Introduction

Nipple adenoma is a rare, benign tumor of the breast

that occurs between the fourth and fifth decades of life,

predominantly affecting females, and very rarely encountered in

accessory breasts (1). The breast

(mammary gland) normally develops in the early embryonic period as

two ectodermal thickenings known as mammary milk lines, which form

along the sides of the embryo during the sixth week of development

and extend from the axillary region to the groin. During normal

development, the majority of the embryonic mammary ridges along the

milk line undergo involution except for two segments in the

pectoral area that eventually become breasts. When one of these

ridges fails to involute, supernumerary breasts form. This

condition, variably known as supernumerary breast, ectopic breast,

or polymastia (2). In 2022, benign

breast tumors were extensively studied with 839 publications.

Common types include fibroadenoma, fat necrosis, papilloma, cyst,

mastitis, hyperplasia, adenoma and granular cell tumors (3). Nipple adenoma, also termed nipple

duct adenoma, papillary adenoma, erosive adenomatosis, florid

papillomatosis, papillomatosis of the nipple and subareolar duct

papillomatosis, represents a subtype of intraductal papilloma

involving the terminal portion of the galactophorous ducts.

Clinically, nipple adenoma can be mistaken for Paget's disease,

while pathologically, it could be misclassified as a tubular

carcinoma. Although axillary tumors have a variety of differential

diagnoses ranging from benign to malignant, nipple neoplasms

arising from axillary accessory breasts are rarely mentioned in the

English literature (4).

The present study reports the case of a patient with

adenoma arising from an accessory breast nipple, and also provides

a brief literature review. The references have been inspected for

reliability (5).

Case report

Patient information

A 23-year-old female patient presented to Smart

Health Tower (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq) with a 4-year history of right

axillary discomfort, pain and swelling. The patient, a non-smoker

with no history of diabetes, had one child and breastfed for ~17

months, with the last lactation occurring ~2 years prior to the

current presentation. An investigation into the surgical history of

the patient revealed a cesarean section, while an analysis of her

family history did not reveal any notable findings.

Clinical finding

Upon a clinical examination, a tender, firm lump was

detected in the right axillary region. The lump did not display

signs of inflammation, such as redness and warmth.

Diagnostic approach

A breast ultrasound (data not shown) revealed a

homogeneous background echotexture with a fibroglandular pattern.

Bilateral accessory axillary breasts were observed, with the right

side being larger, displaying normal morphology without any solid

masses or distortions in either breast. Both primary and accessory

nipples were normal. The breasts exhibited normal skin thickness

and contours, and the axillary lymph nodes were unremarkable.

Unfortunately, the ultrasound images were not captured due to

limited resources in the present country, but the ultrasonography

report was available. Additionally, the complete blood count

results were within the normal range.

Therapeutic intervention

The mass was excised under local anesthesia, with

hemostasis achieved without complications, and the wound was closed

using absorbable sutures. Upon a gross examination, the skin

excisional biopsy measured 1.2x0.8 cm with a thickness of 0.3 cm,

revealing a 0.5-cm skin-covered, exophytic nodule, away from the

peripheral and deep margins.

The histopathological examination was performed as

follows: The specimen was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at

room temperature for a period of 1 to 3 days. It was then processed

using the DiaPath Donatello automated processor, progressing

through the designated stages: Samples were held in 10%

neutral-buffered formalin for an average duration of 20 min, then

placed in deionized water for 10 min. Dehydration was conducted

using alcohol, beginning with a concentration of 70% for 1 h,

followed by 95% for 1 h, 99% for 1 h and 30 min, and another

station of 99% for 1 h and 30 min. Clearing was performed through

three stations of xylene, each lasting 1 h for a total of 3 h.

Finally, infiltration with paraffin wax was carried out in three

stations, each lasting 1 h for a total of 3 h. The blocks were

subsequently embedded in paraffin wax using the Sakura Tissue-Tek

embedding center (Sakura Finetek USA). The blocks were then trimmed

and sectioned with the Sakura Accu-Cut SRM microtome (Sakura

Finetek USA) to a thickness of 5 µm. The sections were floated in a

Sakura 1451 water bath, maintained at 40-50˚C, and then mounted

onto standard glass slides. These slides were then placed in an

oven set at 60-70˚C and left overnight. The following day, the

slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin using the DiaPath

Giotto autostainer, following these stages: First, the slides were

immersed in xylene for three intervals of 7, 7 and 5 min. They were

then treated with 100% alcohol in three stages lasting 7, 6 and 5

min, followed by 90% alcohol for 4 min, 70% alcohol for 3 min, and

then rinsed with tap water for 2 min. They were then stained with

Hematoxylin Gill II for 8 min, prepared from Sigma-Aldrich

Hematoxylin Natural Black 1. This was followed by rinsing in tap

water for 4 min, a brief dip in ammonia water for 1 min, another

tap water rinse for 1 min, and then 70% alcohol for 2 min.

Subsequently, the slides were stained with Eosin for 5 min,

prepared from Sigma-Aldrich Eosin Y disodium salt, followed by a

1-min rinse in tap water. The dehydration process involved 70%

alcohol for 15 sec, 90% alcohol for 2 min, and 100% alcohol in

three stages of 3, 3 and 4 min. The slides were then cleared in

xylene in three stages of 3, 5 and 4 min. After drying for 5 min,

the slides were covered with SurgiPath Sub-X mounting medium and a

coverslip. The microscope used for examination was an Olympus BX-51

microscope with a camera adaptor (Olympus U-TV0.5XC-3) (Olympus

Corporation) for obtaining images.

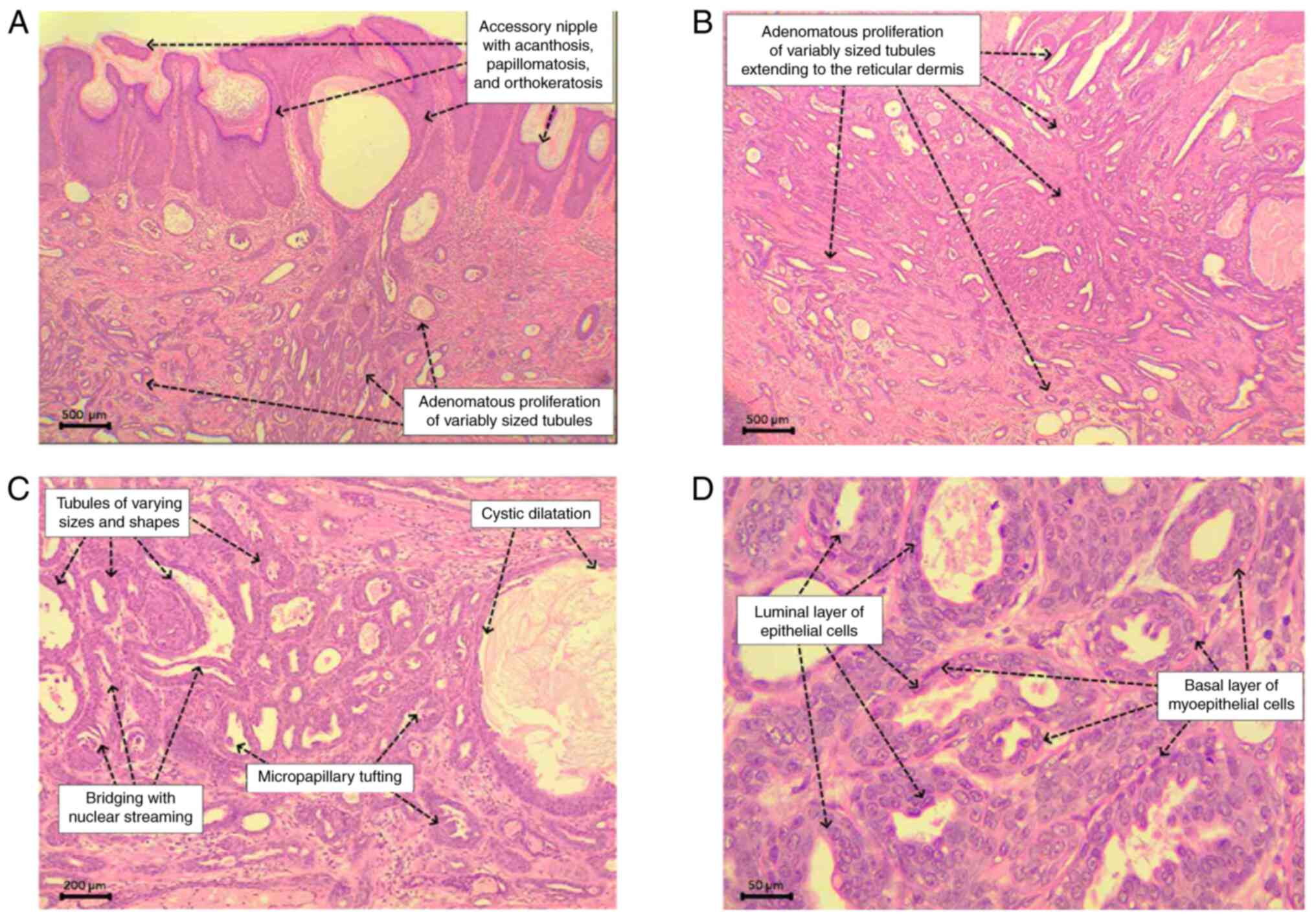

The histopathological examination revealed a

relatively ill-defined proliferation of variably sized ducts within

the dermis. These ducts comprised a basal layer of flat to cuboidal

myoepithelial cells with oval nuclei and fine chromatin, and a

luminal epithelial layer of cuboidal to low columnar cells with

oval nuclei exhibiting more open chromatin and conspicuous

nucleoli, devoid of significant cytologic atypia and atypical

mitotic figures. Some ducts displayed intraluminal micropapillary

proliferation and bridging with streaming nuclei. The surrounding

dermis exhibited fibrosis with patchy and mild mixed inflammatory

cells but lacked a desmoplastic reaction. The overlying epidermis

showed acanthosis, papillomatosis, and orthokeratosis. These

findings were consistent with an adenoma arising within an

accessory nipple (Fig. 1).

Follow-up and outcome

The patient was discharged in good health on the

first post-operative day. A 4-month follow-up revealed no clinical

signs of recurrence.

Discussion

Accessory breast tissue is a relatively uncommon

occurrence ranging from 0.4 to 0.6%, typically originating

alongside the embryogenic mammary ridge, extending from the axilla

to the groin, and is commonly found in the axilla (2). Neoplasms in the axillary nipple can

manifest as either benign or malignant lesions. Nipple adenoma, a

rare benign tumor, develops within the superficial part of the

nipple (6). Paget's disease of the

nipple is the primary differential diagnosis (1). According to the study by Shinn et

al (1), until 2015, only four

published reports of nipple adenoma in an accessory nipple had been

identified. A clinical examination often reveals a palpable lump

and an eroded, ulcerated, or crusted nipple as typical findings

(7). Previous case reports have

documented varying clinical presentations of nipple adenoma in

accessory breasts. For example, Shioi et al (4) described the case of an 82-year-old

female patient with a painful right axillary tumor, whereas,

Malagimani et al (6)

reported the case of a 24-year-old female patient experiencing

continuous pain and bleeding from her right accessory nipple, with

examination revealed no neoplastic lesions or palpable axillary

lymph nodes. In the case in the present study, the patient

presented with a right-sided axillary swelling and a tender firm

lump upon examination.

Nipple adenoma microscopically presents with the

proliferation of a small tubular structures exhibiting a

double-layered appearance, although it can display a wide range of

histopathological features (4).

Rosen and Caicco divided nipple adenomas into four morphological

patterns: i) Sclerosing papillomatosis, which can resemble

sclerosing papilloma; ii) papillomatosis, characterized by florid

papillary hyperplasia of ductal epithelium; iii) adenosis,

featuring evident myoepithelial hyperplasia; and iv) a combination

of these proliferative forms (8).

However, there is no apparent indication of prognostic relevance

associated with these patterns, and there is also a lack of

evidence suggesting variance in their underlying pathogenesis

(9). The case described herein

exhibited a predominant pattern of adenosis admixed with focal

micropapillary formations.

Radiographically, an ultrasound, mammography and

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are commonly utilized modalities

for identifying and characterizing nipple adenomas. Among these, an

ultrasound is considered the most clinically useful, as it can

delineate soft tissue nodularity, assess internal vascularity and

facilitate image-guided fine-needle aspiration. The lesion

typically appears well-defined and hypoechoic on the ultrasound

scan, and may exhibit posterior echo enhancement. The MRI

enhancement curve of nipple adenomas may mimic that of malignant

lesions, displaying rapid uptake, peaking at 60-90 sec followed by

washout, which can lead to diagnostic confusion. The results of

mammography may vary, ranging from benign calcification to dense

lesions with well-defined or irregular edges. It should be noted

that no single imaging modality should be relied upon in isolation

for diagnosing nipple adenoma (10). In the present study, a breast

ultrasound unexpectedly revealed normal accessory breasts and

nipples without evidence of a mass-forming lesion in either the

accessory breasts or the normal breast tissue. In terms of

management, the treatment of choice for an adenoma of the accessory

nipple is the surgical excision of the tumor. This approach ensures

complete removal of the tumor, thus alleviating any associated

symptoms. The prognosis following surgical intervention is

generally favorable, with a low risk of recurrence (10). While the link between breast

adenomas and carcinomas remains incompletely understood, breast

adenomas are generally considered benign tumors. Complete excision

and a histopathological examination are crucial for an accurate

diagnosis and for the prevention of the misdiagnosis of cancer,

thereby avoiding unnecessary and costly surgery (4). In the case presented herein, the mass

was successfully excised under local anesthesia with no

complications, and the subsequent histopathological examination

confirmed the benign nature of the tumor. It is worth highlighting

that the efficient management of the case in the present study

aligns with previous cases reported by in the studies by Shinn

et al (1), Shioi et

al (4) and Malagimani et

al (6).

Nipple adenoma, despite its benign nature, has been

found to be associated with breast cancer in clinical studies, with

some cases revealing concurrent active breast cancer or

clinically-occult invasive disease. Although establishing a direct

causal link remains challenging due to the rarity of malignant

transformation, heightened suspicion for co-existing breast cancer

is warranted in cases of nipple adenoma (8,11,12).

Additionally, the expanding growth pattern and potential for local

recurrence of nipple adenoma can significantly affect the quality

of life of patients, particularly in women of childbearing age

reliant on intact nipple function for breastfeeding. Thus, a

comprehensive clinical evaluation and screening for co-existing

breast cancer are imperative in the management of nipple adenoma

(13).

While specific risk factors for its occurrence in

younger patients have not been extensively studied, several

potential contributors have been suggested. Hormonal fluctuations

due to puberty, menstrual cycles, or hormonal medications may

stimulate breast tissue growth. Genetic predisposition,

particularly with a family history of breast conditions, could

elevate the risk. Reproductive factors, such as early menarche or

nulliparity may also play a role, along with breast trauma or

injury. Lifestyle factors such as diet and alcohol consumption may

contribute as well. However, the exact association between these

factors and nipple adenoma in younger patients requires further

investigation due to the limited evidence available since a

significant portion of the literature concerning nipple adenoma

comprises only individual case reports and series of cases

(14).

In conclusion, adenoma of accessory nipples is a

rare condition that necessitates careful clinical evaluation and

diagnostic workup to ensure proper management. Surgical excision

remains the standard approach for addressing this benign tumor,

with favorable long-term outcomes for affected individuals.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

RMA and AMS were major contributors to the

conception of the study, as well as in the literature search for

related studies. AAQ and FHK were involved in the literature

review, the design of the study and in the writing of the

manuscript. AMA was the pathologist who performed the

histopathological diagnosis. LRAP, HOB, HOA, HMD and ROM were

involved in the literature review, the design of the study, in the

critical revision of the manuscript, and in the processing of the

figure. FHK and RMA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

In our locality, ethical approval is not required

for case studies involving fewer than three cases. Written informed

consent was obtained from the patient for her participation in the

present study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the present study and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Shinn L, Woodward C, Boddu S, Jha P,

Fouroutan H and Péley G: Nipple adenoma arising in a supernumerary

mammary gland: A case report. Tumori. 97:812–814. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Yefter ET and Shibiru YA: Fibroadenoma in

axillary accessory breast tissue: A case report. J Med Case Rep.

16:1–6. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Salih A, Ahmed A, Mohammed S, Qadir A,

Bapir N and Fatah G: Benign tumor publication in one year (2022): A

cross-sectional study. Barw Med J. 1:20–25. 2023.

|

|

4

|

Shioi Y, Nakamura SI, Kawamura S and

Kasami M: Nipple adenoma arising from axillary accessory breast: A

case report. Diagn Pathol. 7(162)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Muhialdeen AS, Ahmed JO, Baba HO, Abdullah

IY, Hassan HA, Najar KA, Mikael TM, Mustafa MQ, Mohammed DA, Omer

DA, et al: Kscien's list; A new strategy to discourage predatory

journals and publishers (Second Version). Barw Med J. 1:30–32.

2023.

|

|

6

|

Malagimani SC, Jashvanth CT,

Kasasomasekhar K and Paga U: Case report: A rare case of accessory

nipple (Polythelia) presenting as papillary adenoma. J Evolution

Med Dent Sci. 3:2005–2008. 2014.

|

|

7

|

Healy CE, Dijkstra B, Walsh M, Hill AD and

Murphy J: Nipple adenoma: A differential diagnosis for Paget's

disease. Breast J. 9:325–326. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Rosen PP and Caicco JA: Florid

papillomatosis of the nipple: A study of 51 patients, including

nine with mammary carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 10:87–101.

1986.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mills SE, Carter D, Greenson JK, Reuter VE

and Stoler MH (eds): Sternberg's diagnostic surgical pathology. 5th

edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA,

2012.

|

|

10

|

Tatterton MR and Fiddes R: Nipple adenoma:

A review of the literature. Ann Breast Surg. 3(e8586)2019.

|

|

11

|

Jones MW and Tavassoli FA: Coexistence of

nipple duct adenoma and breast carcinoma: A clinicopathologic study

of five cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 8:633–636.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gudjónsdóttir A, Hägerstrand I and OStberg

G: Adenoma of the nipple with carcinomatous development. Acta

Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 79:676–680. 1971.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Combi F, Palma E, Montorsi G, Gambini A,

Segattini S, Papi S, Andreotti A and Tazzioli G: Management of

nipple adenomas during pregnancy: A case report. Int Breastfeed J.

18(19)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Berger O, Gersh G and Talisman R: Nipple

adenoma: Systematic review of literature. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob

Open. 12(e5827)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|