Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a

Gram-negative bacteria that normally inhabits the human stomach

(1). It is known that H.

pylori augments the risk of developing gastric diseases, such

as gastric ulcers, gastric cancers and gastric mucosa-assisted

lymphoid tissue lymphoma by infecting the gastric mucosa epithelial

cells (2). It has been reported

that approximately half of the population worldwide is infected

with H. pylori, with a particularly high prevalence rate in

African regions (3). The

prevalence rate of H. pylori is 30-40% in developed

countries and ≥80% in developing countries, suggesting that

socioeconomic conditions are markedly associated with H.

pylori infection (4). H.

pylori infection occurs during childhood via oral transmission

as an asymptomatic infection (5).

It may be challenging to demonstrate the

colonization of H. pylori in the oral cavity (6). It has been reported that H.

pylori DNA can be detected in inflamed dental pulp and

subgingival dental plaque in the oral cavity, as well as in the

gastric mucosa (6-8).

A recent meta-analysis revealed that gastric H. pylori

infection is more frequently found in patients with current oral

H. pylori infection than in patients without oral H.

pylori infection (9).

Additionally, it has been reported that treatment for oral H.

pylori infection is effective for the successful eradication of

gastric H. pylori (10),

indicating that there is a significant relationship between oral

H. pylori and gastric H. pylori infection. Therefore,

the oral cavity may be an important reservoir for gastric H.

pylori. It is speculated that poor oral hygiene and periodontal

inflammation may be linked to the prevalence of oral H.

pylori and gastric H. pylori infection. However, the

association between the prevalence of oral H. pylori and

oral health has not yet been fully investigated in Japanese older

adults. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate

the association between the presence of oral H. pylori DNA

and dental hygiene condition in older adults.

Patients and methods

Study participants

The present study targeted patients aged ≥65 years

who visited the Oral Health Department at Hiroshima University

Hospital from April, 2021 to February, 2023. Patients with

immunodeficiency (i.e., post-operative inpatients, cancer patients

receiving chemotherapy and patients with immune deficiency

disorders) were excluded (n=0). Finally, 98 older patients (28

males, 70 females; median age, 75 years; range, 65-91 years) were

included in the present study. The present cross-sectional study

was a part of a general research project on the association between

oral microbiome and oral health approved by the Ethics Committee of

Hiroshima University (Approval no. E-1115). Patients who agreed to

participate in this study signed an informed consent form. Clinical

variables (i.e., participants' age, gender, lifestyle-related

diseases, number of remaining teeth and denture use) were obtained

from medical records of the participants. Periodontal pocket depth

and bleeding on probing (BOP) were investigated at six sites

(mesio-buccal, mid-buccal, disto-buccal, disto-lingual, mid-lingual

and mesio-lingual sites) for each tooth. The accumulation of dental

plaque was evaluated using a modified O'Leary Plaque Control Record

by assessing six surfaces (mesio-buccal, mid-buccal, disto-buccal,

disto-lingual, mid-lingual and mesio-lingual surfaces) of each

tooth, as previously described (11).

Oral sample collection method and DNA

extraction

Swab samples were collected from the tongue surface

using a sterile disposable Orcellex® Brush (Rovers

Medical Devices). After the collected samples were dissolved in

cell lysis buffer, DNA was extracted and purified using a PureLink™

Microbiome DNA Purification kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific Inc.) in accordance with the manufacturer's

instructions.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(qPCR)

qPCR was performed in the Thermal Cycler

Dice® Real Time System III (Takara Bio, Inc.) using

THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd.). The amplification

cycle consisted of 95˚C for 2 min, followed by 50 cycles of 95˚C

for 1 min, 55˚C for 1 min and 72˚C for 1 min, and 72˚C for 2 min. A

primer pair targeting the H. pylori ureA gene was used in

the present study, as it has high specificity for detecting H.

pylori DNA, as described in a previous study (8). The sequence of primers for H.

pylori was as follows: forward, 5'-ATGAAACTCACCCCAAAAGA-3' and

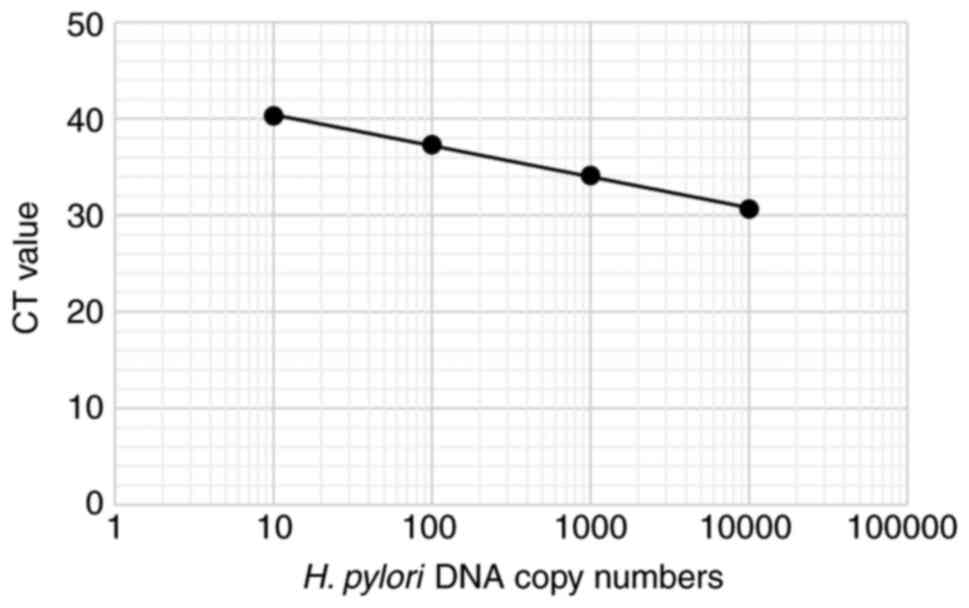

reverse, 5'-TTCACTTCAAAGAAATGGAAGTGTGA-3' (8). A standard curve for H. pylori

was generated using 10-fold serially diluted samples of the

AMPLIRUN® HELICOBACTER PYLORI DNA CONTROL (10,000-20,000

H. pylori DNA copies/µl; Vircell) (Fig. 1). A no-template control was used as

the negative control in qPCR analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS

software, version 24.0 (IBM Corp.). Logistic regression analysis

was performed to examine the association between H. pylori

as a dependent variable and clinical variables as independent

variables. Clinical parameters with a P-value of <0.2 through

univariate analysis were used as independent variables for logistic

regression analysis. Continuous variables are expressed as the

median and interquartile range (IQR). P-values <0.05 were

considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Association between oral H. pylori and

clinical variables

The association between the presence of oral H.

pylori DNA and clinical variables is presented in Table I. Among the 98 participants, 7

participants (7.1%) were positive for oral H. pylori DNA.

Participants in their 70s exhibited a greater positive rate of oral

H. pylori DNA (12.5%) than the other age groups.

Additionally, female participants exhibited a higher positive rate

of oral H. pylori DNA (8.6%) than male participants (3.6%).

There was no significant association between the presence of oral

H. pylori DNA and clinical variables such as age, sex,

lifestyle-related diseases, number of remaining teeth, or denture

use.

| Table IClinical characteristics of the study

participants and their association with the presence of oral H.

pylori DNA. |

Table I

Clinical characteristics of the study

participants and their association with the presence of oral H.

pylori DNA.

| Clinical variables

(n) | H.

pylori-negative (n=91) | H.

pylori-positive (n=7) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, median

(IQR) | 75 (11.0) | 75 (5.0) | 0.86a |

| Age group, n

(%) | | | |

|

65-69 | 20 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 0.3b |

|

70-79 | 42 (46.2%) | 6 (85.7%) | |

|

80-89 | 27 (29.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | |

|

90-99 | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Sex, n (%) | | | |

|

Male | 27 (29.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0.67b |

|

Female | 64 (70.3%) | 6 (85.7%) | |

| Hypertension, n

(%) | | | |

|

Yes | 22 (24.2%) | 3 (42.9%) | 0.37b |

|

No | 69 (75.8%) | 4 (57.1%) | |

| Diabetes, n

(%) | | | |

|

Yes | 14 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.59b |

|

No | 77 (84.6%) | 7 (100%) | |

| Dyslipidemia, n

(%) | | | |

|

Yes | 20 (22%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0.65b |

|

No | 71 (78%) | 5 (71.4%) | |

| Number of remaining

teeth, median (IQR) | 24 (7.0) | 27 (8.0) | 0.27a |

| Denture user, n

(%) | | | |

|

Yes | 43 (47.3 %) | 2 (28.6%) | 0.45b |

|

No | 48 (52.7%) | 5 (71.4%) | |

Association between oral H. pylori and

the oral health condition

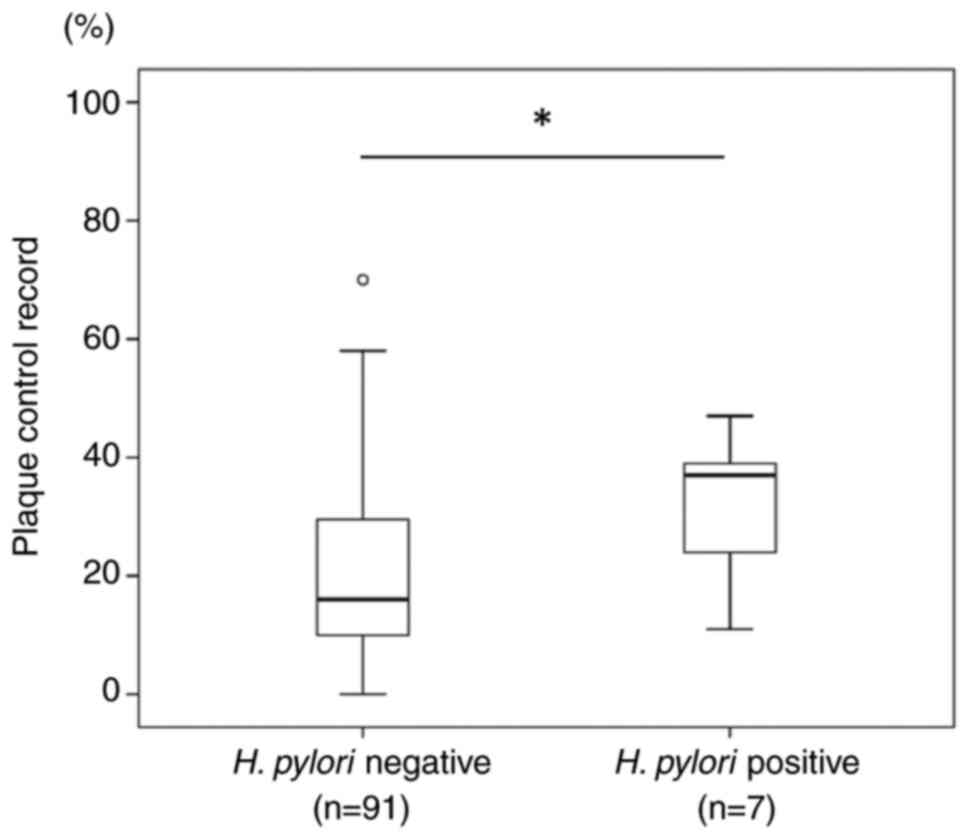

The participants who were positive for oral H.

pylori exhibited higher median plaque control record scores

(37%) than those who were negative for oral H. pylori (16%)

(Fig. 2). A significant difference

in plaque control record scores was found between the oral H.

pylori-negative and -positive participants (P=0.04). As regards

the association between oral H. pylori and clinical

periodontal conditions, the oral H. pylori-positive

participants exhibited a higher rate of ≥4 mm deep periodontal

pockets with BOP (85.7%) than the participants who were negative

for oral H. pylori (49.5%) (Table II). Additionally, the oral H.

pylori-positive participants exhibited a higher rate of ≥6 mm

deep periodontal pockets with BOP (28.6%) than the participants who

were negative (15.4%) (Table II).

However, no significant association between oral H. pylori

and deep periodontal pockets with BOP was found. These results

indicate that oral H. pylori-positive participants may have

poorer dental hygiene than oral H. pylori-negative

participants.

| Table IIPeriodontal condition of the study

participants and its association with the presence of oral H.

pylori DNA. |

Table II

Periodontal condition of the study

participants and its association with the presence of oral H.

pylori DNA.

| Clinical

periodontal variables | H.

pylori-negative (n=91) | H.

pylori-positive (n=7) | P-value |

|---|

| Probing pocket

depth, n (%) | | | |

|

<4

mm | 18 (19.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.6a |

|

≥4 mm and

<6 mm | 44 (48.4%) | 4 (57.1%) | |

|

≥6 mm | 29 (31.9%) | 3 (42.9%) | |

| BOP (%) (IQR) | 5.0 (10.0) | 3.0 (12.0) | 0.78b |

| ≥4 mm periodontal

pocket with BOP, n (%) | | | |

|

Yes | 45 (49.5%) | 6 (85.7%) | 0.11a |

|

No | 46 (50.5%) | 1 (14.3%) | |

| ≥6 mm periodontal

pocket with BOP, n (%) | | | |

|

Yes | 14 (15.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0.32a |

|

No | 77 (84.6%) | 5 (71.4%) | |

Logistic regression analysis with oral

H. pylori as the dependent variable

Logistic regression analysis was conducted as

independent variables in univariate analysis (i.e., variables with

a P-value <0.2) and with oral H. pylori as the dependent

variable. The results of logistic regression analysis are presented

in Table III. There was no

significant association between oral H. pylori and ≥4 mm

deep periodontal pockets with BOP or plaque control record

score.

| Table IIILogistic regression analysis with

oral H. pylori as the dependent variable. |

Table III

Logistic regression analysis with

oral H. pylori as the dependent variable.

| Clinical

variables | Odds ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| ≥4 mm periodontal

pocket with BOP | 5.92 | 0.66-53.2 | 0.11 |

| Plaque control

record | 1.05 | 0.99-1.1 | 0.08 |

Correlation between oral H. pylori DNA

copy numbers and plaque control record scores

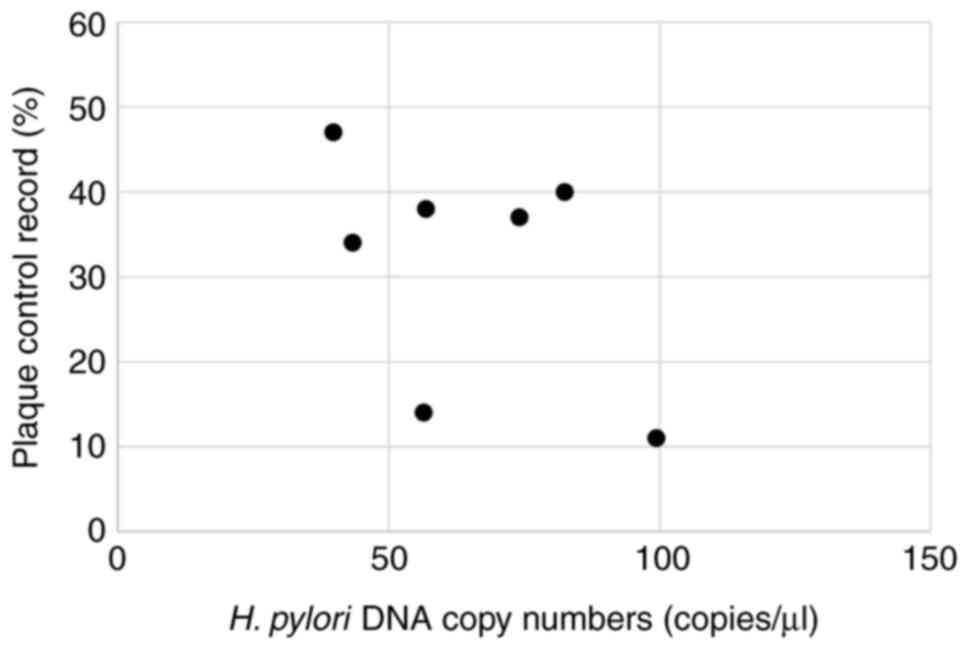

The present study then calculated the H.

pylori copy numbers per each 1 µl DNA sample from the

participants who were positive for oral H. pylori. The

median H. pylori copy number was 56.8 (IQR, 39.2) copies/µl.

The scatter plot illustrates correlation between oral H.

pylori DNA copy numbers and plaque control record scores

(Fig. 3). There was no significant

correlation between the oral H. pylori copy numbers and

plaque control record scores, as demonstrated in Table IV.

| Table IVCorrelation between oral H.

pylori DNA copy numbers and plaque control record scores. |

Table IV

Correlation between oral H.

pylori DNA copy numbers and plaque control record scores.

| | Oral H.

pylori DNA copy numbers |

|---|

| Variables | Spearman's rank

correlation coefficient | P-value |

|---|

| Plaque control

record scores | -0.36 | 0.43 |

Discussion

The prevalence rate of oral H. pylori

infection varies widely from 1 to 87% in the population, including

among children, young, middle-aged and older individuals, as

previously reported since 2016 (7,12-21).

The majority of studies investigated the positive rate of oral

H. pylori DNA using PCR. Oral samples included dental

plaque, dental pulp, saliva and swabs from the tongue dorsum. It is

speculated that variation in the age and regional characteristics

of the participants, and sample collection method may have affected

the positive rate of oral H. pylori. Additionally,

periodontal inflammation may be implicated in the high prevalence

rate of oral H. pylori as oral H. pylori was more

frequently detected in individuals with periodontitis than in those

without periodontitis (22,23).

Furthermore, the detection sensitivity of PCR and the specificity

of PCR primers may have varied in each study.

It is considered that the chronic inflammation of

periodontal tissues is involved in persistent infection with oral

H. pylori. In the present study, the oral H.

pylori-positive participants exhibited a higher percentage of

≥4 mm periodontal pockets with BOP than the oral H.

pylori-negative participants. However, there was no significant

association between oral H. pylori and deep periodontal

pockets with BOP (i.e., active periodontitis). A number of

participants had mild periodontal inflammation as the participants

regularly received supportive periodontal therapy. Therefore,

relatively mild periodontal inflammation may have been associated

with a low positive rate of oral H. pylori in the present

study. Therefore, additional studies are required to clarify the

association between oral H. pylori and moderate to severe

periodontitis.

Previous studies have reported that oral H.

pylori can be detected in subgingival dental plaque (14,19,21).

Thus, H. pylori, a component of the subgingival microbiome,

may play a pathogenic role in the periodontium, as well as a

carcinogenic role in the stomach. However, the biological

mechanisms by which H. pylori is involved in periodontal

inflammation have not yet been elucidated. H. pylori

contributes to the induction of inflammatory cytokines, such as

IL-17, which can facilitate chronic periodontal inflammation

(24,25). Porphyromonas gingivalis

(P. gingivalis), a Gram-negative oral anaerobe, is a major

periodontopathic bacteria (26).

P. gingivalis was detected in the oral cavity of ~50% of

middle-aged and older Japanese adults (27). P. gingivalis was more

frequently found in H. pylori-positive dental plaque than in

H. pylori-negative dental plaque (18). These results indicate that H.

pylori may be involved in the acceleration of periodontal

inflammation by inducing inflammatory cytokines. However, the

potential role of H. pylori in periodontitis has not yet

been elucidated. Additionally, it remains unclear whether H.

pylori enhances cytokine induction in cooperation with P.

gingivalis in periodontal tissues.

In the present study, the level of dental plaque

accumulation was significantly higher in the oral H.

pylori-positive participants than in the oral H.

pylori-negative participants, suggesting that participants with

oral H. pylori exhibit poor oral hygiene. Additionally,

H. pylori may be detected more abundantly in dental plaque

than on the tongue dorsum. Although the present study did not find

a significant association between oral H. pylori DNA and

plaque control record score in the logistic regression analysis, a

significant association may be found using a larger study

population with dental plaque sampling. These findings highlight

the importance of daily oral hygiene practice and regular

professional oral care to prevent oral H. pylori infection

in older adults. However, the detection of oral H. pylori

DNA is not necessarily associated with H. pylori

colonization (i.e., active H. pylori infection) in the oral

cavity. Additionally, it remains unknown whether the prevention of

oral H. pylori infection contributes to the reduction of

gastric H. pylori infection. Further research is required to

investigate active oral H. pylori infection and its

associations with gastric H. pylori infection.

Tongue coating samples are composed of food debris,

oral bacteria, epithelial cells and blood cells. Tongue bacterial

populations may be associated with oral health conditions. In a

previous study, the authors detected periodontopathic bacteria DNA

using swab samples collected from the tongue surface (27). Another group also reported that

H. pylori DNA was abundantly detected from tongue coating

samples (7). Therefore, the

present study aimed to collect oral samples from the tongue

surface. However, the presence of H. pylori DNA in

periodontal pockets could not be determined in the present study.

Therefore, further research to detect H. pylori DNA using

subgingival dental plaque is required to clarify the association

between H. pylori and periodontitis.

The present cross-sectional study had some

limitations. First, the present study did not investigate the

presence of H. pylori DNA in periodontal pockets. Therefore,

it is necessary to prove the presence of H. pylori using

subgingival dental plaque in future studies. Second, it remains

unclear whether active H. pylori infection is associated

with the oral hygiene condition as H. pylori colonization

could not be examined in the present study. Third, the present

study did not investigate gastric H. pylori infection or the

history of eradication treatments for H. pylori infection

(i.e., gastric lavage). Therefore, associations between oral H.

pylori and gastric H. pylori remain unknown. Fourth, the

presence of oral H. pylori in young individuals with healthy

periodontal tissue remains unknown. Fifth, it was impossible to

match H. pylori-positive and -negative cases by adjusting

confounding factors such as age, sex and health conditions due to

the small number of H. pylori-positive participants.

Finally, the present study was performed at a single hospital.

In conclusion, the presence of oral H. pylori

DNA may be associated with poor dental hygiene and periodontal

inflammation in older adults. It is critical to maintain good oral

health by practicing daily oral care to reduce the risk of oral

H. pylori infection.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Hiroshima University

(Grant no. 0G220).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

HY performed the experiments and analyzed the data.

HS conceived the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the

data, and wrote and reviewed the manuscript. HM, NH, HK, YK and YN

performed the experiments. TT and MS interpreted the data and

supervised the study. KO analyzed and interpreted the data and

reviewed the manuscript. HS and KO confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and informed consent

statement

The Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University

approved the study (No. E-1115). All patients agreed to participate

in this study and signed the informed consent form.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Marshall BJ and Warren JR: Unidentified

curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic

ulceration. Lancet. 1:1311–1315. 1984.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kusters JG, van Vliet AH and Kuipers EJ:

Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin

Microbiol Rev. 19:449–490. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY,

Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu

JCY, et al: Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori

Infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology.

153:420–429. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Mnichil Z, Nibret E, Hailegebriel T,

Demelash M and Mekonnen D: Prevalence and associated risk factors

of Helicobacter pylori infection in East Africa: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Microbiol. 55:51–64.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Go MF: Review article: Natural history and

epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 16:3–15. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mao X, Jakubovics NS, Bächle M, Buchalla

W, Hiller KA, Maisch T, Hellwig E, Kirschneck C, Gessner A,

Al-Ahmad A and Cieplik F: Colonization of Helicobacter

pylori in the oral cavity-an endless controversy? Crit Rev

Microbiol. 47:612–629. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Nagata R, Ohsumi T, Takenaka S and Noiri

Y: Current Prevalence of Oral Helicobacter pylori among

Japanese adults determined using a nested polymerase Chain reaction

assay. Pathogens. 10(10)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ogaya Y, Nomura R, Watanabe Y and Nakano

K: Detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in inflamed dental

pulp specimens from Japanese children and adolescents. J Med

Microbiol. 64:117–123. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Anand PS, Kamath KP, Gandhi AP, Shamim MA,

Padhi BK and Das S: Dental plaque as an Extra-gastric reservoir of

Helicobacter pylori: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Arch Oral Biol. 170(106126)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang XM, Yee KC, Hazeki-Taylor N, Li J, Fu

HY, Huang ML and Zhang GY: Oral Helicobacter pylori, its

relationship to successful eradication of gastric H. pylori

and saliva culture confirmation. J Physiol Pharmacol. 65:559–566.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

O'Leary TJ, Drake RB and Naylor JE: The

plaque control record. J Periodontol. 43(38)1972.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tirapattanun A, Namwat W, Kanthawong S,

Wongboot W, Wongwajana S, Wongphutorn P and Chomvarin C: Detection

of Helicobacter pylori and virulence-associated genes in

saliva samples of asymptomatic persons in northeast thailand.

Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 47:1246–1256.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Aksit Bıcak D, Akyuz S, Kıratlı B, Usta M,

Urganci N, Alev B, Yarat A and Sahin F: The investigation of

Helicobacter pylori in the dental biofilm and saliva samples

of children with dyspeptic complaints. BMC Oral Health.

17(67)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Medina ML, Medina MG and Merino LA:

Correlation between virulence markers of Helicobacter pylori

in the oral cavity and gastric biopsies. Arq Gastroenterol.

54:217–221. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Nomura R, Ogaya Y, Matayoshi S, Morita Y

and Nakano K: Molecular and clinical analyses of Helicobacter

pylori colonization in inflamed dental pulp. BMC Oral Health.

18(64)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wongphutorn P, Chomvarin C, Sripa B,

Namwat W and Faksri K: Detection and genotyping of Helicobacter

pylori in saliva versus stool samples from asymptomatic

individuals in Northeastern Thailand reveals intra-host

tissue-specific H. pylori subtypes. BMC Microbiol.

18(10)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Iwai K, Watanabe I, Yamamoto T, Kuriyama

N, Matsui D, Nomura R, Ogaya Y, Oseko F, Adachi K, Takizawa S, et

al: Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and

dental pulp reservoirs in Japanese adults. BMC Oral Health.

19(267)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kadota T, Hamada M, Nomura R, Ogaya Y,

Okawa R, Uzawa N and Nakano K: Distribution of Helicobacter

pylori and periodontopathic bacterial species in the oral

cavity. Biomedicines. 8(161)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Moosavian M, Kushki E, Navidifar T,

Hajiani E and Mandegari M: Is there a real relationship between the

presence of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and gastric

infection? A genotyping and restriction fragment length

polymorphism study on patient specimens with dyspepsia in southwest

iran. Int J Microbiol. 2023(1212009)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ogaya Y, Kadota T, Hamada M, Nomura R and

Nakano K: Characterization of the unique oral microbiome of

children harboring Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity. J

Oral Microbiol. 16(2339158)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wongsuwanlert M, Teanpaisan R, Pahumunto

N, Kaewdech A, Ruangsri P and Sunpaweravong S: Prevalence and

virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori isolated from oral

cavity of non-disease, gastritis, and gastric cancer patients. J

Dent Sci. 19:1036–1043. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Umeda M, Kobayashi H, Takeuchi Y, Hayashi

J, Morotome-Hayashi Y, Yano K, Aoki A, Ohkusa T and Ishikawa I:

High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori detected by PCR in

the oral cavities of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol.

74:129–134. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gebara EC, Pannuti C, Faria CM, Chehter L,

Mayer MP and Lima LA: Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori

detected by polymerase chain reaction in the oral cavity of

periodontitis patients. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 19:277–280.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Tang Z, Jin L and Yang Y: The dual role of

IL-17 in periodontitis regulating immunity and bone homeostasis.

Front Immunol. 16(1578635)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Khamri W, Walker MM, Clark P, Atherton JC,

Thursz MR, Bamford KB, Lechler RI and Lombardi G: Helicobacter

pylori stimulates dendritic cells to induce interleukin-17

expression from CD4+ T lymphocytes. Infect Immun. 78:845–853.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Holt SC, Kesavalu L, Walker S and Genco

CA: Virulence factors of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Periodontol

2000. 20:168–238. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Shigeishi H, Oka I, Su CY, Hamada N,

Nakamura M, Nishimura R, Sugiyama M and Ohta K: Prevalence of oral

Epstein-Barr virus and Porphyromonas gingivalis and their

association with periodontal inflamed surface area: A

cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore).

101(e31282)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|