1. Introduction

Viruses, particularly respiratory viruses, such as

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), pose

immense challenges to public health as they easily transmit through

aerosols and droplets, as well as through direct contact with

contaminated surfaces. The oral cavity provides a prime location

for viral replication, thus becoming a reservoir for viral

particles; saliva also plays a vital role in this regard.

Accordingly, reducing viral loads in oral fluids has come to occupy

a place of prominence in efforts toward halting the spread of

viruses, particularly in high-risk environments such as clinics and

hospitals (1,2). Antiviral mouthwashes are easily

applied, are inexpensive and are an accessible means of infection

control. Traditionally used mouthwashes aid in the maintenance of

oral hygiene as they are bactericidal or fungicidal agents;

however, there is currently an increasing interest in the

evaluation of their virucidal potentials. Studies have primarily

focused on povidone-iodine (PVP-I), chlorhexidine gluconate (CHX),

cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC), essential oils and newer compounds

phthalocyanine derivatives. These agents function through the

disruption of the viral envelopes or interference with replication

processes, thus leading to a loss of viral infectivity and shedding

(3). Schürmann et al

(2) focused on CPC-based

formulations as they could break viral lipid membranes, which

prevented coronaviruses and other related pathogens from spreading.

Rodríguez-Casanovas et al (3) and Carrouel et al (4) in their study demonstrated that few

mouthwashes can effectively eliminate viruses.

Mouthwashes with essential oils have

anti-inflammatory properties that have helped individuals deal with

the systemic effects of viral infections and have also made

antiviral treatment more flexible. The efficiency of such

mouthwashes in decreasing viral shedding among patients having mild

or asymptomatic COVID-19 has been proven through clinical studies

performed by Takeda et al (5) and Vilhena et al (6). Martínez Lamas et al (7) in their study has confirmed the

virucidal properties of PVP-I, suggesting its clinical use,

particularly in dentistry. The antiseptic CHX, frequently used in

dentistry, has also demonstrated short-term virucidal activity.

Jain et al (8) found that a

0.2% CHX solution inactivated >99.9% of SARS-CoV-2 within 30

sec, demonstrating its rapid action compared to PVP-I. Evidence

from the literature has indicated that CHX only reduces the viral

load for a short period of time and is therefore less effective as

a standalone treatment. Its combination with other agents, such as

PVP-I needs to be evaluated in a clinical setting (9). CHX is a rapid, yet temporary addition

to more long-lasting agents, such as PVP-I, and it can greatly

reduce oral viral loads when used in conjunction with

phthalocyanine derivatives and CPC (10). Perussolo et al (10) conducted a study where they tested

three types of mouthwash randomly. They discovered that these

mouthwashes were able to decrease the load of SARS-CoV-2 among

hospitalized patients. This supports the concept that mouthwashes

may limit the spread of the virus. Mouthwashes containing

phthalocyanine derivatives have also shown promising efficacy in

reducing hospitalization periods for patients with COVID-19, and

CPC-containing mouthwashes have also shown promising in

vitro activity against enveloped viruses (11,12).

Both CPC and phthalocyanine derivatives possess notable antiviral

activity. CPC functions by disrupting the lipid envelope of

viruses, which leads to rapid virucidal effects (5), while phthalocyanine derivatives

inhibit viral replication and reduce inflammation, which renders

them very useful in high-risk and hospitalized patients (6).

The majority of the formulations integrate

antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, thereby enhancing

their efficacy in reducing viral loads and improving clinical

outcomes (13). Although various

mouthrinses that act against viruses, as studied in previous

literature (14-17),

have been proven to be useful and affordable, their functional

properties against these viruses need to be fully investigated.

The present review provides an overview of the

effectiveness of antiviral mouthwashes, particularly based on

scientific studies, in an aim to assess the role of these

mouthwashes in reducing the spread of viruses. For this purpose,

the PubMed and Google Scholar databases were searched to provide

related data for the present review, which concentrated on

systematic reviews, as well as in vitro, in vivo,

clinical and observational studies evaluating the virucidal

activity, real-world efficacy and preventive potential of antiviral

mouthwashes that were published between 2020 and 2025. The present

review discusses the mechanisms and relative efficacy, clinical

effectiveness and preventive potential of several mouthwash

formulations.

2. Antiviral mouthrinses

Types of antiviral mouthwashes

Antiviral mouthwashes are formulated to degrade the

structures of viruses, inhibit multiplication and decrease

infectivity in the oral environment. There is a plethora of types,

each with its mode of action:

PVP-I. PVP-I is an iodine-based antiseptic

solution. This disrupts the lipid envelope and then causes

oxidation of the viral proteins. As a result, the viruses becomes

inactivated. This product has wide applicability over viruses, such

as SARS-CoV-2 and is hence used quite commonly for preprocedural

rinsing and infection control in health care settings (1,18).

CPC. This compound is a quaternary ammonium

agent that functions at the lipid envelope level leading to

membrane disintegration and the release of viral genetic material,

ultimately resulting in viral inactivation. It also has some

anti-inflammatory effects and can effectively kill viruses, such as

influenza A and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). It is very

commonly used for everyday oral hygiene, although it can also be

used in managing symptomatic viral infections (5,13).

CPC is a broad-spectrum antiseptic agent often mixed with zinc or

other additives to enhance its performance, according to

Garcia-Sanchez et al (19).

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

H2O2 produces reactive oxygen species (ROS),

which oxidizes viral proteins, rendering viruses, including

SARS-CoV-2, vulnerable to oxidative stress. It is commonly applied

in general disinfection as well as a mouthrinse; however, it is not

effective compared to PVP (20).

According to the systematic review performed by Ortega et al

(16), there is no scientific

evidence supporting the use of hydrogen peroxide mouthwash for

reducing the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva.

Phthalocyanine-based mouthwashes.

Phthalocyanine derivatives present in mouthwashes interfere with

nucleic acid synthesis and thus inhibit viral replication. They are

particularly effective for use in high-risk environments and for

use preventively in immunocompromised individuals (21).

Alcohol-based mouthwashes. These mouthwashes

contain 20-30% of ethanol, they interfere with the lipid envelope

of enveloped viruses and can denature proteins, leading to viral

inactivation. There are only a limited number of clinical studies

evaluating the antiviral potential of mouthrinses (22). Although mouthwashes are used for

routine oral hygiene maintenance, they have limited direct efficacy

against SARS-CoV-2 since more ethanolic concentration is required

for virucidal property. However, their broad-spectrum antiseptic

properties render them a valuable component of infection control

protocols (18,23). Listerine contains essential oils

and alcohol, which are effective against enveloped viruses, such as

herpes simplex virus and influenza A. However, its efficacy against

SARS-CoV-2 is uncertain (24,25).

CHX. CHX has been extensively studied for its

broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, even against viruses. It

disrupts cell membranes and consequently does not allow viral

replication, in addition to inactivating the viruses within the

oral cavity. CHX has generated interest as it can significantly

reduce the viral load of SARS-CoV-2. The study by Huang and Huang

(26) revealed a marked decrease

in the levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in oropharyngeal samples following

treatment with CHX mouthwash, thus supporting its use in infection

control protocols. CHX also plays a role in reducing the risk of

viral transmission in healthcare settings, particularly when used

preprocedurally. Other studies have suggested that CHX can be

incorporated into regular oral hygiene to assist in lowering oral

viral loads, even in patients with symptomatic viral infections

(27,28).

Other solutions. Other active ingredients,

such as zinc-based solutions and enzyme-protein mixtures are

virucidal. Zinc-based solutions help to prevent viral

multiplication in the nasopharyngeal region (29). In addition, the enzyme-protein

mixtures have been found to be capable of inhibiting surrogate

viruses, such as feline coronavirus, thereby rendering them useful

in extended antiviral applications (14).

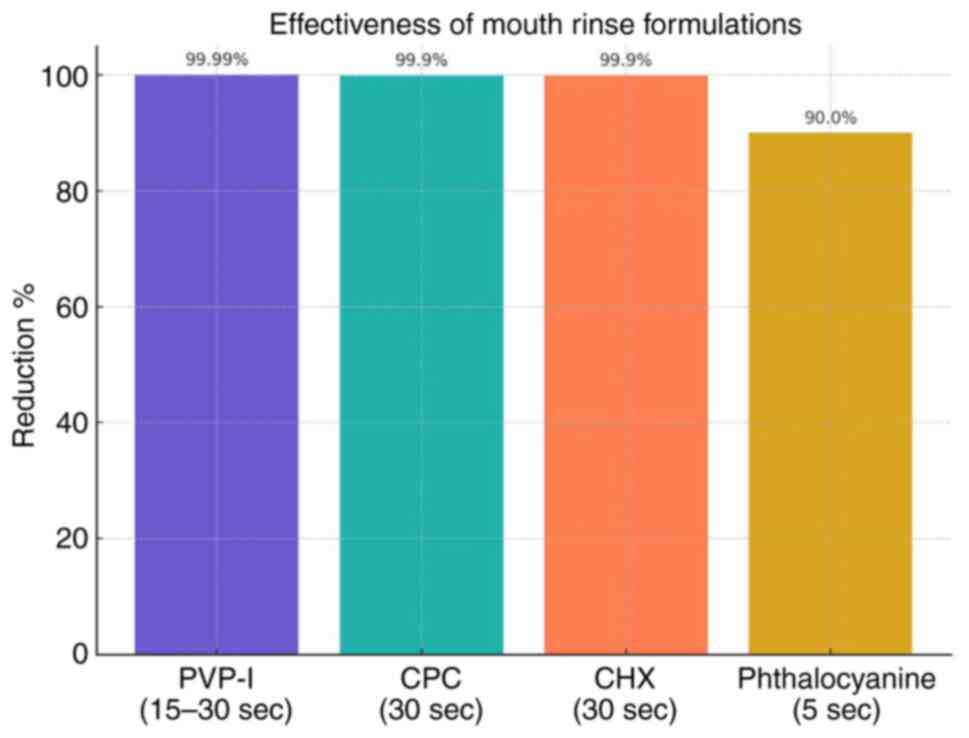

Antiviral mouthwashes: Mechanisms and

efficacy

The efficacy of antiviral mouthwashes depends on

their active ingredients, concentration and mechanisms of action. A

standardized comparison of these formulations, incorporating virus

strain, test type, effectiveness and real-world applications is

provided in Table I. Various

mechanisms of viral disruption include the following:

| Table IComparison of mouthrinse

formulations. |

Table I

Comparison of mouthrinse

formulations.

| Mouthwash

formulation | Mechanism of

action | Virus efficacy | Types of

studies | Concentration | Reduction % | Contact time | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Povidone-iodine

(PVP-I) | Lipid envelope

disruption; protein oxidation | SARS-CoV-2 | In

vitro | 1% | 99.99% | 15-30 sec | (1) |

| Cetylpyridinium

chloride (CPC) | Lipid envelope

disruption; anti-inflammatory properties | SARS-CoV-2,

influenza A, RSV | In vitro and

clinical | 0.005% | 99.9% | 30 sec | (5) |

| Chlorhexidine

(CHX) | Lipid envelope

disruption; protein oxidation | SARS-CoV-2 | Clinical (RCT) | 0.12-0.2% | 99.9% | 30 sec | (8) |

|

Phthalocyanine-based mouthwash | Inhibition of viral

replication; anti-inflammatory effects | SARS-CoV-2 | In

vitro | 0.02-0.05% | 90% | 30 sec, 1 min and 5

min | (21) |

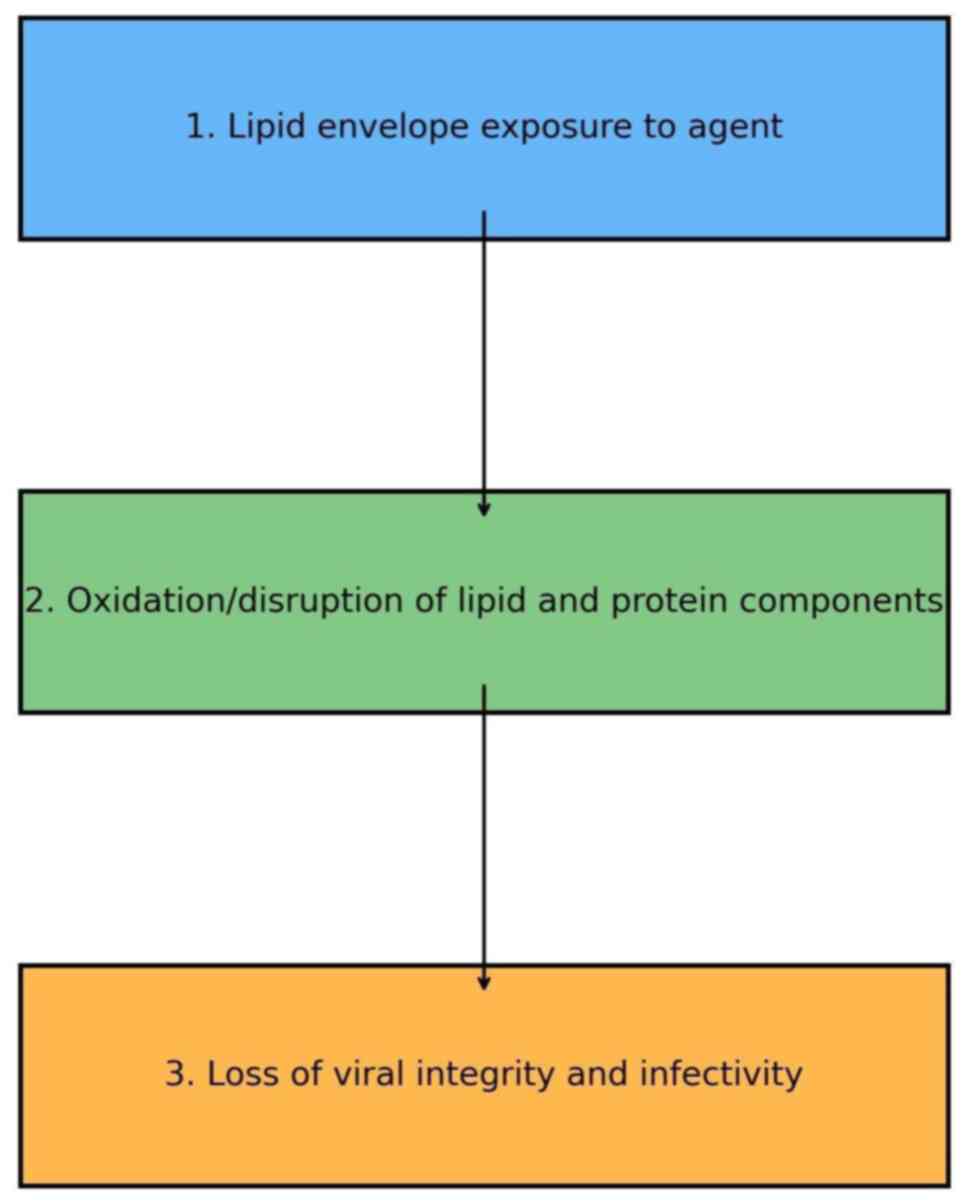

Lipid envelope disruption. The lipid envelope

is essential for the infectivity of enveloped viruses, such as

SARS-CoV-2. If this structure is disrupted, the virus is no longer

infectious. Some of the common agents that function by lipid

envelope disruption mechanism are as follows:

i) PVP-I. PVP-I is an oxidizing agent; it

destroys the lipid and protein moieties of the viral envelope

causing a structural collapse that leads to the inactivation of the

virus. The recent study by Hassandarvish et al (1) indicated that concentrations of PVP-I

from 0.23-1% provide >99.99% inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 in only

15 sec after contact. The study by Barrueco et al (28) also highlighted the efficacy of

PVP-I in reducing viral infectivity in clinical and public health

settings. Therefore, PVP-I has proven to be very useful in the

preparation of pre-procedural oral rinses for use in the healthcare

environment as it can markedly reduce viral loads in aerosols

(Fig. 1).

ii) CPC. CPC disrupts the lipid envelope due

to its capability to penetrate it and leak out the viral content.

Rius-Salvador et al (30)

reported a reduction in the viral titers of influenza A and RSV by

>99.9% with an oral care concentration within 30 sec (30). Thus, CPC is very safe and effective

for day-to-day oral hygiene and can be used effectively in

non-clinical settings to regulate enveloped viruses.

iii) CHX. CHX disrupts the lipid envelope of

SARS-CoV-2, similar to PVP-I and CPC. Its positive charge

destabilizes and inactivates the viral membrane by binding to its

negatively charged components. CHX rapidly inactivates viruses at

0.1-0.2%, rendering it a useful pre-procedural rinse in dentistry

and healthcare (8).

Alcohol-based solutions

These ethanol solutions achieve the disruption of

the lipid envelope bilayer around the virus; furthermore, ethanol

can facilitate protein denaturation inside the virus. SARS-CoV-2

and various other enveloped viruses can become deactivated with

solutions containing >60% alcohol for less than half a second or

instant (18,23). Such fluids are frequently

implemented for hand sanitizer disinfections; these same solutions

have a low utilization in mucous membranes.

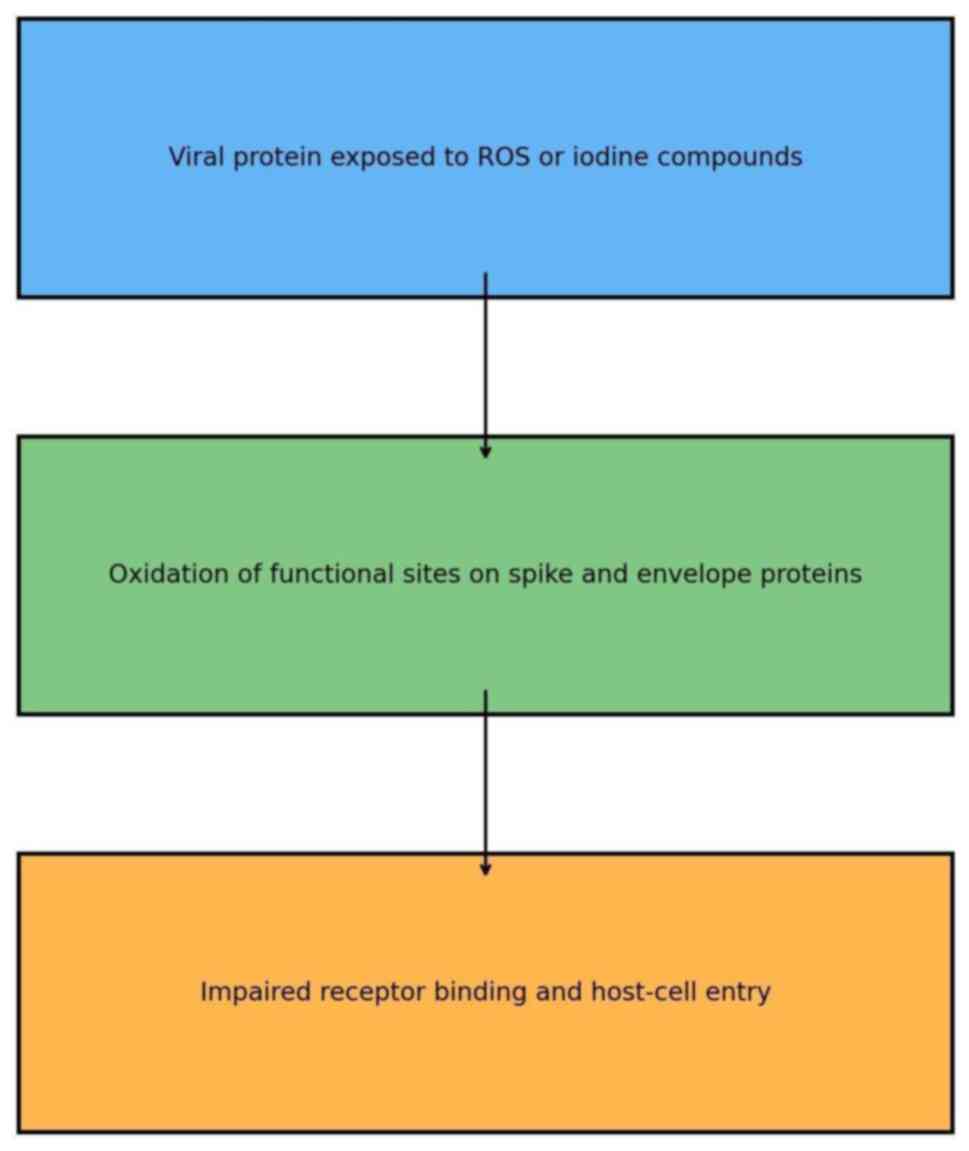

Protein oxidation

Surface proteins, such as the SARS-CoV-2 spike

protein mediate host-cell entry; the oxidation of these proteins is

now known to block viral infection (Fig. 2).

PVP-I. PVP-I rapidly oxidizes viral surface

proteins, thereby neutralizing them and preventing viral attachment

to host cells. Hassandarvish et al (1) demonstrated that PVP-I reaches a 4-log

reduction in infectivity within 15 sec of exposure. Thus, this

speed renders PVP-I suitable for general oral hygiene use,

particularly in risk settings where the speed of viral inactivation

is necessary.

H2O2. H2O2 produces

volatile ROS that oxidizes viral proteins, thus hindering virus

penetration into host cells. In their systematic review, Ortega

et al (16) suggested that

1.5-3% H2O2 reduces the infectivity of

viruses by as much as 80% within a period of 30-60 sec.

CHX. By rupturing the viral envelope, CHX

helps to inactivate viral proteins even though it does not directly

oxidize them. The viral surface proteins, including the spike

protein, are disrupted; thus, the virus cannot bind to host cells.

This action accentuates its general antiviral action (9).

Membrane disruption

Of note, apart from protein oxidation, some agents

such as PVP-I and CPC can affect the lipid envelope of viruses

causing structural instability that enhances viral inactivation.

Such disruption can supplement protein oxidation, leading to a

greater extent of reduction in infectivity of the virus (31).

Viral load reduction

Antiviral mouthwashes are critical in reducing viral

loads in the oral cavity, minimizing the risk of transmission,

particularly in high-risk environments such as clinical and dental

settings.

PVP-I and CPC. Both are effective in

achieving rapid and significant reductions in viral loads. PVP-I,

as a pre-procedural rinse can reduce the salivary viral loads by

>99%; effects can be observed up to 30 min post-rinse (1,18).

Similarly, CPC provides comparable effectiveness and confers

anti-inflammatory benefits; thus, it can be considered as a good

option for oral hygiene in clinical as well as nonclinical

environments (31).

H2O2 and alcohol-based mouthwashes.

H2O2 must remain in contact for 1-2 min in

order to be able to reduce viral loads by 80%. Higher

concentrations will achieve this in a more rapid manner; however,

the residual activity would not last as long (16,22).

Alcohol-based mouthwashes compromise viral lipid envelopes, but

lack prolonged virucidal activity, requiring repeated use for

sustained viral reduction (23).

CHX. CHX has been shown to rapidly reduce

viral load in the oral cavity. In a systematic review, Rahman et

al suggested that 0.12% CHX solution decreased SARS-CoV-2 viral

load by 99.9% within 30 sec (32).

This renders CHX an excellent choice for pre-procedural rinses

(Fig. 3), which help to reduce

viral transmission in dental and healthcare settings (32).

Anti-inflammatory effects

Antiviral mouthwashes are indispensable in lowering

viral loads within the oral cavity, thus markedly reducing the

inflammatory mediators by indirectly decreasing the stimulus to the

inflammatory cells (2).

CPC. CPC suppresses pro-inflammatory

cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α by reducing the viral load. This

will thereby reduce both oral cavity site-specific inflammation, as

well as the associated systemic inflammation. Onozuka et al

(33) reported that the regular

use of CPC enhances promotes the recovery of patients from mild and

moderate COVID-19 symptoms (5,33).

Phthalocyanine derivatives. These derivatives

scavenge ROS, thus averting morbidity through the inhibition of

pro-inflammatory cytokines production. Vilhena et al

(6) demonstrated its efficacy in

reducing oral inflammation in patients with COVID-19, pointing

towards increasing their role in high-risk hospital setups. The key

feature is its antiviral action that also has role in reducing the

inflammatory burden, which provides great value to patients that

have immunocompromised states (6).

CHX. CHX reduces oral inflammation. It can

improve oral health in patients with symptomatic COVID-19 by

reducing gingival inflammation and bacterial load. This helps

patients with systemic diseases, such as diabetes, where

inflammation can accelerate disease progression (9,10,26).

The anti-inflammatory effects of CPC, CHX and phthalocyanine

derivatives have effects beyond oral health due to reduction in

viral load, contributing to the systemic benefits of reduced

complications, such as cytokine storms and secondary infections in

patients with viral infections, such as COVID-19.

Applications during the COVID-19

pandemic

Among the various mouthwashes, PVP-I at

concentrations between 0.2 to 2.5% has been observed to

significantly decrease up to 99.99% of SARS-CoV-2 particles with an

incubation period of <15 sec following its application (1,18).

Due to its potent virucidal effect, PVP-I is the preferred

pre-procedural oral rinse for several types of healthcare settings,

particularly in dental practices where aerosol-generating

procedures are inevitable, resulting in a higher risk of airborne

transmission of viruses (18).

Furthermore, the study conducted by Choudhury et al

(11) also established that PVP-I

mouthwashes decrease nasopharyngeal viral loads and help decrease

secondary transmission in patients, particularly those who are mild

or asymptomatic carriers. Additionally, the adaptability of PVP-I,

which also has wide-range effectiveness against other viruses

including Enteroviruses and Coxsackieviruses, has been further

justified as a management agent for the future viral pandemic

outbreak (34). Other

formulations, including CPC and chlorhexidine, were also found to

be helpful during the pandemic and found a niche in medical and

dental care, where CPC was shown to be particularly useful. CPC

mouthwashes have been shown to decrease viral titers and also

effective for aerosol-generating procedures (5). CHS is another antiviral agent that

has been strongly indicated as effective in combating the pandemic.

Jain et al (8) reported

that CHX mouth rinse may significantly reduce the levels of

SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the oral cavity. CHX mouthwashes were widely used

in aerosol-generating procedures in dental and healthcare settings,

primarily to decrease viral loads (8). In addition, the use of CHX as a

topical antimicrobial agent, as reported by Huang and Huang

(26), led to the reduction in

inflammatory burden caused by viral infections, thus contributing

to a more rapid recovery in patients with COVID-19(26). The pandemic also witnessed the

emergence of novel antiviral agents, including phthalocyanine-based

mouthwashes, which have been demonstrated to significantly reduce

viral loads and inflammation (6).

These formulations, which are used in critical care settings, were

incorporated into infection control plans with other antiviral

treatments to maximize protection (6,20).

Zinc-based and chlorhexidine solutions, which have broad-spectrum

antimicrobial activity, were applied to further limit the spread of

viruses, particularly in nasopharyngeal areas, by inhibiting viral

replication (28,35).

3. Challenges, limitations and future

directions

Although antiviral mouthwashes have demonstrated

their utility, they are not free of challenges as regards their

widespread use. A major hindrance is that the formulations vary,

and so do the designs of studies conducted, which makes it

challenging to standardize procedures for testing their efficacy.

For example, some compositions are deactivated by saliva or organic

matter when applied in practice, which could lower their

effectiveness during real-time application (3,36).

Another limitation is the long-term safety profile of oral

antiseptics. CPC-containing mouthwashes alter the oral microbiome,

leading to a possible risk of dysbiosis and poor oral health

(13). Likewise, CHX formulations

may cause taste impairment and tooth discoloration. According to

Jain et al (8), future

formulations require a balance of efficacy and minimal oral

disruption friendly to the microbiome. Long-term clinical trials

are required to evaluate the systemic impact of these formulations

(37). One other less commonly

used mouthwash is Chlorine dioxide, that has been proven to be

effective in reducing viral load (38). User compliance is also an issue.

Taste, cost and accessibility are the factors that prevent regular

use, particularly outside clinical settings. Educational programs

emphasizing the role of mouthwashes in infection control, along

with palatable formulations, will enhance adoption. Public

education programs, particularly for preprocedural mouth rinsing in

high-risk settings such as dental offices, will lead to further

increased use (34). Mouthrinses

have short-term advantages; however, their place in more

comprehensive infection control practices will be better understood

with further research. Researchers are investigating newer

formulations as possible remedies for these issues; these

formulations have improved efficacy, longer duration of action and

fewer side-effects.

Enzyme-based mouthwashes

These mouthwashes use lysozyme and proteases to

break down viral structures. The ability to neutralize feline

coronaviruses, a model for SARS-CoV-2, was shown by Buonavoglia

et al (14).

Nanoparticle-infused mouthwashes

Silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles, for example,

are used in mouthwashes to provide broad-spectrum antiviral action.

Zinc oxide may protect existing formulations by interfering with

viral replication (14).

Biofilm-targeting mouthwashes

Overcoming a significant limitation of conventional

mouthwashes, biofilm-targeting mouthwashes, such as solutions

infused with lactoferrin, aid in preventing viral adhesion to oral

tissues.

Smart pH-responsive formulations

These change their acidity when viruses are

detected, helping them function for longer periods of time to kill

viruses. The long-term virucidal activity is sustained by

pH-responsive CPC and CHX solutions, according to Rius-Salvador

et al (30). Future

research is required to focus on maintaining antiviral potency in

the presence of organic matter, possibly through zinc-based

antivirals combined with phthalocyanine derivatives. Further

optimization of efficacy while minimizing adverse effects could be

achieved by pairing CHX with anti-inflammatory agents and

optimizing CHX concentration (8).

To assess efficacy across various populations and healthcare

environments, further varied clinical trials are required. As these

advanced formulations develop, their integration into routine

infection control policies will necessitate additional validation.

Antiviral mouthwashes may reinforce masks, physical distance and

ventilation. Their widespread implementation in preprocedural

medical settings has the potential to significantly improve patient

safety and contribute to the long-term prevention of infectious

diseases.

4. Conclusion

Antiviral mouthwashes are an integral, yet

developing tool for preventing infections, particularly in dental

and medical settings. While existing formulations successfully

reduce viral loads, issues such as temporary efficacy, microbiome

impact and compliance barriers must be addressed. Improving the

stability of the formulation and creating designs that are easy for

patients to use are crucial steps towards making them really

useful.

In the future, standard clinical testing and

innovative formulation approaches will be integral to incorporating

mouthwashes in routine infection control practices. Given the

progress to date and potential for continued improvements, these

could become an increasingly accepted preventive tool, both to

augment existing prevention strategies in daily practice and

prepare for future pandemics.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

OT wrote the original draft of the manuscript, and

conducted the literature search. GK conceptualized the study. SB

performed the literature review. PLR supervised the study and

edited and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hassandarvish P, Tiong V, Mohamed NA,

Arumugam H, Ananthanarayanan A, Qasuri M, Hadjiat Y and Abubakar S:

In vitro virucidal activity of povidone iodine gargle and mouthwash

against SARS-CoV-2: Implications for dental practice. Br Dent J:

Dec 10, 2020 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

2

|

Schürmann M, Aljubeh M, Tiemann C and

Sudhoff H: Mouthrinses against SARS-CoV-2: Anti-inflammatory

effectivity and a clinical pilot study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

278:5059–5067. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rodríguez-Casanovas HJ, De la Rosa M,

Bello-Lemus Y, Rasperini G and Acosta-Hoyos AJ: Virucidal activity

of different mouthwashes using a novel biochemical assay.

Healthcare (Basel). 10(63)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Carrouel F, Valette M, Gadea E, Esparcieux

A, Illes G, Langlois ME, Perrier H, Dussart C, Tramini P, Ribaud M,

et al: Use of an antiviral mouthwash as a barrier measure in the

SARS-CoV-2 transmission in adults with asymptomatic to mild

COVID-19: A multicentre, randomized, double-blind controlled trial.

Clin Microbiol Infect. 27:1494–501. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Takeda R, Sawa H, Sasaki M, Orba Y, Maishi

N, Tsumita T, Ushijima N, Hida Y, Sano H, Kitagawa Y and Hida K:

Antiviral effect of cetylpyridinium chloride in mouthwash on

SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep. 12(14050)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Vilhena FV, Brito Reia VC, da Fonseca

Orcina B, Santos CA, Zangrando M, Cardoso de Oliveira R and da

Silva Santos PS: The use of antiviral phthalocyanine mouthwash as a

preventive measure against COVID-19. GMS Hyg Infect Control.

16(Doc24)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Martínez Lamas L, Diz Dios P, Pérez

Rodríguez MT, Del Campo Pérez V, Cabrera Alvargonzalez JJ, López

Domínguez AM, Fernandez Feijoo J, Diniz Freitas M and Limeres Posse

J: Is povidone iodine mouthwash effective against SARS-CoV-2? First

in vivo tests. Oral Dis. 28 (Suppl 1):S908–S911. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Jain A, Grover V, Singh C, Sharma A, Das

DK, Singh P, Thakur KG and Ringe RP: Chlorhexidine: An effective

anticovid mouth rinse. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 25:86–88.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Fernandez MDS, Guedes MIF, Langa GPJ,

Rösing CK, Cavagni J and Muniz FWMG: Virucidal efficacy of

chlorhexidine: A systematic review. Odontology. 110:376–392.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Perussolo J, Teh MT, Gkranias N, Tiberi S,

Petrie A, Cutino-Moguel MT and Donos N: Efficacy of three

antimicrobial mouthwashes in reducing SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the

saliva of hospitalized patients: A randomized controlled pilot

study. Sci Rep. 13(12647)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Choudhury MIM, Shabnam N, Ahsan T, Kabir

MS, Khan RM and Ahsan SMA: Effect of 1% povidone iodine

mouthwash/gargle, nasal and eye drop in COVID-19 patient. Biores

Commun. 7:919–23. 2021.

|

|

12

|

Arefin MK, Rumi SKNF, Uddin AKMN, Banu SS,

Khan M, Kaiser A, Chowdhury JA, Khan MAS and Hasan MJ: Virucidal

effect of povidone iodine on COVID-19 in the nasopharynx: An

open-label randomized clinical trial. Indian J Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg. 74 (Suppl 2):S2963–S2967. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Weber J, Bonn EL, Auer DL, Kirschneck C,

Buchalla W, Scholz KJ and Cieplik F: Preprocedural mouthwashes for

infection control in dentistry-an update. Clin Oral Investig. 27

(Suppl 1):S33–S44. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Buonavoglia A, Camero M, Lanave G, Catella

C, Trombetta CM, Gandolfi MG, Palazzo G, Martella V and Prati C:

Virucidal activity in vitro of mouthwashes against a feline

coronavirus type II. Oral Dis. 28 (Suppl 2):S2492–S2499.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Elzein R, Abdel-Sater F, Fakhreddine S,

Abi Hanna P, Feghali R, Hamad H and Ayoub F: In vivo evaluation of

the virucidal efficacy of chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine

mouthwashes against salivary SARS-CoV-2. A randomized-controlled

clinical trial. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 21(101584)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ortega KL, Rech BD, El Haje GL, Gallo CD,

Pérez-Sayáns M and Braz-Silva PH: Do hydrogen peroxide mouthwashes

have a virucidal effect? A systematic review. J Hosp Infect.

106:657–662. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Chen MH and Chang PC: The effectiveness of

mouthwash against SARS-CoV-2 infection: A review of scientific and

clinical evidence. J Formos Med Assoc. 121:879–885. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Imran E, Khurshid Z, M Al Qadhi AA, A

Al-Quraini AA and Tariq K: Preprocedural use of povidone-iodine

mouthwash during dental procedures in the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J

Dent. 14:S182–S184. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Garcia-Sanchez A, Peña-Cardelles JF,

Salgado-Peralvo AO, Robles F, Ordonez-Fernandez E, Ruiz S and Végh

D: Virucidal activity of different mouthwashes against the salivary

load of SARS-CoV-2: A narrative review. Healthcare (Basel).

10(469)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kramer A, Eggers M, Hübner NO, Walger P,

Steinmann E and Exner M: Virucidal gargling and virucidal nasal

spray. GMS Hyg Infect Control. 16(Doc02)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Santos C, da Fonseca Orcina B, Brito Reia

VC, Ribeiro LG, Grotto RMT, Prudenciatti A, de Moraes LN,

Ragghianti Zangrando M, Vilhena FV and da Silva Santos PS:

Virucidal activity of the antiseptic mouthwash and dental gel

containing anionic phthalocyanine derivative: In vitro study. Clin

Cosmet Investig Dent. 13:269–274. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Moosavi MS, Aminishakib P and Ansari M:

Antiviral mouthwashes: Possible benefit for COVID-19 with

evidence-based approach. J Oral Microbiol.

12(1794363)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Mezarina Mendoza JPI, Trelles Ubillús BP,

Salcedo Bolívar GT, Castañeda Palacios RDP, Herrera Lopez PSG,

Padilla Rodríguez DA and Uchima Koecklin KH: Antiviral effect of

mouthwashes against SARS-COV-2: A systematic review. Saudi Dent J.

34:167–193. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Xu C, Wang A, Hoskin ER, Cugini C,

Markowitz K, Chang TL and Fine DH: Differential effects of

antiseptic mouth rinses on SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in vitro.

Pathogens. 10(272)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang M, Meng N, Duo H, Yang Y, Dong Q and

Gu J: Efficacy of mouthwash on reducing salivary SARS-CoV-2 viral

load and clinical symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMC Infect Dis. 23(678)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Huang YH and Huang JT: Use of

chlorhexidine to eradicate oropharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19

patients. J Med Virol. 93:4370–4373. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kuznetsova MV, Nesterova LY, Mihailovskaya

VS, Selivanova PA, Kochergina DA, Karipova MO, Valtsifer IV,

Averkina AS and Starčič Erjavec M: Nosocomial Escherichia coli,

klebsiella pneumoniae, pseudomonas aeruginosa, and staphylococcus

aureus: Sensitivity to chlorhexidine-based biocides and prevalence

of efflux pump genes. Int J Mol Sci. 26(355)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sánchez Barrueco Á, Mateos-Moreno MV,

Martínez-Beneyto Y, García-Vázquez E, Campos González A, Zapardiel

Ferrero J, Bogoya Castaño A, Alcalá Rueda I, Villacampa Aubá JM,

Cenjor Español C, et al: Effect of oral antiseptics in reducing

SARS-CoV-2 infectivity: Evidence from a randomized double-blind

clinical trial. Emerg Microbes Infect. 11:1833–1842.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Green A, Roberts G, Tobery T, Vincent C,

Barili M and Jones C: In vitro assessment of the virucidal activity

of four mouthwashes containing Cetylpyridinium Chloride, ethanol,

zinc and a mix of enzyme and proteins against a human coronavirus.

BioRxiv: 2020-10, 2020.

|

|

30

|

Rius-Salvador M, García-Múrria MJ, Rusu L,

Bañó-Polo M, León R, Geller R, Mingarro I and Martinez-Gil L:

Cetylpyridinium chloride and chlorhexidine show antiviral activity

against Influenza A virus and Respiratory Syncytial virus in vitro.

PLoS One. 19(e0297291)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Saud Z, Tyrrell VJ, Zaragkoulias A, Protty

MB, Statkute E, Rubina A, Bentley K, White DA, Rodrigues PDS,

Murphy RC, et al: The SARS-CoV2 envelope differs from host cells,

exposes procoagulant lipids, and is disrupted in vivo by oral

rinses. J Lipid Res. 63(100208)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Rahman GS, Alshetan AAN, Alotaibi SSO,

Alaskar BMI and Baseer MA: Is chlorhexidine mouthwash effective in

lowering COVID-19 viral load? A systematic review. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 27:366–377. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Onozuka D, Takatera S, Matsuo H, Yoshida

H, Hamaguchi S, Yamamoto S, Sada RM, Suzuki K, Konishi K and

Kutsuna S: Oral mouthwashes for asymptomatic to mildly symptomatic

adults with COVID-19 and salivary viral load: A randomized,

placebo-controlled, open-label clinical trial. BMC Oral Health.

24(491)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ang WX, Tan SH, Wong KT, Perera D,

Kuppusamy UR and Ong KC: Antiviral activity of povidone-iodine

gargle and mouthwash solution against Enterovirus A71,

Coxsackieviruses A16, A10 and A6. Trop Biomed. 41:241–250.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Vergara-Buenaventura A and Castro-Ruiz C:

Use of mouthwashes against COVID-19 in dentistry. Br J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 58:924–927. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Verma SK, Dev Kumar B, Chaurasia A and

Dubey D: Effectiveness of mouthwash against viruses: 2020

Perspective. A systematic review. Minerva Dent Oral Sci.

70:206–213. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Jaiyesimi R, Oyeniyi S and Bosun-Arije F:

The potential benefit of mouthwashes in reducing COVID-19 viral

load: A mini review. Proc Niger Acad Sci 13: ISSN 0794-7976,

2020.

|

|

38

|

Avhad SK, Bhanushali M, Sachdev SS, Save

SS, Kalra D and DN K: Comparison of effectiveness of chlorine

dioxide mouthwash and chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash in

reduction of oral viral load in patients with COVID-19. Indian J

Public Health Res Deve. 11:27–32. 2020.

|