Introduction

In 2020, the incidence of gastric cancer reached

~1.09 million cases, ranking 5th among all malignant tumors and

accounting for 5.6% of all malignant diseases (1,2). The

number of mortalities caused by gastric cancer totaled ~770,000,

ranking fourth and accounting for 7.7% of overall malignant

tumor-related fatalities (1,2). The

high prevalence and poor prognosis of gastric cancer have markedly

impacted the well-being of the population, especially in China

(3). In 2022, China reported

~397,000 new cases of gastric cancer, accounting for 37% of the

global total, with both incidence and mortality rates ranking third

among malignant tumors in China (4,5). East

Asia bears the brunt of the global burden, with ~60% of gastric

cancer cases occurring in this region (6–8). Along

with the health burden comes a pronounced economic loss to

residents and the government due to the diagnosis and treatment of

gastric cancer (9,10).

Early-stage gastric cancer often presents with

inconspicuous symptoms, which leads to late detection, suboptimal

treatment outcomes, high recurrence rates and low survival rates

(6,10–12).

The 5-year survival rate for advanced gastric cancer remains as low

as 5% globally (13–15). Currently, the predominant treatment

strategy for gastric cancer is comprehensive, with a primary

emphasis on surgical intervention (16–18).

Surgical procedures dominate the treatment landscape for

early-stage gastric cancer, while chemotherapy improves survival

and quality of life for locally advanced or metastatic cases (stage

Ib to IIIb) (8,17,19,20).

Despite the mature theory and practice of abdominal anatomy,

coupled with inherent shortcomings of chemotherapy, advances in

surgical and chemotherapeutic approaches to the treatment of

gastric cancer have been limited (8). Overall, the efficacy of gastric cancer

treatment remains unsatisfactory, with only modest improvements in

prognosis (21).

New therapeutic approaches, such as targeted drugs

and immunotherapy, offer hope for patients with gastric cancer

(22,23). Targeting central mechanisms of tumor

development, developing drugs that prevent uncontrolled cell

proliferation or directly inducing apoptosis represents a promising

path to a successful transformation and potentially a cure of

advanced gastric cancer (24).

GPR176, a G protein-coupled receptor located on

15q14-q15.1, belongs to the G protein-coupled receptor family and

functions as a cell surface receptor that responds to hormones,

growth factors and neurotransmitters (25). GPR176 is primarily expressed in the

brain, followed by the gallbladder and testis (25). While earlier studies focused

primarily on the role and mechanisms of GPR176 in circadian rhythms

(25,26,27),

later research recognizes its potential in tumors (28–32).

For example, Tang et al (28) revealed that GPR176 recruits GNAS,

activates the cAMP/PKA/BNIP3L signaling pathway and inhibits

mitochondrial autophagy, which promotes stem cell formation and

proliferation of colorectal adenocarcinoma. Yun et al

(29) demonstrated an association

between the expression of GPR176 and the prognosis of breast

adenocarcinoma. Interfering with GPR176 suppresses the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, glycolysis, epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and proliferation of breast adenocarcinoma cells. The

prognostic value of GPR176 in esophageal adenocarcinoma has also

been established, indicating an association with prognosis and

resistance of esophageal adenocarcinoma (30). Analyses of publicly available data

have suggested an association between GPR176 and gastric cancer

prognosis, warranting further exploration of underlying mechanisms

(31,32).

PIP5K1A, which encodes the protein

phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type 1 α, carries out a

role in several processes, including activation of GTPase activity

(33,34). It serves as an upstream regulator of

the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and genetic or pharmacological

inhibition of PIP5K1A markedly inhibits AKT phosphorylation

(35,36).

Building upon previous research, the present study

first evaluated the expression and prognostic significance of

GPR176 in gastric cancer and further elucidated the mechanism by

which GPR176 promotes cancer cell invasion and its functional

interaction with PIP5K1A, using both in vitro and in

vivo models.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data from 448 gastric

cancer (STAD) samples, including 410 tumor and 38 normal samples,

were collected, along with clinical data from 383 patients with

STAD, sourced from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database

(https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/)

(37). The Limma package in R 4.5.1

(https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html)

facilitated the standardization of RNA-seq information (38). The transcriptomic details for all

samples were preserved to investigate the nuanced differences

between adenocarcinomatous and adjacent tissues. However, 17

samples with incomplete clinical information were excluded from

subsequent survival analysis.

The RNA-seq data and associated clinical/prognostic

information for 300 patients diagnosed with gastric cancer were

methodically extracted from the GSE66254 dataset in the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE66254)

(39). The original chip data from

GSE66254 underwent a rigorous annotation and standardization

process in R, utilizing the Limma package.

Patient samples

From the biobank of the Department of

Gastrointestinal and Glandular Surgery at The First Affiliated

Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Nanning, China), tissue

specimens (including gastric cancer tumor and adjacent non-tumorous

tissues) were collected from 48 patients with gastric cancer who

underwent surgery. Postoperative pathological reports indicated

lymph node metastasis in 24 of these patients. These tissue samples

were subsequently utilized to analyze the correlation between lymph

node metastasis and the activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and EMT

signaling pathways, as well as the expression of GPR176.

Cell culture

The cell lines HGC-27 and NCI-N87 were procured from

the American Type Culture Collection (The Global Bioresource

Center; http://www.atcc.org/) cell repository.

Culturing these cells involved a comprehensive medium consisting of

DMEM (cat. no. 10566016; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

supplemented with 10% FBS (cat. no. 10099141C; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), 1% streptomycin and 1% penicillin (cat. no.

P1400; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The

controlled environment for these cell cultures was maintained in

incubators with 5% CO2 and 37°C.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA extraction from each sample (gastric cancer

tumor and adjacent non-tumorous tissues) was carried out using the

TRI Reagent™, by following the manufacturer's protocol

(cat. no. AM9738; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Subsequently, reverse transcription (RT) into cDNA was carried out

according to the manufacturer's instructions for the PrimeScript RT

Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (cat. no. RR047B; Takara Bio, Inc.).

The primers were designed using Primer3 (https://primer3.ut.ee/) and are listed in Table SI. qPCR was performed using the

FastStart Universal SYBR® Green Master Mix (cat. no.

06402712001; Roche Diagnostics GmbH) on an Applied Biosystems 7500

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the following thermocycling

conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Gene expression was

analyzed using the 2−∆∆Cq method (40).

Construction of lentivirus and stable

cell lines

Design and packaging of overexpression (OE)/RNA

interfering (RNAi) lentiviruses into cells was carried out by

Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. Lentiviruses for GPR176 overexpression,

GPR176 knockdown (sh-GPR176), PIP5K1A overexpression and PIP5K1A

knockdown (sh-PIP5K1A) were constructed using the wild-type

sequences of GPR176 and PIP5K1A, respectively. Lentiviruses

containing empty vectors were used as the control group for

infection. The infection concentration of all lentiviruses in the

present study was set to 5 multiplicity of infection (MOI), with an

infection duration of 12 h in 37°C cell incubator. Puromycin was

added at a concentration of 10 ng/ml to select cells with

off-target effects and the selection period was 5 days in in 37°C

cell incubator. The GPR176 overexpression lentivirus contained the

wild-type sequence of the GPR176 gene, while the PIP5K1A

overexpression lentivirus contained the wild-type sequence of the

PIP5K1A gene. The functional sequences of sh-GPR176 and sh-PIP5K1A

are provided in Table SII. The

efficacy of these lentiviruses was verified through a using RT-qPCR

assay and western blotting (WB).

WB

Extraction of proteins from cells (HGC-27 and

NCI-N87) and tissues (gastric cancer and adjacent normal gastric)

entailed a combination of RIPA reagent (cat. no. R0010; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and 1% PMSF (cat. no.

P0100; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.).

Quantification of protein concentration was carried out using the

BCA protein assay kit (cat. no. P0009; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). The proteins (2 µg) underwent separation using 10%

SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and were then transferred to PVDF

membranes. Following blocking with 5% skim milk at room temperature

for 30 min, the PVDF membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with

the diluent for the primary antibody. After two washes with

PBS-Tween (1%), the membranes were incubated with secondary

antibody diluent at 23°C for 1 h. The visualization of protein

bands was carried out using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Imaging System

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The information and usage

concentrations of the corresponding primary antibodies are listed

in Table SIII. HRP-conjugated Goat

Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (1:100; cat. no. SA00001-1, Proteintech Group

Inc.) and HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:100; cat.

no. SA00001-2, Proteintech Group Inc.) were used as the secondary

antibody.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

IF staining was carried out following standard

protocols (https://www.ptgcn.com/support/protocols/#if). Briefly,

1×105 HGC-27 and NCI-N87 cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, permeabilized with

0.2% Triton X-100 (cat. no. 9002-93-1; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) and blocked with 5% normal goat serum

(cat. no. SL038, Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were then incubated with

primary antibodies (Vimentin, 1:200; E-cadherin, 1:200) at 4°C

overnight, followed by Multi-rAb® CoraLite®

Plus 488-Goat Anti-Rabbit Recombinant Secondary Antibody (H+L)

(1:500; cat. no. RGAR002; Proteintech Group Inc.) and

Multi-rAb® CoraLite® Plus 594-Goat

Anti-Rabbit Recombinant Secondary Antibody (H+L) (1:500; cat. no.

RGAR004; Proteintech Group Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h and

DAPI (cat. no. 28718-90-3, Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) nuclear counterstaining at room temperature

for 15 min. Fluorescence images were captured with an Olympus

inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX73; Olympus

Corporation) equipped with appropriate filter sets and a digital

camera and analyzed using Olympus CellSens software 2.3.

Cell invasion assays

The cell suspension was obtained by digesting the

cells with 1 ml trypsin (cat. no. T1321; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) for 2 min, adding 5 ml of complete

medium, and then repeatedly pipetting the mixture. Before adding

the cell suspension in 6.5 mm Transwell® with 8.0 µm

Pore Polycarbonate Membrane Inserts (cat. no. 3422; Corning, Inc.),

the Matrigel (cat. no. 356234; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) was prepared according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Cells were plated in the upper chambers, and the

culture medium was added to the lower chambers. Specifically, 200

µl of a serum-free cell suspension containing 100,000 cells was

added to the upper Transwell inserts, while 600 µl of DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers of a

24-well plate. The plate was then incubated for 48 h at 37°C and 5%

CO2. After incubation, the insert was fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min and stained with a

1% crystal violet solution at room temperature for 20 min.

Subsequent actions included the erasure of cells on the upper

layer, which were then removed, washed with PBS, and the invaded

cells were observed under an Olympus IX53.

Cell wound healing assays

Cells (HGC-27 cells and NCI-N87) were grouped

according to the regulation of GPR176 and PIP5K1A, with the details

stated in Construction of lentivirus and stable cell lines.

To observe cell proliferation (HGC-27 and NCI-N87), a precise wound

was induced by scratching the plate with a 200 µl suction tip when

the cells covered 90–100% of the culture plate area. After washing

twice with PBS, serum-free medium was added to the plate, and cells

were cultured in incubators with 5% CO2 and 37°C.

Subsequently, the width of the wound was observed and imaged

consecutively under the Olympus IX53 at 0 and 48 h.

Nude-mouse transplanted tumor model

construction

Male nude mice (n=40; 6–8 weeks old; 18–22 g) were

housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with a controlled

temperature of 22±2°C, humidity of 50±10% and a 12-h light/dark

cycle. All animals had ad libitum access to a standard laboratory

diet and autoclaved water. The nude mice were randomly assigned

into four groups (10 per group) and received subcutaneous

injections of HGC-27 cells: sh-NC, sh-GPR-176, Lenti-null and

Lenti-GPR-176, respectively. HGC-27 cells in a stable growth state

were resuspended in pre-cooled PBS at a concentration of

1×107 cells/200 µl. This suspension was aseptically

injected subcutaneously into the right flank of each mouse.

After transplantation, the general health status and

body weight of the mice were monitored daily. Tumor volume was

measured every two days using a digital caliper and calculated

using the formula V=(length × width2 × π)/6. To minimize

observer bias, all measurements were conducted in a blinded

fashion. Humane endpoints were strictly defined as follows: Tumor

burden >1.5 cm in diameter, significant weight loss (>20% of

initial body weight) or signs of severe distress. None of the

animals reached these endpoints prior to the scheduled experimental

conclusion. At the end of the experiment (day 28 post-inoculation),

all mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation with a

chamber displacement rate of 30–50% per min, followed by cervical

dislocation to ensure mortality.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was carried out to at least three

independent replicates. Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS

Statistics software (version 26.0; IBM Corp.). Results are

expressed as the mean ± standard error. Differences between two

groups were assessed using an unpaired Student's t-test, while

multiple comparisons were carried out by one-way or two-way ANOVA.

Linear regression and correlation analysis were employed to assess

the correlation between GPR176 and PIP5K1A expression. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

GPR176 is associated with the

prognosis and clinicopathologic factors of gastric

adenocarcinomas

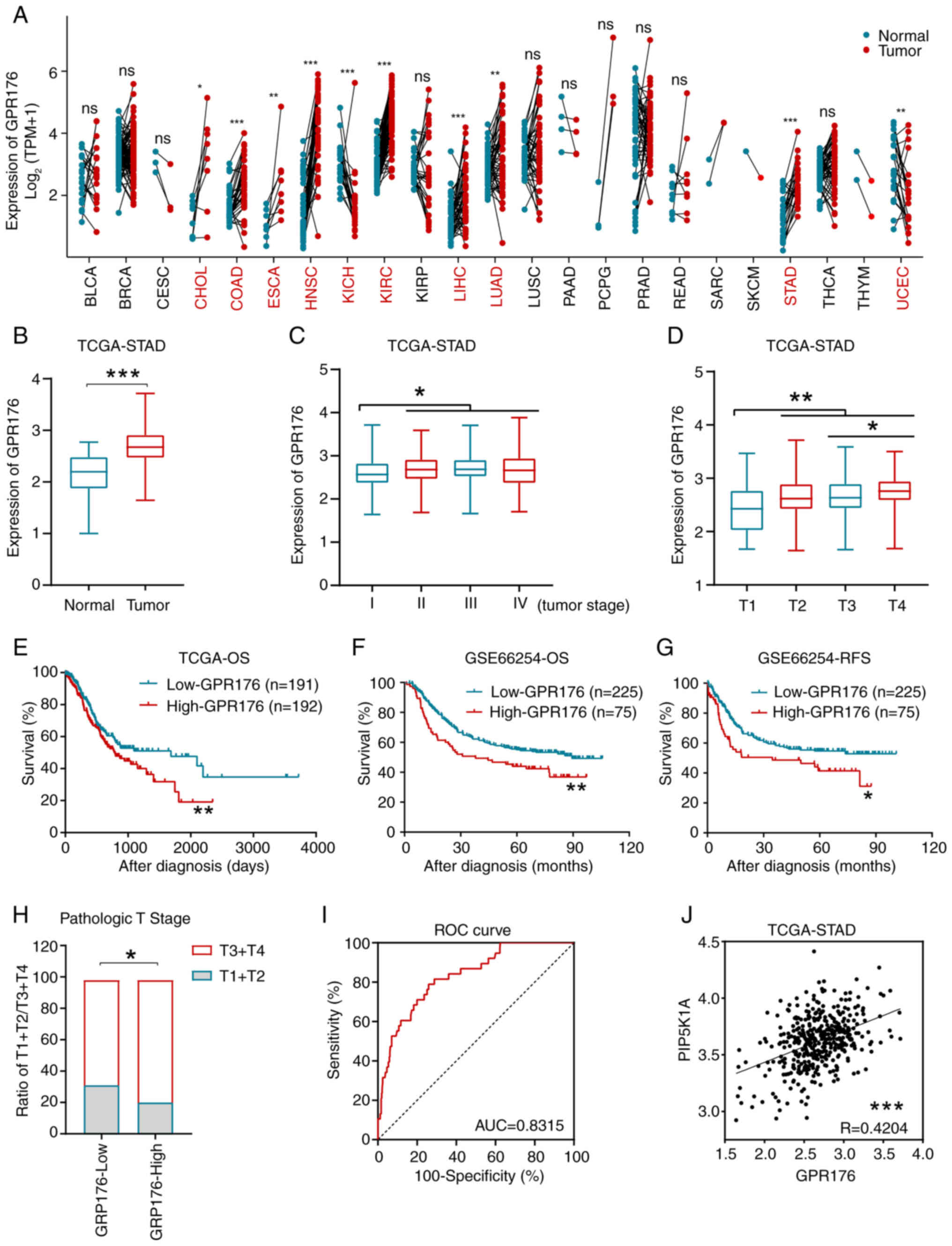

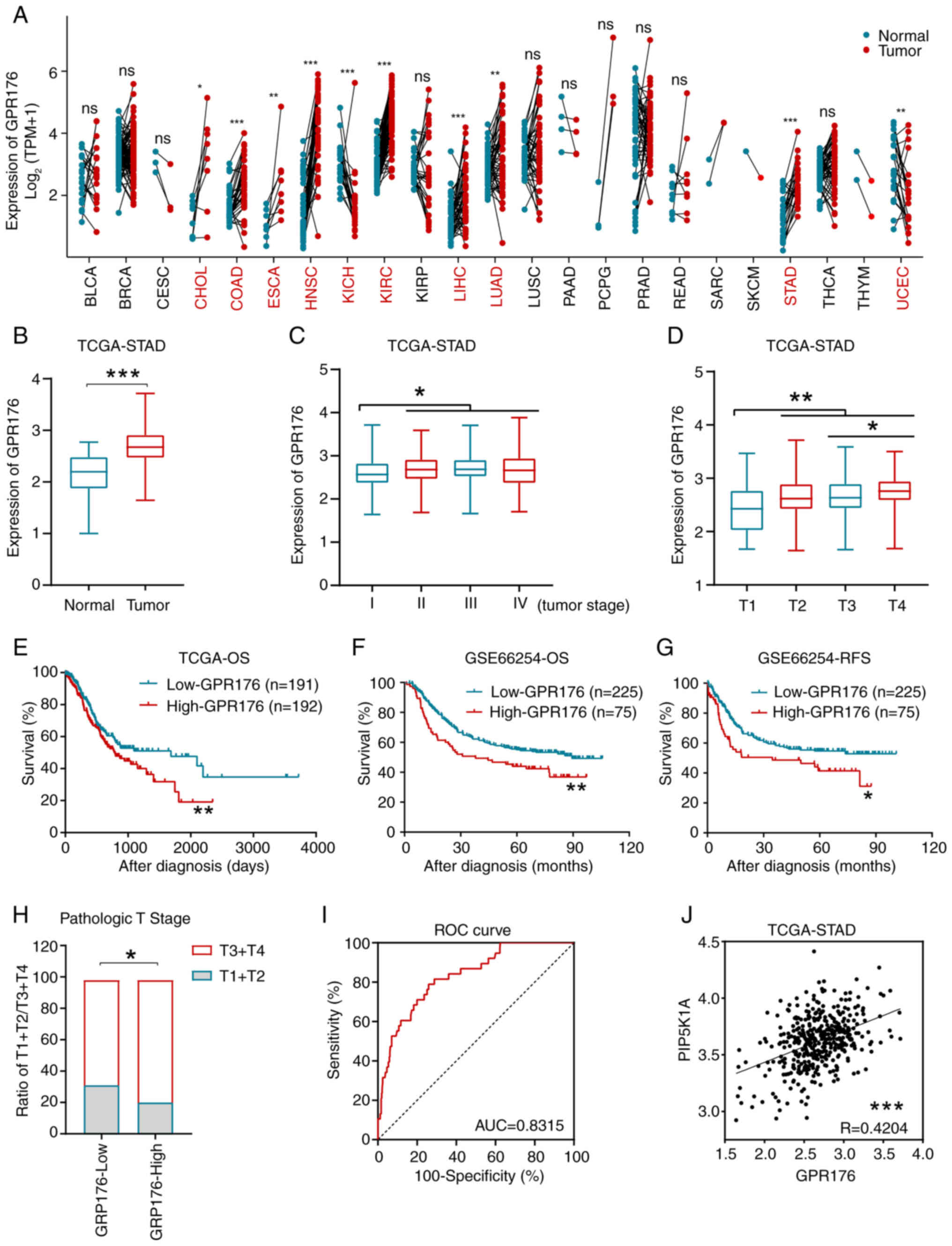

Expression matrices and corresponding clinical data

were respectively obtained from TCGA-STAD dataset and GSE66254

dataset (37,39). The expression of GPR176, its

prognostic significance and its association with clinicopathologic

factors were evaluated. Analysis of the pan-cancer data from TCGA

revealed significant differences in GPR176 expression between

cancer and adjacent tissues in cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), colon

adenocarcinoma (COAD), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), kidney chromophobe (KICH), kidney

renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), liver hepatocellular carcinoma

(LIHC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD)

and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC) (Fig. 1A). In the TCGA-STAD dataset, the

expression of GPR176 was significantly higher in gastric cancer

tissues when compared with adjacent tissues (Fig. 1B). Additionally, GPR176 expression

levels were lower in patients with TNM stage I gastric

adenocarcinoma when compared with patients with stage II/III/IV

gastric adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1C),

and GPR176 expression levels were significantly lower in patients

with stage T1 when compared with patients with pathologic stage

T2/T3/T4 (Fig. 1D).

| Figure 1.GPR176 expression levels were

associated with clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis

in STAD patients. (A) GPR176 expression levels in common malignant

tumors and adjacent tissues. (B) Comparison of GPR176 expression

levels in STAD tumor tissues and adjacent normal stomach tissues.

(C) Expression levels of GPR176 mRNA in STAD tumors after TNM

staging (I, II, III and IV). (D) Expression levels of GPR176 mRNA

in STAD tumors at pathologic T1, T2, T3 and T4 stages. (E) Tn the

TCGA-STAD dataset, OS of patients with STAD with GPR176 high and

low expression groups using the median value as a cut-off. (F) In

the GSE66254 dataset, OS of patients with STAD with GPR176 high and

low expression groups using the 75th percentile value as a cut-off.

(G) In the GSE66254 dataset, RFS of patients with STAD with GPR176

high and low expression groups using the 75th percentile as a

cut-off. (H) Association of GPR176 expression with pathologic T

staging in the TCGA-STAD dataset. (I) The ROC curve based on GPR176

plotted for distinguishing between gastric cancer and adjacent

tissues. (J) Significant positive correlation between GPR176 and

PIP5K1A expression in the gastric cancer samples in the TCGA-STAD

dataset. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TCGA, The Cancer

Genome Atlas; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; OS, overall survival;

RFS, Recurrence-free survival. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. Unpaired Student's t-test was used in Fig. 1A-D, Survival analysis with

Kaplan-Meier method was used in Fig.

1E-G; Chi-squared test was used in Fig. 1F; Receiver Operating Characteristic

(ROC) was used in Fig. 1G; Linear

regression was used in Fig. 1H. |

Statistical analysis confirmed the association of

GPR176 with tissue type and tumor stage, suggesting its importance

in the occurrence and progression of gastric adenocarcinoma.

Subsequently, in the TCGA-STAD and GSE66254 datasets, significant

association was observed between GPR176 expression levels and

overall survival/recurrence-free survival in gastric

adenocarcinoma, with high GPR176 expression levels associated with

worse prognosis (Fig. 1E-G). Using

the median expression of GPR176 as a cut-off point, patients were

categorized into GPR176-High and GPR176-Low groups. An increased

proportion of patients at T3/T4 in the GPR176-High group was

observed (Fig. 1H). The area under

the receiver operating curve reached 0.8315, indicating GPR176 as a

good biomarker to distinguish gastric adenocarcinoma from normal

gastric tissue (Fig. 1I).

Correlation analysis of GPR176 with PIP5K1A expression levels in

gastric adenocarcinoma tissues using the TCGA-STAD dataset verified

a linear positive association (Fig.

1J).

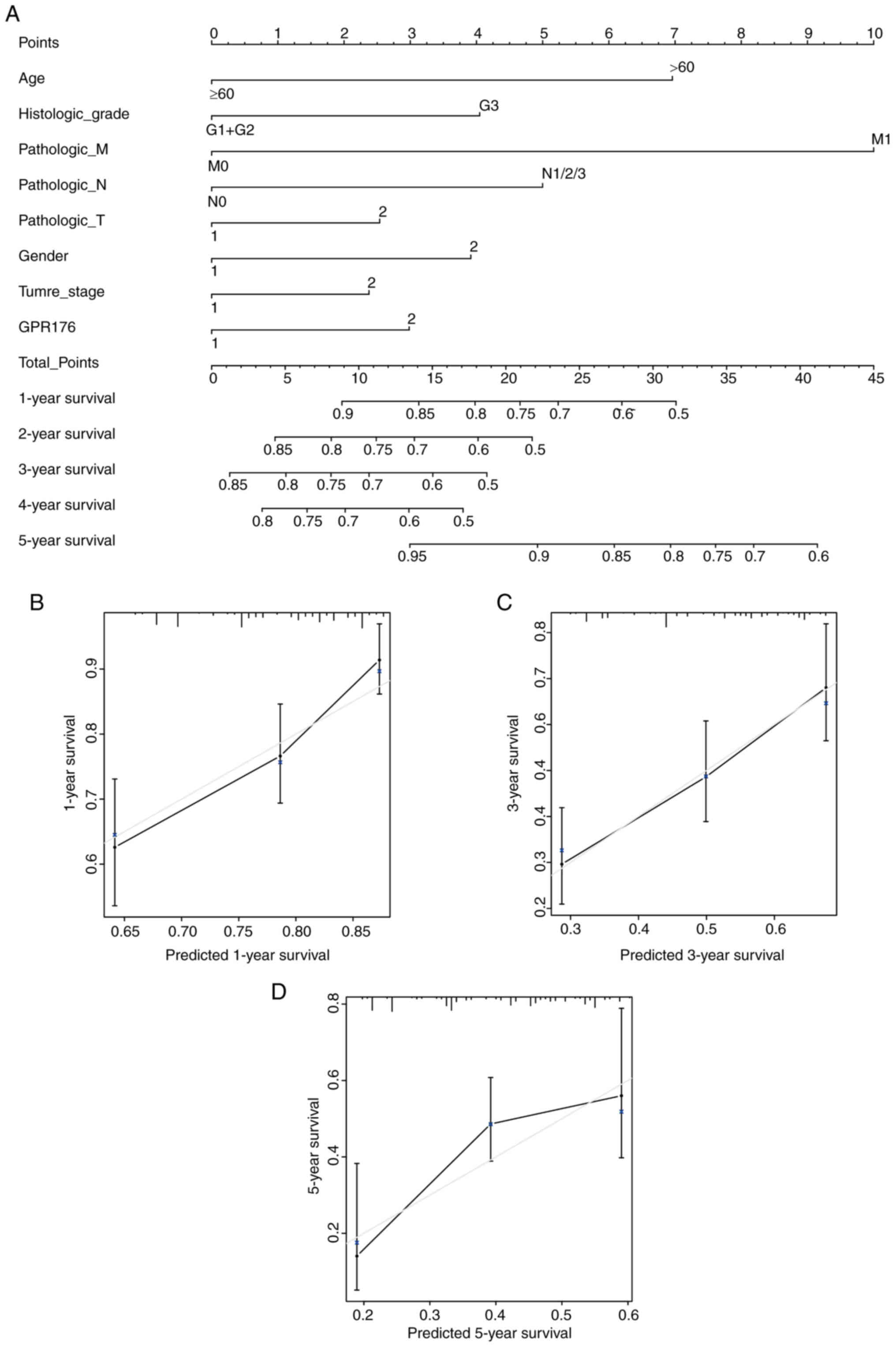

Nomogram construction

Nomogram were created based on GPR176 expression and

clinicopathologic parameters. Univariate Cox regression analysis

and multivariate Cox regression analysis were carried out using

clinical case characteristics such as age, sex, TNM stage, T stage,

N stage, M stage, histologic grade and GPR176 expression (Table SIV). The results of univariate Cox

regression analysis results indicated that age, sex, TNM stage, T

stage, N stage, M stage and histological grade were associated with

the overall survival of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. In

Multivariate Cox regression analysis, only age, histologic grade

and GPR176 expression were associated with overall survival of

patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. The nomogram graph based on

age, sex, TNM stage, T stage, N stage, M stage, histological grade

and GPR176 expression were constructed to assess the risk of

mortality for specific patients (Fig.

2A). The predictive power of the histogram was evaluated by

comparing the grade between the training group and the validation

group. The nomogram showed a high degree of overlap between the

self-validation cohort and the training group in predicting the 1-,

3- or 5-year prognosis (Fig.

2B-D).

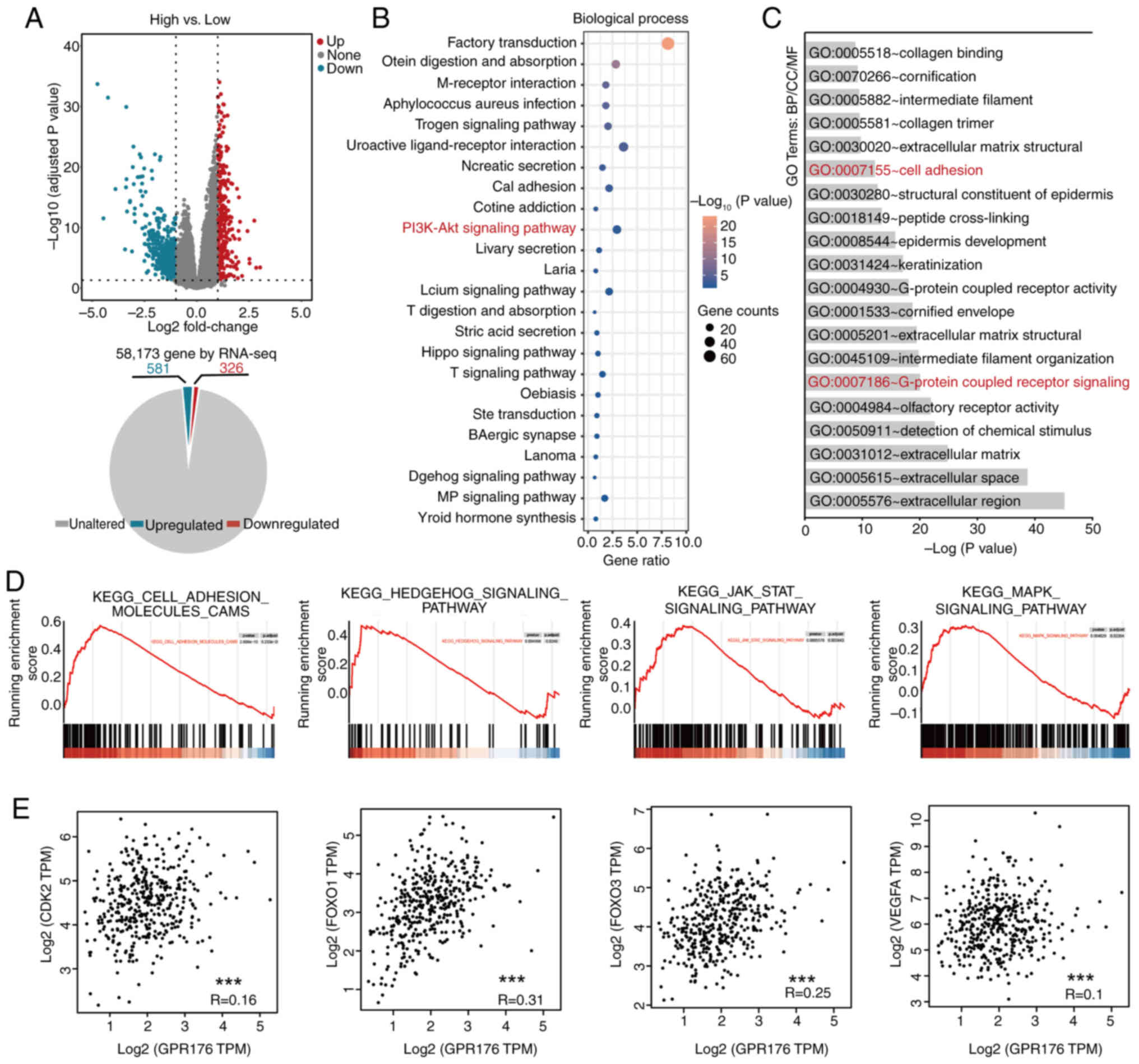

Exploration of the mechanisms of

GPR176 action using bioinformatics tools

Based on the expression levels of GPR176, patients

in the TCGA-STAD dataset were categorized into high and low

expression groups. Differential expression analysis was carried out

using the Limma package for RNA-seq and a volcano plot was

generated (Fig. 3A). The

corresponding pie charts showed that 326 genes were upregulated,

and 581 genes were downregulated. Functional enrichment analysis of

differentially expressed genes associated with GPR176 revealed

enrichment in signaling pathways such as ‘PI3K-Akt signaling

pathway’; Fig. 3B), and cellular

functions such as ‘Cell adhesion’ and ‘G-protein-coupled receptor

signaling’ (Fig. 3C). Gene Set

Enrichment Analysis indicated associations between GPR176 and

tumor-related signaling pathways such as ‘cell adhesion molecules

CAMs’, ‘Hedgehog signaling pathway’, ‘Jak-stat signaling pathway’

and ‘MAPK signaling pathway’ (Fig.

3D). CDK2, FOXO1, FOXO3 and VEGFA are downstream target genes

of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, reflecting the

activation/inhibition status of the pathway (41). Linear regression analysis using

RNA-seq data from gastric adenocarcinoma tissues in TCGA-STAD

revealed an association between GPR176 and CDK2, FOXO1, FOXO3 and

VEGFA (Fig. 3E).

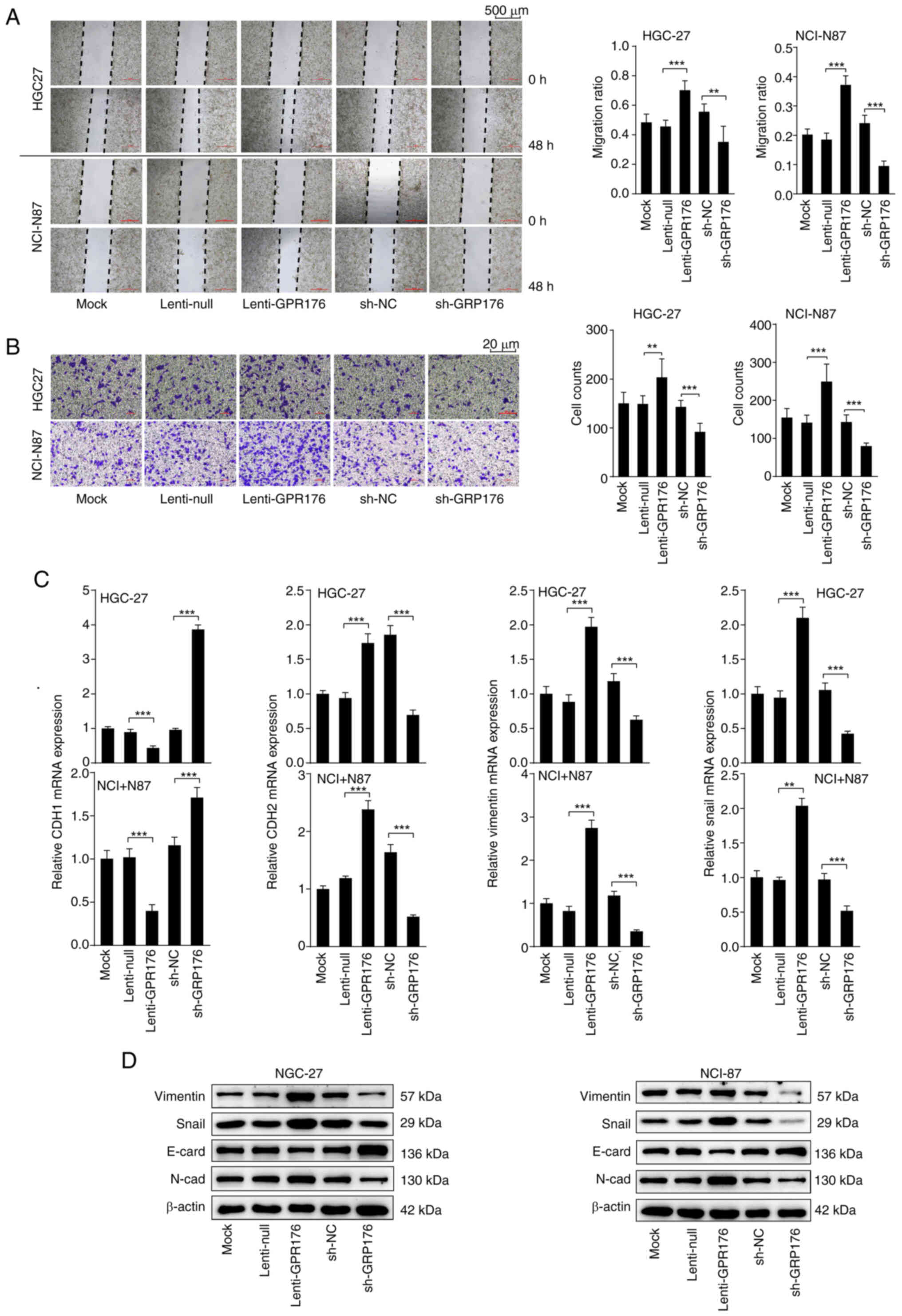

GPR176 enhances the migration and

invasion capabilities of gastric cancer cells and induces EMT

To confirm the effect of GPR176 on the biological

behavior of gastric cancer cells and explore the corresponding

mechanisms, lentiviral vectors were used to overexpress and

knockdown GPR176 expression levels. RT-qPCR and WB confirmed the

satisfactory efficiency of OE lentivirus and RNAi lentivirus in

HGC-27 and NCI-N87 cells (Fig.

S1A). Subsequently, scratch-wound healing and Transwell assays

were carried out to evaluate the effects of modulating GPR176

expression on cell migration and invasion. After upregulation of

GPR176, the migration and invasion ability of cells increased

significantly, while downregulation of GPR176 resulted in a

significant decrease in this ability (Fig. 4A and B). Subsequent RT-qPCR analysis

revealed a significant increase in the mRNA levels of

EMT-activating genes, such as CDH2, VIM and SNAI1, following

upregulation of GPR176 (Fig. 4C).

By contrast, the expression of the gene CDH1 which encodes

E-cadherin, associated with the inhibition of the EMT pathway

(42), significantly decreased

(Fig. 4C). Conversely,

downregulation of GPR176 led to a significant decrease in the mRNA

levels of CDH2, VIM and SNAI1, accompanied by a significant

increase in the mRNA levels of CDH1, associated with the inhibition

of the EMT pathway (Fig. 4C). WB

results corroborated the RT-qPCR results and revealed an increase

in the protein concentration of N-cadherin, vimentin and Snai1, and

a decrease in the protein concentration of E-cadherin after

upregulation of GPR176 (Fig. 4D),

with the corresponding bar chart shown in Fig. S2A and B. IF showed that GPR176

upregulation increased vimentin and reduced E-cadherin, whereas

GPR176 knockdown had the opposite effect (Fig. S1E). The results from RT-qPCR, WB,

and IF experiments showed that GPR176 expression was associated

with the activation of the EMT signaling pathway and increased

migration and invasion of gastric adenocarcinoma cells.

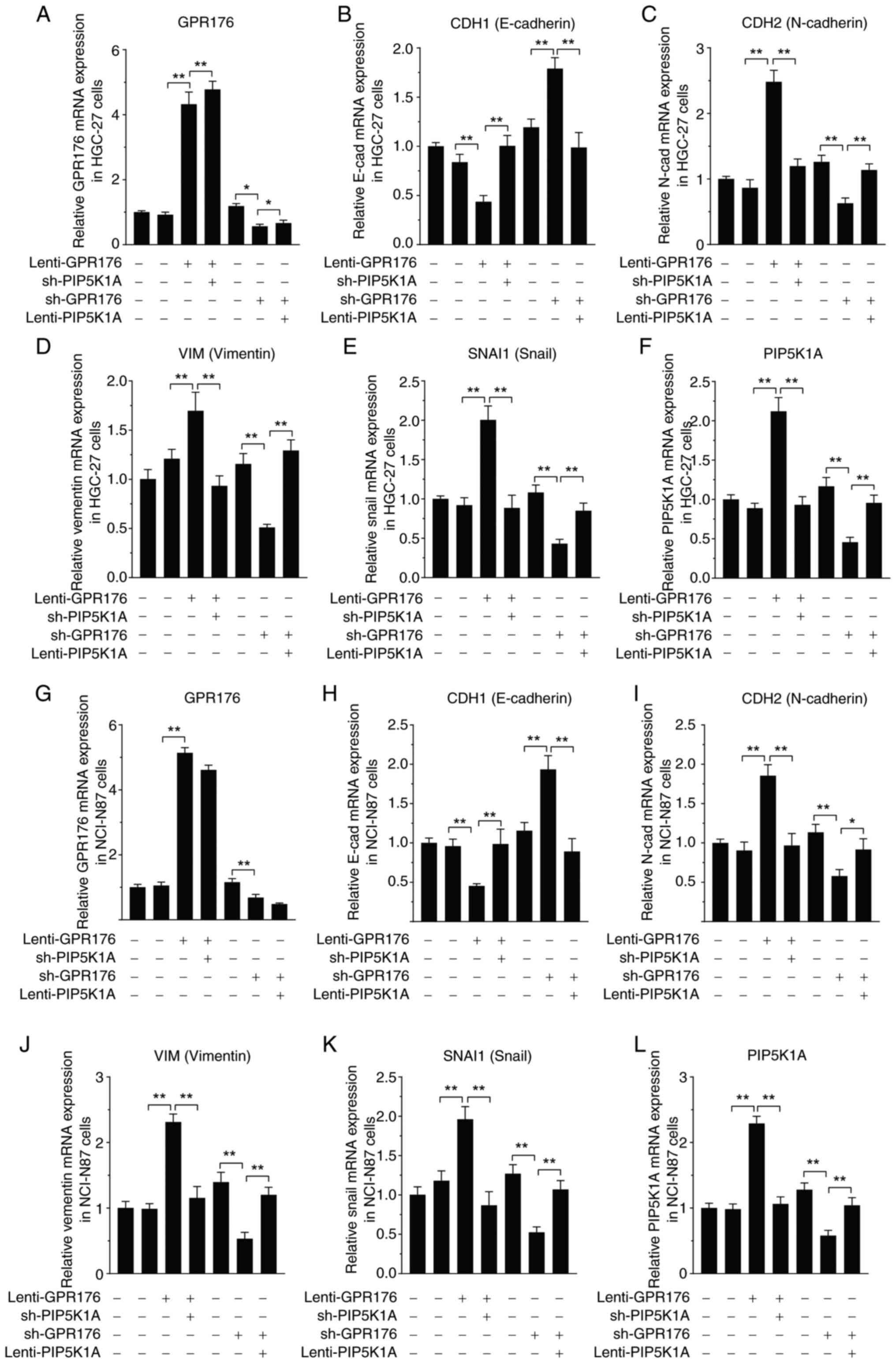

Downregulation of PIP5K1A prevents the

effects of GPR176 on cell migration, invasion, EMT and on the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

Previous studies have confirmed that PIP5K1A is an

upstream molecule in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway (30–33).

Analysis of RNA-seq data from the TCGA-STAD dataset in the present

study revealed a significant positive association between GPR176

and PIP5K1A expression (Fig. 1J).

Therefore, we hypothesized that GPR176 may activate the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway by inducing upregulation of PIP5K1A

expression. Interference and overexpression experiments of PIP5K1A

were performed based on the overexpression of GPR176 and the

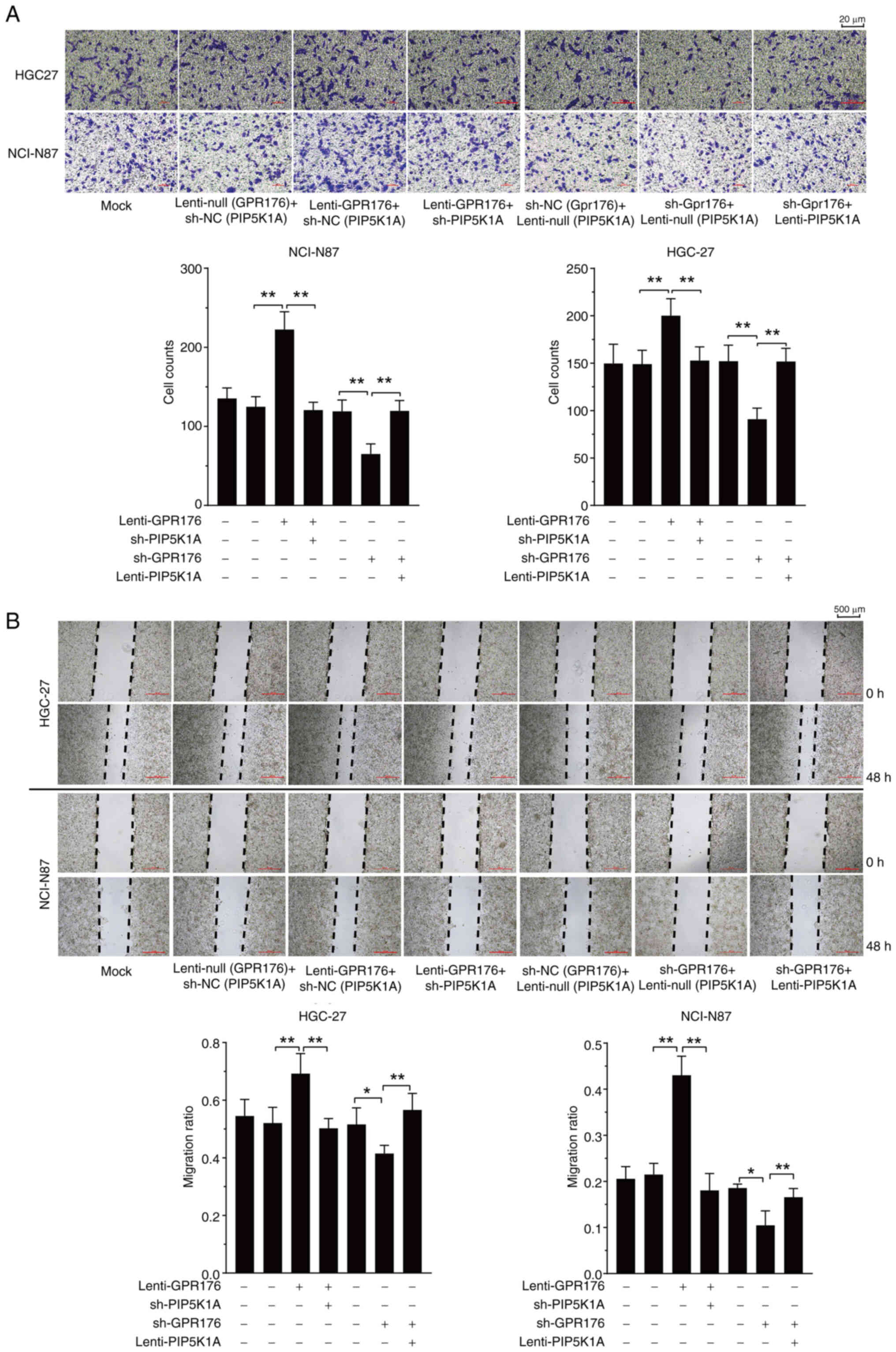

repression of GPR176. Analysis revealed that interference with

PIP5K1A expression significantly prevented the migration and

invasion induced by GPR176 overexpression (Fig. 5A and B). Conversely, downregulation

of PIP5K1A also significantly reversed the slowed migration and

invasion of gastric cancer cells caused by GPR176 knockdown

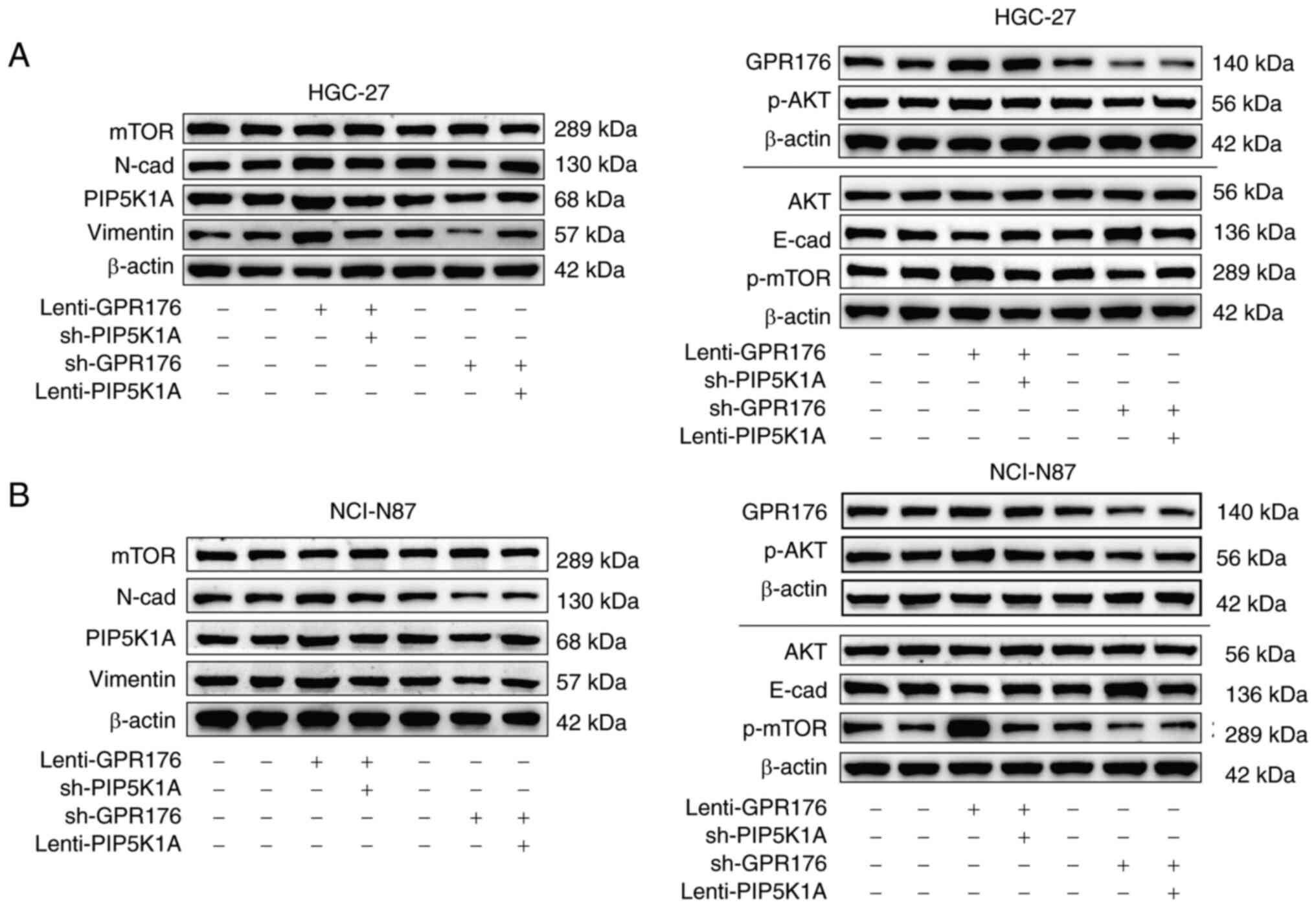

(Fig. 5A and B). Following this, WB

was carried out to evaluate the phosphorylation levels of molecules

within the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and the EMT signaling pathway,

along with assessing the expression levels of PIP5K1A. The

activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and EMT signaling pathway

after GPR176 upregulation was attenuated by the downregulation of

PIP5K1A. Conversely, the inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

and EMT signaling pathway after GPR176 downregulation was

counteracted by the OE of PIP5K1A (Fig.

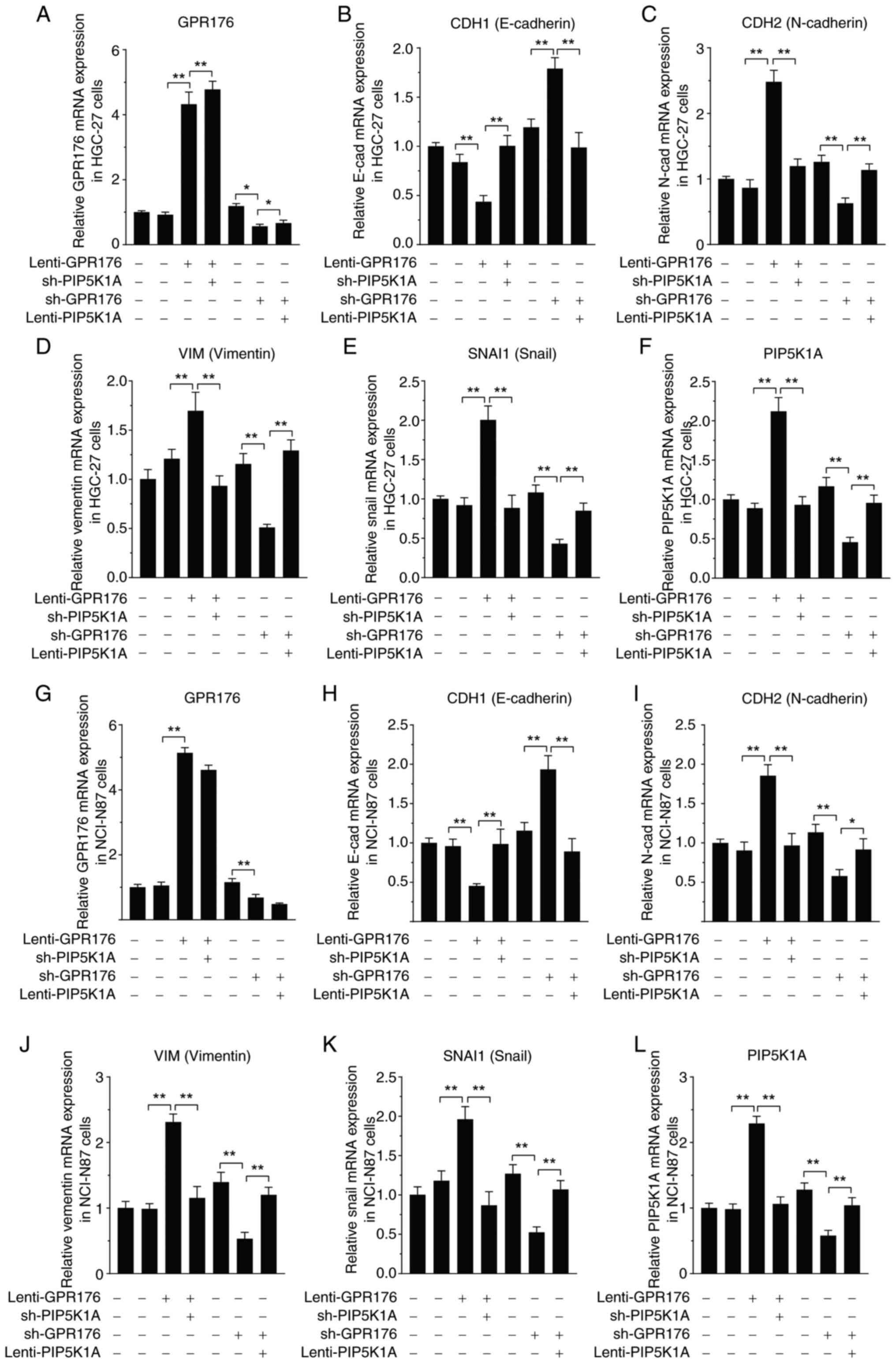

6A and B), with the corresponding bar chart shown in Fig. S3A and B. The results of the RT-qPCR

assay were in concordance with the aforementioned experiments,

indicating a preventing in changes to the mRNA expression levels of

molecules in the EMT signaling pathway after GPR176 upregulation,

which was suppressed by the downregulation of PIP5K1A in HGC-27 and

NCI-N87 cells; similarly, in HGC-27 and NCI-N87 cells, the

downregulation of GPR176 resulted in prevention of the mRNA

expression levels of molecules in the EMT signaling pathway, under

the upregulating influence of PIP5K1A (Fig. 7A-L).

| Figure 7.Genetic regulation of PIP5K1A

counteracts the effects of GPR176 on the expression of EMT pathway

genes at the mRNA level. Combined genetic regulation of GPR176 and

PIP5K1A on the expression of (A) GPR176 (B) CHD1 (E-cadherin), (C)

CHD2 (N-cadherin) (D) VIM (Vimentin), (E) SNAI1 (Snail), (F)

PIP5K1A in in HGC-27 cells. Combined genetic regulation of GPR176

and PIP5K1A on the expression of (G) GPR176, (H) CHD1 (E-cadherin),

(I) CHD2 (N-cadherin), (J) VIM (Vimentin), (K) SNAI1 (Snail), (L)

PIP5K1A in NCI-N87 cells. EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition;

sh-, short hairpin-; cad, cadherin. Statistical analysis was

performed using two-way ANOVA. **P<0.01, *P<0.05. |

The status of EMT and PI3K/AKT/mTOR

between para-cancer and cancer tissues, as well as the expression

of PIP5K1A and GPR176

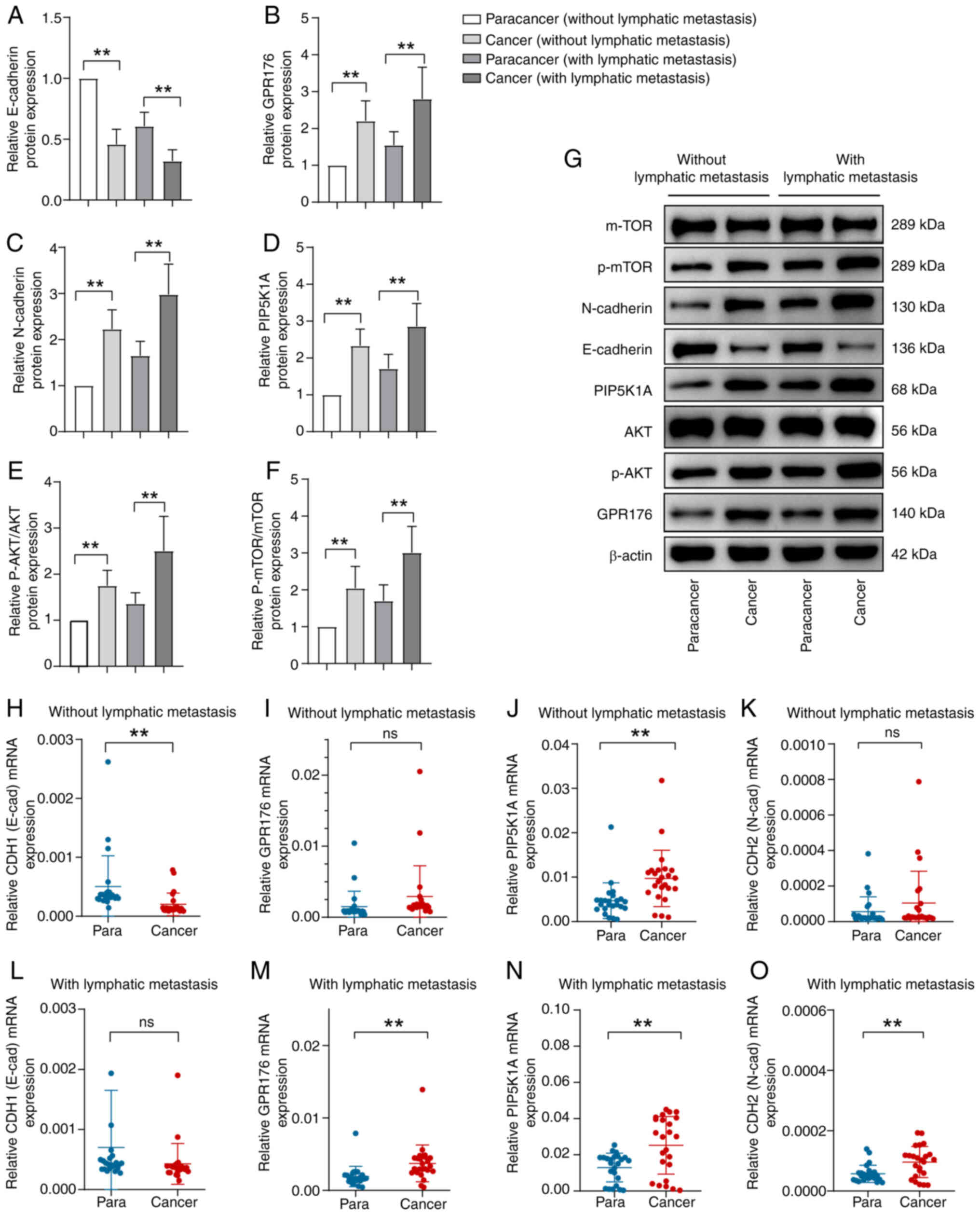

Firstly, patients with gastric cancer were

categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of

lymph node metastasis: Those with lymph node metastasis and those

without. Further classification was made based on histological

type, distinguishing between the para-cancer group and the cancer

group. Initially, WB was employed to assess the protein levels of

E-cadherin, N-cadherin, PIP5K1A, GPR176, AKT, p-AKT, mTOR and

p-mTOR in each group. The findings revealed that irrespective of

lymph node metastasis, the expression of E-cadherin in the cancer

group was significantly reduced compared with the para-cancer

group. Conversely, levels of N-cad, PIP5K1A, GPR176, p-AKT, p-mTOR,

p-AKT/AKT and p-mTOR/mTOR were increased in the cancer group

compared with the para-cancer group (Fig. 8A-F). The representative blots of WB

experiments are referenced in Fig.

8G.

Subsequently, validation of the expression levels of

key genes in the EMT pathway and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway,

as well as PIP5K1A and GPR186, was conducted using RT-qPCR. Among

patients without lymph node metastasis, no significant differences

were observed in GPR186 and CDH2 (N-cadherin) expression levels

between the para-cancer and cancer groups (Fig. 8I and K). However, CDH1 (E-cadherin)

expression was significantly reduced in the cancer group compared

with the para-cancer group (Fig.

8H). Conversely, PIP5K1A expression was markedly higher in the

cancer group compared with the para-cancer group (Fig. 8J). In patients with lymph node

metastasis, there were no significant differences in CDH1

expression between the para-cancer and cancer groups (Fig. 8L). Nevertheless, GPR186, CDH2 and

PIP5K1A expression levels were significantly increased in the

cancer group compared with the para-cancer group (Fig. 8M-O). In summary, the expression

levels of PIP5K1A and GPR176 were increased in the cancer group

compared with the para-cancer group. Additionally, activation of

the EMT pathway and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway was evident in the cancer

group.

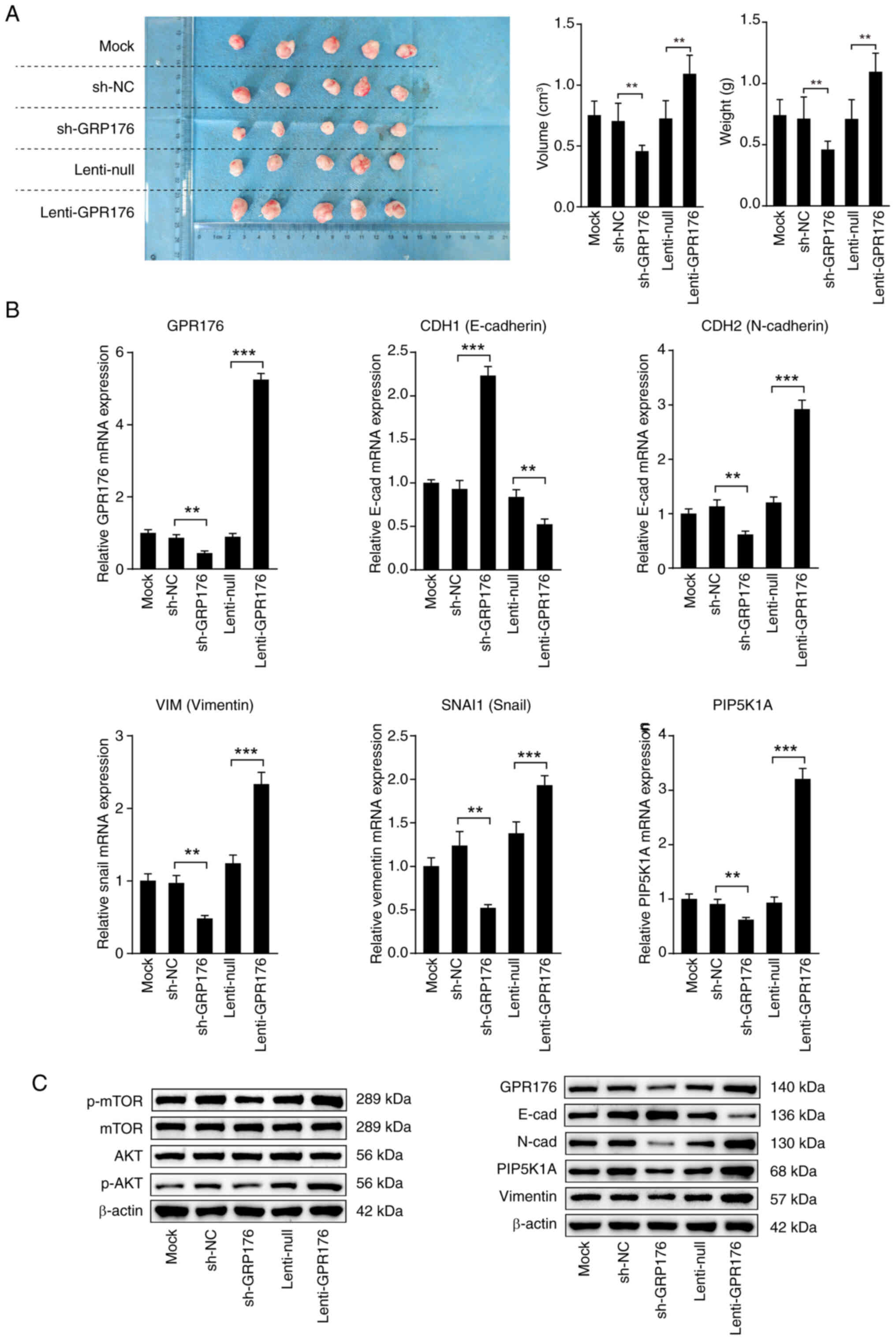

GPR176 promotes the growth of

transplanted tumors by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

In vitro experiments provided evidence that

GPR176 could activate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, facilitating EMT

and promoting cell proliferation by inducing the overexpression of

PIP5K1A. To further validate the role of GPR176 in gastric cancer,

a nude mouse subcutaneous tumor experiment was designed in the

present study to assess the influence of GPR176 expression on the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and EMT. In comparison with the Lenti-NC

group, the GPR176 upregulation group exhibited significantly larger

tumor volume and weight. Conversely, relative to the sh-NC group,

the sh-GPR176 group displayed a substantial reduction in tumor

volume and weight (Fig. 9A).

Subsequent examination of the mRNA expression levels of EMT pathway

molecules, consistent with the in vitro results, revealed

activation of the EMT pathway following GPR176 upregulation, while

the EMT signaling pathway was inhibited after GPR176 downregulation

(Fig. 9B). Western blot analysis

suggested the activation of the EMT and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways

following GPR176 upregulation, as indicated by increased levels of

key pathway markers. Conversely, GPR176 downregulation resulted in

changes indicative of pathway inhibition. (Fig. 9C), with the corresponding bar chart

shown in Fig. S4A-G.

Discussion

Gastric cancer is a highly malignant tumor

characterized by the absence of typical early symptoms, often

leading to late-stage diagnosis and missing of the optimal

treatment window (4,5). This poses several challenges for the

treatment of gastric cancer (43).

In the advanced stages, gastric cancer has usually spread to lymph

nodes or other organs, making treatment considerably more difficult

(44–46). Due to the different subtypes of

gastric cancer, each with different biological behaviors and

treatment responses, the development of universal treatment plans

is complex and requires more individualized and precise treatment

strategies (47,48). Some patients develop resistance to

conventional chemotherapeutic agents, leading to a decrease in

treatment efficacy and requiring constant adjustment of drug

combinations during treatment to overcome the adaptability of the

tumor (49,50). Given these challenges, there is an

urgent need for further research in the field of gastric cancer

treatment to develop more effective and personalized treatment

strategies.

GPR176 is generally considered to be associated with

circadian rhythms (26). However,

some researchers have begun to recognize its role in tumors. For

example, Tang et al (28)

found that GPR176 interacts with the G protein GNAS to inhibit

mitochondrial autophagy in colorectal cancer cells, thereby

promoting cancer progression. In the present study, compared with

normal gastric tissue, upregulation of GPR176 expression in gastric

cancer was observed, with significant differences in expression

between different TNM stages and tissue types. This heterogeneous

expression suggests that GPR176 may play different biological roles

in different subtypes of gastric cancer.

Through integrated analysis of data from TCGA and

GEO databases, it was clarified that high GPR176 expression is

significantly associated with shorter overall survival and

disease-free survival in patients with gastric cancer. This

suggests that GPR176 could serve as an independent prognostic

marker, providing a new molecular standard for the assessment of

patient survival. Similarly, researchers such as Yun et al

(29) have previously suggested

that GPR176 may also serve as a prognostic biomarker in breast

cancer.

Bioinformatic analysis revealed that the gene

expression profile regulated by the accumulation of GPR176 is

associated with signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR. This

suggests that GPR176 may be involved in the development of gastric

cancer via this signaling pathway. Further experimental

verification demonstrated an association between GPR176 and the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and provided an experimental basis

for understanding the specific role of GPR176 in cell

proliferation, survival and metastasis.

The PI3K signaling pathway carries out a key role in

the proliferation and progression of various cancer cells,

including gastric cancer (51,52).

Numerous previous studies have indicated that the PI3K signaling

pathway promotes the progression of gastric cancer through various

mechanisms, including inhibiting apoptosis, inducing drug

resistance, facilitating metastasis and promoting angiogenesis

(53–55).

After activation by PI3K and PIP2, AKT kinase

relocates downstream to the cell membrane, triggering its

conformational activation (56).

AKT carries out a key role in activating the PI3K axis and elevated

expression of AKT and p-AKT has been detected in >74% of gastric

cancer cases (57). Aberrant

expression of p-AKT is associated with the overexpression of PI3K

and HER2, and high levels of p-AKT are regarded as indicators of

tumor progression, metastasis, and poor prognosis in gastric cancer

(58).

Analysis of the TCGA molecular subtypes reveals that

the majority of gastric cancer cases studied display varying

degrees of PIK3CA gene mutations, along with amplifications of RTK

genes such as EGFR and HER2 (48).

Genomic amplifications markedly contribute to tumor progression.

Amplification of PIK3CA is associated with tumor progression,

prognosis and the development of gastric cancer resistance

(59). The substantial involvement

of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in gastric cancer

progression suggests that targeting this signaling axis holds

potential for cancer therapy (60).

The present study identified the upregulation of

GPR176 as a promoter of EMT in gastric cancer cells, thereby

revealing a mechanism that drives tumor invasion and metastasis.

In vitro assays confirmed that GPR176 overexpression

enhances cell migration and invasion, whereas its knockdown

produces the opposite effect. These findings highlight the pivotal

role of GPR176 in regulating EMT and suggest that it may serve as a

novel modulator of gastric cancer progression. Future studies

should further dissect the upstream regulators and downstream

effectors of GPR176 in EMT, as well as its interactions with other

EMT-related transcription factors and regulatory networks.

The present study also identified an association

between GPR176 and PIP5K1A, and that downregulation of PIP5K1A

prevented the effects of GPR176 on migration, invasion, EMT and

activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. This indicates that GPR176

may exert its tumor-promoting function, at least in part, through

synergistic regulation with PIP5K1A. Additional studies employing

gene knock-in models, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing or

co-immunoprecipitation assays are warranted to validate the direct

interaction between GPR176 and PIP5K1A and to elucidate their

precise molecular mechanisms. Although the present study

highlighted the involvement of GPR176 in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway, it is important to note that this pathway

represents a common oncogenic mechanism (61–63).

Future research should therefore investigate the potential upstream

regulators that modulate GPR176 expression, such as transcription

factors, epigenetic modifications or non-coding RNAs, which may

contribute to its dysregulation in gastric cancer. In addition,

downstream interactions of GPR176 beyond PI3K/AKT/mTOR, including

crosstalk with MAPK/ERK or Wnt/β-catenin pathways, may further

shape tumor cell proliferation, survival and metastatic behavior.

Exploring these upstream and downstream aspects will broaden the

understanding of GPR176-mediated oncogenic signaling and may

uncover novel therapeutic opportunities.

As a member of the G protein-coupled receptor

family, GPR176 remains relatively underexplored in both

physiological and pathological contexts. Findings of the present

study expand the current understanding of its role in gastric

adenocarcinoma, particularly in relation to cell signaling,

proliferation, invasion and metastasis. Given the high

heterogeneity of gastric cancer and the variable therapeutic

responses among patients, studying GPR176 expression and function

across tumor subtypes could contribute to the development of more

individualized treatment strategies. Furthermore, the observed

association between GPR176 expression and patient survival

underscores its potential as a prognostic biomarker and as a

candidate for risk stratification in clinical practice.

Furthermore, the findings of the present study

indicate that high GPR176 expression in gastric adenocarcinoma is

associated with tumor invasion, metastasis and poor prognosis,

highlighting its potential translational significance. GPR176 may

serve not only as a prognostic biomarker for assessing patient

survival and recurrence risk but also as a promising therapeutic

target due to its key role in tumor cell proliferation, migration

and activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Future studies should

further validate the predictive value of GPR176 in independent

patient cohorts and explore the feasibility of targeting GPR176

through small-molecule inhibitors, antibodies or gene-editing

strategies, providing new avenues for personalized therapy and

precision oncology.

Despite these insights, several limitations should

be acknowledged. First, the bioinformatics analyses were based on

retrospective datasets (TCGA-STAD and GSE66254) with limited sample

sizes, which may introduce selection bias. Second, although the

prognostic value and functional role of GPR176 were validated

through in vitro and in vivo experiments, the models

may not fully capture the complexity of the human tumor

microenvironment. Third, the mechanistic investigations mainly

focused on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and EMT, while other

potential pathways or crosstalk mechanisms remain unexplored.

Finally, the translational relevance of GPR176 as a biomarker or

therapeutic target requires further validation in large-scale,

prospective and independent clinical cohorts. Addressing these

limitations will be key for advancing the clinical application of

GPR176 in gastric cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Medical Excellence Award

Funded by the Creative Research Development Grant from the First

Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (grant no.

202204), Self-funded Research Project of Health Commission of

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (grant no. Z-A20220397) and Hubei

Chen Xiaoping Science and Technology Development Foundation (grant

no. CXPJJH122002-027).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

GM conceived and designed the research program; GM

and KL contributed to acquisition of data; CH, HR, DL, GZ and JC

performed data analysis. GM, ZH, HR and KL performed the

experiments. KL wrote the manuscript. GM guided and supervised the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All

authors made a significant contribution to the work reported,

whether that is in the conception, study design, execution,

acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these

areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the

article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have

agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and

agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The investigation had been approved by the ethics

committee of Guangxi Medical University the first affiliated

hospital, Nanning, China (approval no. 2023-S243-01)]. All methods

in this research were carried out in accordance with Declaration of

Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

GPR176

|

G protein-coupled receptor 176

|

|

PIP5K1A

|

phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate

5-kinase type 1 α

|

|

DAVID

|

Database for Annotation, Visualization

and Integrated Discovery

|

|

GO

|

gene ontology

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

WB

|

western blotting

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Guo HX, Wang Q, Wang C, Yin QC, Huo HZ and

Yin BH: Secular trends in gastric and esophageal cancer

attributable to dietary carcinogens from 1990 to 2019 and

projections until 2044 in China: Population-based study. JMIR

Public Health Surveill. 9:e484492023. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Maomao C, He L, Dianqin S, Siyi H, Xinxin

Y, Fan Y, Shaoli Z, Changfa X, Lin L, Ji P and Wanqing C: Current

cancer burden in China: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention.

Cancer Biol Med. 19:1121–1138. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang Y, Yan Q, Fan C, Mo Y, Wang Y, Li X,

Liao Q, Guo C, Li G, Zeng Z, et al: Overview and countermeasures of

cancer burden in China. Sci China Life Sci. 66:2515–2526. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Qiu H, Cao S and Xu R: Cancer incidence,

mortality, and burden in China: A time-trend analysis and

comparison with the United States and United Kingdom based on the

global epidemiological data released in 2020. Cancer Commun (Lond).

41:1037–1048. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van

Grieken NC and Lordick F: Gastric cancer. Lancet. 396:635–648.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sekiguchi M, Oda I, Matsuda T and Saito Y:

Epidemiological trends and future perspectives of gastric cancer in

Eastern Asia. Digestion. 103:22–28. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li GZ, Doherty GM and Wang J: Surgical

management of gastric cancer: A review. JAMA Surg. 157:446–454.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hong J, Tsai Y, Novick D, Hsiao FCH, Cheng

R and Chen JS: The economic burden of advanced gastric cancer in

Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res. 17:6632017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xu H and Li W: Early detection of gastric

cancer in China: Progress and opportunities. Cancer Biol Med.

19:1622–1628. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Machlowska J, Baj J, Sitarz M, Maciejewski

R and Sitarz R: Gastric cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors,

classification, genomic characteristics and treatment strategies.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:40122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen D, Fu M, Chi L, Lin L, Cheng J, Xue

W, Long C, Jiang W, Dong X, Sui J, et al: Prognostic and predictive

value of a pathomics signature in gastric cancer. Nat Commun.

13:69032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cao R, Gong L and Dong D: Pathological

diagnosis and prognosis of gastric cancer through a multi-instance

learning method. EBioMedicine. 73:1036712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen Y, Chen T and Fang JY: Burden of

gastrointestinal cancers in China from 1990 to 2019 and projection

through 2029. Cancer Lett. 560:2161272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li H, Zhang H, Zhang H, Wang Y, Wang X and

Hou H; Global Health Epidemiology Reference Group, : Survival of

gastric cancer in China from 2000 to 2022: A nationwide systematic

review of hospital-based studies. J Glob Health. 12:110142022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lordick F, Carneiro F, Cascinu S, Fleitas

T, Haustermans K, Piessen G, Vogel A and Smyth EC; ESMO Guidelines

Committee. Electronic address, : simpleclinicalguidelines@esmo.org:

Gastric cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis,

treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 33:1005–1020. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Guan WL, He Y and Xu RH: Gastric cancer

treatment: Recent progress and future perspectives. J Hematol

Oncol. 16:572023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Chao J,

Cooke D, Corvera C, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Fanta P, et al:

Gastric cancer, version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines

in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 20:167–192. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kobayashi D and Kodera Y: Intraperitoneal

chemotherapy for gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Gastric

Cancer. 20 (Suppl 1):S111–S121. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Boilève J, Touchefeu Y and Matysiak-Budnik

T: Clinical management of gastric cancer treatment regimens. Curr

Top Microbiol Immunol. 444:279–304. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Patel TH and Cecchini M: Targeted

therapies in advanced gastric cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol.

21:702020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li K, Zhang A, Li X, Zhang H and Zhao L:

Advances in clinical immunotherapy for gastric cancer. Biochim

Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1876:1886152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kawakami H and Okamoto I: MET-targeted

therapy for gastric cancer: The importance of a biomarker-based

strategy. Gastric Cancer. 19:687–695. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Joshi SS and Badgwell BD: Current

treatment and recent progress in gastric cancer. CA Cancer J Clin.

71:264–279. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Doi M, Murai I, Kunisue S, Setsu G, Uchio

N, Tanaka R, Kobayashi S, Shimatani H, Hayashi H, Chao HW, et al:

Gpr176 is a Gz-linked orphan G-protein-coupled receptor that sets

the pace of circadian behaviour. Nat Commun. 7:105832016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Nakagawa S, Nguyen Pham KT, Shao X and Doi

M: Time-restricted G-protein signaling pathways via GPR176,

Gz, and RGS16 Set the pace of the master circadian clock

in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Int J Mol Sci. 21:50552020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yamaguchi Y, Murai I, Takeda M, Doi S,

Seta T, Hanada R, Kangawa K, Okamura H, Miyake T and Doi M:

Nmu/Nms/Gpr176 triple-deficient mice show enhanced light-resetting

of circadian locomotor activity. Biol Pharm Bull. 45:1172–1179.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tang J, Peng W, Ji J, Peng C, Wang T, Yang

P, Gu J, Feng Y, Jin K, Wang X and Sun Y: GPR176 promotes cancer

progression by interacting with G protein GNAS to restrain cell

mitophagy in colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e22056272023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yun WJ, Xue H, Yang N, Xiao LJ, Sun HZ and

Zheng HC: Oncogenic roles of GPR176 in breast cancer: A potential

marker of aggressiveness and a potential target of gene therapy.

Clin Transl Oncol. 25:3042–3056. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yun WJ, Li J, Yin NC, Zhang CY, Cui ZG,

Zhang L and Zheng HC: The promoting effects of GPR176 expression on

proliferation, chemoresistance, lipogenesis and invasion of

oesophageal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 149:14641–14655. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang Y, Gu X, Zhu F, Li Y, Huang Y and Ju

S: High expression of GPR176 predicts poor prognosis of gastric

cancer patients and promotes the proliferation, migration, and

invasion of gastric cancer cells. Sci Rep. 13:93602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ni L, Chen S, Liu J, Li H, Zhao H, Zheng

C, Zhang Y, Huang H, Huang J, Wang B and Lin C: GPR176 is a

biomarker for predicting prognosis and immune infiltration in

stomach adenocarcinoma. Mediators Inflamm. 2023:71235682023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

East MP, Laitinen T and Asquith CRM:

PIP5K1A: A potential target for cancers with KRAS or TP53

mutations. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 19:4362020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ding T, Ji J, Zhang W, Liu Y, Liu B, Han

Y, Chen C and Yu L: The phosphatidylinositol

(4,5)-bisphosphate-Rab35 axis regulates migrasome formation. Cell

Res. 33:617–627. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yin M and Wang Y: The role of PIP5K1A in

cancer development and progression. Med Oncol. 39:1512022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sarwar M, Syed Khaja AS, Aleskandarany M,

Karlsson R, Althobiti M, Ødum N, Mongan NP, Dizeyi N, Johnson H,

Green AR, et al: The role of PIP5K1α/pAKT and targeted inhibition

of growth of subtypes of breast cancer using PIP5K1α inhibitor.

Oncogene. 38:375–389. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu WT, Li YJ, Feng AZ, Li L, Huang T, Xu

AD and Lyu J: Data mining in clinical big data: The frequently used

databases, steps, and methodological models. Mil Med Res.

8:442021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Somerville TDD, Wiseman DH, Spencer GJ,

Huang X, Lynch JT, Leong HS, Williams EL, Cheesman E and

Somervaille TC: Frequent derepression of the mesenchymal

transcription factor gene FOXC1 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer

Cell. 28:329–342. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Glaviano A, Foo ASC, Lam HY, Yap KCH,

Jacot W, Jones RH, Eng H, Nair MG, Makvandi P, Geoerger B, et al:

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies

in cancer. Mol Cancer. 22:1382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wong SHM, Fang CM, Chuah LH, Leong CO and

Ngai SC: E-cadherin: Its dysregulation in carcinogenesis and

clinical implications. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 121:11–22. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Jim MA, Pinheiro PS, Carreira H, Espey DK,

Wiggins CL and Weir HK: Stomach cancer survival in the United

States by race and stage (2001–2009): Findings from the CONCORD-2

study. Cancer. 123 (Suppl 24):S4994–S5013. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Budginaite E, Kloft M, van Kuijk SMJ,

Canao PA, Kooreman LFS, Pennings AJ, Magee DR, Woodruff HC and

Grabsch HI: The clinical importance of the host anti-tumour

reaction patterns in regional tumour draining lymph nodes in

patients with locally advanced resectable gastric cancer: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 26:847–862.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Xia X, Zhang Z, Zhu C, Ni B, Wang S, Yang

S, Yu F, Zhao E, Li Q and Zhao G: Neutrophil extracellular traps

promote metastasis in gastric cancer patients with postoperative

abdominal infectious complications. Nat Commun. 13:10172022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhang ZY and Ge HY: Micrometastasis in

gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 336:34–45. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cristescu R, Lee J, Nebozhyn M, Kim KM,

Ting JC, Wong SS, Liu J, Yue YG, Wang J, Yu K, et al: Molecular

analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with

distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med. 21:449–456. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma.

Nature. 513:202–209. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wei L, Sun J, Zhang N, Zheng Y, Wang X, Lv

L, Liu J, Xu Y, Shen Y and Yang M: Noncoding RNAs in gastric

cancer: Implications for drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 19:622020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yuan L, Xu ZY, Ruan SM, Mo S, Qin JJ and

Cheng XD: Long non-coding RNAs towards precision medicine in

gastric cancer: Early diagnosis, treatment, and drug resistance.

Mol Cancer. 19:962020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Willems L, Tamburini J, Chapuis N, Lacombe

C, Mayeux P and Bouscary D: PI3K and mTOR signaling pathways in

cancer: New data on targeted therapies. Curr Oncol Rep. 14:129–138.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zhou X, Li T, Xie H, Huang H, Yang K, Zeng

X and Peng T: HBV-induced N6 methyladenosine modification of PARP1

enhanced AFB1-related DNA damage and synergistically contribute to

HCC. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 298:1182542025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Li H, Prever L, Hirsch E and Gulluni F:

Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in breast cancer. Cancers

(Basel). 13:35172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Fresno Vara JA, Casado E, de Castro J,

Cejas P, Belda-Iniesta C and González-Barón M: PI3K/Akt signalling

pathway and cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 30:193–204. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhou X, Luo J, Xie H, Wei Z, Li T, Liu J,

Liao X, Zhu G and Peng T: MCM2 promotes the stemness and sorafenib

resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via hippo signaling.

Cell Death Discov. 8:4182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Vivanco I and Sawyers CL: The

phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev

Cancer. 2:489–501. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Almhanna K, Strosberg J and Malafa M:

Targeting AKT protein kinase in gastric cancer. Anticancer Res.

31:4387–4392. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhou XD, Chen HX, Guan RN, Lei YP, Shu X,

Zhu Y and Lv NH: Protein kinase B phosphorylation correlates with

vascular endothelial growth factor A and microvessel density in

gastric adenocarcinoma. J Int Med Res. 40:2124–2134. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Shi J, Yao D, Liu W, Wang N, Lv H, Zhang

G, Ji M, Xu L, He N, Shi B and Hou P: Highly frequent PIK3CA

amplification is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer.

BMC Cancer. 12:502012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Kobayashi I, Semba S, Matsuda Y, Kuroda Y

and Yokozaki H: Significance of Akt phosphorylation on tumor growth

and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human gastric

carcinoma. Pathobiology. 73:8–17. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang Y, Kwok-Shing Ng P, Kucherlapati M,

Chen F, Liu Y, Tsang YH, de Velasco G, Jeong KJ, Akbani R,

Hadjipanayis A, et al: A Pan-cancer proteogenomic atlas of

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway alterations. Cancer Cell. 31:820–832.e3.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Janku F, Yap TA and Meric-Bernstam F:

Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: Are we making headway? Nat

Rev Clin Oncol. 15:273–291. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Okkenhaug K, Graupera M and Vanhaesebroeck

B: Targeting PI3K in cancer: Impact on tumor cells, their

protective stroma, angiogenesis, and immunotherapy. Cancer Discov.

6:1090–1105. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|