Introduction

Pompe disease (PD), also known as type II glycogen

storage disease, is a neuromuscular disease resulting from acid

alpha glucosidase (GAA) gene mutations located on chromosome

17q25. This gene encodes the enzyme GAA, which is responsible for

the breakdown of glycogen in lysosomes (1). The most commonly used classification

of PD is based on the age of onset and the disease severity, which

are associated with the residual activity of the enzyme. Minimal to

absent GAA activity results in the early manifestation of the

disease within the first few months of life; this early

manifestation of the disease has been termed infantile-onset PD

(IOPD). Children often present with hypotonia, muscle weakness,

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and eventually, cardiorespiratory

failure if left untreated. In late-onset PD, the cardiac muscle is

usually spared, while skeletal muscle function progressively

deteriorates from limb-girdle weakness to respiratory insufficiency

(2).

Although enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) has

markedly improved the survival rate of patients, its impact on

long-term functional outcomes and quality of life remains limited.

Studies have demonstrated that despite the early initiation of ERT,

a number of children continue to experience marked gross motor

delays, feeding difficulties and dependency on caregivers for daily

activities (2-6).

These persistent challenges highlight the gap between clinical

stabilization and real-world functional recovery. The present study

therefore aimed to assess the developmental delay, nutritional

intake and the caregiving burden among children with PD receiving

long-term ERT, in order to better understand the residual impact of

IOPD on daily life and identify areas where supportive care remains

essential.

Patients and methods

Study design

The present single-center cross-sectional study was

conducted at the Endocrinology, Genetics, Metabolism and Molecular

Therapy Center of the Vietnam National Children's Hospital, Hanoi,

Vietnam from November, 2021 to August, 2022.

Study subjects

Children diagnosed with PD at the Vietnam National

Children's Hospital were enrolled based on the diagnostic criteria

outlined in the 2006 guideline by the American College of Medical

Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Work Group on Management of Pompe

Disease (2).

Measurement of outcomes

Anthropometric measurements including weight and

length/height were obtained using standardized methods and

classified using the World Health Organization (WHO) growth

standards (7,8). Nutrient intake was assessed via 24-h

dietary recalls collected through caregiver interviews by a single

nutritionist doctor.

School attendance and caregiving difficulties were

evaluated using a structured caregiver questionnaire. Gross motor

age was defined as the age corresponding to the furthest milestone

based on the Denver Development Screening Test (9) successfully achieved by the child, at

which 50% of age-matched peers are expected to have attained that

skill. Gross motor delay was calculated by the difference between

the gross motor age and the chronological age.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata 15.0 software

(StataCorp LLC). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize

demographic and outcome variables. Associations between variables

were evaluated using linear regression for continuous outcomes, of

which the dependent variable was the delay of the gross motor

function based on the Denver Development Screening Test. The

independent variables were the duration of the disease, the protein

intake, the sex and the body mass index-for-age z-score. A P-value

<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

During the study period, 34 children with PD aged

from 1-82 months (mean age, 32.8±23.1 months; of which 55.9% were

male) were recruited. All patients had IOPD, and 33/34 patients

(97.1%) had cardiac involvements (Table I). All patients received regular

biweekly ERT, except during the Lunar New Year holiday and COVID-19

lockdown periods, when infusions were administered monthly. The

cost of the enzyme was covered by pharmaceutical companies, while

hospital bed charges and medical consumables were reimbursed by the

national health insurance. The families of the patient were

responsible for travel-related expenses, including transportation

and meals.

| Table ICharacteristics of the study

participants. |

Table I

Characteristics of the study

participants.

| Demographic

characteristics | |

|---|

| Age (months), mean ±

SD | 32.76±23.1 |

|

Infant and

young children (≤3 years), n (%) | 19 (55.9%) |

|

Preschool

(>3 to <6 years), n (%) | 13 (38.2%) |

|

School-aged

(from 6 years), n (%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

|

Male | 19 (55.9%) |

|

Female | 15 (44.1%) |

| School attendance

rate, n (%) | |

|

Preschool

(>3 to <6 years) | 2 (15.4%) |

|

School-aged

(from 6 years) | 1 (50%) |

| Clinical

characteristics | |

| Clinical subtypes, n

(%) | |

|

Classical

IOPD | 33 (97.1%) |

|

Modified

IOPD | 1 (2.9%) |

| CK (IU/l), mean ±

SD | 1451.56±897.02 |

| AST (IU/l), mean ±

SD | 356.25±192.8 |

| ALT (IU/l) (mean ±

SD) | 183.76±78.57 |

| GAA activity essay

using acarbose (mean ± SD) | 93.4±2.4 |

| CRIM status, n

(%)a | |

|

Positive | 34 (100%) |

|

Negative | 0 |

| Disease duration

(months), mean ± SD | 27.4±20.5 |

Dietary intake analysis revealed that the median

energy intake among the participants was 101.5% of the recommended

value [interquartile range (IQR), 85.9-120.7%]. Of note, 29.4%

(10/34) of children consumed <90% of their requirements, while

41.2% (14/34) exceeded 110% (Table

II).

| Table IIAdequacy of nutrient intake amongst

children with IOPD. |

Table II

Adequacy of nutrient intake amongst

children with IOPD.

| Nutrient | Measure of central

tendency | % Below

recommendation | % Above

recommendation | P-value |

|---|

| Energy

adequacya | Median 101.5% (IQR,

85.9-120.7) | 29.4% (<90% of

EER) | 41.2% (>110% of

EER) | 0.0082 |

| Protein

intakeb | Median 3.5 g/kg/day

(IQR, 1.8-4.7) | 82.4% (<90% of

RNI) | 17.6% (>120% of

RNI) | <0.001 |

| Fiber

intakec | Mean 2.1±1.8 g/1,000

kcal | 100% (<14 g/1,000

kcal) | 0% | <0.001 |

Protein intake was insufficient in the majority of

patients, with a median intake of 3.5 g/kg/day (IQR, 1.8-4.7

g/kg/day). A total of 82.4% (28/34) of children consumed <90% of

their estimated needs, while 17.6% (6/34) consumed >120%

Table II). Fiber intake was low

across all participants, with a mean intake of 2.1±1.8 g/1,000

kcal. None of the children met the threshold of 14 g/1,000 kcal, as

recommended for an adequate fiber intake (Table II).

As regards food acceptance, 38.2% of the children

exhibited ‘picky’ eating behaviors related to texture or food

pieces. Among those aged >24 months, 66.7% still required food

to be blended or pureed. As regards supplementation, 55.9% (19/34)

were supplemented with vitamin D, with 78.9% of them receiving

>400 IU per day. Among the children aged >3 years, 60% (9/15)

used formula, of which 55.6% (5/9) were consuming growing-up

formula, while the remainder were consuming standard follow-up

formula.

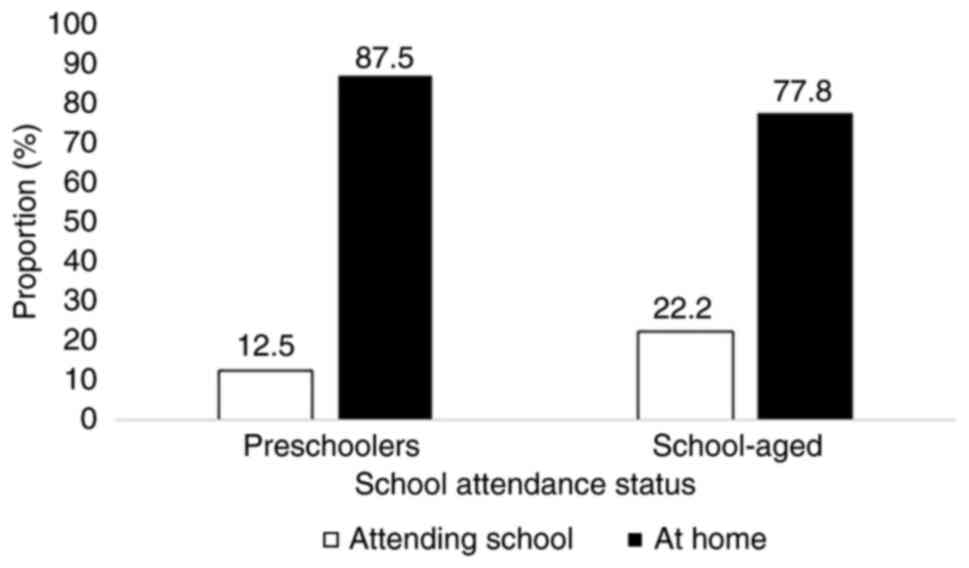

In terms of daily functioning, the majority of

children remained at home. Among the infants and toddlers, 15 of 17

were home-based, while 2 children remained hospitalized. Out of the

preschoolers, 87.5% stayed at home, and only 1 child attended

kindergarten. Similarly, 77.8% of the school-aged children were not

attending school (Fig. 1).

The reasons for home care among the preschoolers and

school-aged children (82.4% collectively) included prolonged

mealtimes and special feeding (blended foods) requirements (58.8%),

non-ambulatory status (17.6%), and, in one case, challenges

involving 2 affected children in one household. The majority of

families (85.3%) had a full-time at-home caregiver, typically a

parent (93.1%). Gross motor ages were delayed by 22.5±20.5 months.

Amongst the preschoolers and school-age children (>3 years of

age), 82.4% were able to stand alone.

In the bivariate analysis, disease duration was

found to be significantly associated with gross motor delay

(adjusted r2=0.89, P<0.001), while there was no

statistically significant association between the protein intake

and the gross motor delay (r2=-0.0244, P=0.6472)

(Table III).

| Table IIIAssociation of factors with gross

motor delay. |

Table III

Association of factors with gross

motor delay.

| Associating

factors | β-coefficient | r2

value | P-value |

|---|

| Protein intake

(g/kg/day) | 0.78 | -0.0244 | 0.6472 |

| Disease duration

(months) | 0.83 | 0.8788 | <0.001 |

Discussion

The present study cohort exclusively comprised

children with IOPD, which is the most severe phenotype, with almost

all children presenting with cardiac involvement.

Dietary intakes and nutrition

practices in children with IOPD

Energy-wise, intake varied widely, with almost a

third of the children under-consuming and >40% exceeding

recommendations. This variability may reflect the challenges in

tailoring nutrition plans to individual clinical conditions, such

as varying degrees of disease progression, immobility, feeding

difficulties and metabolic demands. This was in accordance with the

recommendations of regular nutritional assessment along the disease

progression and individualized nutritional interventions (10-12).

Notably, >80% of children with IOPD in this

cohort consumed <90% of their estimated protein needs. On the

other hand, all participants failed to meet the fiber intake

threshold of 14 g/1,000 kcal. These findings may be explained by

the predominance of low-density liquid foods, such as formulas,

purees and restricted diets. In fact, a notable proportion of

children exhibited food refusal or required texture modification

beyond toddler age. Systematic supplementation and the prolonged

use of formula (to the extent of the high-energy growing formula)

were current strategies to prevent micronutrient deficiencies.

However, more global approaches including macronutrient

considerations (e.g. protein and energy requirements), food texture

sensitization in addition to oral motor function rehabilitation and

orthodontic treatments may prove to be beneficial (13) and should be considered.

Gross motor delay, limited

participation in school and care burden

In the present study cohort, 82.4% of the

preschoolers and school-aged children (aged >3 years) were able

to walk independently. This proportion is higher than that observed

in some previous studies (25-64%) (14-16),

which may be due to the fact that the participants in the present

study were younger (mean age, 32.8±23.1 months) and had a shorter

disease duration. Furthermore, 100% of the patients in the present

study were CRIM-positive, which is typically associated with a

better response to ERT. In a German-Austrian cohort, in which 86.7%

of the patients were CRIM-positive, the independent ambulation

status declined in the 7-year follow-up from 46.7% (median age of 2

years) to 33.3% (median age of 9.1 years) (16). In another study, in a UK

multicenter population, the mean ERT duration was 13 years 9 months

and the CRIM-positive rate was 55%; in that study, 30% of patients

achieved independent ambulation (17).

Of note, a significant proportion (17.2%) of the

present study subgroup (>3 years of age) with a median ERT

duration of 40.5 months remained non-ambulant, suggesting that ERT

alone may not be sufficient to prevent long-term motor

deterioration. This highlights the need for early intervention and

additional therapeutic strategies beyond ERT in order to improve

motor outcomes and preserve function over time.

The present study also demonstrated that the care

burden on families was considerable, with 85.3% of households

having a full-time at-home caregiver, most often a parent. This

reflects the substantial demands of daily care, including prolonged

mealtimes, specialized feeding practices and physical assistance

due to limited mobility. Similar findings have been reported in

previous studies, where caregivers of children with IOPD experience

high levels of emotional, physical and financial stress (18,19).

The requirement for continuous care may limit parental employment

and social participation, underscoring the need for structured

psychosocial support and access to community-based services.

The present study has certain limitations, which

should be mentioned. The present study was limited by the

cross-sectional design, small sample size and reliance on

caregiver-reported intake, which may be subject to recall bias.

Moreover, the cross-sectional design cannot infer causal

associations; therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes

and a longitudinal design are warranted. Nonetheless, the present

study provides valuable insight into the real-world challenges of

managing nutrition and development in children with IOPD.

In conclusion, children with IOPD face significant

nutritional and motor challenges despite ERT. Suboptimal protein

and fiber intake, along with high variabilities in energy needs,

highlight the importance of tailored nutritional care. Although the

ambulation rates in the present study cohort were higher than those

in other studies, motor delays remain common, reinforcing the need

for early and multidisciplinary interventions. The high caregiving

burden further emphasizes the need for broader family support.

Acknowledgements

The authors are also grateful to the medical and

administrative staff at Vietnam National Children's Hospital

(Hanoi, Vietnam) for their instutional support.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are not

publicly available due to ethical restrictions, but may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TMTL conceptualized and designed the study,

collected and analyzed the data, performed a literature search,

interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. ATP was

responsible for dietary recalls, anthropometric measurements,

nutritional interventions and was also involved in drafting the

manuscript. CDV was responsible for clinical examinations,

interpreted the results and performed a literature search. PNT

interpreted the imaging results (interpretation of chest X-rays to

assess cardiomegaly), and performed the literature search. TTHN

contributed to the nutritional interventions, patient management,

was involved in drafting the manuscript. NKN conducted the clinical

examinations, and critically revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. TMTL and ATP confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Vietnam National Children's Hospital, Hanoi,

Vietnam (2176-BVNTW-HĐĐĐ). Written informed consent was obtained

from the caregivers of all participants prior to enrollment.

Participation was entirely voluntary, and caregivers were informed

that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any

impact on the patient's care. All collected data were anonymized

and used exclusively for research purposes.

Patients consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, the authors did

use artificial intelligence assisted tools in order to improve the

readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool

service, the authors did review and edit the content as needed,

taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

|

1

|

Hers HG: alpha-Glucosidase deficiency in

generalized glycogenstorage disease (Pompe's disease). Biochem J.

86:11–16. 1963.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kishnani PS, Steiner RD, Bali D, Berger K,

Byrne BJ, Case LE, Crowley JF, Downs S, Howell RR, Kravitz RM, et

al: Pompe disease diagnosis and management guideline. Genet Med.

8:267–288. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Kishnani PS, Corzo D, Leslie ND, Gruskin

D, Van der Ploeg A, Clancy JP, Parini R, Morin G, Beck M, Bauer MS,

et al: Early treatment with alglucosidase alpha prolongs long-term

survival of infants with Pompe disease. Pediatr Res. 66:329–335.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Chakrapani A, Vellodi A, Robinson P, Jones

S and Wraith JE: Treatment of infantile Pompe disease with

alglucosidase alpha: The UK experience. J Inherit Metab Dis.

33:747–750. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hahn A, Praetorius S, Karabul N, Dießel J,

Schmidt D, Motz R, Haase C, Baethmann M, Hennermann JB, Smitka M,

et al: Outcome of patients with classical infantile pompe disease

receiving enzyme replacement therapy in Germany. In: JIMD Reports.

Volume 20. Zschocke J, Baumgartner M, Morava E, Patterson M, Rahman

S and Peters V (eds). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp65-75,

2015.

|

|

6

|

Hahn A and Schänzer A: Long-term outcome

and unmet needs in infantile-onset Pompe disease. Ann Transl Med.

7(283)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

World Health Organization (WHO): WHO child

growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age,

weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age:

Methods and development. World Health Organization, 2006.

|

|

8

|

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A,

Nishida C and Siekmann J: Development of a WHO growth reference for

school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ.

85:660–667. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Frankenburg WK, Dodds J, Archer P, Shapiro

H and Bresnick B: The denver II: A major revision and

restandardization of the denver developmental screening test.

Pediatrics. 89:91–97. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fatehi F, Ashrafi MR, Babaee M, Ansari B,

Beiraghi Toosi M, Boostani R, Eshraghi P, Fakharian A, Hadipour Z,

Haghi Ashtiani B, et al: Recommendations for infantile-onset and

late-onset pompe disease: An Iranian consensus. Front Neurol.

12(739931)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Llerena Junior JC, Nascimento OJ, Oliveira

ASB, Dourado Junior ME, Marrone CD, Siqueira HH, Sobreira CF,

Dias-Tosta E and Werneck LC: Guidelines for the diagnosis,

treatment and clinical monitoring of patients with juvenile and

adult Pompe disease. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 74:166–176.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tarnopolsky MA and Nilsson MI: Nutrition

and exercise in Pompe disease. Ann Transl Med.

7(282)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Galeotti A, De Rosa S, Uomo R,

Dionisi-Vici C, Deodato F, Taurisano R, Olivieri G and Festa P:

Orofacial features and pediatric dentistry in the long-term

management of infantile Pompe disease children. Orphanet J Rare

Dis. 15(329)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Prater SN, Banugaria SG, DeArmey SM, Botha

EG, Stege EM, Case LE, Jones HN, Phornphutkul C, Wang RY, Young SP

and Kishnani PS: The emerging phenotype of long-term survivors with

infantile Pompe disease. Genet Med. 14:800–810. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Parini R, De Lorenzo P, Dardis A, Burlina

A, Cassio A, Cavarzere P, Concolino D, Della Casa R, Deodato F,

Donati MA, et al: Long term clinical history of an Italian cohort

of infantile onset Pompe disease treated with enzyme replacement

therapy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 13(32)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Pfrimmer C, Smitka M, Muschol N, Husain

RA, Huemer M, Hennermann JB, Schuler R and Hahn A: Long-term

outcome of infantile onset pompe disease patients treated with

enzyme replacement therapy-data from a german-austrian cohort. J

Neuromuscul Dis. 11:167–177. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Broomfield A, Fletcher J, Davison J,

Finnegan N, Fenton M, Chikermane A, Beesley C, Harvey K, Cullen E,

Stewart C, et al: Response of 33 UK patients with infantile-onset

Pompe disease to enzyme replacement therapy. J Inherit Metab Dis.

39:261–271. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Benedetto L, Musumeci O, Giordano A,

Porcino M and Ingrassia M: Assessment of parental needs and quality

of life in children with a rare neuromuscular disease (Pompe

disease): A quantitative-qualitative study. Behav Sci (Basel).

13(956)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Schoser B, Bilder DA, Dimmock D, Gupta D,

James ES and Prasad S: The humanistic burden of Pompe disease: are

there still unmet needs? A systematic review. BMC Neurol.

17(202)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|