Introduction

Bladder cancer is a common malignancy that ranks as

the 9th most frequently diagnosed malignancy worldwide. This type

of cancer is also ranked 13th in terms of mortality rates, with

developing countries having higher mortality rates than developed

countries (1). Non-muscle invasive

bladder cancer (NMIBC) is a subset of bladder cancer that comprises

tumors of stage Ta, T1 and carcinoma in situ (CIS). It is

estimated that NMIBC accounts for 70-75% of all diagnosed cases of

bladder cancer (2,3).

NMIBC is known to have a high recurrence and

progression rate that depends on the tumor risk profile with the

chance of recurrence at 1 year ranging between 15-61% and 31-78% at

5 years. Progression rates also vary significantly, with the 1-year

progression rate into muscle invasive metastatic bladder cancer

(MIBC) ranging from 0.2-17%, and increasing to 0.8-45% at 5 years

(2). Mortality rates associated

with NMIBC are relatively lower than those associated with MIBC,

and increases with higher-risk tumor features. In patients with

low-grade Ta tumors, the 15-year progression-free survival is 95%

with no cancer-specific mortality. This decreases to 61% in Ta

high-grade Ta tumors, with a disease-specific mortality of 26%.

Patients with T1 tumors have a progression-free survival rate of

44%, with a disease-specific mortality reaching 38% (4). When progression to MIBC occurs,

patients are expected to have a poor prognosis, with a 5-year

mortality rate of 50-70% even following radical cystectomy

(5).

Bladder cancer is among the types of cancer

affecting the elderly with the highest treatment costs, with an

estimated economic burden of approximately US $4 billion per year.

This high cost is attributed to the need for lifelong cystoscopic

surveillance and multiple treatment modalities (6). Transurethral resection of bladder

tumor (TURBT) is the initial treatment of choice, where the tumor

is resected using a resectoscope inserted via the urethra. In this

procedure, it is recommended that all visible tumors be resected

along with the underlying detrusor muscle (7). It is known that the risk of upstaging

NMIBC (≥T2) increases up to 49% in the case that the detrusor

muscle is not obtained during resection (8). TURBT is also associated with a high

recurrence rate, with a 5-year recurrence reaching 42% for T1

tumors (9). To mitigate this risk,

clinicians usually recommend a second TURBT and adjuvant therapy.

The instillation of intravesical chemotherapy is recommended by the

European Association of Urologist (EAU) to reduce the recurrence

rate (10). A previous

meta-analysis demonstrated that immediate postoperative

intravesical chemotherapy reduced recurrence to 37% compared to 48%

with TURBT alone (11). Several

agents, such as mitomycin C, epirubicin, doxorubicin and

gemcitabine are used for this purpose. Mitomycin C is the most

commonly studied drug; however, it is currently not available in

Indonesia (12).

Immunotherapy using bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)

is a widely-recognized first line agent for managing high-risk

NMIBC, according to the European Organization for Research and

Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk calculator (13,14).

Currently, The EAU Guidelines suggest that BCG following TURBT is

more effective in preventing recurrence than TURBT alone or TURBT

with intravesical chemotherapy (10). Despite its efficacy, BCG is

associated with a greater number of side-effects than chemotherapy

(15).

Given the high economic burden associated with

NMIBC, the careful and evidence-based selection of treatment

modalities is essential for optimizing outcomes and efficiency.

There is a need to compare intravesical chemotherapy agents other

than mitomycin C with first-line BCG immunotherapy in the

Indonesian setting. The present study aimed to investigate the

efficacy and safety of gemcitabine-based intravesical chemotherapy

vs. BCG immunotherapy in order to provide a clearer perspective on

which treatment provides a better prognostic value for patients

with NMIBC.

Data and methods

Eligibility criteria

The present systematic review was conducted

according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review

and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The inclusion criteria were

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies of

patients diagnosed with NMIBC comparing the efficacy of and safety

between gemcitabine and BCG immunotherapy following TURBT. Only

English-language articles with available full-texts were included.

No date restrictions were applied. Editorials, commentaries, case

reports and review articles were excluded. The selected studies

were then critically appraised for validity, importance and

applicability using the checklist from Oxford's Centre of Evidence

Based Medicine (CEBM) (https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/critical-appraisal-tools).

Search strategy

A database search was conducted using various

databases, including PubMed, Cochrane, ProQuest and EBSCOhost with

the search strategies detailed in Table S1. Citation searching was

performed in eligible studies and prior systematic reviews to

identify relevant literature not captured through the database

search. An author (FZN) screened both the records and full-text

articles.

Risk of bias assessment and data

extraction

The included studies were assessed using the

Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized control studies (RoB 2.0)

(https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials)

for RCTs or Risk of Bias in the Non-randomized Studies of

Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for observational studies (https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/risk-bias-non-randomized-studies-interventions).

The following data were extracted: The name of the first author and

year of publication, study design, patient risk group and

classification system, details of intervention and comparison

including dosage and BCG strain, and outcomes related to efficacy

and safety. Efficacy outcomes included, but not limited to.

recurrence, progression, mortality rates and recurrence-free

survival. Safety outcomes included any adverse events (AEs), severe

AEs (defined as grade ≥3 AEs resulting in treatment modification)

and the type of AE. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

were performed by one of the authors (FZN), as previously described

(16).

Statistical analysis

The extracted data were tabulated and described

narratively. Where feasible (≥2 studies reporting the same

outcome), data were pooled using inverse-variance random-effects

meta-analysis with risk ratios (RR) as the effect measure.

Random-effects weighting was applied due to variations in patient

risk groups and classifications, intervention types and doses, and

follow-up durations. Given inherent differences in study design and

procedures, analyses and syntheses were prioritized for RCTs.

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi-squared test (with

P<0.10 indicating statistical heterogeneity) and the I²

statistic, categorized as low (0-25%), moderate (26-50%), high

(51-75%), or very high (>75%). Galbraith plots were produced to

identify outliers and visualize heterogeneity. For primary efficacy

(recurrence and progression) and safety outcomes (any and severe

AEs), analyses were further stratified by patient risk group.

However, stratification by risk group classification system, BCG

dose and strain, and follow-up duration was not possible due to

heterogeneous distributions and limited data. Subgroup analysis by

overall risk of bias was also not conducted, as all included

studies were judged to have moderate-to-high risk of bias. As

<10 articles were included, funnel plots were not generated.

Results

Characteristics of the included

studies

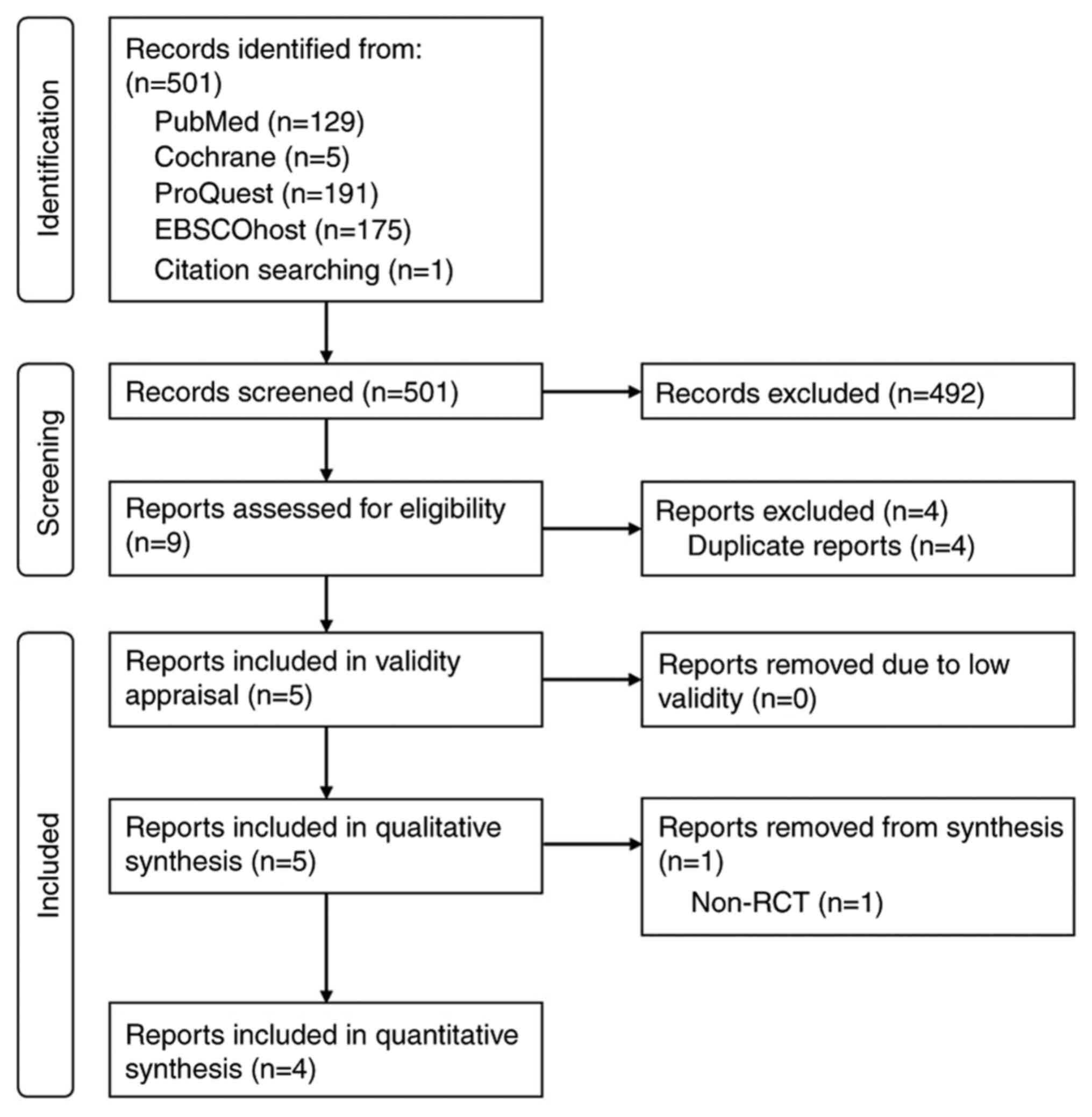

A total of 501 records were retrieved from the

search (Fig. 1). Following

screening, five studies were included: Four RCTs (16-19)

and one prospective cohort study (20). All studies were deemed valid

following critical appraisal using the Oxford's CEBM checklists

(Table SII). Across the five

studies, a total of 447 patients with NMIBC were included, with 224

(50.1%) patients receiving gemcitabine and 223 (49.9%) patients

receiving BCG. All patients in the gemcitabine group received

either a weekly or twice-weekly dose of 2,000 mg gemcitabine in 50

ml normal saline for 6 weeks (induction phase), followed by

maintenance for 12 months in two studies (16,18),

36 months in one study (17) and

an unspecified duration in two studies (19,20).

By contrast, BCG dosing and strain varied by study: Two studies

used the Connaught strain administered weekly for 6 weeks

(induction phase) with a 3-week maintenance schedule (16,18),

two studies used Tice strains administered weekly for 6 weeks

(17,20), and one study did not report a

strain or dosing interval (19).

Patient risk classification was high-risk in two studies (17,18),

low-to-intermediate risk in two studies (16,19),

and mixed in one study (20). The

EAU classification system was used in three studies (16,17,20),

EORTC in one study (18), and was

unspecified in one study (19).

The duration of follow-up ranged from 3 to 60 months (Table I).

| Table IDetails of studies included in the

qualitative synthesis. |

Table I

Details of studies included in the

qualitative synthesis.

| First author, year

of publication | Study design | Chemotherapeutic

agent | Population

characteristics | Intervention | Outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Porena, 2009 | RCT | Gemcitabine and

BCG | • 64 High-risk

superficial bladder cancer patients based on EAU Guideline •

Patients randomized into two groups; Gemcitabine group (n=32) with

mean age 70.2±5.5 and BCG group (n=32) mean age, 68.7±10.2

years | • All patients

underwent first TURBT and bladder mapping to determine the presence

of CIS; 4 weeks later the second TURBT was conducted without prior

instillation of chemotherapeutic agents • Gemcitabine group: 14

days after the second TURBT, the patients received 6 weekly

installations of Gemcitabine with a dose of 2,000 mg diluted in 50

ml saline held in bladder for 2 h and received maintenance therapy

at 3,6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months after TURBT • BCG group: 14

days after the second TURBT, the patients received 6 weekly

installations of Tice-strain BCG with a dose of 5x108

CFU diluted in 50 ml saline held in the bladder for 2 h and

received maintenance therapy at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months

after TURBT • Outcome measured consists of recurrence and

progression rates detected with cystoscopy and TURBT, tolerability

and safety | • Recurrence rate ◦

BCG group: 28,1% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 53,1% ◦ P=0.037 • Mean

recurrence-free survival time ◦ Gemcitabine group: 25.6 months ◦

BCG group: 39.4 months ◦ P=0.042 • Local toxicity (urinary tract

infection, cystitis, dysuria) ◦ BCG group: 12.5% ◦ Gemcitabine

group: 9.4% ◦ P>0.05 • Systemic toxicity (fever) ◦ BCG group:

6.25% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 12.5% ◦ P>0.05 • Rates of persistent

high-risk disease ◦ BCG group: 44.4% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 41.1% ◦

P>0.05 • Rates of regression ◦ BCG group: 55.5% ◦ Gemcitabine

group: 59.2% ◦ P>0.05 | (17) |

| Di Lorenzo,

2010 | RCT | Gemcitabine and

BCG | • 80 High-risk

NMIBC patients based on the EORTC scoring system Patients

randomized into two groups; gemcitabine group (n=40) with mean age

69.3±8.4 and BCG group (n=40) mean age, 71.4±7.9 years • Patients

had a history of treatment failure with BCG | • Gemcitabine

group: 4-6 weeks after the last TURBT 0performed after the failure

of the first treatment with BCG, the patients received twice weekly

intravesical gemcitabine with a dose of 2,000 mg/50 ml for 6 weeks

and maintenance at 2, 6 and 12 months. • BCG group: 4-6 weeks after

the last TURBT performed after the failure of the first treatment

with BCG, the patients received Connaught strain BCG (81 mg/50 ml)

over a 6-week induction course and the maintenance at 3, 6 and 12

months • Outcome measured consist of recurrence and progression

rates detected with cystoscopy and TURBT, and toxicity assessed

with toxicity criteria 3.0 | • Recurrence rate ◦

Gemcitabine group: 52.5%, ◦ BCG group: 87.5% ◦ P=0.002 • Time to

first recurrence ◦ Gemcitabine group: 3.9 months ◦ BCG group 3.1

months ◦ P=0.09 • 2-year recurrence-free survival ◦ Gemcitabine

group: 19% ◦ BCG group: 3% ◦ P<0.008 • Toxicity rate (dysuria,

hematuria, fever, dermatitis, nausea-vomiting) ◦ Gemcitabine group:

37.5% ◦ BCG group: 40% ◦ P>0,05 • Mortality incidence ◦

Gemcitabine group: none ◦ BCG group: 1 ◦ P=0.120 | (18) |

| Bendary, 2011 | RCT | Gemcitabine and

BCG | • 80 Patients

diagnosed with primary stage of Ta-T1 without CIS with mean age

56.2±11.18 years • All patients are randomized into two groups, 40

each, to receive either gemcitabine or BCG. Each group had a

subgroup of Ta and T1 tumors | • Gemcitabine group

received a 6 weekly intravesical instillation after 2 weeks from

resection with a dose of 2,000 mg/50 ml of saline. • BCG group

received a 6 weekly intravesical instillation after 2 weeks from

resection with a dose of 6x108 CU in 50 ml saline. •

Follow-up period range from 3-18 months (mean, 10.8±2.7 months) •

Outcome measured were recurrence rate and progression rate | • Recurrence rate

in Ta patient ◦ BCG group: 26.31% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 22.22% ◦

P=0.92 • Recurrence rate in T1 patient ◦ BCG group: 33.33% ◦

Gemcitabine group: 27.27% ◦ P=0.66 • Overall Recurrence rate ◦ BCG

group: 30% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 25% ◦ P=0.61 • Progression rate ◦

BCG group: 9.5% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 9.1% ◦ P=1.0 • Toxicity rate:

dysuria ◦ BCG group: 35% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 12.5% ◦ P<0.05 •

Toxicity rate: urinary frequency ◦ BCG group: 45% ◦ Gemcitabine

group: 10% ◦ P<0.01 | (19) |

| Gontero, 2013 | RCT | Gemcitabine and

BCG | • 120

Intermediate-risk NMIBC patients based on EAU risk stratification •

Patients are randomized into two groups, Gemcitabine (n=61) and BCG

(nS59) • All patients are BCG naïve and had no prior intravesical

chemotherapy in the last 3 months | • BCG group: 7-15

weeks after previous TURBT, patients received 6 weekly inductions

of Connaught strain BCG 1/3 dose (27 mg) in 50 ml saline and

maintenance of 3 weekly instillations at 3, 6 and 12 months •

Gemcitabine group: 7-15 weeks after previous TURBT, patients

received 6 weekly induction of 2000 mg/50 ml saline of gemcitabine

with maintenance of monthly instillations up to 1 year • Secondary

outcome are recurrence and progression at 1 year and assessment of

toxicity | • 1-year recurrence

rate BCG group: 23.7% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 26.2% ◦ P=0.83 •

Recurrence-free survival ◦ BCG group: 10.4 months ◦ Gemcitabine

group: 10.6 months ◦ P=0.66 • 1-year disease progression rate ◦ BCG

group: 11.6 months ◦ Gemcitabine group: 11.6 months ◦ P=0.5 • Both

local and systemic side effects are more common in BCG group

compared to Gemcitabine group after first induction (56.1% vs

35.7%; P=0.03), but not significant after second induction (40.4

vs. 34.1%; P=0.66) | (16) |

| Prasanna, 2017 | Retrospective

cohort | Gemcitabine and

BCG | • 103 Patients;

gemcitabine group (n=51) and BCG group (n=52) • Patients consisted

of all three different risk group with no significant different in

distribution in each group | • BCG treatment:

initial weekly instillation of Oncotice BCG with a dose of

5x108 CFU with 2 h of retention time for 6 weeks •

Gemcitabine: Weekly instillation of 2,000 mg Gemcitabine for 6

weeks Patients were administered maintenance treatment based on

their recurrence risk profile • Primary outcome is disease-free

survival (DFS) with recurrences confirmed by cystoscopic guided

biopsy and histology • Secondary outcomes include toxicity

examination | • Median follow-up,

15 months • Mean disease-free survival time ◦ BCG group: 19.6

months ◦ Gemcitabine group: Not reached, significantly longer ◦

Unadjusted HR of 0.47 (95% CI, 0.23-0.98, P=0.04) in favour of

gemcitabine • 2-year disease-free survival rate ◦ BCG group: 48.0%

◦ Gemcitabine group: 55.1% ◦ P 0.32 • Adverse event rate ◦ BCG

group: 44% ◦ Gemcitabine group: 7% ◦ P<0.05 | (20) |

Risk of bias assessment

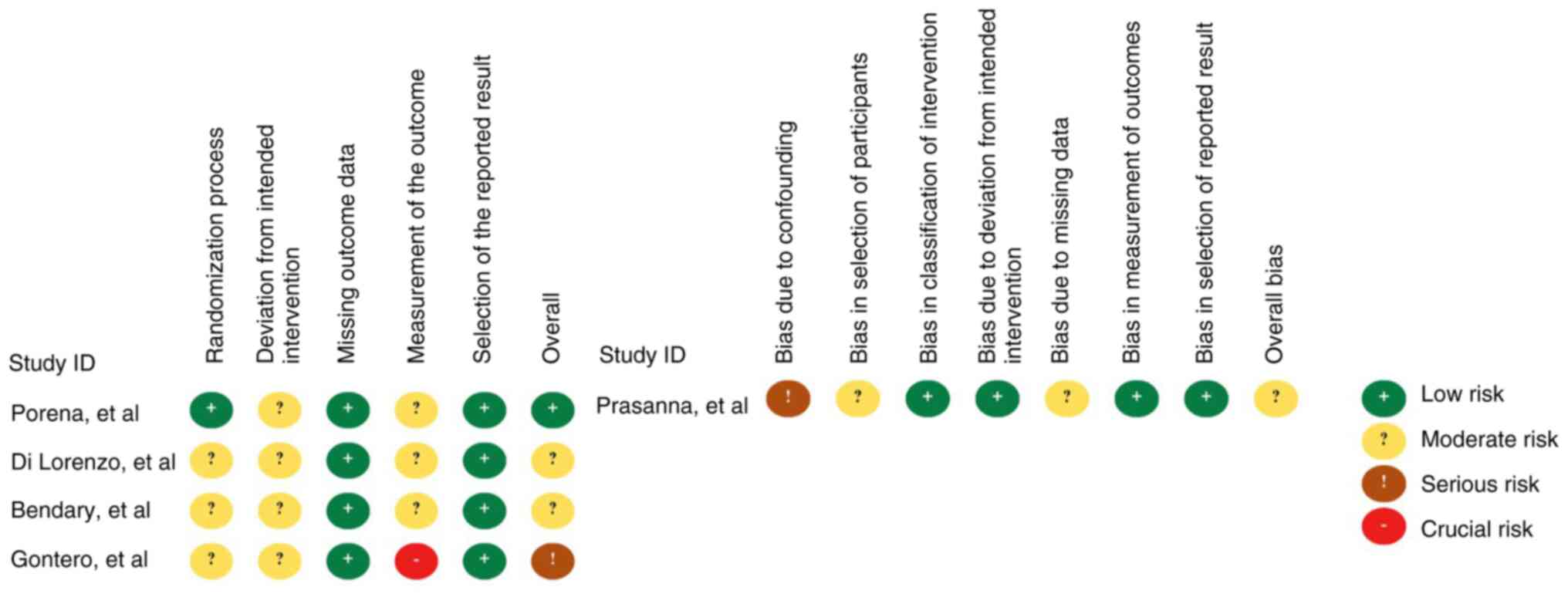

Risk of bias assessment revealed a moderate overall

risk in four studies (16,18-20)

and low risk in only one study (17). Specifically, all four RCTs had some

concerns regarding the risks of deviation from intended

intervention (16-19),

and three RCTs had some concerns from measurement of the outcome

(16,18,19).

Moreover, the study by Prasanna et al (20) had a moderate risk from selection

and attrition bias and a serious risk from confounding effects

(Fig. 2).

Efficacy outcomes

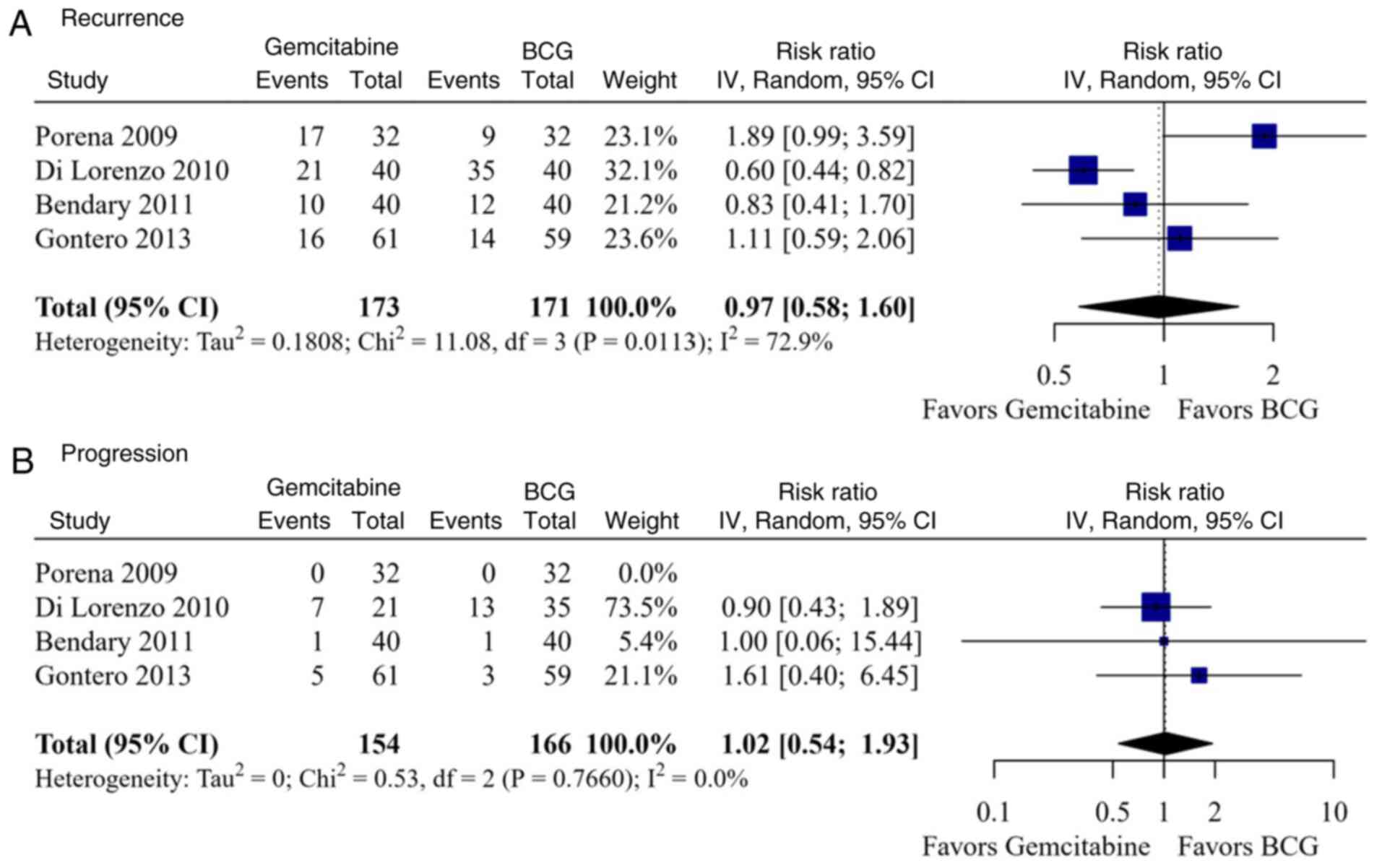

A total of four studies and 344 patients were

included in the meta-analysis of efficacy outcomes. Intravesical

gemcitabine was non-inferior to gemcitabine in terms of recurrence

[relative risk (RR), 0.97; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.58-1.60;

high heterogeneity (I2=72.9%, P=0.011); and progression

(RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.54-1.93); low heterogeneity

(I2=0.0%, P=0.766; Fig.

3]. Recurrence and progression rates were similar between the

groups both in patients with high-risk NMIBC (RR, 1.03; 95% CI,

0.33-3.15; I2=89.8%, P=0.001; and RR, 0.90; 95% CI,

0.43-1.89) and in those with a low-to-intermediate risk (RR, 0.98;

95% CI, 0.61-1.57; I2=0.0%, P=0.559; and RR, 1.46; 95%

CI, 0.42-5.04; I2=0.0%, P=0.760) (Fig. S1). Galbraith plots did not

identify any outlier, although the wide spread of estimates

suggests apparent heterogeneity (Fig.

S1A and B).

Recurrence-free survival was shorter in the

gemcitabine group in one study (mean, 25.6 vs. 39.4 months,

P=0.042) (17), similar in another

(10.6 vs. 10.4 months, P=0.66) (16), and longer in one study (3.9; 95%

CI, 3.0-7.0 vs. 3.1 months 95% CI, 2.2-6.0; P=0.008) (18). Additionally, Di Lorenzo et

al (18) reported a

significantly higher 2-year recurrence-free survival in patients

with NMIBC receiving gemcitabine compared to those receiving BCG

[hazard ratio (HR), 0.15; 95% CI, 0.10-0.30; P<0.008].

Progression-free survival, as reported in the study by Gontero

et al (16), was similar

between gemcitabine and BCG (both mean 11.6 months, P=0.500).

Mortality was reported by only one study, with one death in the BCG

group and none in the gemcitabine group, although the difference

was not statistically significant (P=0.120) (18). Similarly, Porena et al

(17) reported that the rates of

persistent high-risk disease and regression were similar in both

groups (44.4 vs. 41.1% and 55.5 vs. 52.9%, respectively; both

P-values non-significant) (Table

I).

Safety outcomes

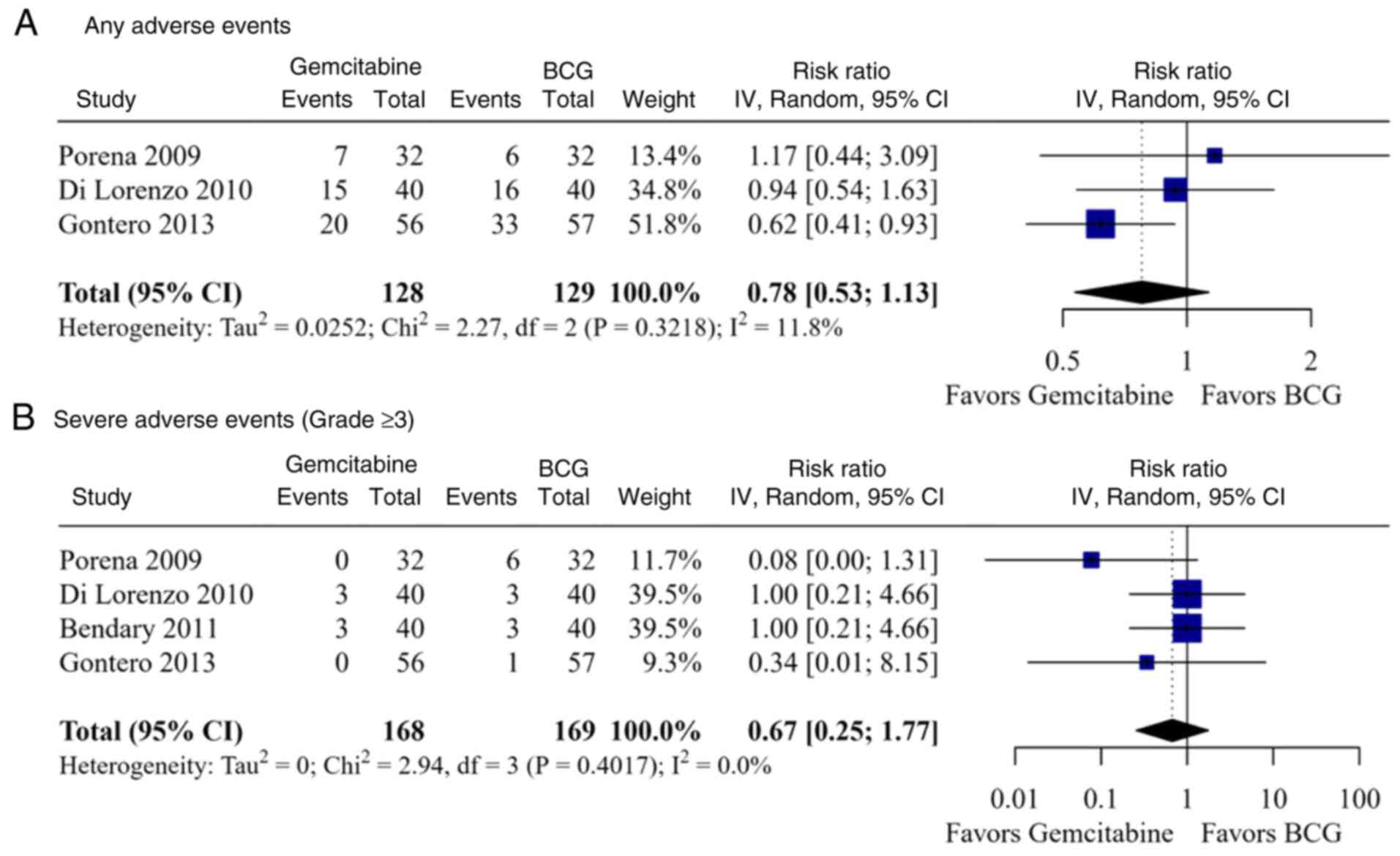

A total of four studies comprising a total of 337

patients were included in the meta-analysis of safety outcomes. The

overall risk of AEs was similar between the gemcitabine and BCG

groups (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.53-1.13; I2=11.8%; P=0.322)

(Fig. 4A), as well as among

patients with high-risk disease (RR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.61-1.60;

I2=0.0%; P=0.702) and low-to-intermediate risk disease

(RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.41-0.93) (Table

II). Similarly, the rate of severe AEs, defined as grade ≥3 AEs

requiring treatment modifications, did not differ significantly

between the groups overall (RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.25-1.77;

I2=0.0%; P=0.402) (Fig.

4B), or when stratified by patient risk classification

(high-risk: RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.03-4.28; I2=58.8%;

P=0.119; low-to-intermediate risk: RR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.20-3.25;

I2=0.0%; P=0.549) (Table

II). Galbraith plots identified no outlier, although the

limited data may constrain further interpretation (Fig. S1C-H).

| Table IISummary of meta-analysis results for

efficacy and safety outcomes from the included randomized

controlled trials |

Table II

Summary of meta-analysis results for

efficacy and safety outcomes from the included randomized

controlled trials

| A, Primary

outcomes |

|---|

| | No. of patients;

event/no. | | Heterogeneity |

|---|

| Outcome | No. of studies | Gemcitabine | BCG | RR (95% CI) | I2 | P-value |

|---|

| Efficacy | | | | | | |

| Recurrence | | | | | | |

|

Overall | 4 | 64/173 | 70/171 | 0.97

(0.58-1.60) | 72.9% | 0.011 |

|

High-risk | 2 | 38/72 | 44/72 | 1.03

(0.33-3.15) | 89.8% | 0.001 |

|

Low-to-intermediate

risk | 2 | 26/101 | 26/99 | 0.98

(0.61-1.57) | 0.0% | 0.559 |

| Progression | | | | | | |

|

Overall | 3 | 13/122 | 17/134 | 1.02

(0.54-1.93) | 0.0% | 0.766 |

|

High-risk | 1 | 7/21 | 13/35 | 0.90

(0.43-1.89) | NA | NA |

|

Low-to-intermediate

risk | 2 | 6/101 | 4/99 | 1.46

(0.42-5.04) | 0.0% | 0.760 |

| Safety | | | | | | |

|

Any AE | | | | | | |

|

Overall | 3 | 42/128 | 65/129 | 0.78

(0.53-1.13) | 11.8% | 0.322 |

|

High-risk | 2 | 22/72 | 32/72 | 0.99

(0.61-1.60) | 0.0% | 0.702 |

|

Low-to-intermediate

risk | 1 | 20/56 | 33/57 | 0.62

(0.41-0.93) | NA | NA |

| Severe AE (grade

≥3) | | | | | | |

|

Overall | 4 | 6/168 | 13/169 | 0.67

(0.25-1.77) | 0.0% | 0.402 |

|

High-risk | 2 | 3/72 | 9/72 | 0.37

(0.03-4.28) | 58.8% | 0.119 |

|

Low-to-intermediate

risk | 2 | 3/96 | 4/97 | 0.81

(0.20-3.25) | 0.0% | 0.549 |

| B, Secondary

outcomes |

| Efficacy | | | | | | |

|

Mortality | 1 | 0/21 | 1/35 | 0.55

(0.02-12.92) | NA | NA |

|

Persistence

of high-risk disease | 1 | 13/32 | 14/32 | 0.93

(0.69-1.24) | NA | NA |

|

Regression | 1 | 17/32 | 18/32 | 0.94

(0.75-1.19) | NA | NA |

| Safety | | | | | | |

| Local AEs | | | | | | |

|

Dysuria | 4 | 27/168 | 4/169 | 0.59

(0.39-0.89) | 0.0% | 0.674 |

|

Hematuria | 2 | 2/96 | 14/97 | 0.21

(0.03-1.32) | 32.7% | 0.223 |

|

Dermatitis | 1 | 2/40 | 0/40 | 5.00

(0.25-100.93) | NA | NA |

|

Urinary

frequency | 1 | 4/40 | 18/40 | 0.22

(0.13-0.37) | NA | NA |

|

Bladder

spasm | 1 | 3/56 | 1/57 | 3.05

(0.98-9.54) | NA | NA |

|

Urge

incontinence | 1 | 3/56 | 6/57 | 0.51

(0.26-1.01) | NA | NA |

|

Itching | 1 | 3/56 | 9/57 | 0.34

(0.18-0.64) | NA | NA |

|

Skin

rash | 1 | 1/56 | 1/57 | 1.02

(0.25-4.13) | NA | NA |

| Systemic AEs | | | | | | |

|

Fever | 3 | 1/128 | 15/129 | 0.17

(0.04-0.76) | 0.0% | 0.569 |

|

Nausea and

vomiting | 2 | 5/72 | 0/72 | 5.94

(0.73-48.31) | 0.0% | 0.875 |

|

Asthenia | 1 | 1/32 | 0/32 | 3.00

(0.13-70.96) | NA | NA |

|

Neutropenia

and thrombocytopenia | 1 | 2/40 | 0/40 | 5.00

(0.25-100.93) | NA | NA |

According to the type of AE, patients receiving

gemcitabine had significantly lower risks of dysuria (four studies;

RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.39-0.89; I2=0.0%; P=0.674), fever

(three studies; RR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.04-0.76; I2=0.0%;

P=0.569), urinary frequency (one study; RR, 0.22; 95% CI,

0.13-0.37) and itching (one study; RR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18-0.64);

whereas the risk was similar for other local (hematuria: RR, 0.21;

95% CI, 0.03-1.32; I2=32.7%; P=0.223; bladder spasms:

RR, 3.05; 95% CI, 0.98-9.54; dermatitis: RR, 5.00; 95% CI,

0.25-100.93; skin rash: RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.25-4.13; and urge

incontinence: RR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.26-1.01) and systemic (nausea and

vomiting: RR, 5.94; 95% CI, 0.73-48.31; I2=0.0%;

P=0.875; asthenia: RR, 3.00; 95% CI, 0.13-70.96; and neutropenia

and thrombocytopenia) AEs (Table

II).

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis

included four RCTs comprising 344 patients and one retrospective

cohort study with 103 patients. The earliest RCT was conducted by

Porena et al (17) in 2010

among high-risk superficial bladder cancer patients based on the

EAU risk classification system. BCG was administered as a 6-weekly

instillation of 5x108 CFU of Tice strain BCG retained

intravesically for 2 h (17).

Gemcitabine was administered as a 6-weekly instillation of 2,000

mg, also retained for 2 h. In that study, BCG was associated with a

lower recurrence rate (28.1 vs. 53.1%) and a longer recurrence-free

survival than gemcitabine (17).

These findings are in contrast to those of the other three RCTs

included in the present study.

Di Lorenzo et al (18) compared these treatments in patients

with high-risk NMIBC (per EORTC scoring system) who had previously

failed BCG therapy. In their study, BCG (Connaught strain, 81 mg/50

ml) was administered 4-6 weeks after the first treatment failure,

over a 6-week induction followed by maintenance at 3, 6 and 12

months. The gemcitabine group received 2,000 mg/50 ml over a period

of 6 weeks and similar maintenance at 2, 6 and 12 months (18). In contrast to the study by Porena

et al (17), the study by

Di Lorenzo et al (18)

found lower recurrence rates and a higher 2-year recurrence-free

survival in the gemcitabine group, with no significant differences

in time-to-recurrence or progression. This was the only study to

include BCG-refractory patients, which may explain the divergent

findings from that of Porena et al (17).

In their study, Bendary et al (19) included patients with primary Ta-T1

tumors without CIS and reported no significant differences in

recurrence or progression rates between BCG and gemcitabine. In

that study, BCG was administered at 6x108 CFU (strain

unspecified) and gemcitabine at 2,000 mg in 50 ml saline, both over

6 weekly 2-h instillations (19).

Similarly, Gontero et al (16) found no significant difference in

recurrence, recurrence-free survival, or progression in

intermediate-risk patients with NMIBC. Their BCG regimen used

one-third dose (27 mg) of Connaught strain over a 6-week induction

period. Gemcitabine was administered identically across studies

(2,000 mg/50 ml, 6-week induction) (16).

Prasanna et al (20) conducted a retrospective cohort

study on patients with CIS, pTa and pT1 tumors, stratified into

EAU-defined risk groups. BCG (Oncotice strain, 5x108

CFU) and gemcitabine (2,000 mg) were administered as 6 weekly

instillations. Despite baseline differences in risk-group

distribution, adjusted multivariate analysis revealed no difference

in disease-free survival between the groups (20). All studies agreed that gemcitabine

had a more favorable safety profile, with fewer local and systemic

adverse events, leading to better tolerability and quality of

life.

The variability in the findings across these five

studies is largely attributable to clinical and methodological

heterogeneity. Porena et al (17) included only high-risk patients per

EAU criteria, which included patients with NMIBC with CIS, all T1

tumors without CIS, Ta LG/G2 without CIS with three risk factors,

Ta HG/G3 without CIS and with two risk factors, and T1 G2 without

CIS and with one risk factor (10). Conversely, Gontero et al

(16) focused on intermediate-risk

NMIBC, and accordingly reported no difference in outcomes between

gemcitabine and BCG. Di Lorenzo et al (18) used the EORTC scoring system to

define high risk (recurrence score >9 and/or progression score

>13). Although EORTC risk classification may slightly outperform

EAU in predicting recurrence (c-index 0.64 vs. 0.62; P=0.035), the

key distinguishing feature in the study by Di Lorenzo et al

(18) was the inclusion of

BCG-refractory patients, not the risk model used.

Bendary et al (19) and Prasanna et al (20) included broader and less

well-defined populations. In the study by Bendary et al

(19), the inclusion of all Ta-T1

tumors without CIS spanned a wide risk spectrum but lacked proper

risk stratification. By contrast, Prasanna et al (20) used similarly broad criteria but

stratified patients into EAU risk groups, strengthening the

interpretation of findings. BCG regimens also varied. Although

strain and dose differences existed, a previous meta-analysis of 65

trials involving >12,000 patients concluded that no strain

demonstrated clear superiority (21). Gontero et al (16) used a one-third dose of the

Connaught strain in intermediate-risk patients to reduce toxicity

without sacrificing efficacy. Gemcitabine regimens were consistent

across studies. Only Di Lorenzo et al (18) included patients with prior BCG

failure, and only in this context did gemcitabine demonstrate

superior efficacy.

The findings presented herein align with those of

prior reviews. Shelley et al (22) reported that gemcitabine was

comparable to BCG in intermediate-risk patients, inferior in

high-risk, and superior in BCG-refractory NMIBC. However, the

present systematic review included more representative populations

from Bendary et al (19)

and Prasanna et al (20),

both demonstrating no efficacy difference across wider risk groups.

Similarly, the Cochrane review by Jones et al (23) found gemcitabine less effective in

high-risk NMIBC, comparable in intermediate-risk, and more

effective in BCG-refractory patients. A separate meta-analysis also

revealed no significant difference in recurrence (HR, 1.04; 95% CI,

0.38-2.89) or progression (HR, 0.01; 95% CI, -0.75 to 0.77) between

the two agents (24).

Overall, the findings of the present systematic

review and meta-analysis suggest that intravesical gemcitabine was

non-inferior to BCG immunotherapy in terms of efficacy, while it

resulted in lower rates of dysuria, fever, urinary frequency and

itching. However, intravesical gemcitabine appears particularly

useful for patients with BCG-refractory NMIBC. In this population,

the EAU recommends radical cystectomy (11), although it remains an invasive

procedure with significant morbidity and mortality, and entails

major lifestyle changes (25).

Intravesical gemcitabine may therefore serve as a non-invasive

alternative for NMIBC patients unresponsive to BCG

immunotherapy.

The superiority of gemcitabine over BCG in

BCG-refractory NMIBC may be explained by several factors. BCG, as

with other immunotherapies, relies on an intact immune system to

activate innate immunity and initiate BCG-specific and

tumor-specific T-cell responses. Although the exact mechanisms

remain unclear, BCG failure is considered to result from complex

interactions between host immunity and tumor microenvironment,

leading to immune dysregulation and inadequate immune activation.

Specifically, non-responders have been shown to be associated with

increased levels of CD25+ regulatory T-cells and

tumor-associated macrophage, enrichment of exhausted

CD8+PDL-1(+) T-cells, and reduced levels of

Th2-predominant CD4+ T-cells within the tumor

microenvironment (26). By

contrast, gemcitabine inhibits tumor DNA synthesis, leading to

apoptosis, and is therefore less dependent on host immune function

(23). Its lower risk of adverse

events may be attributed to its immune-selective cytotoxicity and

high plasma clearance, allowing any drug that enters systemic

circulation to be rapidly eliminated (23). Furthermore, BCG is a

live-attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis that activates

a strong immune response and induces inflammation following

urothelial invasion (27), which

contributes to a higher incidence of local and systemic

side-effects (27,28).

In conclusion, the present systematic review and

meta-analysis demonstrated that intravesical gemcitabine was

non-inferior to BCG immunotherapy in the treatment of patients with

NMIBC and may serve as a viable option for those unresponsive to

BCG. Although the overall risk of AEs was comparable, gemcitabine

was associated with lower rates of dysuria, fever, urinary

frequency and itching. Further high-quality RCTs with larger sample

sizes, standardized dosing, treatment intervals, and follow-up

durations are warranted to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Material

(A-H) Galbraith plots visualizing

heterogeneity across the meta-analyses of efficacy and safety

outcomes.

Key words used during the database

search.

Validity and applicability assessment

of the experimental studies passed the initial screening.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

FZN and ARAHH were involved in the study conception

and design. FZN was involved in the acquisition of data and in the

drafting of the manuscript. FZN, ARAHH, CAM and FR were involved in

the analysis and interpretation of data. ARAHH and CAM critically

revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. FZN and

FR performed the statistical analysis. ARAHH and CAM provided

administrative, technical and material support (data analysis

coaching) and supervised the study as required. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript. All authors confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Antoni S, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Znaor

A, Jemal A and Bray F: Bladder cancer incidence and mortality: A

global overview and recent trends. Eur Urol. 71:96–108.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Isharwal S and Konety B: Non-muscle

invasive bladder cancer risk stratification. Indian J Urol.

31:289–296. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Kamat AM, Hahn NM, Efstathiou JA, Lerner

SP, Malmström PU, Choi W, Guo CC, Lotan Y and Kassouf W: Bladder

cancer. Lancet. 388:2796–2810. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Herr HW: Tumor progression and survival of

patients with high grade, noninvasive papillary (TaG3) bladder

tumors: 15-year outcome. J Urol. 163:60–62. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Park JC, Citrin DE, Agarwal PK and Apolo

AB: Multimodal management of Muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Curr

Probl Cancer. 38:80–108. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mossanen M and Gore JL: The burden of

bladder cancer care: Direct and indirect costs. Curr Opin Urol.

24:487–491. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kim LHC and Patel MI: Transurethral

resection of bladder tumour (TURBT). Transl Androl Urol.

9:3056–3072. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Herr HW and Donat SM: Quality control in

transurethral resection of bladder tumours. BJU Int. 102:1242–1246.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Martin-Doyle W, Leow JJ, Orsola A, Chang

SL and Bellmunt J: Improving selection criteria for early

cystectomy in high-grade T1 bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of

15,215 patients. J Clin Oncol. 33:643–50. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R,

Kaasinen E, Böhle A and Palou J: others: EAU guidelines on

non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). Eur Urol,

2021.

|

|

11

|

Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W and Van Der

Meijden APM: A single immediate postoperative instillation of

chemotherapy decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with

stage Ta T1 bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of published results of

randomized clinical trials. J Urol. 171:2186–2190. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Maa Y, Djatisoesanto W and Hardjowijoto S:

Profile of bladder transitional cell cancer in Soetomo Hospital

Surabaya. Indones J Urol. 21:1–6. 2014.

|

|

13

|

Porten SP, Leapman MS and Greene KL:

Intravesical chemotherapy in Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Indian J Urol. 31:297–303. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

in nBean J and Sylvester R: Results of

EORTC Genito-Urinary Group phase III trial 30911 [Internet]. 2010

Mar 12 [cited 2025 Aug 22]. Available from: EORTC website.

|

|

15

|

Sylvester RJ, van der MEIJDEN AP and Lamm

DL: Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin reduces the risk of

progression in patients with superficial bladder cancer: A

meta-analysis of the published results of randomized clinical

trials. J Urol. 168:1964–1970. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gontero P, Oderda M, Mehnert A, Gurioli A,

Marson F, Lucca I, Rink M, Schmid M, Kluth LA, Pappagallo G, et al:

The impact of intravesical gemcitabine and 1/3 dose bacillus

Calmette-Guérin instillation therapy on the quality of life in

patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: Results of a

prospective, randomized, phase II trial. J Urol. 190:857–862.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Porena M, Del Zingaro M, Lazzeri M,

Mearini L, Giannantoni A, Bini V and Costantini E: Bacillus

calmette-guérin versus gemcitabine for intravesical therapy in

high-risk superficial bladder cancer: A randomised prospective

study. Urol Int. 84:23–27. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Di Lorenzo G, Perdonà S, Damiano R,

Faiella A, Cantiello F, Pignata S, Ascierto P, Simeone E, De Sio M

and Autorino R: Gemcitabine versus bacille Calmette-Guérin after

initial bacille Calmette-Guérin failure in non-muscle-invasive

bladder cancer: A multicenter prospective randomized trial. Cancer.

116:1893–1900. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Bendary L, Khalil S, Shahin A and Nawar N:

1655 intravesical gemcitabine versus bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG)

in treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: Short term

comparative study. J Urol. 185:e664–e665. 2011.

|

|

20

|

Prasanna T, Craft P, Balasingam G,

Haxhimolla H and Pranavan G: Intravesical gemcitabine versus

intravesical bacillus calmette-guérin for the treatment of

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: An evaluation of efficacy and

toxicity. Front Oncol. 7:1–5. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Boehm BE, Cornell JE, Wang H, Mukherjee N,

Oppenheimer JS and Svatek RS: Efficacy of bacillus Calmette-guérin

strains for treatment of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: A

systematic review and network Meta-Analysis. J Urol. 198:503–510.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Shelley MD, Jones G, Cleves A, Wilt TJ,

Mason MD and Kynaston HG: Intravesical gemcitabine therapy for

non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC): A systematic review.

BJU Int. 109:496–505. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Jones G, Cleves A, Wilt TJ, Mason M,

Kynaston HG and Shelley M: Intravesical gemcitabine for non-muscle

invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane database Syst Rev.

1(CD009294)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Lu JL, Xia QD, Lu YH, Liu Z, Zhou P, Hu HL

and Wang SG: Efficacy of intravesical therapies on the prevention

of recurrence and progression of non-muscle-invasive bladder

cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cancer Med.

9:7800–7809. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hurle R, Casale P, Morenghi E, Saita A,

Buffi N, Lughezzani G, Colombo P, Contieri R, Frego N, Guazzoni G

and Lazzeri M: Intravesical gemcitabine as bladder-preserving

treatment for BCG unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Results from a single-arm, open-label study. BJUI Compass.

1:126–132. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Maroof H, Paramore L and Ali A: Theories

behind bacillus Calmette-Guérin failure in high-risk

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer and update on current

management. Cancer Pathog Ther. 2:74–80. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Jiang S and Redelman-Sidi G: BCG in

bladder cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel).

14(3073)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Akbulut I, Ödemiş İ and Atalay S: Analysis

of local and systemic side effects of bacillus Calmette-Guérin

immunotherapy in bladder cancer: A retrospective study in Türkiye.

PeerJ. 13(e18870)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|