1. Introduction

Viruses, as obligate intracellular parasites,

represent a significant yet often overlooked component of the oral

microbiome, particularly within the context of periodontal health

and disease. Viruses are submicroscopic infectious agents composed

of genetic material enclosed within a protein shell, often

enveloped by a lipid membrane. These entities are incapable of

self-replication and rely entirely on the host cellular machinery

for propagation (1). Despite their

minimalistic structure, viruses are greatly efficient in hijacking

host mechanisms, often resulting in chronic, latent, or even

oncogenic infections. Within the oral cavity, viruses have been

identified in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF), periodontal pockets

and oral mucosal tissues, indicating their active involvement in

the periodontal microenvironment (2).

Traditionally, periodontal diseases have been viewed

as bacteria-driven inflammatory conditions. However, the emerging

understanding of the oral microbiome has revealed a complex

interplay between host immunity and polymicrobial communities,

including viruses. Unlike bacteria, viruses exert their influence

primarily by modulating immune responses and enhancing the

pathogenicity of resident bacteria (3). Persistent infections, immune

suppression and viral reactivation are all mechanisms through which

viruses can exacerbate periodontal inflammation and accelerate the

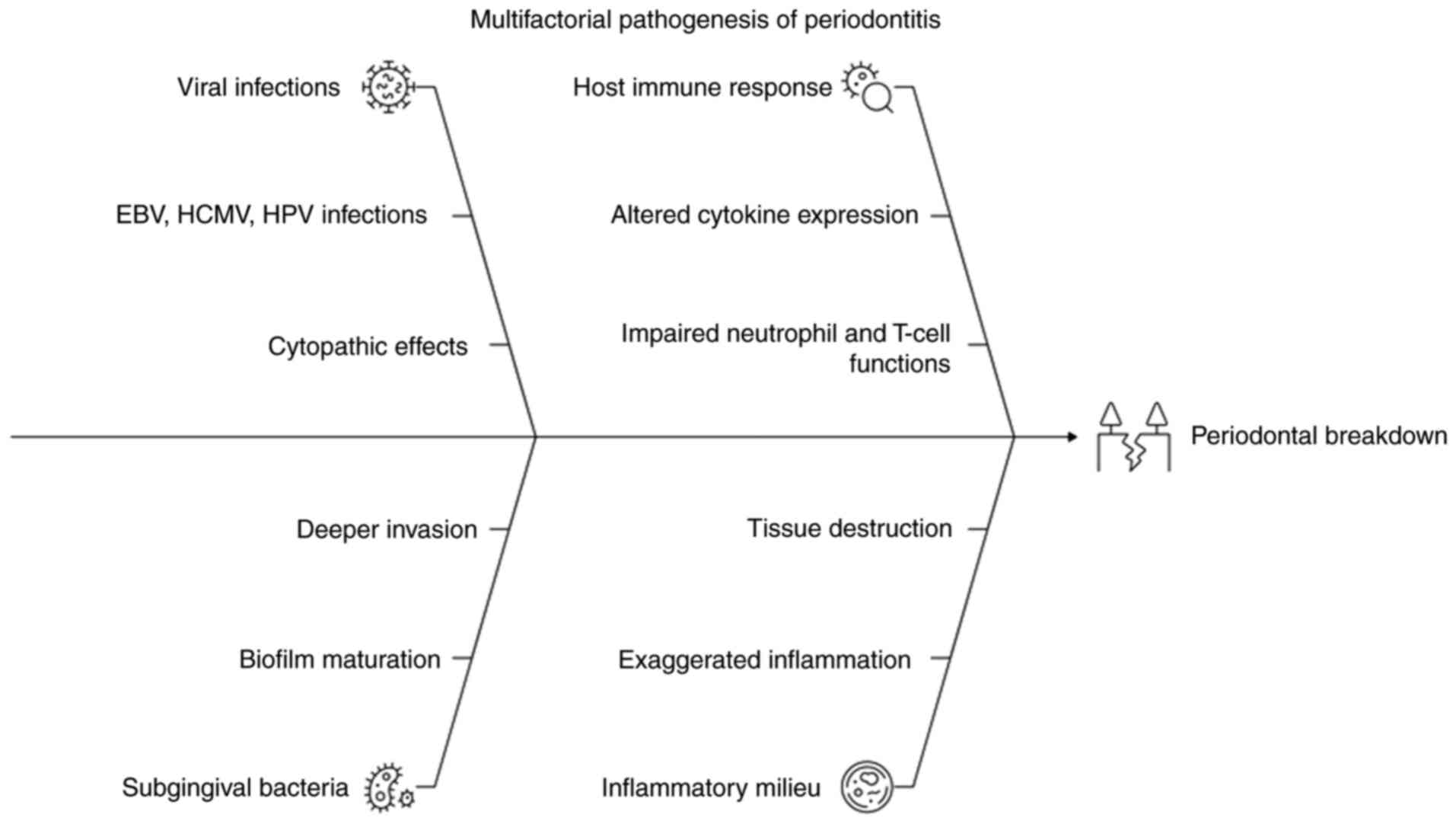

breakdown of periodontal tissues (4). A schematic illustration summarizing

viral-host-bacterial interactions in periodontal pathogenesis is

provided in Fig. 1.

Epidemiological studies have (5-7)

reported herpesvirus detection in 30-60% of chronic periodontitis

sites, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human cytomegalovirus

(HCMV) frequently isolated from deep pockets (8,9).

Previous meta-analyses have suggested a several-fold higher

prevalence of these viruses in diseased sites compared to healthy

controls (10,11).

2. Literature search methods

A structured literature search was conducted across

the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar databases.

The search strategy used combinations of the following key words

and Boolean operators: ‘viruses AND periodontitis’, ‘herpesviruses

AND periodontal disease’, ‘HIV oral manifestations’,

‘viral-bacterial synergism’, ‘periodontal virome’, ‘SARS-CoV-2 and

oral health’ and ‘salivary viral biomarkers’. The search included

articles published between 1990 and 2025, and was restricted to

English-language publications. Both clinical trials, observational

studies, molecular studies and review articles were included,

whereas editorials, non-peer reviewed sources, and articles lacking

relevance to viral periodontal involvement were excluded. Of note,

two authors (AS and VRA) independently screened titles and

abstracts, followed by full-text assessment. Data extraction

focused on viral mechanisms, immune modulation, diagnostic

approaches, clinical manifestations and therapeutic strategies. Any

disagreement was resolved by consensus.

3. Evolution and classification of

viruses

The evolutionary origin of viruses is a subject of

ongoing debate. Three prominent theories provide potential

explanations. The virus-early hypothesis suggests that viruses

predate cellular life, having evolved from primordial

self-replicating molecules. This theory implies that viruses may

represent remnants of precellular life, providing insight into

early molecular evolution (12).

The regression hypothesis posits that viruses are degenerate forms

of parasitic cells that gradually lose essential genes over time,

reducing themselves to genetic elements capable of hijacking only

host cells. Finally, the escaped gene hypothesis theorizes that

viruses originate from fragments of host genetic material, such as

plasmids or transposons, that gain the ability to exit and enter

other cells, becoming infectious in the process (1).

Despite their origin, viruses have co-evolved with

host species for millions of years, developing sophisticated

mechanisms to persist, evade immune detection and manipulate

cellular functions. These evolutionary traits are particularly

relevant in chronic infections such as periodontitis, where viruses

can remain undetected, yet actively modulate host-pathogen

interactions and inflammation (13).

As regards the classification of viruses, according

to the Baltimore Classification of Viruses, introduced by Nobel

Laureate David Baltimore in 1971, categorizes viruses into seven

classes on the basis of their genome type and replication strategy

(Table I). This system is

particularly relevant in periodontology, where viral infections can

modulate host immunity and contribute to the pathogenesis and

progression of periodontal diseases (14).

| Table IBaltimore classification of

viruses. |

Table I

Baltimore classification of

viruses.

| Class | Genome type and

replication strategy | Examples | Relevance to

periodontology |

|---|

| Class I | Double-stranded DNA

(dsDNA) | Herpesviridae

(HSV), Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Papillomaviridae

(HPV) | • Latent infections

in the periodontium • Can reactivate under stress or

immunosuppression • HPV associated with oral cancers affecting

periodontal tissues |

| Class II | Single-stranded DNA

(ssDNA) |

Parvoviridae | • Less studied in

periodontology • May integrate into host genome • Potential role in

chronic oral lesions and gingivitis |

| Class III | Double-stranded RNA

(dsRNA) | Reoviridae (e.g.,

Rotavirus) | • Rarely cause

chronic oral infections • Systemic infections may impair immune

responses, indirectly impacting periodontal health |

| Class IV | Positive-sense

single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) | Picornaviruses

(Enteroviruses, Rhinoviruses) | • Can alter immune

response • May exacerbate existing gingivitis or oral infections

indirectly |

| Class V | Negative-sense

single-stranded RNA (-ssRNA) | Paramyxoviruses

(measles, mumps), rhabdoviruses (rabies) | • Not directly

involved in periodontal disease • May lead to immunosuppression,

increasing susceptibility to periodontal pathogens |

| Class VI | Single-stranded RNA

with reverse transcription | Retroviruses (e.g.,

HIV) | • Profound effect

on immune system (CD4+ T-cell depletion) • Strongly

associated with severe periodontal diseases (e.g., necrotizing

periodontitis) • Disrupts microbial-immune balance in the

periodontium |

| Class VII | Double-stranded DNA

with reverse transcription | Hepadnaviruses

(e.g., hepatitis B virus) | • Not directly

pathogenic to periodontal tissues • Can cause immune dysfunction •

Liver disease affects host response to periodontal pathogens |

4. Viral components and structure, and

replication and spread in the body

Components and structure of a

virus

A virus particle, or virion, consists of several key

components: The genome (either DNA or RNA) that encodes viral

proteins, a protective protein shell called the capsid, and, in

enveloped viruses, an outer lipid bilayer derived from the host

cell membrane (6,15). This envelope typically adorns

glycoproteins or peplomers that facilitate viral attachment to

specific host cell receptors, allowing the virus to enter the host

cell (16).

Some viruses, such as retroviruses, also carry

enzymes, such as reverse transcriptase or integrase, which are

essential for replication within host cells. The capsid structure

can range from simple icosahedral or helical forms to more complex

arrangements, which influence the ability of a virus to interact

with host cells, evade immune responses and withstand environmental

challenges. In the context of periodontal health, these viral

components play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of periodontal

diseases (17).

For example, viruses, such as herpesviruses can

persist in periodontal tissues by evading immune detection through

latency, contributing to chronic inflammation. The presence of

viral particles in periodontal pockets may not only increase the

severity of gingival inflammation, but can also alter the balance

between host immunity and pathogenic bacteria, promoting the

progression of conditions, such as periodontitis, particularly in

immunocompromised individuals (18).

Viral replication and spread

The Modes of viral replication and spread in the

human body are summarized in Table

II. There are various steps of viral replication and systemic

dissemination with relevance to periodontal tissues (12). In systemic infections, the virus

can spread through the bloodstream, nerves, or lymphatic system,

where it can reach distant sites in the body, including the oral

cavity. Oral tissues, such as the gingival mucosa and periodontal

tissues, can function as reservoirs for certain viruses. For

example, herpesviruses can remain latent in host cells, such as the

sensory ganglia, and re-emerge under certain conditions, such as

immunosuppression or stress. This periodic reactivation results in

the development of recurrent oral lesions, such as cold sores or

ulcers (19). In the context of

periodontal health, viral replication and spread can exacerbate

existing periodontal conditions by altering the immune response and

interacting with periodontal bacteria. Viral infections can lead to

persistent inflammation in the periodontium, contributing to tissue

breakdown, the destruction of periodontal ligaments and even

alveolar bone loss. Over time, viral reactivation and chronic

inflammation can aggravate periodontal disease, particularly in

immunocompromised individuals (12).

| Table IIMode of viral spread and

replication. |

Table II

Mode of viral spread and

replication.

| Step | Process | Description |

|---|

| 1 | Attachment | Virus binds to

specific receptors on the host cell surface, ensuring target

specificity. |

| 2 | Entry | Virus enters the

host cell via endocytosis or direct fusion with the cell

membrane. |

| 3 | Uncoating | Viral genetic

material (DNA or RNA) is released into the cytoplasm or nucleus of

the host. |

| 4 | Transcription and

translation | Virus hijacks the

host machinery to transcribe its genome and translate viral

proteins using host ribosomes and enzymes. |

| 5 | Assembly | Newly synthesized

viral genomes and proteins are assembled into new virions. |

| 6 | Release | New virions exit

the host cell by budding (for enveloped viruses) or by cell lysis

(for non-enveloped viruses), often leading to host cell

destruction. |

5. Host immune response to viruses

The immune system responds to viral infections

through a coordinated network of innate and adaptive mechanisms.

Innate responses include those involving interferons, natural

killer cells and macrophages, which serve as the first line of

defense. Interferons function as antiviral cytokines, promoting an

antiviral state in neighboring cells and enhancing antigen

presentation (20).

Adaptive immunity involves both humoral and

cell-mediated responses (21).

B-lymphocytes produce neutralizing antibodies (IgG and IgA) that

bind viral particles, preventing entry into host cells. In the oral

cavity, secretory IgA plays a critical role in mucosal defense.

Cytotoxic t-lymphocytes (CD8+) recognize and destroy

virus-infected cells by detecting viral peptides presented on MHC

class I molecules (22).

Viruses counteract host defenses by downregulating

MHC molecules, secreting immunomodulatory proteins, inhibiting

apoptosis, and mutating antigenic epitopes to escape recognition.

These immune evasion strategies allow chronic persistence and

immune dysregulation, a hallmark of virus-related periodontal

pathogenesis (23).

6. Diagnostic methods in virology

The accurate identification of viral infections in

periodontal tissues requires both direct and indirect diagnostic

techniques. Direct methods include the detection of viral antigens

via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays or immunofluorescence,

visualization via electron microscopy and polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) for viral nucleic acid amplification. PCR has become the gold

standard for detecting herpesviruses and human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) in oral tissues due to its high sensitivity and

specificity (17).

Indirect methods involve serological tests that

detect host antibodies against viral proteins and virus isolation

in tissue cultures to observe cytopathic effects (24). Light microscopy can also identify

viral inclusion bodies within infected tissues. These methods,

particularly when used in combination, allow clinicians to detect

latent or active viral infections in periodontal lesions,

contributing to targeted therapy and prognosis assessment (25).

7. Different viruses and their periodontal

implications

A summary of viral pathogenesis in periodontitis

based on the mechanisms of action of viruses is presented in

Table III. There are various

viruses involved in periodontal diseases:

| Table IIIClassification of viral pathogenesis

in periodontitis based on the mechanisms of action. |

Table III

Classification of viral pathogenesis

in periodontitis based on the mechanisms of action.

| Category of

pathogenesis |

Definition/focus | Key viruses | Mechanism in

periodontitis |

|---|

| 1. Direct viral

cytopathic effects | Viral destruction

of host cells, leading to localized lesions or tissue

necrosis. | Herpes simplex

virus (HSV)-1/2, human papillomavirus (HPV), picornaviruses (e.g.,

coxsackievirus) | The virus directly

infects and destroys epithelial and fibroblast cells, causing

ulceration, vesiculation and tissue breakdown, particularly in

primary or acute infections. HPV infection can lead to epithelial

dysplasia in the sulcus. |

| 2. Indirect

immune-mediated effects | Viruses manipulate

and dysregulate the host immune response, creating chronic

inflammation and systemic immune deficiency. | Human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human

cytomegalovirus (HCMV) | Viruses establish

latency and periodic reactivation, actively suppressing local

immune surveillance (e.g., inhibiting MHC molecules or reducing

neutrophil function) and driving chronic, non-resolving

inflammation via the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g.,

IL-6, TNF-α). |

| 3. Viral-bacterial

synergism in periodontal pockets | Viruses create a

pathological microenvironment that enhances the survival and

virulence of periodontopathic bacteria. | EBV and HCMV

(co-infection), viruses that cause immunosuppression (e.g.,

HIV) | Viral immune

dysregulation and inflammation favor dysbiosis by impairing the

host's ability to clear bacteria. This allows the proliferation and

increased virulence of key periodontopathogens (e.g., P.

gingivalis), leading to accelerated and more severe tissue

destruction than either pathogen could achieve alone. |

The Herpesviridae family

Herpesviridae family includes several viruses

implicated in periodontal diseases: Herpes simplex virus (HSV-1 and

HSV-2), EBV and HCMV. These are double-stranded DNA viruses capable

of establishing lifelong latency with periodic reactivation.

EBV infects B lymphocytes and epithelial cells and

is frequently detected in patients with aggressive periodontitis.

It can promote the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, reduce

neutrophil function and synergize with periodontopathogenic

bacteria. EBV has also been shown to be associated with oral hairy

leukoplakia (OHL), particularly in HIV-positive individuals

(26). In EBV, latent membrane

protein-1 activates the NF-κB and JNK pathways, promoting the

release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and impairing neutrophil

oxidative burst (27).

HCMV exhibits broader cell tropism, infecting

macrophages, endothelial cells and fibroblasts. It is commonly

found in deep periodontal pockets and is associated with severe

inflammation and immune suppression. Co-infection with EBV and HCMV

in lesions in periodontitis is associated with greater tissue

destruction and greater probing depths (23). HCMV expresses immunomodulatory

proteins, such as US28, a viral chemokine receptor that

dysregulates leukocyte trafficking and enhances inflammatory

mediator production. These molecular strategies collectively weaken

host defense and facilitate bacterial overgrowth, amplifying

periodontal tissue destruction (28).

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are known for their ulcerative

manifestations in the oral cavity. HSV-1 primarily causes

oral-facial infections and has been linked to necrotizing

periodontal diseases, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.

These viruses possess the ability to modulate host immunity and

trigger apoptosis, contributing to rapid tissue breakdown (29).

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV is a non-enveloped DNA virus with a predilection

for epithelial tissues. Of note, >200 types have been

identified, with HPV-16 and HPV-18 classified as high-risk due to

their association with oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell

carcinoma. In periodontal tissues, HPV DNA has been isolated from

gingival sulci, periodontal pockets and inflamed gingiva,

suggesting a possible etiological or contributory role (30).

The E6 and E7 proteins of HPV interfere with tumor

suppressor proteins, such as p53 and Rb, promoting cell cycle

dysregulation and potential epithelial dysplasia. Although the

direct link between HPV and periodontitis remains under

investigation, its detection in diseased periodontal tissues,

particularly in HIV-infected patients, highlights its potential

role in modulating epithelial barrier integrity and immune

surveillance (31). Recent

research has shown that HPV-associated epithelial dysregulation may

enhance microbial adhesion and alter gingival epithelial immune

signaling (32).

Picornaviruses and

paramyxoviruses

Although less frequently implicated in periodontal

diseases, picornaviruses and paramyxoviruses may affect the oral

cavity. Picornaviruses, such as coxsackievirus A, are

single-stranded RNA viruses responsible for hand-foot-and-mouth

disease and herpangina, both of which feature vesicular and

ulcerative oral lesions. These typically affect children and may

cause discomfort, poor oral hygiene and transient gingival

inflammation (33).

Paramyxoviruses, such as the measles virus and mumps

virus can also be present in the oral cavity. Measles present with

Koplik's spots, whereas mumps cause parotitis. Although these

viruses are not directly involved in periodontal tissue

destruction, they can alter host immunity and mucosal barriers,

indirectly influencing periodontal health, particularly in

susceptible populations (33). RNA

viruses may modify interferon pathways and innate antiviral

signaling, indirectly heightening periodontal tissue

vulnerability.

HIV

The most clinically significant retrovirus in

periodontology is HIV. HIV is a single-stranded RNA virus that

integrates into host DNA via reverse transcriptase and targets

CD4+ T-lymphocytes, leading to progressive

immunosuppression. The oral cavity is a sentinel site for

HIV-related manifestations and often reveals early signs of

systemic disease (20).

In the context of periodontal disease, HIV is

associated with linear gingival erythema (LGE), necrotizing

ulcerative gingivitis (NUG), necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis

(NUP), and necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis (NUS). These

conditions are characterized by the rapid and severe destruction of

soft and hard tissues, spontaneous bleeding and halitosis. They are

frequently accompanied by systemic symptoms and often occur at low

CD4+ counts (<200 cells/µl) (34).

HIV also facilitates co-infections with

herpesviruses, HPV and fungal pathogens, such as Candida

albicans. Saliva and gingival crevicular fluid in HIV-positive

individuals often harbor detectable levels of HIV RNA, indicating

the role of the oral cavity as a potential reservoir and site of

viral transmission (35).

While previous studies have established associations

between herpesviruses, HIV, HPV and periodontal destruction, the

strength of evidence varies considerably (5,34).

Mechanistic insights are strongest for EBV and HCMV, whereas HPV

and RNA viruses rely largely on correlative or preliminary reports.

Conflicting findings, particularly regarding virus detection across

populations and methodologies, suggest the need for standardized

sampling and molecular protocols. Future studies are warranted to

integrate longitudinal designs and metagenomic approaches to

clarify whether viruses initiate, accelerate, or merely amplify

periodontal breakdown.

8. Clinical oral manifestations of viral

infections

The oral manifestations of viral infections

represent a critical aspect of oral diagnostics (20), particularly in immunocompromised

individuals, such as those with HIV/AIDS. These manifestations can

range from lesions and gingival inflammation to severe forms of

periodontal disease, underscoring the need for a careful assessment

of the viral etiology of oral pathologies (25).

OHL

OHL is a distinctive condition caused by EBV. It

typically presents as white, non-removable plaques on the lateral

borders of the tongue and is often associated with HIV-positive

patients, particularly those with advanced immunosuppression. These

plaques are asymptomatic, but can be diagnostic markers for HIV

progression, indicating a decline in immune function. Lesions are

considered a marker of immunocompromised status rather than a

direct indicator of malignancy, although their presence may

increase the risk of further oral lesions and opportunistic

infections (19).

Candidiasis

Although candidiasis is a fungal infection, it often

co-exists with viral infections, particularly in individuals with

HIV or other forms of immunosuppression. It is considered a

diagnostic marker of immune decline, particularly when it presents

as oropharyngeal candidiasis (thrush). Fungal infection caused by

Candida albicans can be exacerbated by viral infections,

particularly HIV, as the capacity of the immune system to fight

opportunistic infections is significantly diminished. Candidiasis

manifests as white patches on mucosal surfaces and is often

accompanied by redness or ulceration in severe cases. Its recurrent

presence in patients with HIV is often associated with advanced

immunosuppression and serves as an indicator for assessing immune

system function and the progression of the underlying viral

infection (20).

LGE

LGE is closely associated with HIV and presents as a

distinct red band along the gingival margin, characterized by

minimal plaque accumulation and a poor response to conventional

treatment. It is a manifestation of immune dysregulation and the

inflammatory response within the gingiva and is often observed in

individuals with HIV/AIDS. Gingival inflammation is not typically

caused by bacterial plaque accumulation, but rather by the immune

response of the host to the presence of oral pathogens, including

viral and fungal elements. LGE may be one of the first clinical

signs of immune decline in patients with HIV, and is a key oral

manifestation requiring careful management alongside antiviral

therapy and periodontal care (36).

Necrotizing gingival and periodontal

diseases (NUG/NUP/NUS)

NUG, NUP and NUS are severe oral conditions often

observed in individuals with HIV/AIDS, and they are frequently

complicated by viral co-infections [e.g., HSV and cytomegalovirus

(CMV)]. These conditions are characterized by rapid and severe

tissue necrosis in the gingiva and periodontium, leading to painful

ulcers, bleeding and a foul odor (37). Viral co-infections aggravate the

clinical presentation, as they suppress the immune response and

hinder the ability of the body to effectively manage both viral and

bacterial pathogens. The rapid progression of these diseases can

result in significant tooth loss and oral disfigurement if not

promptly treated with a combination of antiviral and antibacterial

therapies (34).

Ulcers and erosions

Oral ulcers and erosions are common manifestations

of viral infections triggered by viruses, such as HSV,

Coxsackievirus and paramyxoviruses. These painful, shallow ulcers

typically appear on non-keratinized mucosal surfaces, such as the

buccal mucosa, tongue and soft palate. Characteristic painful

lesions are often recurrent, particularly in individuals with HSV

infections, which can be reactivated by stress, immune suppression,

or other triggers. Viral ulcers can greatly impair oral function,

causing difficulty in eating and speaking, and are often

accompanied by swelling and redness. The presence of herpetic

ulcers in the oral cavity is often an indication of active viral

replication, requiring appropriate antiviral treatment to control

symptoms and reduce the risk of transmission (38).

9. Clinical implications and management

The recognition of viral involvement in periodontal

disease requires a multifaceted management approach that not only

targets the viral pathogen, but also addresses the immune status of

the patient and the complexity of coinfections. Given the

increasing interplay between viral infections and periodontal

diseases, it is essential for clinicians to implement comprehensive

strategies to control viral replication, maintain oral health and

reduce the risk of disease progression, particularly in

immunocompromised patients, such as those living with HIV/AIDS

(34).

Antiviral therapy

In the management of viral periodontal diseases,

antiviral medications play a critical role in reducing the viral

load and preventing the progression of lesions:

i) Acyclovir, ganciclovir and valganciclovir are

commonly used in the treatment of HSV and CMV infections. These

drugs inhibit viral replication by targeting viral DNA synthesis,

and they are particularly effective in preventing recurrent

outbreaks of HSV and controlling CMV-related oral manifestations,

including oral ulcers and gingivitis (39).

ii) Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is

the cornerstone for the management of HIV and preventing the

immunosuppressive effects that exacerbate periodontal disease.

HAART functions by inhibiting various stages of the HIV replication

cycle, thereby controlling the viral load and improving the immune

response, which can help reduce the severity of oral manifestations

such as oral candidiasis, OHL and gingival inflammation associated

with HIV. By restoring immune function, HAART can reduce the

frequency of periodontal infections and complications related to

immunosuppression (40).

Combined antiviral and antibacterial

therapies

In a number of cases, particularly those involving

coinfections (viral and bacterial), a combination of antiviral and

antibacterial therapies may be necessary. This is particularly true

for conditions, such as NUG or NUP, where viral infections such as

HSV or CMV cause bacterial infection (41). The use of antibiotics such as

metronidazole (effective against anaerobic bacteria) and

doxycycline (which also has anti-inflammatory properties) helps

control bacterial overgrowth, preventing further tissue

destruction. In such cases, the dual approach ensures that both the

viral and bacterial components are managed effectively, reducing

the risk of systemic spread and improving oral outcomes (39).

Standard periodontal therapy

Standard periodontal therapy remains an essential

part of managing viral periodontal diseases, particularly when

combined with antiviral medications, such as the following: i)

Scaling and root planing helps to remove bacterial biofilms and

calculus deposits, reducing inflammation and increasing the

effectiveness of antiviral treatments (42). ii) Chlorhexidine irrigation can be

used to irrigate periodontal pockets, reducing plaque accumulation

and controlling bacterial growth, while allowing antiviral

treatments to target the viral load more effectively. iii)

Antibiotic coverage (e.g., metronidazole or doxycycline) is often

administered to manage the bacterial component of coinfections,

which can exacerbate the clinical presentation of viral periodontal

diseases.

However, beyond mechanical and antimicrobial

management, it is crucial to consider the systemic health and

immune status of the patient. In patients with HIV, the regular

monitoring of CD4+ T-cell counts and the viral load is

necessary. These markers help assess the degree of immune

suppression, predict periodontal risk and guide treatment

modifications. Lower CD4+ counts are associated with

more severe periodontal disease progression, and higher viral loads

suggest poorer immune control, necessitating more aggressive

periodontal and antiviral management (43).

Recent periodontal consensus reports emphasize

adjunctive host-modulation therapies, such as sub-antimicrobial

doxycycline, NSAID-modulating regimens, and complement-targeting

agents, which may be particularly valuable when viral-driven immune

dysregulation underlies periodontal destruction (44,45).

Preventive strategies

Prevention plays a critical role in reducing viral

transmission and disease recurrence in individuals who are at a

high risk of developing viral infections:

i) Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV)

and varicella (chickenpox) can significantly reduce the risk of

developing virus-related oral diseases, such as oral cancers or

varicella-zoster-related oral lesions. The HPV vaccine, in

particular, has been shown to reduce the incidence of oral cancers,

whereas varicella vaccination helps prevent reactivation of the

virus, which can result in shingles with oral involvement (39).

ii) Immune support through the use of nutritional

supplements, such as vitamins D and C, zinc and

prebiotics/probiotics (46),

appropriate antiretroviral therapy (ART), typically a combination

of drugs, such as non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors,

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors

(47), and other immune-boosting

treatments, including certain immunomodulatory cytokines (e.g.,

IL-2 or IFN-γ in select contexts) or therapeutic vaccines (48), can help strengthen the defence

system of the body against opportunistic viral infections.

iii) Strict oral hygiene practices are essential for

reducing the risk of developing oral viral infections and

preventing the recurrence of candidiasis and other opportunistic

infections. Brushing with fluoride toothpaste, regular flossing and

antiseptic mouthwashes (such as those containing chlorhexidine) can

help reduce the bacterial and viral loads in the mouth (43).

10. Emerging viral pathogens and periodontal

health

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has

been implicated in various systemic effects that in turn affect

periodontal health. SARS-CoV-2, an RNA virus, is capable of

inducing widespread immune system dysregulation and inflammatory

responses, both of which can exacerbate pre-existing periodontal

diseases. Patients with COVID-19 have been reported to experience

oral manifestations, such as dry mouth, oral lesions and an altered

taste, which contribute to periodontal inflammation and tissue

breakdown (49,50).

COVID-19 is also associated with increased levels of

cytokines and pro-inflammatory mediators, which may exacerbate

gingival inflammation and accelerate the progression of

periodontitis. Furthermore, the ability of the virus to suppress

immune function and cause immunosuppression in severe cases

enhances susceptibility to secondary infections, including

bacterial periodontal pathogens. This immunosuppression, along with

increased viral load, can lead to worsening periodontal conditions,

particularly in patients with underlying chronic diseases such as

diabetes or HIV (51).

Additionally, patients with COVID-19 may have a

greater incidence of co-infection with periodontal pathogens, which

can increase the severity of periodontal destruction. The stress

associated with the pandemic and reduced access to dental care may

also contribute to the neglect of oral hygiene, further

exacerbating the progression of periodontal disease. These factors

collectively underscore the need for comprehensive oral health care

and preventive measures during and after COVID-19 infection

(52).

Recent studies have demonstrated that

SARS-CoV-2-induced lymphopenia, elevated levels of IL-6, and ACE2

overexpression in the gingival epithelium may heighten periodontal

inflammatory responses (49,50).

11. Future directions: Unlocking new avenues

in viral periodontology

The recognition that viruses are not bystanders, but

silent saboteurs in periodontal disease necessitates a paradigm

shift in both research and clinical management. To translate this

knowledge into tangible clinical benefits and to strengthen the

multifactorial etiology model of periodontitis, future

investigations must prioritize the following innovative areas:

i) Non-invasive viral biomarkers (salivary

diagnostics): Future research is required to focus on developing

highly sensitive, rapid and chair-side assays to detect and

quantify the viral load (e.g., EBV, HCMV and HIV) directly in

non-invasive samples, such as salivary fluid and GCF. Salivary

diagnostics provide a potential tool for early risk assessment,

monitoring disease activity and predicting the need for aggressive

antiviral/antibacterial therapies, particularly in

immunocompromised individuals (34).

ii) Omics technologies for the periodontal

microbiome: Employing advanced technologies, such as shotgun

metagenomics and RNA sequencing will allow for the simultaneous

analysis of the complete viral, bacterial, and fungal communities

(the ‘virome’, ‘bacteriome’ and ‘mycobiome’) within periodontal

lesions. This approach will move beyond simply detecting presence

to understanding the precise transcriptomic and proteomic

interactions that facilitate tissue destruction (6), providing a high-resolution map of the

viral-host-bacterial synergy described in the present review.

iii) Novel antivirals and targeted therapies:

Research is required to investigate next-generation therapeutic

agents beyond conventional antivirals (e.g., acyclovir and

ganciclovir) and HAART. This includes exploring the potential of

host-modulation therapies and advanced gene-editing techniques such

as CRISPR-based technologies to target and inactivate the specific

latent viral DNA of persistent viruses like herpesviruses (EBV and

HCMV) within periodontal host cells. Such targeted approaches may

provide a cure for virus-driven chronic inflammation (39).

iv) Vaccine development for viral periodontal risk:

Given the strong association between viruses, such as EBV, HCMV and

HPV with severe and aggressive forms of periodontitis, public

health strategies should consider the impact of viral vaccination.

Widespread vaccination against these specific

periodontitis-associated viruses, similar to existing HPV and

varicella vaccines, may offer a potent long-term preventive measure

against disease initiation and recurrence.

Emerging approaches, such as salivary virome assays,

metagenomic sequencing and CRISPR-based antiviral platforms may

enable personalized risk prediction and targeted suppression of

latent viral reservoirs in periodontal tissues. Integrating these

tools into diagnostic workflows could transform early detection and

individualized periodontal care.

12. Conclusion

Viruses are no longer considered passive bystanders

in periodontal diseases. The ability of viruses to establish

latency, evade host immunity, modulate inflammatory pathways and

synergize with bacterial pathogens positions them as significant

contributors to periodontal pathogenesis. Their presence in

periodontal pockets and gingival tissues underscores the need to

expand current diagnostic frameworks beyond bacteria-focused

models. Integrating viral detection, through molecular diagnostics,

salivary biomarkers and chairside assays into routine periodontal

evaluation represents a critical future direction that may

transform risk assessment and early diagnosis.

Furthermore, the complex interplay among viruses,

host immunity and the oral microbiome highlights the necessity for

interdisciplinary collaboration among periodontists, virologists,

immunologists and infectious disease specialists. Such

collaborations are essential for developing targeted antivirals,

vaccines, host-modulation strategies and personalized treatment

protocols.

As the understanding of viral contributions deepens,

periodontology should embrace a more holistic, multi-pathogen

approach to prevention, diagnosis and management, paving the way

for more accurate prognostication and improved clinical

outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

AS and VRA were involved in the conceptualization of

the present review, as well as in data curation, in the literature

search, the evaluation of studies form the literature for inclusion

in the review, project administration, validation, visualization

and in the writing of the original draft, and in the writing,

reviewing and editing of the manuscript. SUN and DGK were involved

in the conceptualization of the present review, in data curation,

investigation, in the literature search, in project administration,

validation and study supervision. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Wankhede A, Wankhede S and Wasu S: Role of

genetic in periodontal disease. J ICDRO. 9(53)2017.

|

|

2

|

Popova C, Dosseva-Panova V and Panov V:

Microbiology of periodontal diseases. A review. Biotechnol

Biotechnol Eq. 27:3754–3759. 2013.

|

|

3

|

Abdulkareem AA, Al-Taweel FB, Al-Sharqi

AJB, Gul SS, Sha A and Chapple ILC: Current concepts in the

pathogenesis of periodontitis: From symbiosis to dysbiosis. J Oral

Microbiol. 15(2180743)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H and Van

Dyke TE: Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of

periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 64:57–80. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Contreras A and Slots J: Herpesviruses in

human periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 35:3–16.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Parra B and Slots J: Detection of human

viruses in periodontal pockets using polymerase chain reaction.

Oral Microbiol Immunol. 11:289–293. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Botero A, Betancourth M, Jaramillo A,

Montoya Y and Hincapié O: Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus in

chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis. Rev Clín

Periodoncia Implantol Rehabil Oral. 3:65–71. 2010.

|

|

8

|

Slots J: Herpesviruses in periodontal

disease-an update. J Oral Microbiol. 2004;3(1).

|

|

9

|

Kamma JJ, Nakou M and Baehni PC:

Association of herpesviruses with the progression of periodontal

lesions. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 16:282–288. 2001.

|

|

10

|

Zhu C, Li F, Ce Y, Zhang S, Li Z and Zhou

X: Association between herpesviruses and chronic periodontitis: A

meta-analysis based on case-control studies. PLoS One.

10(e0144319)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Li F, Zhu C, Deng FY, Wong MCM, Lu HX and

Feng XP: Herpesviruses in etiopathogenesis of aggressive

periodontitis: A meta-analysis based on case-control studies. PLoS

One. 12(e0186373)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Slots J: Human viruses in periodontitis.

Periodontol 2000. 53:89–110. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Belibasakis GN, Belstrøm D, Eick S, Gursoy

UK, Johansson A and Könönen E: Periodontal microbiology and

microbial etiology of periodontal diseases: Historical concepts and

contemporary perspectives. Periodontol 2000. 91:12–32.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Koonin E V..Krupovic M and Agol VI: The

Baltimore Classification of Viruses 50 Years Later: How Does It

Stand in the Light of Virus Evolution? Microbiol Mol Biol Rev.

85(e0005321)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Satija A and Rai JJ: Viruses: A Paradox in

Etiopathogenesis of Periodontal Diseases. IOSR Journal of Dental

and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN [Internet]. 2015;14:58-64.

Available from: www.iosrjournals.org.

|

|

16

|

Teles F, Collman RG, Mominkhan D and Wang

Y: Viruses, periodontitis, and comorbidities. Periodontology.

89:190–206. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Gupta C and Dhruvakumar D: Role of

periodontopathogenic virus in periodontal disease: a review. Tanta

Dental J. 14:51–55. 2017.

|

|

18

|

Bhagat M, Tapashetti R, Fatima G and

Bhutani N: Role of Viruses in Periodontal Diseases. Galore Int J

Health Sci Res. 5:89–97. 2020.

|

|

19

|

Slots J: Oral viral infections of adults.

Periodontol 2000. 49:60–86. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Belardelli F: Role of interferons and

other cytokines in the regulation of the immune response. APMIS.

103:161–179. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Murphy K and Weaver C: Janeway's

Immunobiology. 9th edition. Garland Science, New York, NY,

2017.

|

|

22

|

Tizard I: Veterinary Immunology: An

Introduction. 10th edition. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2018.

|

|

23

|

Contreras A, Zadeh HH, Nowzari H and Slots

J: Herpesvirus infection of inflammatory cells in human

periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 14:206–212. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Taneja N, Kudva P, Goswamy M, Bhat G and

Kudva HP: Role of viruses in periodontal diseases: A review. Int J

Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 6:1481–1488. 2017.

|

|

25

|

Chandran W, Dharmadhikari S and Shetty D:

Viruses in periodontal disease: A literature review. Int J Applied

Dental Sci. 8:242–245. 2022.

|

|

26

|

Slots J: Herpesviral-bacterial

interactions in periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 52:117–140.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhao Z, Liu W and Luo B: Role of Oxidative

Stress in the Epstein–Barr Virus Lifecycle and Tumorigenicity.

Future Virology. 18:465–477. 2023.

|

|

28

|

Botero JE, Rodríguez-Medina C,

Jaramillo-Echeverry A and Contreras A: Association between human

cytomegalovirus and periodontitis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res. 55:551–558. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Izzat AW, Al-Ghurabi H, Adham LS and

Shaker ZF: Emerging Role of Viral Infection in Periodontal Disease.

Dentistry 3000: 13. https://doi.org/10.5195/d3000.2025.938.

|

|

30

|

Tejnani A, Mani A, Marawar P and Pawar B:

Herpes virus: A key missing piece of the periodontopathogenic

jigsaw puzzle. Chronicles of Young Scientists. 3(245)2012.

|

|

31

|

Kazi MMAG and Bharadwaj R: Role of

herpesviruses in chronic periodontitis and their association with

clinical parameters and in increasing severity of the disease. Eur

J Dent. 11:299–304. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Feng X, Patel EU, White JL, Li S, Zhu X,

Zhao N, Shi J, Park DE, Liu CM, Kaul R, et al: Association of Oral

Microbiome With Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection: A Population

Study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,

2009-2012. J Infect Dis. 230:726–735. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Rajapandi S, Sukumaran ES, Prasad KRN,

Venkatesan AV, Ravichandran TAS and Sabarathinam S: Viral Invasion

of the Oral Cavity: A Review of Viral Impact on Oral Health and the

Potential Use of Saliva as a Diagnostic Tool. Front Biosci (Elite

Ed). 17(33494)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Patton LL, Phelan JA, Ramos-Gomez FJ,

Nittayananta W, Shiboski CH and Mbuguye TL: Prevalence and

classification of HIV-associated oral lesions. Oral Dis. 20 (Suppl

1):S5–S12. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Cappuyns I, Gugerli P and Mombelli A:

Viruses in periodontal disease-A review. Oral Dis. 11:219–229.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Lomelí-Martínez SM, González-Hernández LA,

Ruiz-Anaya A, Lomelí-Martínez MA, Martínez-Salazar SY, Mercado

González AE, et al: Oral Manifestations Associated with HIV/AIDS

Patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 58(1214)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Malek R, Gharibi A, Khlil N and Kissa J:

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Contemp Clin Dent. 8:496–500.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Xu X, Zhang Y and Li Q: Characteristics of

herpes simplex virus infection and pathogenesis suggest a strategy

for vaccine development. Rev Med Virol. 29(e2052)2019.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Forghieri F, Cordella S, Marchesi F, Itri

F, Del Principe MI, Cavalieri E, Pasciolla C, Bonanni M, Criscuolo

M, Fiorentini A, et al: Antiviral prophylaxis to prevent herpes

simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) reactivation

in adult patients with newly diagnosed acute leukemia: results of a

survey submitted to Italian centers belonging to SEIFEM

(Sorveglianza Epidemiologica Infezioni nelle Emopatie) group. Ann

Hematol. 103:4329–4332. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Nuwagaba J, Li JA, Ngo B and Sutton RE: 30

years of HIV therapy: Current and future antiviral drug targets.

Virology. 603(110362)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Sadowski LA, Upadhyay R, Greeley ZW and

Margulies BJ: Current drugs to treat infections with herpes simplex

viruses-1 and -2. Viruses. 13(1228)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Parashar A, Sanikop S, Zingade A, Parashar

S and Gupta S: Virus-associated periodontal diseases. Futuristic

implications. J Dent Oral Disord Ther. 3:1–5. 2015.

|

|

43

|

Kim YJ, Song YW, Park SY, Cha JK, Lee HJ,

Yang SM, Park JB and Koo KT: Current understanding of the etiology,

diagnosis, treatment, and management of peri-implant diseases: a

narrative review for the consensus report of the Korean Academy of

Periodontology. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 54:377–392.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Wang CW: Emerging opportunity to implement

host modulation therapy in non-surgical periodontal therapy-The

role of probiotics and future perspectives. J Dent Sci.

19:1305–1306. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Herrera D, Tonetti MS, Chapple I,

Kebschull M, Papapanou PN, Sculean A, Abusleme L, Aimetti M,

Belibasakis G, Blanco J, et al: Consensus Report of the 20th

European Workshop on Periodontology: Contemporary and Emerging

Technologies in Periodontal Diagnosis. J Clin Periodontol. 52

(Suppl 29):4–33. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Sinopoli A, Sciurti A, Isonne C, Santoro

MM and Baccolini V: The Efficacy of Multivitamin, Vitamin A,

Vitamin B, Vitamin C, and Vitamin D Supplements in the Prevention

and Management of COVID-19 and Long-COVID: An Updated Systematic

Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients.

16(1345)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Sax PE: Treatment of HIV infection. N Engl

J Med. 377:1590–1591. 2017.

|

|

48

|

Peluso MJ, Sandel DA, Deitchman AN, Kim

SJ, Dalhuisen T, Tummala HP, Tibúrcio R, Zemelko L, Borgo GM and

Singh SS: Correlates of HIV-1 control after combination

immunotherapy. Nature: Dec 1, 2025 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

49

|

Schwartz J, Capistrano KJ, Gluck J,

Hezarkhani A and Naqvi AR: SARS-CoV-2, periodontal pathogens, and

host factors: The trinity of oral post-acute sequelae of COVID-19.

Rev Med Virol. 34(e2543)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Riad A, et al: Oral manifestations of

COdVID-19 infection: A systematic review. J Clin Med.

10(3063)2021.

|

|

51

|

Basso L, Chacun D, Sy K, Grosgogeat B and

Gritsch K: Periodontal Diseases and COVID-19: A Scoping Review. Eur

J Dent. 15:768–775. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Al-Hadeethi T, Charde P, Sunil S, Marouf N

and Tamimi F: Association Between Periodontitis and COVID-19. Curr

Oral Health Rep. 11:1–7. 2024.

|