Introduction

Dental caries is a disease resulting from multiple

factors, beginning with changes in the microbiological composition

of the intricate biofilm and influenced by sugar intake, fluoride

exposure, saliva flow and composition, as well as dental hygiene

practices. Dental caries results from the transformation of

fermentable sugars by bacteria in dental plaque into acids on the

surface of teeth. Therefore, it is crucial to emphasize the

reduction of sugar intake and the management of plaque (1). Dental caries is widely recognized to

develop when the biofilm microbiota that typically exists in a

state of balance in the oral cavity shifts to an acid-producing,

acid-tolerant, and cavity-causing community as a result of regular

sugar intake. The outcome of this change may be undetectable in

clinical settings or cause a net loss of minerals in the hard

tissues of the tooth, leading to the appearance of a cavity

(2,3). Caries is recognized as the most

common oral health issue globally, affecting children, teenagers

and adults, and it is the leading cause of tooth loss in the

population. In addition to caries, there are various other diseases

of the mouth that can be identified and tracked using cytokines,

which play a critical role in regulating the immune and

inflammatory responses (4).

Cytokines play a pivotal role in the immunopathogenesis of dental

caries. Among the different cytokines under examination for their

potential inclusion in caries conclusion are interleukin (IL)-4,

IL-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (5).

Cytokines play a major role in modulating the immune

response, and are either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory.

They are critical for regulating immune responses. Any cell nuclei

can release cytokines, but helper T cells and macrophages are the

primary producer (6). The

chemokine class prototype molecule is IL-8, a cytokine that

provokes inflammatory reactions. Additionally, IL-8 is a key player

in the acute inflammatory reaction and remains at the site of

inflammation for a considerable amount of time (7). The protein TNF-α plays a role in

alert responses and host defense. White blood cell molecules stick

to endothelial cells and trigger phagocytic killing processes,

which encourages cell proliferation. In addition to cytotoxic and

cytostatic effects on cancerous cells. IL-8 and TNF-α products of

immune cells also play an critical role in diseases of the oral

mucosa. However, patients with dental caries higher levels of IL-8

and TNF-α, leading to a lower number of osteoblasts and

fibroblasts, and they support the demineralization of teeth and

development of the dental caries process. These cytokines, which

are produced locally by osteoclasts, have been shown to be a

critical factor in regulating the differentiation of these cells

and participating in resorption processes (6). The inflammatory aspect of caries

disease, a known source for molecular diagnosis, remains unknown,

and the diagnosis for the condition contuse to depend on clinical,

visual and radiographic techniques (8). The aim of the present study was to

assess the diagnostic precision of cytokines (IL-8 and TNF-α) in

distinguishing between subjects with caries and those without.

Subjects and methods

Study design and ethics approval. The present study

was a case-control study. The subjects included in the study were

provided with a comprehensive explanation of the purpose and

methods of the study. Their permission was gained via a document

vetted via the Ethic Committee of the College of Dentistry,

University of Baghdad (Reference no. 1000 on 7-1-2025).

Study subjects

A total of 44 subjects were enrolled in the present

study (22 adults subjects with dental caries and 22 of the same age

and sex without caries were randomly selected as the control

group). There was a specific case sheet used to obtain information

about the name, age, sex and general health of the adult and

whether the subject was a smoker or alcoholic or not. A

questionnaire about the general and oral health habits of the

selected patients was prepared to ensure that they were free from

any systematic diseases and did not take any medications for at

least the past 1 month.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All participants recruited in the study as the test

subjects had dental caries, >20 years, had no systemic disease

with no antibiotic consumption for the past 3 months. The control

group were subjects with healthy gingiva, exhibiting good oral

hygiene without any history of dental caries or related symptoms.

The present study excluded children and patients who had the

following conditions: Smoking or alcohol consumption, unapproved

consent, pregnant or lactating women, or those taking medications

(antibiotics or any medications).

Oral examination

The assessment of clinical caries was performed by

an examination of teeth and evaluation of decayed, missing and

filled surfaces (DMFS) and plaque index (the amount of dental

plaque at four surfaces of each tooth was assessed). The assessment

of dental plaque was performed according to the plaque index system

(9). The scores and criteria for

this system were followed as proposed by authors, as follows: Score

0, no plaque in the gingival area; score 1, a film of plaque

adhering to the free gingival margin and adjacent area of the tooth

surface; score 2, moderate accumulation of soft deposits within the

gingival pocket on the gingival margin and/or adjacent tooth

surface which can be seen by naked eye; score 3, abundance of soft

matter within the gingival pocket and/or on the gingival margin and

the adjacent tooth surface.

Gingival index

The occurrence of gingival inflammation at four

surfaces of each tooth was assessed using the criteria of gingival

index system (9), as follows:

Score 0, normal gingiva; score 1, mild inflammation, slight change

in color, slight edema, no bleeding on probing; score 2, moderate

inflammation, redness, edema and glazing, bleeding on probing;

score 3, severe inflammation, marked redness and edema, ulceration,

tendency for spontaneous bleeding.

Saliva sample collection

At least 1 h prior to saliva collection, all

participants were requested to not consume anything other than

water. The subjects then repeatedly rinsed their mouths with

sterile water and waited 1 to 2 min for the water to drain; up to 2

ml whole unstimulated saliva was collected into tubes. The

collected saliva was then centrifuged at 804.96 x g for 10 min at

room temperature (~20˚C) and the resulting supernatant was stored

at -20˚C in Eppendorf tubes until further processing (10,11).

Detection of IL-8 and TNF-α

levels

The ELISA procedure for the present study was the

sandwich-ELISA technique. According to the manufacturer of the kit

(Shanghai YL Biotech Co., Ltd.), a capture antibody that is highly

specific for the biomarker (IL-8 and TNF-α) was attached to the

wells of the strip plate. During the incubation time (60 min at

37˚C), each biomarker sample and known standards were bound to

capture antibodies, followed by binding the biotinylated anti-IL-8

(Human IL-8 ELISA KIT, cat no. YLA1210HU, Shanghai YL Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) and anti-TNF-α (Human receptor superfamily member 13B ELISA

KIT, cat no. YLA0576HU, Shanghai YL Biotech Co., Ltd.) secondary

antibody (to the analyte to create the captured complex. The

secondary antibody and any extra unbound analyte were rinsed away.

The HRP conjugation solution (provided with the aforementioned

kits) was added to each well, even the zero wells, to attach to the

complex. The excess conjugate was then carefully washed away

following incubation (60 min at 37˚C). Adding a chromogen substrate

solution (provided with the aforementioned kits) to the wells

gradually caused the conjugate and chromogen to produce a

blue-colored compound. The addition of acid then halted color

development. After the sulfuric acid reaction was terminated, the

yellow hue was produced. The concentration of each biomarker in the

samples and standards directly relates to the intensity of the

colorful formed complex. The absorbances were assessed

spectrophotometrically at 450 nm using an ELISA plate reader

(Glomax; Promega Corporation).

The data were analyzed using G power 3.1.9.7

software from Franz-Faul (Kiel University, Germany). Given these

conditions, the sample size was determined to be 40 participants in

total, 20 in each of the two groups, assuming a medium effect size

of 0.6 between them. This gave the statistical test an overall

power of 85% and an α error of probability of 0.05. Accordingly, 44

subjects were included in the study.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses of the data were performed

and processed with the computerized analysis statistical package

for the social sciences (SPSS) software program (version 25, IBM

Corp.) and GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0, Dotmatics). A

value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. The distribution of clinical and

immunological data was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Since the variables in the dataset were normally distributed,

parametric tests were preferred. The data are presented as

descriptive statistics involving the mean and standard deviation.

The Chi-squared test was preferred to analyze sex distributions.

When comparing two groups, the (Student's t-test) was utilized.

Pearson' rank correlation analysis was used to analyze the

correlations between clinical and immunological parameters. In

addition, to determine the diagnostic potential of the cytokines, a

receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was established.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical

parameters

The mean and standard deviation values were

calculated for the demographic variables and clinical parameters of

the two study groups (Table I).

The demographic data distributions for patients were determined for

sex (12 females, 10 males and age (range, 20-35 years). The DMFS

ranged from 9 to 70 with a mean value of 32.12±19.05, and the

sample site analysis of the clinical parameters plaque index (PLI)

and gingival index (GI) were revealed to be all significantly

higher for dental caries (study) group compared to the healthy

group (P<0.05) (Table I).

| Table IDemographic characteristics and

clinical parameters in study groups. |

Table I

Demographic characteristics and

clinical parameters in study groups.

| Demographic

characteristics | Study group n=22 | Control group

n=22 | P-value |

|---|

| Age | | | 0.258

(NS)a |

|

Range

(years) | 20-35 | 20-33 | |

|

Mean ±

SD | 29.90±5.42 | 28.68±5.16 | |

| Sex | | | 0.762

(NS)b |

|

Female | 12 (54.54%) | 11 (50.0%) | |

|

Male | 10 (45.45%) | 11 (50.0%) | |

| Clinical

parameters | | | |

|

PLI (mean ±

SD) | 1.56±0.52 | 0.45±0.05 |

<0.001c |

|

GI (mean ±

SD) | 1.57±0.57 | 0.90±0.29 |

<0.001c |

|

DMFS | 32.12±19.05 | - | - |

Salivary cytokine levels

The present study revealed that the mean values of

IL-8 and TNF-α were significantly higher (P<0.05) in the dental

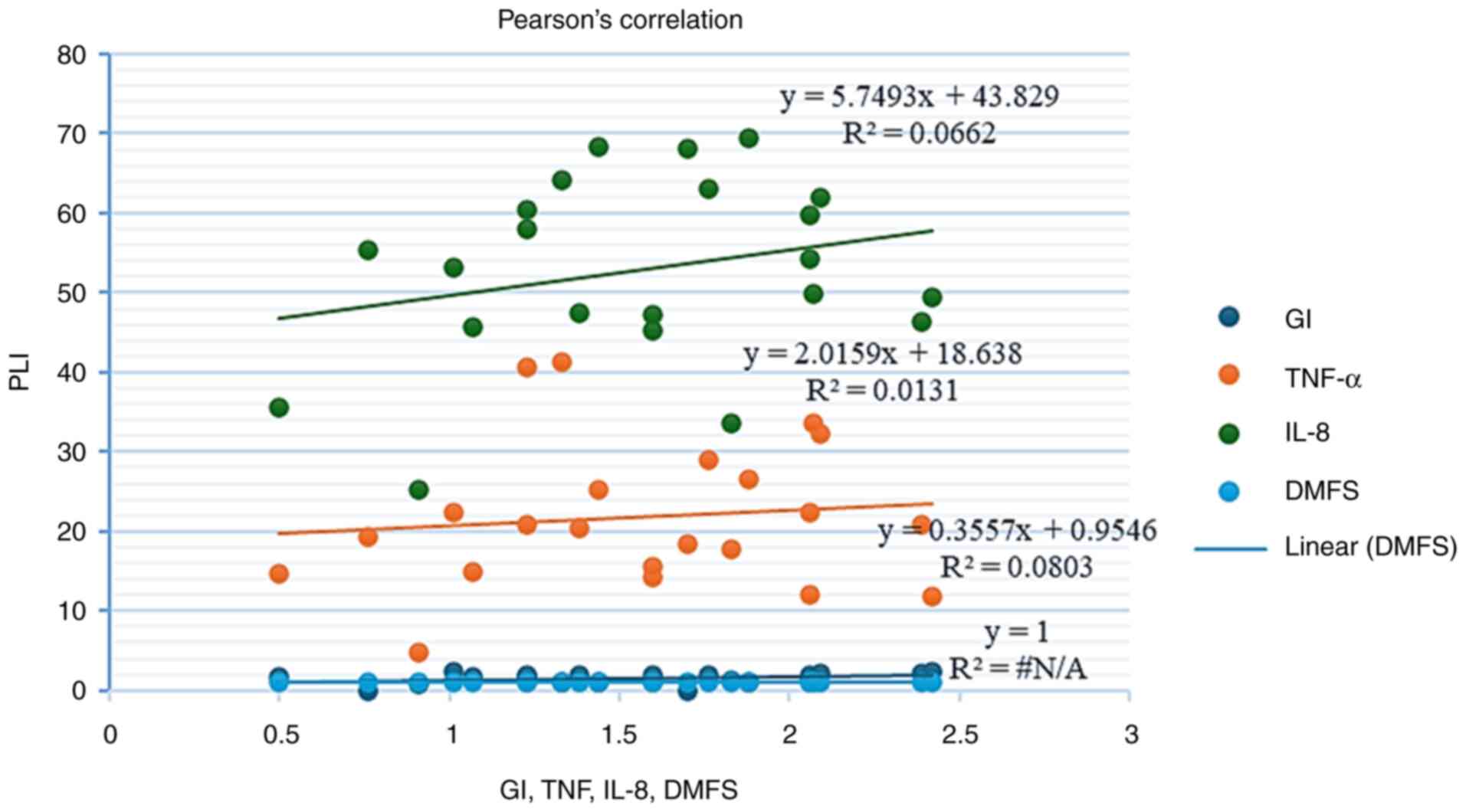

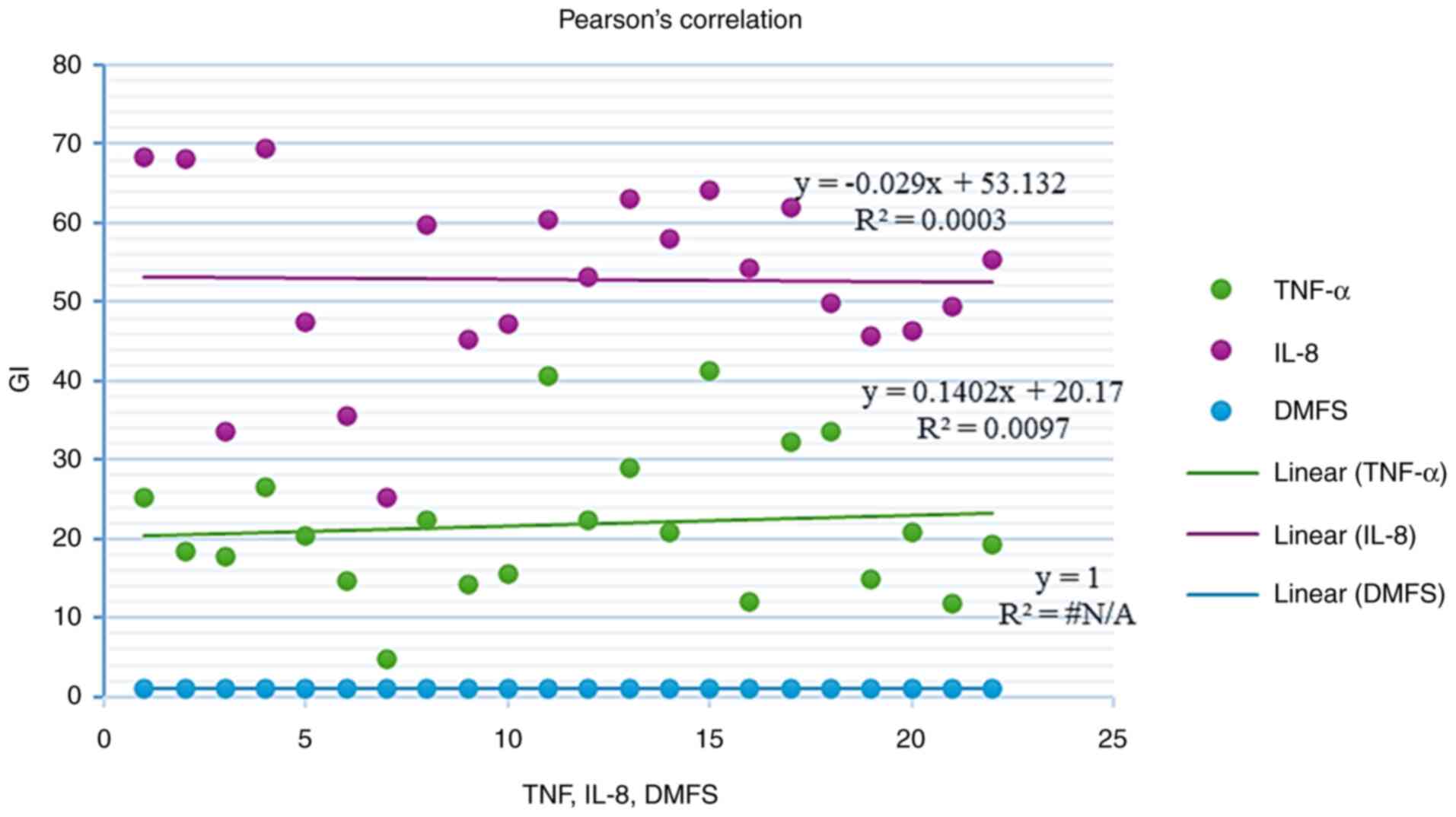

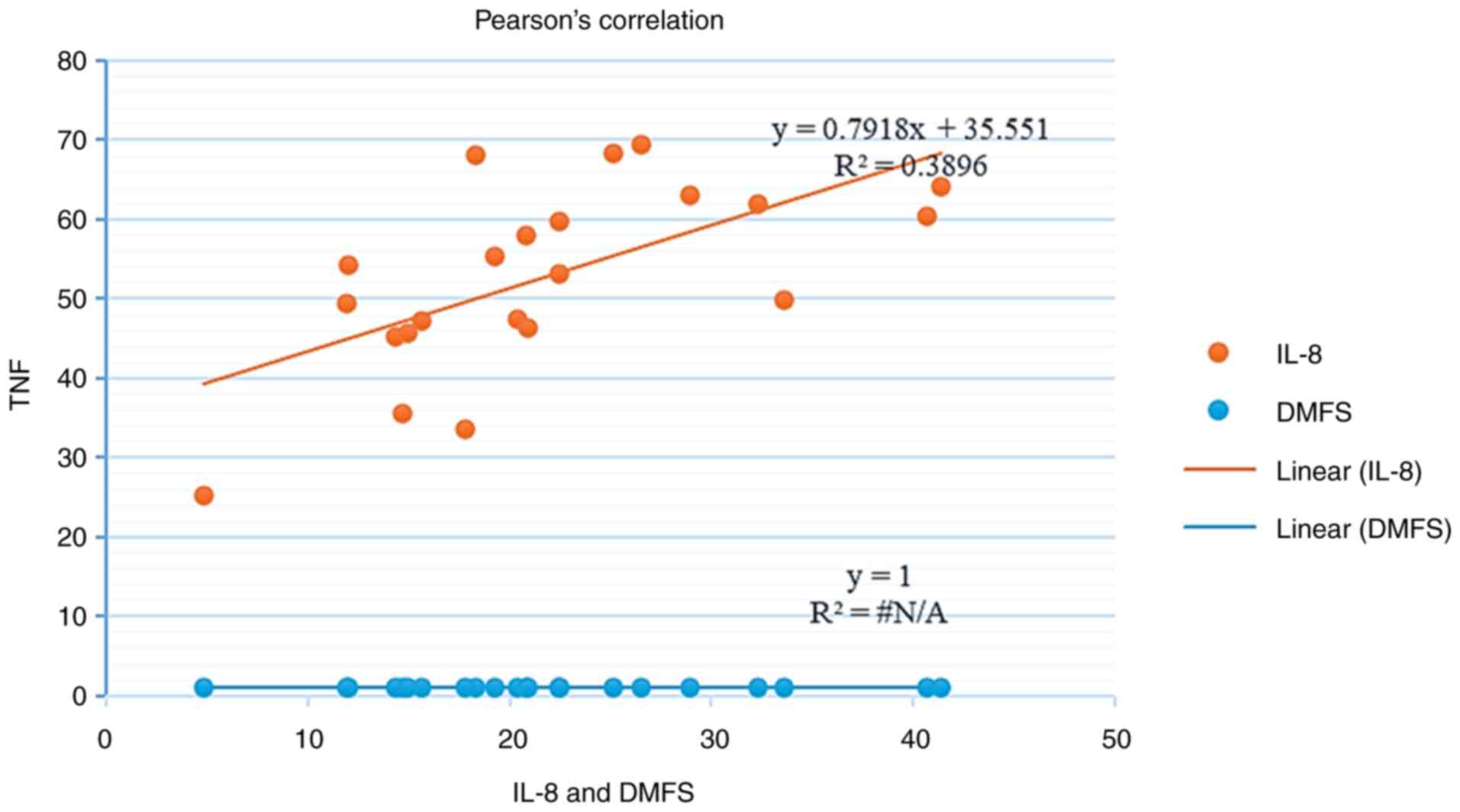

caries group in comparison to the group without caries (Table II). Moreover, as demonstrated in

Table III and Fig. 1, 2

and 3, the results revealed that

there was a significant positive correlation between IL-8 and TNF-α

in the patient group (r=0.624, P=0.001), whereas there are no

significant correlations between clinical parameters and cytokines

in caries group.

| Table IIMean salivary levels of IL-8 and TNF-α

in the study groups. |

Table II

Mean salivary levels of IL-8 and TNF-α

in the study groups.

| Salivary

cytokines | Study group n=22 | Control group

n=22 | t-test (P-value) |

|---|

| IL-8 (pg\ml) | | | 0.002a |

|

Range | 22.24-69.54 | 20.55-65.28 | |

|

Mean ±

SD | 52.79±11.69 | 42.63±11.08 | |

| TNF-α (pg\ml) | | | 0.011a |

|

Range | 4.83-41.35 | 7.57-33.77 | |

|

Mean ±

SD | 21.78±9.22 | 16.39±6.55 | |

| Table IIIPearson's correlation analysis of the

correlation between cytokines and clinical parameters in the caries

group. |

Table III

Pearson's correlation analysis of the

correlation between cytokines and clinical parameters in the caries

group.

| | Parameter |

|---|

| Parameter | PLI | GI | DMFS | IL-8 | TNF-α |

|---|

| PLI | - | r=0.217 P=0. 330 | r=0.089 P=0. 723 | r=0.257 P=0.247 | r=0.114 P=0. 612 |

| GI | r=0.217 P=0. 330 | - | r=0.070

P=0.726 | r=0.183 P=0.

413 | r=-0.018

P=0.936 |

| DMFS | r=0.089 P=0.

723 | r=0.070 P=0.

726 | - | r=0.157 P=0.

484 | r=0.217 P=0.

332 |

| IL-8 | r=0.257

P=0.247 | r=0.183 P=0.

413 | r=0.157

P=0.484 | - | r=0.624 P=0.

001a |

| TNF-α | r=0.114

P=0.612 | r=-0.018

P=0.936 | r=0.217

P=0.332 | r=0.624 P=0.

001a | - |

Diagnostic accuracy of salivary

cytokines

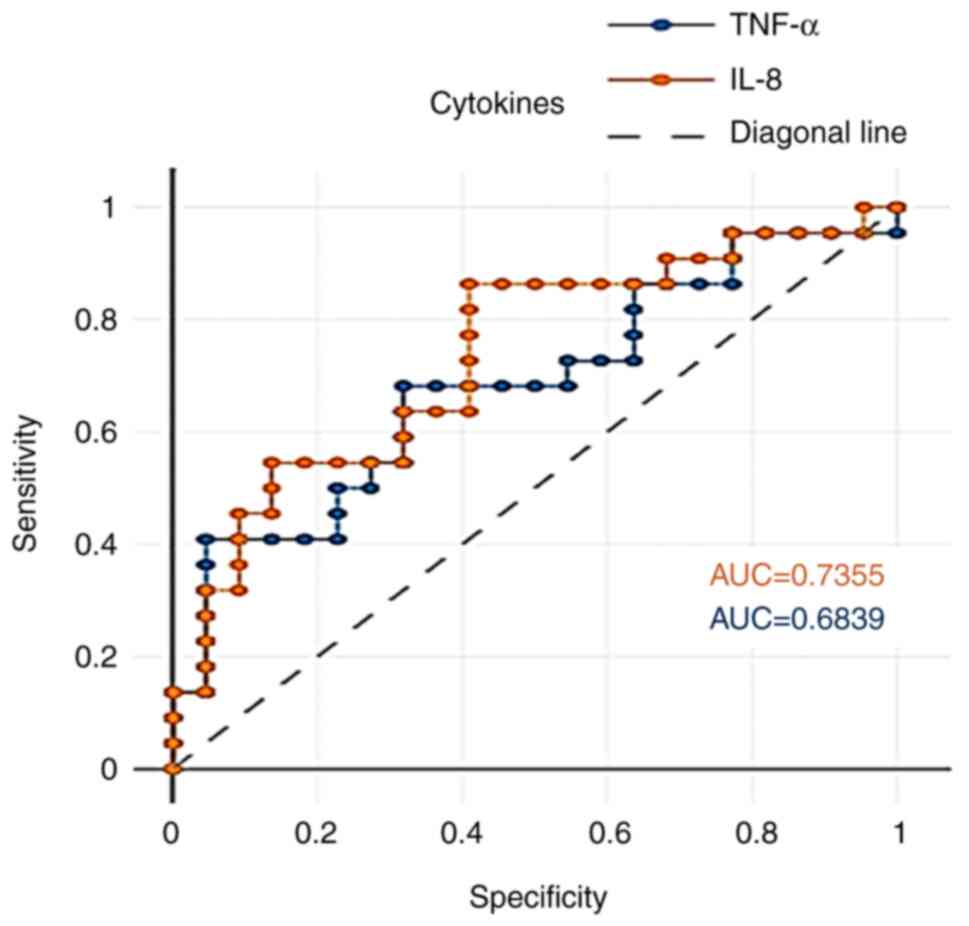

ROC analysis was performed to determine the

sensitivity and specificity of salivary IL-8 and TNF-α to

discriminate caries patients from healthy controls. IL-8 in saliva

exhibited acceptable potentials in differentiating patients from

healthy controls (Fig. 4).

Furthermore, the area under the curve (AUC) values for salivary

IL-8 and TNF between the study and control groups were 0.735 and

0.683, respectively, as shown in Table IV.

| Table IVComparison of the diagnostic

properties of cytokines among the study groups. |

Table IV

Comparison of the diagnostic

properties of cytokines among the study groups.

| Comparison | Test result

variables (s) | AUC | P-value | Optimal cut of

point | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|

| Dental caries vs.

controls | IL-8 | 0.735 | 0.01a | 45.16 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| | TNF-α | 0.683 | 0.01a | 22.43 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

Discussion

In dental pulp, dental caries promote a host

inflammatory reaction that is evidenced by the buildup of

inflammatory leucocytes and the subsequent produce of

pro-inflammatory cytokines (12).

Cytokines were essential for inflammatory process and immune

response. Saliva could be utilized as a non-invasive diagnostic

liquid to evaluate biomarkers in the early and developed phases of

the disease, and cytokines and other factors are helpful diagnostic

and monitoring tools for the oral cavity (13). The present study assessed IL-8

levels in the participants and found that the dental caries group

had higher levels than the control group. The IL-8 is a less

commonly investigated interleukin among inflammatory biomarkers

associated with dental caries. The present study demonstrated that

the salivary levels of IL-8 exhibited a discriminative ability

between healthy controls and patients with dental caries, with a

sensitivity value of 0.95 and specificity value of 0.95. The

diagnostic potential AUC value, as measured in the present study,

was 0.735 with a cut-off point of 45.16 pg/ml. This finding is

consistent with the findings of previous studies (14-16), which found

increased levels of this cytokine among conditions with active

dental caries compared to their control groups. According to

Gornowicz et al (17),

adolescents with dental caries had elevated amounts of this

pro-inflammatory cytokine than those without dental decay,

verifying the function of IL-8 as a pivotal chemokine in

granulocytes chemotaxis. Likewise, Zhao et al (18) reported that patients with active

carious lesions had a noticeably higher IL-8 concentration.

Cariogenic pathogens are primarily Gram-positive, and their

products, such as lipoteichoic acid, which is ubiquitous in

cariogenic streptococci, promote Toll-like receptor 2 and

inflammasomes peptides, which results in the marked production of

this chemokine. This could explain the increase in the level of

this mediator (19,20). However, two other studies (12,21)

did not find any key variations between the caries and caries-free

groups in terms of the salivary levels of IL-8.

Apart from IL-8, TNF-α levels was also analyzed in

the present study, which were shown to be higher in the patients

with caries. The salivary levels of TNF-α exhibited a

discriminative ability between healthy controls and dental caries

patients with a sensitivity value of 0.95 and specificity value of

0.95. The diagnostic potential AUC value, as measured herein, was

0.683 with a cut-off point of 22.43 pg/ml. Likewise, as regards the

TNF-α level, previous studies (22-25) have

demonstrated that the levels of this cytokine in the saliva of

children and adults with dental caries are increased, and are

associated with disease progression and severity. Higher levels of

this cytokine may indicate an inflammatory response in the defenses

of the body, leading to a production of TNF-α through damaging

mechanisms. TNF-α is involved in various disease processes,

including caries development (26,27).

TNF-α is an empirical indicator that quantifies the amount of

inflammation, perhaps beneficial for diagnosing caries (28). Kurtiş et al (29) found that increased levels of TNF-α

in patients with dental caries reduced the total amount of

osteoblasts and fibroblasts, promoting tooth demineralization and

the occurrence of dental disease. However, only one study (16) reported higher levels of this

cytokine in normal subjects than in individuals with the disease.

The discrepancy between prior results and the current results may

be attributable to variations in age or the use of non-parametric

approaches for the analysis of data rather than the less

conservative parametric approaches used in the present study.

Furthermore, salivary TNF-α levels were found to be positively

related to IL-8. This finding is not surprising, as TNFα and IL-8

are released by the same cell types, interact frequently and share

numerous mechanisms, including inflammatory bone resorption.

Moreover, These cytokines contribute to oral cavity immunity

(17). TNF-α is an operational

molecule that causes dental illnesses and increases IL-8 levels

(6). In addition, the present

study revealed that there was no significant association between

cytokines levels and clinical parameters; however, according to

Giudice et al (30),

cytokine levels in children may increase as a result of poor plaque

control, plaque buildup and periodontal inflammation.

The present study had a main limitation which should

be mentioned. The present study did not include the severity of

disease and anti-inflammatory cytokines were also not examined.

In conclusion, according to the findings of the

present study, the salivary levels of the IL-8 and TNF-α cytokines

were higher in patients with dental caries, suggesting a possible

involvement of these cytokines in the etiology of dental caries.

Moreover, IL-8 exhibited a moderate clinical accuracy in

differentiating the patients from the controls. Thus, IL-8 and

TNF-α may prove to be useful as diagnostic biomarkers for dental

caries. The identification of IL-8 and TNF-α as potential

biomarkers for dental caries opens new avenues for early detection,

risk assessment and personalized treatments. These findings

underscore the importance of inflammatory pathways in the

pathogenesis of dental caries and highlight the need for further

research to validate these biomarkers and their association with

caries progression, in order to enhance diagnostic and therapeutic

strategies. Moreover, the findings of the present study may pave

the way for innovative, biomarker-driven approaches in preventive

dentistry, ultimately reducing the global burden of dental

caries.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

BHAG and AAHA were involved in the conception and

design of the study, in the literature search, in the clinical

analysis, data analysis, statistical analysis, and in the

preparation and reviewing of the manuscript. HKM, SSJ and FAMAK

were involved in the conception and design of the study, as well as

in data analysis, and in the preparation and reviewing of the

manuscript. BHAG and HKM confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. The final manuscript has been read and approved by all

authors.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Institutional Review Board's Ethics Committee of

the Ethics Committee of the Dentistry School at the University of

Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq, gave its approval to this study (Reference

no. 1000 on 7-1-2025). A written informed consent to participate in

the study, as specified in the Declaration of Helsinki, was sought

from each patient.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ali AA and Belgasem KA: Dental caries

experience of primary school children in Sirte-libya. Saudi J Oral

Dent Res. 9:1–6. 2024.

|

|

2

|

Meyer F, Schulze Zur Wiesche E, Amaechi

BT, Limeback H and Enax J: Caries etiology and preventive measures.

Eur J Dent. 18:766–776. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Duangthip D, Gao SS, Chen KJ, Lo ECM and

Chu CH: Oral health-related quality of life and caries experience

of Hong Kong preschool children. Int Dent J. 70:100–107.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kareem SJ and Al-Ghurabi BH: Regulatory

role of human neutrophil peptides (HNP1-3) on Interleukin-6

production in early childhood caries. J Emergency Med Trauma Acute

Care. 2023(11)2023.

|

|

5

|

Alarcón-Sánchez MA, Becerra-Ruiz JS,

Avetisyan A and Heboyan A: Activity and levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and

IL-8 in saliva of children and young adults with dental caries: A

systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health.

24(816)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hussein BJ, Atallah HN and Al-Dahhan NAA:

Salivary levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis

Factor-alpha in smokers aged 35-46 years with dental caries

disease. Medico Legal Update. 20:1464–1470. 2020.

|

|

7

|

Tampa M, Mitran MI, Mitran CI, Sarbu MI,

Matei C, Nicolae I, Caruntu A, Tocut SM, Popa MI, Caruntu C and

Georgescu SR: Mediators of inflammation-a potential source of

biomarkers in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunol Res.

2018(1061780)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Abdelaziz M: Detection, diagnosis, and

monitoring of early caries: The future of individualized dental

care. Diagnostics (Basel). 13(3649)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Silness J and Loe H: Periodontal disease

in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal

condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 22:121–135. 1964.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Navazesh M: Methods for collecting saliva.

Ann N Y Acad Sci. 694:72–77. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Al-Hindawi SH, Luaibi NM and Al-Ghurabei

BH: Possible use of saliva as a diagnostic tool in hypothyroidism.

J Biosci Biotech. 6:539–542. 2017.

|

|

12

|

Sharma V, Gupta N, Srivastava N, Rana V,

Chandna P, Yadav S and Sharma A: Diagnostic potential of

inflammatory biomarkers in early childhood caries-A case control

study. Clin Chim Acta. 471:158–163. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Benabdelmoumene S, Dumont S, Petit C,

Poindron P, Wachsmann D and Klein JP: Activation of human monocytes

by Streptococcus mutans serotype f polysaccharide: Immunoglobulin G

Fc receptor expression and tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1

production. Infect Immun. 59:3261–3266. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Biria M, Sattari M, Iranparvar P and

Eftekhar L: Relationship between the salivary concentrations of

proteinase-3 and interleukin-8 and severe early childhood caries.

Dent Med Probl. 60:577–582. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Børsting T, Venkatraman V, Fagerhaug TN,

Skeie MS, Stafne SN, Feuerherm AJ and Sen A: Systematic assessment

of salivary inflammatory markers and dental caries in children: An

exploratory study. Acta Odontol Scand. 80:338–345. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Rinderknecht C, Filippi C, Ritz N,

Fritschi N, Simmen U, Filippi A and Diesch-Furlanetto T:

Associations between salivary cytokines and oral health, age, and

sex in healthy children. Sci Rep. 12(15991)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Gornowicz A, Bielawska A, Bielawski K,

Grabowska SZ, Wójcicka A, Zalewska M and Maciorkowska E:

Pro-inflammatory cytokines in saliva of adolescents with dental

caries disease. Ann Agric Environ Med. 19:711–716. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhao A, Blackburn C, Chin J and Srinivasan

M: Soluble toll like receptor 2 (TLR-2) is increased in saliva of

children with dental caries. BMC Oral Health.

14(108)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Keller JF, Carrouel F, Colomb E, Durand

SH, Baudouin C, Msika P, Bleicher F, Vincent C, Staquet MJ and

Farges JC: Toll-like receptor 2 activation by lipoteichoic acid

induces differential production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in

human odontoblasts, dental pulp fibroblasts and immature dendritic

cells. Immunobiology. 215:53–59. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Al-Ghurabi BH: The role of soluble TLR-2

in the immunopathogenesis of Gingivitis. Int Med J. 28:37–39.

2021.

|

|

21

|

Seyedmajidi M, Khodadadi E, Maliji G,

Zaghian M and Bijani A: Neutrophil count and level of

interleukin-1β and interleukin-8 in the saliva of three to five

year olds with and without dental caries. J Dent (Tehran).

12:662–668. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Leme LAFP, Rizzardi KF, Santos IB and

Parisotto TM: Exploring the relationship between salivary levels of

TNF-α, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus gasseri, obesity,

and caries in early childhood. Pathogens. 11(579)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ali Al-Dahhan HA, Al-Kishwan SS, Dakheel

AH and Dakheel BH: Assessment of some Pro-inflammatory cytokines in

saliva of dental caries. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol.

15:3035–3040. 2021.

|

|

24

|

Nazemisalman B, Jafari F, Esmaelzadeh A,

Faghihzadeh S, Vahabi S and Moslemi H: Salivary tumor necrosis

factor-alpha and dental caries in children and adolescents. Iranian

J Pediatrics. 29(e80899)2019.

|

|

25

|

Ribeiro CCC, Pachêco CdJB, Costa EL,

Ladeira LLC, Costa JF, da Silva RA and Carmo CDS: Proinflammatory

cytokines in early childhood caries: Salivary analysis in the

Mother/children pair. Cytokine. 107:113–117. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Akcalı A, Çeneli SK, Meriç P, Nalbantsoy

A, Ozçaka Ö and Buduneli N: Altered levels of inhibitory cytokines

in patients with thalassemia major and gingival inflammation.

Brazilian Dental Sci. 22:349–357. 2019.

|

|

27

|

Ali AJ, Al-Juboori JNA and Al-Nimer M:

Concomitant using of topical carrageenan-kappa and oral vitamin D

against 7, 12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene induced-oral cancer in

rats: A synergism or an antagonism effects. Brazilian Dental Sci.

23(7)2020.

|

|

28

|

Hirsch V, Wolgin M, Mitronin AV and

Kielbassa AM: Inflammatory cytokines in normal and irreversibly

inflamed pulps: A systematic review. Arch Oral Biol. 82:38–46.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kurtiş B, Tüter G, Serdar M, Akdemir P,

Uygur C, Firatli E and Bal B: Gingival crevicular fluid levels of

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha

in patients with chronic and aggressive periodontitis. J

Periodontol. 76:1849–1855. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Lo Giudice R, Militi A, Nicita F, Bruno G,

Tamà C, Lo Giudice F, Puleio F, Calapai F and Mannucci C:

Correlation between oral hygiene and il-6 in children. Dent J

(Basel). 8(91)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|