1. Introduction

Over the past 2.5 years, the worldwide population

has been experiencing an unprecedented viral outbreak, hitherto

known only from history, namely the coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-2019) pandemic. Mankind has experienced other pandemics in

the past, which were treated according to the data, possibilities

and facilities available at the time in terms of medicines,

scientific knowledge and means of prevention.

Currently, with the COVID-19 pandemic, although

there have been tremendous advancements in science, technology has

also proven useful in dealing with difficult situations with

greater ease and the majority of individuals have direct access to

knowledge if they wish. However, the coronavirus was something

unknown, and its impact was aggressive and lethal that it forced

the majority of countries worldwide to impose strict precautionary

measures and to implement lockdowns for weeks or even months. In

addition to the impact these measures have had and continue to have

on the economy and on businesses, many of which have been forced to

close, the psychology of individuals has also been negatively

affected. Some individuals have either lost a relative due to the

disease, or have become ill themselves, or others have lost their

jobs and have been devastated financially; all these negative

effects have also caused a notable amount of distress among

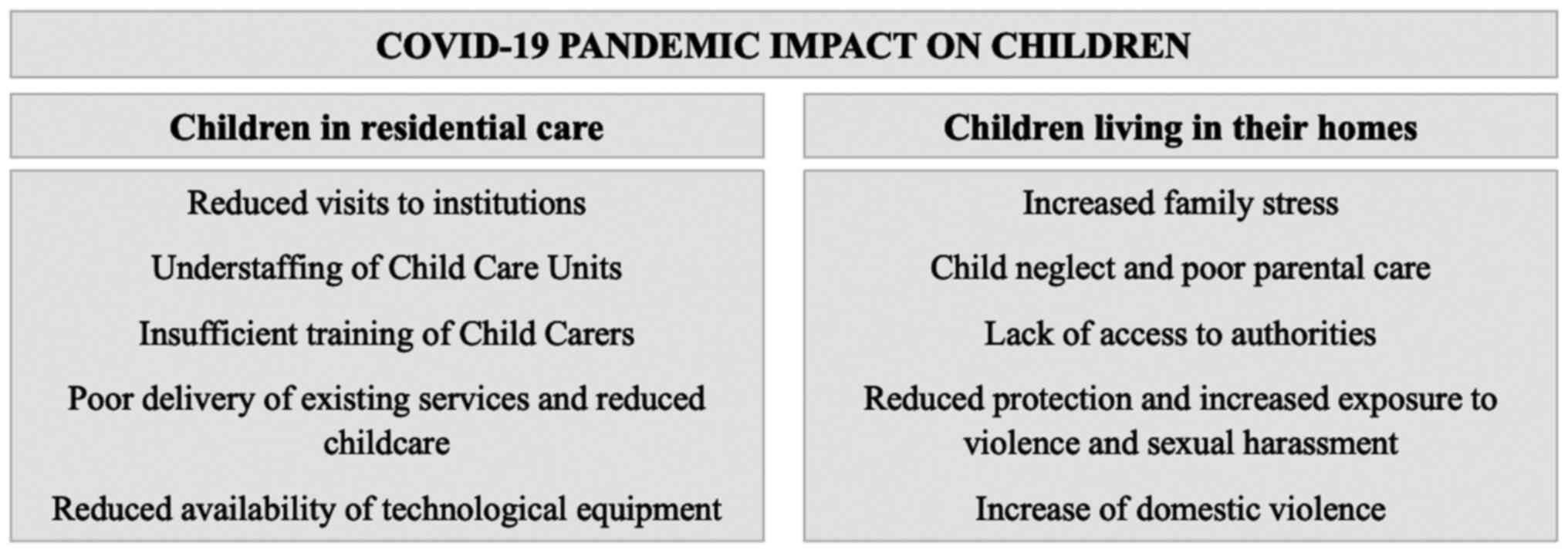

children (1). The situation of

both children residing with their families in their homes and

children in care facilities has been affected (Fig. 1).

According to the World Health Organization, since

the start of the pandemic, the identified risk factors for the

maltreatment in children have escalated. Such risk factors include

economic insecurity, social isolation and family stress (2). UNICEF, in its report on the pandemic

(3), has also identified three

main potential secondary impacts on children and their caregivers.

Firstly, child neglect and the lack of parental care and concern

was identified, mental health and mental distress were also

identified, and finally, reduced protection and increased exposure

to violence and sexual harassment were identified.

2. Children in residential care

Reduced number of visits to

institutions

With the pandemic and the ongoing lockdowns that

have been implemented in the majority of countries worldwide, there

has also been a disruption in the continuity of care for the guests

in caregiving facilities, as well as a lack of coordination between

organizations, to ensure basic service delivery. Automatically with

these changes, key activities to ensure the protection of children

were also reduced (4). The

majority of children residing in institutions and other protection

shelters during the crisis and along with the measures taken for

coronavirus, have received very limited care services compared to

those received before the pandemic.

A key deprivation that is a fact is the much-reduced

frequency of visits to children residing in shelters by their

biological relatives. Due to repeated long-term implementation of

lockdowns, during which individuals were prohibited from any

outdoor events or external visits, even to visit their children,

children in the childcare facilities were only able to see their

caregivers. Moreover, when the first lockdowns were lifted, the

measures in the closed shelters remained very strict, often for a

long period of time. One of these measures involved a ban on visits

by any outside visitors. When these measures began to be relaxed

and relatives were allowed to visit their children again, they were

required to be vaccinated and at the same time to produce a

negative rapid test or a negative PCR test; however, the relatives

themselves were required to bear the cost of these tests. Usually,

the financial situation of the relatives of children living in

shelters is extremely poor and are barely able cover the costs of

their daily living. When a rapid test per week costs 8-10 Euros,

plus travel to and from the shelter, it is very difficult for them

to respond consistently. Another version of the same problem is the

emergence of a positive case of coronavirus within the shelter

itself. If a member of the care staff or one of the hosted children

has become ill, automatically the whole chamber in which the child

is staying, or even the entire facility when there is a spread, is

placed into isolation for days or even weeks, resulting in the

children not being able to meet their relatives.

Understaffing of childcare units due

to workers becoming ill with COVID-19

Throughout the pandemic, in numerous childcare

facilities, as well as in other care facilities for the elderly or

disabled or in hospitals, caregivers, nurses, doctors and other

care staff were required to work for extremely long hours and under

strenuous conditions, often wearing suffocating and exhausting

equipment (masks, gloves, caps, full body suits to protect

themselves from exposure to the virus); numerous workers did not

manage to avoid becoming ill before the vaccines were administered

for partial protection. When some workers initially became ill,

they were automatically quarantined to protect themselves and to

allow for recovery, but also to protect inpatients and guests, as

well as other workers in the institution. At the beginning of the

pandemic, when things were particularly harsh and severe, anyone

who became ill, and anyone who had come into contact with them, was

required to be absent from work for at least 14 days. They could

only return to work if they produced a negative PCR test and had no

active symptoms (cough, runny nose, headache or fever).

Furthermore, those who were not essential in meeting the basic

needs of the guests or inpatients were not even admitted to the

accommodation. This gradually changed after vaccinations became

available and after the first mutations of the virus indicated that

it was weaker and therefore, less dangerous. This reduced the

number of days of isolation and quarantine to 10 and subsequently

to 5.

According to the study by Fallon et al

(5), the emergency measures taken

against COVID-19 were effective against the spread of the virus;

however, the effect these measures had on children's shelters was

the intermittent, reduced and ultimately poor delivery of existing

services. Facilities remained understaffed for long periods of time

and less necessary services (such as speech therapies, occupational

therapies, physical therapies and psychotherapies) were

discontinued for long periods of time. These gradually resumed with

fairly strict protective measures, due to the event of a positive

case in a closed accommodation facility.

No possibility of providing technology

to children in institutions

With the closure of schools and the impossibility of

providing e-learning in the shelters, the children residing there

have been isolated for months from school, lessons, teachers and

their classmates. Their daily lives and habits were disrupted, with

negative consequences for their mental health, as articulated in

the study by Haffejee and Levine (6) on the experiences and impact of the

pandemic on children residing in shelters in South Africa. School

closures, the disruption of daily habits, isolation from friends

and peers, and fear of the unknown, resulting from the pandemic,

can cause increased feelings of anxiety and distress (6). Children's outings and certain

activities, accompanied by volunteers, which are very helpful and

useful for children residing in shelters, were terminated

immediately and in several cases, never resumed. The volunteers

employed in these shelters are often individuals >60 years of

age, who were identified during the coronavirus pandemic as being

in the vulnerable population; the volunteers themselves were also

restricted by the measures and confinement in their homes. Even

today, a number of individuals >60 years of age find it

difficult to ‘feel free’ to coexist with others in enclosed spaces.

and to return to their old habits and activities. All this has had

a tremendous impact on the developmental situation of the children

in their care. It is already known that institutionalization has a

negative, even abusive effect on the psychosomatic development of

children residing in institutions, and currently, with the

adversities created by the coronavirus, the situation has taken on

marked proportions (7,8).

Insufficient training and information

for staff in childcare units

According to the data and research, it appears that

caregivers, social workers and other members of the treatment teams

that provide care for children in shelters, have little or no

training beyond what is required to recognize any signs of abuse.

The need for training for those involved in child care, is deemed

necessary even during the pandemic, using tools that have become

widely known over the past few years, e.g. e-learning (9).

3. Children being raised in their homes

Increased family stress

The amount of stress inflicted on families with the

advent of COVID-19 markedly increased due to uncertainty about the

future, and concerns about the job of each parent, the health and

safety of each family member, and the general economic crisis that

isolation, illness and uncertainty can bring to a household. This

is a risk factor that can increase the chances of parents becoming

abusive and exhibiting neglectful behavior against their children

(2). Parental stress is compounded

by the stress that each individual child also faces. Social

isolation, the interruption of contact with their friends,

classmates and teachers, as well as fear of the unknown, of their

own and other the health of other family members, placed additional

stress on parents who were required to manage a burdened situation.

This resulted in even more intensely abusive and neglectful

behavior of the parent towards their children (10).

Another major risk factor, as reported in the study

by Tummala and Muhammad (11), was

the high probability of an economic disaster that a family may

experience as a consequence of the pandemic and the difficulties

that arise even in meeting the basic needs that a family requires

to survive. This markedly increases the chances of even the young

girls of a family being forced into marriage or child trafficking.

Numerous families are also likely to be forced into homelessness

(11).

In addition, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a number

of individuals lost their jobs, which led to difficulties in paying

debts and everyday expenses. Numerous families also found it very

difficult to pay their rent, buy essentials and other activities of

daily living, such as food, clothing, public transport and

scheduled medical check-ups, thus increasing the neglect of

children living with these families (12).

Reduction in reports of violence due

to lack of access to authorities

Despite the apparently difficult conditions that

prevailed during the lockdowns, and while everything was conducive

to an increase in various forms of abuse, the numbers of reports of

child abuse decreased (13). A

very notable point made in the study by Salt et al (14) was that 67% of child abuse cases in

the USA in 2018 were reported by individuals who were primarily

associated with children due to their profession (e.g., teachers,

caregivers, lawyers, health care professionals, etc.) and only 16%

of the reports were made by a relative, a neighbor, or friend.

During the pandemic and lockdowns, the physical contact of these

individuals with children was almost zero. This was mainly due to

the fact that the children were following tele-education programs

and in health care the data changed in a similar manner.

Tele-health was markedly enhanced, with experts encouraging

patients to use it in every way possible, thus avoiding their

physical presence in hospital premises, unless this was an

emergency. This led to a reduction in the number of reports of

child abuse; this reduction did not occur due to decrease in the

phenomenon, but due to the fact that children who were being abused

in any form no longer had a ‘voice’ to be heard. In some areas,

such as Kentucky, USA, the number of complaints received by the

Cabinet for Health and Family Services for incidents of child abuse

decreased by 43% from the spring of 2019 to the spring of

2020(14). Nationally, over the

same time period, the rates of allegations received by the Cabinet

for Health and Family Services decreased by 20-70% (15). It was not possible to record events

as everyone was confined to their own homes and was thus not aware

of the situation behind the locked doors of other homes. Along with

everyone, the children were also confined to their homes, most

likely with one of the family members who was equally abusive

towards them (10).

The study by Katz and Cohen (16) explained the reduction in the number

of complaints in a similar manner, citing the importance of schools

in safeguarding and protecting children. During the implementation

of lockdowns, children were not only denied access to public spaces

in which they were more protected due to the crowds, but also did

not come into contact with other adults, such as teachers, gym

teachers, school nurses and other school workers, who observe

children in their daily lives and at the appearance of some

characteristic of abuse, alert the relevant authorities (17).

As reflected in various studies conducted during

these years of the pandemic, there appear to be decreases in the

number of reports of abuse during the pandemic (18-25).

Of note, data collected from various countries and have revealed

increases in the number of complaints in some areas and decreases

other areas. More specifically, in Quebec, Canada, the Director of

Youth Protection, from mid-March to the end of May, 2019 had

received 2,473 complaints of some type of child abuse, while for

the same period in 2020, there was a 33.4% decrease, with only

1,647 complaints, and in May, 2020 the lowest rate in their history

was recorded. A similar situation was observed in Ontario, Canada,

with the rates of complaints decreasing by 40%, where the largest

percentage of complaints were made by the children's teachers.

Typically, during the pandemic, one agency receiving such

complaints received 27 calls from teachers, whereas two years

earlier, it had received 158 similar calls. In Colombia, comparing

the time periods from March to June, 2019 and from March to June,

2020, a 21% decrease in the number of complaints of child abuse was

also noticeable. Finally, in Germany, there appeared to be no

increase in the number of complaints amidst a lockdown. In most

cases, there was no increase, although in many cases, there was a

decrease in the number of calls for complaints of abuse (17).

Reports on domestic violence increase

during the pandemic

However, the data appear to be reversed in a few

other studies. According to data published in the journal Archives

of Disease in Childhood, at Great Ormond Street Hospital For

Children NHS Foundation Trust in London, there was a 1493% increase

in domestic child abuse during the coronavirus pandemic. This was

noted for the period between March 23 and April 23, 2020 and the

same period in 2017, 2018 and 2019, and relates to new cases of

head injuries in young children aged 17 days to ~13 months

resulting from physical violence and abuse (26). In addition, in their study, Salt

et al (14) identified and

reported the finding that in Kentucky, USA, the rates of physical

abuse and maltreatment before and after the closure of schools due

to the pandemic did not exhibit a statistically significant

difference, although the incidence of sexual abuse after the

closure of schools due to COVID-19 exhibited an 85% increase. The

study by Katz et al (27)

demonstrated a decrease in reports in the majority of the countries

studied; in South Africa there was an increase; specifically,

during the lockdown, there was a 400% increase in the number of

calls to Childline South Africa regarding infant abuse and

abandonment. In numbers, this translates into at least 30 infant

abandonments (27). Finally, it

appears that despite the reduced number of complaints, there was an

increase in the number of child abuse injuries in hospitals. In the

study by Kovler et al (28), which recorded cases at John Hopkins

Children's Center (JHCC) Hospital, designated by the Maryland

Institute of Emergency Medical Services Systems (MIEMSS) as a level

I pediatric trauma center and regional burn center, it appears that

during the COVID-19 pandemic, 8 children were diagnosed with child

abuse injuries, representing 13% of all trauma patients, compared

to 4 children diagnosed in 2019 representing 4% of all trauma

patients and 3 children diagnosed in 2018 representing 3% of all

trauma patients (28).

At Golisano Children's Hospital of Southwest Florida

during the months of the lockdown, while there was a decrease in

the incidents of child abuse, there was an increase in the number

of children requiring hospitalization for injuries resulting from

abuse. At the same time, there has been a more than doubling of

reports to the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children,

reaching approximately 2,000,000 reports in March, 2020, compared

to ~984,000 in March, 2019(29).

In France during the period 2017-2020, which

includes the first lockdown, while the number of children who

suffered physical violence was not markedly altered compared to

previous years, the number of hospitalizations of children up to 5

years of age with injuries from physical violence increased by 40%

(30).

4. Conclusions and future perspectives

It appears from the data and studies that have been

conducted, that in the majority of countries where it was possible

to record and collect data on child abuse in the midst of pandemic

and lockdowns, calls and reports of child abuse not only did not

increase, but decreased by a fairly large percentage. In a few

cases, it appears that the numbers remained stable and in a few

cases, there was a slight increase. However, although there has

been a decrease in the number of complaints of child abuse, there

has been an increase in the number of injuries in hospitals with

injuries associated with child abuse. The services provided in

childcare facilities have also been markedly reduced, with the

exclusion of children from outings, activities, school and visits

by relatives and volunteers dominating the very difficult

conditions they have had to experience. Furthermore, with the

stringent measures implemented in the closed children's shelters,

the protection of the hosted children was also interrupted.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already given several

countries cause for concern in terms of the number of children

being abused during the lockdowns, while it was not possible to

record these events during this period of confinement. Planning is

required globally to enable competent authorities to reach out to

families, parents and caregivers who are struggling to cope with

the hardships caused and continue to be caused by the coronavirus.

Without the right support and help, the amount of stress placed on

adults (due to fear of the unknown, uncertainty about the future)

causes them to react negatively towards their children the fatigue.

Strategies of observation, help and support are required for

children who are usually victims of psychological, verbal or

physical violence or even sexual abuse from their relatives or

caregivers. Children who are subjected to violence need to know

that there is someone they can turn to when the need arises. There

should be intensive information and ongoing training for teachers,

therapists and individuals working with children at a distance

during the pandemic so that are able to recognize possible signs of

violence within or outside their family environment and report them

to the relevant authorities for further investigation. Children

should be constantly informed, whether through social media,

television advertisements or posters on the streets, of the

possibility of contacting a hotline to report incidents of abuse

inside or outside their homes and families. Municipalities should

set up teams of experts with experience in child abuse, who would

visit homes in the municipality to which they belong to record

situations they identify or testimonies from people in the

neighborhoods concerning possible cases of violence against

children, and then carry out social checks and interventions in

suspected cases. The new challenge for governments worldwide is to

develop strategies to coordinate the new world order so that all

individuals learn to co-exist with the coronavirus, and all

services can begin to function again with improved conditions for

greater safety and greater convenience. A major challenge that will

affect the world in the following years will be the impact of the

COVID-19 breakout and the lockdowns during the first 2 years of the

pandemic on the psychological state and mental health of children

and adults. Primary affects that are already recorded indicate a

significant deterioration of the mental health of children and

adults, and a five-fold increase in the possibility of future

adverse mental health symptoms in parents and caregivers. It is

thus expected that the long-term effects of the pandemic on mental

health will be revealed in the forthcoming future and will be the

focus of ample amounts of research and discussion on how

governments, authorities, communities and households can act in a

preventive and therapeutic manner for the protection of the mental

wellbeing during such strenuous times.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the

following organizations: i) AdjustEBOVGP-Dx (RIA2018EF-2081):

Biochemical Adjustments of native EBOV Glycoprotein in Patient

Sample to Unmask target Epitopes for Rapid Diagnostic Testing. A

European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership

(EDCTP2) under the Horizon 2020 ‘Research and Innovation Actions’

DESCA; and ii) ‘MilkSafe: A novel pipeline to enrich formula milk

using omics technologies’, a research co-financed by the European

Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national

funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness,

Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call

RESEARCH-CREATE-INNOVATE (project code: T2EDK-02222).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All authors (ED, EP, FB, EE, GPC and DV) contributed

to the conceptualization, design, writing, drafting, revising,

editing and reviewing of the manuscript. All authors confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

GPC is an Editorial Advisor of the journal, but had

no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence

in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article.

The other authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gromada A, Richardsoni D and Rees G:

Childcare in a global crisis: The impact of Covid-19 on work and

family life. UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti, Florence, Italy,

2020.

|

|

2

|

World Health Organization (WHO). Mental

health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19

outbreak. WHO, Geneva, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1.

Accessed March 18, 2020.

|

|

3

|

UNICEF. COVID-19 and its implications for

protecting children online. https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/COVID-19-and-Its-Implications-for-Protecting-Children-Online.pdf.

Accessed April 12, 2020.

|

|

4

|

Fallon N, Lefebvre R, Collin-Vézina D,

Houston E, Joh-Carnella N, Malti T, Filippelli J, Schumaker K,

Manel W, Kartusch M and Cash S: Screening for economic hardship for

child welfare-involved families during the COVID-19 pandemic: A

rapid partnership response. Child Abuse Negl.

110(104706)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Fallon N, Brown C, Twiddy H, Brian E,

Frank B, Nurmikko T and Stancak A: Adverse effects of

COVID-19-related lockdown on pain, physical activity and

psychological well-being in people with chronic pain. Br J Pain.

15:357–368. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Haffejee S and Levine DT: ‘When will I be

free’: Lessons from COVID-19 for child protection in South Africa.

Child Abuse Negl. 110(104715)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Damaskpoulou E: Factors associated with

physical growth and psychomotor development in institutionalized

children, 2017. https://pergamos.lib.uoa.gr/uoa/dl/frontend/file/lib/default/data/2327849/theFile.

Accessed April 1, 2022.

|

|

8

|

Allen S, Bulic I, Rosenthal E,

Laurin-Bowie C, Roozen S and Cuk V: Institutionalisation and

deinstitutionalisation of children. Lancet Child Adolesc Health.

4(e40)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kimber M, McTavish JR, Vanstone M, Stewart

DE and MacMillan HL: Child maltreatment online education for

healthcare and social service providers: Implications for the

COVID-19 context and beyond. Child Abuse Negl. 116:2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Abramson A: How COVID-19 may increase

domestic violence and child abuse. American Psychological

Association, Washington, DC, 2020. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/domestic-violence-child-abuse.

Accessed February 23, 2022.

|

|

11

|

Tummala P and Muhammad T: Conclusion for

special issue on COVID-19: How can we better protect the mental

health of children in this current global environment? Child Abuse

Negl. 110(104808)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Barboza EG, Schiamberg LB and Pachl L: A

spatiotemporal analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on child abuse

and neglect in the city of Los Angeles, California. Child Abuse

Negl. 116(104740)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Katz I, Priolo-Filho S, Katz C, Andresen

S, Bérubé A, Cohen N, Connell CM, Collin-Vézina D, Fallon B, Fouche

A, et al: One year into COVID-19: What have we learned about child

maltreatment reports and child protective service responses? Child

Abuse Negl. 130(105473)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Salt E, Wiggins AT, Cooper GL, Benner K,

Adkins BW, Hazelbaker K and Rayens MK: A comparison of child abuse

and neglect encounters before and after school closings due to

SARS-Cov-2. Child Abuse Negl. 118(105132)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Welch M and Haskins R: What COVID-19 means

for America's child welfare system, 2020. Brookings, Washington,

DC, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/what-covid-19-means-for-americas-child-welfare-system/.

Accessed March 3, 2022.

|

|

16

|

Katz C and Cohen N: Invisible children and

non-essential workers: Child protection during COVID-19 in Israel

according to policy documents and media coverage. Child Abuse Negl.

116(104770)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Katz C and Fallon B: Protecting children

from maltreatment during COVID-19: Struggling to see children and

their families through the lockdowns. Child Abuse Negl.

116(105084)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Gilbertson WN, Hiles HA and Pop D:

Data-informed recommendations for services providers working with

vulnerable children and families during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Child Abuse Negl. 110(104642)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Guo J, Fu M, Liu D, Zhang B, Wang X and

van IJzendoorn MH: Is the psychological impact of exposure to

COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment

experiences? A survey of rural Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse

Negl. 110(104667)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Petrowski N, Cappa C, Pereira A, Mason H

and Daban RA: Violence against children during COVID-19: Assessing

and understanding change in use of helplines. Child Abuse Negl.

116(104757)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Rapoport E, Reisert H, Schoeman E and

Adesman A: Reporting of child maltreatment during the SARS-CoV-2

pandemic in New York City from March to May 2020. Child Abuse Negl.

116(104719)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tener D, Marmor A, Katz C, Newman A,

Silovsky JF, Shields J and Taylor E: How does COVID-19 impact

intrafamilial child sexual abuse? Comparison analysis of reports by

practitioners in Israel and the US. Child Abuse Negl.

116(104779)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Tsur N and Abu-Raiya H: COVID-19-related

fear and stress among individuals who experienced child abuse: The

mediating effect of complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Child

Abuse Negl. 110(104694)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Whelan J, Hartwell M, Chesher T, Coffey S,

Hendrix AD, Passmore SJ, Baxter MA, den Harder M and Greiner B:

Deviations in criminal filings of child abuse and neglect during

COVID-19 from forecasted models: An analysis of the state of

Oklahoma, USA. Child Abuse Negl. 116(104863)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Cappa C and Jijon I: COVID-19 and violence

against children: A review of early studies. Child Abuse Negl.

116(105053)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Sidpra J, Abomeli D, Hameed B, Baker J and

Mankad K: Rise in the incidence of abusive head trauma during the

COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child. 106(e14)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Katz I, Katz C, Andresen S, Bérubé A,

Collin-Vezina D, Fallon B, Fouché A, Haffejee S, Masrawa N, Muñoz

P, et al: Child maltreatment reports and child protection service

responses during COVID-19: Knowledge exchange among Australia,

Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Israel, and South Africa. Child

Abuse Negl. 116(105078)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kovler ML, Ziegfeld S, Ryan LM, Goldstein

MA, Gardner R, Garcia AV and Nasr IW: Increased proportion of

physical child abuse injuries at a level I pediatric trauma center

during the Covid-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl.

116(104756)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lee Health. COVID-19 fallout: More severe

child abuse injuries during pandemic. Lee Health, Fort Myers, FL,

2020. https://www.leehealth.org/health-and-wellness/healthy-news-blog/coronavirus-covid-19/covid-19-fallout-more-severe-child-abuse-injuries-during-pandemic.

Accessed February 23, 2022.

|

|

30

|

Loiseau M, Cottenet J, Bechraoui-Quantin

S, Gilard-Pioc S, Mikaeloff Y, Jollant F, François-Purssell I, Jud

A and Quantin C: Physical abuse of young children during the

COVID-19 pandemic: Alarming increase in the relative frequency of

hospitalizations during the lockdown period. Child Abuse Negl.

122(105299)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|