (103). While metabolism carries out a

pivotal role in tumorigenesis and cancer progression, the

regulatory mechanisms of tryptophan metabolism within the EC

microenvironment remain largely unknown. Finally, from the emerging

perspective of metabolic intervention and immune sensitization,

serine metabolism reveals another mechanism. Serine occupies a

central position in maintaining metabolic homeostasis of cancer

cells. Research by Saha et al (104) confirmed that restricting both

endogenous and exogenous serine supply in colorectal cancer cells

induces mitochondrial dysfunction, which unexpectedly enhances

tumor sensitivity to PD-1 ICIs. This discovery not only reveals a

novel immune mechanism underlying the anti-tumor effects of serine

deprivation but also demonstrates the pronounced potential of

targeting amino acid metabolism to reverse immunotherapy

resistance. It outlines a blueprint for transitioning ESCC

treatment from ‘immune monotherapy’ to ‘multidimensional

immune-metabolic combination therapy’. Future clinical

breakthroughs in ESCC will likely emerge from combination therapies

designed against its specific metabolic vulnerabilities. By

precisely intervening in the ‘metabolic battle’ within the TME, the

full anti-tumor potential of the immune system can be unveiled and

improve patient survival outcomes.

In the TME, Treg cells, MDSCs, TAMs-M2 type,

neutrophils and CAFs cooperate to promote immune suppression

through cytokine networks (105).

In ESCC, Treg cells are central to the TME, maintaining immune

homeostasis while exerting immune suppressive effects (106). Tregs suppress immune cell function

through the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines, such as

IL-10, IL-35 and TGF-β, and through direct cell-to-cell contact

(107). The PD-1/PD-L1 signaling

axis carries out a key role in regulating Treg differentiation and

function, specifically by reducing STAT activation in Th1 cells

through SHP-1/2 phosphatases, promoting Th1 cell to Treg

conversion. In addition, Tregs may affect the efficacy of

PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy (108). Additionally, the expression of

PD-1 can suppress the immunosuppressive capacity of Tregs and

promote the production of IFN-γ. Conversely, PD-L1, promotes the

conversion of naïve CD4+ T cells to Tregs by downregulating Akt,

mTOR and ERK2, and upregulating PTEN (108).

Among these secreted proteins, TGF-β can impair the

cytotoxicity of effector T cells or NK cells, while upregulating

immune checkpoints on regulatory immune cells (such as TAMs and

MDSCs) and Tregs (109). TGF-β not

only stimulates Treg differentiation and expansion but also

converts normal T cells into Tregs (107,110). Notably, blocking MDSC-derived

TGF-β can enhance the efficacy of PD-L1/PD-1 inhibition therapy and

induce an immune response from MAGE-A3+ specific CD8+ T cells in

ESCC. Therefore, combining T cell-based therapies with dual

blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 and TGF-β signaling pathways may be a

promising cancer treatment strategy (111).

As another important immunosuppressive secretory

factor in TME, IL-6 is overexpressed in both ESCC and EAC, and its

levels associate positively with disease progression. IL-6 carries

out a key role in ESCC by upregulating PD-L1 expression (112). IL-6 inhibits DC function in

antigen presentation by activating STAT3, thereby inhibiting tumor

immune response (113). In

addition, other cytokines carry out a key role in T cell

exhaustion. For example, IL-6 recruits MDSCs in the TME, which

inhibit T cell activity via IFN-γ and promote partial CD8+ T cell

exhaustion. IL-6 released by MDSCs also interacts with IL-6/STAT1

and is associated with multidrug resistance (114). In addition, activated fibroblasts

secrete IL-6, which further promotes ESCC cell proliferation and

enhances cisplatin resistance (115). The mechanism involves IL-6

secreted by CAFs upregulating the expression of CXCR7 via the

STAT3/NF-κB pathway, thereby promoting chemotherapy resistance

(116). More importantly, IL-6

expression was positively associated with PD-L1 expression levels.

Metformin downregulates PD-L1 expression by inhibiting the

IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in ESCC, thereby enhancing

antitumor immune responses (117).

Furthermore, radiation therapy considerably upregulates PD-L1

expression levels via the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway, suggesting

that combining anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy with radiation therapy

may improve the treatment outcomes (118). Based on clinical and experimental

evidence, drugs targeting IL-6 signaling provide a reasonable

theoretical basis for combination therapy of patients with patients

with ICIs (119). As a

tumor-derived and systemic immune checkpoint, IL-6 can evade the

killing effects of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells activated by ICI

therapy through tumor hijacking mechanisms. Therefore, combining

IL-6 signaling pathway inhibitors with ICIs is well supported by

clinical evidence (120).

In ESCC, IL-6 carries out a particularly prominent

role: It not only serves as a pivotal factor shaping the

immunosuppressive microenvironment but also possesses clear

clinical predictive value. Specifically, IL-6 overexpression may

serve as a potential biomarker for predicting response to PD-1

inhibitors (121); concurrently,

elevated serum IL-6 levels markedly associate with increased risk

of immune-related adverse events and poor overall patient prognosis

(122). These findings

collectively establish the key position of IL-6 in ESCC

immunotherapy and provide further rationale for the clinical

application of combination blockade strategies in this patient

population.

In the TME, various innate immune cells participate

in angiogenesis regulation through multiple molecular mechanisms.

Macrophages, N2-type neutrophils, MDSCs and masT cells not only

directly promote the formation of new blood vessels by secreting

VEGF, but also mediate the release of VEGF-A through the secretion

of MMP-9. Additionally, MDSCs produce FGF-2 and Bv8 molecules,

which, together with FGF-2, IL-8, TGF-β and TNF-α secreted by masT

cells, form a complex pro-angiogenesis signaling regulatory network

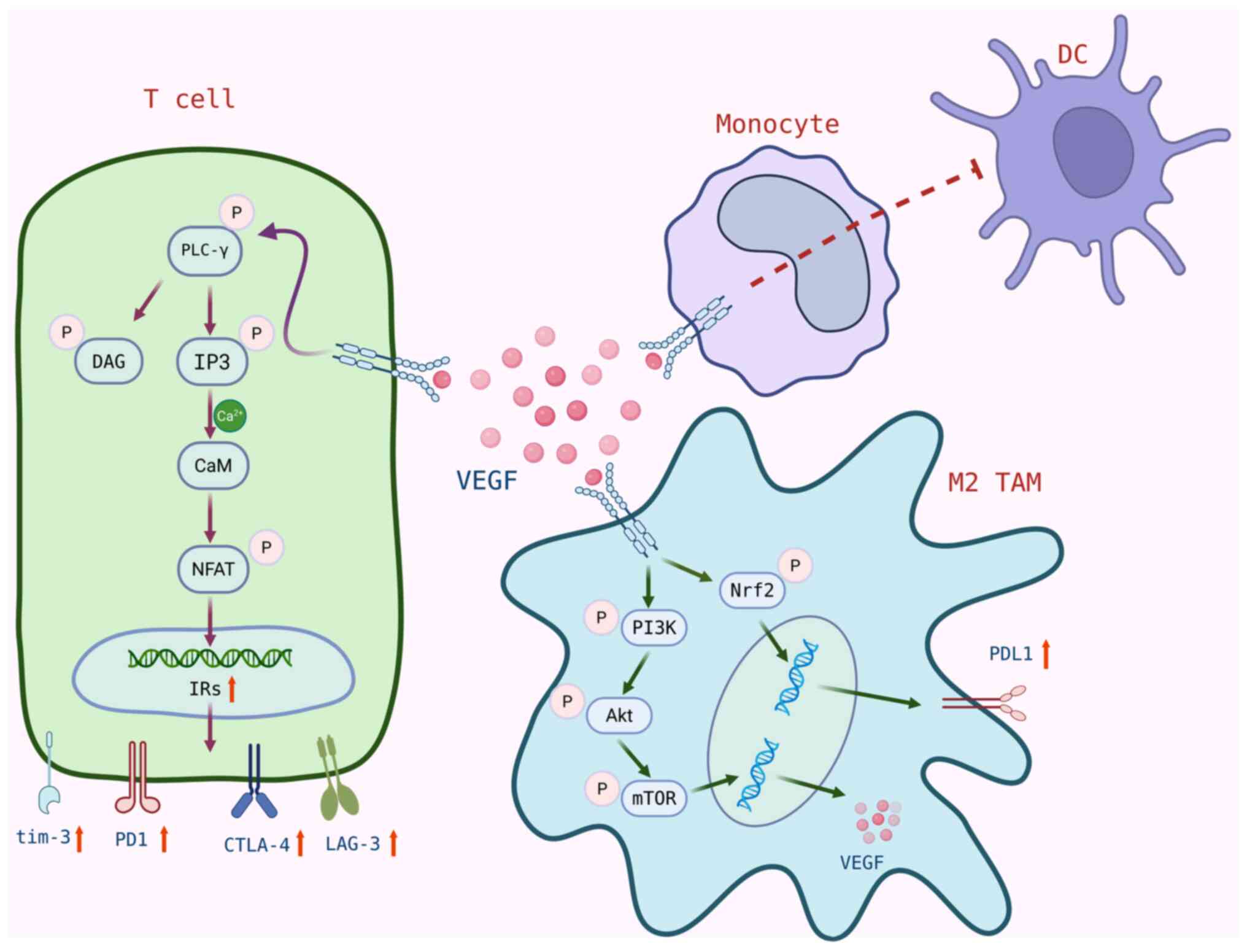

that carries out a key role in the TME (126). In turn, VEGF can inhibit the

maturation, differentiation and antigen presenting abilities of

professional APCs, such as DCs, NK cells and T cells, while

enhancing the immunosuppressive functions of Treg cells, TAMs and

MDSCs (48). Notably, VEGF

inhibition has been shown to increase the number of

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (127). In addition, other mediators of

angiogenesis, such as platelet-derived growth factor and FGF

signaling pathways, also carry out roles in regulating

angiogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis. Therefore, when VEGF

signaling is blocked, compensatory mechanisms may come into play,

suggesting that anti-angiogenesis therapy needs to block not only

VEGF/VEGFR signaling pathways but also other key pathways involved

in angiogenesis and tumor growth (128).

Most importantly, VEGF expression shows notable

association with EC progression and prognosis, and contributes to

improved survival outcomes in advanced ESCC and EAC (129). VEGF increases the expression of

PD-1 and other immune checkpoints (such as CTLA-4, tim-3 and Lag-3)

on CD8+ T cells via the VEGFR-2-PLCγ-calmodulin

phosphatase-activated T cell nuclear factor NFAT pathway, thereby

promoting CD8+ T cell exhaustion and facilitating tumor immune

evasion (130,131). Additionally, high expression of

VEGFR-2 is considered a poor prognostic factor in patients with

ESCC, with activation of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway carrying

out a key role in the tumorigenesis, progression and prognosis of

ESCC cells (132). Upon activation

of VEGFR-2 on M2-type TAMs, VEGF secretion is induced via the

Akt/mTOR/PI3K pathway and PD-L1 expression is upregulated by

activation of Nrf2 (133). The

binding of VEGF/VEGFR2 also inhibits the differentiation of

monocytes into DCs and reduces DC maturation and antigen-presenting

function through inhibition of the NF-κB-mediated pathway, driving

immune evasion and promoting PD-L1 expression on DCs (134). Studies have shown that blocking

PD-L1 can reactivate DC function and enhance anticancer T cell

immune responses (135) (Fig. 3). These findings demonstrate that

anti-angiogenic agents can effectively enhance tumor

immunogenicity, thereby improving responses to immunotherapy. Zhang

et al (PMID: 31704735) reported that VEGF-A induces the

expression of the transcription factor TOX in T cells, driving

specific exhaustion transcription programs within T cells. Through

combined in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo mouse

experiments, they demonstrated that a combination of PD-1 and

VEGF-A blockade could restore the anti-tumor function of T cells

(136).

Substantial clinical investigations have been

conducted in this area. For instance, Hou et al in a

retrospective propensity-matched cohort study of 135 patients with

metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma, found that anti-PD1

therapy following anti-angiogenic treatment considerably improved

OS and PFS (137). In a separate

study, Lochrin et al (138)

retrospectively analyzed the clinical characteristics, treatment

and outcomes of patients with mucosal melanoma treated with Axtinib

(a selective VEGF inhibitor) with or without anti-PD-1 therapy at a

single US referral center between 2018 and 2021. They found that

78% of patients received Axtinib combined with PD-1 inhibitors,

with a median treatment duration of 3.2 months. The overall

response rate was 13%, disease control rate was 26%, median PFS was

3.2 months and median OS was 8.2 months. Overall, this regimen was

well-tolerated. Additionally, a phase II study demonstrated that

neoadjuvant toripalimab combined with Axtinib shows promise in

reducing inferior vena cava tumor thrombus staging and decreasing

the need for extensive surgery in patients with clear cell renal

cell carcinoma and inferior vena cava tumor thrombus, while also

establishing the safety profile of this combination therapy

(139). Furthermore, Atkins et

al (140) conducted a

non-randomized phase 1b clinical trial in treatment-naive patients

with advanced renal cell carcinoma, showing that the combination of

Axtinib (a selective VEGF inhibitor) and pembrolizumab (an

anti-PD-1 therapy) was safe, well-tolerated and exhibited some

anti-tumor activity. However, trials of this scale are insufficient

to demonstrate substantial clinical benefit, and further validation

in larger trials may be required. Notably, a previous case analysis

reported a patient with ESCC who experienced disease recurrence

after chemoradiotherapy and achieved a durable complete remission

confirmed by PET/CT evaluation following treatment with the PD-1

inhibitor camrelizumab combined with the anti-angiogenic agent

apatinib, with manageable treatment-related toxicity (141). However, a study in other cancer

types such as metastatic renal cell carcinoma, such as the

combination of lenvatinib with pembrolizumab compared with

sunitinib, did not show notable improvement in OS (137). These results suggest that the

clinical efficacy of combining immunotherapy with anti-angiogenic

strategies may be heterogeneous across different tumor types, drug

combinations and patient populations. Additionally, both

anti-angiogenic drugs and ICIs have their own side effect profiles,

and adverse events become more complex with combination therapy

(142). The synergistic mechanisms

between ICIs and anti-angiogenic agents have not been fully

elucidated, and identifying potential beneficiary populations for

ICI combined with anti-angiogenic therapy in ESCC and other types

of cancer remains a key clinical challenge.

TLS have a positive prognostic value in the majority

of solid tumors, carrying out a important role in creating a

microenvironment with a unique cytokine profile (143). TLS is characterized by its

temporary formation at tumor sites, rather than in secondary

lymphoid organs, and these ectopic lymphoid tissues consist mainly

of follicular DCs, B cell zones, T cell zones and high endothelial

venules (144). TLS formation

begins with the release of CXCL13 and IL-7 by stromal cells

(143). Deguchi et al

(144) showed that high TLS

presence was associated with improved prognosis in patients with

early-stage ESCC, but no notable difference was observed in

advanced cases at stage III or higher. This may be due to the

increased presence of Treg cells and M2 macrophages, which exert

immunosuppressive functions in the vicinity of TLS or locally

within the tumor. In addition, studies have found that in ESCC

immunotherapy, the maturity of TLS is markedly associated with

improved prognosis, with mature TLS (MTLS) being an independent

prognostic factor for ESCC (145,146). MTLS contribute to improved

treatment outcomes in patents with ESCC who undergo various

neoadjuvant therapies, and T cells reactivated by PD-1 inhibitors

within TLS may promote TLS maturation through interactions and

activation with B cells. As TLS matures, both humoral and adaptive

anti-tumor immune responses are effectively activated. MTLS

accelerates the spread of T cells from TLS to tumor sites,

enhancing tumor cell elimination (146).

In gastric cancer, the presence of tissue-resident

memory T (Trm) cells or TLS is associated with a favorable

prognosis (147). Hu et al

(148) demonstrated that activated

B cells enhanced the secretion of CXCL13 and granzyme B by

CD103+CD8+ Trm cells. Furthermore, the presence of TLS and

CXCL13+CD103+CD8+ Trm cells was associated with a tumor necrosis

factor receptor 2-dependent effective response to PD-1 inhibitor

treatment and CD103+CD8+Trm cells in the high TLS group showed

markedly increased PD-1 expression levels. Additionally, Zhang

et al (149) identified the

presence of HLA-A+ TLS through multiplex immunohistochemistry and

showed that as TLS matured, the resident cells within TLS gradually

expressed HLA-A. Spatially distinct tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte

(TIL)-T cells and single-cell RNA-sequencing data from 60 ESCC

tumor tissues showed through digital spatial analysis that as TLS

matured, CXCL13-expressing exhausted TIL-T cells within TLS were

reactivated and features of antigen-presenting machinery were

upregulated. Further experiments by Zhang et al (149) confirmed the presence of HLA-A+ TLS

in ESCC tumor tissues and HLA-A+ TLS, along with their major cell

components, TIL-Ts and TIL-Bs, were associated with clinical

benefits from ICI treatment in ESCC. These observations suggest

that integrating tumor mutational burden (TMB) with PD-L1

expression, TLS maturity and other multidimensional parameters may

improve ESCC patient stratification and therapeutic

decision-making. This implies that combining ICIs with agents

targeting these inhibitory cells could potentially alleviate

microenvironmental suppression and restore or enhance the

anti-tumor function of TLS, thereby offering promising prospects

for improving treatment outcomes in patients with advanced

ESCC.

TMB, as a biomarker for predicting responses to

anti-PD-1 therapy, represents the total number of mutations in all

coding regions of the tumor genome (150). Multiple studies have shown that

TMB is relatively high in locally advanced or metastatic ESCC and

that TMB is markedly associated with ORR and OS (151,152). Immunologically ‘hot’ tumors

typically exhibit (TMB-H) (TMB-H), which implies a higher load of

neoantigens and upregulation of PD-L1 expression, thereby promoting

increased TILs (153). For

example, in cancer types such as melanoma and colorectal cancer,

CD8+ TIL-T cell levels are positively associated with neoantigen

load and tumors with TMB-H are more responsive to immune checkpoint

blockade (ICB) (154). TMB-H can

optimize the spatial distribution of T cells by promoting APCs to

present neoantigens, thereby activating T cells and enhancing their

infiltration into the TME. As such, TMB was initially proposed as a

predictive biomarker for ICB responses (155,156).

However, subsequent research has shown that TMB-H is

not universally applicable to all solid tumors, including some

cases of ESCC, and its predictive value is limited. This

inconsistency can be attributed to notable differences in immune

cell infiltration density and immune activity between low-TMB and

high-TMB subtypes in these types of cancer (155,157). Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT)

can reduce TMB and induce non-specific inflammation in ESCC cells.

When ICIs are administered before or in combination with CCRT, they

may initiate and reactivate immune cells, triggering a more robust

immune response (158).

PD-1/PD-L1 ICIs have brought transformative

advances in the treatment of EC, yet their limited efficacy

highlights the need for a deeper understanding of complex

regulatory networks within the TME. The central role of the

PD-1/PD-L1 axis in mediating immune evasion in the EC has been

elucidated, conversely, PD-L1 impairs T cell function by promoting

exhaustion and apoptosis through TCR signaling; on the other hand,

the synergistic reinforcement of multiple mechanisms within the TME

leads to persistent immune evasion in ESCC, collectively resulting

in limited response rates and frequent resistance to PD-1/PD-L1

monotherapy. The TME in ESCC exhibits high heterogeneity and

multidimensional immunosuppressive characteristics, comprising

various immune cells (such as Tregs, MDSCs and TAMs) and their

secreted factors (such as TGF-β and IL-6), non-coding RNAs (such as

FOXP4-AS1 and circNF1), metabolic reprogramming (such as amino acid

metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction), innate immune

checkpoints (such as CD47-SIRPα), angiogenic factors (such as VEGF)

and the maturation status of TLS. These multifaceted

immunosuppressive components interact and function synergistically,

forming an intricate immunosuppressive network that ultimately

undermines the therapeutic efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 single-agent

targeting. Given the heterogeneity and complexity of the TME,

single ICB is unlikely to achieve curative outcomes. Future

research should focus on systematically characterizing the dynamic

regulatory networks within the TME. Rapid translation of these

fundamental discoveries into clinical benefits is key,

necessitating the promotion of more prospective clinical trials

exploring novel combination therapies and utilizing advanced models

such as patient-derived organoids for preclinical efficacy

evaluation. This includes exploring intelligent combinations of

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with other targeted agents, such as

co-targeting additional immune checkpoints in the TME (such as

TIGIT and TIM-3), antagonizing key immunosuppressive factors (such

as TGF-β and IL-6), synergizing with anti-angiogenic drugs and

leveraging DDR pathway-targeting agents to enhance tumor

immunogenicity. Concurrently, developing targeted drug delivery

systems for specific TME components, employing IL-2 signaling to

regulate the differentiation of stem-like exhausted T cells and

creating novel PD1-IL2v fusion proteins (such as nanoformulations),

along with in-depth investigation of resistance mechanisms in

combination therapies and integration of multi-omics data with

clinical variables to build personalized immunotherapy decision

models, hold promise for gradually dismantling the immune defense

network of ESCC and offering patients more durable and effective

treatment options.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou

Province [grant no. Qiankeheji-zk(2025) General Program 412].

Not applicable.

HL contributed to conceptualization, project

administration, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing.

LQ contributed to investigation, supervision, writing-review and

editing. ZLin contributed to investigation, writing-review and

editing. ZLi contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition,

supervision, writing-review and editing. Data authentication not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Li N and Sohal D: Current state of the

art: Immunotherapy in esophageal cancer and gastroesophageal

junction cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 72:3939–3952. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lu S, Li K, Wang K, Liu G, Han Y, Peng L,

Chen L and Leng X: Global trends of esophageal cancer among

individuals over 60 years: An epidemiological analysis from 1990 to

2050 based on the global burden of disease study 1990–2021. Oncol

Rev. 19:16160802025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network;

Analysis Working Group; Asan University; BC Cancer Agency; Brigham

and Women's Hospital; Broad Institute; Brown University; Case

Western Reserve University; Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Duke

University; Greater Poland Cancer Centre, et al, . Integrated

genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature.

541:1692017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cao Z, Wang H, Li Y, Ye S, Lin J, Li T,

Leng J, Jiang Y, Bie M and Li L: The global burden and trends of

esophageal cancer caused by smoking among men from 1990 to 2021 and

projections to 2040: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease

2021. Eur J Med Res. 30:10432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li J, Xu J, Zheng Y, Gao Y, He S, Li H,

Zou K, Li N, Tian J, Chen W and He J: Esophageal cancer:

Epidemiology, risk factors and screening. Chin J Cancer Res.

33:535–547. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Havel JJ, Chowell D and Chan TA: The

evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor

immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 19:133–150. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Liu W, Huo G and Chen P: Efficacy of

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in advanced gastroesophageal cancer based on

characteristics: A meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 15:751–771. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Beshr MS, Shembesh RH, Salama AH, Chenfouh

I, Alfaqaih SM, Khashan A, Kara AO, Abuajamieh M, Basheer E, Ansaf

ZA, et al: PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in advanced, unresectable

esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma: A meta-analysis of their

effects across patient subgroups. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

215:1048762025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jiao R, Luo H, Xu W and Ge H: Immune

checkpoint inhibitors in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma:

Progress and opportunities. Onco Targets Ther. 12:6023–6032. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Thommen DS and Schumacher TN: T cell

dysfunction in cancer. Cancer Cell. 33:547–562. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang X, He J, Ding G, Tang Y and Wang Q:

Overcoming resistance to PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade mechanisms and

therapeutic strategies. Front Immunol. 16:16886992025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mandal K, Barik GK and Santra MK:

Overcoming resistance to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy: Mechanisms,

combination strategies, and future directions. Molecular Cancer.

24:2462025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yin Z, Zhang H, Zhang K, Yue J, Tang R,

Wang Y, Deng Q and Yu Q: Impacts of combining PD-L1 inhibitor and

radiotherapy on the tumour immune microenvironment in a mouse model

of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 25:4742025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Oh DY, Fong L, Newell EW, Turk MJ, Chi H,

Chang HY, Satpathy AT, Fairfax B, Silva-Santos B and Lantz O:

Toward a better understanding of T cells in cancer. Cancer Cell.

39:1549–1552. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kaushik I, Ramachandran S, Zabel C,

Gaikwad S and Srivastava SK: The evolutionary legacy of immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:491–498. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jiang X, Wang J, Deng X, Xiong F, Ge J,

Xiang B, Wu X, Ma J, Zhou M, Li X, et al: Role of the tumor

microenvironment in PD-L1/PD-1-mediated tumor immune escape. Mol

Cancer. 18:102019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bagchi S, Yuan R and Engleman EG: Immune

checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: Clinical impact

and mechanisms of response and resistance. Annu Rev Pathol Mech

Dis. 16:223–249. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang X, Yang Y, Zhao H, Tian Z, Cao Q, Li

Y, Gu Y, Song Q, Hu X, Jin M and Jiang X: Correlation of PD-L1

expression with CD8+ T cells and oxidative stress-related molecules

NRF2 and NQO1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol Clin

Res. 10:e123902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mei Z, Huang J, Qiao B and Lam AK: Immune

checkpoint pathways in immunotherapy for head and neck squamous

cell carcinoma. Int J Oral Sci. 12:162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jiang Y, Chen M, Nie H and Yuan Y: PD-1

and PD-L1 in cancer immunotherapy: Clinical implications and future

considerations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 15:11112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu J, Chen Z, Li Y, Zhao W, Wu J and

Zhang Z: PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in tumor immunotherapy.

Front Pharmacol. 12:7317982021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang X, Teng F, Kong L and Yu J: PD-L1

expression in human cancers and its association with clinical

outcomes. Onco Targets Ther. 9:5023–5039. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Saller JJ, Mora LB, Nasir A, Mayer Z,

Shahid M and Coppola D: Expression of DNA Mismatch repair proteins,

PD1 and PDL1 in Barrett's neoplasia. Cancer Genomics Proteomics.

19:145–150. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Karstens KF, Kempski J, Giannou AD,

Pelczar P, Steglich B, Steurer S, Freiwald E, Woestemeier A,

Konczalla L, Tachezy M, et al: Anti-inflammatory microenvironment

of esophageal adenocarcinomas negatively impacts survival. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 69:1043–1056. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mimura K, Teh JL, Okayama H, Shiraishi K,

Kua LF, Koh V, Smoot DT, Ashktorab H, Oike T, Suzuki Y, et al:

PD-L1 expression is mainly regulated by interferon gamma associated

with JAK-STAT pathway in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 109:43–53.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Xu J, Yin Z, Yang L, Wu F, Fan J, Huang Q,

Jin Y and Yang G: Evidence that dysplasia related microRNAs in

Barrett's esophagus target PD-L1 expression and contribute to the

development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Aging (Albany NY).

12:17062–17078. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Baba Y, Nomoto D, Okadome K, Ishimoto T,

Iwatsuki M, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N and Baba H: Tumor immune

microenvironment and immune checkpoint inhibitors in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 111:3132–3141. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kornepati AVR, Vadlamudi RK and Curiel TJ:

Programmed death ligand 1 signals in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer.

22:174–189. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ohaegbulam KC, Assal A, Lazar-Molnar E,

Yao Y and Zang X: Human cancer immunotherapy with antibodies to the

PD-1 and PD-L1 pathway. Trends Mol Med. 21:24–33. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Buchbinder EI and Desai A: CTLA-4 and PD-1

pathways: Similarities, differences, and implications of their

inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol. 39:98–106. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang Z, Zhang RY, Xu YF, Yue BT, Zhang JY

and Wang F: Unmasking immune checkpoint resistance in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma: Insights into the tumor microenvironment

and biomarker landscape. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 17:1094892025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chen QY, Li YN, Wang XY, Zhang X, Hu Y, Li

L, Suo DQ, Ni K, Li Z, Zhan JR, et al: Tumor Fibroblast-Derived

FGF2 regulates expression of SPRY1 in esophageal Tumor-infiltrating

T cells and plays a role in T-cell exhaustion. Cancer Res.

80:5583–5596. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Shen GY, Zhang Y, Huang RZ, Huang ZY, Yang

LY, Chen DZ and Yang SB: FOXP4-AS1 promotes CD8+ T cell exhaustion

and esophageal cancer immune escape through USP10-stabilized PD-L1.

Immunol Res. 72:766–775. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang C, Ju C, Du D, Zhu P, Yin J, Jia J,

Wang X, Xu X, Zhao L, Wan J, et al: CircNF1 modulates the

progression and immune evasion of esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma through dual regulation of PD-L1. Cell Mol Biol Lett.

30:372025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Luo J, Zhang X, Liang Z, Zhuang W, Jiang

M, Ma M, Peng S, Huang S, Qiao G, Chen Q, et al: ISCU-p53 axis

orchestrates macrophage polarization to dictate immunotherapy

response in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis.

16:4622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu Q, Zhang W, Wang Y, Min Q, Zhang H,

Dong D and Zhan Q: MAGE-C3 promotes cancer metastasis by inducing

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and immunosuppression in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Commun (Lond).

41:1354–1372. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li J, Ozawa Y, Mozumi T, Jiang K, Taniyama

Y, Sato C, Okamoto H, Ishida H, Ujiie N, Ohnuma S, et al:

Expression of cluster of differentiation 47 (CD47) and signal

regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) as prognostic biomarkers and

potentially therapeutic targets in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma. Esophagus. Sep 10–2025.doi: 10.1007/s10388-025-01152-5

(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Koga N, Hu Q, Sakai A, Takada K, Nakanishi

R, Hisamatsu Y, Ando K, Kimura Y, Oki E, Oda Y and Mori M: Clinical

significance of signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) expression

in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 112:3018–3028.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhao CL, Yu S, Wang SH, Li SG, Wang ZJ and

Han SN: Characterization of cluster of differentiation 47

expression and its potential as a therapeutic target in esophageal

squamous cell cancer. Oncol Lett. 15:2017–2023. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yuan H, Qing T, Zhu S, Yang X, Wu W, Xu K,

Chen H, Jiang Y, Zhu C, Yuan Z, et al: The effects of altered DNA

damage repair genes on mutational processes and immune cell

infiltration in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med.

12:10077–10090. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wei Z, Zhao N, Kuang L, Cong J, Zheng S,

Li Y and Liu Z: DNA/RNA-binding protein KIN17 supports esophageal

cancer progression via resolving noncanonical STING activation

induced by R-loop. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:2562025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhang H, Lu G, Hu Y, Yang Q, Jiang J and

Xu M: Wild-type p53 overexpression inhibits DNA damage pathways and

reduces PD-L1 expression in prostate cancer. J Immunother. Aug

12–2025.doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000573 (Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Jiang M, Jia K, Wang L, Li W, Chen B, Liu

Y, Wang H, Zhao S, He Y and Zhou C: Alterations of DNA damage

response pathway: Biomarker and therapeutic strategy for cancer

immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:2983–2994. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sato H, Niimi A, Yasuhara T, Permata TBM,

Hagiwara Y, Isono M, Nuryadi E, Sekine R, Oike T, Kakoti S, et al:

DNA double-strand break repair pathway regulates PD-L1 expression

in cancer cells. Nat Commun. 8:17512017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H,

Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS, et

al: Mismatch-repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to

PD-1 blockade. Science. 357:409–413. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chen G, Zhu YJ, Chen J, Miao F, Wu N, Song

Y, Mao BB, Wang SZ, Xu F and Chen ZM: Mutational landscape of DNA

damage response deficiency-related genes and its association with

immune biomarkers in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasma.

69:1314–1321. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Genova C, Dellepiane C, Carrega P,

Sommariva S, Ferlazzo G, Pronzato P, Gangemi R, Filaci G, Coco S

and Croce M: Therapeutic implications of tumor microenvironment in

lung cancer: Focus on immune checkpoint blockade. Front Immunol.

12:7994552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Astaneh M, Rezazadeh H, Hossein-Nataj H,

Shekarriz R, Zaboli E, Shabani M and Asgarian-Omran H: Tim-3 and

PD-1 blocking cannot restore the functional properties of natural

killer cells in early clinical stages of chronic lymphocytic

leukemia: An in vitro study. J Cancer Res Ther. 18:704–711. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Liu Y, Cheng Y, Xu Y, Wang Z, Du X, Li C,

Peng J, Gao L, Liang X and Ma C: Increased expression of programmed

cell death protein 1 on NK cells inhibits NK-cell-mediated

anti-tumor function and indicates poor prognosis in digestive

cancers. Oncogene. 36:6143–6153. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hsu J, Hodgins JJ, Marathe M, Nicolai CJ,

Bourgeois-Daigneault MC, Trevino TN, Azimi CS, Scheer AK, Randolph

HE, Thompson TW, et al: Contribution of NK cells to immunotherapy

mediated by PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. J Clin Invest. 128:4654–4668.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Beldi-Ferchiou A, Lambert M, Dogniaux S,

Vély F, Vivier E, Olive D, Dupuy S, Levasseur F, Zucman D, Lebbé C,

et al: PD-1 mediates functional exhaustion of activated NK cells in

patients with Kaposi sarcoma. Oncotarget. 7:72961–72977. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Chuang CH, Guo JC, Kato K and Hsu CH:

Exploring novel immunotherapy in advanced esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma: Is targeting TIGIT an answer? Esophagus. 22:139–147.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chu X, Tian W, Wang Z, Zhang J and Zhou R:

Co-inhibition of TIGIT and PD-1/PD-L1 in Cancer Immunotherapy:

Mechanisms and Clinical Trials. Mol Cancer. 22:932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Sivori S, Pende D, Quatrini L, Pietra G,

Della Chiesa M, Vacca P, Tumino N, Moretta F, Mingari MC, Locatelli

F and Moretta L: NK cells and ILCs in tumor immunotherapy. Mol

Aspects Med. 80:1008702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yan C, Ma X, Guo Z, Wei X, Han D, Zhang T,

Chen X, Cao F, Dong J, Zhao G, et al: Time-spatial analysis of T

cell receptor repertoire in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

patients treated with combined radiotherapy and PD-1 blockade.

Oncoimmunology. 11:20256682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Portale F and Di Mitri D: NK Cells in

cancer: Mechanisms of dysfunction and therapeutic potential. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:95212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zheng Y, Li Y, Lian J, Yang H, Li F, Zhao

S, Qi Y, Zhang Y and Huang L: TNF-α-induced Tim-3 expression marks

the dysfunction of infiltrating natural killer cells in human

esophageal cancer. J Transl Med. 17:1652019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yan Z, Wang C, Wu J, Wang J and Ma T:

TIM-3 teams up with PD-1 in cancer immunotherapy: Mechanisms and

perspectives. Mol Biomed. 6:272025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Sivori S, Vacca P, Del Zotto G, Munari E,

Mingari MC and Moretta L: Human NK cells: Surface receptors,

inhibitory checkpoints, and translational applications. Cell Mol

Immunol. 16:430–441. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Gemelli M, Noonan DM, Carlini V, Pelosi G,

Barberis M, Ricotta R and Albini A: Overcoming resistance to

checkpoint inhibitors: Natural killer cells in Non-small cell lung

cancer. Front Oncol. 12:8864402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang L, Chen Z, Liu G and Pan Y:

Functional crosstalk and regulation of natural killer cells in

tumor microenvironment: Significance and potential therapeutic

strategies. Genes Dis. 10:990–1004. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhang H, Wang J and Li F: Modulation of

natural killer cell exhaustion in the lungs: The key components

from lung microenvironment and lung tumor microenvironment. Front

Immunol. 14:12869862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Hu W, Wang G, Huang D, Sui M and Xu Y:

Cancer immunotherapy based on natural killer cells: Current

progress and new opportunities. Front Immunol. 10:12052019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Shimasaki N, Coustan-Smith E, Kamiya T and

Campana D: Expanded and armed natural killer cells for cancer

treatment. Cytotherapy. 18:1422–1434. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Marofi F, Abdul-Rasheed OF, Rahman HS,

Budi HS, Jalil AT, Yumashev AV, Hassanzadeh A, Yazdanifar M,

Motavalli R, Chartrand MS, et al: CAR-NK cell in cancer

immunotherapy; A promising frontier. Cancer Sci. 112:3427–3436.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Thangaraj JL, Coffey M, Lopez E and

Kaufman DS: Disruption of TGF-β signaling pathway is required to

mediate effective killing of hepatocellular carcinoma by human

iPSC-derived NK cells. Cell Stem Cell. 31:1327–1343.e5. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Li T, Wang X, Niu M, Wang M, Zhou J, Wu K

and Yi M: Bispecific antibody targeting TGF-β and PD-L1 for

synergistic cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 14:11969702023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Karami Z, Mortezaee K and Majidpoor J:

Dual anti-PD-(L)1/TGF-β inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy-Updated.

Int Immunopharmacol. 122:1106482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Lucarini V, Melaiu O, D'Amico S, Pastorino