Introduction

Breast cancer stands as the most prevalent

malignancy affecting women, exhibiting the highest incidence rates

within developed nations. While notable advances in screening and

therapy have improved the survival outcomes of patients, the

complexity of breast cancer biology continues to challenge clinical

management. Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease, and both

inter-tumor and intra-tumor variability affect prognosis and the

therapeutic response. This heterogeneity, although critical, also

underscores the need to individualize therapy and monitor for

diverse treatment outcomes, including adverse effects (1,2).

A crucial, yet often overlooked complication of

systemic therapy is the development of secondary malignancies

(3,4). Chemotherapy-induced tumor progression

and secondary genitourinary malignancies have become more

clinically relevant as survival rates improve (5). Among the agents used in adjuvant and

neoadjuvant regimens, cyclophosphamide, an alkylating agent, has

long been a cornerstone in breast cancer treatment protocols, such

as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) and

fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (FEC) (6,7).

Cyclophosphamide has been demonstrated in certain trials to

increase the breast cancer pathological complete response rate,

whereas other investigations have found no differences (8).

Cyclophosphamide functions as a prodrug metabolized

in the liver into active alkylating agents and inactive byproducts,

such as acrolein. Acrolein is known to irritate the urothelium and

has been implicated in the generation of reactive oxygen species,

which compromise the antioxidant defense of the bladder and

contribute to urothelial damage (9,10).

The first reported case of bladder transitional cell carcinoma

linked to cyclophosphamide was published in 1971 (5,11,12).

The cumulative dose and duration of exposure are key risk factors

for developing such malignancies. This highlights the importance of

long-term urological surveillance for patients treated with

cyclophosphamide.

The present study describes the case of a patient

with iatrogenic muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma occurring 7

years following adjuvant cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy for

breast cancer; the patient was without any other known risk

factors. The case described herein underscores the need for

heightened clinical awareness of secondary bladder malignancies in

long-term breast cancer survivors.

Case report

A 54-year-old woman was diagnosed with breast cancer

in 2015. The histopathological examination revealed invasive

lobular carcinoma grade I with metastases in six lymph nodes. It

should be noted that the initial microscopic evaluation of this

patient is not retrievable due to the lack of proper documentation

beforehand, although the formal report and description on the

findings remain available in the offline medical records system. A

mastectomy was performed in the authors' center (Haji Adam Malik

General Hospital, Medan, Indonesia), followed by chemoradiation

(six rounds of chemotherapy and 27 rounds of radiation) which was

completed in 2016 at Haji Adam Malik General Hospital, Medan,

Indonesia. Cyclophosphamide at a dose of 600 mg/m2 and

docetaxel (Brexel) at a dose of 75 mg/m2 per cycle were

administered as part of the chemotherapeutic regimen. Based on a

body surface area (1.6 m2), the estimated total

cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide was ~5,760 mg. During

chemotherapy, the patient did not suffer from any side-effects,

such as or hemorrhagic cystitis; however, the patient experienced

dysuria. The patient received hormonal therapy, such as tamoxifen

20 mg daily between 2015 and 2017, followed by exemestane 25 mg

daily until 2020, as part of standard endocrine management for

hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

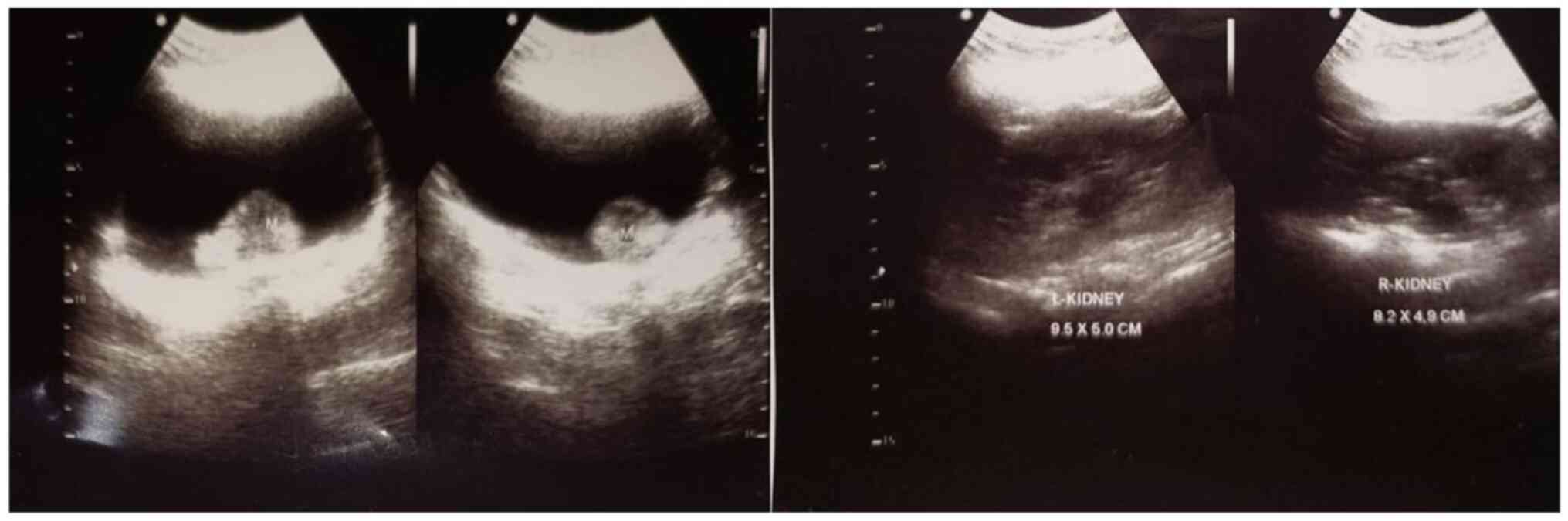

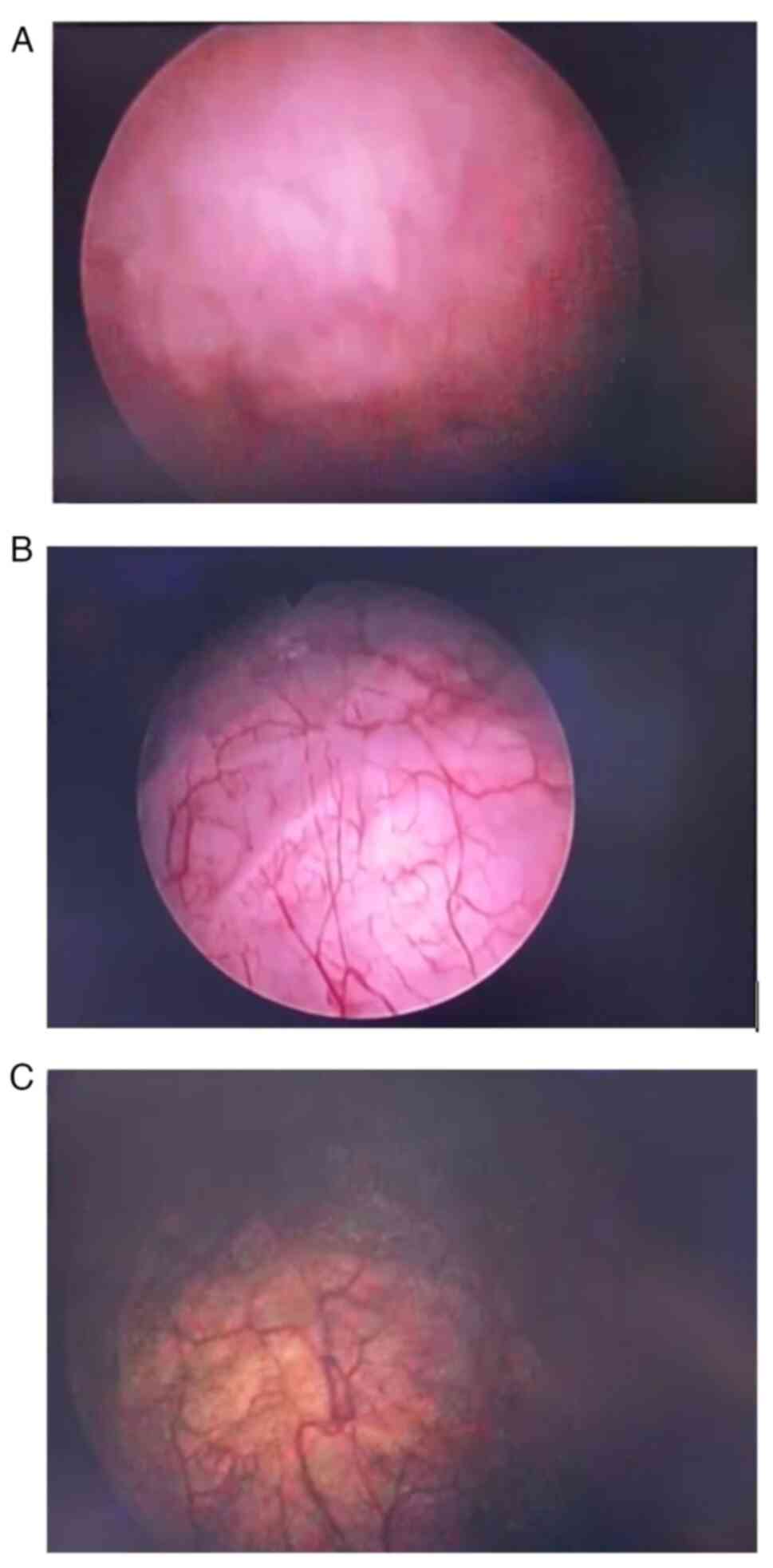

In June 2022, the patient experienced both hematuria

and dysuria and reported back to the Haii Adam Malik General

Hospital, Medan, Indonesia. Vital signs and clinical examination

were normal. An ultrasonography revealed tumors in the bladder

(Fig. 1). The patient underwent a

cystoscopy in September 2022; a bladder tumor was discovered on the

inferior wall of the bladder and was completely removed by

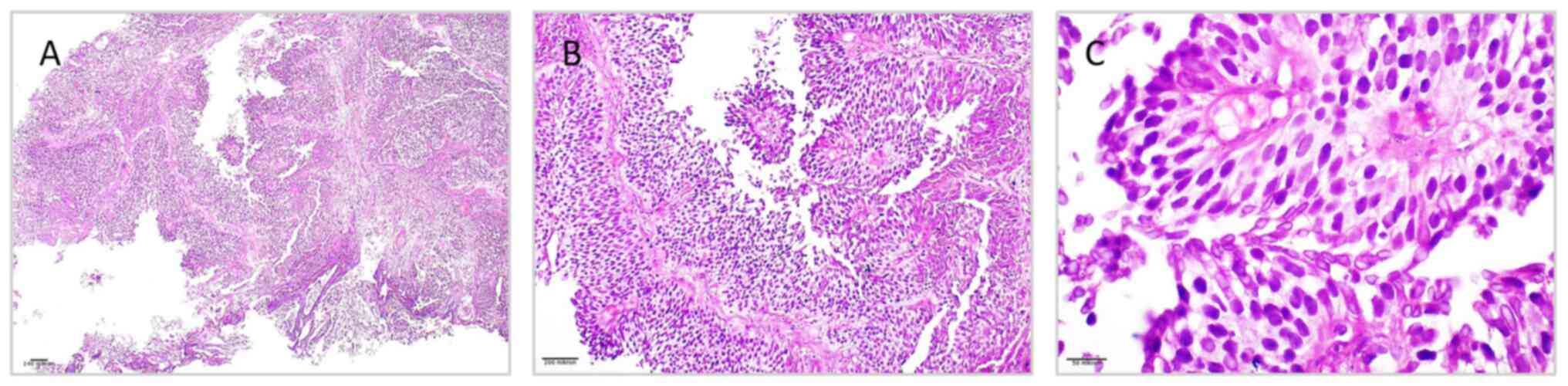

transurethral resection. From the histopathological analysis shown

in Figs. 2 and 3, the majority of the tumor cells

observed in the fragmented tissue from the base of the bladder were

organized in an infiltrative, solid growth pattern. All procedures

were performed in the Department of Surgical Pathology, Haji Adam

Malik General Hospital, Medan, Indonesia following a standardized

protocol. Tissue samples were paraffin-embedded and sectioned at a

thickness of 4-5 µm, then fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at

room temperature for 24 h. Staining was carried out using

hematoxylin and eosin reagents (MilliporeSigma) under standardized

conditions according to the manufacturer's instructions, including

maintaining reagent concentrations according to the manufacturer's

specifications, staining at room temperature (20-25˚C), and using

consistent incubation times (hematoxylin, 5-7 min; eosin, 1-2 min)

to ensure uniform staining and reproducible microscopic results.

Microscopic evaluation was performed using a light microscope

(Olympus BX53, Olympus Corporation). This protocol reflects the

routine, validated staining and analysis procedures established in

our laboratory.

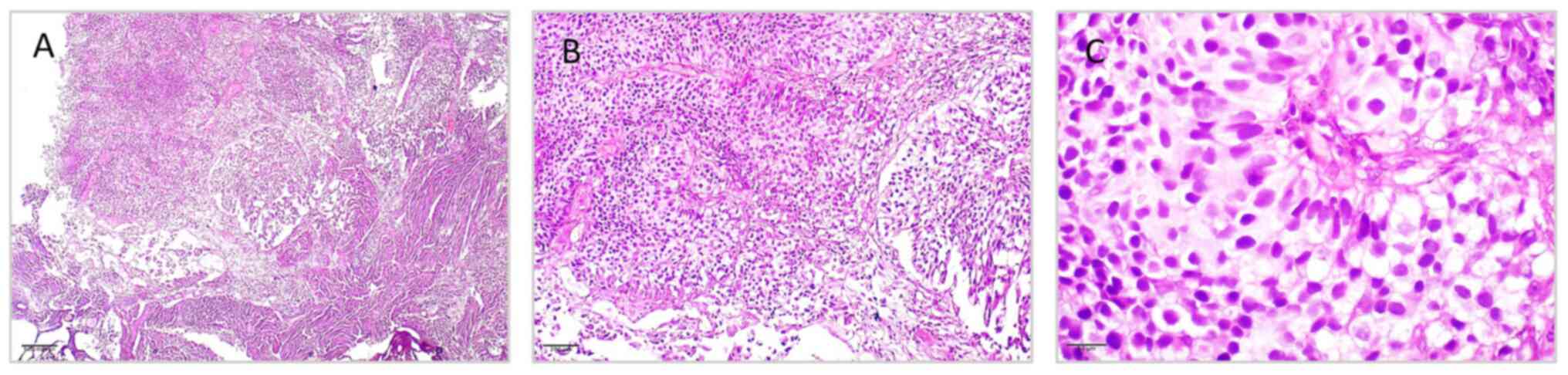

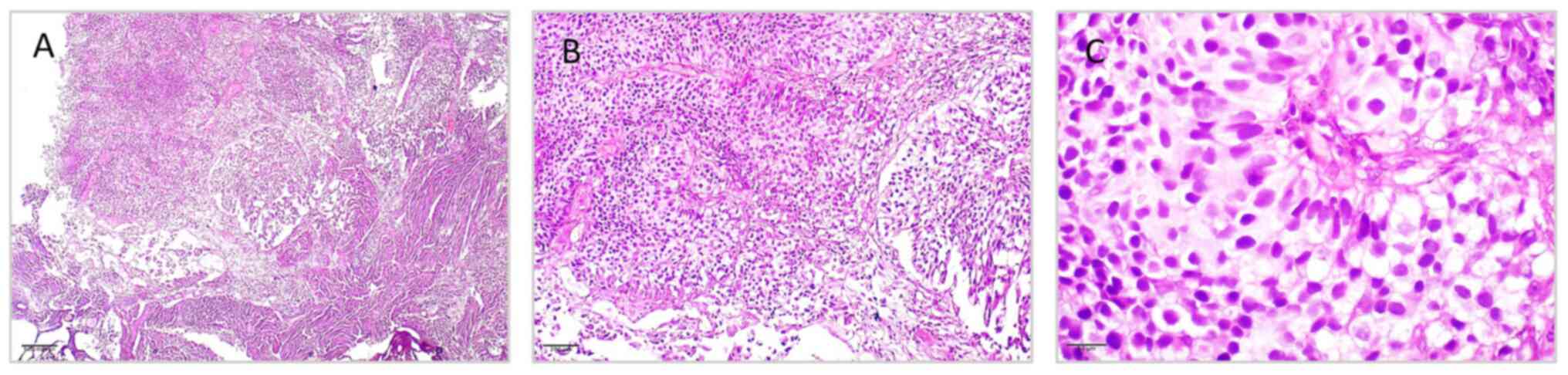

| Figure 3Histopathological features of

low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma from tumor mass of the

urinary bladder, illustrating (A) delicate papillary architecture

with fibrovascular cores lined by multiple layers of urothelial

cells, without evidence of stromal invasion (H&E staining;

magnification, x40); (B) mild nuclear pleomorphism, preserved

polarity and orderly cell arrangement (H&E staining;

magnification, x100); (C) tumor cells with uniform round-to-oval

nuclei, fine chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and low mitotic

activity, consistent with low-grade morphology (H&E staining;

magnification, x400). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. |

With their large irregular nuclei, numerous nucleoli

and thick chromatin, the tumor cells exhibited notable

pleomorphism. Throughout the sample, numerous mitotic figures,

including unusual forms, were observed. Tumor cells infiltrated the

muscularis propria, indicating muscle invasion. There were

interstitial bleeding and necrotic areas. The final diagnosis was

that of low-grade muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma (MIBC). A

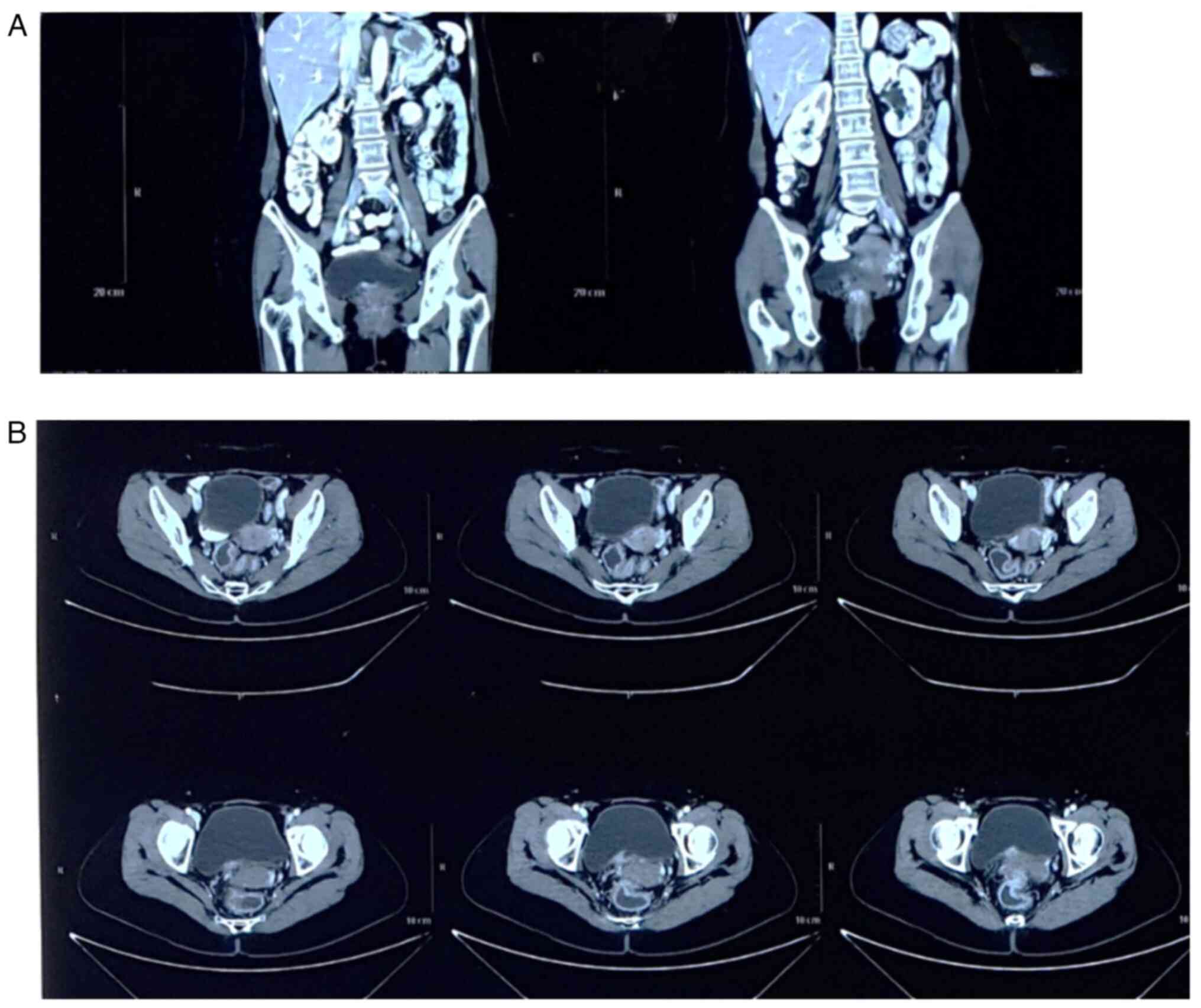

contrast computed tomography scan of the abdomen indicated focal

inferior bladder thickening, suggestive of a malignancy of the

bladder (Fig. 4). The patient was

then diagnosed with a bladder tumor T2N0M0. Radical cystectomy with

chemoradiation was initially recommended; however, the patient

declined surgery due to concerns over its invasiveness and impact

on quality of life, opting instead for bladder-preserving trimodal

therapy. The patient received four cycles of gemcitabine-cisplatin

and radiation (60-70 Gy) in 33 fractions, which was completed in

December 2022. The patient underwent routine cystoscopy every 3

months beginning from February 2023 (Fig. 5). The patient does not have any

risk factors for bladder cancer, such as smoking or a family

history of cancer, apart from treatment with cyclophosphamide.

Discussion

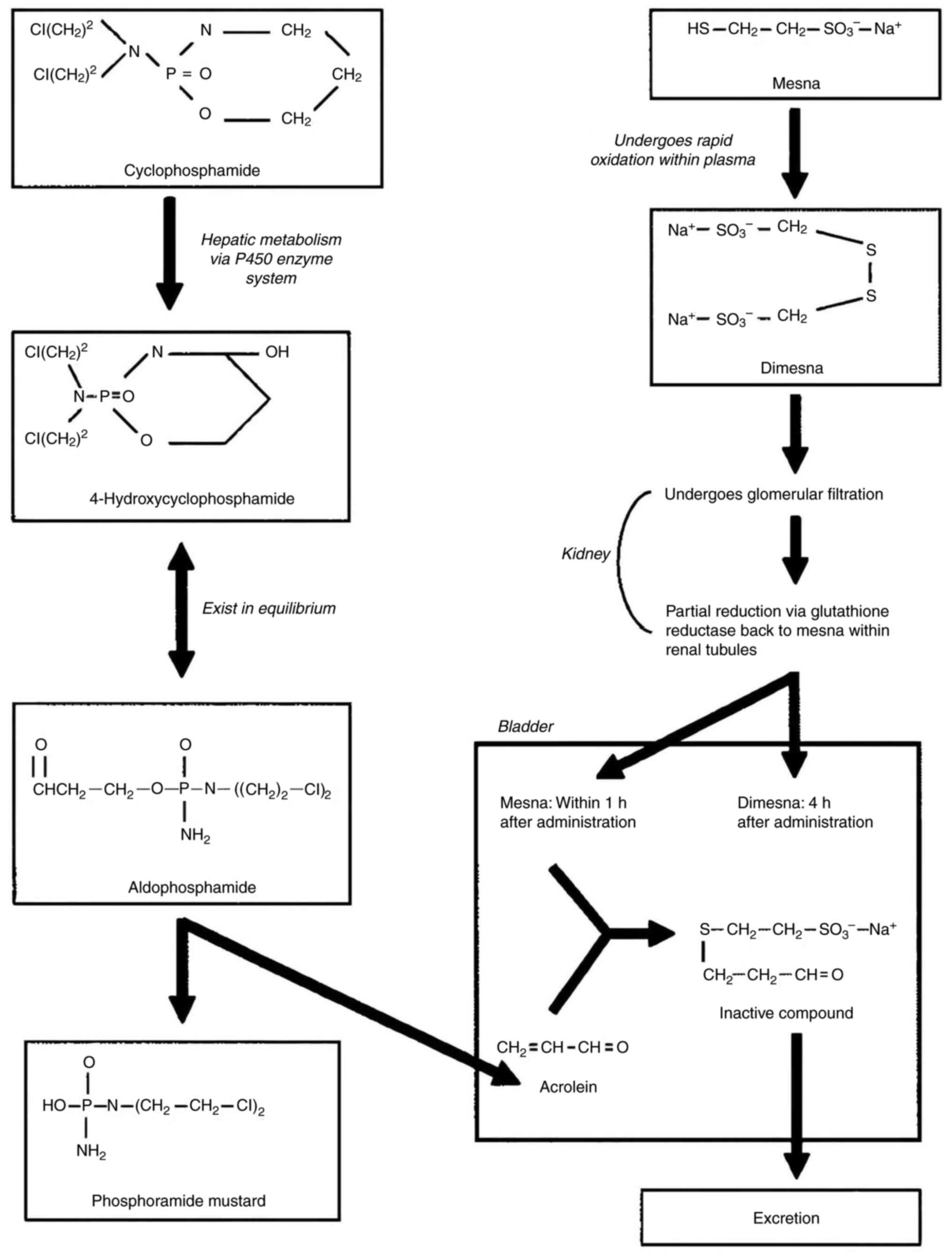

Mechanisms of cyclophosphamide-induced

carcinogenesis

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylator of the nitrogen

mustard group, which causes alkylation in DNA, thereby inhibiting

DNA synthesis and function. B- and T-cells are equally inhibited by

cyclophosphamide, although the toxicity is greater for B-cells

(6). Cyclophosphamide is a prodrug

which is converted to both active and inactive metabolites by the

hepatic P450 enzymatic system. Cyclophosphamide is transformed into

4-hydroxy-cyclophosphamide and its tautomer aldophosphamide in the

liver via the cytochrome p-450 monooxygenase system. During β

elimination, aldophosphamide releases acrolein and the alkylating

chemical phosphoramide mustard (Fig.

6) (13,14).

The inactive (non-alkylating) metabolite acrolein is

considered to cause cystitis. Although there is no concrete

evidence, acrolein is deemed to be a likely contributor to bladder

cancer as well. Similar to idiopathic bladder cancers, the vast

majority of bladder cancers that develop following treatment with

cyclophosphamide are transitional cell carcinomas; nevertheless,

there have been a few isolated occurrences of sarcomas and other

forms of bladder carcinoma documented (13). The patient in the present study was

diagnosed with bladder transitional cell carcinoma after 7 years of

terminating the use of cyclophosphamide as a breast cancer therapy.

In a previous study, a review of 54 cases of breast cancer with

bladder metastasis revealed that the median interval from breast

cancer diagnosis to bladder metastasis was 5.6 years. The majority

of these instances pertained to invasive ductal carcinoma, and the

bladder metastases were histologically congruent with the initial

breast cancer (15).

Cyclophosphamide therapy is a known risk factor for

carcinogenesis due to its mutagenic qualities, particularly in the

development of bladder cancer. When cyclophosphamide is

administered, its active metabolite, 4-hydroxy-cyclophosphamide,

diffuses into cancer cells and is responsible for the alkylating

ability of cyclophosphamide. The alkylating effects of

cyclophosphamide, such as mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor

gene, are more likely to be the molecular changes that mediate the

carcinogenic consequences (9,16).

Epidemiology and risk factors

The mode of cyclophosphamide administration that has

generated the most concern with regards to bladder toxicity is

daily oral dosing, as the duration of treatment and the total

cumulative exposure are generally higher compared with intermittent

intravenous dosing (11,13). The main risk factor is a cumulative

dose >20 g, and the median time from treatment to bladder cancer

diagnosis is 7 years (11). The

study by Yilmaz et al (10)

identified 17 cases of hemorrhagic cystitis and 2 cases of bladder

cancer among 1,018 patients treated with cyclophosphamide for

autoimmune diseases. The median time from initial diagnosis to the

onset of hemorrhagic cystitis was 10 months, while the median time

to the development of bladder cancer was 8 years. The median

cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide in their cystitis patients was

10 g. The only significant risk factor for hemorrhagic cystitis

identified in the risk factor analysis was cumulative

cyclophosphamide dosage (10).

In the case in the present study, the bladder cancer

was diagnosed 7 years after receiving cyclophosphamide therapy.

However, cyclophosphamide was not administered orally; it was

instead used as a chemotherapeutic regimen for breast cancer

treatment. Research has also demonstrated the association between

cyclophosphamide therapy and bladder cancer (17). Such cases of bladder cancer

occurring years after cyclophosphamide therapy in breast cancer

patients are rare.

The administration of cyclophosphamide, particularly

via oral dosage, has elicited considerable apprehension regarding

its long-term impact on the bladder; nevertheless, other factors,

including preoperative hydronephrosis and renal insufficiency, may

also significantly influence the advancement of bladder cancer.

Increased blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine values,

indicative of renal impairment, have been identified as independent

predictors of locally progressed bladder cancer, highlighting the

necessity for thorough renal function monitoring in patients

undergoing cyclophosphamide treatment (18).

In a previous study, it was demonstrated that ~50%

of 145 patients with Wegener's granulomatosis who received

cyclophosphamide experienced hematuria, and 7 of these individuals

went on to develop bladder cancer (19). Among those who subsequently

developed bladder cancer, the median cumulative dose reached ~113 g

over a median treatment duration of 86 months, compared with only

25 g in patients without bladder cancer. Each additional 10 g of

cyclophosphamide was associated with a doubling of the risk of

developing bladder cancer (19).

In another study by Stillwell et al (20), only 5 of the 100 patients in a

trial with cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis went on to

develop bladder cancer. For these 5 patients, the average dose of

cyclophosphamide was 195 g for 60 months, which was significantly

greater than the dosage for the other patients (20). Hemorrhagic cystitis and bladder

cancer were related in each of these investigations (9).

The risk of cyclophosphamide-induced bladder cancer

is associated with the high dose and long duration of therapy.

Exposure to cyclophosphamide for a period >13 months has been

shown to be associated with an almost 8-fold increased risk of

developing bladder cancer (21).

In the study by Radis et al (22), 9 of the 50 cancers observed in 37

of the 119 individuals with rheumatoid arthritis who received

cyclophosphamide were bladder cancers, and 19 of the cancers were

skin cancers, as opposed to no bladder cancers and six skin cancers

in the control group. Cyclophosphamide had stopped being used for

14, 16, and 17 years when three bladder tumors developed. The

patients who developed cancer received a median cumulative dose of

100 g. However, it is not known whether it was a superficial or a

muscle-invasive bladder tumor (22).

In the patient in the present study, although she

received only six cycles of cyclophosphamide at 600

mg/m2 per cycle, an estimated cumulative dose well below

the established risk threshold, she developed MIBC 7 years later.

This suggests that even lower cumulative doses, in the absence of

acute urinary toxicity, may contribute to carcinogenesis in

susceptible individuals.

Latency to diagnosis has been found to range from 0

to 14 years, with a median of 2.7 years. Saoji (9) reported a latency of 5 and 9 years in

2 cases, while Volm et al (5) documented bladder cancer 18 years

following the termination of therapy. The case in the present study

falls within this window. These findings underscore the need for

long-term urologic surveillance in cancer survivors treated with

cyclophosphamide, as bladder cancer may emerge many years after

therapy ends (5,9).Surveillance recommendations and

clinical implications. The incidence of bladder carcinoma is

considered to be lower in patients receiving intravenous

cyclophosphamide, likely due to the lower total cumulative dose

used with this form of therapy (10,11).

In the study conducted by Saoji (9), 3 patients all had advanced disease

when they were first seen, and they all received more than 50 g of

oral cyclophosphamide over a 3-year period. In fact, 2 of the

patients needed a higher dose of cyclophosphamide (100 g) to

control their disease. None of these 3 patients ever expressed any

complaints about urinary symptoms while receiving treatment. While

undergoing treatment and throughout the follow-up period, they

underwent routine examinations, including urine analyses. In

addition to the risk of bladder cancer, cyclophosphamide is

associated with the risk of developing other malignancies, such as

lymphoma, leukemia and squamous cell carcinoma (9).

The risk factors for bladder cancer are demonstrated

in Table I (4). In the case in the present study,

cyclophosphamide therapy may be the cause of bladder cancer when

considering the risk factors for bladder cancer development.

| Table IRisk factors of urothelial cancer. |

Table I

Risk factors of urothelial cancer.

| Risk factors for

urothelial cancer |

|---|

| Cigarette

smoking |

| Exposure to aryl

amines (workers in organic chemical, dye, rubber, paint

industries) |

| Phenacetin abuse |

| Familial history |

| Cyclophosphamide

therapy |

| Nonglomerular

hematuria |

It is recommended that all patients treated with

cyclophosphamide undergo routine urinalysis every 3 to 6 months,

even after completing treatment, as hematuria is often the first

sign of cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis or bladder cancer.

Although outcome data to support this level of surveillance are

currently lacking, early detection may be critical. In the event

that a patient presents with microscopic or gross hematuria, a

cystoscopy should be performed (5). In cases where no visible lesion is

detected but hematuria persists, repeat cystoscopy every 1 to 2

years is advisable. Stillwell et al specifically recommended

that all patients exposed to cyclophosphamide and with microscopic

hematuria undergo a cystoscopic evaluation. Persistent microscopic

hematuria has been associated with progressive thickening of the

bladder wall (22,23).

In the case in the present study, the patient did

not report hematuria during cyclophosphamide therapy, although mild

dysuria was noted. At 7 years after completing chemotherapy,

including cyclophosphamide treatment, the patient developed

hematuria and dysuria. Cystoscopy revealed a bladder tumor, which

was completely resected via transurethral resection. As the patient

declined radical cystectomy and chemoradiation, bladder-preserving

trimodal therapy was administered, followed by surveillance

cystoscopy every 3 months.

In conclusion, due to its mutagenic characteristics,

notably in the development of bladder cancer, cyclophosphamide

therapy is a known risk factor for carcinogenesis. The high dose

and prolonged length of therapy are linked to an increased risk of

bladder cancer caused by cyclophosphamide. Several years following

the start of treatment, cyclophosphamide-induced bladder cancer may

develop. Consequently, ongoing monitoring is necessary.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Data and materials availability

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SMW, MHW, RR and DH conceived and designed the

study. The methodology was initiated by SMW, GPS, DDK and ZZT. The

software-based analysis was performed by MHW, RR, MIS and DISS.

Data validation was performed by SMW, DH and GPS and FFP. Formal

analysis was performed by RR, DH, CTM, GPS and FFP. Investigation

of the patient's data was performed by SMW, MHW, RR, MIS and DISS.

Resources were provided by SMW, MHW and ZZT (providing

institutional access to databases, computing or mathematical

analysis software, and also sharing reference management tools).

Data curation was performed by SMW, CTM, MHW and RR. SMW, CTM and

RR analyzed the data. The manuscript was drafted by SMW, MHW, DH

and RR. SMW, MHW, DH, GPS, DDK, FFP and CTM. Visualization was

initiated by CTM, MIS and DISS. The study was supervised by SMW,

GPS and FFP. Lastly, project administration was performed by MHW,

RR and ZZT. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. RR, CTM, MIS and DISS confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval for the present study was obtained

from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Sumatera

Utara under the issued ID with no. 330/KEPK/USU/2025 (approving

institution komiteetik@usu.ac.id) and the ethics committee agreed

with consent for this investigation being obtained verbally. Verbal

informed consent was obtained from the patient for their

participation in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the

patient for their anonymized information, and any related images to

be published in the present study (‘I understand that my data will

be published in this article. I consent to this publication,

provided that my identity remains confidential and no identifying

information is disclosed’).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

GLOBOCAN: All Cancer. The Global Cancer

Observatory, 2020.

|

|

2

|

Pedersen RN, Esen BÖ, Mellemkjær L,

Christiansen P, Ejlertsen B, Lash TL, Nørgaard M and Cronin-Fenton

D: The incidence of breast cancer recurrence 10-32 years after

primary diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 114:391–399. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sinanoglu O, Yener AN, Ekici S, Midi A and

Aksungar FB: The protective effects of spirulina in

cyclophosphamide induced nephrotoxicity and urotoxicity in rats.

Urology. 80:1392.e1–e6. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Abraham P, Kanakasabapathy I and Sugumar

E: Decrease in the activities of lysosomal enzymes may contribute

to the urotoxicity of cyclophosphamide in the rat. Biomed Res.

18:131–136. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Volm T, Pfaff P, Gnann R and Kreienberg R:

Bladder carcinoma associated with cyclophosphamide therapy for

ovarian cancer occurring with a latency of 20 years. Gynecol Oncol.

82:197–199. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Veitch Z, Khan OF, Tilley D, Tang PA,

Ribnikar D, Stewart DA, Kostaras X, King K and Lupichuk S: Impact

of cumulative chemotherapy dose on survival with adjuvant FEC-D

chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 8:957–967.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Liga EGK, Abdullah N, Tiro E, Maisuri S

and Chalid T: The effect of cyclophosphamide chemotherapy on

ovarian AntiMüllerian hormone levels in breast cancer patients.

Indonesian J Obstetr Gynecol. 6:64–67. 2018.

|

|

8

|

Kang YK, Si YR, An GY and Yuan P: Efficacy

and safety of cyclophosphamide in anthracycline- and Taxane-based

neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Gland

Surg. 10:252–261. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Saoji VA: Cyclophosphamide-induced cancers

in pemphigus patients-A report of three cases. Indian J Drugs

Dermatol. 6:32–34. 2020.

|

|

10

|

Yilmaz N, Emmungil H, Gucenmez S, Ozen G,

Yildiz F, Balkarli A, Kimyon G, Coskun BN, Dogan I, Pamuk ON, et

al: Incidence of cyclophosphamide-induced urotoxicity and

protective effect of mesna in rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol.

42:1661–1666. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Emadi A, Jones RJ and Brodsky RA:

Cyclophosphamide and cancer: Golden anniversary. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 6:638–647. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Worth PH: Cyclophosphamide and the

bladder. Br Med J. 3(182)1971.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Monach PA, Arnold LM and Merkel PA:

Incidence and prevention of bladder toxicity from cyclophosphamide

in the treatment of rheumatic diseases: A data-driven review.

Arthritis Rheum. 62:9–21. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sohn HJ, Kim SH, Lee GW, Kim S, Kang HJ,

Ahn JH, Kim SB, Kim SW, Kim WK and Suh C: High-dose chemotherapy of

cyclophosphamide, thiotepa, and carboplatin (CTCb) followed by

autologous stem-cell transplantation for metastatic breast cancer

patients: A 6-year follow-up result. Cancer Res Treat. 37:24–30.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhou H, Liu D, Chen L, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Ge

Y, Liu M and Kong T: Metastasis to the bladder from primary breast

cancer: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett.

27(249)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gor PP, Su HI, Gray RJ, Gimotty PA, Horn

M, Aplenc R, Vaughan WP, Tallman MS, Rebbeck TR and DeMichele A:

Cyclophosphamide-metabolizing enzyme polymorphisms and survival

outcomes after adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast

cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res.

12(R26)2010.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Chou WH, McGregor B, Schmidt A, Carvalho

FLF, Hirsch MS, Chang SL, Kibel A and Mossanen M:

Cyclophosphamide-associated bladder cancers and considerations for

survivorship care: A systematic review. Urol Oncol. 39:678–685.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Warli SM, Prapiska FF, Siregar DIS and

Seja IA: Tumor markers as predictors of acute kidney injury

incidence and staging of the Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

receiving chemoradiation therapy. World J Oncol. 14:423–429.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Knight A, Askling J, Granath F, Sparen P

and Ekbom A: Urinary bladder cancer in Wegener's granulomatosis:

Risks and relation to cyclophosphamide. Ann Rheum Dis.

63:1307–1311. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Stillwell TJ, Benson RC Jr and Burgent EO

Jr: Cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis in Ewing's

sarcoma. J Clin Onco. 6:76–82. 1988.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Warli SM, Prapiska FF, Siregar DIS and

Wijaya WS: Prediction of locally advanced bladder tumor using

preoperative clinical parameters. Urol Ann. 15:412–416.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Radis CD, Kahl LE, Baker GL, Wasko MC,

Cash JM, Gallatin A, Stolzer BL, Agarwal AK, Medsger TA Jr and Kwoh

CK: Effects of cyclophosphamide on the development of malignancy

and on long-term survival of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A

20-year followup study. Arthritis Rheum. 38:1120–1127.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Tanaka T, Nakashima Y, Sasaki H, Masaki M,

Mogi A, Tamura K and Takamatsu Y: Severe hemorrhagic cystitis

caused by cyclophosphamide and capecitabine therapy in breast

cancer patients: Two case reports and literature review. Case Rep

Oncol. 12:69–75. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|