Introduction

The majority of types of cancer, including breast

cancer, result from genetic and epigenetic alterations that disrupt

normal cellular signaling, leading to uncontrolled proliferation

and survival (1-3).

Key pathways involved in breast cancer progression include the

phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian

target of rapamycin (mTOR) and mitogen-activated protein kinase

(MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling

cascades, which not only drive tumorigenesis, but also contribute

to chemotherapeutic resistance (4,5).

These pathways regulate cell cycle progression by stimulating

cyclin D1, a critical protein that promotes cell division (6). The cell cycle, which consists of four

phases (G0/G1, S, G2 and M) (7),

is regulated by cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) that

form cyclin/CDK complexes (8).

This process is negatively regulated by CDK inhibitors, such as

p21, which suppress cyclin/CDK activity (9). The dysregulation of p21 or the

overexpression of cyclins and CDKs can lead to uncontrolled cell

proliferation, a hallmark of cancer (8). Notably, cyclin D1 and CDK4/6 are

overexpressed in breast cancer, along with elevated levels of the

proliferation marker, Ki-67(10).

Ki-67 levels rapidly decrease during cancer cell apoptosis

following treatment with chemotherapy (11). However, the adverse effects of

chemotherapy on normal cells often limit its therapeutic success

(12).

Natural products are increasingly being explored for

their anticancer potential due to their fewer adverse effects.

Sulfated galactan (SG), a polysaccharide isolated from the red

seaweed, Gracilaria fisheri (G. fisheri), has been

shown to induce cell cycle arrest in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) by

downregulating cyclin and CDK expression, while upregulating tumor

suppressors, such as p21 and p53(13). It has also been reported to

suppress CCA cell invasion and migration (14). Additionally, chemical

modifications, such as reducing molecular weight and substituting

functional groups, have been found to enhance the anticancer

properties of polysaccharides (15). In a recent study, modified SG from

G. fisheri with low molecular weight (LSG), supplemented

with an octanoyl ester (LSGO), was found to exhibit an enhanced

wound healing activity (16).

However, the effects of SG and its derivatives, including LSG and

LSGO, on breast cancer remain unexplored. Therefore, the present

study aimed to evaluate the anticancer activities of SG and its

derivatives in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. The mechanisms by

which SG and its derivatives affect MCF-7 cell proliferation, cell

cycle regulation, protein expression and mRNA expression were also

investigated.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

Human mammary gland epithelial adenocarcinoma

(MCF-7; cat. no. HTB-22) and normal fibroblast (L929; cat. no.

CCL-1) cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture

Collection (ATCC). MCF-7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified

Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

containing L-glutamine, pyridoxine hydrochloride and sodium

bicarbonate (NaHCO3), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

antibiotic-antimycotic (penicillin/streptomycin; Invitrogen, Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). L929 cells were cultured in minimum

essential medium (MEM; Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

which contains L-glutamine and phenol red, supplemented with 10%

FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. Both MCF-7 and L929 cells were

maintained under standard conditions at 37˚C in a humidified

atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Evaluation of the cytotoxicity of SG

and its derivatives in MCF-7 and L929 cells

SG, LSG and LSGO were prepared as previously

described by Rudtanatip et al (16). MTT assay was used to assess the

cytotoxicity of SG, LSG and LSGO in MCF-7 and L929 cell cultures.

MCF-7 and L929 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density

of 2x104 cells/well and allowed to attach for 24 h under

standard incubator conditions. The cells were then treated with

various concentrations of SG, LSG and LSGO (0, 125, 250, 500 and

1,000 µg/ml), as well as paclitaxel (PTX; Intaxel® 6

mg/ml paclitaxel injection, Fresenius Kabi) and gemcitabine (GEM;

gemcitabine hydrochloride, Supelco, MilliporeSigma) (0, 0.2, 0.4,

0.6, 0.8 and 1 µg/ml) for 48 h. PTX and GEM served as the positive

controls, while untreated cells were used as the normal control.

Following the treatment period, 20 µl MTT solution (5 mg/ml;

MilliporeSigma) were added to each well and incubated for 3 h at

37˚C. The medium was then removed, and 100 µl dimethyl sulfoxide

(DMSO; RCI Labscan™ Limited) were added to dissolve the purple

formazan crystals. The plate was shaken on a microplate shaker for

20 min, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a

microplate reader (Varioskan® LUX, cat. no. N16044;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The results were reported as

IC50 values, as previously described (13). The concentrations of SG and its

derivatives, as well as those of PTX and GEM used in the present

study were based on a previous study by the authors and other

relevant studies (16-18).

Evaluation of cell morphology

The morphology of the MCF-7 and L929 cells treated

with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO was also examined. The MCF-7 and

L929 cells (6x104 cells/well) were cultured in a 24-well

plate for 24 h, and the cells were divided into six groups as

follows: i) The normal control (NC), no treatment; ii) PTX, cells

were treated with 0.5 µg/ml PTX; iii) GEM, cells were treated with

0.5 µg/ml GEM; iv) SG, cells were treated with 500 µg/ml SG; v)

LSG, cells were treated with 500 µg/ml LSG; and vi) LSGO, cells

were treated with 500 µg/ml LSGO. The cells were treated with 2 ml

of the respective solution and incubated for 48 h at 37˚C before

observing cell morphology under a Nikon ECLIPSE TS100 inverted

microscope (Nikon Corporation). Cell counts were analyzed in three

randomly selected fields at x200 magnification using ImageJ

software version 1.54g (National Institutes of Health).

A concentration of 500 µg/ml was selected for use in

subsequent assays, as both 500 and 1,000 µg/ml exerted comparable

moderate effects on cell viability without reaching the

IC50 value. The results of MTT assay confirmed that 500

µg/ml produced similar outcomes to 1,000 µg/ml, supporting its use

in further experiments.

Evaluation of the anti-proliferative

effect of SG and its derivatives on MCF-7 cells

The results of cytotoxicity assay indicated that

although SG and its derivatives were not markedly cytotoxic to the

MCF-7 cells, they reduced cell numbers by 20% compared to the

control. This suggests that SG and its derivatives may inhibit

MCF-7 cell proliferation, as previously reported (13). The anti-proliferative effects of SG

and its derivatives were further investigated.

Experimental design

The MCF-7 cells were cultured and divided into six

groups as follows: i) NC, no treatment; ii) PTX, cells were treated

with 0.5 µg/ml paclitaxel; iii) GEM, cells were treated with 0.5

µg/ml GEM; iv) SG, cells were treated with 500 µg/ml SG; v) LSG,

cells were treated with 500 µg/ml LSG; and vi) LSGO, cells were

treated with 500 µg/ml LSGO.

Hoechst/propidium iodide (PI) dual

staining

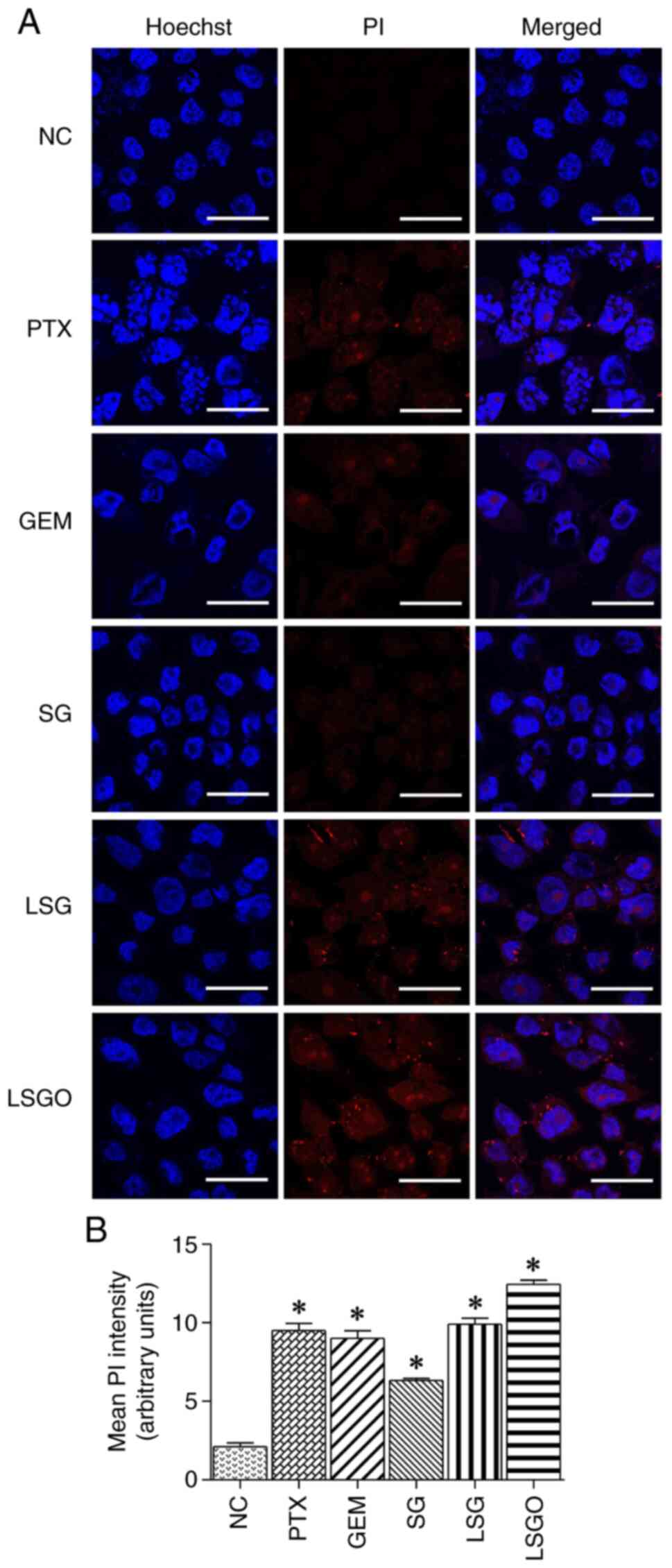

The cytotoxic effects of SG and its derivatives were

further confirmed using Hoechst/PI dual staining. The MCF-7 cells

were plated on round coverslips in a 24-well plate at a density of

6x104 cells/well in DMEM and incubated for 24 h at 37˚C.

Following incubation, the cells were treated with the respective

solution for 48 h. The cells were then washed with PBS and stained

with Hoechst (Merck KGaA) and PI (BioChemica, PanReac AppliChem) at

a 1:1 ratio for 30 min at room temperature. After staining, the

cells were washed three times with PBS in the dark. The coverslips

containing the stained cells were then mounted on glass slides with

a droplet of anti-fade solution. Finally, the cells were observed

under a confocal microscope (ZEISS LSM 800, Carl Zeiss AG), as

previously described (16). The

laser intensity wavelengths were 405 nm with a pinhole size of 1.18

AU/45 µm for Hoechst staining and 561 nm with a pinhole size of

0.90 AU/47 µm for PI staining. PI fluorescent intensity was

measured in three randomly selected fields at a x200 total

magnification using ImageJ software version 1.54g (National

Institutes of Health).

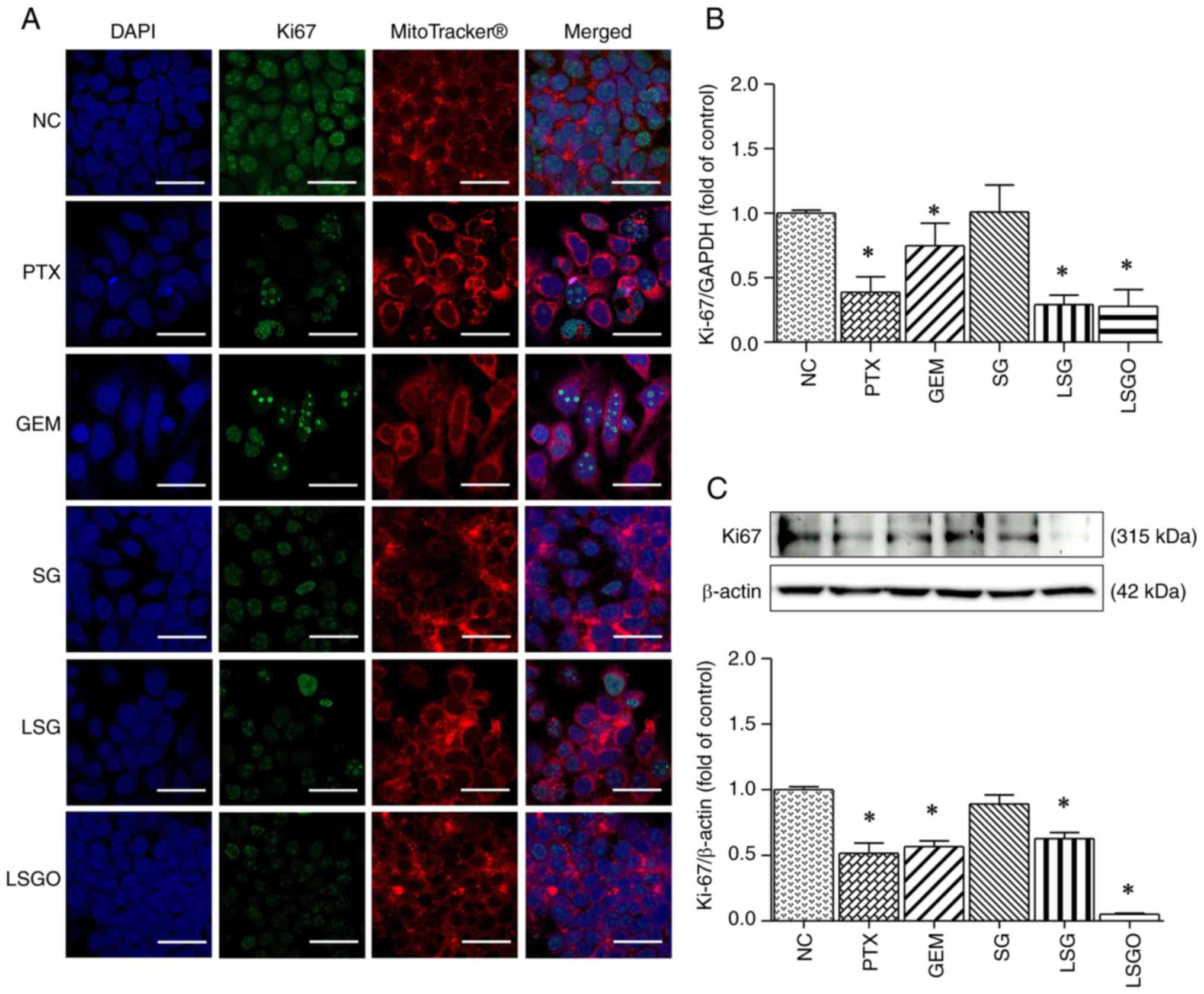

Immunofluorescence staining of cell

proliferation using the Ki-67 biomarker

The MCF-7 cells seeded on round coverslips in a

24-well plate were treated with the respective solution for 48 h.

Following treatment, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

in 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 15 min and were then

washed three times with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were blocked

with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Capricorn Scientific GmbH) for

30 min at room temperature. After blocking, the cells were washed

with PBS and incubated overnight at 4˚C with a primary antibody

specific to mouse anti-Ki-67 (dilution 1:500; cat no. 14569982;

Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The following day, the

cells were incubated with a fluorescent-labeled secondary antibody

(goat anti-mouse FITC-conjugated; dilution 1:500; cat no. AP308F;

Merck Millipore) for 1 h, at room temperature in the dark.

Following incubation, the cells were washed with PBS in the dark

and counterstained with Cell Mask™ Deep Red plasma membrane stain

(dilution 1:500; cat no. C10066; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 20 min at room temperature. A total of 5 µl

of antifade solution conjugated with DAPI dye (ProLong™ Diamond

Antifade Mountant with DAPI, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) was then added to a glass slide. The round coverslips

containing the cells were then placed on the glass slide with a

droplet of antifade solution. Finally, the fluorescence intensity

of Ki-67 was observed using a confocal microscope (ZEISS LSM 800,

Carl Zeiss AG), as previously described (19).

Evaluation of cell cycle arrest using

flow cytometry

A flow cytometry cell cycle arrest assay was used to

evaluate the mechanisms of action of SG and its derivatives. The

MCF-7 cells were seeded in a six-well plate at a density of

1.5x105 cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight. The

cells were then treated with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO solutions

for 48 h. Following treatment, all adherent cells were harvested by

trypsinization, transferred to sterile Eppendorf tubes, and

centrifuged at 2,795 x g at 4˚C for 5 min to pellet the cells. The

cell pellets were washed three times with cold PBS and centrifuged

at 2,795 x g at 4˚C for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and

ice-cold 70% ethanol was added to fix the cells. The pellets were

then resuspended to obtain a single-cell suspension and incubated

at -20˚C for 1 week. Following incubation, the cell pellets were

washed three times with PBS, and the supernatant was removed.

Nuclei were stained with PI/RNase staining solution (FxCycle™

PI/RNase, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and incubated for 40 min

in the dark at room temperature. Flow cytometric analysis was

performed using a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (Model FACSCanto II,

BD Biosciences). The percentage of cells in each phase of the cell

cycle was then analyzed (20).

Analysis of mRNA expression using

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

TRIzol reagent (200 µl; MilliporeSigma) was used for

RNA extraction. RNA purity and concentration were determined by

measuring the absorbance ratio at 260/280 nm using a NanoDrop 2000

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Complementary

DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 µg RNA using the RevertAid First

Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) through

incubation at 42˚C for 60 min, followed by heating at 70˚C for 5

min. Subsequently, mRNA expression was analyzed using qPCR with the

synthesized cDNA and PCR Master Mix (Molecular Biology, Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and forward and reverse primers. The

cycling conditions were as follows: 50˚C for 2 min, 95˚C for 10

min, followed by 40 cycles of 95˚C for 15 sec, 60˚C for 30 sec and

72˚C for 30 sec. Data quantification calculated using the

2-ΔΔCq method (21) was

performed using the Bio-Rad CFX Maestro software (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The primers used in the present study included

Ki-67, PI3K, AKT, mTOR, cyclin D1, CDK4, cyclin A, CDK2, p21, ERK

1/2 and GAPDH (Bionics). Forward and reverse primer sequences were

designed using NCBI/Primer-Blast, and their sequences are provided

in Table I.

| Table INucleotide sequences of specific

primers used for mRNA expression. |

Table I

Nucleotide sequences of specific

primers used for mRNA expression.

| Gene names | Primers | Nucleotide

sequences (5' to 3') |

|---|

| Ki-67 | Forward |

GAAAGAGTGGCAACCTGCCTTC |

| | Reverse |

GCACCAAGTTTTACTACATCTGCC |

| PI3K | Forward |

AACACAGAAGACCAATACTC |

| | Reverse |

TTCGCCATCTACCACTAC |

| AKT | Forward |

TCTATGGCGCTGAGATTGTG |

| | Reverse |

CTTAATGTGCCCGTCCTTGT |

| mTOR | Forward |

GCTTGATTTGGTTCCCAGGAC |

| | Reverse |

GTGCTGAGTTTGCTGTACCCA |

| Cyclin D1 | Forward |

GCATGTTCGTGGCCTCTAAG |

| | Reverse |

CGTGTTTGCGGATGATCTGT |

| CDK4 | Forward |

TGAGGGTCTCCCTTGATCTGAG |

| | Reverse |

AGGGATACATCTCGAGGCCA |

| p21 | Reverse |

GCTTCATGCCAGCTACTTCC |

| | Forward |

CCCTTCAAAGTGCCATCTGT |

| Cyclin A | Forward |

GTCAGAGAGGGGATGGCAT |

| | Reverse |

CCAGTCCACCAGAATCGTG |

| CDK2 | Forward |

GAATCTCCAGGGAATAGGGC |

| | Reverse |

CTGAAATCCTCCTGGGCTG |

| ERK1/2 | Forward |

TGGCAAGCACTACCTGGATCAG |

| | Reverse |

GCAGAGACTGTAGGTAGTTTCGG |

| GAPDH | Reverse |

GGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACG |

| | Forward |

CTCGCTCCTGGAAGATGGTG |

Analysis of protein expression

The expression of proteins involved in cell

proliferation was determined after the MCF-7 cells were treated for

48 h using western blot analysis. Cells were harvested for protein

extraction. The protein concentration was quantified using a

NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

and 50 µg protein samples were separated by electrophoresis using

12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(SDS-PAGE). The separated proteins were then transferred onto a

nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham™ Protran™ Premium 0.45 µm NC

nitrocellulose western blotting membranes), which was blocked with

4% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Each membrane was probed with

primary antibodies (dilution 1:1,000) against mouse anti-Ki-67

(cat. no. 14569982; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

rabbit anti-PI3K (cat. no. 4255S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.),

rabbit anti-phosphorylated (p)-AKT (cat. no. sc-135651; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-AKT (cat. no. 8596S; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), rabbit anti-p-mTOR (cat. no. 5536S;

Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), rabbit anti-mTOR (cat. no. 2972S;

Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), mouse anti-cyclin D1 (cat. no.

AHF0082; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), mouse

anti-CDK4 (cat. no. AHZ0202; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), rabbit anti-p21 (cat. no. E2R7A; Cell Signaling Technology

Inc.), rabbit anti-cyclin A (cat. no. AF0142; Affinity

Biosciences), rabbit anti-CDK2 (cat. no. MA5-17052; Invitrogen,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), mouse anti-ERK1/2 (cat. no. 9102S;

Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) and rabbit anti-β-actin (cat. no.

AF7018; Affinity Biosciences) and incubated overnight at 4˚C. The

membranes were then incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated

with horseradish peroxidase (dilution 1:2,000; cat. no. 31460 for

anti-rabbit antibody and cat. no. 626520 for anti-mouse antibody;

Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature for

1 h. Following incubation, the membranes were washed with

Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBS-T) solution, and

immunoreactivity was enhanced using a chemiluminescence ECL-Western

blotting substrate kit (Clarity™ Western ECL substrate, Bio-Rad,

USA). Finally, protein bands were detected using the ChemiDoc Touch

imaging system (Amersham™ ImageQuant™ 800 biomolecular imager,

Cytiva). Relative protein expression was quantified using ImageJ

software version 1.32j (National Institutes of Health) with band

intensities standardized to β-actin (22).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and

data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was

conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple

comparisons test using GraphPad Prism software version 5

(Dotmatics).

Results

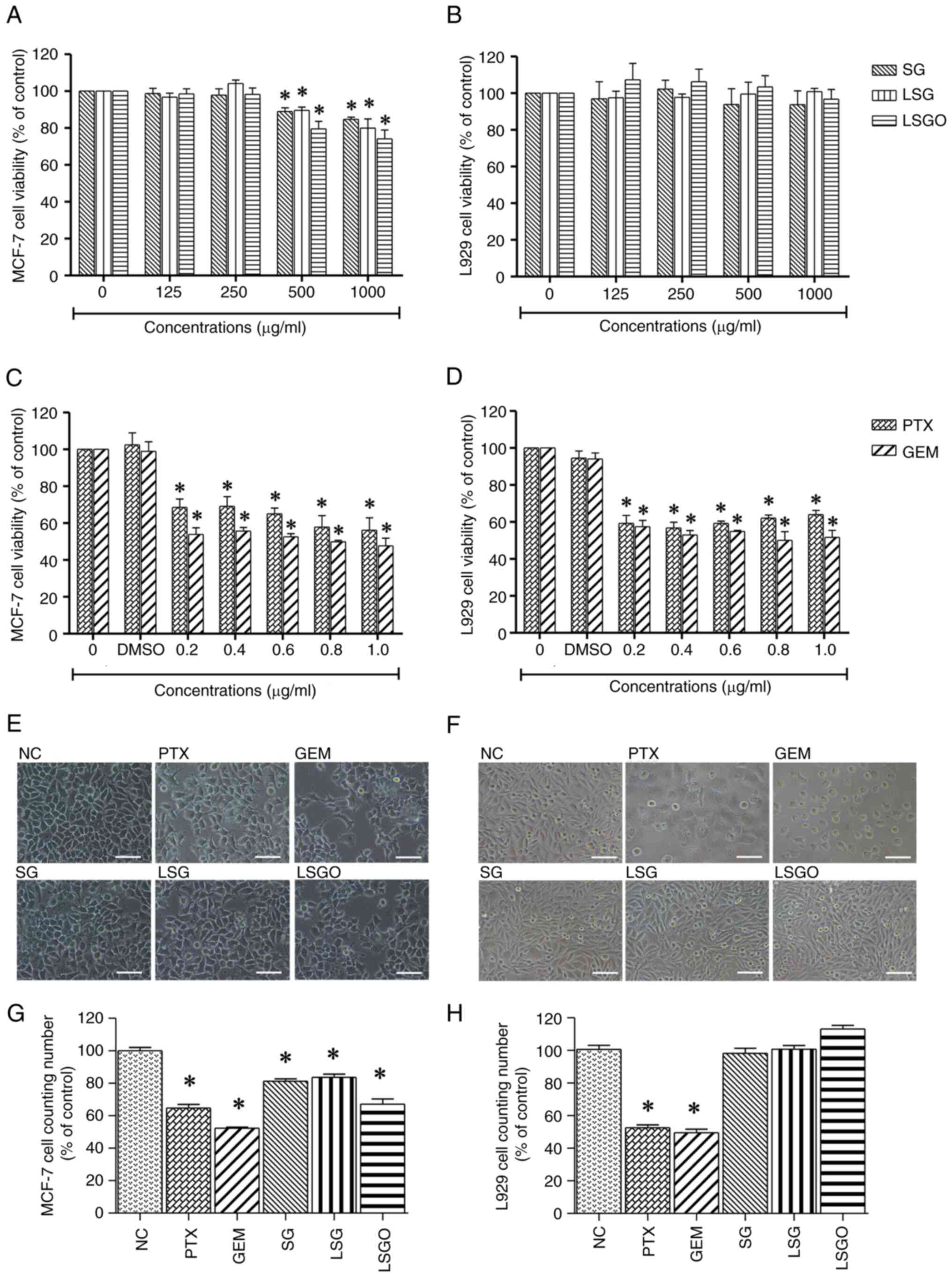

Effects of SG and its derivatives on

the viability of MCF-7 and L929 cells

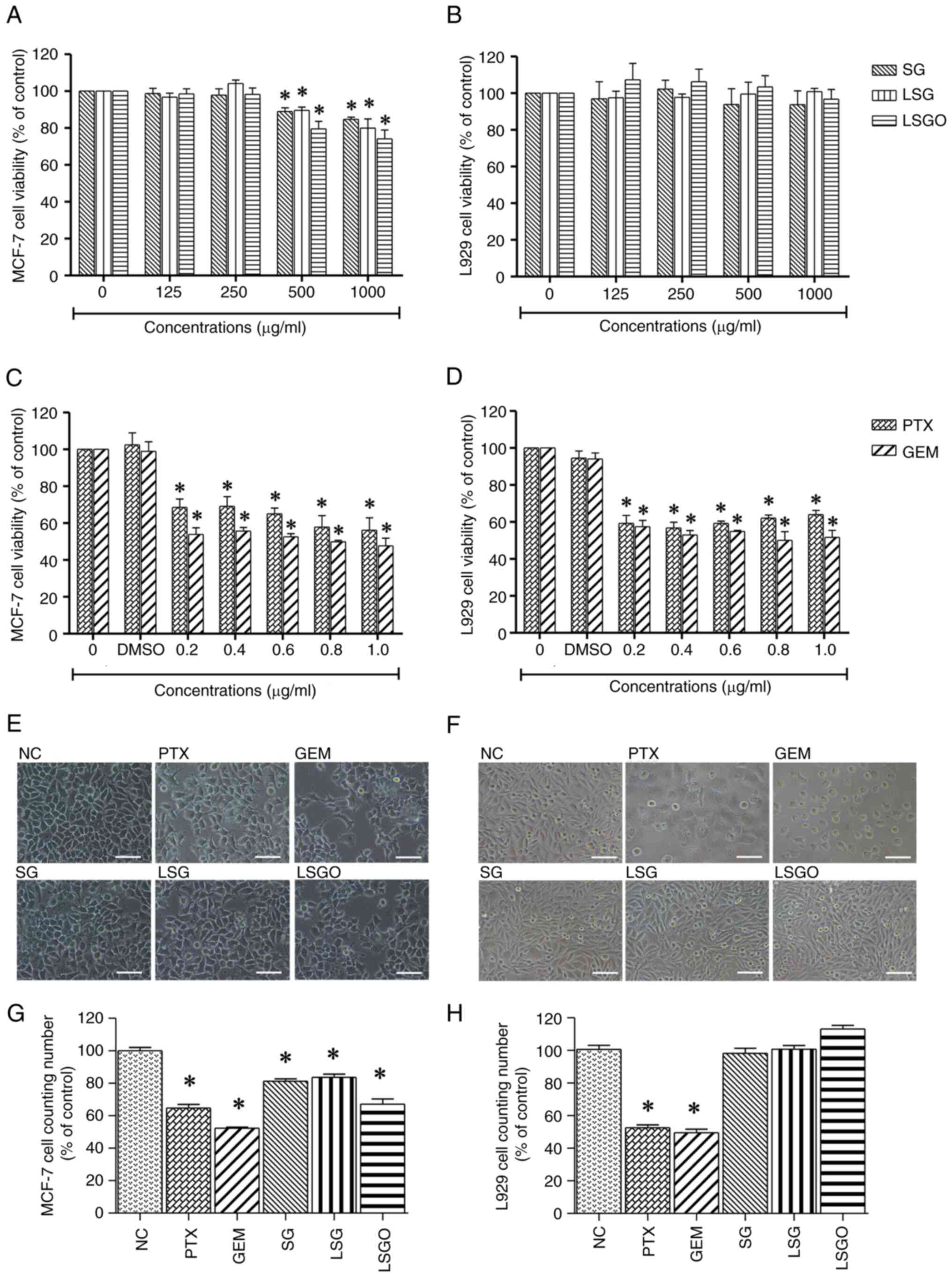

The cytotoxic effects of SG and its derivatives on

MCF-7 breast cancer and L929 normal fibroblast cells were evaluated

and expressed as a percentage of the control following 48 h of

exposure at concentrations of 125, 250, 500 and 1,000 µg/ml. The

results revealed that at 500 and 1,000 µg/ml, MCF-7 cell viability

significantly decreased from 100 to 80% (Fig. 1A), while L929 cell viability

exhibited no significant differences between the groups (Fig. 1B). However, the IC50

values of SG, LSG and LSGO in the MCF-7 cells were calculated to be

3,027, 2,416 and 1,757 µg/ml, respectively. Additionally, the

anticancer drugs, PTX and GEM, were used as positive controls to

compare the cytotoxic effects. PTX and GEM significantly reduced

the viabilities of both the MCF-7 and L929 cells, with low

IC50 values of 0.54 and 0.57 µg/ml, respectively

(Fig. 1C and D). Cell morphology observed under a phase

contrast microscope revealed that the MCF-7 and L929 cells treated

with PTX and GEM (Fig. 1E and

F) exhibited characteristic

cellular changes, including shrinkage, membrane bleb formation and

the loss of normal shape. Notably, the L929 cells treated with SG

and its derivatives did not exhibit any noticeable changes compared

to the control. Moreover, the quantitative cell counts of MCF-7 and

L929 cells following treatment, shown in Fig. 1G and H, were consistent with the results of MTT

assay. These findings suggest a selective effect of the compounds

on cancer cells without affecting normal cells.

| Figure 1Effects of PTX and GEM (at

concentrations of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 and 1.0 µg/ml) and SG, LSG and

LSGO (at concentrations of 125, 250 500, and 1,000 µg/ml) on the

viability of MCF-7 breast cancer cells and L929 normal fibroblast

cells, as assessed using MTT assay. (A) Viability of MCF-7 cells

treated with SG, LSG and LSGO. (B) Viability of L929 cells treated

with SG, LSG and LSGO. (C) Viability of MCF-7 cells treated with

PTX and GEM. (D) Viability of L929 cells treated with PTX and GEM.

(E) Phase-contrast images illustrating morphological changes in

MCF-7 cells following treatment with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO.

(F) Phase-contrast images illustrating morphological changes in

L929 cells following treatment with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO.

Scale bars, 100 µm. (G) Quantitative cell counts of MCF-7 cells

treated with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO. (H) Quantitative cell

counts of L929 cells treated with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO. The

results are presented as the mean±SEM (n=3) from three independent

experiments. *P<0.05, statistically significant

difference compared to the normal control at a 95% confidence

level. PTX, paclitaxel; GEM, gemcitabine; SG, sulfated galactan;

LSG low molecular weight SG; and LSGO, octanoyl ester-supplemented

SG. |

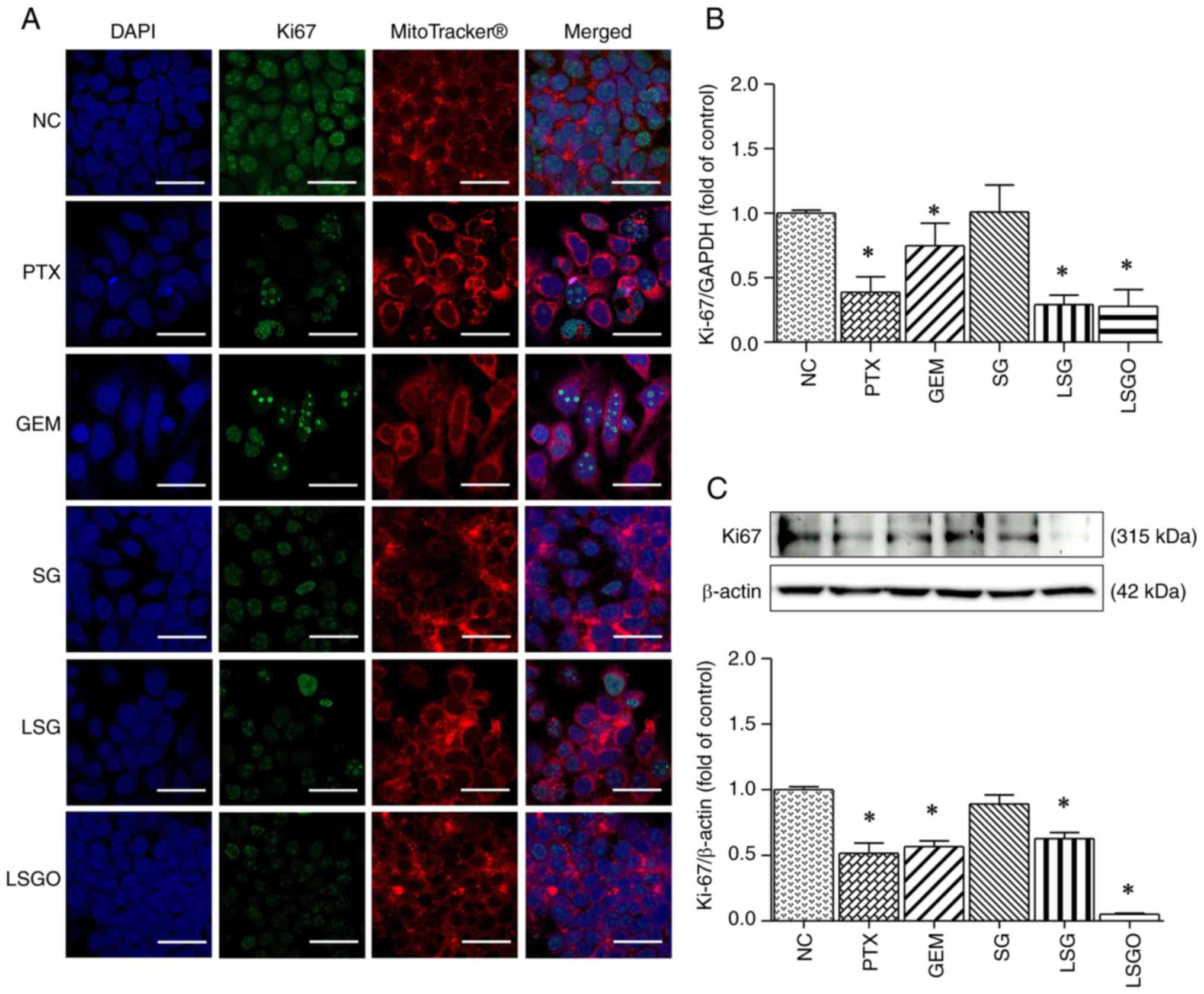

Determination of the death and

proliferation of MCF-7 cells caused by SG and its derivatives

The decreased viability of the MCF-7 breast cancer

cells following treatment with SG and its derivatives may be

associated with cell death and/or inhibited cell proliferation. To

investigate this, immunofluorescence staining was performed using

Hoechst/PI dual staining and the Ki-67 biomarker. The results

revealed that the cells treated with 500 µg/ml SG and its

derivatives exhibited a slight increase in fluorescent PI intensity

compared to the normal control, consistent with the effects

observed in the PTX- and GEM-treated cells (Fig. 2). By contrast, treatment with 500

µg/ml SG and its derivatives resulted in a significant reduction in

the fluorescent Ki-67 intensity compared to the normal control,

aligning with the results observed in the PTX- and GEM-treated

cells (Fig. 3A). Additionally, the

mRNA and protein expression levels of Ki-67 were significantly

decreased in the MCF-7 cells treated with SG derivatives,

particularly LSGO (Fig. 3B and

C), corresponding to the effects

observed with PTX and GEM. These findings suggest that SG and its

derivatives exert anti-proliferative effects on MCF-7 cells.

| Figure 3Expression levels of Ki-67 in MCF-7

cells following treatment with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO. (A)

Immunofluorescence confocal micrographs illustrating Ki-67

expression in MCF-7 cells. Ki-67 protein is shown in green, nuclei

were stained with DAPI (blue), and the cell plasma membrane was

stained with MitoTracker® Deep Red (red). Scale bars, 20

µm. (B) mRNA expression levels of Ki-67 in MCF-7 cells, assessed

using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (C) Protein

expression levels of Ki-67 in MCF-7 cells, assessed using western

blot analysis. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3)

from three independent experiments. *P<0.05,

statistically significant difference compared to the normal control

at a 95% confidence level. PTX, paclitaxel; GEM, gemcitabine; SG,

sulfated galactan; LSG low molecular weight SG; and LSGO, octanoyl

ester-supplemented SG. |

SG derivatives promote MCF-7 cell

cycle arrest

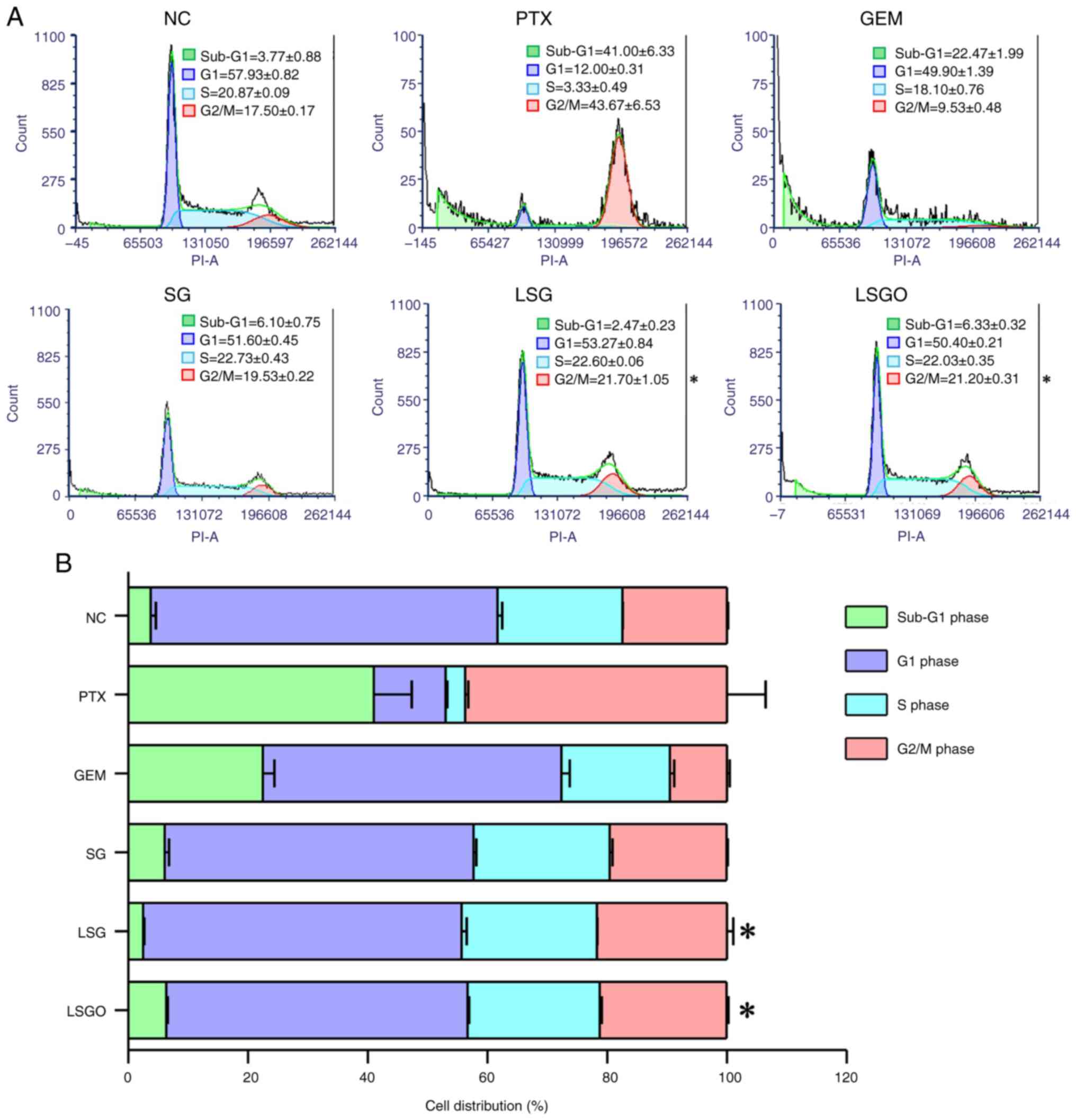

The present study further investigated the

anti-proliferative effects of SG and its derivatives on MCF-7 cells

by analyzing the DNA content across different cell cycle phases

using PI staining. Flow cytometry profiles of the nuclear DNA

content revealed alterations in cell population distribution across

phases following treatment with SG and its derivatives compared to

the normal control (untreated cells), as shown in Fig. 4. In the normal control, the cells

in the sub-G1/G1 phase accounted for 61.70%, the S phase for 20.87%

and the G2/M phase for 17.50%. However, the cells treated with SG

and its derivatives exhibited a decrease in the number of cells in

the sub-G1/G1 phase, a slight increase in the number of cells in

the S phase, and a significant increase in the number of cells in

the G2/M phase compared to the normal control. Specifically, in the

SG group, the number of cells in the sub-G1/G1, S and G2/M phases

were 57.70, 22.73 and 19.53%, respectively. In the LSG group, the

number of cells in the sub-G1/G1, S and G2/M phases were 55.74,

22.6 and 21.70%, respectively, while in the LSGO group, the number

of cells in the sub-G1/G1, S and G2/M phases were 56.73, 22.03 and

21.20%, respectively. This increase in G2/M phase arrest was

consistent with the results observed in the PTX-treated group.

Additionally, the analysis of GEM-treated cells revealed a higher

percentage of cells in the sub-G1/G1 phase compared to the other

phases. These findings suggest that SG derivatives may effectively

inhibit MCF-7 cell proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest at

the G2/M phase.

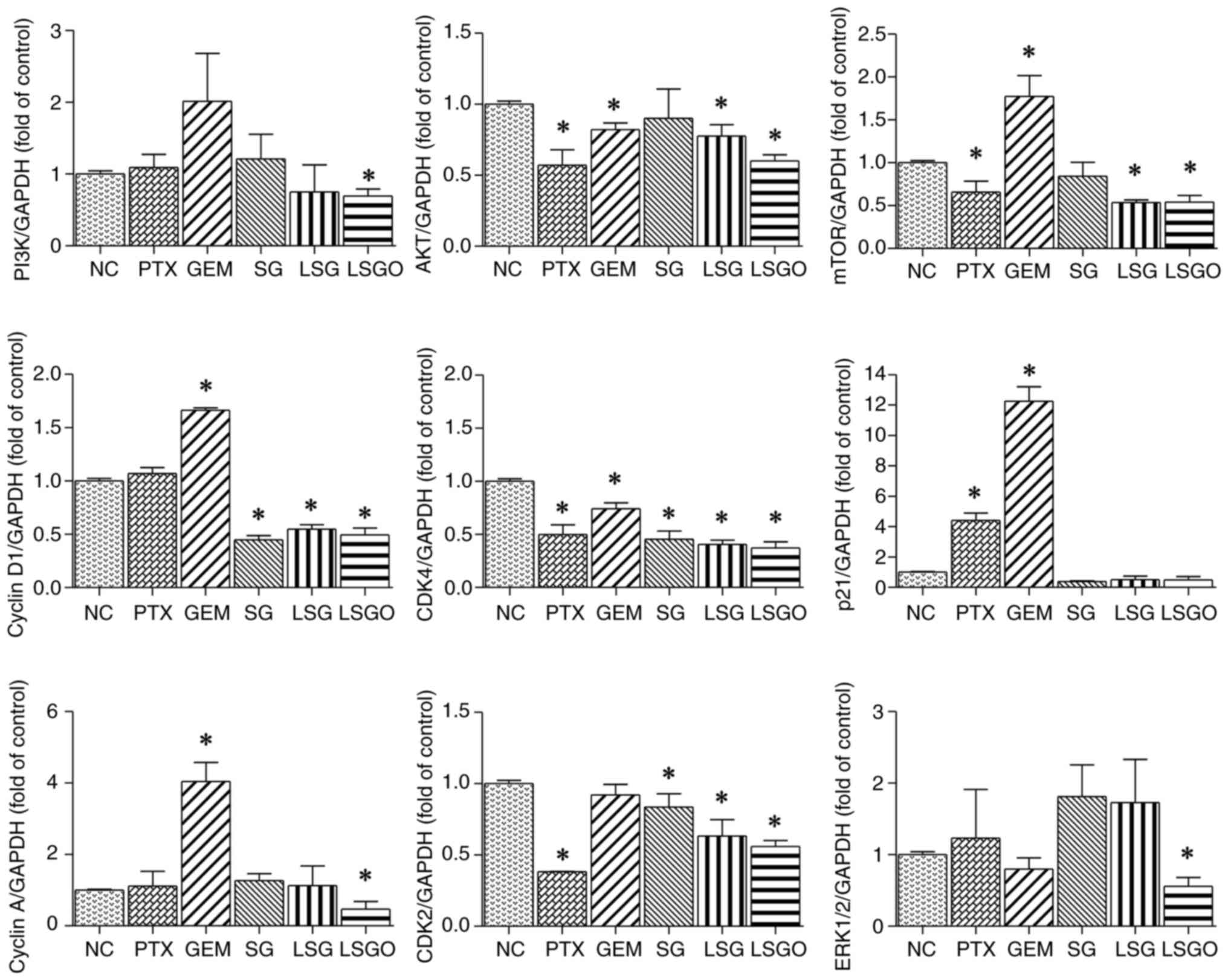

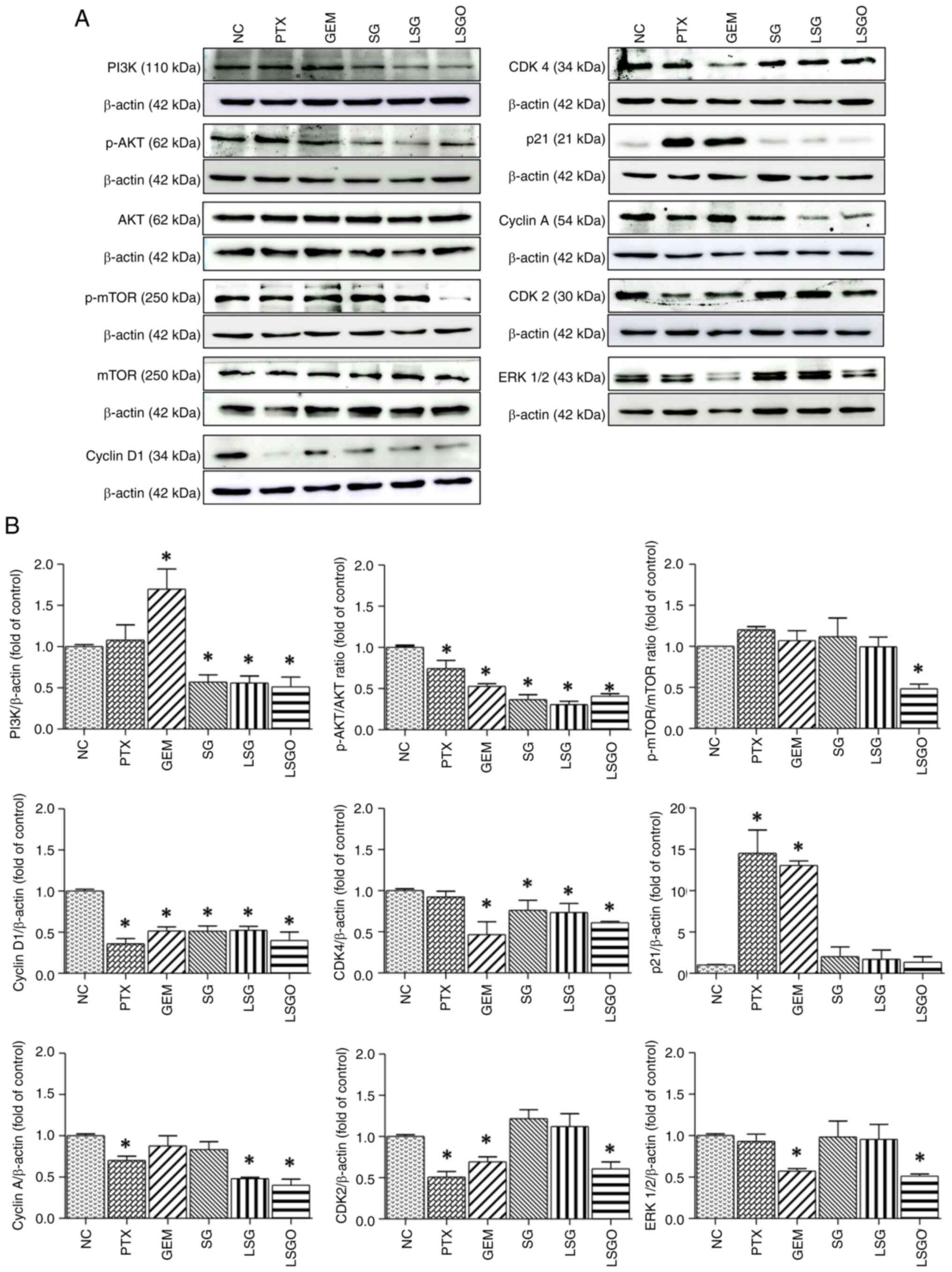

Decreased expression of mRNA and

proteins involved in MCF-7 cell cycle arrest caused by SG

derivatives

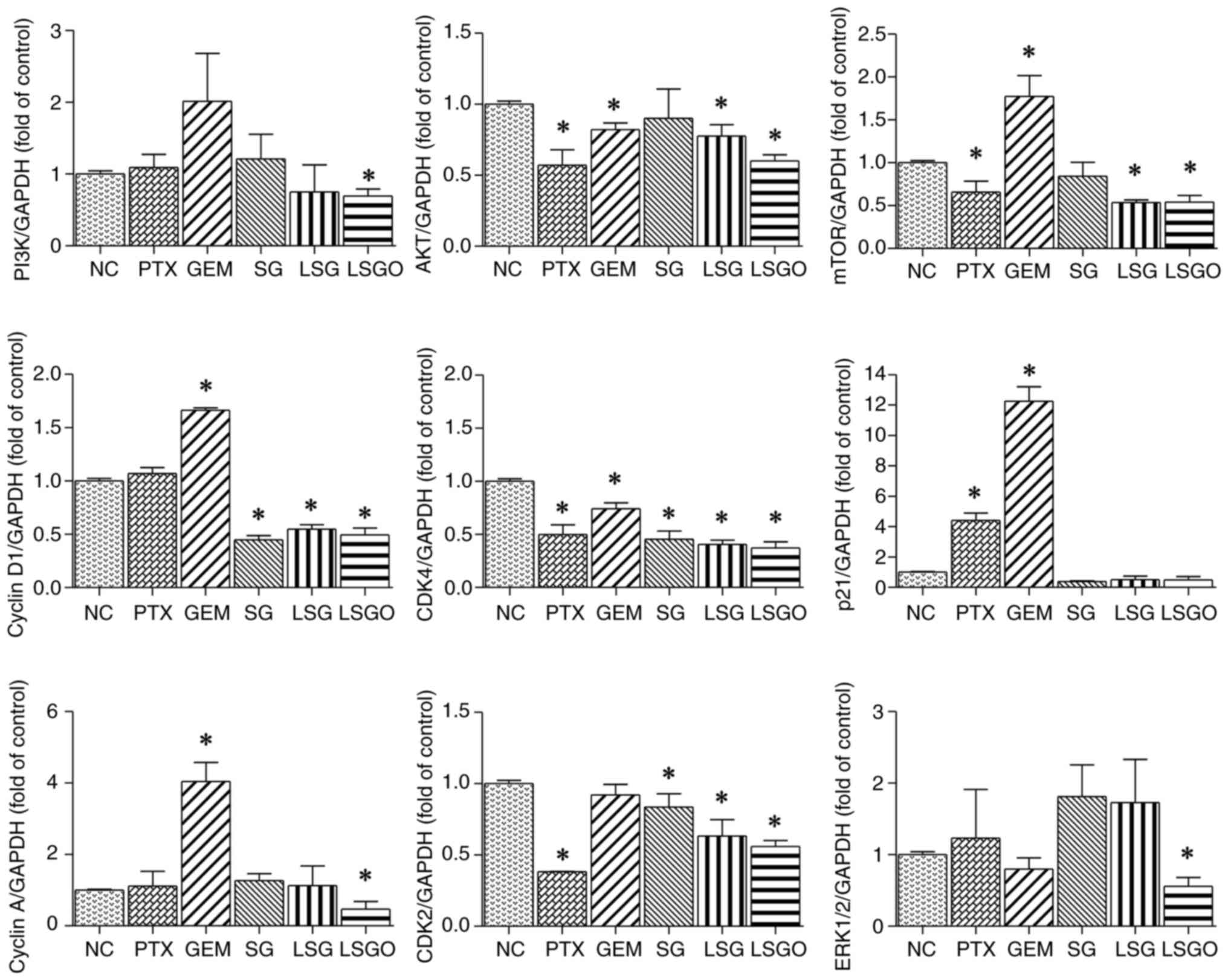

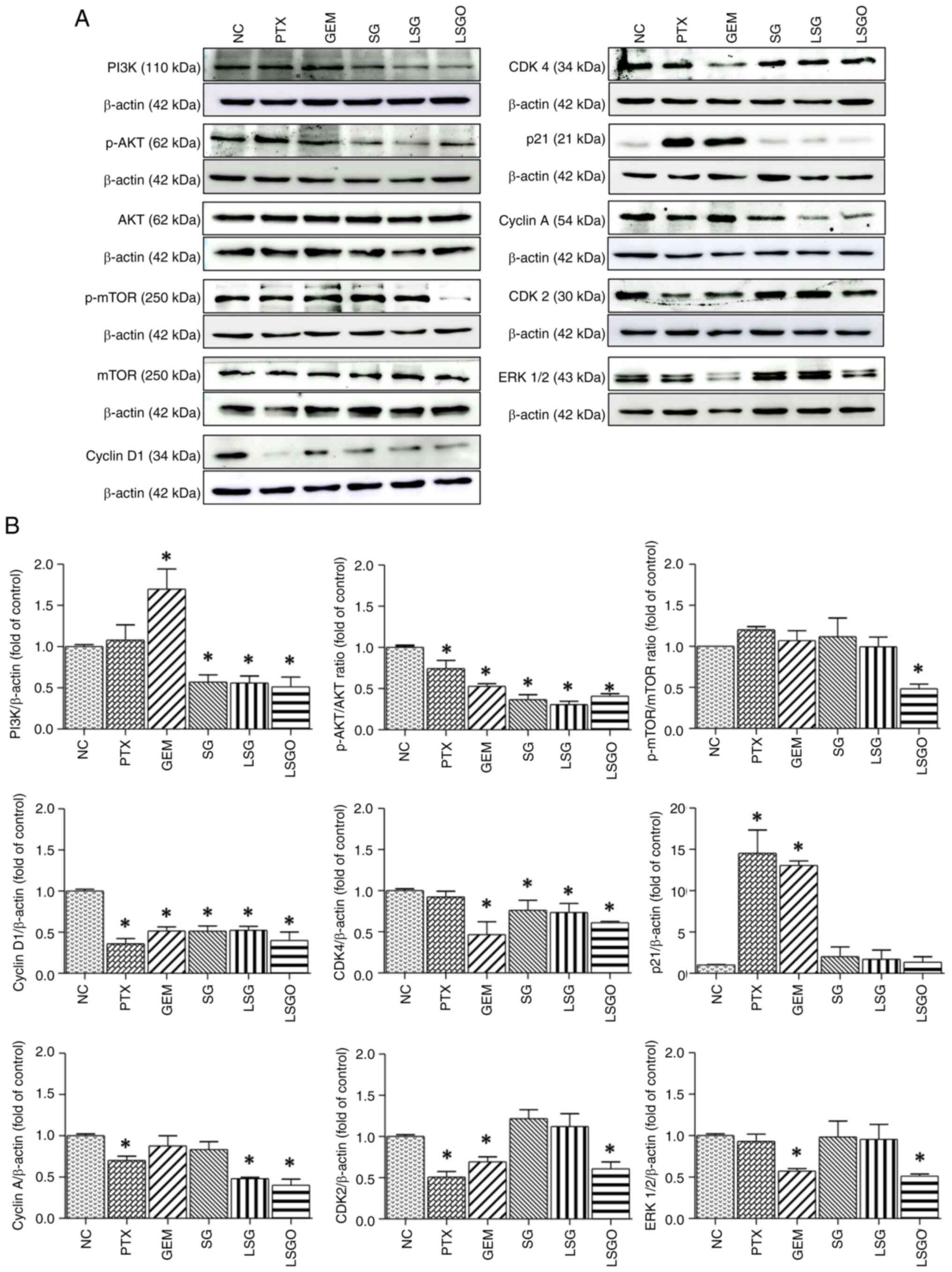

The expression of key mRNA and proteins involved in

tumor cell proliferation in MCF-7 cells, including those in the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK and CDK pathways, was assessed following

treatment with SG and its derivatives using RT-qPCR and western

blot analysis. Compared to the controls, the expression levels of

PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK and CDKs were altered in the cells treated with

SG and its derivatives, in accordance with the effects observed in

the PTX- and GEM-treated groups. The results of RT-qPCR revealed

that the mRNA expression levels of PI3K, AKT, mTOR, cyclin D1,

CDK4, cyclin A, CDK2 and ERK were significantly decreased in the

cells treated with LSGO compared to the normal control (Fig. 5). Similarly, as demonstrated in

Fig. 6, the protein expression

levels of PI3K, p-AKT/AKT, p-mTOR/mTOR, cyclin D1, CDK4, cyclin A,

CDK2 and ERK were significantly decreased in the cells treated with

LSGO compared to the NC. However, the expression levels of some

proteins (p-mTOR/mTOR, CDK2 and ERK) were unaltered in the cell

treated with SG and LSG. Of note, p21 expression remained unaltered

at both the mRNA and protein levels in the cells treated with SG

derivatives. Notably, treatment with LSGO exerted a significantly

greater reduction in both mRNA and protein expression levels,

suggesting a superior anti-proliferative effect of LSGO on MCF-7

cells.

| Figure 5mRNA expression levels of PI3K, AKT,

mTOR, cyclin D1, CDK4, p21, cyclin A, CDK2 and ERK 1/2 in MCF-7

cells treated with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO, assessed relative to

GAPDH using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. The results are

presented as the mean±SEM (n=3) from three independent experiments.

*P<0.05, statistically significant difference

compared to the normal control at a 95% confidence level. PTX,

paclitaxel; GEM, gemcitabine; SG, sulfated galactan; LSG low

molecular weight SG; and LSGO, octanoyl ester-supplemented SG. |

| Figure 6Effects of PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO

on protein expression levels in MCF-7 cells, assessed using western

blot analysis. (A) Protein expression levels of PI3K, p-AKT, AKT,

p-mTOR, mTOR, cyclin D1, CDK4, p21, cyclin A, CDK2 and ERK 1/2 in

MCF-7 cells treated with PTX, GEM, SG, LSG and LSGO, assessed using

western blot analysis. (B) Quantitative analysis of PI3K,

p-AKT/AKT, p-mTOR/mTOR, cyclin D1, CDK4, p21, cyclin A, CDK2 and

ERK 1/2 expression, normalized to β-actin. The results are

presented as the mean±SEM (n=3) from three independent experiments.

*P<0.05, statistically significant difference

compared to the normal control at a 95% confidence level. PTX,

paclitaxel; GEM, gemcitabine; SG, sulfated galactan; LSG low

molecular weight SG; and LSGO, octanoyl ester-supplemented SG. |

Discussion

Breast cancer remains one of the most prevalent

malignancies worldwide (23).

Despite advancements being made in treatment strategies, managing

the disease remains challenging, with chemotherapeutic resistance

and associated side-effects often leading to treatment failure

(24). In response, researchers

are exploring the potential of natural compounds in breast cancer

therapy, particularly for mitigating chemotherapy-induced

side-effects. Previous studies have demonstrated that

polysaccharides inhibit cancer cell proliferation and survival by

inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. For instance, serum

collected from fucoidan-treated rats was shown to inhibit the

proliferation and increase the apoptosis of MCF-7 cells (25). Fucoidan from the brown algae,

Fucus vesiculosus, at concentrations ranging from 100 to 300

µg/ml, has also been reported to induce apoptosis and promote cell

cycle arrest in CL-6 CCA cells by increasing the levels of

apoptotic protein markers and decreasing the expression of cyclin

and CDK molecules (26). SG,

extracted from the red algae, G. fisheri, is a sulfated

polysaccharide (SP) with a galactose backbone and a high percentage

of sulfate groups (27). It has

been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and induce cell cycle

arrest in HuCCA-1 cells by downregulating cyclin/CDK expression

following treatment at concentrations of 10 and 50 µg/ml (13). Thus, the anticancer activity of

polysaccharides may be influenced by several factors, including

their molecular structure, dosage and the type of cancer cells

involved (28). Additionally,

reducing molecular weight (15,29)

and supplementing SP with an octanoyl ester (16) have been found to enhance their

biological effectiveness. In the present study, the anticancer

activity of SG from G. fisheri, along with its structurally

modified derivatives, LSG and LSGO, was investigated in MCF-7

breast cancer cells and L929 normal lung fibroblasts. The effects

were compared with those of unmodified SG and the anticancer drugs,

PTX and GEM. The concentrations used for SG and its derivatives

(125-1,000 µg/ml) in the present study reflect typical dosing

ranges for marine polysaccharides (17), which generally exhibit lower

cytotoxicity per unit mass compared to small-molecule drugs such as

PTX and GEM (0.2-1 µg/ml) (18).

This difference in dosage is necessary due to variations in

molecular size, bioavailability and mechanisms of action.

The results of the present study demonstrated that

SG and its derivatives decreased cell viability and suppressed

MCF-7 cell proliferation, in accordance with the reduced Ki-67

expression and the induction of cell cycle arrest, particularly in

the cells treated with LSGO, similar to the effects observed with

PTX and GEM. Treatment with LSGO in MCF-7 cells exerted a greater

anti-proliferative effect, indicating that its molecular structure

is positively associated with its biological activity (30). Furthermore, the enhanced

anti-proliferative activity of LSGO suggests that it may improve

cellular internalization, thereby increasing its overall efficacy

(31). A high Ki-67 expression has

been shown to be associated with cancer proliferation and it is a

well-established indicator of prognosis and clinical outcomes

(32). Since Ki-67 remains active

during the G1, S, G2 and M phases of the cell cycle, it serves as a

reliable marker of cell proliferation and a recognized hallmark of

oncogenesis (33). Notably, the

decreased Ki-67 expression through antisense oligonucleotides has

been shown to inhibit cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth

(34). Herein, the reduction of

Ki-67 expression in MCF-7 cells following SG and its derivatives

treatment suggests anti-proliferative activity, consistent with

previous findings on polysaccharides extracted from

Crataegus (Hawthorn), which inhibited human colon cancer

HCT116 cell proliferation by reducing Ki-67 protein expression and

inducing cell cycle arrest (35).

However, these effects were not observed in L929 normal

fibroblasts, indicating a selective effect on breast cancer cells

(36). This selectivity may be

attributed to differences in cellular metabolism, surface receptor

expression, and intracellular signaling between normal and cancer

cells (37).

In the present study, these effects were achieved

through the downregulation of upstream signaling molecules of

PI3K/Akt/mTOR, ERK, and CDKs at both the gene and protein levels.

This downregulation may be attributed to the structural similarity

of SG derivatives to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), which

can bind to growth factor receptors and/or ligands, thereby

inhibiting receptor-ligand complex formation (13). It has been demonstrated that

natural SPs share structural similarities with HSPGs and can mimic

their functions. These SPs can interfere with the binding of growth

factors to their receptors or co-receptors, leading to the

inhibition of downstream signaling pathway activation in cancer

cells (38). However, previous

research indicates that SG derived from G. fisheri does not

directly interact with EGF, but instead interacts with the EGFR,

resulting in the downregulation of EGFR activity in CCA cells

(14). The competitive binding of

SG may disrupt receptor dimerization, leading to a reduction in

p-EGFR and p-ERK levels (14).

Therefore, by inhibiting growth factor receptors such as EGFR, SG

derivatives may indirectly regulate PI3K/Akt/mTOR and ERK signaling

molecules.

In MCF-7 cells treated with LSGO, the decreased

expression of PI3K, AKT, mTOR and ERK at both the mRNA and protein

levels resulted in a reduction of cyclin D1 and CDK4 expression,

the first protein complex to become active in the G1 phase

(39). The downregulation of

cyclin D1 and CDK4 leads to the decreased transcription of key

target genes, including cyclin E, cyclin B, CDK2 and CDK1, thereby

disrupting cell cycle progression from the G1 to S phase (40). Furthermore, the downregulation of

genes involved in the G1 and S phases also led to reduced

expression of cyclin A and CDK2 at both the gene and protein

levels. Given their critical roles in DNA synthesis, proper S phase

progression, and the transition from S to G2 phase, this reduction

may significantly affect cell cycle regulation (41). The findings of the present study

indicate that SG derivatives, particularly LSGO induced cell cycle

arrest at the G2/M phase in MCF-7 cells, potentially through the

downregulation of cyclin/CDK complexes, particularly cyclin A and

CDK2. These results are in contrast to those of previous studies

reporting that SG derived from G. fisheri induces cell cycle

arrest at the G1 phase in CCA cells by downregulating cyclin D,

cyclin E, CDK4 and CDK2. This reduction in cyclin/CDK expression is

associated with the upregulation of p53 and p21, a key regulator of

cyclin/CDK inhibition (13). By

contrast, these findings suggest that the anti-proliferative effect

of SG derivatives in MCF-7 cells is not mediated by the increased

expression of p21.

Another possible explanation for why SG derivatives

inhibit MCF-7 cell proliferation at the G2/M phase, including the

reduction of cyclin A and CDK2, may be related to the

structure-activity association of SG derivatives and cancer cell

type specificity (26).

Polysaccharides from different sources have been reported to induce

cell cycle arrest at various phases in different cancer cell lines

(35). For example, SP from

Laetiporus sulphureus fruiting bodies has been shown to

induce cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase in triple-negative

breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells (42). Similarly, a homogeneous

polysaccharide from Crataegus (Hawthorn) inhibited the

proliferation of human colon cancer HCT116 cells by inducing cell

cycle arrest at the S/G2 phase (35). Additionally, the combination of

fucoidan with natural/organic ingredients, including vegetable

juice, mulberry and wheatgrass, has been reported to increase the

proportion of cells arrested in the G2/M phase in oral squamous

cell carcinoma (43). The

implications of the findings of the present study extend beyond

breast cancer treatment, as the cell cycle regulatory proteins

targeted by SG derivatives are involved in various cancer types.

While previous studies have reported individual chemical

modifications of SG, such as molecular weight reduction and

esterification, the present study is the first to combine both

modifications in a single structure. This combination resulted in

the disruption of breast cancer cells and the inhibition of key

signaling pathways in MCF-7 cells. These findings support the

potential use of LSGO as an optimized SG derivative with enhanced

anti-proliferative activity compared to either unmodified SG or SG

with reduced molecular weight alone. Although the present study

demonstrates the modulation of the PI3K/AKT and ERK signaling

pathways following treatment with SG and its derivatives, further

studies incorporating pathway-specific inhibitors or gene silencing

approaches are warranted to validate the causal involvement of

these pathways in mediating the observed anti-proliferative and

cytotoxic effects. Additionally, future research is required to

include Annexin V/PI staining to clarify the apoptosis-related

mechanisms of SG and its derivatives, investigate their molecular

interactions with regulatory proteins, evaluate their efficacy in

in vivo models, and explore their potential synergy with

existing chemotherapeutic agents to reduce side-effects in with

breast cancer.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

indicate that SG derivatives from G. fisheri exhibit mild,

yet effective anti-proliferative activity in MCF-7 cells by

inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing cell cycle arrest at the

G2/M phase. This effect is mediated through the inhibition of

upstream signaling molecules, cyclins and CDKs, which regulate

MCF-7 cell proliferation. These findings highlight the potential

use of SG derivatives, particularly LSGO, as natural compounds for

breast cancer treatment and warrant further investigation into

their clinical applications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Dylan Southard

(the KKU Publication Clinic, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen,

Thailand) for editing the manuscript.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by a Postgraduate Study

Support Grant of the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University and

the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand

(Grant no. IN66081).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JP and TR conceived and designed the study. JP, SS

and TR performed the experiments. JP, SS, WS, TS, JK, KW and TR

were responsible for data analysis. JP, SS and TR participated in

the drafting of the manuscript. JK, KW and TR edited and finalized

the manuscript. JK, KW and TR supervised the study. JP and TR

provided funding and managed the project. JP, SS and TR confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ilango S, Paital B, Jayachandran P, Padma

PR and Nirmaladevi R: Epigenetic alterations in cancer. Front

Biosci (Landmark Ed). 25:1058–1109. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Damiescu R, Efferth T and Dawood M:

Dysregulation of different modes of programmed cell death by

epigenetic modifications and their role in cancer. Cancer Lett.

584(216623)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Feng Y, Spezia M, Huang S, Yuan C, Zeng Z,

Zhang L, Ji X, Liu W, Huang B, Luo W, et al: Breast cancer

development and progression: Risk factors, cancer stem cells,

signaling pathways, genomics, and molecular pathogenesis. Genes

Dis. 5:77–106. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lee S, Rauch J and Kolch W: Targeting MAPK

signaling in cancer: Mechanisms of drug resistance and sensitivity.

Int J Mol Sci. 21(1102)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Dong C, Wu J, Chen Y, Nie J and Chen C:

Activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway causes drug resistance in

breast cancer. Front Pharmacol. 12(628690)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mangé A, Coyaud E, Desmetz C, Laurent E,

Béganton B, Coopman P, Raught B and Solassol J: FKBP4 connects

mTORC2 and PI3K to activate the PDK1/Akt-dependent cell

proliferation signaling in breast cancer. Theranostics.

9:7003–7015. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Palmer N and Kaldis P: Less-well known

functions of cyclin/CDK complexes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 107:54–62.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ding L, Cao J, Lin W, Chen H, Xiong X, Ao

H, Yu M, Lin J and Cui Q: The roles of cyclin-dependent kinases in

cell-cycle progression and therapeutic strategies in human breast

cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 21(1960)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Al Bitar S and Gali-Muhtasib H: The role

of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21cip1/waf1 in

targeting cancer: Molecular mechanisms and novel therapeutics.

Cancers (Basel). 11(1475)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Menon SS, Guruvayoorappan C, Sakthivel KM

and Rasmi RR: Ki-67 protein as a tumour proliferation marker. Clin

Chim Acta. 491:39–45. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Burcombe R, Wilson GD, Dowsett M, Khan I,

Richman PI, Daley F, Detre S and Makris A: Evaluation of Ki-67

proliferation and apoptotic index before, during and after

neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer

Res. 8(R31)2006.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Liyanage UE, Law MH, Han X, An J, Ong JS,

Gharahkhani P, Gordon S, Neale RE and Olsen CM: 23andMe Research

Team et al. Combined analysis of keratinocyte cancers

identifies novel genome-wide loci. Hum Mol Genet. 28:3148–3160.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sae-Lao T, Tohtong R, Bates DO and

Wongprasert K: Sulfated galactans from red seaweed Gracilaria

fisheri target EGFR and inhibit cholangiocarcinoma cell

proliferation. Am J Chin Med. 45:615–633. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sae-Lao T, Luplertlop N, Janvilisri T,

Tohtong R, Bates DO and Wongprasert K: Sulfated galactans from the

red seaweed Gracilaria fisheri exerts anti-migration effect on

cholangiocarcinoma cells. Phytomedicine. 36:59–67. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Fan J, Zhu J, Zhu H, Zhang Y and Xu H:

Potential therapeutic target for polysaccharide inhibition of colon

cancer progression. Front Med (Lausanne).

10(1325491)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Rudtanatip T, Somintara S, Sakaew W,

El-Abid J, Cano ME, Jongsomchai K, Wongprasert K and Kovensky J:

Sulfated galactans from Gracilaria fisheri with supplementation of

octanoyl promote wound healing activity in vitro and in vivo.

Macromol Biosci. 22(e2200172)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Srimongkol P, Songserm P, Kuptawach K,

Puthong S, Sangtanoo P, Thitiprasert S, Thongchul N, Phunpruch S

and Karnchanatat A: Sulfated polysaccharides derived from marine

microalgae, Synechococcus sp. VDW, inhibit the human colon cancer

cell line Caco-2 by promoting cell apoptosis via the JNK and p38

MAPK signaling pathway. Algal Res. 69(102919)2023.

|

|

18

|

Aslama A, Bergerb MR, Ullaha I, Hameeda A

and Masoodc F: Preparation and evaluation of cytotoxic potential of

paclitaxel containing poly-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalarate

(PTX/PHBV) nanoparticles. Braz J Biol. 83(e275688)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Dehghani N, Tafvizi F and Jafari P: Cell

cycle arrest and anti-cancer potential of probiotic

Lactobacillus rhamnosus against HT-29 cancer cells.

Bioimpacts. 11:245–252. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Intuyod K, Hahnvajanawong C, Pinlaor P and

Pinlaor S: Anti-parasitic drug ivermectin exhibits potent

anticancer activity against gemcitabine-resistant

cholangiocarcinoma in vitro. Anticancer Res. 39:4837–4843.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Shendge AK, Basu T and Mandal N:

Evaluation of anticancer activity of Clerodendrum viscosum

leaves against breast carcinoma. Indian J Pharmacol. 53:377–383.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Marquette C and Nabell L:

Chemotherapy-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Curr Treat Options

Oncol. 13:263–275. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

He X, Xue M, Jiang S, Li W, Yu J and Xiang

S: Fucoidan promotes apoptosis and inhibits EMT of breast cancer

cells. Biol Phram Bull. 42:442–447. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Chantree P, Na-Bangchang K and Martviset

P: Anticancer activity of fucoidan via apoptosis and cell cycle

arrest on cholangiocarcinoma cell. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

22:209–217. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wongprasert K, Rudtanatip T and Praiboon

J: Immunostimulatory activity of sulfated galactans isolated from

the red seaweed Gracilaria fisheri and development of resistance

against white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) in shrimp. Fish Shellfish

Immunol. 36:52–60. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Li N, Wang C, Georgiev MI, Bajpai VK,

Tundis R, Simal-Gandara J, Lu X, Xiao J, Tang X and Qiao X:

Advances in dietary polysaccharides as anticancer agents:

Structure-activity relationship. Trends Food Sci Technol.

111:360–377. 2021.

|

|

29

|

Lu J, Shi KK, Chen S, Wang J, Hassouna A,

White LN, Merien F, Xie M, Kong Q, Li J, et al: Fucoidan extracted

from the New Zealand Undaria pinnatifida-physicochemical

comparison against five other fucoidans: Unique low molecular

weight fraction bioactivity in breast cancer cell lines. Mar Drugs.

16(461)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wang Y, Xing M, Cao Q, Ji A, Liang H and

Song S: Biological activities of fucoidan and the factors mediating

its therapeutic effects: A review of recent studies. Mar Drugs.

17(183)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Sakaew W, Somintara S, Jongsomchai K, El

Abid J, Wongprasert K, Kovensky J and Rudtanatip T: Octanoyl

esterification of low molecular weight sulfated galactan enhances

the cellular uptake and collagen expression in fibroblast cells.

Biomed Rep. 19(99)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Davey MG, Hynes SO, Kerin MJ, Miller N and

Lowery AJ: Ki-67 as a prognostic biomarker in invasive breast

cancer. Cancers (Basel). 13(4455)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yang C, Zhang J, Ding M, Xu K, Li L, Mao L

and Zheng J: Ki67 targeted strategies for cancer therapy. Clin

Transl Oncol. 20:570–575. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li LT, Jiang G, Chen Q and Zheng JN: Ki67

is a promising molecular target in the diagnosis of cancer

(review). Mol Med Rep. 11:1566–1572. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ma L, Xu GB, Tang X, Zhang C, Zhao W, Wang

J and Chen H: Anti-cancer potential of polysaccharide extracted

from hawthorn (Crataegus.) on human colon cancer cell line HCT116

via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. J Funct Foods.

64(103677)2020.

|

|

36

|

Abdala-Díaz RT, Casas-Arrojo V,

Castro-Varela P, Riquelme C, Carrillo P, Medina MA, Cárdenas C,

Becerra J and Pérez Manríquez C: Immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and

potential anticancer activity of the polysaccharides of the fungus

Fomitiporia chilensis. Molecules. 29(3628)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Akhtar MJ, Ahamed M, Alhadlaq HA,

Alrokayan SA and Kumar S: Targeted anticancer therapy:

Overexpressed receptors and nanotechnology. Clin Chim Acta.

436:78–92. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Cheng JJ, Chang CC, Chao CH and Lu MK:

Characterization of fungal sulfated polysaccharides and their

synergistic anticancer effects with doxorubicin. Carbohydr Polym.

90:134–139. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Asghar U, Witkiewicz AK, Turner NC and

Knudsen ES: The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent

kinases in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 14:130–146.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Finn RS, Aleshin A and Slamon DJ:

Targeting the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) 4/6 in estrogen

receptor-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res.

18(17)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Gopinathan L, Tan SL, Padmakumar VC,

Coppola V, Tessarollo L and Kaldis P: Loss of Cdk2 and cyclin A2

impairs cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res.

74:3870–3879. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Jen CI, Lu MK, Lai MN and Ng LT: Sulfated

polysaccharides of Laetiporus sulphureus fruiting bodies exhibit

anti-breast cancer activity through cell cycle arrest, apoptosis

induction, and inhibiting cell migration. J Ethnopharmacol.

321(117546)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chen PH, Chiang PC, Lo WC, Su CW, Wu CY,

Chan CH, Wu YC, Cheng HC, Deng WP, Lin HK and Peng BY: A novel

fucoidan complex-based functional beverage attenuates oral cancer

through inducing apoptosis, G2/M cell cycle arrest and retarding

cell migration/invasion. J Funct Foods. 85(104665)2021.

|