Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is one of the

leading causes of cancer-related mortalities globally and accounts

for ~85% of all lung cancer cases (1). Among the molecular subtypes of NSCLC,

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutations are one

of the most commonly identified oncogenic drivers. These mutations

are commonly prevalent in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and are

strongly linked with smoking and environmental carcinogens

(2). KRAS is a member of the rat

sarcoma viral (RAS) oncogene family and accounts for the majority

of RAS-related mutations encountered in human cancer. KRAS

alterations account for ~85% of all RAS mutations (3). The prevalence of KRAS mutations varies

across cancer types, with the highest frequencies found in

pancreatic (88%), colorectal (45–50%) and lung cancer (31–35%)

(4). KRAS mutations are present in

~30% of LUAD cases in Western populations and ~10% of in Asian

populations (5,6).

The KRAS proto-oncogene encodes a small guanine

triphosphate (GTPase) that acts as a binary switch in signal

transductions of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases, such as

mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), epidermal growth factor

receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), thus

regulating cellular functions such as proliferation,

differentiation and survival. KRAS is a clonal transforming

oncogene and is a key oncogenic driver across multiple solid tumors

(7–9).

Structurally, KRAS is a 21-kDa GTPase composed of a

conserved G-domain and two dynamic regulatory regions, Switch I and

Switch II, which control its active (GTP-bound) and inactive

(GDP-bound) states. The Switch II pocket (SII-P) forms the

allosteric site targeted by KRAS G12C inhibitors, while C-terminal

farnesylation enables its anchoring to the plasma membrane

(10,11).

The prevailing outlook on the poor prognosis and

limited treatment options for NSCLC has significantly shifted over

the last 2 decades due to the development of targeted therapy,

molecular profiling and immunotherapy (12,13).

Although several preclinical and clinical studies have investigated

RAS inhibitors, no authorized treatments directly inhibit mutant

variants of KRAS or its downstream signaling (14,15).

These novel KRAS inhibitors are currently being investigated in

combination with other therapies, which may significantly improve

the treatment of KRAS-mutated NSCLC. Targeted therapy and

immunotherapy have shown promising results in treating NSCLC,

therefore the present review explored novel treatment strategies

and their efficacy in targeting the KRAS mutation in NSCLC.

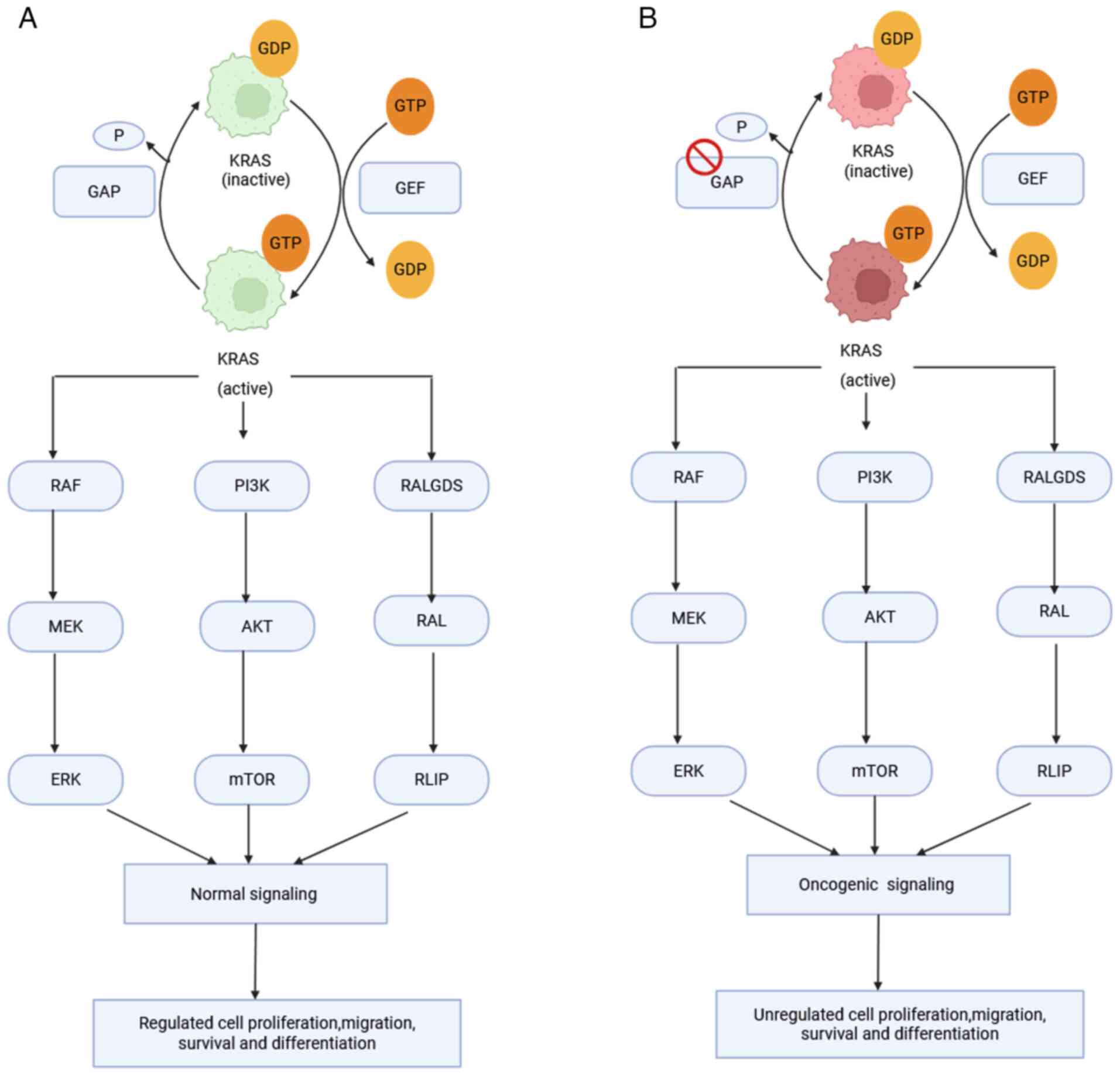

KRAS is a key proto-oncogene that encodes a small

GTPase that controls cell survival, differentiation and

proliferation by acting as a molecular switch in important cellular

signaling cascades (3). The GTPase

cycles between an inactive GDP-bound and an active GTP-bound state.

Activation is promoted by guanine nucleotide exchange factors

(GEFs), which stimulate GDP-GTP exchange, such as SOS1 and the

GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs); for example, neurofibromin 1 is

a GAP that accelerates GTP hydrolysis to inactivate KRAS (14,16).

Multiple downstream effectors of KRAS, primarily,

are part of the RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway. Activated KRAS-GTP

recruits RAF kinases to the membrane, which promotes RAF

dimerization and activation. RAF phosphorylates MEK1/2, leading to

activation of ERK1/2. Upon activation, nuclear translocation of ERK

occurs and targets transcription factors, including E26

transformation-specific family, serum response factor and ribosomal

S6 kinase, to influence cell proliferation, differentiation and

migration. Furthermore, KRAS stimulates phosphoinositide 3-kinase

(PI3K), leading to AKT activation that promotes cell survival,

metabolism and growth. KRAS also activates RalGEFs, which regulate

cytoskeleton remodeling, membrane dynamics and vesicle trafficking

(Fig. 1) (14,16,17).

In its wild-type state, KRAS participates in normal cell signaling

but does not directly suppress immune responses. KRAS mutations;

however, it inhibits T-cell activity by stimulating an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) through the

induction of cytokine-(such as IL-6) and chemokine-(such as IL-8)

driven inflammation and immune evasion, and increase programmed

cell death-1 ligand (PD-L1) expression levels via activation of the

MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways, resulting in immune escape (14,18).

KRAS mutations are clinically significant in NSCLC

due to their frequency, prognostic implications and impact on

treatment decisions (19,20). Point mutations commonly deregulate

the KRAS gene, resulting in an inherently active GTP-bound phase

and activating downstream oncogenic signaling pathways (21–23).

KRAS mutation frequency is lower (~5%) in squamous NSCLC and higher

(20–40%) in LUAD (24).

Furthermore, these mutations are more prevalent in Western

populations compared with Asian populations (26 vs. 11%) and in

smokers compared with non-smokers (30 vs. 11%); the presence of

KRAS mutations in NSCLC is closely associated with smoking

(25). Furthermore, KRAS mutations

are more common in female and younger patients, according to a

pooled study of resected NSCLC tumors; however, only the

association with younger patients was significant in the

multivariate analysis (P=0.044) conducted (26,27).

The previous study by Shepherd et al (27) on the frequency of KRAS mutations did

not include any analysis specific to histology or race. Smoking is

suggested to leave a particular molecular mark on KRAS gene since

point mutations (G12C and G12V) are often detected in former or

current smokers; by contrast, transitional mutations (G12D) are

more common in non-smokers (28,29).

Furthermore, compared with individuals who have never smoked,

smokers often have substantially more complicated KRAS-mutant

tumors with a more considerable mutational burden and a higher

probability of significant co-occurring mutations in tumor protein

P53 (TP53) or serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11) (30).

Co-mutations, including STK11/LKB1, may influence

the prognosis of KRAS-mutant NSCLC. For example, ERK1/2

phosphorylation is more significant in tumors with KRAS G12C

mutations compared with those with KRAS G12D mutations, and this

enhanced MAPK signaling can be further amplified in the presence of

STK11/LKB1 loss, contributing to more aggressive tumor biology.

Supporting this, a previous study employing animal models driven by

KRAS mutations showed that the MEK inhibitor selumetinib was more

effective in KRAS G12C tumors compared with KRAS G12D tumors

(31). As a result, various KRAS

mutations may induce signal transduction cascades differently,

resulting in unique drug sensitivity profiles (32). Regarding co-occurring mutations,

LUAD is typically associated with KRAS single-driver mutations,

accounting for 95–99% of KRAS-mutant cases, while double mutants

(EGFR/ALK/BRAF and KRAS) are rare, occurring in <1% of cases

(33–35).

Approximately one-third of patients with LUAD have a

KRAS mutation; despite significant advancements in the discovery

and development of targeted therapeutics for molecular subtypes of

LUAD (36), no authorized

medication currently targets any KRAS mutation directly (37). For the past 40 years, significant

efforts have been made to develop medicines for KRAS. These

investigations have targeted the KRAS protein and its membrane

location, interactions between proteins, post-translational

modifications, and downstream signaling pathways; however, these

methods have not shown promising outcomes in clinical trials

(38,39).

Since KRAS has a restricted number of active binding

sites, complicated biochemistry (40) and a high affinity for GTP (41), direct targeting of the protein was

thought to be complex until ~5 years ago (42). Developments in crystallography and

computer modeling (43) have

identified small compounds that directly bind to the inactive

GDP-bound conformation of KRAS G12C within the SII-P, thereby

locking the protein in its inactive state and preventing downstream

signaling (44). However, the

binding affinity of these early-stage drugs would need to be

substantially increased before they can be used as effective

treatments. These early compounds demonstrated that RAS is

principally druggable; however, they lacked sufficient potency and

pharmacological properties to achieve clinical efficacy and often

lacked the precision required to target mutant KRAS effectively

(45)

Prior to the advent of direct KRAS inhibitors,

indirect strategies were investigated, such as by blocking KRAS

post-translational modifications, preventing its anchoring to the

cell membrane or disrupting the downstream signaling pathways it

controls (46–48). Early analyses focused on farnesyl

transferase inhibitors, salirasib and tipifarnib being tested to

prevent membrane anchoring of KRAS. Although the preclinical

activity was promising, the clinical efficacy of salirasib and

tipifarnib in NSCLC was limited due to compensatory prenylation

with geranylgeranyl transferase. In a phase II trial of salirasib

in KRAS-mutant LUAD, no objective responses were observed, although

30–40% of patients achieved temporary disease stabilization at 10

weeks (49,50).

Blockage of the downstream KRAS signaling has also

been investigated. Small molecules that target ERK and MEK decrease

effector phosphorylation and block RAF interactions in preclinical

models (45,51). Despite this, MEK inhibitor clinical

trials as monotherapy have been ineffective. In a phase II study of

previously treated patients with KRAS-mutant NSCLC, FAK inhibition

with defactinib alone had limited clinical activity [median

progression-free survival (PFS), 45 days], and activity was not

associated with TP53 or CDKN2A status (52).

These studies highlight the primary limitations of

indirect KRAS targeting: Biochemical redundancy, adaptive feedback

loops and toxicity due to effects on essential signaling pathways

(53). Post-prenylation processing

enzymes such as Ras-converting enzyme 1 and isoprenylcysteine

carboxyl methyltransferase remain potential targets, but inhibitors

lack specificity and risk broad systemic toxicity (54). However, these limitations are being

overcome through the development of pragmatic strategies. Combined

inhibition of farnesyl- and geranylgeranyl transferase has been

reported as a promising approach in models of pancreatic cancer,

although it has not been tested in LUAD (55). Epidemiological studies suggest that

oral bisphosphonate use is associated with a decreased risk of lung

cancer in non-smoker postmenopausal women (56) and a case report described regression

of hepatic metastases in primary lung adenocarcinoma following

zoledronic acid monotherapy (57).

Preclinical models indicate that these vulnerabilities are

subtype-specific: Mesenchymal-like KRAS-mutant NSCLC is sensitive

to combined FGFR-MEK inhibition, whereas epithelial-like tumors

preferentially respond to ERBB-MEK blockade (58). Such biomarker-led combination

strategies provide novel avenues for indirect targeting.

Collectively, these indirect approaches illustrate the innovative

nature of previous efforts to target KRAS and the associated

limitations, and demonstrate the importance of investigations on

direct interventions in the current therapeutic landscape.

The mutant KRAS G12C protein shows decreased

GAP-stimulated GTPase activity from biochemical analyses,

consistent with earlier G12X mutants (excluding G12P). In contrast

with other mutated KRAS proteins, the mutation KRAS G12C maintains

periodic intrinsic GTPase function and alternates among the active

KRAS-GTP and inactive KRAS-GDP states (59,60).

Structural analysis demonstrated that the KRAS Cys12 mutation is

proximal to a newly identified allosteric site, the SII-P, which is

transiently accessible in the GDP-bound state. This finding allowed

the design of covalent inhibitors to bind Cys12 irreversibly,

trapping KRAS G12C in its inactive state and ablating downstream

signaling (61,62). The first therapies to target this

SII-P were sotorasib, adagrasib and, more recently, garsorasib

(D-1553). These KRAS G12C inhibitors all bind covalently to the

SII-P but differ in their binding kinetics and molecular

interactions (63). Adagrasib

exhibits higher conformational mobility, allowing more sustained

binding to KRAS-G12C, while garsorasib has shown promising clinical

activity in NSCLC and colorectal cancer (64,65).

Structural scaffold differences between KRAS G12C inhibitors, such

as sotorasib and adagrasib, are likely responsible for the

different pharmacodynamic profiles and tissue penetration.

Although the SII-P is the most-validated and

extensively targeted allosteric site, it is not the sole structural

determinant of KRAS inhibitor binding; other regions of KRAS also

influence drug design and activity. KRAS contains key structural

regions, including the Switch I and Switch II domains and a

hypervariable region that regulates membrane attachment. The switch

I region can be indirectly modulated by inhibiting SOS1-KRAS

interactions using SOS1 inhibitors (such as BI-3406 and

BI-1701963). The nucleotide binding pocket has been the focus of

investigation with nucleotide competitive analogs and membrane

localization disrupted with FTase inhibitors through the

hypervariable region (66–68). These findings underscore that KRAS

contains several structural features beyond the SII-P that may be

exploited therapeutically.

The first KRAS G12C inhibitor studied in a clinical

trial for an advanced solid tumor was sotorasib. The initial

investigation was a CodeBreaK 100 phase I/II basket trial to

determine the safety and beneficial effects of sotorasib in

patients with advanced tumors with a KRAS G12C mutation,

particularly those who previously received standard treatment.

Based on the clinical trial outcome, sotorasib received approval

from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2021 to treat

advanced-stage NSCLC (69,70). In a cohort of 126 patients with KRAS

G12C mutation NSCLC, the objective response rate (ORR) was 37.1%,

with 3.2% exhibiting a complete response (CR). The median overall

survival (OS) was 12.5 months, median PFS was 6.8 months, and

adverse events were seen in 69.8% of patients (71). Another study found a 42.9% confirmed

ORR for 116 patients with KRAS G12C mutated NSCLC. the median OS

was 12.6 months and the median PFS and response duration were 6.5

and 8.5 months, respectively (72).

In a subsequent phase III trial comparing sotorasib and docetaxel,

sotorasib increased PFS [PFS, 5.6 months vs. 4.5 months for

docetaxel, hazard ratio (HR)=0.66, P=0.0017] in patients with NSCLC

who had previously received chemotherapy (73). The IFCT-2102 Lung KG12Ci study, a

nationwide study conducted in France, included 458 patients with

metastatic or advanced KRAS G12C-mutated non-squamous NSCLC across

76 centers. The median age was 65.8 years and 43.4% of the patients

were female. The majority (95.4%) were current or former smokers

and 38.0% had brain metastases at the initiation of sotorasib

therapy. The key efficacy endpoints were a median real-world PFS of

3.5 months and a median real-world OS of 8.3 months (median

follow-up was 15.8 and 16.4 months, respectively). The real-world

ORR was 35.5% and the disease control rate (DCR) was 63.7%. In the

subgroup of patients with brain metastases, the intracranial

real-world ORR was 20.1% and the intracranial real-world DCR was

66.9%. From a safety perspective, sotorasib was considered to be

tolerable. However, 16.5% of patients discontinued their therapy

because of adverse events, while 5.2% of patients experienced grade

3–4 hepatotoxicity (74).

Sotorasib changed the treatment landscape for KRAS

G12C-mutant NSCLC by providing improved clinical outcomes compared

with standard second-line therapies, such as docetaxel,

docetaxel-ramucirumab and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)

monotherapy. Nevertheless, the intracranial efficacy of sotorasib

is low, particularly in patients with brain metastases, and

survival benefits are limited due to the acquisition of resistance;

thus, there is an urgent need for mechanism-based combination

approaches and next-generation inhibitors. The clinical decision to

use sotorasib should be made with caution, particularly for

patients with KRAS G12C-mutant NSCLC with central nervous system

(CNS) involvement or a high disease burden.

Another KRAS G12C inhibitor with a positive clinical

record is adagrasib. The phase I/IB KRYSTAL-1 study of adagrasib

demonstrated a favorable safety profile and a median PFS of 11.1

months (75). KRYSTAL-12 (trial no.

NCT04685135), a phase III study of adagrasib vs. docetaxel in

patients with previously treated KRAS G12C-mutated NSCLC,

demonstrated that 94.0% of patients who received adagrasib and

86.4% of patients who received chemotherapy had treatment-related

adverse events (TRAEs). Grade ≥3 TRAEs occurred in 47.0% of

patients who received adagrasib and 45.7% of patients who received

docetaxel. These patients would have received immunotherapy before

receiving adagrasib (76).

The KRAS G12C inhibitor garsorasib showed strong

efficacy and tolerable safety in a phase II trial (trial no.

NCT05383898) of 123 Chinese patients with pre-treated KRAS

G12C-mutated NSCLC. All participants (median age, 64; 88% male)

were administered 600 mg garsorasib twice daily and achieved an ORR

of 50% (1 CR and 60 partial responses) and a DCR of 89%. With a

median follow-up of 12.3 months, the median PFS was 9.1 months and

the median OS was 14.1 months, the longest reported in

commercialized KRAS G12C inhibitors. TRAEs were seen in 95% of

patients, with grade ≥3 events (50%) mainly comprising hepatic

enzymes (AST elevation, 17%; ALT, 15%) and gastrointestinal

symptoms (nausea/vomiting, 2%); most toxicities were

dose-modifiable (77,78). Garsorasib has demonstrated promising

clinical activity with high response rates, durable responses and

prolonged OS in patients with previously treated KRAS G12C-mutant

NSCLC, and has shown superior outcomes compared with existing

inhibitors, in certain contexts as aforementioned. However,

widespread use and future studies with a larger sample size are

necessary to collect more data on CNS activity, long-term survival

and comparative effectiveness. Presently, the use of garsorasib may

be considered post-chemotherapy and ICI therapy, particularly in

patients with healthy liver function who can be closely monitored.

Further to the aforementioned studies, numerous other clinical

trials (Table I) are currently

under investigation to identify therapies with increased efficacy

of KRAS G12C inhibitors.

Clinical resistance continues to present a notable

barrier and commonly involves allosteric sites such as the SII-P.

Second-site mutations on or around the SII-P change pocket geometry

and/or local dynamic structures that directly disrupt inhibitor

binding (79). For example, Y96D

eliminates hydrogen bonding in the pocket, A59T, and G13D disrupts

the conformational state essential for drug interaction (80). Furthermore, bypass mechanisms of

resistance, including upstream mechanisms by amplifying the HER2

gene, can induce KRAS activation and reduce dependence on SII-P

inhibition (81). Taken together,

these findings show that the structural confirmation of the SII-P

influences inhibitor binding affinity, and demonstrates how

mutations in this region can lead to resistance. This close

association between the structure and function of KRAS underscores

the importance of combining strategies or developing

next-generation inhibitors to overcome these challenges, including

resistance.

Combining KRAS G12C inhibitors with ICIs is

supported by synergistic immunogenicity: Blocking KRAS can increase

tumor antigen presentation and T-cell infiltration, while ICIs

counteract immune suppression (62,82).

The KRYSTAL-7 trial (trial no. NCT04613596) is a phase III study

assessing first-line adagrasib in combination with pembrolizumab

compared with monotherapy pembrolizumab in patients with advanced

NSCLC with a KRAS G12C mutation. In patients with a PD-L1 tumor

proportion score ≥50%, the confirmed ORR was 63% [32/51 patients;

95% confidence interval (CI), 48–76%]. The DCR in the same subgroup

was 84% (43/51 patients; 95% CI, 71–93%). The median PFS at a

median follow-up of 10.1 months was not achieved (95% CI, 8.2

months to not evaluable). The TRAEs reported among the 148 patients

evaluated for safety led to permanent discontinuation of adagrasib

in 6% (n=9) and pembrolizumab in 11% (n=16) of patients with TRAEs;

4% (n=6) of patients discontinued both agents due to TRAEs

(83). The phase Ib 100/101

CodeBreaK study tested sotorasib in combination with pembrolizumab

or atezolizumab in patients with metastatic KRAS G12C NSCLC.

Although the combination demonstrated clinical activity (ORR,

~29%), numerous patients experienced severe grade 3–4

hepatotoxicity when starting both drugs concomitantly. A ‘sotorasib

lead-in’ dose introduction strategy markedly ameliorated severe

liver toxicity and reduced discontinuation of treatment,

underscoring the relevance of dosage sequence to enhance

tolerability (84). Presently, the

ongoing Krascendo-170 trial (trial no. NCT05789082) is evaluating

divarasib in combination with pembrolizumab sequentially, to

determine whether the treatment dose can be maximized without

losing an optimal balance between efficacy and toxicity in

frontline KRAS G12C-mutated NSCLC.

Combining KRAS G12C inhibitors with ICIs may

potentially improve efficacy, particularly in patients with

PD-L1-high tumors. Adagrasib has potential as a frontline

combination therapy, requiring clarification of the optimal order

and timing for administration. Future clinical plans should

individualize treatment according to tumor biology and immune

status, guided by direct comparison trials initiated through

biomarker-informed pathways.

The toxicities of KRAS G12C inhibitors (sotorasib

and adagrasib) are clinically relevant, although frequently

manageable with individualized approaches. In a prospective

biomarker study, 75% of patients with a history of immune-related

hepatitis from prior immunotherapy subsequently developed severe

hepatotoxicity with sotorasib (85). Nevertheless, attempts at dose

reduction and rechallenge were made in over half of cases, and

long-term rechallenge was successful in some patients using

corticosteroids. Similarly, gastrointestinal AEs (such as diarrhea,

nausea and vomiting) may be controlled with supportive medications

(such as antiemetics, antidiarrheals, hydration and dietary

changes), and therapy is typically held or dose adjusted for grade

≥3 events in the case of adagrasib. Liver toxicity may be managed

with regular liver enzyme monitoring and prompt dose modification.

These results highlight that while toxicities may restrict dosing,

personalized immunosuppression and dose adjustment interventions

can sustain therapeutic benefit in appropriate patients (86,87).

KRAS G12C inhibitors have presented a new era for

NSCLC treatment through direct targeting of KRAS, as both sotorasib

and adagrasib have shown significant clinical activity, and as well

as the more recent therapy, garsorasib. However, modest survival

benefits, low intracranial activity and a resistance mechanism

remain significant limitations. Continued work with rational

combinations, tailored sequencing with immunotherapy,

toxicity-mitigation approaches and the emergence of next-generation

inhibitors are necessary to sustain long-term responses and provide

further treatment options for patients with KRAS G12C tumors.

The lack of effective targeted treatment for

patients with non-G12C KRAS mutations in NSCLC is a notable

clinical issue, particularly considering the recent FDA approval of

KRAS G12C inhibitors. In contrast to G12C inhibitors, which

covalently trap the G12C-specific cysteine residue, non-G12C

mutations require alternative treatment strategies. Immune

profiling studies show that non-G12C mutations are often associated

with increased rates of PD-L1 negativity and STK11 co-mutations,

which are both predictors of poor response to ICIs (88–90).

By targeting pan-KRAS inhibition, TME modulation and

upstream and downstream signaling pathways, emerging strategies aim

to overcome limitations such as allele-specific resistance, pathway

redundancy, and adaptive signaling escape. Pan-RAS and RAS-GTP

inhibitors are being further developed, as they have demonstrated

activity against other KRAS mutations beyond G12C (88). The non-covalent inhibitors MRTX1133

and HRS-4642 disrupt KRAS G12D interactions with SOS1 or RAF1,

resulting in downstream MEK-ERK inhibition. MRTX1133 (trial no.

NCT05737706) has progressed to phase I clinical trials, and

HRS-4642 is in phase I/II trials (91), showing preclinical tumor growth

inhibition in vitro and in vivo (92).

Although tumor mutational burden (TMB) and PD-L1

expression levels are comparable in G12C and non-G12C subgroups,

clinical responses in non-G12C variants are unsatisfactory

(93). These tumors are frequently

associated with co-mutations such as STK11, which shape an

immune-cold microenvironment, contributing to poor response to ICIs

(90). Despite novel targeted

approaches, the therapeutic landscape for non-G12C mutations of

KRAS remains limited.

Due to the constraints of targeted approaches,

immunotherapy has become an essential alternative and complementary

treatment option, especially for KRAS-mutant NSCLC. Furthermore,

novel approaches such as combination regimens with KRAS pathway

inhibitors and ICIs are being explored, based on data that KRAS

mutations alter the immune microenvironment and response to ICIs

(89). These strategies highlight

the need for novel immunotherapeutic regimens and rational

combinations to improve outcomes for patients with non-G12C KRAS

mutations. Although emerging KRAS G12C inhibitors show potential,

patients with non-G12C KRAS mutations in NSCLC have limited options

for targeted therapy and respond poorly to immunotherapy because of

co-mutations and a cold tumor immune microenvironment. Novel

non-covalent KRAS inhibitors and combination approaches targeting

signaling pathways and immune modulation are emerging as promising

treatment options; however, further development of therapies

targeted at specific molecular and immune mechanisms is necessary

to improve outcomes for this complex cohort.

ICIs, combined with platinum-based chemotherapy or

alone, are the conventional first-line treatment for patients with

advanced KRAS mutation-positive NSCLC (94). Smoking has been associated with

elevated TMB in addition to the immune-related characteristics of

KRAS-mutant tumors. Increased TMB may correlate with an improved

response to ICIs (95,96). Mazieres et al (97) retrospectively analyzed NSCLC cases

with different oncogenic driver mutations and reported that

increased PD-L1 expression levels were observed in KRAS-mutant

tumors, which also showed superior responses to ICIs compared with

that of other oncogenic driver mutations such as EGFR, ALK, ROS1

and RET alterations. However, most phase III ICI trials in NSCLC

did not stratify patients by KRAS subtype, and only a few included

post-hoc analyses (98,99). Although KRAS G12C inhibitors have

shown benefit, other KRAS mutations still lack targeted options.

Table II summarizes key

immunotherapy trials in KRAS-mutant NSCLC.

The KEYNOTE-042 study is a phase III trial comparing

pembrolizumab to platinum-based chemotherapy as a first-line

treatment for patients with PD-L1-positive advanced NSCLC. KRAS

mutations, including NRAS mutations, were found in 22.9% (9.6% KRAS

G12C) of 301 patients; these patients exhibited increased levels of

tissue TMB and PD-L1 expression. In KRAS-mutant cohorts,

pembrolizumab treatment showed a significantly improved outcomes,

with an OS hazard ratio of 0.42 (95% CI, 0.22–0.81) and a PFS

hazard ratio of 0.51 (95% CI, 0.29–0.87) compared with KRAS

wild-type tumors (100). The

KEYNOTE-189 study, which examined the efficacies of first-line

platinum-based chemotherapy alone or combined with pembrolizumab in

advanced-stage NSCLC, reported that 12.8% of the 289 patients (95%

CI, 10.1–15.6%) had a KRAS G12C mutation, while 30.8% (95% CI,

22.9–38.8%) reported any KRAS mutation. Furthermore, tumors with

any KRAS mutation had elevated tissue TMB and PD-L1 levels.

Pembrolizumab-based treatment showed higher clinical outcomes

regardless of KRAS status than chemotherapy alone in PFS, OS and

ORR (101). These trials indicate

that KRAS-mutated NSCLC, particularly KRAS G12C, have an enhanced

response to pembrolizumab and immunotherapy due to high-level

expression of PD-L1 and TMB. Pembrolizumab, alone or combined with

chemotherapy, could result in survival and progression-free

benefits for these patients vs. chemotherapy alone.

A retrospective study conducted in China showed that

immunotherapy-based treatment in patients with KRAS-mutant NSCLC

showed improved results compared with that of chemotherapy alone.

The immunotherapy regimens used in this cohort were PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors either alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

Overall, the median OS was 22.9 months (95% CI, 14.1–31.7) and PFS

was 9.4 months (95% CI, 6.6–12.1). Immunotherapy regimens had a

median OS of 45.2 vs. 11.3 months (P=1.81E-5) and a median PFS of

10.5 vs. 8.2 months (P=0.706) compared with chemotherapy. The first

line therapy cohort demonstrated a median OS and median PFS of 33.5

vs. 16.1 months (P=0.010) and 32.2 vs. 6.9 months (P=0.00038),

respectively. In the second line therapy cohort, median OS was not

reached vs. 9.23 months (P=0.026) and median PFS was 10.8 vs. 5.5

months (P=0.010). Immunotherapy improved the median OS compared

with that of chemotherapy for both patients with KRAS G12C tumors

and those with non-KRAS G12C tumors, according to subgroup analysis

(G12C, 25.2 vs. 9.1 months, P=0.0037; non-G12C, not reached vs.

25.7 months, P=0.020). In addition, concurrent KRAS/TP53 mutants

also showed an improved median OS with immunotherapy-based regimens

compared to those who received chemotherapy (33.5 vs. 11.8 months;

P=0.036). These findings suggest that immunotherapy is beneficial

for OS relative to chemotherapy in patients with late-stage

KRAS-mutant NSCLC, regardless of the treatment line or KRAS

mutation subtype (102).

Recent studies have provided novel insights into the

role of immunotherapy in KRAS-mutant NSCLC. A retrospective

analysis was conducted in Italy with a cohort of 143 patients with

advanced NSCLC and KRAS mutations received ICIs, with or without

chemotherapy. The most frequent KRAS mutation was G12C (41%),

followed by G12V (23.7%) and G12D (11.8%); ≥50% of the patients

received ICIs as monotherapy, while the rest had it in combination

with chemotherapy, mainly as a first-line therapy. The OS or PFS

among the KRAS subgroups showed no significant differences. By

contrast, patients with KRAS Q61, 13X and G12C mutations had a

relatively longer OS (46.5, 31.8 and 28.7 months, respectively) of

the KRAS subgroups analyzed. The KRAS G12D cohort showed the most

improved response to treatment with an (ORR) of 73%, largely driven

by patients with stable disease (40%), which was greater for

chemoimmunotherapy. The median duration of response (DOR) was 7.4

months overall, with the longest DOR at 10.2 months seen in G12V.

Co-mutations were also assessed: STK11 was present in 24% of cases

and TP53 in 29%. Patients with STK11 co-mutations tended towards

more prolonged OS (39.7 months) compared with those without STK11

co-mutations (26.1 months). By contrast, TP53 co-mutations were

associated with a shorter OS (19.1 months), although the analysis

did not reach statistical significance. Notably, bone metastases

were associated with lower survival and almost doubled the risk of

death (HR, 2.81; P<0.001) (103). However, the analysis was

retrospective, single institution-based, underpowered and the

treatment strategies were heterogeneous, which limited the strength

and external validity of the results. Furthermore, the negative

association between STK11 co-mutations and improved survival is in

contrast to numerous previous findings (104,105) and may be a cohort-specific

artifact. Therefore, the aforementioned study requires further

validation in larger, homogeneously treated cohorts.

A multicenter retrospective study compared

first-line programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 inhibitors

(n=78) vs. platinum-based chemotherapy (n=29) in metastatic

KRAS-mutant NSCLC. The PFS was significantly longer in the

immunotherapy group (7.9 vs. 6.0 months; P=0.030), although there

were no differences in the median OS (16.2 vs. 19.2 months;

P>0.05). Positive PD-L1 status was associated with an improved

PFS, whereas increased CRP, CEA and NLR levels were associated with

poor outcomes. It was also suggested that PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors may

achieve more robust disease control, particularly in PD-L1-positive

patients, using inflammatory parameters such as C-reactive protein

(CRP), Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

ratio (NLR) as potential prognostic values (106).

Immunotherapy, particularly in combination with

chemotherapy, markedly prolongs survival for advanced KRAS-mutant

NSCLC over chemotherapy alone; this is greater among patients with

PD-L1-positive tumors or high tumor mutational burden. KRAS G12C is

the predominant subtype and exhibits notable responsiveness to

ICIs, providing evidence for ICIs-based chemoimmunotherapy as the

optimal first-line treatment.

Co-mutations in STK11, TP53 and KEAP1 determine the

characteristic phenotype of the TME and clinical prognosis for

KRAS-mutant NSCLC. KRAS/TP53 tumors have an immune-inflamed profile

with high TMB (10–12 mutations/Mb), high PD-L1 expression (≥50%)

and dense CD8+ T-cell infiltration, which supports an

improved response to ICIs (107).

In a pooled analysis of 713 patients, KRAS/TP53 cases had

significantly higher benefit from ICIs compared with chemotherapy,

with an OS HR of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.55–0.92) and interaction HR of

0.53–0.56 favoring immunotherapy (108,109). Thus, KRAS/TP53 cases had

significantly higher benefit from ICIs when compared with that of

chemotherapy.

By contrast, KRAS/STK11 tumors are more consistently

characterized by non-inflamed immune-cold with low PD-L1 expression

(<10%), minimal CD8+ cell infiltration and a TMB of

4–6 mutations/Mb. Poor responses to ICIs and chemoimmunotherapy

suggest the clinical manifestation of this (110). Numerous studies have shown that an

STK11 co-mutation is associated with worse PFS and OS relative to

KRAS-only or KRAS/TP53 disease, which often translates to the level

of benefit derived from chemotherapy alone (111–113). These mutations also significantly

correlated with worse PFS (4.2 months vs. 11.0 months; HR, 2.2; P

< 0.01) and OS (9.8 months vs. NR; HR 2.6; P<0.01). Although

there are conflicting data as to their effects on KRAS G12C

inhibitor efficacy, with some studies showing reduced responses and

others reporting similar outcomes regardless of STK11 status, the

prognosis for patients with KRAS/STK11 co-mutations remains poor

(114–116). This highlights the necessity for

novel single and combination strategies in KRAS/STK11 disease, as

standard chemo-immuno-oncology regimens offer limited benefit.

KRAS/KEAP1 tumors are the most aggressive subtype

and possess infrequent broad resistance to chemotherapy, ICIs and

KRAS-targeting agents. KEAP1/NFE2L2 mutations are associated with

an inferior prognosis to platinum-pemetrexed and ICI regimens, as a

pooled analysis reported an HR of 1.96 (95% CI, 1.33–2.92) for

shorter survival (117). In the

KRYSTAL-1 study, patients with KEAP1 co-mutation had a

significantly shorter median PFS (4.1 months) and OS (5.4 months)

when treated with adagrasib in comparison with their wild-type

counterparts (9.9 and 19.0 months, respectively) (114). Functional validation also

demonstrates that KEAP1 deletion significantly elevates

IC50 of KRAS G12C inhibitors in H358 cells (118). Since KRAS/KEAP1 tumors are

resistant to multiple drugs, KRAS/KEAP1 tumors warrant

prioritization for clinical trials and experimental strategies

beyond current standard therapies.

Together, this emphasizes the need for co-mutation

profiling in treatment algorithms, as patients with KRAS/TP53

tumors may be more responsive to frontline ICI therapy; by

contrast, patients with KRAS/STK11 and KRAS/KEAP1 tumors represent

aggressive, immune-refractory subsets warranting alternative or

combination strategies.

Although targeted medicines provide a notable

response after treatment initiation, a large proportion of tumors

eventually resist targeted medications because of intertumoral

heterogeneity, where pre-existing resistance subclones survive

treatment and expand, driving tumor evolution toward resistance

(119). Secondary mutations in the

KRAS gene also cause resistance to specific inhibitors of the G12C

mutation. Mutations such as Y96D, A59T and G13D result in changes

to the KRAS protein structure that prevent inhibitors, including

sotorasib and adagrasib, from engaging with their target. Such

mutations frequently occur in the SII-P, a key area for drug

binding (120,121).

Concurrent mutations or alterations in driver

oncogenes, including TP53 and STK11/LKB1, are also involved in

resistance. It has been reported that tumors in which KRAS and

STK11 are mutant are less sensitive to immune checkpoint blockade

and KRAS-targeted agents, potentially due to the activation of

compensatory survival signaling pathways (122,123). Second, distant activation of

alternative signaling cascades exists that may mediate escape from

KRAS inhibition. MET amplification is the most extensively known

bypass mechanism, allowing downstream activation of the

PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in the presence of KRAS inhibition

(79,124). Other reported bypass routes

include RET fusions and wild-type RAS activation (121,123). These alterations enable tumor

cells to maintain proliferative signaling despite KRAS blockade.

Aside from developing secondary mutations, reactivation of

wild-type KRAS or other RAS family members can resurrect signaling

downstream of the pathway. This reactivation undermines the

efficacy of KRAS G12C inhibitors and leads to therapeutic failure

(121).

Tumor cells can also acquire resistance via

nongenetic means unrelated to new mutations. Cancer cells are kept

alive under drug pressure by cellular plasticity, stress-response

signaling and reprogramming of signal networks. For example,

activation of integrin β4 and paxillin pathways, among others, can

stimulate AKT signaling, contributing to a drug-tolerant persistent

cell phenotype (125,126). Finally, modifications in the TME

are significantly associated with therapy resistance. As such,

hypoxia and TME nutrient deprivation can induce adaptive stress

responses in cancer cells, leading to improved survival and

resistance to targeted therapies (127). Patients receiving KRAS inhibitors

also had worse prognoses when they had oxidative stress

response-related alterations, such as KEAP1 mutations (71). Table

III summarizes the various resistance mechanisms to

KRAS-targeted therapies in NSCLC, including genetic factors,

signaling pathways and TME-associated modifications associated with

treatment resistance.

Multiplex screening via next-generation sequencing

(NGS) is recommended for adequate patient selection in the European

Society for Medical Oncology clinical practice guidelines (4,128).

KRAS G12C inhibitors are a key treatment option for patients who

are not eligible for standard first-line therapies. For example,

co-mutations, including STK11 and KRAS G12C, are associated with

inferior responses to ICIs, indicating that KRAS G12C inhibitors

may be preferential as first-line treatment in those settings.

Another potential strategy is to use chemotherapy or ICIs in

combination with KRAS G12C inhibitors (129–131).

The development of resistance to conventional

therapies is a notable problem that has led to a paradigm shift

toward multitargeted therapies and improvements in drug delivery

systems for improved patient prognostic results. KRAS mutations are

considered actionable, particularly for G12C subtype for which

direct inhibitors are now available. Personalization of therapy is

essential because KRAS mutations are heterogeneous and exert

diverse effects on treatment response (132–134). Additional investigation is

warranted for KRAS G12D and G12V mutations, which represents 38% of

KRAS-mutant LUAD cases, as these variants currently lack effective

targeted therapies. Furthermore, emerging pan-KRAS inhibitors

should be further explored as potential treatment strategies

(135).

Emerging strategies for KRAS-mutant NSCLC are

increasingly shaped by advanced bioinformatic and genomic tools

that enable personalized therapy. Artificial intelligence (AI) is

increasingly shaping the drug discovery process, notably with its

rapid expansion induced by drug repurposing strategies. Machine

learning model coupled with molecular docking has demonstrated that

the FDA-approved drugs, including afatinib, neratinib and

zanubrutinib, are likely to be effective against KRAS G12C. This

method demonstrates how AI can identify novel therapeutic

opportunities and is particularly useful for hard-to-target alleles

such as KRAS G12D, where direct inhibitors remain limited (89).

Neoantigen prediction algorithms represent another

avenue of research. Mutant KRAS peptides have demonstrated potent

T-cell responses, which is relevant for STK11 co-mutated or high

TMB tumors. Such subsets are frequently resistant to ICIs

monotherapy, and the options of personalizing a vaccine or

establishing adoptive T-cell therapy constitute a rational approach

for these populations (136,137).

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has also been

applied to KRAS-induced tumors, and a tumor-associated epidermal

subpopulation that depended on the oncogene BMI-1 has been

identified, which contributes to tumor growth and treatment

resistance. Treatment approaches targeting this subpopulation with

small-molecule inhibitor PTC596 inhibited tumor growth in

preclinical models, demonstrating how scRNA-seq could detect

resistant subclones and guide targeted therapy (138).

Finally, CRISPR-based therapies are also broadening

treatment choices. High-fidelity Cas9 editing has shown that KRAS

G12C and G12D mutations can be corrected in organoid or xenograft

models with reduced tumor growth (139). In addition, genome-wide CRISPR

screens have identified synthetic lethal relationships that might

be exploited for rational combination strategies or resistance to

KRAS inhibitors by targeting TEA domain transcription factor, CDK4

and Wee1-like protein kinase dependencies (140). Together, these approaches

represent the innovative customized therapy for KRAS-mutation lung

cancer; however, these CRISPR-based and synthetic-lethal strategies

still face key limitations, such as off-target effects and

uncertain clinical translation, additional research is required to

overcome these limitations and improve patient outcomes.

KRAS has emerged as a viable target for therapeutic

inhibition in lung cancer, overcoming the previous challenges

associated with a limited understanding of KRAS biology and protein

biochemistry. Technological progress has deepened understanding of

RAS biology, including the discovery of novel druggable pockets and

the usefulness of molecular subtyping. Among the current

investigational treatments, small-molecule inhibitors targeting the

KRAS G12C mutation have demonstrated promising results. However,

molecular heterogeneity and resistance mechanisms remain concerns,

thus requiring additional translational research. Combination

strategies, such as immuno-targeted therapy, are increasingly

popular to maximize KRAS inhibition. The current challenges and

strategies in KRAS-mutated NSCLC research are overcoming resistance

to ICIs and KRAS inhibitors, discovering predictive biomarkers,

expanding targeted therapies to additional KRAS mutations and

optimizing diagnostic accuracy using NGS analysis of patient plasma

and tissue samples. Furthermore, worldwide accessibility to novel

agents remains essential. These efforts will help to improve the

quality of life and survival of patients with NSCLC.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

US prepared the original draft. HK reviewed the

manuscript. JS, YZ and ZD reviewed and edited the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

El Osta B, Behera M, Kim S, Berry LD, Sica

G, Pillai RN, Owonikoko TK, Kris MG, Johnson BE, Kwiatkowski DJ, et

al: Characteristics and outcomes of patients with metastatic

KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinomas: The lung cancer mutation

consortium experience. J Thorac Oncol. 14:876–889. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Moore AR, Rosenberg SC, McCormick F and

Malek S: RAS-targeted therapies: is the undruggable drugged? Nat

Rev Drug Discov. 19:533–552. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Simanshu DK, Nissley DV and McCormick F:

RAS proteins and their regulators in human disease. Cell.

170:17–33. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Prior IA, Hood FE and Hartley JL: The

frequency of ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 80:2669–2974.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dearden S, Stevens J, Wu YL and Blowers D:

Mutation incidence and coincidence in non small-cell lung cancer:

Meta-analyses by ethnicity and histology (mutMap). Ann Oncol.

24:2371–2376. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yang H, Liang SQ, Schmid RA and Peng RW:

New horizons in KRAS-mutant lung cancer: Dawn after darkness. Front

Oncol. 9:9532019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Naim MJ, Alam MJ, Ahmad S, Nawaz F,

Shrivastava N, Sahu M and Alam O: Therapeutic journey of

2,4-thiazolidinediones as a versatile scaffold: An insight into

structure activity relationship. Eur J Med Chem. 129:218–250. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bos JL: Ras oncogenes in human cancer: A

review. Cancer Res. 49:4682–4689. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Prior IA, Lewis PD and Mattos C: A

comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res.

72:2457–2467. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yin G, Huang J, Petela J, Jiang H, Zhang

Y, Gong S, Wu J, Liu B, Shi J and Gao Y: Targeting small GTPases:

Emerging grasps on previously untamable targets, pioneered by KRAS.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:2122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Michalak DJ, Unger B, Lorimer E, Grishaev

A, Williams CL, Heinrich F and Lösche M: Structural and biophysical

properties of farnesylated KRas interacting with the chaperone

SmgGDS-558. Biophys J. 121:3684–3697. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Herbst RS, Morgensztern D and Boshoff C:

The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature.

553:446–454. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jeon H, Wang S, Song J, Gill H and Cheng

H: Update 2025: Management of non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung.

203:532025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Huang L, Guo Z, Wang F and Fu L: KRAS

mutation: From undruggable to druggable in cancer. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 6:3862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang F, Wang B, Wu M, Zhang L and Ji M:

Current status of KRAS G12C inhibitors in NSCLC and the potential

for combination with anti-PD-(L)1 therapy: A systematic review.

Front Immunol. 16:15091732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Uniyal P, Kashyap VK, Behl T, Parashar D

and Rawat R: KRAS mutations in cancer: Understanding signaling

pathways to immune regulation and the potential of immunotherapy.

Cancers (Basel). 17:7852025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Parikh K, Banna G, Liu SV, Friedlaender A,

Desai A, Subbiah V and Addeo A: Drugging KRAS: Current perspectives

and state-of-art review. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hamarsheh S, Groß O, Brummer T and Zeiser

R: Immune modulatory effects of oncogenic KRAS in cancer. Nat

Commun. 11:54392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ghimessy A, Radeczky P, Laszlo V, Hegedus

B, Renyi-Vamos F, Fillinger J, Klepetko W, Lang C, Dome B and

Megyesfalvi Z: Current therapy of KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Cancer

Metastasis Rev. 39:1159–1177. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Eser M, Hekimoglu G, Yarar MH, Canbek S

and Ozcelik M: KRAS G12C mutation in NSCLC in a small genetic

center: Insights into sotorasib therapy response potential. Sci

Rep. 14:265812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bourne HR, Sanders DA and McCormick F: The

GTPase superfamily: A conserved switch for diverse cell functions.

Nature. 348:125–132. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bourne HR, Sanders DA and McCormick F: The

GTPase superfamily: Conserved structure and molecular mechanism.

Nature. 349:117–127. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Scheffzek K, Ahmadian MR, Kabsch W,

Wiesmüller L, Lautwein A, Schmitz F and Wittinghofer A: The

Ras-RasGAP complex: Structural basis for GTPase activation and its

loss in oncogenic Ras mutants. Science. 277:333–338. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Martin P, Leighl NB, Tsao MS and Shepherd

FA: KRAS mutations as prognostic and predictive markers in

non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 8:530–542. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Adderley H, Blackhall FH and Lindsay CR:

KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: Converging small molecules

and immune checkpoint inhibition. EBioMedicine. 41:711–716. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Matikas A, Mistriotis D, Georgoulias V and

Kotsakis A: Targeting KRAS mutated non-small cell lung cancer: A

history of failures and a future of hope for a diverse entity. Crit

Rev Oncol Hematol. 110:1–12. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Shepherd FA, Domerg C, Hainaut P, Jänne

PA, Pignon JP, Graziano S, Douillard JY, Brambilla E, Le Chevalier

T, Seymour L, et al: Pooled analysis of the prognostic and

predictive effects of KRAS mutation status and KRAS mutation

subtype in early-stage resected non-small-cell lung cancer in four

trials of adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 31:2173–2181. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Riely GJ, Kris MG, Rosenbaum D, Marks J,

Li A, Chitale DA, Nafa K, Riedel ER, Hsu M, Pao W, et al: Frequency

and distinctive spectrum of KRAS mutations in never smokers with

lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 14:5731–5734. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Redig AJ, Chambers ES, Lydon CA, Dahlberg

SE, Alden RS and Janne PA: Genomic complexity in KRAS mutant

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from never/light-smokers v

smokers. J Clin Oncol. 34 (15 Suppl):S90872016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ferrer I, Zugazagoitia J, Herbertz S, John

W, Paz-Ares L and Schmid-Bindert G: KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung

cancer: From biology to therapy. Lung Cancer. 124:53–64. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li S, Liu S, Deng J, Akbay EA, Hai J,

Ambrogio C, Zhang L, Zhou F, Jenkins RW, Adeegbe DO, et al:

Assessing therapeutic efficacy of MEK inhibition in a

KRASG12C-driven mouse model of lung cancer. Clin Cancer

Res. 24:4854–4864. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Garassino MC, Marabese M, Rusconi P, Rulli

E, Martelli O, Farina G, Scanni A and Broggini M: Different types

of K-Ras mutations could affect drug sensitivity and tumour

behaviour in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 22:235–237.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS,

Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, Cho J, Suh J, Capelletti M,

Sivachenko A, et al: Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma

with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 150:1107–1120. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lee B, Lee T, Lee SH, Choi YL and Han J:

Clinicopathologic characteristics of EGFR, KRAS, and ALK

alterations in 6,595 lung cancers. Oncotarget. 7:23874–23884. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li S, Li L, Zhu Y, Huang C, Qin Y, Liu H,

Ren-Heidenreich L, Shi B, Ren H, Chu X, et al: Coexistence of EGFR

with KRAS, or BRAF, or PIK3CA somatic mutations in lung cancer: A

comprehensive mutation profiling from 5125 Chinese cohorts. Br J

Cancer. 110:2812–2820. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL,

Kwon R, Curran WJ Jr, Wu YL and Paz-Ares L: Lung cancer: Current

therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet. 389:299–311. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Skoulidis F and Heymach JV: Co-occurring

genomic alterations in non-small-cell lung cancer biology and

therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 19:495–509. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Christensen JG, Olson P, Briere T, Wiel C

and Bergo MO: Targeting Krasg12c-mutant cancer with a

mutation-specific inhibitor. J Intern Med. 288:183–191. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Haidar M and Jacquemin P: Past and future

strategies to inhibit membrane localization of the KRAS oncogene.

Int J Mol Sci. 22:131932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Tomasini P, Walia P, Labbe C, Jao K and

Leighl NB: Targeting the KRAS pathway in non-small cell lung

cancer. Oncologist. 21:1450–1460. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gysin S, Salt M, Young A and McCormick F:

Therapeutic strategies for targeting ras proteins. Genes Cancer.

2:359–372. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Spoerner M, Herrmann C, Vetter IR,

Kalbitzer HR and Wittinghofer A: Dynamic properties of the Ras

switch I region and its importance for binding to effectors. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 98:4944–4949. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Buhrman G, O'Connor C, Zerbe B, Kearney

BM, Napoleon R, Kovrigina EA, Vajda S, Kozakov D, Kovrigin EL and

Mattos C: Analysis of binding site hot spots on the surface of Ras

GTPase. J Mol Biol. 413:773–789. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA and

Shokat KM: K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP

affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 503:548–551. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Shima F, Matsumoto S, Yoshikawa Y,

Kawamura T, Isa M and Kataoka T: Current status of the development

of Ras inhibitors. J Biochem. 158:91–99. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Berndt N, Hamilton AD and Sebti SM:

Targeting protein prenylation for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer.

11:775–791. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Roberts PJ and Der CJ: Targeting the

Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the

treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 26:3291–3310. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zimmermann G, Papke B, Ismail S, Vartak N,

Chandra A, Hoffmann M, Hahn SA, Triola G, Wittinghofer A, Bastiaens

PI and Waldmann H: Small molecule inhibition of the KRAS-PDEδ

interaction impairs oncogenic KRAS signalling. Nature. 497:638–642.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Riely GJ, Johnson ML, Medina C, Rizvi NA,

Miller VA, Kris MG, Pietanza MC, Azzoli CG, Krug LM, Pao W and

Ginsberg MS: A phase II trial of Salirasib in patients with lung

adenocarcinomas with KRAS mutations. J Thorac Oncol. 6:1435–1437.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Whyte DB, Kirschmeier P, Hockenberry TN,

Nunez-Oliva I, James L, Catino JJ, Bishop WR and Pai JK: K- and

N-Ras are geranylgeranylated in cells treated with farnesyl protein

transferase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 272:14459–14464. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Shima F, Yoshikawa Y, Ye M, Araki M,

Matsumoto S, Liao J, Hu L, Sugimoto T, Ijiri Y, Takeda A, et al: In

silico discovery of small-molecule Ras inhibitors that display

antitumor activity by blocking the Ras-effector interaction. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:8182–8187. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gerber DE, Camidge DR, Morgensztern D,

Cetnar J, Kelly RJ, Ramalingam SS, Spigel DR, Jeong W, Scaglioni

PP, Zhang S, et al: Phase 2 study of the focal adhesion kinase

inhibitor defactinib (VS-6063) in previously treated advanced KRAS

mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 139:60–67. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, Luo J and

Der CJ: Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nat Rev

Drug Discov. 13:828–851. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wang M and Casey PJ: Protein prenylation:

Unique fats make their mark on biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

17:110–122. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kazi A, Xiang S, Yang H, Chen L, Kennedy

P, Ayaz M, Fletcher S, Cummings C, Lawrence HR, Beato F, et al:

Dual farnesyl and geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor thwarts

mutant KRAS-driven patient-derived pancreatic tumors. Clin Cancer

Res. 25:5984–5996. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Tao MH, Chen S, Freudenheim JL, Cauley JA,

Johnson KC, Mai X, Sarto GE, Wakelee H, Boffetta P and

Wactawski-Wende J: Oral bisphosphonate use and lung cancer

incidence among postmenopausal women. Ann Oncol. 29:1476–1485.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Nagao S, Hattori N, Fujitaka K, Iwamoto H,

Ohshimo S, Kanehara M, Ishikawa N, Haruta Y, Murai H and Kohno N:

Regression of a primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma after zoledronic

acid monotherapy. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 60:7–9. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Kitai H, Ebi H, Tomida S, Floros KV,

Kotani H, Adachi Y, Oizumi S, Nishimura M, Faber AC and Yano S:

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition defines feedback activation of

receptor tyrosine kinase signaling induced by MEK inhibition in

KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 6:754–769. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Johnson C, Burkhart DL and Haigis KM:

Classification of KRAS-activating mutations and the implications

for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Discov. 12:913–923. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Hunter JC, Manandhar A, Carrasco MA,

Gurbani D, Gondi S and Westover KD: Biochemical and structural

analysis of common cancer-associated KRAS mutations. Mol Cancer

Res. 13:1325–1335. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Ostrem JML and Shokat KM: Direct

small-molecule inhibitors of KRAS: From structural insights to

mechanism-based design. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 15:771–785. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, Mohr C, Cooke K,

Bagal D, Gaida K, Holt T, Knutson CG, Koppada N, et al: The

clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity.

Nature. 575:217–223. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Pandey D, Chauhan SC, Kashyap VK and Roy

KK: Structural insights into small-molecule KRAS inhibitors for

targeting KRAS mutant cancers. Eur J Med Chem. 277:1167712024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Warnecke B and Nagasaka M: Adagrasib in

the treatment of KRAS p.G12C positive advanced NSCLC: Design,

development and place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther.

18:5673–5683. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Li Z, Song Z, Zhao Y, Wang P, Jiang L,

Gong Y, Zhou J, Jian H, Dong X, Zhuang W, et al: D-1553

(Garsorasib), a potent and selective inhibitor of

KRASG12C in patients with NSCLC: Phase 1 study results.

J Thorac Oncol. 18:940–951. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

D'Alessio-Sands L, Gaynier J,

Michel-Milian V, Agbowuro AA and Brackett CM: Current strategies

and future dimensions in the development of KRAS inhibitors for

targeted anticancer therapy. Drug Dev Res. 86:e700422025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Deming DA: Development of KRAS inhibitors

and their role for metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc

Netw. 23:e2470672025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zhao T and Liang SH: Novel tricyclic KRAS

inhibitors for the treatment of cancer. ACS Med Chem Lett.

16:178–179. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Hong DS, Fakih MG, Strickler JH, Desai J,

Durm GA, Shapiro GI, Falchook GS, Price TJ, Sacher A, Denlinger CS,

et al: KRASG12C inhibition with sotorasib in advanced

solid tumors. N Engl J Med. 383:1207–1217. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

No authors listed. FDA approves first KRAS

inhibitor: Sotorasib. Cancer Discov. 11:OF42021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ,

Falchook GS, Wolf J, Italiano A, Schuler M, Borghaei H, Barlesi F,

et al: Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl

J Med. 384:2371–2381. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Jänne PA, Riely GJ, Gadgeel SM, Heist RS,

Ou SI, Pacheco JM, Johnson ML, Sabari JK, Leventakos K, Yau E, et

al: Adagrasib in non-small-cell lung cancer harboring a

KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 387:120–131. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

de Langen AJ, Johnson ML, Mazieres J,

Dingemans AC, Mountzios G, Pless M, Wolf J, Schuler M, Lena H,

Skoulidis F, et al: Sotorasib versus docetaxel for previously

treated non-small-cell lung cancer with KRASG12C

mutation: A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet.

401:733–746. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Wislez M, Mascaux C, Cadranel J, Thomas

QD, Ricordel C, Swalduz A, Pichon E, Veillon R, Gounant V,

Rousseau-Bussac G, et al: Real-world effectiveness and tolerability

of sotorasib in patients with KRAS G12C-mutated metastatic

non-small cell lung cancer: The IFCT-2102 lung KG12Ci study. Eur J

Cancer. 219:1153012025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Ou SHI, Jänne PA, Leal TA, Rybkin II,

Sabari JK, Barve MA, Bazhenova L, Johnson ML, Velastegui KL,

Cilliers C, et al: First-in-human phase I/IB dose-finding study of

adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients with advanced KRASG12C

solid tumors (KRYSTAL-1). J Clin Oncol. 40:2530–2538. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Mok TSK, Yao W, Duruisseaux M, Doucet L,

Azkárate Martínez A, Gregorc V, Juan-Vidal O, Lu S, De Bondt C, de

Marinis F, et al: KRYSTAL-12: Phase 3 study of adagrasib versus

docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced/metastatic

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring a KRASG12C

mutation. J Clin Oncol. 42 (Suppl 17):LBA85092024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Li Z, Dang X, Huang D, Jin S, Li W, Shi J,

Wang X, Zhang Y, Song Z, Zhang J, et al: Abstract CT246:

Open-label, single-arm, multicenter, phase 2 trial of garsorasib in

KRAS G12C-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 84 (7

Suppl):CT2462024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Li Z, Dang X, Huang D, Jin S, Li W, Shi J,

Wang X, Zhang Y, Song Z, Zhang J, et al: Garsorasib in patients

with KRASG12C-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer in

China: An open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial.

Lancet Respir Med. 12:589–598. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Awad MM, Liu S, Rybkin II, Arbour KC,

Dilly J, Zhu VW, Johnson ML, Heist RS, Patil T, Riely GJ, et al:

Acquired resistance to KRASG12C inhibition in cancer. N

Engl J Med. 384:2382–2393. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Cox AD and Der CJ: ‘Undruggable KRAS’:

Druggable after all. Genes Dev. 39:132–162. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Maruyama K, Shimizu Y, Nomura Y, Oh-Hara

T, Takahashi Y, Nagayama S, Fujita N and Katayama R: Mechanisms of

KRAS inhibitor resistance in KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer

harboring Her2 amplification and aberrant KRAS localization. NPJ

Precis Oncol. 9:42025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Mugarza E, van Maldegem F, Boumelha J,

Moore C, Rana S, Llorian Sopena M, East P, Ambler R, Anastasiou P,

Romero-Clavijo P, et al: Therapeutic KRASG12C inhibition

drives effective interferon-mediated antitumor immunity in

immunogenic lung cancers. Sci Adv. 8:eabm87802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Garassino MC, Jänne PA, Barlesi F, Spira

AI, Mok TSK, Hochmair M, O'Byrne KJ, Felip E, Kim SW, Cappuzzo F,

et al: 1394TiP KRYSTAL-7: A phase III study of first-line adagrasib

plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab alone in patients with

advanced NSCLC with KRASG12C mutation mutation. Ann Oncol. 35

(Suppl 2):S872–S873. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Li BT, Falchook GS, Durm GA, Burns TF,

Skoulidis F, Ramalingam SS, Spira A, Bestvina CM, Goldberg SB,

Veluswamy R, et al: OA03.06 CodeBreaK 100/101: First report of

safety/efficacy of sotorasib in combination with pembrolizumab or

atezolizumab in advanced KRAS p.G12C NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 17

(Suppl):S10–S11. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Ernst SM, Hofman MM, van der Horst TE,

Paats MS, Heijboer FWJ, Aerts JGJV, Dumoulin DW, Cornelissen R, von

der Thüsen JH, de Bruijn P, et al: Hepatotoxicity in patients with

non-small cell lung cancer treated with sotorasib after prior

immunotherapy: A comprehensive clinical and pharmacokinetic

analysis. EBioMedicine. 102:1050742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Chour A, Basse C, Lebossé F, Bonte PE,

Girard N and Duruisseaux M: Management of sotorasib-related adverse

events and hepatotoxicities following anti-PD-(L)1 therapy:

Experience with sotorasib in two French anti-cancer centers and

practical guidance proposal. Lung Cancer. 191:1077892024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Zhang J, Johnson M, Barve M, Bazhenova L,

McCarthy M, Schwartz R, Horvath-Walsh E, Velastegui K, Qian C and

Spira A: Practical guidance for the management of adverse events in

patients with KRASG12C-mutated non-small cell lung cancer receiving

adagrasib. Oncologist. 28:287–296. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Mina SA, Shanshal M, Leventakos K and

Parikh K: Emerging targeted therapies in non-small-cell lung cancer

(NSCLC). Cancers (Basel). 17:3532025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Fancelli S, Petroni G, Pillozzi S and

Antonuzzo L: Unconventional strategy could be the future: From

target to KRAS broad range treatment. Heliyon. 10:e297392024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Masfarre Pinto L, Parreira ASDFM, Castro

Unanua N, Rocha P, Morilla Ruiz I, Teijeira Sanchez L, Clave S,

Navarro Gorro N, Bach Mora R, Sánchez I, et al: 1408P Differences

on immune biomarkers between KRAS G12C and KRAS non-G12C mutated

non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 34 (Suppl2):S805–S806. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Zhou C, Li C, Luo L, Li X, Jia K, He N,

Mao S, Wang W, Shao C, Liu X, et al: Anti-tumor efficacy of

HRS-4642 and its potential combination with proteasome inhibition

in KRAS G12D-mutant cancer. Cancer Cell. 42:1286–1300.e8. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Li Y, Zhao J and Li Y: New exploration of

KRASG12D inhibitors and the mechanisms of resistance.

Exp Hematol Oncol. 14:392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Arbour KC, Rizvi H, Plodkowski AJ,

Hellmann MD, Knezevic A, Heller G, Yu HA, Ladanyi M, Kris MG,

Arcila ME, et al: Treatment outcomes and clinical characteristics

of patients with KRAS-G12C-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 27:2209–2215. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Bironzo P, Cani M, Jacobs F, Napoli VM,

Listì A, Passiglia F, Righi L, Di Maio M, Novello S and Scagliotti

GV: Real-world retrospective study of KRAS mutations in advanced

non-small cell lung cancer in the era of immunotherapy. Cancer.

129:1662–1671. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Rodenhuis S, van de Wetering ML, Mooi WJ,

Evers SG, van Zandwijk N and Bos JL: Mutational activation of the

K-ras oncogene. A possible pathogenetic factor in adenocarcinoma of

the lung. N Engl J Med. 317:929–935. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, Patel SP,

Frampton GM, Miller V, Stephens PJ, Daniels GA and Kurzrock R:

Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to

immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 16:2598–2608.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Mazieres J, Drilon A, Lusque A, Mhanna L,

Cortot AB, Mezquita L, Thai AA, Mascaux C, Couraud S, Veillon R, et

al: Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung

cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: Results from the

IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol. 30:1321–1328. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Rothschild SI: KRAS and immune checkpoint

inhibitors-serendipity raising expectations. J Thorac Oncol.

14:951–954. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Torralvo J, Friedlaender A, Achard V and

Addeo A: The activity of immune checkpoint inhibition in KRAS

mutated non-small cell lung cancer: A single centre experience.

Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 16:577–582. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Mok TSK, Lopes G, Cho BC, Kowalski DM,

Kasahara K, Wu YL, de Castro G Jr, Turna HZ, Cristescu R,

Aurora-Garg D, et al: Associations of tissue tumor mutational

burden and mutational status with clinical outcomes in KEYNOTE-042:

Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for advanced PD-L1-positive

NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 34:377–388. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|