Introduction

Cancer therapies that rely on the induction of

apoptosis have long faced significant challenges due to one of the

defining hallmarks of cancer cells; their inherent ability to evade

apoptotic cell death (1).

Traditionally, cell death has been considered to occur following

two main pathways: The physiological process of apoptosis and the

pathological process of necrosis. Previously, new forms of

programmed cell deaths have been discovered, one of which being

ferroptosis. In 2012, Dixon et al (2) coined the term ‘ferroptosis’ after

discovering a form of cell death induced by an increase in reactive

oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation (LPO) (2). The Nomenclature Committee on Cell

Death later classified ferroptosis as a form of non-apoptotic cell

death, based on its unique morphological and biochemical features

(3). This type of cell death

differs from apoptosis as it does not involve cell shrinkage, and

from necrosis as it does not result in cell swelling. Additionally,

it occurs independently of caspase activation (4).

The standard treatment for malignant tumors commonly

includes chemotherapy, often combined with other approaches such as

radiotherapy and surgical resection. Both chemotherapy and

radiotherapy are intended to target rapidly dividing cancer cells

but may also affect normal proliferating cells (5). In certain cancers, such as

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), resistance to chemotherapy can

develop secondary to the expression of resistance-associated genes,

thereby lowering the effectiveness of conventional therapeutics

(6).

The activation of ferroptosis has emerged as a

promising cancer therapeutic strategy. Inducing this non-apoptotic

form of regulated cell death has shown effectiveness across various

cancer types, offering new avenues for overcoming chemoresistance

and improving outcomes. In the present review, the molecular

mechanisms underlying ferroptosis were first explored, then the

findings specific to different cancer types were examined, and

finally the potential of ferroptosis-based therapeutic approaches

were assessed.

Mechanisms of ferroptosis

Understanding the intricacies of this cell death

pathway requires a closer look at the molecular regulators of iron

homeostasis, antioxidant defense and lipid metabolism.

Iron metabolism

Tumor cells often exhibit iron overload, making them

prone to ferroptotic cell death. Key iron metabolism-associated

proteins such as transferrin, transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1),

ferroportin, ferritin and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) are

frequently dysregulated during carcinogenesis. The regulatory role

of iron metabolism in ferroptosis is illustrated in Fig. 1.

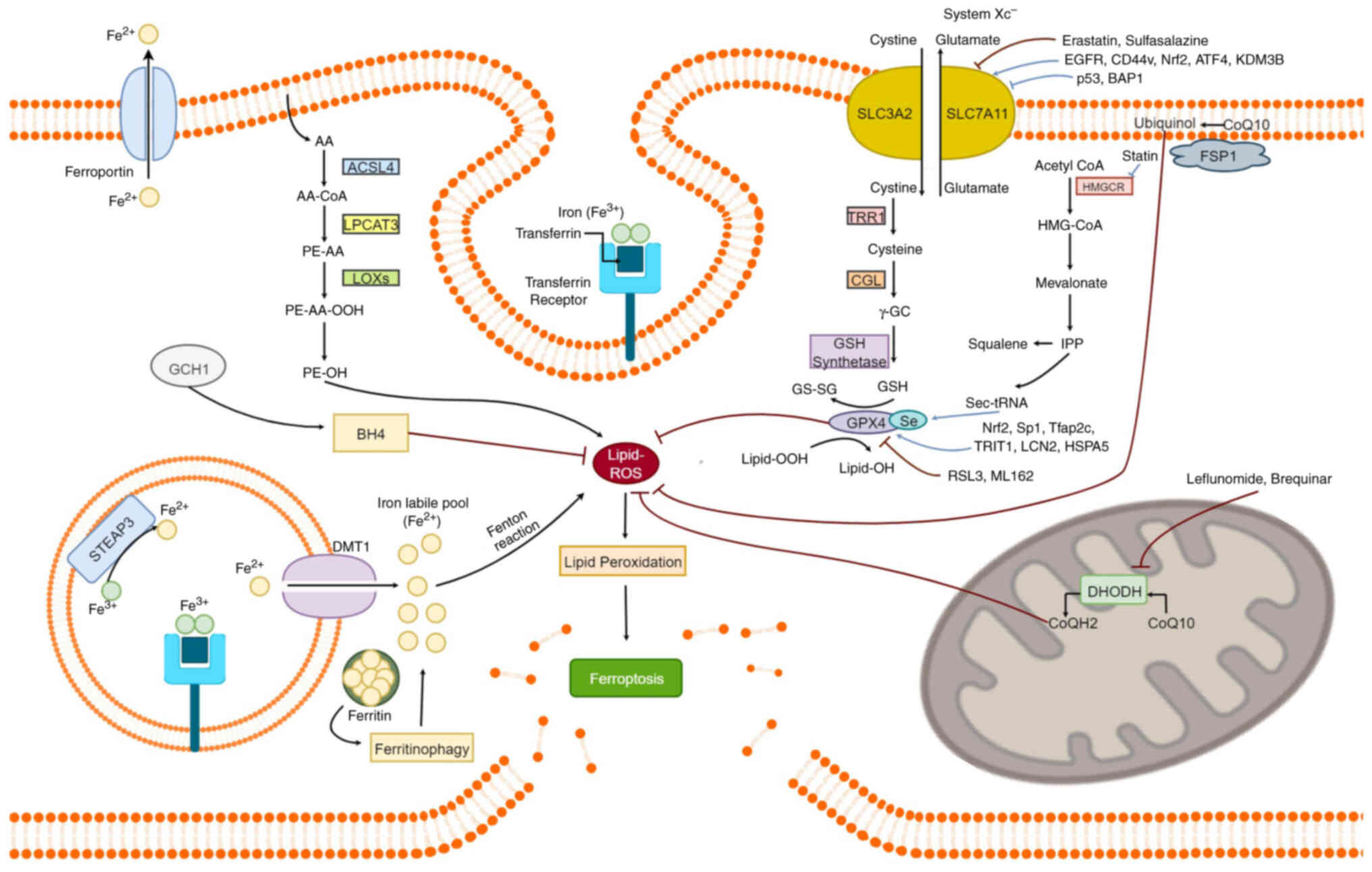

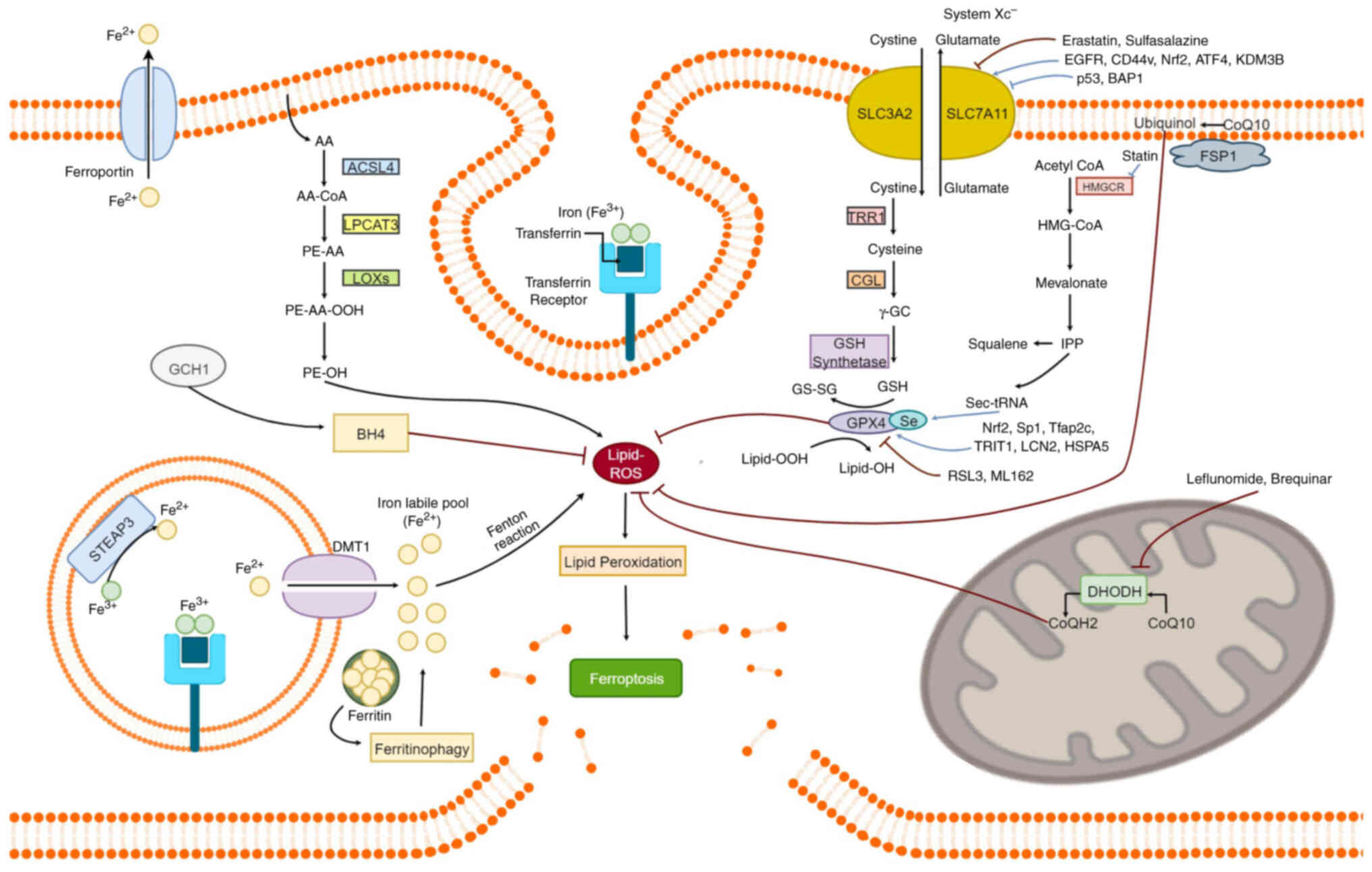

| Figure 1.Overview of key pathways and

molecular regulators involved in ferroptosis, an iron dependent

form of regulated cell death marked by the accumulation of ROS.

Iron metabolism increases the labile iron pool (Fe2+),

which drives LPO through Fenton reactions. The System

Xc− antiporter, composed of SLC7A11 and SLC3A2, imports

cystine in exchange for glutamate, enabling the synthesis of GSH, a

crucial antioxidant that supports GPX4 function. GPX4 protects

cells from ferroptosis by converting toxic lipid hydroperoxides

(Lipid-OOH) into non-toxic lipid-alcohols (Lipid-OH). Enzymes such

as ACSL4, LPCAT3 and LOXs facilitate phospholipid peroxidation,

enhancing ferroptosis. Ferritin degradation (ferritinophagy)

releases free iron, enhancing sensitivity to ferroptotic cell

death. In mitochondria, DHODH reduces CoQ to CoQH2, providing an

additional defense against lipid peroxidation, particularly when

GPX4 activity is impaired. In the cytosol, the GCH1/BH4 axis offers

a GPX4-independent antioxidant pathway, where BH4 synthesis helps

suppress lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Small molecules (for

example, erastin and RSL3) and regulatory proteins (for example,

FSP1, NRF2 and p53) modulate ferroptotic signaling through various

mechanisms, including GSH depletion and GPX4 inhibition. ROS,

reactive oxygen species; LPO, lipid peroxidation; GSH, reduced

glutathione; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; LOX, lipoxygenase;

DHODH, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; CoQ10, Coenzyme Q10; COX,

cyclooxygenase. |

Transferrin is a glycoprotein that transports iron

through the bloodstream in a controlled, non-toxic form (7). It plays an indirect yet significant

role in regulating ferroptosis by modulating the cellular iron

pool. Iron is delivered to cells via the interaction between

transferrin and TFR1 on the cell surface. TFR1 expression is

tightly linked to iron availability: It is upregulated under

conditions of low intracellular iron to enhance uptake, and

downregulated when iron is abundant to prevent overload (8). As such, TFR1 is a key regulator of

cellular iron homeostasis and plays a pivotal role in balancing a

cell's vulnerability or resistance to ferroptosis. Once

internalized, iron binds to ferritin, an intracellular iron-storage

protein. Accumulation of free Fe2+ in the cell,

resulting either from iron overload or from insufficient expression

or excessive degradation of ferritin, leads to the conversion of

hydrogen peroxide to hydroxyl radicals, through the Fenton

reaction, resulting in production of ROS. If cellular ROS

accumulates secondary to disruptions in the cell's antioxidant

system, it will lead to LPO, the hallmark of ferroptosis, and

subsequent cell death (9).

Ferritin is an intracellular iron-storage protein

that plays a central role in iron homeostasis by sequestering

excess iron and releasing it when needed (10). Structurally, ferritin consists of 24

subunits comprising heavy (H) and light (L) chains, which together

can store thousands of iron atoms (11). This prevents iron from participating

in Fenton reactions and minimizes oxidative stress (12). Similarly to TFR1, ferritin

expression is also linked to iron availability, as well as the

presence of certain hormonal regulators such as hepcidin (13). Elevated ferritin levels reduce the

pool of free iron and suppress ferroptosis. Conversely, low

ferritin expression increases labile iron levels, promoting Fenton

chemistry, LPO and ultimately, ferroptosis. In the context of

carcinogenesis, ferritin regulation is often disrupted. Tumor cells

frequently upregulate ferritin expression to buffer against

iron-induced oxidative stress, thereby enhancing resistance to

ferroptosis and promoting survival under iron-rich conditions

(14).

Ferroportin, a transmembrane protein that exports

iron from cells into the bloodstream to re-enter circulation,

recycles transferrin back into the bloodstream, regulating systemic

iron homeostasis. Hepcidin, a hormone synthesized by the liver,

tightly regulates ferroportin by inducing its degradation to

maintain iron homeostasis (15).

Elevated hepcidin levels lead to ferroportin internalization and

subsequent degradation resulting in reduced iron efflux and

ultimately increased ferroptosis. However, when hepcidin levels are

low, ferroportin is found more abundantly on the cell surface,

increasing iron efflux, and most importantly, decreasing the cell's

susceptibility to iron-induced stress and ferroptosis (16). Often, ferroportin is downregulated

in several types of cancer, leading to iron accumulation, and

rendering them more susceptible to ferroptosis (17). It has been reported that taking

advantage of this downregulation may provide an alternative

therapeutic strategy, leading to ferroptotic cell death in several

tumors. However, targeting ferroportin expression must be conducted

carefully as it could be a double-edged sword, potentially both

protecting and eliminating cancer cells (18).

DMT1, also known as natural resistance-associated

macrophage protein 2, is a transmembrane protein involved in the

uptake of dietary iron from the small intestine, the absorption of

iron by proliferating red blood cells, and the ejection of iron

from endosomes in numerous cell types (19). The expression of DMT1 is inversely

regulated by iron availability. Elevated iron levels lead to the

downregulation of DMT1, while low iron levels lead to its

upregulation (20). Cellular

sensitivity to ferroptosis increases when DMT1 is overexpressed.

DMT1 expression varies across tumor types with tumors having a high

demand for iron often showing DMT1 upregulation, whereas others

downregulate DMT1 as an anti-ferroptotic defense mechanism against

iron accumulation. It has been revealed that overactivation of DMT1

can promote ferroptosis in several cancers, highlighting its

potential as a therapeutic target (21).

It is now well established that ferroptosis occurs

in cells with dysregulated iron metabolism or impaired antioxidant

defense. Malfunction, mutation or dysregulation of any of the key

proteins involved in these processes can either reduce or enhance

cellular vulnerability to ferroptosis.

GSH/GPX4/System Xc−

axis

GSH and GPX4 as central antioxidant defenses

The GSH/GPX4/System Xc− axis serves as

the primary defense mechanism against ferroptosis by suppressing

the accumulation of lipid peroxides. At its core, the key

regulatory enzyme glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) utilizes reduced

glutathione (GSH) to reduce lipid peroxides into non-toxic lipid

alcohols, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis (22). GSH is then regenerated from its

oxidized form (GSSG) by glutathione reductase. Therefore,

maintaining adequate intracellular GSH levels is vital for

sustaining GPX4 activity and blocking this cell death pathway

(23,24).

System Xc−

GSH biosynthesis is dependent on cystine uptake

mediated by the System Xc− amino acid antiporter, which

is expressed in various cell types, including hepatocytes,

fibroblasts and macrophages (25).

This transporter consists of two subunits, SLC3A2 and SLC7A11, and

exchanges intracellular L-glutamate for extracellular L-cystine.

Upon entry into the cell, the L-cystine molecule is reduced to

L-cysteine by thioredoxin reductase 1 (26). L-cysteine then combines with

glutamate to form γ-glutamyl cysteine, in a reaction catalyzed by

glutamate-cysteine-ligase (GCL). The subsequent addition of glycine

to the γ-glutamyl cysteine, catalyzed by the enzyme GSH synthetase,

generates the potent antioxidant GSH.

SLC7A11 regulation

The activity of the System Xc-antiporter is

primarily determined by the expression of its SLC7A11 subunit.

Elevated SLC7A11 expression promotes cystine uptake, facilitating

GSH synthesis promoting cell survival by suppressing ferroptosis.

Conversely, reduced SLC7A11 expression impairs this antioxidant

defense pathway, inducing ferroptotic cell death (27). Therefore, regulation of SLC7A11 is

critical in ferroptosis resistance (28).

Transcriptionally, transcription factors such as

activating factor 4 (ATF4) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor (NRF2) induce SLC7A11 expression under oxidative and

nutrient stress (cysteine deprivation) respectively, while in

cancer, ATF4 additionally supports tumor growth, proliferation and

angiogenesis (29–31).

Epigenetically, repressors including nuclear

deubiquitinase, anti-oncogene BRCA1-associated protein 1 and tumor

suppressor protein p53 have been shown to interact with the SCL7A11

gene promoter and repress its expression, reducing L-cysteine

uptake and increasing sensitivity to ferroptosis (32,33).

By contrast, the histone lysine demethylase 3B enzyme enhances

SLC7A11 expression by demethylating of histone 3 on lysine 9,

enhancing L-cystine uptake and resistance to ferroptosis (34).

Post-translationally, factors such as epidermal

growth factor receptor, adhesion molecule CD44v (expressed in

cancer stem cells) and deubiquitinases, stabilize SLC7A1,

protecting it from degradation and sustaining cystine uptake, thus

decreasing sensitivity to ferroptosis (35,36).

By contrast, small molecule inhibitors such as Erastin block

SLC7A11 function to induce this cell death pathway, highlighting

its potential as a therapeutic target (37).

Beyond SLC7A11, GSH synthesis is regulated by the

enzyme GCL. Inhibition of GCL with sulfonamide or disruption of its

stability reduces GSH production and sensitizes cells to

ferroptosis (38–40). Moreover, pharmacological depletion

of cysteine, such as with engineered cyst(e)inase, selectively

induces cancer cell death by reducing GSH and elevating ROS

(41). Furthermore, salvage

pathways like trans-sulfuration can maintain cysteine and GSH pools

independently of System Xc−, representing an alternative

route to ferroptosis resistance (42,43).

GPX4 regulation

Finally, the selenoprotein GPX4 itself is a key

regulatory node in ferroptosis (44). Its expression is dependent on

selenium metabolism and the mevalonate pathway, which generates the

isopentenyl pyrophosphate required for the maturation of the

selenocysteine tRNA essential for the incorporation of Sec into its

catalytic site (45–47). Blocking the mevalonate pathway with

statins, cholesterol-lowering drugs, has been shown to impair GPX4

translation and maturation, thereby increasing cell sensitivity to

ferroptosis (47). At the

transcriptional level, GPX4 is regulated by the transcription

factors such as NRF2, Sp1 and Tfap2c and mTORC, LCN2 upregulates

both SLC7A11 and GPX4 to block ferroptosis (48–51).

Post-translationally, GPX4 and its stability is

primarily regulated by three major protein modifications:

Succination (fumarate binding), alkylation (RSL3, ML162, withaferin

A) and ubiquitination, which can target it for degradation

(52–56).

Epigenetically, chaperones such as heat shock

protein A5 (HSPA5) can directly bind to GPX4, shielding it from

proteasomal degradation and thereby stabilizing the protein

(57). Similarly, lipoxygenases

contribute to GPX4 inactivation by catalyzing the oxidation of its

Sec residue, inactivating its catalytic site (58).

Moreover, some aggressive and chemo-resistant

cancers, such as HCC, have been shown to exhibit increased

sensitivity to LPO. This supports the idea that combining

ferroptosis inducers that target the GSH/System Xc− and

GPX4 axis with conventional chemotherapeutic agents may offer a

novel and effective clinical strategy for cancer treatment

(59). The regulatory role of the

GSH/GPX4/System Xc− axis in ferroptosis is illustrated

in Fig. 1.

LPO and metabolism

Ferroptosis is triggered by the accumulation of

lipid peroxides. It has been previously demonstrated that

phosphatidylethanolamines containing polyunsaturated fatty acids

(PUFAs) such as Arachidonic acid (AA) or adrenac acid (AdA), which

are embedded in the cell membrane, are susceptible to LPO (60). Chemical modifications of these

acids, particularly acylation, can alter their properties and

significantly influence the regulation of ferroptosis. The

acylation of AA/AdA is performed by two enzymes: Acyl-CoA

synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and

lyso-phosphatidyl-choline acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) (61). Inhibition of either enzyme reduces

LPO and, thus, may suppress ferroptosis. Additionally, the

ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) plays a vital role in

protecting cells from ferroptosis due to decreased GPX4 levels.

FSP1 catalyzes the regeneration of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10, also known

as ubiquinone) using NADPH. The reduced form of CoQ10, ubiquinol

traps lipid peroxyl radicals, effectively limiting LPO and

preventing ferroptotic cell death (62).

Among the numerous metabolic alterations observed in

cancer cells, compared with normal; cells, are changes in lipid

metabolism, which have significant implications for ferroptotic

cell death (63). Lipid metabolism

includes fatty acid synthesis and transport, mevalonate and

cholesterol synthesis pathways, as well as several other essential

signaling cascades (64). AA and

AdA are major substrates for LPO and require the activity of two

enzymes: Elongation of very long-chain fatty acid protein 5 and

fatty acid desaturase 1, both of which are highly expressed in

certain tumors such as gastric cancer cells (65). Upregulation of these enzymes has

been shown to increase resistance to ferroptosis in these cells. On

the contrary, epigenetic silencing of these enzymes through DNA

methylation of their respective promoter regions downregulates

their expression, restoring ferroptosis sensitivity (66).

During lipid synthesis, excess glucose is funneled

into the de novo lipogenesis pathway, which enables cells to

synthesize most of their necessary fatty acids, except for a few

essential PUFAs that depend on dietary intake, namely

alpha-linoleic acid and linoleic acid (67,68).

Compared with a healthy cell, cancer cells divert glucose for

anabolic processes instead of using it for oxidative energy

production (69). In fact, nearly

all fatty acids in tumor cells are derived from endogenous

synthesis (70). This metabolic

shift suggests that cancer cells may evade ferroptosis by

upregulating de novo lipogenesis, ensuring a continuous

supply of fatty acids.

Moreover, one of the products of this pathway,

triacylglycerol, contributes to the formation of lipid droplets

(LDs), which are energy storage units implicated in cancer cell

metabolism and proliferation (71).

Certain cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, necessary for LPO, have been

localized within LDs and shown to enhance angiogenesis, suggesting

that elevated LD levels may play a critical role in ferroptosis

resistance (72).

In case the de novo lipid synthesis pathway

is impaired, cancer cells compensate by increasing lipid uptake.

This is mediated by the increased expression of fatty acid

transporter (FATP), fatty acid translocase (FAT/Cluster of

differentiation 36 or CD36) and fatty acid-binding proteins, which

facilitate the import of extracellular fatty acids. These

transporters are not only highly expressed in cancer cells but are

also associated with increased tumor metastasis (73). Notably, studies have shown that the

inhibition of CD36 and FATP2 has been shown to suppress tumor

growth and promote ferroptosis, highlighting their potential as

therapeutic targets (74,75).

The mevalonate pathway, responsible for cholesterol

biosynthesis, is tightly linked to the regulation of ferroptosis

and the activity of the GPX4 selenoprotein (76). Within this pathway, the enzyme

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) catalyzes the

conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate. HMGCR is frequently

upregulated in cancer cells, where it promotes their proliferation

and migration. However, inhibiting this enzyme has been shown to

increase vulnerability to ferroptosis, largely due to its

disruptive effect on the overall pathway and the subsequent

impairment of GPX4 maturation and function (77). Moreover, the use of statins inhibits

HMGCR, leading to inactivation of GPX4 and the increase in

ferroptosis occurrence overall (59). The contribution of LPO to

ferroptosis is illustrated in Fig.

1.

GPX4-independent regulation of

ferroptosis

DHODH/CoqH2 axis

Recent studies have explored the role of

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) in the context of ferroptosis

regulation. DHODH is a mitochondrial inner-membrane enzyme capable

of reducing CoQ to regenerate CoqH2, thus mitigating LPO and

ultimately suppressing ferroptotic activity. This axis serves as

the main mitochondrial defense against LPO (78). In addition, loss of GPX4 function is

significantly compensated by enhanced production of DHODH-mediated

CoQH2, especially in cancer cells (79). DHODH inhibitors such as leflunomide

and Brequinar have shown promising results in cancers such as HCC

where GPX4 is lowly expressed, significantly enhancing cell

sensitivity to ferroptosis and boosting therapeutic approaches

(80,81).

GCH1/BH4 axis

While the DHODH/CoqH2 axis is localized in the

mitochondria, the GCH1/BH4 axis is primarily a cytosolic pathway,

recently identified as a GPX4-independent ferroptotic regulatory

system (82).

Guanosine-5′-triphoshpate cyclohydrolase-1 (GCH1) catalyzes the

biosynthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a prominent antioxidant

similar in function to CoQ10. A direct link between GCH1 expression

levels and cell resistance to ferroptosis has been reported.

Indeed, inhibition of GCH1 leads to low levels of BH4 and thus

drives cells towards accumulation of LPO and eventually,

ferroptotic death (83). By

contrast, upregulation of this axis protects cells from

ferroptosis, and emerging data highlights specific pathways, such

as the RAS pathway in oncogenic signaling, capable of enhancing

GCH1 transcription and suppressing ferroptosis (84).

Altogether, the DHODH/CoQH2 axis as well as the

GCH1/BH4 axis are both GPX4-independent regulatory systems of

ferroptosis, localized within the mitochondria and the cytosol,

respectively. Emerging research focuses on their vulnerability and

targetability in cancer therapy (85).

Ferroptosis across cancers

The molecular framework of ferroptosis manifests

differently across cancer types, with distinct patterns of iron

regulation, antioxidant capacity and lipid metabolism shaping each

tumor's response to ferroptotic stress. In the present review,

cancers where ferroptosis has been more extensively investigated

(for example, HCC, lung, breast, bladder and gastrointestinal

cancers) were prioritized, while noting that studies in ovarian,

cervical and thyroid cancers remain comparatively limited. To

provide a focused and comprehensive overview rather than an

exhaustive survey, HCC and bladder cancer were selected as

representative examples. HCC was chosen given the extensive body of

research available, whereas bladder cancer was included to

highlight a tumor type in which ferroptosis is less well explored.

Together, these examples capture both established and emerging

perspectives on ferroptosis-related vulnerabilities.

Bladder cancer

Mazdak et al (86) reported that patients with bladder

cancer had significantly lower serum iron levels compared with

healthy controls, suggesting that reduced free and serum iron may

play a role in promoting bladder cancer development. Indeed,

reduced levels of free iron have been shown to markedly promote the

growth of bladder cancer cells (87). However, treatment with baicalin, a

bioactive flavonoid compound, has been shown to elevate

intracellular chelated iron and generate ROS, promoting ferroptosis

in vitro and in vivo. To further elucidate the

underlying mechanisms, the expression of iron regulatory protein

and DNA damage-related proteins was assessed using western

blotting. Results showed increased transferrin, phosphorylated

histone H2AX, p53 and tumor suppressor p53 binding protein 1

levels, alongside a notable decrease in ferritin heavy chain 1

(FTH1) levels in baicalin-treated bladder cancer cell lines 5637

and KU-19-19. Interestingly, the use of ferroptosis inhibitors

reversed this effect, confirming that this is the predominant cell

death pathway (88).

Proteins that regulate ferroptosis, such as GPX4 and

SLC7A11, also play important roles in tumor-related signaling

pathways, particularly in bladder cancer development. SLC7A11

appears to be controlled by the deubiquinating enzyme OTUB1, which

is overexpressed in human bladder cancer and contributes to

ferroptosis resistance (36). In

vivo and in vitro experimental studies revealed that

deleting OTUB1 lowers SLC7A11 levels, decreases cystine uptake, and

induces ferroptosis, indicating that targeting SLC7A11 may

contribute to inhibition of bladder cancer progression (87,89).

Furthermore, ferroptosis in bladder cancer cells can

also occur due to a collapse of the antioxidant defense system and

ROS accumulation. Following treatment with erianin, elevated levels

of ROS and reduced GSH levels were reported. Additionally,

malondialdehyde (MDA) levels increased, and ferrous iron

accumulated in the bladder cancer cells, all of which drive

ferroptosis (90). Western blot

analysis further revealed that erianin significantly downregulated

several key ferroptosis-associated proteins, including NRF2, FTH1,

GPX4, heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), glutaminase and xCT/SLC7A11 in

KU-19-19 and RT4 bladder cancer cells (91). Collectively, the downregulation of

these specific proteins impairs the cell's ability to maintain a

redox balance resulting in ferroptotic death.

Finally, recent research explores the crosstalk

between autophagy and ferroptosis in bladder cancer. FIN56, a

potent ferroptosis inducer through the degradation of GPX4 and

ferritin, was found to be enhanced when combined with Torin 2, an

autophagy activator. Interestingly, FIN56-induced ferroptosis was

suppressed by bafilomycin A1 and SAR405, both of which attenuated

LPO (92). These findings confirm

that ferroptosis may also occur dependent on autophagy,

specifically ferritin (ferritinophagy). A summary of

key-ferroptosis related vulnerabilities and therapeutic approaches

in this type of cancer is presented in Table I.

| Table I.Cancer type-specific ferroptosis

vulnerabilities and therapeutic strategies. |

Table I.

Cancer type-specific ferroptosis

vulnerabilities and therapeutic strategies.

| Cancer type | Key

vulnerabilities | Ferroptosis

inducers | Major molecular

changes | Sensitization

strategies |

|---|

| Bladder | GSH/GPX4 depletion,

autophagy-dependence, iron/ROS imbalance | Baicalin, Erianin,

FIN56, RSL3 | ↓Serum iron;

↑ROS/Fe2+/MDA; ↑Tf/p53/p-H2AX/p53BP1;

↓FTH1/GPX4/SLC7A11/NRF2/HO-1/GLS; OTUB1-mediated ↑SLC7A11 | GSH/GPX4 depletion;

SLC7A11/OTUB1 suppression; autophagy-dependent ferritinophagy |

| HCC | GSTZ1-NRF2-GPX4

axis, PSAT1 regulation | Sorafenib,

Trigonelline, Punicallin | ↓GSTZ1,

↑SLC7A11/PSAT1 (context-dependent) | NRF2 targeting,

PSAT1/SLC7A11 inhibition, cysteine salvage blocking |

| NSCLC | High SLC7A11 and

GPX4 expression | Erastin, Sorafenib,

Cisplatin (combos) | ↑SLC7A11

(RBMS1-driven), GPX4 (mTORC1-mediated) | RBMS1 knockout,

mTORC1 inhibition, cisplatin combos |

| TNBC | Selenocysteine

biosynthesis (GPX4/SLC7A11) | RSL3,

Sulfasalazine | ↑GPX4 and SLC7A11

(selenocysteine-rich) | miR-5096

overexpression to target SLC7A11 |

|

Gastric/Colorectal | GPX4/SLC7A11

overexpression | Erastin | GPX4/SLC7A11

overexpression | CDO1 silencing to

sensitize cells |

| PDAC | Nrf2-mediated

GPX4/GSH, apoptosis resistance | Gemcitabine +

Erastin (with LONP1) | Gemcitabine

↑Nrf2/GPX4; LONP1 inhibits Nrf2/GPX4 | LONP1 + Erastin to

block GPX4 |

| Leukemia | Iron/ROS overload,

GSH/GPX4 and SLC7A11 dependence, lipid ROS stress | RSL3, FIN56, ML385,

BL-8040, Erastin (±BV6) | ↑Iron/ROS,

↑GSH/GPX4/SLC7A11/NRF2/FSP1; LPO; immune suppression | GSH/GPX4 and

SLC7A11 suppression; NRF2 inhibition; cysteine salvage disruption;

lipid ROS exploitation |

HCC

The primary therapeutic approach for inducing

ferroptosis in HCC cells involves targeting the system

Xc− antiporter and the GPX4 selenoprotein (93). Sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor,

is commonly used as a first-line treatment for advanced HCC and has

been shown to stimulate ferroptosis (94). However, due to the chemorefractory

nature of HCC, the emergence of resistance-related genes limits its

efficacy. Upon treatment with sorafenib, dysregulation of several

transcription factors such as NRF2, retinoblastoma (Rb) protein,

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α), HIC ZBTB Transcriptional

Repressor 1 (HIC1), as well as components of the Hippo pathway, can

be observed. A well-documented link exists between sorafenib and

the NRF2 signaling axis. By inhibiting system Xc−,

sorafenib depletes intracellular GSH, prompting compensatory

activation of the NRF2 pathway. Moreover, using trigonelline to

inhibit this pathway appears to enhance the antitumor effect of

sorafenib (95). Additionally, NRF2

upregulates the expression of several iron metabolism-related genes

such as HO-1, Metallothioenin-1G and Sigma-1 receptor, all of which

contribute to suppression of ferroptosis (96–98).

Previous studies have also elucidated the role of glutathione

S-transferase zeta 1 (GSTZ1), an enzyme involved in the

phenylalanine catabolism, which is markedly downregulated in HCC

cells (99). GSTZ1 does suppress

the NRF2 pathway, resulting in decreased GPX4 expression and

increased sensitivity of HCC cells to ferroptosis (100).

The tumor suppressor proteins Rb, HNF4α and HIC1 all

influence ferroptotic sensitivity via the regulation of the

phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) gene, which plays a

critical role in GSH metabolism. Louandre et al (101) revealed that when Rb is inhibited,

cells are more susceptible to ferroptosis. Similarly, HNF4α and

HIC1 regulate PSAT1 in opposing ways, affecting redox homeostasis

and are therefore interesting targets for overcoming sorafenib

resistance (102). Additionally,

metabolic regulators such as c-Jun have also been associated with

higher levels of expression of PSAT1, thus conferring resistance to

sorafenib (103,104). Finally, dysregulation of the Hippo

pathway has been associated with the overexpression of SCL7A11

subunit of system Xc−, promoting the activity of ATF4

and further increasing resistance to ferroptosis (105).

Beyond these transcription factors, other mechanisms

present a clinical challenge to treatment of liver cancer. For

instance, the enzyme branched-chain amino acid transferase 2

(BCAT2) suppresses ferroptosis by maintaining intracellular GSH

levels (106). Similarly,

ATP-Binding Cassette Subfamily C Member 5 (ABCC5) is overexpressed

in HCC cells and may function analogously to BCAT2 by stabilizing

the expression of SLC7A11 (107).

On the other hand, inhibition of ABCC5 leads to GSH depletion and

marked reduction in sorafenib resistance (108). Additionally, RNA-binding proteins

such as DAZ-Associated protein 1 are upregulated in HCC cells and

contribute to ferroptosis resistance by enhancing SCL7A11 stability

at the transcriptional level. Besides that, micropinocytosis of

cysteine and trans-sulfuration pathways replenish intracellular

cysteine and contribute to GSH synthesis even in the presence of

system Xc− inhibitors, rendering cells resistant to

sorafenib-induced ferroptosis (109). A previous study has discussed the

protective role of the trans-sulfuration pathway that maintains

primary hepatocytes viability for several days, despite the absence

of cystine/cysteine in the medium (110).

Novel therapeutic approaches focus on targeting

proteins involved in these resistance pathways. Recently, a study

by Y. Chen et al (111)

elucidated the correlation of GPX4 with the phosphor-seryl-tRNA

kinase (PSTK) in HCC. Inhibition of PSTK was shown to reduce GSH

metabolism, thereby decreasing GPX4 activity and sensitizing HCC

cells to ferroptosis inducers such as erastin. Furthermore,

inhibition of the PSTK gene with punicalin, an agent used to

treat hepatitis B virus, a major risk factor for HCC development,

and Geraniin, a plant-derived therapeutic compound, resulted in

cytotoxic effects on HCC cells. Additionally, combination therapy

involving punicalin or geraniin with ferroptosis inducers like

sorafenib and erastin exhibited a synergistic effect, enhancing

cancer cell death without causing damage to surrounding organs such

as the kidney, intestine or lung in mouse models. These findings

underscore the therapeutic potential of concurrently targeting the

GPX4/GSH/System Xc− axis alongside conventional

chemotherapeutics as a strategy for overcoming drug-resistant HCC.

The major ferroptosis-related vulnerabilities mechanisms and

therapeutic strategies in this cancer are highlighted in Table I.

Other solid tumors

While ferroptosis offers a promising approach for

the treatment of liver and bladder cancer, it is also important to

highlight its potential in other malignancies such as lung,

gastrointestinal and breast cancers. In non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC), SLC7A11 subunit of the system Xc− antiporter is

highly expressed, promoting metastasis and reducing ROS levels by

facilitating cysteine uptake (112). This overexpression is attributed

to RNA-binding protein RBMS1 that directly enhances transcription

by stabilizing SLC7A11 mRNA. Knockout of this protein led to a

reduction in cysteine uptake and promoted ferroptosis (113). In parallel, the discovery of novel

microRNAs (miRNAs) has gained attention for therapeutic targeting.

These small RNAs bind to the 3′-untranslated region of mRNAs,

leading to its degradation. Notably, inhibition of miR-27a-3p

enhances the sensitivity of NSCLC cells to ferroptosis inducers

such as erastin (114). Alongside

SLC7A11, GPX4 also appears to be highly expressed due to enhanced

activation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway (115). Inhibition of this pathway leads to

downregulation of GPX4 as well as increased sensitivity to

lapatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that potentiates oxidative

stress and leads to ferroptosis (116). Although cisplatin is commonly used

as a first-line therapy, NSCLC cells quickly develop resistance.

Consequently, combination strategies involving low doses of

ciplastin with sorafenib or erastin have shown promise. These

combinations suppress the NRF2/SLC7A11 pathway, amplifying the

anticancer efficacy of cisplatin (117).

Similarly, in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC),

both GPX4 and SLC7A11 are overexpressed, largely due to the

selenophilic nature of most breast cancer cells, which increases

Selenocysteine (Sec) biosynthesis and thus protects cells against

ferroptosis (118). Ferroptosis

resistance in TNBC is usually overcome by inhibiting GPX4 activity

with treatment of RSL3 or sulfasalazine (SAS) (119) or by overexpression miR-5096 which

specifically targets SLC7A11 transcription (120). Gastric and colorectal cancer also

exhibit similar levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 overexpression (121,122) and thus high levels of ferroptosis

resistance. In gastric cancer, it has been shown that silencing of

the CD01 gene strengthens the adaptation of cancer cells to

oxidative stress, conferring resistance to erastin and promoting

proliferation (123). On the other

hand, poor pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma prognosis is often

attributed to the lack of early diagnosis and resistance to

apoptosis-inducers, namely gemcitabine (124). Upon treatment with gemcitabine,

NRF2-mediated GPX expression increases and intracellular GSH levels

are elevated, which can subsequently be targeted by

ferroptosis-inducers for improved therapeutic outcomes (125). Previously, it has been reported

that mitochondrial protease Lon peptidase 1 is capable of

inhibiting NRF2-mediated GPX4 expression, thus promoting induced

ferroptosis when used in conjunction with erastin (126). In summary, the GSH/GPX4/System

Xc− axis plays a crucial role in ferroptosis across

numerous cancer types, presenting itself as a target for

ferroptosis-based therapies aimed at overcoming drug resistance in

cancer cells (127). Key

ferroptosis-associated vulnerabilities and sensitization strategies

across these cancer types are summarized in Table I.

Leukemia

Beyond solid tumors, leukemic cells display

dysregulated iron metabolism, leading to iron overload and

increased ROS production, which in turn disrupt normal

hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) functions like self-renewal,

differentiation and quiescence (128,129). Excess ROS drive further cell

apoptosis and reduce tumorigenic potential, while iron accumulation

reshapes the tumor microenvironment in ways that trigger

ferroptosis in cancer cells (130,131). However, leukemia cells take

advantage of iron overload to fuel their rapid proliferations by

relying on iron-dependent ribonucleotide reductase, an enzyme

required for DNA synthesis (132–134). In addition, iron buildup induced

apoptosis in nearby CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T

cells and natural killer cells, while expanding regulatory T cell

populations, thereby enabling leukemic cells to escape immune

surveillance (135,136). Moreover, unlike solid tumors,

patients with hematological malignancies often undergo repeated

blood transfusions due to chemotherapy and impaired erythropoiesis,

resulting in elevated iron and ROS levels. This, in turn, can

promote the tumorigenic transformation of HSCs by exhausting NADPH

oxidase and GSH (130). Together,

these findings highlight iron metabolism as a double-edged sword in

leukemia, as modulating iron homeostasis alters vulnerability of

leukemic cells to ferroptosis, while disease progression further

exacerbates iron overload in patients (137).

Furthermore, leukemia cells exhibit abnormally high

levels of GSH and GPX4, both of which are key suppressors of

ferroptosis (138). Moreover,

increased GPX4 expression has been associated with a poor prognosis

in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (139,140). Studies have shown that modulation

of GSH and GPX4 is critical for controlling cell death and

proliferation across leukemia subtypes (141). Indeed, GPX4 inhibitors (FIN56 or

RSL3) combined with the NRF2 inhibitor ML385 synergistically

trigger ferroptosis in AML cells (142). Similarly, blocking GSH synthesis

by BL-8040 has been shown to induce ferroptosis in T-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells by promoting oxidative stress

(143). Conversely, supplementing

chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells with GSH or its precursor

N-acetylcysteine markedly improved cell viability, highlighting the

role of GSH in regulating leukemia cell proliferation through

ferroptosis (144). Collectively,

these findings underscore the role of GSH and GPX4 as key

regulators of ferroptosis in across leukemia subtypes, highlighting

the therapeutic potential of targeting the GSH/GPX4 axis to

resistance to conventional treatments (138).

SLC7A11 has been found to be frequently

overexpressed in leukemia and regulate cell proliferation by

regulating ferroptosis (138,145). Inhibiting SLC7A11, genetically or

chemically, leads to cysteine deprivation and reduces AML cell

viability and self-renewal by promoting ferroptosis, while

upregulation of SLC7A11 by the small molecule drug APR-246 enhances

cystine uptake and detoxifies lipid peroxides, protecting cells

from ferroptotic death (146,147). Nevertheless, leukemia cells can

bypass system Xc− inhibition via the trans-sulfuration

pathway to maintain cysteine and GSH levels, which highlights a key

metabolic resistance mechanism to ferroptosis (138).

In addition, dysregulated lipid metabolism and

oxidative stress in leukemic cells promotes lipid ROS accumulation

(148), which leads to LPO, a

hallmark of ferroptosis and a biomarker in patients with leukemia

(149). In ALL cells,

ferroptosis-mediated inhibition of leukemia growth by the combining

RSL3 and BV6 depends on lipid ROS and is preventable with the LPO

inhibitor Fer-1 (150). By

contrast, leukemic cells counteract this stress by activating

antioxidant defenses such as NRF2, SLC7A11 and FSP1, which

neutralize lipid ROS and shield cells from ferroptosis (138). Together, these findings underscore

ferroptosis as a critical vulnerability in leukemia, with iron

metabolism, antioxidant defenses and lipid ROS influencing disease

progression and presenting potential therapeutic targets.

Therapeutic strategies

Exploiting cancer-specific vulnerabilities to

ferroptosis has inspired the development of therapies that harness

this cell death pathway, from targeting metabolism to small

molecule inducers and combination treatments.

Monotherapy approaches

Targeting metabolic pathways

Iron metabolism modulation

Iron metabolism is frequently dysregulated in

various cancers, including breast cancer, pancreatic cancer,

lymphoma and HCC, making iron metabolism-related genes critical

targets for stimulating ferroptosis (151). The use of artesunate, an

antimalarial drug, has been shown to increase lysosomal activity

and iron concentration in cells (152). Additionally, artesunate has been

shown to influence the transcriptional regulation of iron-related

genes (153). One of the

upregulated genes is the nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4)

gene, a selective cargo receptor that mediates degradation of

ferritin by autophagy, in a process termed ferritinophagy, and thus

increases cellular iron concentration and induces ferroptosis

(154). Cisplatin, another

chemotherapeutic agent, targets ferritin degradation in a similar

fashion by upregulating NCOA4 and contributing to GSH depletion,

leading to an increase in intracellular iron concentration and

reduced GPX4 activity, ultimately triggering ferroptosis (155). In addition to classical

chemotherapeutics, natural products such as Baicalin, derived from

the traditional Chinese medicinal herb Scutellaria

baicalensis has also been shown to influence iron metabolism

and promote ferroptosis. Baicalin facilitates iron buildup and LPO,

both critical for triggering ferroptosis. Treatment of osteosarcoma

cells with this natural compound has been shown to enhance iron

accumulation, ROS generation and MDA production, while decreasing

the ratio of GSH to GSSG (156).

However, different cancer types may respond

differently to modulators of iron metabolism. For example, some

tumors may develop resistance to iron overload caused by cisplatin

by upregulating ferroportin or activating NRF2 to strengthen

antioxidant defenses. Additionally, off-target ferroptosis in cells

with naturally high levels of iron may also occur, causing

undesirable systemic oxidative stress and posing a significant

clinical challenge. The role of iron modulation in

ferroptosis-based therapy is outlined in Fig. 2.

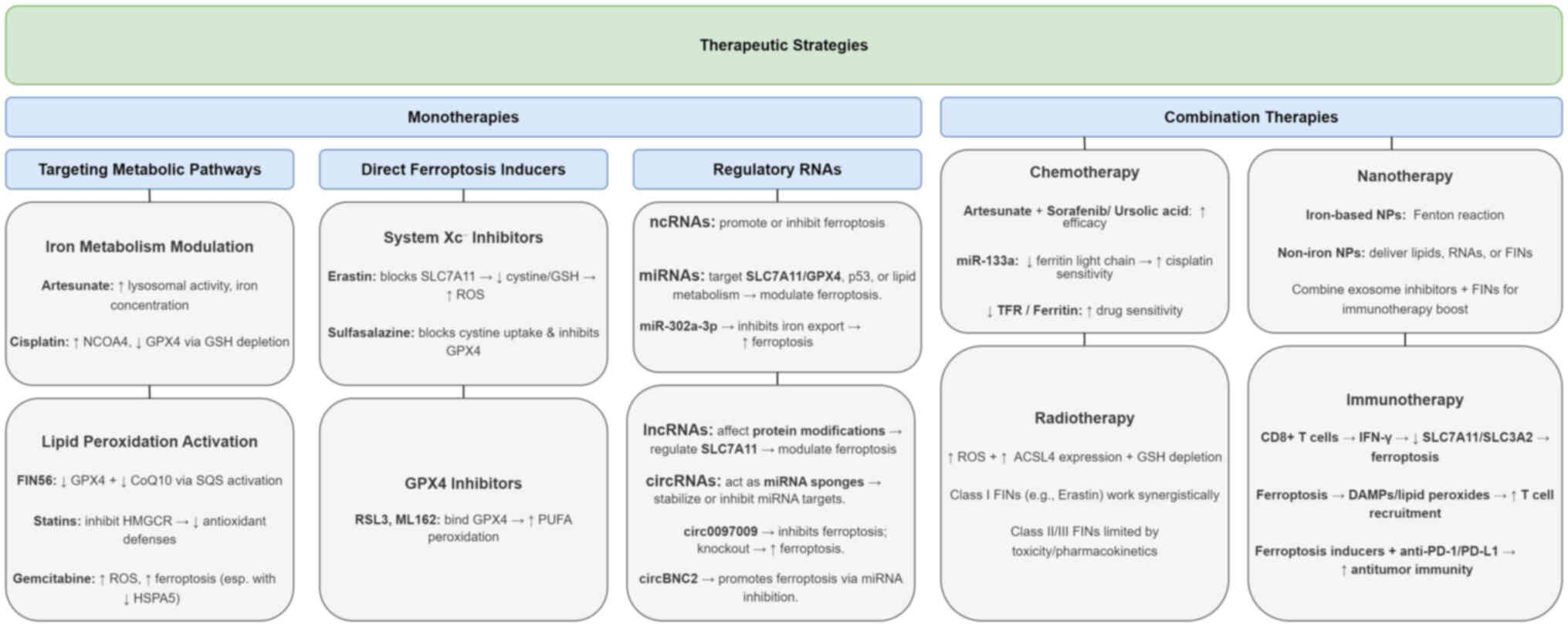

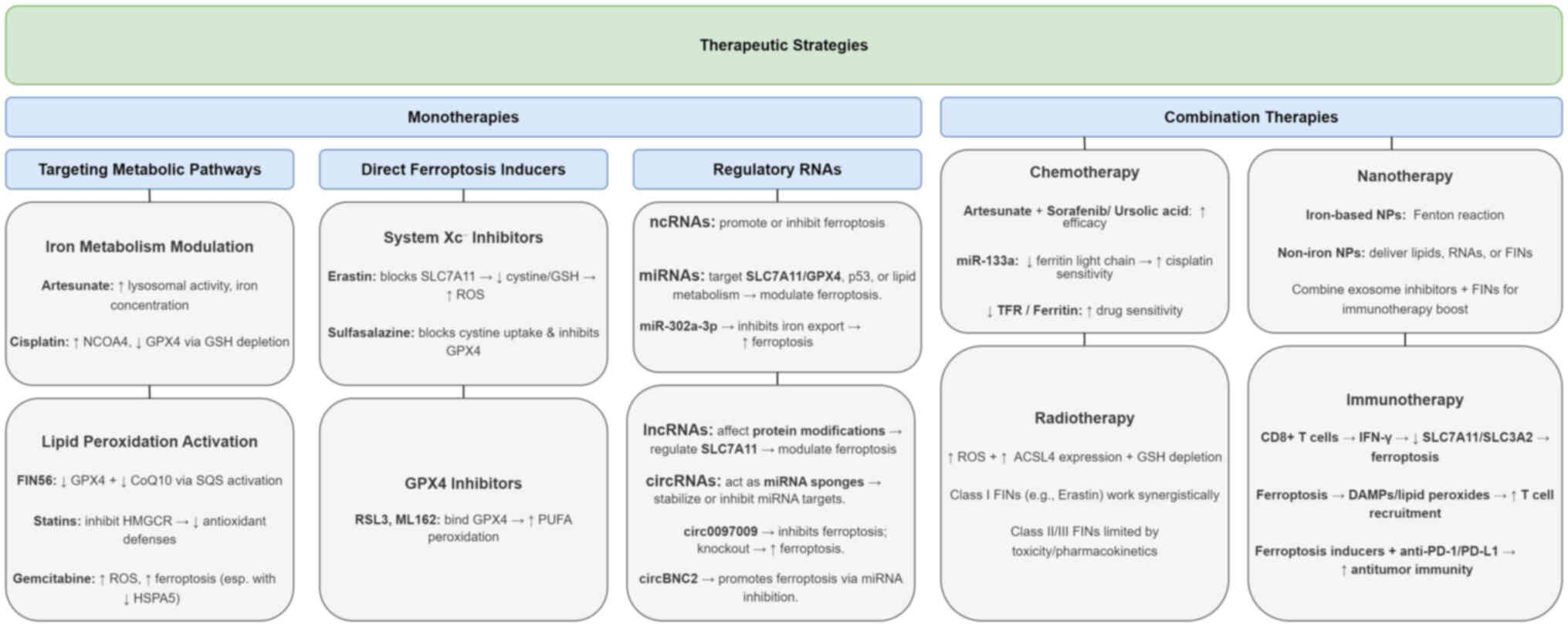

| Figure 2.Key therapeutic approaches to induce

ferroptosis in cancer cells can be classified into two main

categories: monotherapies and combination therapies. Monotherapies

can be further categorized as: i) targeting metabolic pathways,

including modulation of iron metabolism and activation of LPO; ii)

using direct ferroptosis inducers, such as inhibitors of System

Xc− or GPX4; and iii) employing regulatory RNAs, such as

miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs. Combination therapies include

strategies that synergize with chemotherapy, radiotherapy,

immunotherapy, or nanotechnology-based approaches. LPO, lipid

peroxidation; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; miRNAs or miRs,

microRNAs; lncRNAs, long non-coding RNAs; circRNAs, circular RNAs;

ROS, reactive oxygen species; GSH, reduced glutathione; NCOA4,

nuclear receptor coactivator 4; CoQ10, Coenzyme Q10; HMGCR,

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; HSPA5, heat shock protein

family A (Hsp70) member 5. |

Activation of LPO

LPO may occur in two distinct pathways. The

non-enzymatic pathway involves the Fenton Reaction, where hydrogen

peroxide reacts with ferrous ions (Fe2+) to generate

hydroxyl radicals, contributing to oxidative damage and ferroptosis

(157). Alternatively, the

enzymatic pathway engages lipoxygenases (LOX), cytochrome p450

oxidoreductase (POR) and COX enzymes, all of which trigger

ferroptosis by facilitating ROS production (158). LOX enzymes catalyze the oxidation

of PUFAs in membrane phospholipids and may be transcriptionally

regulated by p53 to promote ferroptosis (159). Furthermore, POR donates electrons

from NADPH to downstream effectors such as cytochrome p450,

reducing them in the process and allowing the peroxidation of

membrane-bound PUFAs, which may eventually trigger ferroptotic cell

death (160).

Certain ferroptosis inducers, such as FIN56, act

through dual mechanisms: Promoting GPX4 degradation and activating

squalene synthase, which exhausts levels of CoQ10, a coenzyme

involved in the mevalonate pathway, thereby sensitizing cells to

ferroptosis (89). Alternatively,

pharmacological inhibition of this pathway through statins, which

block HMGCR, has also shown potential anticancer therapies by

impairing antioxidant defenses and enhancing ferroptotic

susceptibility (161).

Therapeutic strategies may also involve targeting

lipid metabolism in cancer cells. Specifically, modulating LPO

through enzymes such as COX, LOX and cytochrome POR presents a

promising avenue for inducing ferroptosis. Gemcitabine, an

antimetabolite that disrupts DNA replication and is commonly used

in treating pancreatic cancers, causes ROS accumulation and

stimulates ferroptosis (162).

Interestingly, the anticancer effect of gemcitabine is enhanced

when HSPA5 is unable to bind to and stabilize GPX4, leading to its

degradation and eventual ferroptosis (57).

Furthermore, erianin, a bioactive compound extracted

from Dendrobium chrysotoxum Lindl, has been reported to

trigger ferroptosis by iron-dependent LPO in multiple cancer cell

types. It has been shown to facilitate the buildup of harmful

lipid-based ROS and deplete GSH, a key cellular antioxidant,

thereby inducing oxidative stress and cell death, which are

hallmarks of ferroptosis (91,163–165). Moreover, it has been shown to

elevate intracellular Fe2+ concentrations, which

catalyze ROS generation via the Fenton reaction, further enhancing

LPO and ferroptotic cell death. It has also been reported to

suppress the expression of ferroptosis-protective proteins,

including GPX4 and SLC7A11. Since GPX4 plays a critical role in

detoxifying lipid peroxides, its downregulation results in the

accumulation of toxic lipid peroxides (163–165). The role of LPO activation in

ferroptosis-based therapy in cancer is summarized in Fig. 2.

Nonetheless, a major limitation of this approach

lies in the complexity and heterogeneity of lipid metabolism across

different tumor types. Some cancers may evade ferroptosis by

enriching their membranes with monounsaturated fatty acids instead

of PUFAs, reducing LPO susceptibility. Furthermore, the frequent

mutation of p53 in cancer cells can impair its ability to activate

pro-ferroptotic axis pathways, further complicating treatment

efforts.

Direct ferroptosis inducers

System Xc− inhibitors

Erastin is a small molecule compound capable of

inducing ferroptotic cell death by binding to and irreversibly

inhibiting the SLC7A11 subunit of System Xc− antiporter.

This inhibition reduces cystine uptake, resulting in diminished GSH

biosynthesis. Without GSH, GPX4 becomes non-functional, allowing

toxic lipid ROS to accumulate within the cell, causing oxidative

stress and ultimately, ferroptosis. Additionally, erastin has been

shown to interact with voltage-dependent anion channels on the

outer membrane of mitochondria, further contributing to ROS

production (166). In various

cancer types, including HCC, erastin sensitizes cells to

ferroptosis and shows promise as a potent anticancer therapeutic.

However, its clinical utility is limited to poor solubility,

metabolic instability and potential toxicity to healthy tissues,

particularly the kidneys (167).

To address these challenges, researchers are developing erastin

analogs and exploring advanced delivery systems, such as

nanotechnology and exosome-based encapsulation (168).

SAS, another ferroptosis inducer, similarly blocks

cystine uptake and inhibits GPX4. Nevertheless, its use in cancer

therapy is constrained by significant off-target effects, including

inhibition of the NF-KB signaling pathway and alterations in immune

cell function, which may raise concerns about safety and

specificity. These mechanisms of action are summarized in Fig. 2.

GPX4 inhibitors

When cancer cells develop resistance to System

Xc− inhibitors, targeting downstream effectors such as

GPX4 becomes a valuable alternative. RSL3 and ML162 are small

molecule inhibitors that directly bind to the Sec active site of

GPX4, blocking its lipid peroxide-reducing activity. As a result,

PUFAs undergo unchecked peroxidation, ultimately stimulating

ferroptosis (169). Although

structurally distinct, RSL3 and ML162 function in a similar fashion

and thus share similar limitations, including chemical instability

and broad off-target effects that may hinder regular cell function,

especially in neurons and kidneys. Much like the System

Xc− inhibitors, GPX4 inhibitors also suffer from low

solubility and rapid inactivation. Additionally, cancer cells may

develop resistance by altering membrane lipid composition to reduce

PUFA content and limit the effects of both RSL3 and ML162, or by

upregulating ferroptosis-suppressing proteins. One such protein is

FSP1, which is overexpressed in some cancers. FSP1 acts as an

oxidoreductase that generates reduced CoQ10, thereby preventing LPO

through a pathway parallel to the GSH/GPX4 axis. In a mouse model

using ferroptosis-resistant H460 lung cancer cell xenografts, FSP1

inhibition leads to significant tumor suppression in both GPX4

knockout and GPX4 KO/FSP1 groups (170). The aforementioned therapeutic

mechanisms are summarized in Fig.

2.

Regulatory RNAs: miRNAs, long

non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs)

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNA) are an increasingly

interesting topic for researchers as they have recently been shown

to regulate ferroptosis in cancer cells, having both stimulating

and inhibitory effects depending on the nature of the ncRNA. For

instance, miRNAs have been identified to target either SLC7A11 or

GPX4 and enhance or suppress ferroptosis (171). Other miRNAs may target the p53

signaling pathway or even regulate lipid metabolism and are capable

of greatly enhancing cell sensitivity to ferroptosis. It has been

recently reported that miR-302a-3p interacts with the

3′-untranslated region of FPN 1 and directly enhances ferroptosis

in NSCLC by inhibiting cellular iron export (172). Furthermore, lncRNAs also regulate

post-translational modifications of RNA-binding proteins through

numerous various mechanisms: Ubiquitination, acetylation and

phosphorylation. These modifications both directly and indirectly

modulate ferroptosis by affecting levels of specific protein

expression and degradation, notably the SLC7A11 protein (173). Finally, circRNAs may also play a

pivotal role in modulating ferroptotic sensitivity, as they often

act as sponges for miRNAs, stabilizing them and keeping them from

reaching their targets (174). In

a previous study, a specific circRNA, circ0097009, was found to be

overexpressed in HCC serving as a sponge for miR-1261, whose target

is the SLC7A11 subunit. Knockout of circ0097009 lead to decreased

expression of SLC7A11, inactivation of GPX4 and a decrease in

GSH/GSSG ratio, all of which result in increased sensitivity to

ferroptosis (175). Additionally,

some circRNA may sponge miRNA that would normally inhibit

ferroptosis. A recent study reported that exogenous delivery of

circBNC2 lead to increased LPO and ROS levels in prostate cancer,

greatly increasing cell sensitivity to ferroptosis by inhibiting

microRNA-4298 (176).

Combination therapy approaches

Synergy with chemotherapy

Currently, several effective strategies have been

identified to reverse tumor resistance, primarily by targeting iron

and lipid metabolism, two key regulators to ferroptosis (64). A major contributing factor to drug

resistance is the suppression of ferroptosis-related genes and

signaling pathways in tumor cells (177). For instance, clinical agents such

as artesunate have been shown to act synergistically with

sorafenib, enhancing its antitumor efficacy (178). Likewise, co-administration of

ursolic acid with sorafenib enhances its therapeutic effect

(179).

In the context of iron metabolism, a correlation

between tumor drug resistance and TFR expression has been recently

suggested, with evidence indicating that the downregulation of TFR

can help overcome resistance (180). In multiple myeloma cells, elevated

ferritin levels are considered to be associated to bortezomib

resistance, while iron supplementation promotes cell death. By

contrast, a reduction in ferritin has been shown to sensitize tumor

cells to bortezomib (181).

Additionally, miR-133a has been found to downregulate the ferritin

light chain subunit in cisplatin- and doxorubicin-resistant breast

cancer cells, increasing their sensitivity to the drugs (182). A summary of these mechanisms is

provided in Fig. 2.

In terms of lipid metabolism, cells with high GSH

expression levels and upregulation of the SCL7A11 light chain

subunit of System Xc− have been linked to resistance to

both radiation and chemotherapy (183). Moreover, numerous cancer cells

develop a dependency on the GPX4 enzyme, which contributes

massively to its acquired drug resistance. Loss of GPX4 function

renders cells more susceptible to ferroptosis and has been shown to

prevent tumor relapse in mouse models (184).

Synergy with radiation therapy

Radiation therapy may induce ferroptosis by

promoting oxidase activity via the production of highly reactive

hydroxyl radicals (185). It

triggers ferroptosis through three primary mechanisms: Producing

excess ROS that drive LPO, upregulating ACSL4 expression to enhance

polyunsaturated phospholipid biosynthesis, and depleting GSH,

thereby inhibits the protective effects of GPX4 against LPO

(61,186).

Tumor sensitivity to radiation therapy can be

increased by combining radiation therapy with ferroptosis inducers.

For example, class I FINs such as erastin and SAS inhibit cystine

uptake, while class II FINs like RSL3 and ML162 directly inhibit

GPX4. Class III FIN, such as FIN56, degrade GPX4 and deplete CoQ10

(64). Research indicates that the

combination of radiation therapy with ferroptosis inducers

significantly increases the radiosensitivity of NSCLC, yielding

improved outcomes than radiotherapy alone (187). Among the different classes of

FINs, class I FINs show the most promising synergistic effect with

radiotherapy, particularly through targeting SLC7A11. By contrast,

class II and III FINs face limitations due to poor pharmacokinetics

and higher cytotoxicity, which reduce their overall therapeutic

benefit in combination treatments (185). A summary is illustrated in

Fig. 2.

Synergy with immunotherapy

Emerging research suggests potential therapeutic

interplay between ferroptosis and immunotherapy. CD8+ T

cells secrete interferon-γ which in turn inhibits expression of

both the SLC7A11 and SLC3A2 subunits of the System Xc-, sensitizing

the cell to ferroptotic death (188). In turn, the lysed tumor cells

release damage-associated molecular patterns as well as LPO

products, enhancing recruitment of T-cells in a positive-feedback

manner to amplify antitumor immunity (189). Furthermore, with the rise of

immune checkpoint inhibitors as a viable therapeutic avenue,

combining both ferroptosis inducers with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies

greatly enhance the antitumor response by reversing immune

suppression within the tumor microenvironment (190). In a recent study, mefloquine, an

antimalarial, was revealed to not only induce ferroptosis in

melanoma and lung cancer cells, but also sensitize them to both

ferroptosis and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy when combined with

T-cell-derived interferon-γ. Mefloquine was reported to

significantly upregulate LPCAT3, a key gene in LPO-associated

ferroptosis, highlighting how LPO can also boost the efficacy of

checkpoint blockade immunotherapy (191). The combined effective delivery of

both ferroptosis inducers as well as immune checkpoint inhibitors

remains a significant hurdle, as much of recent research focuses on

optimizing efficient delivery to maximize antitumor effects

(192,193).

Synergy with nanotherapy

Ferroptosis-based nanotherapies are currently under

development as a promising approach in cancer treatment.

Nanomaterials used in this context are generally categorized as

either iron-based or non-iron based (64). Iron-based nanoparticulate materials

can induce ferroptosis by releasing iron at the tumor site, where

it catalyzes the Fenton reaction to generate ROS (194). These nanoparticles can also be

engineered to carry ferroptosis inducers or chemotherapeutic

agents, such as erastin, to circumvent its poor solubility and

off-target effects (168,195).

Iron free or non-iron based nanotherapies operate

through alternative mechanisms, such as delivering lipids,

non-coding RNAs, or ferroptosis-inducing compounds (196). For instance, nanoparticle

formulations can supplement PUFAs, modulating LPO and promoting

ferroptosis in tumor cells (197).

Additionally, tumor cells release exosomal PD-L1, which suppresses

T-cell activity, blocking immune checkpoint responses, and

contributing to therapy resistance (198). By combining exosome inhibitors

with ferroptosis inducers into a single nanotherapeutic unit,

researchers aim to harness both immune activation and ferroptotic

cell death. This strategy represents a novel and promising

direction in immunotherapy (187).

Despite their potential, ferroptosis-based nanotherapies remain

largely experimental. Further research, optimization and clinical

validation are needed to fully realize their therapeutic potential

in cancer treatment. A summary of these strategies is presented in

Fig. 2.

Discussion

Accumulation of ROS and LPO, resulting from an

imbalance in the cellular redox system, can trigger ferroptosis, a

form of programmed cell death. Over time, different tumor types

have become more aggressive and resistant to conventional therapies

such as surgical resection and chemotherapy, leading to poor

prognosis. Given the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells, it

is expected that, over the course of repeated treatment, some will

acquire mutations that confer resistance, mirroring the principles

of natural selection, where the fittest variants survive.

The emergence of drug-resistant tumors remains a

major challenge in oncology. However, since the initial discovery

of ferroptosis, mounting evidence has supported its potential as an

effective antitumor mechanism. Inhibition of key components of the

GPX4/GSH/System Xc− axis, along with related pathways

such as the mevalonate and trans-sulfuration pathways, has

demonstrated the ability to induce ferroptosis in various cancer

models.

Although clinical data on ferroptosis induction

remain limited, they are steadily increasing. For example, SAS,

which inhibits system Xc−, is currently being tested

against solid tumors and glioblastoma in clinical trials

(NCT04205357). Moreover, carbon nanoparticle-loaded iron

[CNSI-Fe(II)] is under clinical investigation as a

ferroptosis-inducing therapy for patients with advanced solid

tumors (NCT06048367).

Despite these promising findings, translating

preclinical results into clinical practice has been hindered by

challenges such as poor pharmacokinetics and significant side

effects observed with classical inducers. For instance, erastin

exhibits poor solubility and metabolic stability as observed in a

mouse liver microsome assay and, upon intraperitoneal

administration in mice, induces ferroptosis-associated alterations

in multiple organs, indicating potential toxicity to normal tissues

(167). Moreover, RSL3 at

tumoricidal doses is cytotoxic to normal cells such as neurons

(199), fibroblasts (200) and nephrocytes (201) and shows poor selectivity and

pharmacokinetics due to covalent binding to GPX4 via a reactive

alkyl chloride moiety (202).

Therefore, future studies should focus on enhancing

drug distribution, reducing systemic toxicity, and improving the

pharmacokinetics of currently used ferroptosis inducers. Moreover,

just as tumors evolve resistance to chemotherapy, they may also

adapt to evade ferroptosis. For example, prolonged treatment with

sorafenib has been associated with the overexpression of

resistance-related genes (203),

highlighting the need to understand the mechanisms underlying

acquired ferroptosis resistance and tumor heterogeneity.

To address these challenges, efforts are ongoing to

develop combination therapies, ranging from nanotechnology-based

approaches that improve drug solubility and reduce resistance

(204), to co-treatment with

traditional compounds such as artesunate alongside ferroptosis

inducers targeting the GPX4/GSH/System Xc− axis.

Additional strategies involve disrupting aberrant iron or lipid

metabolism in tumor cells to indirectly destabilize redox balance

and promote ferroptotic cell death.

Looking ahead, future research should prioritize

establishing rational combination regimens that optimize efficacy

and identifying predictive biomarkers to stratify patients most

likely to respond to ferroptosis-based therapies. Ultimately,

translating this promising strategy from bench to bedside will

require the development of next generation ferroptosis inducers

with enhanced selectivity and safety profiles, alongside

longitudinal clinical investigations to evaluate long-term

outcomes.

Recently, ferroptosis has been the focus of

numerous reviews, spanning both broad and disease-specific

perspectives. Broad overviews, such as those by Singh et al

(205), Ojo et al (206) and Ubellacker et al

(207) survey the underlying

mechanisms and general therapeutic potential of ferroptosis. By

contrast, disease-focused reviews include Hino et al

(208) on liver disease and HCC,

Meng et al (209) on

melanoma, Hsu et al (210)

on exosomal ncRNAs in lung cancer, and Chen et al (211) on digestive cancers and therapy

resistance. While collectively informative, these reviews are

either mechanistic surveys at a broad level or limited to single

cancer contexts, leaving a gap for integrative perspectives that

explicitly connect ferroptosis mechanisms to therapeutic resistance

across multiple malignancies.

By contrast, the present review employs a focused

yet comparative approach. In particular, HCC was selected, a cancer

well-characterized in ferroptosis research, and bladder cancer,

where ferroptosis is comparatively understudied, as representative

models. This dual focus enables us to merge well-established and

emerging findings, highlight research gaps and outline directions

for future research. In addition, rather than examining molecular

regulators in isolation as previous reviews have, our approach

associates iron metabolism, antioxidant defenses and LPO with drug

resistance, presenting a translational framework that bridges

molecular insights with clinical applications. Finally, the present

review evaluates therapeutic strategies, including monotherapies

such as ferroptosis inducers and regulatory RNAs, and synergistic

combinations with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and

nanotherapy. Collectively, these points underscore the novel

insights and distinctive contribution of our manuscript relative to

prior reviews.

In conclusion, the present review highlights the

promising potential of combination therapies aimed at inducing

ferroptosis as a novel approach for cancer treatment, particularly

in drug-resistant tumors. Combining ferroptosis inducers with

existing treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy and more

recently, nanotherapy, has shown encouraging results. Nonetheless,

further research is necessary given that most studies to date are

relatively recent and primarily conducted in xenograft models. In

summary, current findings suggest that targeting pathways involved

in iron metabolism, lipid metabolism and the GPX4/GSH/System

Xc− axis holds significant therapeutic promise. As

research in this field progresses, ferroptosis-based combination

strategies continue to emerge as a compelling new avenue for cancer

therapy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

NM drafted the initial manuscript. NEJ restructured

the manuscript's organization and ideas, created the figures and

table, and performed proofreading. RAH and MES wrote the final

draft and edited the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the artificial intelligence

tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate

content of the present manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AA

|

arachidonic acid

|

|

ABCC5

|

ATP-binding cassette subfamily C

member 5

|

|

ACSL4

|

acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family

member 4

|

|

AdA

|

adrenic acid

|

|

AML

|

acute myeloid leukemia

|

|

ATF4

|

activating transcription factor 4

|

|

BCAT2

|

enzyme branched-chain amino acid

transferase 2

|

|

BH4

|

tetrahydrobiopterin

|

|

CD36

|

cluster of differentiation 36 or

fatty acid translocase

|

|

circRNA

|

circular RNA

|

|

CoQ10

|

Coenzyme Q10

|

|

COX

|

cyclooxygenase

|

|

DHODH

|

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase

|

|

DMT1

|

divalent metal transporter 1

|

|

FATP

|

fatty acid transporter

|

|

FSP1

|

ferroptosis suppressor protein 1

|

|

FTH1

|

ferritin heavy chain 1

|

|

GCH1

|

guanosine-5′-triphosphate

cyclohydrolase-1

|

|

GCL

|

glutamate-cysteine ligase

|

|

GSH

|

reduced glutathione

|

|

GSSG

|

oxidized glutathione

|

|

GSTZ1

|

glutathione S-tranferase zeta 1

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

HIC1

|

HIC ZBTB transcriptional repressor

1

|

|

HMGCR

|

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA

reductase

|

|

HNF4α

|

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α

|

|

HO-1

|

heme oxygenase 1

|

|

HSC

|

hematopoietic stem cell

|

|

HSPA5

|

heat shock protein family A (Hsp70)

member 5

|

|

LD

|

lipid droplets

|

|

lncRNA

|

long-non-coding RNA

|

|

LOX

|

lipoxygenase

|

|

LPCAT3

|

lysophosphatidylcholine

acyl-transferase 3

|

|

LPO

|

lipid peroxidation

|

|

MDA

|

malondialdehyde

|

|

miRNA

|

microRNA

|

|

NCOA4

|

nuclear receptor coactivator 4

|

|

ncRNA

|

non-coding RNA

|

|

NRF2

|

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

OTUB1

|

OTU deubiquitinase

|

|

POR

|

cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase

|

|

PSAT1

|

phosphoserine aminotransferase 1

|

|

PSTK

|

phosphor-seryl-tRNA kinase

|

|

PUFAs

|

polyunsaturated fatty acids

|

|

Rb

|

retinoblastoma

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

SAS

|

sulfasalazine

|

|

Sec

|

selenocysteine

|

|

TFR1

|

transferrin receptor 1

|

|

TNBC

|

triple-negative breast cancer

|

References

|

1

|

Sharma A, Boise LH and Shanmugam M: Cancer

metabolism and the evasion of apoptotic cell death. Cancers

(Basel). 11:11442019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM and Yang

WS: Ferroptosis: An Iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death.

Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams

JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, Alnemri ES, Altucci L, Amelio I, Andrews

DW, et al: Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of

the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ.

25:486–541. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Čepelak I, Dodig S and Dodig DČ:

Ferroptosis: Regulated cell death. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol.

71:99–109. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Debela DT, Muzazu SG, Heraro KD, Ndalama

MT, Mesele BW, Haile DC, Kitui SK and Manyazewal T: New approaches

and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE

Open Med. 9:205031212110343662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kishi Y, Hasegawa K, Sugawara Y and Kokudo

N: Hepatocellular carcinoma: Current management and future

development-improved outcomes with surgical resection. Int J

Hepatol. 2011:7281032011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yiannikourides A and Latunde-Dada GO: A

short review of iron metabolism and pathophysiology of iron

disorders. Medicines (Basel). 6:852019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Camaschella C, Nai A and Silvestri L: Iron

metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era.

Haematologica. 105:260–272. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhao Z: Iron and oxidizing species in

oxidative stress and Alzheimer's disease. Aging Med (Milton).

2:82–87. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kotla NK, Dutta P, Parimi S and Das NK:

The role of ferritin in health and disease: Recent advances and

understandings. Metabolites. 12:6092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Knovich MA, Storey JA, Coffman LG, Torti

SV and Torti FM: Ferritin for the clinician. Blood Rev. 23:95–104.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Abbaspour N, Hurrell R and Kelishadi R:

Review on iron and its importance for human health. Iran J Pediatr.

19:164–174. 2014.

|

|

13

|

Fillebeen C, Charlebois E, Wagner J,

Katsarou A, Mui J, Vali H, Garcia-Santos D, Ponka P, Presley J and

Pantopoulos K: Transferrin receptor 1 controls systemic iron

homeostasis by fine-tuning hepcidin expression to hepatocellular

iron load. Blood. 133:344–355. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Obeagu EI and Tanko MSM: Iron metabolism

in breast cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications: A

narrative review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 87:3403–3409. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Singh B, Arora S, Agrawal P and Gupta S:

Hepcidin: A novel peptide hormone regulating iron metabolism. Clin

Chim Acta. 412:823–830. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Nemeth E and Ganz T: The role of hepcidin

in iron metabolism. Acta Haematol. 122:78–86. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shan Z, Wei Z and Shaikh ZA: Suppression

of ferroportin expression by cadmium stimulates proliferation, EMT,

and migration in Triple-negative breast cancer cells. Toxicol Appl

Pharmacol. 356:36–43. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Belvin BR and Lewis JP: Ferroportin

depletes iron needed for cell cycle progression in head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 12:10254342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Grillo AS, SantaMaria AM, Kafina MD,

Cioffi AG, Huston NC, Han M, Seo YA, Yien YY, Nardone C, Menon AV,

et al: Restored iron transport by a small molecule promotes

absorption and hemoglobinization in animals. Science. 356:608–616.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Skjørringe T, Burkhart A, Johnsen K and

Moos T: Divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) in the brain:

Implications for a role in iron transport at the blood-brain

barrier, and neuronal and glial pathology. Front Mol Neurosci.

8:192015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Song Q, Peng S, Sun Z, Heng X and Zhu X:

Temozolomide drives ferroptosis via a DMT1-dependent pathway in

glioblastoma cells. Yonsei Med J. 62:8432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|