Introduction

Almost two years have passed since the World Health

Organization (WHO) declared the severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak a global pandemic (1). The infection rate became markedly

stable and some authors, considering the interactions between

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and other non-communicable

diseases, refer to this situation as a ‘syndemic’ (2,3).

Up to January 31, 2022, >380 million cases of

SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported and over five million

individuals succumbed to the disease worldwide. To date, a total of

11 million cases have been reported in Italy, 147,000 of which have

not survived (4). It is now clear

that an uncontrolled systemic inflammation represents a critical

element in the progression of COVID-19 to acute respiratory

distress syndrome (ARDS) (5). This

non-specific and deleterious inflammatory response appears to lead

to alveolar damage due to inflammatory cell infiltration, pulmonary

edema and endothelial impairment along with microvascular

thrombosis, playing a key role in the development of severe

COVID-19 (6,7).

Of note, dexamethasone treatment has been shown to

be associated with improved outcomes in patients with severe

COVID-19(8). The IL-6 cascade has

already been proposed as a potential target for immunomodulatory

therapy to moderate systemic hyper-inflammation during SARS-CoV-2

infection (9,10).

Scientific literature and international guidelines

(11,12) suggest the use of tocilizumab, a

recombinant monoclonal antibody, in addition to standard of care

treatment, due to its ability to lower the risk of respiratory

deterioration, thus reducing the mortality rate. In the case that

tocilizumab is not available, sarilumab, a human monoclonal

antibody targeting IL-6 soluble receptors, which is already

approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, represents a

valid alternative for IL-6 blockade (13). Considering that IL-6 has multiple

pathways with varying effects, both positive and negative on

inflammation and homeostatic control, it is arduous for clinicians

to determine the correct therapeutic window for the administration

of anti-IL-6 drugs (13).

The present study describes cases of 4 patients with

severe pulmonary forms of COVID-19, requiring high-flow nasal

oxygenation along with dexamethasone administration, who were

successfully discharged following sarilumab administration.

Case report

Case 1

Upon admission to the ARNAS Garibaldi Hospital,

Catania, Italy, the patient was feverish (temperature, 38.5˚C),

blood pressure (BP) was 125/60 mmHg, heart rate (HR) was 62 bpm,

and oxygen saturation was 91% in room air. He was administered

O2 therapy with a Venturi mask (VM) at 12 l/min

(fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2, 60%). Blood tests

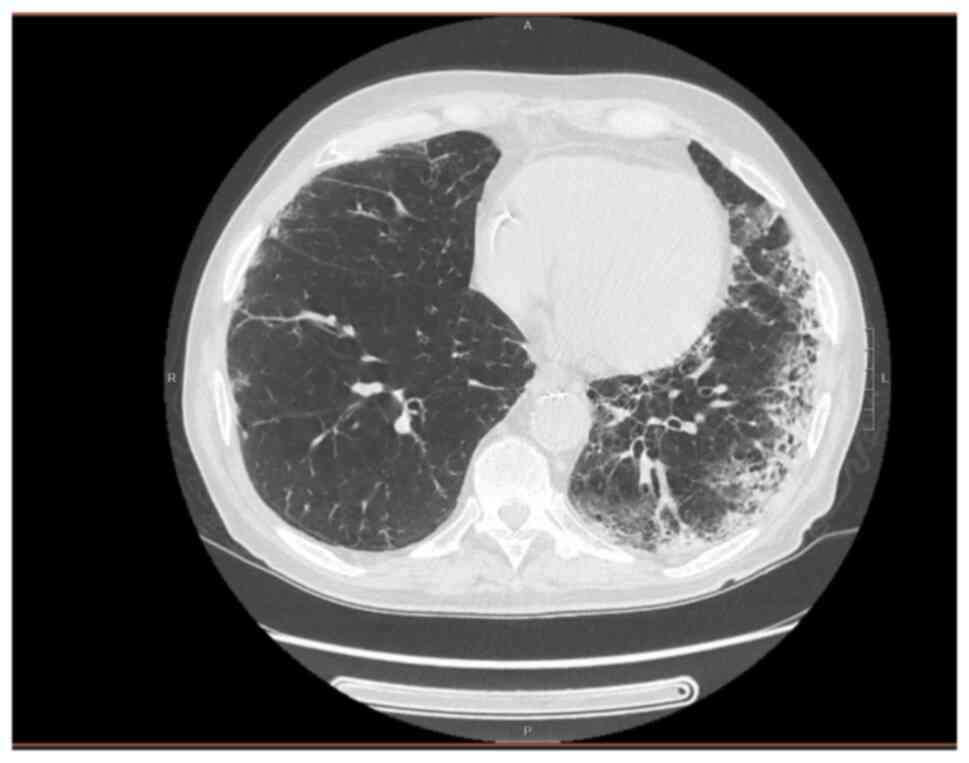

revealed elevated inflammatory marker levels (Table I) and a thoracic CT scan revealed

bilateral interstitial pneumonia (Fig.

1). Treatment with prophylactic enoxaparin, dexamethasone and

piperacillin/tazobactam was commenced.

| Table IDemographics, clinical

characteristics at the time of admission, treatment and outcomes of

the 4 patients with COVID-19. |

Table I

Demographics, clinical

characteristics at the time of admission, treatment and outcomes of

the 4 patients with COVID-19.

|

Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 |

|---|

| Age, years | 75 | 73 | 84 | 73 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

(no. of doses) | No | Yes (2 doses of

BNT162b2) | No | No |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension,

coronary disease with previous percutaneous revascularization. | Atrial

fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, COPD | Hypertension | Hypertension, GERD,

major depressive disorder |

| Home therapy | Clopidogrel,

bisoprolol, ramipril, amlodipine, cardioaspirin, omeprazole | Methimazole,

insulin, pantoprazole, amlodipine, propranolol, apixaban | None | Candesartan,

alprazolam, pantoprazole |

| Days between

admission and HFNC treatment initiation | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Chest CT

findings | Bilateral

honeycombing pattern, fibrotic reticulation, and

consolidations | Bilateral

interstitial pneumonia along with consolidations and bilateral

pleural effusion | Bilateral

interstitial pneumonia along with vast consolidations | Bilateral

interstitial pneumonia, and consolidations within

bronchiectasis |

| Days between the

onset of symptoms and hospital admission | 15 | 7 | 12 | 7 |

| Laboratory finding;

unit (reference range) | | | | |

|

WBC,

cells/mmc (4,000-10,000) | 7,100 | 6,000 | 12,900 | 8,400 |

|

Neutrophils,

% (40-75) | 80.5 | 63.8 | 86 | 83.8 |

|

Lymphocytes,

% (25-50) | 10.7 | 26.2 | 9.9 | 10.6 |

|

Monocytes, %

(2-10) | 8.6 | 8.8 | 3.9 | 5.5 |

|

Platelets,

cells/mmc x103 (150-400) | 230 | 85 | 321 | 172 |

|

Hzemoglobin,

g/dl (12-16) | 13.3 | 13 | 13.6 | 13.9 |

|

AST, UI/l

(15-35) | 29 | 45 | 40 | 73 |

|

ALT, UI/l

(15-35) | 24 | 16 | 27 | 107 |

|

LDH, UI/l

(80-250) | 362 | 411 | 430 | 526 |

|

Creatinine,

mg/dl (0.8-1.2) | 1.28 | 0.84 | 0.6 | 0.57 |

|

CRP, mg/dl

(0-0.5) | 9.95 | 12.34 | 10.04 | 12.99 |

|

ESR, mm/h

(0-10) | 54 | 29 | 56 | 66 |

|

D-dimer,

ng/ml (<250) | 2,013 | 883 | 680 | 18,847 |

|

Ferritin,

ng/ml (20-200) | 814 | 522 | 796 | 1,118 |

|

Lowest

PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 103 | 98 | 94 | 93 |

| Antibiotic therapy

(duration) |

Piperacillin/tazobactam (12 days),

levofloxacin (7 days) |

Piperacillin/tazobactam (12 days) |

Piperacillin/tazobactam (10 days)

levofloxacin (7 days) |

Piperacillin/tazobactam (11 days) |

| Others therapies

(duration) | Enoxaparin 6,000 UI

s.c. (18 days), dexamethasone 6 mg i.v. (18 days) | Dexamethasone 6 mg

i.v. (22 days) | Enoxaparin 6,000 UI

s.c. (28 days), dexamethasone 6 mg i.v. (26 days) | Enoxaparin 6,000 UI

s.c. (18 days), dexamethasone 6 mg i.v. (16 days) |

| Days on HFNC | 8 | 9 | 11 | 9 |

| Sarilumab dose

(number of doses) | 400 mg i.v. (single

dose) | 400 mg i.v. (single

dose) | 400 mg i.v. (single

dose) | 400 mg i.v. (single

dose) |

| Days from admission

to sarilumab | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Time to hospital

discharge (days) | 18 | 24 | 28 | 18 |

On the 4th day, due to the worsening of oxygen

saturation, an arterial blood analysis was performed, revealing

partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) levels of 62.3 mmHg,

partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) levels of 30.2

mmHg, pH 7.39 and a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of

103.

Oxygen ventilation with a high flow nasal cannula

(HFNC; Optiflow™ Nasal High Flow Therapy delivered by AIRVO™ 2;

Fisher & Paykel Healthcare), 60 l/min, FiO2 60% was

administered, and on the same day, the patient was administered a

single dose of sarilumab at 400 mg intravenously. Furthermore,

levofloxacin 500 mg/day was empirically added to extend the

antibiotic coverage.

Within 24 h from sarilumab administration, his

clinical condition ameliorated, and arterial blood analysis

improved (PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 140). The levels

of serum inflammatory markers decreased [C-reactive protein (CRP)

levels, 0.44 mg/dl]. HFNC ventilation was continued for a further 7

days (8 days overall), and the patient was gradually weaned off of

O2 therapy following a further 5 days.

Case 2

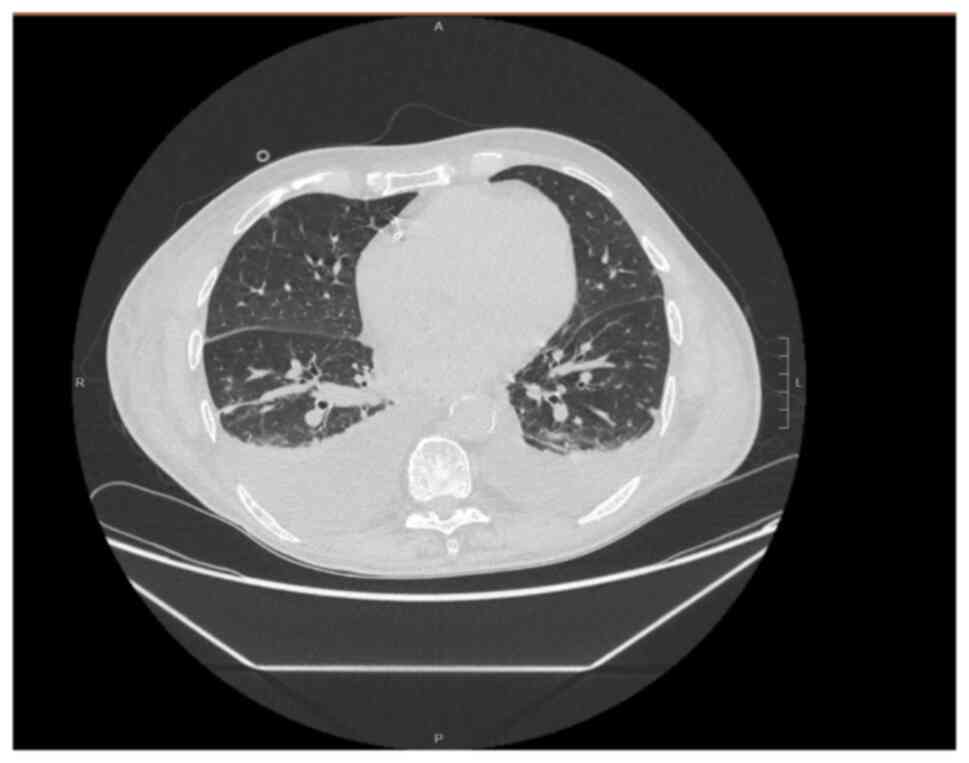

Upon admission (to the same hospital as mentioned

above), the patient was afebrile, BP was 135/60 mmHg, HR was 110

bpm, and oxygen saturation was 96% with a nasal cannula (NC)

3l/min. Blood tests revealed high inflammatory marker levels

(Table I). A thoracic CT scan

revealed bilateral interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 2). Treatment with dexamethasone and

piperacillin/tazobactam was commenced.

Despite pharmacologic treatment and O2

supplementation, his respiratory functions continued to

deteriorate. Blood gas analysis with the VM at 12 l/min,

Fi02 60%, revealed PaO2 at 59 mmHg,

PCO2 at 39 mmHg, pH 7.47 and a

PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 98. HFNC ventilation (60

l/min, FiO2 60%) was commenced on the 4th day from

admission, and sarilumab at 400 mg intravenously was administered

within 24 h.

Within 48 h from the sarilumab administration, his

clinical condition, laboratory tests (CRP levels 1.32 mg/dl), and

blood gas analysis (PaO2/FiO2, 121) improved. HFNC

treatment was steadily reduced; this was switched to a VM at 9 days

following HFNC initiation, and the patient was also gradually

weaned off this as well.

Case 3

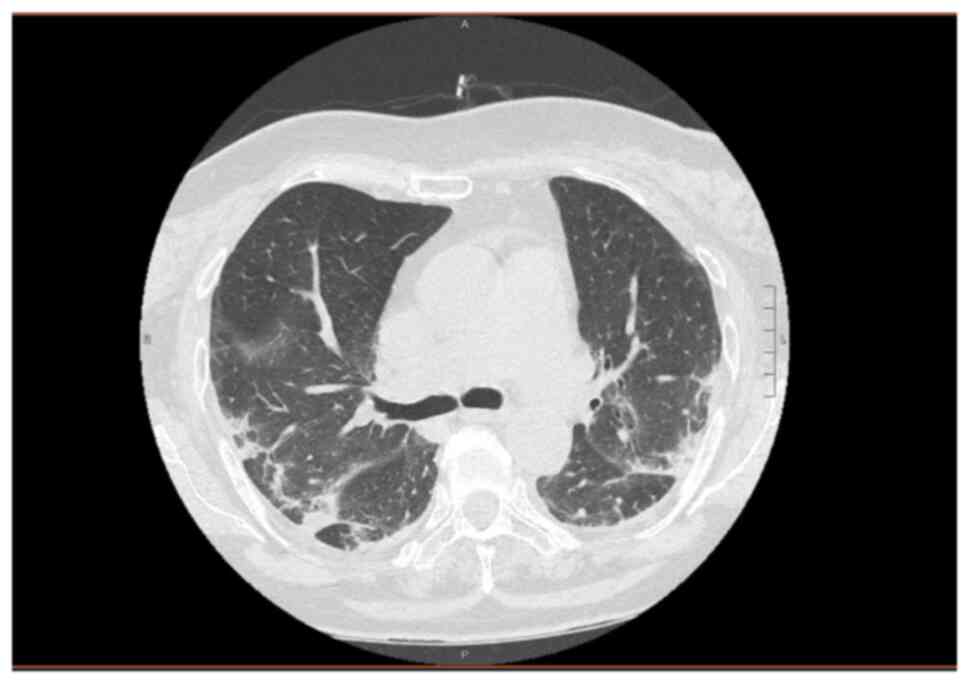

Upon admission (to the same hospital as mentioned

above), the patient was feverish (temperature, 39.5˚C), BP was

150/75 mmHg, HR was 100 bpm, the oxygen saturation rate was 95%

with a VM at 8 l/min and a FiO2 of 35%. Blood tests

revealed elevated inflammatory marker levels along with

neutrophilic leukocytosis (Table

I). A chest CT scan revealed bilateral interstitial pneumonia

(Fig. 3). Enoxaparin 6,000 U/day,

dexamethasone 6 mg/day and piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g/three

times/day were administered.

On the 3rd day, arterial blood analysis revealed a

PaO2 of 49 mmHg, PCO2 of 28.5 mmHg, pH 7.45

and a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 139. HFNC was

commenced at 60 l/min, and a FiO2 of 60% was arranged.

The following day, sarilumab was administered intravenously at a

single dose of 400 mg.

Within 48 h, arterial blood analysis revealed

progressive amelioration in the patient's condition

(PaO2/FiO2 was 122). Although serum

inflammatory marker levels began to decrease (CRP levels, 0.29

mg/dl), blood tests revealed leukopenia with neutropenia, reaching

a nadir 9 days following sarilumab infusion (2,000/mmc, 12.1%

neutrophils). Neutropenia resolved within 7 days without treatment.

HFNC ventilation was terminated within 11 days. Subsequently, a VM

was used for a further 5 days, and this was gradually reduced over

this period of time.

Case 4

Upon admission (to the same hospital as mentioned

above), the patient was feverish (temperature, 39.5˚C), BP was

145/55 mmHg, HR was 100 bpm, oxygen saturation was 97% with a VM at

6 l/min and FiO2 of 31%. Blood tests revealed high

inflammatory marker levels along with high D-dimer levels and

hypertransaminasemia (Table I). A

chest CT scan revealed bilateral interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 4). The patient was commenced on

treatment with enoxaparin 6,000 U/day, dexamethasone 6 mg/day and

piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g/three times/day.

Since arterial blood analysis revealed

PaO2 of 57 mmHg, PCO2 of 31 mmHg, pH 7.5, and

a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 93, along with the

deterioration of chest imaging, HFNC (60 l/min; FiO2

60%) was commenced. Sarilumab was administered intravenously at 400

mg within 24 h after the initiation of HFNC.

Within 48 h, the patient's respiratory performances

and blood arterial analysis began to improve

(PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 136). Inflammatory

marker levels also began to decrease. However, 7 days following the

administration of sarilumab the patient's laboratory tests revealed

leukopenia with neutropenia (2,700/mmc, 18.9% neutrophils).

Neutropenia resolved within 7 days without treatment.

HFNC treatment was gradually reduced and switched to

VM first and then NC, until hospital discharge.

Discussion

To date, SARS-CoV-2 infection pathophysiology

remains mostly unclear, arguably as it is not attributable only to

the virus; in fact, both immune and inflammatory responses appear

to play a key role in disease development and duration,

particularly as regards its severe form.

In order to avoid disease progression, intervention

can take place during the first phase of infection (viral phase)

with certain antiviral drugs (remdesivir, molnupiravir,

nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) or monoclonal antibodies (sotrovimab),

administering these within the correct time lapse. However, the

second phase (inflammatory phase) is more severe, and thus it is

difficult to treat due to its severity, complexity and lack of

standardized treatments (14).

It has been reported that COVID-19 causes cytokine

release syndrome (CRS), leading to a dysregulated immune response,

culminating in ARDS, which is also determined by the up- and

downregulation of the expression of several genes directly

stimulated by SARS-CoV-2 infection (15).

CRS is considered an immune system overreaction

response developing in an unregulated manner, the same pathogenetic

mechanism which underlines autoimmune and hematological diseases

(16,17). As confirmation, drugs to treat this

phase are also administered against autoimmune disorders (16).

Various proinflammatory cytokines have been

investigated as the cause of CRS and, among these, IL-6 is one of

the most extensively studied due to its crucial role in

inflammatory pathways. IL-6 has been studied as both an

inflammatory/prognostic marker, since its levels are associated

with the inflammatory state and a therapeutic target (13). Monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-6

and IL-6 receptors are recommended by Italian and American

guidelines for the treatment of patients with severe and critical

COVID-19(14).

Sarilumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG1

subtype), specifically binds both soluble and membrane-attached

IL-6 receptors (IL6-Rα); it inhibits IL6-mediated pathways

involving glycoprotein 130 (gp130) along with STAT-3. Sarilumab has

been investigated in a few studies, the results of which are not

conclusive (13). Della-Torre

et al (18) reported data

from 28 patients with COVID-19 treated with a single dose of

sarilumab intravenously, and demonstrated a decrease in recovery

time; however, no statistically significant differences in terms of

mortality and overall improvement between patients treated with

standard of care were reported.

Gremese et al (19) studied 53 patients treated with

sarilumab, almost all of which received a second infusion; 14 of

these patients were from the intensive care unit (ICU) and

exhibited an improvement in clinical conditions along with a

reduction in oxygen supplementation therapy; in addition, more than

half of the ICU patients exhibited clinical amelioration following

sarilumab administration. Although on a smaller sample size,

similar results were demonstrated in the study by Benucci et

al (20) on 8 patients treated

with sarilumab.

To date, only a few randomized controlled trials

(13) have been published on

sarilumab administration in patients with COVID-19 and no specific

meta-analyses have been performed to date, at least to the best of

our knowledge. In the study performed by the REMAP-CAP

collaborative group (21), 48

patients were assigned to one dose of 400 mg sarilumab intravenous

administration; the results revealed that sarilumab improved

in-hospital survival compared with usual care.

A larger study, performed by Lescure et al

(12) on 420 subjects, did not

demonstrate the efficacy of sarilumab as regards the outcomes and

survival rates of patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 and

receiving supplemental oxygen, despite an improved recovery

time.

The CORIMUNO19 group performed an open-label,

randomized, controlled trial with 148 patients randomly assigned to

sarilumab or standard of care, with half of the patients in the

sarilumab group treated with a second dose (22). That trial did not highlight any

effect of sarilumab in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 in

terms of mortality rate nor on the decreasing proportion of

patients requiring non-invasive ventilation.

The cases reported in the present study developed

severe pulmonary disease due to SARS-CoV2 between 10 and 15 days

from infection, probably due to an excessive proinflammatory

response. All the patients described herein had multiple risk

factors for severe COVID-19 (an age >70 years, multiple

comorbidities and polypharmacy). The results of CT scans revealed

the presence of bilateral interstitial lung involvement and

arterial blood examination displayed gradual respiratory parameters

deterioration.

Among the patients in the present study, only one

had received two doses of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Each patient

received oxygen administration through HFNC, achieving a better

peripheral saturation along with blood gas analysis amelioration

(23,24). Furthermore, a single dose of

sarilumab was intravenously administered to each patient, in

accordance with Italian guidelines (AIFA) and IDSA guidelines

(11,14).

Prior to the sarilumab administration, all the

patients in the present study were screened for latent or active

infections such as hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus

and hepatitis B virus (25-31).

Within 48-72 h following anti-IL-6 treatment, the patients'

respiratory conditions began to improve, along with improved blood

gas examination and clinical parameters. CRP levels at a cut-off

value of 75 mg/l were used as a surrogate marker of systemic

inflammation to guide the sarilumab administration and to assess

the patients' conditions.

Antibiotic therapy was selected based on local

bacterial epidemiology, the patients' previous antibiotic

treatments and the thoracic CT scan results (31-34).

Furthermore, standard of care therapy (enoxaparin and

dexamethasone) was administered upon admission, following Italian

guidelines.

Dexamethasone administration has been found to be

highly variable across studies on sarilumab therapy, in contrast to

trials on tocilizumab administration, in which the anti-IL-6 drug

has been almost always administered together with corticosteroids.

This difference may explain the diverse results between tocilizumab

and sarilumab in favor of the former drug in previous studies;

however, these data need to be clarified in larger-scale trials

(35).

As regards the scientific literature on the adverse

reactions associated with the use of sarilumab, although with some

limitations (the absence of a control group, single-center setting,

concomitant treatments), Gremese et al (19) did not register severe adverse

events or any secondary infections related to treatment with

sarilumab. In the study by Lescure et al (12), the occurrence of adverse events of

varying severity was similar between both the treatment and the

placebo group.

No severe adverse events were reported in the

REMAP-CAP study (21), and the

CORIMUNO19 group (22) reported a

few cases of temporary neutropenia that is a common side-effect of

all IL-6 blockers. In the same study, a non-statistically

significant increase in the number of bacterial infections was

reported in the sarilumab group (12 patients) compared to the

control group (7 patients).

In the present study, 2 of the patients described

developed neutropenia following the sarilumab administration, which

resolved within a few days without sequelae. Although it is

limited, the authors' experience with sarilumab administration is

in accordance with the findings in the literature as regards the

percentage of recovery, time to oxygen weaning, safety of sarilumab

and time to discharge (12-15).

In August 2020, the authors published the results of

a small case series on tocilizumab administration in patients on

HFNC (23); that study yielded

promising results that have since then been confirmed by larger

trials (35); larger randomized

controlled trials together with meta-analyses are required to

determine the specific effects of sarilumab administration in

patients with COVID-19 and to determine whether other contemporary

therapies, such as dexamethasone, may lead to improvements in

outcomes.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

sarilumab is a safe drug with good clinical outcomes in patients

with COVID-19 and, hence, may be an alternative regimen for the

treatment of patients with SARS-CoV2 severe pulmonary involvement.

Further prospective and well-designed clinical studies with larger

sample sizes and long-term follow up are warranted to assess the

efficacy and the safety of this therapeutic approach to achieve

improved outcomes of patients with COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Pietro Leanza,

Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of

Catania, Catania, Italy, for his kind English revision of the

manuscript.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no

datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors' contributions

All authors (AMa, EC, MC, LL, CB, CM, AMu, BMC, GN

and BC) contributed to the study conception and design. AM wrote

the manuscript. EC, MC, CB, CM revised the literature and searched

for relevant references. LL and MC provided clinical assistance to

the patients. AMu was responsible for the laboratory tests and

pharmacological treatments. BMC, GN and BC revised the manuscript.

GN and BC confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual

participants included in the present case report study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all the

patients for publication of the present care report study and

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song

J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, et al: A novel coronavirus from

patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl J Med. 382:727–733.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Horton R: Offline: COVID-19 is not a

pandemic. Lancet. 396(935)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Musumeci G: Effects of COVID-19 Syndemic

on Sport Community. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 7(19)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ministero della Salute. Covid-19,

situation in Italy. https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?area=nuovoCoronavirus&id=5367&lingua=english&menu=vuoto.

Accessed February 24, 2022.

|

|

5

|

Osuchowski MF, Winkler MS, Skirecki T,

Cajander S, Shankar-Hari M, Lachmann G, Monneret G, Venet F, Bauer

M, Brunkhorst FM, et al: The COVID-19 puzzle: Deciphering

pathophysiology and phenotypes of a new disease entity. Lancet

Respir Med. 9:622–642. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Grasselli G, Tonetti T, Protti A, Langer

T, Girardis M, Bellani G, Laffey J, Carrafiello G, Carsana L,

Rizzuto C, et al: Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute

respiratory distress syndrome: A multicentre prospective

observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 8:1201–1208.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim

WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, Staplin N,

Brightling C, Ustianowski A, et al: Dexamethasone in Hospitalized

patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 384:693–704. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Nissen CB, Sciascia S, de Andrade D,

Atsumi T, Bruce IN, Cron RQ, Hendricks O, Roccatello D, Stach K,

Trunfio M, et al: The role of antirheumatics in patients with

COVID-19. Lancet Rheumatol. 3:e447–e459. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Angriman F, Ferreyro BL, Burry L, Fan E,

Ferguson ND, Husain S, Keshavjee SH, Lupia E, Munshi L, Renzi S, et

al: Interleukin-6 receptor blockade in patients with COVID-19:

Placing clinical trials into context. Lancet Respir Med. 9:655–664.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Bhimraj A, Morgan R, Shumaker A, Lavergne

V, Baden L, Cheng VC-C, Edwards KM, Gandhi R, Gallagher J, Muller

WJ, et al: IDSA Guidelines on the treatment and management of

patients with COVID-19. Published by IDSA on 4/11/2020. Last

updated, 3/23/2022. Available: https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management/.

|

|

11

|

Bassetti M, Giacobbe DR, Bruzzi P,

Barisione E, Centanni S, Castaldo N, Corcione S, De Rosa FG, Di

Marco F, Gori A, et al: Clinical management of adult patients with

COVID-19 outside intensive care units: Guidelines from the Italian

society of anti-infective therapy (SITA) and the Italian Society of

Pulmonology (SIP). Infect Dis Ther. 10:1837–1885. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lescure FX, Honda H, Fowler RA, Lazar JS,

Shi G, Wung P, Patel N and Hagino O: Sarilumab COVID-19 Global

Study Group. Sarilumab in patients admitted to hospital with severe

or critical COVID-19: A randomised, double-blind,

placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 9:522–532.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zizzo G, Tamburello A, Castelnovo L, Laria

A, Mumoli N, Faggioli PM, Stefani I and Mazzone A: Immunotherapy of

COVID-19: Inside and beyond IL-6 signalling. Front Immunol.

13(795315)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH,

Lavergne V, Baden L, Cheng VC, Edwards KM, Gandhi R, Gallagher J,

Muller WJ, et al: Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines

on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Clin

Infect Dis: Apr 27, 2020 (Epub ahead of print). doi:

10.1093/cid/ciaa478.

|

|

15

|

Nunnari G, Sanfilippo C, Castrogiovanni P,

Imbesi R, Li Volti G, Barbagallo I, Musumeci G and Di Rosa M:

Network perturbation analysis in human bronchial epithelial cells

following SARS-CoV2 infection. Exp Cell Res.

395(112204)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Que Y, Hu C, Wan K, Hu P, Wang R, Luo J,

Li T, Ping R, Hu Q, Sun Y, et al: Cytokine release syndrome in

COVID-19: A major mechanism of morbidity and mortality. Int Rev

Immunol. 41:217–230. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cosentino F, Moscatt V, Marino A,

Pampaloni A, Scuderi D, Ceccarelli M, Benanti F, Gussio M, Larocca

L, Boscia V, et al: Clinical characteristics and predictors of

death among hospitalized patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in

Sicily, Italy: A retrospective observational study. Biomed Rep.

16(34)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Della-Torre E, Campochiaro C, Cavalli G,

De Luca G, Napolitano A, La Marca S, Boffini N, Da Prat V, Di

Terlizzi G, Lanzillotta M, et al: Interleukin-6 blockade with

sarilumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia with systemic

hyperinflammation: An open-label cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis.

79:1277–1285. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Gremese E, Cingolani A, Bosello SL,

Alivernini S, Tolusso B, Perniola S, Landi F, Pompili M, Murri R,

Santoliquido A, et al: Sarilumab use in severe SARS-CoV-2

pneumonia. EClinicalMedicine. 27(100553)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Benucci M, Giannasi G, Cecchini P, Gobbi

FL, Damiani A, Grossi V, Infantino M and Manfredi M: COVID-19

pneumonia treated with Sarilumab: A clinical series of eight

patients. J Med Virol. 92:2368–2370. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

REMAP-CAP Investigators. Gordon AC,

Mouncey PR, Al-Beidh F, Rowan KM, Nichol AD, Arabi YM, Annane D,

Beane A, van Bentum-Puijk W, et al: Interleukin-6 receptor

antagonists in Critically Ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med.

384:1491–1502. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

CORIMUNO-19 Collaborative group. Sarilumab

in adults hospitalised with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 pneumonia

(CORIMUNO-SARI-1): An open-label randomised controlled trial.

Lancet Rheumatol. 4:e24–e32. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Marino A, Pampaloni A, Scuderi D,

Cosentino F, Moscatt V, Ceccarelli M, Gussio M, Celesia BM, Bruno

R, Borraccino S, et al: High-flow nasal cannula oxygenation and

tocilizumab administration in patients critically ill with

COVID-19: A report of three cases and a literature review. World

Acad Sci J. 2(1)2020.

|

|

24

|

Ceccarelli M, Marino A, Cosentino F,

Moscatt V, Celesia BM, Gussio M, Bruno R, Rullo EV, Nunnari G and

Cacopardo BS: Post-infectious ST elevation myocardial infarction

following a COVID-19 infection: A case report. Biomed Rep.

16(10)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Marino A, Cosentino F, Ceccarelli M,

Moscatt V, Pampaloni A, Scuderi D, D'Andrea F, Rullo EV, Nunnari G,

Benanti F, et al: Entecavir resistance in a patient with

treatment-naïve HBV: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol.

14(113)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Celesia BM, Marino A, Borracino S,

Arcadipane AF, Pantò G, Gussio M, Coniglio S, Pennisi A, Cacopardo

B and Panarello G: Successful extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

treatment in an acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patient

with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) complicating

pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia: A challenging case. Am J Case

Rep. 21(e919570)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Celesia BM, Marino A, Del Vecchio RF,

Bruno R, Palermo F, Gussio M, Nunnari G and Cacopardo B: Is it safe

and cost saving to defer the CD4+ cell count monitoring

in stable patients on ART with more than 350 or 500 cells/µl?

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 11(e2019063)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Marino A, Zafarana G, Ceccarelli M,

Cosentino F, Moscatt V, Bruno G, Bruno R, Benanti F, Cacopardo B

and Celesia BM: Immunological and clinical impact of DAA-mediated

HCV eradication in a cohort of HIV/HCV Coinfected patients:

Monocentric Italian experience. Diagnostics.

11(2336)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Micali C, Russotto Y, Caci G, Ceccarelli

M, Marino A, Celesia BM, Pellicanò GF, Nunnari G and Venanzi Rullo

E: Loco-regional treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma in people

living with HIV. Infect Dis Rep. 14:43–55. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Marino A, Scuderi D, Locatelli ME, Gentile

A, Pampaloni A, Cosentino F, Ceccarelli M, Celesia BM, Benanti F,

Nunnari G, et al: Modification of serum brain-derived neurotrophic

factor levels following anti-HCV therapy with direct antiviral

agents: A new marker of neurocognitive disorders. Hepat Mon.

20(e95101)2020.

|

|

31

|

Burgaletto C, Brunetti O, Munafò A,

Bernardini R, Silvestris N, Cantarella G and Argentiero A: Lights

and shadows on managing immune checkpoint inhibitors in oncology

during the COVID-19 Era. Cancers. 13(1906)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Marino A, Munafò A, Zagami A, Ceccarelli

M, Di Mauro R, Cantarella G, Bernardini R, Nunnari G and Cacopardo

B: Ampicillin plus ceftriaxone regimen against Enterococcus

faecalis endocarditis: A literature review. J Clin Med.

10(4594)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Erdem H, Hargreaves S, Ankarali H,

Caskurlu H, Ceviker SA, Bahar-Kacmaz A, Meric-Koc M, Altindis M,

Yildiz-Kirazaldi Y, Kizilates F, et al: Managing adult patients

with infectious diseases in emergency departments: International

ID-IRI study. J Chemother. 33:302–318. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

El-Sokkary R, Uysal S, Erdem H, Kullar R,

Pekok AU, Amer F, Grgić S, Carevic B, El-Kholy A, Liskova A, et al:

Profiles of multidrug-resistant organisms among patients with

bacteremia in intensive care units: An international ID-IRI survey.

Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 40:2323–2334. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Tocilizumab

in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A

randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet.

397:1637–1645. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|