Introduction

Environmental factors, such as temperature, salinity

and acidity (pH) can affect the growth of microorganisms and their

response to antibiotics. The spread of pathogens (vector-borne,

waterborne, airborne and foodborne) and the occurrence of disease

are sensitive to the effects of climate change. Fluctuations in

temperature, rainfall, acidity, salinity and El Niño Southern

Oscillation all affect the growth and spread of waterborne

pathogens, such as Vibrio spp. in aquatic environments.

Climate change is expected to increase the rate of antibiotic

resistance in human pathogens by increasing the lateral gene

transfer of mobile genetic resistance genes and increasing

bacterial growth rates, promoting environmental persistence,

carriage and transmission (1). The

study by Mora et al (2)

counted the number of microorganisms that have emerged and

disappeared as a result of climate change. They discovered that 85%

of the 357 infectious diseases controlled by humans have

proliferated, whereas only 16% have decreased due to climate change

(2). Climate change can cause

disease spread for a variety of reasons, including the geographic

expansion of vectors, such as mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, birds and

other mammals as a result of rain, floods, or drought; these

vectors transmit viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites that have

caused several diseases and epidemics, including dengue fever,

plague, malaria, West Nile fever, cholera, trypanosomiasis,

echinococcosis, and Nipah and Ebola viruses. The change in weather

temperature has also placed individuals closer to pathogens and

their habitats, such as increased water activities, which has

increased the occurrence of waterborne illnesses such as cholera,

primary amoebic meningoencephalitis and gastroenteritis,

salmonellosis, shigellosis and others (2).

Another issue is Arctic ice melting due to global

warming, which has resulted in the spread of Bacillus anthracis due

to the reappearance of a previously frozen bacterial strain

(3). In addition, the increasing

rainfall has resulted in a decrease in water salinity, leading to

the appearance of cases of cholera due to the increased quantity of

Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) bacteria in the water

(4). In some situations, climate

change has negatively influenced particular types of diseases,

causing their decline or elimination, such as, SARS, COVID-19,

rotavirus and norovirus enteritis (5,6).

Generally, antimicrobial resistance and climate

change are two of the top health crises; they are connected

directly, and both affect human health by increasing the mortality

rates. On the other hand, indirectly, climate change causes

fluctuating temperatures, storms, forest fires and flooding. This

has produced shifts in the ecosystem, increasing the transmission

of vectors and infections and incorrect antibiotic usage, all of

which lead to increased antimicrobial resistance (7).

Numerous human pathogens, including V.

cholerae, are naturally found in aquatic environments in

rivers, coastal and estuarine habitats. V. cholerae is a key

pathogen that causes cholera and has played a crucial role in human

history. Its ability to survive in a variety of environments is

largely due to the development of a set of adaptation strategies

that enable these bacteria to survive under stresses such as

nutrient deficiency, variations in salinity and temperature, and

resistance to bacteriophage. Such a mechanism is the transformation

to a viable but nonculturable state and has the capacity to grow as

a biofilm on a variety of biotic (chitinous and gelatinous

zooplankton and phytoplankton) and abiotic surfaces, allowing V.

cholerae to disseminate to new watercourses through passive

transfer or mechanical transfer (8).

Similar to V. cholerae, Morganella

morganii (M. morganii) belongs to the

Gammaproteobacteria class of Gram-negative rod bacteria,

which are facultative anaerobic motile bacteria with flagella.

M. morganii is widely distributed in the natural environment

and as a normal flora in the intestinal tracts of humans and

different animals. It is an opportunistic bacterium that clinically

causes nosocomial infections in the urinary tract, hepatobiliary

tract, skin and soft tissue, wounds and blood (9). Previously, little consideration was

paid to these bacteria due to their rarity and low potential for

causing nosocomial epidemics. However, M. morganii was then

classified as a key pathogen due to its high mortality rate in some

infections because of its virulence and elevated antibiotic

resistance. This resistance is essentially acquired via

extragenetic and mobile elements (10).

The impact of climate change on fungal infections is

not yet fully known. Climate change is creating conditions that

encourage the introduction of novel fungal infections and preparing

fungi to adapt to previously hostile habitats. The present study

selected two types of fungi: Aspergillus niger (A.

niger) and Trichoderma harzianum (T. harzianum).

Aspergillus is a genus in the order Eurotiales that has a

global distribution and a diverse range of ecological habitats

(11). Fungi are easily influenced

by nutritional and physiological factors; therefore, even modest

environmental changes can alter their morphological traits

(12). In general, the dietary

requirements for fungal growth are uncomplicated; nonetheless,

various fungi require distinct physical, chemical, and nutritional

environments. As a result, understanding the fungal habitat is

contingent on knowing its temperature, hydrogen ion concentration

(pH) and nutritional requirements. These fungi usually thrive in a

laboratory at temperatures ranging from 0 to 40˚C. Additionally,

the maximum metabolic activity, cellular growth, conidial

generation and sporulation of Aspergillus spp. have been

found in liquid conditions with an optimum pH range of 5-7

(13-15).

Trichoderma, which belongs to the order Hypocreales, can be found

in all climate zones. These fungi are typically found in soil and

rotting wood (16). T.

harzianum has extensive temperature, salinity and pH growth

ranges, suggesting that it can adapt to changes in environmental

conditions (17). The present

study aimed to determine the effects of climate change on the

growth rate and antibiotic resistance of microorganisms living in

surface water.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and isolation of

bacteria

Water was collected from various locations along the

Tigris river in Baghdad, Iraq throughout the year. Water samples

(250 ml) were collected in sterile containers and filtered through

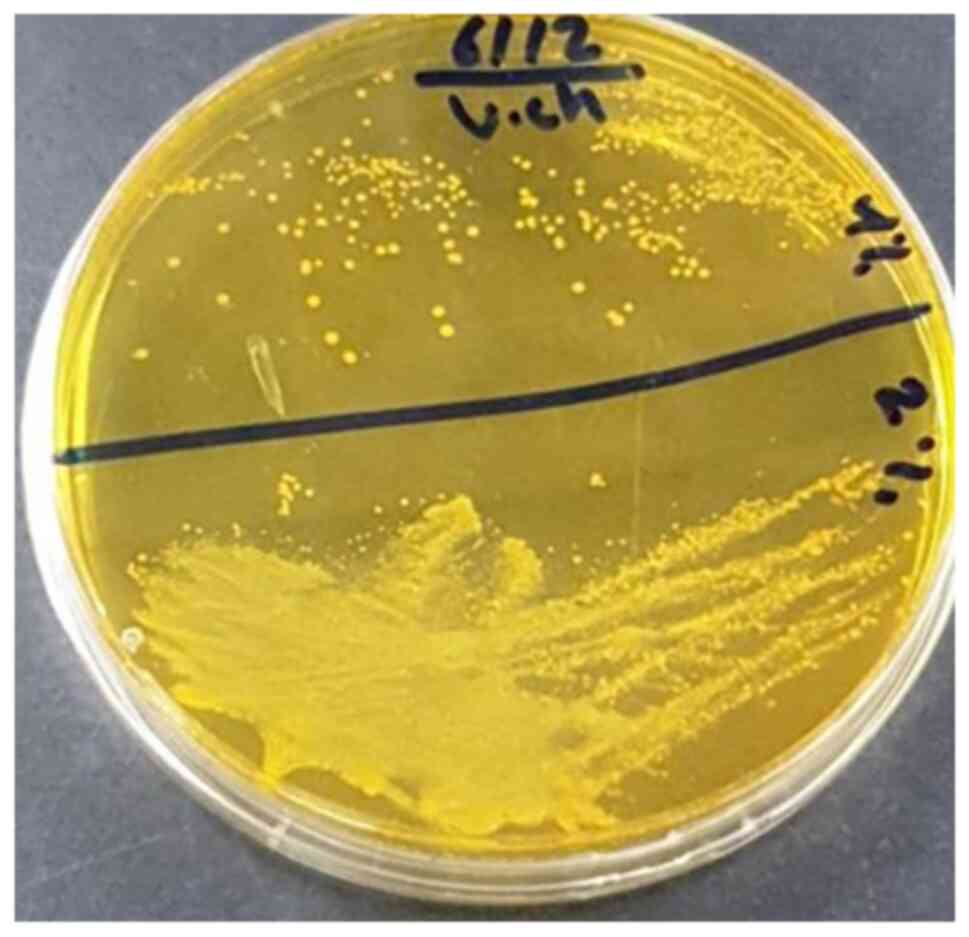

0.22-µm membrane filters. For the isolation of V. cholerae,

the membranes were then incubated in 100 ml alkaline peptone water

(HiMedia Laboratories, LLC) overnight at 37˚C. A loop full of the

overnight culture was streaked onto thiosulfate citrate bile

sucrose (TCBS) agar (HiMedia Laboratories, LLC) and incubated at

37˚C overnight, as previously described (18). Yellow colonies were examined under

a compound microscope (Olympus Corporation), and the comma-shaped

colonies were then diagnosed after 6-7 h using a Vitek 2 compact

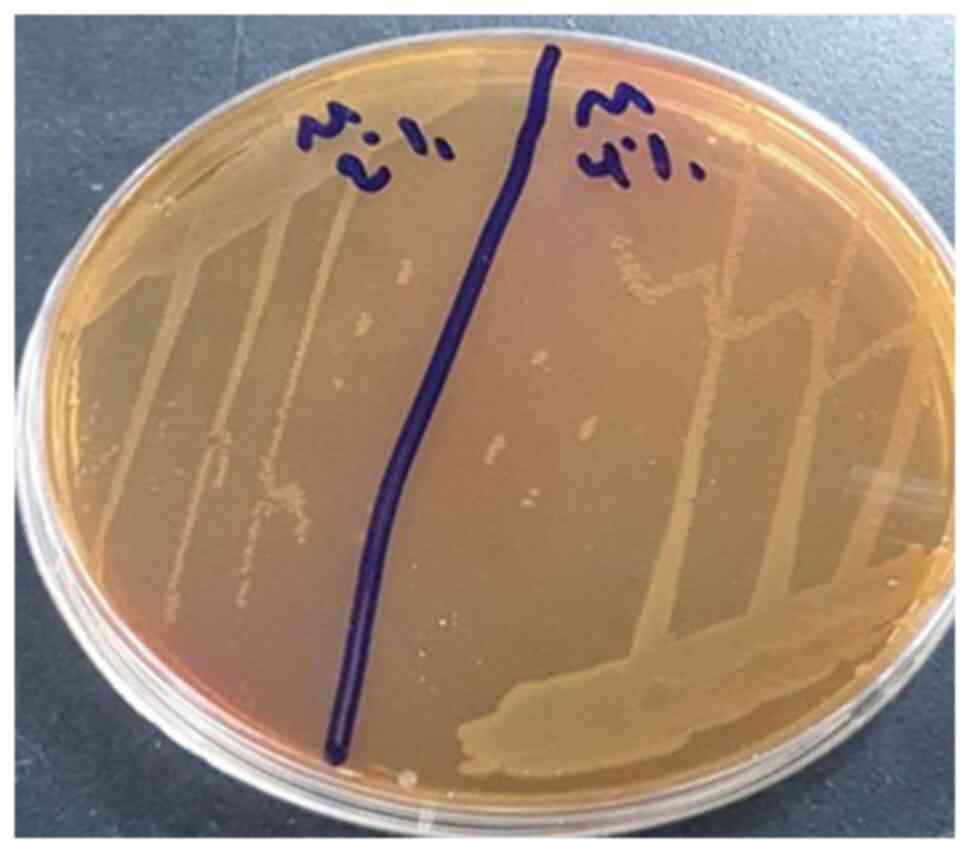

system (Biomerieux). To isolate M. morganii, the membranes

were incubated for 24 h at 37˚C in 100 ml nutrient broth (Oxoid;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently, a loop full of

overnight culture was streaked on MacConkey agar (HiMedia

Laboratories, LLC), and the pale, non-lactose-fermented colonies

were diagnosed using a Vitek 2 Compact system after 4-5 h, as

previously descried (19).

Effects of different temperatures, pH

value and salinities on bacterial growth

To examine the effects of different environmental

conditions on bacterial growth in the laboratory, a 100-ml conical

flask was used with a volume of 50 ml nutrient broth (Oxoid; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1 ml inoculum at a concentration of

1.5x108 CFU/ml, depending on the 0.5 McFarland standard.

The flasks were incubated at different temperatures (17, 27 and

37˚C) for 24 h and aerated by shaking at 200 rpm to measure the

effects of temperature on V. cholerae and M. morganii

growth (20). The same conditions

were used to examine the effects of various pH values (5, 6, 7, 8,

9 and 10) and different percentages of salinity (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10

and 14%).

Antibiotic susceptibility

The antibiotic susceptibility of V. cholerae

and M. morganii was determined using the disk diffusion

method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards

Institute (CLSI) guidelines (21).

The bacterial strains were examined under two sets of conditions as

follows: i) For V. cholerae, the normal growth conditions

were 37˚C, pH 8.6, and 2% salinity, whereas extreme conditions

included 27˚C, pH 10 and 4% salinity; ii) for M. morganii,

normal growth occurred at 37˚C, pH7, whereas extreme conditions

were set at 27˚C, pH 10, 6% salinity.

The following antibiotics from (Bioanalyse) were

used in the test: Tetracycline (30 µg), piperacillin/tazobactam (10

µg), ampicillin (25 µg), ampicillin (10 µg), colistin (10 µg),

amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (30 µg), amikacin (30 µg); amikacin (10

µg), cefotaxime (30 µg), and piperacillin (100 µg).

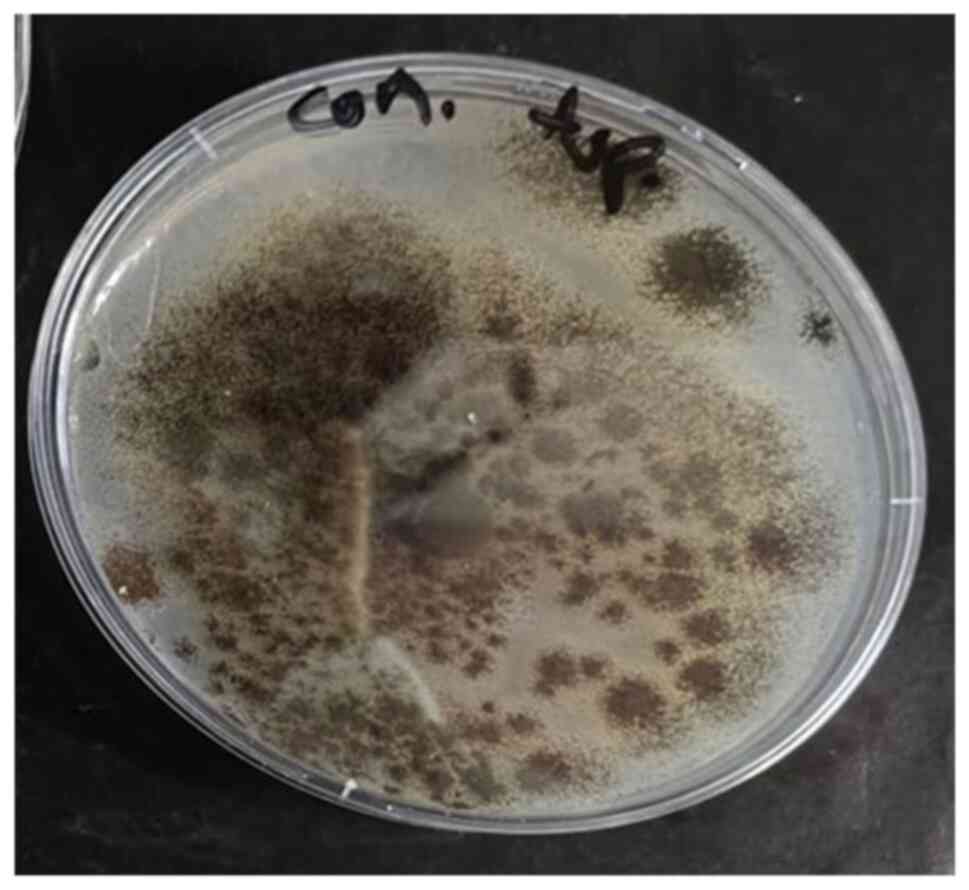

Sample collection and isolation of

fungi

Fungal isolates of A. niger and T.

harzianum were obtained from the aquatic environment in Iraq

(Tigris River). The isolation and cultivation were completed

depending on established protocols (22). A total of 1 ml of each sample was

aseptically inoculated onto sterile 9-cm glass Petri dishes, and

potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium (NEOGENLAB US) was then added

with chloramphenicol (250 mg dissolved in 250 ml distilled water)

to inhibit bacterial contamination. The plates were incubated at

25˚C for 48 h. The growing colonies were sub-cultured on PDA and

incubated for 7 days at 28˚C. Microscopic (Optika Microscopes)

examination and standard taxonomic keys were used to identify

fungal species (23).

Of note, two methods were employed for the

preparation of fungal inocula. First, spore suspensions were

generated by the addition of 10 ml sterile distilled water to

plates containing pure fungal colonies. A total of 5 ml of the

resulting suspension were transferred into sterile glass bottles

containing 95 ml sterile saline solution and were thoroughly mixed.

Spore concentrations were determined using a dilution technique to

achieve the desired inoculum density, as previously described

(23,24). The final spore suspension densities

were 1.7x10³ spores/ml for A. niger and 1.9x10³ spores/ml

for T. harzianum. Alternatively, 7-mm-diameter mycelial

discs were excised from actively growing fungal colonies and used

in downstream applications.

Analysis of the effects of salinity,

acidity and temperature

For the experiments, various concentrations of

sodium chloride were used, including 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14%,

which were added to the culture medium (PDA). Following

sterilization in an autoclave at 121˚C and 1.5 bar pressure, the

media were poured into sterile plastic petri dishes containing 1 ml

chloramphenicol (HiMedia Laboratories, LLC) (250 ppm) and left to

solidify. Subsequently, with a cork piercing a 7-mm size, each

fungal isolate was removed and placed in a dish with a control,

which was a Petri dish containing the antibiotic and culture media

and fungus only. The Petri dishes were incubated at 28˚C for 2-7

days, after which the diameters of the developing colonies and the

growth rates were measured. The previous steps used different pH

values ranging from 5-10 to measure the effect of acidity on fungal

growth. In the temperature experiment, three degrees were used: 17,

27 and 27˚C.

Antifungal resistance of A. niger and

T. harzianum under different growth conditions

In total, five types of antifungals were used from

(HiMedia Laboratories, LLC): Ketoconazole (KT), itraconazole (IT),

amphotericin B (AP), nystatin (NS 50) and miconazole (MIC 50), and

their effects on two fungal isolates (A. niger and T.

harzianum) were investigated. PDA was prepared at different pH

values and NaCl (HIMEDIA/India) concentrations (5 and 10%) and

autoclaved at 121˚C and 1.5 psi. After cooling, the media were

transferred to sterile plastic Petri dishes containing 1 ml spore

suspension, as previously described (25), for each fungal isolate and 1 ml of

the antibiotic, chloramphenicol (HiMedia Laboratories, LLC). They

were allowed to firm up before the antifungal tablets were applied

to each dish and incubated for 2-7 days at 28˚C.

Results

The growth and survival of microorganisms are

influenced by their strains and a range of environmental factors,

such as temperature and humidity, beneficial nutrients, pH, gas

conditions and osmotic pressure (26). In the present study, to determine

the effects of some of these parameters (TM, pH, and salinity) on

different microorganisms, V. cholerae (Fig. 1) and M. morganii (Fig. 2) were selected as bacteria, and

A. niger (Fig. 3) and T.

T. harzianum (Fig. 4) were

used as the fungi. All the microbes were isolated and diagnosed

locally. As shown in Table I, it

was found that V. cholerae could grow and survive at 4%

salinity and M. morganii could grow in 6% NaCl media at 37˚C

for 24 h of incubation; changing the acidity factor did not affect

bacterial growth under the same incubation conditions. It was found

that V. cholerae and M. morganii could survive

temperatures ranging from 17 to 37˚C. When incubated under extreme

growth conditions, V. cholerae thrived at 10 pH/4% NaCl/17˚C

and 10 pH/4% NaCl/27˚C, whereas M. morganii survived at 10

pH/6% NaCl/17˚C and 10 pH/6% NaCl/27˚C.

| Table IImpact of environmental parameters on

the growth of microorganisms. |

Table I

Impact of environmental parameters on

the growth of microorganisms.

| | Growth of

bacteria | Growth of

fungi |

|---|

| Variables Salinity

(NaCl %) | Vibrio

cholerae | Morganella

morganii | Colony

diameter(mm) of Aspergillus niger | Colony diameter

(mm) of Trichoderma harzianum |

|---|

|

0 | + | + | 77.5 | 82.5 |

|

2 | + | + | 75 | 55 |

|

4 | + | + | 60 | 25 |

|

6 | - | + | 50 | 12.5 |

|

8 | - | - | 45 | - |

|

10 | - | - | 30 | - |

|

12 | - | - | - | - |

|

14 | - | - | - | - |

| Acidity (pH) | | | | |

|

5 | + | + | 75 | 78 |

|

6 | + | + | 55 | 78 |

|

7 | + | + | 60 | 78 |

|

8 | + | + | 60 | 79 |

|

9 | + | + | 65 | 79 |

|

10 | + | + | 65 | 79 |

| Temperature,˚C | | | | |

|

17 | + | + | - | - |

|

27 | + | + | 75 | 80 |

|

37 | + | + | - | - |

| pH/NaCl/TM | | | | |

| 10/4%/37˚C | + | + | - | - |

| 10/6%/37˚C | - | + | - | - |

| 10/4%/27˚C | + | + | - | - |

| 10/6%/27˚C | - | + | 30 | - |

| 10/10%/27˚C | - | - | - | - |

| 10/4%/17˚C | + | + | - | - |

| 10/6%/17˚C | - | + | - | - |

The growth diameter of the fungi varied depending on

the growth conditions. As demonstrated in Table I, it was found that A. niger

could live at 10% salinity with a colony diameter of 30 mm, whereas

T. T. harzianum could survive at 6% NaCl with a colony

diameter of 12.5 mm. Both fungi flourished at various acidity

levels, reaching a pH of 10. The effects of temperature on fungal

growth were evident, and the fungi could not tolerate temperatures

of 17 or 37˚C. When different variables were combined, only A.

niger produced a 30-mm colony at pH 10, 6% NaCl, and 27˚C.

Antimicrobial resistance is a critical aspect of the

recent century since the percentage of microorganisms that develop

antibiotic resistance has increased rapidly. The present study used

various types of antibacterial and antifungal agents under various

growth conditions for four types of microorganisms. The findings

presented in Table II

demonstrated how environmental growth conditions can affect

antibiotic resistance and antifungal resistance. V. cholerae

developed resistance to amikacin (10 µg), colistin (10 µg) and

tetracycline (100 µg) under extreme growth conditions, including pH

10, 4% NaCl and 27˚C, while it was intermediately resistant to

amikacin (10 µg), and sensitive to colistin (10 µg) and

tetracycline (100 µg) under normal growth conditions. Notably,

V. cholerae became sensitive to piperacillin (100 µg) after

growth under the same extreme conditions; however, its response to

the other tested antibiotics remained unaltered. The resistance of

M. morganii was largely unaffected by the altered growth

conditions, apart from ampicillin (10 µg), to which it developed

resistance under the same conditions.

| Table IIInfluence of environmental growth

conditions on the antimicrobial resistance profile of selected

microorganisms. |

Table II

Influence of environmental growth

conditions on the antimicrobial resistance profile of selected

microorganisms.

| A, Antibiotics

(antibacterials) |

|---|

| | Vibrio

cholerae | Morganella

morganii |

|---|

| Medication | Concentration | Normal

conditions | Extreme

conditions | Normal

conditions | Extreme

conditions |

|---|

| Amikacin (AK) | 10 µg | I | R | I | I |

| Amikacin (AK) | 30 µg | S | S | S | S |

| Ampicillin

(AMP) | 10 µg | R | R | I | R |

| Ampicillin

(AMP) | 25 µg | R | R | R | R |

|

Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC) | 30 µg | R | R | R | R |

| Cefotaxime

(CTX) | 30 µg | R | R | R | R |

| Colistin (CLM) | 10 µg | S | R | R | R |

| Piperacillin

(PRL) | 100 µg | R | S | S | S |

|

Piperacillin/tazobactam (PIT) | 10 µg | R | R | R | R |

| Tetracycline | 100 µg | S | R | R | R |

| B, Antibiotics

(antifungals) |

| | Aspergillus

niger | Trichoderma

harzianum |

| Medication | Concentration | Normal

conditions | Extreme

conditions | Normal

conditions | Extreme

conditions |

| Ketoconazole

(KT) | 10 µg | S | R | R | R |

| Itraconazole

(IT) | 10 µg | S | I | R | R |

| Amphotericin B

(AP) | 100 µg | S | I | I | R |

| Nystatin (NS) | 50 µg | S | I | S | I |

| Miconozole

(Mic) | 50 µg | S | R | S | R |

As regards antifungal resistance, A. niger

exhibited resistance to ketoconazole (10 µg) and miconazole (50 µg)

under conditions of pH pH 10, 6% salinity and 27˚C; it also

exhibited intermediate resistance to itraconazole (IT) 10 µg,

amphotericin B (AP) 100 µg and nystatin (NS) 50 µg. Moreover, T.

T. harzianum was resistant to amphotericin B (100 µg) and

miconozole (50 µg) under the same conditions.

Discussion

Antibiotics and high or low temperatures are

examples of environmental stressors that can alter the selection

rules that exist in an ecosystem. These selection forces can have

an impact on organism population evolution, as well as their

ability to withstand environmental shocks (27,28).

The present study revealed that bacterial strains exhibited greater

resilience to diverse growth environments than fungal strains. The

observed outcome may be attributed to the ability of bacteria to

synthesize the sugar trehalose in response to different

environmental factors, including low temperatures, oxidative

stress, osmotic shock, acid stress and ethanol exposure (29).

Of note, environmental conditions can affect the

external appearance and internal composition of bacteria. Nhu et

al (30) found that variations

in the acidity of the surrounding environment affected colony

morphology, leading to the production of denser colonies with

irregular edges, their results illustrate how bacterial morphology

changes due to environmental stresses, which can affect their

pathogenicity and identification in changing environmental contexts

(30).

As regards the ability of V. cholerae to

adapt to pH and temperature, the growth characteristics observed in

the present study are consistent with those found in other

published research. According to previous research, the optimal pH

range for growth is between 6 and 9 (31-33),

and the optimal temperature range is between 30 and 37˚C, although

it can survive at 6˚C (34).

However, the results of the present study make a noteworthy

distinction by indicating salinity as a key determinant for the

growth and environmental persistence of V. cholerae. It is

important to note that at sodium chloride concentrations >4%, no

growth was observed. Furthermore, while this observation regarding

the effects of salinity contradicts the findings of Singleton et

al (35) and Huq et al

(31) regarding the growth of the

cholera vibrio strain at higher concentrations of sodium chloride,

it also suggests that strains may differ in their ability to

withstand osmotic pressure; these changes in environmental factors

can influence the conversion of environmental strains to pathogenic

strains and trigger anew outbreak at any time (36). As regards M. morganii, the

results were consistent with the findings of Frith et al

(37) that this bacterium can

tolerate various growth conditions of pH, salinity and temperature;

it was isolated from all sites investigated, despite the different

environmental circumstances.

The antimicrobial susceptibility of the

microorganisms under investigation varied depending on the growth

factors. Generally, at 27˚C, V. cholerae became resistant to

amikacin and tetracycline. These results are in agreement with

those in the study by Yuan et al (38), which reported that from 20 studies,

648 environmental V. cholerae isolates were investigated,

where the weighted pool resistance rate for tetracycline and

amikacin was 14 and 2%, respectively. Parvin et al (39) analyzed the data of tetracycline

resistance from 2000 to 2018 and demonstrated that 100% of V.

cholerae strains were susceptible to tetracycline between 2000

and 2004. Thereafter, a decline in susceptibility rate was

observed, decreasing to 6% between 2012 and 2017, then increasing

again to 76% in 2018(39).

These medications (amikacin and tetracycline), which

bind to ribosomes, have been demonstrated to either induce a

cold-shock-like pattern of protein production or to interact with

other stressors in a manner that is comparable to cold temperatures

in Escherichia coli <22-27˚C. Given that one of the main

effects of cold stress is translational block, the cellular

machinery involved in response to these antibiotics may overlap

with that involved in cold shock (40). When bacteria are repeatedly exposed

to various growth environments, cross-tolerance may arise. This

occurs when early exposure to a stressor leads to tolerance to a

different type of stress. A previous study suggested that the

mechanisms for tolerance may be shared among antibiotics that

target similar processes rather than through generalized cell

dormancy, creating multidrug-resistant bacteria (34). These shared tolerance mechanisms

can also adapt to various types of stressors (such as temperature,

pressure, or pH) (34).

After being subjected to a range of growth

conditions, V. cholerae becomes resistant to colistin.

Colistin is a last-resort antibiotic used to treat serious

infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria (41). According to the study by Sharif

et al (42), V.

cholerae is typically susceptible to this antibiotic, with 59%

of the 53 isolates being susceptible and 26% being resistant. As

the resistance gene (mcr) is carried on a plasmid that may be

transmitted from humans to animals, acquiring resistance to this

antibiotic poses a new threat to human life by decreasing the

effectiveness of eradicating harmful Gram-negative bacteria

(41).

Drug resistance in Enterobacteriaceae pathogens

(V. cholerae and M. morganii) is largely caused by

the frequent transfer of extrachromosomal mobile genetic elements

from nearby or distantly related bacterial species, even though

chromosomal alterations can also play a role in antimicrobial

resistance. The primary carriers of genetic characteristics

expressing antimicrobial resistance function found in the isolates

of enteric pathogens include plasmids, insertion sequences,

superintegrons, integrating conjugative elements and transposable

elements (43,44).

Antifungal resistance develops as a result of the

changes that affect how the antifungal interacts with its target

directly or indirectly. For example, mutations in genes encoding

lanosterol demethylase (ketoconazole and miconazole) can cause

changes in the binding site of the target that ultimately lead to

resistance. Increased drug efflux activity for intracellular

medications, such as azoles can increased target availability or

modifications to the effective drug concentration can also lead to

resistance (45,46). Polyene antifungals, such as

amphotericin B and nystatin target ergosterol, an essential

membrane component, rather than an essential cellular enzyme. This

distinct mode of action could potentially account for the

infrequent incidence of polyene resistance in fungi. However,

changing the sterol makeup of the plasma membrane is the most

well-known method of achieving polyene resistance (47). The findings of the present study

may represent a basis for future investigations into the effects of

climate factors on the phenotypic and genetic levels. Genetic

mutations are widely known as key drivers of novel epidemics and

diseases. Thence, it is recommended that following studies focus on

the elucidation of the genetic impacts of these factors on

microorganisms, which is essential for advancing the understanding

of pathogenic and disease evolution.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

microbial growth and antimicrobial resistant are affected by

changes in climate and climate-related factors, such as

temperatures, salinity and environmental pH. These changes may

contribute to the emergence of new strains harboring multidrug

resistance genes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SAK was involved in the conception of the study, in

the bacteriological work, in the analysis of the results, and in

the writing of the manuscript. SHO was involved the fungal work,

and in the writing of the fungal-related sections of the

manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. SAK and SHO confirm authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

SAK (PhD in Biotechnology; Masters degree in

Microbiology (Bacteriology) ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4346-306X], resides and

works in Baghdad, Iraq under the scientific research commission as

a scientific researcher. SHO (Masters degree in Biology; ORCID ID:

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-2104-0990) resides and

works in Baghdad, Iraq under the scientific research

commission.

References

|

1

|

Cavicchioli R, Ripple WJ, Timmis KN, Azam

F, Bakken LR, Baylis M, Behrenfeld MJ, Boetius A, Boyd PW, Classen

AT, et al: 2019: Scientists' warning to humanity: microorganisms

and climate change. Nat Rev Microbiol. 17:569–586. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mora C, McKenzie T, Gaw IM, Dean JM, von

Hammerstein H, Knudson TA, Setter RO, Smith CZ, Webster KM, Patz JA

and Franklin EC: Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can

be aggravated by climate change. Nat Clim Chang. 12:869–875.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gross M: Permafrost thaw releases

problems. Curr Biol. 29:R39–R41. 2019.

|

|

4

|

Guzman Herrador BR, De Blasio BF,

MacDonald E, Nichols G, Sudre B, Vold L, Semenza JC and Nygård K:

Analytical studies assessing the association between extreme

precipitation or temperature and drinking water-related waterborne

infections: A review. Environ Health. 14(29)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sobral MFF, Duarte GB, da Penha Sobral

AIG, Marinho MLM and de Souza Melo A: Association between climate

variables and global transmission oF SARS-CoV-2. Sci Total Environ.

729(138997)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Chua PLC, Huber V, Ng CFS, Seposo XT,

Madaniyazi L, Hales S, Woodward A and Hashizume M: Global

projections of temperature-attributable mortality due to enteric

infections: a modelling study. Lancet Planet Health. 5:e436–e445.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Magnano San Lio R, Favara G, Maugeri A,

Barchitta M and Agodi A: how antimicrobial resistance is linked to

climate change: An global challenges overview of two intertwined.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 20(1681)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Sampaio A, Silva V, Poeta P and

Aonofriesei F: Vibrio spp.: Life strategies, ecology, and risks in

a changing environment. Diversity. 14(97)2022.

|

|

9

|

Li H, Chen Z, Ning Q, Zong F and Wang H:

Isolation and identification of morganella morganii from rhesus

monkey (Macaca mulatta) in China. Vet Sci. 11(223)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liu H, Zhu J, Hu Q and Rao X: Morganella

morganii, a non-negligent opportunistic pathogen. Int J Infect Dis.

50:10–17. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wheeler KA, Hurdman BF and Pitt JI:

Influence of pH on the growth of some toxigenic species of

Aspergillus, Penicillium and Fusarium. Int J Food Microbiol.

12:141–149. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Rhouma A, Salem IB, M'hamdi M and

Boughalleb-M'Hamdi N: Relationship study among soils

physico-chemical properties and Monosporascus cannonballus

ascospores densities for cucurbit fields in Tunisia. Eur J Plant

Pathol. 153:65–78. 2019.

|

|

13

|

Abdel-Hadi A and Magan N: Influence of

physiological factors on growth, sporulation and ochratoxin A/B

production of the new Aspergillus ochraceus grouping. World

Mycotoxin J. 2:429–434. 2009.

|

|

14

|

Cao C, Li R, Wan Z, Liu W, Wang X, Qiao J,

Wang D, Bulmer G and Calderone R: The effects of temperature, pH,

and salinity on the growth and dimorphism of Penicillium marneffei.

Med Mycol. 45:401–407. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Abubakar A, Suberu HA, Bello IM,

Abdulkadir R, Daudu OA and Lateef AA: Effect of pH on mycelial

growth and sporulation of Aspergillus parasiticus. J Plant Sci.

1:64–67. 2013.

|

|

16

|

Druzhinina IS, Kopchinskiy AG, Komoń M,

Bissett J, Szakacs G and Kubicek CP: An oligonucleotide barcode for

species identification in Trichoderma and Hypocrea. Fungal Genet

Biol. 42:813–828. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jones EG, Suetrong S, Sakayaroj J, Bahkali

AH, Abdel-Wahab MA, Boekhout T and Pang KL: Classification of

marine ascomycota, basidiomycota, blastocladiomycota and

chytridiomycota. In: Fungal Diversity. Vol 73. Springer, New York,

NY, pp1-72, 2015.

|

|

18

|

Daboul J, Weghorst L, DeAngelis C, Plecha

SC, Saul-McBeth J and Matson JS: Characterization of Vibrio

cholerae isolates from freshwater sources in northwest Ohio. PLoS

One. 15(e0238438)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Pincus DH: Microbial identification using

the bioMérieux Vitek® 2 system. In: Encyclopedia of Rapid

Microbiological Methods. Parenteral Drug Association, Bethesda, MD,

pp1-32, 2006.

|

|

20

|

Silva APRD, Longhi DA, Dalcanton F and

Aragão GMFD: Modelling the growth of lactic acid bacteria at

different temperatures. Braz arch biol Technol.

61(e18160159)2018.

|

|

21

|

CLSI: Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution

and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or

Fastidious Bacteria. 3rd edition. Clinical and Laboratory Standards

Institute, Wayne, PA, 2015.

|

|

22

|

Romero MC, Hammer E, Hanschke R, Arambarri

AM and Schauer F: Biotransformation of biphenyl by filamentous

fungus Talaromyces helicus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol.

21:101–106. 2005.

|

|

23

|

Webster J (ed): Introduction to Fungi.

Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, p669, 1980.

|

|

24

|

Moor-Landecker E: Fundamentals of Fungi.

Prentice-Hall India, New Delhi, pp265-277, 1972.

|

|

25

|

CLSI: Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion

Susceptibility Testing of Nondermatophyte Filamentous Fungi.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA, 2010.

|

|

26

|

Qiu Y, Zhou Y, Chang Y, Liang X, Zhang H,

Lin X, Qing K, Zhou X and Luo Z: The effects of ventilation,

humidity, and temperature on bacterial growth and bacterial genera

distribution. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

19(15345)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Buckley LB and Huey RB: How extreme

temperatures impact organisms and the evolution of their thermal

tolerance. Integr Comp Biol. 56:98–109. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Donhauser J, Niklaus PA, Rousk J, Larose C

and Frey B: Temperatures beyond the community optimum promote the

dominance of heat-adapted, fast growing and stress resistant

bacteria in alpine soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 148(107873)2020.

|

|

29

|

Rodríguez-Verdugo A, Lozano-Huntelman N,

Cruz-Loya M, Savage V and Yeh P: Compounding effects of climate

warming and antibiotic resistance. IScience.

23(101024)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Nhu NT, Wang HJ and Dufour YS: Acidic pH

reduces Vibrio cholerae motility in mucus by weakening flagellar

motor torque. bioRxiv: Dec 10, 2019 (Epub ahead of print). doi:

https://doi.org/10.1101/871475.

|

|

31

|

Huq A, West PA, Small EB, Huq MI and

Colwell RR: Influence of water temperature, salinity, and pH on

survival and growth of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae serovar O1

associated with live copepods in laboratory microcosms. Appl

Environ Microbiol. 48:420–424. 1984.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Nhu NTQ, Lee JS, Wang HJ and Dufour YS:

Alkaline pH increases swimming speed and facilitates mucus

penetration for Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 203:e00607–20.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kostiuk B, Becker ME, Churaman CN, Black

JJ, Payne SM, Pukatzki S and Koestler BJ: Vibrio cholerae alkalizes

its environment via citrate metabolism to inhibit enteric growth in

vitro. Microbiol Spectr. 11(e0491722)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

McCarthy SA: Effects of temperature and

salinity on survival of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 in seawater.

Microb Ecol. 31:167–175. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Singleton FL, Attwell R, Jangi S and

Colwell RR: Effects of temperature and salinity on Vibrio cholerae

growth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 44:1047–1058. 1982.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Montilla R, Chowdhury MA, Huq A, Xu B and

Colwell RR: Serogroup conversion of Vibrio cholerae non-O1 to

Vibrio cholerae O1: Effect of growth state of cells, temperature,

and salinity. Can J Microbiol. 42:87–93. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Frith A, Hayes-Mims M, Carmichael R and

Björnsdóttir-Butler K: Effects of environmental and water quality

variables on histamine-producing bacteria concentration and species

in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Microbiol Spectr.

11(e0472022)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Yuan XH, Li YM, Vaziri AZ, Kaviar VH, Jin

Y, Jin Y, Maleki A, Omidi N and Kouhsari E: Global status of

antimicrobial resistance among environmental isolates of Vibrio

cholerae O1/O139: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob

Resist Infect Control. 11(62)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Parvin I, Shahunja KM, Khan SH, Alam T,

Shahrin L, Ackhter MM, Sarmin M, Dash S, Rahman MW, Shahid AS, et

al: Changing susceptibility pattern of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates

to commonly used antibiotics in the largest diarrheal disease

hospital in Bangladesh during 2000-2018. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

103:652–658. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Cruz-Loya M, Kang TM, Lozano NA, Watanabe

R, Tekin E, Damoiseaux R, Savage VM and Yeh PJ: Stressor

interaction networks suggest antibiotic resistance co-opted from

stress responses to temperature. ISME J. 13:12–23. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Thaotumpitak V, Sripradite J, Atwill ER

and Jeamsripong S: Emergence of colistin resistance and

characterization of antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors

of Aeromonas hydrophila, Salmonella spp., and Vibrio cholerae

isolated from hybrid red tilapia cage culture. PeerJ.

11(e14896)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Sharif N, Ahmed SN, Khandaker S, Monifa

NH, Abusharha A, Vargas DLR, Díez IT, Castilla AGK, Talukder AA,

Parvez AK and Dey SK: Multidrug resistance pattern and molecular

epidemiology of pathogens among children with diarrhea in

Bangladesh, 2019-2021. Sci Rep. 13(13975)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Das B, Verma J, Kumar P, Ghosh A and

Ramamurthy T: Antibiotic resistance in Vibrio cholerae:

Understanding the ecology of resistance genes and mechanisms.

Vaccine. 38 (Suppl 1):A83–A92. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Luo XW, Liu PY, Miao QQ, Han RJ, Wu H, Liu

JH, He DD and Hu GZ: Multidrug resistance genes carried by a novel

transposon Tn 7376 and a genomic island named MMGI-4 in a

pathogenic morganella morganii isolate. Microbiology Spectrum.

10:e00265–22. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Robbins N, Caplan T and Cowen LE:

Molecular evolution of antifungal drug resistance. Annu Rev

Microbiol. 71:753–775. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Osset-Trénor P, Pascual-Ahuir A and Proft

M: Fungal drug response and antimicrobial resistance. J Fungi

(Basel). 9(565)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Sanglard D, Ischer F, Parkinson T,

Falconer D and Bille J: Candida albicans mutations in the

ergosterol biosynthetic pathway and resistance to several

antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 47:2404–2412.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|