Introduction

Perinatal care remains a major health concern among

mothers and children worldwide. In Japan, 99% of women plan to give

birth in obstetrics facilities, clinics and hospitals, under the

care of obstetricians. When obstetric complications arise, a

considerable proportion of pregnant and parturient women are sent

from referring facilities (primary maternity clinics, midwifery

homes, or district and general hospitals) to Emergency Obstetric

and Neonatal Care (EONC) centers by the ambulance or

doctor-helicopter service (1). In

line with the government policy in Japan, the ambulance functions

as an emergency transfer team and works 24 h a day, every day.

Preterm birth is one of the most important complications of

pregnancy and plays a major role in neonatal mortality and

morbidity (2-4).

Furthermore, major causes of direct maternal deaths from pregnancy

complications include peripartum hemorrhage, amniotic fluid

embolism, pulmonary embolism and preeclampsia (5,6).

The current maternal mortality rate in Japan, which is estimated to

be approximately 4 in 100,000 deliveries, is similar to that

observed in other developed countries (6). Previous researchers have identified

that inappropriate referral is an important factor associated with

maternal mortality and morbidity (5).

A shortage of obstetrician resources and excessive

workloads have been encountered in Japan, which may limit the

provision of comprehensive EONC and affect the quality of care

(7). In 2006, a serious incident

related to interfacility transfer (IFT) occurred in Nara

Prefecture, Japan. The patient suffered from a severe headache and

loss of consciousness following the onset of labor. Finally, 18

hospitals refused care and treatment due to the lack of

availability of both a maternal bed and a neonatal bed, as well as

due to the obstetricians' increased workload. The patient was thus

transferred outside of Nara Prefecture (Out-of-Nara transfer) and

died of intracranial hemorrhage after the patient was transferred

and following the attempted transfers to other hospitals which did

not accept the patient. Realizing the above situation, the

Governmental Organization in Nara prefecture has established the

Council for Perinatal Care (CPC) Committee, with responsibility for

reorganizing the IFT system and initiating a population-based

perinatal and neonatal registry. At the time, the EONC centers

often lacked human resources to safely manage women with severe

maternal and fetal complications. Since 2007, in order to improve

the obstetric and neonatal care, the CPC Committee put forward a

number of recommendations regarding the effective communication

between referring facilities and referred facilities.

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of a

newly established IFT system and medical coverage of IFT cases from

2006 to 2017.

Data collection and methods

A newly established IFT system

We used nationwide data in the vital statistics in

Japan on the estimated population of 1,356,950 and 9,626 expected

deliveries per year in Nara Prefecture in 2017 (the vital

statistics published by Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in

Japan, 2018; https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/kakutei16/index.html

and http://www.stat.go.jp/data/ssds/).

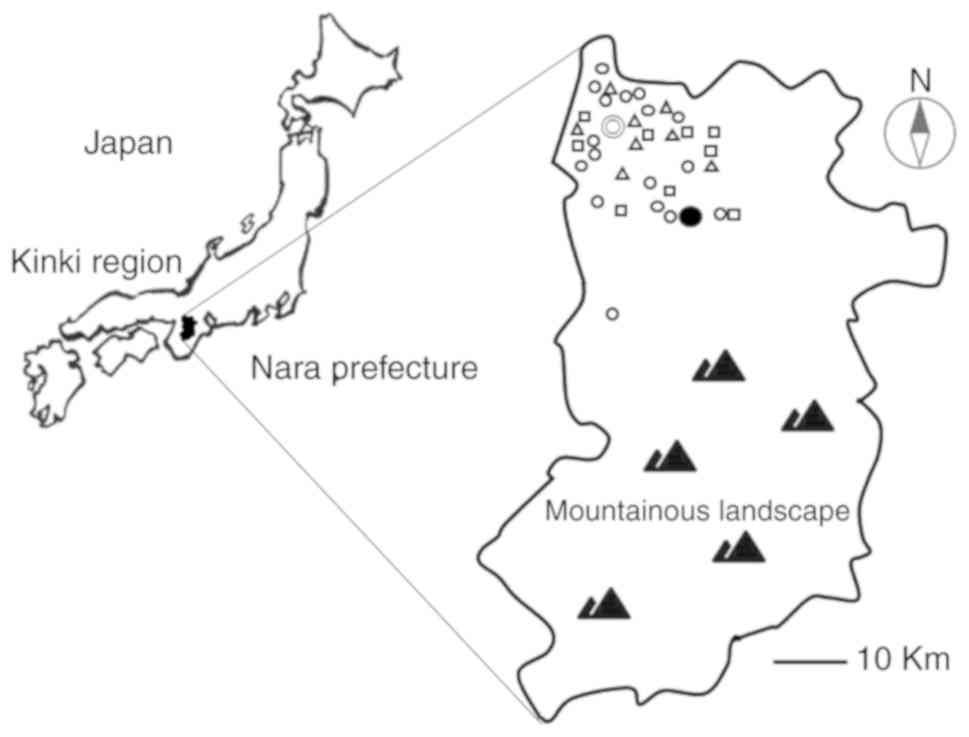

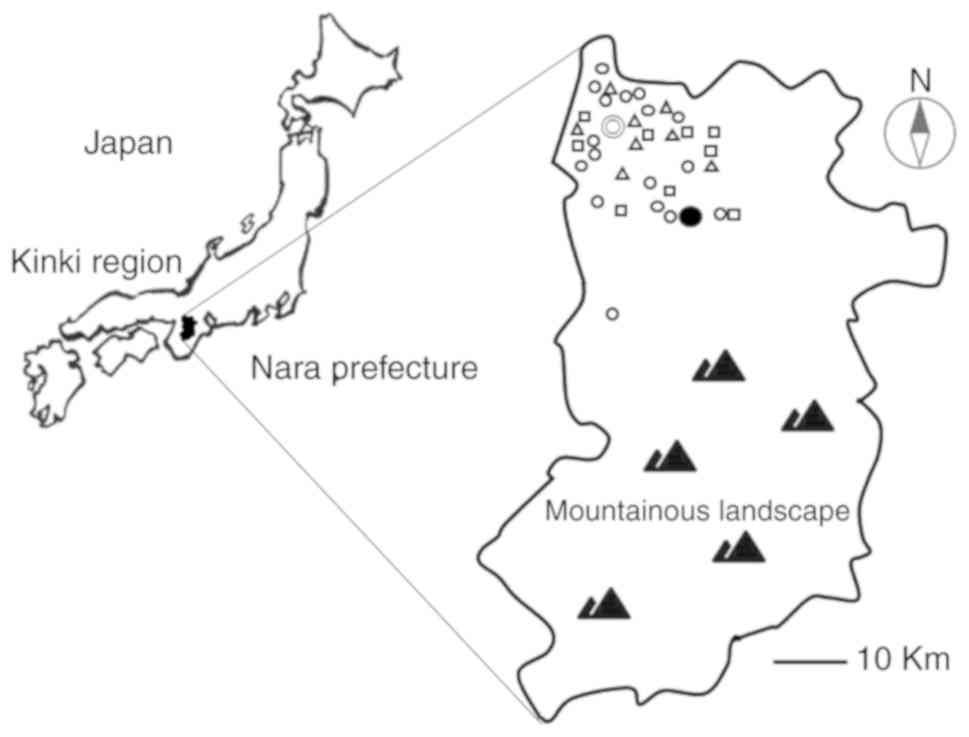

Nara prefecture is an inland prefecture located in Kinki region.

The geographical features in Nara Prefecture are basically a basin

and mountainous region. The northern part is low and flat, and

there are no barriers in accessing medical services. By contrast,

the southern part is mostly mountainous landscape. The habitants

live in hard-to-reach mountainous areas and have difficulties in

accessing medical services. Women plan to give birth in one of four

settings: Freestanding obstetrician-led clinics (approximately

54.2% of all births), freestanding midwife-led units (2.2%), the

prefectural-level district and general hospitals (28.9%), and a

tertiary hospital (14.7%). In 2006, at the beginning of this study,

there were four prefectural-level hospitals [Nara Medical

University (NMU), Nara Prefecture General Medical Center (NPGMC),

Tenri Hospital and Kindai University Nara Hospital] which have

specialist obstetric, pediatric, anesthetic and emergency services

onsite, seven district and general hospitals with the functioning

operation theater for obstetric and gynecological care, 17 primary

clinics staffed by obstetricians and nine midwifery homes (primary

level maternity units staffed by trained midwives). The majority of

the hospitals and clinics were located in the northern part of the

prefecture. The locations of the primary clinics, midwifery homes,

district and general hospitals, NMU and NPGMC are illustrated in

Fig. 1.

| Figure 1.Map of Nara Prefecture showing the

location of primary maternity clinics (n=16), midwifery homes

(n=8), or district and general hospitals (n=9), and the EONC

centers in 2017. In the map, the symbols indicate the following: ○,

Primary maternity clinics (n-16); Δ, midwifery homes (n-8); □,

district and general hospitals (n=9); ●, NMU; ⦾, NPGMC (EONC

centers). EONC centers, emergency obstetric and neonatal care

centers; NMU, Nara Medical University; NPGMC, Nara Prefecture

General Medical Center. |

Obstetricians in obstetrics-gynecology clinics and

professional midwives contribute to an uncomplicated physiological

birth. They sometimes confront unmet needs for emergency obstetric

care unavailable at their clinics, midwifery homes, or district and

general hospitals. When women are diagnosed as having maternal and

fetal complications, they are referred to EONC centers for

appropriate care. EONC was available in only two of 11 hospitals;

one is a tertiary care facility hospital of NMU (located in the

central part of the prefecture) and the other is a

prefectural-level hospital of NPGMC (located in the northern

district of the prefecture). Multiple barriers at the time,

including workforce shortage (shortage of obstetricians and nursing

staffs), reduced service capability after standard working hours,

excessive workloads of obstetricians, EONC center crowding and

hospital bed shortage and poor collaboration between NMU and NPGMC,

led the lack of availability and access to timely and appropriate

emergency obstetric care. The emergency ambulance was available;

however, an obstetrician of referring facilities or the land

ambulance crew in charge of IFT had to often identify a transfer

destination by oneself. A majority of specialists, including

obstetricians, neonatologists and gynecologists, had unresolved

problems with respect to job stress and had the negative impact of

job-related satisfaction, work-family conflict and working in a

rural area. Before 2006, there was a major public health concern in

perinatal care due to an inadequate IFT program and the low

referral coverage of complicated deliveries. The conflicts emerged

between government and obstetricians at the point of the process of

and policy recommendations for improving perinatal care management

systems.

First, under the leadership of the government, the

CPC Committee was set up to combat the various problems that

obstruct perinatal care. To combat the issue of IFTs, the CPC

Committee set up and reorganized the EONC centers in the tertiary

NMU Hospital as Comprehensive Centers for Perinatal Medicine in

2008 and then NPGMC hospital as Regional Centers for Perinatal

Medicine in 2010, respectively. Two EONC centers were reorganized

through the selection, integrated arrangements and concentration of

obstetric facilities, and requested to build a 24-h communication

network system for the transfer of women with obstetric

complications from referring facilities to the EONC centers. To

ensure sufficient medical coverage at all times, the traditional

overnight on-call and standby duties were assigned to obstetricians

in NMU and NPGMC. Specialized maternal and neonatal care services

were offered in a separate maternal-fetal intensive care unit

(MFICU) and neonatology unit (NICU). We proposed a team composed of

specialists from multiple disciplines (maternal-fetal medicine,

perinatology, neonatology, gynecology with surgical skills,

obstetric anesthesiology, interventional radiology, cardiology,

pulmonology, advanced midwives and nurse specialists etc.). With

this team-based approach, they strongly cooperated with each other

to establish a support system. Further attempts were approached

with careful triage protocol development. The CPC Committee has

achieved a consensus that preterm labor/birth and premature rupture

of membranes between 22+0 and 27+6 weeks of gestation requires an

intensive care in the NMU Hospital, while preterm labor with a

gestational age of >28 weeks with an estimated fetal body weight

>1,000 g is managed by prolonged tocolytic regimens in the NPGMC

Hospital. Since it is very difficult to save the lives of newborns,

pregnant women with a gestational age of <22+0 weeks do not

require an intensive care in EONCs. If women fulfilled the specific

referral criteria (Table I), they

have to be properly transferred from referring facilities to either

of the two EONC centers by an ambulance, with the distance between

1 and 20 km (up to 0.7 h drive one way to the furthest clinics). At

the start of the IFT program, full or optimal coverage of

complicated deliveries had not yet been achieved.

| Table ICriteria for ambulance referrals to

EONC centers of women at risk of or with an obstetric

complication. |

Table I

Criteria for ambulance referrals to

EONC centers of women at risk of or with an obstetric

complication.

| Maternal complication

with or without organ dysfunction: |

| | Cardiovascular or

renal pathologies, severe hypertension or stroke, diabetes, asthma,

appendicitis, enterocolitis, and infections. |

| Specified critical

interventions: |

| | Need massive blood

transfusion, ventilation and hysterectomy |

| Obstetric

complications: |

| | Prematurity <36

weeks gestation |

| | Premature rupture of

membranes <36 weeks gestation |

| | Hypertensive

disorders of pregnancy/Preeclampsia/eclampsia |

| | Placental

abruption |

| | Placenta previa |

| | Multiple

pregnancy |

| | Pregnant women

without antenatal health care |

| | Non-reassuring fetal

status |

| | Fetal growth

restriction |

| | Intrauterine fetal

death |

| | Malpresentation of

the fetus/umbilical cord |

| | Abdominal pain during

pregnancy |

| | Bleeding during

pregnancy |

| | Postpartum

hemorrhage |

| | Postpartum

sepsis |

Second, there is growing interest in the

effectiveness of task shifting that is an important government

policy option to improve workforce shortages of an obstetrician

(8). Professional midwives have

provided obstetric care and reproductive healthcare for normal

deliveries under the guidance of obstetricians. Since 2011,

midwives in NMU Hospitals were responsible for labor and delivery

care in a low-risk midwifery-led unit. The intense, hands-on

training has been provided in order to improve their skills in the

study meetings of the Japan Association of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists and Japan Academy of Midwifery of Nara

prefecture.

Third, the government programs employed an

obstetrician as a transfer coordinator. Telephone-based services by

a transfer coordinator can provide valuable informational and

practical support for IFTs. A five-point demand was proposed based

on the agreement by the CPC Committee as follows: i) An

obstetrician, midwife, or nurse in referring facilities rides in

the ambulance for the care in principle. The ambulances are well

equipped with a means of communication, EONC treatment protocols, a

patient stretcher, oxygen, drugs, ECG monitor and pulse oximeter

that could be administered in the ambulance by the accompanying

medical staffs en route to emergency obstetric hospitals. ii) In

2015, full-scale 24-h communication network began using

telephone-based services by a transfer coordinator. The

implementation of an emergency referral network includes an

efficient coordination by a transfer coordinator and an effective

communication. Without taking a labor in the referring facilities,

the transfer coordinator can understand an obstetrician's need,

taking each facility's limitations and acceptance into

consideration and can objectively identify a destination. An

optimal combination of the definitive destination avoiding delay

and any necessary support to manage the patient can be provided

over the cell phone to the ambulance medical staffs by the transfer

coordinator. iii) If all beds are filled with patients in EONC

centers, the IFT patient will be transferred from the referring

facilities to emergency obstetric hospitals outside of the

prefecture limits (the Out-of-Nara transfer). iv) If the ambulance

arrives at the referring facilities following vaginal delivery, the

woman and neonate will be transferred to emergency hospitals, even

though she does not require emergency postpartum care. v) Our

effective emergency medical services system includes a timely

dispatch of one ambulance car with special equipment such as a

portable incubator for neonatal transport stationed at the NPGMC

hospital. Ambulance use is free of charge.

Finally, perinatal health registries were developed

in Nara prefecture in 1997. In 2006, the government established a

standing committee to focus on emergency perinatal care. The Board

of the CPC Committee was authorized to design, approve and finance

observational studies in relevant scientific fields to ensure the

quality of community perinatal care services. A hospital-based

perinatal registry was collected, validated, managed, analyzed and

published, which was conducted by an underlying organization of the

CPC Committee at an annual meeting. The publication of the ‘Annual

Report of the Epidemiology and Management regarding Emergency

Obstetric and Neonatal Care’ is a project initiated by the

Committee (http://www.pref.nara.jp/46607.htm). Recent summary

data published through releasing an annual report would be helpful

to strengthen collaboration among critical care staffs and

physicians.

Study design and population

This is a retrospective time series study using a

longitudinal design between January, 2006 and December, 2017. All

facilities were invited to participate in the registry. There are

35 hospitals with deliveries in Nara Prefecture and only 4

hospitals (NMU, NPGMC, Tenri Hospital and Kindai University Nara

Hospital) accept patients with obstetric and neonatal

complications. Transferred patients were defined as either patients

that transported from the primary facilities to EONC centers or

those with the Out-of-Nara transfer. The annual number of and

reasons for IFTs was registered in the CPC Committee during the

study period.

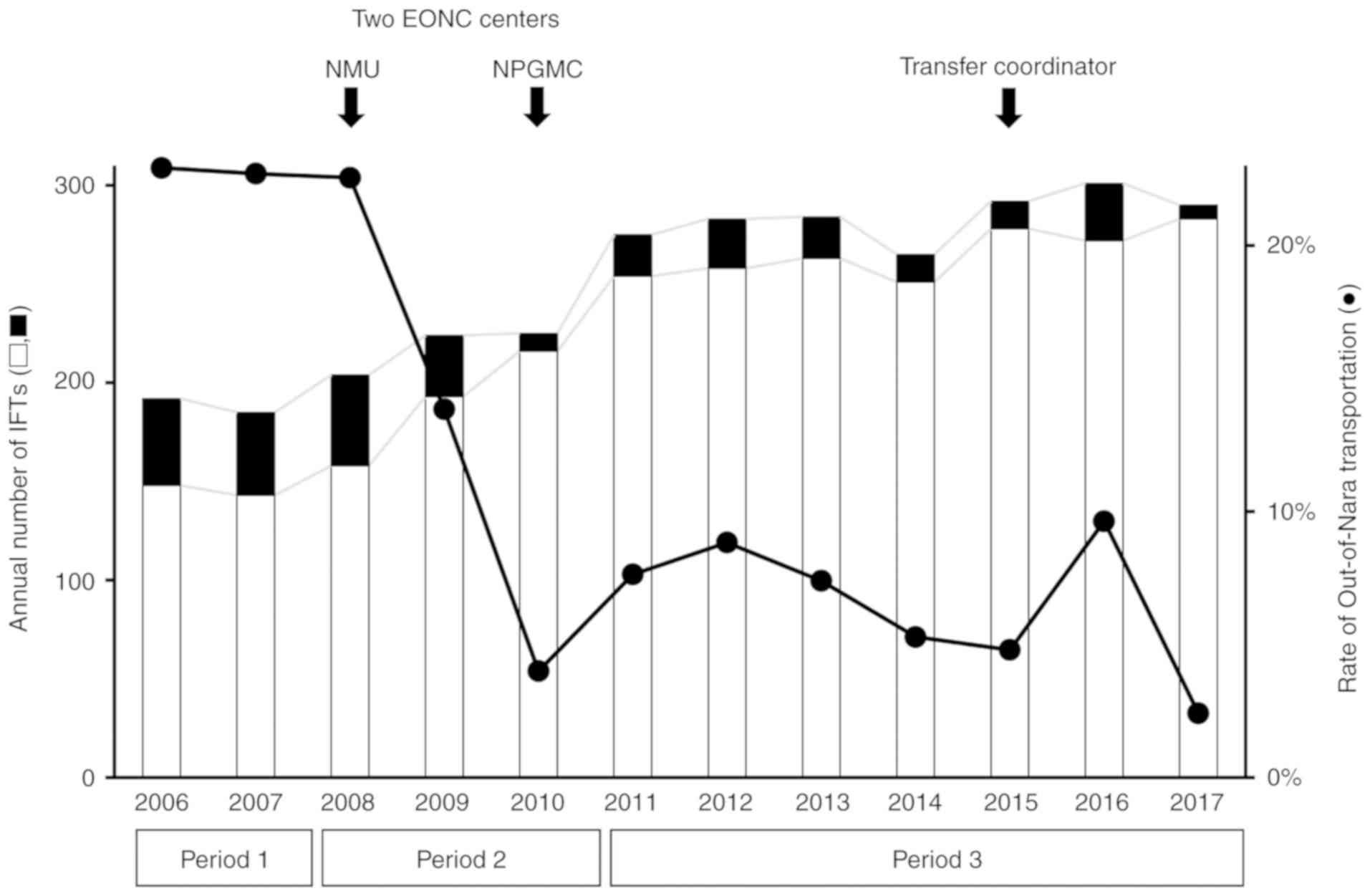

The patients were divided into three periods

according to the reorganization date as follows: Between 2006-2007

(before reorganization, Period 1), 2008-2010 (one reorganization,

Period 2) and between 2011-2017 (two reorganization and an

efficient coordination, Period 3). During Period 2, the NMU EONC

center officially commenced in order to improve the maternal and

neonatal care system. During Period 3, the NPGMC EONC center was

also officially commenced and IFTs were then timely coordinated by

a transfer operator who can identify a transfer destination.

Transfer coordinators would be required to keep the entire

management smooth and safe and facilitate prompt transfer to the

definitive destination avoiding delay at the emergency.

Data collection

All reporting data forms were completed by

obstetricians and midwives and mailed to the Board of the CPC

Committee on a yearly basis. The Committee members transferred the

data to an electronic database for future statistical evaluation.

The database was subsequently double checked to confirm whether

patients had been reported by both sending and receiving hospitals.

Any disagreements were resolved by confirming the ambulance call

log books and the electronic patient database at NMU and NPGMC

hospitals. Furthermore, data were independently extracted from the

paramedic and coordinator's reports for all IFTs. The IFT data and

reason for transfer were collected from the administrative database

operated by the CPC Committee. To assess the quality of medical

practice in Nara Prefecture, maternal and perinatal mortality was

confirmed from data provided by National Statistics Center

(https://www.e-stat.go.jp/).

Statistical analysis

To assess the impact of the newly established IFT

system, the number and rate of IFTs and Out-of-Nara transportation

were compared among the three periods. Analyses were performed

using commercially available software packages (SPSS Statistics for

Windows version 17.0; IBM Corp. and Medcalc for Windows version

11.4.2.0; Medcalc) (Stata version 16.0, StataCorp LLC, TX). Values

of P<0.05 were deemed to indicate statistically significant

differences. Linear regression analysis was used for the comparison

of differences in each data between each year and the three

periods.

Results

Information regarding the annual

number of obstetric units, obstetrician-gynecologists and NICU and

GCU beds

During the study period, 129,482 deliveries were

recorded in our database. There were approximately 10,000

deliveries per year (a maximum of 11,659 in 2006 and a minimum of

9,626 in 2017). The number of deliveries significantly decreased by

17.4% between 2006 and 2017 (P<0.0001). The annual numbers of

obstetric units, obstetrician-gynecologists and NICU and GCU beds

are presented in Table II. The

number of obstetric units in Nara Prefecture did not change between

2006 and 2017. The number of obstetrician-gynecologists increased

annually (P=0.0132) and between the three periods (P<0.0001).

The number of NICU and GCU beds increased annually (P=0.0149).

| Table IIThe number of the patient transfers to

the EONC centers. |

Table II

The number of the patient transfers to

the EONC centers.

| | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | | |

|---|

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total | Significance |

|---|

| Population of Nara

Prefecture | 1,416,323 | 1,410,825 | 1,405,074 | 1,400,951 | 1,400,738 | 1,395,687 | 1,389,690 | 1,383,549 | 1,376,466 | 1,364,950 | 1,356,950 | 1,348,257 | 16,648,826 |

P<0.05a,b |

| Number of

deliveries | 11,659 | 11,456 | 11,224 | 10,898 | 11,164 | 10,995 | 11,021 | 10,752 | 10,257 | 10,414 | 10,016 | 9,626 | 129,482 |

P<0.05a,b |

| Number of IFTs | 192 | 185 | 204 | 224 | 225 | 275 | 283 | 284 | 265 | 292 | 301 | 290 | 3,020 |

P<0.05a,b |

|

Average on

Period (95% CI) | 188.5

(144.0-233.0) | 217.7

(188.2-247.1) | 284.3

(273.4-295.2) | | |

| Number of patients

transferred to facilities within Nara Prefecture | 148 | 143 | 158 | 193 | 216 | 254 | 25 | 263 | 251 | 278 | 272 | 283 | 2,717 |

P<0.05a,b |

|

The number

of patients transferred to NMU | 114 | 67 | 83 | 130 | 153 | 146 | 157 | 156 | 107 | 125 | 106 | 128 | 1,472 | n.s. |

|

Number of

patients transferred to NPGMC | 20 | 84 | 65 | 60 | 63 | 106 | 100 | 105 | 141 | 147 | 148 | 146 | 1,185 |

P<0.05a,b |

|

Number of

patients transferred to other facilities in Nara | 14 | 15 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 18 | 9 | 83 | n.s. |

| Number of

Out-of-Nara transfers | 44 | 42 | 46 | 31 | 9 | 21 | 25 | 21 | 14 | 14 | 29 | 7 | 155.4 |

P<0.05a |

|

Average on

Period (95% CI) | 43.0

(30.3-55.7) | 28.7

(-17.6-74.9) | 18.7

(11.8-25.6) | | |

| Out-of-Nara rate

(%) | 22.9 | 22.7 | 22.5 | 13.8 | 4.0 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 9.6 | 2.4 | 5.1 |

P<0.05a,b |

|

Average on

Period (95% CI) | 22.8

(21.5-24.2) | 13.5

(9.6-36.5) | 6.6 (4.2-8.9) | | |

| Number of obstetric

units (total) | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 37 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 35 | | n.s. |

|

Prefectural-level

hospitals | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | | |

|

General

hospitals | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | | |

|

Primary

clinics | 17 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 16 | | |

|

Midwifery

homes | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | | |

| Number of

obstetrician-gynecologists of four prefectural-level hospitals

(total) | 31 | 35 | 40 | 39 | 40 | 43 | 43 | 44 | 44 | 43 | 46 | 49 | |

P<0.05a,b |

|

Nara Medical

University (NMU) | 12 | 15 | 20 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 24 | 22 | 22 | 25 | 25 | | |

|

Nara

Prefecture General Medical Center (NPGMC) | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 12 | | |

|

Tenri

Hospital | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | | |

|

Kindai

University Nara Hospital | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 | | |

| Number of NICU and

GCU beds (total) | 34 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 39 | 63 | 78 | |

P<0.05a |

|

Nara Medical

University (NMU) | 15 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 45 | 45 | | |

|

Nara

Prefecture General Medical Center (NPGMC) | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 24 | | |

|

Kindai

University Nara Hospital | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | | |

| Number of maternal

deaths | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | n.s. |

|

Perinatal

mortality rate (per 1,000 births) | 6.2 | 4.2 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 5.1 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 4.7 | | |

|

Average on

Period (95% CI) | 5.2

(-7.5-17.9) | 4.7 (1.7-7.6) | 4.3 (3.6-5.0) | | |

| Incidence of

prolonged mechanical ventilation (%) | ND | 38.2 | 44.8 | 47.1 | 49.5 | 44.3 | 48.7 | 43 | 54.1 | 56.9 | 37.5 | 23 | | n.s. |

|

Average on

Period (95% CI) | 38.2 | 47.1

(41.3-53.0) | 43.9

(33.4-54.4) | | |

The annual number of IFTs from the

referring facilities to EONC centers

The CPC Committee databases (2006-2017) were used to

identify an annual trend analysis of the IFTs and Out-of-Nara

transfer. The number of deliveries significantly decreased by 17.4%

between 2006 and 2017 (P<0.0001). The number of the patient

transfers to the EONC centers is presented in Table II and Fig. 2. Among a total of 129,482

deliveries, 3,020 were transferred to the EONC centers (2.33%). Of

the 3,020 IFTs, 1,472 (48.7%) and 1,185 (39.2%) patients were

transferred to NMU and NPGMC, respectively. The annual IFT number

and rate increased from 192 (1.6%) per 11,659 deliveries in 2006 to

290 (3.0%) per 9,626 deliveries in 2017 (P<0.0001), resulting in

a 82.4% increase in the number of cases. The patients were divided

into three periods to assess the effects of these organizational

changes on IFTs. The number of IFTs significantly increased from

188.5 cases (95% CI, 144.0-233.0) per year in Period 1 to 217.7

cases (188.2-247.1) in Period 2 and 284.3 cases (273.4-295.2) in

Period 3 (P<0.0001).

Out-of-Nara transfer rates

There was a marked decrease in the incidence of the

Out-of-Nara transfer, ranging from 22.9% in 2006 to 2.4% in 2017

(10.0% per year on average, P=0.0057). The annual IFT rate of the

Out-of-Nara transfer decreased by 89.6% between 2006 (22.9%) and

2017 (2.4%, P=0.0011). The medical coverage of complicated

obstetric cases at the EONC centers was estimated to be 77.1%

(148/192) in 2006 and 97.6% (283/290) in 2017. A significant

decrease in the Out-of-Nara transfer rate was shown from 22.8% (95%

CI, 21.5-24.2) in Period 1 to 13.5% (9.6-36.5) in Period 2 and 6.6%

(4.2-8.9) in Period 3 (P=0.0065).

Top reasons for IFTs

The most common reasons for IFTs to the EONC centers

were preterm labor (36.7%), followed by premature rupture of

membranes (PROM) (20.0%), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP)

(8.7%), postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) (8.3%), placental abruption

(4.0%) (Table III).

| Table IIIMain reasons for patient transfer to

the EONC centers, Nara prefecture, Japan. |

Table III

Main reasons for patient transfer to

the EONC centers, Nara prefecture, Japan.

| Reasons for patient

transfer | n 3,043 | (%) (100) |

|---|

| Preterm labor | 1,118 | (36.7) |

| PROM | 609 | (20.0) |

| HDP | 265 | (8.7) |

| PPH | 254 | (8.3) |

| Placental

abruption | 123 | (4.0) |

| Placenta

previa | 89 | (2.9) |

| Non-reassuring

fetal status | 69 | (2.3) |

| FGR | 58 | (1.9) |

| HELLP syndrome | 51 | (1.7) |

| Pregnant women

without antenatal health care | 35 | (1.2) |

| Threatened

abortion | 23 | (0.8) |

| Others | 349 | (11.5) |

Maternal and perinatal mortality

In addition, we estimated the annual change in

incidence of maternal and perinatal outcomes before and after the

reorganization of the EONCs. We queried the CPC Committee registry

for the medical records of maternal death, perinatal mortality, and

adverse clinical outcomes, including NICU length of stay, the need

for inotropes and prolonged mechanical ventilation. It was found

that maternal death (P=0.926), perinatal mortality rate (P=0.947)

and adverse clinical outcomes (P=0.518) between 2006-2017 did not

change prior to and after the reorganization (Table II). Six maternal deaths were

registered in 2006 (n=2, postpartum hemorrhage and dilated

cardiomyopathy), 2012 (n=2, Group A streptococcal infection and

malignant lymphoma), and 2015 (n=2, brain stroke and aortic

dissection), respectively. Since maternal mortality was rare

throughout the period studied, no association was observed between

maternal mortality and vehicle-dispatch data. Furthermore, the

perinatal mortality rate exhibited no significant difference

between the periods studied [Period 1, 5.2 (95% CI, -7.5-17.9);

Period 2, 4.7 (1.7-7.6); and Period 3, 4.3 (3.6-5.0)]. We finally

investigated adverse clinical outcomes of the deliveries prior to

and after the reorganization. Both NICU length of stay and duration

of mechanical ventilation may be associated with a trend towards

neonatal mortality and morbidity. The duration of mechanical

ventilation, but not the NICU length of stay, was recorded in the

CPC committee database. The incidence of prolonged mechanical

ventilation was unchanged before and after the reorganization.

Discussion

In this study, a prefecture-based observational

study was conducted for a period of 12 years. This study assessed

the impact of the newly established IFT system and medical coverage

of complicated obstetric cases at two EONC centers. The timespan

was divided into three periods (before reorganization, one

reorganization and two reorganizations). The IFT rate significantly

increased from 1.7% (Period 1) to 2.4% (Period 2) and finally to

2.9% (Period 3) (P<0.0001). In contrast to these changes, the

Out-of-Nara transfer rate significantly declined from 22.7% (Period

1) to 7.8% (Period 2) and finally to 5.7% (Period 3) (P=0.0065).

The key findings of this study were as follows: i) The IFT rates

significantly increased over the study period; and ii) the

Out-of-Nara transfer rate markedly declined after the

reorganization of the EONC centers. The combination of the

reorganization of the EONC centers and the implementation of an

emergency referral network, including an efficient coordination

using telephone-based services by a transfer coordinator and an

effective communication, can facilitate the IFTs of women who

urgently require emergency obstetric care.

First, we highlight serious social and medical

issues related to emergency obstetric care and some of the

important factors to significantly reduce the number of the

Out-of-Nara transfer. Japan now faces serious medical issues,

including a shortage of physicians, an increase in the number of

females entering medicine and physician maldistribution between

medical departments (9). The

number of OB/GYN physicians, obstetricians and gynecologists, is

specifically decreasing. Furthermore, emerging evidence indicates

an increase in the incidence of obstetric complications in recent

years (2). The recent trend of

delayed parenthood and the associated use of assisted reproductive

technologies (ARTs) have led to the increased risk of obstetric

complications (4). There has been

an increase in the number of high-risk pregnant women who have

their first baby at an age >35 years. Other risk factors include

not only in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer

(IVF-ET), but also a pre-pregnancy BMI ≥30 kg/m2 or

<18 kg/m2, or a family history of hypertension or

diabetes (2).

The government has accelerated the selection and

concentration of obstetric facilities to cope with workforce

shortages and excessive workloads, including transfer or relocation

of services from one health care sector to EONC centers.

Policy-makers are facing acute shortages of obstetricians needed to

provide improved EONC services. Since 2007, the Japan Society of

Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) created actionable recommendations

to implement the innovative and community relevant interventions

called the ‘selection and concentration’ of obstetric facilities

(8-10).

This was a political issue, in which the reorganization of the EONC

center should be considered to reduce the increased workload of

obstetricians, increase job satisfaction and improve maternal and

neonatal outcomes. Considering the fact that health workforce

shortage and increasing complicated delivery in Japan, the

reorganization of EONC facilities could be a possible policy

option. Two EONC centers (NMU in 2008 and NPGMC in 2010) were newly

reorganized in Nara Prefecture and staffed by specialists. In

almost one decade, larger and multispecialty groups have been

reorganized through the selection, integrated arrangements and

concentration of obstetric facilities. The reorganization has

overcome accessibility of complicated obstetric cases and emergency

care for women with obstetric and neonatal disabilities in the

referring facilities. Therefore, both a resolution of a shortage of

obstetricians with increased workload and the increased number of

EONC beds may have a positive impact on the decreased Out-of-Nara

transfer rate.

Second, perinatal emergencies remain a challenging

burden on emergency department staff (11-14).

IFTs may be a useful option to ensure a higher level of care than

that which is available at the referring clinic or hospital. The

CPC Committee held a series of meetings to implement a plan for

coordinating the care of high-risk pregnancies with emergency

obstetric conditions. An obstetric emergency care coordinator can

quickly assess the limitations of each facility and acceptance, and

can properly determine ENOC center suitable for a patient's

condition, allowing information to be shared among obstetricians

and neonatologists. Our policy is that ensuring an uneventful IFT

will prepare prompt arrangement of transport for the patient and

reduce delays in access to the EONC centers. Neither pregnant women

nor their families denied to be transferred to the EONC centers.

During Period 3, IFTs were carried out by a transfer coordinator

through an agreement between the NMU hospital and the CPC Committee

under a relational contract with the government. A modest

investment in the transfer coordination may reduce the

obstetrician's burden. Task shifting by a transfer coordinator is a

potential strategy to improve access to the EONC centers and

actualize the smooth management of the IFT system. This clinical

innovation may involve a sustainable change in the clinical

practice of emergency medicine, particularly in countries now

facing serious medical issues, such as a shortage of

obstetricians.

Third, the most common cause for IFTs was preterm

labor (37.0%), followed by premature rupture of membranes (PROM)

(20.2%), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) (8.8%),

postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) (8.4%), placental abruption (4.0%).

Preterm delivery is considered to be the leading cause of neonatal

mortality and morbidity worldwide (3). Its prevention is an important

healthcare priority, but has been long-standing challenges. Since

neonatal outcomes are better for expectant mother transferred in

utero than those transferred ex utero (neonates), women

with pregnancy complications, including preterm birth, should be

transferred to the EONC centers as an in utero transfer

(15). In addition, we estimated

the annual change in incidence of the maternal death, perinatal

mortality rate and adverse clinical outcomes, including prolonged

mechanical ventilation, before and after the reorganization of the

EONCs. However, the timely response for emergency IFTs was not

associated with improved maternal-fetal outcomes. Due to the

increase in preterm delivery for maternal or fetal indications,

including preeclampsia or eclampsia, and intrauterine growth

restriction, premature infants may require longer positive pressure

ventilation.

Finally, we sought to identify other factors that

may have influenced the results of this study: For example, the

establishment of new hospitals inside Nara Prefecture,

transportation system changes (the spatiotemporal changes of new

expressway network), and changes in the criteria for

transportation. Nationwide, the number of obstetrics facilities

decreased during the study period. It is commonly believed that the

improvement of the expressway network exerts more widespread

influences on the emergency transportation. However, there were no

expressway infrastructure development plans in Nara Prefecture

throughout the study period. Furthermore, the IFT rate varies

according to the criteria for ambulance referrals to EONC centers

of women at risk of or with an obstetric complication. All of the

women who met these criteria in this study are shown in Table I. Therefore, it can be concluded

that the reorganization may be a primary factor of this change.

In conclusion, the findings of this study

demonstrate that i) progression of the selection, concentration and

intensification of obstetrics facilities may reduce the Out-of-Nara

transfer and acceptable referral coverage of complicated obstetric

cases; and that ii) transfer coordination by an IFT operator who

can quickly identify a transfer destination may provide an

effective doctor-to-doctor communication between referring

facilities and referred facilities.

In this study, we only analyzed the time trend data

based on the CPC Committee database and did not assess whether the

availability of the EONC centers is associated with an improved

outcome of severe obstetric complications, which may be a main

limitation of this study. Furthermore, this study did not evaluate

the quality of life and job satisfaction in obstetricians of

referring facilities and referred facilities. Koike et al

reported that the selection, concentration and intensification of

obstetrics facilities in fewer hospitals impairs patient access,

but EONC centers had a greater annual caseload and better staffing

than did those at non-specialized centers, which has the potential

advantages of better clinical outcomes (16). Further studies are required to

synthesize evidence regarding maternal and neonatal deaths, as well

as comprehensive outcome measurements, including an improvement of

quality of life of medical professionals.

In conclusion, the combination of reorganization of

two emergency obstetric and neonatal care (EONC) centers and

implementation of an efficient coordination by a transfer operator

is imperative for the successful management of interfacility

transfers (IFTs) in Nara Prefecture, Japan.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged members of the CPC

Committee, Nara Prefecture Government, including Toshiya Nishikubo

(Department of Neonatology, Nara Medical University), Tsunekazu

Kita (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nara Prefecture

General Medical Center Hospital), Hideki Minowa (Department of

Neonatology, Nara Prefecture General Medical Center Hospital),

Naoya Harada (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nara City

Hospital), Kiyoshi Fujiwara (Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, Tenri Hospital), Hidekazu Oi (Department of Obstetrics

and Gynecology, Kindai University Nara Hospital), Junji Tanji and

Takao Sanai (Nara Wide Area Fire Department) and Syuichiro Hayashi

(Welfare and Medical Department, Nara Prefectural Government). HK

and MA are members of the CPC Committee, Nara Prefecture

Government.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

TT, JA and KN collected data regarding the recent

trend of obstetric complications using the PubMed database. TS and

KN collected data regarding the number of the patient transfers to

the EONC centers and the Out-of-Nara transfer using the CPC

committee database and nation data in the vital statistics in

Japan. HK and MA contributed to the conception, design and

interpretation of this study. HK wrote the first draft of the

manuscript. The final version of the manuscript has been read and

approved by all authors.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the CPC Committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hasegawa J, Ikeda T, Sekizawa A, Tanaka H,

Nakamura M, Katsuragi S, Osato K, Tanaka K, Murakoshi T, Nakata M

and Ishiwata I: Maternal Death Exploratory Committee in Japan and

the Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists:

Recommendations for saving mothers' lives in Japan: Report from the

maternal death exploratory committee (2010-2014). J Obstet Gynaecol

Res. 42:1637–1643. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Muto H, Yamamoto R, Ishii K, Kakubari R,

Takaoka S, Mabuchi A and Mitsuda N: Risk assessment of hypertensive

disorders in pregnancy with maternal characteristics in early

gestation: A single-center cohort study. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol.

55:341–345. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wang ML, Dorer DJ, Fleming MP and Catlin

EA: Clinical outcomes of near-term infants. Pediatrics.

114:372–376. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Johnson B and Chavkin W: Policy efforts to

prevent ART-related preterm birth. Matern Child Health J.

11:219–225. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Nair M, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P,

Sellers S, Lewis G and Knight M: Factors associated with maternal

death from direct pregnancy complications: A UK national

case-control study. BJOG. 122:653–662. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hasegawa J, Sekizawa A, Tanaka H,

Katsuragi S, Osato K, Murakoshi T, Nakata M, Nakamura M, Yoshimatsu

J, Sadahiro T, et al: Current status of pregnancy-related maternal

mortality in Japan: A report from the maternal death exploratory

committee in Japan. BMJ Open. 6(e010304)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ide H, Yasunaga H, Kodama T, Koike S,

Taketani Y and Imamura T: The dynamics of obstetricians and

gynecologists in Japan: A retrospective cohort model using the

nationwide survey of physicians data. J Obstet Gynaecol Res.

35:761–766. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Japan Society of Obstetrics and

Gynecology: Grand design 2015 (GD2015) renovation of the obstetrics

and gynecology healthcare system in Japan. Japan Society of

Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tokyo, 2015. http://shusanki.org/index.html.

Accessed April 20, 2019.

|

|

9

|

Ishikawa T, Ohba H, Yokooka Y, Nakamura K

and Ogasawara K: Forecasting the absolute and relative shortage of

physicians in Japan using a system dynamics model approach. Hum

Resour Health. 11(41)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Matsumoto M, Koike S, Matsubara S, Kashima

S, Ide H and Yasunaga H: Selection and concentration of obstetric

facilities in Japan: Longitudinal study based on national census

data. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 41:919–925. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wiegers TA and de Borst J: Organisation of

emergency transfer in maternity care in the Netherlands. Midwifery.

29:973–980. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Eckstein M, Schlesinger SA and Sanko S:

Interfacility transports utilizing the 9-1-1 emergency medical

services system. Prehosp Emerg Care. 19:490–495. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, Van

den Boogaard W, Nyandwi G, Reid T, De Plecker E, Lambert V, Nicolai

M, Goetghebuer S, et al: An ambulance referral network improves

access to emergency obstetric and neonatal care in a district of

rural Burundi with high maternal mortality. Trop Med Int Health.

18:993–1001. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wu O, Briggs A, Kemp T, Gray A, MacIntyre

K, Rowley J and Willett K: Mobile phone use for contacting

emergency services in life-threatening circumstances. J Emerg Med.

42:291–298.e3. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chien LY, Whyte R, Aziz K, Thiessen P,

Matthew D and Lee SK: Canadian Neonatal Network: Improved outcome

of preterm infants when delivered in tertiary care centers. Obstet

Gynecol. 98:247–252. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Koike S, Matsumoto M, Ide H, Kashima S,

Atarashi H and Yasunaga H: The effect of concentrating obstetrics

services in fewer hospitals on patient access: A simulation. Int J

Health Geogr. 15(4)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|