Introduction

Delirium is an acute confusional state, also defined

as acute brain failure or dysfunction. The pathophysiological

mechanism behind delirium is not yet well understood. It is

frequently observed in elderly individuals and in hospital settings

(1,2).

Delirium is provoked by the transient disruption of

regular neuronal activity and is associated with a slower recovery,

increased mortality and morbidity, and a decreased quality of life

(3).

According to the criteria of Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5)

(4), the diagnosis of delirium

requires a disturbance in attention, which develops acutely, is not

explained by pre-existing dementia, and does not occur in the

context of a reduced level of arousal, with one additional

disturbance in cognition and evidence of an underlying organic

disorder. Patients may experience hallucinations and manifest

abnormal psychomotor behavior and a sleep-wake cycle (4).

Delirium can be described as hyperactive, hypoactive

or a combination of both. Hyperactive delirium includes

restlessness (for example, pacing), agitation, rapid mood changes

or hallucinations and is more easily recognizable, while

hypoactive, which includes a reduced motor activity, sluggishness

and abnormal drowsiness, can pass unrecognized, despite being the

most frequent among elderly patients, who usually manifest it with

lethargy and a general slowness (5).

Delirium occurs in 85% of cases in palliative care

settings, in up to 25% of patients post-surgery and in 50% of

patients following major surgery (6). Beyond an older age and long-term

hospitalization, other risk factors associated with the development

of delirium are the male sex, underlying undiagnosed dementia,

alcohol abuse, impairment in vision and/or hearing and depression

(6,7).

Previous studies have suggested cerebral

desaturation as a risk factor for the development of delirium

(8-10),

and it has been observed that the frequency of delirium is

increased in intensive care units (ICUs) (11).

The appearance of severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) abruptly led to a pandemic, particularly

due to its transmission mode (12)

and the onset of numerous variants (13,14).

This rapidly led to an increase in the number of hospitalizations.

The respiratory syndrome consequent to coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) (15), similar to the

one caused by the first SARS-CoV, led to a sudden need in oxygen

therapy, ventilation and admission to ICUs.

A number of complications, such as electrolytic

impairment or macular rash, have been linked to SARS-CoV-2

infection (16-22).

Neurological and psychiatric complications due to COVID-19 have

also been described, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder or motor

dysfunction (23,24). Researchers have already proven an

increase in the number of episodes of delirium during the COVID-19

pandemic, mostly related to ICU admissions, long-term

hospitalization and hypoxemia (25). Other aspects that have been found

to be associated with an increased risk of developing delirium are

the use of benzodiazepines, opioids, vasopressors, fever, smoking,

a history of cardiovascular diseases, dialysis and thromboembolic

illnesses (26). In some cases,

the very same strategies and treatments for COVID-19, such as the

use of the prone position can contribute to the development of

delirium (27). Another important

issue that has come to light with the COVID-19 pandemic is the

isolation of positive patients, who have been unable to visit or

come into contact with their families during the hospitalization

period. All these factors have contributed to the development of

delirium, particularly considering the more frail members of the

population, such as the elderly (28-40).

Even though it is certainly more frequent among

elderly patients, delirium concomitant to SARS-CoV-2 has been also

observed in younger age groups (41) and even in pediatric cases (42-44).

Moreover, it has been observed in some specific categories of

patients who are considered to be more frail, such as pregnant

women and immunocompromised individuals; thus, this should be

considered in the concept of delirium (45-47).

In some cases, it has been indicated that delirium may be the

primary and sometimes, the only presenting symptom of COVID-19

(48-51).

Since the first cases of COVID-19, different

manifestations of neuropathology secondary to the infection, such

as anosmia and ageusia have been observed. There are a number of

hypotheses regarding the pathophysiology of delirium in COVID-19,

including the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to directly invade the central

nervous system via the olfactory bulb, and it has been suggested

that it may preferentially target the frontal lobes (52), or indirectly via the oxidative

stress caused by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines

(53,54) microvascular damage (55), metabolic and/or endocrine

dysfunctions and organ insufficiency (56,57).

In the study by Cuperlovic-Cul et al

(58), a difference was noted in

polyamines in patients with delirium and an association between the

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and monoamine oxidase was postulated.

Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the development of delirium

is a result of both environmental and organic factors (59).

The study by Batra et al (60) demonstrated that persistent viral

shedding in patients was associated with in-hospital delirium

episodes and a higher mortality rate. Notably, in the study by Dias

et al (61), delirium was

not found to have a higher prevalence in the COVID-19 group

compared with the non-COVID-19, while it appeared to manifest in a

more severe form in the COVID-19 group.

Delirium has been shown to be associated with a

higher mortality rate in patients hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2

infection (62-66),

prolongation in hospital stay (67), an impairment in physical functions

(68) and cognitive impairment

even after physical recovery from infection (69).

Despite being so widely diffused, delirium remains a

challenging diagnosis and it is of utmost importance to develop

tools to help physicians recognize this condition. A consistent

barrier in recognizing delirium is the underlying dementia,

particularly considering that the patients with a major risk of

developing delirium are the elderly, who may already have cognitive

impairment. This poses the difficulty of a juxtaposition of both

neurocognitive impairment and it usually leads to a misdiagnosis or

the non-recognition of delirium. Two valid instruments for the

diagnosis of delirium are the Confusion Assessment Method-ICU

(CAM-ICU) and the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist

(ICDSC), both developed for delirium screening in non-verbal

patients in ICUs (70). Another

tool with a high sensitivity and moderate specificity is the 4AT

score (71).

A critical aspect of the neuropsychiatric

consequences due to COVID-19 is the issue of the ‘forgotten ones’,

namely all the individuals dismissed from hospital following

recovery from COVID-19. It is known that SARS-COV-2 infection may

lead to long-term alterations, which have been commonly defined as

‘long covid’ (72). Even though it

often manifests with mild symptoms, in some cases, severe

complications may occur post-COVID-19, as in the case described in

the study by Hara et al (73); in that study, a patient developed

post-COVID-19 encephalitis presenting with delirium as a first

manifestation. Unrelated to the hospitalization, yet still an

important consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, is the effect of

the lockdowns on elderly individuals, who are more susceptible to

developing delirium in response to the amount of stress and

anxiety, brought on by the feelings of isolation (74).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the

psychiatric risks related to hospitalization and to acute viral

infections, such as COVID-19. It is of utmost importance to take

into account the possibilities of developing delirium, particularly

in elderly patients. An acute episode could not only lead to

adverse consequences for health workers and the patients

themselves, as in the case of the hyperactive form, but can also

compromise the prognosis and the rehabilitation of hospitalized

individuals.

Case report

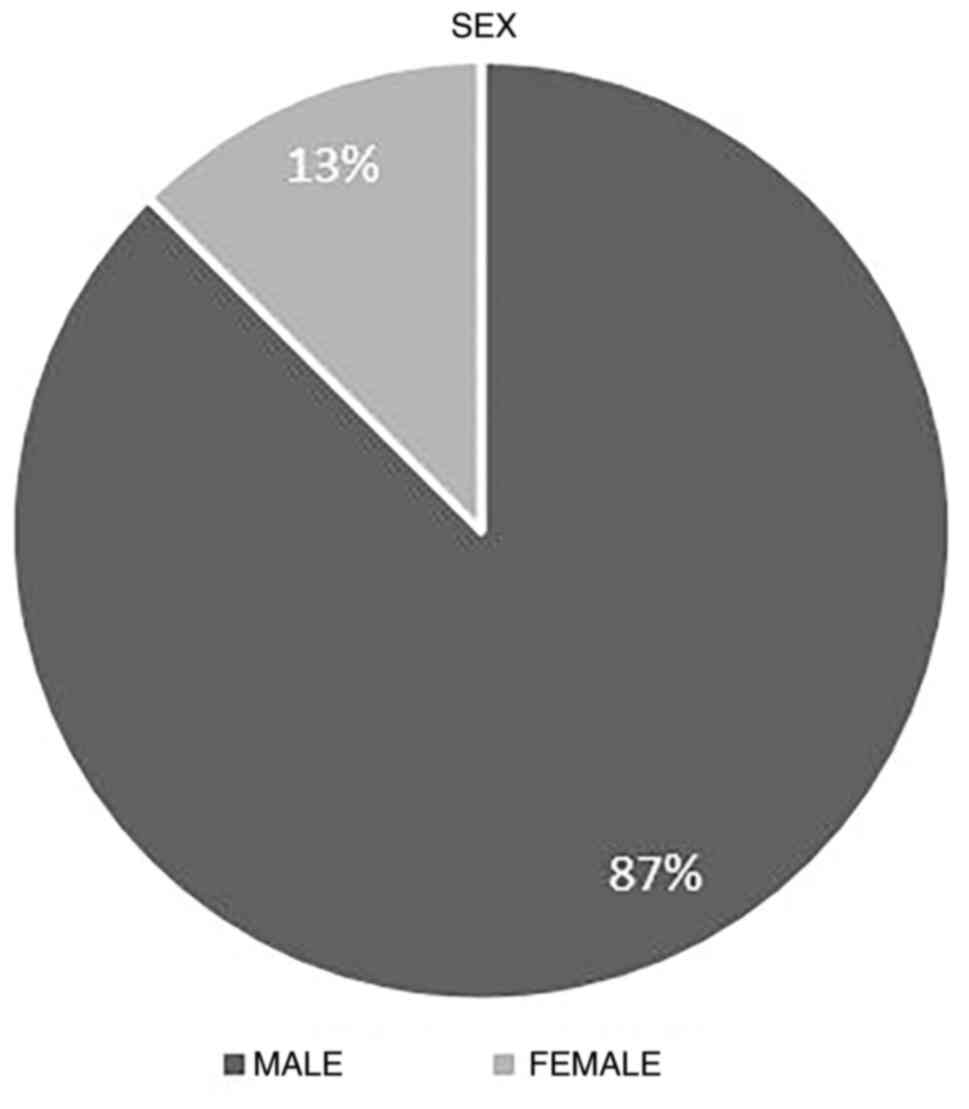

Between March, 2020 and May, 2022, in the Infectious

Diseases Unit of the ‘Gaetano Martino’ University Hospital in

Messina, 8 patients hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 infection presented

delirium. The male sex was the most prevalent one, with a 7:1 ratio

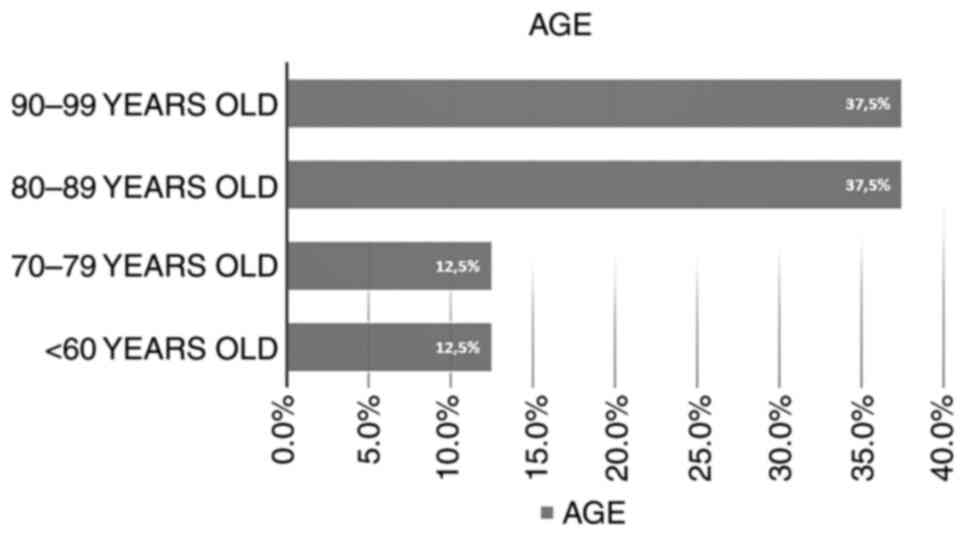

(Fig. 1). The mean age of the

patients was 81.7±4 years (Fig.

2). The characteristics of the 8 patients are presented in

Table I. In total, 5 patients

(cases 2, 3, 4, 5 and 8) presented the feature of mild age-related

dementia.

| Table ICharacteristics of the 8 patients in

the present study. |

Table I

Characteristics of the 8 patients in

the present study.

| Case no. | Age, years | Sex | Comorbidities | SARS-CoV-2

vaccination | Hospitalization

days | Need for

O2 DH | COVID-19

therapy | Days between

admission and delirium | Outcome |

|---|

| 1 | 80 | M | | No | 25 | Yes |

Casirivimab/imdevimab | 2 | CR |

| 2 | 90 | M | DM, CV diseases;

COPD | No | 30 | Yes | | 14 | VR |

| 3 | 90 | M | | No | 12 | No | | 36 | CR |

| 4 | 86 | M | DM, CV diseases;

COPD | Yes | 15 | Yes | | 1 | Deceased |

| 5 | 87 | M | DM, CV disease,

psychosis | Yes | 56 | Yes | | 38 | Deceased |

| 6 | 58 | M | PD | No | 16 | No | Azithromycin,

hydroxychloroquine | 8 | VR |

| 7 | 70 | F | Cancer | No | 22 | Yes | | 2 | VR |

| 8 | 93 | M | | No | 13 | Yes | | 9 | CR |

A total of 2 patients had at least two shots of the

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, while 6 patients were not vaccinated. In

addition, 2 patients had a history of type II diabetes,

cardiovascular diseases and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

1 patient had type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease, 1

patient had a history of cancer, and 1 patient had Parkinson's

disease. Only 1 patient had a psychiatric comorbidity prior to

hospitalization, as he was diagnosed with an unspecified psychosis

and received chronic therapy with lorazepam, promazine and

tiapride.

In total, 6 patients out of the 8 patients required

oxygen implementation, 2 patients did not need it and were

maintained in room air, and no patient required mechanical

ventilation. The mean duration of hospitalization was 23.6±6 days,

with the longest time being 56 days and the shortest time being 12

days (Table I).

As regards COVID-19 therapy, low molecular weight

heparin (LMWH) was administered to all patients. In addition, 1

patient was treated with azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine for

thromboembolic prophylaxis, and 1 patient received monoclonal

antibody therapy with casirivimab/imdevimab (Table I).

In total, 6 patients (cases 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 and 8)

received corticosteroids for respiratory impairment, 4 patients (1,

2, 4 and 7) received dexamethasone and 2 (5 and 8) patients

received methylprednisolone. These patients were also treated with

omeprazole for the duration of the corticosteroid therapy. Insulin

therapy was administered to 3 patients who were diabetic.

Moreover, 5 patients (cases 1, 2, 3, 7 and 8) were

treated with antibiotics for infections which occurred during

hospitalization; the antibiotics used were meropenem, cefepime,

amoxicillin/clavulanate and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The

chronic therapies administered are listed in Table II.

| Table IIChronic therapies used in the

patients. |

Table II

Chronic therapies used in the

patients.

| Medication | Patients (case

nos.) |

|---|

| Cardioaspirin | 6 (2, 3, 4, 6, 7

and 8) |

| Atorvastatin | 5 (2, 4, 5, 6 and

8) |

| Bisoprolol | 4 (1, 4, 5 and

8) |

| Nebivolol | 4 (1, 2, 4 and

7) |

| Furosemide | 4 (1, 4, 5 and

6) |

| Fondaparinux | 2 (2 and 4) |

| Canrenone | 2 (6 and 7) |

|

Lorazepam/delorazepam/clonazepam | 2 (5 and 8) |

| Finasteride | 1(7) |

| Nifedipine | 1(7) |

| Allopurinol | 1(1) |

| Pramipexole | 1(5) |

| Safinamide | 1(5) |

| Vortioxetine | 1(5) |

| Pregabalin | 1(1) |

| Promazine | 1(8) |

| Tiapride | 1(7) |

During hospitalization blood analyses were performed

routinely. In total, 2 patients (cases 4 and 5) exhibited

alterations in glycaemia (251 and 337 mg/dl) upon admission and

maintained a slightly altered level of hematic glucose during the

whole period of hospitalization. Furthermore, patient 1 exhibited

an abnormal renal function, with creatinine levels of 2,8 mg/dl and

azotemia levels of 123 mg/dl upon admission, which improved during

hospitalization. In another case (case 8), a worsening of renal

function was observed during hospitalization. An increase in

procalcitonin levels (max 10 ng/ml) was observed in cases 1, 2, 3,

7 and 8, who developed infection during hospitalization. C reactive

protein levels were found to be altered in 6 patients (cases 1, 2,

3, 4, 7 and 8), with a minimum level of 1,50 mg/dl and a maximum

level of 10,5 mg/dl. Of note, in case 6, a decrease in hemoglobin

(8,9 g/dl) levels was observed in the blood analyses performed the

day after the delirium episode. No significant alterations were

found in the levels of other laboratory markers performed during

hospitalization, such as transaminases, cholestasis indices,

coagulation factors and a urine analysis.

In total, 4 patients (cases 2, 3, 6 and 7) were

discharged with a negative nasopharyngeal swab (RT-PCR) for

SARS-CoV-2: the mean time of viral shedding was 26.5±2 days, with

the longest time being 35 days and the shortest time being 18 days.

The mean number of days between the admission and the occurrence of

delirium was 13.7±3, with the longest being 38 days, and the

shortest being 1 day.

A delirium episode began with an abrupt

manifestation of aggressiveness and violence: The patients, who

were previously compliant, suddenly removed vascular accesses,

oxygen masks and exhibited verbal aggressiveness, thus insulting

health workers; 7 patients (cases 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8) used

vulgar language, which had never been used by them before, as also

confirmed by the families of the patients. In 3 cases (1, 3 and 5),

the patients destroyed the room furniture and every other object

they could reach. In all the cases, delirium manifested with a

strong refusal to receive medical examination, or therapies and

food. A total of 3 patients (cases 3, 6 and 7) experienced

hallucinations referring to the presence of other individuals in

the room and objects that were not effectively present, and 2

patients (3 and 7) also referred to hearing voices of other

individuals. In addition, 1 patient (case 8) manifested self-harm

and started beating and scratching himself and patient 5 presented

persecutory delusions and suicidal ideation.

In all cases, delirium presented as hyperactive.

Although, it should be mentioned that 1 patient (case 6) manifested

a general slowness and became unresponsive immediately following a

hyperactive delirium episode.

According to standard clinical practice,

non-pharmacological interventions, such as verbal reassurance and

orientation, were used at first. When it was deemed safe for health

workers to intervene, as a first line pharmacologic treatment and

according to psychiatric consultation, intramuscular tiapride (100

mg) was administered alone in 3 cases (patients 1, 3 and 4) and in

association with haloperidol (1 mg) in case 7, promazine (25 mg)

was administered alone in case 8, in association with valproate

sodium at 300 mg in case 5 and with aripiprazole in another case

(patient 2), and in case 6, aripiprazole alone was administered at

increasing doses.

A complete resolution of delirium with no other

recurrences was obtained in 3 cases (patients 3, 4 and 6). In 5

cases (1, 2, 5, 7 and 8), the patients had a recurrence of

delirium. As second-line therapy, valproate sodium, promazine and

tiapride were administered. In addition, 2 patients out of the 8

patients had a clinical recovery and were discharged to a COVID-19

low intensity cure facility, 4 patients had a virological recovery

and 2 patients did not survive.

Discussion

With a mean age of 81.7±4 years and a huge

prevalence of the male sex, the cases described in the present

study appear to follow the evidence in the literature, which report

a greater risk of developing delirium in males and among the

elderly, a well as among patients hospitalized for COVID-19

(75-79).

Even though individuals with pre-existing

psychiatric disorders appear to have a major risk of developing

delirium (80), among the patients

described herein, 1 patient had a history of psychiatric disorders.

Age-related dementia was present in the majority of patients in the

present study. Thus, it is considered that dementia and other types

of neurocognitive age-related impairment are precipitating factors

for delirium (6).

In the patients described in the present study,

COVID-19 was the dominant cause capable of triggering delirium,

since the other conditions either alone, or in combination, would

probably have not been sufficient to cause this; i.e., in a

population of patients of the same age and comorbidities, the

prevalence of delirium would have been significantly lower.

Moreover, the presence of comorbidities found during

viral infections can facilitate the onset of an acute confusional

state (28,81,82).

In a previous Chinese case study (83), the prevalence of some comorbidities

was hypertension (16.9%), other cardiovascular diseases (53.7%)

cerebrovascular diseases (1.9%), diabetes (8.2%), hepatitis B

infections (1.8%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (1.5%),

chronic kidney diseases (1.3%), tumors (11.1%) and immunodeficiency

(0.2%). Those individuals who require ICU-level care, are the ones

who can easily develop delirium.

The majority of the patients in the present study

required oxygen supplementation, in some cases limited to a

low-flow nasal cannula; however, in some cases, oxygenation had to

be implemented at a high flow due to severe desaturation. This may

support the hypothesis that cerebral desaturation may trigger

delirium and that the need for oxygen supplementation is also

related to delirium (8-10,25).

Considering the therapies administered for COVID-19,

all the patients described herein were treated with LMWH for

thromboembolic prophylaxis. In the study by D'Ardes et al

(84), a protective role of LMWH

in the development of delirium was suggested. Notably, in the

present study, it did not play a protective role in preventing

delirium.

Other than drugs, the time of hospitalization has

been one of the main factors associated with the development of

delirium in hospital settings. As aforementioned, long-term

hospitalization is strongly associated with the development of

delirium (6,7); however, in the present study, it is

interesting to observe that the median time passed between

admission and the episode of delirium was 13 days, and in in 3

cases, delirium occurred after 1 or 2 days after admission. This

suggests that, while long-term hospitalization plays a critical

role, pre-existing features may lead to the onset of delirium,

despite the time in hospital.

There does not appear to be a prevalence of

hyperactive vs. hypoactive delirium, although it also appears that

there is a higher frequency of hypoactive delirium in the elderly

population. Nevertheless, both forms were observed in hospital

settings during the COVID-19 pandemic (85,86).

Of note, all the patients described herein manifested a hyperactive

form of delirium, exhibiting verbal and physical aggressiveness

towards the health workers. Verbal and physical aggressiveness

towards health workers can be considered, in psychopathological

terms, a form of hetero-aggressiveness or heterodirect

aggressiveness, which is a feature of hyperactive delirium, that is

characterized itself by an aggressive behavior, according to DSM-5

(87-90).

However, it is possible that some cases of hypoactive delirium have

passed undiagnosed and have been resolved without the use of

medications.

The treatment for delirium is controversial,

particularly considering that some primary medications may be

contraindicated due to the concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection, with

particular attention to the antivirals, even though no notable

interactions have been reported (91). Specifically, haloperidol,

risperidone and quetiapine may expose the patients to certain

adverse effects of antivirals, due to their increased concentration

(71). Given the high distress of

patients admitted to hospital and in a enforced isolation,

behavioral therapy should be the first-line treatment for the

prevention of delirium. As regards pharmacological therapy, the

Italian Society of Psychiatry suggested a number of therapeutic

options for delirium during COVID-19(92), as presented in Table III.

| Table IIITreatment recommendations for

delirium during the COVID-19 pandemic, as recommended by the

Italian Society of Psychiatry. |

Table III

Treatment recommendations for

delirium during the COVID-19 pandemic, as recommended by the

Italian Society of Psychiatry.

| Delirium therapy in

COVID-19 |

| Dexmetodimin (for

patients in the ICU): Alpha-2 agonist, sedative

anxiolytic-analgesic that does not cause respiratory

depression |

| Tiapride: Useful if

the patient is agitated (hyperkinetic delirium) and receiving

therapy with lopinavir/ritonavir. |

| Promazine via

intramuscular (if not contraindicated for coagulation

problems) |

| Aripiprazole:

Useful for hypokinetic delirium |

| Haloperidol: Low

risk of respiratory depression |

| Avoid

benzodiazepines unless delirium tremens is suspected |

The treatment options suggested in previous studies

include melatonin, in order to regulate the wake-sleep cycle,

valproic acid or trazodone and dopamine agonist (93). In a letter by Khosravi (94), quetiapine was proposed as a safe

therapy for delirium in the ICU.

The management of psychiatric drugs, their possible

interactions with COVID-19 therapeutics and the concomitant

necessity for psychological treatment are the main issues in

treating delirium, particularly in ICU settings (95-97).

Thus, the assessment and treatment of delirium in hospitalized

patients with COVID-19 requires a multidisciplinary effort and

collaboration (98).

The drugs most frequently used in the cases

described herein were promazine, haloperidol and tiapride. It is

noteworthy to observe that only 3 patients had a complete

resolution of delirium, while the majority experienced a

recurrence, despite therapies. The recurrence of delirium may be

caused by the environmental factors that still pose a huge font of

distress to hospitalized individuals, including isolation, the lack

of communication, the limitations in motility and the treatments

for underlying illnesses and COVID-19 itself. Therefore, the

implementation of the quality of life, as a multidisciplinary

effort, of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 is necessary to

achieve a resolution or, at least, avoid the repercussions of

delirium (98).

In the cases described in the present study, the

mortality rate was 25%, which is a critical indicator of how

delirium can play a role in the mortality of hospitalized patients,

as demonstrated by other studies (62-66).

It is imperative to create protocols and take action

in order to prevent delirium. While some aspects are not

modifiable, such as patient comorbidities or visiting restrictions,

an improvement could be made regarding the wake-sleep cycle of the

patients, considering the use of melatonin in treatment. The food

intake also is a critical variable and a more balanced diet may

play a positive role during the hospital stay of patients. The

psychological aspect is probably the most crucial one; engaging the

patients in conversations or implementing the use of psychologists

and/or the digital system to maintain communications with families

while in COVID-19 wards may improve the quality of life and the

mental status of hospitalized patients (99-101).

In conclusion, in this period when SARS-CoV-2 has

imposed enforced isolation, hospitalization and the need for

oxygen, it is of primary importance to develop tools to diagnose

delirium more effectively, including the less evident forms, and to

take measures to improve the environmental factors that may

contribute to delirium, with particular attention to behavioral

therapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Aldo Sitibondo,

of the Unit of Infectious Diseases, University of Messina, Messina,

Italy, for providing a critical clinical point of view on the

manuscript.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

YR, EVR, CM, GN, VC and CPS conceptualized the

study. YR, CM and VC were involved in the writing of the original

draft and in manuscript preparation. EVR, CM, VC and GN were

involved in the writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

VC was involved in visualization/impagination. GN supervised the

study. YR and GN confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent has been obtained from the

patients described in the present case report. In the 2 cases which

were then deceased, written consent was obtained from the patients

prior to their death.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent has been obtained from the

patients for the publication of their data. In the 2 cases which

were then deceased, written consent was obtained from the patients

prior to their death.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Mattison MLP: Delirium. Ann Intern Med.

173:ITC49–ITC64. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hshieh TT, Inouye SK and Oh ES: Delirium

in the Elderly. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 41:1–17. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Maldonado JR: Acute brain failure:

Pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, and sequelae of delirium.

Crit Care Clin. 33:461–519. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

American Psychiatric Association:

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edition.

American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, 2013.

|

|

5

|

Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T,

Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, Inouye SK, Bernard GR and Dittus RS:

Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated

patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 291:1753–1762.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Marcantonio ER: Delirium in hospitalized

older adults. N Engl J Med. 377:1456–1466. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Cipriani G, Danti S, Nuti A, Carlesi C,

Lucetti C and Di Fiorino M: A complication of coronavirus disease

2019: Delirium. Acta Neurol Belg. 120:927–932. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Susano MJ, Dias M, Seixas FS, Vide S,

Grasfield R, Abelha FJ, Crosby G, Culley DJ and Amorim P:

Association among preoperative cognitive performance, regional

cerebral oxygen saturation, and postoperative delirium in older

portuguese patients. Anesth Analg. 132:846–855. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Xue FS, Liu SH and Hou HJ: Association

between postoperative delirium and cerebral oxygen desaturation in

older patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Comment on Br J Anaesth

2020; 124: 146-53. Br J Anaesth. 127:e98–e99. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Eertmans W, De Deyne C, Genbrugge C,

Marcus B, Bouneb S, Beran M, Fret T, Gutermann H, Boer W, Vander

Laenen M, et al: Association between postoperative delirium and

postoperative cerebral oxygen desaturation in older patients after

cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 124:146–153. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Stollings JL, Kotfis K, Chanques G, Pun

BT, Pandharipande PP and Ely EW: Delirium in critical illness:

Clinical manifestations, outcomes, and management. Intensive Care

Med. 47:1089–1103. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Vella F, Senia P, Ceccarelli M, Vitale E,

Maltezou H, Taibi R, Lleshi A, Venanzi Rullo E, Pellicanò GF,

Rapisarda V, et al: Transmission mode associated with coronavirus

disease 2019: A review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 24:7889–7904.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lai A, Bergna A, Menzo S, Zehender G,

Caucci S, Ghisetti V, Rizzo F, Maggi F, Cerutti F, Giurato G, et

al: Circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants in Italy, October 2020-March

2021. Virol J. 18(168)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lai A, Bergna A, Caucci S, Clementi N,

Vicenti I, Dragoni F, Cattelan AM, Menzo S, Pan A, Callegaro A, et

al: Molecular tracing of SARS-CoV-2 in Italy in the first three

months of the epidemic. Viruses. 12(798)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ceccarelli M, Berretta M, Venanzi Rullo E,

Nunnari G and Cacopardo B: Differences and similarities between

severe acute respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-CoronaVirus (CoV) and

SARS-CoV-2. Would a rose by another name smell as sweet? Eur Rev

Med Pharmacol Sci. 24:2781–2783. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Meduri A, Oliverio GW, Mancuso G,

Giuffrida A, Guarneri C, Venanzi Rullo E, Nunnari G and Aragona P:

Ocular surface manifestation of COVID-19 and tear film analysis.

Sci Rep. 10(20178)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Guarneri C, Rullo EV, Pavone P, Berretta

M, Ceccarelli M, Natale A and Nunnari G: Silent COVID-19: What your

skin can reveal. Lancet Infect Dis. 21:24–25. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Pirisi M, Rigamonti C, D'Alfonso S,

Nebuloni M, Fanni D, Gerosa C, Orrù G, Venanzi Rullo E, Pavone P,

Faa G, et al: Liver infection and COVID-19: the electron microscopy

proof and revision of the literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

25:2146–2151. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Guarneri C, Venanzi Rullo E, Gallizzi R,

Ceccarelli M, Cannavò SP and Nunnari G: Diversity of clinical

appearance of cutaneous manifestations in the course of COVID-19. J

Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 34:e449–e450. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ceccarelli M, Marino A, Cosentino F,

Moscatt V, Celesia BM, Gussio M, Bruno R, Rullo EV, Nunnari G and

Cacopardo BS: Post-infectious ST elevation myocardial infarction

following a COVID-19 infection: A case report. Biomed Rep.

16(10)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Longhitano E, Nardi C, Calabrese V,

Messina R, Mazzeo G, Venanzi Rullo E, Ceccarelli M, Chatrenet A,

Saulnier P, Torreggiani M, et al: Hypernatraemia and low eGFR at

hospitalization in COVID-19 patients: A deadly combination. Clin

Kidney J. 14:2227–2233. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Calabrese V, Micali C, Russotto Y, Laganà

N, Gullotta C, Pisano A, Santoro D, Nunnari G and Venanzi Rullo E:

Arteriovenous fistula thrombosis in hemodialysis patients with

COVID-19: Epiphenomenon or marker of severe clinical disease? G

Ital Nefrol. 39:2022–vol3. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Pavone P, Ceccarelli M, Marino S, Caruso

D, Falsaperla R, Berretta M, Rullo EV and Nunnari G: SARS-CoV-2

related paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric Syndrome. Lancet

Child Adolesc Health. 5:e19–e21. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Buccafusca M, Micali C, Autunno M, Versace

AG, Nunnari G and Musumeci O: Favourable course in a cohort of

Parkinson's disease patients infected by SARS-CoV-2: A

single-centre experience. Neurol Sci. 42:811–816. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kotfis K, Williams Roberson S, Wilson JE,

Dabrowski W, Pun BT and Ely EW: COVID-19: ICU delirium management

during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Crit Care. 24(176)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Santos CJ, Nuradin N, Joplin C, Leigh AE,

Burke RV, Rome R, McCall J and Raines AM: Risk factors for delirium

among SARS-CoV-2 positive veterans. Psychiatry Res.

309(114375)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Woolley B: The COVID-19 conundrum: Where

both the virus and treatment contribute to delirium. Geriatr Nurs.

42:955–958. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Pun BT, Badenes R, Heras La Calle G, Orun

OM, Chen W, Raman R, Simpson BK, Wilson-Linville S, Hinojal

Olmedillo B, Vallejo de la Cueva A, et al: Prevalence and risk

factors for delirium in critically ill patients with COVID-19

(COVID-D): A multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med.

9:239–250. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak TA,

McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P, Zandi MS, Lewis G and David AS:

Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with

severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and

meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet

Psychiatry. 7:611–627. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Garcez FB, Aliberti MJR, Poco PCE,

Hiratsuka M, Takahashi SF, Coelho VA, Salotto DB, Moreira MLV,

Jacob-Filho W and Avelino-Silva TJ: Delirium and adverse outcomes

in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc.

68:2440–2446. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Schenck M,

Severac F, Clere-Jehl R, Studer A, Radosavljevic M, Kummerlen C,

Monnier A, et al: Delirium and encephalopathy in severe COVID-19: A

cohort analysis of ICU patients. Crit Care. 24(491)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Skipper AW and Zanetos J: The importance

of delirium before and after COVID-19. J Gerontol Nurs. 47:3–5.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

de Sousa Moreira JL, Barbosa SMB, Vieira

JG, Chaves NCB, Felix EBG, Feitosa PWG, da Cruz IS, da Silva CGL

and Neto MLR: The psychiatric and neuropsychiatric repercussions

associated with severe infections of COVID-19 and other

coronaviruses. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.

106(110159)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Kennedy M, Helfand BKI, Gou RY, Gartaganis

SL, Webb M, Moccia JM, Bruursema SN, Dokic B, McCulloch B, Ring H,

et al: Delirium in older patients with COVID-19 presenting to the

emergency department. JAMA Netw Open. 3(e2029540)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Forget MF, Del Degan S, Leblanc J, Tannous

R, Desjardins M, Durand M, Vu TTM, Nguyen QD and Desmarais P:

Delirium and inflammation in older adults hospitalized for

COVID-19: A cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 16:1223–1230.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

M AS, E DP and Jl AM: Delirium in

hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A case series. Psychiatry Res.

305(114245)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

García-Grimshaw M, Chiquete E,

Jiménez-Ruiz A, Vidal-Mayo JJ, Grajeda-González SL, Vargas-Martínez

MLÁ, Toapanta-Yanchapaxi LN, Valdés-Ferrer SI, Chávez-Martínez OA,

Marché-Fernández OA, et al: Delirium and associated factors in a

cohort of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J

Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 63:3–13. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Turan Ş, Poyraz BÇ, Aksoy Poyraz C,

Demirel ÖF, Tanrıöver Aydın E, Uçar Bostan B, Demirel Ö and Ali RK:

Characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 inpatients who underwent

psychiatric consultations. Asian J Psychiatr.

57(102563)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Watne LO, Tonby K, Holten AR, Olasveengen

TM, Romundstad LG and Neerland BE: Delirium is common in patients

hospitalized with COVID-19. Intern Emerg Med. 16:1997–2000.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Maeker É and Maeker-Poquet B: Delirium, a

possible typical presentation of COVID-19 in the elderly. Soins

Gerontol. 26:10–15. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In French).

|

|

41

|

Haddad PM, Alabdulla M, Latoo J and Iqbal

Y: Delirious mania in a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia. BMJ Case

Rep. 14(e243816)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Bauer SC, Moral F, Preloger E, Spindler A,

Roman M, Logan A, Sandage SJ, Manak C and Mitchell M: Pediatric

COVID-19 delirium: Case report of 2 adolescents. WMJ. 120:131–136.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Castro REV, Rodríguez-Rubio M,

Magalhães-Barbosa MC and Prata-Barbosa A: Pediatric delirium in

times of COVID-19. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 33:483–486.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In English,

Portuguese).

|

|

44

|

Gasnier M, Choucha W, Radiguer F, Bougarel

A, Faulet T, Kondarjian C, Thorey P, Baldacci A, Ballerini M, Ait

Tayeb AEK, et al: Acute objective severity of COVID-19 Infection

and psychiatric disorders 4 months after hospitalization for

COVID-19. J Clin Psychiatry. 83(21br14179)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Di Giacomo E, Colmegna F, Santorelli M,

Pessina R, D'Amico E, Marcatili M, Dakanalis A, Pavone F, Fagiolini

A and Clerici M: Delirium in the ‘young’ covid-19 patient (<65

years): Preliminary clinical indications. Riv Psichiatr. 56:85–92.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Italian).

|

|

46

|

Facciolà A, Micali C, Visalli G, Venanzi

Rullo E, Russotto Y, Laganà P, Laganà A, Nunnari G and Di Pietro A:

COVID-19 and pregnancy: Clinical outcomes and scientific evidence

about vaccination. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 26:2610–2626.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ceccarelli M, Nunnari G, Celesia BM,

Pellicanò GF, Venanzi Rullo E, Berretta M and Santi Cacopardo B:

Editorial-Coronavirus disease 2019 and people living with HIV:

Clinical considerations Eur Rev Med. Pharmacol Sci. 24:7534–7539.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Butt I, Sawlani V and Geberhiwot T:

Prolonged confusional state as first manifestation of COVID-19. Ann

Clin Transl Neurol. 7:1450–1452. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Beach SR, Praschan NC, Hogan C, Dotson S,

Merideth F, Kontos N, Fricchione GL and Smith FA: Delirium in

COVID-19: A case series and exploration of potential mechanisms for

central nervous system involvement. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 65:47–53.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Zazzara MB, Penfold RS, Roberts AL, Lee

KA, Dooley H, Sudre CH, Welch C, Bowyer RCE, Visconti A, Mangino M,

et al: Probable delirium is a presenting symptom of COVID-19 in

frail, older adults: A cohort study of 322 hospitalised and 535

community-based older adults. Age Ageing. 50:40–48. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Tyson B, Shahein A, Erdodi L, Tyson L,

Tyson R, Ghomi R and Agarwal P: Delirium as a presenting symptom of

COVID-19. Cogn Behav Neurol. 35:123–129. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Toniolo S, Di Lorenzo F, Scarioni M,

Frederiksen KS and Nobili F: Is the frontal lobe the primary target

of SARS-CoV-2? J Alzheimers Dis. 81:75–81. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Harapan BN and Yoo HJ: Neurological

symptoms, manifestations, and complications associated with severe

acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and

coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). J Neurol. 268:3059–3071.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Pensato U, Muccioli L, Cani I, Janigro D,

Zinzani PL, Guarino M, Cortelli P and Bisulli F: Brain dysfunction

in COVID-19 and CAR-T therapy: Cytokine storm-associated

encephalopathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 8:968–979. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Østergaard L: SARS CoV-2 related

microvascular damage and symptoms during and after COVID-19:

Consequences of capillary transit-time changes, tissue hypoxia and

inflammation. Physiol Rep. 9(e14726)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Velásquez-Tirado JD, Trzepacz PT and

Franco JG: Etiologies of delirium in consecutive COVID-19

inpatients and the relationship between severity of delirium and

COVID-19 in a prospective study with follow-up. J Neuropsychiatry

Clin Neurosci. 33:210–218. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Schneider F, Agin A, Baldacini M, Maurer

L, Schenck M, Alemann M, Solis M, Helms J, Villette C, Artzner T,

et al: Acute-onset delirium in intensive care COVID patients:

Association of imperfect brain repair with foodborne

micro-pollutants. Eur J Neurol. 28:3443–3447. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Cuperlovic-Culf M, Cunningham EL,

Teimoorinia H, Surendra A, Pan X, Bennett SAL, Jung M, McGuiness B,

Passmore AP, Beverland D and Green BD: Metabolomics and

computational analysis of the role of monoamine oxidase activity in

delirium and SARS-COV-2 infection. Sci Rep.

11(10629)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Moretti P, Brufani F, Pierotti V, Pomili

G, Di Buò A, Giulietti C, Masini F, Tanku V, Bachetti MC, Menculini

G and Tortorella A: Neurotropism and neuropsychiatric symptomsi in

patients with COVID-19. Psychiatr Danub. 33 (Suppl 11):S10–S13.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Batra A, Clark JR, Kang AK, Ali S, Patel

TR, Shlobin NA, Hoffman SC, Lim PH, Orban ZS, Visvabharathy L, et

al: Persistent viral RNA shedding of SARS-CoV-2 is associated with

delirium incidence and six-month mortality in hospitalized COVID-19

patients. Geroscience. 44:1241–1254. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Dias R, Caldas JP, Silva-Pinto A, Costa A,

Sarmento A and Santos L: Delirium severity in critical patients

with COVID-19 from an infectious disease intensive care unit. Int J

Infect Dis. 118:109–115. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Shao SC, Lai CC, Chen YH, Chen YC, Hung MJ

and Liao SC: Prevalence, incidence and mortality of delirium in

patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age

Ageing. 50:1445–1453. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Pranata R, Huang I, Lim MA, Yonas E, Vania

R and Kuswardhani RAT: Delirium and mortality in coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19)-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch

Gerontol Geriatr. 95(104388)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Rebora P, Rozzini R, Bianchetti A,

Blangiardo P, Marchegiani A, Piazzoli A, Mazzeo F, Cesaroni G,

Chizzoli A, Guerini F, et al: Delirium in patients with SARS-CoV-2

infection: A multicenter study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 69:293–299.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Hariyanto TI, Putri C, Hananto JE, Arisa

J, Fransisca V, Situmeang R and Kurniawan A: Delirium is a good

predictor for poor outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) pneumonia: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and

meta-regression. J Psychiatr Res. 142:361–368. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Peterson A, Marengoni A, Shenkin S and

MacLullich A: Delirium in COVID-19: Common, distressing and linked

with poor outcomes. can we do better? Age Ageing. 50:1436–1438.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Morandi A, Rebora P, Isaia G, Grossi E,

Faraci B, Gentile S, Bo M, Valsecchi MG, Deiana V, Ghezzi N, et al:

Delirium symptoms duration and mortality in SARS-COV2 elderly:

Results of a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Aging Clin Exp

Res. 33:2327–2333. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Mcloughlin BC, Miles A, Webb TE, Knopp P,

Eyres C, Fabbri A, Humphries F and Davis D: Functional and

cognitive outcomes after COVID-19 delirium. Eur Geriatr Med.

11:857–862. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Liu YH, Wang YR, Wang QH, Chen Y, Chen X,

Li Y, Cen Y, Xu C, Hu T, Liu XD, et al: Post-infection cognitive

impairments in a cohort of elderly patients with COVID-19. Mol

Neurodegener. 16(48)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Duggan MC, Van J and Ely EW: Delirium

assessment in critically Ill older adults: Considerations during

the COVID-19 Pandemic. Crit Care Clin. 37:175–190. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Meagher D, Adamis D, Timmons S, O'Regan

NA, O'Keeffe S, Kennelly S, Corby C, Meaney AM, Reynolds P, Mohamad

M, et al: Developing a guidance resource for managing delirium in

patients with COVID-19. Ir J Psychol Med. 38:208–213.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Rahman S and Byatt K: Follow-up services

for delirium after COVID-19-where now? Age Ageing. 50:601–604.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Hara M, Kouda K, Mizoguchi T, Yokota Y,

Hayashi K, Gon Y and Nakajima H: COVID-19 post-infectious

encephalitis presenting with delirium as an initial manifestation.

J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep.

9(23247096211029787)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Aroos R, Wong BLL and Merchant RA: Delayed

health consequences of COVID-19 lockdown in an older adult. Age

Ageing. 50:673–675. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Ragheb J, McKinney A, Zierau M, Brooks J,

Hill-Caruthers M, Iskander M, Ahmed Y, Lobo R, Mentz G and Vlisides

PE: Delirium and neuropsychological outcomes in critically Ill

patients with COVID-19: A cohort study. BMJ Open.

11(e050045)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Mendes A, Herrmann FR, Périvier S, Gold G,

Graf CE and Zekry D: Delirium in older patients with COVID-19:

Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical relevance. J Gerontol A Biol

Sci Med Sci. 76:e142–e146. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Fabrazzo M, Russo A, Camerlengo A, Tucci

C, Luciano M, De Santis V, Perris F, Catapano F and Coppola N:

Delirium and cognitive impairment as predisposing factors of

COVID-19 infection in neuropsychiatric patients: A narrative

review. Medicina (Kaunas). 57(1244)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Ekmekyapar T, Ekmekyapar M, Tasci I, Sahin

L and Delen LA: Clinical features and predisposing factors of

delirium due to COVID-19 pneumonia in intensive care units. Eur Rev

Med Pharmacol Sci. 26:4440–4448. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Pagali S, Fu S, Lindroth H, Sohn S, Burton

MC and Lapid M: Delirium occurrence and association with outcomes

in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 33:1105–1109.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

van Reekum EA, Rosic T, Sergeant A, Sanger

N, Rodrigues M, Rebinsky R, Panesar B, Deck E, Kim N, Woo J, et al:

Delirium and other neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19

infection in people with preexisting psychiatric disorders: A

systematic review. J Med Case Rep. 15(586)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Dinakaran D, Manjunatha N, Naveen Kumar C

and Suresh BM: Neuropsychiatric aspects of COVID-19 pandemic: A

selective review. Asian J Psychiatr. 53(102188)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Munjal S, Ferrando SJ and Freyberg Z:

Neuropsychiatric aspects of infectious diseases: An update. Crit

Care Clin. 33:681–712. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, Liang HR, Chen

ZS, Li YM, Liu XQ, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, et al: Comorbidity and

its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: A nationwide

analysis. Eur Respir J. 55(2000547)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

D'Ardes D, Carrarini C, Russo M, Dono F,

Speranza R, Digiovanni A, Martinotti G, Di Iorio A, Onofrj M,

Cipollone F and Bonanni L: Low molecular weight heparin in COVID-19

patients prevents delirium and shortens hospitalization. Neurol

Sci. 42:1527–1530. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Martinotti G, Bonanni L, Barlati S, Miuli

A, Sepede G, Prestia D, Trabucco A, Palumbo C, Massaro A, Olcese M,

et al: Delirium in COVID-19 patients: A multicentric observational

study in Italy. Neurol Sci. 42:3981–3988. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Boer H, Soekhai MTD, Renes MH, Schoevers

RA and Jiawan VCR: Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 in

intensive care unit patients. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 63:509–513.

2021.PubMed/NCBI(In Dutch).

|

|

87

|

Haller J: Aggression, aggression-related

psychopathologies and their models. Front Behav Neurosci.

16(936105)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Merlo EM, Stoian AP, Motofei IG and

Settineri S: The role of suppression and the maintenance of

euthymia in clinical settings. Front Psychol.

12(677811)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Sweileh WM: Research trends and scientific

analysis of publications on burnout and compassion fatigue among

healthcare providers. J Occup Med Toxicol. 15(23)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Merlo EM, Stoian AP, Motofei IG and

Settineri S: Clinical psychological figures in healthcare

professionals: Resilience and maladjustment as the ‘Cost of Care’.

Front Psychol. 11(607783)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Arbelo N, López-Pelayo H, Sagué M, Madero

S, Pinzón-Espinosa J, Gomes-da-Costa S, Ilzarbe L, Anmella G, Llach

CD, Imaz ML, et al: Psychiatric clinical profiles and

pharmacological interactions in COVID-19 inpatients referred to a

consultation liaison psychiatry unit: A cross-sectional study.

Psychiatr Q. 92:1021–1033. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Italian Society of Psychiatry:

Recommendations on activities and measures to contrasts and

contains SARS-CoV-19 virus. https://www.evidence-based-psychiatric-care.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SARS-COV-19_Suppl_Speciale_Rivista_SIP_ita.pdf.pdf.

Acessed April 05, 2020.

|

|

93

|

Baller EB, Hogan CS, Fusunyan MA, Ivkovic

A, Luccarelli JW, Madva E, Nisavic M, Praschan N, Quijije NV, Beach

SR and Smith FA: Neurocovid: Pharmacological recommendations for

delirium associated with COVID-19. Psychosomatics. 61:585–596.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Khosravi M: Letter to the editor:

Quetiapine safety in ICU delirium management among

SARS-CoV-2-infected patients. J Psychosom Res.

149(110598)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Marino A, Campanella E, Ceccarelli M,

Larocca L, Bonomo C, Micali C and Cacopardo B: (2022). Sarilumab

administration in patients with severe COVID-19: A report of four

cases and a literature review. World Acad Sci J 4, 24. https://doi.org/10.3892/wasj.2022.159.

|

|

96

|

Marino A, Pampaloni A, Scuderi D,

Cosentino F, Moscatt V and Ceccarelli M.: Cacopardo, B. (2020):

High-flow nasal cannula oxygenation and tocilizumab administration

in patients critically ill with COVID-19: A report of three cases

and a literature review. World Acad Sci J 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3892/wasj.2020.64.

|

|

97

|

Ceccarelli M, Pavone P, Venanzi Rullo E

and Nunnari G: Comment on safety and efficacy of oral

lopinavir/ritonavir in pediatric patients with coronavirus disease:

A nationwide comparative analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

25:2473–2474. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Syed S, Couse M and Ojha R: Management

challenges in patients with comorbid COVID-19 associated delirium

and serious mental illness-A case series. Int J Psychiatry Med.

56:255–265. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Mota P: Delirium in COVID-19 elderly

patients: Raising awareness to the importance of its early

detection and therapeutic intervention. Acta Med Port.

34(318)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In

Portuguese).

|

|

100

|

Radhakrishnan NS, Mufti M, Ortiz D, Maye

ST, Melara J, Lim D, Rosenberg EI and Price CC: Implementing

delirium prevention in the Era of COVID-19. J Alzheimers Dis.

79:31–36. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Castro REV, Garcez FB and Avelino-Silva

TJ: Patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Do not leave

delirium behind. Braz J Psychiatry. 43:127–128. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|