Introduction

Cheese production has long relied on animal-derived

rennet, a complex of proteolytic enzymes primarily chymosin

extracted from the stomach lining of young ruminants. However,

growing global demand for cheese, coupled with ethical, religious,

dietary and environmental concerns, has accelerated the search for

sustainable alternatives to animal rennet. Vegetarianism, the rise

of vegan products and issues regarding animal welfare have

intensified the need for microbial milk-clotting enzymes (MCEs),

which provide a scalable and animal-free solution for coagulating

milk during cheese manufacture (1). Among microbial sources, filamentous

fungi have attracted increasing attention due to their high enzyme

productivity, the ease of cultivation under diverse conditions, and

the ability to secrete extracellular enzymes with milk-clotting

potential (2,3).

The genus Penicillium, well-known for its

enzymatic versatility, includes several species with the capacity

to produce proteases that exhibit milk-clotting activity. However,

a number of microbial proteases are often accompanied by high

levels of non-specific proteolytic activity, which can adversely

affect cheese texture and flavor due to excessive casein hydrolysis

(4). Therefore, an ideal

milk-clotting enzyme should possess a high milk-clotting activity

(MCA)-to-proteolytic activity (PA) ratio, ensuring specificity

toward κ-casein the key substrate responsible for casein micelle

destabilization and curd formation. In this context, exploring

novel fungal strains capable of producing enzymes with a favorable

MCA/PA profile is a critical step toward developing viable

alternatives to animal rennet (5).

Recent advances made in enzyme biotechnology have

enabled the identification, production and biochemical

characterization of fungal MCEs with industrial potential.

Solid-state fermentation (SSF), in particular, has emerged as an

efficient technique for fungal enzyme production due to its cost

effectiveness, high product yield, and alignment with sustainable

waste management practices. Agricultural residues such as wheat

bran and rice husks serve as inexpensive substrates for fungal

growth, rendering SSF a preferred method for enzyme production in

resource-limited settings (6). The

optimization of SSF parameters, including pH, temperature, inoculum

size, metal ion supplementation and fermentation time is essential

to maximize enzyme yields and ensure functional integrity (7).

In the present study, an extracellular MCE produced

by Penicillium purpurescens was optimized under SSF

conditions using wheat bran as a substrate. The effects of

processing variables, such as incubation temperature, medium pH,

calcium ion supplementation and inoculum size were systematically

evaluated to identify the optimal conditions for MCE production.

The enzyme was subsequently purified through acetone precipitation

and ion-exchange chromatography, and its molecular mass was

estimated via SDS-PAGE. Kinetic characterization, including the

determination of the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km),

provided insight into substrate affinity and enzymatic efficiency,

which are crucial for evaluating its industrial applicability.

The enzyme exhibited a molecular mass of 29 kDa,

high specificity toward κ-casein, and optimal activity in the

temperature range of 45-55˚C across a broad pH spectrum (5.0-10.0),

which are desirable traits for industrial cheese-making

applications. Furthermore, the enzyme demonstrated notable thermal

and pH stability, rendering it suitable for various dairy

processing conditions. The influence of metal ions on enzyme

activity revealed significant a enhancement in of Ca2+

and Mg2+, which are commonly present in milk and known

to stabilize casein micelles, while heavy metals, such as

Hg2+ and Cu2+ were inhibited; these findings

are findings consistent with those of previous research on

microbial MCEs (8,9).

Compared to conventional calf rennet, the enzyme

derived from Penicillium purpurescens demonstrates

comparable clotting performance with a lower proteolytic

degradation of milk proteins, indicating its potential as a

functional rennet substitute. The food industry is increasingly

moving towards greener, animal-free and sustainable processes, and

fungal MCEs provide a promising platform for innovation in this

domain. Moreover, fungal enzymes have been deemed to be generally

recognized as safe (GRAS) by regulatory bodies such as the FDA,

further supporting their adoption in dairy processing (FAO/WHO,

2021) (10).

It was thus hypothesized that Penicillium

purpurescens can produce a MCE with a favorable MCA/PA ratio

under optimized solid-state fermentation conditions. The present

study aimed not only to characterize the biochemical and functional

properties of a novel MCE from Penicillium purpurescens, but

also to lay the groundwork for its application in commercial cheese

production. Although the genus Penicillium includes several

species known for their proteolytic and clotting activities, there

are limited or no detailed reports on the milk-clotting potential

of P. purpurescens, rendering the present study a novel

contribution to the search for effective microbial coagulants.

However, further is required to focus on recombinant expression

systems, enzyme immobilization techniques and pilot-scale cheese

trials to establish its efficacy across diverse cheese types and

processing conditions.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and culture

conditions

All the fungal strains used in the present study

were obtained from the laboratory of the Department Microbial

Chemistry at the National Research Centre in Cairo, Egypt. The

strains were maintained by sub-culturing them on slants of solid

Czapek Dox medium containing: glucose, 30 g/l; NaNO, 2 g/l;

KH2 PO4, 1 g/l;

MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g/l; KCl, 0.5 g/l and agar,

20 g/l (BDH Chemicals Limited) at 28˚C and then stored at 4˚C. The

inoculum size was adjusted by manually counting the spores.

Screening of different organisms for

MCE production

All organisms were cultivated in liquid Czapek Dox

medium (BDH Chemical, Ltd.), containing (g/l): glucose, 30; NaNO,

2; KH2PO4, 1; MgSO4.7

H2O, 0.5; KCl, 0.5 and following incubation at 28˚C for

5 days, the cultures were centrifuged at 5,000 x g, for 10 min at

room temperature to obtain cell-free supernatants as crude enzyme

extracts. These extracts were assayed for milk-clotting activity

(MCA) by mixing 0.5 ml enzyme with 4.5 ml pre-warmed (35˚C)

reconstituted skim milk containing CaCl2, and the

clotting time was recorded visually. The activity was expressed in

arbitrary units relative to the time required for visible

coagulation. To assess non-specific proteolysis, proteolytic

activity (PA) was determined by incubating enzyme with azocasein,

(Merck KGaA) (or casein), followed by trichloroacetic acid (TCA;

El-Gomhouria Company), precipitation and measurement of soluble

peptides spectrophotometrically. The ratio of MCA to PA was then

calculated for each organism to evaluate enzyme suitability for

cheesemaking. Organisms with high MCA and high MCA/PA ratio were

considered the best candidates and selected for further

purification and characterization, as shown Table I.

| Table IScreening of different organisms for

MCE production. |

Table I

Screening of different organisms for

MCE production.

| Tested strains | Milk-clotting

activity MCA/ml (mean ± SD) |

|---|

| Scopulariopsis

brevicaulis - natural potato | - |

| Penicillium

javanicum - exo- dox | - |

| Aspergillus

flavus - dox | - |

| Aspergillus

flavus - natural potato | - |

| Penicillium

purpurescens | 190±3.4 |

| Penicillium

oxalicum - exo | - |

| Penicillium

oxalicum - endo | - |

| Aspergillus

ustus - dox | - |

| Aspergillus

ustus - potato | - |

| Aspergillus

phoenix - exo | - |

| Aspergillus

phoenix - endo | - |

| Erytherma

sp. - exo- dox | - |

| Penicillium

oxalicum - endo | - |

| Curvularia sp.

DHE5 | 60.8±2.1 |

| Aspergillus

Fumigatus | - |

| Aspergillus

tamari DHE10 homogenate | - |

| Streptomyces

aurecens | - |

| Penicillium

politans | - |

| Aspergillus

oryzae static - dox | - |

| Aspergillus

oryzae static - PDA | - |

| Aspergillus

oryzae shaking - dox | - |

| Aspergillus

oryzae shaking - PDA | 102±3.4 |

| Noh2 | 45±1.2 |

| New Aspergillus

sp. - endo | - |

Chemicals and reagents

All chemicals and analytical-grade reagents used in

the present study were procured from Merck KGaA. Skimmed milk

powder (for MCA assays) was obtained from a local commercial

supplier (El-Nasr Co. for Dairy Products). Wheat bran substrate was

provided by ARMA Food Industries.

Optimization of fermentation

conditions. Evaluation of different culture media for MCE

production

The effects of various culture media on MCE

production were investigated using both submerged fermentation

(SmF) and SSF under static and shaking conditions. A total of 10

liquid media were evaluated, including natural potato broth,

Sabouraud dextrose broth, Czapek Dox broth, modified Czapek Dox

with 5% sucrose and peptone, modified Czapek Dox with 5% sucrose

and NaNO3, starch nitrate broth, malt extract broth,

yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) broth, synthetic potato

dextrose agar (PDA) broth and a specific medium (Merck KGaA)

(11). For each medium, 50 ml were

inoculated with 1 ml spore suspension (7x106 spores/ml)

and incubated at 28˚C for 7 days under static and shaking (180 rpm)

conditions. Additionally, eight agro-industrial residues, namely

wheat bran, sugarcane bagasse, banana peel, guava seeds, corn

stover, pomegranate peel, tangerine peel and sawdust (purchased

from the local Arma Food Industry, Egyptian Company for solid waste

recycling) were screened as solid substrates for MCE production in

SSF. For SSF experiments, 5 g of each substrate were moistened with

5 ml distilled water, sterilized (121˚C for 15 min) and then

inoculated with 1 ml of the same spore suspension. The mixtures

were homogenized and incubated at 28˚C for 7 days. For enzyme

extraction, the content of each flask was mixed with 100 ml of 0.05

M extraction buffer (Na-citrate, citric acid, pH 6.0) (1:10, w/v).

The culture was mechanically agitated at 180 rpm in a shaking

incubator (Benchmark Scientific Inc.) at 28˚C for 30 min. The

mixture was then filtered to separate the mycelia from the medium.

The supernatant (crude-enzyme extract) developed was utilized for

MCE activity and determination of protein content, the method

described by Nema et al (12). Through this optimization process,

the ideal cultivation conditions for Penicillium

purpurescens were determined to be as follows: A moisture

content maintained between 60-70%, an aeration level of 75%,

shaking at 180 rpm, a temperature range of 28-30˚C, an initial pH

of 6.0-6.5 and an incubation period of 5 days.

Initial pH. The effect of incubation pH on

MCE production was examined in the pH range of 3.0 to 10. The media

pH was adjusted using either dilute HCl or dilute NaOH

(El-Gomhouria Company) prior to autoclaving the bran (13).

Incubation temperature. Temperature was

optimized for the growth and production of MCE by incubating the

flasks containing the inoculated bran with pH 6, at 20, 25, 30, 35,

40 and 45˚C for 7 days (13).

Fermentation time. The MCE activity was

monitored at 24-h intervals for up to 240 h. MCE production at

optimum pH 6 and temperature 28˚C was followed. At the end of each

time point, the extent of MCE production was determined as

described by Vishwanatha et al (13).

Inoculum size. A total of 5 g of wheat bran

was moistened with 5 ml distilled water (pH 6) and autoclaved. The

substrate was inoculated with different volumes of the same spore

suspension (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 ml). The flasks were

incubated at 25˚C for 5 days.

Analysis of the effect of the

CaCl2 concentration on MCE

Different volumes of the substrate (milk +

CaCl2) were tested (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2,

2.5 and 3 ml) against the same volume of the enzyme.

Determination of MCA

The MCA was determined using the method previously

described by Kumar et al (14), based on the appearance of the first

discontinuous particles and expressed in Soxhlet units (SU). The

enzyme solution was incubated at 35˚C for 10 min before being added

to skim milk (10% wt/vol, containing 10 mM CaCl2 (Merck

KGaA), which had been pre-incubated at the same temperature for 5

min. The reaction was terminated once discontinuous particles

formed. The MCA was calculated using the following formula:

SU=(2,400 x VS x N)/(T x VE), where VS represents the skim milk

volume (ml), N is the MCE dilution factor, T is the milk-clotting

time (seconds) and VE is the volume of the MCE (ml) used in the

assay.

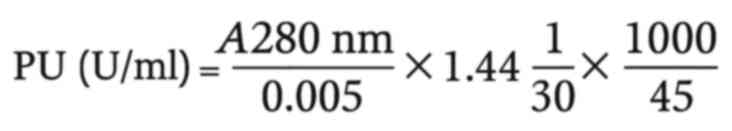

Determination of PA

PA was determined using N,N-dimethyl casein

(DMC) (Merck KGaA) as the substrate, following the method described

in the study by Fan et al (15). In brief, 45 µl enzyme solution were

combined with 45 µl substrate solution (10 mg/ml DMC in 20 mM

potassium phosphate buffer, pH 5.8) and incubated at 35˚C for 30

min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 350 µl of 100

mg/ml trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (El-Gomhouria Company), followed

by incubation on ice for 20 min to precipitate undigested proteins.

The samples were centrifuged at 2,000 x g for 15 min at 22˚C, and

the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 280 nm (UNICO

advanced UV-VISIBLE spectrophotometer). A blank was prepared for

each sample by adding TCA before the enzyme to correct for

non-enzymatic hydrolysis. A total of one unit of PA [measured in

proteolytic units (PU)] was defined as the amount of enzyme that

releases 1 µg tyrosine per minute at 35˚C, using a tyrosine

extinction coefficient (ε) of ml/µg for quantification:

MCE purification

The crude enzyme solution was fractioned by acetone

and the active fraction with high MCA was further purified by

passing through a column (1.5x40 cm) of DEAE-cellulose (Pharmacia

Fine Chemicals AB) pre-equilibrated with 0.02 M sodium phosphate

buffer at pH 6. The elution of protein was then carried out by the

batch-wise addition of 40 ml portions of increasing molarities

(0.0-0.4 M) of NaCl in 0.02 M phosphate buffer at pH 6. Fractions

of 5 ml each were collected at room temperature (25˚C) at a flow

rate of ~20 ml/h. The eluted fractions from the DEAE-cellulose

column were dialyzed against cold distilled water to remove excess

NaCl. The resulting purified enzyme solution was aliquoted into

multiple test tubes, each containing 2 ml, and stored at -20˚C for

later use. Under these storage conditions, the enzyme remained

stable for >1 month. However, subjecting the enzyme to more than

three freeze-thaw cycles resulted in approximately a 21% loss of

activity. The enzyme remains active in the refrigerator for up to 1

week (16).

Determination of MCE purity and

concentration

The molecular weight of the enzyme was determined

using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(SDS-PAGE) following the method described by Laemmli (17). A 12% acrylamide gel was prepared,

and protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie Blue

R-250 (Merck KGaA) at room temperature for 1 h, followed by

de-staining until clear background was obtained. Zymography was

performed in two steps: First, native-PAGE was conducted using a

12% polyacrylamide gel without SDS, as described by Snoek-van

Beurden and Von den Hoff (18)

with minor modifications. Samples were loaded without prior

boiling.

Effect of pH and temperature on

Penicillium purpurescens MCE

To evaluate the effect of pH on the MCA of

Penicillium purpurescens, the enzyme activity was assayed at

different pH values ranging from 3.0 to 8.0. Substrate buffer

solutions were prepared using: 0.05 M citrate buffer for pH

3.0-6.0, and 0.05 M phosphate buffer for pH 6.5-8.0. Each reaction

mixture adjusted to the desired pH. The optimal pH was defined as

the pH exhibiting the highest MCA. To assess the influence of

temperature on MCA, enzyme assays were performed at temperatures

ranging from 20 to 80˚C.

Effect of metal ions on Penicillium

purpurescens MCE

The Penicillium purpurescens MCE was

dissolved in solutions containing 10 or 50 µM Na+,

Ca2+, Mg2+, Hg2+ and

Cu2+, respectively, and incubated for 30 min at 40˚C.

The changes in MCA were measured, with the MCA of the untreated

control (no metal ions) set as 100%.

Kinetic measurement for Penicillium

purpurescens MCE

The kinetic parameters of fungal MCE were determined

using a modified version of the method described by He et al

(19). Casein solutions at varying

concentrations (0.1 and 3.0 g/l) were used as substrates to measure

the PA following the protocol described in the study by Kumar et

al (14). The Michaelis-Menten

constant (Km) and maximal velocity (Vmax) were

derived from a Lineweaver-Burk double-reciprocal plot, as

established by Lineweaver and Burk (20). This analysis provided insight into

the catalytic efficiency and substrate affinity of the enzyme.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. All

reported values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation

(SD). Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 17.0 (IBM

Corp.). Comparisons between two groups were performed using a

t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results and Discussion

Screening of different organisms for

MCE production

The MCA of various fungal and bacterial strains,

measured in MCA/ml is presented in Table I. Among the tested strains, only a

few exhibited detectable MCA, while the majority did not exhibit

any activity. Penicillium purpurescens demonstrated the

highest MCA (190±3.4 MCA/ml), suggesting its potential as a robust

MCA. Aspergillus oryzae under shaking conditions in PDA

medium (Materials and methods) also exhibited notable activity

(102±3.4 MCA/ml), indicating that cultivation conditions

significantly influence enzyme production (9,21).

Curvularia lunata DHE5 and Noh2 displayed moderate activity

(60.8±2.1 and 45±1.2 MCA/ml, respectively), which may warrant

further optimization for industrial applications. The absence of

MCA in the majority of strains, including Scopulariopsis

brevicaulis, Penicillium javanicum and various

Aspergillus and Penicillium species, suggests that

MCEs are strain-specific and not universally produced (22). The variability in MCA between

different growth conditions (static vs. shaking, dox vs. PDA)

highlights the importance of optimizing fermentation parameters for

maximal enzyme yield (23).

Effect of different media on MCE

production using SSF and SmF (shaking and static conditions)

The results obtained (Table II) revealed variations in MCE

production by Penicillium purpurescens across different

media, aligning with findings from other fungal studies in Table I. For example, Aspergillus

oryzae exhibited high MCE activity in wheat bran-based SSF

(24), comparable to the optimal

performance observed in Penicillium purpurescens under

similar conditions. Likewise, Thermomucor indicae-seudaticae

N31 was investigated using submerged fermentation with 4% wheat

bran in a 0.3% saline solution, incubated at 45˚C and 150 rpm for

72 h (25), Furthermore, in

solid-state fermentation of Mucor racemosus, molasses and

casein were identified as significant carbon and nitrogen sources

(26). Further emphasized is the

role of substrate composition in fungal enzyme production,

demonstrating that lignocellulosic substrates significantly

influence MCE yields in SSF. The lack of clotting activity in

Sabouraud and natural potato media for Penicillium

purpurescens is consistent with reports on Neurospora

intermedia, which also displayed low enzyme production in

similar nutrient-limited substrates (27). These comparisons underscore the

critical influence of media composition on fungal MCE production,

with SSF often proving superior due to better fungal growth and

enzyme induction, as demonstrated by Penicillium

purpurescens and other fungi such as Aspergillus

oryzae.

| Table IIEffect of different media on

Penicillium purpurescens MCE production using SSF and SmF

(shaking (180 rpm) and static). |

Table II

Effect of different media on

Penicillium purpurescens MCE production using SSF and SmF

(shaking (180 rpm) and static).

| A, SmF |

|---|

| | Milk-clotting

activity MCA/ml | |

|---|

| Medium | Shaking (mean ±

SD) | Static (mean ±

SD) | P-value |

|---|

| Synthetic potato

dextrose broth | 0.0 | 0.0 | - |

| Modified dox

(NaNO3+5% sucrose) | 290±3 | 266±0.7 | 0.079 |

| Yeast extract

peptone dextrose | 0.0 | 213.3±2.5 | 0.0001a |

| Malt broth | 290±5.1 | 80±1.8 | 0.005a |

| Czapex dox | 133.3±3.1 | 100± | 0.075 |

| Starch nitrate | 100±2 | 260±1.9 | 0.0001a |

| Specific

medium | 0.0 | 290±4.5 | 0.0001a |

| Modified dox (5%

sucrose + yeast + peptone) | - | - | - |

| Natural potato | - | - | - |

| Sabouraud | - | - | - |

| B, SSF |

| Agricultural

waste | Shaking (mean ±

SD) | Static (mean ±

SD) | P-value |

| Wheat bran | 320±1.3 | 106±2.5 | 0.0001a |

| Sugar cane

baggase | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Banana peel | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Guava seeds | 94±2.1 | 21±1.98 | 0.005a |

| Rough corn

stover | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Pomegranate

peel | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Tangerine peel | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Saw dust | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

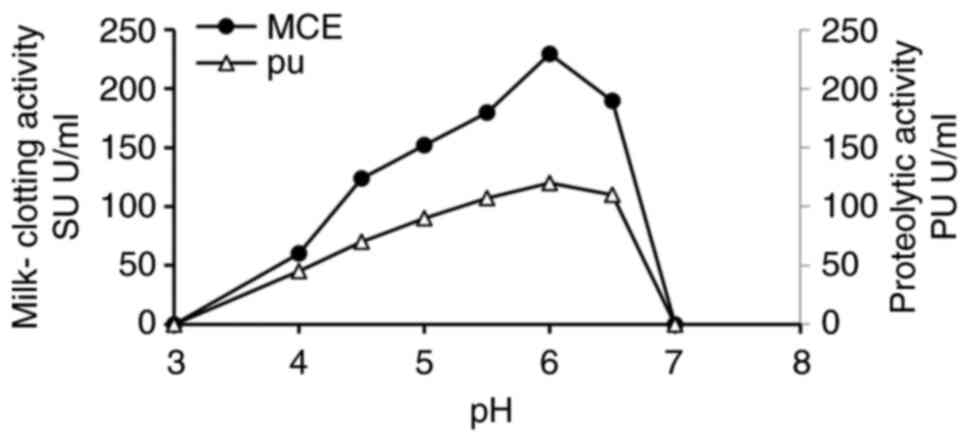

Effect of pH on Penicillium

purpurescens MCE

As illustrated in Fig.

1, the pH of the culture medium significantly influenced both

MCE production and PA in Penicillium purpurescens, with

optimal activity observed at near-neutral pH (6.0-6.5). No activity

was detected at highly acidic (pH 2-3) or alkaline (pH 7)

conditions, while a progressive increase was noted from pH 4 to 6,

peaking at pH 6 (188 MCE units, 120 PU). This trend is in

accordance with findings in other fungi, such as Aspergillus

oryzae, which exhibited maximal MCE activity at pH

5.5-6.0(24), and Mucor

racemosus, which exhibited optimal production at pH 4.8

(3,26). Similarly, Neurospora

intermedia demonstrated reduced enzyme yields at extreme pH

levels, emphasizing the importance of near-neutral conditions for

fungal protease stability and secretion (27). The sharp decline in Penicillium

purpurescens activity at pH 7 suggests enzyme denaturation or

impaired fungal metabolism under alkaline conditions, a phenomenon

also observed in Bacillus spp (28), which are known to produce enzymes

that remain stable across a broad pH range (6.0-10.0).

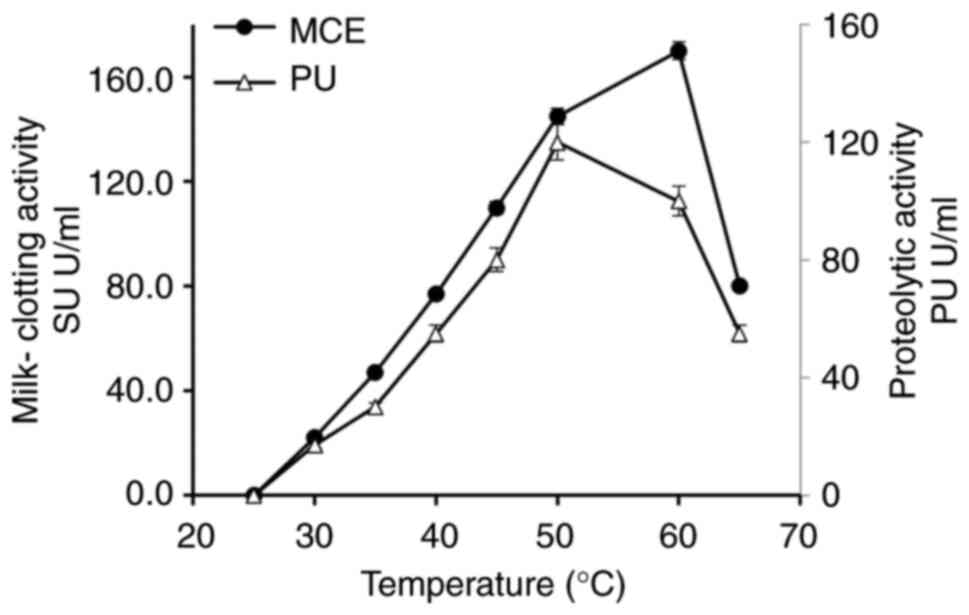

Effect of temperature on Penicillium

purpurescens MCE production

The initial temperature significantly influences the

production of MCE and PA in Penicillium purpurescens. As

demonstrated in Fig. 2, the MCE

and PA increased with temperature, peaking at 50˚C (145 U/ml MCE,

120 U/ml PU), followed by a sharp decline beyond 60˚C due to enzyme

denaturation. Similar trends have been observed in other fungi,

such as Aspergillus oryzae and Rhizopus miehei, which

exhibit optimal MCE production at 30-40˚C and 45-55˚C, respectively

(24,29). Aspergillus niger has also

been shown to exhibit a reduced PA >50˚C, suggesting that

thermal stability is common among fungal enzymes. These findings

highlight the importance of optimizing temperature for maximal

enzyme yield and stability in microbial MCE production.

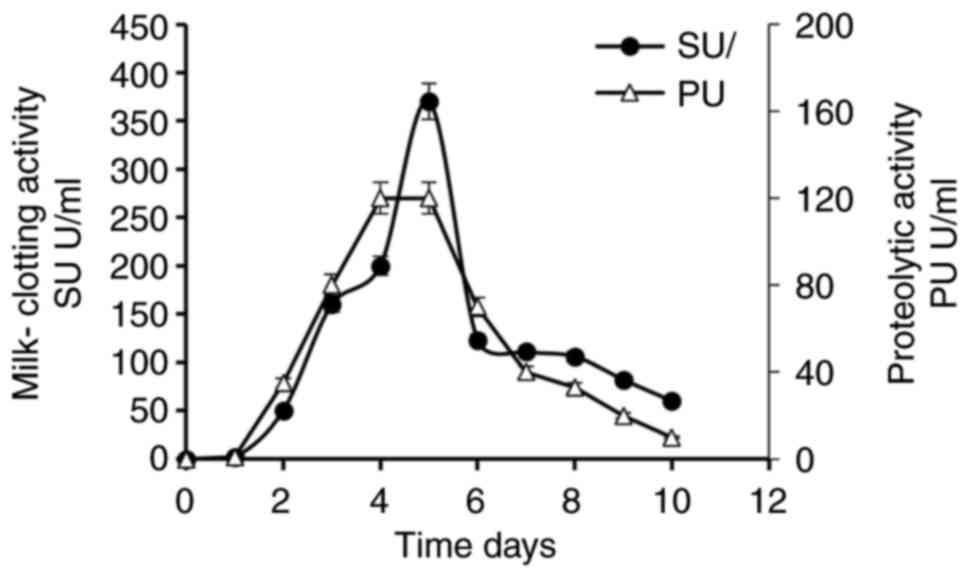

Fermentation time

The effect of fermentation time on Penicillium

purpurescens MCE production and proteolytic activity follows a

trend where enzyme activity initially increases with time before

declining due to proteolytic degradation or nutrient depletion. As

demonstrated in Fig. 3, optimal

MCE production often occurs between 4-5 days, coinciding with peak

fungal biomass and secondary metabolite secretion (30). Beyond this period, prolonged

fermentation leads to reduced enzyme stability and increased

proteolytic degradation, as observed in Penicillium

purpurescens, where MCE activity decreased after day 4. Similar

patterns have been observed in other fungi, such as Aspergillus

oryzae and Rhizomucor miehei, where maximal MCE yield

was achieved within 3-5 days before the activity diminishes

(24,31). In the present study, the MCE

demonstrated a ratio of 320, which is higher than the reported

ratios for commercial counterparts and moderately close to that of

calf rennet (~433), suggesting promising industrial potential, As

shown in Table III,

Aspergillus niger exhibits peak protease secretion at 72-96

h, after which activity declines due to autolysis. In contrast, the

enzyme from Thermomucor indicae-seudaticae N31 was

successfully used in the production of high-quality Prato cheese,

maintaining stability without changes over 60 days (32). These findings highlight the

importance of optimizing fermentation duration to balance enzyme

yield and stability, which may vary across species.

| Table IIIComparative MCA/PA ratios of fungal

and animal rennets. |

Table III

Comparative MCA/PA ratios of fungal

and animal rennets.

| Source | MCA (SU/mg) | PA (U/mg) | MCA/PA Ratio | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Penicillium

purpurescens | 620 | 2.0 | 320 | Present study |

| Rhizomucor

miehei | 450 | 2.2 | ~204 | (32) |

| Mucor

pusillus | 520 | 3.8 | ~137 | (25) |

| Calf rennet | 650 | 1.5 | ~433 | (46) |

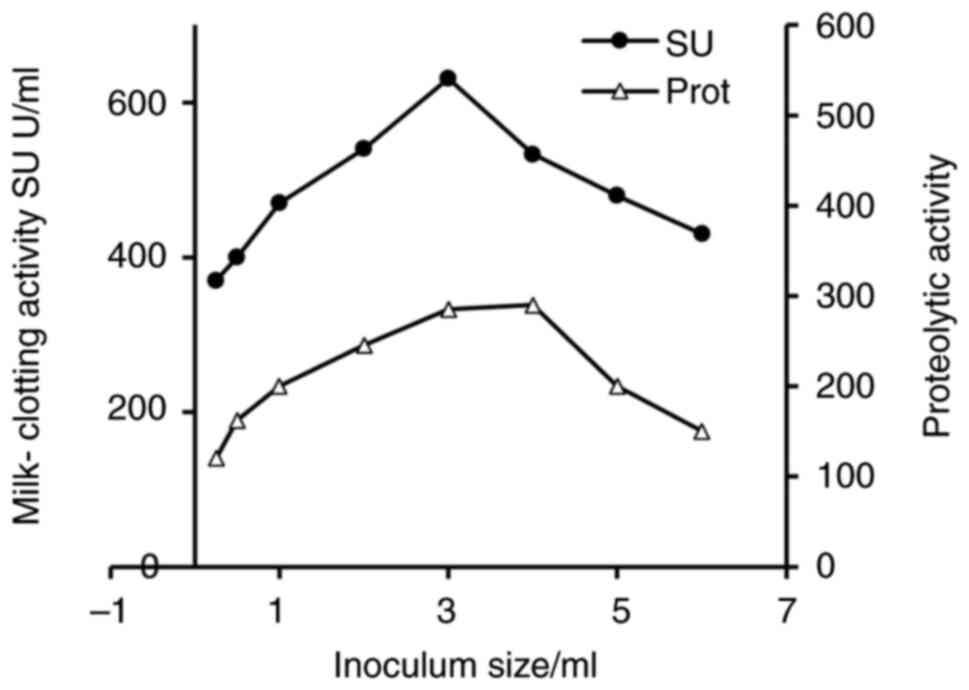

Effect of inoculum size on Penicillium

purpurescens MCE production

As illustrated in Fig.

4, the inoculum size significantly influenced the production of

MCE and PA in Penicillium purpurescens. Research has shown

that increasing the inoculum size from 0.25 to 3 ml enhances both

enzyme activity (from 370 to 631 SU) and proteolytic activity (from

120 to 285 U/ml), likely due to improved fungal biomass and

nutrient utilization (33).

However, beyond 3 ml, a decline in MCE activity (533 SU at 4 ml)

and PA (290 U/ml), occurs, possibly due to nutrient depletion or

metabolic stress. Similar trends have been observed in other fungi,

such as Aspergillus oryzae, and Aspergillus clavatus,

where optimal inoculum size (1-2x106 spores/ml)

maximizes protease production, while higher densities reduce yields

due to oxygen limitation (24,33).

Likewise, Rhizopus microsporus exhibits peak MCE activity at

5% (v/v) inoculum, with declines at higher concentrations (34,35).

These findings suggest that inoculum optimization is critical for

balancing microbial growth and enzyme synthesis across fungal

species.

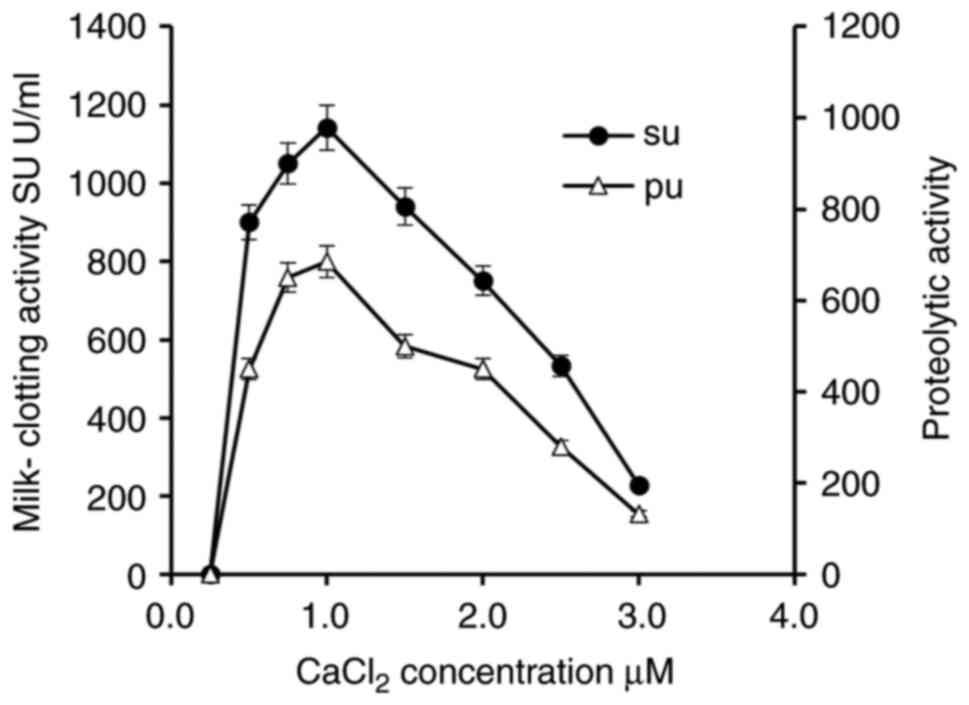

Effect of CaCl2 on

Penicillium purpurescens MCE

As demonstrated in Fig.

5, MCA peaked at 1% CaCl2 (1,140 U/ml), while PA

reached its maximum level (685 U/ml) at the same concentration.

Higher CaCl2 levels (>1%) lead to a decline in both

MCA and PA, suggesting enzyme inhibition or destabilization at an

elevated ionic strength. Similar trends have been observed in other

fungi, such as Bacillus velezensis DB219, where optimal MCE

production occurred at 0.5-1% CaCl2 beyond which

activity decreased due to possible metal ion interference with

enzyme stability (36).

Rhizopus miehei also exhibited reduced proteolytic activity

at CaCl2 concentrations above 1.5%, attributed to

conformational changes in the enzyme (37). These findings highlight the

critical role of Ca2+ in modulating fungal MCE activity,

with species-specific optimal thresholds. The decline in

Penicillium purpurescens MCE beyond 1% CaCl2

aligns with previous research on Neurospora crassa, where

excessive Ca2+ disrupted secretion pathways (38) underscoring the delicate balance

between cation stimulation and inhibition in fungal enzyme

systems.

MCE preparation and purification

As illustrated in Fig.

6, the purification of the MCE from Penicillium

purpurescens involves fractionation steps that enhance specific

activity, as evidenced by the data exhibiting increased activity in

fractions 7-9, with peak specific activities of 286. 296 and 320

U/mg U/mg, respectively. These fractions likely contain the

purified enzyme, as indicated by their high specific activities

compared to earlier fractions with negligible activity. Similar

purification trends have been observed in other fungal species,

such as Aspergillus oryzae and Rhizomucor miehei,

also produce proteases with milk-clotting properties (24,37).

For instance, Rhizomucor miehei yields a highly active

aspartic protease (rennin-like enzyme) after purification, with

specific activities comparable to those of P. purpurescens

(37). However, some fractions

(e.g., 10-12) exhibit variability, possibly due to contamination or

partial denaturation. Further purification steps, such as

ion-exchange or gel-filtration chromatography, could improve

homogeneity, as demonstrated in Aspergillus niger protease

purification (23). These data

suggest that Penicillium purpurescens is a promising source

of milk-clotting enzymes, with purification efficiency comparable

to other industrially relevant fungi.

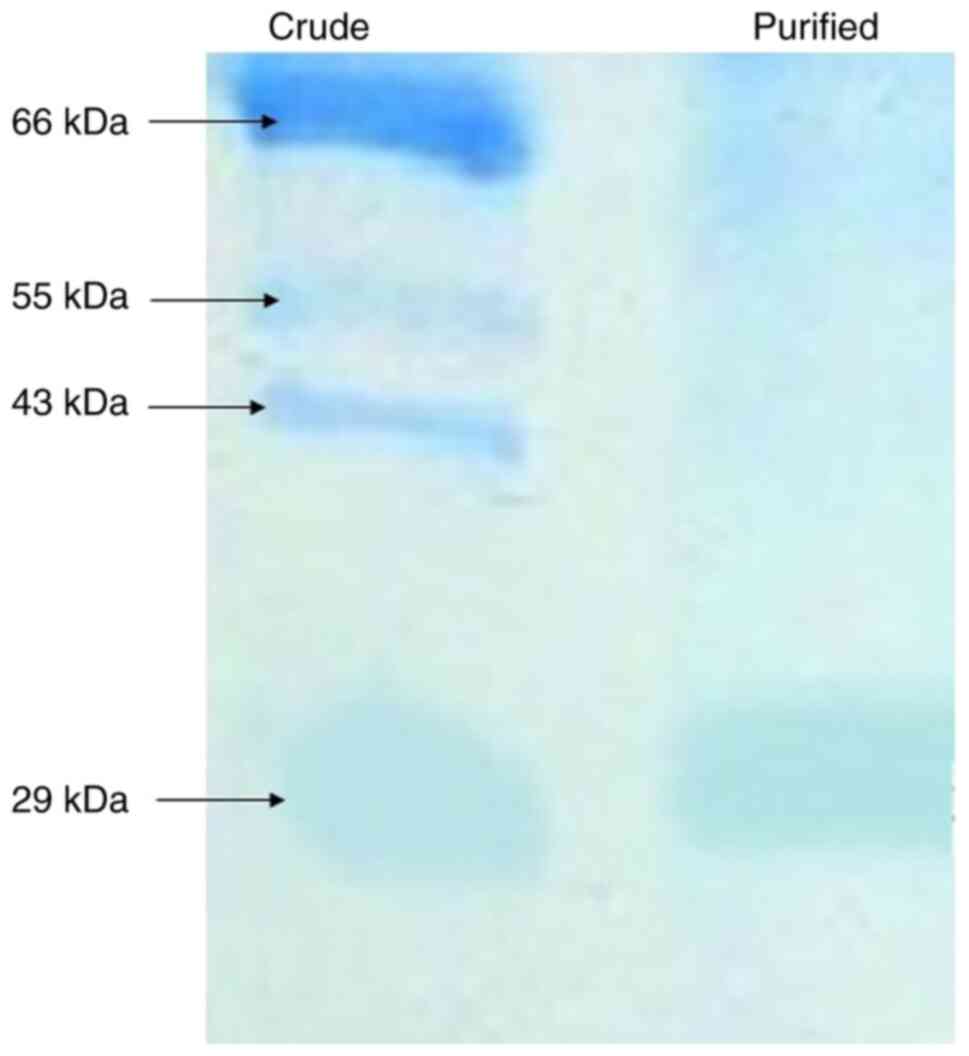

Molecular weight of Penicillium

purpurescens MCE

The MCE from Penicillium purpurescens has a

molecular weight of ~29 kDa (Fig.

7), which is comparable to other fungal aspartic proteases used

in cheese production. For instance, Rhizomucor miehei

produces a 38.6-kDa aspartic protease (rennet) (37), while Aspergillus oryzae

secretes a 43-kDa MCE (39).

Similarly, Endothia parasitica yields a 33.8 kDa protease

(40). The lower molecular weight

of Penicillium purpurescens enzyme suggests structural

differences that may influence substrate specificity and thermal

stability. These fungal enzymes are preferred over animal rennet

due to their cost-effectiveness and suitability for vegetarian

cheese production. Further comparative studies on their biochemical

properties could optimize their industrial applications.

Effect of pH and temperature on cheese

quality

The MCA of the enzyme produced by Penicillium

purpurescens exhibited a distinct dependence on pH, with

optimal activity observed at pH 6, as shown in Fig. 1, where the enzyme reached a maximum

activity of 336 MCE/ml. This result suggests that the enzyme

functions best under mildly acidic to neutral conditions, aligning

with observations from other microbial MCEs. For instance, similar

pH optima have been reported for enzymes derived from Mucor

pusillus and Rhizomucor miehei, which also exhibit peak

MCA around pH 5.5-6.5 (37,41).

The activity was significantly lower at both extreme acidic (pH 3,

120 MCE/ml) and alkaline (pH 10, 200 MCE/ml) conditions, indicating

a narrow optimal pH range for maximum proteolytic efficiency.

Fungal milk-clotting enzymes, as all enzymes, are sensitive to pH;

deviations from their optimal pH range can lead to decreased

stability and a reduced ability to bind to their substrate, milk

proteins. This phenomenon underscores the critical need to control

pH during dairy processing to ensure optimal enzyme performance,

which directly impacts the efficiency and quality of products such

as cheese (42).

The MCE derived from Penicillium purpurescens

exhibited a pronounced temperature-dependent activity profile.

Enzyme activity increased steadily from 30˚C, reaching its maximum

at 50˚C with an activity of 360 U/ml, which indicates this

temperature as optimal for catalytic function, as shown in Fig. 2. A sharp decline in activity was

observed at 55˚C, suggesting the onset of thermal denaturation;

however, the enzyme retained partial activity at 60˚C. Beyond this

temperature, activity decreased markedly, with complete

inactivation occurring at 90˚C. This thermal behavior is consistent

with MCEs from other fungal species, such as Rhizomucor

miehei and Mucor pusillus, which generally show optimal

activity within the 45-55˚C range and lose enzymatic function at

elevated temperatures due to structural instability (37,41).

These observations underscore the critical need for precise

temperature control when employing fungal MCEs such as MCE from

Penicillium purpurescens in industrial processes such as

cheese manufacturing.

Effect of metal ions on Penicillium

purpurescens MCE activity

As demonstrated in Table IV, a marked influence of various

metal ions was observed on the MCE activity of Penicillium

purpurescens. The data revealed that Ca2+ (50 µM)

enhanced enzyme activity by 150%, suggesting a potential

stabilizing or activating role, while Mg2+ (50 µM) also

promoted activity (120%), albeit to a lesser extent. By contrast,

Cu2+ (10 µM) and Hg2+ (10 µM) markedly

inhibited MCE function, reducing activity to 40 and 10%,

respectively, likely due to metal-induced protein denaturation or

active-site interference (43).

The negligible effect of Na+ (10 µM; 95% activity)

implies that monovalent ions may have minimal impact on this enzyme

system. These findings align with recent studies highlighting the

dual role of metal ions as either cofactors or inhibitors in fungal

MCE kinetics (44).

| Table IVEffect of metal ions on

Penicillium purpurescens MCE activity. |

Table IV

Effect of metal ions on

Penicillium purpurescens MCE activity.

| Metal ion | Concentration

(µM) | Relative activity

(%) |

|---|

|

Ca2+ | 10 | 110 |

|

Ca2+ | 50 | 150 |

|

Mg2+ | 50 | 120 |

|

Cu2+ | 10 | 40 |

|

Hg2+ | 10 | 10 |

| Na+ | 10 | 95 |

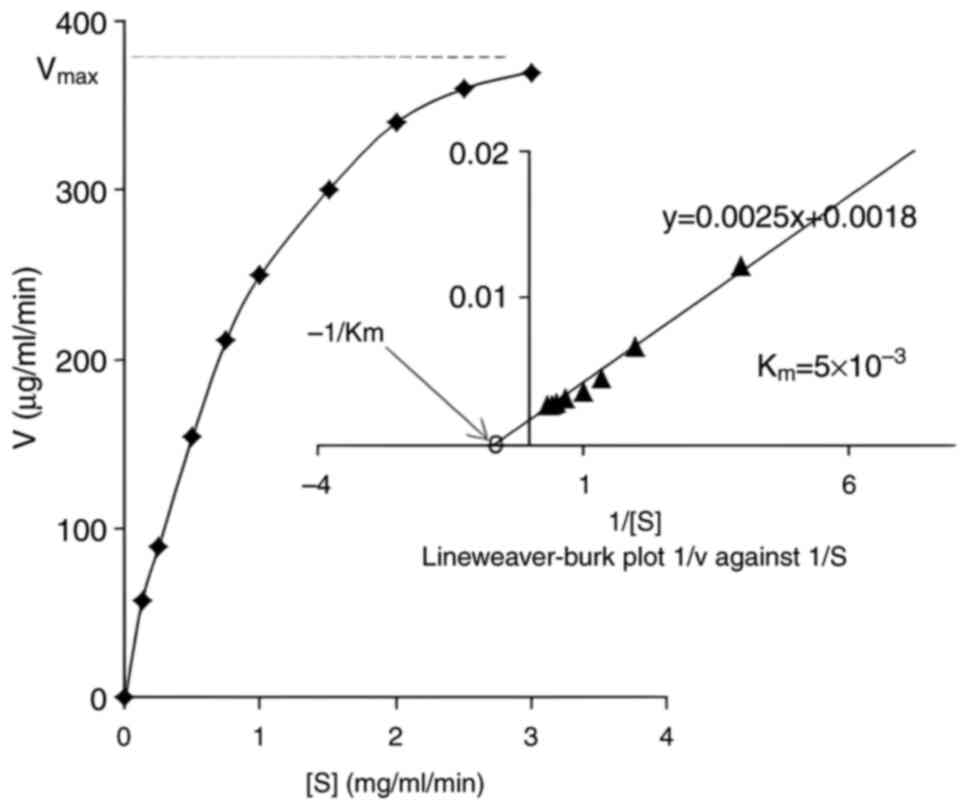

Kinetic parameters of Penicillium

purpurescens MCE

The Michaelis constant (Km) of the MCE

from Penicillium purpurescens was determined to be

5x10-2 M (Fig. 8),

indicating its moderate affinity for the substrate compared to

other fungal proteases. For instance, Aspergillus oryzae

produces a milk-clotting enzyme with a lower Km

(2.5x10-2 M), suggesting higher substrate affinity,

while Rhizomucor miehei exhibits a markedly lower

Km (3x10-3 M), reflecting superior catalytic

efficiency in cheese-making (37,44).

By contrast, Endothia parasitica has a higher Km

(12x10-1 M), indicating weaker substrate binding

(40). The Km value of

Penicillium purpurescens positions it as an intermediate

among fungal coagulants, potentially offering balanced proteolytic

activity for dairy applications.

In the authors' laboratory, the solid-state

fermentation process described herein demonstrated good

reproducibility, as repeated batches produced under identical

conditions consistently yielded comparable enzyme activity and

quantity. This reproducibility at the laboratory scale supports the

robustness of the optimized process. However, the scalability of

the method has not yet been assessed due to some limitations we

faced, including the lack of a pilot at the current time, a lack of

funds, and the absence of an experienced team to deal with a pilot

and its maintenance. Future research is required to focus on

pilot-scale trials to evaluate the feasibility of large-scale

enzyme production. Scaling up SSF may present challenges, including

maintaining uniform moisture distribution, temperature control and

adequate aeration in larger bioreactors, which need to be addressed

to ensure consistent enzyme quality and yield in industrial

applications (45).

Based on the results presented herein, the MCE from

Penicillium purpurescens produces high-quality cheese curds

with optimal characteristics, including curd yield, firmness and

sensory properties (Table V).

Further comparative studies are required to optimize its use in

industrial processes. Collectively, Penicillium purpurescens

demonstrates strong potential as a microbial rennet source, with

performance comparable to established fungal producers. Further

optimization and industrial-scale validation could enhance its

applicability in cheese manufacturing.

| Table VPhysicochemical and sensory

properties of curd formed by Penicillium purpurescens

milk-clotting enzyme. |

Table V

Physicochemical and sensory

properties of curd formed by Penicillium purpurescens

milk-clotting enzyme.

| Parameter | Observation |

|---|

| Curd yield (%) | 37% fresh

weight |

| Dry matter (%) | 45-50% |

| Firmness | High,

non-fragile, |

| Coagulation

time | 1-5 min |

| pH at

coagulation | 6.0-6.5 |

| Bitterness | None |

| Odor | Clean, milky |

| Syneresis | Low to

moderate |

The present study had certain limitations which

should be mentioned. The activity of the enzyme against α- and

β-casein fractions could not be assessed due to logistical

challenges beyond the authors' control, including delays in

chemical imports.

In conclusion, the present study highlights

Penicillium purpurescens as a highly promising fungal strain

for MCE production, demonstrating superior clotting efficiency

compared to other screened strains. Optimal MCE production was

achieved under SSF with wheat bran, near-neutral pH (6.0-6.5), and

moderate temperatures (50˚C), with fermentation kinetics peaking at

4-5 days. The enzyme exhibited enhanced activity at 1%

CaCs2, but declined at higher concentrations, suggesting

ionic strength sensitivity. Purification yielded fractions with

high specific activity (up to 320 U/mg), and the molecular weight

of the enzyme (29 kDa) and kinetic properties

(Km=5x10-2 M) position it as a competitive

alternative to commercial fungal rennets such as those and

Aspergillus oryzae. These findings underscore Penicillium

purpurescens as a viable candidate for industrial cheese

production, though further scale-up and stability studies are

needed to confirm its commercial applicability. Future research is

warranted.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

THA, LAM, EMA and DHEG performed the screened for

MCE in different strains, enzyme production form selected strain,

enzyme characterization, purification and biochemical enzyme

kinetics. SF performed the electrophoresis, and assisted in the

drafting of the manuscript. THA wrote the manuscript. THA and LAM

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liu X, Wu Y, Guan R, Jia G, Ma Y and Zhang

Y: Advances in research on calf rennet substitutes and their

effects on cheese quality. Food Res Int. 149(110704)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Shahryari Z and Niknezhad SV: Production

of industrial enzymes by filamentous fungi. In: Current

developments in biotechnology and bioengineering. Elsevier,

pp293-323, 2023.

|

|

3

|

Qasim F, Diercks-Horn S, Herlevi LM and

Fernandez-Lahore HM: Production of a fungal aspartic protease via

solid-state fermentation using a rotating drum bioreactor. J Chem

Technol Biotechnol. 100:273–285. 2025.

|

|

4

|

Claverie-MartÌn F and Vega-Hernàndez MC:

Aspartic proteases used in cheese making. In: Industrial Enzymes:

Structure, Function and Applications. Springer, pp207-219,

2007.

|

|

5

|

Li L, Zheng Z, Zhao X, Wu F, Zhang J and

Yang Z: Production, purification and characterization of a milk

clotting enzyme from Bacillus methanolicus LB-1. Food Sci

Biotechnol. 28:1107–1116. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

He D and Cui C: Fermentation of organic

wastes for feed protein production: Focus on agricultural residues

and industrial by-products tied to agriculture. Fermentation.

11(528)2025.

|

|

7

|

Kabir MF, Ovi AQ and Ju LK: Real-time pH

and temperature monitoring in solid-state fermentation reveals

culture physiology and optimizes enzyme harvesting for tailored

applications. Microb Cell Fact. 24(188)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hang F, Liu P, Wang Q, Han J, Wu Z, Gao C,

Liu Z, Zhang H and Chen W: High milk-clotting activity expressed by

the newly isolated Paenibacillus spp. Strain BD3526.

Molecules. 21(73)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Nicosia FD, Puglisi I, Pino A, Caggia C

and Randazzo CL: Plant milk-clotting enzymes for cheesemaking.

Foods. 11(871)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Benford D, Boobis A, Cantrill R, Cressey

P, Dessipri E, Kabadi SV, Jeurissen S, Mueller U and Barlow S:

Contributions of the joint FAO/WHO expert committee on food

additives to international food safety: Celebrating the 100th

meeting of the committee. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol.

160(105833)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hashem AM: Optimization of milk-clotting

enzyme productivity by Penicillium oxalicum. Biores Technol.

70:203–207. 1999.

|

|

12

|

Nema A, Patnala SH, Mandari V, Kota S and

Devarai SK: Production and optimization of lipase using

Aspergillus niger MTCC 872 by solid-state fermentation.

Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 43:1–8. 2019.

|

|

13

|

Vishwanatha KS, Appu Rao AG and Singh SA:

Production and characterization of a milk-clotting enzyme from

Aspergillus oryzae MTCC 5341. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol.

85:1849–1859. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kumar A, Grover S, Sharma J and Batish VK:

Chymosin and other milk coagulants: Sources and biotechnological

interventions. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 30:243–258. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Fan T, Wang J, Yuan W, Zhong Q, Shi Y and

Cong R: Purification and characterization of hatching enzyme from

brine shrimp Artemia salina. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin

(Shanghai). 42:165–171. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

El-Bendary MA, Moharam ME and Ali TH:

Purification and characterization of milk clotting enzyme produced

by Bacillus sphaericus. J Appl Sci Res. 3:695–699. 2007.

|

|

17

|

Laemmli UK: Cleavage of structural

proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4.

Nature. 227:680–685. 1970.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Snoek-van Beurden PA and Von den Hoff JW:

Zymographic techniques for the analysis of matrix

metalloproteinases and their inhibitors. Biotechniques. 38:73–83.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

He X, Yan YL, DeLaurier A and Postlethwait

JH: Observation of miRNA gene expression in zebrafish embryos by in

situ hybridization to microRNA primary transcripts. Zebrafish.

8:1–8. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lineweaver H and Burk D: The determination

of enzyme dissociation constants. J Am Chem Soc. 56:658–666.

1934.

|

|

21

|

Guleria S, Walia A, Chauhan A and Shirkot

CK: Optimization of milk-clotting enzyme production by Bacillus

amyloliquefaciens SP1 isolated from apple rhizosphere.

Bioresour Bioprocess. 3(30)2016.

|

|

22

|

Jacob M, Jaros D and Rohm H: Recent

advances in milk clotting enzymes. Int J Dairy Technol. 64:14–33.

2011.

|

|

23

|

Ahamed A, Singh A and Ward OP: Chymostatin

can combine with pepstatin to eliminate extracellular protease

activity in cultures of Aspergillus niger NRRL-3. J Ind

Microbiol Biotechnol. 34:165–169. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Shata HM: Extraction of milk-clotting

enzyme produced by solid state fermentation of Aspergillus

oryzae. Pol J Microbiol. 54:241–247. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Merheb-Dini C, Gomes E, Boscolo M and da

Silva R: Production and characterization of a milk-clotting

protease in the crude enzymatic extract from the newly isolated

Thermomucor indicae-seudaticae N31:(Milk-clotting protease

from the newly isolated Thermomucor indicae-seudaticae N31).

Food Chem. 120:87–93. 2010.

|

|

26

|

Qasim F, Diercks-Horn S, Gerlach D,

Schneider A and Fernandez-Lahore HM: Production of a novel

milk-clotting enzyme from solid-substrate Mucor spp. culture. J

Food Sci. 87:4348–4362. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kaya B, Wijayarathna ERKB, Yüceer YK,

Agnihotri S, Taherzadeh MJ and Sar T: The use of cheese whey powder

in the cultivation of protein-rich filamentous fungal biomass for

sustainable food production. Front Sustain Food Syst.

8(1386519)2024.

|

|

28

|

Balachandran C, Vishali A, Nagendran NA,

Baskar K, Hashem A and Abd Allah EF: Optimization of protease

production from Bacillus halodurans under solid state

fermentation using agrowastes. Saudi J Biol Sci. 28:4263–4269.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

El-Bendary MA, Moharam ME and Ali TH:

Efficient immobilization of milk clotting enzyme produced by

Bacillus sphaericus. Pol J Food Nutr Sci. 59:67–72.

2009.

|

|

30

|

Bensmail S, Mechakra A and Fazouane-Naimi

F: Optimization of milk-clotting protease production by a local

isolate of Aspergillus niger ffb1 in solid-state

fermentation. J Microbiol Biotech Food Sci. 4:467–472. 2015.

|

|

31

|

Yang J, Teplyakov A and Quail JW: Crystal

structure of the aspartic proteinase from Rhizomucor miehei

at 2.15 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 268:449–459. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Merheb-Dini C, Garcia GAC, Penna ALB,

Gomes E and Da Silva R: Use of a new milk-clotting protease from

Thermomucor indicae-seudaticae N31 as coagulant and changes

during ripening of Prato cheese. Food Chem. 130:859–865. 2012.

|

|

33

|

Krishna C and Nokes SE: Influence of

inoculum size on phytase production and growth in solid-state

fermentation by Aspergillus niger. Transactions of the ASAE.

44:1031–1036. 2001.

|

|

34

|

Hajji M, Rebai A, Gharsallah N and Nasri

M: Optimization of alkaline protease production by Aspergillus

clavatus ES1 in Mirabilis jalapa tuber powder using statistical

experimental design. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 79:915–923.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sun Q, Wang XP, Yan QJ, Chen W and Jiang

ZQ: Purification and characterization of a chymosin from

Rhizopus microsporus var. rhizopodiformis. Appl

Biochem Biotechnol. 174:174–185. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhang Y, Hu J, Wang J, Liu C, Liu X, Sun

J, Song X and Wu Y: Purification and characteristics of a novel

milk-clotting metalloprotease from Bacillus velezensis

DB219. J Dairy Sci. 106:6688–6700. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Preetha S and Boopathy R: Purification and

characterization of a milk clotting protease from Rhizomucor

miehei. World J Microb Biotechnol. 13:573–578. 1997.

|

|

38

|

Duan Y, Katrolia P, Zhong A and Kopparapu

NK: Production, purification and characterization of a novel

antithrombotic and anticoagulant serine protease from food grade

microorganism Neurospora crassa. Prep Biochem Biotechnol.

52:1008–1018. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Takyu Y, Asamura T, Okamoto A, Maeda H,

Takeuchi M, Kusumoto KI, Katase T, Ishida H, Tanaka M and Yamagata

Y: A novel milk-clotting enzyme from Aspergillus oryzae and

A. luchuensis is an aspartic endopeptidase PepE presumed to

be a vacuolar enzyme. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 86:413–422.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Hagemeyer K, Fawwal I and Whitaker JR:

Purification of protease from the Fungus Endothia

parasitica. J Dairy Sci. 51:1916–1922. 1968.

|

|

41

|

Arima K, Yu J, Iwasaki S and Tamura G:

Milk-clotting enzyme from microorganisms: V. Purification and

crystallization of Mucor rennin from Mucor pusillus

var. Lindt. Appl Microbiol. 16:1727–1733. 1968.

|

|

42

|

Nájera AI, De Renobales M and Barron LJR:

Effects of pH, temperature, CaCl2 and enzyme concentrations on the

rennet-clotting properties of milk: A multifactorial study. Food

Chem. 80:345–352. 2003.

|

|

43

|

Wang X, Kang Y, Gao L, Zhao Y, Gao Y, Yang

G and Li S: The effect of salt reduction on the microbial community

structure and metabolite composition of cheddar cheese. Foods.

13(4184)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Mane A and McSweeney PLH: Proteolysis in

Irish farmhouse Camembert cheese during ripening. J Food Biochem.

44(e13101)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wang Y, Aziz T, Hu G, Liu J, Min Z,

Zhennai Y, Alharbi M, Alshammari A and Alasmari AF: Production,

purification, and characterization of a novel milk-clotting

metalloproteinase produced by Bacillus velezensis YH-1

isolated from traditional Jiuqu. LWT. 184(115080)2023.

|

|

46

|

Mamo A and Balasubramanian N: Calf rennet

production and its performance optimization. J Appl Nat Sci.

10:247–252. 2018.

|

![Elution profile of milk-clotting

enzyme from Penicillium purpurescens purified by acetone

fractionation, then DEAE-cellulose ion-exchange chromatography.

Protein content was monitored at 280 nm, and milk-clotting activity

was assayed in collected fractions. Active MCE fractions were

observed at (NaCl concentration range] 0.05 to 0.1 mM), indicating

successful separation from non-active proteins.](/article_images/wasj/7/6/wasj-07-06-00399-g06.jpg)