1. Introduction

The escalating issue of meat inflation, the

increasing global population and the need for a nutritionally

balanced diet, while minimizing greenhouse gas emissions have all

contributed to a surge in demand for protein from plant sources.

Since the primary protein sources are derived from animals and the

strain on current animal sources is deemed unsustainable, there is

an urgent need for novel, sustainable protein sources that are safe

and of high nutritional quality. Therefore, the food industry and

researchers are tasked with finding alternative protein sources and

production methods to satisfy consumer demand and anticipated

global protein needs.

While plant-based proteins are nutritionally

beneficial, they require land and water, which are becoming

increasingly scarce. Moreover, the conversion of plant proteins

into meat proteins is inefficient, requiring 6 kg of plant proteins

to produce 1 kg of meat proteins (1). Single-cell proteins, mainly composed

of dried cells (biomass) produced by algae, yeast, bacteria and

fungi, present a viable alternative to traditional protein sources

in this context (2). Microalgae,

unicellular photosynthetic organisms, are considered promising

alternative protein sources (3).

They can produce biomass and oxygen by harnessing sunlight as an

energy source, CO2 as a carbon source and inorganic

salts as a carbon supply (4).

Microalgae exist in freshwater, marine and edaphic

habitats, with some species also found in humid soils (5). Unlike conventional food crops,

microalgae can thrive in various conditions without requiring

arable land, thus not competing with crops, such as soybeans and

cereal grains (6).

The broad spectrum of microalgae includes

>100,000 species divided into four distinct groups:

Chlorophyceae (green algae), Bacillariophyceae (eukaryotic

diatoms), Chrysophyceae (golden algae) and Cyanophyceae (blue-green

algae) (7). Despite their vast

diversity, microalgae remain under-researched and poorly understood

(4). Researchers have found that

microalgae are an attractive source for developing beneficial

products with significant value in the cosmetics, food and

nutrition, medicinal and pollution-prevention sectors (8).

Chlorella spp. was the first algae discovered

and isolated in culture by Beijerinck (9). Of note >20 Chlorella

species have been identified, with >100 strains documented

(10). The exploration of the

dietary benefit of Chlorella on human health began in the

early 1950s when Chlorella was introduced as a food source

during a global food crisis (11).

It was first grown and consumed in Asia, mainly in Japan, before

gaining popularity as a nutritional supplement worldwide (12).

Chlorella spp. contains protein levels

similar to traditional protein sources such as meat, egg, soybean

and milk (3). Research has shown

that it contains 55-67% protein, 1-4% chlorophyll, 9-18% dietary

fiber, and various minerals and vitamins on a dry matter basis

(13). In particular, Chlorella

vulgaris is known to contain up to 58% protein on a dry weight

basis (14) and is considered safe

for human consumption by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in

the USA, along with other microalgae species, such as

Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina) due to their long history

of human consumption and nutrient profile (15). However, limited reports are

available on the protein content and quality of Chlorella

sorokiniana (C. sorokiniana) and its application in

food. Thus, the present review aimed to evaluate C.

sorokiniana biomass as an alternative ingredient for food. The

present review aimed to enhance the understanding of the biomass

characteristics, bioactive substances, functional components,

biomass-based food products, and health advantages linked to the

consumption of C. sorokiniana microalgae.

2. Review methodology and literature

selection

A systematic approach was utilized to select

pertinent literature from databases such as Scopus, Web of Science,

CrossRef, PubMed and Google Scholar to ensure a comprehensive

review. The search for articles included in the present review

involved utilizing specific key terms, such as ‘C.

sorokiniana Characteristics’, ‘Macronutrients in C.

sorokiniana’, ‘Protein Quality of C. sorokiniana’,

‘Micronutrients in C. sorokiniana’, ‘Bioactive compounds in

C. sorokiniana’, and ‘C. sorokiniana Food Products’.

Subsequently, the databases were used in conjunction with VOSviewer

software to conduct a bibliometric analysis (16). Articles were selected based on

various criteria, including their relevance to the topic and the

presence of substantial reviews or experimental data on C.

sorokiniana microalgae.

3. C. sorokiniana biomass

characteristics

C. sorokiniana, a freshwater green microalga,

is part of the Chlorophyta division. Initially, it was considered

to be a thermotolerant mutant of Chlorella pyrenoidosa

(17). However, chloroplast 16S

rDNA and 18S rRNA profiling in the late 1980s and early 1990s

identified C. sorokiniana as a separate species (10). This tiny, single-celled alga,

ranging in size from 2 to 4.5 µm in diameter, can grow

mixotrophically on various carbon and nitrogen sources, rendering

it ideal for waste feedstock cultivation (18).

This chlorophyte has several advantages over other

microalgae species. Previous studies have demonstrated that C.

sorokiniana can achieve optimal growth at temperatures ranging

from 35 to 40˚C (19), with

phototrophic doubling times as short as 4-6 h (20). It can also grow under harsh

conditions, including wastewater or heavy metal wastes (21). It has been reported to have a more

rapid growth in mixotrophic and even heterotrophic conditions, with

a preference for sugars, such as glucose or simple organic acids,

such as acetate (22).

The typical physicochemical composition and

biological value (BV) indicators of the dry biomass of C.

sorokiniana, obtained by cultivation in a pilot bioreactor, are

presented in Tables I and II. The dry biomass of C.

sorokiniana contains an average of 48% protein, which is

markedly higher than that of soy, peanut, wheat germ and other

animal sources such as beef, fish and chicken (23,24).

The lipid content of the biomass sample is 13-22%, comparable to or

slightly higher than that of other aquacultures, such as

Spirulina spp (25). The

biomass is rich in physiologically active phytochemicals, the most

abundant of which are chlorophylls (22.13 mg/g dry biomass) and

carotenoids (6.04 mg/g dry biomass) (23) (Table

III). C. sorokiniana consists of 30-38% carbohydrates on

a dry weight basis (26), which is

higher than that C. vulgaris, with ~15% carbohydrate content

on a dry basis (27).

| Table IPhysicochemical characteristics of

Chlorella sorokiniana on a dry basis. |

Table I

Physicochemical characteristics of

Chlorella sorokiniana on a dry basis.

| Components | Content |

|---|

| Appearance,

dry | Free-flowing

powder |

| Color, dry | Green |

| Taste and

smell | Fishy,

characteristic of algae |

| External

admixtures | Absent/none |

| Moisture content,

% | 4% |

| Protein, g/100 g

dry biomass | 47.82±2.30 |

| Lipids, g/100 g dry

biomass | 17.50±4.50 |

| Carbohydrates,

g/100 g dry biomass | 30.00±4.00 |

| Minerals, mg | 4.36±0.56 |

| Table IIIndicators of the biological value

(BV) of the dry biomass of Chlorella sorokiniana

microalgae. |

Table II

Indicators of the biological value

(BV) of the dry biomass of Chlorella sorokiniana

microalgae.

| Polyunsaturated

fatty acids (PUFAs) | Concentration

(mg/g) | Carbohydrates

(sugars) | Concentration

(mg/g) | Phytochemicals | Concentration

(mg/g) |

|---|

| ω3 | 26.6±1.16 | Sucrose | 204.0±2.00 | Chlorophyll | 22.13±2.20 |

| Eicosapentanoic

acid | 0.53±0.02 | | | | |

| α-linolenic

acid | 16.1±0.60 | Glucose | 133.0±1.20 | Phenolic

compounds | 0.05±0.02 |

| Docosahexaenic

acid | 10.0±0.20 | | | | |

| ω6 | 25.7±1.00 | Xylose | 58.0±0.50 | Carotenoids | 6.04±0.60 |

| E-linoleic

acid | 3.3±0.05 | | | | |

| Z-linoleic

acid | 14.8±0.50 | Fructose | 20.0±0.30 | Organic acids | 2.70±0.40 |

| Octadecatrienoic

acid | 7.5±0.10 | | | | |

| Table IIIPER, BV, NPU and DC of various

protein sources. |

Table III

PER, BV, NPU and DC of various

protein sources.

| Protein

sources | PERa | BVa | NPUa | DCa |

|---|

| Beef | 116.0 | 103.9 | 96.1 | 100.0 |

| Soy protein | 88.0 | 96.1 | 80.3 | 99.0 |

| Wheat

gluten/cereal | 32.0 | 83.1 | 88.2 | 91.9 |

| Chlorella

spp. | 80.0 | 87.2 | 81.5 | 93.6 |

Factors such as temperature, nutritional composition

and light availability can influence the quantities of biomass,

macro- and micronutrients, and other useful bioactive substances,

including antioxidants, in Chlorella cells (28).

4. Macronutrients in C. sorokiniana

biomass

The average macronutrient content of C.

sorokiniana biomass based on previous studies (23,31,32)

is summarized in Table IV. The

analysis of C. sorokiniana dry biomass has revealed that it

contains an average of 45% protein, which is much greater than the

protein content of foods such as peanut (26%), wheat germ (27%) and

other animal sources, such as beef (22%), fish (22%) and chicken

(24%) (23,24,33).

| Table IVMacronutrient content of Chlorella

sorokiniana biomass on a dry basis. |

Table IV

Macronutrient content of Chlorella

sorokiniana biomass on a dry basis.

| Macronutrients | Content (g/100 g

dry weight) |

|---|

| Proteins | 44.75±1.88 |

| Lipids | 16.42±5.18 |

| Carbohydrates | 37.61±1.81 |

The essential amino acid composition of C.

sorokiniana biomass is presented in Table V. Notably, these amino acid

profiles, which mammals do not synthesize, are present in notable

concentrations in C. sorokiniana microalgae; thus, when

compared to the recommendations of the World Health Organization

for the use of essential amino acids in food, this microalga could

be used in the food industry (32). The high protein content and

favorable amino acid composition of C. sorokiniana

microalgae suggest that this microalga may serve as a potential

protein source.

| Table VEssential amino acid composition of

Chlorella sorokiniana microalgae. |

Table V

Essential amino acid composition of

Chlorella sorokiniana microalgae.

| Essential amino

acid | Content (mg/g) |

|---|

| Histidine | 6.1±0.60 |

| Threonine | 19.0±2.20 |

| Isoleucine | 4.53±0.04 |

| Valine | 20.0±1.20 |

| Methionine | 1.8±0.20 |

| Tryptophan | 0.2±0.02 |

| Phenylalanine | 18.0±1.00 |

| Leucine | 30.0±2.10 |

| Lysine | 21.0±1.60 |

According to Gouveia and Oliveira (25), the lipid content of C.

sorokiniana biomass on a dry basis ranges from 11.24-21.6% dry

matter. It is equivalent to or slightly higher than other

aquacultures, such as Spirulina spp. (4-9% dry matter). As

shown in Table VI, ~80% of the

total fatty acid content of C. sorokiniana lipids is

polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (23). Since this microalga biomass

contains sufficient amounts of omega-3 PUFAs (~25-28% of total

fatty acids) and omega-6 PUFAs (~25-27% of total fatty acids), it

can effectively prevent and treat several diseases. Indeed, omega-3

PUFAs, such as alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, C18:3), eicosapentaenoic

acid (EPA, C20:5), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, C22:5) and

docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6) are effective in preventing or

treating cardiovascular disorders (34), lowering hypertension (35) as well as preventing cancer

(36,37), type 2 diabetes (38), inflammatory bowel disorder

(39), asthma (13), arthritis (40), kidney and skin disorders (38,39),

depression (13) and schizophrenia

(41). Furthermore, due to its

lipid composition, C. sorokiniana may also play an essential

function in preventing atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolemia and

tumors (40).

| Table VIPUFAs and carbohydrates in

Chlorella sorokiniana microalgae dry biomass. |

Table VI

PUFAs and carbohydrates in

Chlorella sorokiniana microalgae dry biomass.

| Components | Content (mg/g dry

weight) |

|---|

| PUFAs | |

|

Alpha-linolenic

acid (ALA) | 16.1±0.60 |

|

Eicosapentanoic

acid (EPA) | 0.53±0.02 |

|

Docosahexaenoic

acid (DHA) | 10.0±0.20 |

|

Total

omega-3 | 26.6±1.16 |

|

E-linoleic

acid (LA) | 3.3±0.05 |

|

Z-linoleic

(LA) | 14.8±0.50 |

|

Octadecatrienoic

acid | 7.5±0.10 |

|

Total

omega-6 | 25.7±1.00 |

| Carbohydrates | |

|

Sucrose | 204.0±2.00 |

|

Glucose | 133.0±1.20 |

|

Xylose | 58.0±0.50 |

|

Fructose | 20.0±0.30 |

Another key class of macronutrient substances found

in the hydrophilic fraction of C. sorokiniana microalgae

biomass comprises carbohydrates. Effectively, 36-39% dry weight of

carbohydrates found in C. sorokoniana microalgae biomass are

found in the form of sucrose, glucose, xylose and fructose

(23,31,42).

Moreover, the cell wall of C. sorokinana is also composed of

many insoluble polysaccharides, primarily mannose and glucose

(43). Polysaccharides are

polymeric carbohydrate structures commonly employed in the food

industry (44). Owing to their

high polysaccharide concentration, microorganisms such as

Chlorella microalgae have been actively investigated in the

search for novel natural antioxidants (44,45).

In the study by Pugh et al (46), immurella polysaccharides, a high

molecular weight polysaccharide, were isolated from C.

sorokiniana, which presented a higher activity against cancer.

Polysaccharides derived from C. sorokiniana microalgae have

also been shown to exhibit substantial antioxidant, tumor-fighting,

immunomodulatory characteristics, and the ability to remove

superoxide and hydroxyl peroxide radicals (47).

5. Protein quality of C. sorokiniana

biomass

The considerable protein content of C.

sorokiniana has positioned it as a promising alternative

protein source. The protein content in microalgae is typically

determined by measuring the total nitrogen and multiplying it by

the factor Nx6.25(48).

Experimentally determined N-protein factors for specific microalgal

species range from Nx3.06 to 5.95 (49,50).

This variation in the N-protein factor is attributed to non-protein

nitrogen, which comprises up to ~10% of the nitrogen in microalgae

and includes substances, such as amines, glucosamines, nucleic

acids and cell wall components (48).

Of note, four important quality parameters are

considered to assess the nutritional value of algal protein:

Protein efficiency ratio (PER), BV, digestibility coefficient (DC)

or true digestibility, and net protein utilization (NPU) (14). PER is a fundamental method for

evaluating protein quality, involving animal feeding trials with

weanling rats throughout 3 to 4 weeks (48). It measures the weight gain per unit

of protein consumed, expressed as PER=weight gain (g)/protein

intake (g) (48).

BV, another metric for assessing protein quality, is

based on the proportion of retained nitrogen to absorbed nitrogen

(48). The calculation for BV is

BV=[I-(F-F0)-(U-U0)]/[I-(F-F0)], where I represents nitrogen

intake, F is fecal nitrogen, U is urinary nitrogen, and F0 and U0

are the amounts of fecal and urinary nitrogen excreted when animals

are fed a nitrogen-free or low-nitrogen diet (51).

DC, also known as real digestibility, is another

indicator of protein quality. It reflects the proportion of meal

nitrogen absorbed by the animal and is calculated using the same

parameters as BV: DC=[I-(F-F0)]/I (48). NPU, on the other hand, is

determined by dividing nitrogen retained by nitrogen intake. The

measure of both digestibility and BV is provided by the NPU, which

is calculated using the formula NPU=(B-Bk)/I. Herein, B represents

the body nitrogen assessed at the end of the test period in animals

fed the test food. Bk represents the body nitrogen measured in

another group of animals fed a protein-free or low-protein diet

(48).

A comparison between Chlorella spp.

microalgae and traditional protein sources based on four quality

parameters (PER, BV, DC and NPU) is presented in Table III. The values in the table were

compared to casein, the primary protein found in milk, which serves

as a reference for scoring. Overall, the values presented in

Table III indicate that the

nutritional value of Chlorella spp. algal protein is lower

than that of beef and casein. However, it is comparable to that of

soy protein and superior to that of wheat gluten (52).

Amino acid composition

Protein quality can vary significantly based on the

digestion and the availability of essential amino acids (EAAs)

(53). Animal protein sources are

often considered complete proteins as they contain a high

concentration of EAAs that the human body cannot synthesize

(3). By contrast, plant proteins

are frequently observed as incomplete protein sources as they may

lack one or more EAAs, such as histidine, isoleucine, leucine,

lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan and valine

(54). For example, soy protein,

which is increasingly popular in the human diet, is deficient in

methionine, an essential antioxidant in the body (55). However, the specific EAAs acids

lacking in plant-based proteins can vary. Therefore, consuming a

varied diet of plant proteins from fruits, vegetables, grains and

legumes can provide an adequate quantity of all EAAs (56).

Plant-based proteins are often more challenging to

digest than animal proteins due to differences in their protein

structure (57). Plant-based

proteins have a higher proportion of β-sheet conformation and a

relatively lower α-helix conformation than animal proteins

(58). The high concentration of

β-sheet conformation in plant proteins renders them more resistant

to proteolysis in the gastrointestinal system, reducing their

digestibility (58). Additionally,

plant-based sources may contain non-starch polysaccharides or

fibers that hinder enzyme access to proteins and can further reduce

protein digestion (59).

Despite these differences, there is an increasing

concern about the high levels of saturated fats and cholesterol

present in animal-derived foods, which have been linked to

cardiovascular disease and diabetes. As a result, nutritionists and

organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

recommend a diverse diet rich in plant-based proteins (60).

Analyzing the amino acid composition is crucial for

understanding the value of food raw materials. Algae, including

microalgae such as Chlorella spp. and Spirulina spp.,

are widely recognized as viable protein sources with EAA

compositions that meet the FAO standards (61,62).

WHO/FAO/UNU has recommended these microalgae species for their

adequate EAA content for human consumption (62). Microalgae, including Chlorella

spp., have been found to contain amino acids, such as

isoleucine, valine, lysine, tryptophan, methionine, threonine and

histidine in amounts equivalent to or greater than protein-rich

sources, such as eggs and soybeans (33). Notably, the dry biomass of C.

sorokiniana microalgae provides all the amino acids necessary

for the growth and development of living organisms (Table III). Research has shown that the

quality of Chlorella products, including C.

sorokiniana (Table V), is high

based on the essential amino acid index, with values higher than

that of soybean protein (63).

These findings suggest that Chlorella proteins are of high

quality.

Microalgae protein digestibility

The FDA defines bioavailability as the rate and

extent to which the active ingredient is absorbed and becomes

accessible at the site of action. It encompasses the entire process

after consuming a food element, including its digestibility and

solubility in the gastrointestinal tract, absorption into the

circulatory system through intestinal epithelial cells, and

eventual incorporation into the target site of utilization

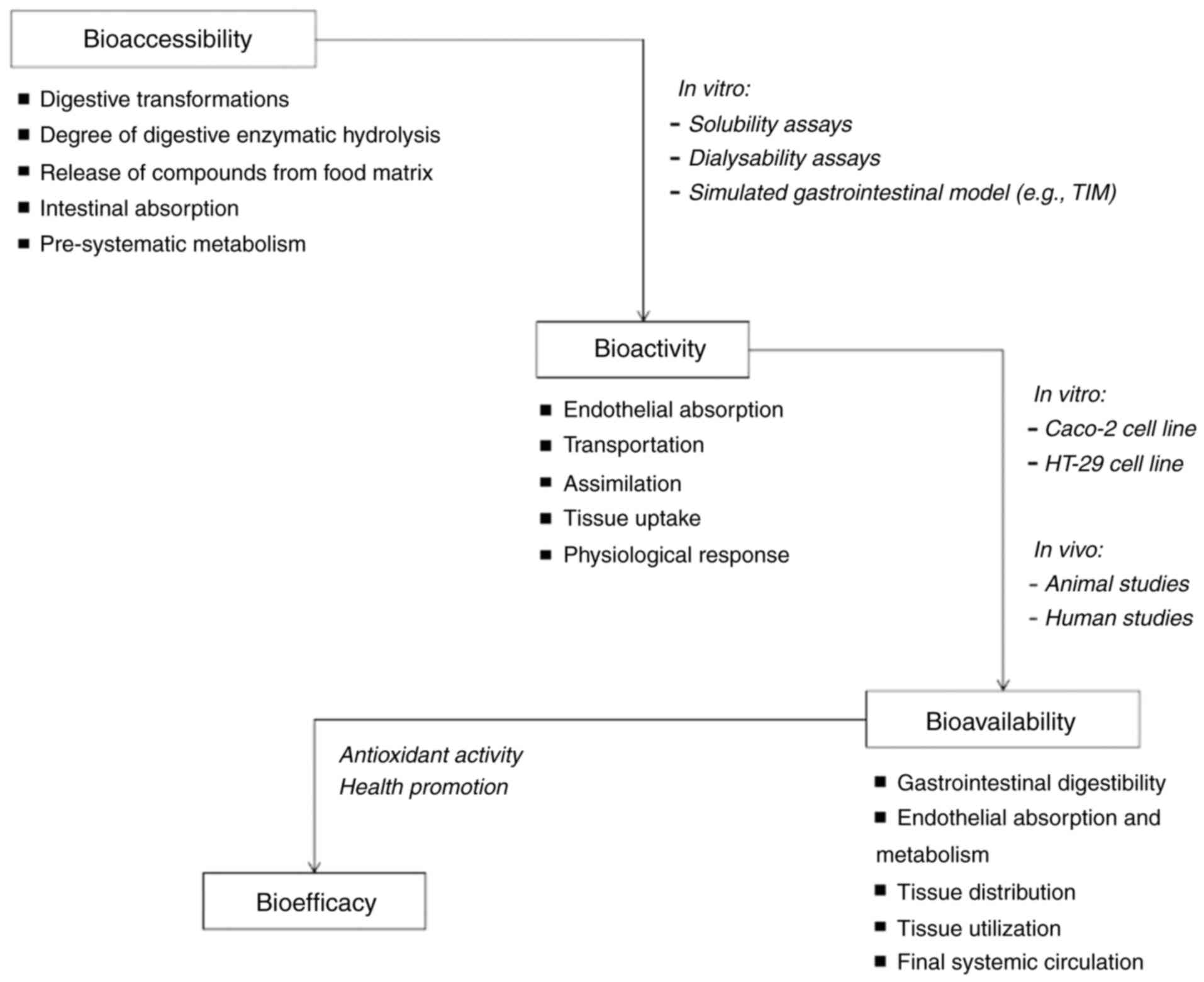

(Fig. 1). The bioavailability of

food nutrients is considered crucial for maintaining optimal

health. It also plays a crucial role in developing functional foods

and health claims based on food components, as understanding the

circulating metabolites and mechanisms of action is essential.

Bioavailability is further divided into two stages:

Bioaccessibility and bioactivity. Bioaccessibility refers to the

proportion of a component in a meal that is released from the food

matrix during digestion and becomes available for intestinal

absorption or undergoes biotransformation by gut bacteria (64). On the other hand, bioactivity

involves the assimilation of a food element across intestinal

cells, transport to the target site, interaction with the target

site, any necessary biotransformation, and the resulting

physiological response (65). The

activity of ingested substances or their metabolites in metabolic

pathways leads to biological effects on the body.

Several factors influence digestibility, rendering

in vitro research challenging. These factors include the

composition of macronutrients, enzyme specificity, anti-nutritional

substances, fiber content and variations in absorptive capabilities

along the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, unraveling the

bioavailability of food constituents is more complex than

pharmaceutical drugs due to the diverse nature of food compounds,

the various factors affecting their transition during digestion,

and the different absorption mechanisms for water-soluble and

lipid-soluble molecules (66).

In vitro research can be an initial screening technique to

identify potential food matrices, growing conditions, and

processing methods.

In addition to understanding the definition of the

two stages of bioavailability, it is crucial to define

digestibility to comprehend the metabolism dynamics of different

dietary matrices. Digestibility refers to the amount of nutrients

an individual absorbs and is typically calculated as the difference

between the nutrients ingested and the amount retained in

feces.

Assessing the potential of novel food sources

involves determining their biochemical composition. In vitro

and in vivo studies on digestibility, bioaccessibility and

bioavailability are crucial in gaining comprehensive knowledge

about nutrient interactions with food components. Such studies also

investigate the effects of pH and enzymes on absorbability,

providing insight into the potential nutrients that can be absorbed

(Fig. 1) (67). Therefore, understanding the

digestibility and bioaccessibility of algal compounds is essential

to maximize the potential of algal food products and

co-products.

Researching algal digestibility is particularly

critical, considering the complexity of the polysaccharide cell

wall. The cell wall composition of some algae, including

microalgae, typically consists of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin

compounds and glycoproteins (68).

These robust wall structures can restrict the accessibility of

digestive enzymes to intracellular algae compounds, limiting

nutrient and algae component bioaccessibility or bioavailability.

Extraction or pre-treatment procedures, such as enzymatic

hydrolysis or chemical, mechanical and physical approaches, can

promote cell disruption, enhancing algal nutrient digestibility and

bioaccessibility (69). Approaches

can encourage disruption cells, thereby enhancing algal nutrient

digestibility and bioaccessibility.

There are limited studies available in the

literature on microalgae digestibility, including investigations on

in vitro bioaccessibility, primarily due to the

aforementioned factors. However, certain microalgae species exhibit

distinct characteristics regarding digestibility. For instance,

Arthrospira platensis has a fragile cell wall, indicating

easily digestible biomass. On the other hand, Chlorophyta species

such as Chlorella vulgaris and Haematococcus

lacustris are tiny microorganisms (5-10 µm) with rigid cell

walls that require prior disruption to enhance the digestibility

and bioaccessibility of microalgal compounds (70).

A recent study conducted by Gómez-Jacinto et

al (71) focused on the in

vitro selenium bioaccessibility, in vivo bioavailability

and bioactivity of the Se-enriched microalga C. sorokiniana

for potential use as a functional food. The in vitro

gastrointestinal digestion of the selenized microalga demonstrated

81% bioaccessibility. In vivo experiments on mice treated

with Se-enriched C. sorokiniana revealed significant

selenium concentrations in the kidney, indicating a potential

excretion pathway through urine (71). This suggests that Se-enriched C.

sorokiniana can serve as a nutraceutical ingredient and a

dietary selenium supplement for humans.

When comparing the digestibility of traditional

protein sources, milk and eggs have the highest true digestibility

values, ~97% (72). They are

followed by meats, fish and poultry (73). By contrast, microalgae species such

as Scenedesmus obliquus, Arthrospira platensis

(Cyanobacteria), Spirulina sp. and Chlorella sp.

exhibit apparent DC values of 88.0, 86, 77.6 and 76.6%,

respectively (14,68).

6. Micronutrients in C. sorokiniana

biomass

Chlorella is an excellent source of vitamins

and minerals that adults and children can easily consume to meet

their daily vitamin requirements (12). As demonstrated in Table VII, C. sorokiniana

microalgae biomass contains the balanced mineral content required

in humans. In acceptable amounts, iron, copper and zinc are trace

elements necessary for the human body to function normally

(74). It is important to note

that C. sorokiniana biomass contains substantial amounts of

iron (18 mg/100 g dry weight) and zinc (20.2 mg/100 g dry weight),

of which adequate intake prevents anemia (75) and muscular weakness (76), respectively. Iron is required for

respiration, energy production, DNA synthesis and cell

proliferation (77). In previous a

study conducted by Nakano et al (78), oral Chlorella

supplementation (6 g/day) for 12-18 weeks lowered markers of anemia

in a cohort of 32 women in their second and third trimesters of

pregnancy compared to the control group. This suggests that

Chlorella supplementation considerably reduces the risk of

developing pregnancy-associated anemia (79).

| Table VIIMineral composition of Chlorella

sorokiniana dry biomass. |

Table VII

Mineral composition of Chlorella

sorokiniana dry biomass.

| Metals | Content (mg/100 g

dry weight) |

|---|

| Iron (Fe) | 18.00±2.00 |

| Copper (Cu) | 3.00±0.07 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 20.20±2.02 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 8.00±0.15 |

| Cobalt (Co) | 1.00±0.01 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 91.00±5.00 |

| Calcium (Ca) | 31.00±2.50 |

Moreover, some of the vitamins found in notable

quantities in Chlorella are vitamin A (in the form of

β-carotene), vitamin C, vitamin E, Vitamins K and vitamin B, such

as thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pantothenic acid

(B5), pyridoxine (B6), folic acid (B9) and cobalamin (B12)

(12,44). These vitamins fuel the body,

detoxify and restore digestive function, activate the immune system

and renew cells (44). Moreover,

the vitamin E content of green microalgae Chlorella

contributes to its high antioxidant activity (80,81).

7. Bioactive compounds in C.

sorokiniana biomass

Bioactive compounds are nutrients and non-nutrients

found in food (both plant and animal sources) that have

physiological effects in addition to their nutritional qualities

(82). Foods high in bioactive

chemicals that are routinely consumed positively impact human

health by performing antioxidant activity, reducing the risk of

developing diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, cancer,

cataracts and stroke (83,84). Microalgae are highly diverse and

contain significant bioactive compounds, including polyphenols,

carotenoids and organic acids, as presented in Table VIII.

| Table VIIIIndicators of the biological value of

Chlorella sorokiniana dry biomass. |

Table VIII

Indicators of the biological value of

Chlorella sorokiniana dry biomass.

|

Phyto-chemicals | Content (mg/g dry

weight) |

|---|

| Chlorophyll | 22.13±2.20 |

| Carotenoids | 6.04±0.60 |

| Total phenolic

compounds (GAE) | 12.27±2.31 |

| Total flavonoid

content (QE) | 15.05±3.83 |

Pigments are essential for the metabolism of

photosynthetic microalgae and have antioxidant, anti-carcinogenic,

anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-angiogenic and

neuroprotective properties in different metabolisms, including

human metabolism (44).

Chlorella contains substantial levels of chlorophyll,

similar to higher plants, although in markedly higher

concentrations than terrestrial plants, with the potential to

collect chlorophyll to a concentration of 2.5% (86). Chlorophyll is the principal natural

green pigment found in microalgae and plants, where it is needed

for oxygenic photosynthesis (87).

As presented in Table VIII,

C. sorokiniana biomass contains a notable amount of

biologically active phytochemicals, with chlorophylls (22.13 mg/g

dry biomass) dominating (23).

Azaman et al (88) also

discovered that under photoautotrophic conditions, C.

sorokiniana exhibited a total chlorophyll concentration of

24.37 µg/mg dry weight of the sample, which was more significant

than that of Chromochloris zofingiensis.

Carotenoid is a pigment in algae, plants, fungi and

bacteria that ranges in hue from yellow to red (84). It has health-promoting qualities

are mostly linked to its antioxidant activity that scavenges

singlet molecular oxygen and radicals (84). Previous research has shown that

carotenoids significantly contribute to the total antioxidant

capacity of microalgae (89,90).

In particular, Diprat et al (91) identified the carotenoid types

present in C. sorokiniana microalgae powder, which includes

violaxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, β-carotene and α-carotene. Using

high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to diode array and

mass spectrometry detectors, Fernandes et al (92) also identified 11 carotenoids in

C. sorokiniana, with the greatest significant quantities of

all-trans-lutein (831.18±1.18 g/g dry weight),

all-trans-β-carotene (156.21±0.22 g/g dry weight) and

all-trans-α-carotene (71.47±0.10 g/g dry weight). Indeed,

including C. sorokiniana biomass as a raw material in

functional foods will allow goods to be enriched with essential

nutritional components while obtaining the appropriate color range

without synthetic dyes (23).

Phenolic compounds, or polyphenolics, are abundant

secondary metabolites with antioxidant activity and numerous

biological functions that can be derived from microalgae (93). Due to their importance as one of

the most significant classes of natural antioxidants, phenolic

compounds are gaining popularity among consumers and food

manufacturers. They function as reducing agents and hydrogen

donors, capable of scavenging free radicals (94). Phenolic compounds have two basic

chemical structures formed by one or more aromatic rings with

hydroxyl (-OH) groups (93). They

are chemically classified into several classes, including phenolic

acids (hydroxybenzoic acids, hydroxycinnamic acids), flavonoids

(flavones, flavonols, flavanones, flavanonols, flavonols and

anthocyanins), isoflavonoids (isoflavones and coumestans),

stilbenes, lignans and phenolic polymers (proanthocyanidin)

(95).

Based on the Folin-Ciocalteu method, Olasehinde

et al (85) reported that

C. sorokiniana dry biomass contains a total phenolic content

of 12.27±2.31 gallic acid equivalent (GAE) mg/g, which is higher

compared to C. minutissima (10.53±2.82 GAE mg/g dry weight)

(Table VIII). Likewise, the

same authors revealed that C. sorokiniana dry biomass

contains a total flavonoid content of 15.05±3.83 quercetin

equivalent (QE) mg/g dry weight (85). Furthermore, Safafar et al

(96) also presented that C.

sorokiniana dry biomass contains 5.84±0.04 GAE mg/g total

phenolics and 2.45±0.04 QE mg/g total flavonoid content.

Furthermore, they found that C. sorokiniana, grown in

different light intensities, had the same phenolic acid profile

(96). Still, the total detected

phenolic acids in the sample grown in average light intensity was

somewhat higher. Thus, generating phenolics and other antioxidant

chemicals in microalgae depends on growth circumstances and

challenges such as oxidative stress (96).

Apart from having antioxidant properties, phenolic

compounds have therapeutic qualities such as anti-tumor and

antibacterial activities (84).

Chlorella phenolic chemicals may also prevent liver cell

carcinogenesis by blocking lipid peroxidation on the cell membrane,

neutralizing cellular free radicals and preventing DNA damage

(84).

8. C. sorokiniana biomass-based food

products

Given the abundance of nutrients and bioactive

substances found in C. sorokiniana, it is no surprise that

it can be regarded as one of the most promising new food and

functional goods sources. C. sorokiniana has a well-balanced

chemical composition and provides a source of beneficial bioactive

chemicals (13). As a result of

its potential, C. sorokiniana can represent an alternative

and novel source of natural components that can be used as

functional ingredients to improve the nutritional content of

foods.

Chlorella sp. has been extensively utilized

as a dietary supplement for an extended period of time. The

microalgal market offers Chlorella sp. in powder and tablet

forms, primarily due to its ability to effectively sequester heavy

metals, such as mercury, recognized as toxic substances, and

facilitate their elimination from the body (84). In recent times, there has been a

surge in research efforts focused on advancing food products

derived from C. sorokiniana biomass. Pasta (23) and gluten-free bread (91) have been incorporated with C.

sorokiniana biomass for baked food products.

Bazarnova et al (23) examined the effects of incorporating

the dry biomass of microalgae C. sorokiniana as a

replacement for flour mixture to enrich pasta effectively. In their

study, it was shown that flour replacement with C.

sorokiniana should not be >5% due to the formation of a

distinct fish flavor of the product. Moreover, substituting 5%

C. sorokiniana biomass to pasta flour increased proteins to

15.7±0.50% and lipids to 4.1±0.06%. Furthermore, the addition of

C. sorokiniana dry biomass to pasta has helped improve the

polyunsaturated fatty acids, chlorophyll and carotenoid content of

the product (23).

Diprat et al (91) also examined the partial replacement

of pea flour with C. sorokiniana powder at 2.5 and 5% to

increase the nutritional quality of gluten-free bread. The

replacement of 5% C. sorokiniana powder vs. the control with

pea flour increased the protein content (67 to 85 mg/g), lutein

content (1.6 to 57.5 µg/g) and omega-3 content in the fatty acids

(5.0-6.1%) of the gluten-free bread. Furthermore, it is interesting

to note that compared with the pasta food product studied by

Bazarnova et al (23), the

sensory analysis of the gluten-free bread with 5% replacement of

C. sorokiniana powder had an acceptance rate >70%, with

no observed distinct fishy flavor being identified. Furthermore,

the addition of C. sorokiniana powder had no effect on the

texture and specific volume of the bread product.

The expanding number of studies on Chlorella

as a food ingredient have revealed that Chlorella sp. has a

significant potential to be an alternative protein source and

future food. However, further product application of C.

sorokiniana biomass in food needs to be conducted in order to

assess its effects on the physicochemical, sensory,

techno-functional and antioxidant properties as a food ingredient.

Consumers also strongly demand food to prevent illness, improve

mental health and increase life quality, as well as a desire to

consume alternative proteins to be healthy and more sustainable. As

a result, the worldwide market for Chlorella ingredients is

predicted to expand and meet human nutritional requirements

(84).

9. Conclusions and future perspectives

C. sorokiniana microalgae has shown promise

as an alternative protein ingredient to meet the increasing demand

for sustainable food products. There is a growing consumer interest

and awareness regarding alternative protein sources, rendering the

use of microalgal protein in developing healthier food products

highly relevant. The high protein content, balanced amino acid

profiles and bioactive substances in C. sorokiniana make it

a potential dietary source with various health benefits. As

numerous high-value microalgae products are intended for human

consumption or other applications, they are subject to food laws

and regulatory standards set by organizations such as the FDA.

Collaborative efforts from researchers across disciplines are

necessary to expand the market for microalgal food products

further. These efforts should focus on identifying novel microalgae

species and their unique characteristics, developing more

cost-effective cultivation and biorefinery systems, improving the

sensory properties of microalgal food products and assessing the

availability of algal compounds.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude

to the DOST-SEI for providing the scholarship to JLZF (ASTHRDP) and

the collaborative project between DOST-PCAARRD and SEI for

supporting the scholarship of MSA (GREAT Program).

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JLZF and MSA performed the literature review. JLZF

and MSA wrote the manuscript. Furthermore, both authors have

thoroughly reviewed, and have read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Hertzler SR, Lieblein-Boff JC, Weiler M

and Allgeier C: Plant proteins: Assessing their nutritional quality

and effects on health and physical function. Nutrients.

12(3704)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Sharif M, Zafar MH, Aqib AI, Saeed M,

Farag MR and Alagawany M: Single cell protein: Sources, mechanism

of production, nutritional value and its uses in aquaculture

nutrition. Aquac. 531(735885)2021.

|

|

3

|

Bleakley S and Hayes M: Algal proteins:

Extraction, application, and challenges concerning production.

Foods. 6(33)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Bahi A, Ramos-Vega A, Angulo C,

Monreal-Escalante E and Guardiola FA: Microalgae with

immunomodulatory effects on fish. Rev Aquac. 15:1522–1539.

2023.

|

|

5

|

Schenk PM: Phycology: Algae for food,

feed, fuel and the planet. Phycol. 1:76–78. 2021.

|

|

6

|

Martins CF, Ribeiro DM, Costa M, Coelho D,

Alfaia CM, Lordelo M, Almeida AM, Freire JPB and Prates JAM: Using

microalgae as a sustainable feed resource to enhance quality and

nutritional value of pork and poultry meat. Foods.

10(2933)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Madeira MS, Cardoso C, Lopes PA, Coelho D,

Afonso C, Bandarra NM and Prates JAM: Microalgae as feed

ingredients for livestock production and meat quality: A review.

Livest Sci. 205:111–121. 2017.

|

|

8

|

Sathasivam R, Radhakrishnan R, Hashem A

and Abd Allah EF: Microalgae metabolites: A rich source for food

and medicine. Saudi J Biol Sci. 26:709–722. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Beyerinick MW: Cultivation experiments

with Zoochlorella, Lichengonidia, and other lower algae. Bot Ztg.

47:725–739, 741-754, 757-768, 781-785. 1890.http://img.algaebase.org/pdf/AC100CF003338161AAoHt43C4207/35049.pdf.

|

|

10

|

Wu HL, Hseu RS and Lin LP: Identification

of Chlorella spp. isolates using ribosomal DNA sequences. Bot Bull

Acad Sin. 42:115–121. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ortiz Montoya EY, Casazza AA, Aliakbarian

B, Perego P, Converti A and de Carvalho JC: Production of Chlorella

vulgaris as a source of essential fatty acids in a tubular

photobioreactor continuously fed with air enriched with

CO2 at different concentrations. Biotechnol Prog.

30:916–922. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Rani K, Sandal N and Sahoo PK: A

comprehensive review on chlorella-its composition, health benefits,

market and regulatory scenario. Pharma Innovation. 7:584–589.

2018.

|

|

13

|

Matos J, Cardoso C, Bandarra NM and Afonso

C: Microalgae as healthy ingredients for functional food: A review.

Food Funct. 8:2672–2685. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Becker EW: Microalgae as a source of

protein. Biotechnol Adv. 25:207–210. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ferdous UT, Nurdin A, Ismail S and Balia

Yusof ZN: Evaluation of the antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of

crude extracts from marine Chlorella sp. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol.

47(102551)2023.

|

|

16

|

van Eck NJ and Waltman L: Software survey:

VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping.

Scientometrics. 84:523–538. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kunz WF: Response of the alga Chlorella

sorokiniana to 60 Co gamma radiation. Nature. 236:178–179.

1972.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ramanna L, Guldhe A, Rawat I and Bux F:

The optimization of biomass and lipid yields of Chlorella

sorokiniana when using wastewater supplemented with different

nitrogen sources. Bioresour Technol. 168:127–135. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

de-Bashan LE, Trejo A, Huss VA, Hernandez

JP and Bashan Y: Chlorella sorokiniana UTEX. 2805, a heat and

intense, sunlight-tolerant microalga with potential for removing

ammonium from wastewater. Bioresour Technol. 99:4980–4989.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Janssen M, Kuijpers TC, Veldhoen B,

Ternbach MB, Tramper J, Mur LR and Wijffels RH: Specific growth

rate of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Chlorella sorokiniana under

medium duration light/dark cycles: 13-87 s. J Biotechnol.

70:323–333. 1999.

|

|

21

|

León-Vaz A, León R, Díaz-Santos E, Vigara

J and Raposo S: Using agro-industrial wastes for mixotrophic growth

and lipids production by the green microalga Chlorella sorokiniana.

N Biotechnol. 51:31–38. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wan MX, Wang RM, Xia JL, Rosenberg JN, Nie

NY, Kobayashi N, Oyler GA and Betenbaugh MJ: Physiological

evaluation of a new Chlorella sorokiniana isolate for its biomass

production and lipid accumulation in photoautotrophic and

heterotrophic cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng. 109:1958–1964.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bazarnova J, Nilova L, Trukhina E,

Bernavskaya M, Smyatskaya Y and Aktar T: Use of microalgae biomass

for fortification of food products from grain. Foods.

10(3018)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Koyande AK, Chew KW, Rambabu K, Tao Y, Chu

D and Show P: Microalgae: A potential alternative to health

supplementation for humans. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 8:16–24.

2019.

|

|

25

|

Gouveia L and Oliveira AC: Microalgae as a

raw material for biofuels production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol.

36:269–274. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lizzul AM, Lekuona-Amundarain A, Purton S

and Campos LC: Characterization of Chlorella sorokiniana, UTEX

1230. Biology (Basel). 7(25)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Andreeva A, Budenkova E, Babich O, Sukhikh

S, Dolganyuk V, Michaud P and Ivanova S: Influence of carbohydrate

additives on the growth rate of microalgae biomass with an

increased carbohydrate content. Mar Drugs. 19(381)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Panahi Y, Yari Khosroushahi A, Sahebkar A

and Heidari HR: Impact of cultivation condition and media content

on chlorella vulgaris composition. Adv Pharm Bull. 9:182–194.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Petkov G and Garcia G: Which are fatty

acids of the green alga chlorella? Biochem Syst Ecol. 35:281–285.

2007.

|

|

30

|

Otles S (Ed.): Methods of analysis of food

components and additives. CRC Press, 2011.

|

|

31

|

Illman AM, Scragg AH and Shales SW:

Increase in Chlorella strains calorific values when grown in low

nitrogen medium. Enzyme Microb Technol. 27:631–635. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Smyatskaya Y, Toumi A, Atamaniuk I,

Vladimirov I, Donaev FK and Akhmetova IG: Influence of the drying

method on the sorption properties the biomass of chlorella

sorokiniana microalgae. E3S Web Conf. 124(01051)2019.

|

|

33

|

Christaki E, Florou-Paneri P and Bonos E:

Microalgae: A novel ingredient in nutrition. Int J Food Sci Nutr.

62:794–799. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hamed I, Özogul F, Özogul Y and Regenstein

JM: Marine bioactive compounds and their health benefits: A review.

Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 14:446–465. 2015.

|

|

35

|

Bao DQ, Mori TA, Burke V, Puddey IB and

Beilin LJ: Effects of dietary fish and weight reduction on

ambulatory blood pressure in overweight hypertensives.

Hypertension. 32:710–717. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Amaro HM, Barros R, Guedes AC, Sousa-Pinto

I and Malcata FX: Microalgal compounds modulate carcinogenesis in

the gastrointestinal tract. Trends Biotechnol. 31:92–98.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Kagan ML, Levy A and Leikin-Frenkel A:

Comparative study of tissue deposition of omega-3 fatty acids from

polar-lipid rich oil of the microalgae Nannochloropsis oculata with

krill oil in rats. Food Funct. 6:186–192. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Gouveia L, Batista AP, Raymundo A,

Bandarra N and Blades M and Blades M: Spirulina maxima and

Diacronema vlkianum microalgae in vegetable gelled desserts. Nutr

Food Sci. 38:492–501. 2008.

|

|

39

|

Mata TM, Martins AA and Caetano NS:

Microalgae for biodiesel production and other applications: A

review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 14:217–232. 2010.

|

|

40

|

Gouveia L, Marques AE, Sousa JM, Moura P

and Bandarra NM: Microalgae - source of natural bioactive molecules

as functional ingredients. Food Sci Technol Bull Funct Foods.

7:21–37. 2010.

|

|

41

|

Priyadarshani I and Rath B: Commercial and

industrial applications of micro algae-A review. J Algal Biomass

Utln. 3:89–100. 2012.

|

|

42

|

Lizzul AM, Lekuona-Amundarain A, Purton S

and Campos LC: Characterization of chlorella sorokiniana, UTEX

1230. Biology (Basel). 7(25)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Ishiguro S, Robben N, Burghart R, Cote P,

Greenway S, Thakkar R, Upreti D, Nakashima A, Suzuki K, Comer J and

Tamura M: Cell wall membrane fraction of Chlorella sorokiniana

enhances host anti-tumor immunity and inhibits colon carcinoma

growth in mice. Integr Cancer Ther.

19(153473541990055)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Andrade LM, Andrade CJ, Das M, Nascimento

CAO and Mendes MA: Chlorella and Spirulina microalgae as sources of

functional foods, nutraceuticals, and food supplements; an

overview. MOJ Food Process Technol. 6(00144)2018.

|

|

45

|

Spolaore P, Joannis-Cassan C, Duran E and

Isambert A: Commercial applications of microalgae. J Biosci Bioeng.

101:87–96. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Pugh N, Ross SA, ElSohly HN, ElSohly MA

and Pasco DS: Isolation of three high molecular weight

polysaccharide preparations with potent immunostimulatory activity

from Spirulina platensis, Aphanizomenon flos-aquae, and Chlorella

pyrenoidosa. Planta Med. 67:737–742. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Sheng J, Yu F, Xin Z, Zhao L, Zhu X and Hu

Q: Preparation, identification and their anti-tumor activities in

vitro of polysaccharides from Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Food Chem.

105:533–539. 2007.

|

|

48

|

Matos ÂP: Microalgae as a potential source

of proteins. In: Proteins: Sustainable Source, Processing and

Applications. Academic Press, Brookline, MA, pp63-96, 2019.

|

|

49

|

López CV, García Mdel C, Fernández FG,

Bustos CS, Chisti Y and Sevilla JM: Protein measurements of

microalgal and cyanobacterial biomass. Bioresour Technol.

101:7587–7591. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Lourenço SO, Barbarino E, Lavín PL, Lanfer

Marquez UM and Aidar E: Distribution of intracellular nitrogen in

marine microalgae: calculation of new nitrogen-to-protein

conversion factors. Eur J Phycol. 39:17–32. 2004.

|

|

51

|

Becker EW: Microalgae for human and animal

nutrition. In: Handbook of Microalgal Culture: Applied Phycology

and Biotechnology. Richmond A (ed). Blackwell Science, Oxford,

pp461-503, 2013.

|

|

52

|

Fu Y, Chen T, Chen SHY, Liu B, Sun P, Sun

H and Chen F: The potentials and challenges of using microalgae as

an ingredient to produce meat analogues. Trends Food Sci Technol.

112:188–200. 2021.

|

|

53

|

Boisen S and Eggum BO: Critical evaluation

of in vitro methods for estimating digestibility in simple-stomach

animals. Nutr Res Rev. 4:141–162. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Young VR and Pellett PL: Plant proteins in

relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr.

59 (Suppl 5):1203S–1212S. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Friedman M and Brandon DL: Nutritional and

health benefits of soy proteins. J Agric Food Chem. 49:1069–1086.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Hoffman JR and Falvo MJ: Protein-which is

best? J Sports Sci Med. 3:118–130. 2004.

|

|

57

|

Berrazaga I, Micard V, Gueugneau M and

Walrand S: The role of the anabolic properties of plant-versus

animal-based protein sources in supporting muscle mass maintenance:

A critical review. Nutrients. 11(1825)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Nguyen TTP, Bhandari B, Cichero J and

Prakash S: Gastrointestinal digestion of dairy and soy proteins in

infant formulas: An in vitro study. Food Res Int. 76:348–358.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Duodu KG, Taylor JRN, Belton PS and

Hamaker BR: Factors affecting sorghum protein digestibility. J

Cereal Sci. 38:117–131. 2003.

|

|

60

|

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO):

Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition: report of an

FAO Expert Consultation. Food and nutrition paper 92. FAO: Rome,

Italy, 2013.

|

|

61

|

Fleurence J: Seaweed proteins:

Biochemical, nutritional aspects and potential uses. Trends Food

Sci Technol. 10:25–28. 1999.

|

|

62

|

Chronakis IS and Madsen M: Algal proteins.

In Handbook of food proteins. Woodhead Publishing.

353-394:2011.

|

|

63

|

Waghmare AG, Salve MK, LeBlanc JG and Arya

SS: Concentration and characterization of microalgae proteins from

Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Bioresour Bioprocess. 3(16)2016.

|

|

64

|

Rodrigues DB, Marques MC, Hacke A, Loubet

Filho PS, Cazarin CBB and Mariutti LRB: Trust your gut:

Bioavailability and bioaccessibility of dietary compounds. Curr Res

Food Sci. 5:228–233. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Alegría A, Garcia-Llatas G and Cilla A:

Static digestion models: General introduction. In: The Impact of

Food Bioactives on Health: In vitro and ex vivo

models. Verhoeckx K, Cotter P and López-Expósito I (eds). Springer,

New York, NY, pp3-12, 2015.

|

|

66

|

Rein MJ, Renouf M, Cruz-Hernandez C,

Actis-Goretta L, Thakkar SK and da Silva Pinto M: Bioavailability

of bioactive food compounds: A challenging journey to bioefficacy.

Br J Clin Pharmacol. 75:588–602. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Dima C, Assadpour E, Dima S and Jafari SM:

Bioavailability and bioaccessibility of food bioactive compounds;

overview and assessment by in vitro methods. Compr Rev Food Sci

Food Saf. 19:2862–2884. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Niccolai A, Zittelli GC, Rodolfi L, Biondi

N and Tredici MR: Microalgae of interest as food source:

Biochemical composition and digestibility. Algal Res.

42(101617)2019.

|

|

69

|

Maehre HK, Edvinsen GK, Eilertsen KE and

Elvevoll EO: Heat treatment increases the protein bioaccessibility

in the red seaweed dulse (Palmaria palmata), but not in the brown

seaweed winged kelp (Alaria esculenta). J Appl Phycol. 28:581–590.

2016.

|

|

70

|

Bernaerts TMM, Verstreken H, Dejonghe C,

Gheysen L, Foubert I, Grauwet T and Van Loey AM: Cell disruption of

Nannochloropsis sp. improves in vitro bioaccessibility of

carotenoids and ω3-LC-PUFA. J Funct Foods. 65(103770)2020.

|

|

71

|

Gómez-Jacinto V, Navarro-Roldán F,

Garbayo-Nores I, Vílchez-Lobato C, Borrego AA and García-Barrera T:

In vitro selenium bioaccessibility combined with in vivo

bioavailability and bioactivity in Se-enriched microalga (Chlorella

sorokiniana) to be used as functional food. J Funct Foods.

66(103817)2020.

|

|

72

|

Demarco M, Oliveira de Moraes J, Matos ÂP,

Derner RB, de Farias Neves F and Tribuzi G: Digestibility,

bioaccessibility and bioactivity of compounds from algae. Trends

Food Sci Technol. 121:114–128. 2022.

|

|

73

|

Moughan P: Digestion and absorption of

proteins and peptides. Designing Funct Foods. 148-170:2008.

|

|

74

|

World Health Organization: Trace Elements

in Human Nutrition and Health. 1996. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241561734.

|

|

75

|

Camaschella C: Iron-deficiency anemia. N

Engl J Med. 372:1832–1843. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Ozturk H, Niazi P, Mansoor M, Monib AW,

Alikhail M and Azizi A: The function of zinc in animal, plant, and

human nutrition. J Res Appl Sci Biotechnol. 2:35–43. 2023.

|

|

77

|

Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B and

Camaschella C: Two to tango: Regulation of mammalian iron

metabolism. Cell. 142:24–38. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Nakano S, Takekoshi H and Nakano M:

Chlorella pyrenoidosa supplementation reduces the risk of anemia,

proteinuria and edema in pregnant women. Plant Foods Hum Nutri.

65:25–30. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Bito T, Okumura E, Fujishima M and

Watanabe F: Potential of Chlorella as a dietary supplement to

promote human health. Nutrients. 12(2524)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Batista AP, Niccolai A, Fradinho P,

Fragoso S, Bursic I, Rodolfi L, Biondi N, Tredici MR, Sousa I and

Raymundo A: Microalgae biomass as an alternative ingredient in

cookies: Sensory, physical and chemical properties, antioxidant

activity and in vitro digestibility. Algal Res. 26:161–171.

2017.

|

|

81

|

Chini Zittelli G, Rodolfi L, Biondi N and

Tredici MR: Productivity and photosynthetic efficiency of outdoor

cultures of Tetraselmis suecica in annular columns. Aquac.

261:932–943. 2006.

|

|

82

|

Cazarin CBB, Bicas JL, Pastore GM and

Marostica Junior MR: Bioactive Food Components Activity in

Mechanistic Approach. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp1-3, 2022.

|

|

83

|

Carbonell-Capella JM, Buniowska M, Barba

FJ, Esteve MJ and Frígola A: Analytical methods for determining

bioavailability and bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds from

fruits and vegetables: A review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf.

13:155–171. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Widyaningrum D and Prianto AD: Chlorella

as a source of functional food ingredients: Short review. IOP Conf

Ser Earth Environ Sci. 794(012148)2021.

|

|

85

|

Olasehinde TA, Odjadjare EC, Mabinya LV,

Olaniran AO and Okoh AI: Chlorella sorokiniana and Chlorella

minutissima exhibit antioxidant potentials, inhibit cholinesterases

and modulate disaggregation of β-amyloid fibrils. Electron J

Biotechnol. 40:1–9. 2019.

|

|

86

|

Beale SI and Appleman D: Chlorophyll

synthesis in Chlorella: Regulation by degree of light limitation of

growth. Plant Physiol. 47:230–235. 1971.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

da Silva JC and Lombardi AT: Chlorophylls

in microalgae: occurrence, distribution, and biosynthesis. In:

Pigments from Microalgae Handbook. Springer International

Publishing, Switzerland, pp1-18, 2020.

|

|

88

|

Azaman SNA, Nagao N, Yusoff FM, Tan SW and

Yeap SK: A comparison of the morphological and biochemical

characteristics of Chlorella sorokiniana and Chlorella zofingiensis

cultured under photoautotrophic and mixotrophic conditions. PeerJ.

5(e3473)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Goiris K, Muylaert K, Fraeye I, Foubert I,

De Brabanter J and De Cooman L: Antioxidant potential of microalgae

in relation to their phenolic and carotenoid content. J Appl

Phycol. 24:1477–1486. 2012.

|

|

90

|

Takaichi S: Carotenoids in algae:

Distributions, biosyntheses and functions. Mar Drugs. 9:1101–1118.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Diprat AB, Silveira Thys RC, Rodrigues E

and Rech R: Chlorella sorokiniana: A new alternative source of

carotenoids and proteins for gluten-free bread. LWT.

134(109974)2020.

|

|

92

|

Fernandes AS, Petry FC, Mercadante AZ,

Jacob-Lopes E and Zepka LQ: HPLC-PDA-MS/MS as a strategy to

characterize and quantify natural pigments from microalgae. Curr

Res Food Sci. 3:100–112. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Machu L, Misurcova L, Ambrozova JV,

Orsavova J, Mlcek J, Sochor J and Jurikova T: Phenolic content and

antioxidant capacity in algal food products. Molecules.

20:1118–1133. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Wojdylo A, Oszmianski J and Czemerys R:

Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs.

Food Chem. 105:940–949. 2007.

|

|

95

|

Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C

and Jiménez L: Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J

Clin Nutr. 79:727–747. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Safafar H, van Wagenen J, Møller P and

Jacobsen C: Carotenoids, phenolic compounds and tocopherols

contribute to the antioxidative properties of some microalgae

species grown on industrial wastewater. Mar Drugs. 13:7339–7356.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|