1. Introduction

Rabies is an acute, often fatal viral disease that

primarily affects the central nervous system. It is typically

transmitted through bites from infected domestic dogs and wild

carnivorous animals. All warm-blooded animals, including humans,

are susceptible to rabies infection. The rabies virus (RABV), a

member of the Lyssavirus genus, is commonly found in the

salivary glands of rabid animals and is excreted in their saliva.

When an infected animal bites, the virus enters the blood through a

fresh wound. Once introduced, RABV propagates along nerve tissue to

the brain, establishing itself within the central nervous system.

Subsequently, it spreads via nerves to the salivary glands, often

resulting in symptoms such as excessive salivation. The disease

initially manifests with excitation of the central nervous system,

characterized by irritability and aggression. Infected animals may

be highly contagious even before symptoms manifest (1). Despite effective vaccines for pre-

and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), rabies remains a significant

public health challenge, particularly in developing countries where

access to PEP is limited. Once clinical symptoms appear, rabies is

almost always fatal, underscoring the urgent need for effective

therapeutic interventions. Rabies is prevalent in >150

countries, mainly in Asia and Africa, where exposure without timely

PEP results in a mortality rate >99%. The RABV genome encodes

five essential proteins: Nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P),

matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G) and polymerase (L). These

proteins play critical roles in the viral life cycle, facilitating

attachment to host cells, entry via endocytosis, uncoating and

replication within the host cytoplasm.

Rabies poses a severe threat to human health and

economic stability, particularly in developing countries. According

to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2023 report, rabies causes

~59,000 human deaths annually, with 99% of cases resulting from dog

bites (2). The highest mortality

rates are reported in Asia and Africa, where access to PEP is often

limited. India alone accounts for almost 36% of global

rabies-related deaths, translating to an estimated 20,000

fatalities per year (3). By

contrast, developed nations have largely controlled rabies through

extensive vaccination programs and improved surveillance

measures.

The economic impact of rabies is profound, resulting

in over $8.6 billion in global annual losses. These losses stem

primarily from the costs associated with PEP, the loss of

livestock, and reduced productivity due to illness and death. The

financial burden of rabies is particularly acute for low-income

populations, where the average estimated cost of PEP can be

prohibitive (4). This situation

emphasizes the urgent need for novel therapeutic interventions, as

there are currently no effective antiviral treatments available

once clinical symptoms appear.

Recent epidemiological studies highlight the ongoing

challenges in controlling rabies in specific regions. For instance,

Malaysia has faced recurrent outbreaks of dog-mediated human

rabies, with a significant association between low vaccination

rates and increased incidence of cases (5). Another study conducted from 2015 to

2023 revealed that dogs accounted for 89.35% of confirmed rabies

cases in animals, emphasizing the importance of vaccination

campaigns (6). Therefore, rabies

continues to pose a significant public health threat globally,

particularly in developing regions where access to preventive

measures is limited. Enhanced vaccination efforts and improved

public health strategies are essential to combat this preventable

disease effectively. The urgent need for therapeutic interventions

for symptomatic patients further highlights the complexities

involved in managing rabies as a public health concern.

Effective vaccines have been developed for PEP;

timely administration can prevent rabies development following

exposure. PEP includes wound cleansing, vaccine administration and

equine or human rabies immune globulins (ERIG or HRIG). However,

PEP is ineffective once neurological signs appear. Although there

are rare reports of human rabies survivors, no established

therapies exist. Advances in treatment often stem from key studies

on rabies pathogenesis in animal models (7).

While vaccines have proven effective in preventing

rabies transmission, there is a pressing need for therapeutic

strategies to combat the disease in symptomatic patients. This need

is particularly critical in resource-limited settings where

vaccination coverage remains insufficient. The WHO has initiated

efforts to improve access to rabies vaccines through partnerships

with organizations such as Gavi, focusing on strengthening

surveillance and reporting systems while encouraging multisectoral

collaborations (8).

Conventional treatment methods include

pharmacological therapies, surgical intervention and physical

therapy. These methods have been the cornerstone of medical

practice for decades, as they are often backed by extensive

clinical research, providing established protocols for healthcare

providers. In addition, this approach allows for direct patient

assessment, enabling healthcare providers to tailor treatments

based on individual patient needs (9). In a number of cases, conventional

treatments can yield immediate results, such as pain relief or

symptom management. On the contrary, these approaches can be

resource-intensive, requiring significant time and personnel for

administration and monitoring, and can sometimes be costly in

resource-limited settings (10).

Therefore, treatment strategies have incorporated in silico

approaches, as they provide a better understanding of the treatment

design, disease modelling and drug discovery, which include

molecular docking, virtual screening and machine learning (ML)

algorithms that analyze large datasets to predict treatment

outcomes.

In silico methods can process vast amounts of

data quickly, significantly reducing the time required for drug

discovery and development compared to traditional laboratory

methods. These approaches can easily scale to accommodate larger

datasets without a corresponding increase in resource requirements.

This scalability is particularly beneficial in addressing complex

diseases with multifactorial causes in a cost-effective manner,

while minimizing laboratory work and animal testing. However,

computational predictions need to be validated through experimental

studies, as there is a risk of false positives or negatives. Their

effectiveness relies heavily on the availability and quality of

data. They may not always accurately reflect the complexities of

human biology or disease progression (11).

In recent years, computational methods have emerged

as powerful tools in drug discovery and vaccine design for viral

infections such as rabies. In silico approaches, such as

molecular docking, homology modelling, virtual screening, molecular

dynamics simulations and quantitative structure-activity

relationship (QSAR) models, offer cost-effective and time-efficient

means of identifying potential antiviral compounds and

understanding their mechanisms of action. These methods can predict

interactions between viral proteins and potential inhibitors,

facilitating targeted therapy development (12). However, systematic clinical

research into combination therapies faces challenges due to the

sporadic occurrence of rabies cases. There is a pressing need for

medical approaches that accelerate effective therapy development

through veterinary care and investigational treatments of naturally

infected dogs when appropriate. Understanding the pathogenesis of

RABV in both humans and dogs has advanced significantly, providing

critical insight into severe neurological dysfunction associated

with the virus. Of note, four disease processes need to be managed:

Viral propagation, neuronal degeneration, inflammation and systemic

compromise (13).

The present review aimed to provide a comprehensive

overview of recent advancements in in silico research

focused on RABV and focusses on novel ligand identification,

structural elucidation of key viral proteins, drug repurposing

strategies as potential treatments for rabies, and explores the

design of multi-epitope peptide vaccines. By emphasizing these

developments, we aim to illustrate the potential of computational

approaches in combating rabies and inspire further research in this

vital area. While the biological mechanisms of rabies are

well-documented, addressing its therapeutic challenges necessitates

innovative approaches. Computational methods, with their

cost-effectiveness and predictive capabilities, have emerged as a

powerful solution in the quest for novel treatments.

2. Overview of structure-based drug

discovery methods

Given the lack of effective treatments

post-infection, structure-based drug discovery offers a promising

avenue by exploiting detailed molecular insights into the key

proteins of the virus. In silico methods, which encompass

computer-based techniques, have become essential in drug discovery.

These methods utilize computational tools and algorithms to

predict, analyze and optimize interactions between ligands

(potential drug molecules) and biological targets, such as proteins

or nucleic acids. By simulating molecular interactions and

screening extensive libraries of compounds, in silico

approaches significantly expedite the identification of promising

drug candidates, while reducing the costs and time associated with

traditional experimental methods. Structure-based drug discovery

has emerged as a promising and efficient strategy for identifying

novel and potent drug candidates in a more efficient and

cost-effective manner than conventional methods (14). This approach relies on the

three-dimensional structures of biological protein targets to

elucidate the molecular basis of diseases. To virtually identify

drug candidates, several preparatory steps for proteins and

compounds are essential for obtaining accurate results. Key steps

include homology modelling, virtual screening, QSAR models and

pharmacophore modelling, molecular docking and molecular dynamics

simulations (12,15). Molecular docking predicts the

preferred orientation of one molecule when bound to another to form

a stable complex. By contrast, molecular dynamics simulations study

the physical movements of atoms and molecules, providing a dynamic

view of molecular interactions. These techniques are cost-effective

and precise enough to predict mechanical characteristics, optimize

structures, and simulate the natural motion of biological

macromolecules (16).

Structure-based virtual screening involves several computational

phases, including target and database preparation, docking,

post-docking analysis, and prioritization of compounds for testing.

Homology modelling predicts protein structures from amino acid

sequences by aligning them with known templates, constructing

models and refining them through various steps (14). QSAR models establish associations

between the properties of chemical substances and their biological

activities to predict the activities of new chemical entities.

Moreover, pharmacophore modelling identifies essential structural

features necessary for a molecule to interact with a specific

biological target, aiding in virtual screening and lead compound

optimization (15). An overview of

the in silico methods used in the drug discovery process,

with their advantages and disadvantages is provided in Table I.

| Table IIn silico methods,

applications and tools. |

Table I

In silico methods,

applications and tools.

| Method | Description | Application in

rabies drug discovery | Commonly used

tools | Advantages | Limitations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Molecular

docking | Predicts the

preferred binding orientation of a ligand (drug candidate) with a

target protein. | Identifies

potential inhibitors for rabies nucleoprotein (N), glycoprotein

(G), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). | AutoDock, AutoDock

Vina, SwissDock, Glide (Schrödinger), GOLD | Cost-effective,

high-throughput screening. | May not account for

protein flexibility and solvent effects. | (23,58) |

| Molecular dynamics

(MD) simulations | Simulates the

physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Evaluates the

stability and dynamic interactions of drug candidates with rabies

virus proteins. | GROMACS, AMBER,

CHARMM, NAMD | Provides insight

into binding stability and conformational changes. | Computationally

intensive, requires high-performance computing. | (12) |

| Virtual

screening | Screens large

compound libraries for potential drug candidates based on binding

affinity. | Identifies small

molecules with potential antiviral activity against rabies virus

proteins. | PyRx, Schrodinger's

Glide, MOE, OpenEye FRED, LigandScout | Rapidly analyzes

thousands of compounds. | Requires accurate

target structures for reliable predictions. | (12,15) |

| Homology

modeling | Predicts the 3D

structure of proteins when an experimentally determined structure

is unavailable. | Used to model the

structure of rabies virus RdRp, nucleoprotein, and glycoprotein for

drug discovery. | SWISS-MODEL,

MODELLER, Phyre2, I-TASSER | Provides structural

insights when crystal structures are unavailable. | Accuracy depends on

template selection and alignment quality. | (26) |

| Quantitative

structure- activity relationship (QSAR) models | Establishes

mathematical relationships between chemical properties and

biological activity. | Predicts the

effectiveness of new rabies antiviral compounds before experimental

testing. | KNIME, DeepChem,

PaDEL- Descriptor, ChemOffice, QSARINS | Enables

optimization of drug candidates. | Requires extensive

datasets for training reliable models. | (12,15) |

| Pharmacophore

modeling | Identifies

essential molecular features required for ligand- receptor

interactions. | Helps in the design

of novel inhibitors targeting rabies virus proteins. | LigandScout,

PharmaGist, Discovery Studio, MOE | Highlights key

functional groups for drug interaction. | May miss non-

obvious interactions not included in the model. | (12,58) |

3. Structural and functional insights into

rabies virus proteins

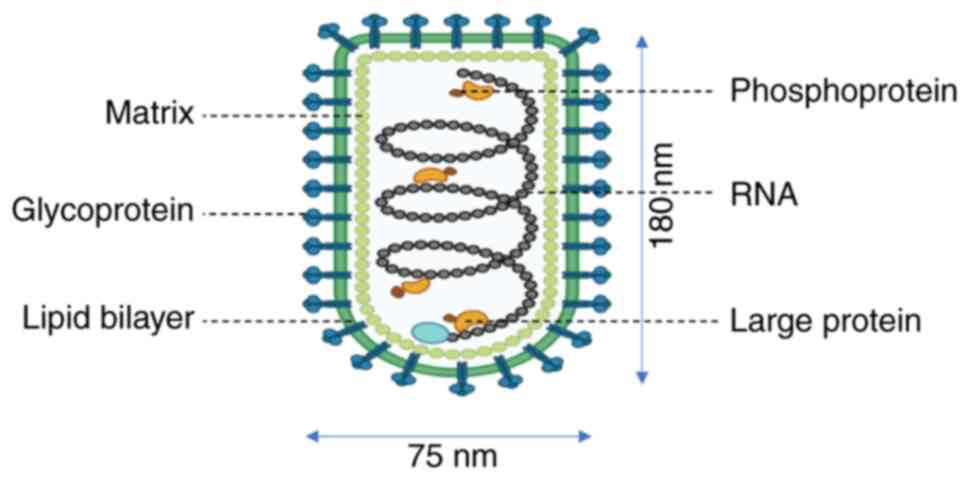

RABV, a member of the Rhabdoviridae family,

encodes five structural proteins: Nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein

(P), matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G) and the large

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L or RdRp) (Fig. 1). Each protein plays a critical

role in viral replication, immune evasion and pathogenesis.

Understanding their structural and functional properties provides

essential insight into antiviral drug targeting. The N protein

encapsulates the viral RNA genome, forming the ribonucleoprotein

complex crucial for viral transcription and replication, shielding

the viral genome from host immune responses (17). The G protein mediates viral entry

by interacting with host cell receptors, such as the nicotinic

acetylcholine receptor and p75 neurotrophin receptor. It is also

the primary target for neutralizing antibodies, rendering it a key

focus for vaccine and antiviral drug development (18). The L protein, in association with

the P protein, carries out viral genome replication and

transcription, rendering it a promising target for broad-spectrum

antivirals (19).

Computational approaches in targeting

RABV proteins

Modern computational techniques have significantly

advanced rabies antiviral research. Structure-based drug design,

homology modelling via SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/), molecular docking

using AutoDock Vina (https://vina.scripps.edu/) and GOLD (https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/discover/blog/gold-the-all-in-one-molecular-docking-package/),

and molecular dynamics simulations have provided valuable insight

into protein-ligand interactions. Additionally, artificial

intelligence (AI) and ML are enhancing ligand identification and

optimization, expediting therapeutic discoveries. However, in

vitro experiments to validate the in silico results are

mandatory for robust drug discovery.

Key viral targets for drug

discovery

Viral proteins serve as crucial targets in antiviral

drug discovery due to their vital roles in the viral life cycle,

including replication, transcription and host cell entry. Targeting

these proteins can disrupt viral propagation and provide effective

therapeutic strategies (19).

The nucleoprotein is critical for encapsulating

viral RNA and forming a ribonucleoprotein complex essential for

replication and transcription. Structural analysis (PDB ID: 2GTT)

has revealed its strong RNA-binding affinity, rendering it a viable

target for small-molecule inhibitors. Molecular docking studies

identified ZINC01530604 and ZINC01530605 as promising candidates

targeting phosphorylation sites essential for nucleoprotein

function. Additionally, QSAR modelling analyzed >450

physicochemical parameters, leading to the identification of

peptide inhibitors, such as P16b6, that can effectively bind to the

phosphoprotein and suppress viral replication (20). While molecular docking is a

powerful tool for narrowing down candidates, further validation

steps are essential for confirming antiviral activity.

The RABV virus glycoprotein (RVG) facilitates host

cell entry and neurotropism, making it a main antiviral target.

Docking studies have suggested polyethylene glycol 4000 as an

inhibitor, effectively blocking receptor binding sites to prevent

viral spread (21). Structural

studies have also highlighted conserved tyrosine and threonine

residues contributing to glycoprotein stability. Furthermore,

computational techniques have facilitated the identification of

neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, such as 523-11, which bind to

RVG and prevent membrane fusion (22).

RABV RdRp is essential for viral RNA synthesis.

Homology models based on vesicular stomatitis virus (PDB ID: 5A22)

have provided structural insight into its catalytic mechanism.

Molecular docking analyses identified compounds binding to key

catalytic residues (Met585, Glu620, Lys621, Trp622 and Glu696),

inhibiting polymerase activity. A virtual screening of 2,045

compounds from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) identified

several promising inhibitors with strong binding affinity to RdRp

active sites, supporting further experimental validation (23).

Thus, these viral proteins, nucleoprotein,

glycoprotein and RdRp, are promising targets for antiviral drug

discovery due to their critical functions in the viral lifecycle

and their amenability to targeted inhibition. Progress with

small-molecule inhibitors, peptides, and neutralizing antibodies

against these targets may lead to the development of effective

antiviral therapies. Hence, focusing drug discovery efforts on

critical viral proteins with validated roles in replication and

infection, supported by structural and computational studies, are

fundamental for developing potent antiviral agents that can

effectively disrupt viral propagation and combat viral

diseases.

Across the literature, there is a general consensus

that structure-based computational methods accelerate the

identification of antiviral candidates for RABV, particularly for

targets, such as nucleoprotein, glycoprotein and RdRp. However,

discrepancies remain as regards the translation of in silico

findings to in vitro and in vivo efficacy. This

emphasizes the necessity for integrated pipelines that combine

computational screening with experimental validation, a direction

increasingly advocated in recent reviews and original research

articles.

4. AI and ML in rabies treatment

The advent of ML and AI has markedly facilitated the

understanding of complex biological systems and accelerated the

drug discovery process. One area where ML/AI has played a vital

role is protein structure prediction, which is essential to

understanding the biological mechanisms involved in the disease.

DeepMind's AlphaFold is the game changer in this scenario,

surpassing all other existing tools and recognized as the recipient

of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (24). Secondly, the role of AI in drug

discovery has been monumental. In the field of RABV drug discovery,

these technologies facilitate the analysis of genetic,

epidemiological and pharmacological datasets to predict treatment

efficiency, optimize antiviral drugs and identify novel therapeutic

targets by significantly reducing the cost and time involved in

developing new rabies treatments. AI-based computational models are

speeding up the discovery of host factors and RABV proteins that

can serve as therapeutic targets by analyzing viral genomes and

host-pathogen interactions to detect the critical molecular

pathways essential for RABV replication (25). In addition, predicting the

conserved viral epitopes could enable the development of vaccines

or anti-viral drugs (26).

Likewise, AI also supports the identification of host proteins

involved in immune evasion or viral invasion that could open new

avenues in therapeutics (27).

Another area where AI is playing a transformative

role is in the development of antiviral drugs for rabies. ML

approaches enable rapid screening of millions of compounds to

identify leads as potential inhibitors of viral replication by

analyzing extensive molecular datasets and predicting drug-receptor

interactions, followed by lead optimization to enhance their

efficacy (28). Drug repurposing

is another interesting area of research where AI can expedite the

identification of FDA-approved drugs with activity against the RABV

(29). AI also predicts drug-virus

interactions, identifying promising antiviral candidates inhibiting

replication. Additionally, the amalgamation of AI and CRISPR

genome-editing technology is advancing research into RABV

evolution, diagnosis, and treatment (30). Together, these efforts are paving

the way for safer, more effective therapeutic options for rabies

prevention and treatment.

5. Drug repurposing

Research into the molecular basis of rabies, which

affects the central nervous system, has demonstrated that the virus

targets neurons, leading to severe neurological symptoms (31). Currently, the only available

treatment option is post-exposure prophylaxis, which comes with

important drawbacks, including high costs and complicated

administration. These limitations necessitate alternative

strategies where drug repurposing could benefit rabies treatment.

By re-examining existing drugs for novel therapeutic applications,

the drug development process can be accelerated with reduced cost

and potentially reveal new treatment pathways. Repurposed

medications may provide a more rapid route to clinical application,

addressing the urgent need for more accessible and effective

therapies for rabies (10).

In a previous study, notable candidates, such as

cidofovir, emtricitabine, famciclovir, acyclovir, and stavudine

were shown to exhibit potential efficacy against the RABV

glycoprotein (32). Advanced

docking analyses were conducted using the CB-Dock2 program to

assess these candidates. This sophisticated approach searched the

database of the server for template ligands with strong topological

similarity (FP2 ≥0.4) through an integrated homologous

template-based blind docking mechanism (32). Following this, cavity detection was

performed using an in-house technique known as FitDock to aid

molecular docking with specific templates. The docking analyses

identified five potential binding cavities for Emtricitabine within

the target protein, with volumes ranging from 7209 ų to 1703 Å

with significant binding affinities, varying from -5.0 to -6.1;

lower scores suggest stronger binding affinity. The root means

square deviation values were observed around 10 Å, and the hydrogen

bond count fluctuated around 25, indicating stable interactions

with limited conformational deviation and persistent hydrogen

bonding (32).

In addition to computational methods for drug

repurposing, the validation of these compounds is crucial for

establishing their efficacy against rabies. Repositioning already

approved medications can significantly lower drug development costs

and timelines, while reducing the likelihood of unexpected

side-effects. Computational repositioning allows for the rapid

screening of candidates in silico, which renders it an

attractive option for prioritizing potential treatments. In a

previous study, the ChEMBL library was filtered from 2,354,965

compounds down to 6,554 that had passed through any phase of

clinical trials to avoid cytotoxic inhibitors (33). The cryo-electron microscopy

(cryo-EM) structure of the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) strain

A2 polymerase (PDB: 6UEN) was prepared for AutoDock Vina docking

studies. Compounds with flexible ligand structures or poor binding

affinities were eliminated, narrowing the selection to 4,919

candidates. Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler was used for

interaction analyses with micafungin, trombopag, trovafloxacin,

azlocillin Na, trospium, amiodarone HCl, perflubron, mephenesin and

methadone. Among these candidates, micafungin demonstrated

exceptional promise with a binding affinity of -14.32 kcal/mol and

an inhibition constant of 0.0317 nM, outperforming existing

inhibitors, such as AZ-27 (0.47997 nM), ALS-8112 (2.56 nM) and

ribavirin (6.98 nM) (33). In

vitro assays further confirmed the efficacy of micafungin by

reducing RSV polymerase activity to only 29.6% of the control

levels; by contrast, verubecestat (97.4%), ribavirin (98.4%) and

ALS-8112 (89.5%) retained markedly higher levels of activity

compared with the control. These findings collectively demonstrate

that computational approaches can effectively identify promising

repurposed compounds for rabies treatment while validating their

efficacy through rigorous screening processes (33).

Phthalazine derivatives have gained attention in

recent times due to their pharmacological properties (34). Their unique structural

characteristics make them promising candidates in combating viral

infections. High-throughput screening methods have played a key

role in discovering compounds that inhibit RABV replication, while

maintaining low cytotoxicity. Comprehending the mechanisms of

action of these compounds is vital for augmenting their therapeutic

potential. Phthalazine and its derivatives, nitrogen-containing

heterocyclic compounds, have gathered attention in medicinal

chemistry due to its versatile pharmacological properties. Of note,

one phthalazine derivative compound, 7671954, was found to be

particularly effective against RABV infections across different

Lyssavirus species with low cytotoxicity (IC50 values <30

µM) (34). Experiments established

that these compounds inhibited viral replication by targeting the

replication complex (34).

Furthermore, these derivatives interact with host receptor, such as

the p75 neurotrophin receptor and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor,

both of which play critical roles in viral entrance, potentially

increasing immune responses while limiting viral interactions with

host cells (18).

In summary, drug repurposing provides a

cost-effective and accelerated path for rabies treatment,

identifying promising candidates such as emtricitabine,

famciclovir, acyclovir, stavudine and cidofovir. Computational

screening and high-throughput assays have enabled the rapid

identification of drugs with potent antiviral potential against

rabies. These approaches address the urgent need for affordable and

accessible therapies beyond current post-exposure prophylaxis,

which remains costly and limited in availability. The continued

research and validation of these repurposed drugs could transform

rabies management and save countless lives globally.

6. Multi-epitope peptide vaccines

Generally, drug discovery focuses on treatment

post-infection, whereas vaccines provide proactive protection.

Computational methods have facilitated vaccine design through

precise epitope mapping. Since viral entry is the key to infection,

the RABV glycoprotein (RABV-G) is mainly targeted for vaccine

development. Several immunoinformatic tools are utilized to

identify the antigenic sites and further design multiepitope

peptide vaccines (35).

The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) is employed to

predict epitopes based on the Bepipred Linear Epitope Prediction

2.0 method. Initial sequence analysis that includes antigenicity,

allergenicity and virulence assessments is carried out using

AllerTOP v2.0, DeepTMHMM, VirulentPred and VaxiJen. This is

followed by BLASTP analysis to ascertain no cross reactivity with

human proteins. Physico-chemical properties and structure

prediction studies are performed using Protparam, PSIPRED and

GalaxyRefine followed by the final prediction of immune response

prediction using C-ImmSim server. Studies were carried out using

this approach for RABV proteins (36,37).

In a previous study, AR16 and hPAB, two conserved

RABV peptides, were combined with Gp96 adjuvant to create an

oil-in-water emulsion. By day 14, the vaccine candidates produced

virus-neutralizing antibodies and were safe. By day 28, they peaked

at 5-6 IU/ml in mice and 7-9 IU/ml in beagles. The promise of

multi-epitope peptide vaccines for rabies prevention was

demonstrated by the 70-80% protective efficacy against a virulent

rabies strain in mice (36). In

another study, using computational immunoinformatic methods, B-cell

epitopes from the RABV glycoprotein and nucleoprotein were found

(37). The eukaryotic vector

pcDNA3.1(-) was used to express the highly antigenic areas after

they were put together into a multi-epitope construct. Oral

delivery was facilitated by adopting food-grade Escherichia

coli as a carrier. Experiments conducted both in vitro

and in vivo demonstrated that the vaccination could produce

a robust immune response in mice, markedly increasing survival

following viral challenge without causing any negative

side-effects. This method demonstrates a viable, scalable approach

to rabies prevention, especially in populations of wild animals

(37).

7. Phytochemical-based compound

candidates

In recent times, natural forms of therapy have

gained importance based on popular beliefs, skills, and indigenous

practices owing to their no-side-effect advantage. The role of

traditional medicine has taken a center stage, primarily including

plants as the source of innumerable compounds with enormous

therapeutic benefits (38).

Although this approach is used for rabies management, there are

limited data available to support the efficacy of these methods.

Phytochemicals provide an alternative approach for antiviral

treatment as they are known to inhibit viral replication (39).

Compounds such as coumarins, lignans, alkaloids,

flavonoids and terpenoids exhibit antioxidant activity and may

suppress viral genome activity. A previous study identified

anti-rabies phytochemicals from Salix subserrata and onion,

screened for toxicity using SwissADME and Protox-II servers. Among

the candidates, (S+)-catechin and kaempferol exhibited promising

binding interactions with RABV glycoprotein based on docking

results. (+)-Catechin displayed an improved binding affinity, full

fitness and estimated ΔG values than kaempferol with the formation

of conventional hydrogen bonds with the target protein, rendering

it a potential natural inhibitor against rabies; this demonstrates

the role of natural product-based drugs (40).

Likewise, dodecandrin from Phytolacca

dodecandra L'Hérit., a ribosomal inactivating protein, is

expected to have an antiviral effect by depurinating the

α-sarcin/ricin loop of the ribosomal RNA, thereby halting protein

synthesis and inhibiting viral replication (41). Datura metel Linn. contains

anticholinergic agents such as atropine, which can affect nervous

system function by acting as competitive antagonists of muscarinic

acetylcholine receptors. This blockade can regulate nervous system

activity, perhaps relieving neurological signs of rabies (42). Salix subserrata and

Silene macroselen were also previously investigated for the

ability of their extracts to extend the survival rates of mice

infected with rabies, although no specific bioactive compounds were

reported (40). Although these

plants have exhibited some potential in laboratory settings, they

have not been proven effective for human rabies treatment, setting

the stage for additional pharmacological and clinical studies

(9). Additionally, salviifoside A

from Alangium salviifolium, was previously demonstrated to

exhibit potential in selectively inhibiting RVG interactions with

promising binding scores derived from docking analyses against RVG

protein structures obtained from UniProt (Accession no. A3RM22)

(43). That study utilized

homology modelling with SWISS-MODEL to create potential structures

for docking analysis.

In summary, phytochemical-derived compounds present

an encouraging and diverse pool of natural antiviral substances

with possible activity against RABV targets; however, their

therapeutic promise has yet to be definitively confirmed by

thorough pharmacological and clinical trials to convert these

initial results into efficient human therapies. An overview of the

type of ligands, their targets and the mechanism of action is

presented in Table II.

| Table IIIdentified ligands, drug repurposing

and vaccine design. |

Table II

Identified ligands, drug repurposing

and vaccine design.

| Compound/drug | Type | Target protein | Binding affinity

(Kcal/mol) | Predicted effect/

mechanism of action | In silico

method used | (Refs.) |

|---|

| ZINC01530604 | Ligand | Nucleoprotein

(N) | -7.5 | Inhibits viral

replication | Molecular

docking | (21) |

| ZINC01530605 | Ligand | Nucleoprotein

(N) | -7.2 | Inhibits viral

replication | Molecular

docking | (21) |

| (+)-Catechin | Phytochemical | Nucleoprotein

(N) | -8.1 | Natural

inhibitor | Molecular

docking | (40) |

| Kaempferol | Phytochemical | Nucleoprotein

(N) | -7.9 | Natural

inhibitor | Molecular

docking | (40) |

| Emtricitabine | Drug

repurposing | Polymerase (L) | -7.8 | Potential

inhibitor | Molecular

docking | (32) |

| Famciclovir | Drug

repurposing | Polymerase (L) | -7.5 | Potential

inhibitor | Molecular

docking | (32) |

| Multi-epitope

peptide 1 | Vaccine design | Various | Varies | Induces immune

response | IEDB, Bepipred | (36,37) |

| Multi- epitope

peptide 2 | Vaccine design | Various | Varies | Induces immune

response | IEDB, Bepipred | (36,37) |

8. RNA-based therapeutics

RNA-based therapeutics have emerged as a promising

strategy for the prevention and treatment of rabies, leveraging

advanced vaccine platforms such as mRNA and self-replicating RNA

(srRNA) technologies.

RNA interference (RNAi)

Initial studies investigated RNAi as a

post-transcriptional gene silencing mechanism against rabies. A

previous study demonstrated that there was a 5-fold decrease in the

RABV titer in BHK-21 cells by using short-interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

against the mRNA of the N protein (44). Research has highlighted that

microRNAs can significantly reduce genomic RNA and mRNA of the

proteins in replication and pathogenesis, indicating the potential

of RNAi as an antiviral agent (44).

Animal studies have supported these findings. Gupta

et al (14) documented

extensive protection in mice intracerebrally infected with an

adenovirus vector expressing siRNA coding-sequences against the N

and L proteins, and subsequent challenge with fixed RABV. In

addition, another study found decreased N protein synthesis, fewer

clinical signs and reduced morbidity in mice intracerebrally

inoculated with plasmids encoding for siRNAs against the N protein

prior to challenge with the CVS fixed strain of RABV (45). Aptamers and siRNAs were tested by

coupling them to each other and administering them with

Lipofectamine. One of the siRNAs (N53) produced an 80.13% decrease

in viral RNA, while aptamer UPRET 2.03 led to a 61.3% decrease when

applied alone at 2 h post-infection (p.i). Chimera UPRET 2.03-N8

(aptamer-siRNA) at 24 h p.i. resulted in 36.5% inhibition of viral

replication (46).

mRNA vaccines

mRNA technology has emerged as a rapid and scalable

platform for the development of a rabies vaccine. In a previous

study, an optimized mRNA vaccine construct (LVRNA001) encoding the

RABV glycoprotein (RABV-G) induced neutralizing antibody titers and

a robust Th1 cell-mediated immune response in mice (47). Protection against lethal challenge

with RABV was demonstrated in mice and dogs. The post-exposure

immunization of dogs with LVRNA001 yielded a 100% survival rate,

compared to 33.33% for the inactivated vaccine (47).

The thermostability of mRNA rabies vaccines was also

explored in another study. It was established that extended storage

at temperatures between -80 and +70˚C, or exposure to alternating

temperatures, did not impair the protective potential of the

vaccine in mice, suggesting that a rigorous cold chain may not be

necessary (48). Another study

focused on nucleoside-modified mRNA-lipid nanoparticle (LNP)

vaccines. A single immunization of RABV-G mRNA-LNP in mice induced

stronger humoral and T-cell immune responses than three doses of an

inactivated vaccine. This single-dose mRNA vaccine provided

complete protection against rabies, with the immune response

persisting for at least 25 weeks, and possibly longer with a

two-dose regimen (49).

CureVac AG engineered a RABV (RABV) mRNA vaccine,

CV7201, using the cationic protein protamine to encapsulate mRNA

that encodes the RABV glycoprotein. CV7201 was thermostable and

effectively elicited a WHO-defined antibody response in 70.3% of

subjects through three intradermal immunizations (Clinical trial

no. NCT02241135). Optimizing the LNP formulation from CV7201,

CureVac AG engineered CV7202, which employs the identical mRNA

antigen as CV7201. The optimized LNP contains an ionizable amino

lipid, a PEG-lipid-modified one, phospholipid and cholesterol

(50). CV7202 exhibited acceptable

tolerance in a clinical trial (Clinical trial no. NCT03713086)

(50). Stokes et al

(51) used a cationic nanoemulsion

to encapsulate saRNA coding for alphavirus RNA-dependent RNA

polymerase and the rabies glycoprotein G.

RNA-based adjuvants

The application of RNA adjuvants to boost the

immunogenicity of rabies vaccines has also been investigated

(52). A first-in-concept human

study evaluated the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of the

TLR 7/8/RIG-I agonist RNA adjuvant CV8102, used alone or blended

with a commercial rabies vaccine (Rabipur®). The results

revealed that CV8102 was safe and well-tolerated, with doses of 25

and 50 µg markedly increasing the immunogenicity of reduced doses

of the rabies vaccine (52).

Consequently, RNA-based therapeutics, including RNAi, mRNA vaccines

and RNA-based adjuvants, exhibit tremendous potential in developing

rabies prevention and treatment methods, with further research

aimed at maximizing their efficacy, safety and accessibility for

global use.

9. Regional variations and implications for

treatment

Understanding the genetic diversity of the RABV

(Table III) is crucial for

designing effective vaccines. A previous study analyzing 50

dog-brain samples from suspected rabies cases in India provided

insight into regional viral variations (53). PCR screening targeting the

nucleoprotein (N) and glycoprotein (G) genes, followed by

sequencing, revealed that six isolates from Mumbai belonged to a

single Arctic lineage which traced back to an Indian lineage I from

2006. Bayesian coalescent analysis estimated the time to the most

recent common ancestor (TMRCA) for these sequences to be 1993,

indicating long-standing geographic clustering. These phylogenetic

data underscore the importance of tracking viral evolution for

epidemiological studies and vaccine development (53). Sequence analysis further revealed

amino acid polymorphisms in G-protein epitopes, influencing

antigenicity and pathogenicity. These findings highlight the

necessity for region-specific vaccine strategies to account for

genetic variations in circulating RABV strains (53).

| Table IIIRabies virus strains and

therapeutics |

Table III

Rabies virus strains and

therapeutics

| Strain | Geographical

location | Host | Genetic

variations | Impact on

pathogenicity | Target for

therapeutics | Therapeutic

approach (Refs.) |

|---|

| RABV1 | Africa | Domestic

animals | Single nucleotide

polymorphisms | Increased virulence

in certain strains | Nucleoprotein

(N) | Drug/ligand

discovery (64-66) |

| RABV2 | Asia | Bats | Insertions and

deletions | Variable

pathogenicity | Glycoprotein

(G) | Vaccine design

(64-66) |

| RABV3 | Americas | Wild animals | Amino acid

substitutions | Reduced efficacy of

some vaccines | Polymerase (L) | Drug repurposing

(64-66) |

10. Bioinformatics and integrative

strategies to fight rabies virus

Computational studies play a critical role in

decoding the intricacies of RABV pathogenesis. Research into

intrinsically disordered protein regions of the RABV proteome has

yielded key insights (51). High

intrinsic disorder levels in the phosphoprotein (P-protein) and

nucleoprotein (N-protein) are linked to Negri body formation and

host immune suppression. Proteomics analysis of highly purified

RABV (RABV) has revealed 47 host proteins that become entrapped

inside viral particles upon assembly. Of these, 11 are highly

disordered. A comprehensive study on five of these highly

disordered mouse proteins, neuromodulin, Chmp4b, DnaJB6, Vps37B and

Wasl, utilized bioinformatics tools such as FuzDrop, D2P2, UniProt,

RIDAO, STRING, AlphaFold and ELM to investigate their intrinsic

disorder propensity (54). These

disordered host proteins appear to play a major role in RABV

pathogenicity, immune evasion, and possibly resistance to antiviral

drugs. That study highlights the complex interplay between virus

and host, in which intrinsic disorder plays a key role in viral

pathogenic processes. This suggests that these intrinsically

disordered proteins and their corresponding host interactions might

be good candidates for therapeutic targets (54).

In addition, dysregulation in the matrix (M) protein

could play a role in viral budding and transmission, affecting the

capacity of the virus to spread. Phylogenetic analysis, comparing

RABV isolates from different host species and geographic regions,

has revealed clear patterns of clustering consistent with

host-specific adaptation of the virus (55). These patterns highlight the

ecological niche of Lyssavirus, which is strongly shaped by their

mammalian hosts, with implications for transmission dynamics and

vaccine development.

Overcoming limitations of in silico

approaches

While in silico approaches have

revolutionized vaccine and drug discovery, it is important to

recognize their limitations. One of the main challenges is the

predictive reliability and accuracy of computational models, which

are highly dependent on structural information. Flaws in this

information, due to low-resolution inputs or errors in homology

modelling, can undermine the efficacy of the models. Moreover,

molecular docking and dynamics simulation tend to over-simplify

biological interactions with the result of predictions being often

at variance from actual practice. Incorporating high-resolution

experimental information, e.g., cryo-electron microscopy, can

effectively improve the fidelity of such models.

A key aspect of enhancing in silico

approaches is strengthening the connection between computational

methods and in vitro and in vivo confirmations. The

inability of most predicted candidates to succeed experimentally

demonstrates the need to improve the practical applicability of

predictions. Additionally, present computational models lack

consideration of host-pathogen interactions, immune systems, or

PK/PD profiles, which are critical aspects. Using systems biology

methods and AI-based simulations can make predictions more

biologically relevant. Computational complexity and accessibility

are also major challenges. Sophisticated approaches, including

molecular dynamics simulations and quantum chemistry calculations,

are computationally costly and hence scale poorly. Optimizing

parallel processing algorithms and utilizing cloud-based platforms

can help overcome these limitations. Furthermore, most

sophisticated tools need specialized skills and hence access is

restricted in low-resource environments where rabies is endemic.

Providing improved user interfaces and training programs can

facilitate access.

The use of combined in silico and in

vitro approaches is crucial in the design of novel rabies

therapeutics. Computational methods, such as molecular dynamics

simulation and QSAR models, enable the prediction of the behavior

of putative drug candidates before they are synthesized (56-60).

These models can screen large compound libraries, thus accelerating

the identification of lead candidates while reducing drug

development time and costs. In addition, in silico

approaches can model RABV interactions with host cells, providing

insight into the life cycle of the virus and identifying novel

therapeutic targets. The synergy of computational prediction and

experimental confirmation is central to expediting the development

of useful rabies vaccines and treatments.

Translation to practical

application

Even with significant success in the use of

computational resources towards therapeutic interventions for

rabies, the translation of these in silico discoveries into

viable treatments is a challenge. To address this issue, tackling

the underreporting and misdiagnosis of cases, particularly in rural

locations in endemic nations, calls for the creation of affordable,

simple, and usable point-of-care diagnostic devices. Strengthening

surveillance systems with a view to collecting accurate data in a

timely manner is indispensable for successful control of rabies

(61). Likewise, a One Health

approach can be adopted which was proven successful in several

countries such as Bhutan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka (62). Further improvements in the

prediction accuracy of epidemiological models, by incorporating

real-time data and environmental factors, can result in more

efficient resource deployment and enhanced predictive capabilities.

Public education programs for raising awareness and adherence to

rabies prevention strategies, like dog vaccination and prompt

post-exposure prophylaxis, are also essential (63).

Finally, bioinformatics and computational approaches

are crucial for progressing the knowledge on the pathogenesis of

RABV and establishing efficient strategies for prevention and

treatment. Overcoming the disconnect between computational

prediction and experimental investigations is necessary for

bridging in silico discovery and practical implementation

and, eventually mitigating the global disease burden of rabies.

11. Conclusion and future perspectives

Addressing rabies at the therapeutic level remains a

major scientific and public health challenge, particularly in

regions with limited access to post-exposure interventions. While

vaccines have substantially reduced transmission, effective

treatments for symptomatic cases are still lacking. The present

review highlighted how computational tools are transforming the

drug discovery landscape for rabies by enabling the exploration of

novel targets and mechanisms. Notably, in silico platforms

have facilitated the rational design of peptide vaccines, the

identification of antiviral leads, and re-evaluation of existing

drug libraries with improved precision and efficiency. However, the

success of these approaches centers on their integration with

experimental validation pipelines. Future efforts are required to

prioritize translational studies, interdisciplinary collaborations

and capacity building in endemic regions to harness the full

potential of bioinformatics-driven research. Ultimately, a

data-driven, systems-level approach may provide the most promising

route toward effective and equitable rabies control.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

RR drafted the manuscript. SS contributed to the

conceptualization of the study, assisted in drafting the manuscript

and supervised the study. Both authors were involved in the

literature search. Both authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Nayak JB, Chaudhary JH, Bhavsar PP,

Anjaria PA, Brahmbhatt MN and Mistry UP: Rabies: Incurable

biological threat. In: Zoonosis of Public Health Interest.

IntechOpen. London, 2022.

|

|

2

|

World Health organization (WHO). In: WHO

Expert Consultation on Rabies: Third Report. Abela-Ridder B (ed).

WHO, Geneva, 2018.

|

|

3

|

World Health Organization (WHO). Rabies -

India. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/india/health-topics/rabies.

|

|

4

|

World Health Organization (WHO). Rabies.

WHO, Geneva, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies.

|

|

5

|

Wada YA, Mazlan M, Noordin MM, Mohd-Lila

MA, Fong LS, Ramanoon SZ and Zahli NIU: Rabies epidemiology in

Malaysia (2015-2023): A cross-sectional insights and strategies for

control. Vaccine. 42(126371)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yu Q, Liu J, Zhao H, Chen H, Xiang Y, Liu

Q, Mei L, Zhang W, Cheng M, Li Z, et al: Canine rabies vaccination,

surveillance and public awareness programme in Beijing, China,

2014-2024. Bull World Health Organ. 103:247–254. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Gnanadurai CW, Huang CT, Kumar D and Fu

ZF: Novel approaches to the prevention and treatment of rabies. Int

J Virol Stud Res. 3:8–16. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

WHO Rabies Modelling Consortium. The

potential effect of improved provision of rabies post-exposure

prophylaxis in Gavi-eligible countries: A modelling study. Lancet

Infect Dis. 19:102–111. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Beasley EA, Wallace RM, Coetzer A, Nel LH

and Pieracci EG: Roles of traditional medicine and traditional

healers for rabies prevention and potential impacts on

post-exposure prophylaxis: A literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis.

16(e0010087)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sreenivasan N, Li A, Shiferaw M, Tran CH,

Wallace R, Blanton J, Knopf L, Abela-Ridder B and Hyde T: Working

group on Rabies PEP logistics. Overview of rabies post-exposure

prophylaxis access, procurement and distribution in selected

countries in Asia and Africa, 2017-2018. Vaccine. 37 (Suppl

1):A6–A13. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Uzundurukan A, Nelson M, Teske C, Islam

MS, Mohamed E, Christy JV, Martin HJ, Muratov E, Glover S and Fuoco

D: Meta-analysis and review of in silico methods in drug discovery

- part 1: Technological evolution and trends from big data to

chemical space. Pharmacogenomics J. 25(8)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Alazman I, Mishra MN, Alkahtani BS and

Goswami P: Computational analysis of rabies and its solution by

applying a fractional operator. Appl Math Sci Eng.

32(2340607)2024.

|

|

13

|

Knobel DL, Jackson AC, Bingham J, Ertl

HCJ, Gibson AD, Hughes D, Joubert K, Mani RS, Mohr BJ, Moore SM, et

al: A one medicine mission for an effective rabies therapy. Front

Vet Sci. 9(867382)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Gupta Y, Savytskyi OV, Coban M, Venugopal

A, Pleqi V, Weber CA, Chitale R, Durvasula R, Hopkins C, Kempaiah P

and Caulfield TR: Protein structure-based in-silico approaches to

drug discovery: Guide to COVID-19 therapeutics. Mol Aspects Med.

91(101151)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Prinsa Saha S, Bulbul MZH, Ozeki Y, Alamri

MA and Kawsar SMA: Flavonoids as potential KRAS inhibitors: DFT,

molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation and ADMET

analyses. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 26:955–992. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Alamri MA, Prinsa Kawsar SMA and Saha S:

Exploring marine-derived bioactive compounds for dual inhibition of

Pseudomonas aeruginosa LpxA and LpxD: Integrated bioinformatics and

cheminformatics approaches. Mol Divers. 29:1033–1047.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wang PH and Xing L: The roles of rabies

virus structural proteins in immune evasion and implications for

vaccine development. Can J Microbiol. 70:461–469. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lian M, Hueffer K and Weltzin MM:

Interactions between the rabies virus and nicotinic acetylcholine

receptors: A potential role in rabies virus induced behavior

modifications. Heliyon. 8(e10434)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Nakagawa K, Kobayashi Y, Ito N, Suzuki Y,

Okada K, Makino M, Goto H, Takahashi T and Sugiyama M: Molecular

function analysis of rabies virus RNA polymerase L protein by using

an L gene-deficient virus. J Virol. 91:e00826–17. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lu Y, Cheng L and Liu J: Optimisation of

inhibitory peptides targeting phosphoprotein of rabies virus. Int J

Pept Res Ther. 26:1043–1049. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Tomar NR, Singh V, Marla SS, Chandra R,

Kumar R and Kumar A: Molecular docking studies with rabies virus

glycoprotein to design viral therapeutics Indian J Pharm. Sci.

72:486–490. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Yang F, Lin S, Ye F, Yang J, Qi J, Chen Z,

Lin X, Wang J, Yue D, Cheng Y, et al: Structural analysis of rabies

virus glycoprotein reveals pH-dependent conformational changes and

interactions with a neutralizing antibody. Cell Host Microbe.

27:441–453.e7. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Kiriwan D and Choowongkomon K: In silico

structural elucidation of the rabies RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

(RdRp) toward the identification of potential rabies virus

inhibitors. J Mol Model. 27(183)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T,

Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Žídek A,

Potapenko A, et al: Highly accurate protein structure prediction

with AlphaFold. Nature. 596:583–589. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sahoo D, Katkar GD, Khandelwal S,

Behroozikhah M, Claire A, Castillo V, Tindle C, Fuller M, Taheri S,

Rogers TF, et al: AI-guided discovery of the invariant host

response to viral pandemics. EbioMedicine.

68(103390)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Yurina V and Adianingsih OR: Predicting

epitopes for vaccine development using bioinformatics tools. Ther

Adv Vaccines Immunother. 10(25151355221100218)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Elste J, Saini A, Mejia-Alvarez R, Mejía

A, Millán-Pacheco C, Swanson-Mungerson M and Tiwari V: Significance

of artificial intelligence in the study of virus-host cell

interactions. Biomolecules. 14(911)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Tarasova O and Poroikov V: Machine

learning in discovery of new antivirals and optimization of viral

infections therapy. Curr Med Chem. 28:7840–7861. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Almulhim M, Ghasemian A, Memariani M,

Karami F, Yassen ASA, Alexiou A, Papadakis M and Batiha GE: Drug

repositioning as a promising approach for the eradication of

emerging and re-emerging viral agents. Mol Divers: Mar 18, 2025

(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

30

|

Koujah L, Shukla D and Naqvi AR:

CRISPR-Cas based targeting of host and viral genes as an antiviral

strategy. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 96:53–64. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Fooks A, Cliquet F, Finke S, Freuling C,

Hemachudha T, Mani RS, Müller T, Nadin-Davis S, Picard-Meyer E,

Wilde H and Banyard AC: Rabies. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

3(17091)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hameed A: Drug repurposing for rabies

treatment: A computational analysis of 14 agents. ChemRxiv,

2024.

|

|

33

|

Xu E, Park S, Calderon J, Cao D and Liang

B: In silico identification and in vitro validation of repurposed

compounds targeting the RSV polymerase. Microorganisms.

11(1608)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Perraud V, Vanderhoydonck B, Bouvier G,

Dias de Melo G, Kilonda A, Koukni M, Jochmans D, Rogée S, Ben

Khalifa Y, Kergoat L, et al: Mechanism of action of phthalazinone

derivatives against rabies virus. Antiviral Res.

224(105838)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Abdulhameed Odhar H, Hashim AF, Humadi SS

and Ahjel SW: Design and construction of multi epitope-peptide

vaccine candidate for rabies virus. Bioinformation. 19:167–177.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Niu Y, Liu Y, Yang L, Qu H, Zhao J, Hu R,

Li J and Liu W: Immunogenicity of multi-epitope-based vaccine

candidates administered with the adjuvant Gp96 against rabies.

Virol Sin. 31:168–175. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ding Y, Gao Y, Chen R, Zhang Z, Li Q, Jia

T, Zhang T, Xu R, Shi W, Chen L, et al: Development of a novel

multi-epitope oral DNA vaccine for rabies based on a food-borne

microbial vector. Int J Biol Macromol. 255(128085)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Rizvi SAA, Einstein GP, Tulp OL, Sainvil F

and Branly R: Introduction to traditional medicine and their role

in prevention and treatment of emerging and re-emerging diseases.

Biomolecules. 12(1442)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Behl T, Rocchetti G, Chadha S, Zengin G,

Bungau S, Kumar A, Mehta V, Uddin MS, Khullar G, Setia D, et al:

Phytochemicals from plant foods as potential source of antiviral

agents: An overview. Pharmaceuticals (Basel).

14(381)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Deressa A, Hussen K, Abebe D and Gera D:

Evaluation of the efficacy of crude extracts of Salix subserrata

and Silene macroselen for the treatment of rabies in Ethiopia.

Ethiop Vet J. 14:1–16. 2011.

|

|

41

|

Admasu P, Deressa A, Mengistu A, Gebrewold

G and Feyera T: In vivo antirabies activity evaluation of

hydroethanolic extract of roots and leaves of Phytolacca

dodecandra. Glob Vet. 12:12–18. 2014.

|

|

42

|

Roy S, Samant L, Ganjhu R, Mukherjee S and

Chowdhary A: Assessment of in vivo antiviral potential of Datura

metel Linn. extracts against rabies virus. Pharmacogn Res.

10:109–112. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Maheswari UM, Ebenezer NS and Priyakumari

JC: An In silico approach: Homology modelling and docking studies

of rabies virus glycoprotein with salviifoside a of alangium

salviifolium. Int J Sci Res. 6:531–534. 2017.

|

|

44

|

Yang YJ, Zhao PS, Zhang T, Wang HL, Liang

HR, Zhao LL, Wu HX, Wang TC, Yang ST and Xia XZ: Small interfering

RNAs targeting the rabies virus nucleoprotein gene. Virus Res.

169:169–174. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Trobaugh DW and Klimstra WB: MicroRNA

regulation of RNA virus replication and pathogenesis. Trends Mol

Med. 23:80–93. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Scott TP and Nel LH: Rabies prophylactic

and treatment options: An in vitro study of siRNA- and

aptamer-based therapeutics. Viruses. 13(881)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Li J, Liu Q, Liu J, Wu X, Lei Y, Li S,

Zhao D, Li Z, Luo L, Peng S, et al: An mRNA-based rabies vaccine

induces strong protective immune responses in mice and dogs. Virol

J. 19(184)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Stitz L, Vogel A, Schnee M, Voss D, Rauch

S, Mutzke T, Ketterer T, Kramps T and Petsch B: A thermostable

messenger RNA based vaccine against rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis.

11(e0006108)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Bai S, Yang T, Zhu C, Feng M, Zhang L,

Zhang Z, Wang X, Yu R, Pan X, Zhao C, et al: Corrigendum: A single

vaccination of nucleoside-modified rabies mRNA vaccine induces

prolonged highly protective immune responses in mice. Front

Immunol. 14(1146466)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Aldrich C, Leroux-Roels I, Huang KB, Bica

MA, Loeliger E, Schoenborn-Kellenberger O, Walz L, Leroux-Roels G,

von Sonnenburg F and Oostvogels L: Proof-of-concept of a low-dose

unmodified mRNA-based rabies vaccine formulated with lipid

nanoparticles in human volunteers: A phase 1 trial. Vaccine.

39:1310–1318. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Stokes A, Pion J, Binazon O, Laffont B,

Bigras M, Dubois G, Blouin K, Young JK, Ringenberg MA, Ben

Abdeljelil N, et al: Nonclinical safety assessment of repeated

administration and biodistribution of a novel rabies

self-amplifying mRNA vaccine in rats. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol.

113(104648)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Doener F, Hong HS, Meyer I, Tadjalli-Mehr

K, Daehling A, Heidenreich R, Koch SD, Fotin-Mleczek M and

Gnad-Vogt U: RNA-based adjuvant CV8102 enhances the immunogenicity

of a licensed rabies vaccine in a first-in-human trial. Vaccine.

37:1819–1826. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Pharande RR, Majee SB, Gaikwad SS,

Moregoankar SD, Bannalikar AK, Doiphode A, Gandge R, Dighe D, Ingle

S and Mukherjee S: Evolutionary analysis of rabies virus using the

partial nucleoprotein and glycoprotein gene in Mumbai region of

India. J Gen Virol. 102:2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Ashraf HN and Uversky VN: Intrinsic

disorder in the host proteins entrapped in rabies virus particles.

Viruses. 16(916)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Cai M, Liu H, Jiang F, Sun Y, Wang W, An

Y, Zhang M, Li X, Liu D, Li Y, et al: Analysis of the evolution

infectivity and antigenicity of circulating rabies virus strains.

Emerg Microbes Infect. 11:1474–1484. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Quayum ST, Esha NJI, Siraji S, Abbad SSA,

Alsunaidi ZHA, Almatarneh MH, Rahman S, Alodhayb AN, Alibrahim KA,

Kawsar SMA and Uddin KM: Exploring the effectiveness of flavone

derivatives for treating liver diseases: Utilizing DFT, molecular

docking, and molecular dynamics techniques. MethodsX.

12(102537)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Saha S, Gupta V, Hossain A, Prinsa P,

Ferdous J, Lokhande KB, Jakhmol V and Kawsar Sarkar MA:

Computational Investigation of the Unveils NSD2 Inhibition

Potential of Berberis vulgaris, Sambucus nigra, and Morus alba

through Virtual Screening, Molecular Docking, MD Simulation, and

DFT Analyses, Karbala International J. Modern Sci. 11:129–143.

2025.

|

|

58

|

M A Kawsar S, Hosen MA, Ahmad S, El Bakri

Y, Laaroussi H, Ben Hadda T, Almalki FA, Ozeki Y and Goumri-Said S:

Potential SARS-CoV-2 RdRp inhibitors of cytidine derivatives:

Molecular docking, molecular dynamic simulations, ADMET, and POM

analyses for the identification of pharmacophore sites. PLoS One.

17(e0273256)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Saha S, Prinsa and Sarkar MAK:

Natural Flavonoids as Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis

Inhibitor: Virtual Screening, Molecular Docking, MD Simulation,

MMPBSA, Density Functional Theory, Principal Component, and Gibbs

Free Energy Landscape Analyses. Chem Biodiv.

22(e202402521)2025.

|

|

60

|

Karim T, Almatarneh MH, Rahman S, Alodhayb

AN, Albrithen H, Md. Hossain MM, Sarkar M. A. Kawsar, Poirier RA

and Uddin KM: In silico prediction of antibacterial activity of

quinolone derivatives. ChemistrySelect. 9(e202402780)2024.

|

|

61

|

Sudarshan MK and Ashwath Narayana DH:

Appraisal of surveillance of human rabies and animal bites in seven

states of India. Indian J Public Health. 63 (Supplement):S3–S8.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Acharya KP, Acharya N, Phuyal S, Upadhyaya

M and Lasee S: One-health approach: A best possible way to control

rabies. One Health. 10(100161)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Changalucha J, Steenson R, Grieve E,

Cleaveland S, Lembo T, Lushasi K, Mchau G, Mtema Z, Sambo M, Nanai

A, et al: The need to improve access to rabies post-exposure

vaccines: Lessons from Tanzania. Vaccine. 37 (Suppl 1):A45–A53.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Bourhy H, Reynes JM, Dunham EJ, Dacheux L,

Larrous F, Huong VTQ, Xu G, Yan J, Miranda MEG and Holmes EC: The

origin and phylogeography of dog rabies virus. J Gen Virol. 89 (Pt

11):2673–2681. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Rupprecht CE, Hanlon CA and Hemachudha T:

Rabies re-examined. Lancet Infect Dis. 2:327–343. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Banyard AC, Evans JS, Luo TR and Fooks AR:

Lyssaviruses and bats: Emergence and zoonotic threat. Viruses.

6:2974–2990. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|