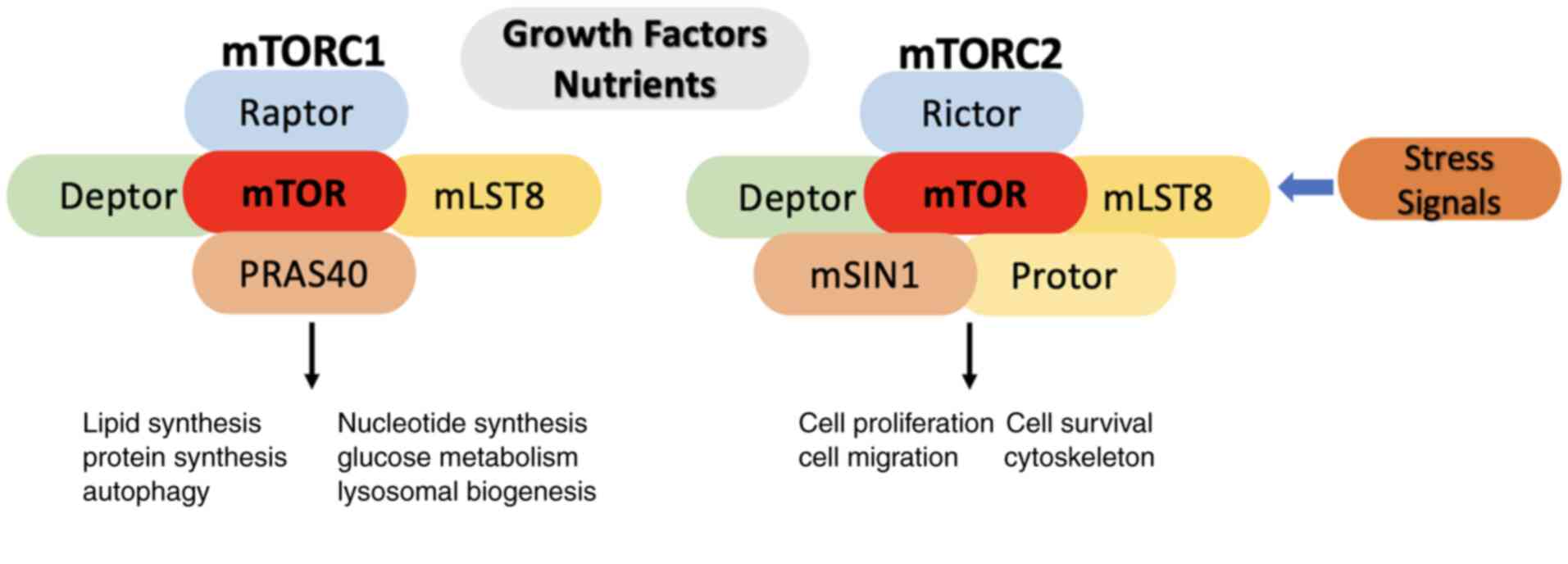

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) plays a

critical role in regulating cellular metabolism by integrating

signals from nutrients, growth factors and the environment. mTOR

exists in two distinct mTOR complexes (mTORCs), mTORC1 and mTORC2,

which are conserved across species from yeast to humans. mTORC1 is

a protein complex that consists of mTOR, Raptor, Deptor, mLST8, and

PRAS40. It is the primary target of the drug rapamycin that

allosterically reduces its activity, while mTORC2 consists of mTOR,

Debtor, Raptor, mLST8, mSIN1 and Protor, and its inhibition occurs

indirectly (1-4)

(Fig. 1A). Rapamycin and its

analogs are currently utilized in clinical settings. They are being

tested for various conditions, including cancer, immune disorders,

metabolic syndromes and neurodegenerative diseases, exhibiting

potential as anti-aging agents that may enhance human and animal

health. Insight into mTOR-mediated metabolic shifting in target

cells, such as tumors and immune cells in their microenvironments,

can significantly advance the development of targeted therapeutic

approaches. The proper functioning of mTORC1 and mTORC2 is

essential for maintaining metabolic equilibrium, preventing

diseases and extending the health area (5). Studies have revealed that

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) affects cancer cell metabolism

through several mechanisms. The activation of AMPK has been

correlated with the inhibition of aerobic glycolysis which is

well-known as the Warburg Effect. The Warburg effect has been known

as one of the cancer hallmarks and is characterized by enhanced

glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen (5-7).

This pathway stimulates the catabolic metabolic processes, which

promote cancer cell metabolism to switch to energy preservation

under severe stress conditions. AMPK stimulation has been shown to

utilize anti-proliferation and propagation effects in various tumor

types (6).

The importance of cancer cell metabolism

orchestrated through AMPK/mTOR cascades is an attractive avenue for

innovative cancer therapies and highlights the need for the

understanding of these signaling pathways further to advance

wide-ranging combination therapy approaches. AMPK and mTORCs have

critical functions in controlling the cell metabolism in a number

of types of cancer, shaping the anabolic and catabolic pathways

that regulate cell growth, proliferation and survival. AMPK serves

as a key energy sensor, activated in response to low cellular

energy levels, while the action of mTOR becomes evident under high

nutrient conditions (3-7).

AMPK deploys dual roles in controlling the

intracellular environment of tumor immunity, affecting both immune

and tumor cells. AMPK is the key factor between the immune cell

microenvironment and the metabolism energy of tumor cells (8). Recently, it has been shown that AMPK

exhibits anticancer immune activity by cooperating with dominant

components at the cancer microenvironment, affecting the roles of

T-lymphocytes, myeloid suppressor cells and macrophages (9). Furthermore, AMPK can inhibit the

production of chemokines and cytokines (10). Taken together, AMPK plays a master

role in the modulation of tumor microenvironment.

Moreover, the mTOR signaling pathway plays a

critical role in the regulation of the tumor microenvironment

(11). The mTOR cascade plays

regulatory roles in the growth, differentiation, survival and

function of adaptive and innate immune cells (12). It controls the phenotypic, the

functional, and direct reprogram in tumor-immune cells

microenvironment. In addition, mTOR stimulates the inflammatory

process and promotes the replenishment of the immune cell to tumor

environment, resulting in stimulating anticancer effects or

supporting tumor cell development, proliferation and metastasis

(13). Therefore, misregulated

mTOR pathways in tumors can modify the tumor microenvironment,

disrupting the cancer immune microenvironment.

Research has demonstrated critical associations

between the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway and ferroptosis in

carcinogenesis (14). Ferroptosis

is an iron dependent programmed cell death process that has gained

increasing attention from researchers for targeting cancer growth

(15). Ferroptosis is closely

associated with mTOR, and utilizing mTOR-related therapy has the

potential to stimulate the rate of ferroptosis in the targeting of

several types of cancer (16). It

has also been demonstrated that AMPK confines the stimulation of

ferroptosis and subsequently, the inhibition of AMPK therapy

restores the treatment and restores the responsiveness to

ferroptosis activators (17).

Moreover, it has been demonstrated that amentoflavone stimulates

ferroptosis by stimulating the ROS/AMPK/mTOR signaling axis to

reduce the uterine cell cancer viability and prorogation by

stimulating the ferroptosis and apoptosis (18). Thus, AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway is

the central player in ferroptosis process.

Furthermore, AMPK and mTOR have been recently shown

to be involved in mitochondrial dynamics in cancer progression

(19). AMPK plays a crucial role

in the regulation of mitochondrial activity and cytoskeleton

modification, with an increased AMPK activity in cells with a low

migratory ability; this induces the mitochondrial fission, leading

to reduced oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), low adenosine

triphosphate (ATP) biogenesis and the reduction of ameboid myosin

II-dependent cell migration (20).

Moreover, the abnormal expression of MTERF1 in colorectal cancer

cells modulates the p-AMPK/mTOR pathway of mitochondrial

dysfunction (21). Therefore, the

AMPK/mTOR axis can be a good way to treat different

mitochondrial-related diseases such as cancer and metabolic

syndromes.

The AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway has also recently

been shown to be involved metabolically in condensate formation.

Developments (condensates) are a mutual strategy for cells to

complete various functions, such as DNA repair, chromatin

association, transcriptional activity and signal transduction

(22). Recently, abnormal phase

separation and alteration have been stated to be associated with

cancer and other neurodegenerative diseases (23). AMPK activation occurs during

metabolic stress; this activation stimulates the formation of

condensate and stress particles that promote cancer cell survival

and progression under different nutrients deficiency (24). In addition, condensate development

organizes the necessary metabolic enzymes to stimulate the

metabolic switching in the tumor microenvironment (25). Moreover, a recent study

demonstrated that the formation of EMT supports carcinogenesis, and

metastasis is notably initiated and governed by phase separation

(condensate formation) (26).

These data highlight the critical role of the AMPK/mTOR pathway in

regulating condensate particle formation; these data may provide a

novel approach for cancer treatment by targeting these metabolic

vulnerabilities.

Disruptions in these signaling pathways may

inadvertently cause tumor progression, emphasizing the importance

of novel therapeutic interventions targeting this complex network.

Moreover, understanding the complex balance of the action between

AMPK and mTORCs can lead to the development of novel approaches to

combat cancer growth, while diminishing the threat of unintentional

consequences associated with modifying metabolic switches.

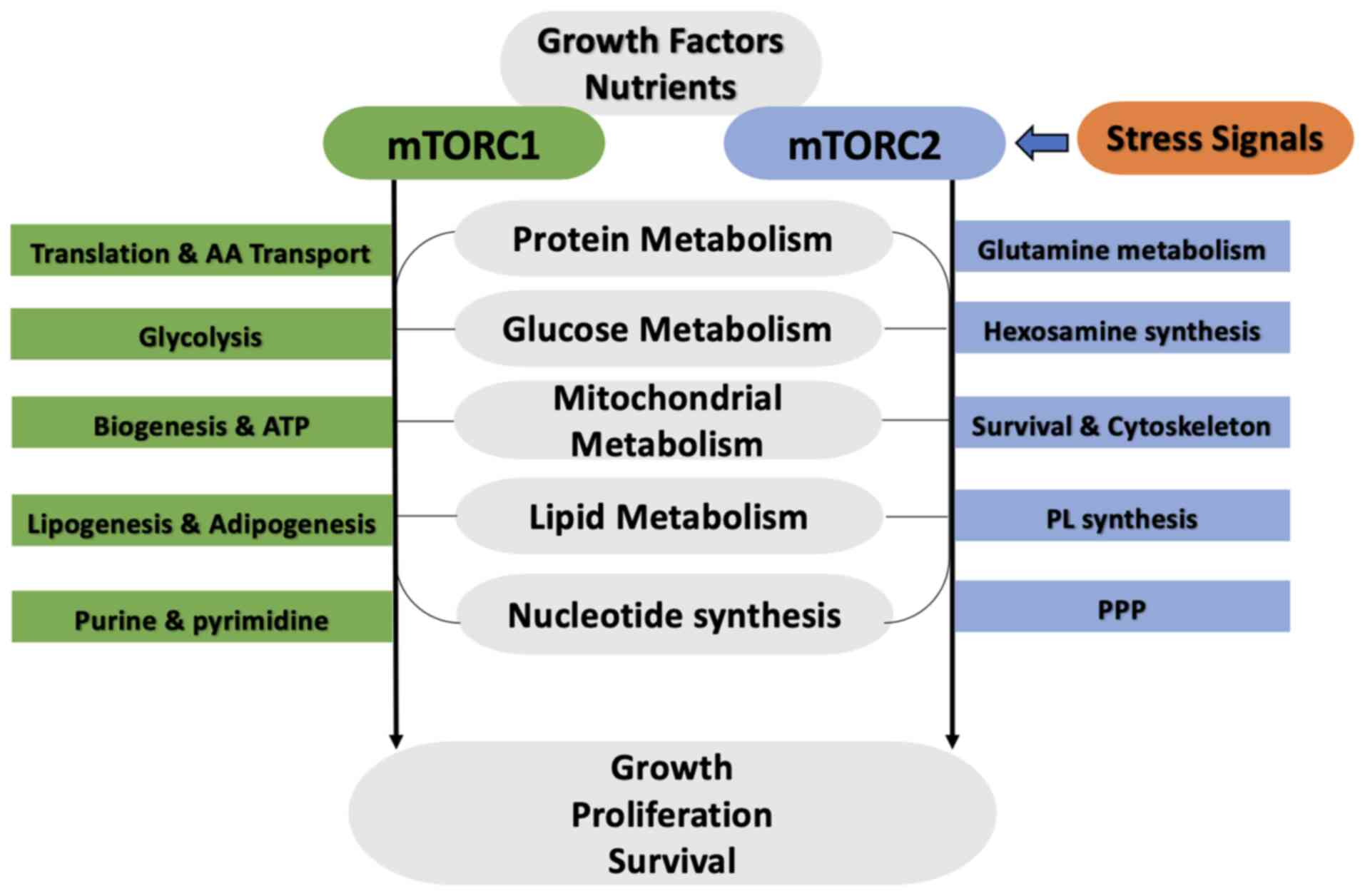

Both mTORCs function as central regulators of the

use of glucose in normal and cancer cells, markedly contributing to

metabolic rewiring, which describes different malignancies. mTOR1

and mTOR2 can regulate the expression of glycolytic enzymes,

glucose transporters and transcription machinery that stimulate the

expression of various genes related to glycolysis pathway effectors

(27).

Decades ago, Otto Warburg found that cancer cells

use aerobic glycolysis as fuel source to keep the building blocks

that are required for cell growth and propagation. This specific

characteristic of tumor cells is well-known as the Warburg effect,

whereas OXPHOS is the main energy source for the maintenance of the

development and proliferation of normal cells (27-30).

Warburg's discovery was recognized and confirmed in various human

tumors with radioactive glucose analogs using (fluorodeoxyglucose)

to examine glucose utilization in normal and tumor tissues

(30). Currently, the Warburg

effect is one of the cancer hallmarks, in addition to other

characteristics, such as immortality, resistance to cell death,

avoiding growth defeat, stimulating invasion, angiogenesis and

metastasis (28-30).

Additionally, a high mutation rate with genomic variability,

escaping the immune defense and tumor-increasing inflammation are

up-and-coming hallmarks that are related to carcinogenesis.

Modified glucose uptake over aerobic glycolysis is an ineffective

mode to generate energy, as it provides two ATPs per glucose

molecule. By contrast, OXPHOS provides 36 ATPs from glucose

oxidation via the Krebs cycle (30-33).

Previous studies have confirmed that the majority of tumor cells

shift the glucose metabolism from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis even

in the presence of O2. Tumor cells convey glucose

metabolic intermediates to biosynthetic macromolecule new building

blocks pathways. This activity sustains tumor development by

providing metabolic intermediates to refill cancer cells and

producing reducing molecules, such as nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) for different metabolic activities

(33-35).

In differentiated cells, glucose oxidation is an

oxygen-dependent process, either through OXPHOS (with

O2) or fermentation (without O2) (35-38).

In expanding cells, mainly tumor cells, pyruvate from the oxidation

of glucose is transformed into lactic acid through aerobic

glycolysis, also known as the Warburg effect, even in the presence

of oxygen. In addition, glucose oxidation provides the intermediate

substrates for the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) to generate

ribose-5-phosphate (R5P) required for nucleotide synthesis and

NADPH to sustain cellular redox homeostasis (39). Furthermore, glycolytic substrates

are essential for synthesis 3-phosphoglycerate, a precursor for the

serine synthesis cascade, providing the crucial molecules for the

biosynthesis of various (non-essential) amino acids. Moreover, the

transamination reaction converts pyruvate to alanine and citrate

transfers the mitochondria into the cytoplasmic matrix for the

biogenesis of fatty acids (FAs) (35,40-42).

This indicates that tumor cells efficiently use different glucose

metabolism to maintenance progression and survival.

mTORC1 stimulates glycolysis by promoting and

regulating two main transcription factors [hypoxia inducible factor

(HIF)1a and Myc] (Fig. 2). mTORC1

similarly stimulates the upregulation of glycolytic gene through

the transcriptional controller of Myc (43,44).

Myc is mutated in >50% of human cancers, and its increased

expression is frequently associated with enhanced glycolysis and

glutamine metabolism (45,46). mTORC1 stimulation of S6K and 4EBP1

is essential for Myc-stimulated carcinogenesis (47). Researchers have demonstrated that

genes are sensitive to rapamycin and are controlled by Myc

(48). The metabolic shift of

glucose metabolism is mainly orchestrated across the mTOR1

activation, which reacts to external growth signals such as

insulin, amino acids and glucose (49-52).

mTORC1 boosts the glycolysis pathway and enhances the transcription

and translation activities for crucial enzymes that participate in

glycolytic and lactic acid production, such as hexokinase II and

pyruvate kinase M2, that is produced in dividing and cancer cells.

In addition, the mTOR2 pathway stimulates the expression of glucose

transporter (GLUT)1 and phosphofructokinase (PFK) under the

transcription machinery of these factors, thereby accelerating the

glucose uptake in various types of cancer, such as colon,

pancreatic, hepatic, lung and breast cancers (53-56).

This step is essential for maintaining the excessive ATP levels

necessary for energy-intensive activities, such as cell development

and division. Furthermore, mTOR1 stimulates the expression level of

several glycolytic enzymes by enhancing the translation of HIF1a

(57). Evidence indicates that the

role of mTOR is to regulate the gene expression of the enzymes for

the glycolysis pathway and modulate the enzymatic activity through

phosphorylation, promoting the appropriate microenvironment for

cancer cell growth and development (58). Furthermore, the upregulation of

this enzyme by mTOR1 is regulated through the aforementioned

mechanism. In addition, the upregulated mTOR1 pathway due to

tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)2 mutation specifically stimulates

the one isoform of PFK in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (59). Moreover, the connection between the

mTOR cascade and the PI3K/AKT signaling cascades has been

demonstrated as the central axis for the glycolysis signaling

pathway. Activated AKT induces the activity of the glycolytic

signaling pathway under hypoxic environments and downregulates the

expression of large non-coding RNA, further enriching tumor cell

adaptation and development (60-62).

mTORC2 increases glycolysis that stimulates class

IIa histone deacetylase phosphorylation, thus inhibiting them,

promoting Fox O1 and O3 acetylation, resulting in the

downregulation of c-Myc in glioblastoma (63). A better understanding of the

function of the mTOR pathway in glycolysis and cancer cell

metabolism will open a new avenue for targeting this pathway

therapeutically, allowing the modification of glycolysis to impede

cancer growth. Targeting the mTOR pathway using an mTOR inhibitor

has shown promising results in clinical breast cancer models by

decreasing glycolytic activity and enhancing metabolic deprivation

in tumor cells (64).

mTOR plays a substantial role in the dependence of

cancer cell on glutamine breakdown, which is increasingly

recognized as a crucial factor in cancer biology and therapeutic

approaches. mTOR is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine

kinase that is in two different complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2; mTOR

plays regulatory roles in numerous biological processes, such as

cell glucose metabolism, growth, lysosome biogenesis, survival,

autophagy and migration, that are required for cell development

(Fig. 2). Therefore, its

equilibriums between the anabolic and catabolic activities

consistent to different bioenvironmental elements (65,66).

One of the crucial roles of mTOR is its role in the metabolism of

glutamine, which has been raised as a critical source of nitrogen

and energy for rapidly proliferating cancer cells. Tumor cells use

glutamine also as an energy source apart from the utilization of

glucose; glutamine is conditionally an essential amino acid, and it

is free in human blood. Therefore, its production may be decreased

under specific different pathophysiological situations and

metabolic conditions (67).

Glutamine synthetase (GS) accelerates the linking reaction between

glutamate and ammonia to procedure glutamine (68). Glutamine has functions in lipid and

protein synthesis, precisely in tumor cells and energy redox

homeostasis such s glucose. It is a precursor for glutamate citric

acid and carbon synthesis (69).

Moreover, glutamine is a nitrogen atom donor for purines,

pyrimidines, and asparagine. Notably, it is also a precursor of

(NAD) and is a source of glucosamine synthesis (67). In addition to the function of

glucose in stimulating tumor cell proliferation, tumor cells are

dependent and addicted to glutamine use to support different

anabolic signaling pathways for constant cell persistence (70).

The activity of mTOR is essential in this metabolic

flexibility, as it functions as a nutrient sensor, sensing the

activity of a number of amino acids, including glutamine, and

controlling subsequent signaling pathways accordingly. Research

reveals that metabolic glutamine triggers mTORC1 activity through

intermediates produced during its breakdown. For example, glutamate

is subsequently converted to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), a key

metabolite that stimulates mTORC1 via its interaction with prolyl

hydroxylases, which increases the GTP loading of Rag GTPases

responsible for mTORC1 activation; this controlling mechanism

elucidates how glutamine not only stores energy, but also performs

as an agonist for mTOR metabolic pathway, developing a pro-growth

microenvironment that boosts cancer cell growth and survival

(71).

The mTORC1 pathway stimulates glutamine metabolism

through the c-Myc transcription factor, which controls the

expression of genes required for glutaminolysis, such as

glutaminase 2 and other enzymes in c-Myc-stimulated T-cells

(72). A feedback cycle exists

between mTORC1 activation and glutamine metabolism through Myc

(73,74). In addition, mTORC1 stimulates

glutaminolysis by controlling the activity of cAMP-responsive

element binding 2 (CREB2) by enhancing its degradation (75). These results indicate that mTORC1

stimulates glutamine uptake via negative feedback mechanism of

CREB2, finally leading to GDH stimulation.

Additionally, the association between the mTOR

pathway and glutamine metabolism extends to controlling autophagy

and cellular stress reactions. Under a rich nutrient situation,

mTORC1 stimulates protein production, while hindering autophagy, a

safe process for degrading excessive or malfunctional proteins and

damaged cellular components. When cellular glutamine levels are

low, mTORC1 action is reduced, stimulating autophagy to reutilize

cellular components and maintain metabolic cellular homeostasis

(76).

Notably, the role of mTOR in glutamine use has a

number of clinical implications, as various studies have

investigated the targeting of this signaling pathway with mTOR

inhibitors as a novel therapeutic approach. For example, it has

been demonstrated that some cancers can adapt to mTOR inhibitors by

enhancing glutamine metabolism to promote cancer growth and resist

treatment. In addition, it has also been demonstrated that

glutamine deprivation plus mTOR inhibition can be more effective in

eradicating tumor growth and survival (72-76).

Cancers with highly upregulated mTOR activity are frequently

challenging to standard therapies, and reducing mTOR activity

significantly impairs cancer growth by breaking their metabolic

flexibility. Moreover, mTORC2 is rising as a critical player in

glutamine cellular metabolism as it controls the expression of Myc

(77). It has been shown that the

knockdown of Rictor reduces α-KG levels, which are expected to have

originated from glutaminolysis, indicating that mTORC2 can control

this process (78). Earlier

findings have demonstrated that the mTORC2/AKT axis may not affect

glutamine metabolism or consumption (79). A recent study suggested a

connection between stimulated mTORC2-facilitated AKT

phosphorylation and glutaminolysis through different mechanisms. In

addition, low levels of glutamine or its substrate activate mTORC2,

as revealed by the phosphorylation of AKT. Moreover, low levels of

glutamine reduce the activity of mTORC1, whereas mTORC2 activity

increases (80). Inhibiting the

activity of mTORCs stimulates glutaminolysis, signifying an

additional multifaceted feedback loop, possibly to confirm TCA

replenishing as mTOR signaling declines.

mTORCs play a crucial role in controlling glutamine

metabolism in cancer cells. By serving as a sensor of metabolic

nutrient accessibility, mTORCs not only affect cellular development

and propagation, but are also tortuously associated with the

metabolic needs of tumor cells to promote a favorable

microenvironment for tumor progression. Further studies are

required to elucidate the precise mechanisms behind the regulatory

role of mTORCs for glutamine use. It is crucial to develop

effective therapies that disturb the metabolic routes that tumor

cells manipulate to accomplish their rapacious energy

requirements.

mTOR has a central function in controlling protein

metabolism in cancer cells, functioning as a central hub that

combines numerous signaling cascades, the availability of

nutrients, and energy situations to regulate cellular growth,

propagation and metabolic variation. Understanding the importance

of mTOR in protein biosynthesis and metabolism is necessary for

illustrating how malignant cells achieve their elevated need for

proteins, crucial constituents for cell structure, role, and

signaling during cancer propagation. Protein biosynthesis is

correctly regulated and requires essential and nonessential amino

acids. Cancer and non-cancer cells obtain these molecules through

growth factor signaling by providing surface transporters, which

allow them to direct these molecules from external sources and

maintain mTOR-signaling networks (81,82).

mTORC1 is mainly involved in stimulating protein

biosynthesis across its effector molecules (Fig. 2). mTORC1 phosphorylates the two

main effecters for protein translation, 4E-BP1- and S6K1. S6K1

phosphorylates a number of factors that are directly or indirectly

involved in protein biosynthesis, such as PDCD4, SKAR eIF4B and

eIF3 (83,84). Notably, mTORC1 is stimulated by

amino acids to promotes protein biosynthesis through its active

functions in translation and ribosome synthesis, phosphorylating

S6K and the initiation factor 4E-BP for eukaryotic translation

(85-87).

This phosphorylation cascade enhances the translation of mRNAs

involved in ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis (88-91).

A crucial aspect of the role of mTORC1 is that it enhances

ribosomal protein synthesis, which is necessary for cellular growth

and proliferation. A previous study revealed that mTORC1 notably

affects ribosome biosynthesis in lung cancer cells, emphasizing its

function in supporting tumor cell growth through enhanced protein

biogenesis (92). With the

increase in ribosome biosynthesis, mTORC1 accelerates the total

protein biosynthesis rate, thus driving energetic tumor cell

metabolism towards progression and malignant behavior. Furthermore,

the interplay between mTOR roles and oncogenic cascade is crucial

for understanding the function of mTOR in cancer development

(93).

mTORC1 activation is related to the oncogenic action

of Myc. Myc enhances the expression of genes involved in protein

biogenesis, and its activity is mainly mTOR-dependent,

demonstrating that mTOR inhibitor drugs may be an efficient

therapeutic approach in Myc-dependent tumors (94,95).

In contrast to the above, the dysregulation of mTOR signaling

triggers the abnormal metabolism of protein, causative of tumor

cell persistence and drug challenge, as demonstrated in research

investigating the effects of mTOR inhibitors in several tumor

models, including renal adenocarcinoma (96). Recent developments in cancer

research biology have shown that the function of mTOR is not merely

the regulation of protein biogenesis. Still, it extends to

controlling the balance of the anabolic and catabolic pathways,

such as autophagy. Under high nutrient availability, mTORC1

stimulates protein production while hindering autophagy, a safe

process for degrading excessive or malfunctioning proteins and

damaged cellular components. Genomic data showed that treatment

with rapamycin was related to a decline in the transporters of

neutral amino acids (97).

Suppressing either Raptor or Rictor reduces, whereas their mutual

knockdown blocks transport action for alanine and leucine amino

acids (98). In addition, mTORC1

controls the transfer of the aforementioned transporters through

the inhibition of Nedd4-2 ubiquitin ligase activity, which

stimulates ubiquitination and diminished expression levels of the

mentioned transporters (99).

Moreover, the inhibition of mTOR activity with Torin 1 diminishes

the transcription of the gene for amino acid enzymes and

transporters essential for amino acid and protein metabolism

(100).

Furthermore, mTORC2 is directly engaged in the

metabolism and transport of amino acids through Ser26

phosphorylation of cysteine-glutamate antiporter, which impedes the

glutamate output and cysteine input (101). Therefore, the aforementioned data

support the critical roles of mTORC1 and mTORC2 in modulating

protein metabolism and synthesis by regulating the transporter

activity and/or level of amino acids. mTOR regulates asparagine

synthetase (ASNS) expression levels (102,103). mTORC1 controls the ASNS

expression level (104). In lung

adenocarcinoma, the elevated level of KRAS promotes ASNS activity

that occurs through AKT and Nrf2, facilitating the stimulation of

ATF4. Mutually AKT inhibition with the reduction of cellular

asparagine inhibits cancer growth (105). Rapamycin stimulates the gene

machinery of argininosuccinate synthetase-1 (ASS1), the crucial

enzyme for arginine synthesis (98). Arginine-deficient cancers, for

example hepatocellular carcinoma and melanoma, are resistant to

arginine deiminase therapy that reduces the cellular arginine and

increases ASS. These tumors become primarily sensitive to dual

inhibitors of PI3K and AKT (106); thus, mTORC2 is involved in

arginine biosynthesis. De novo serine and glycine synthesis

are also increased by mTORC1 via ATF4, the transcription factor

(107). Ultimately, the mTORCs,

through an indirect pathway, may be involved in protein and amino

acid synthesis via their activity in other metabolic signaling

cascades.

This paradox is critical for appreciating the

metabolic modification of tumor cells, as a high mTOR activity can

increase survival by inhibiting the autophagy pathway, permitting

an accumulation of the necessary proteins for fast cell progression

and proliferation (108).

Therefore, targeting mTORC1 and mTORC2 therapeutically interrupts

this balance, stimulating autophagy to fight carcinogenesis

efficiently.

The importance of the mTOR pathway in controlling FA

metabolism is a primary mechanism enabling tumor growth and

persistence Fig. 2. Cancer cells

create fatty acids for lipid membrane, lipid alterations, and

signaling cascade action (103-109).

FA synthesis requires acetyl-CoA and cytosolic form (NADPH) of the

reducing agents. Dynamic FA synthesis relies on the incorporation

of additional carbon metabolic signaling pathways and

oxidation-reduction reactions. Glucose is the main precursor of

acetyl-CoA for FA synthesis in the majority of culture media

(110-112).

In hypoxic and mitochondrial malfunction, acetate

glutamine and leucine breakdown are another resource for acetyl-CoA

(113-117).

Additionally, study revealed that FAs synthesis is controlled by

the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1)

transcription factor (118).

SREBP-1 regulates the enzymes needed to transfer the acetyl-CoA

into fatty acid and the PPP enzymes needed to convert acetate and

glutamine to acetyl-CoA. Thus, SREBP-1 controls genes that help or

catalyze FA synthesis (119). In

tumor cells with an abnormal rate of FA synthesis, the mTOR

pathway, across its subsequent target S6 Kinase (S6K), stimulates

and promotes the transcription activity of both SREBP-1 and SREBP

2. The ultimate proteins regulate the transcription activity of

different genes that relate to sterol biosynthesis (120). Therefore, SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 are

essential for mTOR to promote and stimulate cell growth and

proliferation. Tumor and normal cells take FAs and lipids from the

extracellular sources to use them to maintain the synthesis of cell

membranes. In presence of growth factors, PI3K increases FAs and

lipid use and downregulates oxidation of lipid through

(β-oxidation) within the mitochondrial matrix to continue cell

growth and proliferation (121).

In tumor cells and under hypoxic conditions, the

mTOR pathway enhances endoplasmic reticulum action to sustain

protein biosynthesis via an extracellular resource of unsaturated

FAs. Moreover, ATP citrate lyase, the final enzyme that alters

acetate to acetyl-CoA, inhibits tumor cell growth and propagation

(122). Thus, targeting FA

synthesis and transport can reduce tumor cell growth and

proliferation. mTOR is a critical regulator of various metabolic

pathways in cancer cells, including fatty acid metabolism, which is

essential for understanding tumor biology and therapeutic

interventions. mTOR modulates metabolic processes by integrating

nutrient signals, growth factors, and stressors. Given that cancer

cells exhibit altered metabolism, often adapting to exploit various

substrates, the importance of mTOR in controlling the metabolism of

fatty acids stands out as a primary mechanism enabling tumor growth

and persistence.

Cancer cells have a reprogrammed metabolism to meet

the increased requirements for fuel and building blocks required

for fast proliferation. In this context, FAs function as primary

energy resources and synthesize different biomolecules, including

cell membranes and signaling biomolecules. mTOR plays a central

role in FA synthesis by controlling the expression and activity of

lipogenic enzymes. It has been demonstrated that mTORC1 directly

activates SREBP1, causing an increase in the expression of FA

synthase and subsequent FA synthesis (123). Consequently, the activating

mTORC1 pathway enhances lipogenesis, which is particularly relevant

in cancer types characterized by increased demand for lipids.

Moreover, PI3K/AKT/mTOR oncogenic cascade pathways

are frequently dysregulated in several types of cancer, further

enhancing lipogenic activities. For example, in thyroid gland

cancer, pyruvate carboxylase, an enzyme key for transferring

pyruvate to oxaloacetate, stimulates aggressive cancer action

partially through increased lipogenesis, which is controlled

through mTORC2 signaling (124).

This reveals that mTOR signaling not only accelerates the uptake of

FA, but also vigorously provides for their biosynthesis, providing

cancer cells with an adaptable energy source to acclimate under

unusual physiological stresses. Recent research suggests a growing

interest in how specific FAs influence mTOR signaling and metabolic

reprogramming in cancer cells through the high expression of

several enzymes that are essential for FAs metabolism, such as

carnitine transporter, CPT isoforms and CD36 in several types of

cancer, such as gastric and prostate cancer, and triple-negative

breast cancer (TNBC) (125). Some

researchers have investigated the function of omega-3 FAs that have

been shown to reduce mTORC1 signaling activity, theoretically

leading to diminished FA synthesis and boosting apoptosis in tumor

cells (126). This provides

prospective opportunities for a therapeutic approach, as combining

mTOR inhibitors with dietary FA variation could provide a

dual-target system to hinder tumor cell growth and stimulate

metabolic susceptibility.

mTORCs are key regulators of cell metabolism,

specifically from the perspective of nucleotide biosynthesis, which

is necessary for tumor cell development and proliferation (Fig. 2). Nucleotide biosynthesis (purine

and pyrimidine) is critical in rapidly-dividing cells,

particularly, in cancer cells with sufficient precursors for RNA

and DNA synthesis. The nucleotide biosynthesis is a complex

process, demanding enormous support from additional metabolic

signaling pathways in a specific manner. R5P is the intermediate

product of the PPP that provides the main sources for

phosphoribosylamine and glutamine. R5P also functions as an amide

precursor for nucleotide biosynthesis (127,128). In addition, one carbon cascade is

an additional resource for different non-methyl-group and

non-essential amino acids that are involved in pyrimidine purine

biosynthesis. Moreover, the TCA cycle supplies the oxaloacetate

that is transaminated to aspartate, and its vital element that is

necessary for nucleotides base synthesis (129-131).

Therefore, the inhibition of nucleotide biosynthesis by

pharmacological therapies may be an effective approach for

eradicating specific tumors, such as antifolates and nucleosides

that have been used in the treatment of cancer for a number of

years (132).

The activation of the mTORC1 pathway has been shown

to stimulate pyrimidine biosynthesis (132). Ribosomal K6S stimulates the

phosphorylation of carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2, aspartate

transcarbamylase, and dihydroorotase (CAD), a specific enzyme that

stimulates the first reaction of pyrimidine synthesis (133,134). mTORC1 actively stimulates

nucleotide breakdown by controlling the upregulation of central

enzymes in de novo nucleotide biosynthesis. Research has revealed

that mTORC1 stimulation boosts the biosynthesis of phosphoribosyl

pyrophosphate amidotransferase, a key enzyme in the purine

biosynthesis pathway. This control enhances the purine nucleotide

level that supports tumor cell growth and progression (135).

Moreover, mTORC1 incorporates signals from different

nutrient availability, mainly amino acids, to certify that

nucleotide synthesis is associated with the metabolic requests of

rapidly growing cancers. In addition to supporting nucleotide

biosynthesis, the mTORC1 pathway is highly linked to controlling

metabolic cascades that produce R5P, a key factor for the

biosynthesis of nucleotides. The PPP produces R5P from

glucose-6-phosphate, emphasizing the interconnection between the

glycolytic pathway, mTOR signaling, and metabolism of nucleotides

(136-138).

When glucose freely exists, mTORC1 triggers cellular propagation by

increasing glycolysis and nucleotide biosynthesis signaling

pathways, assisting tumor cells to proliferate quickly.

Furthermore, the communication between mTORC2 and

oncogenic cascades, such as the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, further

highlights the importance of mTORC2 in nucleotide synthesis and

tumorigenesis. For example, PI3K/AKT pathway activation triggers

mTORC2, stimulating fat and nucleotide biosynthesis that is

critical for cancer cell growth. mTORC2 signaling is often

dysregulated in breast cancer; targeting this pathway can impede

nucleotide synthesis, impairing cancer growth (139-143).

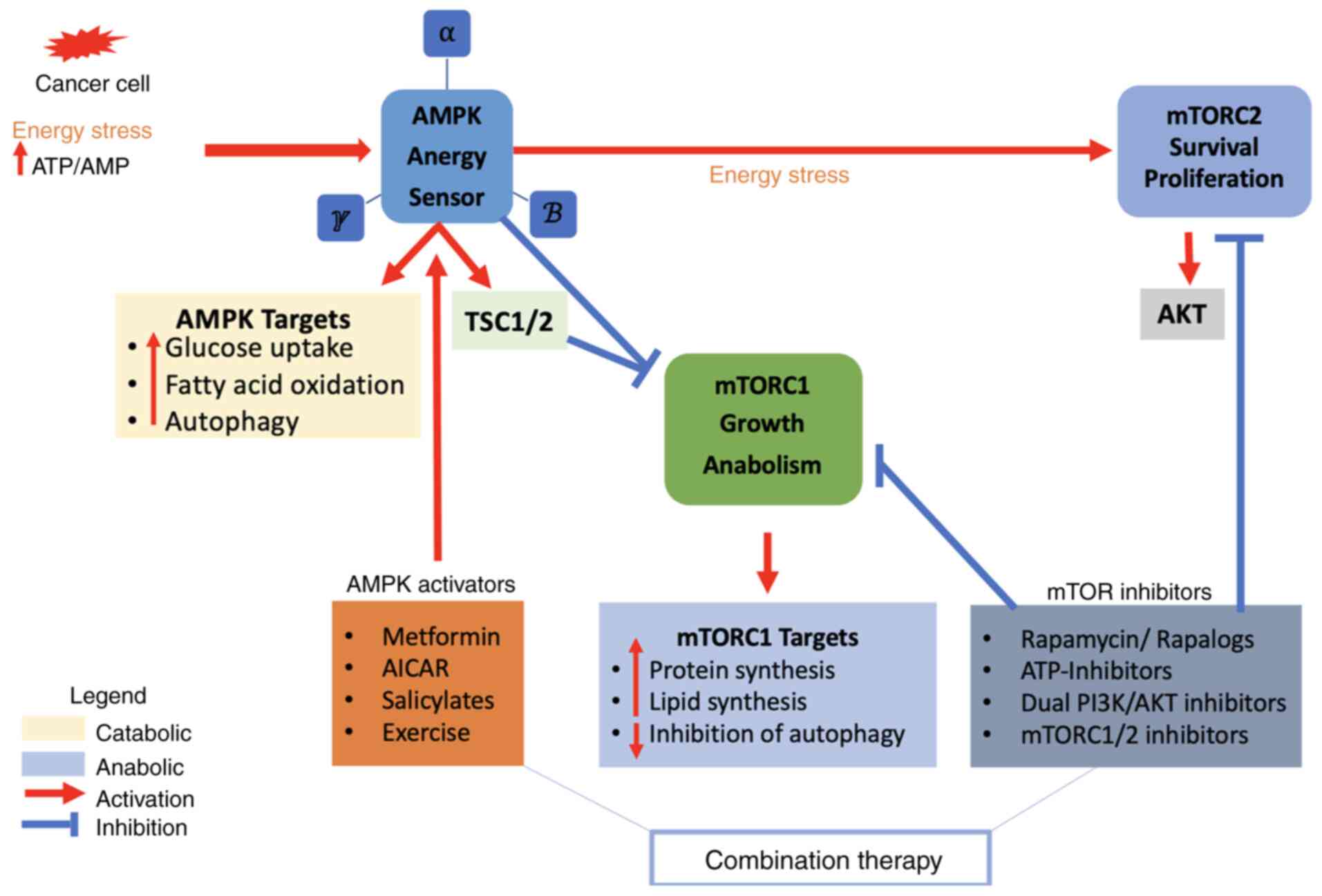

The mTOR complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, are pivotal

regulators of cancer cell metabolism by integrating nutrient

availability with signals that drive cell growth and proliferation

(Fig. 3). AMPK is an intracellular

sensor for energy equilibrium, which is presented in each

eukaryotic cell. AMPK consists of three subunits; (α) is the

enzymatic subunit and (β and γ) are the controlling subunits.

Different isoforms have been encoded by certain genes for each

submit in humans (144). AMP/ATP

and ADP/ATP ratios stimulate AMPK during severe energy stresses.

The activation of AMPK restores energy redox hemostasis by turning

on the catabolic cascade and turning off the anabolic cascades to

increase ATP production and maintain the energy equilibrium

(145,146). Moreover, AMPK stimulates glucose

consumption through the oxidation process in low proliferative

cells rather than rapid glucose utilization and glycolysis that are

employed in high proliferative cells (147,148). In yeast, the AMPK analog is

essential to shift the metabolism of yeast from fermentation

(glycolysis) to OXPHOS metabolism under severe starvation

situations. This rewired metabolism is similar to the reversal of

aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) that occurs in a number of

rapidly-growing cells, such as cancer cells (128). Salicylate and metformin are the

pharmacological activators of AMPK (149,150). They activate AMPK through

threonine residue (Thr172) phosphorylation and AMP binding

(151-153).

The actions of AMPK occur through three different mechanisms: i)

The enhanced phosphorylation of Thr 172 via LKB1; LKB1 is a tumor

suppressor, and it is the main upstream target of AMPK; ii) reduced

Thr172 dephosphorylation by a phosphatase; and iii) activated

allosteric stimulation. All AMPK activations occur due to AMP

binding to itself and not due to the upstream kinase outcome or

phosphatase (152-154).

Together, the complex interaction between mTORCs and AMPK signaling

cascades signifies a crucial metabolic step that guides cells to

anabolic processes that stimulate cancer development or turn to

catabolic process pathways that may defeat carcinogenesis.

AMPK redeems the energy balance following its

activation via energy stress by activating the catabolic signaling

cascade to produce sufficient ATP and by reducing the anabolic

cascades that use ATP (154,155). The loss of a single allele of

AMPK-α increases the development of B-cell lymphoma in mice with

c-Myc transgenic expression in B-cells, whereas the loss of both

alleles prompts a severe outcome (156). Therefore, this reveals that AMPK

may serve as a tumor suppressor, and any mutation in the genes of

AMPK subunits is uncommon in human tumors. Consequently, diminished

AMPK actions may be necessary for cancer cell survival and

malignancy by constraining the specific effects of AMPK on cell

development and propagation (157). The activation of AMPK is a

suitable approach to decrease tumor cell metabolism by hindering

the anabolic cascades and stimulating the catabolic cascades.

Histological slides from a human breast tumor study indicated that

the phosphorylation ratio of AMPK-α enzymatic subunits was less

than that of adjacent normal tissue (158). Another study revealed that the

phosphorylation of AMPK-α is a common occurrence in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma (159).

Additionally, another study demonstrated that AMPK is a negative

switch of the Warburg effect in cell and animal models (160). Several mechanisms have been

suggested to elucidate the reduction of AMPK activity. For example,

the genetic damage of LKB1 is relatively common in cervical and

non-small cell lung tumors but not in other tumors (161-163).

The activation of insulin/IGF1 controls the protein kinase AKT/PKB

is additional machinery for downregulation of AMPK, gain function

genes mutations of AKT and loss-of-function mutations of PTEN

(tumor suppressor) that happen in various tumors (164-166).

Collectively, the regular arrangement of AMPK inactivation across

various tumor types through several biomolecular mechanisms such as

downregulation of LKB1, loss of PTEN and Akt/PKB upregulation,

highlights the basic roles of AMPK as an energy and metabolic

master, which represents a hopeful therapeutic approach for

correcting the unusual energy status that supports cancer cell

persistence and propagation.

In addition, AMPK has an essential pro-survival

function in hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and AML through various mechanisms. A key

feature of AMPK is its role in buffering ROS, which are frequently

raised in tumor cells due to high metabolic requirements to support

tumorigenesis characters. The activation of AMPK enhances the

antioxidant ability by stimulating the main enzymes for antioxidant

activity, such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione (GSH;

specifically, by modifications of the regulatory metabolism of GSH

and regeneration pathways of NADPH), thus reducing oxidative stress

and supporting cell survival (167,168). Additionally, in the cancer

microenvironment, AMPK stimulates metabolic modifications, such as

increasing the oxidation of FA and downregulating the mTOR cascade

by phosphorylating acetyl-CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase,

allowing tumor cells to generate a sufficient amount of ATP under

different unfavorable and stressful conditions (169). Moreover, AMPK stimulates cell

cycle progression in hepatocellular carcinoma by modifying the

essential enzymes that are necessary for cell-cycle checkpoints

system, mainly the transition of G1/S (170). Under different stress conditions,

AMPK stimulates the phosphorylation of the p53-p21 axis, and

PERK-eIF2α in hepatocellular carcinoma, PDAC and AML respectively,

thus promoting cell cycle arrests, preventing DNA damage and

promoting cell survival (170-172).

PDAC, hepatocellular carcinoma and AML cells utilize the activation

of AMPK to support cancer progression under severe metabolic stress

by stimulating the autophagy regulators, such as beclin 1(BECN1),

unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1(ULK1) and transcription

factor EB (TFEB), promoting the degradation of protein aggregates

and damaged microgranules that would then stimulate the apoptotic

pathway (173). Recently, a

previous study have revealed that the activation of AMPK in AML

cells induces the downregulation of mTOR and increases autophagy,

generating a metabolically challenging phenotype that leads to drug

resistance (172). AMPK also

controls mitochondrial dynamics and biogenesis, confirming that

leukemic cells preserve adequate bioenergetic ability for survival

and cancer progression (174).

Taken together, these mechanisms emphasize the roles of AMPK in

regulating tumor cell survival, proposing its prospective approach

as a therapeutic strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma, PDAC and

AML.

Furthermore, the roles of AMPK depend on the

mechanistic foundation for this functional shift that present

inside cellular microenvironment such as nutrients levels and

hypoxia (175). Through the early

steps of cancer transformation, when cells preserve sufficient

nutrients and oxygen, AMPK stimulation functions as an energy check

that inhibits uncontrolled propagation by preventing main anabolic

cascade, such as FA biosynthesis, protein transformation and the

biosynthesis of nucleotides. The oppressive function of AMPK is

facilitated across the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase,

leading to reduced FA biosynthesis, and mTORC1 inhibition, which

diminishes protein biosynthesis and cell progression (176). Moreover, AMPK stimulates

mitochondrial genesis and autophagy processes that typically helps

the cellular microenvironment, but can ironically help established

cancers facing sever nutrient stress (177). Therefore, the shifting from

cancer suppressor to cancer promoter occurs when tumor cells face

metabolic restrictions through the cellular environment, where the

pro-survival roles of AMPK become beneficial for cancer growth and

development.

In breast cancer, AMPK displays perhaps the most

well-known dual roles, with its function determined mainly by tumor

stage, phenotype and microenvironmental situations (178). In hormone receptor-positive

breast cancers, AMPK stimulation is associated with improved

patient outcomes and minimized tumorigenesis (179). The tumor suppressive properties

are facilitated through the ability of AMPK to inhibit the

mevalonate cascade, decreasing cholesterol biosynthesis that is

critical for ER-receptor stimulation, and through the direct

suppression of FAS, constraining cell membrane biogenesis required

for rapid cell proliferation and division (180). Metformin, as indirect activator

of AMPK, exhibits significant anti-tumor roles in this situation by

stimulating metabolic stress and increasing insulin sensitivity

(181).

Conversely, in TNBC, AMPK mainly has an oncogenic

function and promotes metastasis. Under sever low O2

conditions, commonly observed in severe aggressive breast cancers,

AMPK enables metabolic switching to glycolysis and supports

autophagy-mediated persistence. This is mainly evident in

drug-resistant TNBC cells, where the activation of AMPK assists

survival during nutrients stress induced by cytotoxic compounds

(182). The protein biosynthesis

promotes cancer cell metastasis through controlling the dynamics of

cytoskeletal and stimulates blood vessels growth via HIF-1α

maintenance (183). Moreover, in

HER2+ breast cancers treated with trastuzumab,

AMPK-induced autophagy provides a resistance mechanism by reusing

cellular element to sustain energy equilibrium during targeted

drug-promoted stress (184).

In addition, lung adenocarcinoma presents a special

model for acknowledging the dual roles of AMPK due to the high

mutation rate pf LKB1, the main upstream signaling kinase that

controls the activation of AMPK (185). In the presence of wild-type LKB1,

AMPK sustains its tumor suppressive roles across traditional

mechanisms, such as the activation of TSC2 and the final inhibition

of mTORC1(186). Lung cancer

reacts positively to severe metabolic stress and exhibits a

response to AMPK activators, such as metformin and AICAR (187). The tumor inhibition features are

highlighted through the inhibition of glycolysis flux, increased

oxidative metabolism, and sustained cell cycle checkpoints that

stimulate apoptosis in response to oncogenic burden and stress

(188). Nevertheless, ~30% of

non-small lung cancer (NSLCS) cases harbor LKB1 mutations,

primarily shifting the functions of AMPK and removing its tumor

suppressive ability. In these cancers, different signaling cascades

compensate for the damage of AMPK-facilitated metabolic

controlling, leading to increase in addiction on glutamine and

glucose metabolism (189).

Paradoxically, while AMPK is activated in LKB1-mutant lung

adenocarcinoma, it can stimulate tumor propagation by accelerating

metabolic modification to nutrient restriction and oxidative stress

(190). This is mainly

significant in KRAS-dependent lung adenocarcinoma, where AMPK

supports maintain redox balance during oncogene-mediated metabolic

stress (191). Moreover, hypoxic

areas within lung cancers manipulate AMPK to stimulate VEGF

upregulation and increase angiogenesis, promoting cancer

vascularization and progression (192).

Moreover, AMPK displays a dual role in colorectal

cancer progression through its complex connections with different

inflammatory and metabolic signaling pathways (193). In the initial stages of

colorectal cancer, mainly in the stage of inflammatory intestine

disease and abnormal polyposis, AMPK plays a protective role by

inhibiting the chronic inflammatory reaction inside bowel and

decreasing oxidative damage by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway

activity, thus decreasing assembly of pro-inflammatory elements

such as cytokines that trigger cancer initiation and development

(194). AMPK also inhibits the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway in APC-mutant colorectal tumors, reducing one

of the main drivers of colorectal cancer growth (195). As colorectal cancer proceeds to

more advanced phases, the function of AMPK changes towards cancer

promotion, specifically in the mediating of hepatic metastases

where metabolic needs are enhanced. In the advanced stages of

colorectal cancer, cells use AMPK-drive metabolic reprograming to

modify to the liver microenvironment that differs drastically from

the colonic tissue in terms of metabolic availability and nutrients

requirements (196). Hypoxic

areas within colorectal tumors employ AMPK to sustain glycolysis

bioproducts and stimulate autophagy-promote survival during periods

of hypoxic angiogenesis. Additionally, AMPK accelerates resistance

to regular drugs such as 5-fluorouracil by increasing nucleotide

salvage cascades and supporting cellular energy equilibrium through

treatment-mediated metabolic stress (197).

Additionally, hepatocellular carcinoma provides a

convincing model of how AMPK functions under different metabolic

stress conditions. In the pre-carcinogenesis stage of fatty liver

and steatohepatitis, AMPK functions as an essential tumor

suppressor by inhibiting fatty liver accumulation and decreasing

oxidative damage. AMPK inhibits SREBP-1C to trigger lipogenesis and

β-oxidation, thus diminishing the inflammatory environment that

prompts the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma (198). This protective role is mainly

evident in patients with diabetes mellitus, when AMPK is activated

through metformin and provides hepatoprotective benefits,

decreasing the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma

(199). Once hepatocellular

carcinoma develops, particularly in conditions of chronic hepatic

diseases and cirrhosis, AMPK shifts to a tumor-accelerator role. In

the microenvironment with severe metabolic deprivation and hypoxia,

the metabolic modifications of AMPK become beneficial for

carcinogenesis (200). In

hepatocellular carcinoma, AMPK reprograms glutamine metabolism as

the main energy source when glucose sources become limited,

stimulating autophagy-enhanced persistence during sorafenib

treatment (201). AMPK also

accelerates modification to the unique metabolic difficulties of

the liver microenvironment, where competition for metabolic

elements with adjacent hepatocytes and immune cells generates

selective pressure for metabolically adaptable cancer cells

(202,203).

The mechanistic interaction between the redox

metabolic roles of AMPK and hormonal signaling pathways to regulate

cancer behavior has also been observed in prostate cancer (PC). In

hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, AMPK displays well-defined tumor

suppressive roles through its connections with the AR signaling

pathway in androgen-sensitive PC (204). The activation of AMPK decreases

AR transcription directly and indirectly through

phosphorylation-trigger inhibition and via the suppression of

mTORC1 activity, respectively, which is necessary for AR protein

biosynthesis (205). AMPK also

reduces lipid biosynthesis cascade, which are necessary for

building blocks to support high PC proliferation and arrest the

cell cycle through p21 stimulation (206). These results provide good

outcomes for patients with identified PC who sustain usual

metabolic function. During the transition to castration resistance,

PC marks an important shift in the function of AMPK towards a tumor

developer (207). AMPK become an

essential player in metabolic reprograming and tumor survival in

the AR-depleted milieu formed by AR deprivation chemotherapy. In

the androgen-depleted environment created by androgen deprivation

therapy, AMPK becomes essential for metabolic adaptation and

survival. PC cells manipulate AMPK to stimulate AR-VS splicing

(alternative splicing of AR variants) that maintain main activity

in the absence of AR, accelerating hormone-independent progression

(208). Under the low

O2 conditions normally established in advanced-stage PC,

AMPK stimulates metabolic switching from OXPHOS to glycolysis and

increases autophagy-facilitated survival in docetaxel resistance PC

patients. Survival function is particularly evident in docetaxel

resistant (207,208).

A number of anabolic signaling pathways are

activated by the mTORC1 pathway, which, in the end, inhibits AMPK

activation (209). This

inhibition occurs through various mechanisms, such as TSCs

phosphorylation or the phosphorylation of Raptor, a regulatory part

of mTORC1 (210,211). Thus, AMPK activation inhibits the

biosynthesis of lipids, nucleotide, and proteins, reducing cell

growth and proliferation. Moreover, it arrests the cell cycle at

the G0/G1 phase by stimulating p53 phosphorylation, thus preventing

DNA biosynthesis (212-214).

Conversely, it has been demonstrated that AMPK can directly

stimulate mTORC2 by phosphorylating its parts, supporting cell

growth and survival during severe energetic stress (215,216). Therefore, both roles of the AMPK

regulator with the inhibition of mTORC1 stimulate anabolic

pathways; the potential stimulation of mTORC2 highlights a

multifaceted association that should be cautiously modified to

accomplish efficient tumor therapy.

In various types of malignancies, such as

colorectal, PDAC and glioblastoma, the association between mTORC1

and AMPK is necessary for cell progression under metabolic stress

environments. Data from hepatocellular carcinoma study have

established that the deprivation of amino acids and the later

re-addition of leucine lead to a specific alteration in mTORC1

activity, with the consequent stimulation of AMPK during glutamine

deficiency, promoting the inhibition of the mTORC1 cascade

(217). This suggests that the

glutamine level and nitrogen source, which modify the metabolic

environment, can significantly regulate mTORC1 stimulation across

the AMPK signaling pathway, suggesting a feasible therapeutic area

for tumor glutamine-dependent metabolism. Furthermore, data from

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia studies have revealed that AMPK

stimulation is crucial for glycolytic intermediates

ratio/mitochondrial function and metabolism, consequently

accelerating the downregulation of mTORC1 in situations of severe

metabolic stress (218,219). Additionally, emerging data from

an AML study have revealed a complex association between the role

of AMPK and mTORC1; these appear to function through two parallel

essential cascades that connect the activation of mTORC1 and

glucose metabolism to control the complete cellular homeostasis

(220). The co-activation of AMPK

and mTORC1 within specific leukemia cells demonstrates the

paradoxical landscape of these metabolic pathways, with AMPK

fostering OXPHOS, whereas mTORC1 mainly triggers glycolysis. This

indicates that controlling AMPK activity could produce distinctive

effects in metabolic reprogramming, conditional on the specific

cancer environment (221,222). Furthermore, the link between

mTORC2 and AMPK is progressively acknowledged as a critical factor

in regulating the metabolism of several cancers and treatment

responses. While mTORC1 has been significantly studied for its

function in growth signaling, mTORC2 is more strictly connected

with cell survival and metabolism through switching, as for

example, metabolic deprivation and the withdrawal of growth

factors. Data from recent project on colorectal cancer have

demonstrated that AMPK stimulation can boost mTORC2 signaling,

stimulating cell growth and survival under different nutrient

deprivations (223). This

association suggests a complex response mechanism. At the same

time, AMPK usually serves to impede mTORC1 activities in a low

energy environment. Still, it can also maintain mTORC2, thus

permitting the stimulation of pro-survival metabolic pathways

throughout AKT phosphorylation, finally modifying cancer

aggressiveness (224). Study on

lung cancer that are resistant to EGFR inhibitor therapy have

demonstrated that mTORC2 is necessary for mediating resistance

against the aforementioned inhibitors. Upregulated mTORC2 helps to

sustain lung cancer cell propagation despite EGFR inhibitors

(225). AMPK shapes cellular

reactions in such models, theoretically stimulating a shift towards

an aerobic glycolysis pathway to meet energy demands under

therapy-induced stress. The role of AMPK not only affects mTORC2,

but also overlaps with additional oncogenic cascades, encouraging

metabolic switches that maintain cell growth and proliferation

(226). These data mutually

demonstrated that the AMPK/mTORC1 signaling pathway functions as a

in adynamic and metabolic control, where the stability between

these two contrasting cascades regulate tumor cell outcome and

metabolic elasticity, emphasizing the essential for accuracy

therapeutic methods that need for cancer-specific metabolic

addictions and microenvironmental restrictions.

Moreover, from the perspective of pancreatic cancer,

the mTORC2 pathway has been connected to modifying metabolic

flexibility and response to different therapies, such as PARP

inhibitors. A study in this area has confirmed that mTORC2

signaling controls DNA repair by regulating BRCA1(227). The precise interaction between

AMPK and BRCA1-dependent processes is still being disclosed.

However, it highlights the possibility of the AMPK-regulated

modulation of mTORC2 increasing therapeutic sensitivity, possibly

providing dual therapies that control these signaling pathways.

Furthermore, the notion that mTORC2 provides glycolytic switching

in response to elevated glutamine levels underlines the necessity

to appreciate the dynamic interaction between metabolic

availability and mTORC2 action through AMPK (228). In a study on glioblastoma, the

AMPK/mTORC2 axis displayed its functions in stimulating cell

survival during nutrient deprivation, which is critical as these

tumor cells frequently encounter shifting metabolic environments

within tumors. The upregulation of mTORC2 by AMPK increased AKT

signaling, which helps support cellular stability and functions and

escape apoptosis when the growth factor is diminished (229). This role of AMPK may appear

paradoxical given its established function in inhibiting mTORC1;

however, it affirms the importance of context-dependent signaling

where AMPK activation can favor survival by engaging mTORC2 while

simultaneously restraining excessive mTORC1 activity.

The clinical efficiency of mTOR inhibitors is

dependent on the progress of developed resistance; there are

numerous connected molecular mechanisms that have been

significantly described. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is a

highly conserved signal transduction pathway in eukaryotic cells

that stimulates cell survival, cell progression, and cell cycle

events, and any malfunction of this signaling pathway can prompt to

tumor development (230). Tumor

cells can modify their response against mTOR inhibitors by

stimulating compensatory persistence pathways that overcome the

therapeutic blockade through various key processes.

The stimulation of receptor tyrosine kinases, such

as IGF-1R, HER2/neu and EGFR is one of the highest prominent

resistance mechanisms against mTOR inhibitors. These receptors can

be overactivated in response to mTOR inhibitors, generating other

signaling pathways that maintain cellular growth and development

(231). Another study has

confirmed that resistance to PI3Kβ/AKT inhibition in PTEN-null

breast cancer cells is conferred by the loss of specific genes in

the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, including TSC1/2, INPPL1 and PIK3R2

relatively than genes connected with different signaling cascades

(232). This result emphasizes

there is an intrinsic pathway of resistance.

Moreover, mutations of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 can reduce

cell dependence on the mTOR pathway for protein biosynthesis and

development regulation. Cancer cells have a special metabolic

shifting that represents another critical feature of developed

resistance, where persistent mTOR inhibition pushes tumor cells to

increase their dependance on different metabolic signaling

pathways, such as GLUT1 stimulation to increase glucose usage

through, aerobic glycolysis, and stimulation of autophagy for

prorogation purpose (233).

Additionally, histone modification, DNA methylation are epigenetic

modifications that significantly contribute to the secure

resistance for several phenotypes, making these modifications

mainly challenging to available chemotherapy (234).

PI3K/AKT rebound activation can be the highest

clinically important limitation of mTOR inhibitors. This phenomenon

occurs through the disturbance of negative-feedback loops in the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis (235). In

addition, the key mechanism has been recorded in the recent

literature, and it is described as the basic challenge for the

single mTOR inhibitor chemotherapy (236). The activation of mTOR causes a

negative feedback-loop control through S6K1 that decreases the

activity of PI3K and S6K1 phosphorylation deactivates IRS-1 that is

required for insulin signaling through PI3K (237). The degradation of IRS-1is

required for the subsequent and constant attenuation of PI3K/AKT

signaling under normal homeostasis conditions (238). Conversely, once mTOR is inhibited

using a single mTOR inhibitor, this negative loop is perturbed,

causing IRS-1 stabilization and accumulation. In addition, use of

mTOR inhibitor will prompt IRS-1stimulation releasing the negative

loop, resulting in paradoxical cascade restimulation (239).

Mechanistically, recent studies have specified more

details about the dynamic of the rebound activation phenomenon.

Inhibition of PI3K cascade blocks phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 through

mTOR which then inhibits translation of PTEN, causing a rebound of

AKT phosphorylation 2-4 h after-treatment (240). This rapid reactivation displays

that the compensatory reaction occurs within hours of treatment

initiation, efficiently reducing the therapeutic margin of mTOR

inhibitors. The accumulated IRS-1 then serves as an effective

upstream activator for PI3K, causing a strong phosphorylation and

activation for PI3K that can surpass the initial level detected

pretreatment (241). The

effective stimulation of PI3K helps to avoid the pro-apoptotic

action of mTOR inhibition, promote cell survival, propagation and

metabolic switching. The consequences of this challenge phenomena

it modifies the cytotoxic or cytostatic intervention effect into a

mysterious progression stimulating signal (242).

Imminent studies aim to employ the connections

between AMPK and mTORC2, mainly focusing on understanding how this

connection can be manipulated to improve treatment efficiency and

cope with resistance mechanisms in tumor cells (243). These adverse dual roles of AMPK

concurrently restraining mTORC1 whereas hypothetically boosting

mTORC2 cascades discloses a new metabolic persistence way that

supports tumor cells to sustain the cellular homeostasis under

metabolic stress, suggesting that efficient therapeutic approach

must hit both mTORCs in combination with AMPK signaling to stop

redeeming persistence mechanisms and shifting metabolic routes.

Targeting the AMPK/mTORC2 signaling cascade opens a

new avenue for groundbreaking tumor therapies and emphasizes

clarifying these complexes' signaling pathways to develop

wide-ranging therapy approaches. The double role of AMPK in

controlling both mTORCs clarifies new opportunities for targeted

treatment approaches in several cancers is illustrated in (Fig. 3).

The complex metabolic switching of cancer cells is

one of the most basic features of tumorigenesis, with AMPK and mTOR

complexes serving as the primary regulators of this pathological

alteration. The metabolism of cancer cells is well-known for its

notable flexibility, enabling tumor cells to survive and

proliferate under different microenvironmental situations through a

metabolic rewiring strategy. The dysregulation of the AMPK/mTOR

crosstalk orchestrates a wide-ranging metabolic renovation in tumor

cells, endorsing enhanced glucose utilization, modified lipid

metabolism, enlarged amino acid uptake, and adjusted nucleotide

biosynthesis to meet the eminent biosynthetic requirements of

rapidly dividing cells. This metabolic elasticity enables tumor

cells to manipulate the Warburg effect, preferring glycolysis even

in oxygen-rich environment, but concurrently sustaining the ability

to use alternative energy sources during nutrient paucity.

The paradoxical role of AMPK in cancer cell

metabolism, acting as both a tumor suppressor through metabolic

control and a survival helper under a severe stress environment,

highlights the complex metabolic modification mechanisms that tumor

cells utilize. Moreover, the metabolic divergence and heterogeneity

detected across different tumor types and even across specific

tumors reveal complex interactions between AMPK/mTOR complexes

signaling pathways and tissue-specific metabolic demands.

Understanding and clarifying these metabolic

complexities is critical for formulating precision innovative

oncology strategies to efficiently eradicate tumor cell metabolism

without damaging normal cell function. As research advances towards

more sophisticated, creative therapeutic approaches, manipulating

the distinctive metabolism of cancer cells across a targeted

variety of AMPK/mTOR pathways provides immense promise for

inventing metabolically based therapy strategies that can subdue

therapeutic challenges and advance patient outcomes against

cancer.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

AA conceived and supervised the review. AA wrote the

draft of the review. SC reviewed and edited the review. AA and NF

revised the review and prepared the figures. All the authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Fan H, Wu Y, Yu S, Li X, Wang A, Wang S,

Chen W and Lu Y: Critical role of mTOR in regulating aerobic

glycolysis in carcinogenesis (review). Int J Oncol. 58:9–19.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hua H, Kong Q, Zhang H, Wang J, Luo T and

Jiang Y: Targeting mTOR for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol.

12(71)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zarogoulidis P, Lampaki S, Turner JF,

Huang H, Kakolyris S, Syrigos K and Zarogoulidis K: mTOR pathway: A

current, up-to-date mini-review (review). Oncol Lett. 8:2367–2370.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lien EC, Lyssiotis CA and Cantley LC:

Metabolic reprogramming by the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway in cancer.

Recent Results Cancer Res. 207:39–72. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Mossmann D, Park S and Hall MN: mTOR

signaling and cellular metabolism are mutual determinants in

cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:744–757. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ramanathan A and Schreiber SL: Direct

control of mitochondrial function by mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

106:22229–22232. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Warburg O: On the origin of cancer cells.

Science. 123:309–314. 1956.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang N, Wang B, Maswikiti EP, Yu Y, Song

K, Ma C, Han X, Ma H, Deng X, Yu R and Chen H: AMPK-a key factor in

crosstalk between tumor cell energy metabolism and immune

microenvironment? Cell Death Discov. 10(237)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Torres Acosta MA, Gurkan JK, Liu Q,

Mambetsariev N, Reyes Flores C, Helmin KA, Joudi AM,

Morales-Nebreda L, Cheng K, Abdala-Valencia H, et al: AMPK is

necessary for Treg functional adaptation to microenvironmental

stress during malignancy and viral pneumonia. J Clin Invest.

135(e179572)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Marafie SK, Al-Mulla F and Abubaker J:

mTOR: Its critical role in metabolic diseases, cancer, and the

aging process. Int J Mol Sci. 25(6141)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Smiles WJ, Ovens AJ, Kemp BE, Galic S,

Petersen J and Oakhill JS: New developments in AMPK and mTORC1

cross-talk. Essays Biochem. 68:321–336. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Keerthana CK, Rayginia TP, Shifana SC,

Anto NP, Kalimuthu K, Isakov N and Anto RJ: The role of AMPK in

cancer metabolism and its impact on the immunomodulation of the

tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 14(1114582)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhang T, Wang X, Alexander PG, Feng P and

Zhang J: An analysis of AMPK and ferroptosis in cancer: A potential

regulatory axis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed).

30(36618)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Liao H, Wang Y, Zou L, Fan Y, Wang X, Tu

X, Zhu Q, Wang J, Liu X and Dong C: Relationship of mTORC1 and

ferroptosis in tumors. Discov Oncol. 15(107)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Sun Z, Liu L, Liang H and Zhang L:

Nicotinamide mononucleotide induces autophagy and ferroptosis via

AMPK/mTOR pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinog.

63:577–588. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wang X, Tan X, Zhang J, Wu J and Shi H:

The emerging roles of MAPK-AMPK in ferroptosis regulatory network.

Cell Commun Signal. 21(200)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lee H, Zandkarimi F, Zhang Y, Meena JK,

Kim J, Zhuang L, Tyagi S, Ma L, Westbrook TF, Steinberg GR, et al:

Energy-stress-mediated AMPK activation inhibits ferroptosis. Nat

Cell Biol. 22:225–234. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sun Q, Zhen P, Li D, Liu X, Ding X and Liu

H: Amentoflavone promotes ferroptosis by regulating reactive oxygen

species (ROS)/5'AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/mammalian

target of rapamycin (mTOR) to inhibit the malignant progression of

endometrial carcinoma cells. Bioengineered. 13:13269–13279.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Chen W, Zhao H and Li Y: Mitochondrial

dynamics in health and disease: Mechanisms and potential targets.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8(333)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Crosas-Molist E, Graziani V, Maiques O,

Pandya P, Monger J, Samain R, George SL, Malik S, Salise J, Morales

V, et al: AMPK is a mechano-metabolic sensor linking cell adhesion

and mitochondrial dynamics to Myosin-dependent cell migration. Nat

Commun. 14(2740)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Liu Q, Zhang L, Zou Y, Tao Y, Wang B, Li

B, Liu R, Wang B, Ding L, Cui Q, et al: Modulating p-AMPK/mTOR

pathway of mitochondrial dysfunction caused by MTERF1 abnormal

expression in colorectal cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci.

23(12354)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Liu A, Lu X, Song Y, Pei J and Wei R: ACK1

condensates promote STAT5 signaling in lung squamous cell

carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 25(237)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Mehta S and Zhang J: Liquid-liquid phase

separation drives cellular function and dysfunction in cancer. Nat

Rev Cancer. 22:239–252. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Peng Q, Tan S, Xia L, Wu N, Oyang L, Tang

Y, Su M, Luo X, Wang Y, Sheng X, et al: Phase separation in cancer:

From the impacts and mechanisms to treatment potentials. Int J Biol

Sci. 18:5103–5122. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Maqsood Q, Sumrin A, Saleem MZ, Perveen R,

Hussain N, Mahnoor M, Akhtar MW, Wajid A and Ameen E: An insight

into cancer from biomolecular condensates. Cancer Screen Prev.

2:177–190. 2023.

|

|

26

|

Li Y, Feng Y, Geng S, Xu F and Guo H: The

role of liquid-liquid phase separation in defining cancer EMT. Life

Sci. 353(122931)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC and Thompson

CB: Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of

cell proliferation. Science. 324:1029–1033. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Warburg O and Minami S: Versuche an

Überlebendem carcinom-gewebe. Klin Wochenschr. 2:776–777. 1923.

|

|

29

|

Lunt SY and Vander Heiden MG: Aerobic

glycolysis: Meeting the metabolic requirements of cell

proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 27:441–464. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Koppenol WH, Bounds PL and Dang CV: Otto

Warburg's contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism.

Nat Rev Cancer. 11:325–337. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Tochigi T, Shuto K, Kono T, Ohira G, Tohma

T, Gunji H, Hayano K, Narushima K, Fujishiro T, Hanaoka T, et al:

Heterogeneity of glucose metabolism in esophageal cancer measured

by fractal analysis of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission

tomography image: Correlation between metabolic heterogeneity and

survival. Dig Surg. 34:186–191. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Larson SM: Positron emission

tomography-based molecular imaging in human cancer: Exploring the

link between hypoxia and accelerated glucose metabolism. Clin

Cancer Res. 10:2203–2204. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

DeBerardinis RJ and Chandel NS:

Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci Adv.

2(e1600200)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ward PS and Thompson CB: Metabolic

reprogramming: A cancer hallmark even Warburg did not anticipate.

Cancer Cell. 21:297–308. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Hsu PP and Sabatini DM: Cancer cell

metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell. 134:703–707. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Li ZY and Zhang HF: Reprogramming of

glucose, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism for cancer

progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 73:377–392. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Kim SY: Cancer energy metabolism: Shutting

power off cancer factory. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 26:39–44.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar