Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is an aggressive

malignancy with high global incidence, particularly in Southeast

Asia (1). Its tendency for

late-stage diagnosis and early lymphatic spread contributes to poor

outcomes, particularly in technically unresectable cases (2). While early-stage OSCC is associated

with favorable survival rates, prognosis significantly exacerbates

in advanced-stage disease (3,4).

Identifying reliable molecular markers is crucial for early

detection, prognostication and personalized treatment strategies.

Recent advances in genomic and transcriptomic technologies have

enabled the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

associated with tumor growth, immune regulation and patient

survival in OSCC (5). These

molecular signatures provide valuable insight for early diagnosis,

treatment stratification and monitoring therapeutic outcomes

(6). In parallel, epigenetic

alterations, such as DNA methylation and copy number variations

(CNVs) are known to influence gene expression by silencing tumor

suppressor genes or activating oncogenes, contributing to disease

progression (7,8). The tumor microenvironment,

particularly immune cell infiltration, also plays a critical role

in shaping the clinical behavior of OSCC and influencing treatment

response (9).

Transposable elements, such as Alu sequences

contribute to genomic instability and have been implicated in

cancer development through mechanisms such as insertional

mutagenesis and RNA editing (10,11).

Although typically found in introns, some Alu insertions can

disrupt gene function by terminating transcription early (12,13).

Furthermore, Alu sequences harbor multiple transcription factor

binding sites, which can influence gene expression and potentially

activate oncogenic pathways. Elevated fragmented Alu DNA in

circulating DNA has been linked to a high tumor burden, suggesting

their potential as non-invasive cancer biomarkers (14). Beyond standard treatment

approaches, there is growing interest in exploring phytochemicals

and repurposed drugs as alternative means to interfere with

oncogenic signaling in OSCC. Naturally occurring compounds derived

from plants have demonstrated anticancer activity and are valued

for their potential to reduce toxicity, while inhibiting tumor

progression (15). At the same

time, established chemotherapeutic agents, such as vinorelbine are

being reconsidered for new applications, particularly through the

analysis of their binding affinity to cancer-related molecular

targets. In silico techniques, such as molecular docking and

molecular dynamics simulations currently play a key role in

predicting and validating the therapeutic relevance of these

candidate compounds (16).

The present study focused on combining genomic,

epigenetic, immunological and transposable element analyses to

uncover key biomarkers and therapeutic targets associated with

OSCC. Gaining insight into the molecular events that drive OSCC

progression can support the advancement of precision medicine

strategies and enable the development of biomarker-guided

interventions, with the goal of enhancing early diagnosis,

prognostic accuracy and treatment outcomes.

Materials and methods

Analysis of DEGs

The analysis was performed using RNA sequencing data

from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database for oral cancer

(GSE246050). DEGs were identified using GEO2R, an interactive tool

for analyzing high-throughput gene expression data. The DEGs were

identified based on the criteria of a log fold change (LogFC) of ≥1

for upregulated genes and <-1 for downregulated genes. Genes

meeting these thresholds and exhibiting a false discovery rate

(FDR)-adjusted P-value ≤0.05 were deemed statistically significant

(17).

Interaction network construction

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of

DEGs was constructed using the STRING database. To further analyze

the network, the list of genes was imported into Cytoscape (version

3.9.1) for the visualization and topological analysis of the

structural properties of the network. A high-confidence interaction

score (≥0.7) was applied to assess the degree of connectivity

within the network. Key hub genes were identified based on a degree

threshold of ≥10, indicating their central role in the interaction

network.

Survival analysis and heatmap

visualization of the survival associated genes

The overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival

(DFS) analyses of genes from the GEO dataset were performed using

the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) online

tool (18), which has been cited

in >400 studies (19). GEPIA

performs a survival analysis on the basis of the gene expression

level, and a hypothesis is evaluated using the log-rank test

(Mantel-Cox test). Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the Cox

proportional hazards model with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Genes that had a log-rank P-value of ≤0.05 were regarded as

significant. To visualize the expression pattern of these important

genes heatmap was created using the Complex Heatmap package in R

studio (20).

cBioPortal analysis

To assess the impact of survival-related DEGs on

patient outcomes, the expression data of head and neck squamous

cell carcinoma (HNSCC) were downloaded from the Firehose Legacy

dataset of cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/datasets). The dataset

contained the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)

pathological staging, survival data, patient IDs and gene

expression values. Gene expression values were categorized as high

or low based on the median ± 2SEM cut-off. The receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to identify the

prognostic value of the selected genes in relation to OS using

survival duration in months and dichotomized levels of gene

expression (high and low). Genes with a greater area under the

curve (AUC) were regarded as having a greater predictive potential

and were selected to be further analyzed. Moreover, the ROC

analysis was also utilized to examine the association between the

patterns of gene expression and the advanced T4 tumor stage

classification, which also provides information about their

association with the severity of the disease. OriginPro (version

2019b; https://www.originlab.com/) was used all

statistical analysis since it offers advanced statistical analysis

tools to enable comprehensive analysis of data. ROC curves were

generated based on a classification model at all classification

thresholds, incorporating true positive rate (sensitivity) and

false positive rate (1-specificity) as key parameters. A P-value

<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway

analysis

Functional enrichment analysis was performed using

the WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt; https://www.webgestalt.org/), which includes GO

annotation and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway analysis (21).

Association of selected genes with

methylation probes

The methylation profiling of selected genes was

conducted using the MethSurv database, which enables CpG

site-specific survival analysis based on methylation level

(22). The platform performs

univariable and multivariable survival analyses for CpG sites

located within or near the query gene using Cox proportional

hazards models. Differences in survival between highly methylated

and lowly methylated patient groups are visualized using

Kaplan-Meier (KM) plots.

CNV and gene expression correlation

analysis

To validate the correlation between CNVs and

survival-associated DEGs in an independent cohort, RNA sequencing

data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were accessed via

cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org). CNV data

were pre-processed using Genomic Identification of Significant

Targets in Cancer (GISTIC), which estimates somatic copy number

alterations for each annotated gene. The CNV values were

categorized as follows: -2 (homozygous deletion), -1 (heterozygous

loss), 0 (diploid), 1 (single-copy gain), and 2 (high-level

amplification or multiple-copy gain). A Spearman's correlation

analysis was conducted to determine the correlation between CNVs

and the level of gene expression using a linear regression model.

The Rho values of Spearman's correlation were used to evaluate the

correlation.

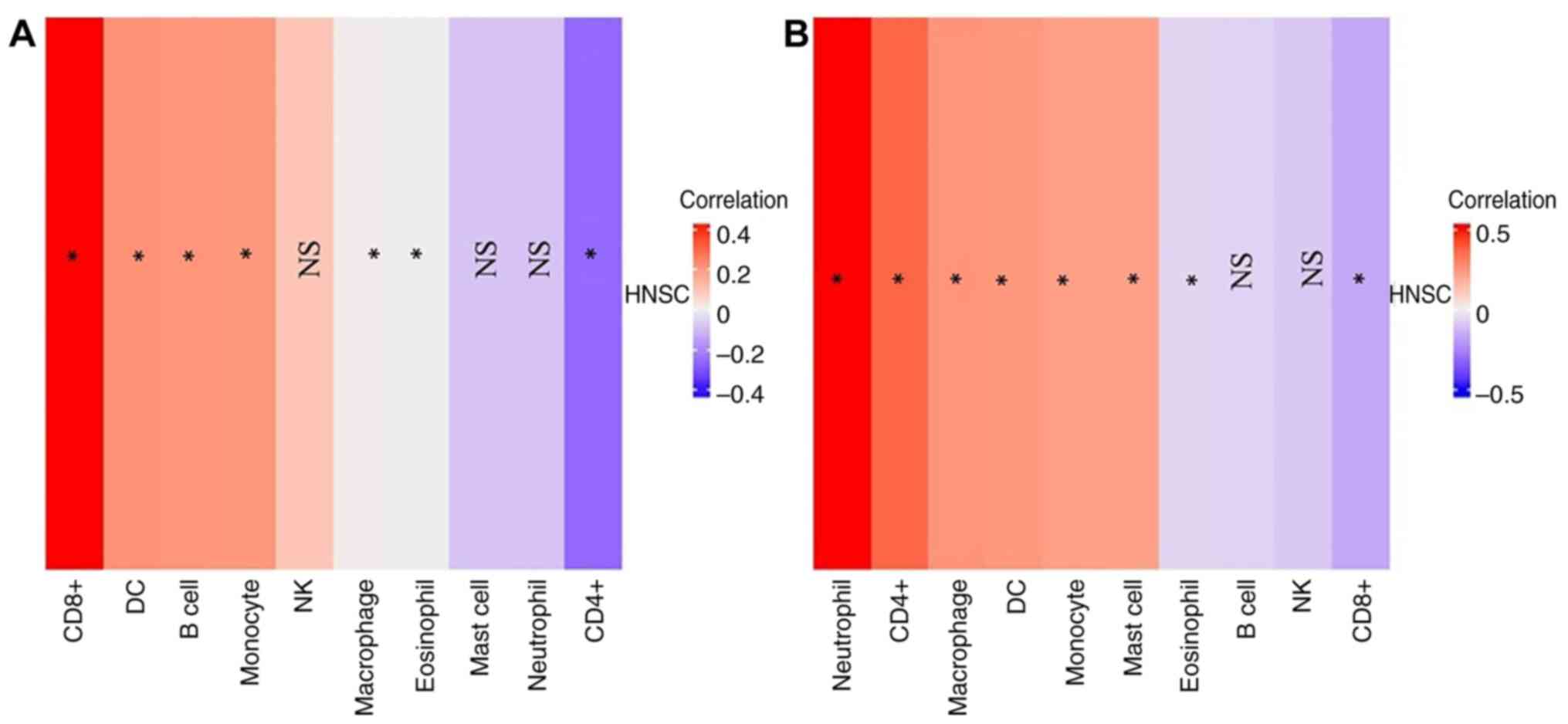

Correlation between amphiregulin

(AREG) and C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) and immune

infiltration

The association between AREG and

CX3CR1 expression and tumor-infiltrating immune cells was

analyzed using the TIMER 2.0 database (http://timer.comp-genomics.org/) (23). The infiltration scores were

calculated using the single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

(ssGSEA) method. Additionally, heatmaps were generated to visualize

the correlation between the expression of genes and the immune cell

infiltration based on Spearman's Rho values. The analysis provides

the understanding of the possible role of the survival-related DEGs

in immune modulation in the tumor microenvironment.

Patients and ethics statement

The present study enrolled 18 patients from Parul

Sevashram Hospital, Vadodara, India, including 9 patients with oral

cancer and 9 patients with technically unresectable oral cancer

(TUOC). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics

Committee of Parul University (Approval no.

PUIECHR/PIMSR/00/081734/5307) and was conducted in accordance with

institutional ethical standards and regulatory guidelines. All

patients signed an informed consent form. In addition, blood

samples were collected from 6 healthy individuals to serve as

controls for the DNA-based assays (Table I). All procedures performed in the

present study were in accordance with the principles for medical

research of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later

amendments or comparable ethical standards.

| Table IClinical and pathological

characteristics of the patients and controls included in the

present study. |

Table I

Clinical and pathological

characteristics of the patients and controls included in the

present study.

| Group | Age (years) | Sex | Stage/substage | Sample type | HIV status | HCV status |

|---|

| OSCC | 65 | Female | CT2aN1M0 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| OSCC | 58 | Male | CT4aN1M0 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| OSCC | 72 | Male | CT1aN1M0 | Blood | Information not

available | Information not

available |

| OSCC | 62 | Male | CT4aN1M0 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| OSCC | 62 | Male | CT2aN1 M0 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| OSCC | 32 | Male | CT2aN1 M0 | Blood | Information not

available | Information not

available |

| OSCC | 49 | Female | CT2aM0 | Blood | Information not

available | Information not

available |

| OSCC | 42 | Male | CT4aM0 | Blood | Information not

available | Information not

available |

| OSCC | 52 | Female | CT2aN1 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| TUOC | 62 | Male | CT1aN1M0 | Blood | Information not

available | Information not

available |

| TUOC | 39 | Female | CT4aN1M0 | Blood | Information not

available | Information not

available |

| TUOC | 53 | Male | CT2aN2M0 | Blood | Information not

available | Information not

available |

| TUOC | 42 | Female | CT4aN2M0 | Blood | Positive | Information not

available |

| TUOC | 45 | Male | CT4aN2M0 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| TUOC | 44 | Male | CT4aN2M0 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| TUOC | 43 | Female | CT2aN2M0 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| TUOC | 67 | Male | CT1aM0 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| TUOC | 57 | Female | CT2aN2 | Blood | Positive | Non-reactive |

| Control | 24 | Female | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 27 | Female | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 23 | Female | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 24 | Female | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 23 | Male | - | - | - | - |

| Control | 23 | Male | - | - | - | - |

Patient cohort

The clinical and pathological details of all

patients included in the study are summarized in Table I. The table provides information on

age, sex, tumor stage, grade, tumor size, lymph node status and HIV

results. In the OSCC group, the age of the patients ranged from 32

to 72 years, with a median age of 58±4.18 years. In the TUOC group,

the age ranged from 39 to 67 years, with a median age of 45±3.30

years. Data on HCV status were not available for all cases, as this

information was not routinely recorded in patient files. Since the

study focused primarily on gene expression profiling rather than

viral-associated carcinogenesis, the absence of HCV data does not

affect the interpretation of the findings (24).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from fresh blood using the

QIAamp® RNA Blood Mini kit (cat. no. 52304; Qiagen,

Inc.) and RNA purity was confirmed by spectrophotometric analysis

(A260/A280 ratio between 1.8-2.0). cDNA was synthesized from 20 ng

RNA using the G-Biosciences cDNA Synthesis kit (cat. no. 786-5020;

G-Biosciences) and used for qPCR on the Rotor-Gene Q system with

SYBR-Green Master mix (cat. no. 786-5062; G-Biosciences). qPCR was

run in triplicate under standard cycling conditions as follows:

95˚C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95˚C for 15 sec and 60˚C

for 60 sec. The relative expression levels of the target gene mRNAs

were calculated using the comparative Cq method (relative

expression, 2-ΔΔCq) (25), using GAPDH as an internal control.

The primer sequences were as follows: AREG forward,

5'-GTGGTGCTGTCGCTCTTGATACTC-3' and reverse,

5'-TCAAATCCATCAGCACTGTGGTC-3'; CX3CR1 forward,

5'-GGGACTGTGTTCCTGTCCAT-3' and reverse, 5'-GACACTCTTGGGCTTCTTGC-3';

and GAPDH forward, 5'-CCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC-3' and reverse,

5'-TTCCTCTTGTGCTCTTGCTG-3'.

Alu DNA quantification

Blood DNA was extracted from patients with 18 oral

cancers using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (cat. no. 51104;

Qiagen, Inc.) and stored at -80˚C. AluY sequences and subtypes were

obtained from the Dfam database (26), and qPCR was conducted in triplicate

using primers for AluY, (forward, 5'-GTAATCCCAGCACTTTGGG-3' and

reverse, 5'-TAGTAGAGACGGGGTTTCAC-3'), AluY-K12 (forward,

5'-TACAAAAAATTAGCCGGGCG-3' and reverse, 5'-CATGCCATTCTCCTGCCTC-3'

and AluY-I6 (forward, 5'-GTAATCCCAGCACTTTGGG-3' and reverse,

5'-GTTCACGCCATTCTCCTGC-3'). Each 10 µl PCR reaction consisted of 5

µl SYBR-Green mix (G-Biosciences), 1 µl forward/reverse primer (10

µM), and 100 pg DNA. The cycling conditions were 95˚C for 10 min,

followed by 45 cycles at 95˚C for 15 sec and 60˚C for 60 sec, and a

hold at 60˚C for for ALUY and ALUY-K12. For ALUY-I6, the conditions

were 95˚C for 10 min, 30 repeats at 95˚C for 15 sec, and 65˚C for

60 sec. The specificity of the PCR products was confirmed by

melting curve analysis. The specificity of the PCR products was

confirmed by melting curve analysis. Quantification of total blood

Alu DNA content was based on a standard curve prepared from serial

dilutions of genomic DNA (10 ng to 0.01 pg) from healthy donors.

Each qPCR run included a no-template control, and the results are

reported as the mean ± SEM.

Molecular docking analysis of AREG

inhibitors

A library of 1,525 plant-derived bioactive compounds

was initially screened using SWISS-ADME to evaluate their

physicochemical properties and drug-likeness, resulting in the

selection of 174 potential candidates. In parallel, 50 clinically

reported anticancer drugs were shortlisted based on literature

evidence for their relevance in cancer therapy. Molecular docking

was performed between these compounds and the AREG protein using

PyRx, with the AREG structure obtained from PDB (2RNL) and compound

structures retrieved from PubChem (27). Among the screened molecules, the

top two compounds exhibiting the highest binding affinity and key

hydrogen bonding interactions with AREG were selected for molecular

dynamics simulations to further assess their stability and

inhibitory potential.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations were carried out for

cabraleadiol (CID-21625899) and vinorelbine in complex with AREG

using the NAMD3 simulation package with the CHARMM force field. Key

structural parameters, including root mean square deviation (RMSD),

root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and radius of gyration (Rg),

were calculated using NAMD3 system-building commands and visualized

with the Bio3D v2.3-0 package (http://thegrantlab.org/bio3d_v2/download). The

simulation was run for a total of 200 nsec, and the binding free

energy (ΔG) of each drug-protein complex was estimated using the

NAMD Energy plugin.

Statistical analysis

The expression of DEGs in GEO2R was assessed using

moderated t-tests with the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction

(|LogFC| ≥1). Survival analyses were conducted in GEPIA using Cox

proportional hazards models and log-rank tests, with HRs and 95%

CIs reported. ROC curves (OriginPro 2019b) were generated using

survival duration and dichotomized gene expression, and AUC values

assessed prognostic performance. Spearman's correlation analysis

was used to analyze the correlations between CNV and gene

expression and immune infiltration scores in TIMER 2.0. MethSurv

applied Cox regression to compare survival between high- and

low-methylation groups. qPCR data from the three study groups

(resectable oral cancer, n=9; technically unresectable oral cancer,

n=9; and healthy controls, n=6) were analyzed using the

2-ΔΔCq method and are presented as

the mean ± SEM. Comparisons among the three groups were performed

using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test to identify

pairwise differences. Alu DNA quantification was performed on two

groups (resectable oral cancer vs. technically unresectable oral

cancer; n=9 per group) and compared using an unpaired two-tailed

Student's t- test. For all analyses, a P-value <0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All

statistical analyses were performed using OriginPro 2019b

(https://www.originlab.com/).

Results

Identification of prognostic

biomarkers in OSCC using integrated bioinformatics analysis of GEO

datasets

A total of 20,030 genes were identified from the

GSE246050 dataset using GEO2R analysis. Among these, 794 genes were

significantly upregulated and 1,331 were downregulated in the OSCC

samples compared to the healthy controls. To focus on the most

relevant molecular interactions, only genes with an interaction

degree of ≥10 in Cytoscape were retained for further analysis. This

filtering step yielded 318 upregulated and 221 downregulated genes

(Table SI), which were then

subjected to survival analysis using GEPIA. Among the upregulated

genes, 46 exhibited a significant association with OS, 28 with DFS,

and six genes were linked to both OS and DFS. Similarly, among the

downregulated genes, 41 genes were associated with OS, 24 with DFS,

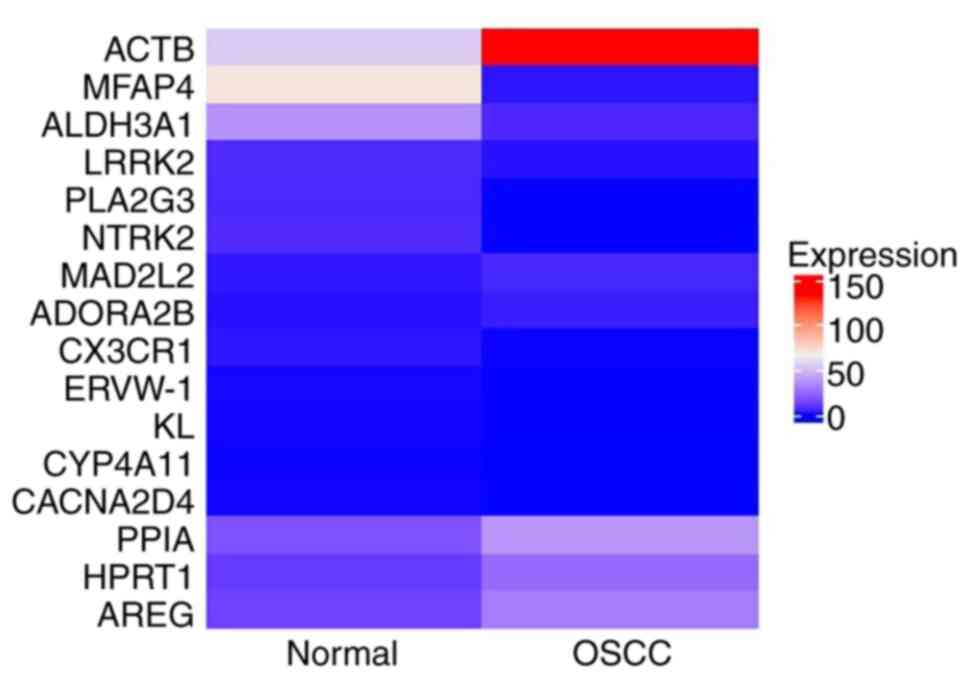

and ten genes displayed significance in both categories (Table SII). Heatmap analysis of genes

affecting both OS and DFS revealed six upregulated genes (ACTB,

HPRT1, PPIA, MAD2L2, AREG, ADORA2B) and ten downregulated genes

(MFAP4, ALDH3A1, CX3CR1, ERVW-1, CYP4A11, PLA2G3, LRRK2, NTRK2,

CACNA2D4, KL), as shown in Fig.

1. These differentially expressed genes, which affect both OS

and DFS, were identified as potential survival-associated

biomarkers for further investigation.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment

analysis of 16 survival-associated genes

GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses

were used to examine the biological functions and molecular

pathways of genes related to both OS and DFS. Enriched GO terms

were categorized into three groups, including biological process

(BP), cellular component (CC) and molecular function (MF) (Table SIII). Under the BP category, key

terms such as phosphorylation, cell activation and

leukocyte-mediated immunity were identified, which suggests their

involvement in immune response and cellular signaling. The CC

category featured the enrichment of presynapse, axon terminus,

neuron projection terminus and elastic fibers, suggesting that they

are involved in neural signaling and extracellular matrix

organization. Among the enriched terms in the MF category,

G-protein coupled receptor activity, chemokine binding, growth

factor binding, and fatty acid hydroxylase activity were

identified, indicating the variety of functions in the process of

signal transduction and metabolism. In addition, KEGG pathway

enrichment analysis revealed several signaling pathways related to

the target genes (Table SIV).

These were the MAPK signaling pathway, which is crucial in cell

proliferation and survival, the oxytocin signaling pathway, which

is involved in cellular communication and immune regulation, the

Hippo signaling pathway, which controls the size of the organs and

cell growth, and the pathways of bacterial invasion of epithelial

cells, which suggests its potential implication in

infection-associated oncogenesis. These results provide information

on the functional role of the identified genes and their role in

the key oncogenic and immune control pathways.

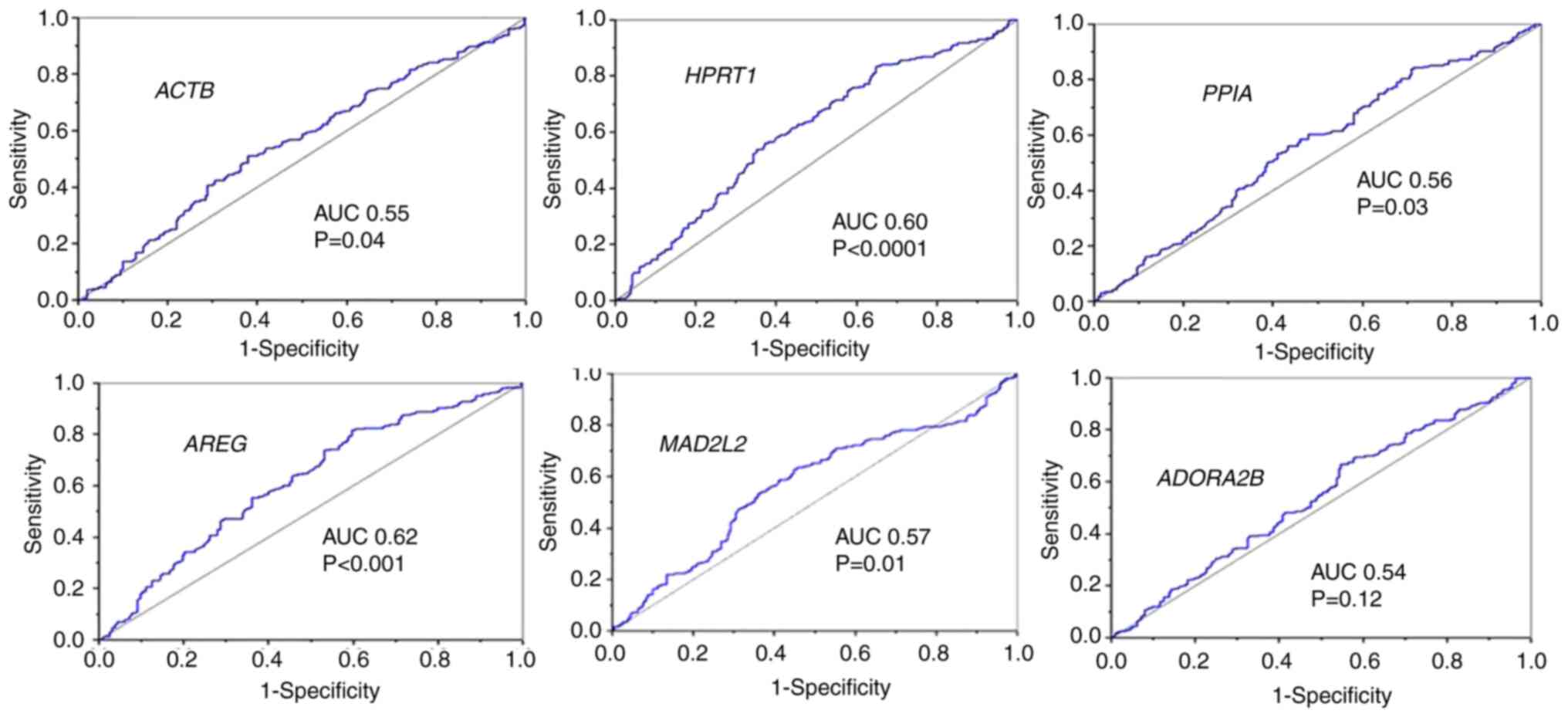

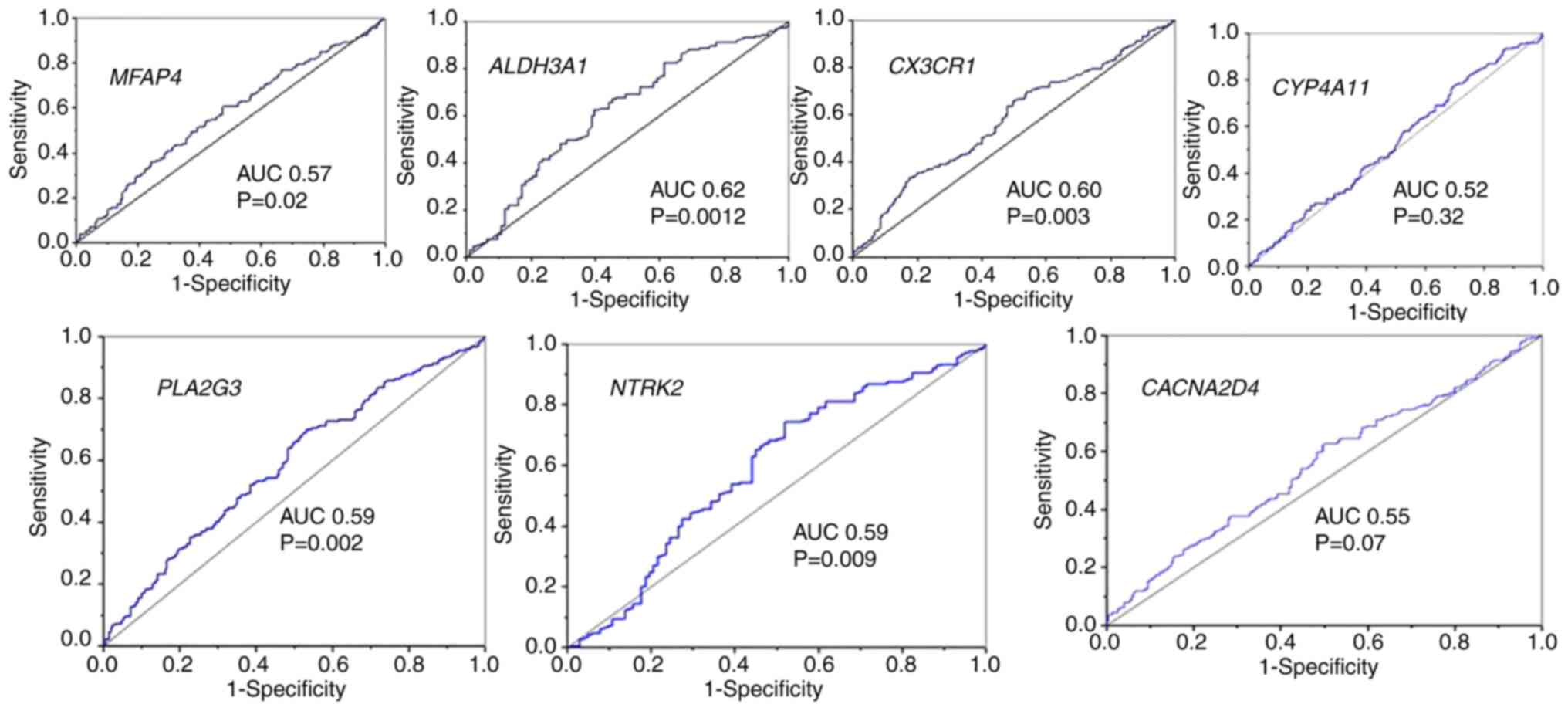

Validation of selected genes in the

cBioPortal database

The Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (TCGA,

Firehose Legacy) dataset was obtained from cBioPortal, and RSEM

expression data for genes associated with both OS and RFS were

extracted. Among the ten identified downregulated genes, only seven

(excluding ERVW-1, LRRK2 and KL) were available in

the cBioPortal dataset. All gene expression data were analyzed to

determine RSEM cut-off values for classifying high and low

expression levels for each gene. Patients were stratified into

high- and low-risk groups based on the cut-off value, determined as

the median ± 2SEM of gene expression level and on the basis of

their impact on overall survival. Out of the 13 genes initially

identified through survival analysis using cBioPortal data, seven

genes (ACTB, AREG, HPRT1, MFAP4, ALDH3A1, CYP4A11 and

CACNA2D4) demonstrated statistically significant

associations with either OS, RFS, or both, indicating their

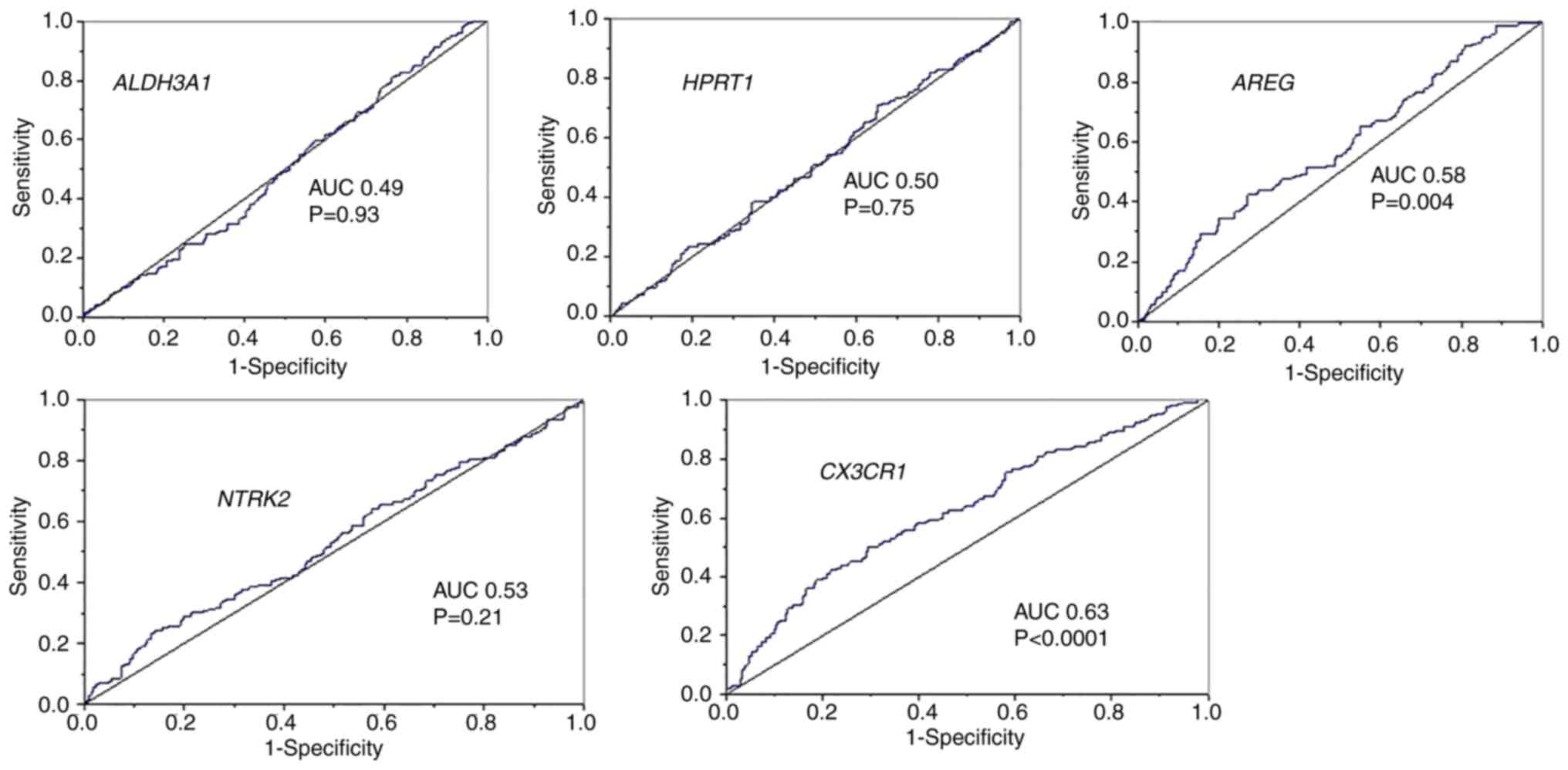

potential as prognostic markers in OSCC (Table II). Further evaluation through ROC

curve analysis revealed that only AREG, HPRT1,

ALDH3A1 and CX3CR1 had an AUC ≥0.60, suggesting their

moderate diagnostic value (Figs. 2

and 3). To assess the relevance of

these four genes in advanced disease, ROC analysis was performed

using T4-stage classification. Among the candidate genes,

AREG (upregulated) and CX3CR1 (downregulated)

exhibited the highest AUC values (~0.6), indicating relatively

better discrimination of advanced-stage OSCC compared to the others

(Fig. 4). Although their overall

diagnostic performance was moderate, their stage-specific

expression trends and biological links to tumor progression and

immune regulation supported their selection for detailed downstream

analysis (28-30).

| Table IISurvival analysis of the

survival-associated DEGs identified in oral cancer from the

cBioPortal database. |

Table II

Survival analysis of the

survival-associated DEGs identified in oral cancer from the

cBioPortal database.

| Gene symbol | Risk status (no. of

patients) | Survival/deceased

status (no. of patients) | P-value | DFS/RFS (no. of

patients) | P-value |

|---|

| Upregulated

genes |

|---|

| ACTB | High risk

(245) | OS (129); Deceased

(116) | 0.0062a | DFS (108); Recurred

(73) | 2.9662 |

|

CO:139086.35±130633.33 | Low risk (242) | OS (157); Deceased

(85) | | DFS (131); Recurred

(61) | |

| AREG | High risk

(234) | OS (121); Deceased

(113) | 0.0319a | DFS (97); Recurred

(76) | 0.0067a |

|

CO:789.911±514.86 | Low risk (234) | OS (144); Deceased

(90) | | DFS (124); Recurred

(53) | |

| HPRT1 | High risk

(244) | OS (121); Deceased

(123) | 0.0001a | DFS (97); Recurred

(74) | 0.0071a |

|

CO:964.36±884.77 | Low risk (238) | OS (159); Deceased

(79) | | DFS (135); Recurred

(57) | |

| PPIA | High risk

(235) | OS (132); Deceased

(103) | 0.3980 | DFS (109); Recurred

(73) | 0.2849 |

| | Low risk (218) | OS (131); Deceased

(87) | | DFS (108); Recurred

(57) | |

| MAD2L2 | High risk

(234) | OS (127); Deceased

(107) | 0.2077 | DFS (104); Recurred

(74) | 2.1575 |

|

CO:743.67±656.76 | Low risk (240) | OS (144); Deceased

(96) | | DFS (120); Recurred

(62) | |

| ADORA2B | High risk

(243) | OS (132); Deceased

(111) | 0.1296 | DFS (107); Recurred

(76) | 0.7371 |

|

CO:429.28±377.05 | Low risk (227) | OS (139); Deceased

(88) | | DFS (117); Recurred

(56) | |

| Downregulated

genes |

| MFAP4

CO:373.16±166.62 | High risk

(211) | OS (131); Deceased

(80) | 0.0363a | DFS (112); Recurred

(49) | 0.0062a |

| | Low risk (195) | OS (101); Deceased

(94) | | DFS (80); Recurred

(67) | |

| ALDH3A1 | High risk

(197) | OS (118); Deceased

(79) | 0.0054a | DFS (99); Recurred

(46) | 0.0312a |

|

CO:2152.11±184.34 | Low risk (94) | OS (40); Deceased

(54) | | DFS (32); Recurred

(29) | |

| CX3CR1 | High risk

(232) | OS (138); Deceased

(94) | 0.4080 | DFS (119); Recurred

(58) | 2.9959 |

| CO:25.29±16.56 | Low risk (214) | OS (119); Deceased

(95) | | DFS (96); Recurred

(69) | |

| CYP4A11,

CO:0.55±0.20 | High risk

(201) | OS (135); Deceased

(66) | 0.0026a | DFS (116); Recurred

(47) | 0.0074a |

| | Low risk (227) | OS (120); Deceased

(107) | | DFS (97); Recurred

(73) | |

| PLA2G3, | High risk

(220) | OS (133); Deceased

(87) | 0.1919 | DFS (116); Recurred

(51) | 3.4236 |

|

CO:140.43±66.95 | Low risk (212) | OS (115); Deceased

(97) | | DFS (93); Recurred

(63) | |

| NTRK2 | High risk

(210) | OS (126); Deceased

(84) | 0.1103 | DFS (106); Recurred

(50) | 0.0378a |

|

CO:1166.69±98.61 | Low risk (103) | OS (52); Deceased

(51) | | DFS (41); Recurred

(35) | |

|

CACNA2D4 | High risk

(233) | OS (145); Deceased

(88) | 0.0398a | DFS (123); Recurred

(62) | 0.1449 |

| CO:24.26±19.58 | Low risk (222) | OS (117); Deceased

(105) | | DFS (93); Recurred

(65) | |

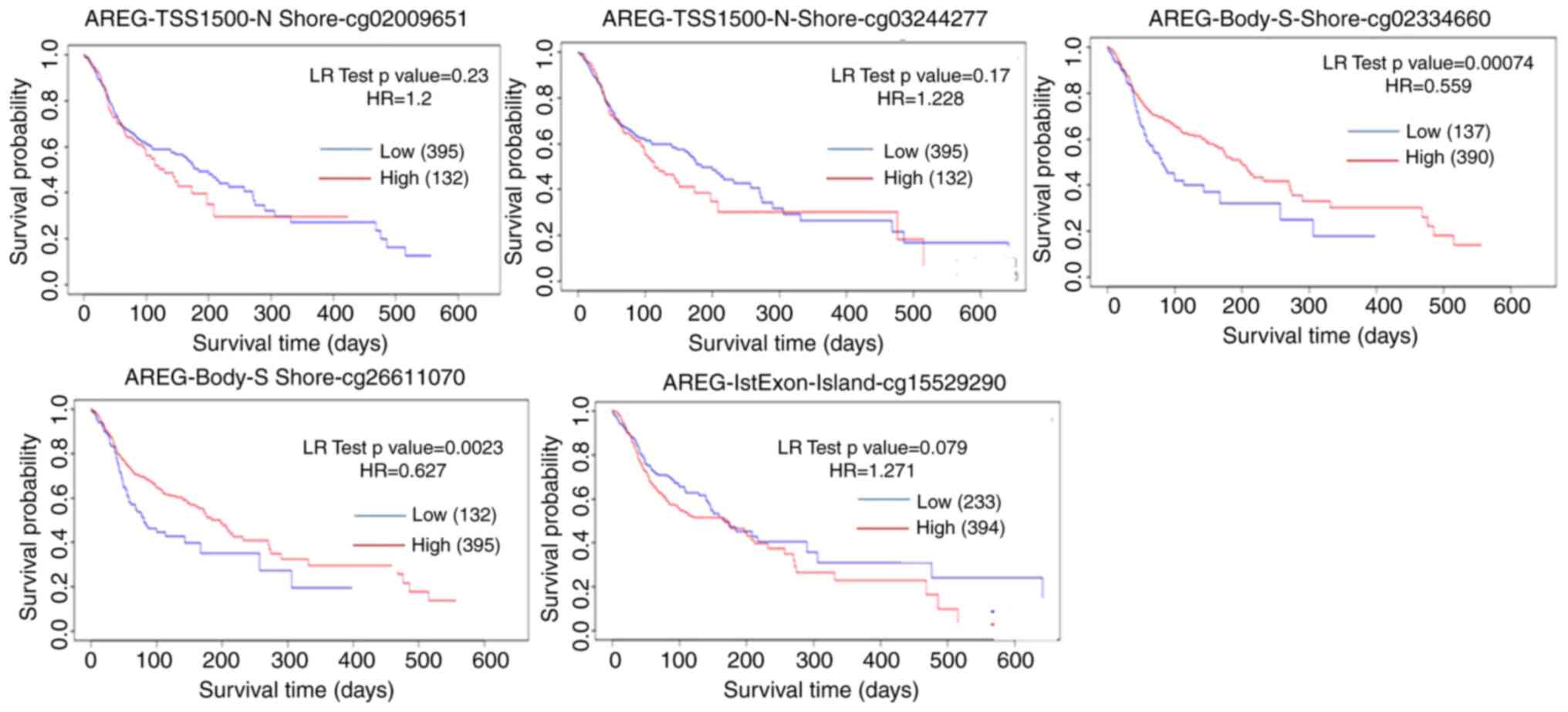

Association of AREG and CX3CR1 with

methylation probes

According to methylation profile data from the

MethSurv database, AREG is associated with five specific

methylation probes: cg02009651, cg03244277, cg02334660, cg26611070

and cg15529290 (Fig. 5). Among

these, methylation levels at CpG sites cg02009651, cg03244277 and

cg15529290 were negatively associated, whereas methylation at

cg02334660 and cg26611070 was associated with a favorable prognosis

correlation. Additionally, the analysis of the association between

these CpG sites and demographic/clinical factors including

ethnicity, race, body mass index (BMI), age and clinical events

revealed that cg02334660 and cg26611070 were positively association

with these variables, while cg15529290 (at 1st exon), cg02009651

and cg03244277 exhibited a negative association.

From the CX3CR1 methylation profile data from

the MethSurv database, CX3CR1 was shown to be associated

with 11 specific methylation probes: cg24130739, cg03296370,

cg19838154, cg01394385, cg26162331, cg00262061, cg05046858,

cg04498110, cg04569233, cg03341377 and cg24310395 (Fig. 6). Methylation-survival analyses

were performed using the MethSurv web tool, which fits Cox

proportional hazards models and reports hazard ratios, log-rank

test p-values, and a proportional hazards assumption test for each

CpG site (22). The log-rank test

has optimum power under the assumption of proportional hazard

rates. However, this assumption is often violated, particularly

when two survival curves cross each other. In Fig. 6, the late crossing of the survival

curve can be observed in the last plot. The authors were not able

to restrict the time range in the software to remove the late-stage

crossover. In addition, survival analyses for methylation were

obtained from the MethSurv platform using aggregate output; thus,

the application of alternative weighted tests was not possible.

Therefore, this may be a limitation of the present study. Among

these, methylation levels at cg24130739, cg03296370, cg19838154,

cg03341377, CpG sites were negatively associated, whereas

methylation at cg00262061, cg04498110, cg03341377, cg24310395,

cg04569233, cg05046858 and cg26162331 was associated with a

favorable prognosis. Additionally, the analysis of the association

between these CpG sites and demographic/clinical factors, including

ethnicity, race, BMI, age and clinical events revealed that

methylation at cg01394385, cg26162331, cg00262061 and cg05046858

were positively associated with these variables, while methylation

at cg24130739, cg03296370, cg19838154, cg04498110, cg04569233,

cg03341377 and cg24310395 exhibited a negative association

(Fig. 6).

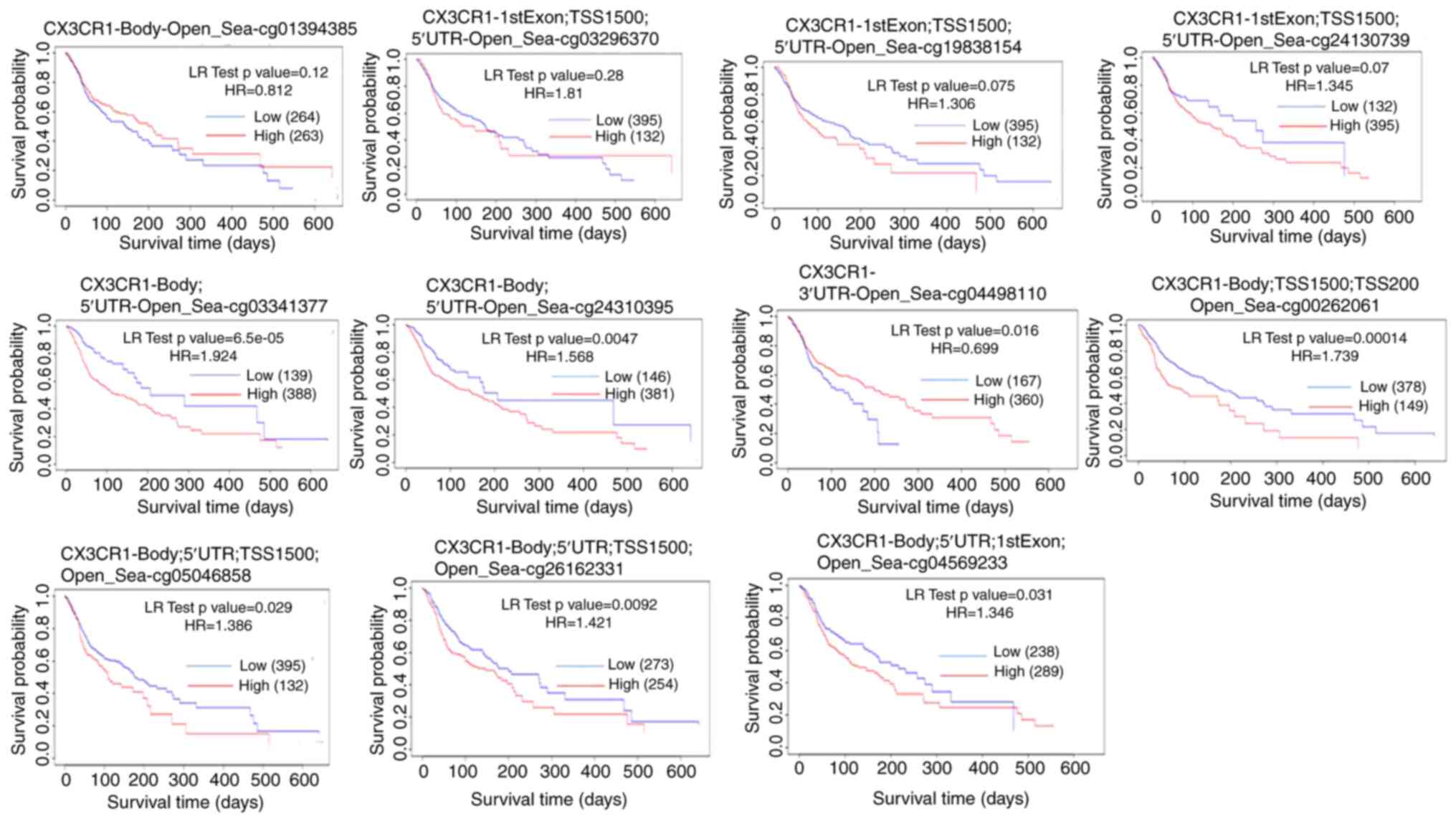

Copy number analysis

CNV is known to influence gene expression; however,

the association between CNVs of AREG and CX3CR1 and

their impact on gene expression in oral cancer remain to be fully

elucidated. Correlation analysis was performed using the HNSCC

dataset hosted on cBioPortal, based on patients with paired

copy-number and expression data (AREG, n=234; CX3CR1, n=524). In

the present study, the analysis revealed a significant effect of

CNV on gene expression (P<0.001; (Fig. 7). From a tumor biology perspective,

GISTIC2 analysis identified significant CNV events, which may

contribute to the observed differences in gene expression. To

further investigate this association, patients were stratified into

high- and low-risk groups based on a cut-off value determined as

the median ± SEM of gene expression levels. CNV analysis revealed

that copy number deletions were significantly associated with a

decreased gene expression of both AREG (high, 35/230; low,

71/232; P=0.000137) and CX3CR1 (high, 142/227; low, 163/213;

P=0.0058) in the cBioPortal dataset for HNSCC. However, no

significant differences were observed for copy number

amplifications (Table III).

| Table IIIDistribution of AREG and

CXC3CR1 copy number alterations in the high- and

low-expression groups. |

Table III

Distribution of AREG and

CXC3CR1 copy number alterations in the high- and

low-expression groups.

| | Deletion | No change | Amplification | Total |

|---|

| AREG | | | | |

|

High | 35 | 155 | 40 | 230 |

|

Low | 71 | 138 | 23 | 232 |

| CX3CR1 | | | | |

|

High | 142 | 80 | 5 | 227 |

|

Low | 163 | 46 | 4 | 213 |

To further validate the correlations between CNV and

gene expression, a linear regression model was applied using HNSCC

data from cBioPortal. The analysis revealed a weak correlation

between gene expression and copy number alterations for both AREG

(ρ=0.213, P=0.00098) and CX3CR1 (ρ=0.159, P=0.00029), as shown in

Fig. 7A and B. Although the correlation coefficients

indicate weak associations, they are statistically significant due

to the large sample size.

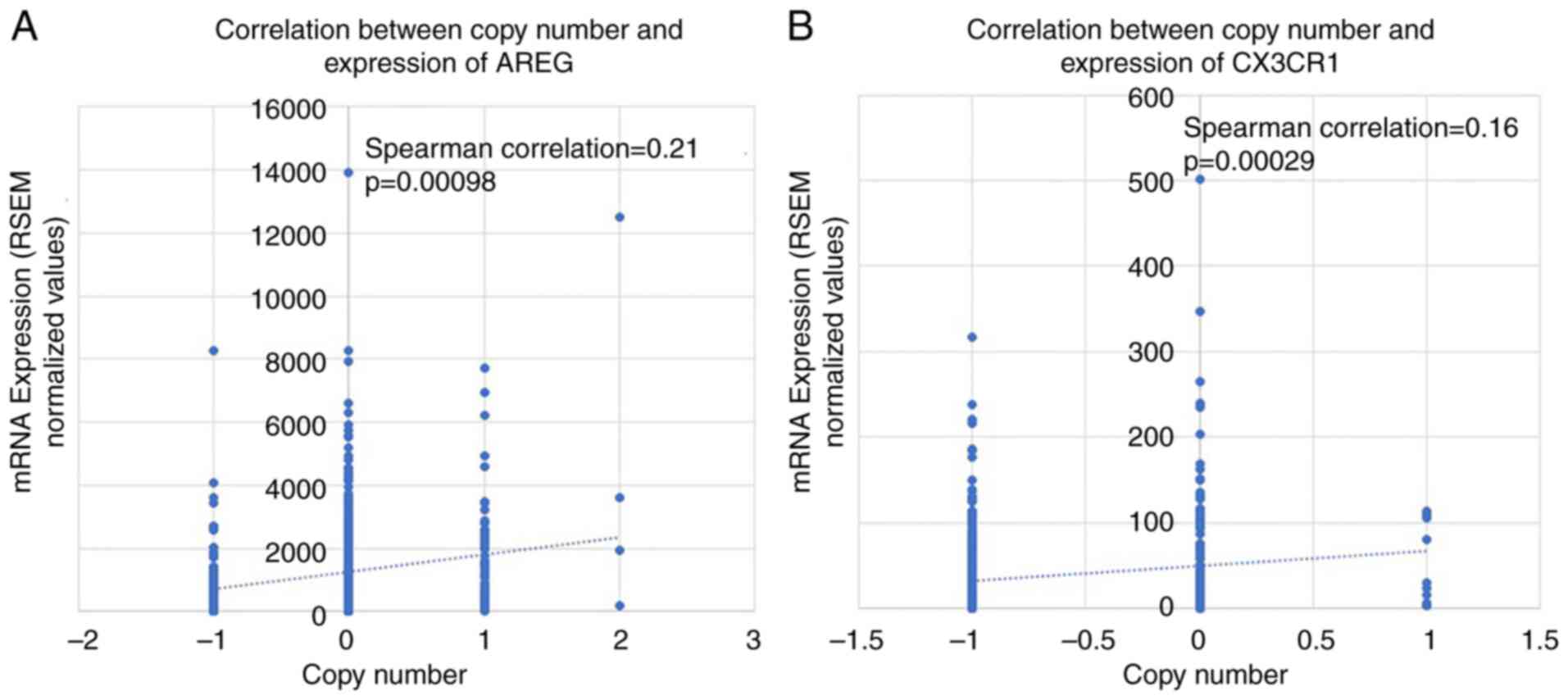

AREG and CX3CR1 expression are

associated with immune cell infiltration

The results of TIMER analysis suggested that

AREG and CX3CR1 exhibit differential immune

infiltration patterns in HNSCC. Notably, CX3CR1 appears to

be more strongly associated with neutrophil and CD4+

T-cell infiltration, while AREG is associated more with

CD8+ T-cells (Fig. 8).

These findings may provide insight into the immunomodulatory roles

of these genes in the HNSCC tumor microenvironment.

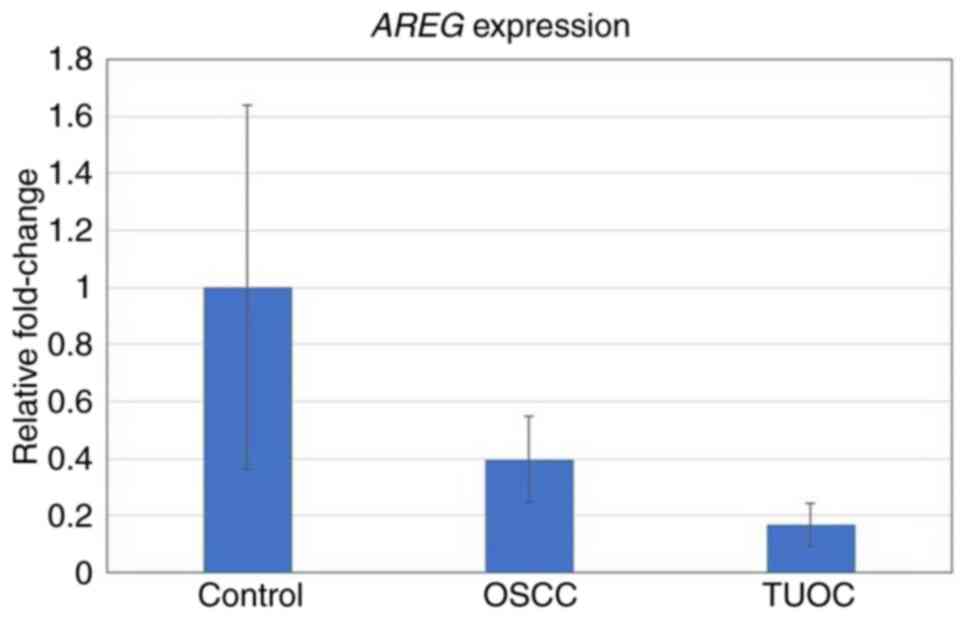

RT-qPCR analysis of AREG and CX3CR1 in

oral cancer

Subsequently, the expression levels of AREG

and CX3CR1 were evaluated in the blood samples of patients

with oral cancer. AREG expression was found to be reduced in

technically unresectable cases (TUOC, 0.16-fold change ± 0.08)

compared to patients with resectable cancer (0.39-fold change ±

0.15) (Fig. 9). By contrast,

CX3CR1 expression could not be reliably detected, as its Cq

value was >42, indicating levels below the measurable limit.

Phytochemicals as AREG potential

inhibitors

Of the 1,525 phytochemicals screened, 274 displayed

drug-like properties, indicating potential as drug candidates.

Similarly, Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA) identified 84 inhibitors

for AREG by co-relating drug sensitivity and gene expression.

Binding affinity scores were calculated for both 274 phytochemicals

and 84 AREG inhibitors. The (25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one for

phytochemical and vinorelbine for inhibitors demonstrate highest

binding affinity to AREG and therefore, were prioritized for

binding energy calculation. The list of top 20 phytochemicals and

inhibitors is presented in Tables

IV and V, respectively.

| Table IVList of top 20 phytochemical

inhibitors demonstrating binding affinity scores and hydrogen bond

interactions. |

Table IV

List of top 20 phytochemical

inhibitors demonstrating binding affinity scores and hydrogen bond

interactions.

| Name | Binding

affinity | Hydrogen bonds |

|---|

|

(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one | -7.5 | TYR-27 |

| Limonin | -7.1 | ASN-10, LYS-26 |

| 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)

naphthalic anhydride | -6.7 | TYR-27 |

|

Cucurbita-5_23(e)-diene-3-beta_7-beta_25-triol | -6.7 | HIS-30, LYS-9 |

| Betulinic_acid | -6.7 | LYS-9 |

| Caloxanthone_a | -6.7 | LYS-9 |

|

Garcimangosxanthone_b | -6.7 | GLN-17 |

|

2_3-dihydrowithaferin_a | -6.6 | CYS-38, LYS-37 |

|

Garcidepsidone_b | -6.6 | TYR-27, GLU-15 |

|

3-beta-acetoxy-8-beta-isobutyryloxyreynosin | -6.5 | TYR-27 |

|

8-prenyl_erythrinin_c | -6.5 | TYR-42, GLN-39,

CYS-38, LYS-37 |

| Caloxanthone_a | -6.5 | LYS- 9, GLU-15 |

|

Eichlerialactone | -6.5 | LYS-26 |

|

Garcimangosxanthone_c | -6.5 | GLY-17, CYS-25,

GLY-23 |

|

3-beta__12-dihydroxy-13-methyl-6_8_11_13-podocarpatetraen | -6.4 | TYR-27, ASN-10

GLY-7, LYS-26 |

|

Metrhylmitrekaurenate | -6.3 | TYR-27 |

| Xanthone V1 | -6.3 | LYS-9, GLU-32

TYR-27, GLU-29 |

| Escobarine A | -6.2 | GLY-7, LYS-9

TYR-27 |

| Garcidepsidone

A | -6.2 | TYR-27 |

|

2r_3r)-3_5-dihydroxy-7-methoxy_avanone | -6.1 | TYR-27 |

| Table VList of top 20 AREG inhibitors

demonstrating binding affinity scores and hydrogen bond

interactions. |

Table V

List of top 20 AREG inhibitors

demonstrating binding affinity scores and hydrogen bond

interactions.

| Ligand | Binding

affinity | Hydrogen bonds |

|---|

| Vinorelbine | -9.8 | LYS-9 |

| Docetaxel | -8.6 | GLU-29, TYR-27,

GLY-7, SER-6 |

| Tipifarnib | -8.1 | TYR-27 |

| Tanespimycin | -8.1 | GLU-32, TYR-27 |

| AKT inhibitor

VIII | -7.9 | SER-5, GLU-15 |

| AZ628 | -7.8 | GLN-39, GLN-40,

CYS-38, TYR-42, GLY-44 |

| A-770041 | -7.7 | HIS-22, LYS-26,

ASN-10 |

|

S-Trityl-L-cysteine | -7.6 | TYR-27 |

| OSU-03012 | -7.6 | LYS-9, GLU-29 |

| Nilotinib | -7.5 | LYS-9, TYR-27 |

| LY317615 | -7.5 | GLU-15, TYR-27 |

| Etoposide | -7.5 | ASN-10, ASN-13,

CYS-25 |

| GSK1904529A | -7.3 | LYS-26 |

| BMS-509744 | -7.2 | LYS-9, VAL-34 |

| ERK5-IN-1 | -7.2 | GLN-17, CYS-25 |

| PHA-665752 | -7.2 | ASN-13, CYS-12,

CYS-25 |

| Doramapimod | -7.1 | SER-5, SER-6 |

| FR-180204 | -7.0 | GLY-44, CYS-38,

GLN-39 |

| Cyclopamine | -7.0 | TYR-27 |

| BMS-708163 | -7.0 | GLU-32 |

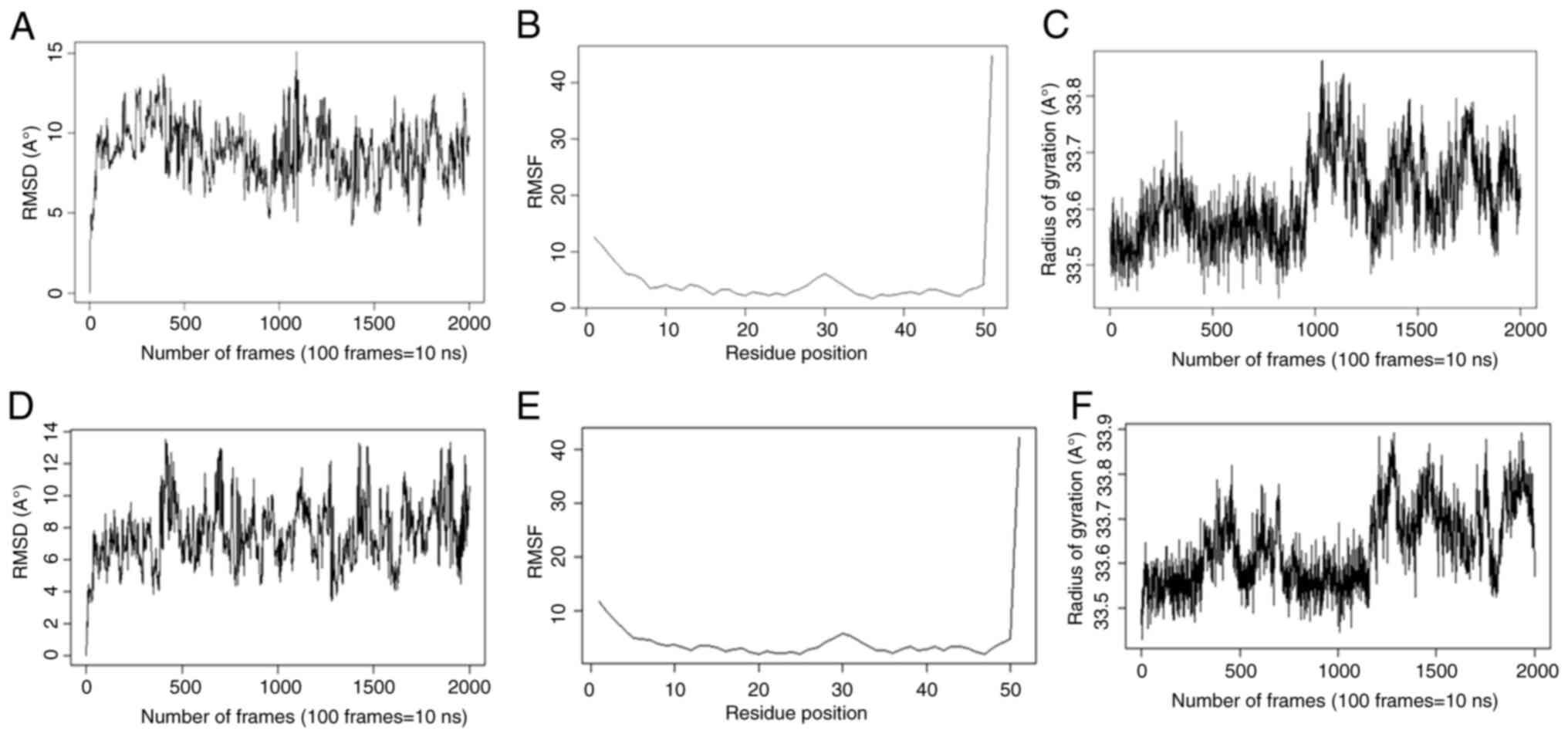

Molecular docking and molecular

dynamics simulation

Docking analysis revealed the highest binding

affinity between AREG- (25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one and

AREG-vinorelbine (Tables IV and

V).

The stability and compactness of these complexes

were assessed through RMSD and radius of gyration (Rg), as

demonstrated in Table VI and

Fig. 10. The RMSD and Rg did not

fluctuate for the 200 nsec, confirming the stability of the 3D

protein structure during molecular dynamics simulations.

Additionally, the RMSF was stable over 200 ns of simulation,

suggesting least residue-level fluctuations. These findings

strongly support the stable interaction of the complexes during the

200 nsec simulation, confirming their structural stability and

potential effectiveness.

| Table VIComparative analysis of AREG-

(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one and AREG-vinorelbine. |

Table VI

Comparative analysis of AREG-

(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one and AREG-vinorelbine.

| SN | RMSD (A˚) | Rg (A˚) | RMSF (nm) |

|---|

| AREG | 5.33±0.03 | 33.59±0.002 | 3.15±0.29 |

|

(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one | 1.17±0.001 | 4.79±0.001 | 0.41±0.04 |

| Vinorelbine | 3.40±0.01 | 5.35±0.001 | 2.27±0.10 |

| AREG-

(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one | 7.61±0.04 | 33.64±0.002 | 3.76±0.27 |

|

AREG-vinorelbine | 8.85±0.04 | 33.61±0.002 | 3.93±0.31 |

The results also revealed that the binding energy

between AREG-vinorelbine was -15.26 kcal/mol, while the binding

energy between AREG- (25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one was +3.6 kcal/mol

(Table VII). These results

suggest a strong binding interaction of vinorelbine with AREG in

comparison to (25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one.

| Table VIIFree binding energy of

(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one and vinorelbine with AREG. |

Table VII

Free binding energy of

(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one and vinorelbine with AREG.

| SN | Electrostatic

energy (kcal/mol) | Vander Waals energy

(kcal/mol) | Free binding energy

of (ΔG) AREG-drug complex (kcal/mol) |

|---|

|

(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one | -47.24±0.01

SEM | 5.69±0.02 SEM | NA |

| Vinorelbine | 105.55±0.03

SEM | 33.40±0.03 SEM | NA |

| AREG | -351.46±1.59

SEM | -116.96±0.24

SEM | NA |

|

AREG-(25s)-neospirost-4-en-3-one | -326.85±1.80

SEM | -115.10±0.25

SEM | +3.6 |

|

AREG-Vinorelbine | -400.60±2.26

SEM | -116.802±0.29

SEM | -15.26 |

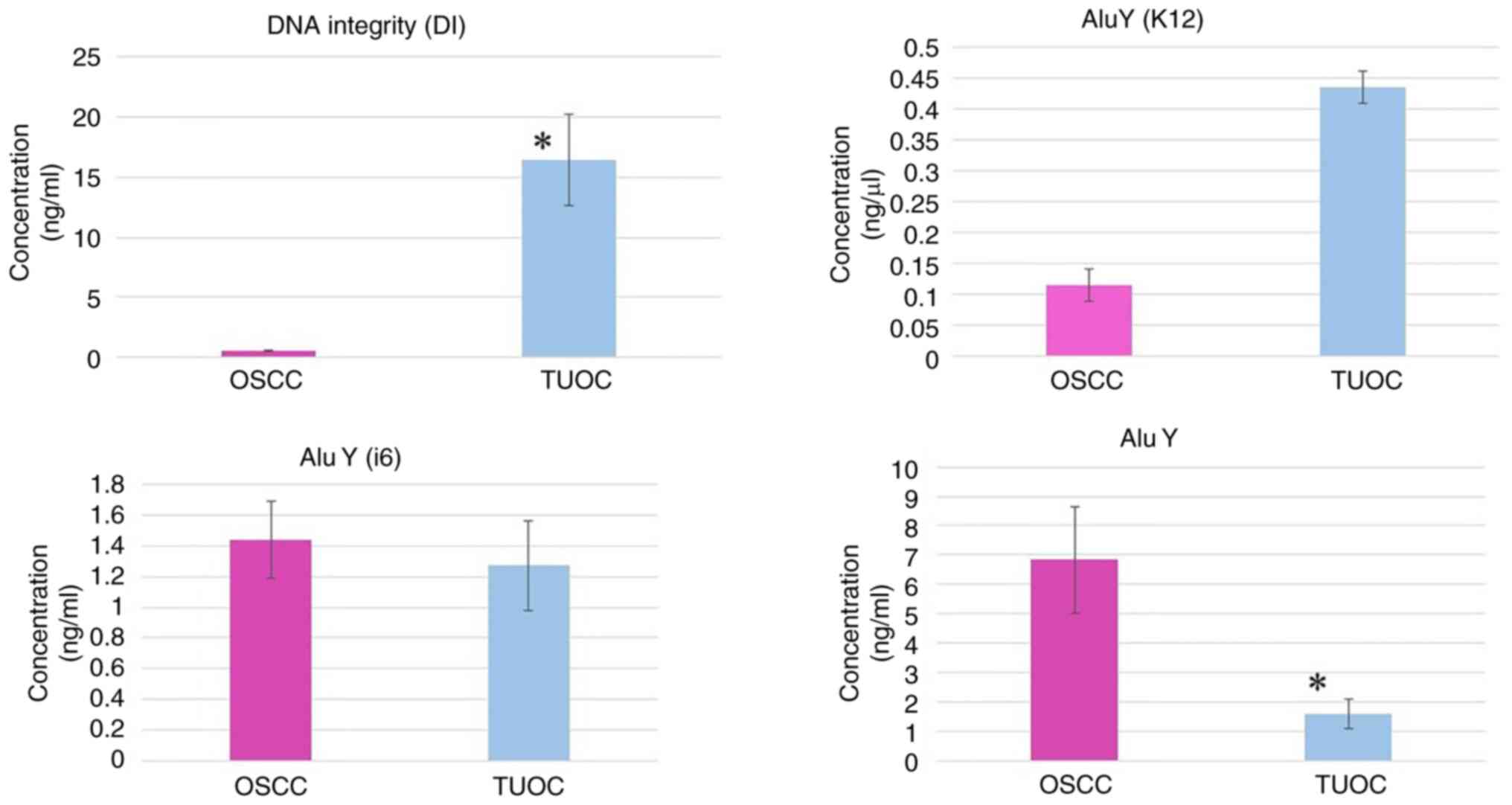

Analysis of Alu family expression in

patients with oral cancer and TUOC

In the present study, Alu DNA levels were quantified

in serum samples from patients with resectable oral cancer and TUOC

to evaluate their potential as biomarkers. The DNA integrity (DI)

ratio, measured using Alu115/Alu247, was significantly elevated in

patients with TUOC (16.46±3.82) compared to patients with

resectable OSCC (0.55±0.11), with a P-value of 0.0007, indicating

increased genomic instability in advanced-stage disease (Fig. 11). The analysis of AluY

subfamilies revealed a non-significant increase in AluY (K12)

expression in patients with TUOC (0.43±0.22) vs. patients with

resectable OSCC (0.11±0.03; P=0.1715), and a similar trend was

observed for AluY (i6) (TUOC, 1.44±0.25; resectable OSCC,

1.27±0.29; P=0.6589) (Fig. 11).

Of note, total AluY family expression, encompassing all subtypes,

was significantly higher in patients with resectable OSCC

(6.83±1.83) than in those with TUOC (1.60±0.51; P=0.0143) (Fig. 11). These results suggest that

while individual AluY subfamilies may not distinctly reflect

disease stage, elevated DI ratios and changes in total AluY

expression may serve as potential indicators of disease progression

and early-stage tumor activity in OSCC.

Discussion

OSCC is an aggressive malignancy and has low chances

of survival because of late diagnosis, resistance to therapy and

lack of effective molecular biomarkers. Although previous research

has examined the significance of genomic modifications, epigenetic

modifications, and immune responses to define possible diagnostic

and therapeutic targets, there is limited clinical translation of

these results (31). The present

study used an integrative strategy that consisted of

bioinformatics, transcriptomic profiling, epigenetic analysis,

immune infiltration evaluation, and molecular docking to provide

further information on the molecular landscape of OSCC.

Previous studies have reported frequently

dysregulated genes in oral cancer, such as TP53, EGFR,

NOTCH1 and CCND1 that are associated with proliferation,

apoptosis and resistance to treatment (32,33).

The present study demonstrated that AREG and CX3CR1

were the most relevant genes associated with progressive OSCC,

which are associated with immune infiltration and poor prognosis

indicators. The clinical importance of AREG is further supported by

a study conducted by Bourova-Flin et al (28), which reported that high expression

of AREG, along with Cyclin A1 and

DDX20/Gemin3, was indicative of aggressive OSCC and

correlated with unfavorable clinical outcomes. This reinforces the

observation that AREG may contribute to tumor progression

and immune-related changes in advanced disease. Equally, CX3CL1 has

also been demonstrated to facilitate the migration and invasion of

OSCC cells by increasing ICAM-1 expression via CX3CR1 receptor,

which underscores its contribution to tumor invasiveness (34). These reports are consistent with

the findings of the present study, in which CX3CR1

expression was modulated in terms of immune cell invasion and

disease severity. Collectively, these data support the notion that

AREG and CX3CR1 are potentially useful biomarkers to

detect and describe OSCC cases. Nonetheless, the diagnostic and

prognostic ability of both genes seems to be limited as both of

them showed only moderate AUC values (~0.6) in the ROC analyses.

Thus, the results are to be considered as preliminary, and further

research is required to confirm their applicability to clinical

settings in larger patient groups.

The epigenetic modifications including CNVs and DNA

methylation are the focus of OSCC development. In line with the

earlier reports that reported promoter hypermethylation-induced

silencing of tumor suppressors, such as CDKN2A, DAPK1 and

MGMT (35,36), the present study reported

hypermethylation of AREG and CX3CR1, with certain CpG

sites being associated with poor survival. CNV analysis identified

deletions of CX3CR1 that were associated with decreased

expression, indicating its tumor-suppressive activity, whereas

AREG was not affected by deletion of CNV, indicating further

epigenetic or post-transcriptional regulation. On the immunological

front, previous research has linked CD8+ T-cell

infiltration with improved prognosis, and increased Tregs or MDSCs

with poorer outcomes (37,38). The present study demonstrated that

AREG and CX3CR1 were associated with CD8+

T-cells and neutrophils and CD4+ T-cells respectively,

which indicated differential roles in immune modulation. Taken

together, these results support previous data of chemokine and

growth factor implication by modulating tumor microenvironment in

OSCC and emphasize their role in the regulation of the epigenome,

as well as tumor-immune interactions (39,40).

In a previous study on non-small cell lung cancer

and HNSCC, changes in serum levels of EGFR and its ligands, such as

AREG, were described, and lower levels of AREG

expression were found in serum samples of patients (41). These findings are in line with the

findings of the present study, which also revealed the reduced

expression of AREG in the blood of patients with TUOC.

Although the present study was not able to do tissue-level

validation, several previous studies have established that

AREG is overexpressed in OSCC tissues (28,29,42,43).

This, along with the observation of lower AREG levels in

circulation in the present study, confirms the hypothesis of the

‘dual faces’, in which local tumor upregulation is accompanied by

lower systemic levels. These findings also indicate that local

tumor expression can be more useful in prognosis compared to

circulating levels. CX3CR1 was, however, not detectable in

serum samples, presumably due to very low levels of expression or

degradation, suggesting that tissue-based analysis can be more

informative on this marker.

Transposable elements, particularly Alu elements,

are critical in the progression of cancer (44). Consistent with previous studies,

the present study also discovered that the DNA integrity ratio

(Alu115/Alu247) was significantly higher in patients with TUOC and

indicated more genomic instability (45,46).

Whereas AluY (K12) expression was more elevated in TUOC, the total

expression of the AluY family was more elevated in resectable OSCC,

indicating stage-specific roles of Alu subfamilies. The results are

in line with previous research demonstrating that some Alu

subfamilies differ in expression across cancer types, which

supports their possible use as biomarkers of disease staging and

monitoring (45).

Due to the drawbacks of traditional OSCC therapy,

natural compounds have become the focus of interest as possible

anticancer agents as they can regulate oxidative stress,

inflammation and apoptosis pathways (47,48).

The present study identified 274 drug-like compounds; however, only

vinorelbine, an approved drug, exhibited a strong and stable

binding with AREG in molecular docking and molecular dynamics

simulations. These results suggest that vinorelbine has a higher

therapeutic potential compared to the identified natural compounds.

Although limited by a small validation cohort and reliance on

bioinformatics data, the results are exploratory and indicate that

AREG, CX3CR1 and Alu elements can be considered as a

potential therapeutic targets and biomarkers in OSCC. To validate

these findings and enhance biomarker-based treatment strategies,

larger, multi-center and functional studies are required.

Overall, the analyses of genomic, epigenetic,

immunological and transposable elements were combined in the

present study to identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets

in OSCC. The results enhance the current understanding of the

molecular mechanisms of OSCC and may be applied to designing the

individual treatment plans in accordance with the profile of

biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

List of upregulated and downregulated

genes.

DEGs associated with OS and RFS in

oral cancer.

GO function and pathway enrichment

analysis of common genes in OSCC.

KEGG pathways analysis of DEGs genes

in OSCC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the intramural

funding from Parul University, Vadodara, India (grant no.

RDC/IMSL/213).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

All authors (NK, CJ, MP and RG) contributed to the

conception and design of the study. Material preparation, data

collection and analysis were performed by NK and CJ. Molecular

dynamics simulation and qPCR were performed by MP. NK and RG

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. The first draft of

the manuscript, editing and supervision was performed by RG, and

all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the

Ethics Committee of Parul University (Approval no.

PUIECHR/PIMSR/00/081734/5307) and was conducted in accordance with

institutional ethical standards and regulatory guidelines. All

patients signed an informed consent form, and all procedures

performed in this study were in accordance with the principles for

medical research of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later

amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Shimojukkoku Y, Nguyen PT, Ishihata K,

Ishida T, Kajiya Y, Oku Y, Kawaguchi K, Tsuchiyama T, Saijo H,

Shima K and Sasahira T: Role of early growth response-1 as a tumor

suppressor in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Discov Oncol.

15(714)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Kijowska J, Grzegorczyk J, Gliwa K, Jędras

A and Sitarz M: Epidemiology, diagnostics, and therapy of oral

cancer-update review. Cancers (Basel). 16(3156)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yosefof E, Edri N, Kurman N, Bachar G,

Shpitzer T, Mizrachi A and Popovtzer A: The role of adjuvant

radiotherapy for early-stage oral cavity cancer with minor adverse

features; A single institute experience. Head Neck. 47:1839–1847.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Caputo WL, de Souza MC, Basso CR, Pedrosa

VA and Seiva FRF: Comprehensive profiling and therapeutic insights

into differentially expressed genes in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cancers (Basel). 15(5653)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zakari S, Niels NK, Olagunju GV, Nnaji PC,

Ogunniyi O, Tebamifor M, Israel EN, Atawodi SE and Ogunlana OO:

Emerging biomarkers for non-invasive diagnosis and treatment of

cancer: A systematic review. Front Oncol. 4(1405267)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ye M, Huang X, Wu Q and Liu F: Senescent

stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment: Victims or

accomplices? Cancers (Basel). 15(1927)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lakshminarasimhan R and Liang G: The role

of DNA methylation in cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 945:151–172.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yi L, Wu G, Guo L, Zou X and Huang P:

Comprehensive analysis of the PD-L1 and immune infiltrates of m6A

RNA methylation regulators in head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 21:299–314. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Jiang Y, Zong W, Ju S, Jing R and Cui M:

Promising member of the short interspersed nuclear elements (Alu

elements): Mechanisms and clinical applications in human cancers. J

Med Genet. 56:639–645. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chen LL and Yang L: ALUternative

regulation for gene expression. Trends Cell Biol. 27:480–490.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Masson E, Maestri S, Bordeau V, Cooper DN,

Férec C and Chen JM: Alu insertion-mediated dsRNA structure

formation with pre-existing Alu elements as a disease-causing

mechanism. Am J Hum Genet. 111:2176–2189. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wang ZY, Ge LP, Ouyang Y, Jin X and Jiang

YZ: Targeting transposable elements in cancer: Developments and

opportunities. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1879(189143)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lehle S, Emons J, Hack CC, Heindl F, Hein

A, Preuß C, Seitz K, Zahn AL, Beckmann MW, Fasching PA, et al:

Evaluation of automated techniques for extraction of circulating

cell-free DNA for implementation in standardized high-throughput

workflows. Sci Rep. 13(373)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Choudhari AS, Mandave PC, Deshpande M,

Ranjekar P and Prakash O: Phytochemicals in cancer treatment: From

preclinical studies to clinical practice. Front Pharmacol.

10(1614)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Othman B, Beigh S, Albanghali MA, Sindi

AAA, Shanawaz MA, Ibahim MAEM, Marghani D, Kofiah Y, Iqbal N and

Rashid H: Comprehensive pharmacokinetic profiling and molecular

docking analysis of natural bioactive compounds targeting oncogenic

biomarkers in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 15(5426)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Patel MS, Sinngh P, Gandupalli L and Gupta

R: Identification and evaluation of survival-associated common

chemoresistant genes in cancer. Biomed Biotechnol Res J. 8:320–327.

2024.

|

|

18

|

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C and

Zhang Z: GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression

profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res.

45(W1):W98–W102. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T and Zhang Z:

GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling

and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(W1):W556–W560.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Gu Z, Eils R and Schlesner M: Complex

heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional

genomic data. Bioinformatics. 32:2847–2849. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Liao Y, Wang J, Jaehnig EJ, Shi Z and

Zhang B: WebGestalt 2019: Gene set analysis toolkit with revamped

UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(W1):W199–W205. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Modhukur V, Iljasenko T, Metsalu T, Lokk

K, Laisk-Podar T and Vilo J: MethSurv: A web tool to perform

multivariable survival analysis using DNA methylation data.

Epigenomics. 10:277–288. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q,

Li B and Liu XS: TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48(W1):W509–W514. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kingsley JP, Pranay G, Priya A and

Chandrakumar MJ: Human papilloma virus testing in oral squamous

cell carcinoma in Southern India: A case-control study. Current

Medical Issues. 19:12–18. 2021.

|

|

25

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hubley R, Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR,

Jones TA, Bao W, Smit AF and Wheeler TJ: The Dfam database of

repetitive DNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 44(D1):D81–D89.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Dallakyan S and Olson AJ: Small-molecule

library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol.

1263:243–250. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bourova-Flin E, Derakhshan S, Goudarzi A,

Wang T, Vitte AL, Chuffart F, Khochbin S, Rousseaux S and

Aminishakib P: The combined detection of Amphiregulin, Cyclin A1

and DDX20/Gemin3 expression predicts aggressive forms of oral

squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 125:1122–1134.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gao J, Ulekleiv CH and Halstensen TS:

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor-ligand based molecular

staging predicts prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

partly due to deregulated EGF-induced amphiregulin expression. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 35(151)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

He C, Wu Y, Nan X, Zhang W, Luo Y, Wang H,

Li M, Liu C, Liu J, Mou X and Liu Y: Induction of CX3CL1 expression

by LPS and its impact on invasion and migration in oral squamous

cell carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 12(1371323)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ravindran S, Ranganathan S, R K, J N, A S,

Kannan SK, Prasad K D, Marri J and K R: The role of molecular

biomarkers in the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment

stratification of oral squamous cell carcinoma: A comprehensive

review. J Liq Biopsy. 7(100285)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kunesch K: GATA3-expressing regulatory T

cells accumulate in response to early cancerous changes via

TCR-dependent local proliferation: Dissertation, RWTH Aachen

University, 2024.

|

|

33

|

Gintoni I, Vassiliou S, Chrousos GP and

Yapijakis C: Review of disease-specific microRNAs by strategically

bridging genetics and epigenetics in oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Genes (Basel). 14(1578)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wu CY, Peng PW, Renn TY, Lee CJ, Chang TM,

Wei AI and Liu JF: CX3CL1 induces cell migration and invasion

through ICAM-1 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. J

Cell Mol Med. 27:1509–1522. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Izumi T, Rychahou P, Chen L, Smith MH and

Valentino J: Copy number variation that influences the ionizing

radiation sensitivity of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cells.

12(2425)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Agarwal N and Jha AK: DNA hypermethylation

of tumor suppressor genes among oral squamous cell carcinoma

patients: A prominent diagnostic biomarker. Mol Biol Rep.

52(44)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Kondoh N and Mizuno-Kamiya M: The role of

immune modulatory cytokines in the tumor microenvironments of head

and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancers (Basel).

14(2884)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Fu C and Jiang A: Dendritic cells and CD8

T cell immunity in tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol.

9(3059)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Sahingur SE and Yeudall WA: Chemokine

function in periodontal disease and oral cavity cancer. Front

Immunol. 6(214)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Mesgari H, Esmaelian S, Nasiri K,

Ghasemzadeh S, Doroudgar P and Payandeh Z: Epigenetic regulation in

oral squamous cell carcinoma microenvironment: A comprehensive

review. Cancers (Basel). 15(5600)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Lemos-Gonzalez Y, Rodríguez-Berrocal FJ,

Cordero OJ, Gómez C and Páez de la Cadena M: Alteration of the

serum levels of the epidermal growth factor receptor and its

ligands in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and head and

neck carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 96:1569–1578. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Li M, Wei Y, Huang W, Wang C, He S, Bi S,

Hu S, You L and Huang X: Identifying prognostic biomarkers in oral

squamous cell carcinoma: An integrated single-cell and bulk RNA

sequencing study on mitophagy-related genes. Sci Rep.

14(19992)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhou J, Xu Y, Li Y, Zhang Q, Zhong L, Pan

W, Ji K, Zhang S, Chen Z, Liu Y, et al: Cancer-associated

fibroblasts derived amphiregulin promotes HNSCC progression and

drug resistance of EGFR inhibitor. Cancer Lett.

622(217710)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Park MK, Lee JC, Lee JW and Hwang SJ: Alu

cell-free DNA concentration, Alu index, and LINE-1 hypomethylation

as a cancer predictor. Clin Biochem. 94:67–73. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Nair MG, Ramesh RS, Naidu CM, Mavatkar AD,

V P S, Ramamurthy V, Somashekaraiah VM, C E A, Raghunathan K,

Panigrahi A, et al: Estimation of ALU repetitive elements in plasma

as a cost-effective liquid biopsy tool for disease prognosis in

breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 15(1054)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Lehner J, Stötzer OJ, Fersching D, Nagel D

and Holdenrieder S: Circulating plasma DNA and DNA integrity in

breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin

Chim Acta. 425:206–211. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Farhan M: Revisiting the

antioxidant-prooxidant conundrum in cancer research. Med Oncol.

41(179)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Huang J, Xu Y, Wang Y, Su Z, Li T, Wu S,

Mao Y, Zhang S, Weng X and Yuan Y: Advances in the study of

exosomes as drug delivery systems for bone-related diseases.

Pharmaceutics. 15(220)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|